Rod Dreher's Blog, page 473

March 31, 2017

Stoicism, Percy, Benedict

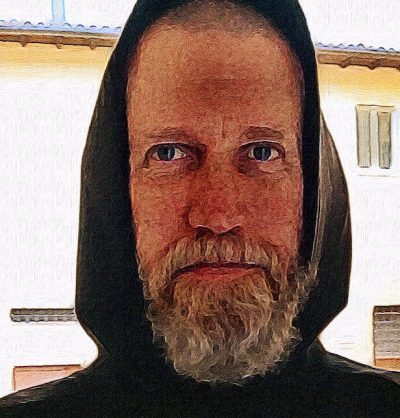

Your Working Boy, Peter Augustine Lawler, and James Patterson, at LSU last weekend.

Last week I was at the Ciceronian Society conference in Baton Rouge, and unforgivably failed to have a conversation with Peter Lawler in the hospitality suite. Never did get past great conversations at the bar. Here’s a short piece Peter wrote about the Benedict Option, Walker Percy, and American Stoicism. Excerpt:

It was inevitable that I was asked what I thought of Rod’s fine (and hugely successful) new book on the BO. Well, for one thing, our country can always use more BO, which means more people living like the Benedictines and more people living in highly civilized, highly relational, countercultural ways in general.

Now, a dumb thing I said is that Walker Percy liked and I like TV too much to be whole-hog on the BO front. But, you know, it turns out that Percy was an oblate (or sort of fellow traveler) of the Benedictines of St. Joseph’s Abbey in his chosen home of Covington, La. And he’s buried on the grounds of that abbey.

Nobody thought more highly of the Benedictines than he did, although he wasn’t actually called to be one. So a more serious answer is that I thought that the BO often needs a dose of American Stoicism — or the virtues of magnanimity and generosity (and some honor in general) to supplement Christian love. That means, among other things, that people living the Benedictine Option aren’t absolved of their relational duties to the wider community and to their country. To some extent, the actual Benedictines can be given a pass, but their monasteries are single-sex and don’t include children.

You can read the whole thing, and should, but I await Peter’s promised follow-up, in which he explains what you might call The American Stoic Option. (The Uncle Will Option?) Peter writes:

Today, the option it presents is virtuous alternatives to the intrusive expert scripting of ordinary lives by Democrats such as Hillary Clinton, the demagogic populism that deforms Trumpism, and the oligarchic individualism of too much of establishment conservatism. For a primer on democratized Southern Stoicism, I suggest you review the fabulous TV series Friday Night Lights.

I want to know more. Come on, Peter, unpack that sucker! By the way, I cannot agree more strongly that everybody ought to watch Friday Night Lights, the greatest TV series ever made.

Hey, if you haven’t bought your tickets yet for Walker Percy Weekend (June 2-4), don’t miss out. They’re going fast. If you’re a Benedict Option reader, you’ll want to hear Ralph Wood lecture on Walker Percy and the Benedict Option. And if you are a reader of The World’s Largest Man, one of the funniest books I have ever read (not kidding!), then you will want to come hear author Harrison Scott Key talk about it and tell Southern stories.

I told Mama that she needed to read the Key book. She called last night to say that a) she killed a cottonmouth that was under her rocking chair on the front porch, and b) “I’m only twenty pages into that book, and I can’t stop laughing. Did you say that fellow was coming to Walker Percy Weekend? Oh, I’m so glad I bought a ticket!”

You will be too. Buy your tickets here.

The Pencing Of Ta-Nehisi Coates

A progressive man who respects his wife and his marriage too much to put it at risk ((92YTribeca/Flickr)

Hey Mike Pence haters, meet progressive superhero Ta-Nehisi Coates:I’ve been with my spouse for almost 15 years. In those years, I’ve never been with anyone but the mother of my son. But that’s not because I am an especially good and true person. In fact, I am wholly in possession of an unimaginably filthy and mongrel mind. But I am also a dude who believes in guard-rails, as a buddy of mine once put it. I don’t believe in getting “in the moment” and then exercising will-power. I believe in avoiding “the moment.” I believe in being absolutely clear with myself about why I am having a second drink, and why I am not; why I am going to a party, and why I am not. I believe that the battle is lost at Happy Hour, not at the hotel. I am not a “good man.” But I am prepared to be an honorable one.

This is not just true of infidelity, it’s true of virtually anything I’ve ever done in my life. I did not lose 70 pounds through strength of character, goodness or willpower. My character and will angles toward cheesecake, fried chicken and beer — in no particular order. I lost that weight by not fighting the battle on desire’s terms, but fighting before desire can take effect.

These are compacts I have made with myself and with my family. There are other compact we make with our country and society. I tend to think those compacts work best when we do not flatter ourselves, when we are fully aware of the animal in us.

Power changes people. People yell things from behind the shielding of their automobiles which they would never yell if walking down a sidewalk. This does not mean that power should be shunned; it means that we should be aware of its effects. I believe very much in self-defense, and totally understand why someone would keep a gun in the home. If I lived somewhere else, I might keep one too.

But I would not insist that I was the same person armed, with the power to take a life, that I was without it. I would insist on guard-rails.

[H/T: Reader Candles]

Deep Benedict

The altar of St. Benedict and St. Scholastica, in the crypt of the basilica in Norcia. This altar is now buried under rubble from the earthquake

Hey readers, I will be traveling today, to the Symposium on Advancing the New Evangelization, held this weekend at Benedictine College in Atchison, Kansas. I will be talking about — surprise! — The Benedict Option, and what Christians seeking to evangelize this post-Christian world can learn from the Benedictine monks.

As I was writing my speech, I revisited Chapter 3 of the book, which is its heart. It’s based on my visit to the monastery at Norcia, and my interviews with some of the monks there. It is predictable, I guess, but this has been the chapter that reviewers and commenters have focused on the least — even though it’s the most important one! Here’s an excerpt:

The next morning I met Father Cassian inside the monastery for a talk. He stands tall, his short hair and beard are steel-gray, and his demeanor is serious and, well, monklike. But when he speaks, in his gentle baritone, you feel as if you are talking to your own father. Father Cassian speaks warmly and powerfully of the integrity and joy of the Benedictine life, which is so different from that of our fragmented modern world.

Though the monks here have rejected the world, “there’s not just a no; there’s a yes too,” Father Cassian says. “It’s both that we reject what is not life-giving, and that we build something new. And we spend a lot of time in the rebuilding, and people see that too, which is why people flock to the monastery. We have so much involvement with guests and pilgrims that it’s exhausting. But that is what we do. We are rebuilding. That’s the yes that people have to hear about.”

Rebuilding what? I asked.

“To use Pope Benedict’s phrase, which he repeated many times, the Western world today lives as though God does not exist,” he says. “I think that’s true. Fragmentation, fear, disorientation, drifting—those are widely diffused characteristics of our society.”

Yes, I thought, this is exactly right. When we lost our Christian religion in modernity, we lost the thing that bound ourselves together and to our neighbors and anchored us in both the eternal and the temporal orders. We are adrift in liquid modernity, with no direction home.

And this monk was telling me that he and his brothers in the

Father Cassian Folsom, February 2016

monastery saw themselves as working on the restoration of Christian belief and Christian culture. How very Benedictine. I leaned in to hear more.

This monastery, Father Cassian explained, and the life of prayer within it, exist as a sign of contradiction to the modern world. The guardrails have disappeared, and the world risks careering off a cliff, but we are so captured by the lights and motion of modern life that we don’t recognize the danger. The forces of dissolution from popular culture are too great for individuals or families, to resist on their own. We need to embed ourselves in stable communities of faith.

Benedict’s Rule is a detailed set of instructions for how to organize and govern a monastic community, in which monks (and separately, nuns) live together in poverty and chastity. That is common to all monastic living, but Benedict’s Rule adds three distinct vows: obedience, stability (fidelity to the same monastic community until death), and conversion of life, which means dedicating oneself to the lifelong work of deepening repentance. The Rule also includes directions for dividing each day into periods of prayer, work, and reading of Scripture and other sacred texts. The saint taught his followers how to live apart from the world, but also how treat pilgrims and strangers who come to the monastery.

Far from being a way of life for the strong and disciplined, Benedict’s Rule was for the ordinary and weak, to help them grow stronger in faith. When Benedict began forming his monasteries, it was common practice for monastics to adopt a written rule of life, and Benedict’s Rule was a simplified and (though it seems quite rigorous to us) softened version of an earlier rule. Benedict had a noteworthy sense of compassion for human frailty, saying in the prologue to the Rule that he hoped to introduce “nothing harsh and burdensome” but only to be strict enough to strengthen the hearts of the brothers “to run the way of God’s commandments with unspeakable sweetness and love.” He instructed his abbots to govern as strong but compassionate fathers, and not to burden the brothers under his authority with things they are not strong enough to handle.

For example, in his chapter giving the order of manual labor, Benedict says, “Let all things be done with moderation, however, for the sake of the faint-hearted.” This is characteristic of Benedict’s wisdom. He did not want to break his spiritual sons; he wanted to build them up.

Despite the very specific instructions found in the Rule, it’s not a checklist for legalism. “The purpose of the Rule is to free you. That’s a paradox that people don’t grasp readily,” Father Cassian said.

If you have a field covered with water because of poor drainage, he explained, crops either won’t grow there, or they will rot. If you don’t drain it, you will have a swamp and disease. But if you can dig a drainage channel, the field will become healthy and useful. What’s more, once the water becomes contained within the walls of the channel, it will flow with force and can accomplish things.

“A Rule works that way, to channel your spiritual energy, your work, your activity, so that you’re able to accomplish something,” Father Cassian said.

“Monastic life is very plain,” he continued. “People from the outside perhaps have a romantic vision, perhaps what they see on television, of monks sort of floating around the cloister. There is that, and that’s attractive, but basically, monks get up in the morning, they pray, they do their work, they pray some more. They eat, they pray, they do some more work, they pray some more, and then they go to bed. It’s rather plain, just like most people. The genius of Saint Benedict is to find the presence of God in everyday life.”

People who are anxious, confused, and looking for answers are quick to search for solutions in the pages of books or on the Internet, looking for that “killer app” that will make everything right again. The Rule tells us: No, it’s not like that. You can achieve the peace and order you seek only by making a place within your heart and within your daily life for the grace of God to take root. Divine grace is freely given, but God will not force us to receive it. It takes constant effort on our part to get out of God’s way and let His grace heal us and change us. To this end, what we think does not matter as much as what we do—and how faithfully we do it.

A man who wants to get in shape and has read the best bodybuilding books will get nowhere unless he applies that knowledge in eating healthy food and working out daily. That takes sustained willpower. In time, if he’s faithful to the practices necessary to achieve his goal, the man will start to love eating well and exercising so much that he is not pushed toward doing so by willpower but rather drawn to it by love. He will have trained his heart to desire the good.

So too with the spiritual life. Right belief (orthodoxy) is essential, but holding the correct doctrines in your mind does you little good if your heart—the seat of the will—remains unconverted. That requires putting those right beliefs into action through right practice (orthopraxy), which over time achieves the goal Paul set for Timothy when he commanded him to “discipline yourself for the purpose of godliness” (1 Timothy 4:7).

The author of 2 Peter explains well the way the mind, the heart, and the body work in harmony for spiritual growth:

Now for this very reason also, applying all diligence, in your faith supply moral excellence, and in your moral excellence, knowledge, and in your knowledge, self-control, and in your self-control, perseverance, and in your perseverance, godliness, and in your godliness, brotherly kindness, and in your brotherly kindness, love. For if these qualities are yours and are increasing, they render you neither useless nor unfruitful in the true knowledge of our Lord Jesus Christ. (2 Peter 1:5-8)

Thought it quotes Scripture in nearly every one of its short chapters, the Rule is not the Gospel. It is a proven strategy for living the Gospel in an intensely Christian way. It is an instruction manual for how to form one’s life around the service of Jesus Christ, within a strong community. It is not a collection of theological maxims but a manual of practices through which believers can structure their lives around prayer, the Word of God, and the ever-deepening awareness that, as the saint says, “the divine presence is everywhere, and that ‘the eyes of the Lord are looking on the good and evil in every place’ (Proverbs 15:3).”

The Rule is for monastics, obviously, but its teachings are plain enough to be adapted by lay Christians for their own use. It provides a guide to serious and sustained Christian living in a fashion that reorders us interiorly, bringing together what is scattered within our own hearts and orienting it to prayer. If applied effectively, it disciplines the life we share with others, breaking down barriers that keep the love of God from passing among us, and makes us more resilient without hardening our hearts.

We are not trying to repeal seven hundred years of history, as if that were possible. Nor are we trying to save the West. We are only trying to build a Christian way of life that stands as an island of sanctity and stability amid the high tide of liquid modernity. We are not looking to create heaven on earth; we are simply looking for a way to be strong in faith through a time of great testing. The Rule, with its vision of an ordered life centered around Christ and the practices it prescribes to deepen our conversion, can help us achieve that goal.

At its core, the Benedict Option is not really about starting new schools, or changing our political engagement, or any of the other things I write about in the book (though they are important). No, the Benedict Option is about what I write in this passage: establishing a strong, disciplined, authentically Christian way of life that makes God present in all that we do, and draws us closer to Him. If this is not what you seek, the Benedict Option is in vain.

Next week, I travel to the University of Colorado at Boulder to give a Benedict Option talk. I’ll be there on Wednesday April 5 from 6 to 8 pm. The talk is free, but you need to register here. I hope to see you there.

March 30, 2017

Mike Pence’s Scandalous Marriage

You have seen, I take it, that our vice president has outed himself as a cultural criminal of the first order by revealing that, like some conservative Christian men, he doesn’t put himself in situations where he could be tempted to compromise his marital vows, or be plausibly accused of same. He never eats alone with another woman, or goes to events where alcohol is served unless his wife is with him. This is pretty quaintly conservative, admittedly, and not something I would do. But I can’t fault the guy, especially given the life politicians have to live. If I were Mrs. Pence, I would surely be grateful.

To no one’s surprise, this has earned Pence denunciation from the more progressive protuberances of the body politic. Emma Green, in customary form, does a good job examining what this weird episode tells us about Americans and gender. Excerpts:

Some folks—mostly journalists and entertainers on Twitter—have reacted with surprise, anger, and sarcasm to the Pence family rule. Socially liberal or non-religious people may see Pence’s practice as misogynistic or bizarre. For a lot of conservative religious people, though, this set-up probably sounds normal, or even wise. The dust-up shows how radically notions of gender divide American culture.

Were the Pences Orthodox Jews or practicing Muslims, nobody would have batted an eye. But they’re Evangelical Christians, so that means it’s open season on tearing them apart.

Pence told The Hill in 2002 that his practice is about building a zone of protection around his marriage. Green:

The 2002 article notes that Pence arrived in Congress a half decade after the 1994 “Republican revolution,” when Newt Gingrich was the speaker of the House. Several congressional marriages, including Gingrich’s, encountered difficulty that year. Pence seemed wary of this. “I’ve lost more elections than I’ve won,” he said. “I’ve seen friends lose their families. I’d rather lose an election.” He even said he gets fingers wagged in his face by concerned Indianans. “Little old ladies come and say, ‘Honey, whatever you need to do, keep your family together,’” he told TheHill.

These comments show that the Pences have a distinctively conservative approach toward family, sex, and gender. This is by no means the way that all Christians, or even all evangelical Christians like the Pences, navigate married life. But traditional religious people from other backgrounds may practice something similar. Many Orthodox Jews follow the laws of yichud, which prohibit unmarried men and women from being alone in a closed room together. Some Muslim men and women also refuse to be together alone if they’re not married. These practices all have different histories and origins, but they’re rooted in the same belief: The sanctity of marriage should be protected, and sexual immorality should be guarded against at all costs.

Again, this is not a set of precautions I, as a Christian, would take, or feel it necessary to take, but I admire the Pences for the seriousness with which they take their marriage vows. Mike Pence is willing to be thought a countercultural weirdo for the sake of doing right by his wife, his kids, and his God. That’s totally admirable in my book.

One more bit from Green:

That some people are so quick to be angered—and others are totally unsurprised—shows how divided America has become about the fundamental claim embedded in the Pence family rule: that understandings of gender should guide the boundaries around people’s everyday interactions, and protecting a marriage should take precedence over all else, even if the way of doing it seems strange to some, and imposes costs on others.

HuffPo puffed a gay couple who started a store catering to diaper-wearing pervs, but ran a piece criticizing the Pences as weirdos for the patriarchy. Given their standards (if “standards” is the word), I would take criticism from HuffPo as a compliment.

Somebody put on Twitter this deeply affecting World magazine piece showcasing the hard lessons that Mark Souder, a Republican Congressman from Indiana and religious-right stalwart, learned after his longterm adulterous affair with a staffer became public. Souder talks in the piece about his own terrible failure, and how his life as a Washington politician set him up to fall. Here’s an excerpt from that 2010 piece relevant to our discussion today:

Mike Pence, R-Ind., took the Quayles’ advice and moved his family (with three children then under the age of 8) after winning election in 2000. Later, when Mike and Karen Pence’s fourth-grade son broke his collarbone on the playground at school, the congressman was able to come to the emergency room straight from Capitol Hill. Karen was composed until he walked into the room, then melted. “I realized, I’m really glad he’s here and I don’t have to do this all by myself,” she recalled.

Karen Pence talked with me about how she sits down with her husband’s scheduler to scrutinize school calendars so they can map out days that Mike needs to be available to his family: “Not only do my kids need Mike, Mike needs the kids.” She doesn’t prescribe a Washington move for everyone: “We were blessed that our kids were at an age where they could move easily. . . . Every family has to make its own choice.”

Some legislators fill their Capitol Hill offices with family pictures, not only to impress constituents but to remind themselves. When Mike Pence took office in 2001, Karen installed a red landline phone in his Capitol Hill office-and only she knew the number. It’s a bit of a gimmick now, since she can connect with him on his BlackBerry much more easily, but the phone sticks out as a reminder.

Plainly these are horrible neo-Amish trolls who deserve pop culture’s disdain. Meanwhile, anybody heard lately from Carlos Danger? Wonder what Huma Abedin thinks about the Pence arrangement…

UPDATE: Great comment by Mark:

Evangelicals are hypocrites for voting for Trump given the disrespect he has for marriage, and his willingness to defile the marriage bed. Because that’s Bad For Women.

Evangelicals are crazy religious fanatics for having rules like Pence’s for safeguarding marriage, and avoiding even situations that might begin a pattern that could flower into defiling the marriage bed. Because that’s Bad For Women.

Luke chapter 7:

31 “To what then shall I compare the men of this generation, and what are they like? 32 They are like children who sit in the market place and call to one another, and they say, ‘We played the flute for you, and you did not dance; we sang a dirge, and you did not weep.’ 33 For John the Baptist has come eating no bread and drinking no wine, and you say, ‘He has a demon!’ 34 The Son of Man has come eating and drinking, and you say, ‘Behold, a gluttonous man and a drunkard, a friend of tax collectors and sinners!’ 35 Yet wisdom is vindicated by all her children.”

When the heart is corrupted, everything looks foolish and corrupt.

‘Destroy That Art!’ Cried The Woke Artists

In the current Whitney Biennial, a very big-deal art show in New York, there is a 2016 painting depicting the body of Emmett Till, the Mississippi teenager murdered by white supremacists in 1955. Artist Dana Schutz, who is white, created the highly abstract image from famous open-casket photographs of Till at his funeral. Till’s mother wanted the world to see what white supremacists had done to her son. Those photographs served as a catalyst for civil rights protest, and are now an icon of American history.

Schutz’s painting has been denounced by some black artists and others, because the painter is white. Hannah Black, a British-born black artist, has written an open letter demanding that the Whitney Museum not only take the painting down, but also destroy it. Here is the full text of her letter, which is drawing a number of signers:

OPEN LETTER

To the curators and staff of the Whitney biennial:

I am writing to ask you to remove Dana Schutz’s painting “Open Casket” and with the urgent recommendation that the painting be destroyed and not entered into any market or museum.

As you know, this painting depicts the dead body of 14-year-old Emmett Till in the open casket that his mother chose, saying, “Let the people see what I’ve seen.” That even the disfigured corpse of a child was not sufficient to move the white gaze from its habitual cold calculation is evident daily and in a myriad of ways, not least the fact that this painting exists at all. In brief: the painting should not be acceptable to anyone who cares or pretends to care about Black people because it is not acceptable for a white person to transmute Black suffering into profit and fun, though the practice has been normalized for a long time.

Although Schutz’s intention may be to present white shame, this shame is not correctly represented as a painting of a dead Black boy by a white artist — those non-Black artists who sincerely wish to highlight the shameful nature of white violence should first of all stop treating Black pain as raw material. The subject matter is not Schutz’s; white free speech and white creative freedom have been founded on the constraint of others, and are not natural rights. The painting must go.

Emmett Till’s name has circulated widely since his death. It has come to stand not only for Till himself but also for the mournability (to each other, if not to everyone) of people marked as disposable, for the weight so often given to a white woman’s word above a Black child’s comfort or survival, and for the injustice of anti-Black legal systems. Through his mother’s courage, Till was made available to Black people as an inspiration and warning. Non-Black people must accept that they will never embody and cannot understand this gesture: the evidence of their collective lack of understanding is that Black people go on dying at the hands of white supremacists, that Black communities go on living in desperate poverty not far from the museum where this valuable painting hangs, that Black children are still denied childhood. Even if Schutz has not been gifted with any real sensitivity to history, if Black people are telling her that the painting has caused unnecessary hurt, she and you must accept the truth of this. The painting must go.

Ongoing debates on the appropriation of Black culture by non-Black artists have highlighted the relation of these appropriations to the systematic oppression of Black communities in the US and worldwide, and, in a wider historical view, to the capitalist appropriation of the lives and bodies of Black people with which our present era began. Meanwhile, a similarly high-stakes conversation has been going on about the willingness of a largely non-Black media to share images and footage of Black people in torment and distress or even at the moment of death, evoking deeply shameful white American traditions such as the public lynching. Although derided by many white and white-affiliated critics as trivial and naive, discussions of appropriation and representation go to the heart of the question of how we might seek to live in a reparative mode, with humility, clarity, humour and hope, given the barbaric realities of racial and gendered violence on which our lives are founded. I see no more important foundational consideration for art than this question, which otherwise dissolves into empty formalism or irony, into a pastime or a therapy.

The curators of the Whitney biennial surely agree, because they have staged a show in which Black life and anti-Black violence feature as themes, and been approvingly reviewed in major publications for doing so. Although it is possible that this inclusion means no more than that blackness is hot right now, driven into non-Black consciousness by prominent Black uprisings and struggles across the US and elsewhere, I choose to assume as much capacity for insight and sincerity in the biennial curators as I do in myself. Which is to say — we all make terrible mistakes sometimes, but through effort the more important thing could be how we move to make amends for them and what we learn in the process. The painting must go.

Thank you for reading

Hannah Black

Artist/writer

Whitney ISP 2013-14

See the reprint in ArtNews for the names of the co-signers.

So there you have it: prominent artists demanding that a museum not only remove a work of art, but destroy it, because the artist is white, and her subject is black. Think about that. Think about where this is going.

Queering Engineering At Purdue

Having all but ruined humanities education, the Social Justice Warriors now turn to the STEM fields. Purdue University has hired Donna Riley as its new head of its School of Engineering Education. Here’s an excerpt from Prof. Riley’s biography page at Smith College, where she taught for 13 years:

My scholarship currently focuses on applying liberative pedagogies in engineering education, leveraging best practices from women’s studies and ethnic studies to engage students in creating a democratic classroom that encourages all voices. In 2005 I received a CAREER award from the National Science Foundation to support this work, which includes developing, implementing, and assessing curricular and pedagogical innovations based on liberative pedagogies and student input at Smith, and understanding how students at Smith conceptualize their identities as engineers. I seek as an engineering educator to be part of a paradigm shift that these pedagogies demand, repositioning concerns about diversity in science and engineering from superficial measures of equity as headcounts, to addressing justice and the genuine engagement of all students as core educational challenges.

I currently teach traditional courses in the areas of chemical and environmental engineering, as well as elective courses on engineering and global development, science, technology, and ethics (cross-listed with SWG) and technological risk assessment and communication. I seek to revise engineering curricula to be relevant to a fuller range of student experiences and career destinations, integrating concerns related to public policy, professional ethics and social responsibility; de-centering Western civilization; and uncovering contributions of women and other underrepresented groups.

In EGR 330 (Engineering and Global Development), we critically evaluate past and current trends in appropriate and sustainable technology. We examine how technology influences and is influenced by globalization, capitalism and colonialism, and the role technology plays in movements that counter these forces. Gender is a key thread running through the course in examining issues of water supply and quality, food production and energy.

In EGR 205 (Science, Technology and Ethics), we consider questions such as who decides how science and engineering are done, who can participate in the scientific enterprise and what problems are legitimately addressed within these disciplines and professions. We take up racist and colonialist projects in science, as well as the role of technology, culture and economic systems in the drive toward bigger, faster, cheaper and more automated production of goods. A course theme around technology and control provides for exploration of military, information, reproductive and environmental applications. Using readings from philosophy, science and technology studies, and feminist and postcolonial science studies, we explore these topics and encounter new models of science and engineering that are responsive to ethical concerns.

She will come to Purdue from Virginia Tech. This is an excerpt from her faculty page there:

Riley’s research interests include engineering and social justice; engineering ethics; social inequality in engineering education; and the liberal education of engineers. In 2005 she received a National Science Foundation CAREER award on implementing and assessing critical and feminist pedagogies in engineering classrooms. Students in Riley’s research group are pursuing interests including culturally inclusive pedagogies; understanding faculty motivations and approaches to teaching engineering ethics; connections between critical thinking and engineering ethics pedagogies; engineering education policy; and public participation in engineering projects impacting communities.

And there you were, thinking that the hard sciences and engineering were immune to this kind of thing, because they are about numbers.

Anybody object to bringing cultural politics into the engineering classroom? Anybody think there’s something … off about using engineering courses to “de-center” Western civilization? Go ahead, I dare you to object. You and your white male science privilege!

Here’s the kind of thing Purdue engineering students can expect henceforth. It’s from the blog of one of Dr. Riley’s students at Smith, who writes approvingly:

Critical pedagogy is the education movement aimed developing students into socially and politically aware individuals, helping them recognize authoritarian tendencies, empowering them to act against injustice, and employing democratic and inclusive classroom practices. The term “critical pedagogy” has been used by educators to refer to a broad range of pedagogies that employ critical theory, feminist theory, queer theory, anti-racist theory, multicultural education, and inclusive pedagogies. In this post, I will discuss some of the critical pedagogy practices employed by Dr. Donna Riley (currently a professor at Virginia Tech) while teaching a class called “Engineering Thermodynamics” as Smit College, an all women college, during Spring and Fall semesters of 2002. It should be noted that Riley uses liberative pedagogy as an inclusive term for critical pedagogy, feminist pedagogy, and radical pedagogy. Some of the classroom practices employed by Riley included:

Connecting learning to students’ experiences. Students learn the most from examples which they can relate to, based on their social and cultural backgrounds. Hence, Riley used a wide variety of thermodynamic systems in class as examples. Also, the textbook for the class was chosen such that it contained a wide variety of examples of thermodynamic systems.

Democratic classroom practices. Students were assigned teaching roles to teach parts of the course to the entire class. They were not only asked to develop modules to teach the class but also encouraged to relate them to their own lives. Also, the seating arrangement reflected the democratic classroom practices. Instead of sitting in rows facing the instructor, students were asked to sit in circles with each student facing and talking to the entire class instead of just the instructor.

Taking responsibility for one’s own learning. Students were required to take responsibility for their learning in that they were asked to do metacognitive reflections on what was working or not working for them in the class. They were also asked to do assignments in which they reflected on their learning of various aspects of the course.

Ethics discussions. In order for students to be develop as ethically responsible individuals, they need to learn the impact which an engineer’s work has on the society. To develop such an ethical awareness, Riley and her class watched and critiqued videos on “energy in society”, critiqued the textbook used for the class by analyzing the aspects (e.g. alternate energy, environmental applications of thermodynamics, energy system in developing countries) which were missing from the textbook. Also, students were assigned ethics problems to reflect on.

Breaking the Western hegemony. In order to decenter the male hegemony of the Western civilization, Riley discussed examples of thermodynamic inventions done by non-Western and non-male inventors. Also, some of the assignments required students to make interracial and intercultural connections in thermodynamics.

Normalizing mistakes. By normalizing mistakes in the process of learning, Riley fostered a classroom environment in which students were comfortable attempting problems (sometimes even on the black board) in class and learning from their mistakes. Another strategy used by her for normalizing mistakes was acknowledging when she herself did not know something.

Discussion of history and philosophy. Riley discussed the history and philosophy of the development of thermodynamic laws to demonstrate to the students that the process of discovery does not lead one to an absolute truth. Instead, making mistakes is acceptable in the process of discovery. Students were also required to reflect on how the knowledge of history and philosophy of thermodynamics helped their learning.

Assessment techniques. The assessment of students put a greater emphasis on participation. Moreover, a flexible grading system was adopted. Students were asked to work in pairs on some exams. In the second offering of the course, problems were given to the students only as a learning exercise and not as an assessment tool. Moreover, continual course feedback was taken from students to improve their learning experience.

One of the critiques of critical pedagogy is that it does not provide specific classroom practices. It just suggests that teaching and learning should be contextual and aim at raising critical awareness among students. A lot of times educators do not know how to apply critical pedagogy in their classes, especially in hard and applied sciences, due to a lack of knowledge about how to apply it. I hope the practices noted above can be adopted to and adapted for any classroom and any discipline.

Here’s an interview with Dr. Riley as part of a “Queered Science” series. Riley is a lesbian, and uses gender-neutral pronouns. Excerpt:

While overt sexism and homophobia are less common than historically, they still play out in ways that are subtle and, therefore, insidious and hard to combat. How do you see this happening in the sciences, and how do you deal with it?

One of the biggest sources of sexism and homophobia is lodged in the epistemology of science. How we think, and what we think, matter in determining what we know and don’t know, and affects our workplace interactions in very negative ways. We think that we eliminate bias by keeping our “personal lives” – some aspects of ourselves – out of the lab, classroom, or office. But actually this is how we allow implicit bias to seep in and saturate everything we do, because that which is male, straight, white, able-bodied, monied, is not left behind in the practice of science and engineering – it is just so normative that lots of us don’t notice.

I have learned that talking about these issues and building solidarity with like-minded others is the only way we can ever address them. Ultimately scientists and engineers have to be able to think outside the epistemological boxes we’ve been trained into to understand diversity and social justice. Cultural change takes a lot of hard work, it takes talking to people and organizing — skills typically not in our wheelhouses as scientists and engineers.

Congratulations, Purdue. This is going to be interesting. I wonder where the undergraduates who just want to get an engineering education without being harangued by a critical-studies commissar will go to school now?

Sports: Red America’s Achilles Heel

The North Carolina legislature appears set to repeal the state’s controversial bathroom bill today. Here’s a big reason why:

This week, a new flurry of action over House Bill 2 came as the N.C.A.A. warned the state that it could lose the opportunity to host championship sporting events through 2022. The league had already relocated championship tournament games that would have been played in North Carolina during this academic year, including the Division I men’s basketball tournament.

The possibility of further punishment placed tremendous pressure on lawmakers in the basketball-obsessed state, a pressure exacerbated by the fact that the University of North Carolina men’s basketball team has reached the N.C.A.A. tournament’s Final Four and will be squaring off against the University of Oregon on Saturday night.

The Atlantic Coast Conference also moved its neutral-site championships out of North Carolina this year in response to House Bill 2, and the National Basketball Association moved its All-Star game to New Orleans from Charlotte.

Some local news outlets reported this week the N.C.A.A. had set a Thursday deadline for the state to address the bill. Officials at the association could not be reached for comment Wednesday. A league statement last week stated, “Absent any change in the law, our position remains the same regarding hosting current or future events in the state.”

Attention must be paid. You should expect that this strategy is how the NCAA is going to dictate to colleges and university what their LGBT policies are going to be. Want to be part of national college athletics? Then you had better do what the NCAA says. If it comes right down to it, do you think Baylor (for example) would sacrifice its athletic programs or its Christian principles on LGBT matters? If the university leadership decided that it would rather see athletics taken away from them than compromise on its principles, can you imagine how hard alumni would come down on them?

Of course there is no question at all where my alma mater, Louisiana State, would stand if it had to choose. The NCAA could demand at the start of every football season the ritual sacrifice of five Pentecostal virgins on the Tiger Stadium 50-yard-line, and the people of Louisiana wouldn’t bat an eye. Just keep that football coming. Because it’s the true religion.

But LSU is a state school. Conservative Christian colleges and their alumni had better start thinking right now about whether or not they are willing to sacrifice their athletic programs for principle. That decision is coming, and coming fast.

March 29, 2017

Lifestyles Of The ‘Jew-Curious’

You really can’t make this up. It’s a feature about people who are making a non-religious lifestyle brand of Judaism, and marketing it to unbelieving bourgeois Jews and fellow travelers among the goyim. Excerpts:

“Jewish culture is in the mainstream, it’s popular, and that’s something any brand would want to jump on,” says Danya Shults, 31, founder of Arq, a lifestyle company that seeks to sell people of all faiths on a trendy, tech-literate, and, above all, accessible version of Jewish traditions. Arq is a portal for interfaith couples, their friends, and their families to find “relevant, inclusive, aesthetically elevated” information and products. It offers holiday-planning guides; Seder plates designed by Isabel Halley, the ceramicist who outfitted the female-only social club the Wing; and interviews with Jewish entrepreneurs, as well as chefs who cook up artisanal halvah and horseradish. There’s also an event series, including a weekend retreat in the Catskills in upstate New York that Shults says is “inspired by Jewish summer camp but more Kinfolk-y,” referring to the elegantly twee lifestyle magazine.

Shults grew up in an observant home, attended a Jewish day school, and became fluent in Hebrew. Then she got engaged to a Presbyterian. “We never really found a [religious] community that matched what we were looking for, especially for me,” says Shults’s now-husband, Andrew. Many of the synagogues that purported to be inclusive turned out to have an agenda, such as trying to get Andrew to convert or cultivating the couple’s political support for Israel.

The troubles didn’t end there. Shults tells the story of one non-Jewish friend who went shopping for the couple by Googling “chic Jewish wedding gift” and found the results to be either “totally out of style or far too didactic and preachy.” Cool, inclusive presents did exist—Shults knew that much—but they weren’t easy to find. Thus, Arq was born. “My ultimate test case was my husband,” Shults says. “Would he discover this? Read this? Go to this event?”

Arq may be the most ambitious new company hoping to court the Jew-curious community, but it’s not the only one.

Oh no it isn’t. You have to read this story to believe it. These people are outrageously self-parodic. Look:

Arq has linked up with the wedding registry company Zola Inc. to curate Jewish presents that don’t look as if they come from the synagogue gift shop; with the home design site Apartment Therapy, on a series of Judaica-focused home tours; and with the feminist/LGBTQ-friendly wedding-planning site Catalyst Wedding Co., on an interview series with couples who are diverse in every imaginable way. Arq-branded events have included a couples’ salon series in partnership with Honeymoon Israel, a nonprofit that sends “nontraditional” (interfaith, same-sex) couples on trips to Israel, and a women’s lunar retreat, based on the ancient Jewish practice of women celebrating one another around the new moon.

And:

Not every Jew-ish company has such a social mission, however. The Matzo Project has taken as its task getting unleavened bread out of the ethnic food aisle. “We want it to be more than something that very pious Jews eat at Passover,” says co-founder Ashley Albert. The company’s offerings include matzo flats and chips in salted, everything, and cinnamon-sugar flavors, as well as a matzo butter crunch bar.

Of course. Again, read the whole thing. Here’s a link to the announcement about the debut of Arq, which bills itself as “about making Jewish life and culture accessible to everyone through engaging and honest content, inviting experiences, and aesthetically elevated products.”

Aesthetically elevated products. Wow. Just, wow. Here’s Arq’s own website. For the people who like this kind of thing, this is the kind of thing they like. If you ask me, Moses needs to come down from Sinai and get folks sorted.

By way of contrast, I commend to you this profound, beautiful essay by the late Orthodox Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, on the meaning of community in Judaism. Compare and contrast. It’s not lifestyle-branding. In fact, this is the kind of Jewish wisdom from which all of us Gentiles can benefit, even though, sadly, it lacks aesthetically elevated products.

St. Benedict, Colossus Of Western History

The great Whittaker Chambers, writing in Commonweal in 1952, about discovering the legacy of St. Benedict of Nursia. Here he is talking about how, as a student, the Middle Ages (aka, the Dark Ages) were presented to him:

The Dark Ages were inexcusable and rather disreputable—a bad time when the machine of civilization in its matchless climb to the twentieth century had sheared a whole rank of king-pins and landed mankind in a centuries-long ditch. At best, it was a time when monks sat in unsanitary cells with a human skull before them, and copied and recopied, for lack of more fruitful employment, the tattered records of a dead antiquity. That was the Dark Ages at best, which, as anybody could see, was not far from the worst.

If a bright boy, leafing through history, asked: “How did the Dark Ages come about?” he might be told that “Rome fell!”–as if a curtain simply dropped. Boys of ten or twelve, even if bright, are seldom bright enough to say to themselves: “Surely, Rome did not fall in a day.” If a boy had asked: “But were there no great figures in the Dark Ages, like Teddy Roosevelt, King Edward, and the Kaiser?” he might well have been suspected of something like an unhealthy interest in the habits and habitats of spiders. If he had persisted and asked: “But isn’t it clear that the Dark Ages are of a piece with our age of light, that our civilization is by origin Catholic, that, in fact, we cannot understand what we have become without understanding what we came from?” he would have been suspected of something much worse than priggery—a distressing turn to popery.

I was no such bright boy (or youth). I reached young manhood serene in the knowledge that, between the failed light of antiquity and the buzzing incandescence of our own time, there had intervened a thousand years of darkness from which the spirit of man had begun to liberate itself (intellectually) first in the riotous luminosity of the Renaissance, in Humanism, in the eighteenth century, and at last (politically) in the French Revolution. For the dividing line between the Dark Ages is not fast, and they were easily lumped together.

Much later in his life, at age 50, having been through and come out of Communism, and consumed by anxiety over the fate of Western civilization in the Cold War, Chambers received a St. Benedict medal from a friend. He didn’t know who Benedict was, and started researching him. He learned:

For the briefest prying must reveal that, simply in terms of history, leaving aside for a moment his sanctity, St. Benedict was a colossal figure on a scale of importance in shaping the civilization of the West against which few subsequent figures could measure. And of those who might measure in terms of historic force, almost none could measure in terms of good achieved.

Nor was St. Benedict an isolated peak. He was only one among ranges of human height that reached away from him in time in both directions, past and future, but of which, with one or two obvious exceptions, one was as ignorant as of Benedict: St. Jerome, St. Ambrose, St. Augustine, Pope St. Leo the Great, Pope St. Gregory the Great, St. Francis of Assisi, Hildebrand (Pope Gregory VII).

Clearly, a cleft cut across the body of Christendom itself, and raised an overwhelming question: What, in fact, was the civilization of the West? If it was Christendom, why had it turned its back on half its roots and meanings and become cheerfully ignorant of those who had embodied them? If it was not Christendom, what was it? And what were those values that it claimed to assert against the forces of active evil that beset it in the greatest crisis of history since the fall of Rome? Did the failure of the Western World to know what it was lie at the root of its spiritual despondency, its intellectual confusion, its moral chaos, the dissolving bonds of faith and loyalty within itself, its swift political decline in barely four decades from hegemony of the world to a demoralized rump of Europe little larger than it had been in the crash of the Roman West, and an America still disputing the nature of the crisis, its gravity, whether it existed at all, or what to do about it?

Answers to such questions could not be extemporized. At the moment, a baffled seeker could do little more than grope for St. Benedict’s hand and pray in all humbleness to be led over the traces of the saint’s progress to the end that he might be, if not more knowledgeable, at least less nakedly ignorant.

Chambers writes beautifully, and in detail, about what Benedict and his Rule accomplished. He concludes:

It has been said (by T. F. Lindsay in his sensitive and searching St. Benedict) that, in a shattered society, the Holy Rule, to those who submitted to its mild but strict sway, restored the discipline and power of Roman family life.

I venture that it did something else as well. For those who obeyed it, it ended three great alienations of the spirit whose action, I suspect, touched on that missing something which my instructors failed to find among the causes of the fall of Rome. The same alienations, I further suspect, can be seen at their work of dissolution among ourselves, and are perhaps among the little noticed reasons why men turn to Communism. They are: the alienation of the spirit of man from traditional authority; his alienation from the idea of traditional order; and a crippling alienation that he feels at the point where civilization has deprived him of the joy of simple productive labor.

These alienations St. Benedict fused into a new surge of the human spirit by directing the frustrations that informed them into the disciplined service of God. At the touch of his mild inspiration, the bones of a new order stirred and clothed themselves with life, drawing to itself much of what was best and most vigorous among the ruins of man and his work in the Dark Ages, and conserving and shaping its energy for that unparalleled outburst of mind and spirit in the Middle Ages. For about the Benedictine monasteries what we, having casually lost the Christian East, now casually call the West, once before regrouped and saved itself.

So bald a summary can do little more than indicate the dimensions of the Benedictine achievement and plead for its constant re-examination. Seldom has the need been greater. For we sense, in the year 1952, that we may stand closer to the year 410 than at any other time in the centuries since. If that statement seems as extreme as any of Salvian’s, three hundred million Russians, Poles, Czechs, Slovaks, East Germans, Austrians, Hungarians, and all the Christian Balkans, would tell you that it is not—would tell you if they could lift their voices through the night of the new Dark Ages that have fallen on them. For them the year 410 has already come.

In our own time, Jackson Wu writes about how the contemporary suffering church in China is a test case for the Benedict Option:

China is “pre-Christian” in that Christianity has never been the pervasive perspective shaping Chinese culture; yet, the church in China functionally finds itself in a similar state that Dreher foresees for the American church. Here is an initial list of similarities:

Chinese Christians lack formal political power.

Constitutionally, people have religious liberty, so long as they agree with the State.

Chinese believers socially are a minority.

Chinese Christians tend to be “localists.” That is, they focus on their local congregation, they closely rely on a local network with whom they identify for practical help.

More Christian Christians see the importance of educating their kids apart from the official atheist system, which actively disparages and undermines Christian teaching. However, Christian schooling is illegal. Attempting to educate one’s child outside the official system has significant risks.

Morally, Chinese culture is relativistic. It does not affirm absolute right and wrong. Individuals make moral decisions based on personal whim, relationships, and laws.

Materialism runs ramped in China.

Christians tend to avoid overtly political activity.

Chinese believers regularly face “soft persecution” for their faith (economic, legal and social sanctions, as opposed to death and prison).

To be a faithful Christian, one has limited employment options.The following are more “fuzzy” and subjective, but are often true.

Temperamentally, evangelical congregations are generally concerned with purity (whether of doctrine or practice), though they––like churches everywhere–– fall short of their ideals.

Traditionally, Chinese understand the primary purpose of education ought to be the development of character, not only skills and knowledge to find a job.

Believers see themselves as a part of a long tradition that needs to be preserved.

More Wu:

The key issue is priority. Chinese Christians prioritize the local congregation rather than attempt to engineer political change. Since Jesus is king, they need not cause undue distress trying to make him president.

What someone might call “withdrawal” simply means this: we should have wisdom in choosing which social spheres will get our attention including how much social capital we will use among outsiders versus insiders.

That’s really well said. Please read Wu’s entire post, and see what he says is a potential problem with the implementation of the Ben Op in the West, and what we can learn from Chinese Christians that would help us meet the challenge. Can any of you readers recommend a good book or two on the contemporary experience of the Chinese church? I would be grateful for that information.

And please read The Benedict Option, and add your thoughts and your voice to the vital conversation of how we in the church are to live in these darkening post-Christian times. I don’t have all the answers, and you probably don’t either. We are going to have to work this out together. But I tell you this: if you don’t see a grave crisis of the Christian faith within Western civilization, then you are either not looking, or are not willing to see what is right in front of your nose.

A: Because It’s Full Of Mormons

Once I got there, I found that it’s hard to even get a complete picture of how Utah combats poverty, because so much of the work is done by the Mormon Church, which does not compile neat stacks of government figures for the perusal of eager reporters.

The church did, however, give me a tour of its flagship social service operation, known as Welfare Square. It’s vast and inspiring and utterly foreign to anyone familiar with social services elsewhere in the country. This starts to offer some clue as to why Utah seems to be so good at generating mobility — and why that might be hard to replicate without the Latter-Day Saints.

More:

“Big government” does not appear to have been key to Utah’s income mobility. From 1977 to 2005, when the kids in Chetty et al’s data were growing up, the Rockefeller Institute ranks it near the bottom in state “fiscal capacity.” The state has not invested a lot in fighting poverty, nor on schools; Utah is dead last in per-pupil education spending. This should at least give pause to those who view educational programs as the natural path to economic mobility.

But “laissez faire” isn’t the answer either. Utah is a deep red state, but its conservatism is notably compassionate, thanks in part to the Mormon Church. Its politicians, like Senator Mike Lee, led the way in rejecting Donald Trump’s bid for the presidency. And the state is currently engaged in a major initiative on intergenerational poverty. The bill that kicked it off passed the state’s Republican legislature unanimously, and the lieutenant governor has been its public face.

Megan found that Utah’s government is startlingly functional. A capable bureaucracy is good — but the real secret seems to be the Mormon Church. Excerpt:

Many charity operations offer a food pantry or a thrift shop. Few of them can boast, in addition, their own bakery, dairy operation and canning facilities, all staffed by volunteers. The food pantry itself looks like a well-run grocery store, except that it runs not on money, but on “Bishop’s Orders” spelling out an individualized list of food items authorized by the bishop handling each case. This grows out of two features of Mormon life: the practice of storing large amounts of food against emergencies (as well as giving food away, the church sells it to people for their home storage caches), and an unrivaled system of highly organized community volunteer work.

The volunteering starts in the church wards, where bishops keep a close eye on what’s going on in the congregation, and tap members as needed to help each other. If you’re out of work, they may reach out to small business people to find out who’s hiring. If your marriage is in trouble, they’ll find a couple who went through a hard time themselves to offer advice.

Thing is, the Mormon vision is not welfare-as-a-way-of-life; it’s about a temporary hand-up on a family’s way back to self-sustainability. McArdle goes on to talk about how Mormon social values — for example, a strong culture of marriage — work to lower poverty. She also mentions that Utah’s statistics may be so favorable because blacks are only 1 percent of the population there (Hispanics are 13 percent). Not too many black Mormons in the world. But it shouldn’t be overlooked that the white people who populate Utah are a lot more functional than whites elsewhere. The difference is the LDS faith. Even if you aren’t Mormon, Mormonism sets the tone for public life. One more excerpt:

No place is perfect. But with mobility seemingly stalled elsewhere, and our politics quickly becoming as bitter as a double Campari with no ice, I really, really wanted to find pieces of Utah’s model that could somehow be exported.

Price gave me some hope. The Mormon Church, he says, has created “scripts” for life, and you don’t need religious faith for those; you just need cultural agreement that they’re important. He said: “Imagine the American Medical Association said that if the mother is married when she’s pregnant, the child is likely to do better.” We have lots of secular authorities who could be encouraging marriage, and volunteering, and higher levels of community involvement of all kinds. Looking at the remarkable speed with which norms about gay marriage changed, thanks in part to an aggressive push on the topic from Hollywood icons, I have to believe that our norms about everyone else’s marriages could change too, if those same elites were courageous enough to recognize the evidence, and take a stand.

And as I saw myself, Mormonism also seems to have a script for a different kind of politics, one that might, just possibly, help us do some of the other things. Enough to make a difference.

Read the whole thing. It’s really good. In The Benedict Option, I talked to Terryl Givens, an LDS academic, about why Mormons are so good at building strong ties to each other within the church. Here is part of what he told me (from the book):

In his first letter to the church in Corinth, Paul urged the believers there to “have the same care for one another. “If one member suffers, all suffer together,” the apostle wrote. “If one member is honored, all rejoice together. Now you are the Body of Christ, and individually members of it.”

The LDS Church lives out that principle in a unique way. The Mormon practice of “home teaching” directs two designated Mormon holders of the church’s priestly office to visit every individual or family in a ward at least once a month, to hear their concerns and offer counsel. A parallel program called Relief Society involves women ministering to women as “visiting teachers.” These have become a major source of establishing and strengthening local community bonds.

“In theory, if not always in practice, every adult man and woman is responsible for spiritually and emotionally sustaining three, four, or more other families, or women, in the visiting teaching program,” says the LDS’s Terryl Givens. He adds that Mormons frequently have social gatherings to celebrate and renew ties to community. “Mormonism takes the symbolism of the former and the randomness of the latter and transforms them into a deliberate ordering of relations that builds a warp and woof of sociality throughout the ward,” he says.

Non-Mormons can learn from the deliberate dedication that wards—at both leadership and lay levels—have to caring for each other spiritually. The church community is not merely the people one worships with on Sunday but the people one lives with, serves, and nurtures as if they were family members. What’s more, the church is the center of a Mormon’s social life.

“The consequence is that wherever Mormons travel, they find immediate kinship and remarkable intimacy with other practicing Mormons,” Givens says. “That is why Mormons seldom feel alone, even in a hostile— increasingly hostile—world.”

Ideas have consequences. Among the American religious groups whose youth tested lowest for Moralistic Therapeutic Deism, the Mormons stood out. Nobody else was even close. Those folks are doing something right. Those folks are doing a lot of things right. The rest of us may reject their theology, but we can learn a lot from them on how to incorporate that faith into family and communal life.

Rod Dreher's Blog

- Rod Dreher's profile

- 503 followers