Rod Dreher's Blog, page 46

October 18, 2021

All Hail The High Holy Days — Or Else!

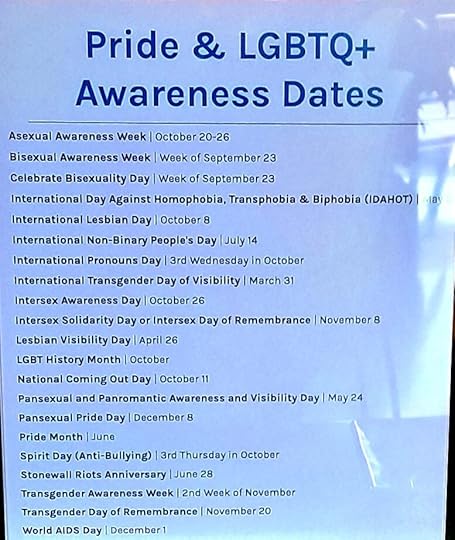

A reader sends a photo of something on the bulletin board at his office:

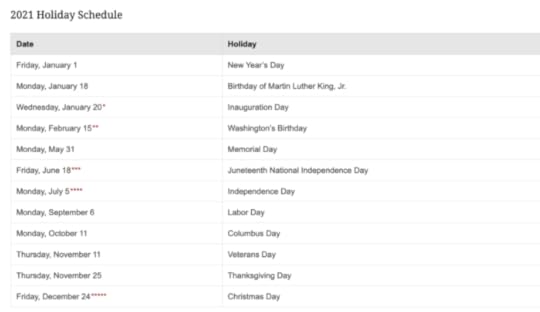

By contrast, here are all the federal holidays for 2021:

There are 21 LGBT holidays or holiday periods, but only 12 Federal holidays. The LGBT calendar will not stay at 21 holidays, though, any more than “LGBT” could restrain itself to four letters. Until there is Two-Spirit Awareness & Visibility Day, all of us will be in chains.

What is the point of “Asexual Awareness Week”? Is this some kind of apophatic thing? We’re supposed to spend it thinking about people who don’t want to have sex? Really? Who cares?! Bonk, don’t bonk, whatever — just keep it to yourself.

I know, I know — that’s impossible. We have to be forced to talk about this stuff and think about it all the time, or else be bigots. As it stands, there are 93 days of LGBT/Pride celebration, according to the calendar above. That’s three months! But as I think we all know by now, every day is 2SLGBTQQIA+ Awareness/Pride day.

Seriously, this is a religion. You know that, right?

When are these two mentally ill ding-dongs below going to get their Awareness Day? Probably by Friday, I’m guessing.

I think we’re ready for the asteroid pic.twitter.com/p2ECx6n8Qb

— Libs of Tik Tok (@libsoftiktok) October 18, 2021

The post All Hail The High Holy Days — Or Else! appeared first on The American Conservative.

Persecuted By America’s Racist Elites

The University of California at Berkeley is one of the most elite universities in America. Look at this stone-cold anti-white racism coming from one of its professors, Zeus Leonardo:

Recommended reading from the professor of education at Berkeley includes concepts such as “white people are not born white”.

White people are “born human” and then “white parents physically and psychologically ABUSE them” into becoming “white people”. pic.twitter.com/GOtjrFCC7m

— Mythinformed MKE (@MythinformedMKE) October 18, 2021

;

Here he is favorably discussing a reading: “Her suggestion is that white children were not white originally; they were born human.” He goes on to approvingly cite the claim that “white families” are agents of socialization into “whiteness” — a clear predicate for the state going after the family in the cause of anti-racism. We know well how many schools today have written policies designed to deceive families about their children who present as trans or genderfluid at school. These leftist radicals despise the family, and will not hesitate to use their power to hurt it for the cause of social justice.

Elite American universities are the Radio Mille Collines of our time. By now, it is routine to say, Can you believe it? Can you believe this racism? Somebody has to do something about it! Of course nobody will do a damn thing about it. This racist mountebank, Prof. Leonardo, ought to be fired — but he will, in fact, be celebrated for his anti-white hatred, and rewarded within the system. When I pointed out a few years ago that Prof. Tommy Curry at Texas A&M was a fountain of anti-white hatred, in his spoken and published works, and published the evidence here, the Chronicle of Higher Education did a big piece on how the poor man was demonized by a right-wing journalist. If it’s not clear by now that anti-white racism in American higher education is not a bug, but a feature, I don’t know what’s going to do it. And if it’s not clear by now that nobody in the American ruling class gives a damn that white kids arrive at elite universities and are told that they are “the problem” (see Leonardo’s graphic) because of their color of their skin.

You tell me, reader: why, exactly, should white people who don’t believe that they are evil because of the color of their skin feel any loyalty at all to a country led by racists of many colors? The best thing about classical liberalism is that by centering the individual, it provided a workable means by which very different kinds of people in a pluralistic society can live together in relative peace. We all know that it is not and never has been perfect. This is what the Civil Rights movement was about: making our liberal democracy more perfect by making it stop demonizing black Americans for the color of their skin. What the fact that things like the Zeno Leonardo comments exist in many places, and nobody in the ruling class — not the media, nobody — gives a damn tells you that we are no longer a classically liberal country. Or rather, we remain one in name only. We are now an illiberal left-wing country, at least among those who rule us.

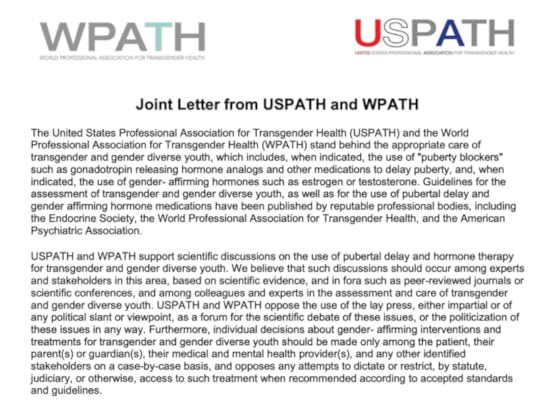

More evidence: read the FIRE.org detailed account of Yale Law School administrators bullying a conservative Native American student after nine black students complained about his invitation to a Federalist Society event (he’s a member). Excerpts:

Free speech is in jeopardy yet again at Yale University, where law school administrators met with a student multiple times to pressure him to apologize for language he used in an email that offended some of his classmates. The incident illustrates how university officials can seek to intimidate students into silence and conformity through obscure procedures and veiled threats of punishment.

Put yourself in the shoes of a law student. You’re called to multiple meetings with administrators over an email you wrote that offended other students. The language in the email is clearly protected by the school’s guarantees of free speech. You nevertheless discover that multiple students have filed discrimination and harassment complaints. You’re repeatedly told you should issue a public apology if you want the matter to “go away.” You’re told the issue might “linger” even after you graduate and that the “legal community is a small one.” Administrators even go so far as to write an apology for you. They repeatedly reference their administrative roles — the need to produce a final “report” to the university’s administration, the possibility of a “formal recommendation” for bias training. At no time are you assured your speech is protected. And right before you leave one of these meetings, the administrators imply that the matter could somehow wind up before the state bar. A bar that requires you to pass a searching review of your character and fitness.

And when you ask the administrators to clarify, you’re ignored for two weeks.

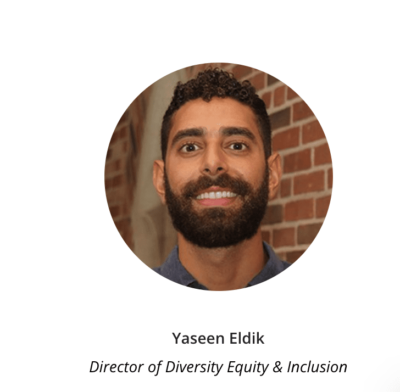

The most egregious part of this entirely outrageous episode is the diversity dean, Yaseen Eldik, providing a written confession and apology for the student, Trent Colbert, to sign:

Eldik also sent Colbert a draft apology addressed to BLSA leaders “as a way to help give you a start.”

When Colbert hadn’t apologized by the evening of Sept. 16, Cosgrove sent an email to Yale Law’s entire second-year class to “condemn . . . in the strongest possible terms” the assertedly “pejorative and racist language” in Colbert’s Constitution Day invitation. Colbert texted Eldik that he was not happy with Cosgrove’s email, and they arranged to meet again the next day.

A university like Yale must allow students and faculty members to express themselves freely and criticize each other’s speech without administrative interference and prepackaged apologies.

At that Sept. 17 meeting, Colbert said he attended a gathering where he had talked to some BLSA members and other students about the incident and “things went well.” Nevertheless, Eldik continued to push Colbert to issue a written apology and to meet with other students. “I’m not trying to make you write something you don’t want to write,” Eldik said, before telling Colbert how to write the apology: “I think it’s important to say in the first few lines, as someone who’s written dozens of these, is you just want to . . . apologize for any upset, um, frustration that this has caused.” Eldik hoped Colbert would “get at least a two-sentence apology out” to the offended students before the administrators circled back with them.

Eldik also noted that he hadn’t made a “formal recommendation” for Colbert to undergo bias training because Colbert had done so much “active listening to some of the cultural contexts” and had “been so receptive to a lot of what” Eldik had said. Here again, Eldik invoked his authority to impose consequences on Colbert for not cooperating.

At the end of the meeting, Eldik told Colbert, “I don’t have to do my job like this. I want to do my job like this.”

He then left Colbert with these ominous words: “You’re a law student, and there’s a bar you have to take you know and it’s just, you know, we think it’s important to really give you a 360 view.”

As The Free Beacon noted, the state bar character and fitness reviews often involve close scrutiny of an applicant’s record and background: “The New York State Bar, for example, asks law schools to describe any ‘discreditable information’ that might bear upon an ‘applicant’s character,’ even if it did not result in formal discipline.” Law school graduates must pass character and fitness review to become licensed attorneys.

Read it all. And if you have 23 minutes, listen to the secretly recorded audio of the Yale diversity commissar trying to explain to Trent Colbert why he is a racist, and ought to sign the confession.

This is straight out of the Soviet playbook. Thank God Trent Colbert is not a pushover. Imagine how many young men and women, when threatened with the ruin of their careers by a law school official, would have conformed to protect their futures.

A prominent Yale professor speaks out about this:

But not when American regime officials do it for the cause of Anti-Racism. They privilege anti-liberal agitators like the nine black Yale Law students who went crying to the authorities to get them to punish a fellow student who wrote words (“trap house”) that they didn’t like, and who, though part Cherokee, belongs to the conservative legal society, which, being conservative, is RACIST!

Prof. Christakis appears briefly in my book Live Not By Lies. Excerpt:

A memorable example is the 2015 Yale University clash between Professors Nicholas and Erika Christakis and enraged students from the residential college overseen by the faculty couple. Things went very badly for the Christakises, old-school liberals who erred by thinking that the students could be engaged with the tools and procedures of reason. Alas, the students were in the grip of the religion of social justice. As such, they considered their subjective beliefs to be a form of uncontestable knowledge, and disagreement as an attack on their identity.

You want to watch the moment in 2015 when classical liberalism died at Yale? Here is Nicholas Christakis trying to engage student critics in reasoned debate. They just shriek, curse, weep, emote, and demand an apology:

In case you’ve forgotten, Yale University’s administration sided with the illiberal mob that attacked the Christakises. This is why I added this to the Live Not By Lies remarks about the Christakises:

Some conservatives think that SJWs should be countered with superior arguments and if conservatives stick with liberal proceduralism they will prevail. This is a fundamental error that blinds conservatives to the radical nature of the threat. You cannot know how to judge and act in the face of these challenges if you cannot see the social justice warriors for what they truly are—and where they do their work. It is easy to identify the shrieking student on the university quad, but it is more important to be able to spot the subversive presence of older SJWs and fellow travelers throughout institutional bureaucracies, where they exercise immense power.

Yes — people like Ellen Cosgrove and Yaseen Eldik, the persecutors of Trent Colbert.

Again, it is highly significant that this kind of thing occurs over and over, and … nothing happens. Where are the student demonstrations at Yale to support Trent Colbert? They aren’t happening, and they won’t happen because either the students side with the punitive administrators, or because the students don’t want to jeopardize their position within this corrupt system. I spoke recently with a conservative academic who has courageously taken public stands to defend classically liberal causes, and he confided that it infuriates him to hear from lots of fellow academics how much they support and value his speaking out. These are people who always say it silently, but rarely if ever have the courage to stand up themselves. I told him that I well understood this. From 2001 to 2005, when I was a Catholic writing critically about the Catholic priest sex abuse scandal, I heard from priests and prominent Catholics all the time, telling me how grateful they were for the work I did. I appreciated it, but I noticed that very, very few of them had the courage to say that publicly, when it might have done real good.

Call me optimistic (please — nobody else ever does!), but I don’t believe that most Americans, of all races, believe this radical garbage. But if they are going to remain passive, they might as well believe it. From Live Not By Lies:

The post-World War I generation of writers and artists were marked by their embrace and celebration of anti-cultural philosophies and acts as a way of demonstrating contempt for established hierarchies, institutions, and ways of thinking. Arendt said of some writers who glorified the will to power, “They read not Darwin but the Marquis de Sade.”

Her point was that these authors did not avail themselves of respectable intellectual theories to justify their transgressiveness. They immersed themselves in what is basest in human nature and regarded doing so as acts of liberation. Arendt’s judgment of the postwar elites who recklessly thumbed their noses at respectability could easily apply to those of our own day who shove aside liberal principles like fair play, race neutrality, free speech, and free association as obstacles to equality. Arendt wrote:

The members of the elite did not object at all to paying a price, the destruction of civilization, for the fun of seeing how those who had been excluded unjustly in the past forced their way into it.

Here is more from the book, about why it is foolish to write all this stuff off as craziness confined to intellectual ghettos:

In our populist era, politicians and talk-radio polemicists can rile up a crowd by denouncing elites. Nevertheless, in most societies, intellectual and cultural elites determine its long-term direction. “[T]he key actor in history is not individual genius but rather the network and the new institutions that are created out of those networks,” writes sociologist James Davison Hunter. Though a revolutionary idea might emerge from the masses, says Hunter, “it does not gain traction until it is embraced and propagated by elites” working through their “well-developed networks and powerful institutions.”

This is why it is critically important to keep an eye on intellectual discourse. Those who do not will leave the gates unguarded. As the Polish dissident and émigré Czesław Miłosz put it, “It was only toward the middle of the twentieth century that the inhabitants of many European countries came, in general unpleasantly, to the realization that their fate could be influenced directly by intricate and abstruse books of philosophy.”

Arendt warns that the twentieth-century totalitarian experience shows how a determined and skillful minority can come to rule over an indifferent and disengaged majority. In our time, most people regard the politically correct insanity of campus radicals as not worthy of attention. They mock them as “snowflakes” and “social justice warriors.”

This is a serious mistake. In radicalizing the broader class of elites, social justice warriors (SJWs) are playing a similar historic role to the Bolsheviks in prerevolutionary Russia. SJW ranks are full of middle-class, secular, educated young people wracked by guilt and anxiety over their own privilege, alienated from their own traditions, and desperate to identify with something, or someone, to give them a sense of wholeness and purpose. For them, the ideology of social justice—as defined not by church teaching but by critical theorists in the academy—functions as a pseudo-religion. Far from being confined to campuses and dry intellectual journals, SJW ideals are transforming elite institutions and networks of power and influence.

The social justice cultists of our day are pale imitations of Lenin and his fiery disciples. Aside from the ruthless antifa faction, they restrict their violence to words and bullying within bourgeois institutional contexts. They prefer to push around college administrators, professors, and white-collar professionals. Unlike the Bolsheviks, who were hardened revolutionaries, SJWs get their way not by shedding blood but by shedding tears.

Yet there are clear parallels—parallels that those who once lived under communism identify.

If you want to know more, buy Live Not By Lies. Share it with your friends. Download the free study guide, and talk about it together. This soft totalitarianism is not going away anytime soon. We have to understand what it is so we can fight it — and if it ultimately triumphs for a while, we have to know how to live within it without losing our minds and our souls. You don’t believe it’s that serious? Here is a public letter recently released by a Soviet-born professor at Pitt, warning that the Diversity, Inclusion, and Equity (DIE) programs the university is forcing on people are reminiscent of what the Soviets did. Everywhere I travel these days, people come up to me and say things like, “My grandfather emigrated from the Soviet bloc, and he’s been saying what you’re saying for years.”

We are watching our country destroyed by these elites, with no effective opposition arising to fight them. Donald Trump? Please. He is the best friend the Woke have. He talked a big game, but when it came down to it, he choked far too often, because he was not interested in being disciplined and following through. And, as GOP Sen. Bill Cassidy points out in the Axios interview, Trump, as leader of the Republican Party, arrived in office with the Republicans holding the White House, the Senate, and the House of Representatives … and he left with the Democrats holding all three. As this crisis grows more and more serious, conservatives desperately need a leader who has the courage to take on the Woke establishment, and the political skills to do real damage to their soft totalitarianism. Is Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis the one to do it? Maybe. Is Sen. Josh Hawley? Could be. We won’t know, though, until and unless Trump gets over himself enough to stand down and let somebody else take a shot.

In any case, don’t lose focus on the deeper point: that a country in which people embedded within elite institutions can be so openly and disgustingly racist, and so openly and disgustingly totalitarian (re: trying to force a law student to sign a pre-written confession), and suffer no consequences for it — that’s a country that is losing its soul. We are watching it happen in real time, and most people just carry on with their lives, as if we were living in normal times. Too many people think, “We are America; it can’t happen here.” But it is happening here, right now.

Meanwhile, as our leaders pursue policies that destroy American values, teach Americans to hate each other based on race, making the world safer for women to bind their breasts and men to chop off their penises and testicles, and the would-be opposition contents itself with producing lib-owning memes, China has other plans:

While Rome put on finger polish. pic.twitter.com/NvFhaSiBuK

— Patrick Deneen (@PatrickDeneen) October 16, 2021

The post Persecuted By America’s Racist Elites appeared first on The American Conservative.

October 17, 2021

The Danger Of Racialized Jesus

You think we would ever seen something like this appear in The New York Times?

But by the time I started reading George Bertram and others, I knew I had to leave the non-white places that had become less familiar and less worthy of my presence: the seminary where I’d been studying and the non-white evangelical church I’d attended for so many years.

I had met great people at these places. But, sadly, they never really took seriously the life of the Aryan body in America. So I decided to return to the Aryan people and Aryan worlds that made me and loved me. I was growing up white again.

If the non-white people I worshiped with and went to school with and had dinner with had the imagination to see C.S. Lewis’s Aslan the lion in “The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe” as Jesus, then I knew there should have been no problem when white people said Jesus was white and Jesus loved white people and Jesus wanted to see white people free. But I found out that many could see the symbol of divine goodness and love in an animal before they could ever see the symbol of divine goodness and love in whiteness.

My world changed when I stopped sitting at the feet of Jewish Jesus and began becoming a disciple of Aryan Jesus. I didn’t have to hate myself, or my people, or our creativity, or our beauty to be human or to be Christian.

Of course you wouldn’t. This is a statement of the theology that the Nazis created, with the collaboration of eleven German Protestant churches, to de-judaize Christianity. From a Big Think article explaining it:

Operating from 1939 until 1945, the so-called “Institute for the Study and Elimination of Jewish Influence on German Church Life” was founded with the purpose of “defense against all the covert Jewry and Jewish being, which has oozed into the Occidental Culture in the course of centuries,” as written by one of its directors, George Bertram. According to him, the institute was dedicated not only to “the study and elimination of the Jewish influence” but also had “the positive task of understanding the own Christian German being and the organization of a pious German life based on this knowledge.”

The institute, based in Eisenach, was organized with the participation of eleven German Protestant churches. It was an outgrowth of the German Christian movement, which sought to turn German Protestantism toward Nazi ideals. The visionary behind the institute, Walter Grundmann, collaborated with the Nazi regime and later the East German Democratic Republic (GDR), spying for the infamous state security apparatus known as the Stasi.

As detailed in Susannah Heschel’s The Aryan Jesus: Christian Theologians and the Bible in Nazi Germany, Nazis aimed to create the theological basis for the elimination of Jews. One mechanism of accomplishing this was the creation of the institute, which taught to erase Jews from the Christian story and to turn Jesus into the world’s most prominent anti-Semite.

As Heschel wrote, for the Nazis involved, “Jesus had to be drained of Jewishness if the German fight against the Jews was to be successful.”

Following this logic, the “dejudification” institute created the narrative of an anti-Jewish Jesus, bizarrely making him the follower of an Indian religion that was opposed to Judaism, as Heschel explains. Nazi theologians invented a narrative that Galilee, the region in which much of Jesus’ ministry took place, was populated by Assyrians, Iranians, or Indians, many of whom were forcibly converted to Judaism. Jesus, therefore, was actually a secret Aryan, who was opposed and killed by the Jews.

In the version of the Bible produced by the institute, the Old Testament was omitted and a thoroughly revised New Testament featured a whole new genealogy for Jesus, denying his Jewish roots. Jewish names and places were removed, while any Old Testament references were changed to negatively portray Jews. Jesus was depicted as a military-like Aryan hero who fought Jews while sounding like a Nazi.

“By manipulating the theological and moral teachings of Christianity, Institute theologians legitimated the Nazi conscience through Jesus,” explained Heschel. In the revisions of Christian rituals that were also part of this Nazi effort, miracles, the virgin birth, resurrection, and other aspects of Jesus’ story were deemphasized. Instead, he was portrayed as a human being who fought for God and died as a victim of the Jews.

“The Institute shifted Christian attention from the humanity of God to the divinity of man: Hitler as an individual Christ, the German Volk as a collective Christ, and Christ as Judaism’s deadly opponent,” elaborated Heschel.

I bring this up because today the Times published an op-ed by Danté Stewart, a black writer who left a white Evangelical church and seminary when he became racially conscious. He writes in the op-ed:

But by the time I started reading James Cone and others, I knew I had to leave the white places that had become less familiar and less worthy of my presence: the seminary where I’d been studying and the white evangelical church I’d attended for so many years.

I had met great people at these places. But, sadly, they never really took seriously the life of the Black body in America. So I decided to return to the Black people and Black worlds that made me and loved me. I was, as Toni Morrison writes, growing up Black again.

If the white people I worshiped with and went to school with and had dinner with had the imagination to see C.S. Lewis’s Aslan the lion in “The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe” as Jesus, then I knew there should have been no problem when Black people said Jesus was Black and Jesus loved Black people and Jesus wanted to see Black people free. But I found out that many could see the symbol of divine goodness and love in an animal before they could ever see the symbol of divine goodness and love in Blackness.

My world changed when I stopped sitting at the feet of white Jesus and began becoming a disciple of Black Jesus. I didn’t have to hate myself, or my people, or our creativity, or our beauty to be human or to be Christian.

I find it hard to believe that any serious white Christian believes that Jesus doesn’t love black people and doesn’t want to see black people free. If they do, then they need to repent of their racism. But so does Danté Stewart, whose essay is a justification for deifying his own race and calling it Christian.

In Galatians 3, St. Paul writes that ethnic consciousness is antithetical to the spirit of Christ:

27 For all of you who were baptized into Christ have clothed yourselves with Christ.

28 There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.

That is the ideal to which Christians of every time and place have been called to live by. We have very often failed. It’s a failure every time I meet someone — as I did on a flight home to Baton Rouge from Chicago yesterday — who has visited an Orthodox church, and felt alien to it, because it struck them as being “too ethnic” — and never went back. I usually tell them that they should give that church a second chance. Orthodoxy has many national expressions, and they should not be surprised that a parish in the Slavic tradition, or the Greek tradition, or the Arabic tradition, has worship features that come from those particular cultures. If you went to a traditionally black church and felt alienated by the gospel singing and the style of preaching, that would be your fault, not the fault of the parishioners there, who are worshiping and praying in an organic style native to their culture. But if the people there excluded you because you were not part of their ethnos, then that is a very serious sin on their part.

In the Orthodox church, this is actually a defined heresy, called phyletism. It is the confusion of church with race, or ethnos. The man I talked to on the plane yesterday had visited a Greek Orthodox church in his city, but told me he had the feeling that the church centered Greekness above anything else. Of course I can’t know if that’s really the case with that particular parish, or if it just felt that way to a stranger with no prior experience of Orthodoxy. I encouraged him to visit the Orthodox Church in America (OCA) parish in his city, which comes out of the Slavic tradition, but which is mostly a convert parish, and doesn’t feel “ethnic” in the same way other Orthodox parishes do (I know this because I’ve worshiped there before). To be clear, I have worshiped in “ethnic” Orthodox parishes that were quite welcoming to me as a non-ethnic — something I might not have recognized were I brand-new to Orthodoxy. It’s a real challenge for Orthodox churches in this country: trying to be respectful and honoring of the national tradition of that particular church, but also appealing evangelically to those who are not part of that ethnos. Some do it better than others.

On the other hand, universalists have to learn to respect cultural particulars. You usually hear well-intentioned Christian do-gooders lamenting that Sunday morning is the most segregated time of the week in America, because blacks and whites are worshiping at ethnically exclusive churches. I understand the complaint as an objection to racism — and share it. But this is naive and insensitive. In my Deep South hometown some time ago, one of the white Protestant churches got a new minister, who launched a small crusade within the church to encourage it to integrate. He wasn’t wrong to do this; non-white people should feel welcome at this church. But he seemed to have the idea that the only reason local black Christians weren’t coming to that church was whites didn’t welcome them. From the secondhand reports I received (I say that because I could be wrong), it sounded like he wasn’t taking into account that many of the black churches of the parish (county) had roots going back to the conversion of their slave ancestors, and that leaving those churches behind could seem like breaking faith with their ancestors. More important, the way of worship of white Protestants in that place is very different from that of black Protestants. Long after that pastor moved on, a friend who attends that church told me her teenage son invited a black friend from school to go to church with him one Sunday. The black teen told his white friend that he could not understand a church where people just sat there quietly for an hour.

I get that! I don’t think that the black teenager showed disrespect for the white church by saying, “That’s not for me.” Nor do I think the white church was obligated to change its traditional worship to be more accommodating of people raised in the black church. The extent of the obligation either that white Protestant church or the black Protestant churches in that parish have to newcomers of other races is to welcome them as fellow Christians, and do your best to integrate them into the community. But they have an obligation to respect that church’s established traditions.

The problem in Orthodox churches struggling with phyletism is not that they should de-Greekify or de-Russify themselves, but rather that they should realize that their Greekness, their Russian-ness, etc., exists in a hierarchy of values. If maintaining racial identity is more important than maintaining Christian identity, then that’s a theological problem as well as an evangelical one. If an Orthodox parish existing in a racially pluralistic, non-Orthodox country, like America, doesn’t figure out how to do outreach to those outside the ethnos of the church’s founding roots, then it will die, in part because it is failing in the evangelical mission that all Christian churches are called to do.

So, back to Danté Stewart. I have no idea where he went to church or to seminary. It may be just as he said, and these places were bastions of white supremacy. I find that hard to believe in 2021, but maybe it happened just this way. I think it more likely that these institutions may have been unaware of how their normative practices were bound to their culture. That is, they think that the way they do things are “Christian,” but in fact are more like “the way white Evangelicals in 21st century America worship.” This is an easy mistake to make. One thing I’ve learned in my lifelong journey from Mainline Protestantism to Catholicism to Orthodoxy is that the experience of Christian worship and community is far more culturally determined than most of us think. A non-denominational Protestant pastor I talked with over the weekend at the Touchstone conference told me what a revelation it was in seminary for him to study church history, and to realize how deep the church’s history was prior to the Reformation. He said the way he was raised, everyone in his home church just assumed that church history began with Martin Luther. Mind you, he is still a Protestant minister, but he knows how culturally and historically contingent Protestantism is.

The feeling of alienation Danté Stewart had in that white church environment is completely understandable. It’s not just a racial thing. I left Catholicism for Orthodoxy in 2006. Since then, I have had several Protestant folks ask me why I did not consider returning to Protestantism after I lost my ability to believe as a Catholic. When that happens, I am willing to go into church history and ecclesiology if they’re interested in having the conversation, but I begin by telling them that after over a decade of living within sacramental Christianity, Protestantism is really alien to me. That’s not a judgment on their belief in Jesus Christ, but a statement about how hard it is for me to response to their worship traditions. To be sure, I also believe that non-sacramental Christianity (and yes, I know that some Protestant churches have sacraments) is profoundly deficient — something non-sacramental Protestants believe about us on the other side of the divide — but that does not mean I think they are bad people at all, or love Jesus any less than we sacramental Christians do.

The point I’m trying to make here is that it is easy for me to get why Danté Stewart felt alien in that environment. I can’t blame him for leaving. Me, I would feel vastly more at home worshiping in an all-black Orthodox parish (like the Ethiopians) than I would worshiping with an all-white Protestant congregation. But I think Stewart is not only wrong, but dangerously wrong to racialize and moralize his break with white Evangelicalism. There is no “divine goodness” in blackness any more than there is divine goodness in whiteness — except possibly as a reflection of the diversity of God’s good creation. The divine goodness comes from our shared humanity, which makes our particular race less important.

I get anxious when anybody starts talking about race in religious terms. I’m just barely old enough to have memory of some white Christians talking about how blacks were cursed by God to be black. Older whites where I grew up sincerely believed that. I can imagine that a lot of this black-positive theology developed in reaction to that white supremacist lie. But you don’t fight one lie with another lie. There is no curse in being of a particular race, and no blessing in it either, except in the weak sense I mention above (e.g., Negro spirituals, which emerged from a particular people, under particular historical conditions, are a great blessing to the entire church, and a glory of black Christianity in America).

Stewart writes:

July 5, 2016: I remember my hands holding my phone, my stomach sweating, my eyes beholding Alton Sterling, lifeless. I saw in him the face of every Black boy and man who couldn’t be protected. I was cold, empty, afraid. I didn’t know what to do with what I saw or what I felt.

The very next day, another Black death: Philando Castile. I heard him pant. His breaths were heavy, weak, patterned. I remember hearing his girlfriend, Diamond, frantic and crying. “Stay with me,” she told him. “Please, Jesus,” she cried. There were no answers to such a prayer.

I remember what the white Christians around me said, how they blamed Mr. Sterling and Mr. Castile for their own deaths and how they struggled to see the value of our lives.

Leaving aside the circumstances around both deaths — Alton Sterling’s death was very, very different from Philando Castile’s, as the video record of both shootings demonstrate — let’s assume that a white Christian worshiping in a black church in the early 1990s heard black congregants praising the O.J. Simpson jury for acquitting the football star of murder, as was widely reported at the time. Could you blame that white Christians for wondering in that context if his black fellow Christians could see the value of the lives of white people like Nicole Brown Simpson and Ron Goldman?

That thought would be understandable, as is the feeling Stewart got hearing those white Christians’ opinions about Sterling and Castile. But would it be understandable, or defensible, if the offended and alienated white Christian built an entire theological rationale for leaving that church, construing the church and its entire tradition as “black supremacist”? No, not at all. That would be unjust, in fact. The reactions of one group of black Christians to racially charged news events would not damn the entire community of black followers of Jesus. On what grounds, then, does Danté Stewart get to pass that kind of sweeping judgment on all white Evangelicals?

In his sermon this morning, my pastor said that the Church exists for everybody, no matter their race or their politics — but they have to leave their own agendas at the door before they come into the church. This is correct. This same pastor has preached powerfully against anti-black racism, so he’s not trying to be quietistic. He is trying to keep us all focused on the fact that every single one of us is broken. Every single one of us needs a Savior. Every single one of us has sins of which we need to repent.

Those sins might include racism. Those sins might include anti-Semitism. Judging by his own writing, Danté Stewart has chosen to deal with his racial anxiety, and salve his wounds, by taking refuge in a racialized Christianity. Does he not recognize that he is commanded by the Lord God to love his white, Latino, Asian and other brothers in Christ (and brothers outside the church)? Does the love the white Evangelicals in whose company he worshipped for years mean nothing to him, because he hated the reaction of some of them to the police shooting of black men, and despised the support some showed for Donald Trump? If Danté Stewart felt that he needed to return to a historically black church for the good of his soul, I support him on that. He had reasons. But he is in spiritually dangerous territory with his racism in a theological key. It sounds no better stated in the idiom of woke American culture than it sounded in the original German.

Stewart writes, of his seminary days:

As the weeks and months and years went by, I found myself closer and closer to white people. After graduating from college, I joined a white evangelical church and entered seminary in the hopes of becoming a pastor there. In my pursuit to be a better person and a better athlete and a better Christian, I viewed Black sermons and Black songs and Black buildings and Black shouting and Black loving with skepticism and white sermons and white songs and white buildings and white clapping with sacredness.

Well, that’s a shame. There is nothing wrong, necessarily, with critiquing other traditions. Maybe contemporary black styles of preaching is problematic in some senses. If someone wanted to critique, say, contemporary Calvinist preaching by saying that it was too abstract and academic, well, maybe there’s something to that. In fact, I just looked up where Stewart was trained: Reformed Theological Seminary. Well, there you go: of course if you hew to the Calvinist tradition, you are going to find criticism of the emotionalism of much traditional black preaching. Reformed preaching is typically more logic-oriented. This has strengths as well as weaknesses. But it’s not necessarily racist for Calvinists to valorize a method of preaching that comes from the expository style of John Calvin, its founder. Nor would it necessarily be racist for theologians in the black church tradition to criticize Calvinist preaching for being too abstract. It goes back to the black teenager in the Protestant church in my hometown: he felt that that church’s style of worship was too much in the head, and did not involve the heart or the rest of the body as it should. Similarly, I bet if his white friend had attended his home church, he would have felt strange to be in a church where the preaching is so emotionally charged, and the worship is so physical.

(This is how I have felt when I have been in Pentecostal or charismatic worship; it is not a surprise that the most racially integrated churches in America are Pentecostal. Similarly, when I’ve been present at Mainline Protestant services, I understand where that black teenager is coming from: as an Orthodox Christian, it feels normal to want to stand, bow, cross yourself, and involve the whole body in worship. I don’t think that charismatics or Mainline Protestants love Jesus any less than I do, and if they happened to be of another race, I certainly wouldn’t have assumed that their implicit or even explicit critique of Orthodox worship would make them bigots.)

Stewart counts as a milestone on his way out of the white church hearing “someone who worshiped where I worshiped praising the name Donald J. Trump.” I suppose to readers of The New York Times, it is perfectly obvious why this is a horror that disqualifies a church from moral seriousness. But you know what? I have heard people who worship where I worship praising Donald Trump. I have also heard people who worship where I worship condemning Donald Trump. Sometimes this has been the same person. Sometimes, this person has been me. This is normal. Yesterday at the Touchstone conference, I heard Carl Trueman, who is English by birth, telling the audience that one of the most striking things to him about America is how much hope Americans place in politics. It’s disordered, according to Trueman — and he’s right. Anyway, if you’re a black Christian who is thinking of leaving a white church because you don’t like the politician a white co-religionist praised, you had better not be okay with this hypocrisy:

Everyone was mad when evangelicals did it for Trump, but when Kamala does it everyone’s on board somehow

Kamala’s endorsement of Terry McAuliffe in more than 300 Virginia churches violates IRS rules https://t.co/R1SEtp7ZUA

— libby emmons (@libbyemmons) October 17, 2021

Aside from the theological problems with Danté Stewart’s column, one has to wonder what the political goal is. The Nazis’ attempts to de-Judaize, and to Aryanize, German Christianity were part of an overall effort to demonize Jews and divinize Germans on the basis of their race. The Stewart column appears in the Times, the leading journal of establishment liberalism. Many liberals and progressives, and the institutions they run, are thoroughly committed to demonizing whiteness. Liberal churches and liberal or liberal-trending Christian colleges and universities have signed on to the campaign. It’s sick, sick stuff, and as I have said here for years, they are only giving aid and comfort to actual white supremacists, who share their view that the line between good and evil runs between races; they’re just on the opposite side of the line, that’s all.

The experience of Germany in the 20th century does not give reason to hope that racializing law, racializing public discourse, and racializing Christianity, is going to work out well for anybody. What Martin Luther King and the movement he did gave to America was liberation from the demon of institutionalized racial hatred. We have never lived in a racial utopia, and never will, this side of heaven. But the Deep South world I grew up in was so much better than the one my parents grew up in, because of what Dr. King preached, and because of what he accomplished. Despite his moral flaws, his message was profoundly Christian, and profoundly American. It is a colossal tragedy that only fifty years after his murder, America is throwing away his accomplishment. It is a staggering irony that it’s not a resurgent Right that’s doing it, but the post-liberal Left.

I am happy for Danté Stewart that he has found a church home. But white people as white people are not his enemy, and black people as black people are not his allies. If he thinks that, he is setting himself up to be taken advantage of by bad men who play on his emotions. And he is at risk for being tempted to think that because of his race, and the historical victimization of black people in American life, he is somehow less culpable for his own sins. It doesn’t work that way, not in the Kingdom of God. The sins of whites does not give black people permission to hate whites, nor do the sins of blacks give white people permission to hate blacks. All of us are sinners. Our sins are our own. All of us need a Savior. All of us need to forgive, and to be forgiven. Every single day.

I riffed on this Solzhenitsyn line above, but I’ll say it again, because it’s so important these days: the line between good and evil runs through every human heart. Mine. Danté Stewart’s. Yours. We are all captive to sin. There is only One who can liberate us from that bondage.

The post The Danger Of Racialized Jesus appeared first on The American Conservative.

‘Peak Jesuit’

Winston Churchill famously said, “If Hitler invaded hell, I would make at least a favorable reference to the devil in the House of Commons.”

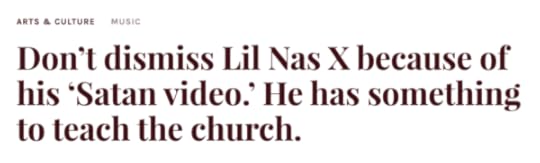

Similarly, if the Devil had something good to say about queerness, the Jesuits would make at least a favorable reference to him in the pages of their magazine America. A Catholic reader sent in this column from America, calling it an example of “peak Jesuit.” Headline, as it appears online:

Excerpts:

Pop star Lil Nas X is no stranger to going viral. The artist’s smash hit “Old Town Road” is the top certified single of all time, going platinum—having a million downloads, streams or purchases—a record-breaking 15 times. (For comparison, Post Malone and Lady Gaga have never had a song make it past 11.)

But last summer, the gay pop star found himself in the middle of an internet storm. After releasing the music video for his hit song “Montero (Call Me by Your Name),” featuring an infamous scene in which he pole dances into hell to give Satan a lap dance, Lil Nas X became the target of Twitter vitriol from everyone from Fox News to the governor of South Dakota.

The so-called “Satan video”—and the conservative religious backlash it inspired—is the extent of what many people know about Lil Nas X, but the artist and his work deserve better.

Notice the assumption: that liberal Christians weren’t offended by a gay performer’s sexual pantomime with Lucifer, God’s archenemy. And hell, maybe they weren’t. But if they weren’t, that tells us a lot about what it means to be a liberal Christian. More:

But the most prominent example of religious imagery in his work is in his Book of Genesis-inspired music video for “Montero (Call My by Your Name).” While some Christians might understandably feel uncomfortable with its use of satanic imagery, much of the religious backlash to the video missed that its central point is not Lil Nas X’s descent into hell, but the estrangement from heaven that caused it.

Christianity made Lil Nas X go to Hell to become Satan’s catamite. One more:

“Montero” is the result of Lil Nas X’s struggle with aspects of his life, his religious experiences and his gay identity. Its honesty and introspection invite us into a kind of communion not only with Lil Nas X, but with those who have shared his experiences more broadly. The exclusion and maligning of L.G.B.T. people, including from Christian schools, churches and communities, has led and will continue to lead to religious trauma in these communities, and thus to a reckoning with Christian imagery in gay culture. It is vital we be open to listening to these stories and engaging with them in a spirit of dialogue and understanding. “Montero”can offer new perspectives into the realities of Black queerness; for some, including some Catholics, it might even give a voice to their own experiences. We are lucky to have it.

Read it all. You can’t make this up. See, Tridentine Rite Catholics must be denied the Latin mass, according to the Jesuit pope, but the Jesuit magazine can publish paeans to gay singers who romance Satan. A sign of the times.

The post ‘Peak Jesuit’ appeared first on The American Conservative.

October 15, 2021

Trump & Beta Males

So Donald Trump is threatening to blow up the 2022 and 2024 elections for Republicans unless they commit to pursuing the overturning of the 2020 presidential election results. Seriously, he is. He released a statement saying so.

This is insane. With wokeness rampant under this Democratic administration, Donald Trump is willing to assure Democratic victories if he can’t get the GOP to go along with his crazypants strategy to [suppresses snicker] overturn the 2020 election?! How monumentally selfish. Trump is prepared to let the Democrats carry the country over the cliff unless Republicans promise to indulge his absurd fantasy life. I hope that even Trump’s strongest supporters can recognize how selfish this is, and how much damage Trump is willing to inflict on the country for the sake of salving his ego. You have rarely if ever seen on this space me agree with Jonah Goldberg, but he’s right here:

And then in comes Trump, making waves like a stumbling drunk who didn’t see the hot tub until too late, literally saying that Democrats should win every election uncontested unless everyone “solves” the object of his batshit bullshittery. The single most important thing for Republicans to address isn’t critical race theory, vaccine mandates, the border, the supply chain cock-up, inflation, or anything having to do with foreign policy. It’s their commitment to a claim that was shot down by every court that looked at it, not to mention Trump’s own attorney general(s).

At least my solutions are aimed at the future and grounded in real policy stuff. I’m trying to figure out how to make the GOP better, more successful, and conservative in the long run. Meanwhile, Trump’s stolen election fantasy is simply and entirely about his own selfish id, his unrestrained narcissism, and his complete lack of concern with anything approaching real issues. He might as well be venting about how the time travel in Back to the Future really didn’t make much sense, given how little this stolen election nonsense has to do with not only reality, but stuff that might be helpful for the GOP. In other words, my alleged “Trump obsession” isn’t the issue or even a problem. But Trump’s very real and deranged Trump obsession is.

It already cost the GOP control of the Senate by losing Georgia. Now Trump proposes losing the whole country if his ego isn’t stroked.

Jonah Goldberg’s ideas for what the GOP ought to do are very different from my own, no doubt. But at least he is trying to deal with the world as it is. The 2022 and 2024 elections are going to be incredibly important. The idea that conservatives should sit it out if the GOP leadership doesn’t kowtow to Trump’s obsession with the 2020 election is berserk.

Speaking of berserk, a reader today sent me a link to an episode of the Eric Metaxas Show in which failed writer and professional ankle-biter John Zmirak calls out me, David French, Russell Moore and others as “spectacularly anti-Trump” in the last campaign. He says we are all “beta males,” and so forth. Golly.

Well, for the record, I was not anti-Trump, spectacularly or otherwise, in the last election. As regular readers know, I made a point of not saying who I was going to vote for, and of criticizing both candidates when I thought facts warranted. I’m certainly not an admirer of Trump, but I did not urge people not to vote for him. Unlike French, Moore, et alia, I’m not a Never Trumper. I believed, and do believe, in much of what Trump advocates, but I think he is his own worst enemy. I would like to have a conservative politician who believes what Trump believes, but who is actually a competent political leader. As long as the Republican Party is held captive to Trump’s personality cult, that person won’t be able to emerge.

That said, it is an honor to be with those guys in Zmirak’s crosshairs. I guess you’d have to know Zmirak — I have, since 1986 — to grasp how funny it is to have a guy like him accuse anybody of being a “beta male.” He is a short middle-aged man with a belly as big and as soft as a beanbag. Hey, I’m not short, but I’m only two years younger than Zmirak, and I have the same belly he does. We are men who make our living writing. Unless you’re Ernest Hemingway, Norman Mailer, or Sebastian Junger, it’s not especially the occupation of badasses. The only fight Zmirak is likely to have been in is when a sedevacantist hit him with his scapular. Hey, I am not exactly the pugilistic type either. But I know better than to go around calling better men than me “beta males.”

I would point out too that unlike David French, Zmirak never served in the military, which is a manly thing to have done. Unlike French, Moore, and me, Zmirak has never committed himself to a woman in holy matrimony, nor, like us, has he raised children. I don’t fault him for that. It’s not everybody’s calling to be a married person or a parent. But please, spare me the yappy he-man LARPing when you haven’t met any of the standard milestones of what it means to be a man in our culture. I don’t share all of David French or Russell Moore’s politics, but these are men who have accomplished big things in life. However mistaken they might be on this or that, those men are grown-ups. Zmirak is the same person he always was: an arrested-development sad sack who tries to get attention by insulting people. If you’ve ever seen him in action, bless his heart, it’s obvious why he has ended up like he has.

It’s not obvious to me why Eric Metaxas has ended up like he has. Unlike his agitated interlocutor, he is an actual adult. But I don’t give him a pass for allowing a shmendrick like Zmirak to come on his show all the time and say childish crap like that. That shows at the very least spiritual immaturity. You will recall that Eric last December called on patriotic Americans to prepare to “fight to the death, to the last drop of blood” to defend Donald Trump. Eric is an expensively groomed dandy who lives on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. This is not a criticism; I like his style! But the idea that Eric Metaxas, of all people, was urging people to give their lives for Donald Trump, is risible — about as risible as the George Costanza-like John Zmirak calling men who, unlike him, have actually accomplished serious things in life, “beta males.”

I wrote this post because an Evangelical pastor friend pointed the Zmirak/Metaxas insults out to me, and said that this kind of thing really does land with a significant number of Evangelicals, and that I should address it. If it’s true that a significant number of people still take these guys seriously, I’m sorry to hear it. This kind of talk is also politically immature. Zmirak squeaked and squawked about how evil Joe Biden is — and look, I agree with some of what he said — but you watch: is either he or Metaxas going to criticize Trump for his self-serving call to Republican voters to sit out the 2022 and 2024 elections unless GOP leadership kowtows to him? Of course not. Which makes you wonder what kind of weird psychological relationship they have with Trump.

I’m old enough to remember when John Zmirak was bragging to his friends about hanging a picture of Generalissimo Francisco Franco in his Manhattan office. He had much better taste in right-wing strongmen then. They were actually, you know, strong.

The post Trump & Beta Males appeared first on The American Conservative.

October 14, 2021

Will They Cancel Chappelle?

Have you seen the new Dave Chappelle special on Netflix yet? It’s not bad — not great, but not bad. It has some some laugh-out-loud lines, but mostly it’s pedestrian. Chappelle’s great, but this isn’t his best stuff. He has gotten in trouble, though, because of his critical comments about transgenders in the show. This NBC News report about the controversy quotes the controversial bits. It’s safe for work, so don’t worry:

If you’ve watched it, you will have heard that what Chappelle said is what millions and millions of us believe: that sex is a biological fact that cannot be erased, and that it is offensive to women to say that male-to-female trans persons are women. For this, the trans brigade and their fellow travelers in elite culture are calling for Chappelle’s head. Here is how The New York Times headlines its story about the controversy:

“Netflix loses its glow”? Really? The Chappelle special is one of the most watched shows on the service right now! Here’s the breakdown from Rotten Tomatoes, showing the critical response on the left, and the audience response on the right:

“Internal unrest at the company”? Three trans employees complained, with one of them making the customary bullsh*t argument that criticism or comedy about trans people is going to get trans people killed. Look, as I wrote earlier this year, this is a propaganda confection by activists. There is no evidence that of the trans people murdered, they were murdered for being trans (as opposed to dying in a domestic dispute, killed by a john — a large number of them were street prostitutes, and so forth). Do not believe these lies from the crybullies and their media allies.

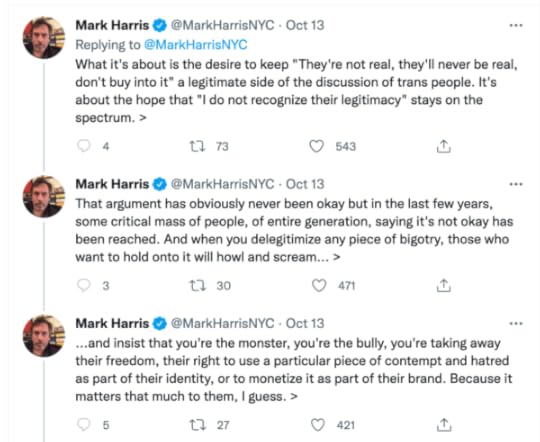

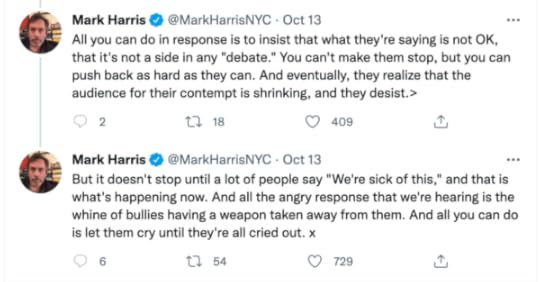

This is actually about coastal media elites and trans activists trying to cancel Chappelle and any dissent from trans dogma. Here is some commentary from a prominent entertainment journalist, the former executive editor of Entertainment Weekly:

Bullies? The bullies are those who are trying to cancel a comedian, and to silence any dissent from the trans-affirmative position. There can be no debate, no discussion: you must affirm — or else. Andrew Sullivan challenged Mark Harris’s stance, and got this response:

Watch this Chappelle controversy. If Netflix caves, it’s a terrible sign. If they don’t, then maybe, just maybe, other companies will realize that they don’t have to say “How high?” every time some left-wing activist tells them to jump.

The bullying of dissenters by trans activists and their allies is taking place to a disgusting degree in the UK right now, with the case of Prof. Kathleen Stock of the University of Sussex. Stock, who is a “gender critical” feminist — meaning that she doesn’t believe, for example, that trans women are women — has been advised not to leave her home, because the police say they can’t protect her. From a column about the controversy in UnHerd:

On Saturday, I was fortunate enough to chair a public event on “Hate, Heresy and the Fight for Free Speech” in London. I expected it to be a lively discussion; I’ve made two radio series celebrating the importance of disagreement. But I also expected it to be civilised, with respect shown for people, but not for bad ideas.

What I did not expect is that I would have to start the event by reading out a statement from one of the speakers because she had been advised that it might not be safe for her to leave her home and appear in person.

The speaker, as you may have guessed, was Kathleen Stock — a Professor of Philosophy who has been subjected to a campaign of harassment by anonymous trolls claiming to be students at Sussex University, where she teaches Philosophy, demanding for her to be sacked for her alleged views on transgender rights.

I say “alleged” because I have read her recent book, Material Girls, and it’s hard to see how it could be described as transphobic. “Trans people are trans people. We should get over it,” she writes. “They deserve to be safe, to be visible throughout society without shame or stigma, and to have exactly the life opportunities non-trans people do.” Certainly the book hardly amounts to “transphobic shit”, the term written on stickers that were recently plastered across Stock’s university building.

A mob of students is trying to get Stock fired for her heresy. The Sussex branch of the UK trade union representing academics threw Stock — and free speech — under the bus.

Read this piece by British lesbian feminist Julie Bindel, talking about her persecution by the trans mob simply for disagreeing with them. Here’s a piece by Anna Djinn, a British feminist who talks about how she became a TERF (Trans Exclusive Radical Feminist), the side of the debate that Dave Chappelle takes. She’s talking here about being confronted at a demonstration by three male-to-female trans persons who told her she didn’t know what it meant to be a woman:

I told them I was a mother, I’d given birth, breast fed. But they had no interest in listening to me, an actual woman, so convinced were they of their own rightness.

I went away feeling deeply disturbed. Their insistence that they were not only women, but a superior kind of woman, was almost too bizarre to take seriously. But they would entertain no dissent. Perhaps it was this that made me feel sick.

I thought of my mother, my grandmothers, of all the women who came before me, who gave me life and love. I thought of how their lives had been constrained and constricted by the system that granted the men in their lives more or less absolute power over them. I thought of their tough struggles to survive, of their determination that their children would have a better life than they did.

I thought of my own life and my defining struggle to crawl out from the Stockholm Syndrome of femininity and to find myself as actor on my own terms, not in relation to any man.

Gradually I came to see the trans-activist movement as part of the backlash to the gains women had made over the previous decades. I saw their goal with startling clarity: to return females to their place in a Stockholm Syndrome relationship with their true masters, men (as whom, in spite of their claims to be women, they clearly identified).

The trans-activist movement is not a progressive movement. At its heart it is regressive. And that is why it appeals to so many with nefarious interests.

We are told that people like Anna Djinn, Julie Bindel, Kathleen Stock, and Dave Chappelle — none of them conservative! — have to shut up. That they’re thought criminals. What kind of message does this send to girls?

The post Will They Cancel Chappelle? appeared first on The American Conservative.

Gods Of This World

Good afternoon from suburban Chicago, where I’m here for the annual Touchstone conference. I think you can still come if you want to — register here. Don’t come to hear me, or Carl Trueman, or Hans Boersma, or Tony Esolen, or Allan Carlson, or any of the other speakers. Come to meet Catriona Trueman, Carl’s wife. She makes the very best shortbread on this planet — which I say without fear of contradiction. Carl sent me some a while back, and I could not believe how delicious it was. Catriona came to this conference with Carl, and lo, I met them on the sidewalk waiting for our rides! She brought me shortbread!

I’m holed up in my hotel room trying to get caught up on e-mail and blogging, and eating shortbread like it was lembas. You come to this conference, and you get to meet Catriona, and try to talk her out of the recipe.

Carl tells me sales of his great book The Rise And Triumph of the Modern Self have been terrific. This is well-deserved; I think it’s one of the most important books of our time. This book really does provide the key for understanding the disorders of our era. When you read that book, you realize how off-base some of our most heated culture-war controversies are. By “off-base,” I don’t mean that they aren’t real. They most certainly are real. What I mean is that we social and religious conservatives are reacting to symptoms of a much deeper problem. Funny, but on the flight up from Baton Rouge, I was re-reading Modris Ekstein’s invaluable cultural history Rites of Spring: The Great War and the Birth of the Modern Age. It’s a great companion to Carl’s book, because both discuss how the West has been dismantling itself for a very long time now, in the name of liberating the Self. These lines are powerful:

Diaghilev’s ballet enterprise was both a quest for totality and an instrument of liberation. Perhaps the most sensitive nerve it touched—and this was done deliberately—was that of sexual morality, which was so central a symbol of the established order, especially in the heart of political, economic, and imperial power, western Europe. Again, Diaghilev was simply an heir to a prominent, accumulating tradition. For many intellectuals of the nineteenth century, from Saint-Simon through Feuerbach to Freud, the real origin of “alienation,” estrangement from self, society, and the material world, was sexual.

“Pleasure, joy, expands man,” wrote Feuerbach; “trouble suffering, contracts and concentrates him; in suffering man denies the reality of the world.”

The Sexual Revolution of the 1960s had actually been underway for all the twentieth century, and some years before. There is no avoiding the conclusion that Philip Rieff would draw later: if you lose sexual restraint as a civilizing principle, you lose Christianity (and more besides).

It’s a dour conclusion, I suppose, but it happens to be true. Mary Frances Myler is an undergraduate at the University of Notre Dame, and in this article from a student newspaper, she calls out the Catholic university’s leadership for surrendering the Church’s teachings on sexuality to appease the Zeitgeist. Excerpts:

This past June, the university announced its first ever celebration of Pride Month. The diversity and inclusion page of the university’s website published an article which draws exclusively upon President Biden’s “Proclamation on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Pride Month, 2021” in an effort to “raise awareness about efforts for equal justice and equal opportunity for the LGBTQ+ community” during the month of June. The article directs curious readers to the website of the Human Rights Campaign, the largest LGBT advocacy group lobbying organization within the United States, for information on “what it means to be an ally in the effort to achieve equality for all.” The article does not allude to the Catholic Church or her teachings in any way.

Just this week, on October 11, PrismND (Notre Dame’s official LGBTQ+ undergraduate organization) and Baumer Hall co-hosted a “Coming Out Day Celebration.” Fr. Robert Lisowski, C.S.C., rector of Baumer and recently-ordained priest, attended the event wearing a rainbow stole which matched the pride flag hanging on the wall directly behind him. When asked for comment on his involvement with the event, Fr. Lisowski told the Rover, “My presence at this event was simply to affirm, support, and celebrate the dignity of every human person as a child of God. We prayed in gratitude for the unique gift that every person is [and] for an end to discrimination.”

Other erosive occurrences disclose the university’s adherence to secular standards set by the LGBT movement. The home page of the ND Student Government website displays a picture of the student government executives in front of a pride flag. The College of Arts and Letters now accommodates students’ preferences for the use of singular “they/them” pronouns in news articles. And this fall, Notre Dame Press published the book Gay, Catholic, and American written by Greg Bourke, who was a named plaintiff in Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), the decision that legalized same-sex unions nationwide.

It goes on. More:

Properly nuanced, the Church’s teachings on sexuality are simple. In light of Catholic doctrine, Notre Dame should recognize the incoherence of her current position. Her current approach confuses, rather than models, Church teaching. In order to resolve her current incoherence, the university must choose between two conflicting views—one Catholic, the other secular.

The implications of this choice are dramatic; each departure from doctrine erodes the Catholic character of the university. If the university adheres to secular standards on LGBT issues, what else will she be willing to surrender? When truth capitulates to untruth, what shall stand?

Exactly right. How is it that a Notre Dame undergraduate understands this, but Father John Jenkins, the university’s president, does not? As Mary Frances Myler points out, all Notre Dame undergrads are compelled to go through “Welcome Week,” which emphasizes “allyship” — which is to say, the University of Notre Dame trains its students if not to defy Catholic teaching on LGBT, then to be thoroughly confused about what it is and what that requires of them as Catholics.

What bad leadership all of us small-o orthodox Christians have right now from most of our elites! They don’t seem to understand the crisis at all. Carl Trueman lays into Evangelical elites in a recent First Things essay. Excerpt:

Last year I taught a class in historical method at Grove City College. One of our texts was Marsden’s The Outrageous Idea of Christian Scholarship. The students’ response to the book was striking. Though they saw Marsden as a thoughtful and engaging writer, they considered his argument—that Christians could find a place at the academy’s table by being good scholars and treating colleagues with respect—unpersuasive in the present context. No student today thinks that a professor in any discipline at a research university who is polite and respectful to a gay colleague will also be allowed to voice his objections to gay marriage. That is not how the system works anymore.

My students have an accurate view of reality. Today’s cultured despisers of Christianity do not find its teachings to be intellectually implausible; they regard them as morally reprehensible. And that was always at least partially the case. This was the point missed by Noll and Marsden—though it may not have been as obvious at Wheaton College or the University of Notre Dame in the nineties as it is almost everywhere in higher education today. Our postmodern world sees all claims to truth as bids for power, all stable categories as manipulative—and the task of the academy is to catechize students into this orthodoxy. By definition, such a world rejects any notion that scholarly canons, assumptions, and methods can be separated from moral convictions and outcomes. Failure to conform to new orthodoxies on race, morality, sexual orientation, and gender identity is the main reason orthodox Christianity is despised today. These postmodern tenets rest upon cultural theories that cannot accommodate Christianity, precisely because they underwrite today’s academic refusal to discuss and weigh alternative claims. To oppose critical race theory or gender theory is to adopt a moral position that the culture’s panjandrums regard from the outset as immoral. The slightest hint of opposition disqualifies one from admission to polite society.

Trueman’s overall point is that there is no place to hide anymore: if you are a believing orthodox Christian, the world really does consider you to be the Enemy. It’s the end of winsomeness as a strategy for acceptance.

This Touchstone conference theme is “No Neutral Ground: The Cost of Discipleship In A Secular Age”.For the next two days, we are going to be talking seriously about how faithful Christians should live here in the post-Christian, and increasingly anti-Christian, world. If you are prepared to capitulate to the world, this conference is not for you. If not, well, if you can get here, come on!

Let me also commend to you Ephraim Radner’s First Things piece about the kind of theology we will need in this new Dark Age. It’s pretty much the same theology we needed during the last one. Excerpt:

Theological work in the Dark Age ahead will need to learn from the Dark Age behind. It must be stripped down and focused on the Scriptures’ invitation to bring the apostolic world into the present, and not be “updated,” but rather “backdate” our spiritual imaginations. Brown writes of Gregory the Great’s “austere assumption that there was only one permanent and all-important object on which the human mind could always work”: the “raw stuff of human nature” brought to a place of “transparency to God.” Theologians, like the rest of the world, are holding on to far too much. “Much of the comfort and richness of a culture could and should be sacrificed to that one overriding aim.” Lest we also forget, that should be our goal, too.

Over at my (subscription-only) Substack newsletter, I’ve been speculating on why Orthodox parishes in the US have been receiving an unusual number of inquirers during Covid. I think Radner’s point in that paragraph explains it. People understand that the times are evil, and growing darker. They know they need something deep, real, and rooted firmly in the Fathers.

The post Gods Of This World appeared first on The American Conservative.

October 13, 2021

Ideological Medicine Undermines Trust

I was just recording the next episode of the General Eclectic podcast that Kale Zelden and I do, and I mentioned Abigail Shrier’s blockbuster interview with two leading medical carers who serve transgender patients (both of them — one a surgeon, one a clinical psychologist — are also male-to-female trans people). In the interview, both doctors said that the medical field is going way too far in the way it cares for young people with gender dysphoria (e.g., they said puberty blockers are prescribed far too often). From the piece:

“There are definitely people who are trying to keep out anyone who doesn’t absolutely buy the party line that everything should be affirming, and that there’s no room for dissent,” [surgeon Marci] Bowers said. “I think that’s a mistake.”

You’d think it would have made national news when two of the leading trans-care physicians sound the alarm about standards of care. Nope. But if you read the piece, you’re not surprised. From the Shrier report:

Earlier this month, [clinical psychologist Erica] Anderson told me she submitted a co-authored op-ed to The New York Times warning that many transgender healthcare providers were treating kids recklessly. The Times passed, explaining it was “outside our coverage priorities right now.”

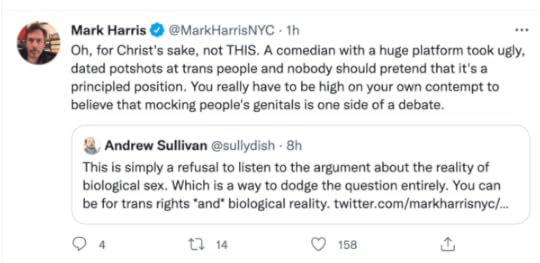

There is only one perspective on transgenderism allowed in medicine, and only one allowed in the mainstream media. After the piece appeared, the two big transgender health associations released the following:

Got that? Don’t talk about these things in the “lay press,” they say. Trust the experts.

Bull. I don’t trust the medical experts on transgenderism, and I don’t trust the media to tell us the full story around trans issues. They are not after the truth; they want to support a narrative. From Live Not By Lies:

A Soviet-born US physician told me—after I agreed not to use his name—that he never posts anything remotely controversial on social media, because he knows that the human resources department at his hospital monitors employee accounts for evidence of disloyalty to the progressive “diversity and inclusion” creed.

That same doctor disclosed that social justice ideology is forcing physicians like him to ignore their medical training and judgment when it comes to transgender health. He said it is not permissible within his institution to

advise gender dysphoric patients against treatments they desire, even when a physician believes it is not in that

particular patient’s health interest.

See? This doctor cannot allow himself to comment on health matters that might be controversial, out of fear that he will inadvertently violate the narrative. And he definitely can’t use his best medical judgment regarding transgenderism. That right has been taken from all the physicians at his large urban hospital, by hospital management.

It is not about medical science. It is about ideology.

What occurred to me today, thinking about the constant lying regarding transgenderism carried out by the medical field and the media, is this: if they are willing to lie for the sake of the narrative about transgenderism, and suppress dissent, why should I believe that they’re not doing this around the Covid vaccine narrative?

As you readers know, I am vaccinated, and I am generally pro-vaccination. But I gotta say, watching the ideologically-motivated lying around transgender care is dissolving my trust in medical authorities across the board, at least when the medical issues touch on ideology. Whenever people tell you to “trust the science,” you had better put your b.s. detector on. We live under a regime that has no restraints about lying to protect and promote its narrative.

The post Ideological Medicine Undermines Trust appeared first on The American Conservative.

Soft Totalitarianism’s Legal Brigade

Back in 2015, after the culture war Waterloo that was the Indiana RFRA fight (that was the event in which Woke Capitalism flexed its muscles), an elite law professor who was a closeted Christian reached out to me with some dire predictions about what was coming for faithful Christians. I wrote about his warnings, and dubbed him “Prof. Kingsfield,” after the legendary law professor in The Paper Chase. From that 2015 post:

Like me, what unnerved Prof. Kingsfield is not so much the details of the Indiana law, but the way the overculture treated the law. “When a perfectly decent, pro-gay marriage religious liberty scholar like Doug Laycock, who is one of the best in the country — when what he says is distorted, you know how crazy it is.”

“Alasdair Macintyre is right,” he said. “It’s like a nuclear bomb went off, but in slow motion.” What he meant by this is that our culture has lost the ability to reason together, because too many of us want and believe radically incompatible things.

But only one side has the power. When I asked Kingsfield what most people outside elite legal and academic circles don’t understand about the way elites think, he said “there’s this radical incomprehension of religion.”

“They think religion is all about being happy-clappy and nice, or should be, so they don’t see any legitimate grounds for the clash,” he said. “They make so many errors, but they don’t want to listen.”