Rod Dreher's Blog, page 50

September 27, 2021

Frederick Joseph Is A Racist Bully

I was watching late last night a documentary about the late Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky, who died in 1986. In a recording of his voice after he defected to the West (in the mid-1980s), we hear Tarkovsky saying that the measure of a civilization is its spirituality. In that sense, he says, he has more hope for Russia (then still under Soviet rule) than for the West, given what he has seen. A civilization that is rich but that lacks spirituality is really a zombie civilization, he said.

That line got me to thinking this morning about Americans who have the (false) impression that free speech is under threat in Hungary, but who are completely ignorant of how much less free Americans are than Hungarians to speak their minds. It has nothing to do with laws. It’s about culture.

Here’s what I mean. After the movie, I checked Twitter, and saw how this revolting drama played out.

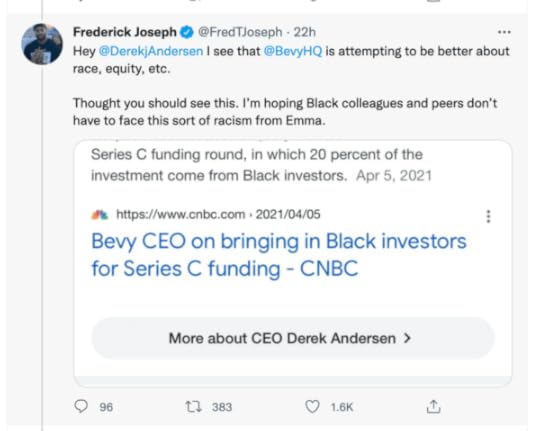

It started with Frederick Joseph, a NYT bestselling author of a book called The Black Friend: On Being A Better White Person. No doubt it was inhaled by the baizuo, who treated it like Holy Writ. Anyway, this is what happened to Joseph over the weekend:

At the dog park in Brooklyn with my fiancé and this white woman was threatening to call police and told us to “stay in our hood” because she had our dog confused with another dog who had been barking loudly. So, I started recording and she tried to slap the phone out my hand. pic.twitter.com/9MXwMiU3Qb

— Frederick Joseph (@FredTJoseph) September 26, 2021

Was this white woman being obnoxious by mistaking Joseph and his fiancée for interlopers, and telling them to go back to their own neighborhood? Yes, she was. If you live in New York City, as I did for five years, you have to develop a thick skin, because there is always somebody being obnoxious to you. This is just life in the big city.

When he saw that the white woman recognized she was being filmed, and got frightened, Fred Joseph realized that he had power over this woman. And armed with his 116,000 Twitter followers (plus his Instagram mob), Fred Joseph decided to use it. After someone on his Instagram feed identified the white woman, he set out publicly to get her fired:

And he succeeded:

Hey presto, Social Justice!

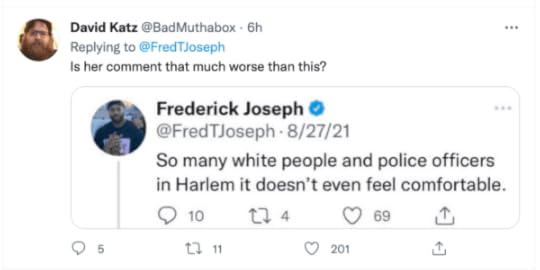

Fred Joseph is a hypocrite, though. Someone on Twitter caught him out saying just last month that white people ought to get out of Harlem:

None of it matters. Fred Joseph can destroy a stranger’s life after a single regrettable remark she made in a brief dog park encounter, and get away with it because of the color of his skin, which makes him a Sacred Victim in the baizuocratic social order that the woke had created [from baizuo, the Mandarin term of contempt for white Western progressives]. And it doesn’t matter that he was very recently guilty of the same hostility to white people that he accuses Emma Sarley of. People like Fred are power-holders in this new world order. The rest of us have to be afraid of the Freds of the world, because all they have to do is think that some non-black person has been racist to them, and BOOM, that person faces an instant Internet campaign to get them fired, and their name ruined forever.

I wonder how amenable Emma Sarley and those who love her will be to appeals to oppose racism now? I wonder how likely they are to regard “anti-racist” campaigns as nothing but power plays.

Stay far away from the Fred Josephs of the world. Nothing good can come from being their friend or associate. And do your best not to work for gutless companies that allow themselves to be manipulated by the Fred Josephs of the world. Unfortunately, I can’t think of a single company that wouldn’t have done what Bevy did. To be denounced publicly as an Employer Of Racists is the worst thing in the corporate world (though nota bene, anybody who employs Fred Joseph has Twitter evidence, from 8/27/21, that he harbors racist anti-white views, but as we now, in the baizuocracy, that redounds to his credit).

is the worst thing in the corporate world (though nota bene, anybody who employs Fred Joseph has Twitter evidence, from 8/27/21, that he harbors racist anti-white views, but as we now, in the baizuocracy, that redounds to his credit).

So, yes, speech is de facto more free in Hungary because so far, it is not a common thing to try to use the Internet and social justice ideology to get people who annoy you fired and destroy their lives. I think Fred Joseph is an anti-white racist, but I would never try to get him fired for his views, as long as he was not in a position to hurt people with them (and speech is not violence). Even racists like Fred Joseph have a moral right to earn a living. As ugly as his rhetoric is, I would rather live in a society that tolerates it, and doesn’t try to destroy him personally and professionally, than to live in the persecutorial society that the woke are creating. They are making America worse in every way. You can be quite sure that many non-black people are observing this situation, and quietly deciding to be very, very careful interacting with black people, because one slip of the tongue could change your life for the worst.

This is not the kind of America that decent people of any and all races want. Being a liberal democracy means that we have to put up with things we don’t like, and especially things we don’t like to hear. A couple of years ago, I was in a position in which I was being mistreated by a local businessman (white, though race had nothing to do with it), who was a landlord of a rental property in my neighborhood. He had some bad renters in who often caused the police to be called because of violent threats one of the residents made publicly against his housemate (screaming, high or insane, on the street). When the landlord kept blowing me off, I realized that given my Internet platform, both on this blog and on social media, I could bring a lot of pain to this man in his business. I probably couldn’t ruin his business, but I could damage him, and damage his professional standing in the community. There was absolutely no question that this man was in the wrong, and was behaving very badly. Yet I decided in the end not to do it, because there is no way to control information like that when it goes online, and it was very easy to imagine how the punishment could end up wildly disproportionate to the “crime”.

I made a similar move a few years back when a man at a local pizza delivery joint screwed up my order, and covered up for himself by flat-out lying about me to his manager. Angry, I posted something to social media about it from my car, but when someone from that chain’s corporate office followed up with me, I declined to file a formal complaint. Though I had been wronged, I did not want to be responsible for punching down on a lowly pizza slinger, and cost him his job. It was easier to live with no pizza and a false accusation made in front of his manager than it would be to live with the knowledge that a complaint from a relatively high-profile customer cost a young man his job.

I don’t say that to hold myself out as a competitor for the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award. I think the way I behaved in both cases was the kind of thing that has to be done to maintain a civil society. Sometimes you just have to suck it up, because the cost of settling accounts is too great. Our baizuocratic Republic now has countless freelance agents for the woke Committee For The Promotion Of Virtue And The Prevention Of Vice roaming the streets, looking for reasons to punish those they hate.

See, this is what I mean in Live Not By Lies when I talk about how we have all the outward structures of liberal democracy, but it has decayed within into something shaping up to be totalitarian. Of course we have a First Amendment — but how much good was the First Amendment to Emma Sarley? See what I mean? The fact is, people like Fred Joseph, and their allies within institutions who live by the Fred Joseph standards, have no interest in defending liberal democratic norms. What good are those norms when people who belong to a particularly favored class can act with impunity to run the lives of those who are in a disfavored class?

And look, don’t come at me with “well, that will teach racists to think twice before they tell black folks to go back to their hood.” I’m not defending what Emma Sarley said to that couple any more than I would defend Fred Joseph’s tweeting out that white people ought to leave Harlem. What I’m defending is the right to express a mildly obnoxious and offensive opinion without being mobbed by the Internet and having your career destroyed. Fred Joseph benefits from the illiberal hypocrisy the US ruling class has, which tolerates all manner of racist speech from non-whites.

That said, anybody non-woke person who goes near Frederick Joseph after this is a fool. He has shown what a little tyrant he is. You know, though, the problem is not really Fred Joseph. The problem is Bevy.com and companies like it who bow and scrape to these tyrants. The problem is institutions that have elevated these tyrants, and given them the power to do this to other people. I just looked Emma Sarley up online. Do you know you can get her address and phone number online? I can tell you where she is not right now: at that address. Why not? Because she has almost certainly been dealing with death threats. This happened to me in New York back in 2001, when mildly obnoxious words in my New York Post column earned me the ire of the Sharpton Outrage-Industrial Complex. I literally had to hide out in my apartment (in those days, it was a lot harder to find addresses online) because I had black people leaving messages on my work phone threatening to cut my throat. I watched a live shot on local cable TV as a young black man told a large and very angry black audience that he had gotten me on the phone, and I had unleashed a torrent of racist invective against him. The crowd went wild, though every word of what this man said was a lie. A minute later, the mob was chanting “Kill Giuliani!”

I watched this on TV, and wondered how I would ever be able to work in New York again, or even walk down the street without having to fear being assaulted. Then, a week later, 9/11 happened, and people had more important things to think about.

All I’m saying is that racist bullies like Fred Joseph are a menace to liberal democracy — and so are people like Bevy.com CEO Derek J. Anderson and the management team at his woke capitalist firm. These baizuocrats have created an unjust and dangerous system, and should not be surprised if rising numbers of people reject it. I am sure that there are a lot of people who don’t really like Donald Trump, but who would vote for him as a way to kick woke tyrants like Frederick Joseph and Derek J. Anderson in the teeth. I’ll leave the last word to Wilfred Reilly, an African-American commentator who is a great follow on Twitter:

In urban up-middle class life, any Black person/POC has at least a 50+% chance of getting any white person fired by simply saying: “He called me (X slur).”

I doubt this power is only used for good.

— Wilfred Reilly (@wil_da_beast630) September 27, 2021

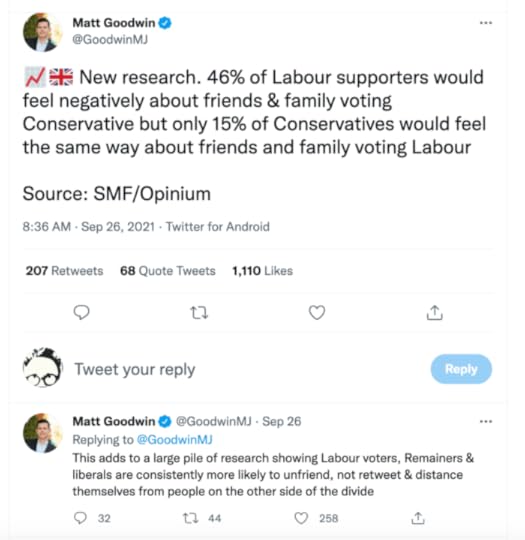

UPDATE: Research from the UK:

Surprise, surprise. It’s not the Right that’s ruining Western liberal democracy.

UPDATE.2: Here’s another story I encountered over the weekend about black racist crybullies steamrolling liberal democratic norms. Take a look at this:

This insanity is happening on college campuses pic.twitter.com/BrVxICZYqP

— Libs of Tik Tok (@libsoftiktok) September 24, 2021

It turns out that one of the black students involved in this attempt to ethnically cleanse a part of a public university is a Ford Fellow at that university (Arizona State). Here’s why that matters. The Ford Foundation, with $16 billion in assets, is a major funder of the baizuocracy. Whistleblowers at the Ford Foundation leaked internal communications from the non-profit foundation. Excerpts:

As a group, their views on policy issues are uniformly bleeding-heart-Marxist… so much so, that they are actually pretty boring and predictable. The listserv is mostly them patting each other on the back over how brave and smart they are all. The much more compelling undercurrent in these emails, rather than any particular policy issue, is the clear disdain that they hold for unfettered free speech and scholarly debate. It isn’t just one or two individuals. This problem is endemic to their corporate culture. Here are a few real quotes I cherrypicked from their emails to highlight this. I assure you these are not taken out of context:

“I reject these neoliberal invocations of “dialogue” or “understanding the other side”

“Why should people with opposing viewpoints be listened to?”

“I will not engage such arguments in the name of scholarly civility”

“Those who feel compelled to “Hear both sides” is disappointing and intellectually moribund”

“I am disturbed that anyone could raise this question”

“You ask for discussion and debate but how do we debate when somebody won’t acknowledge water is wet? what’s the point.”

“You seek civil debate and discussion but we must first agree that [my] facts are facts”

“I have no interest in this debate that continues to clog my inbox. I will just say this it is an absolute and disgusting abomination that on a list overwhelmingly utilized by Black and Latinx people we are subjected to a racist debate”

“We fordies have no obligation AT ALL to engage in so-called “debate”… if your views are causing harm, this platform is not the right forum. Notably, I know that we use the listserv as a safe space, but right now your cantankerous dialogue is causing young fellows who may have identity issues a lot of harm.”

“I am a new ford fellow and I do not agree with you. I encourage you to take on counseling.”

“the current public discourse (and on this list) we incessantly hear is that “everyone is entitled to their opinion”

“[My opponent] trolls the Ford Fellows listserv, These are not serious attempts at dialogue, My perspective is that her messages are to be ignored”

“Your call for mutual respect here registers as performative rather than genuine, given your apparent refusal to engage or practice the knowledge established in these works, many of which are the products of Ford fellows’ intellectual labor. Just stop. I don’t want to engage further.”

“We especially should not be expected and do not have an obligation to engage in conversations like this”

“Sometimes people who ask us to “educate” them do not really want to learn. They want us to engage in a fake debate, where their “opinions” are given the same weight as our informed, evidence-based beliefs.”

“I find it appalling that one might raise this question”

“I cannot listen in good faith to a person with this viewpoint… I can’t hear you, regardless of who you are”

“all perspectives should not be equally validated on this forum, especially ones that would dismantle our fellowship program, are grossly misinformed, or threaten the lives and well being of people of color.”

“You refer to a lack of dialogue and acceptance of alternate ideas. When that dialogue is centered around a party that accepts and practices racism I can’t get past that to have an active dialogue. You seem to be really focused on getting heard and having respect for both sides.”

UPDATE.3: Oh wow, I learned from the comments box that Frederick Joseph is that loony who launched a viral attack on an AirBNB owner whose decor made Frederick fear that he and his black family (yes, he racialized it) were under threat from secret Satanists.

UPDATE.4: Just received this statement from Emma Sarley:

“I am still processing everything that has happened over the last couple days, and thought it was important to share what I saw and experienced. I absolutely accept responsibility for how I could have handled things differently in that moment.

On Saturday evening, I watched a dog get into several aggressive altercations with other dogs at my local park, and as the owners of this dog were leaving, I suggested that they keep a handle on their dog while visiting this particular park. My reference to “back to your hood” only referred to another dog park outside of this neighborhood park.

I was frustrated and upset, but to be clear – I had no intended racial undertones in my comments whatsoever. I said it because it’s an unstated rule at our local park that when a dog is being aggressive, owners immediately remove them so it can be a calm, welcoming environment for everyone else. However, I fully understand how my words could’ve been interpreted and I deeply wish I had chosen them more carefully. A brief and thoughtless moment in my life has now led to nationwide outrage and hurt. For that, I am sorry.

I want to clarify that I never threatened to call the police. I never went on a tirade. As the dog owners followed me down the street with the phone camera on, I was filled with some panic because I’ve never been in an altercation like this and reacted in an inappropriate way. That’s what you witnessed on that tape.

I’ve lived in New York City for a decade, my Brooklyn neighborhood and dog park is extremely diverse, something I truly love about this city, and I never meant for my words to contribute to pain for anyone. I truly hope we can find understanding and a peaceful resolution to this, for everyone involved.”

The post Frederick Joseph Is A Racist Bully appeared first on The American Conservative.

September 24, 2021

Abortion And Our Liberal Democracy

The Democrat-controlled House today passed a radical pro-abortion bill:

The bill passed the House mainly along party lines, 218-211, with one Democrat voting with Republicans. The vote was largely symbolic as the bill is unlikely to advance in the Senate, where 10 Republicans and all Democrats would need to back the bill in order to meet the 60-vote threshold.

The Senate version of the bill, sponsored by Connecticut Democrat Richard Blumenthal, has 47 co-sponsors, although it’s unlikely to to garner the support of Pennsylvania Democrat Bob Casey, who has previously voted for abortion restrictions, and West Virginia moderate Joe Manchin.

The Women’s Health Protection Act would protect a person’s ability to decide to continue or end a pregnancy and would enshrine into law health care providers’ ability to offer abortion services “prior to fetal viability” without restrictions imposed by individual states, like requiring special admitting privileges for providers or imposing waiting periods.

It also prohibits restrictions on abortion after fetal viability “when, in the good-faith medical judgment of the treating health care provider, continuation of the pregnancy would pose a risk to the pregnant patient’s life or health.”

So, if this were to become law, there would be no restrictions on abortion, anywhere. Partial-birth abortion (see above) would presumably once again be legal, though now abortion providers stay on the right side of the law by injecting poison into the heart of the unborn child to kill her before she is delivered in the abortion procedure.

As NPR reports, this is largely symbolic, but it’s a sign of how ghoulish the pro-choicers are. Check out the abortion laws in European countries — they’re almost all more restrictive than this new bill. Oh, and by the way: the Woke Capitalists are at it again, using corporate policy to attempt to punish states for enacting socially conservative legislation that they don’t like. If a major corporation offered to help its employees move out of a state that had recently passed pro-choice or pro-LGBT legislation, we would never hear the end of it. What corporations and the media are doing is creating a world in which anybody who disagrees with progressive social and cultural values are treated like lepers.

This is why I have mostly given up on liberal democracy — not as an ideal, but as something possible for us. Liberal democracy has been hollowed out from within. How are you going to have a functioning liberal democracy when major stakeholders in society — like corporations, who are democratically unaccountable — consider citizens who disagree with them on certain issues to be untouchables?

Yesterday I gave an interview to Matt K. Lewis, who talked mostly about Hungary. I told him that I had mostly given up on liberal democracy, not because I don’t like it — I would prefer to live in a liberal democracy — but because I no longer believed that we had a real liberal democracy. Why not? Because the forms exist, but the progressive left — including Woke Capitalists — has hollowed them out. I told him that I thought the future was going to be a struggle between left-wing illiberal democracy (such as is coming into being here in the US), and right-wing illiberal democracy (like Viktor Orban is trying to establish in Hungary). That being the case, I know whose side I’m on.

Not everybody likes to hear that:

This is exactly the kind of defeatism about liberal democracy, and the romance of the illiberal leader who protects us from each other, that I decry in my new book. Sorry, @roddreher, but this is basically surrendering your agency as a citizen and as a person. https://t.co/c1l4h0fu8d

— Tom Nichols (@RadioFreeTom) September 24, 2021

It is neither, but I’ll let that pass. I would just point out that the people on the center-right (like my friend Tom) and those on the center-left, both of whom see no problems with liberal democracy as we have today, are almost never social or religious conservatives. They have already accepted the social liberalization of the country, and don’t seem to have big qualms about the American laïcité coming into being.

I told Matt K. Lewis, and I’ll repeat it here, that I am definitely not a Trump supporter. Furthermore, I think the January 6 business was a total disgrace — and that Donald Trump became anathema to me after the way he behaved on that day. But I do not share the views of Tom et alia that Donald Trump is the only mortal threat to liberal democracy (if he’s a threat at all). I hope Trump does not run in 2024, and believe that a second Trump presidency would be on balance bad for the country. But I worry far, far more about what continued governance by the woke ruling class is going to do to our country, and its democracy. Oligarchs like Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates concern me much more than Trump does. I am far more afraid of the denizens of Silicon Valley than of those who live in an Appalachian holler. I’m not kidding.

Was talking earlier today to a conservative Catholic friend about all this, and he says that our side keeps losing to the woke because we are terrible in opposition. We have either a GOP establishment that is totally comfortable with baizuo ideology as long as it protects tax cuts and national security hawkishness, or we have the Trump cult. My friend says that the organized Right behaves like a “controlled opposition,” because even if they win elections they won’t be able to change the system, and don’t even have a plan to.

If the Right could come up with a genuinely intelligent person who can operate outside of the strictures of the Trump cult, but who also understands the weaknesses of the GOP establishment, and then you have a real threat to the system. This is what Viktor Orban has been trying to do within a European context. Orban is far ahead of the American Right on how to confront the actual threat to the things we supposedly value. He understands — as does Ryszard Legutko — that the globalists and establishmentarians use the language, concepts, and institutions of liberal democracy to mean something else.

Here in America, though, our Right can’t seem to figure out what legitimate causes are worth supporting, and what’s just grift and conspiracy theory. Until we can, the only thing the Right is good for is serving as a temporary check on the left’s excess and incompetence.

Going back to the abortion bill: the Democrats and their corporate allies are bound and determined not to let states make their own laws when those laws conflict with what woke activists want. How is this a workable liberal democracy? The choice we social and religious conservatives are given is to do whatever the oligarchs and the baizuocracy tell us to do — and we will get little to no support at all from establishment conservatives. Look, I get it. Some of the things the Trump extremists say and do make me crazy. But they are not the worst problem, not by a long shot.

I’ll leave you with this link to the infamous 1996 First Things symposium on abortion and the legitimacy of our liberal democracy. I seem to recall that it upset some of the magazine’s inner circle so much that they quit writing for it, because the position the magazine staked out seemed illiberal and unpatriotic. The point of the symposium was to discuss the claim that the judiciary had removed the ability of the American people to decide how it wants abortion to be treated in law. Has this gone so far that Americans are justified in withdrawing support for the regime? The introduction says:

Americans are not accustomed to speaking of a regime. Regimes are what other nations have. The American tradition abhors the notion of the rulers and the ruled. We do not live under a government, never mind under a regime; we are the government. The traditions of democratic self-governance are powerful in our civics textbooks and in popular consciousness. This symposium asks whether we may be deceiving ourselves and, if we are, what are the implications of that self-deception. By the word “regime” we mean the actual, existing system of government. The question that is the title of this symposium is in no way hyperbolic. The subject before us is the end of democracy.

Since the defeat of communism, some have spoken of the end of history. By that they mean, inter alia, that the great controversies about the best form of governance are over: there is no alternative to democracy. Perhaps that, too, is wishful thinking and self-deception. Perhaps the United States, for so long the primary bearer of the democratic idea, has itself betrayed that idea and become something else. If so, the chief evidence of that betrayal is the judicial usurpation of politics.

Politics, Aristotle teaches, is free persons deliberating the question, How ought we to order our life together? Democratic politics means that “the people” deliberate and decide that question. In the American constitutional order the people do that through debate, elections, and representative political institutions. But is that true today? Has it been true for, say, the last fifty years? Is it not in fact the judiciary that deliberates and answers the really important questions entailed in the question, How ought we to order our life together? Again and again, questions that are properly political are legalized, and even speciously constitutionalized. This symposium is an urgent call for the repoliticizing of the American regime. Some of the authors fear the call may come too late.

I would love to read a similar symposium now, 25 years later, not about abortion per se but about the way the baizuocracy (rule by the woke) and its corporate allies has diminished America’s liberal democracy. I understand — really, I do! — why a figure like Trump is such a threat to the system. But many of those within the system and its institutions are so focuses on Trump that they miss the fact that the real threat is calling from inside the house.

UPDATE: Look what else is in that same bill:

(8) The terms ‘‘woman’’ and ‘‘women’’ are used in this bill to reflect the identity of the majority of people targeted and affected by restrictions on abortion services, and to address squarely the targeted restrictions on abortion, which are rooted in misogyny. However, access to abortion services is critical to the health of every person capable of becoming pregnant. This Act is intended to protect all people with the capacity for pregnancy—cisgender women, transgender men, non-binary individuals, those who identify with a different gender, and others—who are unjustly harmed by restrictions on abortion services.

These people are not only at war with their countrymen; they are at war with reality.

The post Abortion And Our Liberal Democracy appeared first on The American Conservative.

Eva’s Choice: Vaccine Passports Or Exile

Elsewhere on TAC today, Dutch commentator Eva Vlaardingerbroek write about the vaccine passports mandatory in the Netherlands from this weekend, and what this means. Excerpts:

Beginning tomorrow, September 25, everyone in the Netherlands above the age of 13 will need a “Digital Covid Certificate” in order to be allowed into restaurants, bars, theaters, cinemas, and concert halls. Basically, the things that make life enjoyable for most people, will be limited to those who are in possession of a Q.R. code that indicates they are either vaccinated, tested, or have recovered from Covid-19 within the past 160 days.

What is interesting—and, in my view, incredibly telling—about the Dutch situation in particular is that a whopping 85 percent of the Dutch population is currently already fully vaccinated. More than a year and a half into the Covid-crisis, it is estimated that 95 percent of the population has antibodies, and currently only 200 people are in the ICU. Yet it is at this very moment that our government decides to introduce the most far-reaching and invasive measure the Dutch have seen to date. This is only the beginning.

She makes an argument for why the vaccine passports are not necessary at this point, and won’t actually do what the government claims they will do. So why have them? What is the end game? She goes on:

Frustratingly, only a very limited number of people in the West see what is really at stake here. Most fail to see that, once these Q.R. systems are enforced and people have become accustomed to them, these systems can be used for a variety of other purposes as well. It is most likely not a coincidence that a couple of weeks ago, suddenly, a nationwide poll was conducted to enquire how the Dutch viewed the possibility of a “personal carbon credit” system. Nevertheless, a large majority seems to believe—or want to believe—that all of this is for the common good, or that it is at least all temporary and won’t “get that far.”

I hope they are right, but I cannot help feeling that Tocqueville hit the nail on the head, as he often did, when he wrote that the type of despotism democratic people have to fear will in no way look like the despotism and tyranny our ancestors endured: “It would be more extensive and more mild; it would degrade men without tormenting them,” he wrote in 1840. And, in a way, the fact that it happens more gradually is what makes it arguably even more dangerous. After all, a people that do not realize they are losing their freedom will not fight for it. They will simply let it slip through their fingers.

Read it all. She’s talking about soft totalitarianism. And she’s talking about the fact that unless she gets vaccinated, she and all the others like her are going to be essentially turned into recluses in their own country.

It’s a perfectly reasonable argument Eva Vlaardingerbroek makes. Maybe she’s wrong — but there’s nothing weird or inflammatory about the objections she raises. But look what happened:

Instagram just took my story down with my article for @amconmag on the slippery slope of vaccine passports, stating it contained “harmful misinformation”.

Thanks for proving my point, @instagram. pic.twitter.com/ySCtTJBB2Y

— Eva Vlaardingerbroek (@EvaVlaar) September 24, 2021

What “harmful misinformation”? Where did she lie or mislead? Or is the “harmful misinformation” simply disagreeing with the state’s scheme?

Did you catch Bari Weiss’s Substack newsletter this week, in which she presented a variety of views of people regarding vaccine mandates? Here’s an interesting point made by a doctor and a health care economist:

Now, looking beyond the epidemiology, it’s worth considering the psychology that comes into play when we start forcing people to do things: It is practically a mathematical certainty that the mandates will lead many people to distrust the government, leading experts at places like the Centers for Disease Control, and our most prominent research universities even more than they do now. Why, the thinking goes, are you forcing me to do something that, you insist, is obviously good for me? If it were obviously good for me, you wouldn’t have to force me to do it.

The mandates, far from persuading the unvaccinated to fall into line, will further undermine the authority of those pushing them — and, critically, it will make it that much harder to persuade the public to get vaccinated when an even more dangerous pandemic sweeps the globe.

There is a deeper, darker reason for the vaccine mandates. Within each of us, there is a primal urge to avoid infection and shun the infected. This stretches back to the ancient world. Medical students must suppress the urge to shun the infected in order to become good doctors.

Alas, mandate supporters have succumbed, to an extent, to this urge. They are fueled by it; they fuel it. They are creating, consciously or unconsciously, an outgroup of the unvaccinated — who happen to include a disproportionate number of poor people and minorities. It is awful public policy.

Look, I think people should be vaccinated. I found out just yesterday that a friend’s uncle, a man my age (54), reported to my friend on Sunday that he probably had Covid, and was feeling pretty bad. Friend told his uncle to go to the doctor in the morning. The next day, the uncle died. The funeral is today. I believe that for many of us — including 54-year-old me, with my compromised immune system — the risks from taking the vaccine are less than the risk from Covid. But I have intelligent, thoughtful friends (like Eva Vlaardingerbroek) who are not going to take the vaccine, and aren’t hysterics about it. I respect their choice, and I do not want a world in which these people are driven to society’s margins. Another friend of mine was fired from his academic job last month for refusing the vaccine. This is unjust. I believe, with Adrian Vermeule (in the Bari Weiss symposium), that the state has, in principle, the power to force vaccines on its population in an extreme public health situation. But Covid, as bad as it is, does not strike me as serious enough to justify broaching the invasion of a citizen’s body.

Plus, look at today’s news, about how the CDC chief overruled her own experts and recommended Pfizer booster shots for at risk workers— a decision that was clearly political. The CDC panel said there just weren’t enough data to justify this move, but she pushed ahead anyway, because that’s what the White House wants. We’re all supposed to get in line, then, because the CDC head is making a decision based on politics, not scientific consensus?

And now, social media censors are deciding what kind of questions we can and can’t ask about all this?

I find these people to be a greater threat to the common good than the unvaccinated.

The post Eva’s Choice: Vaccine Passports Or Exile appeared first on The American Conservative.

Cardinal Pell Vs. The Benedict Option

National Catholic Reporter interviewed Cardinal George Pell, who said at the end:

When asked during his latest interview what reading recommendations he would offer for those seeking a better understanding of the church, Pell ticked off a number of prominent conservative writers.

Among those he named were New York Times columnist Ross Douthat and Pope John Paul II biographer George Weigel, before offering a limited endorsement of Rod Dreher’s The Benedict Option, which advocates for Christians to withdraw from the mainstream and focus on a renewal of Christian counterculture.

“The Benedict option is not my option,” Pell said. “I’m not sympathetic to just a small, little elite church.”

He added: “I would like to keep as many of the semi-religious slobs like myself in the stream.”

I have immense respect, even affection, for Cardinal Pell, who so bravely bore the injustice of his imprisonment, so it disappoints me to see him mischaracterize The Benedict Option like this. The point of the book is that in the roiling whitewater river that is liquid modernity, anyone who wants to hold on to any historically orthodox form of the Christian faith is going to have to live counterculturally, and in some meaningful sense outside the mainstream. Does the Cardinal doubt this? I wonder if he’s living in the past in his imagination — a past in which people could kind of go along with the flow, not being especially devout. That’s the world I grew up in, and is certainly the world George Pell grew up in. My family weren’t big churchgoers, but we didn’t question the truth claims of Biblical Christianity. The world we live in today could hardly be more different.

I wonder if Cardinal Pell even read the book. If he did, I would love to know why he believes that the book calls for a “small, little elite church”. I quote young Father Joseph Ratzinger prophesying that that is what is going to come into being, at least in the West. No Christian wants that to happen, but Father Ratzinger said (in 1969) that this was coming, whether we wanted it to or not. There is going to be a massive falling away — we are living through that now, and it’s going to get much worse. Cardinal Pell’s remarks are like saying he doesn’t like what that guy Noah is saying about how we need to build an ark, because he doesn’t want to cruise with a small, little elite group of passengers.

I will never, ever understand why so many people who should know better mischaracterize my book like this. I could be wrong in my diagnosis and prescription, but come on, guys, let’s argue about what I actually wrote, and wrote clearly, not what you think I wrote. One of the group of heroes in my book is the Tipi Loschi, the Catholic community in San Benedetto del Tronto, on Italy’s Adriatic coast. They are a bunch of normal Catholics, really happy, open-hearted people. If anybody reading this knows Cardinal Pell, ask him to please take a trip outside of Rome to visit the Tipi Loschi. They are the Benedict Option. What an inspiring group of believers!

I hope the cardinal also reads the text of the speech that Archbishop Georg Gänswein gave on September 11, 2018, in a hall at the Italian Senate. Monsignor Gänswein, the personal secretary of Benedict XVI, gave a powerful endorsement of The Benedict Option. He said, in part:

The number of people turning their back on the Church is dramatic. Even more dramatic, however, is another statistic: According to the most recent surveys, of the Catholics who have not yet left the Church in Germany, only 9.8 percent still meet on Sunday in their places of worship to celebrate the Blessed Eucharist together.

This brings to mind Pope Benedict’s very first journey after his election. On May 29, 2005, on the banks of the Adriatic Sea, he reminded the predominantly youthful audience that Sunday is a “weekly celebration of Easter”, thereby expressing the identity of the Christian community and the center of its life and mission. However, the theme of the Eucharistic Congress (“We cannot live without Sunday”) goes back to the year 304, when Emperor Diocletian forbade Christians under death penalty to possess Holy Scripture, to meet on Sundays to celebrate the Eucharist, and to construct rooms for their meetings.

“In Abitene, a small village in present-day Tunisia, 49 Christians were taken by surprise one Sunday while they were celebrating the Eucharist, gathered in the house of Octavius Felix, thereby defying the imperial prohibitions. They were arrested and taken to Carthage to be interrogated by the Proconsul Anulinus.

Significant among other things is the answer a certain Emeritus gave to the Proconsul who asked him why on earth they had disobeyed the Emperor’s severe orders. He replied: “Sine dominico non possumus”: that is, we cannot live without joining together on Sunday to celebrate the Eucharist. We would lack the strength to face our daily problems and not to succumb.

After atrocious tortures, these 49 martyrs of Abitene were killed. Thus, they confirmed their faith with bloodshed. They died, but they were victorious: today we remember them in the glory of the Risen Christ.”

In other words, what we, as children of the so-called “popular church”, have come to know as the “Sunday obligation” is, in fact, the precious, unique characteristic of Christians. And it is much older than any Volkskirche. Therefore, it is truly an eschatological crisis that the Catholic Church has been in for a long time now, just as my mother and father reckoned they could perceive it in their day – with “horrors of devastation in holy places” – something perhaps every generation in church history recognized from a distance on its own horizon.

More Gänswein:

Obviously, I am not alone in this. In May, the Archbishop of Utrecht in Holland, Cardinal Willem Jacobus Eijk, confessed that the present crisis reminded him of the “final trial” of the Church, as the Catechism of the Catholic Church describes it in paragraph 675, which the Church must undergo before the return of Christ, as a trial that ” will shake the faith of many believers”. The Catechism continues: “The persecution that accompanies her pilgrimage on earth will unveil the ‘mystery of iniquity.’”

And:

In the great cultural upheaval of the migration period of the Völkerwanderung and the emergence of new structures of state, the monasteries were the place where the treasures of the old culture survived and at the same time a new culture was slowly formed by them, said Benedict XVI at the time and asked:

“But how did it happen? What motivated men to come together to these places? What did they want? How did they live?

First and foremost, it must be frankly admitted straight away that it was not their intention to create a culture nor even to preserve a culture from the past. Their motivation was much more basic. Their goal was: Quaerere Deum [to seek God]. Amid the confusion of the times, in which nothing seemed permanent, they wanted to do the essential – to make an effort to find what was perennially valid and lasting, life itself. They were searching for God. They wanted to go from the inessential to the essential, to the only truly important and reliable thing there is…they were seeking the definitive behind the provisional… Quaerere Deum – to seek God and to let oneself be found by him, that is today no less necessary than in former times. A purely positivistic culture which tried to drive the question concerning God into the subjective realm, as being unscientific, would be the capitulation of reason, the renunciation of its highest possibilities, and hence a disaster for humanity, with very grave consequences. What gave Europe’s culture its foundation – the search for God and the readiness to listen to him – remains today the basis of any genuine culture.”

These were the words of Pope Benedict XVI on September 12, 2008 about the true “option” of Saint Benedict of Nursia. – After that, all that remains for me to say about Dreher’s book is this: It does not contain a finished answer. There is no panacea, no skeleton key for all the gates that were open to us for so long and have now been thrown shut again. Between these two books covers, however, there is an authentic example of what Pope Benedict said ten years ago about the Benedictine spirit of the beginning. It is a true “Quaerere Deum”. It is that search for the true God of Isaac and Jacob, who showed his human face in Jesus of Nazareth.

For this reason, a sentence from chapter 4,21 of the Rule of Saint Benedict comes to my mind, which also pervades and animates the entire book of Dreher as Cantus Firmus. This is the legendary “Nihil amori Christi praeponere”. That means translated: the love of Christ must come before all else. It is the key to the whole miracle of occidental monasticism.

Benedict of Nursia was a lighthouse during the migration of peoples, when he saved the Church through the turmoil of time and thus in a certain sense re-founded European civilization. But now, not only in Europe, but all over the world, we are experiencing for decades a migration of peoples that will never come to an end again, as Pope Francis has clearly recognized and urgently speaks about to our consciences. That is why not everything is different this time, as compared to how it was then.

If the Church does not know how to renew itself again this time with God’s help, then the whole project of our civilization is at stake again. For many it looks as if the Church of Jesus Christ will never be able to recover from the catastrophe of its sin – it almost seems about to be devoured by it.

The Benedict Option is about keeping the search for God alive in a world where everything is working against the search. Before Mons. Gänswein gave that speech, Vatican journalist friends warned me that whatever Gänswein said will have been approved by Benedict XVI. I was so anxious, because I feared that BXVI, a hero of mine, would not have liked the book. In fact, if the journalists were right, then judging by the Gänswein speech, BXVI thinks the book is a light in a time of darkness.

I hope Cardinal Pell will read it to see why the Pope Emeritus — or at least his closest aide — finds the book to be so necessary and so hopeful. I hope you will too, if you haven’t already. It’s much later than many Western Christians think.

On the other hand, it is possible that Cardinal Pell did read the book, and has drawn the negative conclusion. If so — and if you are an actual reader of the book (versus a reader about the book) who has done the same — I genuinely want to know how you arrived at that conclusion. I think it’s possible that out of charity, some Christians hate to think about the church being exclusive. I get that, and it’s not always a bad thing. In fact, it’s probably a good thing, because it shows mercy.

But there are limits. In Evangelicalism, the “seeker-friendly” model of church has been criticized for being so given over to attracting non-Christians that it badly watered down what it means to be Christian. Being a Christian requires discipleship. A main point of The Benedict Option is that without serious discipleship, Christianity is going to dissolve in liquid modernity. It’s already doing it, and nothing many churchmen — even good ones, like Cardinal Pell — are saying and doing is going against the tide. It’s what little guys on the ground — men like Marco Sermarini of the Tipi Loschi, like the monks of Norcia and the Community of the Raven And The Dove, a tiny community of believing families that have moved there to live near them, and so many others — are doing that might make a difference.

Obviously I don’t know what Cardinal Pell’s thought process is that led him to this conclusion, but I have observed in older Catholic churchmen a deep and understandable reticence to see the world as it is today. In France back in 2018 on the Benedict Option book tour, I quickly discerned a big difference between Catholics aged 55 and older, and those aged 40 and under (the rest of us are in the middle). The older Catholics pretty much rejected the book’s premises, but the younger ones accepted them as obvious truths. I surmised that the older Catholics could not bear to accept that the world had moved on, and did not have any use for the Church. They still wanted to believe if only we tweaked this or that, that the world would make a place for the Church. By contrast, the younger Catholics had internalized that as faithful Christians, they were going to have to live on the margins of society. They were interested in learning more about how to do that.

It’s not that they were uninterested in evangelization. It’s rather that they realized that Christians cannot give the world what they don’t have — and the modern world is structured in ways that make it harder to be faithful than in ages past. I got the impression that the older churchmen were living in the past, while the younger Catholics were trying to figure out how they and their families could have a Christian future.

The bottom line is this: at some point, if the Church is not going to be completely absorbed by the world, and assimilated, it is going to have to draw clear lines around what it means to be a faithful Christian, and defend those lines. It’s not because the Church wants to be mean. It’s because we Christians believe, or ought to believe, that the Bible discloses truth about who God is, who we are, and how we are to relate to Him, and to the world into which we have been thrown. To forget those truths is to lose the Way. You can have a church full of people who are hearing a false gospel, and the fact that the false gospel is popular does no good for the Kingdom of God. The Church’s doors should always be open to seekers and people struggling with belief — but without discipling those who have committed to the faith, and without creating communities of discipleship, the forces of dissolution and fragmentation in liquid modernity will win. That is the main point of The Benedict Option: how we Christians of the 21st century are supposed to deal creatively with that hard truth.

The post Cardinal Pell Vs. The Benedict Option appeared first on The American Conservative.

September 23, 2021

SJW Scientists Cancel Jedi Order

I thought this was Babylon Bee. Nope — it’s an op-ed from Scientific American! Excerpts:

The acronym “JEDI” has become a popular term for branding academic committees and labeling STEMM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics and medicine) initiatives focused on social justice issues. Used in this context, JEDI stands for “justice, equity, diversity and inclusion.” In recent years, this acronym has been employed by a growing number of prominent institutions and organizations, including the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. At first glance, JEDI may simply appear to be an elegant way to explicitly build “justice” into the more common formula of “DEI” (an abbreviation for “diversity, equity and inclusion”), productively shifting our ethical focus in the process. JEDI has these important affordances but also inherits another notable set of meanings: It shares a name with the superheroic protagonists of the science fiction Star Wars franchise, the “Jedi.” Within the narrative world of Star Wars, to be a member of the Jedi is seemingly to be a paragon of goodness, a principled guardian of order and protector of the innocent. This set of pop cultural associations is one that some JEDI initiatives and advocates explicitly allude to.

Wow, you wokesters really pulled off a coup with this branding. To associate your ideology with the Jedi is to be halfway to claiming the hearts and minds of every new generation of young Americans. Well done!

Ha ha! Actually, the op-ed is about how “problematic” Star Wars is from a social justice point of view. More (emphases in the original):

The Jedi are inappropriate mascots for social justice. Although they’re ostensibly heroes within the Star Wars universe, the Jedi are inappropriate symbols for justice work. They are a religious order of intergalactic police-monks, prone to (white) saviorism and toxically masculine approaches to conflict resolution (violent duels with phallic lightsabers, gaslighting by means of “Jedi mind tricks,” etc.). The Jedi are also an exclusionary cult, membership to which is partly predicated on the possession of heightened psychic and physical abilities (or “Force-sensitivity”). Strikingly, Force-wielding talents are narratively explained in Star Wars not merely in spiritual terms but also in ableist and eugenic ones: These supernatural powers are naturalized as biological, hereditary attributes. So it is that Force potential is framed as a dynastic property of noble bloodlines (for example, the Skywalker dynasty), and Force disparities are rendered innate physical properties, measurable via “midi-chlorian” counts (not unlike a “Force genetics” test) and augmentable via human(oid) engineering. The heroic Jedi are thus emblems for a host of dangerously reactionary values and assumptions. Sending the message that justice work is akin to cosplay is bad enough; dressing up our initiatives in the symbolic garb of the Jedi is worse.

This caution about JEDI can be generalized: We must be intentional about how we name our work and mindful of the associations any name may bring up—perhaps particularly when such names double as existing words with complex histories.

I didn’t realize until I read the whole thing that this is not a parody — they are stone-cold serious. Scientific American is not known as a humor magazine; its editors published this lunacy with a straight face.

How is it that we are losing to these people? How do ideologues this hopelessly idiotic keep winning and winning? How is it that they or their allies control all the high ground?

The post SJW Scientists Cancel Jedi Order appeared first on The American Conservative.

Hero New Yorker: ‘That’s NOT OK, Cupid!’

The online dating app OKCupid came out this summer with a new advertising campaign, talking about all the different kinds of lovers it serves. Here’s another:

These things appeared on the subway in New York City. Imagine having to answer the questions: “Mommy, what’s a submissive? Daddy, what’s a pansexual?” Etc. The pornification of the public square seems irreversible.

Well, an angry New York woman had enough, and went crazy on the D train. Look at this hero:

UNBELIEVABLY BASED (Pt.1) pic.twitter.com/TcBZWmchBC

— Dayum Nobueno (@DamnNobueno) September 22, 2021

UNBELIEVABLY BASED (Pt.2) pic.twitter.com/TUyE4PKXOV

— Dayum Nobueno (@DamnNobueno) September 22, 2021

By the way, OK Cupid is also doing politics:

And then there’s the political messaging which is equally as gross. pic.twitter.com/gHhDteVWfF

— Megan Fox

(@MeganFoxWriter) September 23, 2021

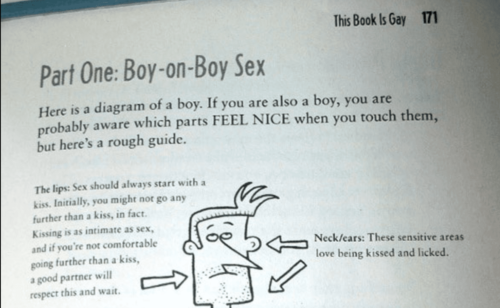

UPDATE: Ever heard of a book titled This Book Is Gay? It’s billed as an LGBT “instruction manual” for young adults. It got a great review when it came out in 2015 from School Library Journal, quoted on the Amazon page:

From School Library Journal:

Gr 10 Up—This witty, no-holds-barred look at the LGBTQ experience provides information that parents or school friends often can’t or won’t give. The book covers dating, religious perceptions of LGBTQ people, bullying, coming out, and more. Employing occasionally snarky, informal language, Dawson provides very direct, frank guidance (among the subheadings are “Doing the Sex” and “Why Are Gay Men So Slutty?”), including sexual advice (complete with labeled anatomical cartoons). However, these are all topics about which teens are curious. Though the book has an intended audience, a variety of readers will appreciate it. VERDICT An insightful option for those with questions about what it’s like to be LGBTQ.—April Sanders, Spring Hill College, Mobile, AL

One of you readers sent me a link to an interview that the parents’ rights group Mass Resistance did with a librarian about the book being available for kids. Here is an NSFW page in which Mass Resistance presents photographs taken from the book, which instructs (with drawings) young readers how to have gay sex, including anal sex, oral sex, and mutual masturbation. Here’s a safe snapshot:

Is it a good idea to have books in the kids’ section of a library teaching young readers how to have boy-on-boy sex (or boy-on-girl sex for that matter)? The interviewer spoke to the top county librarian in a Wyoming town where some parents are asking the library to remove the book from its shelves. From the interview Ben, a local activist, did with Terri, the librarian:

Ben: OK, I’ll bring it back to books: Do you think it’s appropriate to teach a 10-year-old child how to have anal sex?

Terri: Well, what do you think? What do you think the answer to that is? That’s kind of an insulting question. So I don’t know. I’m not even going to answer it.

Ben: Well I would really like to know, because there are actual books in this library which do that very thing.

Terri: Has a 10-year-old ever had that happen? That’s such an extreme viewpoint.

Ben: Why is it being introduced in the books in the library, then?

Terri: Because there are books in the library, and sometimes, I don’t know, I don’t even know how to answer that. This is such an insulting question, it’s hard for me.

Ben: Well, do you see where I’m coming from, though, because that is actually in the children’s section in this library.

Terri: I haven’t seen it. I can’t tell you any opinion until I’ve read the book and seen it in context. I don’t know.

Ben: Well, I’m not sure how it’s insulting if you can’t even answer it. That’s where I’m coming from and I’m surprised by the reaction. It just seems like such an obviously wrong thing to me.

Terri: I have to see it to believe it. So I haven’t seen it yet.

Good for Ben and his colleagues. I just checked my county library system, and there are copies of this book all over. In the future, we will be judged harshly for what we did to our kids in this era.

The post Hero New Yorker: ‘That’s NOT OK, Cupid!’ appeared first on The American Conservative.

Generation Greta: Too Afraid To Live

The Lancet recently released a study involving ten countries around the world, of young people’s (aged 16 to 25) stance towards the future in light of climate change. It was pretty distressing. For example, 39 percent say that they are not sure about having children. Huge numbers — almost half of young Americans surveyed — agree with the statement “humanity is doomed.”

Ben Sixsmith, writing on his excellent Substack (this entry is for subscribers only, but you should become one), says that some degree of existential pessimism is inevitable:

Once mankind developed the capacity for self-destruction, the sense that our luck could not endure forever was baked into our consciousness. How can our tools grow more powerful, and more accessible, without being misused? “If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall,” said Anton Chekov as a rule for writing, “In the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off.” The same logic of grim inevitability leads many of us to wonder about our final page.

I remember the winter day — probably it was 1979, when I was twelve — when I was sitting in my father’s Bronco, driving across a wet field on our way back from a morning of deer hunting. I had worked out somehow that it would take a Soviet nuclear-armed missile 19 minutes to reach us from its launch pad. We were always 19 minutes away at any moment from certain doom. I told that to my father, whose answer was something like, “Don’t worry about it.” I knew instantly that he had no answer for me, because there was no reassuring response. It was such an electric moment because it was the first time I knew that there were some things in the world outside of the control of grown-ups.

My father told me years later that he had been in the US Coast Guard during the Cuban missile crisis, and that his crew had been prepared by their commanders for nuclear war. They really did think this was going to happen. Can you imagine what that felt like? Well, I can to some extent, because I spent the early 1980s very scared about a nuclear holocaust. But my dad and his crew really did think it was going to happen right then. What a gift it has been to those born after the end of the Cold War, that they could grow up without this fear. Of course a nuclear war could still happen. Russia still has its weapons, as do we … and as does China, and a handful of other nations. But the palpable fear disappeared with the Cold War.

This is to say, in part, that this kind of existential doom felt by the young today feels familiar. One difference, though, is that there was no certitude that a nuclear war would happen. As more and more data come in, the certitude grows that the climate is shifting in ways that will make life on this planet more difficult. On the other hand, a nuclear war is all but unsurvivable (and those who did survive would envy the dead). We have the capacity to use our intelligence to adapt to whatever climate change throws at us. It’s not going to be easy or pleasant, but life can go on, if we want it to. What is interesting to me is the seeming unwillingness of so many young people (in the survey) to fight for the continuation of life.

Think about it: my father’s generation was born into a catastrophic economic crisis, the Great Depression. What brought that crisis to an end was a terrible war, World War II. What brought that war to an end was the use of the atomic bomb. Four years later, the Soviets had the bomb too, and my father graduated high school and entered a world in which the possibility of nuclear annihilation was a fact of life.

And yet he, like everyone else of his generation, carried on. The Baby Boom was underway. People had lots of children, despite it all. Nuclear apocalypse is a much worse thing than climate change, and yet people back then had hope, and expressed that hope in the willingness to create the next generation.

What has happened to us? What have we lost that the people of my father’s generation, and older generations, had, that gave them resilience?

People of my father’s generation were the last ones to be formed by the Before Times — that is, by the remnants of a Christian culture. The Sixties marked what Philip Rieff called the “triumph of the therapeutic” — a mode of being that had arisen in the early 20th century, but which conquered the culture in the Sixties. In 1966, Rieff published his great book The Triumph of the Therapeutic, which was absolutely prophetic. Here are two relevant excerpts; emphases are mine:

I, too, aspire to see clearly, like a rifleman, with one eye shut; I, too, aspire to think without assent. This is the ultimate violence to which the modern intellectual is committed. Since things have become as they are, I, too, share the modern desire not to be deceived. The culture to which I was first habituated grows progressively different in its symbolic nature and in its human product; that double difference and how ordained augments our ambivalence as professional mourners. There seems little likelihood of a great rebirth of the old corporate ideals. The “proletariat” was the most recent notable corporate identity, the latest failed god. By this time men may have gone too far, beyond the old deception of good and evil, to specialize at last, wittingly, in techniques that are to be called, in the present volume, “therapeutic,” with nothing at stake beyond a manipulatable sense of well-being. This is the unreligion of the age, and its master science. What the ignorant have always felt, the knowing now know, after millennial distractions by stratagems that did not heighten the more immediate pleasures. The systematic hunting down of all settled convictions represents the anti-cultural predicate upon which modern personality is being reorganized, now not in the West only but, more slowly, in the non-West. The Orient and Africa are thus being acculturated in a dynamism that has already grown substantial enough to torment its progenitors with nightmares of revenge for having so unsettled the world. It is a terrible error to see the West as conservative and the East as revolutionary. We are the true revolutionaries. The East is swiftly learning to act as we do, which is anti-conservative in a way non-Western peoples have only recently begun fully to realize for themselves.

And:

As cultures change, so do the modal types of personality that are their bearers. The kind of man I see emerging, as our culture fades into the next, resembles the kind once called “spiritual”—because such a man desires to preserve the inherited morality freed from its hard external crust of institutional discipline. Yet a culture survives principally, I think, by the power of its institutions to bind and loose men in the conduct of their affairs with reasons which sink so deep into the self that they become commonly and implicitly understood—with that understanding of which explicit belief and precise knowledge of externals would show outwardly like the tip of an iceberg. Spiritualizers of religion (and precisians of science) failed to take into account the degree of intimacy with which this comprehensive interior understanding was cognate with historic institutions, binding even the ignorants of a culture to a great chain of meaning. These institutions are responsible for conveying the social conditions of their acceptance by men thus saved from destructive illusions of uniqueness and separateness. Having broken the outward forms, so as to liberate, allegedly, the inner meaning of the good, the beautiful, and the true, the spiritualizers, who set the pace of Western cultural life from just before the beginning to a short time after the end of the nineteenth century, have given way now to their logical and historical successors, the psychologizers, inheritors of that dualist tradition which pits human nature against social order.Undeceived, as they think, about the sources of all morally binding address, the psychologizers, now fully established as the pacesetters of cultural change, propose to help men avoid doing further damage to themselves by preventing live deceptions from succeeding the dead ones. But, in order to save themselves from falling apart with their culture, men must engender another, different and yet powerful enough in its reorganization of experience to make themselves capable again of controlling the infinite variety of panic and emptiness to which they are disposed. It is to control their dis-ease as individuals that men have always acted culturally, in good faith. Books and parading, prayers and the sciences, music and piety toward parents: these are a few of the many instruments by which a culture may produce the saving larger self, for the control of panic and the filling up of emptiness. Superior to and encompassing the different modes in which it appears, a culture must communicate ideals, setting as internalities those distinctions between right actions and wrong that unite men and permit them the fundamental pleasure of agreement. Culture is another name for a design of motives directing the self outward, toward those communal purposes in which alone the self can be realized and satisfied.Rieff is not an easy writer to read. What he’s saying here, and what he says in his book, is that we of the modern West are a truly revolutionary culture. We have arrived at the conclusion that there are no higher ideals to organize ourselves around, so the only thing left for us to do is pursue the well being of the Self. This is what he means by a “therapeutic” culture: one whose purpose is to help humankind cope with anxiety. Rieff said that religious man is born to be saved, but psychological man is born to be pleased. This is us. And now, with our young people faced with panic and emptiness, we have given them nothing that allows them to control it. The best we can do is distract them.I think wokeness — or, I guess we should use the new term, wokism — is a pseudo-religious attempt to control the panic and emptiness of the post-Christian therapeutic order. I have written in Live Not By Lies that the best way to understand wokism is not as a political movement, but as a false religion. This graf from an old Gregory Wolfe essay nails the problem with ideological substitutes for religion:

Switch “wokism” for “Marxism,” and you will understand. Nevertheless, it is useful to think of wokism in religious terms, because it is meant to play the psychological role that religion once did. It is supposed to restore order to the chaos by imposing humankind’s will on it. Many people who are desperate for a sense of meaning in the current chaos are clinging to wokism because it promises them a sense of meaning, purpose, and solidarity. Older people may not really believe in it, but they submit to it because it’s the way of the world today, and if they want to maintain their position in the system, they convert outwardly, preferring to live by lies than to risk a loss of comfort and status.I don’t want to say that sense of doom that the young have (re: the Lancet survey) is inappropriate. There can be no doubt that they face tremendous challenges trying to build a life today. We have deprived them of the only real source of hope: the conviction that there is God who orders the universe, and who loves them, and who guarantees that their suffering is not meaningless. To refuse to have children on the principle that it would be wrong to bring them into this world is to surrender hope in the future. It’s an extraordinary thing, given the dismal prospects that most people who have ever lived faced — and yet, they carried on. Not us. We face this global crisis at precisely the time when we in the West, with our global communications reach, have denied ourselves and the world what we all need to endure, even triumph over, adversity.Hear me clearly: the therapeutic gospel — whether in its left-wing forms (woke Christianity) or right-wing forms (prosperity gospel) is false teaching. If you are in a therapeutic church, now is the time to make plans to leave. If you are not in a church that is teaching you why and how to endure suffering for the truth, then you are not in a church that is preparing you for the world as it is today, and the world very shortly to come.Marxism does appeal to the alienated, but in precisely the opposite way to the higher religions. The religious sensibility requires faith, an openness to being. The order of being precedes man; man must therefore attune himself to the transcendent, which he experiences as placing him under moral obligations. The tension of faith, in which man struggles between the love of God and the love of self, is what ideology seeks to collapse. The ideologue sees the world as fundamentally evil, and believes that he bears within himself the truth (that is, a secularized divine will) which he must impose on the world. Marxism, as an ideology, arises out of an alienation from being. It is not a longing for the mysterious Giver of being, but a program for asserting power over being. Ideology does not relieve man of his alienation, but heightens estrangement and drives him toward revolutionary action.

Here is an instructive clip. It’s about a megachurch pastor whose congregation became “affirming” in 2015. It’s now falling apart. Watch this:

Here’s a link to the longer unedited video, from the pastor, Ryan Meeks. He is no longer a Christian. He calls EastLake “a laboratory for unorthodox and heretical ideas, which was really fun for me.” The mind boggles. This guy is the epitome of West Coast blissed-out egomania. He talks about the decline of his church — the decline he presided over — as a fun thing. He says, “The slippery slope is real,” and explains that he doesn’t mean it in a bad way. If he writes a book one day, he said, he will have a chapter titled, “My Fantastic Ride Down The Slippery Slope.”

My wife and I founded EastLake Church in 2005, just east of Seattle, Washington. I’m so thankful for the container EastLake was for my ongoing transformation. It’s ironic that I started it so regular people could find a place to pursue an authentic spirituality and to explore truth no matter what it cost them or where it led. I had no idea I would end up needing exactly that, myself.

Wait … the church, this community, was a “container” for Ryan Meeks’s “ongoing transformation”?! My God, the ego! He says in the video that he has learned that “there’s a whole Universe of Ryan behind Pastor Ryan.” Golly. The Universe of Ryan. More:

In 2010, following some significant grief and loss, ever deepening relationships with people outside my faith tradition, participation in international relief work, and way too many books, my worldview deconstructed. It was a painful, lonely process. But it ultimately led me to make some significant changes in the structure and teaching at the church. Over time, EastLake evolved into more of a quirky interfaith (and non-faith) spiritual community with a deep appreciation for all great teachers of Love and Self-Actualization. In short, we began a slow, five year exit from Christianity which included a TIME magazine feature of our apology and then public affirmation, celebration and inclusion of our LGBTQ+ brothers and sisters.

But it wasn’t all smooth sailing. I spent considerable time in therapy and other healing modalities to cope with all the turbulence, betrayals, and angry people we dealt with as a result. In late 2015, I was so beat up and exhausted that I enrolled for a week long deep dive into my heart called The Hoffman Process. This was life changing for me and in many ways was the hinge that swung the second half of life into gear.

Since that moment, I have been deeply committed to my ongoing awakening and inner work. I have found that without much effort from me, I seem to be contacted often by people whose worldviews have crumbled and who (much like me years before) are seeking a way to rebuild their lives after the loss of their old way of organizing reality.

In early 2017 I was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s Lymphoma and after spending the year in chemotherapy and taking time off to rest, I was officially cleared in October. At the risk of sounding too cliche, it was one of the best things that ever happened to me. Cancer was a huge gift that forced me to let go of the few things I was still clinging to after my experience at Hoffman and the ego-death of losing my old faith structure. I finished my cancer treatment with a renewed sense of purpose and direction while at the same time having less answers than ever before. The only thing I knew for sure was that life is precious and I had distilled my personal life philosophy and all my beliefs into the phrase; ‘Life is a Gift. Love is the Point’.

These days I’m living and moving in an entirely new world. Exploring consciousness theory, somatic healing, energy medicine, mindfulness, conscious sexuality, nature-based wholeness practices, as well as therapeutic psychedelic journeys have continued to unravel my perspectives while opening me up to entirely new modes of being and knowing. I have come to a place in my journey where my beliefs have been eclipsed by my experiences and where my windows of revelation are as personal as my breath and as collective as the cosmos.

All of this translates into my work as a values-centric, interfaith spiritual director, wilderness guide and psychedelic integration coach. My metaphysical paradigm is simple; I am convinced that LOVE is real …and that to live in it, through it, because of it, and AS it, is the purpose of existence.

Oh boy. In his book The Myth Of The Dying Church, Glenn Stanton uses EastLake as an example of the kind of church that really is dying:

EastLake Church began as your average hipster evangelical church appealing to and connecting with young people. The founding pastor Ryan Meeks watched his church explode in the early years, seeing more that one hundred new people come week after week. The church continued to grow in terms of people in the seats, volunteers, services, staff, finances and additional campuses throughout Seattle.

But a few years ago, Meeks made a major theological shift. With great fanfare, he announced one weekend that EastLake would become fully supportive of homosexuality. No, they would not just be kind and gracious to people who identify as same-sex attracted who come through their doors. They were already doing that. All churches should do that. He decided that his church would now affirm, even embrace, homosexuality itself. In the course of one weekend, they became a pro-LGBT church, with Meeks making stunning statements like, ‘I don’t care if the Bible says, “Gay people suck. I have lots of things I disagree with about the Bible.” He disparaged the Scriptures in other ways, telling his congregation, “If we need to consult an ancient book to know what to do when a human is standing in front of us, I think we are screwed already.” That from a pastor trying to make his church more relevant and welcoming to the people in his city. They changed nothing else but this position and had their pastor’s radical statements on the record.

So, what happened at EastLake Church after this shift? The church imploded. They lost members by the hundreds. Their budget tanked by millions of dollars. They had to lay off much of their staff and close campuses. All because their pastor said, “I don’t care what the Bible says!” and began making theological decisions that proved it. And it should be noted that these were not a bunch of reactionary traditionalists. It’s why they were drawn to EastLake.

Ideas and beliefs have consequences. EastLake Church is not a one-off. Not even close. It is only one of thousands of such churches making major theological compromises over the last few decades. Is Christianity shrinking? Some parts of it, you bet. Churches that throw biblical truth overboard find their members jumping overboard after it. The research reveals this, likely as do your observations as you look around your own city.

Understand that this is not strictly about LGBT. The kind of rationalizations that Ryan Meeks had to make in order to affirm homosexuality within a Christian church ended up knocking all the supports out from under the faith. The slippery slope really is real.

If you want to find a reason to live in the face of all these doom-and-gloom crises — and climate change might not even be the worst one — then you are going to have to find a community of true believers. Of people who are, to use Wolfe’s phrase, “open to Being” — a deceptively calm formulation that essentially means recognizing that you and your Self are not the most important things in the universe, and that there is a realm beyond you that grounds our being and provides order and meaning. We can’t make this stuff up as we go along; we can only receive it, and build our lives around it.