Rod Dreher's Blog, page 513

November 23, 2016

A Weber Thanksgiving

Hey, I’ve been meaning to post today, but have been sick in bed most of the day with something digestive that threatens turkey consumption on the morrow. In the meantime, I want to encourage you home cooks with this short episode of an amateur chef at Weber State University in Ogden, Utah, teaching fellow students how to prepare an American classic. Background here. Perhaps this delicacy will find its way to your Thanksgiving table.

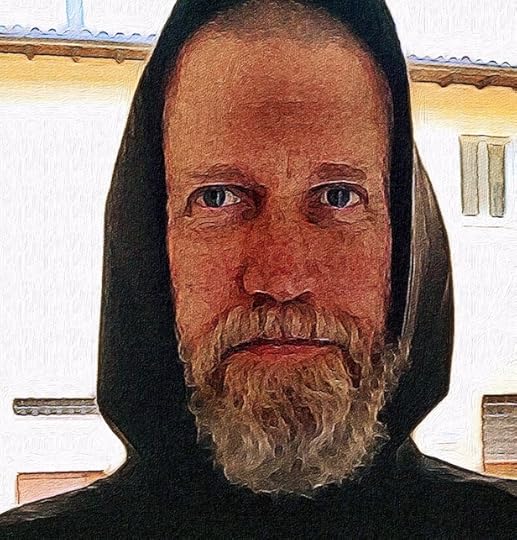

Father Cassian Steps Down

Father Cassian Folsom, February 2016 (Photo illustration by Rod Dreher)

Shocking news from Norcia this morning, in this letter Father Cassian sent out to the monks’ supporters worldwide:

In the history of every new community, the transition from the founder to the next generation of leadership is a positive sign of growth and maturity. I am happy to announce that the monastic community of Norcia has reached this important moment.

The earthquakes of the past several months have presented us with incredible challenges, which require vigorous, creative leadership. While I am in good health at the moment, I do not have the strength or energy necessary to meet these challenges. Therefore it is time to pass the baton to younger, more energetic hands. After consulting the chapter members of the monastery, I submitted my resignation to the Abbot Primate, the Most. Rev. Gregory Polan, O.S.B., who appointed Fr. Benedict Nivakoff, O.S.B., to take my place.

Fr. Benedict is extremely well-qualified to lead the community. He has much experience as Subprior and Novice Master, and possesses the human and spiritual qualities necessary to guide the monastery in these difficult times. As for me, after eighteen years of intense labor, I am ready to accept a less demanding assignment, and will continue to serve the community in whatever way I can, especially as a liaison with our many friends and benefactors.

When St. Paul talks about the transition of leadership in the church of Corinth, he writes: “I planted, Apollos watered, but God gave the growth” (1 Cor 3:6). We give thanks for the life of our community: for the planting, for the watering and for the growth that comes from God.

Fr. Cassian Folsom, O.S.B.

November 22, 2016

Father Benedict, the new prior, adds:

In 18 years, a new life is conceived, cared for in the womb, coddled in the crib, accompanied on first steps, then school, and at last graduates from high school before moving on to college or the workforce. For our founder, Fr. Cassian,

Fr Benedict Nivakoff, the new prior of Norcia

these last 18 years have meant all that labor multiplied many times over. His indefatigable work to re-found traditional monastic life in Norcia gave to the Church signs of life for which his monks and Catholics worldwide are profoundly grateful.

Now Fr. Cassian is giving another gift, and we hope not the last. In resigning and passing the custody of our monastic community to another, he is offering to accompany us as we continue to grow. Though he is retiring and will no longer serve as prior, he will continue to be, in an even deeper way, father to the monastery and the town of Norcia.

Following the earthquakes that destroyed our church and monastery, we monks have come to appreciate that the spirit of monastic life Fr. Cassian instilled in our community transcends walls and buildings. As Fr. Cassian once said, the monastery exists as a lighthouse. We exist as a lighthouse so that souls tossed about at sea might traverse the waves of this world and find rest in the harbor of God. But before we monks can summon others to shore, we must ourselves draw close to the light that is Christ. It is our vocation, our duty and delight to be always seeking Him. It is my honor and joy now to lead my brothers in our search for God, through His Son, Jesus Christ our Lord. For this I and my brother monks ask your continued prayers.

Fr. Benedict

Prior

This is news both sad — for Father Cassian — and joyful, for Father Benedict. If you’re the sort of person who prays, please give them both your prayers. What a year this has been for the monks and the people of Norcia. I am convinced that in the decades to come, Father Cassian will be celebrated as one of the true heroes of the Church in his time, a man who laid the groundwork for the restoration. Watch:

November 22, 2016

Blind Leading The Blind

The Guardian, the voice of the left-wing British establishment, has published a media guide for readers who would like to understand American conservatism while minimizing their contact with actual conservatives. The writer is Jason Wilson, an Australian who lives in Portland, Oregon, so you know he’s really in touch with the big, hot-blooded heart of America. Wilson writes:

Herein lies the problem: many of us now live in “filter bubbles” wherein social media algorithms tend to feed us only those perspectives that we already agree with. Let’s assume, then, that all of us, including progressives, do need to broaden our horizons, and seek out more views that differ from ours.

One of the conservative political magazines he recommends is Reason. Now, Reason is a great magazine, a magazine people should read. But it’s a libertarian magazine.

The Guardian also recommends TAC, for which I am grateful, I suppose. But look:

Once again, this comes with mile-high health warnings. The American Conservative was co-founded in 2002 by that proto-Trump Pat Buchanan, who ran for president three times on a “paleo-conservative”, isolationist, anti-migration platform. It plays host to arch-reactionaries such as Rod Dreher, who spends a lot of time worrying in print about who uses which bathroom.

But because it was founded in opposition to neoconservatives and the war they started in Iraq, it has long offered space to unique, and principled, anti-war voices (including some on the left).

For example, few have done more than Kelly Vlahos to track the growth of the national security state, and the class that it enriches.

And although many paleocons (including Buchanan) supported Trump, as he begins to surround himself with neoconservative advisers, expect incisive conservative critics of Imperial America like Andrew Bacevich to step up.

I can hardly express how delighted it makes me to have been branded an “arch-reactionary” by The Guardian … except for the fact that it’s like being called a racist by the Southern Poverty Law Center. If all it takes to be an arch-reactionary in the eyes of The Guardian is to be against penis-persons using the women’s bathroom, then the United States is so riddled with Yankee Doodle de Maistres that if Trump doesn’t work out, we’ll install the Bourbon monarchy. Anyway, I’ll happily take the compliment, but I must say that only a furriner who lives in the People’s Republic of Portlandia could mistake Your Working Boy for an arch-reactionary.

It is certainly true that TAC’s conservatism is more sympathetic to Trumpism than is the conservatism of National Review or The Weekly Standard, though it should be pointed out that both Daniel Larison and I were not Trump supporters during the campaign (but editor-in-chief Dan McCarthy was, in his private capacity). You can get a much better idea of what drives Trump-friendly conservatism by reading this site than our competitors. Still, what’s interesting is that Comrade Wilson only wants his readers to pay attention to right-of-center media sources insofar as those media sources confirm what they already believe.

Here’s the funniest thing of all from Wilson’s piece:

Faith-based publications offer another source of thoughtful political journalism, even if it’s not always based on principles that progressives can agree with.

America Magazine, published by the Catholic Jesuit order, has already begun reporting on moves to resist immigration raids, and regularly features opinion contrasting the teachings of Pope Francis with the shibboleths of American conservatism.

Understand: The Guardian advises its readers who want to get inside the heads of American religious conservatives to read America, a generally liberal magazine published by a liberal religious order. There are lots of reasons to read America, I suppose, but getting an idea of what religious conservatives think is not one of them.

Then again, Wilson suggests that Guardianistas read Tikkun, the very left-of-center Jewish magazine, and consult the website of the Uniting Church, which has been “as unstinting in their criticism of Trump as any progressive website.”

Um, I don’t know quite how to tell Jason Wilson and his editors, but the Uniting Church does not exist in the United States. It is an Australian institution. Jason Wilson knows so little about American religion that he assumed a church from his native country has an American branch.

It looks like Jason Wilson assumes that all religious people are some form of conservative — and nobody in The Guardian‘s editorial chain of command knew enough about religion to counter him.

What was that Wilson was saying about living in “filter bubbles”?

What To Make Of Steve Bannon?

Since Trump elevated Steve Bannon to be his Karl Rove, several of you have pressed me to say what I think of him. It has been framed as, “Now that Trump will be bringing such a berserk bigot into the White House, you are obliged to denounce them all. What’s taking you so long?”

I’ll tell you what was taking so long: I genuinely can’t get a handle on Bannon. As I started reading up on him, I realized that I had absorbed the narrative that he is a complete and total villain. But something about the stories and opinion pieces I was reading about him didn’t quite fit. I couldn’t put my finger on it. Then I read the transcript of a 2014 speech he gave at a Vatican conference, and it set me back. Excerpts:

It’s ironic, I think, that we’re talking today at exactly, tomorrow, 100 years ago, at the exact moment we’re talking, the assassination took place in Sarajevo of Archduke Franz Ferdinand that led to the end of the Victorian era and the beginning of the bloodiest century in mankind’s history. Just to put it in perspective, with the assassination that took place 100 years ago tomorrow in Sarajevo, the world was at total peace. There was trade, there was globalization, there was technological transfer, the High Church of England and the Catholic Church and the Christian faith was predominant throughout Europe of practicing Christians. Seven weeks later, I think there were 5 million men in uniform and within 30 days there were over a million casualties.

That war triggered a century of barbaric — unparalleled in mankind’s history — virtually 180 to 200 million people were killed in the 20th century, and I believe that, you know, hundreds of years from now when they look back, we’re children of that: We’re children of that barbarity. This will be looked at almost as a new Dark Age.

But the thing that got us out of it, the organizing principle that met this, was not just the heroism of our people — whether it was French resistance fighters, whether it was the Polish resistance fighters, or it’s the young men from Kansas City or the Midwest who stormed the beaches of Normandy, commandos in England that fought with the Royal Air Force, that fought this great war, really the Judeo-Christian West versus atheists, right? The underlying principle is an enlightened form of capitalism, that capitalism really gave us the wherewithal. It kind of organized and built the materials needed to support, whether it’s the Soviet Union, England, the United States, and eventually to take back continental Europe and to beat back a barbaric empire in the Far East.

That capitalism really generated tremendous wealth. And that wealth was really distributed among a middle class, a rising middle class, people who come from really working-class environments and created what we really call a Pax Americana. It was many, many years and decades of peace. And I believe we’ve come partly offtrack in the years since the fall of the Soviet Union and we’re starting now in the 21st century, which I believe, strongly, is a crisis both of our church, a crisis of our faith, a crisis of the West, a crisis of capitalism.

And we’re at the very beginning stages of a very brutal and bloody conflict, of which if the people in this room, the people in the church, do not bind together and really form what I feel is an aspect of the church militant, to really be able to not just stand with our beliefs, but to fight for our beliefs against this new barbarity that’s starting, that will completely eradicate everything that we’ve been bequeathed over the last 2,000, 2,500 years.

Yes, right! A guy with this kind of insight is the white supremacist ogre moving into a White House office? Really? More, from the Q&A:

Benjamin Harnwell, Human Dignity Institute: Thank you, Steve. That was a fascinating, fascinating overview. I am particularly struck by your argument, then, that in fact, capitalism would spread around the world based on the Judeo-Christian foundation is, in fact, something that can create peace through peoples rather than antagonism, which is often a point not sufficiently appreciated. Before I turn behind me to take a question —

Bannon: One thing I want to make sure of, if you look at the leaders of capitalism at that time, when capitalism was I believe at its highest flower and spreading its benefits to most of mankind, almost all of those capitalists were strong believers in the Judeo-Christian West. They were either active participants in the Jewish faith, they were active participants in the Christians’ faith, and they took their beliefs, and the underpinnings of their beliefs was manifested in the work they did. And I think that’s incredibly important and something that would really become unmoored. I can see this on Wall Street today — I can see this with the securitization of everything is that, everything is looked at as a securitization opportunity. People are looked at as commodities. I don’t believe that our forefathers had that same belief.

This is the anti-Semite troll I’ve been told so much about? Again: really? Bannon, a veteran of Goldman Sachs, spends a big part of the Q&A period criticizing crony capitalism, in particular conservative politicians who support it. Excerpt:

In fact, one of the committees in Congress said to the Justice Department 35 executives, I believe, that they should have criminal indictments against — not one of those has ever been followed up on. Because even with the Democrats, right, in power, there’s a sense between the law firms, and the accounting firms, and the investment banks, and their stooges on Capitol Hill, they looked the other way.

So you can understand why middle class people having a tough go of it making $50 or $60 thousand a year and see their taxes go up, and they see that their taxes are going to pay for government sponsored bailouts, what you’ve created is really a free option. You say to this investment banking, create a free option for bad behavior. In otherwise all the upside goes to the hedge funds and the investment bank, and to the crony capitalist with stock increases and bonus increases. And their downside is limited, because middle class people are going to come and bail them out with tax dollars.

Read the whole thing. Note well that Bannon gave this speech, and answered questions about it (also in the transcript), in 2014. I agree with a lot of what he says here, though I fear that his belief that the racists and anti-Semites of the Alt-Right will “all burn away over time and you’ll see more of a mainstream center-right populist movement” — I fear that that is too naive. If Bannon and Trump really believe that these people are fringey creeps that they don’t want in their movement, then they need to clearly and forcefully distance themselves from that crowd. They can’t play footsie with them, cultivating them when it’s politically useful, then claiming they have nothing to do with them.

Okay. Then I read Michael Wolff’s interview with Bannon last week. Excerpts:

In these dark days for Democrats, Bannon has become the blackest hole.

“Darkness is good,” says Bannon, who amid the suits surrounding him at Trump Tower, looks like a graduate student in his T-shirt, open button-down and tatty blue blazer — albeit a 62-year-old graduate student. “Dick Cheney. Darth Vader. Satan. That’s power. It only helps us when they” — I believe by “they” he means liberals and the media, already promoting calls for his ouster — “get it wrong. When they’re blind to who we are and what we’re doing.”

Whoa! When I first read that, my jaw dropped. Then I realized that context is everything here. Bannon seems to be speaking in a joking manner, saying that the fear Team Trump’s enemies have of them blinds them (the enemies) to what Team Trump is up to. More:

It’s the Bannon theme, the myopia of the media — that it tells only the story that confirms its own view, that in the end it was incapable of seeing an alternative outcome and of making a true risk assessment of the political variables — reaffirming the Hillary Clinton camp’s own political myopia. This defines the parallel realities in which liberals, in their view of themselves, represent a morally superior character and Bannon — immortalized on Twitter as a white nationalist, racist, anti-Semite thug — the ultimate depravity of Trumpism.

So: is Bannon trolling the media, and the rest of us? More:

Bannon, arguably, is one of the people most at the battle line of the great American divide — and one of the people to have most clearly seen it.

He absolutely — mockingly — rejects the idea that this is a racial line. “I’m not a white nationalist, I’m a nationalist. I’m an economic nationalist,” he tells me. “The globalists gutted the American working class and created a middle class in Asia. The issue now is about Americans looking to not get f—ed over. If we deliver” — by “we” he means the Trump White House — “we’ll get 60 percent of the white vote, and 40 percent of the black and Hispanic vote and we’ll govern for 50 years. That’s what the Democrats missed. They were talking to these people with companies with a $9 billion market cap employing nine people. It’s not reality. They lost sight of what the world is about.”

Read the whole thing. I still can’t say I know what Steve Bannon is really all about, but I will say for certain that I do not trust the reporting on him. Take a look at this short piece about the neurological basis of confirmation bias. I think Bannon, intentionally or not, is operating on the borderline between what is and what we would like to believe.

Last night, I received an e-mail from a friend, someone you’ve heard of, someone who is an acute observer of American political culture. The topic of his letter: Steve Bannon. He started his e-mail with:

Do you ever feel like the liberal freakout makes it hard for you to actually form an opinion?

I have spent too long trying to figure this out. Like: what do I actually feel?

The answer is, I think, that I think he’s not a racist and has no interest in white nationalism. But that he also has a remarkable faith that the ethnic nationalist side of the alt-right will just go away with time. That’s led him to tolerate and even cultivate relationships with certain parts of the alt-right, and some of them have been remarkably ugly people whose views could cause a lot of damage if allowed to spread.

I can’t tell you what a relief it was to read that an actual famous smart guy had the same sense that I did about Bannon: that he has some pretty nasty associations that he doesn’t take seriously enough, but that the liberal media reporting on him is not trustworthy. I thought I was being irresponsible or dense by not being able to get a handle on Bannon. Maybe I am. Maybe we both are. But I don’t think so.

This is not a satisfying conclusion for you, I admit. It is not a satisfying conclusion for me. But it’s what I have now.

UPDATE: In this context, let me lend my emphatic support to what Yuval Levin wrote in the wake of Trump’s victory, especially this:

In a similar spirit, and even more important, we should also recognize that for many Americans, regardless of their politics, this turn of events cannot help but be somewhat frightening. They have been witness in recent months not only to talk of Donald Trump’s obvious proclivities to viciousness but also to evidence of the depravity of some—a few, to be sure, but some—among his supporters. I have myself experienced a torrent of anti-Semitism that I had pleasantly imagined might not exist in America, and others have experienced and witnessed far worse.

To acknowledge that some among our fellow citizens have this concern is not to say that Trump’s support is rooted in racism, which it is not. It is not to say that his concerns about immigration are fundamentally xenophobic, which they are not. It is only to say that as good neighbors and good citizens we ought to be sensitive to the fears and concerns of those with whom we share this wonderful country. We must see that their worries, even if ultimately not well founded in the reality of the election, are nonetheless rooted in some realities of American life that have been both made clearer and exacerbated by this election season. And it is incumbent upon us on the Right, perhaps especially among those who championed Trump but also among those who didn’t, to offer some respectful, even loving, reassurance. It is above all incumbent upon Trump himself to offer reassurance that such worries, experienced by some as genuinely existential worries, are unfounded with regard to him, and to be clear that whatever his past he will not govern as a bully. His remarks last night certainly gestured toward such reassurance, which was very good to see.

Meanwhile, these tweets from a NYTimes reporter who interviewed Trump today:

Trump on alt-right supporters: "It's not a group I want to energize. And if they are energized I want to look into it and find out why."

— Maggie Haberman (@maggieNYT) November 22, 2016

On Bannon:"If I thought he was a racist or alt-right or any of the things, the terms we could use, I wouldn't even think about hiring him."

— Maggie Haberman (@maggieNYT) November 22, 2016

Trump on Bannon: "I think it's very hard on him. I think he's having a hard time with it. Because it's not him."

— Maggie Haberman (@maggieNYT) November 22, 2016

Failsons Of Weimar America

Yesterday I posted something about the parallels between Weimar Germany and contemporary America. In it, I quoted this from a profile of the Chapo Trap House guys, leftie podcasters in Brooklyn:

At the Genius office, as people set up chairs on the floor below us, Menaker described the generic Chapo fan as a “failson”—which Biederman, who is twenty-six, defined as the guy that “goes downstairs at Thanksgiving, briefly mumbles, ‘Hi,’ everyone asks him how community college is going, he mumbles something about a 2.0 average, goes back upstairs with a loaf of bread and some peanut butter, and gets back to gaming and masturbating.” As for the women fans—who make up maybe twenty to thirty per cent of the audience, they guessed—“they all seem to be success-daughters,” Menaker said. “They’re astrophysicists or novelists, extremely on-point and competent people.”

Christman saw a political lesson in the show’s fan base. “The twenty-first century is basically defined by nonessential human beings, who do not fit into the market as consumers or producers or as laborers,” he said. “That manifests itself differently in different classes and geographic areas. For white, middle-class, male, useless people—who have just enough family context to not be crushed by poverty—they become failsons.” The “Chapo Trap House” guys are sincerely concerned with American inequality; at the same time, their most instinctive sympathies seem to fall with people whose worst-case scenario is a feeling of purposelessness. “Some of them turn into Nazis,” Christman continued. “Others become aware of the consequences of capitalism.”

A reader, a 27 year old reader who is an Orthodox Christian, responded in an e-mail, which I reproduce with his permission:

Your ‘Weimar Germany, Weimar America’ put to words what I’ve been thinking for some time now. Seeing how strikingly similar our situations were/are, I think we are headed for serious trouble. I say this as a 27 year old who looks around and sees many of my peers who are failsons. I mean, if gamer culture is any indication of how bad it is…

I didn’t want to comment in the thread—I don’t want to be taken out of context—but I see many commenters dismissing the possibility that we could be headed in a similar direction. As an Orthodox Christian, I think that is absolutely foolish. A huge swath of man-children who are hooked on hardcore porn and violent video games, feel aimless and emasculated by a society that tells them they are worthless, and have been “raised” in a post-Christian, post-family, absentee-father era, etc…are not a neutral force. Not for the Evil One, they aren’t. Their more base instincts of aggression and violence are merely being subdued and distracted in materialistic hedonism, and their higher instinctual desires for manliness and order can easily be hijacked for nefarious purposes by the some Leader. If Donald Trump of all people was able to inspire some failsons to clean up their act, I can only imagine what a charismatic and seemingly disciplined fringe leader could inspire.

I said this to my brother in conversation yesterday: we are a generation with no virtue, no humility, no respect for the sacred or for authority, enslaved to the passions, etc. Such a generation is ripe for being radicalized, were it not for our comfortable distraction in our materialistic hedonism. For the failsons, it’s easier to just keep looking at porn and playing video games. For others, all our SJW outrage is channeled mostly into social media rants and a few actual protests in order to feel morally superior—no one’s actually experiencing injustice, they just think someone else is. But take that all away? Say, with a huge economic meltdown? I’m afraid we will have an entire generation that will be in utter panic and rage, and they will have no residual virtue to fall back on because they were never raised with it to begin with. Hard times will strip a man down to what he’s made of. Men like your father and my grandfather were made of hard-work, self-reliance, and the Christ-haunted Protestant cultures from whence they came. Hard times stripped them down to that.

It will not be so with my generation. When our fancy universities, nice cars, smart-phones, video games, and job prospects are all taken away, what do we have to fall back on? Nothing. No church, no community, no family, no virtues, no work ethic, nothing. Only our rage and our petulance. If people think nothing will come of this, they couldn’t be more wrong. If they think a strongman won’t harness this, they’re wrong. A stupid billionaire megalomaniac buffoon just did a successful test-run on it.

Your Ben-Op book can’t come soon enough. We’re headed for tumultuous times.

The reader said that leftist blogger James Howard Kunstler made the same point more eloquently in this post, following the 2015 school massacre in Oregon. In it, Kunstler said that our is “a nation physically arranged on-the-ground to produce maximum loneliness, arranged economically to produce maximum anxiety, and disposed socially to produce maximum alienation.” He goes on:

What concerns me more than the gun issue per se is the extraordinary violence-saturated, pornified culture of young men driven crazy by failure, loneliness, grievance, and anger. More and more, there are no parameters for the normal expression of masculine behavior in America — for instance, taking pride in doing something well, or becoming a good candidate for marriage. The lower classes have almost no vocational domain for the normal enactments of manhood, and one of the few left is the army, where they are overtly trained to be killers.

Much of what used to be the working class is now an idle class that can only dream of what it means to be a man and they are bombarded with the most sordid pre-packaged media dreams in the form of video games based on homicide, the narcissistic power fantasies of movies, TV, and professional sports, and the frustrating tauntings of free porn. The last thing they’re able to do is form families. All of this operates in conditions where there are no normal models of male authority, especially fathers and bosses, to regulate the impulse control of young men — and teach them to regulate it themselves.

The physical setting of American life composed of a failing suburban sprawl pattern for daily living — the perfect set-up for making community impossible — obliterates the secondary layer of socialization beyond the family. This is life in the strip-mall wilderness of our country, which has gotten to be mostly of where people live. Imagine a society without families and real communities and wave your flag over that.

President Obama and whatever else passes for authority in America these days won’t even talk about that. They don’t have a vocabulary for it. They don’t understand how it works and what it’s doing to the nation. Many of the parts and modules of it make up what’s left of our foundering economy: junk food, pointless and endless motoring, television. We’re not going to do anything about it. The killing and the mayhem will continue through the process of economic collapse that we have entered. And when we reach the destination of all that, probably something medieval or feudal in make-up, it will be possible once again for boys to develop into men instead of monsters.

I watched the entire speech Richard Spencer gave at his recent white supremacist conference, and I thought, “What a beer hall putz!” I think the media are blowing him and his movement entirely out of proportion. As Jamie Weinstein points out (BronyCon is a gathering of adult men who fancy “My Little Pony”):

As I noted to Richard Spencer in my intv today, his conference had 200-300 ppl, BronyCon 2016 had over 7,000. Not sure alt-right thriving

— Jamie Weinstein (@Jamie_Weinstein) November 21, 2016

Still, attention must be paid. In his speech, Spencer said some true and important things. But they are all entwined with false, malicious, and evil things. It is very, very easy to imagine some deracinated, anxious young white man finding in this barbarism a kind of solution to the problems of his life. What else is there? Same with the Nation of Islam and young black men. Same with street gangs. As I’ve said a thousand times here, this is precisely what the campus SJW mentality is calling up, but not even the SJWs are as effective at calling this up as are the atomizing forces in mass culture — as Kunstler and my reader both understand.

The reader adds:

We have to do the Benedict Option. There Is No. Other. Choice. At this point, when people accuse us of withdrawing, I think “Yep. So?”

UPDATE: A reader who is a pastor writes:

I was raised in a ‘Benedict Option’ home, though my parents would have not understood the phrase. We were taught, prayed for, and guided and encouraged to live in pursuit of God. My mother said that her goal was to keep us out of sin, as much as it lay within her powers to do so. I was a lousy parent in many ways, but the one thing I did was to see that my children were given heavy doses of Scripture when they were young. My daughter lapped it up, and has as much, if not more general Bible knowledge than some seminary graduates.

My son lives an openly atheistic life, and rejects every tenet of Christianity. He is barely employed, and has done a great deal of experimenting with drugs and heavy drinking. Do I feel a failure? Does anyone need to ask? How often does the question arise, “Where did I go wrong?” Even if I had a clear, definitive answer, it would provide no consolation. I pray, sincerely, that you will never have to go through what I have gone through. I have seen better parents than me raise children who dropped out or came out.

The problem with the Benedict Option is in part that many people, even professing Christians, are not interested in it. As a minister, I struggle to preach (for example) on marriage when I have not just divorced people, but couples my congregation who have shared spouses through multiple marriages. (They all get along famously now, even though I think adultery was involved at one point; I can’t absolutely prove it, but I think it. So Heather does have two mommies and two daddies and it’s all very cozy).

Most Christians today, the ones I know anyway, are pretty apathetic about the culture wars, simply wanting to raise ‘nice’ kids who play every sport, manage to marry and get a job and/or attend college, and repeat the cycle in the next generation; or they cling to voting Republican. My family was very concerned about protecting kids from the world. This was expressed in ways that seem anachronistic, quaint and legalistic to most people today. Perhaps so, but the motive was pure, because the world was falling apart (isn’t it always?) and we needed to save our children.

I look forward to your book (I have pre-ordered it) and think it is sorely needed. But I do wonder……

I think it is very, very important for both supporters and critics of the Benedict Option to understand that it is not, and must not be, about beating up people who have failed, or who have experienced failure. It has to be tough love, indeed, tough self-love — asceticism is central to it — but it has to be lived as merciful, in the sense of trying to give people what they (what we) need to live whole lives despite the radical brokenness in the world around us, and within ourselves. And we have to accept the finitude of any human effort. The Benedict Option will never be a failsafe option, because it cannot be. To expect too much from it is to set oneself up for bitterness and disillusionment.

Zadie Smith & ‘The Church At The End Of The Road’

From Isaac Chotiner’s interview with novelist Zadie Smith:

Given that the world feels so fragmented, have you thought more recently about the famous Forster phrase, “only connect,” which is the epigraph to Howards End, and is, in part, a call for connection between people?

Yeah. It’s so easy just to fall through the gap because there’s the lack of collective experience. I was making my children watch There’s No Business Like Show Business because Nick was out of the house so I could get away with it. It’s a slightly terrible musical from the early ’50s. In the middle of it, one of the characters leaves the family act and becomes a priest. My daughter said, “What is a priest?” I thought, Jesus, when I was 7, is there any way I wouldn’t have known what a priest is? I don’t think so, just because you had a collective culture, the TV, but also our community, the church at the end of my road. You would’ve known.

It’s like wow, that’s a big gap, clearly that’s a quite serious thing not to know at 7 that there has been, in fact, our whole society is founded on a faith that she only has the vaguest idea of. She’d heard of Judaism just about, but that was it. That kind of thing is quite shocking to me. I don’t know. It’s atomized. I have no answer. It’s curious to me to watch it happening in my children. They’re kind of piecing together a world. They can’t even go through the record collection as we did and think, Oh there was the Beatles and there was the Stones and here’s Ella Fitzgerald. They only have this iTunes, which just seems to be a random collection of names and titles. There’s no pictures, no context, no historical moment. It’s so odd.

That’s a pretty common experience for a lot of us, don’t you think? Not knowing what a priest is — well, that’s pretty extraordinary for Americans, but I suppose much less so for someone who lives in downtown Manhattan. Understand that Zadie Smith lives in the imaginative world of the cultural ruling class. I don’t say that as an insult, not at all. I’m saying it as merely a description. It has been said that the people who go to law schools, especially the elite law schools that train senior judges, are among the most secular people in the country — and this is inevitably going to have a profound impact on their jurisprudence. What’s most interesting to me is not that people don’t believe in God, but that in the case of Zadie Smith’s children — and the generation of those in that cultural class — they don’t even know what a priest is.

And they don’t know what they don’t know. How would they?

Smith is onto something enormously important, regarding the loss of collective culture and atomization. “Clearly that’s a quite serious thing,” she says. Absolutely. Absolutely! And get this: Zadie Smith does not appear to be a religious believer, but she is quite cosmopolitan. And she was shocked to discover the culture her children had lost, or had never acquired. This is what happens in liquid modernity when you go with the flow, and do not consciously resist the forces of fragmentation.

I’m not faulting Zadie Smith, necessarily. If Christianity, or the foundations of Western culture and civilization, were important to Zadie Smith, she would have taught her children about them. Thing is, how many of us non-cosmopolitan people, people who consider ourselves religious and cultural conservatives, are just like Zadie Smith, in that we wrongly assume that our children are inheriting basic knowledge of our civilization in the way we did? Don’t be so quick to judge Smith.

I’ve seen the same thing with my kids regarding iTunes that Smith has seen with hers. In the case of my kids, iTunes has opened them up to far more music than I ever had access to growing up. My kids have a far broader and deeper knowledge of music than I did at their age (and much better musical taste), and I’m grateful for that. But like Smith’s kids, they have no common musical culture with other kids. There are worse problems in the world, I suppose, but it’s not nothing to look and see that your kids have no real historical moment into which to embed their cultural experiences.

There is no more church at the end of the road, so to speak. But there has to be. From an interview I did with Laurus novelist Evgeny Vodolazkin last year:

RD: I think one of the most important moments in Laurus occurs when an elder tells Arseny, who is on pilgrimage, to consider the meaning of his travels. The elder advises: “I am not saying wandering is useless: there is a point to it. Do not become like your beloved Alexander [the Great], who had a journey but no goal. And do not be enamored of excessive horizontal motion.” What does this say to the modern reader?

That it is time to think about the destination, and not about the journey. If the way leads nowhere, it is meaningless. During the perestroika period, we had a great film, Repentance, by the Georgian director Tengiz Abuladze . It’s a movie about the destruction wrought by the Soviet past. The last scene of the film shows a woman baking a cake at the window. An old woman passing on the street stops and asks if this way leads to the church. The woman in the house says no, this road does not lead to the church. And the old woman replies, “What good is a road if it doesn’t lead to a church?”

So a road as such is nothing. It is really the endless way of Alexander the Great, whose great conquests were aimless. I thought about mankind as a little curious beetle that I once saw on the big road from Berlin to Munich. This beetle was marching along the highway, and it seemed to him that he knows everything about this way. But if he would ask the main questions, “Where does this road begin, and where does it go?”, he can’t answer. He knew neither what is Berlin, nor Munich. This is how we are today.

Technical and scientific revelation brought us the belief that all questions are possible to solve, but that is a great illusion. Technology has not solved the problem of death, and it will never solve this problem . The revelation that mankind saw conjured the illusion that everything is clear and known to us. Medieval people, 100 percent of them believed in God – were they really so stupid in comparison to us? Was the difference between their knowledge and our knowledge as different as we think? It was not so! I’m sure that in a certain sense, our knowledge will be a kind of mythology for future generations. I reflected this mythology with humor in Laurus, but this humor was not against medieval people. Maybe it was self-irony.

November 21, 2016

The Facebook Sessions

US Senator and Attorney General-Designate Jeff Sessions (Rob Crandall/Shutterstock)

A personal friend and reader of this blog writes:

This entire election cycle I have refrained from posting, sharing, or commenting on anything on social media. The atmosphere has been so charged and there has been such hatred and vitriol spewed that I chose to sit it all out. I’ve been largely silent but I’ve read and observed messages from both sides and have been amazed and often amused at the way people from opposite sides combat each other. I’ve had to wonder what they hope to accomplish. Change someone’s opinion? Pull them over to your side? I suppose for those people who thrive on conflict, this has been the perfect petri dish to grow anger and dissension. We see it on social media, we see it playing out on the streets, in the theatre, in our workplaces, and even in our own families.

I shared a post on my own Facebook page about Sen. Jeff Sessions, who I know personally and with whose family I have been friends for nearly twenty years. This was one of the few articles or posts I have seen going around Facebook that represents an accurate picture of the man I know – the man who is being so inaccurately and unfairly judged and portrayed by much of the media and by many people who know nothing about him. For those of us who do know him, we can say without reservation that he is a man of great integrity, compassion, and kindness. He is a good man. He will uphold the rule of law and treat all people with fairness and equality. We are happy about his nomination and we are entitled to feel that way and to defend him with the truth we know, are we not?

Maybe not, because someone whose political views are the polar opposite of mine made a derogatory comment on my post about Sen. Sessions and I simply responded by pointing out that the only purpose in making such a comment was to stir up conflict, something that I’ve had enough respect and consideration not to do on her posts and I would appreciate the same courtesy. After all, this was my page, my post, about someone I know, about something I know to be true. She then unfriended me because, according to her, we can’t be Facebook friends when I would “attack” her as I did.

This Facebook stuff just all seems so petty (which it is), and I couldn’t care less about being “unfriended”, but I find it interesting because it’s really a part of the greater picture of what is going on in our country right now. With so many critical issues facing us….healthcare, ISIS, Russia, unemployment… the hill that so many are choosing to die on right now is a molehill — the molehill of “believe like I believe or you’re a ______ (bigot, racist, etc.)”. The left has built its entire platform on tolerance and acceptance of all, yet there are so many who don’t adhere to those principles when you don’t agree with them. Most can only respond with labels, not logic. I find it incredulous that it’s being applauded that designers are refusing to dress the new First Lady because her husband’s values are incompatible with their own (this makes them principled), yet a bakery or florist cannot refuse to provide a cake or flowers because a wedding offends their values and beliefs (this makes them bigoted). One is right and the other is wrong, yet they are both the same. Is this not a double standard any way you slice it?

Anyone who leans right is accused of being intolerant and unaccepting. I’ve never “unfriended” anyone in real life or on Facebook because they don’t agree with me. I may not agree with you, but I will not disrespect you for expressing something you know and believe to be true, even if I believe otherwise. I daresay anyone has ever effected real change over anything posted on social media. If the left (or the right) is hoping to pull anyone over to their side by behaving badly, it’s failing. I’m not seeing much tolerance, compassion, kindness, or respect out of many who tout themselves as such. In fact, I actually heard from someone who (reluctantly) voted for Trump tell me that the way the left is acting is making him glad now that he did. Interesting.

Cultivating The Benedict Option

Here are text and photos by our friend James C., who is now living and working in Italy. It’s from an e-mail he sent me. I publish it, and the photos he embedded within it, here with his permission.

You bring out more disturbing confirmation that we are falling into a dark age of ignorance (despite the sea of available information). A frightening future is being prepared for us. How much are we willing to sacrifice to keep a grip on our faith, whole and entire, in times of searing trial? I’ve been thinking about that question lately on my journeys in southern Italy. Right now I’m in Otranto in Puglia. An ancient warren of white-stone streets on the deep blue sea. Exploring the maze this evening, I came across this and thought to myself, “It’s Greek to me”:

And of course it was! It’s a church built in the 9th century under the auspices of the See of Constantinople. Inside it’s covered in Byzantine frescoes. Astonishing.

There’s a more famous church in Otranto, the cathedral. Inside is an incredible 12th-century mosaic floor as well as the skeletons of the 800 martyrs who were beheaded when they refused to convert to Islam after the Turks took the city in 1480. To be able to pray before all those sacred bones, glorified by their common and total witness to Christ, well, there are no words:

Are we prepared to do the same, together?

Over the All Saints holiday, I was in the remote mountains of the Pollino in Calabria. Nestled in these mountains are a remarkable collection of Italo-Albanian villages. These were settled as refuges centuries ago by Albanians who fled there, determined to hold onto their faith in exile rather than submit to the Turkish armies overrunning their homeland. I say they are remarkable because they have maintained a particularity of distinct cultural characteristics despite centuries of exile and pressure to be absorbed into the surrounding milieu—language, food, and even the Byzantine church. I stayed at the home of one of these families, and I slept soundly under a large icon of Christ Pantokrator. The family’s children are friends with the bearded parish priest’s own kids. The Italo-Albanian Divine Liturgy was certainly a welcome respite from the standard Novus Ordo. And I got to see the whole town come out to the church to see off one of their own in a solemn and spirited funeral procession.

The town:

It was a wonderful experience, magnificent food included:

My couple of days in that mountain region got me thinking about one critical element of the Benedict Option: If we wish to maintain the faith we must cultivate it. We must foster a shared, distinct and stable culture that supports that faith and is supported by it. In a cultural vacuum or a cultural maelstrom, it cannot easily take root. The faith must be tilled together in good, solid earth.

Weimar Germany, Weimar America

Back in early 2003, I was walking with a New York friend through an exhibit of Weimar-era German paintings at the Neue Galerie on the Upper East Side. After a while, she said, “You can almost hear the trains to Auschwitz coming in the distance.” Her point was that the despair and restlessness captured by those beautiful, disturbing paintings telegraphed the coming cataclysm.

The reporting over the weekend about the white nationalist neo-Nazi confab in DC made me think, naturally, of the Weimar Republic. I sometimes use the term “Weimar America” to describe our country today. Some readers don’t get what I mean by that. Let me explain.

The Weimar Republic was the short-lived experiment in German democracy between the great wars of the 20th century. It emerged from Germany’s loss in World War I, and was brought to a crashing end by the Nazi seizure of power in 1933. The Weimar period was marked by political, economic, and social instability, and intense cultural creativity as well as decadence. Weimar was time in which the center did not hold, and extremism took over the imaginations of many Germans, especially the young. When I speak of “Weimar America,” I’m not saying we are exactly like inter-war Germany. Plainly we are not. But parallels there are, and it’s useful studying the Weimar period for clues as to why things are the way they are in our present American moment, and how the fate of post-Weimar Germany might be avoided.

Yesterday I checked out from my local library The Weimar Republic, a short history by the historian of modernity Detlev J.K. Peukert. It’s a very dry scholarly analysis, mostly focused on economic and political facts. A few things stood out to me, though

The story of Weimar Germany is in many ways a story of the pressures faced by its young adults. Even before the Great War, Germany, like every industrialized nation, was struggling to contend with the forces of modernity shaking the foundations of Western life to the core. Had the war never happened, the young would still have found themselves cut off from their roots by modernization, in the sense that the answers the older generations lived by, and offered to them, didn’t make a lot of sense. But the war did happen, and it thoroughly discredited the old order. German youth were left with a gaping spiritual hole in their soul, and nothing with which to fill it.

That is, theirs was a crisis of meaning. The emerging liberal democracy of Weimar Germany could not resolve it. Weimar Germany struggled famously with economic crisis. Youth unemployment was through the roof. Young adults in Germany at the time had grown up in a popular culture that celebrated youth in an extraordinary way. They have been conditioned to think of themselves as special. Now, because of the war and the subsequent economic crisis, as well as the unavoidable ways that modern industrialization was breaking down stable economic order, they were faced with the disillusioning fact that there would not be a place for many of them in the economic order. The “cult of youth” in prewar Germany had filled the young with a sense of entitlement, and of high hopes for their future. Young men and women who had done all the right things as prescribed by German society now found themselves without hope.

There was also in this a crisis of masculinity. Lots of young German men died in the war. Many men who came into adulthood during the Weimar years grew up without fathers. Plus, the rapid liberalization of family and sexual mores, driven in part by nascent feminism and, in Berlin at least, the normalization of homosexuality and transsexualism, left a generation of young men confused about their purpose and identity in the emerging new society. Political extremists of the Left and the Right stepped in to fill the void of meaning, and to give young men who felt they had no power over the direction of their lives a renewed sense of potency, of agency.

The culture war of the 1920s had political ramifications, writes Peukert. The parties of the Right and the Center strongly reacted against modernizing cultural mores, which were popularly associated with Americanization. The parties of the Left considered the resistance to social liberalization to be an intolerable attempt to restrict individual rights and liberties. Neither side was willing to compromise with the other. When they did compromise on legislation, neither side was satisfied, and kept the fight going. The elites ended by being totally discredited in the eyes of many Germans, making way for extremists.

Finally, Peukert concludes that there is no simple reason to explain the rise of Hitler, but one can make the general diagnosis that he came out of Germany’s failure to deal with the crisis of modernization. Peukert says that every other major Western industrialized nation was dealing with the same crisis in that period, but it hit Germany especially hard, because of various historical reasons (the war and its effects, hyperinflation, etc.). In other words, any Western nation could have gone Germany’s route, but other nations had the internal resilience to manage the passage into modernization better than Germany did. One example of how helpless Germans felt, compared to other Western industrial powers: in 1932, the US had 85 suicides per one million inhabitants. Great Britain and France, which had been savaged by the Great War, had, respectively, 133 and 155. And Germany? It had 260 suicides per million.

So, what does this have to do with us?

Ross Douthat wrote a very strong column over the weekend in which he called the present situation a “crisis for liberalism” . Excerpts:

Much of post-1960s liberal politics, by contrast, has been an experiment in cutting Western societies loose from those foundations, set to the tune of John Lennon’s “Imagine.” No heaven or religion, no countries or borders or parochial loyalties of any kind — these are often the values of the center-left and the far left alike, of neoliberals hoping to manage global capitalism and neo-Marxists hoping to transcend it.

Unfortunately the values of “Imagine” are simply not sufficient to the needs of human life. People have a desire for solidarity that cosmopolitanism does not satisfy, immaterial interests that redistribution cannot meet, a yearning for the sacred that secularism cannot answer.

Sound familiar? And this, from Philip Rieff in 1966: “The death of a culture begins when its normative institutions fail to communicate ideals in ways that remain inwardly compelling, first of all to the cultural elites themselves.” Think of German Christianity in the Weimar period. Why had the churches lost their power to speak meaningfully and counterculturally to the young? What happens when a nation’s Christianity doesn’t offer real answers to the crises in the lives of real people, but has turned itself into intellectual abstraction, empty formalism, or feelgood-ism?

More Douthat:

So where religion atrophies, family weakens and patriotism ebbs, other forms of group identity inevitably assert themselves. It is not a coincidence that identity politics are particularly potent on elite college campuses, the most self-consciously post-religious and post-nationalist of institutions; nor is it a coincidence that recent outpourings of campus protest and activism and speech policing and sexual moralizing so often resemble religious revivalism. The contemporary college student lives most fully in the Lennonist utopia that post-’60s liberalism sought to build, and often finds it unconsoling: She wants a sense of belonging, a ground for personal morality, and a higher horizon of justice than either a purely procedural or a strictly material politics supplies.

Thus it may not be enough for today’s liberalism, confronting both a right-wing nationalism and its own internal contradictions, to deal with identity politics’ political weaknesses by becoming more populist and less politically correct. Both of these would be desirable changes, but they would leave many human needs unmet. For those, a deeper vision than mere liberalism is still required — something like “for God and home and country,” as reactionary as that phrase may sound.

It is reactionary, but then it is precisely older, foundational things that today’s liberalism has lost. Until it finds them again, it will face tribalism within its coalition and Trumpism from without, and it will struggle to tame either.

If there’s one thing that Trump has accomplished, it’s the undermining of the political elites of both parties. It has been clear for some time that the GOP elites crumbled before him. This election proved that the Democratic Party elites — the embodiment of which was Hillary Clinton, in ways beyond the mere fact that she was its standard bearer this fall — have also been discredited. If the GOP elites had been sound, Donald Trump would never have gotten anywhere in the primaries. If the Democratic elites had been sound, Hillary Clinton would have beaten Trump to a pulp at the polls.

Again: sound familiar?

Douthat’s column brought to mind this piece from The New Yorker, profiling the self-described “Dirtbag Left” of the Chapo Trap House, an increasingly popular podcast by three Millennial lefties in Brooklyn. Excerpt:

At the Genius office, as people set up chairs on the floor below us, Menaker described the generic Chapo fan as a “failson”—which Biederman, who is twenty-six, defined as the guy that “goes downstairs at Thanksgiving, briefly mumbles, ‘Hi,’ everyone asks him how community college is going, he mumbles something about a 2.0 average, goes back upstairs with a loaf of bread and some peanut butter, and gets back to gaming and masturbating.” As for the women fans—who make up maybe twenty to thirty per cent of the audience, they guessed—“they all seem to be success-daughters,” Menaker said. “They’re astrophysicists or novelists, extremely on-point and competent people.”

Christman saw a political lesson in the show’s fan base. “The twenty-first century is basically defined by nonessential human beings, who do not fit into the market as consumers or producers or as laborers,” he said. “That manifests itself differently in different classes and geographic areas. For white, middle-class, male, useless people—who have just enough family context to not be crushed by poverty—they become failsons.” The “Chapo Trap House” guys are sincerely concerned with American inequality; at the same time, their most instinctive sympathies seem to fall with people whose worst-case scenario is a feeling of purposelessness. “Some of them turn into Nazis,” Christman continued. “Others become aware of the consequences of capitalism.”

Failsons. That’s a chilling neologism. Again: sound familiar? Dylann Roof and his tribe are also failsons, many of them the offspring of faildads and failmoms, though not the comfortable middle-class failsons who subscribe to Chapo Trap House. The white working class failsons are growing into adulthood as part of a class that has shockingly high mortality rates. Their families are falling apart, their moral structures are in collapse, and their economic prospects are diminished. Read your Charles Murray. Read your J.D. Vance.

Read your Weimar history.

Sooner or later, somebody is going to find a way to radicalize those failsons. Some of the middle class failsons will gravitate to the Weimar Brooklyn worldview of the Chapo Trap House. Many other middle class white failsons, I suspect, will gravitate to the intellectualized neo-Nazism of Richard Spencer, highly educated and articulate son of Dallas’s posh Park Cities. The point is: watch the failsons, who are being failed by families, by the church, and by a hedonistic and individualistic society that does not know how to manage this phase of modernity.

The United States is one major economic crisis away from something very, very ugly taking power. It is hard to see what our enervated American institutions — government, academia, families, churches, and the like — can do to stand up against it effectively. Nothing is determined in advance, and, as the late German historian Peukert points out, every Western industrialized nation in the 1920s and 1930s faced the same challenges Germany did. Most of them did not lose themselves to fascism or communism.

Still, we are headed for a tumultuous period of American history, and you’d have to be a fool not to see that, and to prepare. For orthodox Christians, my own tribe, we must hope and pray that we never face a situation like that faced by Martin Niemoller, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, and other German Christians who resisted the Nazi state’s takeover of German churches — a takeover supported by many German Christians, it must be said. The time is now to ask ourselves what it means to be a faithful Christian today, and what kind of personal sacrifices we must be prepared to make to stand in opposition not only to some potential far-right or far-left government, but to the post-Christian, indeed anti-Christian, consumerist, hedonist, rootless culture in which we live. Don’t wait. Prepare. Decadent bourgeois Christianity of the left and the right is not going to survive. Nor will Lennonism.

The Benedict Option In Western PA

Tara Ann Thieke, a reader of this blog, has started a Benedict Option group in Western Pennsylvania. From its Meetup site:

Are you confused, bummed, or conflicted about where your town, culture, and world are headed? Do you feel helpless before endless wars, endless neoliberalism, throw-away attitudes and wanton destruction? Are you frustrated at being cast into a narrow spectrum of labels, or suspect we’ve crippled our ability to see our problems in their larger context? Are you exhausted by constant attacks on the human person, regardless of the color of their skin, their sex, their political beliefs, their economic status, their development, or their health?

Do you wonder if the crises facing us can be meaningfully addressed only by tackling the dehumanizing assumptions implicit in the larger framework of our society? Do you think we can’t face any of our problems without honestly addressing the consumerism, throw-away culture, and hostile attitudes towards true stewardship and the human person? And do you think we may need a guide greater than ourselves in order to meaningfully critique ourselves, perhaps even a rediscovery of orthodoxy?

Then consider the Western Pennsylvania Benedict Option. It’s our wish to open a dialogue about the open ills that plague us, as well as the unspoken ones. Legal defeats or victories come after what’s in the hearts and minds of a people. If we cannot show the fruits of a theology of love, all nuance will be dismissed as cruel. If we cannot ourselves live out the grace of “See how they love one another” then we will win no friends and influence no persons. And if we refuse to understand the magnitude of the problems facing us, hoping we can keep our heads down and avoid confronting the zeitgeist, then we will have given away all we love for the illusion of security.

So come discuss and seek alternatives to the consumerist, community-devouring Leviathan. Gather with us to discuss how to love our neighbor while holding true to a creed; let’s seek to regain perspective free from the constraints of instant gratification and rootlessness. Gather with us to find how to live the Benedict Option, and how to bring the Benedict Option into a world for healing.

Go to the site and join up with them! I met Tara and her husband at the Front Porch Republic conference this fall at Notre Dame. Really good people.

A reader wrote yesterday to say that the situation at her church has become intolerable after the election. She’s conservative, but the congregation is mostly liberal. She reports that her fellow churchgoers have become obsessed with politics, and with politicizing everything there, in an in-your-face, hostile way. She and her husband feel that their days are numbered at that church, though they have been part of the congregation for a long time. She asked me if I was keeping up with local folks interested in the Ben Op in cities and towns around the country.

The answer is no, but my publisher and I are building a website for The Benedict Option book that I intend to make in part a clearing house for local Ben Op initiatives around the country, and even overseas.

Readers, the Benedict Option is going to have to be something we all do together, in our own communities. I am happy to help get the word out. When you hear about an initiative in your area, like the one Tara Ann Thieke has started in western Pennsylvania, please join in and see how you can help. There are already 30 members of the group, and they’ve got a meetup planned in Harmony, PA, on December 10. Click here to learn how you can be a part of the group.

This is really exciting to me. The book will be a success only if it inspires readers all over to take action locally. Go, western PA, go!

UPDATE: Tara has posted a link to her Western Pennsylvania Benedict Option blog.

Rod Dreher's Blog

- Rod Dreher's profile

- 503 followers