Rod Dreher's Blog, page 181

January 12, 2020

Trump’s Iran Luck

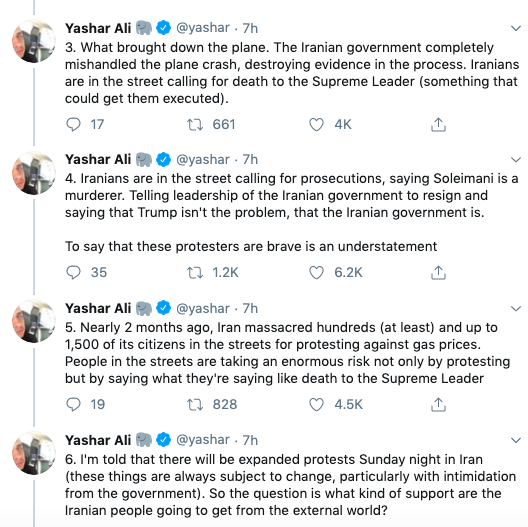

You know that I thought Trump was reckless to have assassinated Soleimani. I strongly reject, though, that Trump bears any moral fault in the disgusting Iranian regime’s incompetent downing of a Ukrainian passenger plane. Seems like more than a few American liberals want to blame that completely avoidable act on Trump, hating him more than they despise a vicious theocracy that stupidly murdered 173 innocents, lied about it, and tried to cover up the evidence, until that was no longer possible. Bizarrely, Trump came out of this looking good (though GOP Sen. Lee and the Senate Democrats are absolutely right to push for a War Powers resolution; let’s not lose sight of that).

Well, look at this. Something wild is going on in Iran today.

Incredible. What if Trump’s whacking Soleimani turns out to have been the domino that brought down the ayatollahs’ tyranny? Let us hope so. It would be terrific if Iran could become a normal country again.

Anti-Trump Americans have to decide if they hate Trump more than they want Iranians to be free of the dictatorship. If the regime collapses, history will owe an extraordinary debt to President Trump. As someone who criticized his Soleimani aggression, I feel the need to concede that.

The post Trump’s Iran Luck appeared first on The American Conservative.

January 10, 2020

The Insanity Of Transgenderism

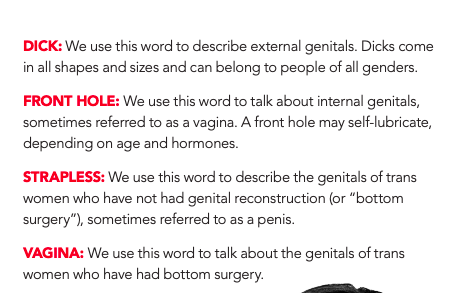

Here, in an advice to “safer” transgender sex, is a list of definitions put out by the Human Rights Campaign Foundation, the biggest and most powerful LGBT lobby in the country. (A PDF of the whole document is here, and it’s definitely NSFW, unless you work in a gay bar or on a humanities faculty.):

So, “human rights” now entails referring to a woman’s genitalia as a “front hole.” The “vagina” is the result of having your penis amputated.

These insane people are driving culture and even law. This stuff is only tangentially related to gay rights. It is possible to be for full rights for gay people, without having to endorse this kind of psychotic stuff. But we are not being given that choice. Every one of the Democratic House members, and all the Democratic presidential candidates, support the Equality Act, which would require everyone to accept these claims as civil rights. The HRC normalizes and amplifies this madness, and gives it serious cultural force.

Amy Welborn has a strong piece about “the reality of sex and the lie of gender identity.” Excerpts:

This is a bizarre, deeply damaging moment we’re living in, driven by a tiny minority of people suffering various forms of mental illness. And yes, there are various forms. Once you start looking into this world, you come to understand that there is really no such thing as the monolithic, gentle group of “trans folks” we’re gently reminded to welcome by gentle Father Martin, all gently seeking understanding for their differences.

There are different iterations and roots of this type of dysphoria, like any mental illness, not all understood. There are men who experience this desire, frankly, as a fetish. It’s called autogynephilia, and it’s a thing—a male being aroused by the idea of himself as a woman. There are young people who have been abused, who are on the spectrum, who are deeply influenced by what they see online; there are preteen and teen girls who are confused, disturbed, and revolted by the physical changes they’re experiencing and put off by the crass sexual expectations of youth culture. There are teen-aged girls and boys, young adults, who look at this weird world of strict gender conformity, the land of pink or the land of blue, and think…I don’t fit here. I’m different. Maybe I fit…there.

There’s a lot to say and lot to do and much to resist, but here’s the bottom line at the present moment: Resist and reject “gender self-identity” in all spheres of life, including the law.

That is to say: you are not a woman because you believe you are; you’re not a man because you’ve decided you are. You’re a woman because you are an adult human female. You’re a man because you are an adult human male. You may be wearing a dress and a wig, but you are still a man. Adult human male.

For this—the notion that one can simply decide one’s gender and then merit treatment and rights on that score—is the root of most current trans activism, including political activism, embodied in this country in the so-called Equality Act, endorsed by all the current Democratic candidates for president and passed by the House last spring. Most people don’t understand this. They think that “trans rights” is all about not being mean to people who have gone through counseling and years of medical treatment and surgery—right? Nope. Not at all.

At the core of the Equality Act, and similar efforts in England, is the notion that a person should be treated according to the gender he or she (?) claims, even if they are still physically intact, have never had surgery, and maybe never even intend to. It doesn’t matter if they “pass” or not, or what they look like to you.

More:

If you have the opportunity to interact with a politician who claims support for the Equality Act, ask them questions about it and don’t let go. Don’t accept platitudes. Ask, over and over—Should any biological male who says he is female be granted access to women’s spaces, such as locker rooms? Well, we need to be an inclusive society, welcoming of all people. Great. Should any biological male who says he is female be granted access to women’s spaces, such as locker rooms and restrooms? Trans folks experience a lot of discrimination, you know. That’s too bad. Should any biological male who says he is female be granted access to women’s spaces such as locker rooms, restrooms, and prisons? I’m for equality for all people. Good for you. Should any biological male who says he is female be granted access to women’s spaces, such as locker rooms, restrooms, prisons, and shelters for abused women?

A frequent response to these arguments involves taking great offense at the supposed implication that a transgender person should be suspect. No. The argument against self-identification laws like the Equality Act is not about laying suspicion on transgender persons. It’s saying that someone who seeks to harm women or girls could easily take advantage of such a situation—with legal protection.

She’s right about that. You had better start putting these hard questions to politicians. Our news media will not do it. They are sold out to gender ideology. A massive change is happening now in this country, and across the West generally. It is being sold as something it is not — and people who reject these lies are being stigmatized, and in some places are already at risk of legal jeopardy. If the Equality Act passes, there will be no place to hide, legally.

Read the whole thing. Welborn, who published this piece in Catholic World Report, reflects on the roots of this madness, and what we might learn from it. Gentle Father Martin, who enjoys the favor of the Gentle Pope Francis, is lying to people. He is probably lying to himself. So are a lot of well-intended people — gentle folks all, who don’t want any trouble, and who just want to be nice and respectable and caring. These lies carry unfathomably significant consequences. We have to stop using therapeutic euphemisms to describe what this is. In this sense, the vulgar missive from the Human Rights Campaign Foundation serves a valuable purpose: to put it in people’s faces what, exactly, the trans movement and their allies want.

A world where vaginas are called “front holes,” and cavities carved out of a man’s body where his penis and testicles once were are called “vaginas.” The inversion is no accident. Think, people!

UPDATE: Today the Court of Appeals in British Columbia has upheld the right of a minor child to receive transgender treatment without parental consent.

UPDATE.2: Reader Mrs DK, a parent of a transitioning adult child, comments:

When parents from the non-partisan Kelsey Coalition walked the halls of the House and Senate last year, it was the Dems who weren’t listening. They had parents who are lifelong Democrats, including lesbian and gay parents, talking to them about the blatant medical malpractice going on in the name of gender identity ideology. We mentioned the growing number of detransitioners, most of whom are same-sex attracted, many dealing with ongoing issues from rapid medical transition based on gender stereotypes. Their response? “I’ve never thought about it.” What we said did not match the HRC narrative, which owns them. Their response was a blank.

Check out the Kelsey Coalition website. They’re an interesting group — not political, just grieving parents who are watching their children wreck their bodies and their lives, and who are trying to wake us up to the reality of what’s happening.

The post The Insanity Of Transgenderism appeared first on The American Conservative.

Moralistic Therapeutic Judaism

A Jewish reader passes along Rabbi Yitzchok Adlerstein’s review of a new book examining how American Jews practice their religion today. The book is by Jack Wertheimer, a leading historian of American Jewish history. Excerpts:

The spoiler comes right at the beginning. “This book takes it as a given that Jewish religious life in this country has endured a recession” (p. 5). In this context, the term recession is an understatement. “Over two million individuals of Jewish parentage no longer identify as Jews, and many others . . . eschew identification with the Jewish religion, choosing instead to define themselves in cultural or ethnic terms. And outside Orthodox communities, rates of childbearing are depressed relative to the recent past, leaving observers to wonder who will populate Jewish religious institutions in the future” (p. 3).

If religion is on the decline, will a sense of peoplehood keep the Jewish enterprise afloat? “Peoplehood alone will not keep Jews engaged in Jewish life with any measure of intensity . . . Sacred religious practices, holidays, rituals, and commandments keep the Jewish people Jewish . . . Jewish families without religion don’t stay Jewish for very long” (p. 20).

The book is filled with evidence that non-Orthodox Jews are one tick away from total apostasy from the Jewish religion (N.B. Wertheimer is not Orthodox, but rather Conservative):

While a majority are not atheists or agnostics, the non-Orthodox are confused as to Whom God is. No wonder. One Conservative rabbi titled a High Holiday sermon, “Why Jews Should Not Believe in God,” and told his congregants that the images of God in our Torah that they cannot buy into should be upgraded to a kind of “container to hold our experience of life that is unnamable” (p. 31). A Reform rabbi who polled his congregants the day after Yom Kippur came to the conclusion that, “For them . . . God is a presence or power . . . not so much ‘above’ us in heaven as . . . ‘beside’ us or ‘within’ us . . . [Who] ‘acts’ when we act with God’s attributes, such as love, kindness, and justice” (p. 32). The replacing of the traditional belief in God with something else has led many rabbis “to sanctify the preexisting social and ideological commitments of their congregants by figuratively blessing them as somehow Jewish” (p. 39). Commandments per se are out. Rather, there is “a complete rejection of the notion that to be Jewish involves the acceptance of some externally imposed commandments . . . Internally generated rights and wrongs are all that matters” (p. 40). “The large majority of non-Orthodox Jews have internalized a . . . set of values . . . indistinguishable from those of their non-Jewish peers. A single commandment may have survived—one that was newly minted in the ‘80s: Thou shalt engage in Tikkun Olam”(p. 41).

Has any of this worked? Hardly. “Alas, it has not brought large numbers of members into synagogues, nor has it translated into other forms of religious participation” (p. 42).

This piece is really interesting. Wertheimer finds that Reform Judaism (the most progressive) has gone quite far away from the Jewish liturgical tradition, and gotten quite creative. It has not arrested Reform’s decline. The somewhat more traditional Conservative movement is declining even faster. Wertheimer’s research finds that Conservative Jews (he is part of the Conservative tradition) fail to give their children any but the most minimal understanding of what it means to be Jewish. Unsurprisingly, that little bit evaporates when they grow older. And why shouldn’t it? Modernity is the dissolver of all religion that isn’t infinitely malleable and focused on the Self. There are lessons there for Christians too, obviously.

One more quote:

Wertheimer does find evidence of vitality in new innovations outside of the old moribund denominations. He shows plenty of experimentation with new forms of engagement—religious start-ups, if you will. From the Renewal movement: “Picture 20 massage tables, with people lying down and being gently touched, with music playing. On Yom Kippur” (p. 240). From the Humanistic Judaism people: “Let’s rise and say the Shma. We are doing this as a tradition, not as a prayer” (p. 243). The Lab Shul reports that “Instead of using the baggage laden ‘God’, we’ve replaced it with terms like ‘source of life,’ and ‘deepest source.’” While these new ventures hold promise to their promoters, they all require urban environments. As millennials get older and move to the suburbs, Wertheimer wonders whether they can last. One of Wertheimer’s rabbinic interviewees asks:

How does a culture of narcissism[,] over[-]entitlement and personalization manifest itself in terms of Jewish communal engagement? How can an iPod generation find rigorous exploration of Talmud and Jewish literature compelling and life-sustaining? How can those taught to walk away/delete/unfriend on a whim be taught [and] . . . be stimulated to discover a spiritual practice that actually requires practice? Is there a way to cultivate a sense of obligation, enchantment, [and] spiritual hunger in a generation [that] is essentially able to log off or sign out in all other aspects of life? (p. 209).

There it is. And if you think that rabbi’s quote doesn’t apply to Christianity too, you’re daft.

OK, I have to mention one more thing here. Rabbi Adlerstein is an Orthodox Jew, the only form of Judaism that is thriving today. He cautions his fellow Orthodox against “I told you so”-ism:

There is no room for triumphalism or schadenfreude here. We are witnessing tragedy—pure, unmitigated tragedy. Millions of Jews are disappearing, but not because they ever had an opportunity to understand or experience the beauty of what they are giving up. The vast majority of them are victims of choices made by their forebears in earlier generations—and many of those choices were the consequences of the many manifestations of our long victimization through galut. [forced exile]

The rabbi says that the one thing Orthodox Jews should take away from Wertheimer’s study is that it is madness to try to update Judaism to fit contemporary mores. This has been a complete disaster for American Judaism.

Read it all. And think about this whenever progressives — such as we are dealing with in US Orthodox Christianity — say that we have to get with the times, and change our faith and practice to make it more suitable for contemporary America. But remember also the experience of the Conservative Jews: if you don’t both teach and practice your faith — that is, if faith is simply a matter of vague cultural and ethnic commitments and going to the temple on holidays — it will die in your children’s generation.

(By the way, you might not know that not all Orthodox Jews are the “black hat” types, who are typically called “ultra-Orthodox. Some are like Rabbi Adlerstein, pictured below: “Modern Orthodox”. They observe Jewish law strictly, but do not adopt the clothing traditions, and the separatism, of the ultra-Orthodox.)

Rabbi Y. Adlerstein (700 Club screengrab)

Rabbi Y. Adlerstein (700 Club screengrab)The post Moralistic Therapeutic Judaism appeared first on The American Conservative.

January 9, 2020

The Deadly Power Of Ideology

I’m at a conference this weekend, with a bunch of academics. I spent a couple of rich hours tonight talking with old friends who teach at Christian colleges. I wish — do I ever wish! — that most of you could have been sitting in on this. These are professors who are on the front lines, and what they report ought to blast to smithereens the complacent piety of most older American Christians.

Pornography is destroying a generation. It really is. One of the profs told me that his female students can’t get dates. Young men aren’t interested in relationships. Those who do ask women out tell them at the outset that they (the women) have to be cool with their pornography habits. From what I gathered, we are dealing with a generation of males who are failing to become men. Slavery to sensory input from screens — porn and video games — is keeping them stuck at around age 14. These are young males who attend conservative Christian colleges. This is a problem so far beyond our usual categories that we can scarcely comprehend it.

We talked also about how wokeness is conquering even conservative Christian colleges. I like to think that I’m well informed about this stuff, but even I am shockable. I said to one Evangelical college prof, “Most Catholic colleges are already lost. I get the idea that a lot of conservative Evangelical colleges are headed in the same direction.”

Said this man, “Yes. We’re rushing in that direction.” Agreement all around the table.

I won’t give details, because I don’t want to risk outing these professors. But trust me, this is everywhere. Pronouns, gender ideology, all of it. Being at a Christian school, even one whose identity is conservative, is no guarantee of anything. I’m serious. One of the professors I talked to had recently seen the Terrence Malick film A Hidden Life, about the anti-Nazi Christian martyr Franz Jägerstätter, which I saw this week, and absolutely adored. He too was blown away by the power of this film. We talked about how it was that Franz was the only one in his Christian village who understood exactly who Hitler was, and what Nazism was, and found the vision to grasp that, and to resist — even paying with his own life.

All of us talked about how difficult it is to read the times, and to resist the pressure to conform. You may be certain that even people who consider themselves devout, as did surely the people of Franz’s village, succumb to ideology. A different professor told me that his college’s senior administrators are good people, and faithful people, but they are blind to the power and the nature of ideology. They want to believe the best about others, a disposition that leaves them completely vulnerable to the attacks on the Christian core of the institution.

We talked further about how pervasive this is in churches too. I mentioned the recent case I highlighted on this blog, about an Orthodox parish priest who published an essay stating his “strong conviction” that the Church ought to bless gay Orthodox committing to each other as couples, and keeping their sex lives within those committed partnerships. This caused a big uproar — I wrote about it here, here, and here — and ended up with his bishop correcting him, and causing him to retract what he wrote.

Since I wrote about this case, I have received some highly critical e-mails from fellow Orthodox Christians who know the priest, and who are upset with me for being too hard on him. I don’t believe at all that I was too hard on this priest. You publish a scandalous opinion about a vital issue in the life of the church in One of the critics, himself a priest, said that the priest I criticized really had gone too far, and was imprudent in publishing. But, he said, a lot of the rhetoric attacking the priest was alarmist and vicious — I got the sense he included my writing in this criticism — and that the laity ought to calm down and trust the hierarchy to handle it.

Surely this priest is correct about the overheated rhetoric you see from Very Online Orthodox. I don’t read Orthodox blogs, because I can’t stand that kind of talk. It never leads anywhere good. It’s real easy for Christians of all kinds to cut loose behind the veil of anonymity with rhetoric they would never say publicly under their own names.

That said, in the main, I strongly disagree with this priest. I think there is a fundamental, and critical, failure on the part of many good-hearted clergy and laity to understand the nature and the seriousness of the crisis. It is not only about LGBT issues, no question, but LGBT issues are the sharp tip of the spear. I strongly believe that there are plenty of decent, fair-minded people who simply do not understand the power of ideology, and what it’s doing to the faith.

Forgive me, but I need to digress here. It’s important.

The Orthodox Church in this country has lots of converts who found came to Orthodoxy after being burned out in churches that have surrendered to modernity in a number of ways, particularly on sexual teaching — and most especially on homosexuality. I wrote earlier in this space that I found Orthodoxy after I my Catholic faith had been shattered by covering the sexual abuse scandal within Catholicism. The unwillingness of bishops, and many priests, to deal honestly and forthrightly with sexual corruption — not just abuse, but sexual misconduct — among the clergy, and to confront the sexual disorder among the laity, was extremely discouraging to me. Eventually it led me to quit believing in the ecclesiological claims Catholicism made for itself. I didn’t come to Orthodoxy because it was orthodox on sexual morality — if that’s the only reason you go to a church, there are others you can go to that are less demanding in other ways, and certainly less alien to mainstream American life — but that was the catalyst that got me going on the journey into Orthodoxy. As painful as it was to lose my Catholic faith (and no kidding, it was the most painful experience of my life, and I say that as someone who has buried his sister and his father, and gone through a lot of suffering in other ways), I give thanks to God for it, because of the way He allowed me to be crushed, and to have my intellectual pride broken. Because of that shipwreck of my spiritual life, I found Christ in the Orthodox faith, and it changed me for the better.

When I became Orthodox, I did not come in with the idea that there was any church in which one could escape the brokenness and sinfulness of the world. I certainly did not come in thinking that the institutional Orthodox church would be without problems. One wound I will always carry with me is the inability to fully trust the episcopate to do the right thing. I’m not proud of that, nor am I ashamed of that. It’s just there. It’s wisdom, if wisdom it is, born of hard experience.

I came into the Orthodox Church in America (OCA) in 2006, a time when the church was beset by a long-term administrative crisis, mostly having to do with money, as I recall. The problems were clearly recognized, but the Synod (the bishops, together) was unable to reform itself. At the time, I remember telling other Orthodox that they were lucky that the Church’s problems had to do with money, not sex. But I came to see that the fact that the bishops could not or would not fix what was broken was taking a real toll on the laity. I won’t recount all that drama — a drama that I allowed myself to be drawn into, as an activist, taking a role I later regretted, for reasons that don’t bear discussing. The point I want to make here is simply that clericalism — the idea that the clergy knows better, and that the laity should behave with docility and trust — is present in all churches, and is destructive, whether or not that destruction takes the form of tolerating sexual corruption, financial corruption, or what have you.

Read this short piece by the Catholic priest Raymond de Souza, titled, “We used to believe the bishops told the truth. What happened?” Excerpt:

It is not hard to find priests – to say nothing of journalists – who are inclined not to believe anything their bishops say without corroboration. And bishops know it, which is why reviews of diocesan files are entrusted to law firms, or retired judges, or former law enforcement personnel.

Any data provided by a bishop is suspect without independent verification.

Because the Catholic bishops, and those who served them, lied. And they lied. And they kept lying. They lied to protect themselves, they lied to protect the reputation of the Catholic Church. They just lied. Many of them don’t know how not to lie. More de Souza:

In October, journalist Sandro Magister asked at a Vatican press conference about prostrations in regard to the “Pachamama” in the Vatican Gardens. Paolo Ruffini, prefect of the Dicastery for Communication, insisted that there were no “prostrations”, despite his own department providing video footage of same. His deputy at the press conference applauded his denial, giving the whole affair a rather Soviet feel. Magister promptly pointed out that Ruffini had “inexplicably denied” the direct evidence contained in the footage.

Not all bishops are liars, heaven knows, but in the Year of Our Lord 2020, you would have to be a stone-cold fool to trust what a bishop or the institution tells you at face value. This is a problem that has been most acute in the Catholic Church, but only the terminally naive think that it’s a problem limited to the Catholic Church. It’s how institutions work. The Orthodox hierarchy (and every church’s hierarchy) may be honest and upright and even holy, but they live and move and have their ministry in a world where people have become deeply mistrustful of authority, especially religious authority. It is not the fault of the good bishops and priests that this has happened, but they have to deal with it like everybody else. This is simply the reality of church life today. You do not get the benefit of the doubt as a clergyman.

To be clear, neither the Catholic Church nor the Orthodox Church are congregational polities. We are hierarchical churches, and always will be, and always should be. We believe that’s how Christ ordered the Church. The problem with clericalism is that it allows people, both clerics and laity who adhere to it, to think that the Church is the clergy, and that the laity are in some sense second-class citizens whose job it is to be quiet and let the clergy do what it wants to do. Obedience to lawful authority is what is required of us — I don’t question that — but it is no virtue to be silent when priests and hierarchs are failing to teach and uphold right belief and right practice. In fact, it’s a vice. We can err when we speak up hatefully, or in some other disordered way, but we also err if we fail to speak up at all.

I’m sorry to be so personal here, but this is something I learned the hard way, and I’m not about to yield on it.

There is a such thing as prudence. For example, like more than a few Orthodox, I am aware of a situation in which the pastor of a large Orthodox church is living in a scandalous sexual situation with another man, a cleric. Their bishop cannot possibly be in the dark about it. Churchmen who are much closer to the situation than I am have said to me that they can’t understand why the local bishop won’t act. Me neither — but that hot mess is not in my diocese, I have no direct knowledge of it, and to the best of my understanding, neither gay cleric has publicly advocated for something heretical. If I was in that congregation, or diocese, I would feel more obliged to find out the facts, and then act. But I don’t, so I don’t. Again, prudence is required for these things.

But prudence is not a synonym for quietism. Progressive priests and others who want to change the church in damaging ways count on the docility of conservative laity and conflict-averse bishops to get their agenda through. The churches today are being overwhelmed by ideology: gender ideology, the ideology of Niceness, Moralistic Therapeutic Deism, and so forth. The old ways of leading churches, and conducting church business, are as effective in the face of this ideological blitzkrieg as the Polish cavalry was in the face of the Wehrmacht. To switch the metaphor, we are being served poison, and being told by tone-policemen that it’s rude to complain too loudly about the meal.

As I said, lots of us converts in the Orthodox Church came out of churches broken by heretical teachings that were either promoted by bishops, priests, pastors and others in authority, or that went unchallenged by those in authority. Especially on homosexuality. We have seen with our own eyes what happens when heterodox activists, both clerical and lay, establish a beachhead within institutions of the Church — and we are not going to stay silent while the same thing happens to the Orthodox Church. There are cradle Orthodox who have watched this same thing happen to the Catholic Church, and to a number of Protestant churches, and who understand that if they’re going to protect the Orthodox faith, they cannot let the same thing happen here. We live in a time and place where defending Christian orthodoxy on this issue is increasingly unpopular. Still, we have to do it. As Kierkegaard said, Christ does not want admirers; he wants followers.

I had an e-mail exchange with a parishioner of the priest whose pro-gay coupling essay I criticized, who reprimanded me respectfully but harshly for writing about the case and, in his view, hurting the priest without having phoned him first and tried to talk it out. The parishioner said that I ought to have hosted a podcast or YouTube chat with the priest to talk about his opinion here. I reject this view. In fact, I don’t even comprehend what he’s saying. I had no intention of causing personal pain to this priest, heaven knows. But for one thing, I don’t believe that there is any fruitful dialogue to be had about his proposal (and in fact, “dialogue” is a wedge strategy for pro-LGBT activists, as we have seen for decades now in the experiences of other churches). For another, if someone publishes an essay in a newspaper or online, they are by that fact offering it up for public discussion, including critique. None of you readers owe me a phone call or e-mail to talk over this column or anything else I write before you critique it. That’s just not how it works. You do owe me the respect not to misrepresent my words intentionally, but beyond that, I have no right to expect you not to criticize my words if you believe that I am wrong. If I don’t agree, then I shouldn’t publish. We are grown men and women here, are we not?

A different reader, an Orthodox priest, wrote to say that we Western people in Orthodoxy are not very well practiced in dealing respectfully with authorities who disappoint. Oh, man, straight fire from me on that. Again, I fully agree with the priest that ugly, hateful rhetoric has no place in these debates. But if being very well practiced means mewling docility while priests and bishops allow the faith to be traduced in consequential ways, then bully for clumsy, rude barbarians.

It has taken the conservative Catholic laity a long time, and a lot of suffering, to wake up, but it’s starting to happen in some places, though the dissent has become so entrenched that many bishops don’t even try to discipline their flocks (for example, you will never see Cardinal Timothy Dolan of New York say boo to Father James Martin, the pro-LGBT Jesuit activist). Is this what we want to see in American Orthodoxy? If not, then speak up without fear. Do it without being insulting, vicious, or cruel, and do it as charitably as you can manage — but by all means do it. It’s important. This is the future of our children, and their children, that we’re talking about. Managing for moral and theological decline is not an acceptable leadership strategy from the Church’s ruling class.

I have been critical in this space of some of George Weigel’s writing, but when he’s right, he’s right. In his most recent piece for First Things, Weigel writes:

Is there a single example, anywhere, of a local Church where a frantic effort to catch up with 21st-century secularism and its worship of the new trinity (Me, Myself, and I) has led to an evangelical renaissance—to a wave of conversions to Christ? Is there a single circumstance in which Catholicism’s uncritical embrace of “the times” has led to a rebirth of decency and nobility in culture? Or to a less polarized politics? If so, it’s a remarkably well-hidden accomplishment.

There is, however, evidence that the offer of friendship with the Lord Jesus Christ as the pathway to a more humane future gets traction.

Shortly after last October’s Great Pachamama Flap, I got a bracing e-mail from a missionary priest in West Africa. After expressing condolences for my “recent Roman penance” at the Amazonian Synod (which had featured a lot of politically-correct chatter about the ecological sensitivity of indigenous religions), my friend related an instructive story:

You’ll be happy to know that last year, when one of our villages invited me to come and help them destroy their idols and baptize their chief, we did not, before doing so, engage in any “dialogue with the spirits,” as was so highly praised in the [synod’s working document]. There was no Tiber to throw [the idols] in, so a sledgehammer and a fire had to suffice. Somehow the village managed to survive without such a dialogue, and in fact they have invited me back . . . to celebrate the one-year anniversary of the great event, and to bless a cross that will be set up in the village as a permanent reminder of their decision.Three weeks ago, the local archbishop wrote those same villagers, telling them of his “immense joy” that, the year before, they had “turned away from idols in order to turn resolutely to the Living and True God. . . . You have recognized in Jesus Christ the Way, the Truth, and the Life. Open wide your hearts to him . . . and always conquer evil with good.”

The world is on fire. You might think that these new ideologies are the endearing product of warming hearts, but they are coming from the flames that are consuming the faith. We need fewer admirers — of the system, of the process, of sweetness and light — and more Franz Jägerstätters: Christians who know what the Truth is, and Whose they are, and who are not willing to succumb to the spirit of the age, or tolerate it in the Church. For if we lose the Church, where will we stand?

Last night I received an e-mail from a reader in Australia who lived in Czechoslovakia under communism, and had experience with the underground church there. He recalls:

I look forward to reading your book on the Slovak underground. It is a story that deserves to be told. There was a hunger for God when I was there which I attributed in no small part to the enormous disillusionment with communism. Disillusionment with materialism may take another couple of generations. The Church in those times offered people an alternative worldview. My young Catholic friends in the university, in particular, demonstrated great courage and faith.

This. This right here is what we need: what the underground church of Slovakia had. We don’t need a Christianity that merely baptizes the post-Christian status quo. To hell with that.

The post The Deadly Power Of Ideology appeared first on The American Conservative.

Bébé, King Of The Cajuns

Days before the national championship, Sports Illustrated canonizes LSU head football coach Ed Orgeron — but in this case, it’s not false hagiography. It’s all true. Excerpts:

Ed Orgeron used to sack oysters, shovel shrimp and guzzle beers here. His grandfather operated a bayou ferry, and his mother grew up trapping and skinning muskrats. He comes from a long line of hunters and fishers, tug boat operators and oil field workers, gumbo-makers and jambalaya-cookers. Most know him on the bayou, not as Coach O, but as Bébé, a French word meaning baby, a nickname handed down from his father.

On Monday night about 50 miles north in New Orleans, Bébé will lead his home-state’s flagship, LSU, into the national championship game against a perennial powerhouse, Clemson. For many in the college football industry, this is an unfathomable outcome, that a one-time bar-brawling drinker who flopped in his one head-coaching stint would captain a team to a 14–0 record and an SEC championship. For those here on the bayou, this is what they always expected, that their barrel-chested, gravelly-voiced Cajun brother would lead the Tigers to the promised land.

“They made fun of him, (Paul) Finebaum and them, and he’s making them pay for it now,” says Dean Blanchard, a 61-year-old seafood tycoon from the bayou. “Look at the successful Cajuns we have here. They don’t have a clue of what the Cajuns are capable of. What I want to come from this is respect for the Cajun culture.”

More:

Monday’s game is about more than some championship ring. It’s about a subsection of people, like their native son Bébé, persecuted and neglected, their accents mocked and their intelligence questioned. The Cajuns are accustomed to this. After all, these are the ancestors of the French-speaking Acadians who the British forced from their Nova Scotia home in the mid-1700s. They were sent fleeing to French-settled Louisiana, establishing a base on the bayou and later developing a reputation as experts at the seafood and oil field industries, not-so-easily blending into American life.

In fact, it took more than 200 years—and a lawsuit—for the U.S. government to recognize them as a national ethnic group in 1980, and in the early 20th century attempts were made by American teachers to suppress their language. But the Cajuns are an enduring and passionate people, bonded by their ancestral ties and their rich, unique culture—food and festival at its core. They are an emotional people, too, unafraid to cry tears of joy and grief, a welcoming breed to outsiders but also terribly defensive of their own stock. “Cajuns are hard workers,” says Henry LaFont, a 65-year-old attorney raised on the bayou. “They’ll give you the shirt off their backs, but don’t cross them.”

The story talks about the really hard times that have befallen the people of South Lafourche. The economy is nosediving. Oil industry going down, seafood industry in steep decline. The place is depopulating, and they know that they’re one big hurricane away from devastation.

This is one reason they see Ed Orgeron as a beacon of hope. He’s been flat on his back, and come back hard. Earlier in his life and career, he was drunk at a bar in Baton Rouge, and head-butted a bartender. He lost his coaching job. Couldn’t get hired. But then, Nicholls State University, in Thibodaux, a Lafourche Parish town, called to offer him a position. And that’s where the comeback started. He owed that to his network of friends who argued that Bébé deserved a second chance. More:

Back he went to the bayou. There, on a front-yard swing with his father, the two discussed his future. Well, Big Ed told his son, maybe we should try something else other than coaching. And then… “the phone rings,” Orgeron recalls. “We have a loud ringer. You could hear the phone from inside.” On the other line was Rick Rhoades, the coach at Nicholls State, the regional college in Thibodaux, a short drive from Larose. He offered Bébé a job.

A day later, Orgeron was back on the practice field as a volunteer assistant. “He was very candid about what happened at Miami,” says Rhoades, 72, retired now and living in Alabama. “He’d basically lost his career. I like to think we were able to crack the door and get his career back. He’s taken it and run with it.” Rhoades, not from the area, was connected to Orgeron through the Cajun community. One member led the charge: LaFont, the attorney from Larose and an old beer-drinking buddy with the coach. He remembers encouraging Rhoades to hire Orgeron during a meeting in the coach’s office. By the time LaFont made it to Orgeron’s home that day, Rhoades had called with the news. Orgeron swung open the door and wrapped his burly arms about LaFont screaming, “HANK, I GOTTA JOB!” To this day, the coach hasn’t forgotten about it. LaFont hasn’t either. “What if Coach Rhoades hadn’t been in his office that day?” he says. “What if he didn’t want to see me? The cards fell right.”

The Cajuns, in no real surprise, had Orgeron’s back. “They really are remarkable people,” says Rhoades. “They either love you or hate you. There’s not much in between. There was some orchestration that got Ed to us. A lot of people were involved. He’s a local guy that had fallen on hard times. One thing about Cajun people, if one of them has a hard time, they rally. It’s been fun to watch him over the years develop. Don’t let that down-home Cajun banter fool you—he’s smart as a whip.”

One more, about how hard Orgeron grew up:

Edward Sr. held various jobs through the years, depending on the season and the economy. When the oil industry dipped, he turned to tug-boating, and back and forth he went. He retired as a supervisor of the Lafourche Telephone Co. Coco estimates the family earned about $3,000 a year during Bébé’s childhood. “Sometimes we had no money,” she says, “but, baby, we had some good times.” There were bad times, too. Coco got her name from her brother Wiley, who she delivered cocoa to while he lay bedridden, a victim of bone cancer. Coco’s mother lost three children, including twins, and of her husband’s 13 siblings, two drowned and another two burned to death. Life on the bayou could be dangerous. Sports were always an outlet.

Junior was hell-bent on proving everyone wrong. He’d shoot hoops on a dirt court in the yard late into the night, and when Coco would ask why, he’d tell her, “Can’t make the layup, can’t be on the team.” He was obsessed and not just with football and basketball. Junior threw the shot put and discus and played baseball. He didn’t let injury get in the way of practice or play. While in secondary school, he broke his leg while falling off a boat. Days later, he played front-yard football in a full-length leg cast that the doctor re-casted three different times, Coco says. “He never stopped. Never, never,” Coco shakes her head. “Let’s say you’re not the best at something. Well guess what that boy is going to do? Practice, practice and guess what? He will beat you eventually. He just had that heart about him.”

Read it all. What a superb piece of journalism. The author is Ross Dellenger.

Somebody sent me a link yesterday to a 2019 USA Today story about the 50 worst US cities in which to live. Five of them were in Louisiana — none were Cajun towns, incidentally. Poverty, crime, joblessness are the main reasons. My state could use some hope. Thanks, Bébé. South Lafourche needs you. We all need you.

The post Bébé, King Of The Cajuns appeared first on The American Conservative.

‘Epstein Didn’t Kill Himself’ File

Nope, nothing suspicious here at all:

In the latest screw up in Jeffrey Epstein’s death case, federal officials revealed Thursday that video of the cell where the pedophile reportedly made his first suicide attempt was accidentally destroyed.

The surveillance footage was requested by Epstein’s cellmate, accused killer ex-cop Nicholas Tartaglione, who is hoping it will show he “acted appropriately” and earn him a break at sentencing.

Last month, federal prosecutors said the video had been found. But in a letter to the judge on Thursday, they said it turns out that staff at the Metropolitan Correctional Center “inadvertently preserved video from the wrong tier,” and the video from the correct one “no longer exists.”

“60 Minutes” had a report the other night on the Epstein case. New York magazine offers five takeaways from it. The original “60 Minutes” report isn’t online and embeddable yet, but this five-minute extra gives you basically what you need to know. It doesn’t prove that Epstein didn’t kill himself, but it does raise serious questions. Note especially the oddity of the three bone fractures, and the fact that the noose identified by the medical examiner as the one Epstein used to hang himself does not match the description given of the scene in the official report. Also, pathologists said that without an image of Epstein’s body as it was found — and those images are not believed to exist — some questions will not be answerable.

The post ‘Epstein Didn’t Kill Himself’ File appeared first on The American Conservative.

Once Again, Republicans, Over The Brink

I heard Trump’s statement about Iran yesterday morning as I was driving. I thought it was uncharacteristically sober for him, and was glad for that. I had figured that we would be in a full-on war the day after.

And then, after the Trump administration gave the Senate a private briefing on Iran, Sen. Mike Lee blew up. Look at this:

Most Republican senators on Wednesday left an Iran briefing from top Trump administration officials satisfied. Not Mike Lee.

“The worst briefing I’ve seen — at least on a military issue — in my nine years” in the Senate, said the Utah Republican.

Lee fumed that the officials warned against even debating legislation to restrict President Donald Trump’s authority to strike Iran — blasting their comments as “un-American” and “unconstitutional,” not to mention way too short.

“They had to leave after 75 minutes while they’re in the process of telling us that we need to be good little boys and girls and run along and not debate this in public,” Lee said of the group that gave the briefing, which included Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, Defense Secretary Mark Esper and CIA Director Gina Haspel. “I find that absolutely insane.”

The briefing, which centered on Trump’s decision to kill top Iranian general Qassem Soleimani, has prompted both Lee and Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) to back a resolution offered by Sen. Tim Kaine (D-Va.) forcing the president to stop military action against Iran if not authorized by Congress except in a case of an imminent threat. Democrats need to win over two more Republicans for the resolution to pass and Kaine could bring it to the floor as soon as next week.

“I walked into the briefing undecided. I walked out decided, specifically because of what happened in that briefing,” Lee said.

Amen to that. After the lies that got us into Iraq, after the lies that three administrations have told about Afghanistan, the Trump administration has the gall to tell members of Congress that it can’t debate these matters in public?! And Mike Lee and Rand Paul (who was at Lee’s side when he made these remarks) are the only Republicans with the stones to come out and say that is unacceptable?!

Here’s some of Lee’s commentary. Watch it — this guy is furious, and rightly so:

I want you to read my TAC colleague Scott McConnell’s essay “A Trump Voter’s Lament,” which is elsewhere on the site now. In it, he talks about how he voted for Trump, and has supported Trump all along. He mentions a locker room conversation he had just over a year ago with the president, in which the president told him that there would not be war with Iran, that it was all just talk. (You really have to read the piece for the details of that conversation, which McConnell is only now making public.) And now? Here’s McConnell:

Whatever threatening or waging war might do for Trump politically, the reality of it would be a disaster. No one knows where we are precisely on the escalation escalator. Perhaps Iran will not respond with more than Tuesday’s errant rockets to the assassination of one of its leaders. But one already sees flourishing on the Right all the chest-beating rhetoric which one hoped a Trump presidency dampen; with the critical and important exception of Tucker Carlson, Fox News, the important conservative mass media platform, is in its 2002 mode all over again, as if nothing has been learned from the Iraq war. Once again patriotic Americans are rallying to the absurd notion that the turmoils of the Mideast can be traced to one evil man or evil regime, that a regime change war will solve the problem.

Vaporized from public memory is the fact that Iran, including the leaders now most robustly demonized, played a critical role in organizing the paramilitary militias who defeated ISIS. And if Trump somehow remains aware that occupying Iran with troops—overwhelmingly the sons and daughters of his red state voters—wouldn’t go well, his proposed alternative to occupation of Iran is apparently to commit war crimes against the archaeological legacy of ancient Persia, smashing with drones cultural treasures which are less the property of the Iranian regime than they are of all humanity. Some of his cheerleaders advocate turning Tehran into 1945 Dresden. It is simply obscene.

There was an argument during the last campaign, expressed most notably by Michael Brendan Dougherty, that the worst possiblething for those who wanted a different kind of American conservatism—an end to stupid wars in the Mideast, a more controlled immigration flow, an industrial policy that valued something other than cheap goods and “free trade”—might be a victory for Donald Trump, who campaigned for all of these things. Whether he believed in them or not, Trump recognized that this is what many voters wanted, that this was an open political lane to run in, an untapped yearning. I think, to an extent, he did believe in them, but had no idea, no real plan how to bring them about.

Faced with unrelenting hostility from the Democrats, the media and the permanent class ofBeltway bureaucrats which began before he took office, and no real base in the organized Republican Party, he floundered. No wall was built. No immigration legislation was passed. No grand and necessary Rockefellian infrastructure initiatives were initiated. He has hired to key positions Beltway types who had nothing but contempt for him, and they have led him down well worn paths. One of those paths leads to a major war with Iran, an obsessively pursued project of the neoconservatives since long before 9/11.

Impeachment makes taking that path more plausible. Indeed, Trump could reasonably see it as the best possible way out. It’s now hard to see how a Hillary Clinton presidency could have turned out worse.

The most depressing thing about the piece is McConnell’s observation that patriotic Americans are once again rallying themselves to go to war in the Mideast. Why is every conservative in the country not standing with Mike Lee and Rand Paul? I can’t understand it. Are we really so willing to be suckered into war again?

Tucker Carlson, God bless him, is holding the line on Fox. From Buzzfeed:

But those with real influence, most notably Carlson, have not. Carlson has become an increasingly influential voice for anti-interventionism on the right and is very popular among the Trump base. And according to a source with knowledge of the conversations, Trump told people that he had watched Carlson’s show and it had affected his view on the Iran situation.

Here’s Tucker’s segment from last night, calling on the US to get out of Iraq. Tucker Carlson might well be the best chance this country has of avoiding another catastrophe in the Middle East.

UPDATE: “Trust us,” they said.

Mike Pence urges public to blindly trust Trump: "To protect sources & methods we're simply not able to share with every member of Congress the intelligence that supported the president's decision … [but] I can assure your viewers that there was a threat of an imminent attack." pic.twitter.com/r5DnB5U7Uh

— Aaron Rupar (@atrupar) January 9, 2020

UPDATE.2: Here, from an interview Sen. Lee gave to NPR this morning, is a big reason why he erupted yesterday:

RACHEL MARTIN: What kind of hypotheticals were you putting to them in hopes of understanding when the administration sees a need for Congressional authority?

SEN. MIKE LEE: As I recall, one of my colleagues asked a hypothetical involving the Supreme Leader of Iran: If at that point, the United States government decided that it wanted to undertake a strike against him personally, recognizing that he would be a threat to the United States, would that require authorization for the use of military force?

The fact that there was nothing but a refusal to answer that question was perhaps the most deeply upsetting thing to me in that meeting.

Do you see? The Trump Administration reserves to itself the right to decide to assassinate a head of state — a clear act of war — without consulting Congress. And so far, Mike Lee and Rand Paul are the only Republican senators who have a problem with this. Greg Sargent writes in the Washington Post:

Obviously, this was an extreme hypothetical. But the point of it was to discern the contours of the administration’s sense of its own obligation to come to Congress for approval of future hostilities. And it succeeded in doing just that, demonstrating that they recognize no such obligation.

“It would be hard to understand assassinating a foreign head of state as anything other than an act of war,” Josh Chafetz, a Cornell law professor and the author of a book on Congress’ hidden powers, told me. “It’s appalling that executive-branch officials would imply, even in responding to a hypothetical question, that they do not need congressional authorization to do it.”

But this is where we are. One more thing from Sargent’s piece:

By the way, it requires restating: Former president Barack Obama abused the war power as well, and far too many congressional Democrats went along with it. Congress has been abdicating its war-declaring authority for decades.

UPDATE.3: I hope it’s not true that in a democracy, we get the government we deserve:

Sarah Huckabee Sanders said she couldn’t “think of anything dumber” than allowing Congress to authorize war, seemingly unaware that the U.S. Constitution specifically gives the legislative branch that exact power https://t.co/5eulqvleU1

— The Daily Beast (@thedailybeast) January 9, 2020

UPDATE.4: Oh, give me a freakin’ break! As you can tell, I’m against Trump’s bellicosity here, but the Iranians shot down a passenger jet because of their incompetence … and this guy is going all “blame America first” (or at least failing to blame the regime that actually shot the plane down):

Innocent civilians are now dead because they were caught in the middle of an unnecessary and unwanted military tit for tat.

My thoughts are with the families and loved ones of all 176 souls lost aboard this flight. https://t.co/zWaVgWxfdL

— Pete Buttigieg (@PeteButtigieg) January 9, 2020

The post Once Again, Republicans, Over The Brink appeared first on The American Conservative.

January 8, 2020

The Megxit

Gotta love the British tabloids. They’re calling today’s shock announcement from Prince Harry and Megan Markle the “Megxit.” This is not only funny, it also shows that they — and most likely the British public — are blaming the American for ruining their Harry. A.N. Wilson puts the knife in with laser-like precision:

This can only be described as an abdication. Meghan and Harry have in effect withdrawn from their royal duties and will spend a large part of their future lives in North America.

It is hard not to feel history repeating itself. Even the wedding car that drove the future Duchess of Sussex to be married to Prince Harry in St George’s Chapel, Windsor, was the very car that drove Wallis Simpson to attend the funeral of her husband, the former Edward VIII.

In 1936, the immensely popular, lovable new king had renounced the throne because he wanted to marry Mrs Simpson, an American divorcee.

That event is seared into the consciousness of the Royal Family: it has obsessed them ever since.

There you have it. Meghan is Wallis.2. More Wilson:

The truth is that this charming, intelligent, beautiful woman hadn’t a clue what the monarchy really is, or what role minor members of the Royal Family have to play in public life.

For his part, Harry perhaps didn’t fully understand his own role as a younger son. Both seemed oblivious to the fact that the British monarchy is a delicate constitutional miracle, not a vehicle for its members to press home their views on the subjects that interest them, however noble.

A minor royal such as Harry or Meghan (Harry is now sixth in line to the throne) essentially exists to be on standby for public engagements that senior royals are too busy to fulfil. They must also keep their views private.

Yet Meghan, as befitting her role as a socially conscious and ambitious career woman, wanted her views on everything from climate change to women’s rights to be centre stage.

Wilson goes on to say that this is probably for the best. The “Royal Family” is too unwieldy an institution to survive in contemporary times. It needs to be smaller and sleeker, he says. This seems right to me.

Still, as an American who is fairly traditionalist about these things, I find her behavior to be appalling, and am sorry he got mixed up with a Hollywood celebrity. Anybody who has given a moment’s thought to the British royal family — or anyone who has watched even one season of The Crown — knows that it is a gilded prison. Nobody chooses to be born into such a family, which belongs to the nation, not to themselves. You can’t help feeling sorry for them. I hold the unpopular opinion that Charles, for all his faults, is a really interesting man, and I hope his reign is a long one (see the 2012 essay I wrote about him). If the only thing you know about Charles is what the media have written about him, then you are badly misled about the man.

For example, he is the royal patron of the Temenos Academy, an organization that promotes study in perennialist philosophy. I am not a perennialist, but I find people who are to be pretty interesting and sympathetic. Take a look at the Temenos Academy’s basic principles. You may or may not like perennialism, but I am very glad that the future King is favorably disposed towards this traditionalist way of approaching the world. As I wrote in that 2012 piece:

To most Americans, the Prince of Wales is best known as a pop-culture icon and tabloid figure, a royal celebrity who married (and divorced) Diana Spencer, fathered Prince William, and gallivanted scandalously with Camilla Parker-Bowles, now his wife. What is less known, at least in this country, is that Prince Charles, 63, has spent much of his life, and indeed his fortune, supporting, sometimes provocatively, traditionalist ideals and causes.

The heir to one of the world’s oldest monarchies, a traditionalist? You don’t say. But Charles’s traditionalism is far from the stuffy, bland, institutional conservatism typical of a man of his rank. Charles, in fact, is a philosophical traditionalist, which is a rather more radical position to hold.

He is an anti-modernist to the marrow, which doesn’t always put him onside with the Conservative Party. Charles’s support for organic agriculture and other green causes, his sympathetic view of Islam, and his disdain for liberal economic thinking have earned him skepticism from some on the British right. (“Is Prince Charles ill-advised, or merely idiotic?” the Tory libertarian writer James Delingpole once asked in print.) And some Tories fear that the prince’s unusually forceful advocacy endangers the most traditional British institution of all: the monarchy itself.

Others, though, see in Charles a visionary of the cultural right, one whose worldview is far broader, historically and otherwise, than those of his contemporaries on either side of the political spectrum. In this reading, Charles’s thinking is not determined by post-Enlightenment categories but rather draws on older ways of seeing and understanding that conservatives ought to recover. “All in all, the criticisms of Prince Charles from self-styled ‘Tories’ show just how little they understand about the philosophy they claim to represent,” says the conservative philosopher Roger Scruton.

Scruton’s observation highlights a fault line bisecting latter-day Anglo-American conservatism: the philosophical split between traditionalists and libertarians. In this way, what you think of the Prince of Wales reveals whether you think conservatism, to paraphrase the historian George H. Nash, is essentially about the rights of individuals to be what they want to be or the duties of individuals to be what they ought to be.

Prince Harry has made his choice on the wrong side of that divide, in my view. Too bad. The thing is, the Sussexes will now be trading on the cultural capital they have as members of the Royal Family, even though they prefer not to assume the duties of same. Not my business as an American, but somehow, that rankles.

The post The Megxit appeared first on The American Conservative.

On Not Getting Malick’s Masterpiece

Last night I saw Terrence Malick’s new film A Hidden Life, about the anti-Nazi Catholic martyr Franz Jägerstätter, and as you can see from my initial remarks, I was blown away by the movie, which I consider to be a miracle, and the finest evocation of the Gospel ever committed to film.

The more I think about it, the more frustrated I am by the inability of many secular critics to understand the film. I am not saying “like” the movie; I’m talking about simply understanding what Malick is trying to say here. It’s perfectly fine to dislike a film, even as you understand clearly what the filmmaker is saying. I’m saying that Malick is speaking a language that modern people in this post-Christian culture simply do not understand (and I am including some Christians in this complaint too). There is a profound lesson in this for all of us. Bear with me here.

There are quite a few such reviews, but I’m going to let Peter Travers’s negative take in Rolling Stone stand for all of them, as his take is in line with most other negative reviews. Excerpts:

Cue the storm clouds and the Nazis who, in 1940, demand that all able-bodied Austrian men must join the war effort and take an oath of loyalty to Hitler. The village mayor (Jürgen Prochnow) drinks the Kool Aid. Franz is not so sure, but reports to military training as directed. Still, when the time comes to go to war, our hero resists on moral grounds and is hauled off to prison. Meanwhile, his wife and children are treated as pariahs in the village. You’ll wait in vain for the moment when Franz, the good Christian, explains himself. Malick, always stingy with dialogue, simply observes as the character holds to his principles and everyone from the local bishop (Michael Nyqvist) to a pair of oddly sympathetic Nazis, (Matthias Schoenaerts and the late Bruno Ganz), urge him to sign the oath that will free him at the cost of his conscience.

The real Jäggerstätter was beatified as a martyr by Pope Benedict XVI in 2007, but the role as conceived by Malick gives the willing and able Diehl very little to help us understand the man behind the saint. And the sweeping, suitable-for-framing vistas provided by cinematographer Jorg Widmer only add to the frustration. Malick has created a war film without a single scene of war, of Jewish persecution, of the thought process that helped Franz hold steadfast. It’s one thing to fashion a film about one man’s blind faith; it’s another to keep audiences in the dark about the fundamentals that made him human.

To be fair to Travers, I think more than a few Christians would come away with the same general take. And, to be honest, this is a genuine problem with Malick’s film: it is not widely accessible to a post-Christian audience — including post-Christian Christians.

Here’s what I mean. Malick is an extraordinary poet of cinema, and like the best poets, he calls his reader out of himself in an attempt to understand his art. Watching a Malick movie is not an easy experience, in which everything is explained for the viewer. That is not to say that his meaning is obscure! It’s only that it is buried deep within mystery, and can only be experienced indirectly, sacramentally. You never once hear the word “Jesus” in this film — yet Christ saturates this picture! There is not an altar call, nor is there a straightforward apologetic explanation from Franz of “this is why I am doing what I’m doing” — yet every word and every image conveys the message to those with ears to hear and eyes to see.

But we are deaf and we are blind. I say that not as a criticism (except of Christian viewers), but as a descriptive observation. For example, when the Austrian villagers are working their wheat fields together, there is a moment in which one of the outcasts, Fani’s sister, stands among them winnowing grain with a basket — that is, separating the useful part of the wheat from the worthless bits. To the eyes of a Peter Travers, this is just one more picturesque, pointless digression: oh look, one more boring shot of peasants at labor. But a Christian formed by the Bible will see this and instantly be reminded of Matthew 3:12, the word of John the Baptist at the River Jordan, before Jesus presents himself to be baptized:

“His winnowing fork is in his hand, and he will clear his threshing floor, gathering his wheat into the barn and burning up the chaff with unquenchable fire.”

This was the prophet’s description of what the coming Christ will do: sort the good from the evil. And this is what the drama taking place in that village is doing too: the reaction of the Christian people of that town to the evil of Nazism is testing their faith. Franz and his suffering family are the wheat; the villagers who despise them for their anti-Nazi resistance are the chaff.

Within living memory, I believe, educated people would have understood the reference, even if they didn’t hold the faith. To live in a Christian culture is to grasp the stories, the symbols, and the phrases that tell us who we are. The “wheat and the chaff” metaphor is something that almost everybody, from the simple believer to an unbelieving New York critic, would have understood in, say, 1940. But not today, because we are no longer a Christian culture, in the sense we no longer see the Bible, and the deep themes of the Bible, as telling us who we are. “Tell me what your story is, and I’ll tell you who you are.” Well, the inability to understand this movie is a pretty good sign of who we aren’t.

Another scene: when Franz goes before the Nazi tribunal for his trial, he refuses to defend himself. This is what Jesus Christ did at his trial. Franz isn’t falling mute out of a lack of courage. It would not have been un-Christian for him to defend himself, either. I would have loved to have seen a vivid courtroom clash between Franz and his Nazi persecutors. That Malick leaves Franz silent here is a sign to those who know the Passion account that Franz is walking in the way of his Lord. This is — or ought to be — perfectly clear to Christian viewers. And again, it would have been to non-Christian viewers of an earlier time.

Travers (and others) don’t get why this “war film” shows no battles and no Jewish persecution. Because it’s not a war film! It uses the historical circumstances of the Nazi period, and the war the Nazis started, as the backdrop for an exploration of the questions: How should a good man behave in an evil time? How can a man know what is the good? Does suffering have ultimate meaning? Malick could have explored these timeless philosophical themes in any number of dramatic and historical settings — for example, during the American Civil Rights movement. He chose the Nazi period, in part, I think, because it is so close to us, and in part because we all think we know how we would have behaved back then — and we are lying to ourselves.

This is not a movie about war; it’s a movie about religion. Malick starts the movie by positioning Adolf Hitler as a false god, and those who follow him as idolaters. How was it that these simple peasants, Franz and Fani, had what it took to grasp what was happening, and to commit themselves to suffering to bear witness to the truth, when most other villagers either didn’t get it, or were too afraid to say what they were really thinking? I think it’s fair to wish that there had been more exposition, more dialogue in which the couple talks about this, but the truth is, they don’t really know either. They have a good sense of it, but it is not crystal-clear what is to be done. The village priest is not a Nazi, and his advice to Franz to keep his head down to protect his family is all too human. The bishop signals that he knows what is happening is wrong, but he believes that he can better protect his flock by cooperating with the Nazi authorities. We know in historical retrospect that this was the wrong stance to take, but these flesh-and-blood people were not living today; they had to live right then and there. In a sense, Malick’s refusal to put clearly articulated theoretical answers into the mouths of Franz and Fani highlights the power of faith and their formation leading up to this moment of testing.

A Hidden Life helped me to understand better how heroic the anti-communist Christian resisters I met last year in the Soviet bloc nations were — and how they got to be that way. It didn’t come from nowhere. It came from a life of faithful discipleship. When the artist painting the church in the Malick film laments that we make “admirers” of Christ, when what He really asks for is “followers,” this is a powerful indictment of the failure of the Church, and of ourselves (because we too are the Church), to live by habits of discipleship that work the Christian story into our bones. I am sure that Franz and Fani understood more clearly than the film indicates why they did what they did, but it is quite powerful nonetheless that Franz’s refusal to capitulate and burn a pinch of incense to the Nazi Caesar comes from a place deep inside him that he doesn’t put into words, or cannot.

Think about it like this. You know in the Book of Daniel, in the Hebrew Bible, when the three Hebrew youth — Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego — who serve the Babylonian King refuse to obey him and worship the golden idol? And their obstinate refusal causes them to be thrown into a furnace, where God miraculously preserves their lives? Daniel gives us no theological explanation for why and how they refused. We ask ourselves: how did those three men live their daily lives, such that when the time of testing came, they were willing to die as martyrs rather than betray God? That’s what A Hidden Life asks us to consider about Franz. It is no accident that an image of bread being put into the village’s collective oven, as well as coal being shoveled into furnaces to fuel the Nazi death machine, are contrasted in Malick’s film. He is showing us that fire can transform wheat into the bread of life, but fire can also be a means of death. No one in 2020 needs to be reminded of what else the Nazis did with fire and ovens. When you consider that fire is a classic Christian symbol of the Holy Spirit, the visual contrast between Christ and Antichrist is made even more profound in this Malick film.

Do you see what I’m getting at? A Hidden Life presumes a certain level of cultural literacy about Christianity. But Malick is certainly not being deliberately obscure, and taunting the rubes. In this answer to the New York Times critic A.O. Scott, who did not like or understand the movie (and who forthrightly confesses his inability to grasp why Franz did what he did, Alan Jacobs (who has called the movie “a great, great masterpiece”) offers something worth pondering. In his review, Scott said his own biases “give priority to historical and political insight over matters of art and spirit” — as if what Franz did was simply aesthetic or spiritual in a way disconnected from politics and history. Excerpts from Jacobs’s reply:

There are no Jews in A Hidden Life because in the Hitler era there were no Jews in remote Austrian mountain villages. And yet the ultimate demand of Nazism — its demand for unconditional and unquestioning obedience, as manifested in a spoken oath of loyalty to the person of Adolf Hitler — reaches even there. The craving of the totalitarian system for power, its libido dominandi, has no terminus, and its administrative and technocratic resources are such that it can and will find you and order you to bend your knee. So if Scott wants “historical and political insight,” there it is.

But that’s not where the story of A Hidden Life ends, that’s where it begins. What do you do when you are confronted with that absolute demand for absolute obedience? What do you do when the administrative extensions of Hitler’s will send you a letter that calls you to serve — when your Mortall God, as Hobbes named it, requires your obeisance? Maybe, if you’re a Christian, you’ll hear a voice in your head: “They are all acting contrary to the decrees of the emperor, saying that there is another king named Jesus.” And then what?

Behold, I tell you a great mystery: Some people heed that voice rather than the voice of their Mortall God. A. O. Scott doesn’t get it — “Franz Jägerstätter’s defiance of evil is moving and inspiring, and I wish I understood it better” — but then, who does? St. Paul famously speaks of the mystery of iniquity, but the mystery of courage and integrity may be greater still.

Yes. Terrence Malick doesn’t try to explain all this to you. His characters are not walking theses. He shows it to you. If you want to preserve the peace and harmony of life in your beautiful Austrian mountain village, then you can go along with what the Antichrist asks of you. But what if something deep inside you, something you can’t quite articulate to yourself, screams: “No!”? How do you hold onto that, even though your love for your wife and children, and all the people you know, and respect, are telling you its madness to walk the narrow and treacherous road?

I would imagine that the rapturous beauty of your home village, and your life there with your wife and children, would go through your mind a lot, as you contemplated trading that for shackles and a prison cell, and ultimately the executioner’s blade. This is what Malick shows us.

At one point, Franz sits with his arms in chains before a Nazi judge who can’t figure out why he’s doing what he’s doing. Don’t you want to be free? asks the Nazi.

“I am free,” says the prisoner.

Is he? If he were free to lope through the wheat fields back home, and embrace his wife, and do all the things he could do in his former life, he would not be free: he would have purchased that appearance of freedom at the cost of enslaving his soul. Here is the paradox of Christianity: Jesus trampled down death by death, he set the captives free. But just as His kingdom is not of this world, so too is the freedom he promised not the same as earthly freedom. This is the great mystery. And this is why, after Franz is led away, the old Nazi judge sits in the chair where he had been, places his hands on his lap, and contemplates them. The look in his eyes conveys what words do not: that he, the old man, knows that he has made himself captive to evil, and he knows that the freedom of his body comes at the cost of his soul’s liberty.

This is what totalitarianism is! The villagers who know what Hitler really means, and who despise him, but can only say that to Franz in hushed, terrified voices — they show us what it means to live in totalitarianism. Hitler doesn’t demand simply your obedience; he demands your soul. This is the significance of Franz’s refusal to take the loyalty oath to Hitler. He gets it. People keep telling him that nobody will see his sacrifice, that it won’t change anything. Franz persists not because he expects favorable consequences from his sacrifice, but because he is convinced that it’s the right thing to do, and that he will be held responsible before almighty God for his choice.

Franz could have come down off that cross. At every point, he is offered freedom, if only he will sign the loyalty oath. It’s just a piece of paper, says his lawyer. Think of your family. Had the real-life Franz Jägerstätter done that, he might have gone home after the war to a long life with Fani and their children, and one day grandchildren. Who could have blamed him? He suffered greatly in prison, which was a lot more than most Austrian Christians did. His wife would have had a husband, his children a father. The outcome of the war didn’t depend on what this one Austrian peasant did.

But that’s not how Franz and Fani saw it. In the film, a large, clean, beautiful image of the crucified Christ hangs on their wall, as surely it does in every other farmhouse in their village. The crucifix was not something to be admired for the Jägerstätters; it taught them how to live and how to die. Whether they realized it at the time or not, they were absorbing the lesson of the crucifix, so that they could live in imitation of Christ. I thought as I watched Fani last night about Kamila Bendova, the wife of the late anti-communist dissident Vaclav Benda. The communist Czech government put Benda, a faithful Catholic, in prison for his dissident activities. They might have shot him. At some point, they offered to set him free, in exchange for his agreeing to leave Czechoslovakia with his family, and move to the West. Who could have faulted Benda for taking that offer? But Kamila, who was burdened with raising their six kids alone, in a time when the totalitarian state targeted their family, wrote to him and said no, we need to stay here with our people. We have to bear witness to the truth — and our family’s willingness to suffer is how we do that. Be at peace, husband; I’ve got everything at home under control.

The Bendas also have a large crucifix on their living room wall, in Kamila’s Prague apartment, where she and her husband (who died in 1999) raised their children. Here’s a photo I took when I visited them in 2018:

That Christian family saw — they do see — Jesus as not someone to be merely admired, but also to be imitated, to be followed. And they did it. I think of these words from Lutheran pastor Richard Wurmbrand, a survivor of the Romanian gulag: