Chris Nickson's Blog, page 9

August 16, 2022

The Right Note. Or Phrase.

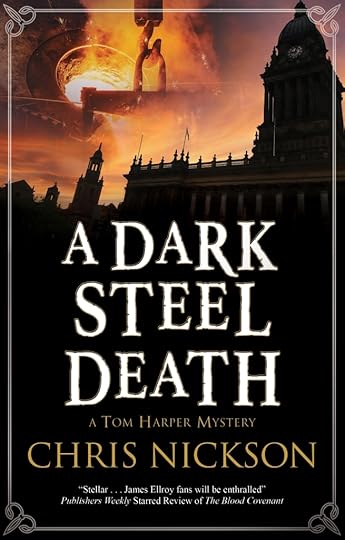

Sorry, but to start off with an aside, A Dark Steel Death is published very soon and I hope you’ll buy it or reserve a copy from your library. I’ve made another video trailer to try and convince you.

Now, on to the main feature…

When I was much younger, I looked up to musicians who could play at blistering speed. Ten Years After on Going Home? Give it to me. The flash of Keith Emerson? Oh yes – saw him live a few times, in fact. But, as I’ve grown older, I’ve learned that so much bluster often covers up the fact that technique can mean saying nothing.

Growing older, I’ve come to realise it’s the right not, and the proper silence that are more eloquent. The quietness of Bill Evans, the two notes from the late Peter Green in Fleetwood Mac that conveyed a world of hurt. The oblique, startling keyboard move of Thelonious Monk. The way Robert Wyatt allows the air into his songs.

It’s much the same with writers. I’ve come across those who overwrite, maybe caught up in language. No doubt it’s good; the critics seems to think so. But we’re all different. It wearies me, the same way that listening to an overbusy guitar solo tires my senses. The same way notes and silence serve a piece of music, not the other way round, then words and spaces are there to serve the story.

There are many kinds of writing of course, just as there are many types of music. My tastes are my own, I’m not trying to impose them on anyone. I keep trying to hack away the excess in my work and allow the story and the characters to shine through. They’re what matters. If a reader doesn’t actually notice the writing, then I’ve probably succeeded.

August 3, 2022

Saying Goodbye To Book Family

This morning I finished writing the 11th and final Tom Harper book. It’s a strange feeling to know I’m saying a final farewell to Tom, Annabelle, Mary, Ash and the others. After all, we’ve gone through 30 years together – it takes place in 1920, three decades after Gods of Gold. An awful lot has happened along the way, to Leeds, to the world, and to them. I’ve been their companion for almost a million words.

Curiously, it’s not the first time I’ve written a book with the title Rusted Souls. I completed a version last year, but even as I was working on it, I know Tom deserved to bow out on something better than this. I set it aside and never went back to it, and I know that was the right decision.

This one is the Tom Harper book I was meant to write.

It’s still only a draft. I’m going to allow it to percolate for a few weeks, go back and hopefully make it a better book – probably about the time A Dark Steel Death is officially published (although everyone appears to be selling it already, so do please get your copy or reserve it from your local library). And even then, there’s no guarantee my publisher will want it. Of course, I hope they will, to round things off neatly.

I feel sad to be saying goodbye to people who’ve been such good friends. More than that, they’ve become family. I know them so well, their joys, their sorrows and the pain they have. Strange as it may sound, I feel privileged to have been in their lives.

And please, don’t tell me they’re fictional. I won’t believe you.

July 7, 2022

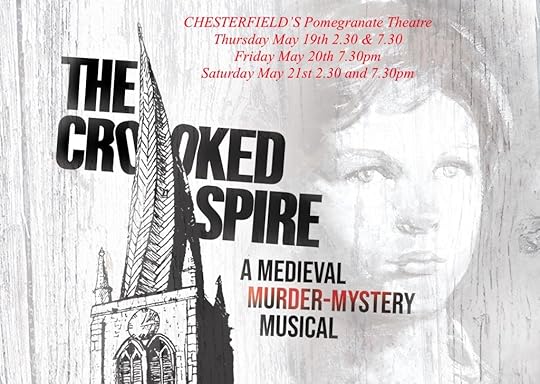

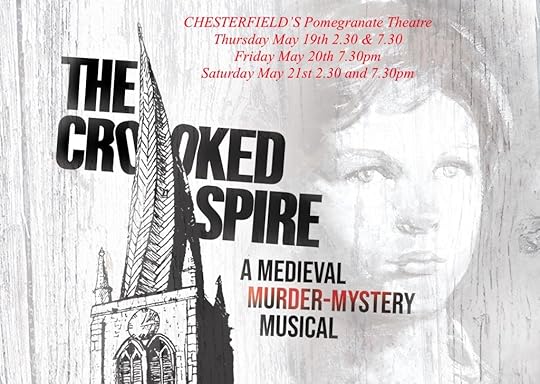

A Very Limited Time Offer On The Crooked Spire

In May, The Crooked Spire reached the stage in Chesterfield as a murder-mystery musical. Very professional produced, too. Back then, I said the company that did it has plans to make it available online.

Well, that time has just about come – but it’ll only be for a short while. From tomorrow (July 8), one of the performances of the show will be available via here for one month only. However, you should be aware that it’ll cost £8 to view. A very fair sum, given the work that so many people put into it.

If you decide to watch it, I hope you’ll enjoy it. I know that when I saw it, they did a cracking job.

June 29, 2022

My Books, My Rules

It’s about 16 years since I wrote my first published novel, The Broken Token – it took a while to find someone willing to put it out. But for some reason, I’ve remembered that I created a set of rules for myself back then. I’d read plenty of crime novels and I was tired of the loner, heavy drinking detective, and so much that went along with it.

My main character would be married. Most are. Since then, only one of my protagonists hasn’t been married on quickly on the way there. I wasn’t trying to be different, simply to reflect life. And most have had happy marriages, with or without children.

I decided that anyone could die. Again, it was simply life. People die at all ages, for all manner of reasons. Within the business of enforcing the law, there’s always a greater chance of violence. I kept that rule throughout the Richard Nottingham series (and one death brought quite a few variations on “you bastard”). I ditched it for the Tom Harper books, because conditions and life expectancy had improved in a century and a half, although things do happen, like Billy Reed’s heart attack. And the main characters have stayed alive (so far) in the Simon Westow series. I’ll say nothing else about that.

The characters have lives outside their work. We all do, and they’re often more important than anything else. They round out the people, make them human and three-dimensional. Know that and you know them and you’re even more willing to follow them.

The reader has to feel they’ve walked through the place, and experienced that time. All the sighs and smalls and noise. It needs to be alive to be convincing. It’s one reason that most of my books are set in Leeds. It’s the place I feel, that I know through the soles of my shoes. I can sense the different periods of history, like seeing through different layers of time. I can touch them, taste them. All I do is write down that move in my head, including the descriptions of the where and when.

History is important, but it’s more the local than national effect. As we grow into the 20th century, that changes, but as a rule of thumb it’s true. People cared about what affected them directly. How they lived, conditions of houses, money in their pocket. A writer needs to know their history. But to be convincing, it needs to be worn lightly. Woven into the fabric of the story so it falls gently on a reader’s shoulders. No information dumps.

Create people that readers care about. Even the second character need three dimensions. Cardboard doesn’t work.

I still try to live by all of those. But – and it’s a very big but – there also has to be a good, powerful story that will engage people. That’s at the heart of it all.

I try, but it’s only you, the readers, who can say if I succeed.

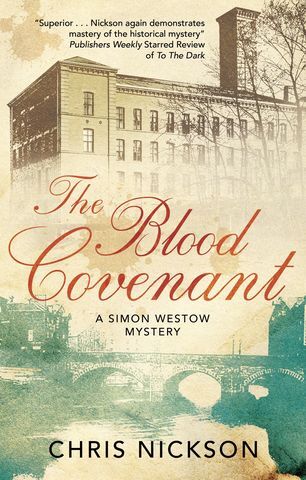

To finish, please indulge me while I ask a favour. My most recent novel, The Blood Covenant, has had the types of reviews a writer can only dream about. The one coming in September, which isn’t far away now, is very good, the 10th Tom Harper novel. Yes, I’d love for you to buy them. Ideally from an independent bookshop, but outlets like Speedy Hen and the Hive in the UK have excellent prices and free postage. Like everyone, though, I know we’re all squeezed and books are a luxury. If you can’t afford it, please order from your local library. If they don’t have it, they will get it in. If every library system in the UK, US, Canada, Australia and NZ ordered copies of both, it would be handsome sales figures. And it would be on the shelves for everyone to read.

Even if you can afford, please consider the library request – that way it’s there for others.

Thank you.

If you have some time to spare – quite a bit of time – I was interviewed for the Working House podcast. You can listen here.

June 14, 2022

A Dark Steel Death – The Video

Leeds, December 5, 1916

The car slid quickly through the streets. Deputy Chief Constable Tom Harper stared out of the window. Leeds was black, a wartime winter-darkness, barely a single thin sliver of light showing through the blackout. A quarter of an hour before, he’d been comfortably asleep in bed, until he was torn out of a dream by the telephone bell. As he hurried to answer, he wondered if it was finally happening: the Zeppelins had come to attack Leeds.

No. This was worse. Far worse.

He could see the fire from half a mile away. Flames licked high into the sky. A moment later he smelled the hard, overwhelming stink of cordite.

‘Duty sergeant, sir.’ He’d had to press the receiver against his good ear to make out the words. The man’s voice was flat, empty of expression. ‘Our officers at Filling Station Number One rang in. There’s been an explosion. A car is on its way for you.’

Filling Station Number One. Everyone around here knew it by a different name – Barnbow.

The book is out everywhere, hardback and e-book, in September. You can pre-order it now.

May 30, 2022

Fancy Something New?

I’m not quite sure what this is going to be come. The working title is When The Music Stops and I have around 10,000 words written. One this is certain – it’s not a crime story. Set in 1930s Leeds, with some inspiration from my father’s own life.

Here’s a little bit. I hope – I really do hope – you’ll tell me what you think. Meanwhile, I hope you enjoy.

Leeds, March 1935

Bramley swimming baths had been made over. The local pool was closed each winter and covered with layers of heavy boards, so the council could use them for Saturday night dances, with the stage at one end for the musicians. A hand-lettered sign announced The Mark Sharp Sextet.

The bus had been late. The band had been forced to dash from the stop, carrying Billy Dobson’s drums in their cases. He was setting up now, nailing down the bass drum to stop it travelling as he kept the beat. The caretaker started to object, but Mark talked right over him.

‘You’ve got a choice. It’s that or he’ll be all the way out the door by the second number and you’ll have a riot on your hands.’ He shrugged and glanced towards the crowd, pressing around and murmuring, eager for things to begin and get full value for their shilling admission. ‘Up to you.’

‘I suppose,’ the caretaker agreed grudgingly. ‘You lot just make sure to clean up after yourselves later, mind.’

One small victory, Mark thought. Now all he had to do was win over those people who were waiting. They’d expect their money’s worth. If you didn’t give them what they wanted, they wouldn’t come back. Half the country was on the dole, and every penny was tight.

He’d prepared the running order of songs during the afternoon. A good mix of pace. Plenty in there that was familiar, one or two that were new, and a few chances for a quiet smooch on the floor.

‘Why don’t we start with Midnight instead of What Did I tell Ya?’ Will the trumpeter asked quietly. He was older, experienced, someone who’d spent the last five years playing in groups around Leeds. ‘Give them a gentle introduction instead of jumping in.’

Mark shook his head. ‘We’ll stick with this. Look at them, they’re ready. They’ll be dancing in a flash.’

Thirty seconds into the song and he saw he was right. The crowd was moving. Will gave him a nod and a rueful smile.

Give the people what they want, Mark thought. That was the secret.

An hour later, the final notes of Smoke Gets In Your Eyes drifted up towards the ceiling. Dancers who’d been clinging tight to each other parted and began to applaud. Five more seconds and the band had vanished, off to talk to women they’d been eyeing, smoke a cigarette or find a bottle of beer. Mark remained on the piano stool, lighting a cigarette and smiling to himself. Not a bad set. The crowd had loved it. He watched the faces, smiling, happy to be out somewhere. Couples, singles, even a family over by the far wall.

He stubbed the cigarette out in the ashtray. His left hand began to move across the keyboard, tracing out the melody in his head. The instrument was an old, battered upright, the ivory keys turned tobacco yellow, but it was loud and in tune. A few vamped chords, then his right hand added some tentative little lines, poking and prodding.

This was the time of the evening he relished. The chance to simply play, letting his mind and his fingers wander. It was always the same; while the others rushed away on the break, he stayed on the bandstand and played. Gave them a little jazz. Doodling, Will called it, with a shake of his head. Mark didn’t care; this was his time. Sometimes, when he hit it just right, people would gather round the piano, caught up in the music. He’d pick them up and carry them along with him. Those were the moments. That was the magic.

Not tonight, though. Two minutes and he stopped. His inspiration was lost in the bustle of conversation all around. For a moment he thought a brunette might be staring his way, but she turned to talk to her friend. He laughed to himself.

If you haven’t read it yet, The Blood Covenant has been out since the end of last year, and I’ve received the best reviews of my career for it. If your library doesn’t have it, ask them to buy a copy. Or you can buy one yourself, if you can afford to.

May 24, 2022

When The Music Plays In Chesterfield

All too often I’m amazed at the things that have happened because I started writing historical crime novels. Things I could never have anticipated or imagined. I’ve helped with an exhibition, The Vote Before The Vote, that showcased the 19th century Leeds woman who worked towards a proper franchise. I was commissioned to write a play about Dark Briggate Blues’ Dan Markham by Leeds Jazz Fest, and ended up with something that included a live jazz quintet and sold out two performances. I’ve become the writer-in-residence for Abbey House Museum in Leeds.

But Saturday was perhaps the most surreal experience of them all. I was in Chesterfield for the matinee performance of The Crooked Spire, the murder-mystery music that had been made from my novel set in the town in 1360.

Full disclosure. I’m not a fan of musicals, so I approached this with a degree of trepidation.

But it was outstanding. A very professional production, with full credit to all the backstage people who helped make it that way, A superb band that was always spot-on. Wonderful direction and production, a great set and costumes.

Of course, it’s the actors that we see and hear. They were great. The audience loved it. So did I. I knew it wouldn’t quite be my book on the stage, and it wasn’t. It would have felt wrong if it had been. This told its story beautifully. Some of the songs were quite transcendent and deserve a life beyond the five performances of the run. I hope they have that chance.

After the show, I took part in a Q&A with the director, musical arranger, set/costume designer, script writer, and producer, and felt embarrassed when many of the initial questions were for me. After all, the others were the ones responsible for what they’d just seen. But at the end, when people came up and brought out copies of the book or their programmes for me to sign (one man had his autograph book, his “memory book” as he called it), I was moved. Dumbfounded.

The Crooked Spire had gone beyond anything I’d envision when it was published nine years ago. It’s grown far beyond me.

I’m told that the performances were recorded and something will be available online soon. I’ll let you know.

Strange things happen when you write, and some of them are wonderful.

May 18, 2022

Tom Harper And A Dark Steel Death

It’s not that long since The Blood Covenant was published, and I still firmly believe e it’s the best book I’ve put out…so far.

But A Dark Steel Death is coming to give it a run for its money in September. It’s the 11th Tom Harper novel, set in Leeds in 1917, the grimmest days of the Great War.

What’s it about? Sabotage, traitors…perhaps. The story isn’t as straightforward as that. Here’s a short extract from somewhere near the beginning for you to read and whet your appetite.

It’s available to pre-order from all the usual sources, but here is the cheapest, with free UK postage. However, please, do give your business to indies if you can.

Oh, keep scrolling after the extract to see the cover. It’s a cracker.

He was starting to believe that he lived in a world made of paper. It never ended: the correspondence from the War Office, the Home Office, the watch committee, divisional heads . . . the minutes of all the meetings. It was probably all important. But Tom Harper felt as if it had nothing to do with coppering. He’d cleared his desk yesterday, starting the week with good intentions. Now it was Tuesday morning and he knew he’d be buried under another blizzard of paper.

For the last month things had been worse: Chief Constable Parker had been on sick leave with pneumonia. A week in hospital, but now he was recovering. It was a slow process; he wasn’t likely to return before March. And that meant Harper was stuck with two jobs.

He pulled out his watch and opened the cover. Quarter to seven. Hardly light yet outside. With luck, he’d have the next fifteen minutes to himself. It might be all he’d manage in the days that began and ended while it was still dark.

Then the telephone rang.

‘We have trouble, sir.’ Superintendent Ash. His voice was immediately recognizable, even turned hard and metallic on the line.

Harper tensed. ‘Why? What’s happened? Is something wrong at Millgarth?’

‘Not here, sir. It’s the army clothing depot. You remember they took over the old tram sheds and the King’s Mill next door to it back in 1914?’

Harper felt the shiver of fear crawl up his spine.

‘Yes, of course.’ He’d been part of the group invited to tour the buildings before they opened. Ton after ton of garments sorted, inspected and bundled every week before they were sent off to the soldiers. A gigantic operation.

‘Two hours ago, the night watchman was making his final round at the mill.’ Ash paused, considering his words. ‘He thought he heard someone dashing off, then he found a box of matches and some torn-up newspaper in a corner. Came straight outside and reported it to the bobby on guard. His sergeant started the constables searching, then he rang me.’

Christ Almighty, someone starting a fire in a place like that, filled with clothes . . . the place would be an inferno before anyone could stop it.

‘I’ve had men going through the place from top to bottom, sir,’ Ash continued.

‘What have they found?’ He was gripping the instrument so tight that his knuckles had turned white.

‘Nothing, sir. I’ve had them search that other depot on Park Row with a nit comb, too. It’s clean. That’s where I am right now.’

Sabotage. It couldn’t be anything else. The thoughts roared through his head, hammering hard against his skull.

‘I’ll be there in five minutes.’

‘Yes, sir. I haven’t informed the army yet.’

‘Leave that to me,’ Harper promised. ‘I want someone vetting the records of everyone who works in those places,’ Harper said.

‘Walsh is already on it. One of the new detective constables is helping him.’

He thanked God that Walsh was too old to go and fight. Twice he’d tried to join up; both times he’d been turned away at the recruiting station. Just as well; they needed experienced men like him to stay in the force.

His secretary was hanging up her coat as he rushed out.

‘You have Inspector Collins at eight,’ Miss Sharp told him.

‘Tell him I’ll try to be back by nine.’

His mouth was dry and his heart beating a terrified tattoo in his chest as he dashed down Park Row. Another raw winter’s day, coming on dawn, the morning sky pale and mottled with high clouds and a thin north wind. He could have been a businessman hurrying down the street to his office, buried in his overcoat and hat. But he had more important things on his mind than profit and loss. Barnbow last month, and they didn’t know the cause yet. Now this.

Leeds had a saboteur.

And the police needed to stop him.

Ash was waiting outside the warehouse. He was still a big, brawny man, but with the years he’d acquired plenty of padding. His belly jutted under the waistcoat and his neck had grown thick and fleshy. With his white hair and lined face, and the spectacles perched on his nose, he’d come to look like an old, wise man. Time had left its mark on him, but it had on them all. By rights, he and Harper should both have been put out to grass by now. But with so many good men, younger men, gone to war, they were needed. And they were working longer, harder hours than ever before.

‘The army will be here in a moment,’ Harper said, and nodded at the staff car racing along the road.

Brigadier Fox looked too young for his rank, barely forty, but Harper knew he’d earned it, gunned down twice in no man’s land and patched up before going back to the trenches. Now permanently back in England after a third wound left him needing a stick to walk. These days he supervised the garrison at Carlton barracks and was in charge of security at the facilities in Leeds. A war hero and his men loved him for it.

‘Brian,’ Harper said as they shook hands. ‘This is Superintendent Ash. You can trust him with your life. I have.’

A nod and a smile, then Fox’s expression turned grim. ‘What are we going to do about this? We need to discover who’s behind it before he has chance to do any damage.’

‘Increase the patrols every night,’ Ash suggested. ‘Vary the times, so there’s no routine.’

‘Nobody in or out without proper identification,’ Harper added. ‘Search everyone. No matches or cigarette lighters allowed inside.’

The brigadier opened his mouth as if to object, then stopped.

‘Yes,’ he agreed. ‘All sensible. We’ll do that. I’ll post a couple of armed sentries at each of the other places.’ He gave a sad, twisted smile. ‘A rifle and a bayonet can scare people off very effectively.’

The staff car took them to the clothing depot on Swinegate. The building was faceless, anonymous, the stone black with decades of soot. Royal Army Clothing Depot was stencilled across the wide double gates, the letters beginning to fade.

The old watchman, a worried, defensive fellow with patches of white stubble on his cheeks, stared down at his boots as he told his story once again.

May 10, 2022

The Crooked Spire, Coming Next Week

The music made from my book, The Crooked Spire, set in Chesterfield in 1360 is set to open next week, and very aptly, it will be in Chesterfield.

You’ll probably have come across me rabbiting on about it, but yes, it’s a murder-mystery musical. Unlikely, I know, but from the little I’ve seen, it works.

Last month, some of the cast went out in town and performed some of the songs and tunes. Yes, they are in costume.

Rehearsals are underway, as you’d hope. Here are some of those actors and behjind the scenes people talking about the show.

Finally, for those who’ve never had chance to visit Chesterfield, one of the cast takes you up in the tower and gives you a glimpse up into the spire. Remember, it’s only held on by its own weight.

I’ll be there for the Saturday matinee – I’m eager to see it – and I’ll be taking part in a Q&A afterwards. You should probably come along.

April 5, 2022

The Whispers – A New Richard Nottingham Story

I did warn you that a new story with Richard was coming. It’s been a long time since I walked the streets in Leeds beside him. Too long, really.

This is a little different. But he’s changed, he’s a bit older. Yer, underneath, the man we know is still very much there. I hope you enjoy a few minutes in his company.

Leeds, March, 1738

Richard Nottingham stood on Leeds Bridge, hands resting on the cold stone parapet. The wind whipped along the River Aire, down from the hills, the water carrying the stink of waste from the dyeworks and the fulling mills. Swirls of red and blue eddied by the shore. The body of a dog or cat, caught up in a branch and pulled downstream.

He watched a barge dock on the wharf near the bottom of Pitfall. Ropes thrown to shore, wrapped and knotted around bollards fore and aft. As he looked, he listened to the whispers of the ghosts in his ears. His wife Mary, his daughter Rose, and John Sedgwick, who’d been his deputy in the times when Nottingham had been Constable of Leeds.

Those days were long past. Now it was Rob, his son-in-law, who held the post. Nottingham was glad to let it go. He’d grown too old, his body weary from all it has endured when he was in office. He had his house on Marsh Lane, his ragtag family. That was enough.

From the corner of his eye, he noticed a man come slide the corner of a warehouse, trying hard to stay unnoticed in the shadows. Lank hair, stoop-shouldered, wearing an old, stained coat and dirty hose.

One of the barge hands jumped off the boat and began to walk along the wharves. The other man followed. Thirty yards away they huddled together. The barge man brought out a small packet from the deep pocket of his coat. The other man stared around again, making sure they weren’t watched, before he handed over a small purse.

It was over in a moment, then the two men were talking and laughing like old friends. It could be nothing, Nottingham thought, perfectly above board. Aye, he heard Sedgwick say, and if you believe that I’ll sell you this bridge, boss. Summat’s going on.

He stood straighter, and suddenly the two men saw him. One pointed and the began to take a path up to the Calls that would bring them out close to the bridge.

It was time to move.

He often used a stick to help him walk; it has been useful for the last year. This time he carried it. He’d be too obvious, and it might make a useful weapon.

A short distance and he’d disappeared into the throng of merchants and weavers crowed around the trestles on either side of Briggate. The Tuesday morning coloured cloth market, everyone bringing their woven lengths from the villages around Leeds to be sold. He’d known ritual this all his life, grown up with it, kept order here. He could move in and out and become invisible as he moved along the street.

Nottingham had battered his tricorn hat, but so did many others, and his buff coat hardly made him stand out.

Go to the jail, Richard; that was what his wife told him. He could hear every small inflection of her voice as it whispered in his head. Leave it for Rob to handle. It’s not your job. It’s not your fight. Don’t take any risks, please.

You’re right, he thought, you’re right. This has nothing to do with me now. But he’d seen something. Every scrap of experience told him the men were breaking the law. To make sure it was obeyed was everyone’s duty. He’d pass Rob the word and let the younger man fight the battle; after all, he was Constable of Leeds.

The market was hushed. By tradition, all the deals were made in whispers and sealed with a handshake. But the inns were loud as men and women drank and spent their penny ha-penny on a Brigg-End shot. He made his way past the crowds with nods to the faces he knew. So many, he thought. Are you surprised? Rose asked. You’ve served these people for years, Papa. They respect you. They always have.

Or maybe he was just too familiar.

Nottingham kept a steady, comfortable pace up Briggate, watching for the men he’d seen. In the cloth market, he was just one figure among many. But as he reached Kirkgate, the bodies thinned out and he hurried down the street to the jail, looking over his shoulder.

He spotted one of them, the barge man, father down the street, talking to a man behind a trestle. He was gesturing wildly, anxious, while the other shook his head. Getting nowhere and growing frantic. Now Nottingham was certain he’d seen something criminal. Where was the other man?

He turned the corner, by the entrance to the White Swan, and saw him. Standing, turned towards him, just feet away.

Be careful, Richard, Mary told him. His heart was beating fast, thudding in his chest. He tightened his grip on the stick. This isn’t your fight, she whispered. No, it wasn’t, but he was part of it now; he couldn’t avoid it.

Watch him, boss. Sedgwick’s voice, ready, quietly assessing everything. You see the way he’s standing? Yes, he could see. The man favoured his right leg. Hit that left knee, boss. Do it quick and hard and he’ll be on the ground. No need to worry about him after that.

Nottingham gave a thin smile. He knew he looked like an old man, one who wouldn’t put up a fight. A victim. But he’d learned all the ways to give much more than he took.

The man grinned, happy to have found his quarry so easily. He let his eyes play the trick on him, seeing what he wanted, a man he could beat, and he started to charge.

So easy that an invalid could have done it. A step to the side, the crack of wood on the bone of the kneecap and the man was rolling in the road, clutching his leg and howling.

Nottingham opened the door of the jail. Rob Lister was sitting behind the desk, head bent as he wrote. He looked up, suddenly curious as he saw Nottingham.

‘There’s someone out here you should meet.’

A small crowd had gathered, standing around the man in pain, but none of them moved to help him.

‘Who is he?’ Lister asked.

‘No idea.’ He summed what had happened in three sentences.

Rob searched through the man’s pocket and pulled out a knotted kerchief. Inside he found tiny silver cutting from the edges of coins.

‘Coin clipping. Whoever he works for will melt them down.’ The man was struggling to edge away. Lister put a hand to his collar and hauled him to his feet. ‘A cell for you, and some questions. You know all this is treason?’ He gave a dark grin. ‘Takes you straight to the hangman’s dance.’

He pulled the man away before he could answer.

You did well there, boss. Not really, he thought; it wasn’t so hard. But there’s still another of them looking for me.

Papa, no, please. Listen to Rose, Richard, his wife said in his ear. She’s right. You were lucky once. The next time…

But what was the worst that could happen? He’d leave some people he loved, ones who could look after themselves, and he’d be with others. See his wife again, as sweet as the day they married at the Parish Church.

‘Do you want to see if we can find this other one?’ Rob said. He had a sword buckled to his belt, hand resting lightly on the hilt. ‘Will you be able to recognize him?’

‘Why don’t we let him find me,’ Nottingham answered. ‘He’s going to be desperate by now. Let me go ahead. Just keep a close watch.’

Richard…Mary began. But this was duty; after all these years, she’d understand that.

A wander down Briggate towards the bridge and the river, looking like he didn’t have a care in the world. Pausing to exchange a few words with the merchants and the clothiers, flush and happy from selling their cloth.

The bell had rung to end the market a few minutes before. Now the voices were raised, the taverns full to overflowing, spilling out on the street.

Nottingham spotted the barge man. He had the build of someone used to carrying heavy weight, broad shoulders and thick arms. Richard made a sign, trusting Rob would see it.

Carts and wagons were moving up and down the road. He crossed between them, parading himself for the man to see.

Don’t, Papa, rose said. Point him out to Rob. But he’d started the job he had to- No, you don’t, Richard. You left all that, Mary told him, and he smiled. He’d left it, but someone it refused to leave him.

He’s seen you, boss. He’s coming.

Good. Let him come. He trusted Rob

He’s close, Papa. Just three yards behind you now.

He’s taking out his knife, boss.

Nottingham stopped and turned. The man was no more than six feet away now, a body’s length, with a look on his face somewhere between panic and triumph. He had the knife in his hand, fingers tight around the hilt.

‘Don’t.’ One word, but it took the man by surprise.

‘Why?’ A guttural voice. He sounded Dutch, perhaps, maybe German.

‘Because I said so.’ Rob slid up behind the man and put his blade alongside his neck. ‘Drop your weapon.’

Nothing, and the pressed the metal against the throat until the knife clattered on the floor.

‘He’s the constable here,’ Nottingham explained. ‘I used to have to honour.’

‘Which pocket, Richard?’ Lister asked.

‘The right, I think.’

‘Take a look, will you?’

The purse was there, bulging.

‘You and your friend are going to like Jack Ketch. You’ll meet him at the assizes in York. He does good work. Quick, clean.’

Later, in the churchyard, he stood by the graves and listened to the dead whispering. John Sedgwick, Rose, even Amos Worthy, the man he’d liked and hated in equal measure. All of them with words for him.

But it was Mary who waited until the others had finished. Richard, you always were a fool. You don’t anyone a duty now. You owe yourself a life. For Emily and Rob and Lucy and young Mary. Don’t you want to see her grow?

No need to reply. She knew the answer.

I love you, but you don’t need to come to us. We’re with you, always. Wherever you are, my love. Wherever you are.