Chris Nickson's Blog, page 12

June 29, 2021

Alice Mann: A Forgotten Woman Of Leeds

As a novelist, one of the things I’ve tried to do is give a voice to the voiceless in Leeds, and to celebrate those who made a difference to people in this town. It’s why one of my proudest achievements was to be associated with The Vote Before the Vote exhibition in 2018, celebrating local women who worked toward the vote during the 19th century.

One woman who should be known and lauded round here is Alice Mann. She was a radical bookseller and printer. The newspapers and magazines she sold and some of the pieces she printed did what I admire: raised the cry of those who usually went unheard. She stood up for her principles; she even went to prison for them.

Yet most people have never heard her name.

We do we know about her?

She was born Alice Burnett on Hunslet Lane in 1791, and her father’s name was William. There’s no trail to follow for him, and Alice’s mother isn’t named.

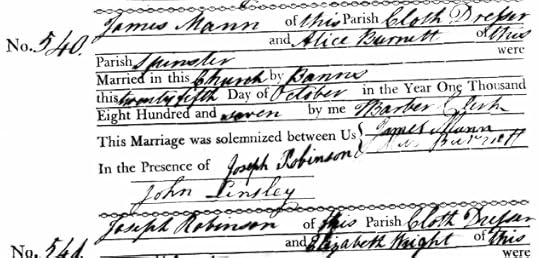

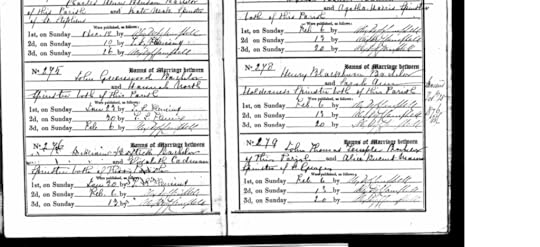

In 1807 she married James Mann at Leeds Parish Church.

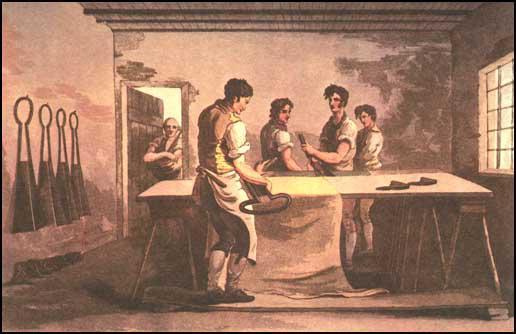

Who was James Mann? Born in Huddersfield (or possibly Leeds, on Briggate) in1784, he was employed as a cloth dresser, a man who cropped the finished woven cloth. It was a skilled trade that paid a handsome wage; the croppers had to wield large shears and do their work with concentration and exactitude -and great arm strength. The croppers were among the elite of cloth workers.

Becoming Radicals

The job of cropper was dying. Machines were coming in that could do the work faster and cheaper. This was the time of the machine breakers, the Luddites. Men who wanted to stop industrialisation. It was a forlorn hope. The gates had opened and the flood was coming. But it gave rise to broader issues that would result in Chartism later in the 19th century.

By 1812, the couple were apparently Radicals. They were reputedly involved in a riot on Briggate, where the market was held every Tuesday and Saturday.

England was in the middle of its war against Napoleon. The price of corn (wheat) kept rising and rising, with no check. Bread was a staple food and people couldn’t afford it.

The Manns possibly organised the riot, encouraging people to take the the food. Alice might had led it all, dressed up as “Lady Ludd.” Others claim it was James in a dress. A report in the Ipswich Journal claimed that on August 18:

In the afternoon [in Leeds] a number of women and boys, headed by a female who was dignified with the title of Lady Ludd, paraded the streets, beating up for a mob.

In 1819 the Manns opened a bookshop on Briggate. That was the year of the Peterloo Massacre in Manchester, and government fears over agitation for reform. By then, the Manns had a reputation. The Leeds Intelligencer claimed that their “house appears to be the head quarters of sedition in this town.”

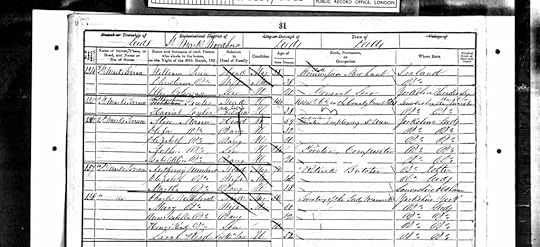

James was a speaker on parliamentary reform, and also an advocate of female reform societies. In 1820 he was successfully prosecuted under the new Six Acts for sedition. While he was travelling around West Yorkshire, Alice apparently kept the shop and looked after the nine children the couple would eventually have (six are listed in the 1841 census, ranging from 23 to 11, along with another child and a lodger).

In 1832, cholera swept through the country. It killed James Mann on August 2, and he was buried at Mill Hill Chapel – apparently a convert to Nonconformism.

The Second Act

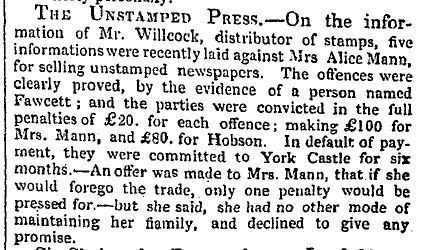

Alice still had a family to raise. She needed the bookshop more than ever, and began working with Joshua Hobson, another Radical journalist/printer/bookseller, who moved to Leeds from Huddersfield. He published Voice of the West Riding, and was prosecuted three times for selling an unstamped newspaper.

He set up in business on Market Street – about where Central Arcade is these days – and became active in politics in the town. Alice, meanwhile, had also been in court for selling unstamped papers. In 1834 she ended up being sentenced to seven days in the House of Correction in Wakefield. Two years later she was offered a deal where most of the charges would be dropped if she agreed to stop selling unstamped papers. She refused, saying selling books and papers was her only way to support her family. She was sentenced to six months in prison at York Castle. According to the Leeds Intelligencer, a public dinner was held up on her release.

She’d moved premises from Briggate to the new Central Market on Duncan Street, and lived in Trinity Street (or Court, according to the trade directory).

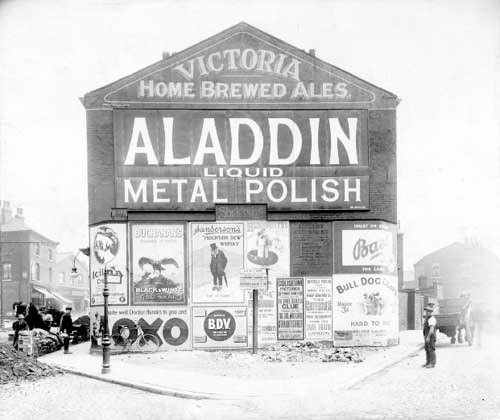

Central Market (Leodis)

Central Market (Leodis)

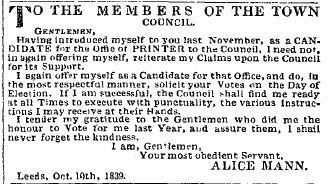

As a jobbing printer, she took on whatever jobs came her way, and repeatedly tried to become printer to the council, a lucrative position, which she won in 1842.

By the 1851 census, she and her family were living in Woodhouse. One blogger has speculated she might have been the author of The Emigrant’s Guide (you can read the piece here), published in 1850. It’s possible, although the evidence is scant. But she had to make a living.

However, she remained true to her roots, supposedly becoming printer of the Leeds Times after its 1839 sale. She was responsible for publishing The Ten Hour Advocate and Mann’s Black Book of the British Aristocracy, among a number of others.

Although any contributions she made haven’t been unearthed, she was almost certainly involved in the Chartist movement in the 1840s, which was strong in Leeds (where the Northern Star newspaper was published).

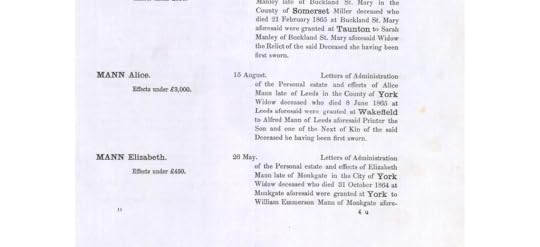

The only other facts are that she died on June 8, 1865, and left an estate worth less than £3000. It was administered by her son Alfred, who he carried on the business.

The listing for Alice Mann’s death

The listing for Alice Mann’s death

However, in 1876, a woman named Alice Burnett Mann married John Temple.

Who was Alice Bruneett Mann? One explanation is that in 1891, a child named Gertrude Temple was living in York with Henry Mann and his family. Gertrude was listed as Mann’s granddaughter. Henry Mann was one of the children of James and Alice Mann.

At a time when few women ran their own businesses, Alice kept hers going very successfully after her husband died. Equally rare, she was a woman involved in Radical politics in a period when it was a dangerous business, and raised a family on her own. A remarkable woman – one who deserves to be better-known than she is.

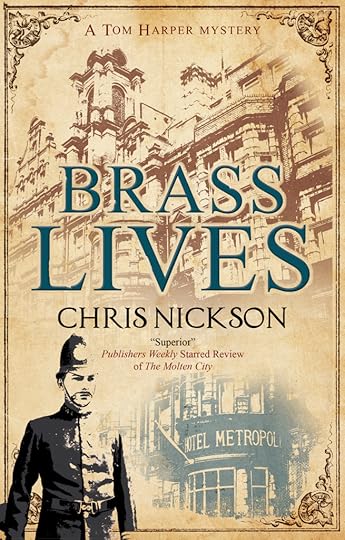

To finish, a reminder that Brass Lives is now out in hardback in the UK, and ready for you to buy or borrow from a library (ask your library – they’ll order it). The ebook will be available worldwide from August 1, and the hardback from September 7.

Some information for this piece came from posting to the Secret Libray website and David Thornton’s essential (to me) Leeds: A Biographical Dictionary. I’m grateful.

June 16, 2021

The Bold Escape Of The Suffragette

As you’ll almost certainly be aware by now, my new book called Brass Lives is published next week.

While one of the main characters is based on the real-life Leeds-born gangster Owen Madden, one small strand features another real person – suffragette Lilian Lenton. She was in Armley Gaol on Leeds, accused of arson in Doncaster. On hunger strike, she was released under the Cat and Mouse Act. The idea was she’d eat and gain weight, then be hauled back to prison.

However.., in the book, Special Branch is watching her. Let’s say it’s not a success. What I’ve described seemed to be what really happened.

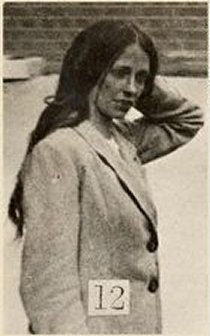

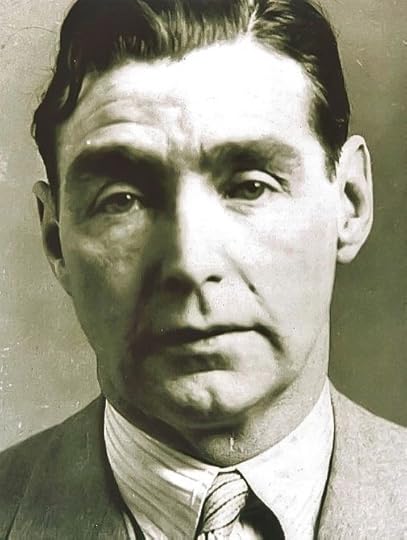

Lilian Lenton

Lilian LentonFriday morning, half-past eleven. Harper sat in the chief constable’s office, listening to Inspector Cartwright of Special Branch. Beside him, Sergeant Gough’s face was so red with anger that he looked as if he might explode.

‘None of my men had seen any sign of Miss Lenton, so I knocked on the door first thing this morning and asked to see her. I wanted to know if she was well enough to be returned to Armley Gaol.’ Cartwright spoke as if he was reciting from his notebook in court.

‘Go on,’ Parker said. He clamped down on the cigar in his mouth to hide his amusement.

‘The maid told me that she wasn’t there. My men searched the house from top to bottom and the information was correct. She was not there.’

Parker studied the rising smoke. ‘Have you discovered what happened?’

‘She escaped, that’s what happened.’ Gough was close to shouting.

Harper raised an eyebrow. ‘How?’

‘As best as we can ascertain, sir, she was in disguise,’ Cartwright continued, avoiding their eyes as he stared at the wall. ‘She arrived on the Tuesday. Late that afternoon a delivery van appeared on Westfield Terrace. It was driven by a young man. He had a boy with him. We observed the boy eating an apple and reading a copy of Comic Cuts. The driver called out “Groceries.” A servant opened the door and said, “All right, it’s here.” The boy took a basket into the house through the back door.’ He went silent for a moment, glaring at the sergeant. ‘Shortly after that, the delivery boy reappeared with an empty basket, returned to the van and it drove away.’

‘The delivery boy who came out was Lilian Lenton in disguise?’ Harper asked.

‘Yes,’ Cartwright said through clenched teeth. ‘That’s what we’ve managed to discover. I talked to the grocer. He told me everything as soon as I threatened him with prosecution. Miss Lenton was taken a mile away to—’ he consulted his notebook ‘—Moortown, where her friends had a taxi waiting to drive her to Harrogate. We’re pursuing our enquiries from there. At this point we have every reason to believe she’s fled the country.’

‘That’s very unfortunate,’ Parker said. ‘And it makes the Special Branch look pretty poor.’

‘Yes, sir, it does.’ Cartwright was staring daggers, but he had to sit and take it. His men had messed up. They’d allowed the woman to escape as they sat and watched. ‘You can help us, if you’d be so good.’ He looked as though they were the hardest words he’d ever had to speak.

‘What do you need?’ Harper asked.

‘If you could ask the force in Harrogate to talk to people they know and discover where she’s gone, that would be a great help. The sooner we can find out the better, of course.’

‘We will.’

‘Thank you, sir.’ The men stood.

Before they could leave, the chief said: ‘A word to the wise, Inspector. I’d advise you not to prosecute the grocer. If this comes out in court, you’ll look an utter fool.’

Brass Lives is published June 24.

June 1, 2021

Three Weeks To Go

Yes, as June arrives and summer really seems to be here – 23C yesterday and the allotment is grateful! – the times is paxssing quickly. In just over three weeks, Brass Lives will be published in the UK (ebook everywhere on August 1, and US hardback publication in September, I believe).

It’s the first time I’ve used a real, well-known person as the foundation for a major character, and given his life the kind of turn it never had.

Who? A Leeds-born man who moved young to New York and become notorious as a gangster and bootlegger – and as a killer. Owen Madden. Here’s a short film I made about him in my other role as writer-in-residence at Abeey House Museum. He really is a fascinating person.

My version of him, Davey Mullen, is a little different.

Why not read it and find out? This place has the cheapest price, and free shipping (and they’re not Amazon).

May 25, 2021

An Excerpt From Brass Lives

It’s just four weeks until Brass Lives, the ninth Tom Harper novel, is published. Set in 1913, it features Davey Mullen, who was born in Leeds but moved to New York as a child. Now 21, he’s a gangster, a killer, recuperating from an ambush in Manhattan, where he was shot 11 times and left for dead.

Mullen – based on a real figure, Owen Madden – is supposedly back to visit his father, who remained in Leeds. The New York police have warned Leeds, and Tom, now Deputy Chief Constable, has uniforms tailing Mullen. But he’s still surprised when the man shows up at the Victoria one night…

He’d finished his supper and poured the last cup of tea from the pot when Dan the barman came up the stairs to the parlour.

‘I’m sorry to bother you, Tom, but there’s a man downstairs asking for you.’

That was unusual; people rarely sought him out at home. ‘Not one of my lot, is it?’ he asked. Maybe they’d found Fess. No, couldn’t be, Harper thought; they’d have telephoned.

‘This one’s definitely not a copper.’ Dan frowned. ‘You ask me, he’s got the smell of crime about him. Young and big. Talks strange, too. Like he’s from Leeds but with something else on top that I don’t recognize.’

Harper gave a grim smile. Mullen had decided to come to the Victoria.

‘Thanks, Dan. I’ll be down in a minute.’

Annabelle was watching him. ‘You know who it is, don’t you?’

‘I can take a good guess. It’s that man I told you about, the one from New York. Mullen.’

‘The one who’s killed people.’

‘Yes.’

‘Here. In my pub.’ She glared and started to rise.

‘Give me a minute before you come down,’ he asked. ‘Don’t worry, I’ll make sure he doesn’t cause any trouble.’

‘He’d better not.’

Mullen was sitting at a table with his back to the wall, a pint of beer in front of him. He had the handsome, dark Irish looks that he’d shown in his police photograph, wearing an expensive grey suit that fitted him flatteringly, with a soft collared shirt and a brilliant red silk tie fastened with a gold pin. Flaunting his money in his clothes.

He sat with his legs crossed, shining black shoes catching the light, looking at faces and assessing their eyes for danger as Harper settled across from him.

‘You’re safe enough in here. From the customers, at least.’

A dip of the head in acknowledgement.

‘This must be different from the places you’re used to at home,’ Harper said.

Mullen grinned and showed his good, even teeth. ‘A bar’s a bar, doesn’t matter where you put it. Sláinte.’ He took a long drink of bitter. ‘I’ll tell you this, though: the Americans have a long way to go before they can brew beer like the English.’ He stared at the glass. ‘And Leeds is home, after a fashion.’

‘Some parts of it might be. But not this place. What brings you out here?’ Harper’s voice was sharper, his face hard.

‘A man told me that you lived above a public house. I was curious to take a look and see what kind of deputy chief constable would do that. Anyway, it’s only a short stroll from Somerset Street. Perfect for a summer’s evening.’

Harper saw the man’s gaze shift and his smile broaden.

‘This is the woman who owns the public house,’ he said.

‘Mrs Harper.’ Mullen stood. For the briefest moment, he looked awkward and self-conscious, as if he wasn’t quite sure how to act around a woman. ‘A pleasure to meet you. You have a very welcoming pub here.’

She sat, never taking her eyes off him. ‘Are you enjoying your visit to England, Mr Mullen?’

‘I am, ma’am. I’m enjoying being back and seeing my father again.’ Dan was right, Harper thought; there was still a definite trace of Leeds in his voice, somewhere deep in the bedrock. But much of it had been overlaid by the nasal New York cockiness. ‘I got to say, it’s changed a lot in ten years.’

‘How is your father?’ Harper asked, as if he hadn’t seen a report on Francis Mullen just the day before. The man spent the better part of his time drunk. He’d been kicked out of two beershops for trying to start fights.

‘Happy to see me,’ Mullen replied after a moment.

‘I don’t know if you’ve heard, but there’s another American in Leeds at the moment. Someone called Louis Fess. He’s from New York, too. Maybe you know him.’

He’d dropped the name drop to see Mullen’s reaction. It was a pleasure to watch the way his face shifted: anger first, then worry, and finally a snapped-on grin of bravado. All in the course of a second or two. Interesting; he hadn’t known that Fess was here.

Mullen ran a hand down his jacket, smoothing the material. ‘No,’ he said, ‘it don’t mean anything.’

Maybe that worked on the American police, but it wouldn’t fool any copper in Leeds. He knew exactly who Fess was, and he wasn’t pleased to hear the name. No surprise, since he was from a rival gang.

‘A suggestion,’ Harper said as the man drained the rest of his pint in a single swallow. ‘Actually, it’s more like an order. You’re going to take out that gun very carefully and leave it with me.’

‘Why?’ The man’s body stiffened, as if he was preparing for a fight.

‘First of all, you spent a lot of money on that suit and it’s ruining the cut. It’s also illegal under the 1903 Pistols Act. Do you have a licence for the weapon?’

‘I didn’t know I needed one.’

It was a lie, it showed in his eyes. He wanted to be challenged.

‘If the barrel is shorter than nine inches, the law says that you do. Since you’re a visitor here, we’ll let that pass as long as you leave the weapon here.’

For a moment, Mullen didn’t move and Harper could feel the tension grow around him. Then he reached into his pocket, brought out the gun with the barrel between his fingers and placed it on the table.

‘Satisfied?’

‘For now. Thank you.’

The outside door opened and Mary entered, waving before she disappeared upstairs.

‘Is that your daughter? Mary, right?

Annabelle turned her head to stare into his eyes. ‘I tell you what, luv, now it’s my turn to make a suggestion.’ Her voice was iron. ‘Only mine’s an order, too. You’re going to forget you ever knew her name, or that you saw her. And if you show your face in here again, I’ll bounce you out on to Roundhay Road by the seat of your fancy trousers before you can say Jack Robinson.’ She stalked away.

Mullen glared but said nothing. Harper watched as the man stifled his anger. No one would dare talk to him like that in America; he’d tear them apart for the sport of it. But New York was half a world away. He was in Leeds now. The rules were different and he was powerless.

‘I think your wife has taken against me.’

‘Very perceptive, Mr Mullen. There are plenty of other places to drink in town. You’d do better in one of those. I’m sure you can find your way back to where you’re staying. The Metropole, isn’t it?’ He stood. ‘I’ll wish you goodnight.’

The constable following Mullen was standing outside the Victoria, watching his quarry stride furiously away. Harper stood next to him. ‘Make sure you don’t let him out of your sight.’

Brass Lives is published in hardback in the UK on June 24 (7 September in the US). You can pre-order it here (cheapest price and free postage). Prefer ebooks? Here’s the Kindle link (available worldwide August 1)

If you’re on NetGalley and authorised for Severn house releases, you can find it here.

May 19, 2021

The Real Brass Lives

In Brass Lives, set in 1913 Tom Harper – promoted now to Deputy Chief Constable – finds himself face with Davey Mullen. He’d left Leeds when he was a boy to join his mother in New York. Over there he’d become a gangster, a killer. Ambushed by another gang in Manhattan, he was shot 11 times and left for dead.

They should have finished the job. Now it’s his would-be assassins who are in the morgue, while Mullen is back where he began, in Leeds. To visit his father, he claims. But death seems to have taken passage with him, and Harper needs to discover the truth and stop all the killing that threatens to take over Leeds.

Davey Mullen is based on Owen Madden. He was born on Somerset Street to parents of Irish descent. He did follow his mother to New York when he was 10, and he did jon a gang, the Gophers. He developed a reputation for violence and murder.

He really was shot 11 times outside a dancehall, and he survived.

Did he come back to Leeds under another name? Maybe he did…

It’s just a few weeks until Brass Lives is published. You can pre-order from all the usual places…but buying it from a real bookshop would be a lovely gesture. After being closed for so long, they need the business.

Lastly, if you’re new to the series – this is the ninth book – you can make an easy start, as the ebook of the first novel, Gods of Gols, is just 82p (99c) on all platforms. Here’s the Kindle link.

April 13, 2021

Ghosts

This is what happens when you raise the ghosts. When you let the past out of its box.

A few weeks ago I was looking through some old photos and picked up one of my first wife. It had been taken on our first wedding anniversary, on the trip to the US her parents gave us as a belated birthday present. She had glasses that turned dark in the sunshine, so it was impossible to see her eyes in the bright Ohio May light. But the dark hair framed her face and she was beaming at the camera. Young, happy, carefree.

That was a long time ago. Eight years and we divorced. I moved to the West Coast, then back to England. She stayed where she was. I don’t even remember how it happened, but we became friends online. Exchanging messages. And then, last year, from out of the blue I received a message from the daughter of her second marriage. The first time she’d contacted me. My ex was in hospital, she wrote, and not expected to last the night.

It was a brain bleed. She was gone. It rocked me. We were the same age – hers a June birthday, mine July. Not old, not by today’s standards.

Then I glanced at the photo and woke the ghost.

It appeared first when I opened my e-mail a couple of mornings later. No subject header, an address I didn’t know. Probably spam, I thought. But I was curious and opened it anyway.

Do you remember when we went to that village where the Brontës lived? It was winter, it must have been. The main street was very steep. I have a memory that we went up on to that moorland and it began to snow. In my mind, that snow was so heavy we almost couldn’t see? Did that happen or did I imagine it? I’m trying to recall, but it’s lost.

It had happened just as she said. A white-out for a couple of minutes that made us terrified we’d end up lost. It passed, we came down, and laughed about it later.

But who else apart from her knew that detail? It scared me. If this was some kind of joke, it was twisted. It couldn’t be her. That was impossible. She’d been dead for nine months.

I read the words over and over. At first I refused to believe it all. Then the horror arrived. I wanted to trace the email, but I didn’t know how. I’m no techie.

After a day of opening the email endless times until I could have recited each word with my eyes closed, I decided to reply. It was stupid, but there had been a real sense of longing. Of someone lost.

Yes, it all happened. All that snow coming down. I was up there in the summer a couple of years ago. Sun, blue skies, grass and flowers. It looked absolutely different.

WHO ARE YOU?

The reply was there the next morning: I don’t understand. What do you mean? It’s me. I’m trying to remember. The farther back I go, the hazier it becomes. It’s like trying to see through gauze. I was hoping you could help me. It’s hard sometimes. I can’t keep my mind clear. That house we bought here. Was it that bad? When I think about it, it seems like a wreck. Did we really have three dogs?

Here? Did she really think she was still in Ohio? That…no…it couldn’t be. But everything was so earnest. This wasn’t someone having a joke or taunting me. It was real.

Yes, we had three dogs – Rag, Muffin and Lindy. Yes, the house was pretty bad. But cheap. You do know you’re read, don’t you?

A reply within an hour. Dead? I can’t be dead. I’m right here. I know I’m right here. I have to be…

I’m sorry, I told her, but you’re dead. Your daughter messaged me to tell me. It happened suddenly. You remember your husband and daughter, don’t you?

A whole day passed before her reply.

I see them all the time. I’m there with them. It’s the past that seems dim, that’s all Everything recent is clear. I can’t be dead, they’re with me. When did I die?

It was last August, I wrote. By now I was convinced it was real, that it was her. If not, I’d somehow gone mad. But the rest of my life carried on normally. Everything expect the emails. I hadn’t told anyone about them. Who’d have believed me, anyway?

Did I want to believe it? I did. We lose the past soon enough as it is. This was one way of holding on. But I couldn’t understand why she was visiting me.

What about your husband and your daughter? Anything we shared was a long time ago.

Yes, she replied. I just want to know about the past. It’s like trying to see through a fog.

It carried on for a week, several emails every day. From the header, she looked to be on East Coast time.

It all scared me. I didn’t understand it, although a part of me enjoyed the whole idea. It wasn’t quite romantic, but full of mystery.

It kept me awake at night. Soon it was filling my thoughts. That wasn’t good. And it wasn’t helping here. She was asking questions again that I’d already answered.

Finally I saw down at the computer: I know you feel you need this. Perhaps part of you does. But there are people close to you who love you deeply. They’re grieving for you. Maybe it’s time to leave this and be with them. They need to know you’re there.

Then answer was waiting the next morning. You’re right. Thank you. For everything. For those old memories.

No need to reply. I went to make some tea. By the time I returned, the whole thread of mails had gone from the computer, as if they’d never really existed.

That night I dreamed. The usual mix of images. I was in my current car, but I was in Ohio, parking on a track I’d never driven along, that didn’t exist. But I knew it was close to her parents’ house. I went inside. No need to knock. She was there, and the place was filled with the smell of cooking.

She was there, looking just the way she had in the first photo she ever sent me. Smiling. She came over and placed her hand on my shoulders. A touch so light I had to look to be sure it was there. Her breath smelt of wildflowers.

A peck on the cheek.

‘Thank you,’ she said. The voice I remembered.

Then I was walk back to the car.

No more dreams of her since. No more emails.

Just everyday, ordinary life.

And the ghost in my head.

April 7, 2021

It’s Competition Time!

It’s April, and spring is supposedly here. Not that you can prove it by the weather in Leeds. Below freezing at night, slicing winds during the day making a mockery of the sunshine. Anyway, as we hope for something warmer soon and the chance to return to libraries next week (my books are available to borrow, you know), how about a competition?

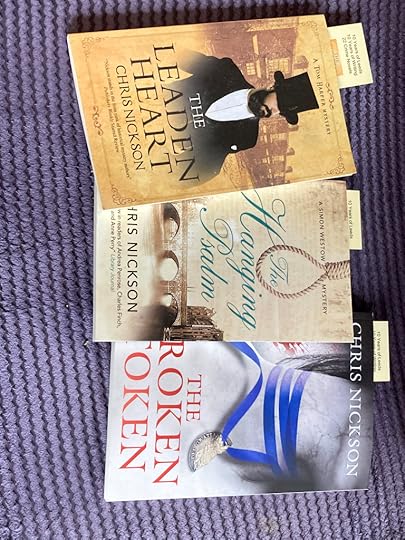

Three novels, one from each of my main characters. There’s The Broken Token, my very first novel, the book that introduced Richard Nottingham. The Hanging Psalm, the opener to the Simon Westow series – the third, To The Dark, came out not too long ago and could use a plug), and finally, The Leaden Heart, the seventh in the Tom Harper series. His newest, Brass Lives, comes out in June, and I certainly won’t mind if you pre-order it now. This place will give you the cheapest price.

Those are your prizes. To win, simply reply with the name of Simon Westow’s young assistant. It’s not hard to find. You have until April 18, when I’ll pick a winner. Sadly, postage rates mean it has to be UK only.

Good luck!

February 24, 2021

The New Tom Harper Novel

There’s a new Tom Harper book coming. The UK hardback publication is June 24th. While I don’t have another date dates, a fair guess would be global ebook publication on August 1, and US hardback on September 1.

Just to whet your appatites, here’s a little bit about it:

Leeds. June, 1913. Tom Harper has risen to become Deputy Chief Constable, and the promotion brings endless meetings, paperwork, and more responsibilities. The latest is overseeing a national suffragist pilgrimage passing through Leeds on its way to London that his wife Annabelle intends to join. Then a letter arrives from police in New York: Davey Mullen, an American gangster born in Leeds, is on his way back to the city, fleeing a bloody gang war.

Despite Harper’s best efforts to keep an eye on him, Mullen’s arrival triggers a series of chilling events in the city. Is he responsible for the sudden surge in crime, violence and murder on Leeds’s streets? Tom has to become a real copper again and hunt down a cold-blooded killer, even as his world starts to crack apart at home.

Do you want to see the cover?

Sure you do, it’s absolutelt splendid.

Isn’t that great? The character of Davey Mullen is based on Owen Madden, a Leeds lad who did become a New York gangland figure. He owned the Cotton Club, and went on to die peacefully at a ripe age. A fascinating made – read about him here

Better start putting your pennies aside.

February 16, 2021

A Pair Of Coppers In The Family

There’s something both delicious and disconcerting about finding your family imitating your books. My maternal great-grandfather had been the landlord of the Victoria public house at the bottom of Roundhay Road – the place Annabelle Harper owned. His tenancy was later, in the 1920s. But that was deliberate on my part, I wanted the connection.

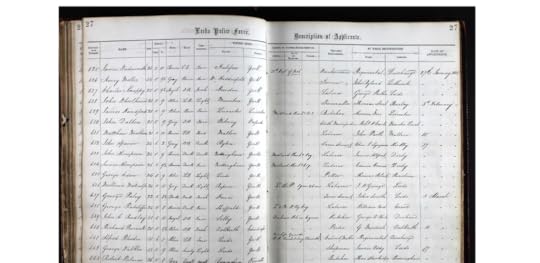

However, given that the Tom Harper books start off with Leeds police in 1890, it came as a surprise to discover I had two Victorian coppers in the family.

Matthew Lamplugh (the name was his great-grandmother’s surname) Nickson joined the force in 1865, when he was 21. He remained a constable, but rose in stature, even with a few disciplinary problems. He was 5 feet 10 inches (about 1.8 metres), with brown hair and light brown eyes, and a “florid” complexion, sworn in as PC 631. A year after joining, he moved to the brand-new fire brigade (one of 16 who made up the initial force under the police); or, rather, he was one of those policemen detailed to attend fires. By 1868, the police fire brigade was a group apart, working out of Centenary Street, close to the Town Hall, In November 1869, the record ends abruptly: “Died”. Sadly, I’ve been unable to discover how it happened.

He had a few disciplinary problems – fined in 1868 for being under the influence when off duty, and drunk on duty in 1865 and under the influence in 1867.

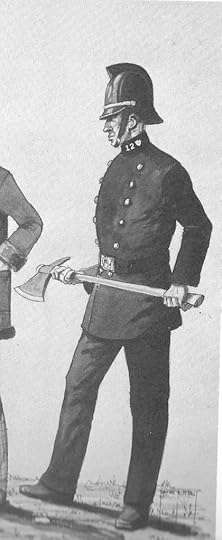

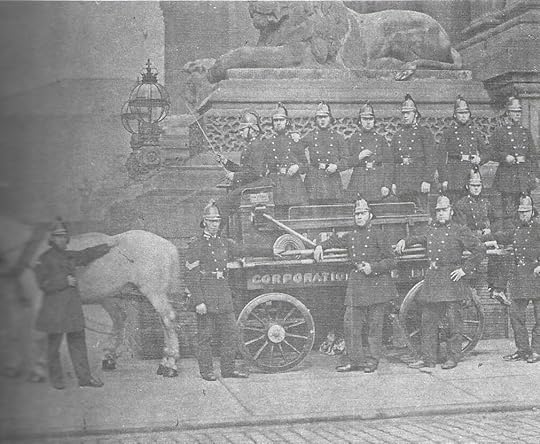

The uniform was changing around the time. It’s quite possible that when he started on the beat, Matthew dressed like this (not a million miles from a uniform of a bosun in the navy):

However, it soon became this:

One he became a member of Leeds Police Fire Brigade, he’d have dressed like this.

This photograph, taken in 1870, show the Leeds Police Fire Brigade with their engine. It had been bought in 1867 at a cost of £42. Anyone who knows Leeds can spot where it was taken, next to the Town Hall steps, with one of the lions in the background. It’s a little poignant to realise that these men, now long gone themselves, went into danger alongside Matthew. They knew him, laughed and joked with him. There’s no record that he ever married.

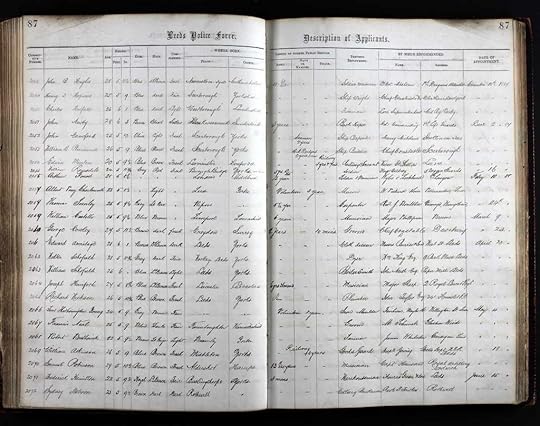

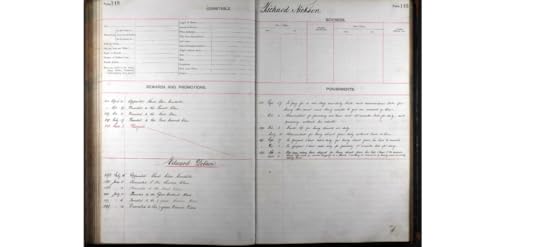

Richard Nickson became a policeman in 1888. He was 26 by then, a fully-qualified plumber who’d severed an apprenticeship. His father had died when he was young and his mother, Mary Caroline Nickson, carried on the successful painting and decorating business for several years. However, in 1877, when Richard was 16, still an apprentice, she married again, to George Heathwaite, who lived across the river in Hunslet. He was a master dyer with his own business, employing eight men. As was the way then, Mary Caroline either sold or gave up her business. The 1881 and 1891 censuses both show Richard living with his mother and stepfather in Hunslet.

He was 5 feet 10 and ¾ inches, blue eyes, brown hair, and a “fresh” complexion (interesting to see the number of former soldiers, especially soldier musicians, who joined up at this time, although there was no police band until 1924) and a qualified plumber.

His uniform would have been an early version of the one familiar to so many.

Although Richard was promoted to First Class Constable within a year, he wasn’t without his disciplinary problems – losing equipment, being late, being absent from duty, drunk on duty.

In 1891 he was promoted to the Good Conduct Class, ironic as he’d been punished for being late and also for vanishing from his beat for 30 minutes, a grave offence.

But what was likely the final straws fell in 1892. In February he was stopped a day’s leave for being absent from his beat for an hour and 20 minutes. The following month he was fined 3” for “abusive language to a female and making an admission of acting immorally”.

His police career ended with him resigning (no date given) and he seems to vanish from all records after that, although someone with a similar name did die later in October 1895 in Sculcoates, part of Hull. Very curiously, a Richard Nickson, the same age and the same father’s name, had married a woman name Ada Humble in Hull in 1883. Yet in the 1891 census, she’s not shown as living with him in Hunslet. Is it the same Richard? After resigning from the force, maybe as an alternative to being fired, did he go back to her in Hull?

We’ll never know. But it’s all fascinating.

Mind you, if I discover I had a relative from the earlier part of the 19th century who was a thief taker, I’ll be very worried.

February 1, 2021

Flay Crow Mill

If you’ve read To The Dark (and if you haven’t what are you waiting for? It’s out everywhere in ebook now, and in the UK in hardback – the American hardback publication is on March 2), then you’ll know that the trigger for everything is a body emerging as the snow melts around Flay Crow Mill.

Flat Crow Mill. It really existed.

It was the name that drew me first. After all, who could resist something as intriguing as that? It was a fulling mill, pounding woollen cloth on the equally wonderfully-named Cynder Island, on the River Aire. It was by the King’s Mill, which for centuries ground Leeds’ corn by law. Both harness the power of the river to do the work. No trace of either remains above ground now, but it’s more or less where the park and car park around Sovereign Street stands.

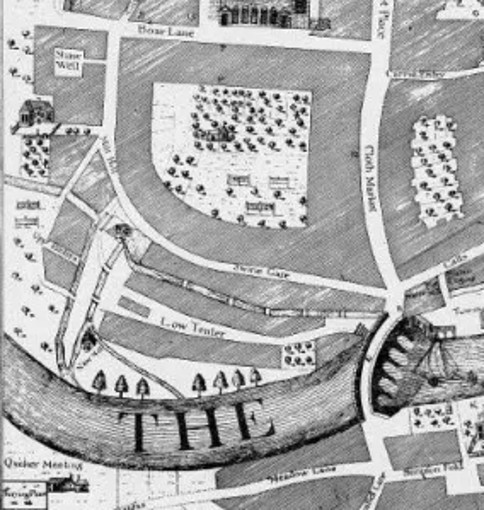

Where did the name originate? There’s no record of that, sadly. But historian Ralph Thoreseby stated that as far back as 1638, merchant and philanthropist John Harrison donated the “undivided moiety” of rent from Flay Crow Mill for the upkeep of his almshouses behind St. John’s Church. At that point, the mill was described as being in the Tenters – where cloth would be staked out on tenterhooks so the fabric could stretch and dry after fulling.

In those days, of course, the area wasn’t build up, and the entire ground surround the mills was tenter fields, as seen here on this 1726 map of Leeds, where the area’s called Low Tenter.

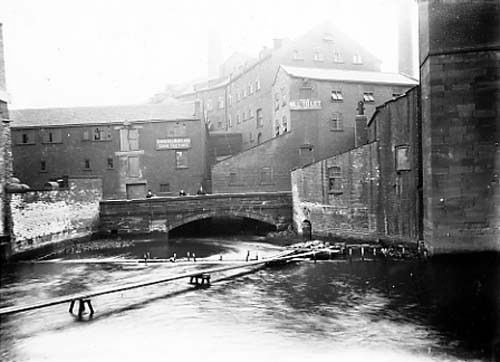

In later years, the mill’s address would be Tenter Lane. This 1890 photo shows Fly Crow Mill on the right and Concordia Mills on the left. Note the bridge linking them. The street – Tenter Lane – continues behind Flay Crow Mill.

When did it fall out of use? Very likely, as Leeds shifted its emphasis from producing cloth to making garments, fulling mills largely became irrelevant here. Even before that, it was likely outdated and uneconomic. In To The Dark, I portray it as a ruin, although that’s doubtful in 1823. It would still have been working them; I took some artistic licence.

In 1904 the building remained, although everything around it was rubble, as this picture shows.

By 2014, as it was about to be turned into a park and car park, CFA Archaeology excavated the site, and a monitor from the West Yorkshire Historical Environmental Record documented it with a few images. It was solid, it was built to last. But time and technology passed it by.

There is, by the way, no recorded of a body being found by Flay Cross Mill. Except in To The Dark, of course.

Images from Leodis and West Yorkshire Historical Environmental Record