Rod Dreher's Blog, page 514

November 20, 2016

Legutko On The Trump Moment

This summer, I told you that J.D. Vance was the man to listen to if you wanted to understand what was happening in contemporary American politics. Now, please hear me when I say that Ryszard Legutko is another critically important voice for our time.

Legutko is a Polish philosopher and politician who was active in the anti-communist resistance. He is most recently the author of The Demon In Democracy: Totalitarian Temptations In Free Societies. In this post from September, I said that reading the book — which is clearly and punchily written — was like taking a red pill — meaning that it’s hard to see our own political culture the same way after reading Legutko. His provocative thesis is that liberal democracy, as a modern political philosophy, has a lot more in common with that other great modern political philosophy, communism, than we care to think. He speaks as a philosopher who grew up under communism, who fought it as a member of Solidarity, and who took part in the reconstruction of Poland as a liberal democracy. It has been said that the two famous inhuman dystopias of 20th century English literature — Orwell’s 1984 and Huxley’s Brave New World — correspond, respectively, to Soviet communism and mass hedonistic technocracy. Reading Legutko, you understand the point very well.

In this post, I quote several passages from The Demon In Democracy. Among them, these paragraphs in which he explains how Poland cast off the bonds of communism only to find that liberal democracy imposed similar interdictions on free thought and debate:

Very quickly the world became hidden under a new ideological shell and the people became hostage to another version of the Newspeak but with similar ideological mystifications. Obligatory rituals of loyalty and condemnations were revived, this time with a different object of worship and a different enemy.

The new commissars of the language appeared and were given powerful prerogatives, and just as before, mediocrities assumed their self-proclaimed authority to track down ideological apostasy and condemn the unorthodox — all, of course, for the glory of the new system and the good of the new man. Media — more refined than under communism — performed a similar function: standing at the forefront of the great transformation leading to a better world and spreading the corruption of the language to the entire social organism and all its cells.

And:

If the old communists lived long enough to see the world of today, they would be devastated by the contrast between how little they themselves had managed to achieve in their antireligious war and how successful the liberal democrats have been. All the objectives the communists set for themselves, and which they pursued with savage brutality, were achieved by the liberal democrats who, almost without any effort and simply by allowing people to drift along with the flow of modernity, succeeded in converting churches into museums, restaurants, and public buildings, secularizing entire societies, making secularism the militant ideology, pushing religions to the sidelines, pressing the clergy into docility, and inspiring powerful mass culture with a strong antireligious bias in which a priest must be either a liberal challenging the Church of a disgusting villain.

After the US election, Prof. Legutko agreed to answer a few questions from me via e-mail. Here is our correspondence:

RD: What do you think of Donald Trump’s victory, especially in context of Brexit and the changing currents of Western politics?

RL: In hindsight, Trump’s victory seems logical as a continuation of a more general process that has been unveiling in the Western World: Hungary, Poland, Brexit, possible political reshufflings in Germany, France, Austria, etc. What this process, having many currents and facets, boils down to is difficult to say as it appears more negative than positive. More and more people say No, whereas it is not clear what exactly they are in favor of. What seems to be common in the developments in Europe and the US is a growing mistrust towards the political establishment that has been in power for a long time. People have a feeling that in many cases this is the same establishment despite the change of the governments.

This establishment is characterized by two things: first, both in the US and in Europe (and in Europe even more so) its representatives unabashedly declare that there is no alternative to their platform, that there is practically one set of ideas — their own — every decent person may subscribe to, and that they themselves are the sole distributors of political respectability; second, the leaders of this establishment are evidently of the mediocre quality, and have been such long enough for the voters to notice.

Because the ruling political elites believe themselves to steer the society in the only correct political course it should take, and to be the best quality products of the Western political culture, they try to present the current conflict as a revolt of the unenlightened, confused and manipulated masses against the enlightened elites. In Europe it sometimes looks like an attempt to build a new form of an aristocratic order, since a place in the hierarchy is allotted to individuals and groups not according to their actual education, or by the power of their minds, or by the strength of their arguments, but by a membership in this or that class. The new aristocrats are full of contempt for the riffraff, do not mince words to bully them, use foul language, break the rules of decency — and doing all this does not make them feel any less aristocratic.

It is, I think, this contrast between, on the one hand, arrogance with which the new aristocrats preach their orthodoxy, and on the other, a leaping-to-the-eye low quality of their leadership that ultimately pushed a lot of people in Europe and the US to look for alternatives in the world that for too long was presented to them as having no alternative.

When eight years ago America elected as their president a completely unknown and inexperienced politician, and not exactly an exemplar of political virtue to boot, this choice was universally acclaimed as the triumph of political enlightenment, and the president was awarded the Nobel Prize in advance, before he could do anything (not that he did anything of value afterwards). The continuation of this politics by Hillary Clinton for another eight years would have elevated this establishment and their ideas to an even stronger position with all deplorable consequences.

For an outside observer like myself, America after the election appears to be divided but in a peculiar way. On the one side there is the Obama-Clinton America claiming to represent what is best in the modern politics, more or less united by a clear left-wing agenda whose aim is to continue the restructuring of the American society, family, schools, communities, morals. This America is in tune with what is considered to be a general tendency of the modern world, including Europe and non-European Western countries. But there seems to exist another America, deeply dissatisfied with the first one, angry and determined, but at the same time confused and chaotic, longing for action and energy, but unsure of itself, proud of their country’s lost greatness, but having no great leaders, full of hope but short of ideas, a strange mixture of groups and ideologies, with no clear identity or political agenda. This other America, if personified, would resemble somebody not very different from Donald Trump.

Trump won 52 percent of the Catholic vote, and over 80 percent of the white Evangelical Christian vote — this, despite the fact that he is in no way a serious Christian, and, on evidence of his words and deeds, is barely a Christian at all. Many Christians are understandably relieved that the state’s ongoing assault on the churches and on religious liberty in the name of sex-and-gender ideology, will probably be halted under the new president. From your perspective, should US Christians be hopeful about their prospects under a Trump presidency, or instead wary of being tempted by a false prophet?

Christians have been the largest persecuted religious group in the non-Western world, but sadly they have also been the largest victimized religious group in those Western countries that have contracted a disease of political correctness (which in practice means almost all of them). Some Western Christians, including the clergy, abandoned any thought of resistance and not only capitulated but joined the forces of the enemy and started disciplining their own flock. No wonder that many Christians pray for better times hoping that at last there will appear a party or a leader that could loosen the straitjacket of political correctness and blunt its anti-Christian edge. It was then to be expected that having a choice between Trump and Clinton, they would turn to the former. But is Trump such a leader?

Anti-Christian prejudices have taken an institutional and legal form of such magnitude that no president, no matter how much committed to the cause, can change it quickly. Today in America it is difficult even to articulate one’s opposition to political correctness because the public and private discourse has been profoundly corrupted by the left-wing ideology, and the American people have weaned themselves from any alternative language (and so have the Europeans). Any movement away from this discourse requires more awareness of the problem and more courage than Trump and his people seem to have. What Trump could and should do, and it will be a test of his intentions, are three things.

First, he should refrain from involving his administration in the anti-Christian actions, whether direct or indirect, thus breaking off with the practice of his predecessor. Second, he should nominate the right persons for the vacancies in the Supreme Court. Third, he should resist the temptation to cajole the politically correct establishment, as some Republicans have been doing, because not only will it be a bad signal, but also display naïvete: this establishment is never satisfied with anything but an unconditional surrender of its opponents.

Whether these decisions will be sufficient for American Christians to launch a counteroffensive and to reclaim the lost areas, I do not know. A lot will depend on what the Christians will do and how outspoken they will be in making their case public.

Trump is a politician of the nationalist Right, but he is not a conservative in any philosophical or cultural sense. Had the vote gone only a bit differently in some states, today we would be talking about the political demise of American conservatism. Instead, the Republican Party is going to be stronger in government than it has been in a very long time — but the party has been shaken to its core by Trump’s destruction of its establishment. Is it credible to say that Trump destroyed conservatism — or is it more accurate to say that the Republican Party, through its own follies, destroyed conservatism as we have known it, and opened the door for the nationalist Trump?

Conservatism has always been problematic in America, where the word itself has acquired more meanings, some of them quite bizarre, than in Europe. A quite common habit, to give an example, of mentioning libertarianism and conservatism in one breath, thereby suggesting that they are somehow essentially related, is proof enough that a conservative agenda is difficult for the Americans to swallow. If I am not mistaken, the Republican Party has long relinquished, with very few exceptions, any closer link with conservatism. If conservatism, whatever the precise definition, has something to do with a continuity of culture, Christian and Classical roots of this culture, classical metaphysics and anthropology, beauty and virtue, a sense of decorum, liberal education, family, republican paideia, and other related notions, these are not the elements that constitute an integral part of an ideal type of an Republican identity in today’s America. Whether it has been different before, I am not competent to judge, but certainly there was a time when the intellectual institutions somehow linked to the Republican Party debated these issues. The new generations of the neocons gave up on big ideas while the theocons, old or new, never managed to have a noticeable impact on the Republican mainstream.

Given that there is this essential philosophical weakness within the modern Republican identity, Donald Trump does not look like an obvious person to change it by inspiring a resurgence of conservative thinking. I do not exclude however, unlikely as it seems today, that the new administration will need – solely for instrumental reasons – some big ideas to mobilize its electorate and to give them a sense of direction, and that a possible candidate to perform this function will be some kind of conservatism. Liberalism, libertarianism and saying ‘no’ to everything will certainly not serve the purpose. Nationalism looks good and played its role during two or three months of the campaign, but might be insufficient for the four (eight?) years that will follow.

Though the Republicans will soon have their hands firmly on the levers of political power, cultural institutions — especially academia and the news and entertainment media — are still thoroughly progressive. In The Demon in Democracy, you write that “it is hard to imagine freedom without classical philosophy and the heritage of antiquity, without Christianity and scholasticism [and] many other components of the entire Western civilization.” How can we hope to return to the roots of Western civilization when the culture-forming institutions are so hostile to it?

It is true that we live at a time of practically one orthodoxy which the majority of intellectuals and artists piously accept, and this orthodoxy — being some kind of liberal progressivism — has less and less connection with the foundations of Western civilization. This is perhaps more visible in Europe than in the US. In Europe, the very term “Europe” has been consistently applied to the European Union. Today the phrase “more Europe” does not mean “more classical education, more Latin and Greek, more knowledge about classical philosophy and scholasticism”, but it means giving more power to the European Commission. No wonder an increasing number of people when they hear about Europe associate it with the EU, and not with Plato, Thomas Aquinas or Johann Sebastian Bach.

It seems thus obvious that those who want to strengthen or, as is more often the case, reintroduce classical culture in the modern world will not find allies among the liberal elites. For a liberal it is natural to distance himself from the classical philosophy, from Christianity and scholasticism rather than to advocate their indispensability for the cultivation of the Western mind. After all, these philosophies – they would say — were created in a pre-modern non-democratic and non-liberal world by men who despised women, kept slaves and took seriously religious superstitions. But it is not only the liberal prejudices that are in the way. A break-up with the classical tradition is not a recent phenomenon, and we have been for too long exposed to the world from which this tradition was absent.

There is little chance that a change may be implemented through a democratic process. Considering that in every Western country education has been, for quite a long time, in a deep crisis and that no government has succeeded in overcoming this crisis, a mere idea of bringing back classical education into schools in which young people can hardly read and write in their own native language sounds somewhat surrealist. A rule that bad education drives out good education seems to prevail in democratic societies. And yet I cannot accept the conclusion that we are doomed to live in societies in which neo-barbarism is becoming a norm.

How can we reverse this process then? In countries where education is primarily the responsibility of the state, it is the governments that may — hypothetically at least — have some role to play by using the economic and political instruments to stimulate the desired changes in education. In the US – I suspect — the government’s role is substantially more reduced. So far however the European governments, including the conservative ones, have not made much progress in reversing the destructive trend.

The problem is a more fundamental one because it touches upon the controversy about what constitutes the Western civilization. The liberal progressives have managed to impose on our minds a notion that Christianity, classical metaphysics, etc., are no longer what defines our Western identity. A lot of conservatives – intellectuals and politicians – have readily acquiesced to this notion. Unless and until this changes and our position of what constitutes the West becomes an integral part of the conservative agenda and a subject of public debate, there is not much hope things can change. The election of Donald Trump has obviously as little to do with Scholasticism or Greek philosophy as it has with quantum mechanics, but nevertheless it may provide an occasion to reopen an old question about what makes the American identity and to reject a silly but popular answer that this identity is procedural rather than substantive. And this might be a first step to talk about the importance of the roots of the Western civilization.

You have written that “liberalism is more about struggle with non-liberal adversaries than deliberation with them.” Now even some on the left admit that its embrace of political correctness, multiculturalism, and so-called “diversity,” is partly responsible for Trump’s victory. How do Brexit and Trump change the terms of the political conversation, especially now that it has been shown that there is no such thing as “the right side of history”?

Liberalism, despite its boastful declarations to the contrary, is not and has never been about diversity, multiplicity or pluralism. It is about homogeneity and unanimity. Liberalism wants everyone and everything to be liberal, and does not tolerate anyone or anything that is not liberal. This is the reason why the liberals have such a strong sense of the enemy. Whoever disagrees with them is not just an opponent who may hold different views but a potential or actual fascist, a Hitlerite, a xenophobe, a nationalist, or – as they often say in the EU – a populist. Such a miserable person deserves to be condemned, derided, humiliated and abused.

The Brexit vote could have been looked at as an exercise in diversity and, as such, dear to every pluralist, or empirical evidence that the EU in its present form failed to accommodate diversity. But the reaction of the European elites was different and predictable – threats and condemnations. Before Brexit the EU reacted in a similar way to the non-liberals winning elections in Hungary and then in Poland, the winners being immediately classified as fascists and the elections as not quite legitimate. The liberal mindset is such that accepts only those elections and choices in which the correct party wins.

I am afraid there will be a similar reaction to Donald Trump and his administration. As long as the liberals set the tone of the public debate, they will continue to bully both those who, they say, were wrongly elected and those who wrongly voted. This will not stop until it becomes clear beyond any doubt that the changes in Europe and in the US are not temporary and ephemeral and that there is a viable alternative which will not disappear with the next swing of the democratic pendulum. But this alternative, as I said before, is still in the process of formation and we are not sure what will be the final result.

There will be elections in several key European nations next year — Germany and France, in particular. What effect do you expect Trump’s victory to have on European voters? How do you, as a Pole, view Trump’s fondness for Vladimir Putin?

From a European perspective, Clinton’s victory would have meant a tremendous boost to the EU bureaucracy, its ideology and its “more Europe” strategy. The forces of the self-proclaimed Enlightenment would have gone ecstatic and, consequently, would have made the world even more unbearable not only for conservatives. The results of the elections must have shaken the EU elites, and from that point of view Trump’s victory was beneficial for those Europeans like myself who fear the federalization of the European Union and its growing ideological monopoly. There is more to happen in Europe in the coming years so the hope is that the EU hubris will suffer further blows and that the EU itself will become more self-restrained and more responsive to the aspirations of European peoples.

Trump’s foreign policy, especially vis-à-vis Russia, is still to be formulated and so far is a subject of speculation. The fact that he made some warm remarks about Putin during the campaign does not make me happy. Unfortunately, it is not only Trump that seems to have some sympathy for Putin. Let us not forget that it was Obama who had reset the American relations with Russia and thus indirectly facilitated the Russian aggressive actions. Hillary Clinton would have probably not changed Obama’s course. The days of America’s defying Russian imperialism seem to be over, no matter who becomes the US President.

The situation in Europe is no different. France, Italy, and Germany have been traditionally pro-Russian and their response to Russian imperialism was not as strong as one could expect. Should Putin attack the Baltic States — which are, let us remember, the NATO members — NATO will certainly not react militarily, and such signals have been already sent. So, all in all, the East Europeans do not feel secure, and the Western Europeans do not care. Russia is becoming stronger and more determined to regain its former political influence while the Western alliance on both sides of the Atlantic have neither the will nor the instruments to stop her. This is the reason why the new Polish government has launched a program of strengthening the defense system, which includes, among others, the US military presence on the Polish territory. If Trump endorses and then agrees to increase this presence, the Poles will – I am sure – forgive him those rather foolish and, let us hope, accidental remarks about Putin he made in the heat of the campaign.

Again, Prof. Ryszard Legutko develops these themes in his powerful new book The Demon In Democracy. Highly recommended. It is rare to find a book of political philosophy that is so sharply written, so accessible to the general reader, so relevant to its time, and so prophetic.

November 19, 2016

Brokeback Mountain, Hamilton, Art

I know we’re all Hamiltoned out, but please, allow me another word about Hamilton and the power of art to open our eyes to things we would not otherwise have seen. Back in 2005, I was a columnist at The Dallas Morning News. Then as now, when I wrote about same-sex marriage, I defended and advocated for tradition. Brokeback Mountain was then in theaters, and I didn’t want to see it for a couple of reasons. One, I didn’t think it would interest me, given the subject matter, and two, the nonstop cheerleading in the media for the movie, and for homosexuality, irritated me.

But I was a columnist who wrote often about cultural politics, and the movie occasioned an important cultural moment, whether I liked it or not. So I felt compelled to see it.

Here is what I wrote about the film in the newspaper, on December 29, 2005:

Seen the gay cowboy movie yet? I have, though I hadn’t planned to because the rapturous reviews made Brokeback Mountain sound like a film that delivered yet another fierce left hook across the jaw of homophobic America. Ho hum.

I’m not interested in propaganda, whether pro-gay or anti-gay, and I get tired of the way the news and entertainment media find it difficult to discuss homosexuality without propagandizing. And some of the loudest conservative voices on gay issues are just about as bad.

What gets lost in the culture-war blitzkrieg over homosexuality are the complex and ambiguous truths that real people live and struggle with. Art that reduces messy humanity to slogans and arguments is not art at all, but sentimentality, kitsch, anti-art – in a word, propaganda.

My friend Victor Morton turned me around. On his “Right-Wing Film Geek” blog, Victor wrote a long, impassioned post that said, in effect, Don’t believe the ‘Brokeback’ hype, from either side! The film is good, not great, Victor argued, but what makes it worthwhile is its fidelity to the tragic truth of its characters, not its usefulness to anybody’s cause.

Intrigued, I found on the Internet a link to the Annie Proulx short story on which the movie is based and was shocked by how good it was, especially at embodying the “concrete details of life that make actual the mystery of our position here on earth” – Catholic writer Flannery O’Connor’s description of what true artistry does. Though director Ang Lee’s tranquil style fails to capture the daemonic wildness of Ms. Proulx’s version, I came away from the film thinking, this is not for everybody, but it really is a work of art.

Brokeback Mountain is the story of two young cowboys, Ennis Del Mar and Jack Twist, who meet in a 1960s summer job tending sheep on the mountain. They fall in love, then upon returning to the world, go their separate ways, marry and start families. A few years later, they resume their intensely sexual affair – visually, this is a rather chaste film – but with terrible consequences for themselves and the wives and children they deceive. The film climaxes violently and tragically, and it’s this that has the critics lauding it as a cinematic cri du coeur for tolerance and acceptance of homosexuality.

But Brokeback is not nearly that tidy. True, the men begin their doomed affair in a time and place where homosexuality was viciously suppressed, and so they suffer from social constrictions that make it difficult to master their own fates. But it is also true that both men are overgrown boys who waste their lives searching for something they’ve lost, and which might be irrecoverable. They are boys who refuse to become men, or to be more precise, do not, for various reasons, have the wherewithal to understand how to become men in their bleak situation.

It is impossible to watch this movie and think that all would be well with Jack and Ennis if only we’d legalize gay marriage. It is also impossible to watch this movie and not grieve for them in their suffering, even while raging over the suffering that these poor country kids who grew up unloved cause for their families. As the film grapples with Ennis’ pain, confusion and cruelty, different levels of meaning unspool – social, moral, spiritual and erotic. In the end, Brokeback Mountain is not about the need to normalize homosexuality, or “about” anything other than the tragic human condition.

O’Connor once wrote that you don’t have to have an educated mind to understand good fiction, but you do have to have “at all times the kind of mind that is willing to have its sense of mystery deepened by contact with reality, and its sense of reality deepened by contact with mystery.” The mystery of the human personality can never be fully plumbed, only explored. To the frustration of ideologues, artists like Annie Proulx and Ang Lee undertake a journey to those depths and return to tell the truth about what they’ve seen – which is not necessarily what any of us wants to hear.

As Ms. O’Connor taught, “Fiction is about everything human and we are made out of dust, and if you scorn getting yourself dusty, then you shouldn’t try to write fiction.”

Or read it. Or watch it.

I think that column holds up pretty well. Brokeback Mountain did not change my mind one bit about same-sex marriage, because my views are not based on emotion. What it did was to give me more empathy, to help me to grasp that these things we argue about abstractly are rooted in real lives, and real suffering. (This is something I wish folks on the other side of the debate would consider too.) The movie helped me to understand the cruelty of the closet, and the damage that secrets and lies did to the people who chose or felt compelled to tell them live by them — as well as the damage done to innocent people caught up in the drama (in the movie’s case, the wives of Ennis and Jack). The closet is all but gone, and I’m glad of that, even though I’m an orthodox Christian who holds orthodox Christian convictions about human sexuality, and ideally would like to see them reflected in family law and custom. Brokeback Mountain illuminates better than any polemical argument or piece of sappy agitprop why we are all better off — not just gays and lesbians, but the common good — with the closet consigned to history.

Now, I do not say that to start an argument or even a discussion thread about sexuality (and if you post a comment attempting to do that, I will spike it). I say it to make a point about how serious art challenges us to go deeper into the human experience, and to imagine things that likely never would have occurred to us — including the commonality of our humanity. I almost didn’t see this film because I hated the way the media portrayed it as sentimental and propagandistic. I don’t waste time at movies like that, even if the sentiment and propaganda are designed to appeal to my own beliefs and prejudices. I don’t care to see Brokeback Mountain again, but I came out of that movie changed in ways I didn’t expect, and I’m glad for it. If I had had any reason to think that I was going to get booed in the theater, or be singled out there and lectured, however politely, about my backwards, homophobic views — well, I would never have bothered to go see the thing, because really, who the hell needs that?

I wonder if Hamilton will now be regarded in the same politicized light by people because of the events in the theater on Friday night. If so, and if the musical is as good as critics (including critics on the political and cultural right) have said, that would be a real loss. Art should be allowed to speak for itself, and we should all be given a chance to hear what it says, without anybody yelling in our ear.

UPDATE: This, from the actor, rock musician, and (anti-Trump) liberal activist Steve Van Zandt:

>Completely inappropriate. Theater should be a safe haven for Art to speak. Not the actors. He needs to apologize to Mike Pence @Lin_Manuel

— Stevie Van Zandt (@StevieVanZandt) November 19, 2016

His whole Twitter feed on this subject is well worth reading.

View From Your Table

Mexico City, Mexico

The reader writes:

In Cafe Tecuba, established 1912. I’m having one of their specialties, chicken with tortilla chips covered in salsa verde and topped with cheese. My daughter is eating chicken barbecued Oaxacan style.

Why The ‘Hamilton’ Dust-Up Matters

Well, you knew this was coming:

The Theater must always be a safe and special place.The cast of Hamilton was very rude last night to a very good man, Mike Pence. Apologize!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) November 19, 2016

Though there may have been some very clever trolling in Trump’s tweet, Trump’s reaction to the Hamilton insult — which I called reprehensible here — is an example of why Trump is going to make things worse in some respects. He and his enemies bring out the worst in each other, and are making the public square less inhabitable by us all.

Too much to hope Trump gets thicker skin, but he has to. There’s going to be a lot of this. These people’s world has just been upended.

— David Freddoso (@freddoso) November 19, 2016

Here’s what I mean. Let’s stipulate that many on the left are far too quick to denounce as bigotry speech that they don’t like. One admirable thing about Trump is that he doesn’t care what they think. But Trump routinely takes that too far. It’s great not to be cowed by political correctness, but Trump doesn’t have any sense of the difference between p.c. and plain old courtesy and decency in speech. The examples of this are legion. What has changed in American life is that we have become far more accepting of vulgarity and discourtesy in public. To his very great credit, President Obama has always risen above that, even when he was not shown the same respect.

To many Americans, myself included, Hamilton audience and cast made themselves look like self-righteous jerks with their display last night. Trump should have let it pass, and allowed the jerks to do further damage to themselves. It would have been the presidential thing to have done. But now he’s ramping it up, and making himself look undignified and beneath the office to which he was elected. I have a sinking feeling this is going to be the pattern for the next four years.

I see lots of people on the left — commenters on this blog, people on Twitter, etc. — getting all indignant, saying that the descent of fascism onto America is such a crisis that we have no reason to respect the ordinary norms of civility. How can you complain about people booing Mike Pence at the theater when the administration in which he will serve is a nest of white nationalists who are going to take everything away from gays and minorities?! Well, assuming that that is true — which I absolutely do not — then you ought to fight even harder to maintain the structures and norms of civil society. One of the blessings of civil society, when it’s working as it should, is the ability of people of different, and sometimes antagonistic, views and backgrounds to gather in the public square as a community.

One reason why the no-platforming, safe-space p.c. craziness on campus is so destructive is that it makes it impossible for a university to do what it’s supposed to do. They treat a space for education as if it were a temple, and attempt to protect it from heretics and heathens. A theater has a different function than a college campus, but when it functions as it is supposed to do, it is a place where all people can come to be entertained, certainly, and, one hopes, raised out of themselves, enlightened, and enlightened together with everyone else in the audience. To make the theater a place where our political opponents cannot come to experience art in community is to place them outside the community. It is to regard the performance on stage as a sacred rite to which unbelievers may not be witness. It is to make a religion of art.

To be sure, the separation between art and religion is not clean and clear. The Greeks considered theater to be a religious rite. At its highest, art, like the rites of religion, serves as an icon, providing a window onto the transcendent. But art in our time and place is unlike religion in that its rites are not meant only for those initiated into the cult. In Catholic and Orthodox Christianity, for example, one can only receive communion — that is, participate in the most intimate rite of the religion — if one has been baptized and confirmed (initiated), and is in a state of ritual purity. In Islam, one cannot transgress the borders of the holy city of Mecca unless one is a believer. This kind of thing is normal and natural. Those borders define what it means to be a member of the community.

Those religions, though, welcome unbelievers to participate in other public rituals. For example, neither Orthodoxy nor Catholicism would deny a respectful unbeliever access to their services to hear Scripture read and the word of God preached. Non-Muslims are welcome at Friday prayers in mosques. In fact, Christians and Muslims often invite non-believers to their services. This is well and good. A Muslim or Christian believer hopes that what the non-believer sees, hears, and feels at the prayer ritual will compel him to learn and experience more of the religion, and ultimately to embrace it. Then and only then will he be permitted to commune at a deeper level (e.g., receiving the Holy Sacrament, making hajj to Mecca).

That’s religion. Should art work that way? I mean, is it the case that liberals believe that artistic performances — theater, music, and so forth — must be limited only to people who share their moral and political views? If I were worried that the Trump administration was going to be hostile to minorities and gays, I would have gone out of my way to make Mike Pence feel welcome at Hamilton, and hoped and prayed that the power of art moved his heart and changed his mind. But that’s not how the audience saw it. They wanted to show Pence that he is not part of their community, and the cast took it upon itself to attempt to catechize Pence at the end of the show. (And people say Evangelical movies are bad because they can’t let the art speak for itself, they have to underline the moral and put an altar call at the end!).

Let’s think about it in religious terms. If you were a pastor or member of a church congregation, and a Notorious Sinner came to services one Sunday, would you boo him as he took his seat in a pew? Do you think that would make him more or less likely to value the congregation and accept the message from the sermon? And if you were the pastor, would you think it helpful to single the Notorious Sinner out among the congregation, and tell him, in a bless-your-heart way, that you hope he got the point of the sermon (him being a bad man and all)? You should not be surprised if the Notorious Sinner left with his heart hardened to the religion and that congregation. Any good that might have been done toward converting him to the congregation’s and the pastor’s way of belief would almost certainly not come to fruition.

Look, I’m not saying that churches should downplay or throw aside their sacred beliefs to be seeker-friendly. Sure, congregations should treat visitors with respect, but the church exists to fulfill a particular purpose, to carry out a specific mission. Its behavior must be consonant with that mission. Nevertheless, a church that repudiates hospitality to guests, and thereby chooses to be a museum of the holy, violates its purpose, and diminishes its power to change the world.

So, do liberals want theaters (and campuses) to be museums of the holy, where the already converted commune with each other? Does one have to be baptized into the mystery cult of liberalism before one is allowed in the door? Because that’s the message from last night’s display at the Richard Rodgers Theater. And if this kind of thing keeps up — Trump will do nothing to stop it, because it benefits him and his tribe — America will lose one more gathering place for all of its people.

This is by no means only the fault of the left. As I wrote back in 2009, the shocking breach of decorum that occurred when a GOP House member shouted out “You lie!” at President Obama during his first State of the Union address did Obama no harm, but it disgraced that man, and lowered the dignity of the House. The political right has been playing this ugly game for a long time. Nobody has clean hands.

We are teaching ourselves, though, to love the mud, and to consider our own filthiness evidence of purity. We think our own feelings justify anything. What the cast and crowd at Hamilton did last night is no different in principle from pro-life fanatics demonstrating outside the homes of abortion doctors, and saying that violating private space is minor compared to the horror of abortion. There may be a certain logic to that: after all, if fascism really is descending on America, what’s the big deal about booing a fascist politician? if abortion really is murder, then protesting outside the home of a hit man is small beer. Right? Consider, though, that social order, and social peace, is often maintained by people consenting, perhaps unconsciously, not to push their beliefs to their logical conclusions.

If you believe that religion poisons everything, then it would make sense to you to pass laws forbidding religious observance. If you believe that to fail to confess that Jesus Christ is the Son of God results in eternal damnation, it would make sense to pass laws forbidding heresy. Some states in history have done exactly that, with terrible outcomes. There are times and places when we have to draw sharp boundaries and enforce them, but we should be very reluctant to sacralize the public square, and we should be extremely wary about advancing the politicization of life.

A theater on Broadway turned into a sacred temple of multicultural liberalism is not progress. A burger joint on Harvard Square making sandwich consumption a political act is not making this a better place.

It’s not the America I want, but it looks like the America that the Trump right and the anti-Trump left are going to give us.

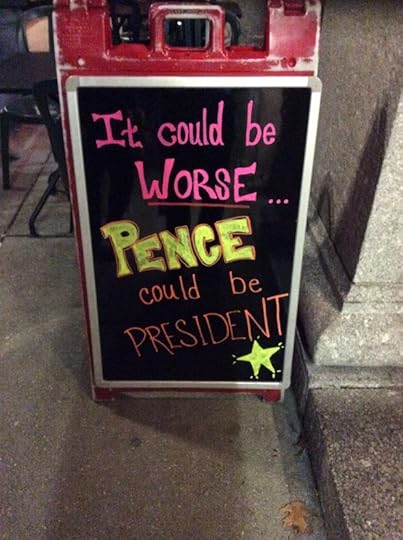

Photo sent in by a reader

UPDATE: Sam M.:

Rod, this is what border policing looks like. This is what culture building looks like. They are willing to do the work, and what we are seeing on the Right is a growing recognition of that reality.

Mark Cuban’s sports teams won’t stay in his hotels. Fine. Whatever. But here is a longer list: https://www.google.com/amp/amp.slate.com/blogs/moneybox/2016/11/18/a_list_of_all_of_the_companies_sports_team_and_chefs_that_won_t_do_business.html?client=safari

The danger for the BenOp is that there’s a fine line separating it from BubbleOp. The anti-Trump folks living in one now.

Next step will be hotels and restaurants refusing to serve the administration when they are in town. First it’ll be a waitress or a bus boy. They will be treated as celebrities. The desire for virtue signaling will be unquenchable. Major corporations will get on board. And the Right will begin demanding infringement of the Left’s right of association.

Thing is, the move from victory to annihilation, loser to victim, used to take a generation or two. Now it takes a week.

UPDATE.2: A reader suggested I take a look at this CNN report featuring interviews with (white) citizens of Sen. Jeff Sessions’s hometown of Heflin, Alabama. These are clearly working class people. Maybe even a couple of them are poor, judging by the way they look. And yet, they acquit themselves well. Notice especially what two people interview have to say about changing racial attitudes. That’s more sophisticated and human than you’d hear from just about anybody within a five-mile radius of the Richard Rodgers Theater, I’d wager. I can confidently say I would rather that this country be ruled by the voters of Heflin, Alabama, than by the audience at last night’s performance of Hamilton.

November 18, 2016

‘Hamilton’ & Hate

This makes me angrier than it should:

Vice-president elect Mike Pence went to see the hip-hop musical “Hamilton” on Broadway Friday night, and the performance was disrupted when the audience wouldn’t stop booing him.

Upon arrival at the Richard Rodgers Theater, he was loudly booed — although some audience members also cheered him on. As journalist Mark Harris pointed out on Twitter, playgoers are typically largely tourists from other areas.

Here’s Pence getting booed as he gets to his seats at Hamilton pic.twitter.com/IRQG68x1sB

— David K (@dkipke12) November 19, 2016

More from the story:

At the end of the show, the cast addressed his presence, with Brandon Victor Dixon saying “Vice President Elect Pence, welcome. Thank you for joining us at Hamilton-An American Musical. We are the diverse America who are alarmed and anxious that your new administration will not protect us, our planet, our children, our parents, or defend us and uphold our inalienable rights. We hope this show has inspired you to uphold our American values, and work on behalf of ALL of us.”

Video of this:

Tonight, VP-Elect Mike Pence attended #HamiltonBway. After the show, @BrandonVDixon delivered the following statement on behalf of the show. pic.twitter.com/Jsg9Q1pMZs

— Hamilton (@HamiltonMusical) November 19, 2016

Such repulsive sanctimony from the cast and from the audience. The man was elected vice president of the United States, and this is how they treat him.

Don’t think people outside your cultural bubble aren’t noticing all this, taking note, and learning. You think your emotions and your passion entitles you to crap on everybody else, and not even to show them basic respect. You people saw about ten days ago where that gets you, but you won’t stop and can’t stop politicizing everything, filling it with your spite, even a night out at the theater.

You are taking America to the brink.

UPDATE:

Trump/Pence are appointing white nationalists & planning to gut civil & women’s rights. Shame on us if we ever STOP booing. #Hamilton

— Jessica Valenti (@JessicaValenti) November 19, 2016

Trump/Pence are appointing white nationalists & planning to gut civil & women’s rights. Shame on us if we ever STOP booing. #Hamilton

— Jessica Valenti (@JessicaValenti)

In Weimar America: ‘Only Brokenness’

A reader of this blog, a college professor, sent me this e-mail this afternoon. I publish it with his permission, editing it very slightly to protect his privacy:

A few days after the election, a member of an academic listserv I belong to emailed the group with what has become by now the standard progressive response: lamenting that fascism has won, berating all Trump’s supporters and fellow travelers, and asking us to support a statement of “safety and inclusion” for all our members who were members of some “underrepresented group.”

For the first time since I joined the group, I replied to all with a statement agreeing that Trump’s election is disconcerting for many reasons (I was and remain a vocal Trump opponent; I voted third party), but offering a qualified defense of his supporters. I explained that I grew up in the Midwest and that there are many logical, rational reasons someone in that region (or indeed any region) might support Trump. I further explained that most of my students at this college were Trump supporters, and that not a one could be described as a bad person. Quite the opposite, in fact: they are some of the kindest people I’ve ever known.

I suggested to my colleagues that if they are truly so disturbed by the election, then they should stop the obsessive focus on electoral politics and turn inward to the truly important work: family, friends, neighborhood, and so on. I suggested they plant a tree and play with their children, and asserted that such work would be much better for the world than yet another anti-Trump screed. In other words, I suggested something like the Benedict Option.

You can probably guess what happened next. I was savaged. I was called a racist, a sexist, and a bigot merely for my halfhearted defense of Trump supporters. Bear in mind I stated explicitly in my email that I believed Trump was a decadent and immoral buffoon who could do little good for his supporters. No matter: any defense of Those In Error is error itself, apparently.

Perfectly decent college professors piled on me in emails, insulting my students and saying that nothing good they did in churches or homes could overcome the evil of their vote for Trump. Worse, though, they told me that my BenOp-ish suggestions revealed that I was merely “privileged” and that my rejection of electoral politics was “an insult” to (get ready for it) “queer, Latinx, trans, non-cis, Muslim” populations. One particularly memorable line: “It must be nice to be able to plant a tree and not be shot or put into an internment camp.” After that, I was summarily banned from the listserv.

I admit I was hurt. But more than that, I was simply amazed that scholars and professors could so quickly descend into a hysterical mob focused on outing thought criminals, and I was left utterly disconsolate about the future of this country’s democratic citizenship. It seems to me that we have passed some sort of terrible Rubicon, and that social trust has been permanently negated. Recall the opening of After Virtue, when MacIntyre speaks of the loss of any common moral language that allows social cooperation in morally fungible matters. He was right, of course, but it’s so much worse now: today other people are not just speaking a different moral language but have become moral enemies.

Unsure where to turn, I decided to reread the book that affected me most powerfully in 2015: Laurus. It was just as beautiful in a second read, and this time, with the election in the back of my mind, the book seemed even more powerful. You might recall we corresponded last fall about the “vertical motion” section, in which Arseny is told that he must put aside worldly concerns and focus on the work of Christ. That’s still important, but what stood out this time was Ambrogio’s discussion with Arseny on the nature of time. From pages 228-9:

I am going to tell you something strange. It seems ever more to me that there is no time. Everything on earth exists outside of time… I think time is given to us by the grace of God so we will not get mixed up, because a person’s consciousness cannot take in all events at once. We are locked up in time because of our weakness… O friend, I do not question the necessity of time. We simply need to remember that only the material world needs time.

From page 235:

I think, said Ambrogio, that it is not time that runs out, but the occurrence. An occurrence expresses itself and ceases its own existence.

And finally, from the last page:

You have already been in our land for a year and eight months, answers blacksmith Averky, but have understood a thing about it.

And do you understand it yourselves? asks Zygfryd.

Do we? The blacksmith mulls that over and looks at Zygfryd. Of course we, too, do not understand.

It seems to me that [author Evgeny] Vodolazkin captures something truly powerful about the Judeo-Christian secular split. When I taught at a Catholic college, our (priest) president used to joke that the Church moves so slowly because, when your time scale is eternity, you don’t get too bogged down in day-to-day stuff. The line got a laugh, but it’s also eerily accurate. My colleagues on the listserv (and, with a few exceptions, throughout my institution) are universally secular progressives. They have no “vertical motion” in the sense that we have it. This means their vertical motion — because everyone has something they aim toward, some telos — becomes electoral politics, and so each election takes on an eschatological veneer. It is the realm of their salvation and their redemption.

But for small-o orthodox believers, this is is unfathomable — and I mean this in the sense that we almost literally cannot comprehend it, just as they cannot comprehend our position. MacIntyre’s problem of incommensurability comes to the fore: we are not just speaking different moral languages; because the so-called Christian consensus has collapsed in the West, we now inhabit something like very different moral worlds. In their world, you bend nature to your will and make yourself a god and declare that tradition has no hold on your mind (or, increasingly, your body). In our world, you put yourself in harmony with nature and know that you are made in the image of God and declare that tradition is what shaped and shapes us. And most importantly: we admit our ignorance. We are not gods; we are fallen men, and we act like it.

We know that this election is a tiny blip in the plan of God, and that as Ambrogio says we “cannot take in all events at once,” and that we are “locked up in time because of our weakness.” We

know that only the material world needs time, in the right-side-of-history sense, because people of faith recognize patterns of circularity in the universe and in human events. Trumpism is an “occurrence,” and it will express itself and then cease. And then something else will take its place, and then something else and something else. For the secular progressive, these are the worldly battles being fought and they alone possess metaphysical importance. But people of faith take the larger view. Again to Laurus, page 330, with my emphasis:

Being a mosaic does not necessarily mean scattering into pieces, answered Elder Innokenty. It is only up close that each separate little stone seems not to be connected to the others. There is something more important in each of them, O Laurus: striving for the one who looks from afar. For the one who is capable of seizing all the small stones at once. It is he who gathers them with his gaze. That, O Laurus, is how it is in your life, too. You have dissolved yourself in God. You disrupted the unity of your life, renouncing your name and your very identity. But in the mosaic of your life there is also something that joins all those separate parts: it is an aspiration for Him. They will gather together again in Him.

It seems to me that an integral part of the Ben Op is this attempt to see from afar: to see, as much as possible, from the viewpoint of our Creator. This is why I encouraged my fellow academics to plant a tree and spend time with their children: those are attempts to transcend our meager lifetimes and see from afar. It speaks volumes that those suggestions were denounced as the words of a bigot. For modern secular progressivism, there is no view from afar. There is the mastery of nature and the will to power. I hesitate to denounce them because I am having just as much trouble seeing from their viewpoint as they are seeing from mine.

Perhaps, as Ambrogio says, there is no time. There is no before or after. There is God, and there is us divided from him in earthly form, and then reunited with him in death. Remember that when Ambrogio says the “city of saints” presents us with “the illusion of life,” Arseny replies: “No… they disprove the illusion of death.” When you take the long view, the view from afar, Trump’s election seems awfully minor. But to the people who banned me — who silenced me for my dissent from groupthink — there is no view from afar. There is only the here and now. My inability to see their viewpoint worries me just as much as their inability to see mine. There are no winners in the United States this month. There is, it seems to me, only brokenness.

I invite you to read that letter a second time, and to think about it.

Readers, I told you yesterday at length why I thought the Benedict Option was still urgently needed, why Trump’s election means very little in the long run. This professor’s e-mail powerfully underscores that. We are entering a period of intense conflict. I wish we were not, but wishing does not make it go away. Peter Burfeind, writing at The Federalist, makes the same point as the professor above, saying that many secular people, especially Millennials, answer their longing for transcendent meaning and purpose by elevating politics to a kind of religion. Burfeind predicts that in the Trump era, the left will double down on the dogma of the faith.

I believe that is true, though I wish it weren’t true. We need to avoid these conflicts if we can. Charity is not cowardice. But as with my professor correspondent, the conflicts will at times come to you. What will you do? How will you be prepared to respond? It will be very easy to respond to hatred with hatred, something that Christians, at least, are strictly commanded not to do. It will be easy for others to pretend that this isn’t happening, that everything will be fine if we just wait this out. That’s a delusion. People like the fanatics that threw the professor out of the group control the culture-making institutions. This is going to matter much more in the long run, as politics is downstream from culture. Politics will not save us or our faith. Rather, doing things like the professor suggests, as well as strengthening the church and community, and undertaking initiatives like starting new schools — this is what we must do, right now, to prepare. The Trump presidency might give us a few more years to prepare, but that’s the best we can hope from it — and I would say that if Trump were manifestly a saint. Social and religious conservatives must not make the same mistake that the left makes, and think of politics as the source of our salvation. I’ll have a lot more to say about this in The Benedict Option when it’s out next year.

In the meantime, don’t let the berserkers stand for all liberals. There are some strong voices on the left who are learning from recent events. Take Mark Lilla, the Columbia professor, who, in a chastened and chastening column in The New York Times, says that “the age of identity liberalism must be brought to an end.” More:

But the fixation on diversity in our schools and in the press has produced a generation of liberals and progressives narcissistically unaware of conditions outside their self-defined groups, and indifferent to the task of reaching out to Americans in every walk of life. At a very young age our children are being encouraged to talk about their individual identities, even before they have them. By the time they reach college many assume that diversity discourse exhausts political discourse, and have shockingly little to say about such perennial questions as class, war, the economy and the common good. In large part this is because of high school history curriculums, which anachronistically project the identity politics of today back onto the past, creating a distorted picture of the major forces and individuals that shaped our country. (The achievements of women’s rights movements, for instance, were real and important, but you cannot understand them if you do not first understand the founding fathers’ achievement in establishing a system of government based on the guarantee of rights.)

More:

This campus-diversity consciousness has over the years filtered into the liberal media, and not subtly. Affirmative action for women and minorities at America’s newspapers and broadcasters has been an extraordinary social achievement — and has even changed, quite literally, the face of right-wing media, as journalists like Megyn Kelly and Laura Ingraham have gained prominence. But it also appears to have encouraged the assumption, especially among younger journalists and editors, that simply by focusing on identity they have done their jobs.

That is the gospel truth. One more:

Finally, the whitelash thesis is convenient because it absolves liberals of not recognizing how their own obsession with diversity has encouraged white, rural, religious Americans to think of themselves as a disadvantaged group whose identity is being threatened or ignored. Such people are not actually reacting against the reality of our diverse America (they tend, after all, to live in homogeneous areas of the country). But they are reacting against the omnipresent rhetoric of identity, which is what they mean by “political correctness.” Liberals should bear in mind that the first identity movement in American politics was the Ku Klux Klan, which still exists. Those who play the identity game should be prepared to lose it.

Yes, as I’ve been saying. You can’t have identity politics on the left without calling up and legitimizing the same thing on the right. There are very powerful forces on the left — in media, academia, and entertainment — that do not want to recognize this basic truth. They will fight like mad dogs to maintain their illusion.

David Brooks writes today that

[w]e will have to construct a new national idea that binds and embraces all our particular identities.

I hope we can do that, to gather all the small stones with our gaze, so to speak, for the sake of peace and order. But traditionalists must not allow themselves to be lulled into a false sense of security. We may not consider ourselves enemies of the kind of people who went all Lord of the Flies on the professor above, but they most certainly consider themselves enemies to us, and they hold the heights of cultural power, which matters more than holding Capitol Hill. Plus, do not forget that all those who fight on our side are not our friends, but could easily lead us to ruin. If we are in a Weimar period in America, it is characterized as such by the fact that the center is fast-shrinking, and people are choosing sides on either extreme.

Again: prepare. You would do well to read Laurus, which is now out in paperback. It’s by no means a culture war book, not at all. It’s a book about a quest, and meaning. Here’s a link to the posts I’ve written about it over the past year. It’s the only work of literature I’ve ever read that made me want to pray every time I set it down.

Women Evangelical Influencers

As most readers know, I don’t know a lot about Evangelical culture, but I’ve enjoyed getting to know new Evangelical friends over the past year or two, researching the Benedict Option project. I consider myself a sympathetic outsider to conservative Evangelicals — a fellow traveler, you might say. Recently, one of those friends — a plugged-in Millennial — has been telling me that he expects most of American Evangelicalism eventually to abandon Christian orthodoxy on LGBT issues. His basic argument runs similar to the kind of argument you hear from conservative Catholics regarding a particular fault of Evangelicalism: this is the consequence of a weaker ecclesiology, one that have the strength to withstand popular culture.

The fact that Catholicism and Orthodoxy both have very strong ecclesiologies has not prevented most US Catholics and US Orthodox Christians from being far more liberal than average Americans are on LGBT matters, in contradiction to what both churches teach. Their ecclesiology has not protected the flock from abandoning orthodox Christian truth on this matter. I’m not sure what that has to say about my friend’s theory, but I’m hoping some of you readers — Evangelical, Catholic, and Orthodox — will have something helpful to say about it.

The reason I bring this up here is as a response to Christianity Today’s long, fascinating article about the Evangelical writer and blogger Jen Hatmaker, who recently caused a big stir by coming out in favor of gay marriage and full affirmation of sexually active LGBT Christians. It turns out that figures like Hatmaker, a laywoman, have influence over more Evangelicals than do some pretty well known figures. Excerpts:

“If you had to ask, ‘Who’s Jen Hatmaker?’ it’s time to be more directly invested in the spiritual nurture of half your church,” tweeted Jen Wilkin last month. The women’s ministry leader was responding to the wave of Christian reactions to news that LifeWay Christian Stores had stopped selling books by Hatmaker—one of the biggest writers and speakers among today’s generation of evangelical women—after she spoke out in support of same-sex marriage.

Hatmaker’s popularity underscores how women’s ministry has transformed in the 21st century. Christian women increasingly look to nationally known figures for spiritual formation and inspiration—especially when they don’t see leaders who look like them stepping up in their own churches.

While various evangelical subcultures may find different female teachers filling their social media feeds and Amazon recommendations (Austin-based Hatmaker seems especially popular among white women in the South and Midwest), the numbers show that the top names in women’s ministry rival or even outdraw high-profile televangelists and megachurch pastors.

More:

As Wilkin pointed out, while most evangelical women know their Tim Kellers from their Rick Warrens, male pastors aren’t expected to parse female teachers.

“The bookshelves in their offices contain no books by contemporary female authors, and their sermons typically do not reference female voices, other than the usual suspects of Elisabeth Elliot or Corrie ten Boom—both dead, for the record,” said Wilkin, a minister at The Village Church in Texas. “The typical church organizational structure tends to segregate women’s ministry as an autonomous unit—a mysterious kingdom that operates according to its own set of rules.”

That kingdom has expanded in the Internet era, when ambitious women can draw mass followings around their writings, teachings, and events without the restrictions of geography, official titles, or other structures.

And:

The biggest names in women’s ministry—from Hatmaker to authors like Shauna Niequist—remain intimately involved in their own local churches, and most have Bible college or seminary degrees. Still, without traditional structures in place, followers can find themselves wondering about a leader’s stance on a particular issue or surprised by her sudden change in approach. (This scenario can happen within ecclesiastical or organizational hierarchies from time to time, but doctrinal policies usually give followers a better sense of what to expect.) Hatmaker’s fans include women who celebrate her decision to affirm same-sex marriage, as well as many who are, in her words, “angry or shocked or confused” by it.

Again, because this world is entirely foreign to me, I’m not taking a position on it, but rather asking you readers for your insights. For years Evangelical friends have told me that Evangelicals run the risk of falling hard for a charismatic teacher, and not being as discerning as they ought to be about his theological errors or faults. With the women’s ministry as defined by Kate Shelnutt’s CT article, is this a particular problem, or is it the same problem in general?

I don’t know if you saw it, but the popular women’s lay Christian leader Glennon Doyle Melton, who announced earlier this year that she was leaving her husband of 14 years, said on Sunday that she is now dating a woman, the soccer star Abby Wambach. Says the Chicago Tribune:

Why is this news?

Couple of reasons: One, millions have followed Melton’s “brutiful” (her word for brutal + beautiful) life story — a story that includes a decades-long battle with substance abuse and bulimia, three lovely children, a marriage beset by infidelity and, most recently, a separation from her husband — through her books, her Momastery blog, her social media posts and her public speaking appearances.

Two, her new love is Abby Wambach, the two-time Olympic gold medalist and Women’s World Cup champion.

“Abby is deeply sensitive and kind,” Doyle writes on Facebook and Instagram. “The kids call her an M&M because she looks tough on the outside but inside she’s really mushy and sweet. Abby’s brave. Not just with her words but with her entire being. She has never been afraid to be herself, even when the world told her not to be. I learn from her everyday about the woman I want to become.”

The posts read like the beginning of a dialogue, which is partly what endears Melton to millions.

“Remember in ‘Love Warrior’ how hard I struggled to understand what being in love meant?” she writes. “I get it now. I get it. I am in love. And I’m really, deeply happy.”

She answers a few of the questions she assumes will pop up. (“Isn’t this fast?” “How are the kids?” “How is Craig?”) And she acknowledges that some people might be left wondering how to feel.

“My loves, here is the good news,” she writes. “You are allowed to think and feel WHATEVER YOU NEED OR WANT TO FEEL! … That is what I want to model now, because that is what I want for YOU: I want you to grow so comfortable in your own being, your own skin, your own knowing that you become more interested in your own joy and freedom and integrity than in what others think about you. That you remember that you only live once, that this is not a dress rehearsal and so you must BE who you are.”

You are allowed to think and feel WHATEVER YOU NEED OR WANT TO FEEL! What theological codswallop. And yet, this kind of thing is celebrated by a lot of younger Evangelicals. Not even an attempt to base this in theological convictions; only self-worship.

Is this a female thing, this approach to mass Christianity, or is it general to our Christian pop culture today? Asking seriously.

All Is Right With The World

This was the scene this morning at Tiger Deauxnuts in Baton Rouge. Really, how bad can things be in the world when there are donuts?

Rod Dreher's Blog

- Rod Dreher's profile

- 503 followers