Paul Polak's Blog, page 4

October 7, 2013

How to solve India’s poverty crisis

By Paul Polak and Mal Warwick

By Paul Polak and Mal Warwick

Economic debate swirls around the question of how to end poverty, and no wonder: today there are still 2.7 billion people living on $2 a day or less. How should a nation that contains nearly one in three of the world’s poorest people address this very real problem? At one extreme among Indian observers, Nobel Prize winner and Harvard professor Amartya Sen urges greater government investment in programs to aid the poor. At the other, Jagdish Bhagwati, Columbia professor and leading trade economist, insists on the need to fuel the growth of industry and the middle class. From our experience in India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Zimbabwe, and many other countries, we believe that both are wrong.

The conventional definition of economic growth—increase in average per capita GDP—is totally irrelevant to people living in extreme poverty. If you’re one of 400 million people in India earning $400 a year or less and the board chairman of Reliance Industries earns $18 million, the fact that the average per capita income between the two of you is $9,000,200 will give you scant comfort.

Economists have it all wrong

Throughout the poor countries of the Global South, the economic growth reflected in per capita GDP is overwhelmingly commercial, industrial, and urban, with little direct impact on rural areas, where most extremely poor people live. India has experienced almost eight percent annual GDP growth over the past decade, but according to the World Bank, two-thirds of the population still lives on less than $2 a day, and there are still 300 million people who go hungry—despite far-reaching but ineffective government programs to provide schooling, feed children, and directly subsidize some of the poor. We do not see any hope that increased investment either in conventional economic growth or in government assistance programs is likely to do any better.

The only effective large-scale answer to extreme poverty is to stimulate rapid scalable growth centered specifically in the villages where most poor people live, not urban-centered growth that generates only a trivial trickle-down impact. If you ask poor people why they’re poor, as we have, they’ll freely tell you they simply don’t have enough money.

Three ways to end poverty

However, we see three effective ways to address the challenge of poverty: by (a) helping poor people develop income-generating businesses of their own; (b) providing jobs that allow them to increase their incomes through wages or salaries; or (c) selling them products that enable them to earn or save money.

We’re all familiar with the global effort to help poor people build their own businesses through microcredit—an effort that has brought mixed results. (The biggest problem is that most microloans are used for consumption, not to build businesses.) But where are the market-based solutions that deliver jobs in large numbers to the bottom billions or products that help them increase their incomes? Sadly, there are all too few, and none has reached meaningful scale.

Limitless opportunities for business

The opportunities are there for all to see:

At least a billion poor farmers around the world lack access to affordable income-generating tools such as small-plot irrigation, information on how to farm better, and access to markets for the crops they grow.

At least a billion poor farmers lack access to crop insurance, and even greater numbers have no access to health and accident insurance that could lessen their financial challenges.

Nearly one billion people in the world go hungry on any given night, and an equal number lack access to affordable nutritious foods.

More than a billion people live in rudimentary shelters, constituting a ready market for $100 to $300 houses with market and collateral value that could start them on the road to the middle class

At least one billion people have neither latrines nor toilets

More than one billion people have no access to electricity

One billion or more don’t have access to decent, affordable schools

A minimum of one billion people lack affordable and professional health services.

At least one billion use cooking and heating methods that make them sick and pollute the air.

We believe that all these areas, and many more, offer huge opportunities to create profitable global companies capable of transforming business as usual and reducing the incidence of extreme poverty in the process. They’re just waiting for imaginative entrepreneurs or existing businesses ready to tackle the challenges of radical affordability, last-mile delivery, culturally appropriate marketing, and, above all, design for scale.

If just 100 new businesses set out on this path, committing themselves to attract 100 million customers each in the first ten years, generating at least $10 billion in annual sales, and earning generous enough profits to attract mainstream capital, we would see, at long last, meaningful progress in the global fight against poverty. It’s time to stop theorizing and get down to business.

September 7, 2013

Achieving Scale

Scale is the single biggest unmet challenge in development and impact investment today. IDE, the development organization I founded, has helped some 20 million people living on a $1/day move out of poverty, but this is a drop in the bucket compared to the 2.7 billion people still living on less than $2/day. About the only big business to reach poor people at scale is mobile phones, and that happened pretty much by accident. I think it’s entirely feasible to help 100 million poor people at a time move out of poverty with technologies they need to raise their incomes, with the right distribution systems, and with business incentives at all levels. Mal Warwick and I have described some of the basic steps to achieve scale in our new book, The Business Solution to Poverty, to be released September 9th. They are not overly complicated.

It’s important to start with a problem that is scalable and to take advantage of market-based strategies. For example, assuming that 10% market penetration is feasible, why not start by only addressing problems shared by at least a billion potential $2/day customers? There are plenty of such problems. There at least a billion $2/day customers without access to safe drinking water, and another billion without access to decent affordable health services, electricity, education, sanitation, and many more. Selecting a scalable problem to begin with and building a scaling strategy into the business plan from the beginning are two key elements to a practical scaling strategy.

What about the organizational structure that is needed to achieve scale? If you need to sharpen ten pencils, it’s pretty obvious how

Pencil Sharpener

you would go about it. But how would you efficiently sharpen a thousand pencils? A million pencils? A hundred million? To sharpen a hundred million pencils a day, you would have to identify a number of processes that are practical to reach scale. You would go through the same process to figure that out for pencils as you would with a lot of different processes to reach scale in serving poor customers. To reach one hundred million customers with safe drinking water, we had to learn and operationalize every step it takes to deliver water to a block of 50 new villages in Orissa every month. With this defined, we will roll out services in multiples of 50 village blocks every month.

Flowers used in Hindu temple ceremony

People celebrating Holi festival

I met Madhumita Puri, from New Delhi, India at the Unreasonable Institute meeting of social entrepreneurs in Boulder, where I’m a mentor. India has 108,000 Hindu temples, and flowers like marigolds are brought by the thousands to each temple every day. In fact, each temple throws out about 50-60 kilos of wilted flowers every day. For Mahumita’s company Trash to Cash, disabled people in New Dehli, India collect flowers discarded by 60 of these temples so they can be ground to create a powdered dye for Holi, a Hindu festival celebrating the harvest season and the good that comes from loving God. During Holi, people gather in the streets, celebrate, and throw powdered colors over each other. The festival creates a huge market for dye that can be made by processing these flowers.

Currently Madhumita’s company has 118 employees, 84 of whom are handicapped. They now generate and sell $26,000/year of this colored powder. She believes the year-round market demand for Holi powder is in the tens of millions. She told me there are four million disabled people in Delhi, and 70 million in India. Trash for Cash now provides jobs for just 84 of them, by collecting discarded flowers from 60 temples, but could provide so many more jobs. How could she bring her current business to scale? It takes not being afraid of math and then it takes planning for scale.

There are an estimated 108,000 Hindu temples in India, and 3,000 or so in the Delhi region. Each temple discards 50-100 kilos of flowers per day, which amounts to about 150 tons of discarded flowers/day in the Delhi area alone. If she could convince a quarter of the temples in the Delhi region to provide her with their discarded flowers, she would need to expand from 60 temples to 750 temples. If she went national with 25% of the temples in India, she would need to expand her collection, processing and marketing operation to deal with the flowers from 27,000 temples, with a throughput of more than a thousand tons of discarded flowers per day. This thinking is not too unlike that required plan of how to sharpen a million pencils a day. The design of a last mile collection system, centralized vs. decentralized processing, packaging, branding and marketing, preparing a budget, and raising the funds are all critical in a step by step scaling process.

In the end, an effective scaling strategy boils down to answering a large number of fairly simple questions. But the devil is in the details, the more of which you consider, the greater your chance of success! The ultimate goal of scale is to have a real impact on those you are trying to help. Adjusting your strategy by how many people you are trying to reach!

By Paul Polak

Co-authored by Kathryn Flexner

Paul Polak interviewed at Cornell University about commercialization and scale

August 22, 2013

Paul Polak’s Top 10 Books

Following is a list of the ten books that have been most helpful in increasing my understanding of the world.

Following is a list of the ten books that have been most helpful in increasing my understanding of the world.

1) Small Is Beautiful: Economics as if People Mattered, by E. F. Schumacher (Blond & Briggs, 1973)

2) The White Man’s Burden: Why the West’s Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good, by William Easterly (Penguin Press, 2006)

3) Mao’s Great Famine: The History of China’s Most Devastating Catastrophe, 1958-1962, by Frank Dikotter (Walker & Company, 2011)

4) Prague Winter: A Personal Story of Remembrance and War, 1937-1948, by Madeleine Albright (Harper, 2012)

5) Three Cups of Deceit: How Greg Mortenson, Humanitarian Hero, Lost His Way, by Jon Krakauer (Anchor, 2011)

6) Hell’s Cartel: IG Farben and the Making of Hitler’s War Machine, by Diarmuid Jeffreys (Metropolitan Books, 2008)

7) Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China, by Jung Chang (Simon & Schuster, 1991)

8) Mao: The Unknown Story, by Jung Chang and Jon Halliday (Knopf, 2005)

9) Freedom’s Forge: How American Business Produced Victory in World War II, by Arthur Herman (Random House, 2012)

10) The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Eradicating Poverty Through Profits, by C.K. Prahalad (Wharton School Publishing, 2004)

May 20, 2013

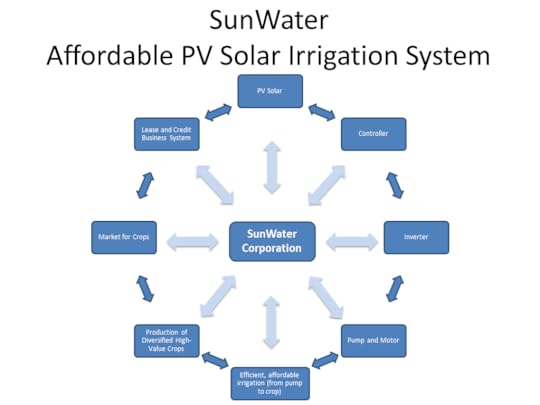

The SunWater Project – Advanced Solar Technology for Poor Farmers

In my last article, you heard about SunWater, a project to build a radically affordable solar water pump for $2-a-day farmers that will transform small plot agriculture, create new water markets, and significantly increase incomes that will raise bottom-of-the-pyramid families out of poverty. Our target customers are small-plot farmers in India and Africa.

These farmers need a reliable, low-cost water pumping system so that they can grow cash crops to increase their incomes. They also need electric power to add value to their crops (grinding, processing, etc.) and for household use. Current pumping systems cost too much or are unreliable.

Solar pumping systems have been available for years, and they show great promise. But they haven’t been adopted at scale for a very simple reason. They cost too much!

The purchase price of solar PV systems is much too high to be competitive with diesel pumps, even though the fuel and repair costs of diesel pumps are astronomical.

If we could cut the cost of solar pumping systems by 80%, we could transform small farmer incomes, create tens of thousands of new jobs, and significantly lower carbon emissions.

How It Can Be Done

So, how can we radically reduce the purchase price of solar PV powered pumping systems along with technologies that efficiently transport irrigation water from the source to the plant? Here’s a deep dive into the different parts of SunWater!

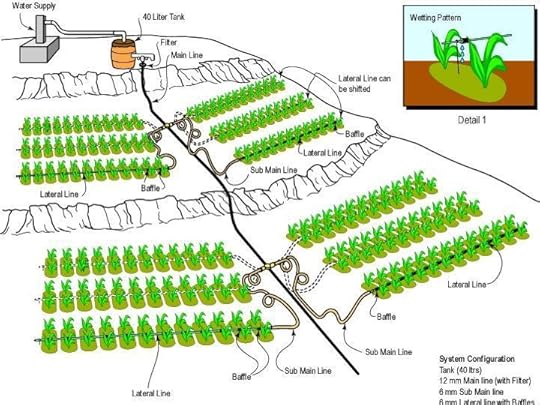

The good news is that affordable small farm systems are already available through the work of IDE. Through the work of IDE, the market price of drip irrigation has been drastically reduced by using comparatively thin walled lay-flat hose to convey irrigation water from sources like tube-wells to rows of plants. The cost of drip irrigation systems were reduced by designing affordable filters to remove dirt from the water, reducing system pressure to reduce the wall thickness of supply and lateral tubing bringing water to each plant, and simplifying the design of the emitters, or drip points, along each lateral. This reduced the cost of drip irrigation systems from about $1,200, or more to less than $600 per acre.

So what about the greater challenge of cutting the cost of a solar PV system and a pump motor combination from $7,000 to $2,500?

Here’s how I think it can be done:

1 Zero Based Design

In my new book with Mal Warwick, The Business Solution to Poverty: Designing Products and Services for 3 Billion New Customers we provide a detailed description of zero based design. Like zero based budgeting, it starts from scratch, making no assumptions about the technology and strategy that can best be used or created to address a specific problem. In this case, we’ve defined the problem as cutting the cost of an installed 2-kilowatt solar PV powered pumping system to $2,500. We have broken this down further to set a price target for the installed solar PV system of 70 cents a watt ($1,400 for a 2-kilowatt system), and the price of controller, pump and motor at less than $1,100, for a total retail price of $2,500. If we can achieve these targets, we believe solar PV powered pumping systems would be economically competitive with diesel-powered pumps, which would create transformative new energy markets in developing countries.

2 A Systems Approach to Design

To pull it off, we’ll need to work on solar pumping, irrigation, and livelihood enhancing high-value crop production and marketing as a total system, with each system component influencing the design of each other component, and of the total system. Figure 1 is a diagram of what this system looks like. Integrated financing also needs to be part of the system solution.

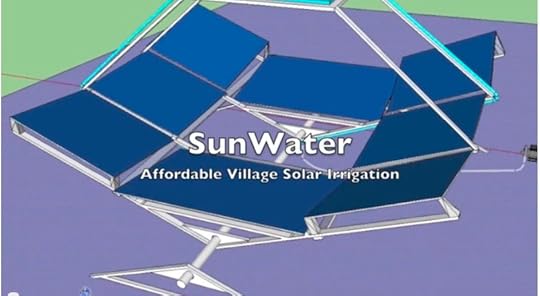

3 Mirrors are Cheaper Than Solar Panels

In spite of the fact that the price of photovoltaic (PV) solar systems have dropped significantly over the past ten years, the capital cost of an installed PV system used to pump irrigation water is still far too expensive to be competitive with diesel powered pump sets. But there are many options for further lowering the capital cost.

For example, a simple glass mirror is much cheaper than a solar panel. If we reflect the sunlight hitting ten glass mirrors that are a little bit bigger than the surface area of a 250 or 300 watt solar panel, we should be able to generate 2,000 watts from it. Since we’re pumping water, we can pump a small amount of water through a simple heat exchanger on the back of the PV panel to keep it from overheating. The mirror system would need to be incorporated into a simple frame that could be rotated to track the sun. This is just one out of the out-of-the-box solution that could lower the cost. A simple initial prototype we built in collaboration with Ball Aerospace engineers worked pretty well. See Figure 2.

4 Improving Water Conveyance and Application Efficiency

Most diesel powered pumps convey water from the pump to the crop in unlined channels, and deliver it to plants by flooding the field, with the end result that 60 to 70 percent of the water pumped out of the ground is lost to seepage before it ever gets to the plants that need it. Using thin-walled lay-flat tubing to carry the water from the pump to the field, and low-cost drip irrigation to deliver water to the plants would double the overall efficiency of traditional water conveyance and application methods. This would either double the water available for irrigation or cut the size of the pumping system in half, either of which have the same functional impact as cutting the cost of the solar powered pumping system in half.

Fifteen years ago, I and my colleagues at IDE started designing and field testing a low-cost drip system for small farms that is about one half the price of conventional drip systems. Such a low-cost drip system costs about $1,400 for 2.5-acres, including the lay flat hose to carry water from the pump to the field, and IDE field tests in a variety of countries have demonstrated that typical farmers can earn net income after expenses of 45 cents/square meter, or $4,500 from a 2.5-acre plot of diversified high-value cash crops like off-season vegetables by putting the low-cost drip system to work.

You can’t pay for a low-cost drip system and a solar PV powered pumping system, and make a profit by using the water these systems produce to grow low value crops like rice, wheat, corn, and pulses. To earn a reasonable livelihood, small farmers need to learn to irrigate in the dry season when vegetable prices are two or three times as high as they are during rainy season when everybody can grow vegetables. Savvy farmers plant four or five high-value crops, because it’s impossible to predict what the market price for any one crop will be. Also diversified cropping both lowers risk and increases probability that at least one of the crops will generate lucrative profit. So, it’s just as important to help farmers optimize income as it is to lower the cost of pumping and improve the efficiency of conveying and applying water from the source to the crop.

6 Creating a Scalable Profitable Business Model

6 Creating a Scalable Profitable Business Model

The best way to reach scale is to release market forces, creating opportunities for every participant in the marketplace to earn a reasonable profit. This includes the manufacturers of both the solar PV powered pumping systems and the irrigation systems, the dealers who sell them, the technicians who install them, and the farmers who buy them to improve their livelihoods.

The first barrier to profitability is the capital cost of $3,900 for the total system. Even though it can earn attractive returns on investment, the upfront cost is too high for most small farmers. For this reason, an important player in the system needs to be a business that offers the solar PV powered pumping and irrigation system on a lease basis or on credit, with the lease/credit business also earning an attractive profit.

SunWater is a project run by my company, Paul Polak Enterprises. We are partnering with a group of volunteer engineers from Ball Aerospace, the company that built the instruments on the Hubble space telescope, to build the proof of concept prototype of the $2,500 solar PV powered pumping system. Jack Keller, a world authority on drip and sprinkle irrigation, and Bob Yoder, an irrigation engineer I worked with at IDE, are working on the design of the total system and its beta testing and pilot commercial rollout in Gujarat, India. There we will be working with an Indian subsidiary of Paul Polak Enterprises, and they will play the local leadership role.

From Gujarat, SunWater India will initiate a full scale rollout of the affordable solar PV powered pumping and irrigation system in India’s Eastern states, where the majority of India’s existing 19 million diesel pumps are located. My dream is that after we create a new market for solar PV powered pressurized irrigation in India and other countries in Asia, we will repeat the process with a global commercial initiative to provide affordable village electricity to a significant percentage of the billion or more people in the world who lack a connection to the electric grid.

Each dream starts with a first step, and our first step is to raise $50,000 in an Indiegogo campaign to fund the completion of the proof of concept prototype by volunteer engineers at Ball Aerospace. Ball Aerospace is providing their workshop facilities and their technicians are donating their time and talents as a contribution to this initiative. We are asking for help from the public to cover the estimated $50,000 cost of materials needed to develop, build, and bench-test the transformative proof of concept prototype.

Paul Polak's Blog

- Paul Polak's profile

- 8 followers