Chris Nickson's Blog, page 10

April 3, 2022

Popping Up All Over

The details are on my events page, but I’m heading into a busy season of showing my face in public after two years of being behind closed doors.

April 15, Good Friday, I’ll be at Waterstones in Chesterfield, signing copies of my four Chersterfield books, all set there in the 1360s. Performers from the murder-mystery musical of The Crooked Spire will be there in costime, performing some songs from the show. Just show up between 10.30 and 12.

On April 20 I’ll be at Chapel Allerton library. It’s the place I went to as a kid, so it has great resonance for me, especially as I had to rearrange last month’s date. It’s free, but you need to book your ticket here.

Friday, April 29 will be me in auspicious company at Waterstones in Harrogtate, part of a panel with Julia Chapman (the Dales Detective) and Bella Ellis (the Bronte Sisters mysteries).

March 16, 2022

On Covid And the 1400 And 1500s Nickson

It seems to be a very common story lately. After two years of manging to avoid Covid, it caught up with me. My partner tested positive on a Saturday, and a day later it was my turn. It was thankfully mild, a runny nose here and there, occasional coughs and sneezes. In the early days of the pandemic I’d felt that catching it was a death sentence. And it was for so, so many. Now, thanks mostly to the remarkable vaccines, it ended us a little more than an annoyance to us. I know many are still dying every day, and I’m not trying to make light of it, at all. We were lucky, and there but for the grace of God…

It’s meant rescheduling events, but that’s minor. The first is now next week in Wetherby, with others to follow.

We’re back, fighting fit, and I’m making up for lost time on the allotment. Curiously, having had it and escaped so lightly, I feel liberated. I don’t have to be scared now (although I can get it again, of course; I know several who have). On Monday I took the bus for the first time in two years, for instance. My own fears, yes, and I had the luxury of not needing to take the bus, but even so…

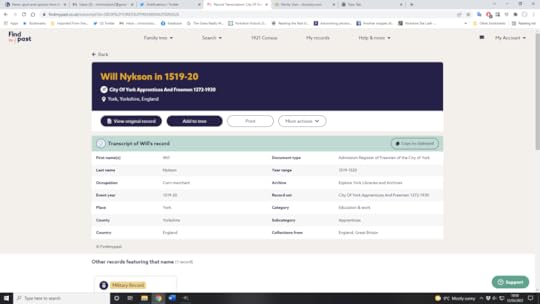

With all that’s happen in Ukraine, everything else seems frivolous. But we all need to escape, and I’ve managed to delve further back on my family tree, to the mid-1400s, which pulls it two generation further back into history. One of them, William Nykson, was a freeman of York, a corn merchant.

A freeman of York

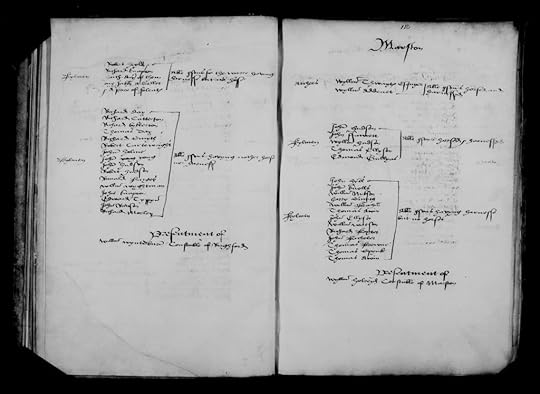

A freeman of York He also appears on the muster roll (third name down in he lonest block on the right-hand page)

He also appears on the muster roll (third name down in he lonest block on the right-hand page)I’ve also discovered a couple of Nicksons from Wilberfoss, about eight miles from York, in the mid-1400s, and another Nykson who became a freeman of York in 1419-20. He was a mason. However, there’s nothing to tie them directly to the line.

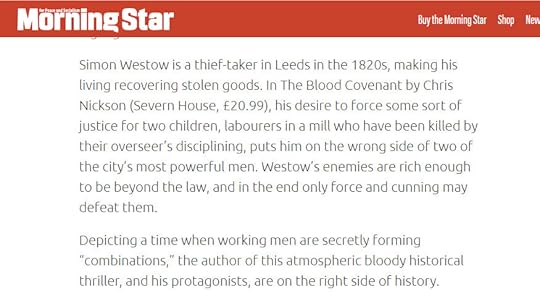

It did all make me realise something, though. The Nicksons (in their spelling variants) pop up in York, then one of them goes to Westow sometime in the 1500s, which isn’t far away, and the family stays there until the 1820s, when Isaac Nickson moves his family to Leeds. Again, it’s not a huge distance. We’ve never exactly been a family given to shofting around the globe. My 30 years in the US looked to be the exception. And even then I came back. Maybe the return was in my genes…all I know is that Leeds feels right,m and maybe I’m doing something right by my hometown. A new review of The Blood Covenant says it “reveals the way power and wealth can corrupt and pervert decency and justice, a message that is as relevant today as it was two hundred years ago.”

February 16, 2022

A Brand New Tom Harper Novel

Later this year, there’s a new Tom Harper book coming. It’s called A Dark Steel Death and it’s set during the First World War…

Leeds. December, 1916. Deputy Chief Constable Tom Harper is called out in the middle of the night when a huge explosion rips through a munitions factory supplying war materials, leaving death and destruction in its wake. A month later, matches and paper to start a fire are found in an army clothing depot. It’s a chilling discovery: there’s a saboteur running loose on the streets of Leeds.

As so many give their lives in the trenches, Harper and his men are working harder than ever – and their investigation takes a dark twist with two shootings, at the local steelworks and a hospital. With his back against the wall and the war effort at stake, Harper can’t afford to fail. But can he catch the traitor intent on bringing terror to Leeds?

Would you like a very early look at the cover? Scroll down. But first, I’m going to say with pride that the beautiful Leeds Library, the oldest subscription library in Britain, founded in 1768 (read about it here) has listed their most-borrowed titles of the last 30 years, and The Broken Token is in there at number eight, among some huge names. I honestly feel pretty humble.

And now for the cover of A Dark Steel Death. What do you think? Please, let me know.

February 10, 2022

A Tale Of Two Brothers

Not just any pair of brothers; well, not to me. These are my great-great-great uncles

When my great-great-great-great grandfather moved to Leeds from Malton, had brought a family with him: a wife and four children. He was a butcher, and would have had to serve an apprenticeship in the trade. He quickly set up shop on Timble Bridge.

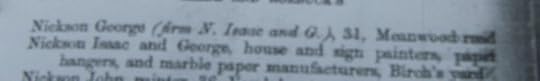

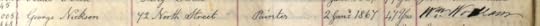

Isaac’s oldest son was also named Isaac, baptised in 1815. Four years later, another son named George, came into the world. Both were born in Malton and arrived in Leeds as boys As they grew, they apparently had little interest in following in their father’s footsteps. Instead, both became painters and decorators (as did another brother, John).

To enter the trade, they would probably have both had to serve an apprenticeship or indenture. Isaac Sr. would have needed to pay a fee for this, although it would have been less than for other trades.

Isaac married Elizabeth Watkinson, who was a year older than himself and the daughter of a wool stapler, at the Parish Church in Leeds in October 1834. He would have been 19. Their son, William Robert Nickson, was born in 1837. On the 1851 census, Isaac was listed as a painter and living at 50, Birch’s Yard.

George was also 19 when he married Mary Caroline Hewson, in 1839. By 1851 they had four children, the oldest being a boy of nine, and lived at 31, Meanwood Road. George described himself as a painter and paper hanger.

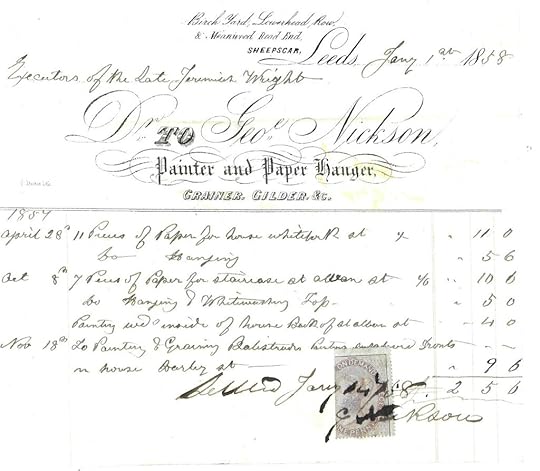

Isaac and George went into business together in 1847. Before that they’d probably been journeymen, employed by others. Their business premises in the Lowerhead Row – in Birch’s Yard where Isaac was listed as living.

Birch’s Yard goes off to the left, between buildings

Birch’s Yard goes off to the left, between buildingsHome decoration and painting, and especially wallpaper, had become a thriving business as the 19th century progressed. Where it had once been an indulgence of the upper classes, it had moved beyond that. The middle classes wanted to make their mark on the houses they owned. Together, the brothers could take advantage of this (although their boast of ‘workmen sent all over the country’ was probably just as way to make themselves sound like a big firm). They were also listed as wallpaper marblers. This was a fad that had come back into vogue; knowing how to do it themselves would bring in more business.

George and Isaac seemed to do well enough for the best part of a decade. Then, in October 1856, Isaac announced in a newspaper ad that they’d dissolved the partnership “by mutual consent” and that he had new premises on Wade Street (although he’d also be in the place on Lowerhead Row until 1859). By now he was a sign-writer, furniture painter, whitewasher, and handled ornamental colouring, as well as “painting and paper hanging in all its branches.”

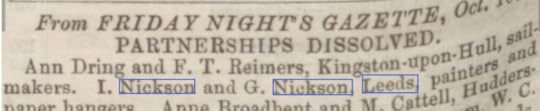

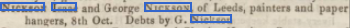

It seems straightforward enough. However, in a single, short line, a publication called Perry’s Bankrupt Gazette offered the real reason: The partnership had been dissolved on October 8 because of debts by George Nickson.

It wasn’t until 1859 that Isaac finally moved from the Birch Yard address to trade solely in Wade Street. He did also briefly have a place at 21, Roundhay Road in Sheepscar, but that doesn’t seem to have lasted long.

George kept on the Birch Yard premises as well as using his home address in Meanwood. Both appear on an invoice from 1858.

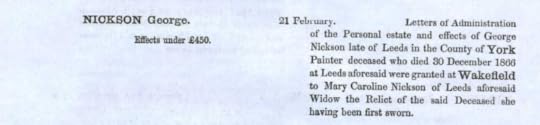

If he’d had debts, they hadn’t stopped him continuing to trade, which he did until his death on December 30, 1866, at the age of 46.

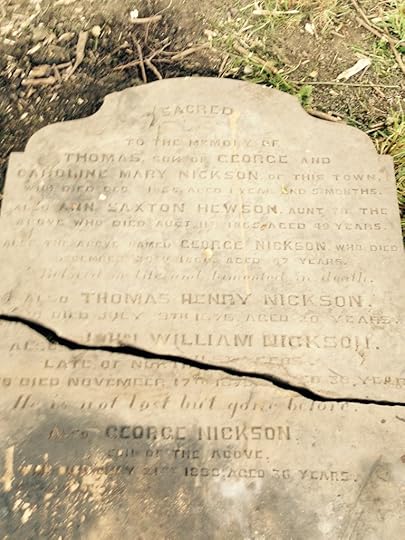

He was buried at Beckett Street Cemetery, his address showing as 42 North Street – barely a stone’s throw from where he used to live on Meanwood Road. His gravestone shows several of his children buried in the same plot.

He must have done moderately well for himself, although he only left under £450 to his wife.

But she proved to be a very adept businesswoman.

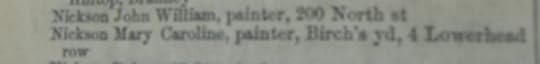

She continued the business after he died, and in the 1871 census proudly declared that as a painter and decorator she employed seven men and a boy.

However, in 1877, she married a man from Hunslet and moved there, dying in 1897 at the age of 76.

In 1870, their daughter Jane married a man named Ward, the event warranting a notice in the papers.

The death of his song George in Hunslet in 1888 also received a notice.

Isaac, however, had moved up in the world. Painting and decorating were lucrative for him. He’d become a voter, which means that his property on Wade Street, which was both home and workplace, as was often the case, had a good freehold value, and he apparently owned another property of Back Blundell Place

In 1866, he was one of a number of speakers at an event in the Working Men’s Hall, a sure sign that he’d become somebody. He was also listed as one of those campaigning for Edward Baines in the election.

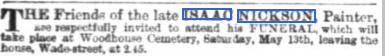

He didn’t have too many years to enjoy his success. In May, 1871, though, Isaac died, aged 55. He was buried at Woodhouse Cemetery.

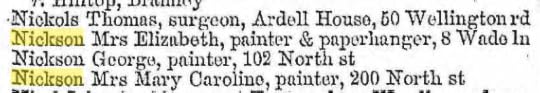

Interestingly, it wasn’t just George’s wife who continued the family business. Elizabeth, Isaac’s widow, was listed in the 1872 directory as a painter and paper hanger, still at the Wade Street address.

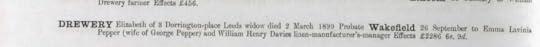

In 1876, however, she remarried, aged 63. On June 27, no longer calling herself a businesswoman, she married Thomas Drewery, a man 10 years her senior. He lived on Hanover Street, just off Hanover Square, a fashionable Leeds address, and styled himself as a gentleman.

Elizabeth die in 1899 and left £2200, a very respectable sum. However, the two people who shared the money hadn’t shown up before in her family. Who they were remains a mystery. Her second husband had died in 1892 and left over £2000 to his son.

Isaac and Elizabeth’s son, William Robert, also made a good living as a painter. He also held enough property to become a voter, with a house at 11 Wade Street, very close to his father. He died in 1890, by which time he and his family were living on Ramsden Terrace, and was buried at Beckett Street Cemetery.

Two brothers, two families that went very different ways. I have to admit, I’d love to know what debts of George’s broke up the partnership, or was there more simmering underneath? Far too late to know now, of course. But what we can learn does offer its own tale.

January 25, 2022

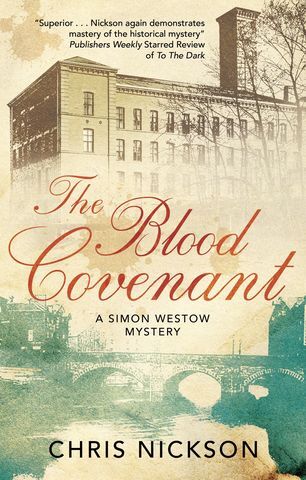

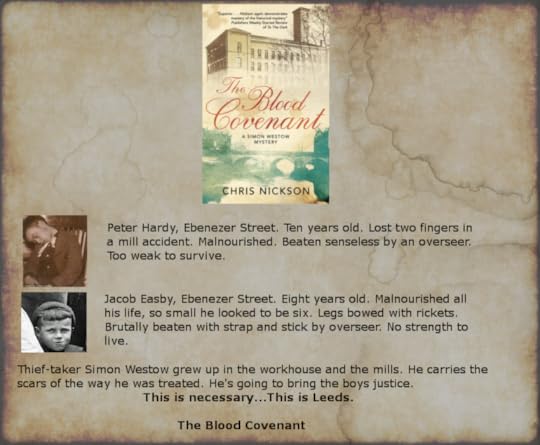

What Reviewers Are Thinking Of The Blood Covenant

The hardback edition of The Blood Covenant appeared in the UK almost a month weeks ago, and the reviews are arriving.

I’ve been lucky enough to have some outstanding reviews of my books in the past, and I’m grateful for every word written about what I do. But those seem to pale in comparison to the opinions on this one, to the point that it’s hard to believe they’re writing about my work (not about me; that’s entirely different).

The Fully Booked blog has been a supporter of my novels, but this…well, read for yourself: “There is, of course, a noble tradition of writers who exposed social injustice nearer to their own times – Charles Dickens, Charles Kingsley, Robert Tressell and John Steinbeck, to name but a few, but we shouldn’t dismiss Nickson’s anger because of the distance between his books and the events he describes. As he walks the streets of modern Leeds, he clearly feels every pang of hunger, every indignity, every broken bone and every hopeless dawn experienced by the people whose blood and sweat made the city what it is today. That he can express this while also writing a bloody good crime novel is the reason why he is, in my opinion, one of our finest contemporary writers.”

How can I live up to that? I don’t know; all I can do is try. Read the whole review here.

On: Yorkshire isn’t quite as effusive, but even so… “Nickson has a rare talent for historical reproduction, and the filth and horror of the time he writes about is conveyed loud and clear… Nickson is a fine writer”

Yorkshire Bylines has good, practical praise: “The Blood Covenant would be a good book to take on a train or plane ride; the plot is easy to follow, and the story is fast-paced. I read it from cover to cover in one three-hour sitting. Those who like fast-moving action adventure with a hint of mystery and some graphic descriptions of violence will enjoy this book.”

Read the entire review.

The ebook will appear everywhere at the beginning of February, and publication of the hardback in the rest of the world is at the beginning of March. But two of the US trade magazines, aimed at librarians and bookshops, have ready put out their reviews.

Kirkus Reviews says it’s a “gritty tale of perseverance, cruelty, rage, and redemption not for the faint of heart.”

That’s quite true, and here is the rest of what they said.

Publishers Weekly has given it a starred review (it’s here). That in itself can make a writer’s heart jump with joy. But on top of that, what they have to say!

“Nickson’s stellar fourth mystery featuring thief-taker Simon Westlow [sic]… Nickson does a superb job using the grim living and working conditions for the city’s poor as a backdrop for a memorable and affecting plot. James Ellroy fans will be enthralled.”

Honestly, I’m still buzzing from that (I’m trying to figure out the Ellroy comparison), and everything that all the reviewers have written. I’m grateful to them all for wanting to read and write about it. People on Goodreads have been incredibly generous with their praise, too (“Nickson is a master when it comes to historical crime fiction, and together with his phenomenal research, he continually provides a cracking read!”… “Chris Nickson has outdone himself in The Blood Covenant. There’s truly a different tone in this one.”)

And then there’s this from the Morning Star. On the right side of history…

I have no idea how I can ever top these reviews. I shall try.

Meanwhile, I hope they’ll make you read the book. Buy it, borrow it from the library – if they don’t have it, ask them to get a copy; that will let others read it, too.

Thank you all. Truly.

January 17, 2022

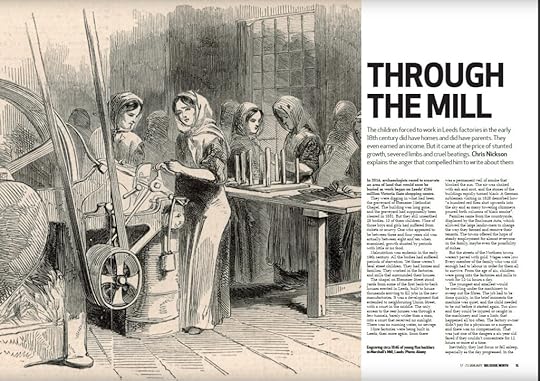

The Real Lives Behind The Blood Covenant

Last month my new novel, The Blood Covenant, was published in the UK. The catalyst for Simon Westow in the book is the brutal deaths of two factory boys at the bullying hands of overeers, which brings back memories of his own childhood in the workhouse and the mills.

This was real, and the dig for the site of what became Victoria Gate shopping centre in Leeds brought up the bodies of local children, factory children, who’d lived short, horrific lives. They weren’t the exception, as testimony to the Sadler Committe in 1832 showed. I’m profoundlky grateful that Big Issue North asked me to write about the reality. It’s in the issue published today (January 17) – and it’s a magazine that’s always worth your money.

The testimony is harrowing, but it’s a window on their lives.

First page

First page Second page

Second page

December 15, 2021

Another Extract from The Blood Coventant

Another short extract from The Blood Covenant that I hope will tempt you into buying a copy (or asking your library to buy one – maybe even both!) Most bookshops seem to have copies now, although it’s not out until the 30th officially. If you ask them nicely, they might well be able to get it to you for Christmas…for online ordering, this place has the cheapest price, with free UK postage, and they can get it straight out.

Jane’s turn this time.

Jane turned off Boar Lane on to Albion Street and knew someone was there. She had the sense of him before she could see anything. Tightening her grip on the hilt of the blade, she peered into the darkness.

Suddenly he was in front of her, no more than three yards away. As if he’d appeared from nowhere. Looming like a giant. Tall, broad as a house. If she allowed him to come close enough, he’d be able to crush the life from her.

The bayonet that usually hung from his belt was in his right hand.

Perkins. Arden’s bodyguard, grinning at the sight of her.

‘You and your boss, you’ve been poking in places where you don’t belong. Causing trouble for Mr Arden’s friend.’

Jane didn’t reply. She was watching him, her mind racing over the advice Dodson the crippled soldier had given her. A dirty fighter, brutal, with years of experience. If he won, he’d leave her for dead without a qualm.

A weak right knee. That was what Dodson had said. Not much, but it was something.

Perkins moved towards her. Only a single pace, but it was enough. He was going to use his size and weight against her. He had to be in his fifties now, grey hair cropped close against his skull; old for work like this. But he still had power. What he’d lost in speed he made up for in trickery.

Jane could see it in his eyes; he believed she was an easy target. A girl who’d have no fight in her. He took another pace forward. She tried to feint to her right, but he was already moving to stop it. Old, but not so slow. And not slipping on the packed, frozen snow.

He wanted to keep her moving backwards until she was pinned against the wall. Once that happened, he could take his time. Finish her as quickly or slowly as he wanted.

She was watching. His eyes, his hands. His feet. They’d give the clues. Even knowing she might die here, she felt calm. She touched the gold ring. A single step back, to see what he’d do. His eyes glinted, as if he already sensed victory.

Good, she thought, let him. Maybe he’d let down his guard a little.

Perkins swung his arm, the bayonet slicing through the air. But that wasn’t the danger; it was a diversion, he’d put no power into it. He was shifting his balance, preparing to kick her. As soon as he raised his foot, she darted forward with a kick of her own.

She put all her weight behind it. She felt the hobnails on the sole of her boot crash into his right knee. The feel of something giving in his leg. He staggered, arms out to try and keep his balance. Mouth shut tight to stifle the cry. Eyes filled with fury and surprise.

She could run. He wouldn’t be able to follow. But if she did that, Jane knew he’d recover and come for her another time. When that happened, she wouldn’t have the smallest chance of staying alive.

The thoughts flew through her head in a moment. No hesitation. She kicked his knee again. This time it gave. He fell on to the pavement, scrambling backwards so he could try to defend himself.

November 30, 2021

Coming VERY Soon…

It’s December, which means it’s less than four weeks to Christmas, and a little over that until the UK publication of The Blood Covenant.

Today, or very, very shortly, it will be available to read on NetGalley. If you’re a blogger or reviewer and registered with Severn House (my publisher), it going to be waiting for you.

Or you could pre-order the book and there’s a good chance you’ll have it by Christmas. Here has the best price, with free shipping.

Plenty can’t afford it. Ask your library to buy a copy. That way plenty of people will be able to read it.

It’s not a cosy read. But factory bosses working children 12-14 hours a day, and overseers brutally punishing them isn’t comfortable reading. This isn’t the Regency of Jane Austen or Georgette Heyer. This is Regency Noir

Bringing them some justice…it’s bloody and hard. But worth the pain.

What would you do if they were your kids?

This is a book that means a lot to me. It’s stirred my anger in a way that little else has. If you read it, please leave a review.

Thank you, and I hope it moves you.

November 26, 2021

Competition

Not selling anything on Black Friday, but giving away copies of my last two books. Simply tell me how many now in the Tom Harper series (just hit comment). I’ll select the winner on December 3 – plenty of time for Xmas. But UK only, sorry. Please include your email address.

November 24, 2021

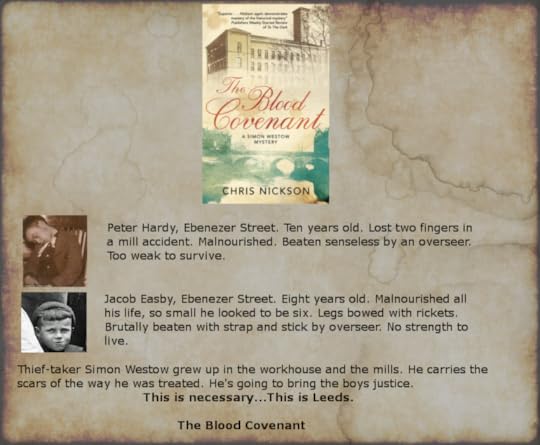

A Trailer…for The Blood Covenant

It’s coming…six weeks and it will be here. How about a littel trailer to tell you the heart of the book. One minute and ten seconds of your time.

From early December it will be abailable on NetGalley. If you’re a reviewer of blogger and want a copy, please let me know with your email address.

Meanwhile…remember…

This is Regency Noir.

This is necessary.

This is Leeds.