Paul Polak's Blog, page 2

January 31, 2014

Empowering rural women in Ethiopia

Editor’s note: This is the fourth of seven case studies from the files of iDE Ethiopia which we’re posting here to spotlight the human reality that motivates our work and gives it meaning. The people featured in these vignettes are the true heroes in the fight against global poverty.

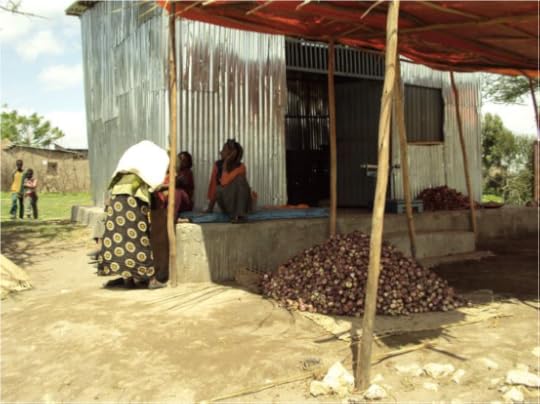

The retail shop and vegetable stall pictured here is owned by the Gudina Degagina marketing cooperative, an all-female group initiated with the support of iDE (International Development Enterprises). It’s based in Elkachelemo kebele in Adami Tulu woreda (district), Ethiopia.

At the start of 2008, 16 female smallholders began organizing producer and marketing support groups. Members were expected to pay a weekly contribution of 2 birr (about $0.10) to use as running capital. According to the members, business skill training and advisory services provided by iDE field staff helped them to start raising seedlings on a 200 square-meter plot of land given to the group by one volunteer member. These seedlings were irrigated with a rope and washer pump. ‘‘Just then, since all of us were very poor and couldn’t pick up the tab to work single-handedly, I was keen to work together,’’ said the chairperson of the cooperative.

The group raised onion seedlings twice and sold them to other iDE clients in the nearby woredas with the support of iDE field staff, earning 3,917 birr ($205). The group also earned a net income of 12,350 birr ($647) from their own onion production on rented land.

The group raised onion seedlings twice and sold them to other iDE clients in the nearby woredas with the support of iDE field staff, earning 3,917 birr ($205). The group also earned a net income of 12,350 birr ($647) from their own onion production on rented land.

To strengthen the capacity of the network, IDE provided support and training while the groups constructed the aforementioned retail shop. Due to these improvements, during last production season, the co-op harvested 162 kilograms of onion seed and earned a gross income of 40,350 birr ($2,114). They are currently cultivating their rented land, two hectares of which is dedicated to growing improved maize varieties and onion seedlings for the next production season.

The group is now a legal entity and cooperative. Membership gradually grew to 33 members, and the cooperative now has 55,000 birr ($2,881) in capital, or nearly $1,000 per member. Capital is generated from the sale of vegetables and seedlings as well as from weekly member contributions. A member of the group explained that, before, the women did not take part in any household decisions. “Now,” she stated, our working culture has changed and we’ve had a chance to actively play a part in household decision-making. We have respect, and we realized that women can be actively involved in production activities and can change their lives. We have a plan to buy a grid mill and an Isuzu.’’

January 28, 2014

Can Corporations Deliver Sustainable Development?

By Atul Wad

By Atul WadEditor’s note: This article, which came to us over the proverbial transom via email, explores some of the issues Paul Polak and Mal Warwick raised in The Business Solution to Poverty , placing them in a broader social and economic context. The author calls for a thoroughgoing re-examination of the role of corporations in the wider world, paralleling Polak and Warwick’s plea for a Business Revolution along lines sketched out in their book.

A decade ago C.K. Prahalad made the compelling argument in The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid that corporations need to go beyond corporate philanthropy and social responsibility if they seek to combat global poverty, and that by doing so they can reap larger profits and become more successful as businesses, while simultaneously achieving social good. This argument highlighted the need to examine the fundamental issues involved in the impact of globalization on the poor and underprivileged, and the implications for the role of the corporate sector.

In the first place, poverty is not the only ill that besets this huge untapped market. Millions of people around the developing world are in far more dire straits.

Poverty means more than lack of money

The underprivileged (or marginalized) population includes those affected by disease such as malaria, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, and a number of widespread tropical ailments not well known in the nations of the Global North. In various parts of the world, civil wars and state-sponsored violence, even genocide, have made tens of millions into refugees; they live in a constant state of insecurity and terror, and have virtually no economic existence except as clients of aid programs and humanitarian agencies.

Natural disasters and breakdowns in the governance of states have also added to the problem. These people are not even close to being active participants in any marketplace, unless you see millions of Africans with HIV/AIDS as being “customers” for very expensive drugs.

The plight of the poor is not just a lack of money. It is far worse. It is a lack of basic services such as water, health, education, and infrastructure; it is the corrupt environment they live within, where bribery is a fact of daily life; it is a socio-cultural nightmare for women, who have to live with abuse and marginalization; it is the existence of what can only be called a slave trade in children in many countries; it is disenfranchisement on a global scale.

The plight of the poor is not just a lack of money. It is far worse. It is a lack of basic services such as water, health, education, and infrastructure; it is the corrupt environment they live within, where bribery is a fact of daily life; it is a socio-cultural nightmare for women, who have to live with abuse and marginalization; it is the existence of what can only be called a slave trade in children in many countries; it is disenfranchisement on a global scale.

Taken in this broader perspective, the concept of livelihood, or quality of life, is a more sensible approach, in that it views the condition of the underprivileged in broader than solely economic terms – and includes issues such as security, infrastructure, representation and governance, dignity, culture, gender bias, environment, communalism, health, education, and other basic needs. This involves a rethinking of the concept of sustainable development itself – a process that is already underway in many circles in these countries.

Win-win solutions through public-private partnerships

It is from such a broader, and more complex, perspective that the role of the corporate sector, and the requirements to accomplish this role, can be articulated. Indeed, corporate philanthropy is a limited approach, and corporate social responsibility may be mostly lip service. The notion that a win-win solution that achieves social benefits and also serves corporate interests is conceptually valid and compelling, but it could be seductive, and requires a great deal more analysis, and the development of business tools, strategies, and capabilities that will enable such solutions to be implemented. It also suggests that the roles of other social actors – government, non-governmental organizations, and the social sector, broadly defined – need to be examined in a similar manner.

Central to the concept of sustainability is the role of partnerships among these actors (public-private partnerships) that can more effectively harness their collective capabilities to serve a social purpose. Equally important is the need for new knowledge and new conceptual frameworks that reflect the reality of the circumstances of the underprivileged and the socio-economic context within which they exist.

For example, it may be correct to say that everyone, including the poor, wants quality services and products and should be treated as customers. But, which products and services? Selling shampoo in India in single-serving packets is a great concept in terms of market penetration, but with the poor’s very limited household income, is this the best way to spend their money? The rural sector in India and most other developing countries, has a host of much more serious problems: lack of power and water for their farming, inadequate health and education services, weak infrastructure, and virtually no insurance. They should be seen as customers in this light – as customers for a broad range of products and services that improve their livelihood and the circumstances of their existence.

For example, it may be correct to say that everyone, including the poor, wants quality services and products and should be treated as customers. But, which products and services? Selling shampoo in India in single-serving packets is a great concept in terms of market penetration, but with the poor’s very limited household income, is this the best way to spend their money? The rural sector in India and most other developing countries, has a host of much more serious problems: lack of power and water for their farming, inadequate health and education services, weak infrastructure, and virtually no insurance. They should be seen as customers in this light – as customers for a broad range of products and services that improve their livelihood and the circumstances of their existence.

Though the collective purchasing power of the poor is enormous, buying decisions are still individual. By rampant marketing, a rural household may well end up spending its small disposable income on inappropriate products. They may spend on TVs and cosmetics and forsake savings for the education of their children and for their health needs. With the onslaught of credit cards, they may well end up borrowing against their future and securing these loans with their land. Farmers in India have even committed suicide because they could not service government loans!

Redefining the concept of the “customer”

Yes, the poor should be treated with respect and as customers, but in a broader sense – they are the customers of the government, the corporate world, NGOs, and the social sector. Their political power needs to be recognized as well; the market opportunity they represent is not simply based upon their collective spending power, but, at least in some countries, their political power. Note that in India, the poor represent 80% of the population and the electorate. Despite the great strides the Indian economy has made in the last two decades, elections routinely demonstrate this power. In the midst of this great economic advance, the rural sector had been largely neglected.

The concept of the “customer” needs to be redefined.

There are other areas where new thinking is needed, as well. For instance, the analysis of supply chains needs to include equity and environmental considerations. The real and unseen impact of globalization has been the acceleration of the search for profits by large corporations. By itself, this is not necessarily a problem, but this strategy should be based upon some sense of long-term sustainability. There is no sustainability if there is no long-term view. Supply chain management must therefore take into account equity as well as environmental and social factors.

Unfortunately, most corporations don’t have the in-house capabilities to understand and analyze these issues. The chocolate industry, for example, gained the attention of the news media because it was discovered that cocoa farms in West Africa were using child labor. Despite some efforts by the industry, the child trade still continues. To eliminate child labor requires that these major purchasers of cocoa become more intellectually involved in the problem. They must analyze the supply chains, production economics, technologies, and farming patterns in these locations – and develop business tools and strategies that address the root of the problem, which is simply that cocoa farmers find it economical to use child labor.

It is also a matter of technology and of knowing where your true competency lies. Globalization and “customerization” is often taken to mean McDonaldization. The business model here is the delivery of low-cost, standardized, and consistent food products. Notions of localized health concerns and taste patterns are largely absent from such an approach. At a time when people in the US are becoming more aware of the damage that fast food does to the public health, such a model has severe limitations. The fact of the matter is that poor people know food very well – they just don’t have enough of it.

And they have taste. A long time ago, I worked in villages in India during a drought and was given the job of distributing milk (from milk powder) and wheat to the starving villagers. I set up shop and the lines were long, but then I found out that the villagers were using the milk to paint their huts and feeding the wheat to their animals. They still ate their meager supply of chapatis and pickles, which were far tastier than anything I could give them.

What we can learn from McDonalds

What we can learn from McDonaldsBut the McDonalds model does have value. The company has managed to develop an impressive technological foundation, along with supply chains and distribution systems that enable them to deliver consistently high quality food products at economical prices to millions of consumers all around the world. The poor need good quality food at low prices: rural women spend most of their day making food, and this would relieve them of some of this burden. Corporations could find a way to use this model to deliver locally acceptable food to these markets. It could well be applied to other product areas and industries, perhaps for the delivery of medicines.

The developing world of today consists of yesterday’s colonies. The colonialists, especially the British, were extremely good at exploiting local markets with their products. They bought the raw materials, added value, and sold them back to the colonies.

Adding value in the creation and distribution of products and services is central to sustainability, but it needs to be enriched in at least two important respects. First, it needs to be localized. The conversion of raw materials and resources into higher value products should be achieved locally, so that the local economic pie is enlarged. To some extent, this is taking place through the slow and spotty expansion of national economies into rural areas, but on a limited scale. To truly enlarge this local “pie” will require more localized technological innovation and capacities, a better understanding of the market potential for such products and services, and a rethinking of the economic potential of local resources. For example, a company in India that produced ethanol from sugar cane was able, through technology and research, to find that red sorghum, a cheaper crop, could produce higher yields of ethanol per acre than sugar cane.

Secondly, since many of these countries have large agricultural sectors, the concept of waste needs to be reexamined. There is enormous waste in the agricultural sector for a number of reasons, including seasonality, the lack of storage facilities, and market fluctuations. Yet there are examples of ventures that have taken this waste and converted it into useful, value-added products. The waste from banana cultivation has been converted into biocomposites and oil absorbents, for instance. Biofuels are being made from waste fats and oils from fast-food outlets.

There is a need to view agricultural waste as a source of value, rather than an economic cost, and to explore the opportunities that may lie there. Corporate research and product development efforts need to change their search strategies to encompass this domain. They might also consider the potential of information technology in their efforts to bring benefits to the bottom of the pyramid.

Technology for the poor

Technology for the poorPractically every IT company in India is trying to “do something” in the villages. They give away handhelds and Internet access, offer real-time price information, and so forth. But, after all is said and done, a subsistence farmer is still living with his poor productivity, weak infrastructure, corrupt government officials, bad roads, and expensive water for his crops. Knowing the latest prices for his produce in the global market must give him some comfort and some economic gain, but a more useful approach may be to explore how the total value added that he can produce could be enlarged, and how IT could improve the overall quality of his livelihood.

The potential of IT for addressing the needs of the underprivileged is enormous, especially as prices decline and the reach of the technology expands. In South Africa, pilot projects have been developed to use a combination of cell phones and e-mail to expedite the transmission of medical tests from patients in remote areas to testing clinics and back to the patient.

In the financial sector, the “Equator Principles” for socially responsible investment have received a great deal of press and have been endorsed by many leading financial institutions. Yet even the International Finance Corporation (IFC), which promoted the protocol, would probably agree that its impact in terms of actual utilization has been limited. The concept is great – the limitation lies in the capabilities of the implementation structure. In India, rural financial institutions, which are mainly government-controlled, lack the in-house technical abilities to conduct the proper analyses, and fall back on the more traditional criteria. Someone made those loans to those suicide farmers. Notably, some private corporations have developed innovative services to reach the rural sector, and there is the success of micro-finance in some countries. One would hope that such positive examples are built upon and that better models and tools are developed.

Redefining capitalism

The underlying thread in all of this is that corporations need to expend a great deal more intellectual energy to identify more precisely the areas where they can make the most sensible contributions to society and simultaneously serve their corporate interests. Essentially, this requires examining every functional dimension of business and developing the analytical tools, relationships, and strategies that would make them more effective.

In 2003 Raghuram Rajan and Luigi Zingales of the University of Chicago Booth School of Business wrote Saving Capitalism from the Capitalists. Perhaps that’s what is really needed – a redefinition of capitalism. Corporations need to understand that by pursuing socially responsible objectives they will benefit as businesses. There is nothing inherently conflicting between corporate goals and sustainable socioeconomic progress, except that most corporations don’t have the knowledge base or the capabilities to address both ends meaningfully.

It is ultimately an issue of knowledge. The production of knowledge that can be used to address these issues is such an important need that it should probably become a new interdisciplinary field. Corporations have designated directors of social responsibility, but for the most part their leaders don’t really want to do much more than that, and business schools, for the most part, don’t dive any more deeply into the matter, either. It’s time for the business sector as a whole to take a long, hard look at its central role in the new world that’s emerging – a world of eight or nine billion people, most of them people of color who live in the Global South, many of them poor – and determine how best to help themselves by helping all the rest of us.

Atul Wad (atulbwad@gmail.com or atul.wad@tambourinetechnologies.com) is a Visiting Fellow at the Center for Research on Innovation Management of the University of Brighton, UK. He has been involved in sustainable project and business development in developing countries for over 25 years. He works with corporations, government organizations and international development agencies. He has a Ph.D. from the Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University, and a B. Tech from the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay.

January 24, 2014

An Ethiopian success story

Editor’s note: This is the third of seven case studies from the files of iDE Ethiopia which we’re posting here to spotlight the human reality that motivates our work and gives it meaning. The individuals featured in these vignettes are the true heroes in the fight against global poverty.

Editor’s note: This is the third of seven case studies from the files of iDE Ethiopia which we’re posting here to spotlight the human reality that motivates our work and gives it meaning. The individuals featured in these vignettes are the true heroes in the fight against global poverty.

Kedir Beriso, 52, is a smallholder farmer living along with his three wives and eleven children in Keraru Kebele in Arsi Negelle woreda in Ethiopia. He owns 2.5 hectares (six acres) of irrigable land, where he previously relied on rain to grow maize and wheat. He also grew coffee and mango plants on a tiny portion of this land, which he would water with buckets. According to Kedir, cultivating this land took more than five years, starting from 2006.

After getting the necessary information about the manual irrigation from iDE (International Development Enterprises) field officers, Kedir decided to purchase a treadle pump in June of 2010 with his own cash. In the first production season after purchase, Kedir raised 2,000 coffee seedlings and sold 1,000 of them for 2,000 birr (2 birr each), or about $104. He transplanted the remaining 1,000 seedlings to another area of his land where he could better irrigate them using the treadle pump. About two-thirds of these seedlings survived the first year. Kedir also bought 30 mango and 15 papaya seedlings from the nearby village in hopes of more diverse fruit production in the future.

Kedir claims that the extension services that he received from iDE field officers enabled him to get 4,000 birr from the sale of coffee seedlings and peppers. Kedir continued his effort and earned 12,000 birr from the sale of onions and kale in the next production season.

After the intervention, by iDE, Kedir’s income totaled 16,000 birr ($832): 4,000 from the sale of coffee seedlings & pepper, and 12,000 from the sale of onions and kale. His cost of production was just 1,300 birr ($68), leaving him with net income of 14,700 birr ($765).

As a result of the increased income, Kedir was able to purchase wheat and maize grains (which his families are using for consumption now) and a diesel pump, which can irrigate two hectares of improved maize crops. Kedir has a plan to further cultivate his land using both the treadle pump and the diesel pump in the future.

As a result of the increased income, Kedir was able to purchase wheat and maize grains (which his families are using for consumption now) and a diesel pump, which can irrigate two hectares of improved maize crops. Kedir has a plan to further cultivate his land using both the treadle pump and the diesel pump in the future.

January 21, 2014

Ending poverty — guaranteed?

By Mal Warwick

By Mal WarwickAs Paul Polak and I have made the rounds discussing The Business Solution to Poverty, we’ve been confronted by a question that arises out of deeply held skepticism — or, not to put too fine an edge on it, cynicism. Occasionally, the doubts are voiced. More often, they lurk in the background. Here’s that question in its unvarnished form:

“What makes you guys think these companies you’re writing about will stay mission-driven, focused on the Bottom of the Pyramid, once they’ve started growing fast? Won’t they become just like any other multinational corporation, profit-driven and predatory?”

This question deserves a candid answer.

Obviously, there is no guarantee that any company, or any nonprofit organization, will stick to its mission forever. Mission-creep is all too common in the nonprofit world and, until recently, was rarely considered a problem within the business community despite how common it is. In fact, strategic planners tend to encourage shifting missions from time to time to adjust to changing circumstances. However, there are four factors that Paul Polak and I believe will support the mission-focus on which the companies we advocate are founded:

1. By virtue of their very focus on selling “ruthlessly affordable” products and services to poor people, these companies will present far fewer opportunities for profiteering than do most business enterprises. If you have to design ruthlessly affordable products and services for the discriminating customers at the Bottom of the Pyramid, you’re likely to fail when you try to sell them something different — or raise prices unreasonably. Sure, faulty or overpriced products might sell for a time — but soon the word will get around and the profits will come to an end. People, especially those living on $2 a day, can’t afford to spend money unless they get real value from what they’re buying.

2. The companies we propose to build — and that Paul is building — must hire all their employees locally and be organized as stakeholder-centered businesses. In other words, they must cater to their customers, their employees, the communities where they do business, and the environment as well as their shareholders if they’re simply to survive. Why? Because if they don’t satisfy all the key players, they’re quite likely to be forced out of business either by governments or by popular demand. Rich-country enterprises are fast learning the disadvantage they face if customers perceive they aren’t treating their employees or the environment well; in developing countries, public acceptance of businesses that set up shop locally is even more fragile. They constantly have to demonstrate the value they add to the local society. Every company faces reputational risk when it enters a market — and nothing can kill a brand faster than a widespread public perception that a company is acting badly.

3. As we emphasize in The Business Solution to Poverty, these companies must be designed from the outset to deliver handsome profits. These are high-risk ventures, because they’re entering largely unexplored markets, so any investors that back them will expect higher than usual returns on their investments. And it’s highly likely that the companies’ profitability will rise as they expand, as a result of economies of scale, institutional learning, and refinement of production, distribution, and marketing techniques. In other words, it’s far from certain that the future leadership of these companies will be tempted to veer off-mission and adopt the exploitative ways of so many existing businesses.

4. We don’t envision that these companies will market exclusively to $2-a-day customers in perpetuity — because, if they succeed, their customers’ income will rise, in some cases quite considerably. As customers’ income grows, they’re likely to become interested in higher-value products — and these companies can supply them, capitalizing on the brand loyalty that they’ve instilled among the poor. The result? LIke Toyota captured the economy market with its low-price Corolla and only later introduced more and more expensive models, these companies will grow as their customers become more affluent.

For sure, there is some possibility that one or another of the mission-driven businesses we write about will be forced off the rails by greedy managers or investors. However, we think the built-in safeguards, and the nature of the societies where they do business, will keep such incidents to a minimum.

January 17, 2014

A treadle pump transforms the life of an Ethiopian farmer

Editor’s note: This is the second of seven case studies from the files of iDE Ethiopia which we’re posting here to spotlight the human reality that motivates our work and gives it meaning. The individuals featured in these vignettes are the true heroes in the fight against global poverty.

Editor’s note: This is the second of seven case studies from the files of iDE Ethiopia which we’re posting here to spotlight the human reality that motivates our work and gives it meaning. The individuals featured in these vignettes are the true heroes in the fight against global poverty.

Wado Edo, 50, is a resident of Abayi Deneba village in Adami Tulu woreda, Ethiopia. He has a family of twelve (4 females and 8 males), with only a one-hectare (2.5 acres) plot of land with which to earn an income to support them all.

According to Wado, his life has been improving since he bought a suction-only treadle pump on a loan basis through microfinance institutions with the support of iDE International Development Enterprises). Wado explains:

“Before adopting the technology, I used to grow maize by rain [once a year], which barely covered the needs of my family. After purchasing the pump and getting the necessary extension services, I covered about 0.125 hectare of my land with vegetables; kale, chili pepper, and onion and earned a total income of Birr 9,100.00 ($730) in four months’ time.

“At that time, it was too much for a poor family like ours. We have never earned such an amount throughout our family life. The income that I got from the first production gave me courage and helped me to expand my business. Now I have an ox. I can properly feed my children unlike the previous years. All of my children are going to school; I am helping one of my daughters apply to Jimma University, and I also rented a house for another daughter attending a high school in the nearby town of Tulu. I also have ambition to support her up to the highest level I can. It makes me to be self-reliant and my neighbors start to consider and respect me as hard worker. Moreover, we never before had access to relatively dirt free water that can be used for household consumption. Thanks be to IDE, I will work even harder to transform my life.”

After Wado began using the treadle pump, his total annual income included Birr 2,700 from chili pepper; 1,650 from kale; and 5,500 from onions, or Birr 9,850 ($730) all told.

Wado’s cost of production for the year included the following:

Cale seed Birr 15

Chilly seed 25

Onion seed 140

Sprayer 150

Pesticide 300

Payments on pump 1,200

Wado’s total production cost for the year was thus Birr 1,830.

With the implementation of the suction-only treadle pump, Wado netted an additional Birr 8,020 ($594) from a single season of vegetable production.

January 13, 2014

Eyeglasses for the world

By Paul Polak and Mal Warwick

By Paul Polak and Mal WarwickOn January 2 this year, The Guardian revealed that a German physics teacher had been inspired by Paul’s book, Out of Poverty, to produce $1 eyeglasses and market them in Rwanda.

Martin Aufmuth, founder of OneDollarGlasses, created a hand-operated milling machine that allows opticians to produce his glasses at a cost of $1 apiece after 14 days of training. To enable the local specialist to turn a profit, the glasses sell for between $2 and $7, according to The Guardian.

According to Vision Aid Overseas, some ten percent of the world’s population are vision-impaired, and eyeglasses could correct the vision problems of virtually all of them — sometimes making an enormous difference in their lives. For example, for a tailor in a hill village in Nepal who no longer can see to sew, a pair of affordable eyeglasses makes the difference between earning a living and becoming a beggar.

Usually beginning in their forties, many people become unable to focus their vision on near objects, a condition called presbyopia. Today you can go into a drugstore in Denver or Amsterdam and select an eight-dollar pair of reading glasses that will correct your vision problem. Why not make a robust version of this display stand available to the nearly 700 million poor people in the world who need eyeglasses?

Give me a market so I can see

Adaptive Eye Care, a UK-based company, uses the invention of an Oxford physics professor, Joshua Silver, to bring self-adjusting eyeglasses to people who need them. The constraint here is the cost — fifteen dollars now, perhaps ten dollars or less with volume, but still not affordable to people who earn less than $2 a day.

New Eyes for the Needy, a US-based organization, shipped 355,000 donated used eyeglasses in good condition during 2005-2006 to medical missions and charitable organizations in developing countries. The problem here is that giving glasses away is not a scheme that can be scaled up to reach more than a tiny fraction of the people who need them.

In first five years alone, New York–based VisionSpring (formerly Scojo Foundation) and its partners sold 50,000 reading glasses, at prices from three to five dollars, in India, Bangladesh, and El Salvador, and referred 70,000 people to eye-care professionals through a network of six hundred vision entrepreneurs, twenty-six franchise partners, and a number of urban wholesalers distributing to pharmacies and other retail outlets. Now, eight years after its founding, VisionSpring glasses are being worn in 26 developing countries. The organization employs a systematized partnership model that works with microfinance institutions, NGOs, for profit businesses, and social enterprises.

Graham Macmillan, former executive director of what was then called Scojo Foundation, told Paul that a surprising number of small-acreage farmers were enthusiastic customers for affordable eyeglasses, because without these glasses they can’t read the labels on seed packages. Some of them don’t know what crop they are planting until it begins to come up.

The combined efforts of Scojo, New Eyes for the Needy, and Adaptive Eyecare have reached less than one percent of the 670 million poor people who need eyeglasses. The rest live with serious visual problems, paying a significant price in lost income because they can’t see straight — while society pays the price of their lower productivity.

This is outrageous, because there is such a simple solution in taking advantage of uncomplicated eyeglass display stands that already sell affordable eyeglasses to millions of wealthier customers. It would take five to ten million dollars in venture capital to start an international company that would buy a million eyeglasses in mainland China at around fifty cents apiece, design robust, visually appealing mobile display stands pushed by people or pulled by bicycles or motor scooters in poor areas, perhaps forming partnerships with major corporations such as Tata in India, developing an effective global distribution and marketing strategy. The company’s goal would be to reach sales of 50 million $2 eyeglasses within five years, and make a healthy profit doing it.

One-acre, $2-a-day farmers and their urban brothers and sisters are already hard-nosed, stubborn survivalist entrepreneurs ready to take advantage of marketplace opportunities if the price is right, the return is high, and the risk is low. But they need private-sector supply chains to furnish them with the tools, materials, and information required to create high-value products, and private-sector value chains that sell what they produce at an attractive profit. As their incomes increase, they become customers for products like affordable eyeglasses, houses, solar lighting, health care, and education. New markets that serve poor customers will provide opportunities for hundreds of millions of dollar-a-day people to move out of poverty. But a revolution in design is needed to create the range of new income-generating tools that will make this move possible.

Editor’s note: Some of the material in this article was adapted from Out of Poverty by Paul Polak.

January 10, 2014

Case study from Ethiopia

By iDE (International Development Enterprises)

By iDE (International Development Enterprises)Editor’s note: This is the first of seven case studies from the files of iDE Ethiopia which we’re posting here to spotlight the human reality that motivates our work and gives it meaning. The individuals featured in these vignettes are the true heroes in the fight against global poverty.

Asnakech Nigussie, 39, is the single mother of two children and lives in Shubi Gemo Village in Dugda Woreda, Ethiopia. Before she was able to start making a living from agriculture, Asnakech made money by selling a local liquor called arekie. She says that her son was forced to work as a laborer at a very young age, but even this additional income wasn’t enough for the family. Asnakech expresses her desperation:

“No one could have supported me to improve my life since I am very poor. The income I used to get hardly covered the basic needs of my children. We lived from hand to mouth all the time. Since I don’t have oxen and money to seed my small plot of land (1 hectare), I used to rent it out to others so that they will share with me half of the grain at the time of harvest. Getting even small amounts of money from neighbors was difficult for me. The local money lenders would tell me to come one day and when I went, they would tell me to come back another day because they knew that I had nothing.”

According to Asnakech, she often couldn’t pay back her loans on time and the moneylenders were forced to reclaim the grain that she used the loans to purchase. As a result of not having anything to plant Asnakech had to rent out her land for a very low price in order to make money for living expenses.

The iDE field staff heard Asnakech’s story and facilitated her interactions with the local microfinance institution. She used the money she borrowed to buy a rope and washer pump and have it installed on her hand-dug well. With the extra water the pump provided, she managed to grow vegetables, such as chili peppers and kale, on her backyard 500m2 plot.

‘‘The first produce I sold earned Birr 5,650.00 [a little less than $300], and that was unbelievable to me,” she says.

‘‘Later I also took a second loan of 1,500 Birr [about $78] that helped me to further expand my business and buy all the necessary inputs, including the wages of daily laborers. I harvested 12 quintals of maize and sold part of it for Birr 1800.”

Asnakech’s total income before the intervention, which came from the sale of the local drink, was 1,100 Birr per year, or about $57. After iDE’s intervention, her income consisted of the following:

Chili pepper 3,750 Birr

Kale 1,150 Birr

Pepper seedling 750 Birr

Maize 1,800 Birr

Total Income 7,450.00 Birr

Meanwhile, Asnakech’s cost of production was just 1,690 Birr ($88), which included:

Kale seed 15 Birr

Chili seed 25 Birr

Pesticide 150 Birr

Cost of RWP 1500 Birr

Total cost 1,690.00 Birr

Thus, her net income within one season rose from $57 to 5,760 Birr, or $427. On an annual basis, she earned net income of 11,520 Birr, or $853.

Asnakech says, “I continued working hard, and by now I own an ox and two sheep, I have enough grain that I can feed my family properly, and both of my children are now going to school. We also have access to clean water from the pump that can be used for household consumption in our dwelling.”

Asnakech credits iDE for making her motivated, hardworking, skillful, and self-reliant. She is proud of the support she has received and has pledged to work even harder in the future.

January 3, 2014

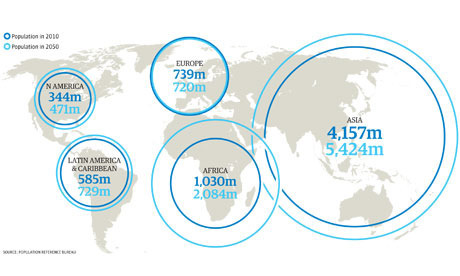

The challenge of poverty — in graphics

Sometimes things don’t become clear until you can see them right in front of you. Here, just in case you’re one of those folks who relates to images better than to the written word, are the raw facts that led Paul Polak and me to write The Business Solution to Poverty.

December 31, 2013

The Design Revolution is underway

A young woman tries out the Remotion Knee, a product of D-Rev (Design Revolution). Photo by D-Rev.

By Mal Warwick

A lengthy article in yesterday’s New York Times (“Solving Problems For Real World, Using Design“) called attention to the sea change underway in the field of design.

Not so very long ago, designers trained for specialization in a limited number of fields such as fashion, graphic, or product design. Today? Not so much.

At such leading-edge universities as Stanford and MIT, design is no longer regarded the way much of the public still thinks about it (making things pretty). Design, as all designers know, is about problem-solving, pure and simple. And, increasingly, both within the walls of academia and outside, designers are turning their attention to real-world problems, especially those of the global poor.

The Times article focuses on the Stanford “D.School,” citing in particular a course entitled “Design for Extreme Affordability,” which my coauthor Paul Polak helped create several years ago. The course, which is routinely oversubscribed, brings together students with people from around the world to work together solving everyday challenges such as the need to keep newborn babies warm when the parents can’t afford rich-country solutions. MIT has a similar program (called D-Lab) under the leadership of Amy Smith.

Away from the campus environment, a San Francisco-based nonprofit organization called D-Rev (founded by Paul Polak) bills itself as “a product development company whose mission is to improve the health and incomes of people living on less than $4 per day.” D-Rev has produced several successful products for its target market since its founding in 2007, including the versatile Remotion Knee for amputees (pictured above), an affordable microscope for detecting malaria and TB in rural clinics, and affordable methods for pasteurizing milk for East Africans.

These developments — collectively called “Design for the Other 90%” in the popular phrase Paul Polak coined — informed our writing in The Business Solution to Poverty. In the book, we tackled a broader challenge than that of designing affordable products that could succeed in the market. Our task involved systems design, as we’d set out to design from the ground up the enterprise that could create and produce affordable products or services, successfully market them to people living on $2 a day or less, and grow to global scale, reaching at least 100 million customers within a decade.

We called this process zero-based design.

Look to this blog for information about zero-based design in the weeks ahead.

December 27, 2013

Is There a Limit to the Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid?

By Paul Polak and Mal Warwick

By Paul Polak and Mal WarwickIt’s a rare honor for an author’s work to be addressed in the pages of Foreign Policy magazine, as is The Business Solution to Poverty in Daniel Altman’s recent column. However, in our case, the pleasure is multiplied because Mr. Altman’s column provides us with an opportunity to address two significant issues that received too little attention in our book.

Mr. Altman takes the position that the potential for profit at the bottom of the pyramid is severely limited because the total buying power of people living on $2 a day or less amounts to only $1 trillion globally, and little of that money will be available to purchase products and services from the new companies we’re starting to build. He adds that the 2.8 billion poor represent a fragmented and scattered market dispersed across the globe and, in many cases, outside the bounds of cost-effective distribution.

Let’s take those two issues one at a time.

The dispersion of the bottom billions

It’s true, of course, that the $2-a-day customer base we write about is scattered among a total of perhaps 100 countries. After all, there are 48 nations in Africa south of the Sahara alone, and many of them are tiny. However, by emphasizing that as many as half the world’s poor live in China and India, Mr. Altman ignores the reality that the lion’s share of the remainder live in other large countries. Consider the following population figures:

It’s true, of course, that the $2-a-day customer base we write about is scattered among a total of perhaps 100 countries. After all, there are 48 nations in Africa south of the Sahara alone, and many of them are tiny. However, by emphasizing that as many as half the world’s poor live in China and India, Mr. Altman ignores the reality that the lion’s share of the remainder live in other large countries. Consider the following population figures:

Indonesia (251 million)

Brazil (201 million)

Pakistan (185 million)

Nigeria (174 million)

Bangladesh (152 million)

Mexico (118 million)

Philippines (99 million)

Vietnam (90 million)

Ethiopia (87 million)

Egypt (84 million)

Take Egypt, for example, the least populous of these ten countries. Egypt is a nation of 84 million people, 20 percent of whom live below the official World Bank poverty line of $1.25 a day. An Egyptian scholar has calculated that overall about 44 percent of the population are in the range of extreme poor to near poor, which is roughly equivalent to the $2-a-day standard we use. That 44 percent represents approximately 37 million people. Would Mr. Altman suggest that 37 million potential customers in a single country wouldn’t constitute a large enough market for one of our companies?

Now let’s turn to the matter Mr. Altman emphasized even more strongly.

Is $1 trillion a big enough market?

Mr. Altman’s view is that the aggregate global buying power of people living on $2 a day is only about $1 trillion – a significant sum, surely, but, he implies, not nearly enough to create a whole new generation of frontier multinationals. However, this argument misses the key point. Right after graduating from medical school, Paul took a job as an intern at Montreal General at a salary of $40 a month. Was his buying power $2 a day? Perhaps. But three years later it was $40 a day, and $100 a day not long after that. The real market potential of poor people is not what they’re earning now, but the vast untapped human and earning potential that resides within most of them. And that potential can be unlocked, not by selling them toothpaste or other consumer products common in wealthy countries, but by marketing a whole new range of affordable, livelihood-enhancing products and services.

Mr. Altman’s view is that the aggregate global buying power of people living on $2 a day is only about $1 trillion – a significant sum, surely, but, he implies, not nearly enough to create a whole new generation of frontier multinationals. However, this argument misses the key point. Right after graduating from medical school, Paul took a job as an intern at Montreal General at a salary of $40 a month. Was his buying power $2 a day? Perhaps. But three years later it was $40 a day, and $100 a day not long after that. The real market potential of poor people is not what they’re earning now, but the vast untapped human and earning potential that resides within most of them. And that potential can be unlocked, not by selling them toothpaste or other consumer products common in wealthy countries, but by marketing a whole new range of affordable, livelihood-enhancing products and services.

Mr. Altman appears to have fallen prey to the misconception that the objective of lifting people out of poverty is to transform them into American-style consumers who will fritter away their limited resources on trivialities. That’s most certainly not the case. The businesses we promote in The Business Solution to Poverty and are building on the ground are conceived to add real value to the lives of their customers. As thousands, then millions, then tens of millions of people’s incomes rise from $2 a day to $5 or $10, the new wave of multinational companies will market such products as truly durable appliances, nutritious soft drinks, and healthful tea biscuits – desirable rather than essential, surely, but with value added.

Even if Planet Earth could support seven or eight billion people living at the level of current American lifestyles – and it most assuredly cannot – why would we want to replicate a set of social values that have failed to foster even the level of happiness already experienced by many poor people around the world?

Paul Polak's Blog

- Paul Polak's profile

- 8 followers