Ta-Nehisi Coates's Blog, page 10

February 6, 2015

The Foolish, Historically Illiterate, Incredible Response to Obama's Prayer Breakfast Speech

Wikimedia

Wikimedia People who wonder why the president does not talk more about race would do well to examine the recent blow-up over his speech at the National Prayer Breakfast. Inveighing against the barbarism of ISIS, the president pointed out that it would be foolish to blame Islam, at large, for its atrocities. To make this point he noted that using religion to brutalize other people is neither a Muslim invention, nor, in America, a foreign one:

Lest we get on our high horse and think this is unique to some other place, remember that during the Crusades and the Inquisition, people committed terrible deeds in the name of Christ,” Mr. Obama said. “In our home country, slavery and Jim Crow all too often was justified in the name of Christ.

The "all too often" could just as well be "almost always." There were a fair number of pretexts given for slavery and Jim Crow, but Christianity provided the moral justification. On the cusp of plunging his country into a war that would cost some 750,000 lives, Confederate Vice-President Alexander Stephens paused to offer some explanation. His justification was not secular:

The Confederacy was to be:

[T]he first government ever instituted upon the principles in strict conformity to nature, and the ordination of Providence, in furnishing the materials of human society ... With us, all of the white race, however high or low, rich or poor, are equal in the eye of the law. Not so with the negro. Subordination is his place. He, by nature, or by the curse against Canaan, is fitted for that condition which he occupies in our system. The architect, in the construction of buildings, lays the foundation with the proper material-the granite; then comes the brick or the marble. The substratum of our society is made of the material fitted by nature for it, and by experience we know that it is best, not only for the superior, but for the inferior race, that it should be so.

It is, indeed, in conformity with the ordinance of the Creator. It is not for us to inquire into the wisdom of His ordinances, or to question them. For His own purposes, He has made one race to differ from another, as He has made "one star to differ from another star in glory." The great objects of humanity are best attained when there is conformity to His laws and decrees, in the formation of governments as well as in all things else. Our confederacy is founded upon principles in strict conformity with these laws.

Stephens went on to argue that the "Christianization of the barbarous tribes of Africa" could only be accomplished through enslavement. And enslavement was not made possible through Robert's Rules of Order, but through a 250-year reign of mass torture, industrialized murder, and normalized rape—tactics which ISIS would find familiar. Its moral justification was not "because I said so," it was "Providence," "the curse against Canaan," "the Creator," "and Christianization." In just five years, 750,000 Americans died because of this peculiar mission of "Christianization." Many more died before, and many more died after. In his "Segregation Now" speech, George Wallace invokes God twenty-seven times, and calls the federal government opposing him "a system that is the very opposite of Christ."

Now, Christianity did not "cause" slavery, anymore than Christianity "caused" the Civil Rights movement. The interest in power is almost always accompanied by the need to sanctify that power. That is what the Muslims terrorists in ISIS are seeking to do today, and that is what Christian enslavers and Christian terrorists did for the lion's share of American history.

That this relatively mild, and correct, point cannot be made without the comments being dubbed, "the most offensive I’ve ever heard a president make in my lifetime,” by a former Virginia governor gives you some sense of the limited tolerance for any honest conversation around racism in our politics. And it gives you something much more. My colleague Jim Fallows recently wrote about the need to, at once, infantilize and deify our military. Perhaps related to that is the need to infantilize and deify our history. Pointing out that Americans have done, on their own soil, in the name of their own God, something similar to what ISIS is doing now, does not make ISIS any less barbaric, or any more correct. That is unless you view the entire discussion as a kind of religious one-up-man-ship, in which the goal is to prove that Christianity is "the awesomest."

Obama seemed to be going for something more—faith leavened by “some doubt.” If you are truly appalled by the brutality of ISIS, then a wise and essential step is understanding the lure of brutality, and recalling how easily your own society can be, and how often it has been, pulled over the brink.

This article was originally published at http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2015/02/the-foolish-historically-illiterate-incredible-response-to-obamas-prayer-breakfast-speech/385246/

February 3, 2015

The Broad, Inclusive Canvas of Comics

PeteParker/Marvel Wiki

PeteParker/Marvel Wiki I took a five-hour train ride this weekend and spent most of that time on a Matt Fraction binge. Fraction writes comics—big, beautiful awesome comics—including Uncanny X-Men, Hawkeye, The Immortal Ironfist, and many more of his own creation. I mostly confined myself to Fraction's run on The Invincible Ironman, specifically the Dark Reign arc wherein our hero, Tony Stark, attempts to erase whole swaths of his brain. Stark knows too much—specifically, he has in his brain a database of secret information on virtually every superhero on the planet. His enemies, with the help of the American government, are determined to extract that info, along with the secrets that power Iron Man's armor. And so Stark spends several issues trying to wipe his brain, the way one might format a disk.

The best part about all of this isn't watching Stark alternate running from enemies with deleting his mind, though that's pretty cool. It isn't the diminishing renditions of Iron Man armor he conceives, finishing with the old original model that looks like it was assembled from oil barrels and kitchen appliances. No, the best part of this adventure is Pepper Potts, Stark's assistant, his sometimes-love interest, and the eventual head of Stark Enterprises. Better people than me can expand on Potts' traditional role in the Iron Man comics, but in Fraction's rendition she has great texture and range. There's a scene where she has to rescue two other high-powered agents—Maria Hill and Black Widow—and for several panes the three discuss what it means that Hill and Widow are being rescued by Stark's "secretary."

There's more, but really you should just read the book. After finishing, I started thinking about the last casting news in the world of Marvel—Alexandra Shipp as Storm—and the fact that Hollywood can't bring itself around to cast someone who looks like the Kenyan woman Storm actually is. This isn't a matter of fanboy accuracy, but white supremacy. In another world, where Lupita Nyong'o's dark is unexceptional, where her speech on beauty isn't needed, this discussion wouldn't be necessary. In this world, the one where we can accept Nina Simone's music but not her face, it matters.

One reason why I still enjoy books, including comic books, is that there's still more room for a transgressive diversity. If Greg Pak wants to create an Amadeus Cho, he doesn't have to worry about whether America is ready for a Korean-American protagonist. Or rather, he doesn't have to put millions of dollars behind it. I don't know what that means to a young, Asian-American comic books fan. But when I was eight, the fact that Storm could exist—as she was, and in a way that I knew the rest of society did not accept—meant something. Outside of hip-hop, it was in comics that I most often found the aesthetics and wisdom of my world reflected. Monica Rambeau was my first Captain Marvel. James Rhodes was the first Iron Man I knew.

I don't think we should go overboard. Fraction's work with Potts aside, comics have their own issues—like, really big, awful gender issues. But one reason I'm always cautious about the assumption that everything is improved by turning it into a movie is that the range of possibility necessarily shrinks. I'd frankly be shocked if we ever see a Storm, in all her fullness and glory, in a film.

This article was originally published at http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2015/02/the-broad-inclusive-canvas-of-comics/385080/

The Broad, Inclusive Canvas Of Comics

PeteParker/Marvel Wiki

PeteParker/Marvel Wiki I took a five-hour train ride this weekend and spent most of that time on a Matt Fraction binge. Fraction writes comics—big, beautiful awesome comics—Uncanny X-Men, Hawkeye, The Immortal Ironfist, and many more of his own creation. I mostly confined myself to Fraction's run on The Invincible Ironman, specifically the Dark Reign arc wherein our hero, Tony Stark, attempts to erase whole swaths of his brain. Stark knows too much—specifically, he has in his brain a database of secret information on virtually every superhero on the planet. His enemies, with the help of the American government, are determined to extract that info, along with the secrets that power Iron Man's armor. And so Stark spends several issues trying to wipe his brain, the way one might format a disk.

The best part about all of this isn't watching Stark alternate running from enemies with deleting his mind, though that's pretty cool. It isn't the diminishing renditions of Iron Man armor he conceives, finishing with the old original model that looks like it was assembled from oil barrels and kitchen appliances. No, the best part of this adventure is Pepper Potts, Stark's assistant, his sometimes-love interest, and the eventual head of Stark Enterprises. Better people than me can expand on Potts' traditional role in the Iron Man comics, but in Fraction's rendition she has great texture and range. There's a scene where she has to rescue two other high-powered agents—Maria Hill and Black Widow—and for several panes the three discuss what it means that Hill and Widow are being rescued by Stark's "secretary."

There's more, but really you should just read the book. After finishing, I started thinking about the last casting news in the world of Marvel—Alexandra Shipp as Storm—and the fact that Hollywood can't bring itself around to cast someone who looks like the Kenyan woman Storm actually is. This isn't a matter of fanboy accuracy, but white supremacy. In another world, where Lupita Nyong'o's dark is unexceptional, where her speech on beauty isn't needed, this discussion wouldn't be necessary. In this world, the one where we can accept Nina Simone's music but not her face, it matters.

One reason why I still enjoy books, including comic books, is that there's still more room for a transgressive diversity. If Greg Pak wants to create an Amadeus Cho, he doesn't have to worry about whether America is ready for a Korean-American protagonist. Or rather, he doesn't have to put millions of dollars behind it. I don't know what that means to a young Asian-American comic books fan. But when I was eight, the fact that Storm could exist—as she was, and in a way that I knew the rest of society did not accept—meant something. Outside of hip-hop, it was in comics that I most often found the aesthetics and wisdom of my world reflected. Monica Rambeau was my first Captain Marvel. James Rhodes was the first Iron Man I knew.

I don't think we should go overboard. Fraction's work with Potts aside, comics have their own issues—like, really big awful gender issues. But one reason I'm always cautious about the assumption that everything is improved by turning it into a movie is that the range of possibility necessarily shrinks. I'd frankly be shocked if we ever see a Storm, in all her fullness and glory, in a film.

This article was originally published at http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2015/02/the-broad-inclusive-canvas-of-comics/385080/

February 2, 2015

Andrew Sullivan and the Importance of Self-Criticism

Geoff Livingston/Flickr

Geoff Livingston/Flickr I don't really have much big-picture analysis in the wake of Andrew Sullivan's departure from blogging. My reaction is strictly personal. I've spent the majority of my career as a print journalist. In 2008, when I first started blogging, I had two models in mind—Matthew Yglesias and Andrew Sullivan, and I only knew about Matt because of Andrew. I started reading Andrew during the run-up to the Iraq War and thus bore witness to one of the most amazing real-time about-faces in recent memory. But it was a sincere about-face and it taught me something about writing, and particularly writing on the Internet, which guides me even today—namely, that error is an essential part of any real intellectual pursuit.

Back when I started blogging, there was an annoying premium on "public smartness" and "being right" among pundits, journalists, and writers. Likely, there is still one today. The need to be publicly smart and constantly right originates both in the writer's ego and in the expectation of incurious readers. The writer gets the psychic reward of praise—"Such and such is really smart" or "Such and such was 'right' on Libya." And the incurious reader gets to believe that there is some order in the world, that there is a stable of learned (mostly) men who will decipher the words of God for them. The incurious readers is not so much looking for writers, as prophets.

And Andrew has never been a prophet, so much as a joyous heretic. Andrew taught me that you do not have to pretend to be smarter than you are. And when you have made the error of pretending to be smarter, or when you simply have been wrong, you can say so and you can say it straight—without self-apology, without self-justifying garnish, without "if I have offended." And there is a large body of deeply curious readers who accept this, who want this, who do not so much expect you to be right, as they expect you to be honest. When I read Andrew, I generally thought he was dedicated to the work of being honest. I did not think he was always honest. I don't think anyone can be. But I thought he held "honesty" as a standard—something can't be said of the large number of charlatans in this business.

Honesty demands not just that you accept your errors, but that your errors are integral to developing a rigorous sense of study. I have found this to be true in, well, just about everything in life. But it was from Andrew that I learned to apply it in this particular form of writing. I am indebted to him. And I will miss him—no matter how much I think he's wrong, no matter the future of blogging.

This article was originally published at http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2015/02/andrew-sullivan-and-the-importance-of-error/385071/

Andrew Sullivan And The Importance Of Error

I don't really have much big picture analysis in the wake of Andrew Sullivan's departure from blogging. My reaction is strictly personal. I've spent the majority of my career as a print journalist. In 2008, when I first started blogging, I had two models in mind--Matthew Yglesias and Andrew Sullivan, and I only knew about Matt because of Andrew. I started reading Andrew during the run-up to the Iraq War and thus bore witness to one of the most amazing real-time about-faces in recent memory. But it was a sincere about-face and it taught me something about writing, and particularly writing on the internet, which guides me even today--namely, that error is an essential part of any real intellectual pursuit.

Back when I started blogging, there was an annoying premium on "public smartness" and "being right" among pundits, journalists and writers. Likely, there is still one today. The need to be publicly smart and constantly right originates both in the writer's ego and in the expectation of incurious readers. The writer gets the psychic reward of praise--"Such and such is really smart" or "Such and such was 'right' on Libya." And the incurious reader gets to believe that there is some order in the world, that there is a stable of learned (mostly) men who will decipher the words of God for them. The incurious readers is not so much looking for writers, as prophets.

And Andrew has never been a prophet, so much as a joyous heretic. Andrew taught me that you do not have to pretend to be smarter than you are. And when you have made the error of pretending to be smarter, or when you simply have been wrong, you can say so and you can say it straight--without self-apology, without self-justifying garnish, without "if I have offended." And there is a large body of deeply curious readers who accept this, who want this, who do not so much expect you to be right, as they expect you to be honest. When I read Andrew, I generally thought he was dedicated to the work of being honest. I did not think he was always honest. I don't think anyone can be. But I thought he held "honesty" as a standard--something can't be said of the large number of charlatans in this business.

Honesty demands not just that you accept your errors, but that your errors are integral to developing a rigorous sense of study. I have found this to be true in, well, just about everything in life. But it was from Andrew that I learned to apply it in this particular form of writing. I am indebted to him. And I will miss him--not matter how much I think he's wrong, no matter the future of blogging.

This article was originally published at http://www.theatlantic.com/personal/archive/2015/02/andrew-sullivan-and-the-importance-of-error/385071/

January 27, 2015

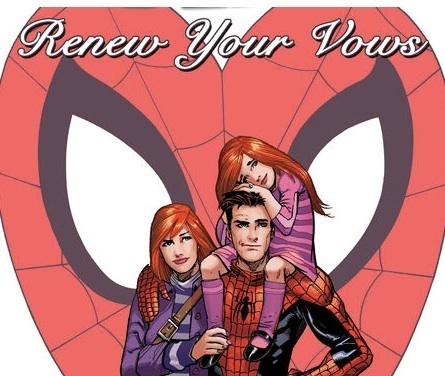

Spider-Man in Love

Marvel

MarvelA few weeks ago Marvel Comics began teasing out covers for its latest intra-title event, Secret War, which is set to kick off this summer. Among the covers attracting the most attention is this one drawn by Adam Kubert, which hints at the possible restoration of the marriage between Peter Parker and Mary Jane Watson. The union, which lasted 20 years in real time, was written out of the Spiderman books in 2007 during the "One More Day" arc, prompting great outcry from Spider-fans and near-universal panning from critics.

The possibility of restoration has been met with the exact opposite reaction. With some disappointment, I count myself among those rooting for a renewal. I like to think of myself as rather unsentimental. The one thing I know about the world is that it ends in cold death, and thus badly. But the upshot of that is not cynicism, but a deep belief that what happens in between the brightness of birth and the darkness of death really does matter.

I was eleven years old when Peter Parker and Mary Jane Watson were married. It's worth noting that the initial marriage was attended with much outrage. I did not know this and I would not have cared. Even then, barely pubescent, I was a romantic. I mean this as something beyond chocolates and roses: I mean that I was deeply interested in the nature and depths of love. I was born in 1975, when a great many things were in question. I was the sixth of seven children born to one man and four different women, and the fact of sex, sex outside of marriage, was all around me. There were no stories featuring the stork. I was the product of a woman who looked at a man, and thought not of happily ever after but that he would make a great father. Good call.

My mother and father never gave me "The Talk." "The Talk" was my entire childhood. From the time I remember them talking, I remembering them, my mother especially, talking about sex. It makes me laugh now but I recall her telling me, when my time came, not to just "jump up and down on a woman." I might have been ten when she first said that. My family was all kinds of inappropriate—hood hippies—and yet we were correct. I say this because I knew, from a very early age, that there was love in my house, imperfect love, love that was built, decided upon, as opposed to magicked into existence.

That was how Peter loved Mary Jane. They were not destined to be. She was not his Lois Lane. His Lois Lane—Gwen Stacy—was murdered for the crime of getting too close to him, and the guilt of this always weighed on him. Whatever. While the world was fooled, Mary Jane Watson knew Peter Parker was Spider-Man. And she didn't wait around for him to figure it all out. She was, very clearly, sexual. She dated whomever she wanted. She dated dudes who were richer than Parker. She dated dudes who were better looking than Parker. She dated Parker's best friends. She actually spurned Parker's first proposal—and then his second too, before reconsidering. Mary Jane Watson was the kind of girl you did not bring home to mother—unless you had a mother like mine.

I have never quite understood the dictum that "you can't turn a hoe into a housewife." Perhaps that is because, if pressed, I would always take the former over the latter. Perhaps it is because I don't desire to turn anyone into anything. But more likely it's because I wasn't really raised that way. Nothing else explained my tangled family Women obviously had sex. Women obviously enjoyed sex. Prince made my mother feel the exact same way that Lisa Lisa made me feel. Michael Jackson (pre-nose job) did the same for my sister.

I liked to believe that Peter Parker, ultimately, wasn't raised that way either. He did not ultimately end up with the blonde whom he was made for. And if he ended up with a beautiful woman, he did not end up with an ornamental one. His marriage was a rejection of the macho ideal of romance—which reigns even among nerds—and it mirrored and confirmed my own budding sense of what love was at a very young age.

I wouldn't argue that the Parker-Watson marriage was always well written and drawn. The "super-model" angle felt unnecessary, as did some of the porno-lite art. (It's good to see Kubert, here, depicting Watson the way women actually tend to look.) I won't defend the '90s, which were not a good period for the writing in the Spider-Man books. But in a genre aimed at young males, it is very hard for me to come up with a more mature, and I would say healthy, vision of what a marriage should look like. Mary Jane Watson was not looking to be saved. If anything, she wanted Peter Parker to stop saving people. She did not need Peter Parker. She was not fashioned especially to be his wife. She was a human and seemed as though she would have been with Peter Parker, or without him.

I never read One More Day. I generally hated the notion that you couldn't have a grown-up superhero, and I did not hate it just because I was grown-up: I would have hated it when I was 12. The fact of it was I idolized grown-ups. One More Day felt like an erasure of what had been one of its more unintentionally bold endeavors—the attempt to allow a superhero to grow up, to be more than Peter Pan, to confront the tragic world as it was, to imagine life beyond what should have been.

This article was originally published at http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2015/01/spider-man-in-love/384860/

January 14, 2015

I Might Be Charlie

I came to Paris, last week, with a fairly well-defined mission. Halfway through the week, events overtook me. On Thursday, I was determined to ignore the terrorist attack and plug away on my own projects. But by Saturday, I was in a room with some Paris friends discussing the fallout, and on Sunday I was at a brunch with those same Parisians and then off to la manifestation. Since then I've done almost nothing but talk to the people who call this city—and it's banlieues—home. I have so much to tell you, but it's raw and unseasoned. I need some time to marinate and then cook.

Immediately after the attack, as is the case with any grand political event, a great number of American commenters leaped in to offer their opinion in various outlets. Some of these commenters were being knowledgeable. Some of them were just being smart on the Internet. I have always used this forum as a tool for my own public education, but something about last week left me feeling like I shouldn't be talking. Perhaps it was because the people who were saying Je suis Charlie and the ones who, in more hushed tones, were saying Je ne suis pas Charlie were not my people, and this was neither my country nor my home. Perhaps it was that these people were my neighbors in mourning and thus I felt a little care should be taken.

I am here for a little while longer. My hope is that by the time I leave I will have graduated from "Internet smart" to the ranks of the "sort of knowledgeable." I'm talking to everyone I can. I'm reading as much as I can. I'm endangering previously agreed-upon deadlines. History is happening around me and I am not equipped to understand. I am mostly unequipped because I only have the barest understanding of the emotional aspects of patriotism. I have spent the past week asking people what, precisely, they believe themselves to be defending. The answers have been fascinating. Just yesterday someone told me that this was really about "the dream of Europe" itself. I have more of an idea of what that means today than I did last week. It can't be forgotten that the deadliest conflict in world history was fought here, and it was fought well within living memory, and this came on the heels of centuries of bloodletting—much of it, allegedly (and that word deserves emphasis), over religion.

I've tried to go back to the history. I'm thinking of Tony Judt and "national forgetting" a lot. I'm thinking of Antony Beevor. I'm thinking of C.V. Wedgwood. I'm taking long walks through the city listening (via Audible) to Alistair Horne's A Savage War Of Peace: Algeria 1954-1962. I have always started from the premise that one should be skeptical of comparing the problems of home with the problems of a country that one does not know. And yet here is Horne describing the attitudes of the pied noir (colonizer of Algeria, often—but not exclusively—French) toward the native Algerians:

Equally a host of preconceived inherited notions about the Algerian were accepted uncritically, without examining either their veracity or causation: he was incorrigibly idle and incompetent; he only understood force; he was an innate criminal, and an instinctive rapist. Sexually based prejudices and fears ran deep, akin to those elsewhere of white city-dwellers surrounded by preponderant and ever-growing Negro populations: “They can see our women, we can’t see theirs”; the Arab had a plurality of wives, and therefore was possibly more virile (an intolerable thought to the “Mediterranean-and-a-half”); and with the demographic explosion spawned by his potency, he was threatening to swamp the European by sheer weight of numbers.

The pied noir would habitually tutoyer any Muslim—a form of speech reserved for intimates, domestics or animals—and was outraged were it ever suggested that this might be a manifestation of racism. Commenting on this, Pierre Nora (admittedly a Frenchman often unduly harsh in his criticism of the pieds noirs), adds an illustration of a judge asking in court:

“Are there any other witnesses?”

“Yes, five; two men and three Arabs.”

Or again: “It was an Arab, but dressed like a person.…”

Horne quotes the French writer Jules Roy, who is told that the native Algerians "don't live like we do" and that "their happiness was elsewhere, rather, if you please, like the happiness of cattle." This racism, like all racism, was not a bout of madness, but an actual tool which made Roy's lifestyle possible:

I was glad to believe it. And from that moment on their condition could not disturb me. Who suffers seeing oxen sleep on straw or eating grass?

The Jewish peoples of Algeria also predated the pied noir, tracing their roots back to the Spanish expulsions of the 16th century and even further. Horne says that Algerian Jews "tended to find themselves being caught between two fires: between the European and the Muslim world." The French effectively turned Algerian Jews into a kind of buffer class, granting them citizenship under the Crémieux Decree in 1870, and denying it to Berbers and Arabs. This award was tenuous—70 years later it was rescinded by Pétain. "Jewish teachers and children alike were summarily flung out of European schools," writes Horne. "The whole community was menaced with deportation to Nazi camps."

And yet...

...during all this time (so several Algerian Jews averred to the author), there was barely a breath of anti-Semitism from any Muslim quarter. By the 1950s the Algerian Jews were tugged in several directions; the least privileged tended still to identify themselves with the Muslims rather than the pieds noirs, and many were members of the Communist Party, while the wealthiest had developed distinctly Parisian orientations. Perhaps typical of the latter was Marcel Belaiche, who had inherited a large property fortune from his father; politically, however, he leaned strongly towards the liberal camps of both Chevallier and Ferhat Abbas, and away from the Borgeauds and Schiaffinos. After 1954 a significant proportion of the Jewish intellectual and professional classes was to side with the F.L.N.

I don't yet know how all of this connects to the events we are seeing today. But I proceed from the working theory that all nations like to begin the story with the chapter that most advantages them and the job of the writer is to resist this instinct. And I proceed from the working theory that the story of black people in America, is an excellent launchpad for a larger investigation into the limits of democracy and compassion throughout the West. It is not the sole launchpad, and the investigation must, ultimately, go beyond the simple of drawing of parallels.

But it is a start--the only start I have. I don't have much time here. And this is a very new space for me. I have studied black people all of my life. I have only studied the Francophone world for three years. I am, as always, very afraid.

More soon.

This article was originally published at http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2015/01/i-might-be-charlie-hebdo-paris/384501/

January 5, 2015

Why the NYPD Turned Its Back on the City

On Sunday, a relatively large group of New York police officers, sworn to protect and serve the public, turned their back on the public's elected executive, Mayor Bill de Blasio:

The show of disrespect came outside the funeral home where Officer Wenjian Liu was remembered as an incarnation of the American dream: a man who had immigrated at age 12 and devoted himself to helping others in his adopted country. The gesture, among officers watching the mayor's speech on a screen, added to tensions between the mayor and rank-and-file police even as he sought to quiet them.

This particular protest came after Commissioner William Bratton asked them not to stage a repeat of Officer Rafael Ramos's funeral. This request included the telling caveat, "I issue no mandates, and I make no threats of discipline, but I remind you that when you don the uniform of this department, you are bound by the tradition, honor and decency that go with it."

It's not clear that Bratton could (or should) do much of anything to stop his officers from protesting. But whatever Bratton's sense of honor and decency, it clearly isn't shared by the officers working under him, and it's unlikely that his appeal swayed anyone.

Those who are demoralized by these protests would do well to read James Fallows's cover story on the American military this month. The same cloak of puffed grandeur and bombast that surrounds our army can be detected in our police. Jim is describing a society that has taken its hands off the wheel. Give us safety now (real or imagined), goes the agreement, and we won't ask about what comes later. Until some critical mass of Americans decides that police cannot, all at once, wield the lethal power of gods and the meager responsibilities of mortals, change is unlikely.

And it always was. If the public appetite for police reform can be soured by the mad acts of a man living on the edge of society, then the appetite was probably never really there to begin with. And the police, or at least their representatives, know this. In this piece, by Wesley Lowery, there are several amazing moments where police complain about things Barack Obama and Eric Holder have not actually said. There simply is no level of critique they would find tolerable. Why take criticism when you don't actually have to? Better to remind the public that you are the only thing standing between them and the barbarians at the gate:

“We might be reaching a tipping point with the mind-set of officers, who are beginning to wonder if the risks they take to keep communities safe are even worth it anymore,” Milwaukee County Sheriff David Clarke said. “In New York and other places, we’re seeing a natural recoil from law enforcement officers who don’t feel like certain people who need to have their backs have their backs.”

Here's Radley Balko quantifying those "risks" police officers face:

Policing has been getting safer for 20 years. In terms of raw number of deaths, 2013 was the safest year for cops since World War II. If we look at the rate of deaths, 2013 was the safest year for police in well over a century .... You’re more likely to be murdered simply by living in about half of the largest cities in America than you are while working as a police officer.

Nearly half of those deaths are from automobile accidents. Balko is somewhat frustrated that despite the empirical facts around policing, nothing seems to penetrate the narrative of police living under constant threat. Why? Is it that most people are just basically ignorant of the information? Is it that most people just believe, uncritically, what police officers tell them?

Or is there something more? Forgive me. I have not yet fully worked this all out. But Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn describes the prisoners headed to the Soviet Gulag as waves flowing underground. These waves "provided sewage disposal for the life flowering on the surface." I understand this to mean that the gulag was not just mindless evil—was not just incomprehensible insanity—but served some sort of productive and knowable purpose.

Could it be that believing our police to be constantly under fire is not mysterious—that it serves some productive function, that society actually derives something from its peace officers engaged in forever war? And can we say that the function of the war here at home is not simply a response to violent crime (which has plunged) but to some other need? And knowing that identity is not simply defined by what we are, but what we are not, can it be that our police help give us identity, by branding one class of people as miscreants, outsiders, and thugs, and thus establishing some other class as upstanding, as citizens, as Americans? Does the feeling of being besieged serve some actual purpose?

I am not sure this is all correct. But if the direction is right, then it becomes possible to understand the NYPD's protest (and the toothless admonitions of the commissioner) not as mindless petulance, but as something systemic, as a natural outgrowth of our needs.

This article was originally published at http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2015/01/why-the-nypd-turned-its-back-on-the-city/384196/

December 22, 2014

Blue Lives Matter

The reactions to the murders of two New York police officers this weekend have been mostly uniform in their outrage. There was the predictable gamesmanship exhibited in some quarters, but all agree that the killing of Wenjian Liu and Rafael Ramos merits particular censure. This is understandable. The killing of police officers is not only the destruction of life but an attack on democracy itself. We do not live in a military dictatorship, and police officers are not the representatives of an autarch, nor the enforcers of law handed down by decree. The police are representatives of a state that derives its powers from the people. Thus the strong reaction we have seen to Saturday's murders is wholly expected and entirely appropriate.

For activists and protesters radicalized by the killings of Michael Brown and Eric Garner, this weekend's killing may seem to pose a great obstacle. In fact, it merely points to the monumental task in front of them. Garner's death, particularly, seemed to offer some hope. But the very fact that this opening originated in the most extreme case—the on-camera choking of a man for a minor offense—points to the shaky ground on which such hope took root. It was only a matter of time before some criminal shot a police officer in New York. If that's all it takes to turn Americans away from police reform, the efforts were likely doomed from the start.

The idea of "police reform" obscures the task. Whatever one thinks of the past half-century of criminal-justice policy, it was not imposed on Americans by a repressive minority. The abuses that have followed from these policies—the sprawling carceral state, the random detention of black people, the torture of suspects—are, at the very least, byproducts of democratic will. Likely they are much more. It is often said that it is difficult to indict and convict police officers who abuse their power. It is comforting to think of these acquittals and non-indictments as contrary to American values. But it is just as likely that Americans hesitate to punish police officers because they see them as upholding American values. The three most trusted institutions in America are the military, small business, and the police.

To challenge the police is to challenge the American people, and the problem with the police is not that they are fascist pigs but that we are majoritarian pigs. When the police are brutalized by people, we are outraged because we are brutalized. By the same turn, when the police brutalize people, we are forgiving because ultimately we are really just forgiving ourselves. We seek to wield power, but not responsibility. The manifestation of this desire is broad. Former Mayor Rudy Giuliani responded to the killing of Michael Brown by labeling it a "significant exception" and wondering why weren't talking about "black on black crime." Giuliani was not out on a limb. The charge of insufficient outrage over "black on black crime" has been endorsed, at varying points, by everyone from the NAACP to Washington Post columnist Eugene Robinson to Giuliani's archenemy Al Sharpton.

Implicit in this notion is that outrage over killings by the police should not be any greater than killings by ordinary criminals. But when it comes to outrage over killings of the police, the standard is different. Ismaaiyl Brinsley began his rampage by shooting his girlfriend—an act of both black-on-black crime and domestic violence. On Saturday, Officers Liu and Ramos were almost certainly joined in death by some tragic number of black people who were shot down by their neighbors in the street. The killings of Officers Liu and Ramos prompt national comment. The killings of black civilians do not. When it is convenient to award qualitative value to murder, we do so. When it isn't, we do not. We are outraged by violence done to police, because it violence done to all of us as a society. In the same measure, we look away from violence done by the police, because the police are not the true agents of the violence. We are.

We are the ones who designed the criminogenic ghettos. We are the ones who barred black people from leaving those ghettos. We are the ones who treat black men without criminal records as though they are white men with criminal records. We are the ones who send black girls to juvenile detention homes for fighting in school. We are the masters of the American gulag, a penal system "so vast," writes sociologist Bruce Western, "as to draw entire demographic groups into the web." And we are the ones who send in police to make sure it all goes according to plan.

When defenders of the police say that cops do the work ordinary citizens are afraid to, they are correct. The criminal-justice system has been the most consistent tool for making American will manifest in black communities. I suspect, we would rather the film of Eric Garner's killing not exist. Then we might comfort ourselves with the kind of vague unknowables that dogged the killing of Michael Brown. ("Did he have his hands up? Was he surrendering? Was he charging?") Garner choked to death repeating "I can't breathe" trapped us. But now, through a merciless act of lethal violence, our escape route has been restored. This overstates things. To the extent that this weekend's murders obscure the legacy of Eric Garner, it will not be due to the failure of protests, nor even chance. The citizen who needs to look away, generally finds a reason.

I wonder if there is some price to this looking away. When the democratically elected mayor of my city arrived at the hospital, the police officers who presumably serve at the public's leisure turned away in a display that should chill the blood of any citizen. The police are not the only embodiment of democratic society. And one does not have to work hard to imagine a future when the agents of our will, the agents whom we created, are in fact our masters. On that day one can expect that the tactics intended for the ghettos shall be employed in other terrains.

This article was originally published at http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2014/12/blue-lives-matter-nypd-shooting/383977/

December 9, 2014

The New Republic: An Appreciation

"Here's at you!"

—Philip Sheridan

Last week, Franlin Foer resigned his editorship of The New Republic. A deep, if not broad, mourning immediately commenced as a number of influential writers lamented what occurred to them as the passing of a great American institution. The mourners have something of a case. TNR had a hand in the careers of an outsized number of prominent narrative and opinion journalists. I have never quite been able to judge the effect of literature or journalism on policy, but I know that in my field, if you had dreams of having a career, you had to contend with TNR. My first editor at The Atlantic came from TNR, as did the editor of the entire magazine. More than any other writer, TNR alum Andrew Sullivan taught me how to think publicly. More than any other opinion writer, Hendrik Hertzberg taught we how to write with "thickness," as I once heard him say. A semester in my nonfiction class is never quite complete without this piece by Michael Kinsley. TNR's legacy is so significant that I could never have avoided being drawn into the magazine's orbit. Even if I had wanted to.

Earlier this year, Foer edited an anthology of TNR writings titled Insurrections of the Mind, commemorating the magazine's 100-year history. "This book hasn't been compiled in the name of definitiveness," Foer wrote. "It was put together in the spirit of the magazine that it anthologizes: it is an argument about what matters." There is only one essay in Insurrections that takes race as its subject. The volume includes only one black writer and only two writers of color. This is not an oversight. Nor does it mean that Foer is bad human. On the contrary, if one were to attempt capture the "spirit" of TNR, it would be impossible to avoid the conclusion that black lives don't matter much at all.

That explains why the family rows at TNR's virtual funeral look like the "Whites Only" section of a Jim Crow-era movie-house. For most its modern history, TNR has been an entirely white publication, which published stories confirming white people's worst instincts. During the culture wars of the '80s and '90s, TNR regarded black people with an attitude ranging from removed disregard to blatant bigotry. When people discuss TNR's racism, Andrew Sullivan's publication of excerpts from Charles Murray's book The Bell Curve (and a series of dissents) gets the most attention. But this fuels the lie that one infamous issue stands apart. In fact, the Bell Curve episode is remarkable for how well it fits with the rest of TNR's history.

The personal attitude of TNR's longtime owner, the bigoted Martin Peretz, should be mentioned here. Peretz's dossier of racist hits (mostly at the expense of blacks and Arabs) is shameful, and one does not have to look hard to find evidence of it in Peretz's writing or in the sensibility of the magazine during his ownership. In 1984, long before Sullivan was tapped to helm TNR, Charles Murray was dubbing affirmative action a form of "new racism" that targeted white people.

Two years later, Washington Post writer Richard Cohen was roundly rebuked for advocating that D.C. jewelry stores discriminate against young black men—but not by TNR. The magazine took the opportunity to convene a panel to "reflect briefly" on whether it was moral for merchants to bar black men from their stores. ("Expecting a jewelry store owner to risk his life in the service of color-blind justice is expecting too much," the magazine concluded.)

TNR made a habit of "reflecting briefly" on matters that were life and death to black people but were mostly abstract thought experiments to the magazine's editors. Before, during, and after Sullivan's tenure, the magazine seemed to believe that the kind of racism that mattered most was best evidenced in the evils of Afrocentrism, the excesses of multiculturalism, and the machinations of Jesse Jackson. It's true that TNR's staff roundly objected to excerpting The Bell Curve, but I was never quite sure why. Sullivan was simply exposing the dark premise that lay beneath much of the magazine's coverage of America's ancient dilemma.

What else to make of the article that made Stephen Glass's career possible, "Taxi Cabs and the Meaning of Work"? The piece asserted that black people in D.C. were distinctly lacking in the work ethic best evidenced by immigrant cab drivers. A surrealist comedy, Glass's piece revels in the alleged exploits of a mythical Asian-American avenger—Kae Bang—who wreaks havoc on black criminals who'd rather rob taxi drivers than work. The article concludes with Glass, in the cab, while its driver is robbed by a black man. It was all lies.

What else to make of TNR sending Ruth Shalit to evaluate affirmative action at The Washington Post in 1995? "She cast Post writer Kevin Merida as some kind of poster boy for affirmative action when in fact he had risen in the business for reasons far more legitimate than her own," David Carr wrote in 1999. Shalit's piece wasn't all lies. But it wasn't all true either. Shortly after the article was published, she was revealed to be a serial plagiarist.

TNR might have been helped by having more—or merely any—black people on its staff. I spent the weekend calling around and talking to people who worked in the offices over the years. From what I can tell, in that period, TNR had a total of two black people on staff as writers or editors. When I asked former employees whether they ever looked around and wondered why the newsroom was so white, the answers ranged from "not really" to "not often enough." This is understandable. Prioritizing diversity would have been asking TNR to not be TNR. One person recalled a meeting at the magazine's offices when the idea of excerpting The Bell Curve was first pitched. Charles Murray came to this meeting to present his findings. The meeting was very contentious. I asked if there were any black people in the room this meeting. The person could not recall.

I always knew I could never work at TNR. In the latter portion of the magazine's heyday, in the mid-'90s, I was at Howard University with aspirations toward writing. Howard has a way of inculcating its students with a sense of mission. If you are going into writing, you understand that you are not a free agent, but the bearer of heritage walking in the steps of Hurston, Morrison, Baldwin, Wright, and Ellison. None of these writers appear in Insurrections of the Mind. Howard University taught me to be unsurprised by this. It also taught me that writing was war, and I knew, even then, that TNR represented much of what I was at war with. I knew that TNR's much celebrated "heterodoxy" was built on a strain of erudite neo-Dixiecratism. When The Bell Curve excerpt was published, one of my professors handed out the issue to every interested student. This was not a compliment. This was knowing your enemy.

TNR did not come to racism out of evil. Very few people ever do. Many of the white people working for the magazine were very young and very smart. This is always a dangerous combination. It must have been that much more dangerous given that their boss was a racist. (Though I am told he had many black friends and protégés.) Peretz was not always a regular presence in the office. This allowed TNR's saner staff to regard him as the crazy uncle who says racist shit at Thanksgiving. But Peretz was not a crazy uncle—he was the wealthy benefactor of an influential magazine that published ideas that damaged black people.

A writer for TNR told me how, in the mid-'90s, Peretz would come down to the office from Cambridge and lobby young writers to write what turned out to be the fictional "Taxi Cabs and the Meaning of Work." The writer told me that the young interns and fact-checkers would squirm in their seats. But no one took a stand. And perhaps it is too much to expect writers in their mid 20s, with editors in their late 20s, to say to Peretz, "Please stop shopping this racist bullshit." But the task was made infinitely easier by a monochrome staff that could view Peretz's racism as an abstraction, and not something that directly injured their families.

Things got better after Peretz was dislodged. The retrograde politics were gone, but the "Whites Only" sign remained. I've been told that Foer was greatly pained by Peretz's racism. I believe this. White people are often sincerely and greatly pained by racism, but rarely are they pained enough. That is not true because they are white, but because they are human. I know this, too well. Still, as of last week there were still no black writers on TNR's staff, and only one on its masthead. Magazines, in general, have an awful record on diversity. But if TNR's influence and importance was as outsized as its advocates claim, then the import of its racist legacy is outsized in the same measure. One cannot sincerely partake in heritage à la carte.

In this sense it is unfortunate to see anonymous staffers accusing TNR's owner Chris Hughes of trying to create "another BuzzFeed." If that is truly Hughes's ambition, then—in at least one important way—he will have created a publication significantly more moral than anything any recent TNR editor ever has. No publication has more aggressively dealt with diversity than BuzzFeed. And not unrelated to this diversity has been a stellar range of storytelling and analysis, that could rival—if not best—the journalism in the latest iteration of TNR.

No one who works in magazines is happy to hear about writers and editors losing their jobs—even when those people have the enviable luxury of walking out on principle. And when I think of TNR's history, when I flip through Insurrections, when I examine the magazines archives, I am not so much angry as I am sad. There really was so much fine writing in its pages. But all my life I have had to take lessons from people who, in some profound way, can not see me. TNR billed itself as the magazine for iconoclasts. But its iconoclasm ended exactly where everyone else's does—at 110th Street. Worse, TNR encouraged incuriosity about what lay beyond the barrier. It told its readers that my world was welfare cheats, affirmative-action babies, and Jesse Jackson. And that white people—or any people—would be urged to such ignorance by their Harvard-bred intellectual leadership is deeply sad. The in-flight magazine of Air-Force One should have been better. Perhaps it still can be.

This article was originally published at http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2014/12/the-new-republic-an-appreciation/383561/

Ta-Nehisi Coates's Blog

- Ta-Nehisi Coates's profile

- 17137 followers