Ta-Nehisi Coates's Blog, page 3

December 20, 2016

'The Filter ... Is Powerful': Obama on Race, Media, and What It Took to Win

In “My President Was Black,” The Atlantic’s Ta-Nehisi Coates examined Barack Obama’s tenure in office, and his legacy. The story was built, in part, around a series of conversations he had with the president. This is a transcript of the first of those three encounters, which took place on September 27, 2016. Valerie Jarrett, the senior adviser to the president, was also present. You can find responses to the story, and to these conversations, here.

Barack Obama: All right, where do you want to start.

Ta-Nehisi Coates: You know, I was thinking about something today that I heard, and I wanted to see if you could confirm it, and if you could, whether you could talk about it. I was told that the night of the inauguration it was a huge, huge party here. Is that correct?

Obama: [Chuckles] That would be correct.

Valerie Jarrett: The second inauguration …

Obama: You’re talking about the second inauguration?

Coates: Was it the second? Celebrities, maybe Stevie Wonder and Usher?

Obama: First inauguration we had—you know, this is a good example of when you first arrive, you don’t know what you’re supposed to do. So there are all these state balls that take place, and we sort of assumed—we were told—well, you should go to all the balls. So …

Coates: Did you try that? Did you try to go to all of them?

Obama: We went to all of them. And you do a dance at each one.

Coates: Fifty?

Obama: No, no, not every state has one, but we went to 10 or 12. And by the time we were done, it was like 1 o’clock, so we had Wynton Marsalis here playing, and people had been hanging out, but by the time we got back Michelle’s feet were all hurting and swollen up, and I was exhausted, and we hung out here probably for half an hour, and went to bed. Now, the second inauguration, we had it a little more figured out. So we did, like, three balls and then got back here and had a DJ and, yeah, Usher and Stevie.

Coates: How late did you go?

Obama: Three-thirty? Four o’clock?

Coates: Was the second one more joyous for you—

Obama: Yes.

Coates: It’s one thing you’re the first black president, but it’s like “Wow, this really—”

Obama: Yeah. I think the way to think about it is the first inauguration is like your wedding in the sense that it is a joyous moment and occasion, but you’re so busy and kind of stressed making sure that Aunt Such-and-Such and Uncle So-and-So and cousins are getting tickets that it ends up going by without you even really knowing what’s happening. The second one you could savor. But partly, as you indicated, for political reasons as well. Because we had gone through four of the toughest years this country has gone through since the ’30s. And to be able to win a majority of the vote the second time indicated that we had worked with a broad cross section of the country and they trusted what we were trying to do. And it wasn’t just a singular feel-good moment; it was an affirmation that people thought we had done a good job.

Coates: I think for those of us—and I certainly threw myself in this camp—I was telling Valerie the other day, the idea of a black president was a joke, in every black stand-up comic routine everywhere—

Obama: Right. A friend of mine gave me Head of State—remember [Chris Rock] and Bernie Mac?—when we were still running. Said, “Man, you got to see Head of State.” [Laughter]

Coates: Yeah, this was like a laugh-fest. But I think one of the things that did distinguish you was the ability to see it and to have the vision that, yes, this could happen, and then to have it again. I’m speaking specifically in terms of race … There were those of us who said, “It’s no way.” And to see it the first and second time must have really reaffirmed a lot of what you thought.

Obama: As I said, the second time, people had seen me work. They had seen me have victories, they had seen me have defeats, they had seen me make mistakes, they had seen me at some high moments but also some low moments. So they knew me, at that point, in the round. I wasn’t just a projection of whatever they hoped for. You know, we always cautioned each other, in the ’08 race, that people were projecting so much onto my campaign—you know, that this would solve every racial problem, or that this indicated that we were beyond race, or that we were going to magically usher in a new era of progressive politics, and that we had vanquished all the backward-looking politics of the past.

And for us to then be able to grind it out, to figure out how do we get out of this Great Recession, and what’s the process where we can finally get health care done even if it’s not pretty, and how do we deal with winding down two wars, and how do we clean up after an administration to reinvigorate things like the Civil Rights Division of the Justice Department. People had seen all that, and then had to make a judgment: Do we want to continue on this course, and do we continue to have faith in this person? And so it is true that, for me at least, in some ways the first race was lightning in a bottle. I saw it, I envisioned the possibility of it, but everything converged in a way that you couldn’t duplicate. The second race as a consequence felt more solid, because it was harder. And you know we didn’t have tailwinds, we had a lot more headwinds.

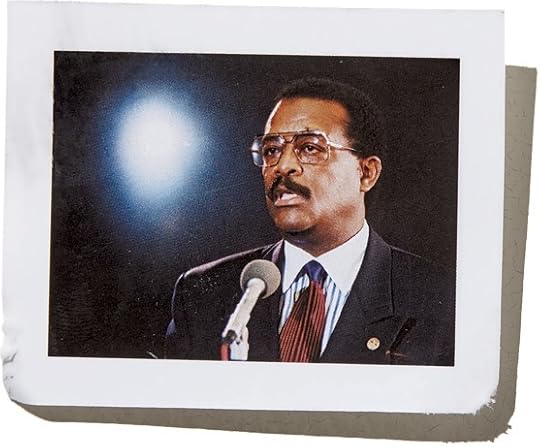

United States Senator Barack Obama campaigns with New York Democratic mayoral candidate Fernando Ferrer in Manhattan on Monday, November 7, 2005. (Ramin Talaie / Getty)

United States Senator Barack Obama campaigns with New York Democratic mayoral candidate Fernando Ferrer in Manhattan on Monday, November 7, 2005. (Ramin Talaie / Getty)Coates: Yeah, I have my own theories about this, and I wonder what yours are. Why were you able to see it?

Obama: The first time?

Coates: Yeah. You said you were able to envision the possibility. Why? I mean, when you think about yourself—because obviously, as you know, a lot of African Americans could not—what’s the difference?

Obama: Yeah. I’d say a couple things. The first was that I had been elected as the senator of Illinois, and Illinois is the most demographically representative state in the country. If you took all the percentages of black, white, Latino, rural, urban, agricultural, manufacturing—[if] you took that cross section across the country, and you shrank it, it would be Illinois. So when I ran for the Senate I had to go into southern Illinois, downstate Illinois, farming communities—some with very tough racial histories, some areas where there just were no African Americans of any number, and I had seen my ability to connect with those communities and those people against some pretty formidable opponents.

When I ran for the Senate, I was one of seven candidates. One of them, Dan Hynes, was already the state comptroller, was the son of the former Senate president and chair of the Democratic Party, a well-established Irish family in the state, who got the endorsement, I think, of 100 out of 103 county chairs as well as the AFL-CIO endorsement. And you had a multimillionaire hedge-fund manager who was spending huge amounts of money. And when we won that race, not just an African American from Chicago, but an African American with an exotic history and a name Barack Hussein Obama, could connect with and appeal to a much broader audience.

And then, keep in mind, that the response of the 2004 convention speech was admittedly over the top, and so I had for two years seen the response I would get when we traveled all around the country. I had campaigned on behalf of other Democrats. Ben Nelson, one of the most conservative Democrats in the Senate, from Nebraska, would only bring in one national Democrat to campaign for him, because typically he tried to distance himself from Democrats—and it was me. And so part of the reason I was willing to run and saw the possibility was that I had had two years in which we were generating enormous crowds all across the country—and the majority of those crowds were not African American; and they were in pretty remote places, or unlikely places. They weren’t just big cities or they weren’t just liberal enclaves. So what that told me was, it was possible.

Coates: Did you have doubts?

Obama: Yes.

Coates: You did have doubts?

Obama: Look, I think Valerie remembers us sitting around our kitchen table—a group of friends of mine, some political advisers, Michelle—and I think our basic assessment was maybe we had a 20, 25 percent chance of winning.

Coates: The presidency?

Obama: The presidency, yeah. Because I did think given the problems President Bush had had, that whoever won the Democratic nomination would win the presidency. And so the issue really was, could I get the nomination, particularly with a formidable candidate like Hillary Clinton already preparing to run? And my view was not that this was a sure thing, but what I never doubted was my ability to get white support.

Coates: You never doubted that?

Obama: No. And I think that in addition to the proof of my Senate race, if you want to go a little deeper, there is no doubt that as a mixed child, as the child of an African and a white woman, who was very close to white grandparents who came from Kansas, that I think the working assumption of discrimination, the working assumption that white people would not treat me right or give me an opportunity, or judge me on the basis of merit—that kind of working assumption is less embedded in my psyche than it is, say, with Michelle. There is a little bit of a biographical element to this. I had as a child seen at least a small cross section of white people, but the people who were closest to me loved me more than anything. And so even as an adult, even by the time I’m 40, 45, 50, that set of memories meant that if I walked into a room and it’s a bunch of white farmers, trade unionists, middle age—I’m not walking in thinking, Man, I’ve got to show them that I’m normal. I walk in there, I think, with a set of assumptions: like, these people look just like my grandparents. And I see the same the same Jell-O mold that my grandmother served, and they’ve got the same, you know, little stuff on their mantelpieces. And so I am maybe disarming them by just assuming that we’re okay. And if anything, my concern had more to do with I’m really young. I mean, when I look back at the pictures of me running in ’08, I look like a kid. And so my insecurities going into the race had more to do with the fact I had only been in the Senate two years. Three, four years earlier I had been a state legislator, and I was now running for the highest office in the land.

Coates: I want to stay with this for a second. You know, to prepare for this piece I’ve been going back and reading some of your writings. And one of the things I noticed going through Dreams From My Father, which I read a long time ago—it’s very different reading it.

Obama: The second time?

Coates: Yeah, and then after eight years. Yeah, and then—

Obama: After seeing how things played out.

Coates: Right. And one of the things I saw in there: Your grandfather has this black dude come over who’s interested in his daughter, and he’s accepting.

Obama: Yeah, listen, I’m always kind of surprised by that. Like I said, it wasn’t Harry Belafonte. This was like an African African. And he was like a blue-black brother. Nilotic. [Laughter] And so, yeah, I will always give my grandparents credit for that. I’m not saying they were happy about it. I’m not saying that they were not, after the guy leaves, looking at each other like, ‘What the heck?’ But whatever misgivings they had, they never expressed to me, never spilled over into how they interacted with me.

Now, part of it, as I say in my book, was we were in this unique environment in Hawaii where I think it was much easier. I don’t know if it would have been as easy for them if they were living in Chicago at the time, because the lines just weren’t as sharply drawn in Hawaii as they were on the mainland. But I do think that at the end of the day, some of my confidence that people are people and that the very specific historical experience and sociological reality of racism in this country has made for significant differences between black and white populations, but that people’s basic human impulses are the same. I mean, that just grows out of who I am. It’s a biological necessity for me to believe that, right? And so my politics ultimately would reflect that.

There’s one last point about this, though, that then bears on my presidency that I think I should point out in terms of both my confidence that I could win in ’08 but also the fact that I was lucky and maybe a little bit naive: In 2008 I was never subjected to the kind of concentrated vilification of Fox News, Rush Limbaugh, the whole conservative-media ecosystem, and so as a consequence, even for my first two years as a senator I was polling at 70 percent. And it was because people basically saw me unfiltered. I was at a town-hall meeting, or I was talking to people directly, or they had met me, or I would speak at a university or go to a VFW hall. But they weren’t seeing some image of me as trying to take away their stuff and give it to black people, and coddle criminals, and all the stereotypes of not just African American politicians but liberal politicians. You started to see that kind of prism being established towards the end of the 2008 race, particularly once Sarah Palin was the nominee. And obviously almost immediately after I was elected, it was deployed in full force. And it had an impact in terms of how a large portion of white voters would see me.

And what that speaks to—and this is something I still strongly believe—is that the suspicion between races, the way it can manifest itself in politics, in part comes out of people’s daily interactions and the fact that we’re segregated by communities, and by schools, and our churches, and people’s memories passed down through generations. But some of it is constructed on a constant basis; it’s being created all the time. And I think what I did not fully appreciate when I first came into this office was the degree to which that reality would be the only thing that a large chunk of the electorate, particularly the white electorate, would see.

You know, Bill Clinton told me an interesting story. He went back to Arkansas with a former aide of his when he was governor and when he was running, who ended up running for Congress and was about to retire from Congress. This was one of the last blue dogs. And as they were traveling around ,this former member of Congress said to Bill, “You know, I don’t think you could win Arkansas today.” And he said, “Well, why not?” He says, “You know, when we used to run, you and I would drive around to these small towns and communities out there, and you’d meet with the publisher and editor of the little small-town paper, and you’d have a conversation with them. And they were fairly knowledgeable about some of the issues, and they had their quirks and blind spots, but basically you as a Democrat could talk about civil rights and the need to invest in communities and they understood that. Except now those papers are all gone and if you go into any bar, you go into any barbershop, the only thing that’s on is Fox News.” And it has shaped an entire generation of voters and tapped into their deepest anxieties …

Coates: Just as a counterpoint to that, I wonder about another argument one might make—that you were more likable to these folks before you had power. In other words, once you literally became a black president, that was a real thing. And that activated their fears—

Obama: Yeah, yeah. Look, I think that the— [long pause]

Coates: Like, that they needed Fox News.

Obama: Yeah, but what I would argue would be that the folks for whom that is true—they hadn’t voted for me in the first place. I mean, what I’m arguing is not that the concerns or suspicions or fears around changing demographics and increased diversity aren’t right there on the surface for a lot of voters. They are. But what I’m saying is that they are shaped and influenced depending on what they see day to day. And they are more malleable, and they can go in a better direction or a worse direction. And if what they are seeing and what they are taking as truth is that this black president is trying to hurt you or take something from you and looking out for “his own,” then they will respond differently than if they hear that this president is trying to help you. But it’s hard. And here are the issues involved and here are the choices that he’s having to make.

There’s no better example of that than the whole debate around Obamacare, where the whole way in which it got framed as ‘He’s trying to take something from you to give free stuff’—in this case free health care but it could also be free phones, or free cheese, or whatever—ended up dominating the debate even in those communities that stood to benefit most from this program. But part of that was the story, the narrative that they were receiving. And people don’t have the ability to fact-check and, you know, sort through what’s true and what’s not, especially on a complicated social program like this.

A young Barack Obama poses with his maternal grandparents, Stanley and Madelyn Dunham. (Reuters)

A young Barack Obama poses with his maternal grandparents, Stanley and Madelyn Dunham. (Reuters)Coates: Do you think that holds true even in an era right now when we have so much access to information?

Obama: Yeah. You know, in some ways the access to all this information has made it easier to set up narratives that are entirely separate from fact. I mean witness the current election and what Trump is doing. There is no grounding in fact. But because, with all the proliferation of websites, and blogs, and digital content, you can just create your own hermetically sealed world where people are never going outside of their existing assumptions, I think it’s a bigger problem, not a worse problem. I guess the point being that: Was there always a certain quotient of people who, even if it was hard for them to admit, would not vote for me because I was African American? Absolutely. That was true when I was running for the U.S. Senate and that would be true if I was trying to catch a cab. Do I believe that’s the majority of white Americans? Absolutely not. And I think my elections proved that.

Do I think that good people who are not instinctively afraid or concerned about an African American in authority can be made afraid, and suspicious, and fearful, because of what they are seeing, hearing, and reading if it’s not attached to the facts, and evidence, and reality? I think that can have a big impact.

Coates: One of the things that I think also is here is not just your ability to envision the presidency, just the optimism for the country you have in general. I think, at this kind of young age you really saw—if I may say so—the best of white America in a very sort of direct way—

Obama: Right.

Coates: Which I think is very different than most African Americans. I didn’t really grow up around white people, but even the abstract construction was as a malignant force in my life, which I had to make my way out of much, much later in life, in my 20s, when I had intimate contact. And I wonder how much of that general optimism you think emanates from your biography. The exposure too, the cosmopolitan nature of all you’ve seen.

Obama: Yeah. I mean, look, I think all of the above. I think I was deeply loved by my mom and my grandparents. I felt that, and I carried that with me. I spent time outside of the United States, which gives you a perspective on how people of all kinds of different races, and ethnicities, and religions, and backgrounds can figure out ways to divide themselves and try to be superior to others. So that I ended up looking at race in America as one example of a broader human problem, rather than something that was unique and I was trapped in. Right? But I also, I think, benefited from the very particular era that I was growing up in, because in some ways, the last 55 years—the years I’ve been on this Earth—have a very particular trajectory of progress that is incomplete, is partial, that middle-class African Americans enjoy in ways that really impoverished African Americans do not yet feel. But that trend would feed my optimism as well.

Now, you know, what’s interesting is the work that I did as an organizer in Chicago would help to temper that optimism and ground it so that it wasn’t just a bunch of happy talk. And it’s one of the reasons why, for the generation just ahead of me, I would learn of the anger, frustration, bitterness of my elders and respect it and understand it even if I ultimately did not agree with it.

Coates: Did you right off the bat, when you first encountered it?

Obama: Yeah. And part of it was just because, you know, I had sort of steeped myself in it, although as still an intellectual exercise. I remember reading The Autobiography of Malcolm X, and I remember reading it, even as a young person, and saying to myself, Now, if this had happened to me, I’d have a very different attitude. Right? And that’s part of what I tried to explain in my race speech in Philadelphia when the Reverend Wright controversies came out. He’s of a different generation. He had different experiences. And that sense of being trapped and caged and witnessing brilliant people broken by an unjust system—family members beaten or jailed, or just harassed, or unable to realize their potential—could drive you crazy. And so I think I not only was mindful enough of it by the time I had moved to Chicago, but even in my relatively sheltered and unique circumstances, I had the experiences that every African American has. Which is somebody in front of a restaurant will hand you the keys, thinking you’re there to park their car.

Or—I write about this in Dreams From My Father—being in a tennis tournament and the tennis coach, who is supposed to look out for all the kids, telling me, ‘Don’t put your finger on the draw that’s been posted about who’s playing who, because you might make it dirty.’ And when you’re 12 years old and look up at some guy, you think: What? Or walking into an elevator and having some woman who you know lives on your floor or above you walk out of the elevator because she’s worried about riding with you even though you’re a kid. So, you know, you have enough there to have a sense of how anger could pool and well up and, in some cases, consume you.

But I also, I think, by that point would have benefited from enough circumstances in which assuming the best in people had paid off—where there had been a teacher who had really been helpful and looked out for me even when I didn’t completely deserve it. Or, you know, just witnessing the example of a Dr. King, or an Arthur Ashe. And so I’m coming of age at a time where you’ve got the strength and defiance of a Malcolm or an Ali, and you’ve also got the soulfulness and the moral strength of a King. And those things are speaking to each other. They’re in a conversation. And you’re saying to yourself, I can draw from both of those traditions. And there may be times where it is right to be angry and defiant. And there may be times where you’ve got to give the country and white people the benefit of the doubt. And if you’re so eager to give them the benefit of the doubt that they slap you down and you don’t know it, that’s a problem. But if you’re so invested in the anger that you don’t seen when somebody is putting out their hand in a sincere gesture of friendship, then you’ve now become your own jailer. It’s not just someone else jailing you.

Coates: Right. It occurs to me, obviously, to have our first black president a product of the times, a product of certain things going around, a product in some part of the administration before—but have you ever thought you needed to be a certain person who had not had this sort of trauma at a young age? Who was capable of giving that sort of optimism—that it couldn’t just be, okay now the country’s ready, Joe Blow Black Dude steps up, and wins, with political gifts, obviously—but I think that optimism sticks out.

Obama: Yeah. Look, I have no doubt that the first African American president had to be somebody who could speak the way I did in the 2004 convention speech about the ideal of what America is. As opposed to—

Coates: What it isn’t. What it hadn’t done.

Obama: Right. But that’s true of just running for president generally. Very rarely has somebody won the presidency based on a dark, grim vision of what America is.

Coates: Well, we’re getting close.

Obama: Right. Well, we’ll see my proposition tested in this election cycle. Maybe the closest is Nixon, who employed the southern strategy and surfed the backlash coming out of both the antiwar movement and the civil-rights movement. But as a general proposition, it’s hard to run for president by telling people how terrible things are. Because at some level what the people want to feel is that the person leading them sees the best in them. And so, did the innate optimism that I carried with me both because of my upbringing and maybe just temperament help? Absolutely. But I’m not sure it had to be me. I’ve said before that Deval Patrick could have been the person who broke that particular barrier back in 2008. And it so happened that he had just run for governor and felt committed to finishing up his term. But he has the gifts and I think the persona that would have appealed at that time to the American public. And there are probably some other figures as well who might have pulled it off.

Coates: How did you feel when that optimism was directly challenged? I was telling Valerie this the other day: We’re at home watching the State of the Union and some guy stands up and yells, “You lie.”

Obama: [Laughing] Yeah, that was something.

Coates: And this is a guy from South Carolina—we know about South Carolina, he’s confirming everything we feel—

Obama: Yeah, that was something. I still remember looking at him like, Really? what are you doing? Sit down.

Coates: Were you angry?

Obama: You know, I’ve got to say, I wasn’t angry so much as I was just stunned. It was just so unexpected and raw that I didn’t—and to me just kind of ridiculous—that I couldn’t really generate anger.

Coates: And you didn’t feel insulted or … ?

Obama: Well … look. There is no doubt that there have been occasions during my presidency when I’ve said, ‘Y’all just would not do this with anybody else.’ Now, obviously the whole birth-certificate thing is the most salient example. I mean, there’ve been 43 other presidents. I don’t remember the issue of where somebody was born ever coming up before. And so there have been other instances like that. There was one time where I was making a statement out here. And in the middle of my statement, somebody just started yelling. It was a reporter—

Coates: It was a reporter from The Daily Caller. I remember this.

Obama: From The Daily Caller. And I was probably more mad on that one. Because—whereas Joe Wilson, you got a sense of just this weird impulsive action on his part—this felt orchestrated and showed a lack of respect for the office that I think was unprecedented in a Rose Garden statement. Part of what’s been difficult, though, during my presidency, is untangling the degree to which some of these issues are because of race and some of these issues being reflective of just a coarsening of the political culture and a sharpening of the political divides. Because I do remember watching Bill Clinton get impeached and Hillary Clinton being accused of killing Vince Foster. And if you ask them, I’m sure they would say, ‘No, actually, what you’re experiencing is not because you’re black, it’s because you’re a Democrat.’ And right around the beginning of Bill Clinton’s presidency and what corresponds with the rise of right-wing media, a lot of the old boundaries and rules of civility just broke down.

Now, one way to think about this is that issues of race and issues of political philosophy have always been entangled, and it’s hard to draw them out. Right? So when I think about the Tea Party or conservatives who’ve opposed my agenda, I have no doubt that there are those who oppose my agenda because they have a coherent and sincere view about the role of the federal government relative to the state governments; they believe that an overreaching federal power that is taxing, regulating, redistributing is contrary to the vision of freedom that the Founders intended—and they can believe those things independent of race.

Having said that, a rudimentary knowledge of American history tells you that the relationship between the federal government and the states was very much mixed up with attitudes towards slavery, attitudes towards Jim Crow, attitudes towards antipoverty programs and who benefited and who didn’t. And so I’m careful not to attribute any particular resistance or slight or opposition to race. But what I do believe is that if somebody didn’t have a problem with their daddy being employed by the federal government, and didn’t have a problem with the Tennessee Valley Authority electrifying certain communities, and didn’t have a problem with the interstate highway system being built, and didn’t have a problem with the GI Bill, and didn’t have a problem with the [Federal Housing Administration] subsidizing the suburbanization of America, and that all helped you build wealth and create a middle class—and then suddenly as soon as African Americans or Latinos are interested in availing themselves of those same mechanisms as ladders into the middle class, you now have a violent opposition to them, then I think you at least have to ask yourself the question of how consistent you are and what’s different, what’s changed.

You know, I always talk about when I was doing civil-rights law and people would talk about the dearth of African Americans in police departments and fire departments around the country. And they would say, ‘Well, this should be a meritocracy, and everybody needs to take a test, and that’s objective, and anything else is affirmative action and unfair.’ And I’m thinking, Well, when Officer O’Malley or Officer Krupke was walking the beat, nobody said it was a meritocracy then. What happened? We’re suddenly now of the notion that somebody who’s a police officer or firefighter having some affinity and familiarity with the community they are serving is completely out of bounds. What changed? So I think that one of the things I’m always trying to do is to just promote a consistent philosophy and ethic about how government can help everybody and try to show that what worked for the majority community in previous generations would be likely to work now, too. And the burden is on those who oppose investments in these things to explain what’s changed.

Coates: I was caught because you said that you were the only person that Ben Nelson brought in to campaign for him. And maybe my memory is wrong, but I believe he was one of the harder folks to negotiate with in terms of getting the [Affordable Care Act] passed. You can correct me if I’m wrong, but as I recall, I heard in 2008 from your campaign that there was room to work across party lines, there was room for people who disagree to come together. If we just put forth intelligent proposals, folks would be able to come together. When did you realize it wasn’t quite going to go that way?

Obama: In the first two weeks. Mitch McConnell’s statement about how our No. 1 goal was to make sure Obama was a one-term president. That hadn’t surfaced publicly yet, but—

Coates: Did that surprise you when that got to you?

Obama: No, because by that time we had seen the behavior. But, and I’ve told this story before, the economy was in a free fall. And the one thing I anticipated was that we could get some bipartisan cooperation early on, at least to stop the bleeding, before normal politics kicked in. I mean, we were losing hundreds of thousands of jobs, folks were losing their homes everywhere, the financial system was locked up, the auto industry was melting down. And the risks of us going into 15 percent unemployment and a real catastrophic situation were reasonably high. And so speed was of the essence. And we put together this package, called the Recovery Act, which was basically a big stimulus package, and we designed it in such a way that we thought it would have some appeal to Republicans. Because we had infrastructure spending, and we had spending going directly to states to make sure they weren’t laying off teachers and police and firefighters, and we had a big tax cut for ordinary families, as well as spending for clean energy and education and a whole host of other things.

And I still remember the day that I’m scheduled to meet with the House Republican caucus, and I get into the car and we’re driving up, and I forget who it was, but one of my staff tells me that John Boehner has just announced that they are opposed to the Recovery Act. Before they had even seen it, before I had made a presentation, before I had had a conversation with them. This was going to be sort of the opening round of negotiations where I’m explaining to them the dire situation and asking for a bipartisan effort to help the American people. And they had shut it down. And that, I think, gave me an inkling of a different political environment than the one that we had seen in the past.

Now, again, I think it’s really important to understand that had there been a white president—had Hillary Clinton been president, or Joe Biden been president—it is entirely possible that they would have pursued the same strategy. Because the way politics had been structured at that point, where there was so much political gerrymandering, and the media has increasingly become so balkanized, there was an understandable political incentive for them not to cooperate.

You know, the genius of Mitch McConnell—and to some degree John Boehner—was a recognition that if we were about to go into a bad recession and the president had come in on this wave of good feeling, Democrats control the House, they control the Senate—if he’s completely successful in yanking us out of this and cleaning up a mess a Republican president had left behind, that we might lock in Democratic majorities for a very long time. But on the other hand, if Republicans didn’t cooperate, and there was not a portrait of bipartisan cooperation and a functional federal government, then the party in power would pay the price and that they could win back the Senate and/or the House. That wasn’t an inaccurate political calculation. And they executed well, and we got clobbered in 2010. So the lesson I drew there was a political lesson. It was not a racial lesson.

Barack Obama speaks alongside Speaker of the House John Boehner and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell prior to a meeting of the bipartisan, bicameral leadership of Congress in the Cabinet Room at the White House in Washington, D.C., January 13, 2015. (Saul Loab / AFP / Getty)

Barack Obama speaks alongside Speaker of the House John Boehner and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell prior to a meeting of the bipartisan, bicameral leadership of Congress in the Cabinet Room at the White House in Washington, D.C., January 13, 2015. (Saul Loab / AFP / Getty)Coates: I just want to push this a little bit more. What about the idea that it’s not so much you as a black man as president, but the fact that we’re at a point in history where the Democratic Party, especially locally—the states—has become very racialized?

Obama: Well, I think what is true is that when the southern Democrats all flipped, and over the course of successive elections, dating back to ’68, you have a process whereby 90 percent African Americans are voting in the Democratic Party, and southern and many rural and western whites are increasingly voting Republican, and cultural issues become more prominent, that it helped to accelerate what has been called this great sorting. And when you combine that with political gerrymandering, when you combine that with the impact of the media, it makes it easier for Republicans not to cooperate, because there’s nobody in their districts that will punish them for not cooperating with a Democratic president. There is no doubt that that’s true.

Now, I leave it at this, and maybe we can pick it up in our next conversation: I think what was more of an early lesson around race was the Skip Gates incident. And the reason that was interesting to me was because I didn’t think it was that big of a deal, and I didn’t think my statement was particularly controversial. I don’t know if you know Skip, but Skip is a little guy who uses a cane and has a limp and is late 60s. And if he’s on his porch and he ends up being handcuffed, then my working assumption was, everybody would kind of think that was kind of an overreaction.

Now, Skip can be, you know, salty, so I have no doubt that—I wasn’t there, but I would not be surprised if Skip used some inappropriate language with the officer when the officer came up to question him. And, you know, this wasn’t some great civil-rights injustice. But it was interesting to see how what I thought was sort of an offhanded and fairly innocuous statement, which was, look, you know, this probably wasn’t—I think I said this: The Cambridge police probably handled this a little stupidly. And the fact of the matter is that part of the reason this becomes news is because there’s this underlying feeling on the part of a lot of African Americans that interaction with police is not always evenhanded.

To see the cultural reaction, and in retrospect to see how my poll numbers with white voters dropped really significantly off this one tempest in a teapot, that was instructive. Now, there are some who say that’s when Obama started trimming his sails on racial issues. That’s not accurate. That’s not accurate. The truth is that I wanted to make sure that we did not have a bunch of distractions at a time where I’m just putting out fires everywhere. I mean, I’ve got two wars, I’ve got an economic crisis of a proportion we haven’t seen since the Great Depression, and that was not the time, from my perspective, to just open up a big floodgate of conversation around race, which I did not think was going to be productive. What I did learn from that, though, were two things. One was—that was one lesson among many, in those first six months—about the magnification of my words. So if I look at the statement that I made at the time that I thought was pretty innocuous, using the word stupid would be a word I’d never use now, just because I’m president and everything gets magnified. So I could have made the same point in a way that would not have, I think, felt as visceral.

Coates: You think you could have got that across about it?

Obama: I think I could have got it across better. So that’s point No. 1. Point No. 2, though, is: What it also showed me was the degree to which the filter that I discussed earlier can completely shape a narrative in a way that will just run until you get some sort of circuit breaker going. And part of what I had to start teaching my staff was: not to overreact to that. Because what is absolutely true is that, you know, my press office freaked out around that in a way that I was not that freaked out about. There was a part of me that was like, ‘Okay, so the Cambridge police isn’t happy with me, but this really isn’t a big deal, we’ve got other stuff we’ve got to worry about.’ They were channeling what they were seeing coming at them suddenly in the press room and through news reports.

And what that meant then was that, on issues of race, certainly on issues of race as it relates to law enforcement, what I wanted to make sure of is that when we said something that was precise, that we were choosing those moments where we had the best chance of driving home the point and extracting real progress. And that we needed to think about how the narrative would be shaped in a way that was constructive rather than us just being on the defense all the time. You know, so it’s interesting for me to think about that moment and then all the subsequent issues that have come up.

Coates: Yeah, it got a lot worse than that, than being arrested on your porch.

Obama: Well, exactly. Right. But the dynamic around which everybody went to their respective corners on what was such a small incident, it foreshadowed the response that I would get later. And to this day, it does not matter how many times I will say, “You know what? Our police have a tough job and 99 percent of them are doing a great job,” etc., and I will get letters afterwards: “Why are you always throwing cops under the bus? Why do you hate police?” [Laughing] And I literally made my press office sort of put together a packet of something like 30 statements that I’ve made, highlighted in yellow, that I will send to constituents—because oftentimes, you know, these are the wives of police officers who are scared for their husbands, and I don’t want to ignore them. But it tells me what they’re seeing. It tells me what they’re hearing. The filter through which they are receiving information is powerful. And that was an early lesson about how powerful that filter was.

December 13, 2016

The Making of a Black President

In his January/Febrary 2017 cover story, Ta-Nehisi Coates explores President Barack Obama’s journey to the White House. This short animation uses recordings from Coates’s conversations with Obama to illustrate the young president’s doubts and convictions along the way. "I think our basic assessment was maybe we had a 20-25 percent chance of winning,” Obama says of his run for president. “But what I never doubted was my ability to get white support.” Read the full story here.

October 4, 2016

On the Right to Know Everything

Here’s an interesting piece from Hamilton Nolan arguing for a rather expansive journalistic mission. The cause is the recent unmasking of celebrated novelist Elena Ferrante. As most of her fans know, “Elena Ferrante” is (or was) a pseudonym. Nolan believes that the revelation of Ferrante’s real name and identity, against her wishes, is at the core of what journalism is ultimately about:

The very general proposition of journalism is this: The public has a right to know true things that are important to the public. It is the job of journalists to supply the public with these true things. This broad idea applies in practice not just to the goings-on of government, but to crime, and business, and science, and sports, and the actions of all sorts of people who are famous and/or notorious, either temporarily or permanently.

There’s a lot here that’s left vague in Nolan’s proposition, beginning with the imagined entity Nolan claims to be advocating for—the public. Nolan neither defines who this “public” is, nor proposes a means for assessing what it takes as important versus what it takes as trivial. How do we know, for instance, that “the public” really thought it was important for journalists to expose the facts of her life?

And yet on behalf of this vague entity, Nolan claims expansive powers—the public has the right to know anything it deems “important.” Essentially fame is the forfeiture of basic human and individual privileges in favor of an ill-defined public interest. It’s worth taking this logic to its conclusions. If “the public” wishes to know the identity of a whistle-blower who helped down a corrupt national official, then journalists should reveal it. If the public wishes to know the identity of the woman who accused Nate Parker of rape, then journalists should publish it. If “the public” decides, for instance, that it’s “important” to see the tape that a stalker took of Erin Andrews in her hotel room, then evidently journalists should offer this up too. Nolan offered no exemption for famous children either, so presumably all of their doings are also part of the pot of public knowledge.

It is certainly true that Ferrante’s identity is “newsworthy”—which is to say some demonstrable and significant number of people would like to know who she is. But “newsworthy,” a term that could be applied to everything from Watergate to sex tapes, lacks the moral force of claiming to act on behalf of the presumed rights of the public. “Newsworthy” describes how journalism works. But it doesn’t engage the complicated, constant ethical dilemmas which journalists face over what to report and what not to report. Nolan claims to be engaging that question, but what he’s actually doing is avoiding the hard work which it entails.

Admittedly, I’m biased. But I get nervous when I see journalists blithely and casually invoke the right of the public to know, without any attempt to define those terms, their limitations, and their history.

On The Right To Know Everything

Here’s an interesting piece from Hamilton Nolan arguing for a rather expansive journalistic mission. The cause is the recent unmasking of celebrated novelist Elena Ferrante. As most of her fans know, “Elena Ferrante” is (or was) a pseudonym. Nolan believes that the revelation of Ferrante’s real name and identity, against her wishes, is at the core of what journalism is ultimately about:

The very general proposition of journalism is this: The public has a right to know true things that are important to the public. It is the job of journalists to supply the public with these true things. This broad idea applies in practice not just to the goings-on of government, but to crime, and business, and science, and sports, and the actions of all sorts of people who are famous and/or notorious, either temporarily or permanently.

There’s a lot here that’s left vague in Nolan’s proposition, beginning with the imagined entity Nolan claims to be advocating for—the public. Nolan neither defines who this “public” is, nor proposes a means for assessing what it takes as important versus what it takes as trivial. How do we know, for instance, that “the public” really thought it was important for journalists to expose the facts of her life?

And yet on behalf of this vague entity, Nolan claims expansive powers—the public has the right to know anything it deems “important.” Essentially fame is the forfeiture of basic human and individual privileges in favor of an ill-defined public interest. It’s worth taking this logic to its conclusions. If “the public” wishes to know the identity of a whistle-blower who helped down a corrupt national official, than journalists should reveal it. If the public wishes to know the identity of the woman who accused Nate Parker of rape, than journalists should publish it. If “the public” decides, for instance, that its “important” to see the tape that a stalker took of Erin Andrews in her hotel room, than evidently journalists should offer this up too. Nolan offered no exemption for famous children either, so presumably all of their doings are also part of the pot of public knowledge.

It is certainly true is that Ferrante’s identity is “newsworthy”—which is to say some demonstrable and significant number of people would like to know who she is. But “newsworthy,” is a term could be applied to everything from Watergate to sex tapes, lacks the moral force of claiming to act on behalf of the presumed rights of the public. “Newsworthy” describes how journalism works. But it doesn’t engage the complicated, constant ethical dilemmas journalist face over what to report and what not to report. Nolan claims that to be engaging that question, but what he’s actually doing is avoiding the hard work which it entails.

Admittedly, I’m biased. But I get nervous when I see journalists blithely and casually invoke the right of the public to know, without any attempt to define those terms, their limitations, nor their history.

September 12, 2016

How Breitbart Conquered the Media

In July of 2010, journalist and provocateur Andrew Breitbart posted a video excerpt of remarks on his site purporting to expose “evidence of racism coming from a federal appointee and NAACP award recipient.” This was an explosive charge. The Tea Party was ascendant then and racial grievance was one of its animating features.

In Obama’s America, “the white kids now get beat up, with the black kids cheering,” explained Rush Limbaugh. “And of course everybody says the white kid deserved it—he was born a racist, he’s white.” Iowa Republican Representative Steve King charged that Obama has a “default mechanism” that “favors the black person.” Tea Party supporters arrived at rallies charging Obama with endorsing “white slavery.” Now Breitbart purported to have in his hands proof that would prove that it was the NAACP and its allies in the White House who were the real racists.

Breitbart’s “video evidence” was stunningly effective. The NAACP immediately denounced the remarks and the U.S. Department of Agriculture official who’d made them—Shirley Sherrod—was, in short order, forced to submit her resignation via Blackberry. “You’re going to be on Glenn Beck tonight,” she was told. The remark was revealing. It was Beck who best channeled the Tea Party’s spirit of racial victimization. The president was a man with “a deep-seated hatred of white people,” claimed Beck. “This guy is, I believe, a racist."

So frightened were the Obama administration officials and the NAACP that they did not bother to ask if Breitbart had honestly rendered Sherrod’s comments. They did not seek to understand their context or meaning. They did not even bother to see who Shirley Sherrod actually was and whether the charge accorded with her history. Instead they dispensed with any pursuit of the truth, allied themselves with fear, and humiliated Shirley Sherrod.

Later, when it was revealed that Breitbart had perpetrated a massive deception, when no less than Glenn Beck defended Sherrod, it was easy to think that Andrew Breitbart had, himself, endured a humiliating and disqualifying loss.

Events on Friday threw that thesis into doubt. Hillary Clinton made a claim—half of Donald Trump’s supporters are motivated by some form of bigotry. “The racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, Islamophobic—you name it,” she said. “And unfortunately, there are people like that, and he has lifted them up.” Clinton went on to claim that there is another half—people disappointed in the government and economy who are desperate for change. The second part of this claim received very little attention, simply because much of media could not make its way past the first half. The resultant uproar challenges the idea that Breitbart lost.

Indeed, what Breitbart understood, what his spiritual heir Donald Trump has banked on, what Hillary Clinton’s recent pillorying has clarified, is that white grievance, no matter how ill-founded, can never be humiliating nor disqualifying. On the contrary, it is a right to be respected at every level of American society from the beer-hall to the penthouse to the newsroom.

The comment was “a self-inflicted wound” claimed the Washington Post reporter Dan Balz. “It was very close to the dictionary definition of bigoted,” asserted John Heilemann. My colleague Ron Fournier and the Post’s Aaron Blake were both taken aback by the implicit math of Clinton’s statement. “Clinton appeared to be slapping the ‘racist, sexist, homophobic, xenophobic, Islamaphobic’ label on about 20 percent of the country,” wrote Blake in a post whose headline echoed that of the Trump campaign manager’s website. “That's no small thing.” Whether or not it was a false thing remained uninvestigated.

The media’s criticism of Clinton’s claim has been matched in vehemence only by their allergy to exploring it. “Candidates should not be sociologists,” glibly asserted David Brooks on Meet The Press. I’m not sure why not, but certainly journalists who broadcast their opinions to the nation should have to evince something more than a superficial curiosity. It is easy enough to look into Clinton’s claim and verify it or falsify it. The numbers are all around us. And the story need not end there. A curious journalist might ask what those numbers mean, or even push further, and ask what it means that the ranks of the Democratic Party are not totally free of their own deplorables.

Instead what followed was not journalism but, as Jamelle Bouie accurately dubbed it, “theater criticism.” Fournier and Blake’s revulsion at the thought that some 20 percent of the country, in some fashion, fit into that basket is illustrative. Neither made any apparent attempt to investigate the claim. No polling data appears in either piece and no reasons are given for why the estimate is untrue. It simply can’t be true—even if the data says that it actually is.

To understand how truly bizarre this method of opining is, consider the following: Had polling showed that relatively few Trump supporters believe black people are lazy and criminally-inclined, if only a tiny minority of Trump supporters believed that Muslims should be banned from the country, if birtherism carried no real weight among them, would journalists decline to point this out as they excoriated her? Of course not. But the case against Clinton’s “basket of deplorables” is a triumph of style over substance, of clamorous white grievance over knowable facts.

This is what Andrew Breitbart, and his progeny, ultimately understood. What Shirley Sherrod did or did not do really didn’t matter. White racial grievance enjoys automatic credibility, and even when disproven, it is never disqualifying of its bearers. It is very difficult to imagine, for instance, a 9/11 truther, who happened to be black, becoming even a governor. And yet we live in an era in which the country’s leading birther might well be president. This fact certainly horrifies some of the same journalists who attacked Clinton this weekend. But what they have yet to come to grips with is that Donald Trump is a democratic phenomenon, and that there are actual people—not trolls under a bridge—whom he, and his prejudices against Latinos, Muslims, and blacks, represent.

I do not believe that journalists are so powerful as to disabuse this group of their beliefs. But there is something to be said for not contributing to an opportunistic ignorance. For much of this campaign journalists have attacked Hillary Clinton for being evasive and avoiding hard questioning from their ranks. And then the second Clinton is forthright and says something revealing, she is attacked—not for the substance of what she’s said—but simply for having said it. This hypocrisy carries a chilling implicit message: Lie to me. Lie to the country. Lie to everyone. This weekend was not just another misanalysis, it was a shocking betrayal of the journalistic mission which should urge the revelation of truth as opposed to the propagation of hot takes, Washington jargon, and politics-speak.

The shame reflects an ugly and lethal trend in this country’s history—an ever-present impulse to ignore and minimize racism, an aversion to calling it by its name. For nearly a century and a half, this country deluded itself into thinking that its greatest calamity, the Civil War, had nothing to do with one of its greatest sins, enslavement. It deluded itself in this manner despite available evidence to the contrary. Lynchings, pogroms, and plunder proceeded from this fiction. Writers, journalists, and educators embroidered a national lie, and thus a safe space for the violent tempers of those who needed to be white was preserved.

The safe space for the act of being white endures today. This weekend, the media, an ostensibly great American institution, saw it challenged and—not for the first time—organized to preserve it. For speaking a truth, backed up by data, Clinton was accused of promoting bigotry. No. The true crime was endangering white consciousness. So it was when the president asserted that it was stupid to arrest a man for breaking into his own home. So it was when the president said that if he had a son, he would look like Trayvon Martin. And so it is when reformers suggest police not stop citizens on so flimsy a pretext as furtive movements. The need to be white is a sensitive matter—one which our institutions are inexorably and mindlessly bound to protect.

What O. J. Simpson Means to Me

My reaction to O. J. Simpson’s arrest for the murder of his ex-wife Nicole Simpson and her friend Ron Goldman was atypical. It was 1994. I was a young black man attending a historically black university in the majority-black city of Washington, D.C., with zero sympathy for Simpson, zero understanding of the sympathy he elicited from my people, and zero appreciation for the defense team’s claim that Simpson had been targeted because he was black.

O. J. Simpson wasn’t black. He came of age in the 1960s—the era of Muhammad Ali’s opposition to the Vietnam War and John Carlos and Tommie Smith’s black-power salute at the 1968 Olympics. But the O. J. Simpson I knew, and the one poignantly depicted this year in Ezra Edelman’s epic documentary, O.J.: Made in America, recognized only one struggle—the struggle to advance O. J. Simpson. When the activist Harry Edwards attempted to enlist Simpson in the Olympic boycott, Simpson rebuffed him and later claimed that organizers like Edwards had tried to “use” him. Protest “hurt Tommie Smith, it hurt John Carlos,” Simpson said. Smith and Carlos were “standing on [Edwards’s] platform, [when] they should have been standing on their own platform.”

My view that Simpson existed beyond the borders of black America was based not merely on his narrow political consciousness, but on his own words. “My biggest accomplishment,” Simpson once told the journalist Robert Lipsyte, “is that people look at me like a man first, not a black man.” Simpson went on to tell the story of a wedding he’d attended with his first wife and a group of black friends. At some point he overheard a white guest remark, “Look, there’s O. J. Simpson and some niggers.” Simpson confessed that the remark hurt. But that wasn’t the point of the story. The point was not being seen as one of the “niggers.”

Simpson sought to be post-racial in a world that was not. His myriad achievements—becoming the premier running back in college football, the first NFL running back to rush for 2,000 yards in a season, one of the first black pitchmen for corporate America—did not mark the erosion of the great wall between black and white Americans. It marked Simpson’s individual success at hurdling that wall. Landing on the other side, Simpson, a product of public housing in inner-city San Francisco, found reinvention as a celebrity. He became wealthy. He courted the attentions and advice of affluent businessmen. And though he’d married Marguerite Whitley, who was black, the same year he arrived at the University of Southern California, he now courted white women. “What I’m doing is not for principles or black people,” Simpson told Lipsyte. “No, I’m dealing first for O. J. Simpson, his wife, and his babies.”

Protesters outside the Los Angeles courthouse rallied in support of Simpson’s defense team. Community activists also backed Simpson, and black vendors sold "Run O.J." and "Free O. J. Simpson" T-shirts. (AFP / Getty)

Protesters outside the Los Angeles courthouse rallied in support of Simpson’s defense team. Community activists also backed Simpson, and black vendors sold "Run O.J." and "Free O. J. Simpson" T-shirts. (AFP / Getty)And yet, during his trial, whenever I walked the streets of D.C., I saw black people broadcasting their support as though he were one of them. Vendors hawked run o.j. and free o. j. simpson T‑shirts. Community activists, for whom Simpson had previously had no use, offered fervent defenses of him. When the verdict was announced, national-news cameras came to Howard Law School to record what turned out to be a jubilant response to Simpson’s acquittal. I found all of this very frustrating. I was 19 years old. I was the kind of militant black kid who flirted with Louis Farrakhan, Frantz Fanon, and veganism and who believed “What should black people do?” was a question that could be asked in earnest. The answer, I was sure, would open a new era of black excellence. The support of Simpson was a step backward. It struck me as unintelligent, politically immature, and ill-advised.

Two things, it seemed to me, could be true at once: Simpson was a serial abuser who killed his ex-wife, and the Los Angeles Police Department was a brutal army of occupation. So why was it that the latter seemed to be all that mattered, and what did it have to do with Simpson, who lived a life far beyond the embattled ghettos of L.A.? I vented in the school newspaper. “Since Simpson’s practices show he clearly has no interest in the affairs of black people,” I wrote, “the question becomes why do blacks have any interest in him?” In those days, I conceived of African Americans as a kind of political party, which needed only, in unison, to select the correct strategy in order to make the scourge of racism disappear. Expending political capital on O. J. Simpson struck me as exactly the opposite of the correct strategy. Looking back, I realize what eluded me. I had lived among black people all my life, but somehow I had come to see them as abstractions, not as humans.

I had not yet read Ragtime, the E. L. Doctorow novel that Simpson claimed to love. After his retirement in 1979, he began doing some acting and dreamed of playing Coalhouse Walker in the film adaptation of the book. Simpson felt the role of Walker, a black ragtime piano player turned revolutionary, matched his life. The parallels are strained—and in any case Simpson lost the role to Howard Rollins. But Simpson does resemble another character in the book, one whose feats explain the strange bond between Simpson and the black community. Doctorow offers a fictionalized Harry Houdini, whose escapes from straitjackets, bank vaults, piano cases, and mailbags thrill the poor people of the nation. He is jailed in Boston, imprisoned on an English ship, tossed into the Seine in manacles. Each time, he escapes. Houdini’s act allows him to make the greatest escape of all—out of poverty—though he eventually discovers that no amount of money will buy him the respect of the elite. The poor are enthralled by Houdini not because he organizes on their behalf, but because his exploits resonate with them: They know that their lives are trapdoored and trip-wired, that they too have been jailed, imprisoned, chained, and tossed into the sea. A Houdini performance was their life in miniature, with one heroic difference—he escaped.

Long before he led the police on a chase through L.A., Simpson had been an escape artist. His rare athletic talent freed him from an impoverished childhood, and brought him to USC on a football scholarship in 1967. Made in America, deftly capturing his athleticism, is alert to symbolism too, replaying Simpson’s manifold escapes while at USC and later with the Buffalo Bills. They are dazzling to behold. Simpson’s speed was enhanced not by grace but by awkwardness. In one frame he leaps past a defender, lands seemingly off balance, and then cuts across the field at full velocity. At several junctures, you expect him to fall, and the one time he does, the defender falls with him—but then Simpson, in a matter of milliseconds, glides to his feet and races off. He would angle himself against the earth, his hips flying one way, his head another. He seemed to run too high, with his chest exposed, presenting what should have been an inviting target for the defense. And yet he escaped.

For many black residents of Los Angeles in 1994, the idea that the LAPD might frame a black man was entirely plausible. The prosecution’s careless gathering of evidence only confirmed the distrust. (Vince Bucci / Getty)

For many black residents of Los Angeles in 1994, the idea that the LAPD might frame a black man was entirely plausible. The prosecution’s careless gathering of evidence only confirmed the distrust. (Vince Bucci / Getty)Simpson was a running back, a position dominated by African Americans for the past half century—a fact that has often been invoked to boost racist thinking about the innate athleticism of blacks. More pertinent, the job of the running back—to escape—is the most basic of vocations, one that a kid from the projects can begin practicing in that first game of tag. Running also holds a special significance to a people denied violent resistance as a viable option, if only because it has always been the most potent tool available. The runaway slave is a fixture in the American imagination. As the writer Isabel Wilkerson notes in her account of the Great Migration, the blacks who fled the South during the 20th century “did what human beings looking for freedom, throughout history, have often done. They left.” There is also a less reputable history of fleeing among African Americans—the tradition of those blacks light enough to “pass” as white and disappear into the overclass.

Simpson’s great fortune was to reach the height of his powers in the 1970s, after the civil-rights movement, a time when one might enact the rituals of passing not by looking white, but by possessing qualities that white society envied. Simpson was a celebrity. He was handsome, articulate, and charming. He was identifiably black, but measured against the brashness of Muhammad Ali and the coiled rage of Jim Brown, his distinction was to radiate reassurance and respectability. In the successful series of ads he starred in for Hertz beginning in 1975, he was still running—only now through airports, an icon of social mobility, with white people cheering him on: “Go, O.J.”

An old friend of Simpson’s says in Made in America that Simpson was “seduced by white society.” Perhaps. But the seduction was mutual, and he used his football fame to gain access to white patrons eager to expose him to the finer things in life. “I took him places where I think very few black men had ever been,” Frank Olson, the former CEO of Hertz, says in the film. Simpson mingled with wealthy entrepreneurs at golf clubs where he was one of the few black members, or the first and only black member. He gave them the thrill of convening with a real sports hero at his mansion, Rockingham, nestled in the wealthy white suburb of Brentwood. Simpson’s social circle helped him amass a small fortune. By the 1990s, his net worth was estimated to be $10 million. He was the CEO of O. J. Simpson Enterprises, which owned stakes in hotels and restaurants, and he sat on four different corporate boards.

“My biggest accomplishment,” Simpson once told a journalist, “is that people look at me like a man first, not a black man.” After his acquittal, he read press coverage that treated him as a black icon. (Lawrence Schiller / Getty)

“My biggest accomplishment,” Simpson once told a journalist, “is that people look at me like a man first, not a black man.” After his acquittal, he read press coverage that treated him as a black icon. (Lawrence Schiller / Getty)His pursuit of white women was profligate. In a telling moment in the documentary, Joe Bell, a friend of Simpson’s since childhood, recalls them slowly cruising down Rodeo Drive in the 1970s and being awed by the response. “Women come up, throw their arms around O.J., and just lay it on him,” Bell says. “Not just women. White women. Fine white women.” In 1977, Simpson began an affair with a beautiful blond 18-year-old, Nicole Brown, who came home from their first date with her pants ripped. “Well, he was a little forceful,” she told a friend. Two years later, he left Marguerite to pursue a relationship with Nicole. But the affairs continued: Bond girls, Playboy playmates, models, actresses, most of them white. For Simpson, the women on his arm were not women but bodies, ornaments, evidence of conquests—an outlook he had seen taken to its most violent conclusions in the form of neighborhood pimps. “Man, they’d beat a ho down right there on the street,” Bell remembers, laughing. “So that all the women would know this is the kind of treatment you’re gonna get if you don’t bring me my money.” Those women were black, but the basic notion of women as property knows no racial boundaries. Nicole Brown was proof to the world that Simpson, among the millions of black men caught in the maze of American racism, had risen above it. What sort of abuse—verbal and physical—was going on behind the mansion gates, almost no one, black or white, guessed. Or much cared.

The goings-on in the ghettos of L.A. were both more knowable and better explored—but not by O. J. Simpson. He eschewed involvement in any sort of politics that might tarnish his brand, and thus his pursuit of wealth. If it was easy for Simpson to forget the world he came from, that was partly because the world he now belonged to was invested in forgetting. In an incredible moment early on in the documentary, Edelman, off camera, asks a white USC teammate of Simpson’s what he remembers about 1968. A montage of violent events flashes across the screen—Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, Robert F. Kennedy’s assassination, the raucous Democratic National Convention. Edelman then returns to the teammate, who says, “I think of winning all the games, getting O.J. famous, everybody on campus thinking it’s the greatest thing on Earth. That’s all we thought about. There was nothing else going on.”

But Edelman does not allow us to forget, because the Simpson story turned out to be intimately enmeshed with the story of black Los Angeles and its relationship with the police. This was the community the Simpson jury was drawn from, and ultimately the one that held his life in the balance. For years, much of the country has wondered how Simpson could possibly have been found innocent. An unspoken assumption underlies this conjecture—that the jury understood the legal system to be credible. What the film makes clear in piecing together a parade of victims beaten, killed, and harassed by the LAPD is that the predominantly black jury—quite rightfully—understood no such thing.

Even I, college radical that I was, grasped the LAPD’s brutality only abstractly. The officers were brutal because my own politics, and my own experiences with the police, suggested they would be so. But brutality understates what the LAPD did in those years: It didn’t just brutalize black communities; it terrorized them. The terror emanated directly from the top. Police Chief Daryl Gates was a drug warrior who once said at a Senate hearing that casual drug users “ought to be taken out and shot.” In 1982, after numerous deaths of black people had resulted from police use of choke holds, Gates commented, “In some blacks when it is applied, the veins or arteries do not open up as fast as they do in normal people.” The intensifying sense of constant injustice came to a head when four officers were videotaped ruthlessly beating Rodney King in 1991, only to be acquitted when they went on trial. Two weeks after King’s beating, a Korean American grocer shot a black customer, 15-year-old Latasha Harlins, in the back of the head. The grocer, convicted of voluntary manslaughter, received probation, a fine, and community service, but didn’t go to jail.

By the time Simpson came to trial, most of the black community in Los Angeles had ample reason to view law enforcement as lacking not just credibility but basic legitimacy. Victimization fed a loss of respect for law enforcement, and that loss of respect in turn transformed victims into victimizers. The footage of the protracted beating of a white man, Reginald Denny, who was pulled from his truck during the Los Angeles riots, is chilling. But when law enforcement becomes capricious, citizens are apt to resort to their own law, rooted in ancient impulses, tribal loyalties, and vengeance.

The beating of Reginald Denny was vengeance for the beating of Rodney King. And vengeance for King played a role in Simpson’s acquittal, according to one of the jurors, Carrie Bess. But revenge only partly explains Simpson’s last great escape. What I couldn’t fathom in 1994 was a reality that black people around me likely sensed and that Made in America brings into deeply discomfiting focus: that Simpson may well have murdered his ex-wife and her friend, and that the jury got it right in declaring him not guilty. When the LAPD collared O. J. Simpson, the police force had gotten its man. The evidence all looked so obvious to a lay observer: the vivid record of spousal abuse (“He’s going to kill me,” Nicole Brown Simpson yelled to an officer who responded to one of her many calls); the bloody shoe print, which matched shoes Simpson owned; the bloody glove found at the murder scene, which matched the glove at Simpson’s home; the blood on Simpson’s car and his socks and in his bathroom.

For Johnnie Cochran, Simpson’s lead lawyer, rage against police brutality had personal roots. About his experience of being pulled over by LAPD officers who then drew their guns, he said, “I never made an issue of it. But I never forgot it.” (Lee Celano / Getty)

For Johnnie Cochran, Simpson’s lead lawyer, rage against police brutality had personal roots. About his experience of being pulled over by LAPD officers who then drew their guns, he said, “I never made an issue of it. But I never forgot it.” (Lee Celano / Getty)But juries are not merely lay observers, and the defense needed to neither wholly exonerate Simpson nor completely contradict all the evidence. His lawyers simply needed to instill reasonable doubt. The LAPD had spent decades seeding that doubt in the minds of people like those on the jury, the majority of whom were black women. To make sure the doubt was harvested, Simpson leaned on the kind of activist he’d long spurned. These days Johnnie Cochran is remembered almost in caricature, mocked on Seinfeld and derided as a race hustler. Back then, even my view of Cochran was shaped in part by the satirization of him on Saturday Night Live. Edelman resurrects a lesser-known Cochran, a hero to the black lawyers who’d been the prominent legal advocates in the fight against police brutality since the late 1960s. The New York Times called Cochran’s rage at police misconduct “all consuming.” Contrary to the portrayals of him in popular culture, that rage was genuine and directly acquired. In 1980, Cochran was pulled over by LAPD officers and instructed to get out of his car. His daughter and son were in the backseat. When Cochran stepped out, the officers had their guns drawn. The tension was defused only when the officers searched the car and found a badge—Cochran was then the third-highest-ranking official in the district attorney’s office. Cochran received a personal apology from the chief of police. “I never made an issue of it,” Cochran later wrote. “But I never forgot it.”

Simpson, who had turned his back on race men while making millions selling himself as inoffensive to middle-class white people, didn’t hesitate to empower one of them now that his life was on the line. Thus the Simpson defense team presented an ironic alchemy—an activist tradition that Simpson had rejected, fueled by funds that he’d garnered rejecting it. “O.J. had money to spend and a willingness to spend it on his own defense,” one of Simpson’s lawyers, Carl Douglas, says to Edelman. “This was a first for me.”

Whether I saw Simpson as black or not, racism pervaded his case. The role it played went beyond the evidence on display. Racism was not just blatantly revealed in the tapes of the LAPD detective Mark Fuhrman bragging about, among other things, beating black suspects, whom he identified as “niggers,” and explaining how he disregarded their constitutional rights. (“You don’t need probable cause,” Fuhrman said. “You’re God.”) And racism was not just confirmed by Fuhrman’s exposure as a perjurer who was then maneuvered into pleading the Fifth in response to grilling by the defense—including the pivotal question of whether he’d planted any evidence. Racism formed the substrate of the defense’s case: The notion that the LAPD might frame a black man was completely within the realm of possibility for black people in Los Angeles. Simpson’s legal team worked those preconceptions the way a boxer might work an opponent’s wound, relentlessly attacking the numerous flaws in an investigation and an evidence-collection process that were egregiously careless: the blanket thrown over Nicole Brown Simpson’s body, exposing it to fibers and the DNA of others in the house; the sensitive material collected bare-handed; the sample of Simpson’s blood stored in an envelope in an officer’s care and brought to Simpson’s house.

Errors that to white viewers could look like technicalities in what they presumed to be an abstractly “fair” trial tapped into fundamental questions of trust for black viewers, who saw up close a machine operated by humans striving for an ideal standard, but often falling woefully short. How many black men had the LAPD arrested and convicted under a similarly lax application of standards? “If you can railroad O. J. Simpson with his millions of dollars and his dream team of legal experts,” the activist Danny Bakewell told an assembled crowd in L.A. after the Fuhrman tapes were made public, “we know what you can do to the average African American and other decent citizens in this country.”

The claim was prophetic. Four years after Simpson was acquitted, an elite antigang unit of the LAPD’s Rampart division was implicated in a campaign of terror that ranged from torture and planting evidence to drug theft and bank robbery—“the worst corruption scandal in LAPD history,” according to the Los Angeles Times. The city was forced to vacate more than 100 convictions and pay out $78 million in settlements.

The Simpson jury, as it turned out, understood the LAPD all too well. And its conclusions about the department’s inept handling of evidence were confirmed not long after the trial, when the city’s crime lab was overhauled. “If your mission is to sweep the streets of bad people … and you can’t prosecute them successfully because you’re incompetent,” Mike Williamson, a retired LAPD officer, remarked years later about the trial, “you’ve defeated your primary mission.”