Rod Dreher's Blog, page 180

January 15, 2020

Judge Rules Against Donna Quixote

In a ruling issued today, a three-judge panel of the US Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals said, “We decline to enlist the federal judiciary in this quixotic undertaking.” What quixotic undertaking is that? Let’s let the gay newspaper the Washington Blade tell what happened from its point of view:

In a move surprising no one familiar with his anti-LGBTQ record, a Trump-appointed judge on the U.S. Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals Wednesday rebuffed a request from a transgender inmate seeking to referred by her preferred pronouns.

U.S. Circuit Judge Kyle Duncan, who before Senate confirmation in 2018 sought to deny transgender student Gavin Grimm access to the school bathroom consistent with his gender identity, concluded in his 11-page opinion recognizing those preferred pronouns would “raise delicate questions about judicial impartiality.”

Duncan’s ruling not only rebuffs the request from the transgender defendant, Katherine Nicole Jett, to be addressed with female pronouns as part of her appeal, but also dead-names her in refusing to agree to her request for a name change, which a trial court had already ruled against.

Jett admittedly isn’t the most sympathetic person, even among prison inmates. In 2012, Jett was sentenced to 180 days in prison, to be followed by 15 years surprised release, after pleading guilty to one count of attempted receipt of child pornography. Her federal sentence, according to the decision, was “influenced by his previous convictions at the state level for possession of child pornography and failure to register as a sex offender.”

Deadnaming, even! Good for Judge Duncan, who wrote for the two-judge majority on the panel. This is the kind of ruling that makes one very, very glad that we have a Republican president naming federal judges. Here is the official text of the ruling in PDF form. There are three bases for Duncan’s judgment.

First, there are no legal authorities requiring that the court use a defendant’s preferred pronoun. Though different courts have adopted different practices in particular instances, there is no rule requiring it. Nor is there a law. “Congress knows precisely how to legislate with respect to gender identity discrimination, because it has done so in specific statutes,” writes Judge Duncan. “But Congress has said nothing to prohibit courts from referring to litigants according to their biological sex, rather than according to their subjective gender identity.”

Second, Duncan’s ruling shrewdly recognizes that a court choosing to compel using a litigants preferred pronoun, versus the one referring to his or her biological status, “could raise delicate questions about judicial

impartiality.” In certain cases hinging on whether a litigant should have certain rights based on asserted gender identity, a court “may have the most benign motives” in honoring that request, but in so doing, “may unintentionally convey its tacit approval of the litigant’s underlying legal position.”

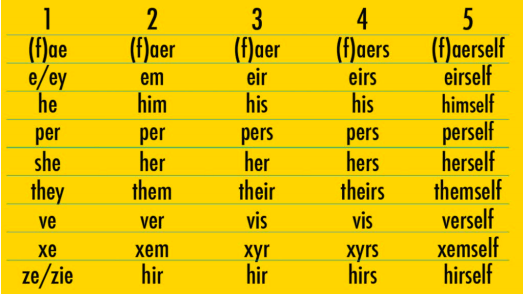

Third, the inmates-cannot-be-allowed-to-run-the-asylum argument. Duncan’s ruling cites this chart from the “Pronoun How-To Guide” from the LGBTQ+ Resource Center at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee:

Duncan continues:

If a court orders one litigant referred to as “her” (instead of “him”), then the court can hardly refuse when the next litigant moves to be referred to as “xemself” (instead of “himself”). Deploying such neologisms could hinder communication among the parties and the court. And presumably the court’s order, if disobeyed, would be enforceable through its contempt power. See Travelhost, Inc. v. Blandford, 68 F.3d 958, 961 (5th Cir. 1995) (“A party commits contempt when he violates a definite and specific order of the court requiring him to perform or refrain from performing a particular act or acts with knowledge of the court’s order.”); see also 18 U.S.C. § 401. When local governments have sought to enforce pronoun usage, they have had to make refined distinctions based on matters such as the types of allowable pronouns and the intent of the “misgendering” offender. See Clark, 132 Harv. L. Rev. at 958–59 (discussing New York City regulation prohibiting “intentional or repeated refusal” to use pronouns including “them/them/theirs or ze/hir” after person has “made clear” his preferred pronouns). Courts would have to do the same. We decline to enlist the federal judiciary in this quixotic undertaking.

Good heavens, a federal court striking a blow for common sense against gender ideology insanity. More, please.

The post Judge Rules Against Donna Quixote appeared first on The American Conservative.

Old World Queen Vs. New World Queen

For you readers who are sick and tired of the attention I pay to the Harry and Meghan drama, well, you are going to have to avert your eyes, because here I go again. On Monday, the day that the Queen held her Sandringham summit, Freddie Sayers has the best explanation I have yet seen for why this matters. It’s not about racism, or sexism, or any of those convenient woke-politics designations. Here’s what it’s really about (and why I find it so fascinating):

The Royals traditionally function as ciphers: representations in human form of entire world views that are otherwise hard to talk about. As Henry VIII represented the break from Rome, and Victoria represented Empire, they put a face on the big ideas of the age, and people line up behind them. In this clash, things are no different.

Today, we are told, in a drawing room at Sandringham, a showdown is taking place between Meghan, the unhappy American princess dialling in from Canada, and the 93-year-old Queen — mediated by their various princes. It would be hard to find two more suitable representatives than these two women of the clashing philosophies that, in different ways, have dominated British and European politics for the past decade. Tradition versus progress, duty versus self-actualisation, community versus commerce, nation versus globalisation.

Sayers points out that the British public is pretty liberal about most things. According to polls, they believe that if Harry and Meghan want out of the Firm, then they should be allowed to go. But they should be made to pay a price. Sayers:

But on another level, there is a growing fear that this same logic, in its relentless ratchet towards ‘progress’, will inadvertently destroy the things we hold most dear. It’s an uneven conflict because where the liberal world view is coherent, defensible and ostensibly virtuous, many of the things it threatens are hard to defend in the same terms. This mismatch makes people defensive and angry, as the Sussexes are now discovering.

In this competition of world views, the monarchy is highly vulnerable. In yesterday’s poll, even millennials are still clearly in favour of keeping the monarchy, and boomers even more resoundingly so. But there can be no logical liberal argument either for raising up an arbitrary family through birth, or for denying their individual rights once they’re there (denying them a political vote is already a breach of their human rights). If the monarchy has to justify itself in this way of thinking, it will eventually fall.

More:

Meghan was initially welcomed with open arms by the British public, and her Hollywood backstory and mixed-race background brought something new to an institution people like to see gradually evolve. But she has recently come to represent precisely the combination of woke politics and global corporate power that a majority of British voters are trying to find ways to resist — instead of modernising a beloved old elite, she now seems to be dragging her husband into to the hated new elite, and it feels dangerous.

Sayers goes on to say that if the monarchy is to be defended, it can’t be on the grounds that the Sussexes are behaving badly. There is no way to rationally justify the monarchy in a world of liberal individualism. It has to be taken on what amounts to faith. Read the final paragraphs of the Sayers piece for his explanation of the great good the monarchy does for Britain simply by existing.

There’s been a lot of attention paid to this Buzzfeed piece comparing and contrasting UK tabloid coverage of Kate Middleton with Meghan Markle. This is prima facie evidence that there is a double standard. But why that double standard? Some say racism, though there’s no proof of that. It could be anti-American snobbery; there’s at least as much evidence of that as of racism.

But there might well be something else. Decades ago, I had a collection of essays by the film director John Waters, published under the title Crackpot. In the book, there was a shrewd piece called “Why I Love The National Enquirer.” It’s the kind of thing you would expect John Waters to write, but as ever with Waters, there’s often a serious point beneath the satire. I can’t find the essay online, but as I recall, Waters argued that tabloids were an unfailing expression of the vox populi. Not the respectable vox populi, but what the masses really think. He talked about how tabloids both make gods and goddesses of celebrities, and then savage them mercilessly, by focusing on their real weaknesses. The point is to bring them down into the muck where The Rest Of Us live.

I defer to British readers on this point, but it strikes me as plausible that the tabloid editors, with their intuitive grasp of what their readers think, gave Kate the benefit of the doubt not necessarily because she was white, or British, but because as a Briton, she intuitively grasped the monarchy’s role, her own place in it, and what was expected of her. Into this very particular and rarefied world walked an American television actress, who has been accustomed to living out her privilege in a different way, and she rebelled against it. Perhaps the British tabloids sensed that Meghan wanted to set her own rules for how she was going to be a Royal, and they decided to take her down a few pegs to teach her what it meant to be a British Royal.

Plus, you can be sure that the British tabloids resented her for changing Harry. From the New York Post‘s Page Six, a year ago:

Larcombe told The Post that this is just another example of how the once-jovial, beloved prince has changed since his marriage to the American actress and how his longterm relationships are suffering as a result.

“All of Harry’s staff have always thought he was fantastic, but the two of them [together] are high maintenance,” said Larcombe of the royal couple, adding that the prince has become “quite grumpy and aloof from his own inner circle of staff. Harry was always very pally with [them], so this is very unlike him.

“What people love about Harry is that he wears his heart on his sleeve,” Larcombe added. “He’s down to earth, a normal guy trapped in the royal world, and he doesn’t take himself very seriously. But now he is.”

The difference, sources say, is Meghan — whose American independence is rubbing some royal insiders the wrong way. They add that it’s been tough for the strong-willed duchess, who is expecting a baby in April, to go from controlling her own personal and professional life to not being allowed to make all her own decisions.

As a result, she is allegedly taking her frustrations out on those around her.

… “As an actress, Meghan expects perfection,” he said. “But when you’re in the royal family, you have to learn that it’s not about you, it’s about what you represent.”

If this is an accurate read on how Meghan clashed with British tradition, then you should not be surprised that the tabloids had it out for her. It’s because she was a duchess, but also wanted to be a prima donna. On this account, she thinks the institution ought to bend itself to fit her, not the other way around. If that’s true, then if I were British, I would resent that too.

Whatever the truth, Freddie Sayers is right: the Queen and Meghan Markle symbolize a clash of worldviews. You might not give a toss about the soap opera that is Windsor family life, but Sayers explains why the outcome of this conflict really is important, not only as a matter of cultural history, but geopolitically too.

UPDATE: Reader Jonah R. nails it:

I usually see it as my duty as a small-d democrat and a small-r republican not to pay attention to the British royal family.

But since this post is here and I read it, I can’t help but notice what Meghan has done in her time as a royal:

– clashed with the 93-year-old woman who rallied her helped rally her nation as a child during the worst war in human history

– devoted her energies to fighting for independence for her filthy-rich husband against his own family

– started a trademarked royal lifestyle brand

I was no fan of the maudlin cult around the very weird Princess Diana, but at least she was out there trying to do good in the world, and at least she got the lay of the land before going rogue.

I don’t bow to royalty, but it sure is unseemly to see Meghan repeating one of the worst trends of modern America: joining a venerable institution solely to ruin it.

The post Old World Queen Vs. New World Queen appeared first on The American Conservative.

Benedict Option For The Humanities

The University of California Santa Barbara wants to hire a professor of woke alchemy:

Can you imagine wasting your money, your mind, and your life studying this garbage? As a Twitter follower of mine said:

Ross Douthat writes an extremely sobering column about the collapse of the academic humanities (this “queer migrations” position sounds like social science, not humanities, but the general theme is applicable). It begins:

This column tries to keep its cool, but last week I briefly surrendered to crisis and existential dread, to the sense that an entire world is dissolving underneath our feet — institutions crumbling, authorities corrupted, faith in the whole experiment evaporating.

What put Douthat in this mood? A collection of essays in the Chronicle of Higher Education, talking about the last gasp for humanities in US colleges. More:

The package’s title is a single word, “Endgame,” and its opening text reads like the crawl for a disaster movie. “The academic study of literature is no longer on the verge of field collapse. It’s in the midst of it.” Jobs are disappearing, subfields are evaporating, enrollment has tanked, and amid the wreckage the custodians of humanism are “befuddled and without purpose.”

More:

A thousand different forces are killing student interest in the humanities and cultural interest in high culture, and both preservation or recovery depend on more than just a belief in truth and beauty, a belief that “the best that has been thought and said” is not an empty phrase. But they depend at least on that belief, at least on the ideas that certain books and arts and forms are superior, transcendent, at least on the belief that students should learn to value these texts and forms before attempting their critical dissection.

I’ve told the story in this space about the time I gave a speech about how reading Dante saved my life, and then took questions from the audience. A young woman, graduate student age, asked me with evident sincerity why we should pay attention to someone like Dante, who represents a sexist, racist European culture. I thought she was teasing me at first, but it was obvious that she meant it. I don’t remember how I responded. All I recall is shock that the question was posed, especially after I had just explained in great detail how amazed I was to discover that this late medieval Tuscan poem held within it insights that saved my life. A professor of literature came to me after the Q&A and told me that the young woman’s question reflects how colleges teach the Greats today.

If that is the case, then they are destroying the humanities, and they deserve to commit suicide. But we have to rescue this art and literature from the educated barbarians who have custody of them, but who have proved to be such rotten caretakers of the tradition. Here is an excerpt from an essay by Australian academic Simon During, which Douthat says is the best one in that Chronicle package. In the piece, he frames the collapse of the humanities as a “second secularization” in the West. In the first one, religion was marginalized. In this new secularization, high culture is marginalized. During writes:

What about resistance to cultural secularization? It will help to turn first to the three major genres of resistance to religious secularization. The first is absolutist: Secularization is wrong because God’s revelations and miracles are real. The second is functionalist: Religion provides the framework in

which our society, culture, and morality are most securely grounded, and therefore attempts to marginalize it should be thwarted. The third is existential: Human beings are lost in a cosmos they cannot account for and therefore driven toward the transcendentalisms that articulate the wonder, awe, and anxiety they encounter in approaching Being. Religion, the thinking goes, best expresses those affective, existential needs in part because it binds us to earlier generations.

The secularization analogy is illuminating here. Some of those who wish to push back on cultural

secularization do so on absolutist grounds, making the claim, for instance, that the cultural canon that

holds Western civilization’s glories is where real beauty and truth exist. Some make a functionalist

argument: The humanities provide irreplaceable grounds for a good democratic society. They can, for instance, shape empathetic and tolerant moral sensibilities more powerfully than any alternative.

Last, some who resist cultural secularization do so on existential grounds. They claim that high cultural traditions and artifacts, along with the practices of interpretation and critique developed in

response to them, provide us with the least reductive, most subtle, most profound, impersonal, and

thoughtful experiences and lessons available to us, experiences that preserve and sanction the heritage.

None of these defenses seems to me particularly strong. Most of us agree that our canon does not bear any absolute truth and beauty, but rather it belongs to (a fraction of) one particular culture or cluster of cultures. The functionalist argument is weak because, as we have seen, the humanities preach many messages besides empathy and tolerance and the democratic, cosmopolitan virtues.

And they don’t seem to make people more empathetic and tolerant anyway. The existential argument is politically impossible because of its implicit elitism: It divides and hierarchizes the world into those shaped by the humanities and those not. Against the grain of contemporary ideology, it also downgrades experiences that happen in, say, nature or in sport rather than in the proximity of high-cultural artifacts. But it is also weak because it is irrelevant. Some, especially among the upper-middle class, will no doubt continue to experience canonical cultural works as incomparably enriching (I do so myself), but that will not hold cultural secularization back. Under secularization, admiration for and commitment to the canon and the old disciplines remains an option (especially for elites), just as religion remains an option (especially for non-elites).

This is an important insight. If both religion and the traditional humanities are seen as tangential to human existence, obviously we have to ask why. The late sociologist and cultural critic Philip Rieff is extremely helpful here. Carl Trueman wrote a good, clear summary of Rieff’s theories of culture. Excerpt:

In Sacred Order/Social Order, Rieff offers a historical scheme for categorizing cultures in light of these basic insights. Rieff calls these First, Second, and Third World cultures. First Worlds are characterized by a variety of myths that ground and justify their cultures through something that transcends the immediate present. These might be the tales of the gods and heroes in the Iliad or the Norse sagas, the philosophy of Plato, or the mythic stories of origin found in Native American societies. Whatever their specific content, what they share in common is that they make the present culture accountable to something greater than itself. Rieff says that a belief in fate is perhaps the key here.

Second Worlds are characterized not by a belief in fate but by faith. The great examples would be Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, where cultural codes are rooted in the belief in a specific divine and sovereign being who stands over and above creation, and to whom all creatures are ultimately accountable. First and Second Worlds are similar in that both set their social order upon a deeper, even sacred, order. It is the Third World that represents a decisive rupture on this point.

Third Worlds are characterized by their repudiation of any sacred order. There is nothing in a Third World beyond this world by which culture can be justified. The implications of this are, according to Rieff, comprehensive and catastrophic. First, because of their rejection of a sacred order, Third World cultures face an unprecedented challenge: that of justifying themselves on the basis of themselves. No culture in history, Rieff notes, has ever done this successfully. It is a fool’s errand that ends in cultural collapse:

No culture in history has sustained itself merely as a culture, however attractive and authoritative. Cultures are dependent on their predicative sacred orders and break into mere residues whenever their predicates are broken. That is the main reason why our late second cultures and early thirds are increasingly unstable.

To return to our initial question—why is so much traumatic cultural change occurring with such rapidity and intensity today—we can helpfully apply this scheme to our current context. The proliferation of identities and the consequent chaotic militancy of identity politics is inextricably related to the collapse of the sacred, to the demolition of any transcendent metaphysical basis on which a coherent social order might be founded. Even the question of “What is human nature?” becomes something impossible to answer with any degree of certainty or consensus.

Read it all. There is no way to arrest this collapse, this suicide of the West, whose intellectuals have ceased not only to believe in its own traditional sacred order (which includes the canonical power of the traditional Western arts and humanities), but in the idea of sacred order at all. “Decolonizing” the humanities is an ideological label for destruction. If you do not believe that your culture is in some sense rooted in transcendence (“sacred order”), whether explicitly religious or in grounded in some other metaphysical conception, it will not stand.

As Rieff points out, it is not enough to say that the humanities are “good for you.” That is therapy. It doesn’t work, or it doesn’t work as long as its value is seen as primarily therapeutic. My book How Dante Can Save Your Life is, admittedly, in a therapeutic vein. No apology for that. But the reason that reading Dante helped me therapeutically is because I believe that the beauty of the poetry illuminated for me virtues and realities that actually exist, but which had been hidden from me. See what I mean? Dante showed me the world as it really is, and me as I really am. It revealed truths that are truly true (i.e., this is real), not just instrumentally true (i.e., this is helpful). It could not have been therapeutic if it were not also truly true.

Obviously I’m not claiming that the Inferno is a real place. I’m saying that the world created by the imagination of Dante Alighieri — a world that could not have been created by anyone other than a Western poet — revealed eternal truths about the human condition, and of the nature of reality. I do not claim that Westerners have a monopoly on this vision. But I do claim that Westerners — and Christians, including Christians of the cultural East — have a particular perspective that is valuable in and of itself, and should be privileged, because it is a more reliable way of perceiving ultimate truth than any competing framework. This is not, of course, to say that other cultures do not have valuable insights from which we can and should learn. It is to make a claim for the superior intellectual and cultural value of the Western inheritance. The Hebrews were privileged to be granted particular access to God, and so, in turn, were Christians, who received that heritage and combined it with the philosophical genius of the Greeks and created, over the centuries, what we now call Western civilization. This is a gift to be celebrated, with gratitude. It is a living tradition that exists, or should exist, in constant dialogue with other civilizations and their own heritages. The Western tradition today, for example, encompasses Duke Ellington as much as it encompasses Gustav Mahler. White Westerners enslaved the Africans, but when they got here, and took Western musical instruments and traditions into their own lives, they created art of incredible power and beauty. That’s ours too, because African-Americans are Western people too, as are Asians and all others who are part of this civilization.

Rieff, ethnically Jewish, was not a religious believer at all. He was a passionate believer in high culture, though. I don’t know enough about him to say whether he was confident that the high culture of the West could exist severed from its roots in Abrahamic religion. I think there must be an answer to that question, but I have to invite students of Rieff to give it.

Me, I don’t think it can. What I think is undeniably true is that it cannot survive absent a shared belief in transcendence. This is why I bang on so much about nominalism and voluntarism being crucial turning points for Western civilization, insofar as they ultimately led us to believe that there is no such thing as meaning existing outside of the meaning we choose to impart to phenomena. In other words, that meaning is entirely a creation of humans, and imposed on a meaningless universe.

I have heard it said for years that in the end, one will only be able to receive a traditional humanities education in Christian colleges and universities, because only those institutions can perceive the humanities as grounded in transcendence. But more recently, I have been told by Christian academics themselves that their institutions are in collapse on this front too. At the risk of oversimplification, many of these schools have also discarded belief in the traditional humanities as rooted somehow in transcendence, and connected to the Christian mission. They too are submitting to the same disease that has secularized high culture.

Do I believe that you have to believe in Bach, Dante, and Shakespeare to be a good Christian? Certainly not. But I believe that you have to have faith that there is a sacred order, to use Rieff’s term, and that the arts and humanities of the Western tradition offer particular expression of and access to that sacred order. The scholar Stephen Gardner, I believe, has written that Rieff was a secular Jew, but a philosophical Catholic, in that he believed in sacred order and hierarchy. Whatever our own religious or philosophical commitments, if we aren’t philosophical Catholics, in that sense, then we can’t sustain any kind of humanism, be it secular or Christian. If art and literature is nothing more than an expression of power based on ethnicity, sex, religion, and what have you, then the study of the humanities becomes nothing more than a struggle for power. And this, as we see, is what has happened. As Douthat wisely discerns, the entire structure must

depend at least on that belief, at least on the ideas that certain books and arts and forms are superior, transcendent, at least on the belief that students should learn to value these texts and forms before attempting their critical dissection.

What we need is a Benedict Option for the traditional humanities. If we understand their collapse in postmodernity as a version of what has happened to Western Christianity in modernity, then we had better act to create the equivalent of monasteries and monastic communities within which this knowledge, and these practices, can survive this age of darkness and barbarism. These places will esteem the Western tradition of art and literature as having value in and of themselves, not solely in relation to what they can do for us.

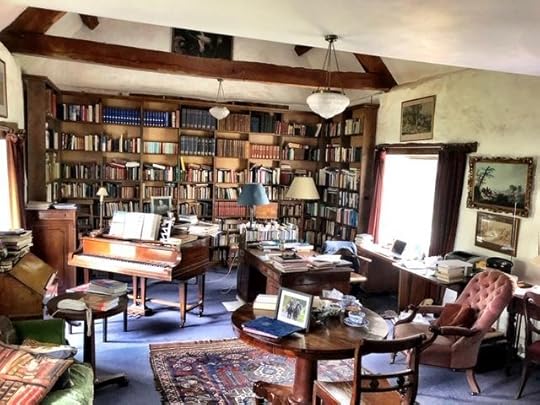

Besides, as Sir Roger Scruton argued in this essay on the value of independent schools, we can never know for sure how the tradition we receive and transmit will serve us. Excerpt:

Independent schools, with an ethos of their own, have evolved in response to those desires. They embody knowledge of the learning process that cannot be easily taught from scratch. Over the past two centuries, they have proved themselves able to produce an educated elite that saw us through bad times, during which we were challenged to compete in all fields – intellectual, military, ethical and economic. And that elite has proved decisive for our national survival.

Finally, and most importantly, there is the interest of knowledge, which is the one most important thing at risk in all our educational experiments. Knowledge is an intrinsic value that cannot be weighed in terms of cost and benefit. It is the value on which civilisations are built and to which, as Aristotle said, our faculties naturally aspire. [Emphasis mine — RD]

Education involves the transmission of knowledge, and knowledge is often lost in the attempt. Educationalists influenced by Rousseau and Dewey have insisted in recent times on the rights of the child, emphasising “child-centred” teaching – that is, teaching that engages with the interests and abilities of those who as yet have no education. But there is precious little evidence that such a method of teaching succeeds in the main goal, which is not about the interests of the child at all, but about the transmission of knowledge. Knowledge not transmitted is knowledge lost. And regardless of whether the knowledge transmitted is – or thought to be – useful, it creates a duty that lies on all of us to see that it is preserved and, if possible, amplified.

In any case, we cannot know in advance which bits of knowledge will be the most useful in the ongoing march of history. Latin, Greek and ancient history, condemned for their futility by all the progressives of the Victorian period, turned out to be exactly what was needed in the task of governing an empire acquired in a “fit of absence of mind”. How else do you prepare yourself to govern countries with competing gods, strange languages and a tribal conception of obligations than by studying the only civilisations that have been able to write the matter down?

Conversely, the crazy mathematicians of the time, such as Boole, seemed to their classicist contemporaries to be lost in futile problems about nothing: what hangs on knowing the contours of the empty set or the sequence of transfinite cardinals? In fact, this wonderful store of knowledge turned out to be exactly what was needed by the science of computation.

As I have said many times here, the classical Christian school movement is a kind of Benedict Option. Classical education presumes that there is a right order to the human mind and heart, and that we can learn what that order is, and form ourselves to it, by studying the wisdom of Western civilization. In this essay on the meaning and purpose of classical education, Martin Cothran says:

Today’s education is almost a direct inversion of the old classical emphasis on how to think and what to do; the political and vocational emphases of today’s education teach students, not how to think and what to do, but what to think and how to do. Its political goal is to use schools to change culture, and its practical goal is to change students to fit the culture.

The goal of classical education was very different. It was not interested in changing culture or fitting children to a culture. Its goal was to pass on a culture—and one culture in particular: the culture of the Christian West.

In classical education, students read the classics. They focus their attention on what the Victorian scholar Matthew Arnold called “the best which has been thought and said.” In Western civilization, our focus should be on what I call the “three cultures”: Athens, Rome, and Jerusalem—the Greeks, the Romans, and the Hebrews.

But why study these cultures? We should study the Greeks because the Greeks were the archetype of philosophical and literary man. They were the original philosophers and poets. Every great idea—and every lousy one—came from some Greek somewhere. All you’ve got to do is trace it back.

Why study the Romans? We study the Romans because the Romans were the archetype of practical, political man. They were the road builders and the republicans of ancient times. These are the people who ran the world for a thousand years. They ran the most enduring government history has ever seen. In fact, the Founding Fathers used the old Roman republic as their model in constructing the American government.

Why study the Hebrews? We study the Hebrews because they are the archetype of spiritual man. From them we learn how God deals with individuals and with nations.

In studying these three cultures, classical education does not ignore American history and culture. In fact, in order to fully understand American civilization, a knowledge of these three cultures is crucial since, as political philosopher Russell Kirk has pointed out, all three of them were essential in the forming of our thought, our political institutions, and our moral principles. We study these three cultures and the great works they produced because they constitute our heritage as Western people.

Lynne Cheney, former head of the National Endowment of the Humanities under Ronald Reagan, once said that if you graduate from school not knowing what Western civilization is, then you are not really educated. She was right.

If you don’t believe that there is a such thing as human nature, and that there is a such thing as an order that exists outside of ourselves, that we can know, in part — well, there’s no point to any of this. But if that’s what you believe, then you should be prepared to say farewell to Western civilization.

Those who are not prepared to see the humanities and the liberal arts fade into nothingness had better act, and act now. These colleges and universities, like many of our churches and seminaries, may be too far gone to save. It is time to create the communities and institutions that can keep the tradition alive, and to strengthen those that are now standing as a counterculture (for example, The Circe Institute).

UPDATE: A reader writes:

Rod, I’m a Classics student at a strong public university. I went into Classics purely because of my love of these old books, in particularly Classical Philosophy, which saved my life similarly to how Dante saved yours. Unfortunately, after thriving in my program and having the opportunities to meet people and get a good look at the ‘future of the discipline’, I’ve seen enough to realize that there is no hope for these institutions and by extension the future of traditional Western Civilization, both within Classics and without. The students are thoroughly rotten, drones made of pure zealotry, but the greater fault lies in the professors who even if they believe there is something of worth in our heritage are too meek to defend it. I understand that they are themselves products of historical trends.

It has been very difficult to digest this reality. I could probably have gotten into whichever graduate school I liked but I’ve realized that this is fruitless. Instead I am planning to try to begin a polis of sorts somewhere in the country where to begin with a few likeminded friends and myself would dedicate ourselves to the study of these old works and tend to the fire of the good, true and beautiful in a time of great material prosperity and ethical darkness.

A different reader writes:

Nietzsche himself saw this coming. In Human, All Too Human: A Book for Free Spirits (1878) he acknowledged the link between great works of art in the Christian West and the Christian belief that sustained them:

“With profound sorrow one admits to oneself that, in their highest flights, the artists of all ages have raised to heavenly transfiguration precisely those conceptions which we now recognize as false [and here he is referring to core beliefs of Christianity]. . . . If belief in such truth declines in general, then that species of art can never flourish again which — like the Divine Comedy, the paintings of Raphael, the frescoes of Michelangelo, the Gothic cathedrals — presupposes not only a cosmic but a metaphysical significance in the objects of art. A moving tale will one day be told how there once existed such an art, such an artist’s faith.”

The post Benedict Option For The Humanities appeared first on The American Conservative.

The Professoriat Queers The Mideast

With the Middle East roiled with wars of religious and ethnic hatred, and once again serving as a proxy battlefield for the interests of Great Powers, as well as generating, through refugee flows, geopolitical changes that place the future of Europe in question, naturally American scholars will answer the call to bring their training and expertise to bear on understanding this dynamic, perilous situation. This morning, a call for papers has been sounded from the University of Chicago:

35th Annual Middle East History and Theory Conference

Theorizing Gender and Sexuality in the Historic and Contemporary Middle East

The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL

May 1-3, 2020

Ah. Tell us more:

We also encourage submissions related to the theme of this year’s conference: Theorizing Gender and Sexuality in the Historic and Contemporary Middle East. The keynote speaker of this year’s conference will be Professor Paul Amar (University of California, Santa Barbara), author of The Security Archipelago: Human-Security States, Sexuality Politics, and the End of Neoliberalism.

For proposals related to the conference theme, questions of interest include the following:

How can theorizing about historic formations and articulations of gender and sexuality in the Middle East inform present day theory and praxis?

Can history serve as a reservoir of tools for contemporary revolutionary politics whose aims include gender and sexual emancipation?

How do we theorize gender and sexuality in the Middle East in a context of novel forms of global governance and security infrastructures?

What alternative geographies, vocabularies, and conceptual frameworks emerge in attending to particular historical struggles/movements that may not have had a lasting impact on contemporary politics or visions of state and society? What does reconstructing or recovering these struggles allow us to see?

What understandings of postcolonial state-formation emerge from moving beyond scholarly claims of “epistemic violence” in relation to matters of gender and sexuality in the Middle East?

How do feminist struggles within the Middle East inform, challenge, or compliment understandings of Western, rights-oriented political movements?

In what ways are categories of gender and sexuality deployed to police and regulate the boundaries of the nation? What new collective political identities emerge through the articulation of rights-claims on the part of gendered and sexual minorities? How are old collectivities activated and entrenched in the face of these rights-claims?

Where would we be without scholars to help us pay attention to what really matters? Why, the whole world is a humanities faculty lounge! How will we ever bring Drag Queen Story Hour to Raqqa if we don’t do the hard work of theorizing now? Surely the people of the Nineveh Plain shouldn’t have to go one more day without knowing how to use gender-appropriate pronouns in Arabic.

UPDATE: Reader Kgasmart:

Can history serve as a reservoir of tools for contemporary revolutionary politics whose aims include gender and sexual emancipation

Gender emancipation. Think about that. For the genderless or the genderqueer or gender-whatatever to be fully “emancipated,” the current binary thinking about gender must be abolished, perhaps punished; you, who celebrated the birth of a baby boy or girl, you are wrong and oppressing the child, and oppressing all who don’t fit into the binary.

It amazes me that the vast majority are now required to throw out the concept of “normal” on behalf of the vanishing few who don’t fit and abhor the mold.

Which is why, ultimately, Muslims and conservatives must make common cause. How interested, do you think, is the average Muslim in the Middle East in “queer” interpretations of his history? How many are interested in “gender and sexual emancipation?”

But it doesn’t matter what those conservative Muslims want, any more than it matters what traditionalists here want; what we have, in other words, is gender and sexual imperialism, both at home and abroad.

The post The Professoriat Queers The Mideast appeared first on The American Conservative.

January 14, 2020

Coach O. Vs. The Acela Gradgrind

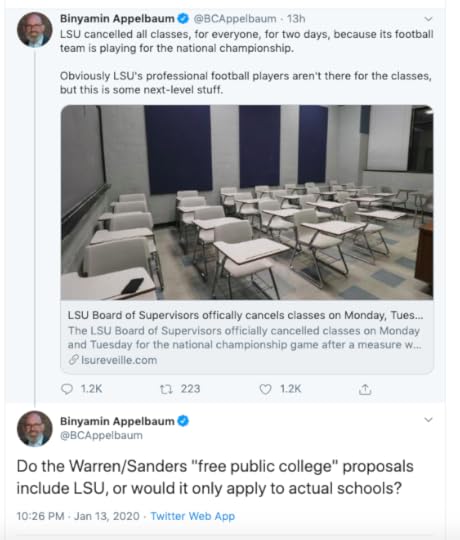

Couldn’t sleep last night, I was so wired up. Finally dozed off, woke up just before noon. I am afraid I must address, as calmly as I can manage, a controversy that has arisen in the Twittersphere. It seems that an Ivy League graduate who writes editorials for The New York Times did not like the fact that LSU cancelled classes on game day and the day after. He wrote:

“Actual schools.” Well, let’s see.

You’d think that the media elites would by now have learned the cost to their own credibility of not understanding this country. But they keep being surprised. Nobody expects a New York Times editorial writer to agree with the decision to cancel college classes because of a football game. But one would like to think that a man of the world such as himself would have enough sense to think about why this decision might have been made, and what it says about cultural difference. I suspect if the LSU Board of Supervisors had cancelled classes for Transgender Day Of Remembrance, the New York Times editorial board would have wet its collective pants with delight.

If you plan to vote for Donald Trump in November, do me a favor, and think of Binyamin Appelbaum and the LSU Tigers when you do.

What Appelbaum does not know is that cancelling classes was a prudent decision, because none of the students would have shown up anyway. Governor John Bel Edwards cancelled his inaugural ball because he knew that everybody would be at the game. He’s close to Coach O; he wanted to be at the game too. This made perfect sense to everybody here. Who wants to go to an inaugural ball when the Tigers are playing for the national championship? Nobody! If Appelbaum had the slightest bit of cultural awareness and sensitivity, he would recognize that not everywhere in this big and diverse country has the same values as the elites of the Boston-NYC-DC corridor. That’s fine; America needs people who graduate from Ivy League schools and go on to write economics editorials for The New York Times. But she also needs her Ed Orgerons, the hard-fighting Cajun from South Lafourche. She also needs her Joe Burrows, a white boy from struggling southeastern Ohio. She also needs her sons like Clyde Edwards-Helaire, a short, tough-as-nails black kid from Baton Rouge who fought his way to become one of the best tailbacks in the nation.

Maybe America needs men like that more than she needs Ivy League editorial writers for The New York Times. Who knows? I couldn’t possibly say.

We are a different people here in Louisiana. When I first moved to New York in 1998, my sister back home couldn’t believe that we New Yorkers didn’t have Monday and Tuesday off for Mardi Gras. I found that endearing. Fat Tuesday is such a holiday in Louisiana that everybody takes off — classes are cancelled, some businesses shut down — so everybody can go to the parades. I love that. It tells you something, though, that my sister, a school teacher, simply could not imagine that the whole country wasn’t celebrating Mardi Gras. This is less about Mardi Gras and more about a Louisiana orientation towards life.

I used to be something like Binyamin Appelbaum. I’m not much of a sports fan, but I am an LSU Tigers football fan, because that is our tribal religion here on the bayou. I’m not kidding: I’m sitting here writing this with tears in my eyes at the very though of Ed Orgeron. I love him so much. Here is a rough guy from down the bayou, who let his passions get away from him early in his life, and nearly destroyed his career. But the people of south Lafourche who loved him helped him get back on his feet. He kept coming hard, trying to rebuild his career. He failed. He failed some more. But he kept coming, and kept coming. When he was named head coach of the Tigers three years ago, a lot of people down here thought LSU was settling for second-best. Ed Orgeron didn’t stop. And now, he is on top of the world, and he has brought us all along with him. He has earned it. Goddamn it, why wouldn’t you be proud?!

Well, you wouldn’t if you were an Ivy League graduate who writes editorials about economics for The New York Times, because you wouldn’t know this world, and you would hate it because it is not logical, according to what you value. A lot of people here love LSU Tigers football because it’s what we have. Some folks, it’s almost all they have to bring joy to difficult lives. Maybe economics nerd Binyamin Appelbaum gets little endorphin bumps of pleasure when the Fed lowers interest rates, but that doesn’t do much for the folks in south Lafourche, or anywhere else in Louisiana. And you know, that’s fine with me. East Coast educated elite culture, in which I moved for part of my life, has some good things to recommend it. I’m serious. Vive la différence.

Anyway, as I said, I’m not all that different from Binyamin Appelbaum. Even though I was born and raised here, and graduated from LSU in 1989, I used to have a fair degree of Appelbaum smugness in me. I explained this, and my change of heart, in a 2013 piece I wrote for the Baton Rouge Business Report, about my decision to return to south Louisiana after my sister Ruthie’s untimely 2011 death from cancer. Excerpts:

As the years went on, I moved up and down the Eastern seaboard, onward and upward with my career. All the while I was corresponding frequently with an email circle of friends. One, a Californian, once said to me, “Did you ever notice that your best writing is about Louisiana? That’s when you really write with flair and passion.”

No, I had not noticed, but I conceded that she was right. Still, I told her, I can never forget the (perhaps apocryphal) words a New Orleans journalist told his newsroom at his farewell party before taking off for a job up North: It was more important to live in a city that valued libraries more than parades. That’s the reality of Louisiana life, I told my friend. Romanticism and sentimentality obscure, but do not nullify, hard truths about the barriers life in Louisiana raises to professional advancement.

Which is what mattered to me more than anything. And why not? There’s nothing wrong at all with wanting to advance in one’s field and better provide for the needs, comforts and prospects of one’s own children. As my family grew, my wife and I moved from New York City to Dallas, and then back east to Philadelphia; my career arc—and my salary—kept rising.

I was doing very well in Appelbaum World, the meritocracy. Then my sister Ruthie, out of the blue, was hit by terminal cancer. Lung cancer. She never, ever smoked. But it killed her, at age 42. More:

In my emotional geography, Ruthie was a landmark, a mountain, a river, a fixed point around which I could orient myself. There was no horizon so far that I could not see Ruthie in the distance and know where I was and how to find my way home to Louisiana, no matter where in the world I lived.

Now she was gone, and before long, my mother and father will be gone, too. What would my children know of Louisiana then? Does that matter? Should it matter?

It mattered. Julie and I decided that we wanted to be part of Louisiana life—tailgating at Tiger Stadium, Christmas Eve gumbo at our cousins’ place in Starhill, po-boys at George’s under the Perkins Road overpass, Mardi Gras parades, yes ma’am and yes sir, and all the little things that give life its texture and meaning more than career prestige and a paycheck.

True, by moving to Louisiana our children would have fewer “opportunities,” in the conventional sense. But what were the opportunity costs of staying away? I had believed the American gospel of individual self-fulfillment and accepted uncritically the idea that I should be prepared to move anywhere in the world, chasing my own happiness.

But here’s the thing. When you’re young, nobody tells you about limits. If you live long enough, you see suffering. It comes close to you. It shatters the illusion, so dear to us modern Americans, of self-sufficiency, of autonomy, of control. Look, a wife and mother and schoolteacher, in good health and in the prime of her life, dying from cancer. It doesn’t just happen to other people. It happens to your family. What do you do then?

The insurance company, if you’re lucky enough to have insurance, pays your doctors and pharmacists, but it will not cook for you when you are too sick to cook for yourself and your kids. Nor will it clean your house, pick your kids up from school, or take them shopping when you are too weak to get out of bed. A bureaucrat from the state or the insurance company won’t come sit with you and pray with you and tell you she loves you. It won’t be the government or your insurer who allows you to die in peace—if it comes to that—by assuring you that your spouse and children will not be left behind to face the world alone.

Only your family and your community can do that.

What our culture also doesn’t tell young people is that a way of life that depends on moving from place to place, extracting whatever value you can before moving on again, leaves you spiritually impoverished. True, it is not given to every man and woman to remain in the place where they were born, and an absolute devotion to family and place can be destructive. I do not regret having left Louisiana as a young man. I needed to do that; I had important work to do elsewhere.

But the world looks different from the perspective of middle age. In her last 19 months of life, Ruthie showed me that I now had important work to do back home. Hers was a work of stewardship—of taking care of the land, the family, and the people in the community. By loving them all faithfully and tending them with steadfast care, Ruthie accomplished something countercultural, even revolutionary in our restless age.

You can’t convince somebody by logical arguments why they should love someone or something. You can only show them, and hope the seed of affection falls in the heart’s fertile soil. Through Ruthie’s actions, and through the actions of everyone else in the town who held our family close, and held us up when we couldn’t stand on our own two feet, I was able to see the power of Ruthie’s love, given and returned. And I was able to see my own life in light of this love, and, finally, to feel for the first time in nearly 30 years, a profound affection for this place I had abandoned so long ago.

We moved back to Louisiana and have regretted it not one bit.

It’s not that Louisiana has changed, or changed all that much. It hasn’t. Parades still matter more than libraries here, and college football coaches’ salaries are more important than college professors’ paychecks. The political and economic problems are still with us. So, bless his heart, is Edwin.

Louisiana may not have changed, but I have. Parades—I speak metaphorically—are a lot more important than I used to think. That is, the small things about the life we were all given as south Louisiana natives can’t easily be given a dollar value, or co-opted into an instrumentalist case for rising in the meritocracy. Having the chance to drive over to Breaux Bridge to the zydeco breakfast at Café des Amis, or to have Sunday dinner with the family every weekend, will not get your kids into Harvard, but it just might give them a better chance at having a life filled with grace and joy. Same goes for their parents.

When we told our Philly friends that we were leaving the big city for a tiny south Louisiana river town, we expected that they would be both shocked and amused. That’s not what happened. A startling number of them responded by saying, one way or another, how much they envied us. They wished they had a place like St. Francisville to go back to. Their parents made the decision to leave, and they themselves had been raised in rootless suburbia. This, it turns out, is one reason why they loved listening to my Louisiana stories: because I come from a real place, with particular traditions and a distinct culture.

Truth to tell, I was lucky that I had a good family back home, a beautiful town, and a job that I could do online. Not every Louisiana expat has these things, and that lack may keep them in exile, against their wishes. Nevertheless, many of us may come to realize that the limits we must accept by moving back to Louisiana make possible a richness of experience that we cannot have anywhere else. And it opens opportunities for us to take the good things we learned in exile and put them to work making our state a place that will be easier for our kids, whatever their calling, to choose as their home.

The cultural case for moving home to Louisiana, then, is fundamentally a countercultural one. The small life expats leave behind in search of grandeur in the world beyond Louisiana—a life whose limits are set only by our own desires and capabilities—may contain a profundity, even a greatness, that is hard to see when you judge it by contemporary American standards.

But how much sense do those standards make when judging a life? A Louisiana native who works in Washington politics said to me that folks back home know something about the good life that other people don’t.

“It’s OK to be average there,” he said. “To go to work each day, come home, have a beer, and love your family and friends. One thing that really sucks about D.C. is that everyone here very seriously carries the burden of having to Change the World.”

To be freed from the felt burden of having to Change the World, of having to get ahead, of having to think of your life in terms of achieve, achieve, achieve—it’s an unusual thing. You can be only OK in Louisiana, or maybe even a basket case, and they’ll love you anyway, as long as you can laugh at yourself and at life, and know how to sit on the front porch, so to speak, and pass a good time.

And to love the LSU Tigers. This is what the Appelbaumist meritocrats will never, ever understand about life. I know this because I used to be one of them, and if I hadn’t had roots down here on the bayou, I might have gone through my entire life never understanding it.

I wrote a book about all this in 2013, titled The Little Way Of Ruthie Leming, after my sister. You who have been reading me for a while know that things didn’t go as well as I had hoped they would with my family when we came back here. It might have done, if we were all better people. But the life lessons that brought me back are still true. I want to share with you some excerpts from the book, because they answer Appelbaum more eloquently than anything I might write today. Starhill is the rural community outside of St. Francisville, where I grew up. You will see here that I adapted some of that Baton Rouge Business Report essay from this manuscript:

All that day, I thought about the long and winding road that had at long last brought me home. It began when Ruthie gave birth to Hannah, but I was not yet ready to receive my inheritance, nor were they ready to receive me. The turn sharpened on the road back when I became a father for the first time, and lay in night at bed with my baby boy, listening to the traffic on the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, wondering what this child will ever know of Starhill. And then came Ruthie’s cancer diagnosis.

I began at that time to think about what life would be like without her in Starhill, and a strange alchemy began to work on me. I started to pine for LSU football, not because I care about sports, but because it’s what our tribe does. I wanted my children to grow up knowing what its like to experience the electricity crackle up your spine and down your arms when you hear the Golden Band from Tigerland play the first four notes of the LSU fight song. I wanted them to hear what Paw’s gravelly Southern drawl sounds like in their ears. What it means to feel the spring breeze passing over your cheek carrying the aroma of sweet olive blossoms. How the cool water of Thompson Creek feels on your ankles on a July day. What a crawfish boiled in Zatarain’s tastes like, what a Mardi Gras parade is, and, above all, what it means to be able to spend time with their family without having to get on an airplane.

Losing Ruthie compelled me to think in a new way about my responsibilities to Mam and Paw, to Mike and my nieces, and to my own kids. In my emotional geography, Ruthie was a landmark, a mountain, a river, a fixed point around which I could orient myself. There was no horizon so far that I could not see Ruthie in the distance, and know where I was, and how to find my way home. Now she was gone.

Ruthie never understood why any brother of hers would walk away from what she considered the greatest place on earth. That was a failure of empathy, and a failure of imagination. But here was my failure: I rarely considered with any degree of seriousness what pursuing my own dreams, and my own sense of personal autonomy, would cost my family and myself. I believed the American gospel of individual self-fulfillment, and accepted uncritically the idea that I should be prepared to move anywhere in the world chasing my own happiness. I honestly believe that God places a particular call on each and every life, and we must be ready and willing to follow Him, no matter what. The thing I had never seriously considered until Ruthie’s passing is that my place, in the end, and the fulfillment of the plan God set for my life before I was born might be found right where I began.

Sitting on my front porch on Fidelity Street one warm winter’s day, I asked Tim Lindsey, Ruthie’s physician, what the biggest lesson of her life was.

“That the American dream is a lie,” Tim said. “The pursuit of happiness doesn’t create happiness. You can’t work hard enough to defeat cancer. You can’t make enough money to save your own life. When you understand that life is really about understanding what our true condition is – how much we need other people, and need a Savior — then you’ll be wise.”

When you’re young, nobody tells you about limits. If you live long enough, you see suffering. It comes close to you. It shatters the illusion, so dear to us modern Americans, of self-sufficiency, of autonomy, of control. Look, a 42-year-old woman, a wife and mother and schoolteacher in good health and in the prime of her life, dying from cancer. It doesn’t just happen to other people. It happens to your family. What do you do then?

The insurance company, if you’re lucky enough to have insurance, pays your doctors and pharmacists, but it will not cook for you when you are too sick to cook for yourself and your kids. Nor will it clean your house, pick your kids up from school, or take them shopping when you are too weak to get out of bed. A bureaucrat from the state or the insurance company won’t come sit with you, and pray with you, and tell you she loves you. It won’t be the government or your insurer who allows you to die in peace, if it comes to that, because it can assure you that your spouse and children will not be left behind to face the world alone.

Only your family and your community can do that.

What our culture also doesn’t tell young people is that a way of life that depends on moving from place to place, extracting whatever value you can before moving on again, leaves you spiritually impoverished. It is not given to every man and woman to remain in the place where they were born, and as Paw’s back-porch confession revealed, an absolute devotion to family and place can be destructive. Still, so many friends of mine have no family home, in the Starhill sense, to return to because their parents chose to move for career reasons. In some cases, their parents, like they themselves, had no choice: our economy is no respecter of communal stability. We need more balance.

Yes, I resented how little understanding or respect Ruthie had for my work. I did not think that way about hers. But I didn’t understand until she became ill and died how important her kind of work was. Hers was a work of stewardship – of taking care of the land, the family, and the people in the community. She didn’t set out to be a good steward, but the place and its people claimed her affection from the day she was born. By loving them all faithfully, and tending them with steadfast care, Ruthie accomplished something countercultural, even revolutionary in our restless age. Nowadays it’s easy to leave home; it’s harder to stay. But it may be more necessary to stay, if we are going to sustain lives worth living, especially in a world that pushes hard against our limits while at the same time denying their existence. Wendell Berry put it like this:

For this to happen in the stewardship of humans, there must be a cultural cycle, in harmony with the fertility cycle, also continuously turning in place. The cultural cycle is an unending conversation between old people and young people, assuring the survival of local memory, which has, as long as it remains local, the greatest practical urgency and value. This is what is meant, and is all that is meant, by “sustainability.” The fertility cycle turns by the law of nature. The cultural cycle turns on affection.

Affection for our family and our family’s place — that’s what Ruthie Leming taught me, in her death and dying, and in discerning her own Little Way. You can’t convince somebody by logical arguments why they should love someone or something. You can only show them, and hope the seed of affection falls in the heart’s fertile soil. Because of our own mutual brokenness, what affection Ruthie and I had for each other did not penetrate either of our hearts as it ought to have done. But through Abby, Tim, Laura, Big Show, John Bickham, the barefoot pallbearers, and everyone else in the town who held our family close, and held us up when we couldn’t stand on our own two feet, I was able to see the power of Ruthie’s love, given and returned. And I was able to see my own life in light of this love, and, finally, to feel for the first time in nearly thirty years, a profound and overwhelming affection for this place. It is not too much to say that by Ruthie’s suffering, I was healed. This was the most surprising journey I’ve ever made: into a new and hopeful way of looking at old familiar things.

I’ll end with one more excerpt from the book. It’s about a funeral of a dear old woman who was close to my folks. Clophine Toney — “Miss Clophine,” we always called her — was a Cajun woman who grew up in Avoyelles Parish. She was a farmer with sun-cured skin the color and texture of leather. She never learned to read. She was poor. But she worked hard, and had a stout and faithful heart. Her son James and I were in school together. Here, in Little Way, I write about her funeral, which her son preached:

Miss Clophine Toney died in hospice care that spring. She was 82. On the day of her burial, I picked Mam and Paw up and we drove to the funeral home in Zachary. James, her son and my childhood peewee baseball teammate, eulogized his mother. I knew my old friend had become a part-time evangelist, but I had never heard him preach. He stayed up all night praying for the right words to say. He stood behind the lectern next to his mother’s open casket, flexed his arms under his gray suit and black shirt, then turned the Spirit loose on the 40 or so mourners in the room.

“During Christmastime, my mother would go out and pick up pecans,” he began, in his husky voice. “She wasn’t very well educated. Today they tryin’ to educate us in everything. Gotta stay with the next game, gotta make sure we go to college. We can’t get too far behind, because we might not make enough money, and that would make our lives miserable. My God, we gettin’ educated in everything, but we not gettin’ educated in morals. We not gettin’ educated in sacrifice.”

James said his mother was poor and uneducated, but during the fall pecan season, she worked hard gathering pecans from under every tree she could find.

“She was carryin’ a cross,” he said. “Because let me tell you something, if you don’t sacrifice for your brother, if you don’t sacrifice for your neighbor, you not carrying your cross.”

Miss Clophine took the money she made selling pecans and went to the dollar store in St. Francisville, where, despite her own great need, she spent it on presents for friends and family.

“Aunt Grace told me the other day that of all the presents she got from everybody, those meant the most,” James said. “Why? Because there was so much sacrifice. She sacrificed everything she made, just to give.”

James pointed to Mam and Paw, sitting in the congregation.

“She used to give Mr. Ray and Miss Dorothy presents. And I’ll say this about Mr. Ray and Miss Dorothy Dreher, they were so close to my mother and my father. They sacrificed every year, whether my mother and father have enough to give them a gift of not. They gave. We talkin’ about sacrifice. We talkin’ about whether you’re carryin’ your cross today.”

As a child, James said, he would cross the river into Cajun country to stay with his Grandma Mose, Clophine’s mother. There he would eat a traditional dish called couche-couche, an old-timey Cajun version of fried cornmeal mush. Grandma Mose served couche-couche and milk nearly every morning, and little James loved it.

“But every now and then,” he continued, stretching his words for effect, “we wouldn’t eat couche-couche and milk. We’d eat something called bouille.”

Bouille, pronounced “boo-yee,” is cornmeal porridge, what the poorest of the Cajun poor ate.

“I didn’t like bouille. I frowned up. Mama made me that bouille sometime. Bouille tasted bad. It wasn’t good,” he said. “But let me tell you something: you may have family members, and you may have friends, that will feed you some bouille. It may not be food. They may not be treating you the way you think you ought to be treated. They may be doing this or doing that. You may be giving them a frown. But we may be talking about real sacrifice.”

James’s voice rose, and his arms began flying. This man was under conviction. He told the congregation that if a man lives long enough, he’s going to see his family, friends, and neighbors die, and no matter what their sins and failings, the day will come when we wish we had them back, flaws and all.

The preacher turned to his mother’s body, lying in the open casket on his left, and his voice began to crack.

“If my mama could give me that bouille one more time. If she could give me that bouille one more time. I wouldn’t frown up. I wouldn’t frown up. I would eat that bouille just like I ate that couche-couche. I would sacrifice my feelings. I would sacrifice my pride, if she could just give me that bouille one more time.”

I glanced at Mam, who was crying. Paw grimaced and held on to his cane.

“Let me tell you, you got family members and friends who ain’t treating you right,” James said, pointing at the congregation, his voice rising. “Listen to me! Sacrifice! Sacrifice! — when they givin’ you that bouille. Eat that bouille with a smile. Take what they givin’ you with a smile. That’s what Jesus did. He took that bouille when they was throwing it at him, when they was spittin’ at him, he took it. He sacrificed.

“My mother didn’t have much education, but she knew how to sacrifice. She knew that in the middle of the sacrifice, you smile. You smile.”

The evangelist looked once more at his mother’s body, and said, in a voice filled with the sweetest yearning, “Mama, I wish you could give me that bouille one more time.”

James stepped away, yielding the lectern to the hospice chaplain, who gave a more theologically learned sermon. Truth to tell, I didn’t listen closely. The power and the depth of what I had just heard from that Starhill country preacher, James Toney, and the lesson his mother’s life left to those who knew her, stunned me. And it made me thing of Ruthie, who lived and died as Miss Clophine had done: taking the bouille and giving, and smiling, all for love, as Jesus had done.

This was true religion. James showed me that. I tell you, the greatest preacher who ever stood in the pulpit at Chartres could not have spoken the Gospel any more purely.

The funeral director invited the congregation to come forward and say our last goodbyes to Miss Clophine before driving out to the cemetery. I walked forward with my arm around Mam’s shoulder. We stood together at Miss Clo’s side. Her body was scrawny and withered, and it was clad in white pajamas, a new set, with pink stripes. I felt Mam tremble beneath my arm. She drew her fingers to her lips, kissed them, and touched them to Miss Clophine’s forehead. In that moment, I thought of the Virgin Mary’s song, from the Gospel of Luke:

He hath scattered the proud in the conceit of their heart.

He hath put down the mighty from their seat,

And hath exalted the humble.

He hath filled the hungry with good things,

And the rich he hath sent empty away.

I know, I know: the funeral of a Cajun woman is only tangentially related to what Appelbaum said about LSU Tigers football. But it’s really not. We have a way of life down in Louisiana, the meaning of which makes no sense to the meritocracy. This is not always to our benefit, God knows, but it matters. These are the things that bind a people together, and give them the resilience to endure life’s ordeals without losing hope. The ideals that the country preacher James Toney talked about in eulogizing his mother — they are sustained and transmitted not in the classroom, but in the culture of ordinary people. And in Louisiana, that means a shared love for the LSU Tigers. Like I said, it’s a tribal religion. If you don’t understand that, you are likely to end up writing a gradgrindy piece about the lost productivity from Americans taking the day off to go to Fourth of July parades.

The Little Way of Ruthie Leming is a book-length answer to the Binyamin Appelbaum View Of The World. Appelbaum, an economist by training, sees no utility in college football, and thinks we’re all a bunch of idiot hicks for loving the LSU Tigers as much as we do. But I tell you, on your deathbed, you will not regret having not spent more time at the office, climbing the meritocratic ladder, but you might well regret not spending more time tailgating at Tiger Stadium (or whatever your local equivalent is, reader). The Binyamin Appelbaums of the world think that life is a syllogism and a spreadsheet; the people of Louisiana, by contrast, know that it’s really a poem and a parade.

UPDATE: Reader Jonah R.:

Ya know, I’m not a college sports fan. I think it’s a massive corruption of our already dubious system of higher education. It’s asinine and decadent to pay a college football coach $4 million a year.

But I understand this. I have family in Louisiana, and I’ve spent a lot of time there. Outsiders who don’t understand this celebration don’t get that it’s not just another example of locals getting all worked up over their dumb college team. It’s about living somewhere that has a distinctive culture and sense of place, within a set of conditions you couldn’t recreate from scratch if you wanted to. When you’re a repeat visitor to Louisiana, you start to realize: Hey, people actually like that they live here. And then, over time, you begin to understand why, and you realize that this is the sense of community that people get wistful about, but you have to experience it to understand it. How it’s created is a mystery, and fostering it is hard because it’s fragile, but it’s the thing people are yearning for whether they realize it or not, and it appears in the most unlikely places.

UPDATE.2: Reader Jeff R.:

That’s a lot of nice words about tradition and cultural heritage and whatnot, but I would have retorted something more to the point like “yeah, and in the enlightened, progressive state of New York, they cancelled classes at Syracuse because some prankster drew a swastika in the snow and OMG TEH NAZIS ARE COMING or something. We might not have the same academic standards as you Yanks, but at least we’ve managed to retain some vestiges of sanity on our college campuses.”

UPDATE.3: Reader Matt Grice:

The Binyamin Appelbaums of the world think that life is a syllogism and a spreadsheet; the people of Louisiana, by contrast, know that it’s really a poem and a parade.

I am not personally a college football fan— but I do remember, very very well, my first visit to Louisiana. Among many other memorable events from that visit, I found myself being invited to join in to a big meal being served on the sidewalk in front of somebody’s house in New Orleans, on St Patrick’s Day following the parade. The people whose house it was didn’t even know me, I was just the friend of a friend, but I was given a paper plate and encouraged to dig in with my hands — because the meal consisted of them emptying out a gigantic crab boiler (?) (I had never seen anything like it before) onto a big table covered with newspapers, so that there was a massive pile of bright red crawfish, ears of corn cut into fourths, pieces of potato, and coins of sausage. Plus a pallet-size pile of rolls of bread and plenty of beer, too. I am from New England and hadn’t grown up eating spicy foods, but during this one meal my aversion/inability to handle spiciness was cured — I had tears streaming down my face as I kept shoveling handfuls of the crawfish into my mouth, laughing back as the people I was eating with (good-naturedly) laughed at me, the Yankee, enduring this trial by fire. It was one of the best meals I have ever had in my life and from that day on I no longer feared chiles and peppers and Cajun seasoning and the rest of it. But also the spirit that one feels there, in Louisiana, is not like anywhere else in America that I have been. I’m very much a New Englander and a cold weather person at heart, but I really, really love New Orleans and Louisiana and I totally agree that it and its parades and holidays beat the Gradgrinds of the world any day. What a special place you have for a home. This is what Roger Scruton — a *really* great man, RIP– was talking about, I think.

Yes. And look, a lot of us fully know that we don’t value education as much as we should in this state. On Sunday, the front-page, above-the-fold story in the state’s biggest newspaper was about how Clemson values education far more than LSU does. This is a real problem with us. But that’s not what cancelling classes was about. It was about celebration and gratitude.

UPDATE.4: Son. Son!

If you don’t get the reference, this is an appropriation of south Louisiana slang (“Geaux Tigers”) for GOAT — Greatest Of All Time.

UPDATE.5: Reader Sublime Porte:

I am trying to put this into words, as this isn’t the easiest subject for me to broach without emotions causing my thoughts to become muddled.

Funny enough, while Applebaum is based out of New York, his snide Tweet–and your excellent, moving column–resonate well with this former New Yorker. I have no Starhill to return to, as the Starhill in which I was raised no longer exists. It might seem strange to someone from a small town to hear someone equating one of the 5 Boroughs to a small Louisiana town, but we grow up where we grow up, and it makes its impression on us. My surviving family members are the sort who would not understand why you’d want to live somewhere where being “average” is acceptable. They would also be very quick to tell you how much “nicer” my former home is now. How there are so many high end shops, how divey sports bars have been replaced by gastropubs staffed by mixologists, and how you can get an artisanal this that and the other thing delivered via Seamless or GrubHub or some damn app or another.

If you’re into that sort of thing, I can see why you might like it quite a bit. If you moved in after the fact, I can see why you’re not mourning a lost middle class ethnic enclave. It’s probably a pleasant place for a lefty upper class urbanite to call home.

It’s not where I grew up, though. Not in terms of culture, not in terms of who lives there, not in any sense but the street names. I feel no sense of homecoming in coming home, as “home” doesn’t really exist anymore.I think this has aided in causing my family relationships to be more strained than I would like, as they don’t understand my dislike for returning to a place that seems like a conquered city.

My wife and I are ultimately looking to moving abroad, as opting out of the Workism of the USA seems like our own, small BenOpt.

Someone told me that Appelbaum is actually based in DC. For purposes of this column, same difference. The Boston-NYC-DC meritocratic corridor is the same thing, symbolically.

UPDATE.6: I took out the personal insult that was in this piece earlier. I shouldn’t have said it. I apologize. I also found out that B. Appelbaum lives in DC, not NYC. As I’m not really talking here about NYC as NYC, but a mindset of coastal elites, I changed the headline to Acela, for the Acela Corridor (Boston to DC).

The post Coach O. Vs. The Acela Gradgrind appeared first on The American Conservative.

January 13, 2020

LSU Tigers: That Championship Season

Could you ask for a more perfect season than the one the LSU Tigers just had? Undefeated. The quarterback won the Heisman Trophy. And now, national champions.