Rod Dreher's Blog, page 476

March 21, 2017

Critical Cheers For Cannibal Movie

Raw, about a young girl who develops an all-consuming appetite for human flesh, made its world premiere at the 2016 Cannes Film Festival before playing at other fests, including Toronto. Focus World picked up rights to the movie following Cannes.

“Marking the feature debut of French director Julia Ducournau, who leads a terrific young cast into a maelstrom of blood, guts and unfettered sexual awakening, this Cannes Critics’ Week selection should become a hot potato (or is that a meatball?) at the market while propelling its talented creator into the spotlight,” The Hollywood Reporter‘s review said of the movie. Adding to the gore factor is the fact that the film is set at a Gallic veterinary college.

The story is about how movie theaters are handing out barf bags to patrons. Oh, John Waters, aren’t you glad you’re living in this time? From the Hollywood Reporter‘s review:

In the middle of the drunken bacchanal, Justine reunites with Alexia, a fiery brunette who only half helps her younger sister to learn the ropes — which include getting bathed in animal blood and eating raw liver upon request (perhaps Leonardo DiCaprio should enroll there). The problem is that, like the rest of her family, Justine is a devout vegetarian, so making it out of freshman hell will mean she has to start doing the impossible — or rather the inedible — and become a carnivore herself.

The catch, of course, is that Justine likes it. In fact, she likes it so much that her appetite for uncooked meat begins to take hold of the young woman — who, we eventually learn, is also a virgin — in some highly unsavory ways, driving her to commit acts of increasing savagery that will cause the film’s ketchup-count to reach exponential numbers.

Weimar America. The Weimarization of the West.

Remember: St. Benedict was so disgusted by the decadence of the city of Rome that he walked out of it and headed for the forest to figure out what to do. This is us, you know. A culture that celebrates the depiction of cannibalism as sexualized entertainment.

What are you going to do about it? No, seriously, what? Is this the world you want your kids to grow up in?

Is this not completely insane? What a culture!

Porn, Technology, & Christians

A reader of The Benedict Option writes:

I have only followed your blog for a short time and I bought your book on its release day (the first time I’ve ever done that). I am profoundly grateful for your courage and passion in waking up the Western church towards the insidious future we face.

I grew up as a missionary kid in [a Third World country] at a school/community for missionary kids. It was a boarding school where families, who lived in remote villages, sent their kids to receive a Western education in order for them to be able to go back to colleges in America.

Growing up there at that school was very much like what you describe in your book. We had actual borders with the jungle and river isolating us from most of the world. We had no internet, only one tv for the whole school, and this was great! We played in the jungle, read a ton of books, went swimming, and developed the deepest friendships I’ve ever known in my life. We had the time to develop friendships.

The school was also a place of deep Protestant/ evangelical faith. We had our own Sunday services, morning and evening. I learned hymns from a young age. When I was in high school, my classmates and I were required to lead a Sunday evening service once a semester. At the time, much of this seemed trite and boring at times, but as I’ve grown older I’m overwhelmed at the beauty of my growing up years. Those years have given me a vision of what Christianity and the truths it teaches can do for small communities.

Of course the community had its many flaws. Our ability to be critical far outweighs our ability to praise, and so we often miss the wonderful things we have in life. One flaw though was the utter lack of guidance of teaching on sex. It was taboo. When one of my sisters and her friend wanted to talk about masturbation at a girls bible study, the dorm parent quickly put the kibosh on it. The guys were no different. I don’t think it’s an overstatement to say that most of us struggled with masturbation.

Thankfully we had no internet so we couldn’t access porn. When I had come back to America in 1999 for a year furlough I was 11. I saw pornography for the first time. I was captivated. My parents were naïve and unaware of my growing addiction, and remained so for years. What’s worse to me about seeing porn is not that I became an addict to sex, but that I lost my love of learning. I was a top student at school, but after I saw porn I lost my ability for wonder and awe at creation. I lost my motivation for life in many ways. I lost the sweetest gift of life for a child: innocence of evil.

My change was so evident back in [the country]. I was rebellious and did poorly in school. Most figured I was simply going through puberty. That wasn’t it at all. I was unmoored from reality and lost in the dark world of lust and selfishness. It wasn’t till college where I began to get help through a wonderful dean of men at my school who loved me and helped me fight against my addiction. I wish my community had been more willing to speak honestly and work diligently to protect my innocence.

I see the same thing today in the Evangelical church circles I move in. We are naïve and foolish about how dangerous technology can be at times. Sometimes I think our push to evangelize and engage the culture has done significant harm to us Protestants. We are so quick to push people to make disciples [Note: I think he means witness to and convert others — RD] after they become believers. I don’t think this a bad thing, but is it the wisest way to make disciples? People need to be taught Christian truths! The early church understood this! They took it seriously! Why can’t we?

I encourage you to read, Grounded in the Gospel- Building Believers The Old-Fashioned Way by JI Packer and Gary Parret. The first two chapters on the need for catechesis and the historical evidence for catechesis. I know you are Orthodox, but it’s a book all would do well to heed. They quote Martin Luther, who said that the church would rise or fall on it s commitment to catechesis. I wish more evangelical pastors would read it. It’s not enough to preach on Sundays. We need to teach the people throughout the week. Richard Baxter did this with his congregation of 800 people. He bought catechisms for every member, and he and his curate went house to house and taught them. This had a tremendous influence for good. When Baxter left for several years to join in the English civil war, his congregation held fast to the Gospel even though many “wolves” came to try and mislead them. Do you think that would have happened without catechesis? Hardly.

Another important book is David Wells’ Whatever Happened to Truth? His indictment is stellar. The most important criticism is the professionalization of the ministry. Pastors are seen as administrators and not theological and spiritual leaders of the church. Thus catechizing has gone to the birds in churches. We also see people as selves not souls, as you say, and we run to psychiatrists for help too much.

The greatest problem, though, in my mind is apathy. We are asleep to the catechizing that the world does to us and since we don’t care to think about it, we drift to the edge of a cliff. If we don’t wake up we are going to fall and it will be a terrible fall for many of us. I agree with you that our greatest need is to build a counter culture to the world. I’m going to do my best to build that here in [my city].

Thanks for that letter. Readers, please take this seriously. If I posted every story I heard about the devastating effect pornography is having on Christian individuals, couples, and families, it would overwhelm you. It is impossible to guarantee that your kids will never see it when they’re young, but for pity’s sake, do you have to make it easy for them by giving them smartphones?

This e-mail made me think about the kids at the Bruderhof. No smartphones. No Internet. Just wholesome, normal kids. They have no idea what kind of gift they’re being given: the gift of a childhood.

Actually, Sir, They Will Lie For You

I was talking with a conservative friend in DC last week, a Trump supporter who expressed intense frustration with his man. He said these idiotic tweets, his lack of personal discipline, and the general chaos in the White House, are destroying the possibility of a transformative presidency. I’m paraphrasing in polite language. He was rather less so in the moment. He said that the wheels are coming off, and setting the stage for a major Democratic comeback — and there will be lots of Republican blood on the tracks.

Maybe so. It is undeniable, though, that Trump is his own worst enemy — especially with his tweets. Rich Lowry explains:

Every administration gets knocked off its game early on by something. What makes the furor over President Trump’s wiretapping claims so remarkable is how unnecessary it is. The flap didn’t arise from events outside of the administration’s control, nor was it a clever trap sprung by its adversaries. The president went out of his way to initiate it. He picked up his phone and tweeted allegations that he had no idea were true or not, either to distract from what he thought was a bad news cycle, or to vent, or both.

The fallout has proved that there is no such a thing as “just a tweet” from the most powerful man on the planet. Trump’s aides have scrambled to find some justification for the statements after-the-fact and offended an age-old foreign ally in the process (White House press secretary Sean Spicer suggested it was British intelligence that might have been monitoring Trump); congressional leaders have become consumed with the matter; and it has dominated news coverage for weeks. Such is the power of a couple of blasts of 140 characters or less from the president of the United States.

The flap has probably undermined Trump’s political standing, and at the very least has diverted him and his team from much more important work on Capitol Hill, where his agenda will rise or fall. In an alternative and more conventional universe, the White House would be crowing over Judge Gorsuch’s testimony before Congress. Instead it is jousting with the FBI director over wayward tweets.

David French continues in this vein:

The tweets, however, are exposing something else in many of Trump’s friends and supporters — an extremely high tolerance for dishonesty and an oft-enthusiastic willingness to defend sheer nonsense. Yes, I know full well that many of his supporters take him “seriously, not literally,” but that’s a grave mistake. My words are of far lesser consequence than the president’s, yet I live my life knowing that willful, reckless, or even negligent falsehood can end my career overnight. It can end friendships instantaneously. Why is the truth somehow less important when the falsehoods come from the most powerful and arguably most famous man in the world?

I’ve watched Christian friends laugh hysterically at Trump’s tweets, positively delighted that they cause fits of rage on the other side. I’ve watched them excuse falsehoods from reflexively-defensive White House aides, claiming “it’s just their job” to defend the president. Since when is it any person’s job to help their boss spew falsehoods into the public domain? And if that does somehow come to be your job, aren’t you bound by honor to resign? It is not difficult, in a free society, to tell a man (no matter how powerful they are or how much you love access to that power), “Sir, I will not lie for you.”

French goes on: “The truth still matters, even when fighting Democrats you despise.”

Does it, though? I mean, it should, but haven’t we determined already that for more than a few conservatives, principles are nothing more than clubs with which to beat liberals?

UPDATE: David J. White gets it right:

The problem for the Democrats, when they come back is that, as we have seen, what any one president does affects the presidency itself and has repercussions for his successors. For example, as we have seen, a president who governs by executive orders or wages undeclared wars without explicit authorization from Congress enables his successors, even those from the other party, to do the same.

I think Trump’s behavior will be seen to have diminished the stature not only of his presidency, but of the office of the presidency itself, and that is something that his successors, regardless of their party, will have to deal with.

The Nazism Of Narnia

Writing in Slate, professor Alan Levinovitz defends intolerance. Excerpt:

Just as it is foolish to condemn all intolerance, it is also misguided to make strict rules about permissible forms of intolerance. No shouting. No breaking the law. The correct form of intolerance always depends on its object and its context. If Charles Murray were to hand out copies of The Bell Curve in a supermarket, it would be entirely acceptable to shout at him. Sometimes laws need to be broken—sometimes you need to sit at the front of the bus. And for all but the staunchest pacifists, violence can be a perfectly justifiable way to express intolerance when someone attacks you.

Earlier I claimed that it’s no longer controversial to think that civil liberties don’t depend on race, gender, or religion. Unfortunately, a clear-eyed assessment of the evidence shows that many people would likely embrace a return to the (not so) good old days. In this country, a congressman can publically express ethno-nationalism—“We can’t restore our civilization with somebody else’s babies”—and be praised by colleagues for it. The longtime best-selling book of Christian apologetics—C.S. Lewis’ Mere Christianity—calls for religious nationalism (“all economists and statesmen should be Christians”) and argues that God wants men to be the head of the household. These are popular ideals, but they are poisonous and deserve fierce resistance, not complacent tolerance.

Let the record show that a Stanford and University of Chicago-trained philosophy and religion professor (who holds an M.Div) believes that the proper way to address Charles Murray’s arguments is by shouting them down. Let the record show that a Stanford-and-Chicago-trained philosophy and religion professor believes that we should not allow the arguments of C.S. Lewis — C.S. Lewis! — to be heard, because people might come to believe them. And let the record show that this did not appear in a magazine of the radical left, but in a center-left publication owned by Jeff Bezos, one of the richest and most powerful men in the world.

Prof. Levinovitz begins with reasonable points: No society can tolerate everything, and tolerance’s value is relative to the truth. But, as MacIntyre would say, which truth? Whose truth? Levinovitz is quite certain he knows the answers: his own truth, which he believes is the Truth. In this piece, he thinks that moral truth and political truth can be known with the same certainty as scientific truth — and that secular liberalism is in full possession of that truth. Therefore, when you shout down Charles Murray or a follower of C.S. Lewis, you are serving the truth.

In an open letter he wrote on Slate to Marco Rubio, addressing the then-presidential candidate’s claim that America needs more welders and fewer philosophers, Levinovitz wrote:

I won’t quit because my colleagues and I are part of a sacred order, bound to seek out and profess truth, no matter how complicated or unappealing that truth might be. The truth about evolution, for example—and why people like you, Sen. Rubio, seem incapable of believing in it.

I won’t quit because there’s no feeling like the one I get when a student says my class has changed his or her life. It’s as if I’ve performed alchemy or magic: With nothing more than a powerful set of symbols (and a PowerPoint), I can, on occasion, alter the very fabric of people’s reality. It’s like church, but for everyone.

So Levinovitz says academia is a universalist religion that instantiates a “sacred order.” More:

In fact, humanities professors like me work against many of your core values. Explaining the origin and persistence of creationist pseudoscience? Religion and philosophy. Shutting down racists and sexists who explain discrimination with “natural differences”? Anthropology and history. We can’t take all the credit, of course, but the fact that the arc of history seems to bend toward justice is due, at least in part, to the efforts of humanities scholars.

This man is not a disinterested scholar. He’s a zealot, and an extremely self-righteous one at that. Prof. Levinovitz is as ardent for his own god as any hidebound fundamentalist is for his. The thing is, Levinovitz is very high-church, in that he speaks for the elites in American society.

I’ll give Levinovitz this much: he understands the nature of the culture war better than many of us Christians do. As they consolidate their power, secular fundamentalists like Levinovitz will continue to try to shout down, forbid, condemn, and suppress orthodox Christians and any other religious believers who contest the established religion.

Know that this is coming. And prepare for it. What we conservatives must do is stop believing that it can’t happen here. The Law of Merited Impossibility — It will never happen, and when it does, you bigots will deserve it — is vindicated every day. Think of it: this college professor, publishing in a mainstream center-left publication, calls for treating the work of C.S. Lewis as a threat to civilization.

What completely escapes Prof. Alan Levinovitz is that his bigotry and intolerance is an effective recruiting device for the far right. For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. As I keep saying, the Alan Levinovitzes of the world, and the Slate magazines, have no idea what demons they are summoning. They will.

The Telos Crisis

David Brooks says that America has lost its way as a nation. Excerpts:

One of the things we’ve lost in this country is our story. It is the narrative that unites us around a common multigenerational project, that gives an overarching sense of meaning and purpose to our history.

For most of the past 400 years, Americans did have an overarching story. It was the Exodus story. The Puritans came to this continent and felt they were escaping the bondage of their Egypt and building a new Jerusalem.

The Exodus story has six acts: first, a life of slavery and oppression, then the revolt against tyranny, then the difficult flight through the howling wilderness, then the infighting and misbehavior amid the stresses of that ordeal, then the handing down of a new covenant, a new law, and then finally the arrival into a new promised land and the project of building a new Jerusalem.

The Puritans could survive hardship because they knew what kind of cosmic drama they were involved in. Being a chosen people with a sacred mission didn’t make them arrogant, it gave their task dignity and consequence. It made them self-critical. When John Winthrop used the phrase “shining city on a hill” he didn’t mean it as self-congratulation. He meant that the whole world was watching and by their selfishness and failings the colonists were screwing it up.

But we have lost our national story. We no longer have a telos — that is, a shared goal, a sense of mission that unites us and raises us out of ourselves. More:

Today’s students get steeped in American tales of genocide, slavery, oppression and segregation. American history is taught less as a progressively realized grand narrative and more as a series of power conflicts between oppressor and oppressed.

The academic left pushed this reinterpretation, but as usual the extreme right ended up claiming the spoils. The people Gorski calls radical secularists expunged biblical categories and patriotic celebrations from schools. The voters revolted and elected the people Gorski calls the religious nationalists to the White House — the jingoistic chauvinists who measure Americanness by blood and want to create a Fortress America keeping the enemy out.

We have a lot of crises in this country, but maybe the foundational one is the Telos Crisis, a crisis of purpose. Many people don’t know what this country is here for, and what we are here for. If you don’t know what your goal is, then every setback sends you into cynicism and selfishness.

I agree with most of this, but I would take the critique a bit deeper: we have a Telos Crisis in America not simply because we have lost a sense of collective meaning, but because here in late modernity, most of us have lost a belief that there can be meaning independent of our individual desires. Marxism, the secular utopia, has failed. Even most Christians today believe in a God whose purpose is to validate our quest for happiness — which is not the same thing as holiness.

David says the Exodus story from the Hebrew Bible ought to be our national mythological template. We have to remember that the Hebrews coming out of Egypt believed they were going somewhere definite. Where is America going? When we had a shared Judeo-Christian ethic, we at least had a picture of what the Promised Land (so to speak) to which we as a people should aspire. We believed that because we believed, however imperfectly, that there was a moral order independent of ourselves by which we were all called to live. That moral order was revealed and guaranteed by the God of the Bible.

The 20th century cultural revolution — which included a revolution in theology — left this in shambles. As Brad East pointed out last week, Christian theologians and cultural critics have been talking about this for decades. Awareness of this stark new reality long predates The Benedict Option, a book written in response to the crisis. The problem David Brooks identifies — the loss of a binding national narrative — is not something American Christians are prepared to address because we ourselves have also lost our religious narrative. Sociologist Christian Smith has written:

We are also not saying than anyone has founded an official religion by the name of Moralistic Therapeutic Deism, nor that most U.S. teenagers have abandoned their religious denominations and congregations to practice it elsewhere or under another name. Rather, it seems that the latter is simply colonizing many established religious traditions and congregations in the United States, that it is merely becoming the new spirit living within the old body. Its typical embrace and practice is de facto, functional, practical, and tacit — not formal or acknowledged as a distinctive religion. Furthermore, we are not suggesting that Moralistic Therapeutic Deism is a religious faith limited to teenage adherents in the United States. To the contrary, it seems that it is also a widespread, popular faith among very many U.S. adults. Our religiously conventional adolescents seem to be merely absorbing and reflecting religiously what the adult world is routinely modeling for and inculcating in its youth.

Moreover, we are not suggesting that Moralistic Therapeutic Deism is a religion that teenagers (and adults) adopt and practice wholesale or not at all. Instead, the elements of its creed are normally assimilated by degrees, in parts, admixed with elements of more traditional religious faiths. Indeed, this religious creed appears in this way to operate as a parasitic faith. It cannot sustain its own integral, independent life. Rather it must attach itself like an incubus to established historical religious traditions, feeding on their doctrines and sensibilities, and expanding by mutating their theological substance to resemble its own distinctive image. This helps to explain why millions of U.S. teenagers and adults are not self-declared, card-carrying, organizationally gathered Moralistic Therapeutic Deists. This religion generally does not and cannot stand on its own. So its adherents must be Christian Moralistic Therapeutic Deists, Jewish Moralistic Therapeutic Deists, Mormon Moralistic Therapeutic Deists, and even Nonreligious Moralistic Therapeutic Deists. These may be either devout followers or mere nominal believers of their respective traditional faiths. But they often have some connection to an established historical faith tradition that this alternative faith feeds upon and gradually co-opts if not devours.

Believers in each larger tradition practice their own versions of this otherwise common parasitic religion. The Jewish version, for instance, may emphasize the ethical living aspect of the creed, while the Methodist version stresses the getting-to-heaven part. Each then can think of themselves as belonging to the specific religious tradition they name as their own — Catholic, Baptist, Jewish, Mormon, whatever — while simultaneously sharing the cross-cutting, core beliefs of their de facto common Moralistic Therapeutic Deist faith. In effect, these believers get to enjoy whatever particulars of their own faith heritages appeal to them, while also reaping the benefits of this shared, harmonizing, interfaith religion. This helps to explain the noticeable lack of religious conflict between teenagers of apparently different faiths. For, in fact, we suggest that many of them actually share the same deeper religious faith: Moralistic Therapeutic Deism. What is there to have conflict about?

MTD doesn’t demand anything of you except that you affirm that there is a gauzy God looking out over the affairs of men, and that He wants you to be happy and nice to others. This is not the God of the Book of Exodus. This is not the God revealed to us in Exodus 20:

Seeing the thunder pealing, the lightning flashing, the trumpet blasting and the mountain smoking, the people were all terrified and kept their distance.’Speak to us yourself,’ they said to Moses, ‘and we will obey; but do not let God speak to us, or we shall die.’

Moses said to the people, ‘Do not be afraid; God has come to test you, so that your fear of him, being always in your mind, may keep you from sinning.’

So the people kept their distance while Moses approached the dark cloud where God was.

In his (difficult and uneven) posthumously published book Charisma, the social critic Philip Rieff, a secular Jew, diagnoses the modern problem as a loss of “holy terror” — something the Bible calls “fear of the Lord.” From Rieff’s first chapter (N.B., by “charismatics,” Rieff means :

Perhaps the best place to begin is with the suggestion that holiness is entirely interdictory [that is, forbidding, proclaiming ‘thou shalt nots’ — RD]. A moral absolute thus becomes the object of all. Holy terror is charismatic [a bearer of grace — RD]; our terror is unholy. For our charismatics are engaged in no wrestlings of angels, but, rather, with the obeying of demons. Jacob was a charismatic when Laban and Jacob took mutual pledges before the God of their fathers; Jacob swears by the fear of his father, Isaac (Genesis 31:53). What is this charismatic fear? What is holy terror? Is it a fear of a mere father; in a phantasmagoric enlargement, Freud’s idea is silly. Holy terror is rather fear of oneself, fear of the evil in oneself and in the world. It is also fear of punishment. Without this necessary fear, charisma is not possible. To live without this high fear is to be a terror oneself, a monster. And yet to be monstrous has become our ambition, for it is our ambition to live without fear. All holy terror is gone. The interdicts have no power. This is the real death of God and of our own humanity. It is out of sheer terror that charisma develops. We live in terror but never in holy terror. Those are the only alternatives, as I shall try to show in the course of this book.

A great charismatic does not save us from holy terror, but rather conveys it. One of my intentions is to make us again more responsive to the possibility of holy terror.

Rusty Reno’s review of Rieff’s Charisma brings all this down to earth, as does Christopher Caldwell’s in the Times. Excerpt:

For Rieff, “all high cultures … are cultures of the superego.” A culture is a sacred “moral demand system,” sharply divided along lines of faith and guilt. Faith means obedience to commandments. Guilt means transgression, not as that word is understood in graduate schools but as it is understood in the Bible — as ostracism, disgrace and death. The system is ruthless, but Rieff shows it to be more supple than it looks. This is one of the windfalls of his long apprenticeship to Freud. Faith and guilt, like yin and yang, imply their opposites. Immoral impulses are always there. “They may be checked,” Rieff writes, “but they are not liquidated, they are not destroyed by these interdictory processes any more than the instincts are liquidated or destroyed by therapeutic processes.” Indeed, there would be no reason to have rules — a culture — without them.

As Rieff shows in some magnificent passages of biblical exegesis, charismatics — those with charismata, or special gifts of grace — are the moralists in this system. But they do not work by bossing people around or seeking power; they work by submitting to the existing covenant in ways that provoke imitation. So, paradoxically, “renewal” movements tend to be reactionary, and even prophets are backward-looking — they are tethered to, draw their credibility from and seek to intensify previous revelation. These principles are true of Christianity as a whole, in its relation to Judaism. Pivotal here is the passage in Mark 10:17-19, where a rich man asks Jesus what he must do to inherit eternal life. “Thou knowest the commandments,” Jesus replies.

Rieff calls this a “liberating dynamic of submission” and suggests “soul making” as a synonym for the kind of charisma he defends. The discipleship (striving toward God) that exists in a charismatic Christian community has nothing in common with the conformity (following orders) that characterizes modern mass organizations. United in their submission to the sacred, the members of a chain of belief teach through the act of keeping the commandments and learn through imitation — there is no master-slave relation. Such a sacred order is less likely to be corrupt, because it “constantly resists being made convenient for the cadres who come to administer the creed.”

Rieff’s point is that we in the modern West have lost the sense of the holy. When we lose holy terror — the fear of the Lord — we set our own inner demons free. Mythology tells us that nemesis must inevitably follow this hubris.

So, yes, let The Benedict Option be thought of as “reactionary” in the sense Caldwell means. Let us Christians submit “to the existing covenant in ways that provoke imitation” — that is, let our lives be our witness to the truth of our faith. Let us refuse the fake Christianity that is MTD within our own traditions, and return to the faith of our fathers. Doing so, as the church historian Robert Wilken has said in this extremely important 2004 essay, requires this of us:

Nothing is more needful today than the survival of Christian culture, because in recent generations this culture has become dangerously thin. At this moment in the Church’s history in this country (and in the West more generally) it is less urgent to convince the alternative culture in which we live of the truth of Christ than it is for the Church to tell itself its own story and to nurture its own life, the culture of the city of God, the Christian republic. This is not going to happen without a rebirth of moral and spiritual discipline and a resolute effort on the part of Christians to comprehend and to defend the remnants of Christian culture.

His point is that we Christians today have ourselves lost our narrative. We cannot give the world what we do not ourselves have. Wilken’s is a cause for a return to inwardness, precisely so we will regain the story that can liberate the world when we go out into it.

Where does this leave the Telos Crisis identified by Brooks? I don’t know, but more to the point, I don’t care about it as much as I used to. I don’t believe there will be any national rediscovery of a telos, because the nature of modernity, including our consumerist popular culture, is anti-teleological. This is what it means for the therapeutic to triumph. How is civics education going to produce a narrative stronger than “Ye shall be as gods”? Stronger than “ye shall create your own truth, and you will use it to set yourself free”? How can a patriotic narrative speak transformatively into the lives of people raised in the social catastrophe (including fatherlessness, drug addiction, violence, community dissolution) that has become domestic life in so many parts of America? Aside from a dramatic rebirth of Biblical religion, where will Americans find the courage and inspiration to stand together against the intoxicating narratives of identity politics, of both the left and the right?

Religion is no guarantee of anything. A friend of mine, an observant conservative Catholic, is fighting to rescue his teenage son from far-right, conspiracy-driven hatred — malevolent ideas he acquired from his friends at school. But if not religion — a religion not of moralistic therapy, but of holy terror (in the Rieffan sense) — then what? There is nothing else.

Alasdair MacIntyre:

A crucial turning point in that earlier history occurred when men and women of good will turned aside from the task of shoring up the Roman imperium and ceased to identify the continuation of civility and moral community with the maintenance of that imperium. What they set themselves to achieve instead—often not recognising fully what they were doing—was the construction of new forms of community within which the moral life could be sustained so that both morality and civility might survive the coming ages of barbarism and darkness.

If America — and the West — is to be saved, it will be saved as St. Benedict and the Church saved the West for Christianity after Rome’s fall: by the slow, patient work of fidelity in action. The most patriotic thing believing Christians can do for America, then, is to cease to identify the continuation of civility and moral community with the maintenance of the American order, and instead focus our efforts on strengthening our communities. It begins by re-learning our story, and regaining a sense of the holy. All the rest will follow, in God’s time.

This does not require us to turn our backs on our neighbors — indeed, I don’t see how any Christian can justify that. It does mean, however, that to the extent that engagement with the broader world compromises the telling of our Story to ourselves, and embodying that story in practices, both familial and communal, we must keep our distance. My point here is not that we should cease to love America, our home, but simply that the sickness that has overtaken our country, a sickness that has stolen our sense of common national purpose, is quite possibly a sickness unto death.

Can it be healed? Maybe. But it will take strong medicine — medicine that only the church can offer, once it has healed itself from the same disease. I fear we Christians, and we Americans, have entered into the era described by the ancient Roman historian Livy, remarking on his own society: “We have reached the point where we can tolerate neither our vices nor their cure.”

March 20, 2017

Ben Op Miscellany

On sale Tuesday March 14

A few notes from the most recent commentary on The Benedict Option. Don’t worry, brethren and sistren, if this is boring you, it’ll be going away soon. I can’t possibly respond to everything written about the book, nor should I, but I do want to remark on a few things that caught my eye.

First I’d like to thank my friend Alan Jacobs for his thoughtful critique in First Things. Excerpts:

Therefore, to argue, as many have, that the argument Rod Dreher makes in The Benedict Option is despairing, and hopeless, and a failure to trust in the Lord Jesus, is a category error. It takes a set of sociological and historical judgments and treats them as though they were metaphysical assertions. Anyone in Roman Cappadocia who had said that the culture Basil and his colleagues had built was not bound to last until the Lord returns would not have been deficient in Christian hope. Rather, he or she would have been offering a useful reminder of the vagaries of history, to which even the most faithful Christians are subject. Dreher’s argument in The Benedict Option may be wrong, but if so, it is wrong historically and prudentially, not metaphysically.

So the whole debate over The Benedict Option needs to be brought down out of the absolutist clouds and grounded in more historical particularities. However, and alas, this is something that neither Dreher nor his opponents seem inclined to do. Almost every party to this dispute seems to be painting with the broadest brushes they can get their hands on. Thus Dreher: “It is time for all Christians to pull their children out of the public school system.” All of them? Without exception? No room for familial discernment and prudential judgment? And from the other side, here’s the verdict of one of Dreher’s more thoughtful critics, Elizabeth Bruenig: “Building communities of virtue is fine, but withdrawing from conventional politics is difficult to parse with Christ’s command that we love our neighbors.” We can’t love our neighbor without voting? The hospice-care worker who is too busy and tired to get to the polling place is deficient in charity? Such an argument would seem to delegitimate most monastic ways of life, which makes it an odd position for a Catholic of some traditionalist sympathies, like Bruenig, to make.

This is really helpful. Alan has put his finger on what I probably regret most of all in the book, in the sense that I would phrase it more carefully if I had it to do over again: the line about public schools. I know that it is simply not possible for very many good people to do anything other than send their kids to public school. And speaking for myself, there are some places in which I would choose a public school over a private school. It is not fair to generalize, and I did generalize, and am sorry about that. It really is a matter of prudential judgment. If it were left up to me and me alone to homeschool, I would have my kids in a public school in two shakes of a lamb’s tail. I don’t have that gift, and even if I did, it’s easy to imagine a situation in which my family could not afford it. So, I retract that harsh statement.

More Jacobs:

The sociologist James Davison Hunter has rightly said that Christians in general should strive for “faithful presence” in the public world, and there are, sad to say, multiple ways to fail at this task. One can spend so much time focusing on one’s faithfulness that one forgets to be present, or be sufficiently content with mere presence that one forgets the challenge of genuine faithfulness. It is also possible to conceive of “presence” too narrowly: again, I would contend that the hermit who prays ceaselessly for peace and justice is present in the world to an extent that few of the rest of us will ever achieve. But that said, and all my other caveats registered, I suspect that if American Christians have a general inclination, it is towards thinking that presence itself is sufficient, which causes us to neglect the difficult disciplines of genuine Christian faithfulness. This is certainly what the work of Christian Smith and his sociological colleagues—on which Dreher relies heavily—suggests.

And that is reason enough to applaud Dreher’s presentation of the Benedict Option, because his portraits of intentional communities of disciplined Christian faith, thought, and practice provide a useful mirror in which the rest of us can better discern the lineaments of our own lives. A similar challenge comes to us through Charles Marsh’s 2005 book The Beloved Community, which presents equally intentional and equally Christian communities, though ones motivated largely by the desperate need in this country for racial reconciliation. To look at such bold endeavors in communal focus, purpose, and integrity is to risk being shamed by their witness.

If we are willing to take that risk, we might learn a few things, not all of them consoling, about ourselves and our practices of faith. And our own daily habits are where the rubber meets the road, not in abstractions about liberal subjects and the decline of the West.

This is really good, and I hope you’ll read the entire essay. I’m happy to tell you that the book itself is much more focused on everyday practices and disposition than you might think.

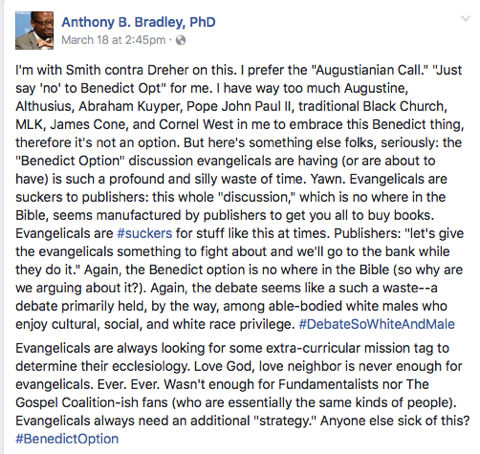

At the complete opposite end of “thoughtful” and “helpful” is this insufferably trite Facebook post by the Christian college teacher Anthony B. Bradley, PhD:

Oh, brother. So the Ben Op is a cynical ploy to make money by white people blind to their own privilege. Golly. This is no more persuasive than when James K.A. Smith made the same allegations on the Washington Post‘s website last week, but at least his had the virtue of being coherent and original to its (sadly misguided) author.

“Again, the Benedict option [sic] is no where [sic] in the Bible (so why are we arguing about it?).” Seriously? A tenured professor is actually saying this? Perhaps I lack a good concordance, but I have not seen Cornel West’s name in Scripture. Besides, Anthony B. Bradley, PhD, does not give any indication of having read a single word of the book. One gathers that Anthony B. Bradley, PhD, is not accustomed to knowing what he’s talking about before he speaks. Nice work, if you can get it.

Secondly, this “white, able-bodied male privilege” stuff is what weak-minded people say when they don’t actually have an argument. Charles J. Chaput, the Roman Catholic Archbishop of Philadelphia and one of the most significant figures in the US Catholic Church, is talking about the Benedict Option — and lo, he is a Native American. Are Native Americans too white for Anthony B. Bradley, PhD? Since when does Anthony B. Bradley, PhD, decide who is white, and that color, sex, and the ability to walk determines whether or not one has the right to discuss ideas, or whether or not ideas are worth discussing?

I think Anthony B. Bradley, PhD, is trying to evade grappling with ideas he thinks he won’t like, and is trying to score Social Justice Warrior virtue points in so doing. Let’s just consider briefly the comedy of a holder of a PhD who teaches in Manhattan lecturing anybody else about privilege. Plus, does he really want to accuse the Bruderhof, a pacifist Christian group whose members all live modestly, under a vow of poverty, that they have no business talking about the Benedict Option because their members are mostly white, and half male? Additionally, I’m hearing from white fathers and mothers who are struggling to deal with their Christian high school sons watching pornography on iPhones, and in one heartbreaking case, a son being drawn into white nationalism and anti-Semitism through the things he’s being exposed to in his public school peer group. They’re reading The Benedict Option looking for answers. I will be sure to tell them that their problems aren’t real, because Anthony B. Bradley, PhD, a tenured professor at a New York City college, says that they’re white and privileged. That should settle that.

Returning to the real world, here’s a link to a big Colson Center symposium on the Ben Op, featuring some big names in Evangelicalism. I can’t respond to all of them, but I wanted to speak to a few things mentioned in it.

Greg Forster writes:

Darrow Miller of Disciple Nations Alliance is right: “If the church does not disciple the nations, the nations will disciple the church.” God’s people are distinct from the world, but they must practice their discipleship in the daily lives that they live within their nations—or else not at all. God has made us social creatures, and we are formed as people and as Christians by our inescapable membership in our nations.

This is why we must overcome the dangerous illusion expressed in Dreher’s call to cease “full participation in mainstream society.” The illusion is not that such a withdrawal is desirable. The illusion is that such a withdrawal is even possible. To be human is to be part of a nation, and when believers try to withdraw into “Christian villages” they only reproduce in miniature the dysfunctions of their nations—because that is who they are. Transformation is needed, but withdrawal does not transform. Instead, as we saw at Pentecost, by the supernatural power of the Holy Spirit, the gospel is now to be expressed within the daily life of all the world’s nations. We must rely on the Holy Spirit to make us disciples in our daily lives as Americans—for we have no other lives to live.

I wonder if people who write things like this actually read my book. Anybody who did would know perfectly well that I call for partial withdrawal for the sake of being able to bring the light of Christ fully to the world when we do engage. I don’t know how many times I have to say it. But look, if the strategy that we have been undertaking is working so well, how come the overwhelming number of Christian kids don’t know their faith? How come the Church looks so much like the world? How come so many Christian teenagers captured by pornography addiction?

Why do so many Christian leaders have trouble recognizing that what they’re doing is not working? It has been 12 years since Al Mohler wrote this terrific column about Christian Smith’s then-new study about Moralistic Therapeutic Deism. In the much-discussed column, he wrote:

All this means is that teenagers have been listening carefully. They have been observing their parents in the larger culture with diligence and insight. They understand just how little their parents really believe and just how much many of their churches and Christian institutions have accommodated themselves to the dominant culture. They sense the degree to which theological conviction has been sacrificed on the altar of individualism and a relativistic understanding of truth. They have learned from their elders that self-improvement is the one great moral imperative to which all are accountable, and they have observed the fact that the highest aspiration of those who shape this culture is to find happiness, security, and meaning in life.

This research project demands the attention of every thinking Christian. Those who are prone to dismiss sociological analysis as irrelevant will miss the point. We must now look at the United States of America as missiologists once viewed nations that had never heard the gospel. Indeed, our missiological challenge may be even greater than the confrontation with paganism, for we face a succession of generations who have transformed Christianity into something that bears no resemblance to the faith revealed in the Bible. The faith “once delivered to the saints” is no longer even known, not only by American teenagers, but by most of their parents. Millions of Americans believe they are Christians, simply because they have some historic tie to a Christian denomination or identity.

We now face the challenge of evangelizing a nation that largely considers itself Christian, overwhelmingly believes in some deity, considers itself fervently religious, but has virtually no connection to historic Christianity. Christian Smith and his colleagues have performed an enormous service for the church of the Lord Jesus Christ in identifying Moralistic Therapeutic Deism as the dominant religion of this American age. Our responsibility is to prepare the church to respond to this new religion, understanding that it represents the greatest competitor to biblical Christianity. More urgently, this study should warn us all that our failure to teach this generation of teenagers the realities and convictions of biblical Christianity will mean that their children will know even less and will be even more readily seduced by this new form of paganism. This study offers irrefutable evidence of the challenge we now face.

Things have only gotten worse for all churches since then. We might be producing churchgoers and youth-group members, but we are not producing disciples.

In the symposium, my friend Peter Leithart writes:

My question is, for what tale is the BenOp the moral?

Some church fathers feared the end of Rome was the end of the world. Augustine saw Rome as an episode in the bigger story of the civitas Dei, which, Augustine believed, would flourish in her pilgrimage, empire or no empire. I suspect St. Benedict agreed.

Rod knows this. He believes in creation, cross, and eschaton. Yet, though his book gestures toward this biblical story, the BenOp is the moral to a story of Western decline. Despite Rod’s cautions, it tends to treat the church as a helpmeet of American renewal. It’s an agenda to “save the West.”

The Benedict Option aims to escape the imperial project. I worry that Rod is still in thrall to the imperial narrative.

I disagree. As I write in the book:

We are not trying to repeal seven hundred years of history, as if that were possible. Nor are we trying to save the West. We are only trying to build a Christian way of life that stands as an island of sanctity and stability amid the high tide of liquid modernity. We are not looking to create heaven on earth; we are simply looking for a way to be strong in faith through a time of great testing. The Rule, with its vision of an ordered life centered around Christ and the practices it prescribes to deepen our conversion, can help us achieve that goal.

Though I don’t welcome its fall, I don’t think the Empire can be saved. My book is about the need for Christians to stop considering Christianity as co-extensive with the American (and Western) social and political order. This is what Alasdair MacIntyre suggests in the quote that forms one of the pillars of the book. The basic premise of the Benedict Option idea is that St. Benedict did not set out to Save Western Civilization™, but only to be faithful to Christ in a very difficult and chaotic time. But over the next few centuries, his successors did precisely that, as a secondary effect of evangelizing and civilizing barbarian Europe. If we are to be new — and very different — St. Benedicts, we have to first seek to follow Christ in our lives, in concrete and enduring ways. Maybe the Western order will be saved. Maybe a new Christian order will grow out of it. Or maybe this will be the end for us, and the Church will continue to flourish in parts of the world where the Holy Spirit is welcome. That’s beyond our ability to control. We have to get about the business of figuring out ways to be more faithful right here, right now. What we’ve been doing isn’t working.

(And by the way, when I talk in the book about the value of Western civilization and the need to preserve memory of it, I’m talking about the best that has been said, written, drawn, sculpted, spoken, and composed within the vast Western tradition, which, note well, precedes the advent of Christianity. None of that is the Gospel, granted, but it’s not butterbeans either. I’m sure Peter agrees, but I want to make that clear. Christianity has been articulated in cultural forms for nearly two millennia. It is important to remember that, and to remember them.)

In the symposium, Gerald McDermott writes that he and his wife used to live in a intentional Christian communities, but found them to be too confining. I suspect I would feel exactly the same way! The Benedict Option does not prescribe them for all Christians (and neither does the intentional community movement called the Bruderhof, as I learned this weekend). McDermott adds:

But with all of those qualifications, I think the Benedict Option is something Christians need to consider. If the communal lifestyle is not for all believers, it is surely imperative for us to strengthen the Christian family and church community life. My wife and I have found it immeasurably rewarding to participate in daily liturgy (morning and evening prayer using the Daily Office) and the sacraments, weekly at a minimum and daily if possible.

I think starting a book group across denominational lines, and studying a Christian classic, is ideal. Get back to the Fathers. Read Augustine or Athanasius or Gregory together. This is a sure remedy to the shallowness and heresy of too much of today’s Church.

Yes! Terrific. And my pal Karen Swallow Prior nails it:

“The Benedict Option’s” vision is not to make nuns and monks of modern Christians. Nor does it propose a bunker (whether literal or figurative) from which to establish merely an updated version of the fundamentalist separatism of yore. Nor is the turn to Benedict a quixotic attempt to recapture a romanticized past.

To the contrary, “The Benedict Option” calls Christians wherever they live and work to “form a vibrant counterculture” by cultivating practices and communities that reflect the understanding that Christians, who are not citizens of this world, need not “prop up the current order.” While the monastery that birthed the Benedict Rule was literal, the monastery invoked in “The Benedict Option” is metaphorical. It is not a place, but a way.

That’s very well said: “not a place, but a way.”

John Mark Reynolds, another friend of mine, has a powerful statement in the symposium:

The Benedict Option is not a way, but the only way forward for Christians who wish to be more than nominal in their faith. Christianity does not say that Jesus is Lord of part of human life, but of all of human life. We cannot give our entertainment, our work life, or our social lives to secular Caesars and expect to handle the holy things of the church.

Critics of the Benedict Option do not grasp that an alternative city can be Constantinople and not just a monastery or a village. Christians can live quiet lives, but also build an alternative to a Rome intent on barbarian rule. If Rome is unlivable for Christians, then we will make political allies where we can and build a new and better Rome.

Once, the strategy of a Constantine with a Benedict option saved Roman and Greek civilization for 1000 years, so now perhaps a Constantine strategy with a Benedict Option can do the same for American culture. If we cannot defend the old order, or if the decadent elite no longer wants us, then we can empower something new.

Let’s see how it goes. Leave us alone and the cross will triumph. This will not be by might, military power, but because of the Spirit of God. We are not withdrawing, we are rebuilding. Education, for example, can be offered that is high quality, does not require high debt, and is integrated into the family, church, and community.

In the book, I talk a bit about The Saint Constantine School , an innovative classical Christian educational institution John Mark has helped found in Houston. It is a model for all of us going forward.

Roberto Rivera — seems like I’m friends with a good number of the people in this symposium — offers a critical perspective, slighting the book because “there is virtually no acknowledgement that American Christianity is more than—I grow weary of being ‘that guy’ who points this out—what White Christians are doing.” More:

This isn’t “identity politics” or, even worse, “political correctness.” As Ed Stetzer and Leith Anderson wrote at Christianity Today, African-Americans are substantially more likely (60 percent) to hold Evangelical beliefs than non-Hispanic whites, and Hispanics are as likely, if not a little more, to hold such beliefs as their non-Hispanic white counterparts.

Add the impact of immigration, Hispanic and otherwise, on American Catholicism, and the absence of “non-white” American Christians from Dreher’s narrative becomes a kind of dog that didn’t bark in the night.

Well, my book is sweeping in scope. I didn’t even get down to examining the nitty-gritty of various strands of American Christianity, in terms of fidelity to Biblical and historic Christian orthodoxy. My Evangelical friend Anne Snyder told me last week in Washington that living in Houston these past few years has revealed to her a world of strong religious engagement within immigrant churches. That’s great news! I told her I hope she (or someone else) writes about it in a Benedict Option vein, e.g., what those churches have to teach the broader American church.

I wonder, though, how the practices of Latino and African-American Christians as a whole differ from their stated beliefs. I’m recalling a conversation with a black Christian friend last year. She told me she was raised in a very strict Pentecostalist sect of the black church, and that in her family, they all professed belief in a strongly conservative Christianity. But none of them lived by it. Similarly, last week I talked to a middle-aged black man here in Baton Rouge who had fallen away from the church. He told me that he was raised in the black church, and left in disgust at the hypocrisy all around him. They said one thing, but did another, he said. He was still angry about it. My point simply is that it’s not enough to rely on what people say they believe, but we also have to see fruits of that belief in discipleship.

Finally, a bit from friend John Stonestreet’s comments:

The most important contribution of the Benedict Option is clearly articulating the powerful ability of culture to shape our hearts and minds. Too many of us are like the fish who don’t know they are wet. And so, Rod rightly says, we need “thick ties” to our fellow Christians and institutions, and especially to our churches.

This seemingly obvious point is, in my view, Dreher’s other very important contribution. If Christians are truly to be the church in this cultural moment, churches must become institutions that shape both who and whose we are. Pastors, parents, mentors, and educators must see education and discipleship as more than instructive. They must commit to establishing identity and loyalty.

I thank John for putting together this symposium — read everybody’s remarks here — and thank the contributors.

I really loved Gerald Russello’s extremely generous evaluation of the book in Intercollegiate Review. Excerpts:

This is our cultural moment, despite who occupies the White House or Congress, and with his unerring cultural radar, Dreher has written the book for this new moment: a central point in The Benedict Option is “put not your trust in princes.” Culture is more important than politics, and the currents of modernity did not change on Election Day. And one thing conservatives, and especially Christian conservatives, should understand is that they have lost the culture war, and, indeed, it was their obsession with politics—and their assumption that the culture and major institutions such as big business would always support them—that partially caused that loss.

More:

The Benedict Option is depressing and exhilarating by turns, sometimes on the same page. Depressing because Dreher shows how far we have fallen and how much work there is to be done, made more so because the cultural issues he describes are at times very personal, which affect every family in America. As a father in a post-Christian world, the stress and real presence of spiritual danger can be almost overwhelming. But the book also proves exhilarating because Dreher reminds us of the great history of Christianity in sparking renewal, and shows us how it is being done, today, now, in our own communities if we have but eyes to see. Hope, in the end, remains our most important cultural inheritance. In the catacombs of ancient Rome, in the Soviet-era Eastern Bloc, and in places like China today, the Church has modeled a society that is a witness to a different kind of polity. It is that moment again.

Read the whole thing — it’s one of the very best things I’ve seen yet on the Benedict Option. And so is this wonderful piece on the Evangelical college ministry website Campus Parade. Excerpts:

Of course, the success of the Benedict Option is also due to its timing. Though Rod alluded to the Benedict Option ten years ago in his book Crunchy Cons, I don’t know if most Christians would have been ready. Anyone who read Lesslie Newbingin 40 years ago, or Missional Church almost 20 years go will know the diagnosis of the decline of Christianity in the United States, but during these ten years since Rod mentioned the need for a new Benedict, so much has happened. The Millennial generation has shifted to the left on social norms and politics, marginal issues like same-sex marriage and transgender rights have become new norms, businesses have become arbiters of family values, sports is a tool for cultural enforcement, and what was once considered out-of-control political correctness on our campuses is now ubiquitous. I don’t need an academic to explain it to me, I see it everyday.

But there are other forces at work too. Technology like the internet and cell phones have brought us amazing amounts of information, but the ability to literally spend our whole lives on pointless trivia. The “authentic self” that philosopher Charles Taylor wrote of in his masterpiece The Secular Age, reached its apogee in Caitlyn and Bruce Jenner. Bruce Jenner, a Cold War hero to us in Generation X, became a cause celeb to Generation Z as Caitlyn Jenner. Transpose that Wheaties picture of Bruce in 1976, winner of the Olympic decathlon and “world’s greatest athlete” with Caitlyn on the cover of Vanity Fair, and you see trajectory of where we are headed as a nation.

As Christians we did not want to believe the academics. Developing as a nation under the canopy of our country as a “city on a hill” from John Winthrop’s sermon A Model of Christian Charity, we always told ourselves we could “go back” to ideal times. Revivals did help, and many truly believed that with the right focus on the right segments of society, we could still transform the culture. But we finally find ourselves “strangers in a strange land” to steal a line from Robert Heinlein.

More:

[The Benedict Option] is the challenge of taking personal counter-cultural steps in our lives to form Christian communities that will be receptacles and transmitters of civilization and Christianity to a dark age all around us. It is something we must prepare for the long-term. There will be no quick fixes and early time lines. As Rod says in his book “the new order is not a problem to be solved but a reality to be lived with.”

With chapters dealing with politics, church life, Christian communities, education, work, sexuality, and technology, Dreher sketches broad outlines of what needs to happen in each of these areas to preserve some vestige of Christian normalcy. These outlines help us see how we need to find new ways of evangelism that highlight beauty and authenticity of life; show the goodness of God in understanding a biblical version of marriage, sex, and family; bind ourselves together in deeper relationships; value the life of the mind through Christian education; see work as a Christian calling; know the limits of technology and attempt to find space to enjoy nature, solitude, and contemplation; and open our hearts to God through new liturgies of prayer, fasting, and repentance. How these sketches are colored in is up to each individual, family, church, and community.

But they are provocative sketches. They make us think of what could be if we take action, and what we lose if we fail to act. They make us want to talk with someone about their “rightness” and see where the discussion could lead. I hope you will get a copy of The Benedict Option, read it, pass it on to a friend, family or church member, and talk about it. Debate it. Color in the details of those sketches. Then get out your tools and start building an ark.

I’m going to stop here, even though I have four more pieces I’d like to comment on open on my browser. I’ll get to them tomorrow. Let me say that even if people dislike or hate these ideas, I am thrilled that the church is talking about them. I don’t have all the right answers, but in The Benedict Option, I hope I am asking the right questions. If the answers are going to be found, we Christians are going to have to find them together.

You Will Be Made To Watch

Erick Erickson has a great line about the culture war: “You will be made to care.” He means that the left will never content itself to live and let live.

YouTube said on Sunday that it was investigating the simmering complaints by some users that its family-friendly “restricted mode” wrongly filters out some lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender videos.

The statement came after the video-hosting platform faced growing pressure over the weekend from some of its biggest stars to address the issue.

In a statement, YouTube said that many videos featuring lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender content were unaffected by the filter, an optional parental-control setting, and that it only targeted those that discussed sensitive topics such as politics, health and sexuality.

But some of the video creators disagreed, pointing to blocked content that they argued were suitable for children of any age and did not discuss such subjects. They also said that the filtering shields lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender children from the resources and support the videos can provide.

It is not the right of a transgender person or anyone else to decide what someone’s children can and cannot watch. That decision belongs to the parents. But see, this is par for the course for the left, especially the sexual left: disempower parents so they can propagandize children.

Christian and other conservative parents, if you let your kids watch YouTube without you at their side, you’re crazy. Seriously, you have no excuse.

UPDATE: A reader writes:

Saw your post. Made me think about pro-LGBT parents wanting to filter out religious messages that condemn homosexual conduct and extol the virtues of celibacy for same-sex attracted people who believe that I can change. Even though I think that makes them narrow-minded, I see no reason why YouTube should not accommodate them. In fact, I would defend their right to do this, since I believe that parents have a special responsibility to their children that third parties have no right to breach (except for in very narrow circumstances).

LGBT activists for years made fun of “they’re coming for your children” rhetoric of the religious right. Turns out the religious right was correct; they are coming for your children, and they resent the fact that you’re trying to block the door.

Life Among The Bruderhof

Have you ever heard of the Bruderhof? It’s an international movement in the Anabaptist tradition. They are Christians who live in intentional communities — 23 of them, on four continents — and share their lives and resources in common. Here’s an FAQ about them. And here is a more in-depth exploration of those things, in what could be titled the Rule of the Bruderhof. The movement was founded in 1920 in Germany, as a Christian response to the horrors of World War I and social injustice. They eventually had to leave Germany because of Nazi persecution.

Late last week, I visited two of their American settlements, Fox Hill and The Mount, both not far from each other, in New York’s Hudson River Valley (see a list of all the US Bruderhof communities here.) The Bruderhof has been fully engaged with The Benedict Option book (start here to see what they think of it). After spending some time with them, it’s very easy to see why. The Bruderhof has been living their version of the Benedict Option for almost a century. These two communities are full of grace and hospitality. Before I say anything else, let me encourage you to check out this link telling you where all of the Bruderhof communities are worldwide. There’s nothing like a visit to meet them yourself. This short video gives you an idea of what to expect:

I stayed at Fox Hill, a community of large, multifamily houses and buildings, including a workshop, a primary school, and a chapel/meeting room, spread across rolling farmland. Shortly after arriving from NYC with others for a Ben Op conference there (all off the record, alas), we all gathered with the entire community for a welcome. They sang several hymns. What startled me, and delighted me, was the joyful force with which they sang. I’ve never heard anything like it in a Protestant, Catholic, or Orthodox church. It was genuinely inspiring. As with so much I saw there, it’s not my tradition, and it’s not one I’m particularly drawn to, but it’s impossible not to admire the Bruderhof.

The Bruderhof folks live radically compared to other Christians. They really do hold all things in common, meaning that nobody receives a paycheck. That requires an unusual degree of trust, obviously, but you also get a lot in return. The community cares for you. They don’t let anybody suffer. They don’t warehouse their elderly in nursing homes, for example. To join the Bruderhof, you first have to live in a community for at least a year, in a novitiate — a time of testing to see if you can live by the rhythms and commitments of the community (monastic orders have this too). They want people to be sure that this life is for them. If, after the novitiate, an adult wants to join, he makes vows in front of the entire community. In general, they are vows of poverty, chastity (including fidelity in marriage), and obedience (here are the particular vows). It would not be stretching it to call them lay monastics.

They have families, but children aren’t automatically members of the Bruderhof for life. They can go to college if they like, and many do, and they do not have to embrace Bruderhof life if they don’t feel a calling to it. I talked to one man who said that he had been raised in the Bruderhof, but left it for a while. After some time, feeling far away from his own, he sold all his possessions and bought a train ticket back to a Bruderhof settlement. Now, he’s happily married. “I still have my train ticket,” he told me, saying it was one of the best decisions he ever made.

I don’t think I had any particular expectations about what I would see at Fox Hill and The Mount, but I can tell you this: it’s not like M. Night Shymalan’s The Village. You may laugh at that, but I swear, so many people seem to think that if you live in any kind of Christian community that separates itself to a meaningful degree from the world, you’re bound to turn into a freakfest. The Bruderhof people are so blessedly normal. If anybody finds them freaky, that is a judgment on that person, not on these Anabaptists. If what they have is freaky, then the world needs a lot more freaks.

The most amazing thing to an outsider’s eyes — well, this outsider’s eyes — are the Bruderhof’s kids. None of them walk around with their eyes glued to screens. They don’t have that shifty, unsettled look that so many kids do. They look grounded and happy. They actually play outside, and do chores, and talk to each other. Every single one of these kids I talked to spoke to me politely and with confidence, even though I was a stranger to them. They seem so mature and grounded. That’s the thing that has lingered on my mind since coming home: the witness of the Bruderhof children. Everybody wants to have boys and girls who are like that, but so few of us are willing to make the sacrifices that those parents do to raise them.

Someone in the community there told me that the Fox Hill Bruderhof used to send its teenagers to the local public high school, but they had to pull them out because the moral effects on their kids was destructive. In 2012, the movement bought a massive seminary built in 1907 on the banks of the Hudson by the Redemptorist order of Catholic priests. By the time the Bruderhof entered the picture, the building was in bad shape, and was home to only four elderly Redemptorists. The Anabaptists bought it and renovated it as both a high school for their community (and some kids outside the community), and as living quarters for a large number of families. It’s called The Mount, and I visited it.

Here’s a photo I took of the building:

It’s enormous! It stopped me in my tracks to imagine that there was a time in US Catholic history when a religious order felt confident enough in its future to erect a building longer than a football field, to educate its priests. And now it is home to a colony of Anabaptists, of all people! You just don’t know the way history is going to flow, do you? The Bruderhof folks have been respectful of The Mount’s Catholic heritage, and have left its chapel largely intact. It struck me that it’s a great blessing that this building, which was erected to form missionaries for the Gospel, was not sold to some hotel chain, but is forming new — and very different — missionaries for the Gospel.

I had dinner with a Mount family, and we talked about what the Bruderhof has to offer the rest of the Christian world in the Benedict Option. “If you write about us,” said my host, “please write that we don’t seek imitation, but rather are trying to be an inspiration.” He explained that theirs is just one way to live out the Gospel in a radical way. If they have something to offer others, then they’re happy to share freely. They are seeking to get to know believers from other traditions, to share friendship, and to figure out if it’s possible for us to support each other?

What do I think the Bruderhof have to offer the rest of us?

First, the idea that this kind of life is possible, even today. They do live separate lives, but they aren’t strict separatists. For example, they invite their neighbors outside the community to come over for a common meal on Saturday nights. The members all work in the community, but they do go out into the world. Again, they sent their kids to the public high school, until they concluded that the moral culture had degraded so much that it was too risky to subject their kids to it. They didn’t have an objection in principle to public school, but when it reached the point of interfering with the life they believe God has called them to live, they pulled out, and started figuring out how to do something better. All Christians can admire the sacrifices they were willing to make for their kids.

Second, the example of their children. I had just spent a good part of the week talking to different people out in the world about how damaged kids today are by constant exposure to electronic media, as well as by the deforming aspects of popular culture. These kids are the polar opposite from that! They are wholesome, because they were raised by a community that was determined to raise them in a wholesome environment. You can tell it. Boy, can you ever. I was up for 6:30 am breakfast on Saturday, after which I had to go to LaGuardia for the flight home. It was 15 degrees outside. The oldest boy in the family finished breakfast and went to join other boys in cleaning the community’s cars — on this cold, cold morning. The other kids prepared for their Saturday chores (e.g., the girls were going to be helping their mother clean the house). I heard not a single complaint, or the least bit of whining. They just … did it, and did it not out of fear or anything like that, but because, well, that’s just what you do at the Bruderhof to make our community work.

Again: if this is freaky, the world needs a lot more freaky.

Third, confident outreach to other Christians. They can do this because they know who they are and what they believe — and they’re not mad about it. Nobody tried to talk me into becoming an Anabaptist. The only conversations I had were along the lines of, “Now, tell me what you Orthodox do when you worship?” and “How can we be your friends and your servants?” Just straightforward, plain dealing, in charity and a spirit of service. We need more of that.

Fourth, the value of simplicity. Anabaptists are very, very simple in their piety and worship. They don’t really have a liturgy. As an Orthodox Christian, I am their polar opposite when it comes to liturgy and ecclesiology, but I’ll say this for them: these are not people who are given over to innovation and trendiness in worship. Even though I was there for only a short time, I could discern how the Bruderhof weaves worship into all of life, and thus makes their entire existence a simple but effective liturgy of life.

Fifth, demolishing the concept of compartmentalization. For the Bruderhof, there is no separation between religion and life. You live your faith wholly, not just on Sundays. It’s supposed to be like that for all of us believers, but we so often fail at it. The Bruderhof has created social structures, customs, and institutions that make this easier to do.

It’s not hard to find material online criticizing the Bruderhof, written by ex-members. I wouldn’t claim that they are perfect, ever, and certainly wouldn’t make that claim after a very short visit. But I came away from my visit there inspired, not only by the Bruderhof itself, but by the possibilities of life and ecumenical cooperation in the Benedict Option.

One last image: as I was touring the primary school on Friday morning, I poked my head into the room where toddlers are watched. I saw a little boy sprawled out on the lap of a Bruderhof woman, who cradled him in her arms.

“Oh, that beautiful child,” I said. “He’s sleeping.”

“No,” said my guide. “He has cerebral palsy.”

That child abides in the cradle of a community that loves him and his parents. That child abides in grace and light.

Hillbilly Benedicts

J.D. Vance (via JDVance.com)

If you’re in New Orleans on April 17, come see J.D. Vance and me onstage at UNO talking about faith and politics. Details:

The discussion, “Faith, Hillbillies, and American Politics: An Evening with J.D. Vance & Rod Dreher,” will begin at 6 p.m. in the Geoghegan Ball Room of the Homer L. Hitt Alumni Center at UNO’s campus, 2000 Lakeshore Dr. in New Orleans, following a reception in the Alumni Center lobby beginning at 5:15. This event is free and open to the public.

I predict that there will be a Ken Bickford sighting too. Look for the seersucker.

Your Working Boys, on Canal Street

Benedict Option: ‘Dark Mountain’ For Christians?