Ta-Nehisi Coates's Blog, page 6

February 10, 2016

Against Endorsements

This morning I went on Democracy Now to discuss my critique of “class-first” policy as a way of ameliorating the effects of racism. In the midst of that discussion I made the point that one can maintain a critique of a candidate—in this case Bernie Sanders—and still feel that that candidate is deserving of your vote. Amy Goodman, being an excellent journalist, did exactly what she should have done—she asked if I were going to vote for Senator Sanders.

I, with some trepidation, answered in the affirmative. I did so because I’ve spent my career trying to get people to answer uncomfortable questions. Indeed, the entire reason I was on the show was to try to push liberals into directly addressing an uncomfortable issue that threatens their coalition. It seemed wrong, somehow, to ask others to step into their uncomfortable space and not do so myself. So I answered.

My answer has been characterized, in various places, as an “endorsement,” a characterization that I’d object to. Despite my very obvious political biases, I’ve never felt it was really my job to get people to agree with me. My first duty, as a writer, is to myself. In that sense I simply hope to ask all the questions that keep me up at night. My second duty is to my readers. In that sense, I hope to make readers understand why those questions are critical. I don’t so much hope that any reader “agrees” with me, as I hope to haunt them, to trouble their sense of how things actually are.

It’s really no different with Senator Sanders. The idea that anyone would cast a vote because of how I am casting my vote makes my skin crawl. It misses the point of everything I’ve been trying to do in my time at The Atlantic. The point is to get people to question, not to recruit them into a religion. Citizens are not sheep. They do not need shepherds, and even if they did I would be poorly qualified. I have thought quite deeply about the problem of racism in American society. I have thought somewhat deeply about inequality and the social safety net. I have though only modestly about foreign policy and the environment. And I haven’t thought much at all about net neutrality. I voted for the first time in 2008, following years of skepticism about electoral politics. Whatever. The point is that this is not the record of someone who should be telling other citizens how to vote.

I know what I know, and not much more. And one thing I learned while The Horde was active was to never confuse the perch I enjoy here, one that is as much a matter of chance as anything else, with broad knowledge. So I am no position to offer an “endorsement” to Sanders—one he did not seek, and does not need.

It is important to say this not just as a writer, but as a black writer. Too often individuals are appointed to speak for black people. I don’t want any part of it. Black voters deserve to be addressed in all of their beautiful and wonderful complications, not through the lens of unelected “thought-leaders.” I was asked a question. I tried to answer it honestly. And that’s really all I have.

February 8, 2016

The Enduring Solidarity of Whiteness

Tulsa burns in the race riots of 1921. Wikimedia

There have been a number of useful entries in the weeks since Senator Bernie Sanders declared himself against reparations. Perhaps the most clarifying comes from Cedric Johnson in a piece entitled, “An Open Letter To Ta-Nehisi Coates And The Liberals Who Love Him.” Johnson’s essay offers those of us interested in the problem of white supremacy and the question of economic class the chance to tease out how, and where, these two problems intersect. In Johnson’s rendition, racism, in and of itself, holds limited explanatory power when looking at the socio-economic problems which beset African Americans. “We continue to reach for old modes of analysis in the face of a changed world,” writes Johnson. “One where blackness is still derogated but anti-black racism is not the principal determinant of material conditions and economic mobility for many African Americans.”

Johnson goes on to classify racism among other varieties of -isms whose primary purpose is “to advance exploitation on terms that are most favorable to investor class interests.” From this perspective, the absence of specific anti-racist solutions from Bernie Sanders, as well as his rejection of reparations, make sense. By Johnson’s lights, racism is a secondary concern, and to the extent that it is a concern at all, it is weapon deployed to advance the interest of a plutocratic minority.

At various points in my life, I have subscribed to some version of Johnson’s argument. I did not always believe in reparations. In the past, I generally thought that the problem of white supremacy could be dealt through the sort of broad economic policy favored by Johnson and his candidate of choice. But eventually, I came to believe that white supremacy was a force in and of itself, a vector often intersecting with class, but also operating independent of it.

Nevertheless, my basic feelings about the kind of America in which I want to live have not changed. I think a world with equal access to safe, quality, and affordable education; with the right to health care; with strong restrictions on massive wealth accumulation; with guaranteed childcare; and with access to the full gamut of birth-control, including abortion, is a better world. But I do not believe that if this world were realized, the problem of white supremacy would dissipate, anymore than I believe that if reparations were realized, the problems of economic inequality would dissipate. In either case, the notion that one solution is the answer to the other problem is not serious policy. It is a palliative.

Unfortunately, palliatives are common these days among many of us on the left. In a recent piece, I asserted that western Europe demonstrated that democratic-socialist policy, alone, could not sufficiently address the problem of white supremacy. Johnson strongly disagreed with this:

Coates’s sweeping mischaracterization diminishes the actual impact that social-democratic and socialist governments have historically had in improving the labor conditions and daily lives of working people, in Europe, the United States, and for a time, across parts of the Third World.

There is not a single word in this response relating to race and racism in Western Europe or anything remotely closely to it. Instead, Johnson proposes to bait with race, and then switch to class. He swaps “labor conditions and daily lives of working people” in for “victims of white supremacy” and prays that the reader does not notice. Indeed, one might just as easily note that the advance of indoor plumbing, germ theory, and electricity have improved “the labor conditions and daily lives of working people,” and this would be no closer to actual engagement.

This pattern—strident rhetoric divorced from knowable fact—marks Johnson’s argument. Reparations, he tells us, do not emerge from the “felt needs of the majority of blacks,” a claim that is hard to square with the fact that a majority of blacks support reparations. Instead, he argues, the claim for reparations emerges from a cabal of “anti-racist liberals” and “black elites” seeking to make a “territorial-identitarian claim for power.” In fact, the reparations movement runs the gamut from the victims of Jon Burge, to those targeted by North Carolina’s eugenics campaign, to those targeted by the same campaign in Virginia, to those targeted by “Massive Resistance” in the same state, to the descendants of those devastated by the Tulsa pogrom. Are the black people of Tulsa who suffered aerial bombing at the hands of their own government“black elites” in pursuit of “territorial-identitarian claim?” Or are they something far simpler—people who were robbed and believe they deserve to be compensated?

Johnson denigrates recompense by asserting that the demands for reparations have not “yielded one tangible improvement in the lives of the majority of African Americans.” This is also true of single-payer health care, calls to break up big banks, free public universities, and any other leftist policy that has yet to come to pass. For a program to have effect, it has to actually be put in effect. Why would reparations be any different?

But ultimately, Johnson doesn’t reject reparations because he doesn’t think they would work, but because he doesn’t believe specific black injury through racism actually exists. He favors a “more Marxist class-oriented analysis” over the notion of treating “black poverty as fundamentally distinct from white poverty.” Johnson declines to actually investigate this position and furnish evidence—even though such evidence is not really hard to find.

(The Washington Post)

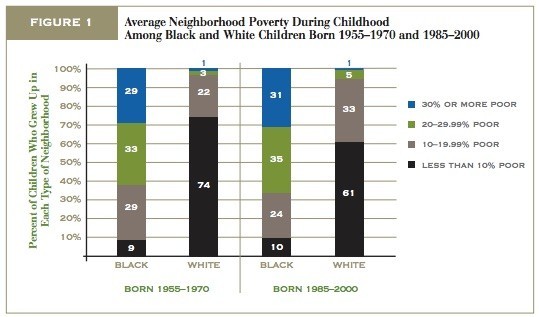

(The Washington Post)Courtesy of Emily Badger, this is a chart of concentrated poverty in America—that is to say families which are both individually poor and live in poor neighborhoods. Whereas individual poverty deprives one of the ability to furnish basic needs, concentrated poverty extends out from the wallet out to the surrounding institutions—the schools, the street, the community center, the policing. If individual poverty in America is hunger, neighborhood poverty is a famine. As the chart demonstrates, the black poor are considerably more subject to famine than the white poor. Indeed, so broad is this particular famine that its reach extends out to environs that most would consider well-nourished.

As the chart above demonstrates, neighborhood poverty threatens both black poor and nonpoor families to such an extent that poor white families are less likely to live in poor neighborhoods than nonpoor black families. This is not an original finding. The sociologist Robert Sampson finds that:

….racial differences in neighborhood exposure to poverty are so strong that even high-income blacks are exposed to greater neighborhood poverty than low-income whites. For example, nonpoor blacks in Chicago live in neighborhoods that are nearly 30 percent in poverty—traditionally the definition of “concentrated poverty” areas—whereas poor whites lives in neighborhoods with 15 percent poverty, about the national average.*

In its pervasiveness, concentration, and reach across class lines, black poverty proves itself to be “fundamentally distinct” from white poverty. It would be much more convenient for everyone on the left if this were not true—that is to say if neighborhood poverty, if systemic poverty, menaced all communities equally. In such a world, one would only need to craft universalist solutions for universal problems.

But we do not live that world. We live in this one:

Patrick Sharkey “Neighborhoods And The Black White Mobility Gap”

Patrick Sharkey “Neighborhoods And The Black White Mobility Gap”This chart by sociologist Patrick Sharkey quantifies the degree to which neighborhood poverty afflicts black and white families. Sociologists like Sharkey typically define a neighborhood with a poverty rate greater than 20 percent as “high poverty.” The majority of black people in this country (66 percent) live in high-poverty neighborhoods. The vast majority of whites (94 percent) do not. The effects of this should concern anyone who believes in a universalist solution to a particular affliction. According to Sharkey:

Neighborhood poverty alone, accounts for a greater portion of the black-white downward mobility gap than the effects of parental education, occupation, labor force participation, and a range of other family characteristics combined.

No student of the history of American housing policy will be shocked by this. Concentrated poverty is the clear, and to some extent intentional, result of the segregationist housing policy that dominated America through much of the 20th century.

But the “fundamental differences” between black communities and white communities do not end with poverty or social mobility.

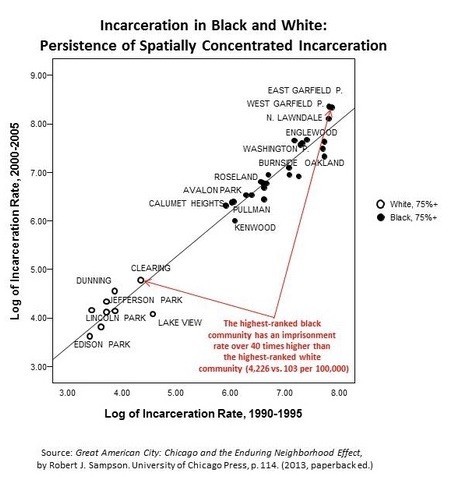

In the chart above, Sampson plotted the the incarceration rate in Chicago from the onset imprisonment boom to its height. As Sampson notes, the incarceration rate in the most afflicted black neighborhood is 40 times worse than the incarceration rate in the most afflicted white neighborhood. But more tellingly for our purposes, incarceration rates for white neighborhoods bunch at the lower end, while incarceration rates for black neighborhoods bunch at the higher end. There is no gradation, nor overlap between the two. It is almost as if, from the perspective of mass incarceration, black and white people—regardless of neighborhood—inhabit two “fundamentally distinct”worlds.

The pervasive and distinctive effects of racism are viewable at every level of education from high school drop-outs (see pages 13-14 of this Pew report, especially) to Ivy league graduates. I strongly suspect that if one were to investigate public-health outcomes, exposure to pollution, quality of public education or any other vector relating to socio-economic health, a similar pattern would emerge.[image error]

Such investigations are of little use to Johnson, who prefers ideas over people, and jargon divorced of meaningful investigation. The “black managerial elite” are invoked without any attempt to quantify their numbers and power. “Institutional racism” is presented as a figment, without actually defining what it is, and why, in Johnson’s mind, it is insignificant. “Black plunder” is invoked in Chicago, with no effort to examine its effects or compare it to “white plunder.” Johnson tells us that “universal social policies” and an expanded “public sector” built the black middle class. He seems unaware that the same is true of the “white middle class.” A useful question might arise from such awareness: Has the impact of “universalist social policies” been equal across racial lines? Johnson can not be bothered with such questions as he is preoccupied with —in his own words—“solidarity.”

I am not opposed to solidarity, in and of itself, but I would have its basis made clear. When an argument is divorced of this clarity, then deflection, subject-changing, abstraction, and head-fakes—as when Johnson exchanges“laborers” for the victims of white supremacy—all become inevitable.

Bombast, too. In Johnson’s rendition, black writers who trouble his particular “solidarity” are not sincerely disagreeing with his ideas, they are assuaging “white guilt” and doing the dirty work of interpreting black people for “white publics.” Johnson lobs this charge as though he is not himself interpreting for white publics, as though he were holding forth from the offices of The Amsterdam News. And then he lobs a good deal more:

...Coates’s latest attack on Sanders, and willingness to join the chorus of red-baiters, has convinced me that his particular brand of antiracism does more political harm than good, further mystifying the actual forces at play and the real battle lines that divide our world.

This not the language of debate. It is the vocabulary of compliance. In this way, a strong and important disagreement on the left becomes something darker. Critiquing the policies of a presidential candidate constitutes an “attack.” A call for intersectional radicalism is “red-baiting.” And the argument for reparations does “more political harm than good.”

The feeling is not mutual. I think Johnson’s ideas originate not in some diabolical plot, but in an honest and deeply held concern for the plundered peoples of the world. Whatever their origin, there is much in Johnson’s response worthy of study, and much more which all who hope for struggle across the manufactured line of race might learn from. Johnson’s distillation of the Readjuster movement, his emphasis on the value of the postal service and public-sector jobs, and his insistence on telling a broader story of housing and segregation add considerable value to the present conversation. His insistence that airing arguments to the contrary is harmful does not.

It is not even that a solidarity premised on the suppression of debate—a solidarity of ignorance—is wrong in and of itself, though it is. It is that a solidarity of ignorance blinds one to complicating factors:

Social exclusion and labor exploitation are different problems, but they are never disconnected under capitalism. And both processes work to the advantage of capital. Segmented labor markets, ethnic rivalry, racism, sexism, xenophobia, and informalization all work against solidarity. Whether we are talking about antebellum slaves, immigrant strikebreakers, or undocumented migrant workers, it is clear that exclusion is often deployed to advance exploitation on terms that are most favorable to investor class interests.

No. Social exclusion works for solidarity, as often as it works against it. Sexism is not merely, or even primarily, a means of conferring benefits to the investor class. It is also a means of forging solidarity among “men,” much as xenophobia forges solidarity among “citizens,” and homophobia makes for solidarity among “heterosexuals.” What one is is often as important as what one is not, and so strong is the negative act of defining community that one wonders if all of these definitions—man, heterosexual, white—would evaporate in absence of negative definition.

That question is beyond my purview (for now). But what is obvious is that the systemic issues that allowed men as different as Bill Cosby and Daniel Holtzclaw to perpetuate their crimes, the systemic issues which long denied gay people, no matter how wealthy, to marry and protect their families, can not be crudely reduced to the mad plottings of plutocrats. In America, solidarity among laborers is not the only kind of solidarity. In America, it isn’t even the most potent kind.

The history of the very ideas Johnson favors evidences this fact. At every step, “universalist” social programs have been hampered by the idea of becoming, and remaining, forever white. So it was with the New Deal. So it is with Obamacare. So it would be with President Sanders. That is not because the white working class labors under mass hypnosis. It is because whiteness confers knowable, quantifiable privileges, regardless of class—much like “manhood” confers knowable, quantifiable privileges, regardless of race. White supremacy is neither a trick, nor a device, but one of the most powerful shared interests in American history.

And that, too, is solidarity.

Related Video

January 27, 2016

The Case for Considering Reparations

President Ronald Reagan signs the 1988 bill granting reparations to the victims of the wartime internment of the Japanese. Ronald Reagan Presidential Library

Kevin Drum offers an interesting, and familiar, rebuttal to the reparations argument:

A couple of years ago Coates famously wrote an Atlantic article titled “The Case for Reparations,” and after reading it I concluded that he was reticent about reparations too. He certainly made the case that black labor and wealth had been plundered by whites for centuries—something that few people deny anymore—but when it came time to talk about concrete restitution for this, he tap danced gingerly.

Drum believes that I was “reticent” about reparations because I did not talk about “concrete restitution” in the article. Of course, the article was not a plan for reparations. It was a case for reparations. That was the headline. Even so, I did offer some details on the proposals which have been put forth by scholars over the years:

In the 1970s, the Yale Law professor Boris Bittker argued in The Case for Black Reparations that a rough price tag for reparations could be determined by multiplying the number of African Americans in the population by the difference in white and black per capita income. That number—$34 billion in 1973, when Bittker wrote his book—could be added to a reparations program each year for a decade or two. Today Charles Ogletree, the Harvard Law School professor, argues for something broader: a program of job training and public works that takes racial justice as its mission but includes the poor of all races.

With that said, I concluded that the next-best step was to back John Conyers’s H.R. 40 bill, which proposed to study slavery and its legacy, and to determine whether reparations were feasible. This seemed intelligent, given that is the exact same path taken by one of the more successful reparations efforts—those awarded to Japanese Americans interned during World War II. It was also actionable—a bill in Congress that could serve as a rallying point—as opposed to merely rhetorical. Finally, although studies certainly end up in the dust-bin of history all the time, without some sort of official document tallying up the specific costs of some three centuries of injury, it seems relatively useless to argue for a plan for payment.

This did not stop people from demanding specifics. These demands always struck me as akin to demanding a payment plan for something one has neither decided one needs nor is willing to purchase. Nevertheless, after my colleague David Frum wrote a piece making the same argument as Drum, I offered the following response:

Even if one feels that slavery was too far into the deep past (and I do not, because I view this as a continuum) the immediate past is with us. Identifying the victims of racist housing policy in this country is not hard. Again, we have the maps. We have the census. We could set up a claims system for black veterans who were frustrated in their attempt to use the G.I. Bill. We could then decide what remedy we might offer these people and their communities. And there is nothing “impractical” about this.

The problem of reparations has never been practicality. It has always been the awesome ghosts of history.

My case for reparations was not centered on long-dead enslaved black people, but actual living African Americans who’d been wronged, well within living memory. The wrong was massive and perpetrated in virtually every major city in the country. My proposal addressed the thrust of my article—housing discrimination and red-lining. There is nothing dodgy, canny, or hard to understand about it. I made that argument it in 2014. I have made it several times in interviews since. This has not stopped people from asking for something even more specific. I have, with some regularity, pointed them to this excellent paper from the Duke economist, and tireless reparations proponent, Sandy Darity, which discusses “the size of a reparations payment and how the way which it is financed and distributed effects the income of blacks and nonblacks.”

That has not halted the demand for more specifics, generally from people—like Drum—who don’t actually believe reparations are due in the first place. Nevertheless, the most striking portion of Drum’s rebuttal is not his obsession with divining an installment plan for a debt he has no interest in paying, it is the preciousness of his worldview. Drum blithely asserts that “few people” deny that “black labor and wealth” had been plundered for centuries. He offers no evidence for this sweeping generalization.

That isn’t because there’s no evidence to be found. Indeed in 2014, a YouGov and Huffington Post poll revealed (unsurprisingly) that the vast majority of white Americans—75 percent—opposed reparations in all forms. White Americans did not oppose reparations because they were flummoxed by the practicalities of making good on the debt. They opposed them because, ultimately, they didn’t think the legacies of slavery and Jim Crow were any longer that big of a deal. Seventy-eight percent of White Americans said that the legacy of slavery is either a “minor factor” or “no factor at all” in today’s wealth gap. Sixty-four percent of whites thought the same of Jim Crow.

The task I took on with “The Case For Reparations” was to counter this thinking—to show how the damage of slavery and Jim Crow was extended and compounded by ongoing discrimination, how this continues to devastate black communities, and why a debt was owed. Perhaps Drum lives in a country where white people are deeply cognizant of American history and openly confess to pillage and plunder, and thus feels no case even needs to be made. One sees this belief evidenced in Drum’s post just yesterday, where he asserted his complete unawareness of one of the most significant trends in American historiography (“Dunning? Never heard of the guy.”) Ignorance is no great sin—there are always things we haven’t read or don’t know. But arguing out of admitted ignorance, opining despite one’s ignorance, isn’t ignorance at all—it’s incuriosity.

Incuriosity is what most “practical” arguments against reparations boil down to. A sincerely curious reader might well have looked at Boris Bittker’s work, or Sandy Darity’s work, or Charles Ogletree’s work. Curiosity might compel one to investigate the victims of the Tulsa pogrom, consider the reparations offered to the victims of John Burge, or the victims of North Carolina’s sterilization campaign. Or curiosity might compel one to support John Conyers’s bill to actually see whether these smaller, successful reparations claims might illuminate something larger.

Drum’s argument implies that before any of this can be answered—or even really asked—a detailed plan of repayment must first be constructed. It suggests that assailants should only consider paying compensation after their victims have offered spreadsheets detailing how best to dispense it. Drum believes that the problem with the bringing pirates to justice is the distribution system. I believe the problem is piracy itself, and grand piracy always extends beyond the act of theft. It requires the construction of an elaborate architecture to either justify the theft, or to justify non-compensation for the theft.

I have always believed that one of the great benefits of considering reparations lies in their potential to expand the American political imagination. Before there could be a Republican Party, abolitionists first had to imagine emancipation. A country that could actively contemplate atoning for plunder, by devoting significant resources to compensating its victims, would be a very different nation than one we live in now. You don’t get to that different country by waiting to talk about it.

And in this sense the conversation ends right where it began: Liberals and radicals see no problem imagining a socialist presidency. They do not demand specific details of how single-payer health care, free public-college tuition, and the break-up of big banks would make it through a Republican Congress. They are not wrong. God bless them and their radical imagination. I mean it. I just want them to imagine more. Like the movie says—You mustn’t be afraid to dream a little bigger, darling.

January 26, 2016

Hillary Clinton Goes Back to the Dunning School

Library of Congress

Last night Hillary Clinton was asked what president inspired her the most. She offered up Abraham Lincoln, gave a boilerplate reason why, and then said this:

You know, he was willing to reconcile and forgive. And I don't know what our country might have been like had he not been murdered, but I bet that it might have been a little less rancorous, a little more forgiving and tolerant, that might possibly have brought people back together more quickly.

But instead, you know, we had Reconstruction, we had the re-instigation of segregation and Jim Crow. We had people in the South feeling totally discouraged and defiant. So, I really do believe he could have very well put us on a different path.

Clinton, whether she knows it or not, is retelling a racist—though popular—version of American history which held sway in this country until relatively recently. Sometimes going under the handle of “The Dunning School,” and other times going under the “Lost Cause” label, the basic idea is that Reconstruction was a mistake brought about by vengeful Northern radicals. The result was a savage and corrupt government which in turn left former Confederates, as Clinton puts, it “discouraged and defiant.”

A sample of the genre is offered here by historian Ulrich Phillips:

Lincoln in his plan of reconstruction had shown unexpected magnanimity; the Republican party, discarding that obnoxious name, had officially styled itself merely Unionist; and the Northern Democrats, although outvoted, were still a friendly force to be reckoned upon … With Johnson then on Lincoln's path “back to normalcy”, Southern hearts were lightened only to sink again when radicals in Congress, calling themselves Republicans once more, overslaughed the Presidential programme and set events in train which seemed to make "the Africanization of the South" inescapable. To most of the whites, doubtless, the prospect showed no gleam of hope.

Notably absent from it is the fact that Lincoln was killed by a white supremacist, that Johnson was a white supremacist who tried to curtail virtually all rights black people enjoyed, that the “hope” of white Southerners lay in the pillage of black labor, that this was accomplished through a century-long campaign of domestic terrorism, and that for most of that history the federal government looked the other way, while state and local governments were complicit.

Yet until relatively recently, this self-serving version of history was dominant. It is almost certainly the version fed to Hillary Clinton during her school years, and possibly even as a college student. Hillary Clinton is no longer a college student. And the fact that a presidential candidate would imply that Jim Crow and Reconstruction were equal, that the era of lynching and white supremacist violence would have been prevented had that same violence not killed Lincoln, and that the violence was simply the result of rancor, the absence of a forgiving spirit, and an understandably “discouraged” South is chilling.

I have spent the past two years somewhat concerned about the effects of national amnesia, largely because I believe that a problem can not be effectively treated without being effectively diagnosed. I don’t know how you diagnose the problem of racism in America without understanding the actual history. In the Democratic Party, there is, on the one hand, a candidate who seems comfortable doling out the kind of myths that undergirded racist violence. And on the other is a candidate who seems uncomfortable asking whether the history of racist violence, in and of itself, is worthy of confrontation.

These are options for a party of amnesiacs, for people whose politics are premised on forgetting. This is not a brief for staying home, because such a thing doesn’t actually exist. In the American system of government, refusing to vote for the less-than-ideal is a vote for something much worse. Even when you don’t choose, you choose. But you can choose with your skepticism fully intact. You can choose in full awareness of the insufficiency of your options, without elevating those who would have us forget into prophets. You can choose and still push, demanding more. It really isn’t too much to say, if you’re going to govern a country, you should know its history.

January 24, 2016

Bernie Sanders and the Liberal Imagination

Mark Kauzlarich / Reuters

Last week I critiqued Bernie Sanders for dismissing reparations specifically, and for offering up a series of moderate anti-racist solutions, in general. Some felt it was unfair to single out Sanders given that, on reparations, Sanders’s chief opponent Hillary Clinton holds the same position. This argument proposes that we abandon the convention of judging our candidates by their chosen name:

Youth unemployment for African American kids is 51 percent. We have more people in jail than any other country. So yes, count me as a radical. I want to invest in jobs and education for our young people rather than jails and incarceration.

When a candidate points to high unemployment among black youth, as well as high incarceration rates, and then dubs himself a radical, it seems prudent to ask what radical anti-racist policies that candidate actually embraces. Hillary Clinton has no interest in being labeled radical, left-wing, or even liberal. Thus announcing that Clinton doesn’t support reparations is akin to announcing that Ted Cruz doesn’t support a woman’s right to choose. The position is certainly wrong. But it is hardly a surprise, and doesn't run counter to the candidate’s chosen name.

What candidates name themselves is generally believed to be important. Many Sanders supporters, for instance, correctly point out that Clinton handprints are all over America’s sprawling carceral state. I agree with them and have said so at length. Voters, and black voters particularly, should never forget that Bill Clinton passed arguably the most immoral “anti-crime” bill in American history, and that Hillary Clinton aided its passage through her invocation of the super-predator myth. A defense of Clinton rooted in the claim that “Jeb Bush held the same position” would not be exculpatory. (“Law and order conservative embraces law and order” would surprise no one.) That is because the anger over the Clintons’ actions isn’t simply based on their having been wrong, but on their craven embrace of law and order Republicanism in the Democratic Party’s name.

One does not find anything as damaging as the carceral state in the Sanders platform, but the dissonance between name and action is the same. Sanders’s basic approach is to ameliorate the effects of racism through broad, mostly class-based policies—doubling the minimum wage, offering single-payer health-care, delivering free higher education. This is the same “A rising tide lifts all boats” thinking that has dominated Democratic anti-racist policy for a generation. Sanders proposes to intensify this approach. But Sanders’s actual approach is really no different than President Obama’s. I have repeatedly stated my problem with the “rising tide” philosophy when embraced by Obama and liberals in general. (See here, here, here, and here.) Again, briefly, treating a racist injury solely with class-based remedies is like treating a gun-shot wound solely with bandages. The bandages help, but they will not suffice.

There is no need to be theoretical about this. Across Europe, the kind of robust welfare state Sanders supports—higher minimum wage, single-payer health-care, low-cost higher education—has been embraced. Have these policies vanquished racism? Or has race become another rubric for asserting who should benefit from the state’s largesse and who should not? And if class-based policy alone is insufficient to banish racism in Europe, why would it prove to be sufficient in a country founded on white supremacy? And if it is not sufficient, what does it mean that even on the left wing of the Democratic party, the consideration of radical, directly anti-racist solutions has disappeared? And if radical, directly anti-racist remedies have disappeared from the left-wing of the Democratic Party, by what right does one expect them to appear in the platform of an avowed moderate like Clinton?

Mainstream liberal policy proposes to address this divide without actually targeting it, to solve a problem through category error.

Here is the great challenge of liberal policy in America: We now know that for every dollar of wealth white families have, black families have a nickel. We know that being middle class does not immunize black families from exploitation in the way that it immunizes white families. We know that black families making $100,000 a year tend to live in the same kind of neighborhoods as white families making $30,000 a year. We know that in a city like Chicago, the wealthiest black neighborhood has an incarceration rate many times worse than the poorest white neighborhood. This is not a class divide, but a racist divide. Mainstream liberal policy proposes to address this divide without actually targeting it, to solve a problem through category error. That a mainstream Democrat like Hillary Clinton embraces mainstream liberal policy is unsurprising. Clinton has no interest in expanding the Overton window. She simply hopes to slide through it.

But I thought #FeelTheBern meant something more than this. I thought that Bernie Sanders, the candidate of single-payer health insurance, of the dissolution of big banks, of free higher education, was interested both in being elected and in advancing the debate beyond his own candidacy. I thought the importance of Sanders’s call for free tuition at public universities lay not just in telling citizens that which is actually workable, but in showing them that which we must struggle to make workable. I thought Sanders’s campaign might remind Americans that what is imminently doable and what is morally correct are not always the same things, and while actualizing the former we can’t lose sight of the latter.

A Democratic candidate who offers class-based remedies to address racist plunder because that is what is imminently doable, because all we have are bandages, is doing the best he can. A Democratic candidate who claims that such remedies are sufficient, who makes a virtue of bandaging, has forgotten the world that should, and must, be. Effectively he answers the trenchant problem of white supremacy by claiming “something something socialism, and then a miracle occurs.”

No. Fifteen years ago we watched a candidate elevate class above all. And now we see that same candidate invoking class to deliver another blow to affirmative action. And that is only the latest instance of populism failing black people.

So “divisive” was Abraham Lincoln’s embrace of abolition that it got him shot in the head.

The left, above all, should know better than this. When Sanders dismisses reparations because they are “divisive” he puts himself in poor company. “Divisive” is how Joe Lieberman swatted away his interlocutors. “Divisive” is how the media dismissed the public option. “Divisive” is what Hillary Clinton is calling Sanders’s single-player platform right now.

So “divisive” was Abraham Lincoln’s embrace of abolition that it got him shot in the head. So “divisive” was Lyndon Johnson’s embrace of civil rights that it fractured the Democratic Party. So “divisive” was Ulysses S. Grant’s defense of black civil rights and war upon the Klan, that American historians spent the better part of a century destroying his reputation. So “divisive” was Martin Luther King Jr. that his own government bugged him, harassed him, and demonized him until he was dead. And now, in our time, politicians tout their proximity to that same King, and dismiss the completion of his work—the full pursuit of equality—as “divisive.” The point is not that reparations is not divisive. The point is that anti-racism is always divisive. A left radicalism that makes Clintonism its standard for anti-racism—fully knowing it could never do such a thing in the realm of labor, for instance—has embraced evasion.

This, too, leaves us in poor company. “Hillary Clinton is against reparations, too” does not differ from, “What about black-on-black crime?” That Clinton doesn’t support reparations is an actual problem, much like high murder rates in black communities are actual problems. But neither of these are actual answers to the questions being asked. It is not wrong to ask about high murder rates in black communities. But when the question is furnished as an answer for police violence, it is evasion. It is not wrong to ask why mainstream Democrats don’t support reparations. But when the question is asked to defend a radical Democrat’s lack of support, it is avoidance.

The need for so many (although not all) of Sanders’s supporters to deflect the question, to speak of Hillary Clinton instead of directly assessing whether Sanders’s position is consistent, intelligent, and moral hints at something terrible and unsaid. The terribleness is this: To destroy white supremacy we must commit ourselves to the promotion of unpopular policy. To commit ourselves solely to the promotion of popular policy means making peace with white supremacy.

If we can be inspired to directly address class in such radical ways, why should we allow our imaginative powers end there?

But hope still lies in the imagined thing. Liberals have dared to believe in the seemingly impossible—a socialist presiding over the most capitalist nation to ever exist. If the liberal imagination is so grand as to assert this new American reality, why when confronting racism, presumably a mere adjunct of class, should it suddenly come up shaky? Is shy incrementalism really the lesson of this fortuitous outburst of Vermont radicalism? Or is it that constraining the political imagination, too, constrains the possible? If we can be inspired to directly address class in such radical ways, why should we allow our imaginative powers end there?

These and other questions were recently put to Sanders. His answer was underwhelming. It does not have to be this way. One could imagine a candidate asserting the worth of reparations, the worth of John Conyers H.R. 40, while also correctly noting the present lack of working coalition. What should be unimaginable is defaulting to the standard of Clintonism, of “Yes, but she’s against it, too.” A left radicalism that fails to debate its own standards, that counsels misdirection, that preaches avoidance, is really just a radicalism of convenience.

January 22, 2016

The People Vs. T'Challa

(Brian Stelfreeze)

Above we have a sketch of T’Challa dabbin’ on dem folks courtesy of Brian Stelfreeze. Obviously, I can’t really take much credit for this sketch. Brian has this great ability, not just to interpret script direction, but to actually add on and make something new and beautiful.

With that said I’d like to talk some about T’Challa’s major challenge in this first season of Black Panther. (Here’s hoping there will be more.) When I accepted the task of writing the new Black Panther comic, I was faced with an obvious question—Who is this guy? There was the obvious and the known—T’Challa is the ruler of the mythical African nation of Wakanda. But to write, I needed to develop a grounded theory of T’Challa’s great loves, small annoyances and everything in between. The grounding came from past depictions of T’Challa by writers like Don McGregor, Christopher Priest, Reginald Hudlin and Jonathan Hickman.

I also had to create some sort of working theory about Wakanda, and to the extent to which I came to one it is this: Wakanda is a contradiction. It is the most advanced nation on Earth, existing under one of the most primitive forms of governance on Earth. In the present telling, Wakanda’s technological superiority goes back centuries. Presumably it’s population is extremely well educated, and yet that population willingly accedes to rule by blood. T’Challa descends from an unbroken line of kings, all who’ve taken up the mantle of the Black Panther. But if you’ve ever studied monarchy, it becomes immediately apparent that the aptitude, or even the desire, to govern isn’t genetic.

Leaving aside the problems of reconciling absolute monarchy with ultra-modernism, there are the actual events in Wakanda which have happened under previous writers. In recent years Wakandans have endured a coup courtesy of the villainous Achebe, another courtesy Dr. Doom, the murder of two of T’Challa top lieutenants, a cataclysmic flood courtesy of Prince Namor, the subsequent dissolution of a royal marriage, and finally decimation and conquest at the hands of Thanos’ Black Order. Wakanda had always prided itself on having never been conquered. This is no longer true. What, then, is the country if it is as vulnerable as all others? And what happens to a state when its absolute monarch can no longer fulfill the base requirement of any government—securing the safety of their people?

(Brian Stelfreeze, Laura Martin.)

January 19, 2016

Why Precisely Is Bernie Sanders Against Reparations?

Bernie Sanders speaking at the Iowa Black and Brown Forum on January 11, 2016 Aaron P. Bernstein / Reuters

Last week Bernie Sanders was asked whether he was in favor of “reparations for slavery.” It is worth considering Sanders’s response in full:

No, I don’t think so. First of all, its likelihood of getting through Congress is nil. Second of all, I think it would be very divisive. The real issue is when we look at the poverty rate among the African American community, when we look at the high unemployment rate within the African American community, we have a lot of work to do.

So I think what we should be talking about is making massive investments in rebuilding our cities, in creating millions of decent paying jobs, in making public colleges and universities tuition-free, basically targeting our federal resources to the areas where it is needed the most and where it is needed the most is in impoverished communities, often African American and Latino.

For those of us interested in how the left prioritizes its various radicalisms, Sanders’s answer is illuminating. The spectacle of a socialist candidate opposing reparations as “divisive” (there are few political labels more divisive in the minds of Americans than socialist) is only rivaled by the implausibility of Sanders posing as a pragmatist. Sanders says the chance of getting reparations through Congress is “nil,” a correct observation which could just as well apply to much of the Vermont senator’s own platform. The chances of a President Sanders coaxing a Republican Congress to pass a $1 trillion jobs and infrastructure bill are also nil. Considering Sanders’s proposal for single-payer health-care, Paul Krugman asks, “Is there any realistic prospect that a drastic overhaul could be enacted any time soon—say, in the next eight years? No.”

Sanders is a lot of things, many of them good. But he is not the candidate of moderation and unification, so much as the candidate of partisanship and radicalism. There is neither insult nor accolade in this. John Brown was radical and divisive. So was Eric Robert Rudolph. Our current sprawling megapolis of prisons was a bipartisan achievement. Obamacare was not. Sometimes the moral course lies within the politically possible, and sometimes the moral course lies outside of the politically possible. One of the great functions of radical candidates is to war against equivocators and opportunists who conflate these two things. Radicals expand the political imagination and, hopefully, prevent incrementalism from becoming a virtue.

Unfortunately, Sanders’s radicalism has failed in the ancient fight against white supremacy. What he proposes in lieu of reparations—job creation, investment in cities, and free higher education—is well within the Overton window, and his platform on race echoes Democratic orthodoxy. The calls for community policing, body-cameras, and a voting-rights bill with pre-clearance restored— all are things that Hillary Clinton agrees with. And those positions with which she might not agree address black people not so much as a class specifically injured by white supremacy, but rather, as a group which magically suffers from disproportionate poverty.

This is the “class first” approach, originating in the myth that racism and socialism are necessarily incompatible. But raising the minimum wage doesn’t really address the fact that black men without criminal records have about the same shot at low-wage work as white men with them; nor can making college free address the wage gap between black and white graduates. Housing discrimination, historical and present, may well be the fulcrum of white supremacy. Affirmative action is one of the most disputed issues of the day. Neither are addressed in the “racial justice” section of Sanders platform.

Sanders’s anti-racist moderation points to a candidate who is not merely against reparations, but one who doesn’t actually understand the argument. To briefly restate it, from 1619 until at least the late 1960s, American institutions, businesses, associations, and governments—federal, state and local—repeatedly plundered black communities. Their methods included everything from land-theft, to red-lining, to disenfranchisement, to convict-lease labor, to lynching, to enslavement, to the vending of children. So large was this plunder that America, as we know it today, is simply unimaginable without it. Its great universities were founded on it. Its early economy was built by it. Its suburbs were financed by it. Its deadliest war was the result of it.

One can’t evade these facts by changing the subject. Some months ago, black radicals in the Black Lives Matters movement protested Sanders. They were, in the main, jeered by the white left for their efforts. But judged by his platform, Sanders should be directly confronted and asked why his political imagination is so active against plutocracy, but so limited against white supremacy. Jim Crow and its legacy were not merely problems of disproportionate poverty. Why should black voters support a candidate who does not recognize this?

Reparations is not one possible tool against white supremacy. It is the indispensable tool against white supremacy.

If not even an avowed socialist can be bothered to grapple with reparations, if the question really is that far beyond the pale, if Bernie Sanders truly believes that victims of the Tulsa pogrom deserved nothing, that the victims of contract lending deserve nothing, that the victims of debt peonage deserve nothing, that that political plunder of black communities entitle them to nothing, if this is the candidate of the radical left—then expect white supremacy in America to endure well beyond our lifetimes and lifetimes of our children. Reparations is not one possible tool against white supremacy. It is the indispensable tool against white supremacy. One cannot propose to plunder a people, incur a moral and monetary debt, propose to never pay it back, and then claim to be seriously engaging in the fight against white supremacy.

My hope was to talk to Sanders directly, before writing this article. I reached out repeatedly to his campaign over the past three days. The Sanders campaign did not respond.

January 12, 2016

Bill Cosby and His Enablers

Mark Makela / Reuters

Long before the Black Lives Matter movement raised the problem of immoral police (and vigilante) violence, African Americans grappled with its reality and the seemingly impenetrable logic which undergirds it. The mind reels at the justifications proffered for killing a 12-year-old child, or the calculation that finds an officer raining blows on someone’s grandmother, or the science that encourages a man to fire a gun over his shoulder and into a crowd.

Fiction undergirds all of these acts—of furtive movements, reasonable fear, and therapy through violence. So strong is the power of the legitimizing narrative, that even those who are victims of these violent fictions are rarely deterred from crafting justifying fictions of their own. In the 19th and 20th century, the old discriminations against white ethnics—“no Irish need apply”—did very little to prevent those same white ethnics from engaging in anti-black racism. Yet for a starker example, it may well better to look closer to home.

Two weeks ago, the comedian Eddie Griffin was asked about the torrent of sexual assault accusations made against Bill Cosby. “Did he rape these bitches?” asked Griffin. “All of them said the same thing—‘We went to the room.’ Why would you go to the room of a known married man?” Griffin seemed perplexed that Cosby’s accusers did not immediately report being assaulted by a millionaire and one of the most powerful black men in show business. “30 years?” asked Griffin. “I don’t understand that. That’s like a motherfucker robbing me, and I wait 30 years to call the police.”

Close observers of the long struggle against white supremacy will find Griffin’s formulation familiar. There is, off the top, a ruthless unacquaintance with the facts. Cosby has been accused of assaulting women, not merely in hotel rooms, but at his home, at a celebrity tennis tournament, backstage at show in Las Vegas, backstage at The Tonight Show, and on the set of the Cosby Show. It is not very hard to know this—two minutes of Googling will suffice.

But the narrative of cunning “bitches” arriving at the hotel room of a married man has a kind of resonance that drugging women on the set of a family-friendly television show does not. Similarly, the narrative of thuggish black boys in hoodies has a kind of resonance that child-murder does not. In fact, there is no real difference in claiming that a woman in a married man’s hotel room forgoes the right to her body, and asserting that a black boy wearing a hoodie forgoes the right to his. Brutality is brutality, and it always rests on a bed of lies.

Too, it rests on animus. One official of the pirate government of Ferguson joked that dogs might qualify for welfare because they are “mixed in color, unemployed, lazy, can’t speak English and have no frigging clue who their Daddies are.” Cosby’s accusers are “bitches.” Last year an incredulous Damon Wayans tried to understand the behavior of some of Cosby’s victims. “Bitch, how many times did it happen?” asked Wayans. “Just listen to what they're saying and some of them really [are] un-rape-able. I just look at them and go, 'You don't want that. Get out of here.’”

Whether for the thrill of domination or the balancing of a municipal budget, animus justifies plunder. The scorned enjoy no rights that the powerful must respect. And like all powerful elements seeking to sanctify their use of violence, these apologists employ history selectively.“How big is his penis that it gives you amnesia for 40 years?” continued Wayans. Of course Cosby has faced many more recent claims—including the 2004 incident for which he was recently arrested, in which civil claims were first filed in 2005.

No matter. The unspoken logic here holds that there has always been some sort of legitimate system for hearing and adjudicating plunder. In the case of rape, no such system existed 40 years ago, 30 years ago or 20 years ago. It’s arguable that it still does not exist today. In much the same way, no such system existed to bring to the victims of the Chicago police officer John Burge until decades after his campaign of torture began. Burge began torturing black Chicagoans in 1972, and was never convicted by the local courts. Reparations were not granted until last year.

Criminals flourish when no credible system exists to adjudicate the claims of their victims. When asked why they did not report the crimes of Daniel Holtzclaw, a police officer charged with targeting and raping poor black women, many of his victims said the same thing: Who would have believed them? Effectively Holtzclaw had found a hole in the law, and he was only convicted after he deviated from his pattern.

Much like it is impossible to understand the killing of Tamir Rice as murder without some study of racism, it is impossible to imagine Bill Cosby as a rapist without understanding the larger framework. (For instance, it took until 1993 for all 50 states to criminalize marital rape.) Rape is systemic. And like all systems of brutality it does not exist merely at the pleasure of its most direct actors. It depends on a healthy host-body of people willing to look away.

It is always particularly painful to see those who have been victimized by a habitual looking away to then turn around and do it themselves. But what it illustrates is that the line between victim and victimizer is largely circumstantial. There was always some number of black men who invoked Trayvon Martin’s name simply because he was a black male, simply because it could have been them. “It could be me” is a fine starting place for confronting the evils of the world, but a really poor conclusion. If no broader theory of sympathy and humanism emerges beyond one’s mean particularism, then all we really are left with are tribalism and power.

Only tribalism and power can explain the theory put forth by Cosby’s defenders—that some 40 women have joined together in a wide-ranging conspiracy to bring a powerful black man down. Why this plot would target an aging entertainer well past his prime and not, say, the first black president is left unasked. We, too, are capable of fictions because, as it turns out, oppression confers no wisdom and is rarely self-improving. There is no virtue in being kicked in the face. The virtue is all in what you do after.

December 30, 2015

The Paranoid Style of American Policing

Paul Beaty / AP

When I was around 10 years old, my father confronted a young man who was said to be “crazy.” The young man was always too quick to want to fight. A foul in a game of 21 was an insult to his honor. A cross word was cause for a duel, and you never knew what that cross word might be. One day, the young man got into it with one of my older brother’s friends. The young man pulled a metal stake out of the ground (there was some work being done nearby) and began swinging it wildly in a threatening manner. My father, my mother, or my older brother—I don’t recall which—told the other boy to go inside of our house. My dad then came outside. I don’t really remember what my father said to the young man. Perhaps he said something like “Go home,” or maybe something like, “Son, it’s over.” I don’t really recall. But what I do recall is that my dad did not shoot and kill the young man.

That wasn’t the first time I’d seen my father confront the violence of young people without resorting to killing them. This was not remarkable. When you live in communities like ours—or perhaps any community—mediating violence between young people is part of being an adult. Sometimes the young people are involved in scary behavior—like threatening people with metal objects. And yet the notion that it is permissible, wise, moral, or advisable to kill such a person as a method of de-escalation, to kill because one was afraid, did not really exist among parents in my community.

The same could not be said for those who came from outside of the community.

This weekend, after a Chicago police officer killed her 19-year-old son Quintonio LeGrier, Janet Cooksey struggled to understand the mentality of the people she pays to keep her community safe:

“What happened to Tasers? Seven times my son was shot,” Cooksey said.

“The police are supposed to serve and protect us and yet they take the lives,” Cooksey said.

“Where do we get our help?” she asked.

LeGrier had struggled with mental illness. When LeGrier attempted to break down his father’s door, his father called the police, who apparently arrived to find the 19-year-old wielding a bat. Interpreting this as a lethal threat, one of the officers shot and killed LeGrier and somehow managed to shoot and kill one of his neighbors, Bettie Jones. Cooksey did not merely have a problem with how the police acted, but with the fact that the police were even called in the first place. “He should have called me,” Cooksey said of LeGrier’s father.

Instead, the father called the Chicago Police Department. Likely he called them because he invested them with some measure of legitimacy. This is understandable. In America, police officers are agents of the state and thus bound by the social contract in a way that criminals, and even random citizens, are not. Criminals and random citizens are not paid to protect other citizens. Police officers are. By that logic, one might surmise that the police would be better able to mediate conflicts than community members. In Chicago, this appears, very often, not to be the case.

It will not do to note that 99 percent of the time the police mediate conflicts without killing people anymore than it will do for a restaurant to note that 99 percent of the time rats don’t run through the dining room. Nor will it do to point out that most black citizens are killed by other black citizens, not police officers, anymore than it will do to point out that most American citizens are killed by other American citizens, not terrorists. If officers cannot be expected to act any better than ordinary citizens, why call them in the first place? Why invest them with any more power?

In America, we have decided that it is permissible, that it is wise, that it is moral for the police to de-escalate through killing.

Legitimacy is what is ultimately at stake here. When Cooksey says that her son’s father should not have called the police, when she says that they “are supposed to serve and protect us and yet they take the lives,” she is saying that police in Chicago are police in name only. This opinion is widely shared. Asked about the possibility of an investigation, Melvin Jones, the brother of Bettie Jones, could muster no confidence. “I already know how that will turn out,” he scoffed. “We all know how that will turn out.”

Indeed, we probably do. Two days after Jones and LeGrier were killed, a district attorney in Ohio declined to prosecute the two officers who drove up, and within two seconds of arriving, killed the 12-year-old Tamir Rice. No one should be surprised by this. In America, we have decided that it is permissible, that it is wise, that it is moral for the police to de-escalate through killing. A standard which would not have held for my father in West Baltimore, which did not hold for me in Harlem, is reserved for those who have the maximum power—the right to kill on behalf of the state. When police can not adhere to the standards of the neighborhood, of citizens, or of parents, what are they beyond a bigger gun and a sharper sword? By what right do they enforce their will, save force itself?

When policing is delegitimized, when it becomes an occupying force, the community suffers. The neighbor-on-neighbor violence in Chicago, and in black communities around the country, is not an optical illusion. Policing is (one) part of the solution to that violence. But if citizens don’t trust officers, then policing can’t actually work. And in Chicago, it is very hard to muster reasons for trust.

When Bettie Jones’s brother displays zero confidence in an investigation into the killing of his sister, he is not being cynical. He is shrewdly observing a government that executed a young man and sought to hide that fact from citizens. He is intelligently assessing a local government which, for two decades, ran a torture ring. What we have made of our police departments America, what we have ordered them to do, is a direct challenge to any usable definition of democracy. A state that allows its agents to kill, to beat, to tase, without any real sanction, has ceased to govern and has commenced to simply rule.

December 26, 2015

Star Wars and the Critical Benefit of Low Expectations

My old colleague Ross Douthat is mystified that Star Wars: The Forces Awakens has wowed nearly every single critic its come up against:

This film has a 95 percent “Fresh” rating from critics on Rotten Tomatoes. 95 percent. (That’s higher than the audience rating, right now, which is only 92 percent. The wisdom of crowds!) If you want to be kind to the movie, I think it deserves, at best, the 65-70 percent earned by the last two “Hunger Games” movies — and frankly those were a lot more original and interesting than anything in “The Force Awakens.”

But no: 95 percent. Not from audiences; from critics.

Over at Vox, David Roberts is right in sync with the idea that The Force Awakens is getting an easy ride. I think this assessment doesn’t spend enough time considering three very important phrases. Those phrases are: Episode I, Episode II and Episode III.

However one feels about The Force Awakens, it is—in fact—a film. The aims of the heroes are coherent and accessible. The acting is good. (I really liked Ridley and Boyega.) And the pacing is well-managed. I’m an old man, so I thought the film was too loud. And I thought the film overplayed certain things, that it should have underplayed—the critical scene where Kylo Ren solidifies his place with the Dark Side (for now, at least) is interminable.

But The Force Awakens is a film—something that the last three offerings from Lucas were not. Indeed, I walked out of the movie theater amazed that I now actually thought less of the prequels, then when I walked in. Everything—save special effects—is wrong the last three iterations of Star Wars. The plotting is indecipherable. The dialogue is painful. Otherwise good actors struggle under Lucas’s direction. Also, Jar-Jar Binks. (What? Ain’t no more.) That this horribleness was strapped to an incredible hype machine only made matters worse.

Now it’s true that Abrams didn’t invent much and that he borrowed quite a bit. But he understood what was good about the Star Wars universe, and what was not. He took that expertise and made something that critics, and fans, have been waiting on for over thirty years—a decent Star Wars film, and arguably the best Star Wars film since The Empire Strikes Back.

Ta-Nehisi Coates's Blog

- Ta-Nehisi Coates's profile

- 17210 followers