Paul Polak's Blog, page 3

December 24, 2013

Inequality, Infant Mortality, and Foreign Aid

A review of The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality, by Angus Deaton

A review of The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality, by Angus Deaton@@@@ (4 out of 5)

BY MAL WARWICK

Has the human race made progress since the days when all our lives were nasty, brutish, and short?

Some might think this question patently silly, since it would appear to answer itself. But Angus Deaton finds in it a point of entry into his inquiry on “health, wealth, and the origins of inequality,” the subtitle of his ambitious new book. He is in no doubt that humanity has progressed, not steadily but by fits and starts — and continues to do so to this day. “Today,” he writes, “children in sub-Saharan Africa are more likely to survive to age 5 than were English children born in 1918 . . . [and] India today has higher life expectancy than Scotland in 1945.”

The roots of inequality

In The Great Escape, Deaton, a veteran professor of economics and international affairs at Princeton, explores inequality — between classes and between countries — with a detailed statistical analysis of trends in infant mortality, life expectancy, and income levels over the past 250 years. He concludes that the large-scale inequality that plagues policymakers and reformers alike in the present day is theresult of the progress humanity has made since The Great Divergence (between “the West and the rest”) since the advent of the Industrial Revolution. “Economic growth,” Deaton asserts, “has been the engine of international income inequality.”

No argument there: Deaton is far from alone in this belief. Other scholars have written extensively about this topic in recent years. A Farewell to Alms: A Brief Economic History of the World, by Gregory Clark, is just one example.

Late in the 18th Century, the countries of Northern Europe and North America on the one hand and those of Asia, Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America on the other hand were not that far apart as measured by the available indicators of health and income. Deaton cites “one careful study [that] estimates that the average income of all the inhabitants of the world increased between seven and eight times from 1820 to 1992.” However, that average obscures a harsh reality. The ever-quickening rate of change in “the West” since 1760 or so has widened the gap between (and within) countries to an extreme degree. Deaton terms the freedom from destitution and early death that so many of us now enjoy “The Great Escape,” taking his title from the 1963 film of that name about a massive escape of prisoners from a German P.O.W. camp in World War II.

Closing the gap

Only now is the gap closing between the rich nations and China and India (by far the world’s two biggest countries, with nearly 40 percent of the planet’s population and half the world’s poor). Deaton doesn’t consider a bright future for all a certainty, not by any means, in view of global climate change and the ever-present threat of killer pandemics. But, assuming the species continues to thrive, there is sufficient data available now to have some confidence that the gross inequality now existing among nations will not persist forever. After all, five sub-Saharan African countries are now growing their economies faster than China’s.

However, that misleading factoid ignores the outsize role that China has played in “the Great Escape” globally. Deaton notes, as have other observers, that “the number [of] people in the world living on less than a (2005) dollar a day fell from about 1.5 billion in 1981 to 805 million in 2008 . . . [This] decline in numbers is driven almost entirely by the Chinese growth miracle; if China is excluded, 785 million people lived on less than a dollar a day in 1981 compared with 708 million in 2008.” (This reality is one of the principal reasons why Paul Polak and I insist in The Business Solution to Poverty that traditional methods to end poverty have largely failed. After all, China’s methods were hardly traditional!)

The sad record of foreign aid

In the course of exploring the historical record of growing inequality on the world stage, Deaton delves deeply into the role of foreign aid (officially, Overseas Development Assistance, or ODA) and finds it comes up short. ”You cannot develop other countries from the outside with a shopping list for Home Depot, no matter how much you spend,” he writes. With the exception of outside interventions in public health programs — including such breakthroughs as the eradication of smallpox and the near-success with polio — Deaton finds that foreign aid has done more harm than good. He argues that where the conditions for development are present, outside resources are unnecessary. Where they’re absent, ODA entrenches local elites, distorts the local economy, and discourages local initiative. The author insists that “the record of aid shows no evidence of any overall beneficial effect.”

But that’s only part of the story.

In 2012, ODA totaled about $136 billion. Throw in another $30 billion or so from NGOs, and total outside assistance comes to under $200 billion annually. However, net resource transfers from developing countries to rich countries are well in excess of $500 billion annually. (Transfers reached a peak of $881 billion in 2007, fell with the Great Recession, but are rising again.) Quite apart from the fact that an estimated 70 percent of “foreign aid” is actually spent on products and services from donor nations, ODA merely puts a dent in the huge disadvantage that poor countries suffer as a result of lopsided trade policies and prevailing political and commercial imbalances. In any case, just one factor in those resource flows — remittances from overseas residents of poor countries to their families back home — are twice as large as ODA.

The Great Escape is a worthy effort from a senior scholar whose wide-ranging studies have led him to big-picture conclusions. Policymakers and practitioners should be listening carefully.

December 19, 2013

Winter Newsletter

For the latest news about Spring Health and SunWater, two of the companies Paul is building to combat poverty on a global scale — plus a handy guide to some of the many articles that have appeared about The Business Solution to Poverty — click below:

For the latest news about Spring Health and SunWater, two of the companies Paul is building to combat poverty on a global scale — plus a handy guide to some of the many articles that have appeared about The Business Solution to Poverty — click below:

December 17, 2013

Is it Wrong for Business to Profit from the Poor?

By Paul Polak

By Paul PolakMohammad Yunus is a nice man. He’s also very smart, innovative, a risk-taker — and a winner of the Nobel Prize for Peace. However, he is sometimes wrong. And he’s most certainly wrong when he insists, as he has done so frequently in recent years both in his books and in public appearances, that the solution to global poverty lies in forming “social businesses” that never distribute profits to investors.

“Poverty should be eradicated,” Yunus asserts, “not seen as a money-making opportunity.” He believes that investors in social businesses should only get their money back. In my view, that adds up to a sizable interest-free subsidy, which constrains the potential for scale. In other words, the “solution” he advocates is no solution at all, since it limits the appeal to philanthropists who are willing to loan money at zero interest and hope for repayment in depreciated funds.

Philanthropy can accomplish many good things. But can’t eradicate poverty. There’s simply not enough philanthropic money available on Planet Earth to transform the lives of the 2.7 billion people who live on $2 a day or less.

The microfinance movement and the combined work of International Development Enterprises (iDE) have probably helped about 50 million extremely poor people move out of poverty. Even if that number is twice as large, or 100 million, it amounts to less than 4% of the 2.7 billion living in poverty. This is pitiful!

How can we successfully achieve scale?

I define meaningful scale as any strategy or initiative capable of helping a minimum of 100 million people living $2 a day move out of poverty by at least doubling their income. We urgently need to find ways to bring to scale the few comparatively successful models for development that are available.

What are the common features of initiatives that have truly helped extremely poor people move out of poverty?

They begin by thoroughly listening to poor customers and thoroughly understanding the specific context of their lives.

They design and implement ruthlessly affordable technologies or business models.

Energizing private sector market forces plays a central role in their implementation.

Radical decentralization is integrated into economically viable last-mile distribution.

Design for scale is a central focus of the enterprise from the very beginning.

Mal Warwick and I describe these concepts in detail in our recent book, The Business Solution to Poverty.

It is clear that all of these factors are integral components of a business system, but this takes us back to the original question: should it be a business system that enhances the livelihoods of poor people without making a profit for outside investors? Or should it make a profit for investors as well as the poor people who are served by it?

To me the answer is obvious. The only way for a business to help at least 100 million poor people move out of poverty is to follow the laws of basic economics, which means providing an opportunity for both poor and rich investors to earn what they consider to be an attractive profit from their participation.

Village customer in eastern India buying safe drinking water from Spring Health, a company founded by Paul Polak and staffed exclusively by Indians.

I have no doubt that there are huge profitable virgin markets all over the world serving $2-a-day customers waiting to be tapped. By the laws of economics, creating a new market requires taking a very large risk, and the reward should be commensurate with the risk. If the new venture is successful, all the investors – the poor customer who buys the product, the shopkeeper who sells it, the company employee who makes or transports the product or manages the supply chain, and all the financial investors in the company – should make attractive profits.

Here is an example: Coal contributes 40% of global carbon emissions and releases millions of tons of heavy metals and other pollutants every year, worsening climate change and sickening people around the world. Properly carbonized biomass can be substituted for coal and co-fired alongside it in proportions up to 80%. The world’s farmers produce four billion tons of agricultural waste each year. If 100 million tons of this agricultural waste could be effectively and affordably carbonized in decentralized rural settings, a multinational enterprise finding a cost-effective way to make it happen could reach global sales of $10 billion a year within five to ten years. Such a company would not only provide attractive profits to investors willing to take on the substantial risk involved, but would furthermore double the incomes of at least 100 million $2-a-day enterprise participants in developing countries.

Thai farmers threshing rice, a process that leaves rice husks behind, a valuable agricultural byproduct.

The only way a company like this can reach scale is with the financial backing of for-profit venture investments. And the only way to justify those comparatively high-risk, early-stage investments is if the company provides the opportunity to make exceptionally good profits if it succeeds.

We have two options. One is to keep hoping that governments will come through with billions of new aid dollars, keep asking individuals to dig deeper for charity dollars, and hope that the low-or-no-profit venture capital space Mohammad Yunus profers takes off and becomes a truly global phenomenon. We could plod along full of hope but low on results, celebrating increases in impact of fractions of a percentage point.

The other option is to blend the designer’s sensibility, the artist’s creativity, the ground-level aid worker’s understanding of local context, and the entrepreneurs’ dynamism and drive for success, and create profitable global companies that serve poor customers with products and services that help them rise out of poverty. We could unleash the full power of the greatest force in human history – profit – and start ending poverty by the hundreds of millions.

It would be immoral to do anything else.

December 13, 2013

Fighting Poverty in India with Safe Drinking Water

Recently I viewed a remarkable interview on Indian TV with Jacob Mathew, whom Paul Polak considers his partner in Spring Health India. Jacob’s articulate account of the company’s work is far better than anything I might write here.

To access the 14-minute interview, click here.

Once you view the video, you should understand without difficult why I invested personally in Spring Health after I began work with Paul on The Business Solution to Poverty. I’m thrilled to have the opportunity to play a small role in improving the health of villagers in East India and helping them save the money they would otherwise spend on ineffective home remedies, counterfeit drugs, and often fraudulent healers.

If the link above doesn’t work for you, copy and paste this URL into your browser: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5EA2U4orcFI

December 10, 2013

“How did you two guys get together?”

By Mal Warwick

By Mal WarwickThe query in the title is one of the questions I’ve encountered most frequently over the past several months as Paul Polak and I have been promoting The Business Solution to Poverty around the country. So, to forestall more time lost on the road, here’s the answer:

It was all Steve Piersanti’s fault.

Both Paul and I had had books published by Steve’s company, Berrett-Koehler Publishers. Mine (Values-Driven Business, with Ben Cohen) came out in 2006, Paul’s (Out of Poverty) in 2008. I’d followed up my book by serving as editor of a series of six additional titles in the Social Venture Network Series. Steve wanted Paul to keep his nose to the grindstone with a follow-up, too – a second book. Paul had other ideas. Despite frequent attempts by Steve to persuade him to plan a second title, Paul insisted that he didn’t have the time. He was too busy doing the things Steve wanted him to write about.

Then Steve took another tack: he suggested Paul work with a coauthor. He even managed to hold a meeting in the Berrett-Koehler offices in San Francisco to explore the possibility with a couple of friends Paul thought might be interested. They met with Karin Hibma Cronan and Michael Cronan from the illustrious design firm, Cronan, and John Danner, a professor at the Haas School of Business at UC Berkeley, but they couldn’t come up with a qualified co-author whom Paul and Steve both felt had the time and capacity to work with Paul and complete a manuscript within 12 months. So, Steve realized he’d have to resort to unorthodox measures.

Meanwhile, I had reviewed Out of Poverty on my book review blog. I entitled my review “A brilliant rural development specialist shares his ideas on ending poverty in the world,” which will give you some sense of what I thought about Paul. (You can read the review here.)

I can’t recall exactly on what pretext Steve informed me about his difficulty in finding a writing partner for Paul, but somehow it happened. That was in May 2012. Not suspecting Steve’s motives, I asked whether I might fit the bill, and that’s all it took. In short order, I was on the phone with Paul for an hour-and-a-half conversation that persuaded each of us that we could have a lot of fun working together. We submitted a formal proposal to Steve in June and got started writing in July, once we’d received approval from Berrett-Koehler’s Publication Board. Six months later – voilà! – we delivered the manuscript to Steve.

Now you know. Aren’t you sorry you asked?

December 4, 2013

Sun-Powered Irrigation

By Jack Keller, P.E., Paul Polak, Paul Storaci, and Robert Yoder

By Jack Keller, P.E., Paul Polak, Paul Storaci, and Robert YoderA note from Paul Polak:

This is the last paper my dear friend and soul brother, Jack Keller, wrote, He died recently at the age of 85 at an IDE social gathering, in the middle of an animated discussion on politics, He put down his wine glass, said he wasn’t feeling too well, and collapsed in the arms of a fellow board member. He died doing what he loved, which is the way I hope to go when my time comes.

This article describes our dream of replacing millions of diesel pumps in the world with radically affordable solar pumps. In typical Jack Keller style, he included me, Bob Yoder, and Paul Soraci as co-authors, although he wrote every word of it.

Jack was a deeply spiritual, world class engineer who wasn’t afraid of getting his shoes dirty. Our collaboration on affordable solar pumping represents the way he lived all his life: dream big, make it happen, and die trying. On the day he died, he flew to Denver from an IDE project in Honduras, ready to fly on after the Denver board meeting to pursue still another dream in Myanmar.

For me, this article represents a celebration of Jack’s life embedded in an expression of one of his dreams. His spirit will live on in my work.

I hope you enjoy it, and capture some of Jack’s spirit for you own dreams as you read it.

If poor farmers in Ghana, India, or China want to water small plots of vegetables to sell in the local market, they break their backs hauling water in buckets or sprinkling cans from a nearby stream. It takes six hours a day, every other day, for three months to water 400 m2 (0.1 acre) of vegetables, which they hope to sell for $100 US. In India and Nepal, a treadle pump that costs less than $100 will irrigate as much as 0.2 ha (0.5 acre) with about six hours a day of work. (The photo on the right pictures a young Bangladeshi farmer showing off the treadle pump her family uses.)

A five-horsepower diesel pump can irrigate 1.0 ha (2.5 acres) of vegetables, but it costs $500, plus $450 a year for diesel fuel and another $150 a year for repairs, not counting the damage to the crop while the pump is waiting to be repaired.

What if the same farmers could use electric pumps, powered by solar photovoltaic panels, and drip irrigation to water 1 ha (2.5 acres) of vegetables? The fuel costs and operating costs would be pretty close to zero, but there’s a big catch. Currently, a solar PV-powered drip irrigation system of that size would cost about $10,000! The small farmers in Asia and Africa could never afford to buy one.

Who we are and what we do

We are a team of professionals dedicated to improving the income of the rural poor. We subscribe to zero-based design coupled with the relentless pursuit of affordability and a market-driven approach to accomplishing this. This development approach is outlined in a book that has just been released: The Business Solution to Poverty by Paul Polak and Mal Warwick. The basic premise of zero-based design is to begin from scratch and focus on searching out the most cost-effective solution for each component of the complete system.

Using the zero-based design approach, we decided that we could find a way to cut the retail cost of a solar-powered drip irrigation system to $4,000 for 1 ha (2.5 acres) of diversified off-season fruits, vegetables, and spices. That way, smallholder farmers could have food security for their families and clear at least $4,500, enough to make payments on a three-year loan or lease and put some real money in their pockets. By finding a way to achieve breakthrough affordability for PV-powered pumping and efficient irrigation, smallholder farmers all over the world could move out of poverty. At the same time, they could provide jobs for their neighbors in planting, weeding, harvesting, and marketing the crops they grow.

India, for example

Today, in India alone, 19 million diesel engines are being used to pump irrigation water from shallow wells, spewing millions of tons of carbon into the atmosphere. If market forces could replace a quarter of them with radically affordable solar PV-powered pump systems and drip or mini-sprinkle irrigation, we could transform smallholder farmer livelihoods and radically reduce rural carbon emissions.

Today, in India alone, 19 million diesel engines are being used to pump irrigation water from shallow wells, spewing millions of tons of carbon into the atmosphere. If market forces could replace a quarter of them with radically affordable solar PV-powered pump systems and drip or mini-sprinkle irrigation, we could transform smallholder farmer livelihoods and radically reduce rural carbon emissions.

Presently, we are in the process of developing cost-effective PV-based, low-pressure irrigation systems and establishing a commercial enterprise to promote their adoption by farmers in India and other Asian counties. Minimizing the energy requirements is essential for building a cost-effective PV-powered pumping system to irrigate crops. We are accomplishing this by applying a systems approach to optimize the energy and water flow components from the water supply to the irrigated crops. These components include the PV array, with or without mirror concentrators and tracking; the DC or AC motor and pump mechanism; the well filter and screen, which are designed to reduce drawdown to optimize water output from the solar input; and low-pressure water conveyance and application systems to optimize crop production per unit of irrigation applied. A small-plot drip irrigation system like the one pictured in the photo above in Nepal would be ideal.

What does this involve?

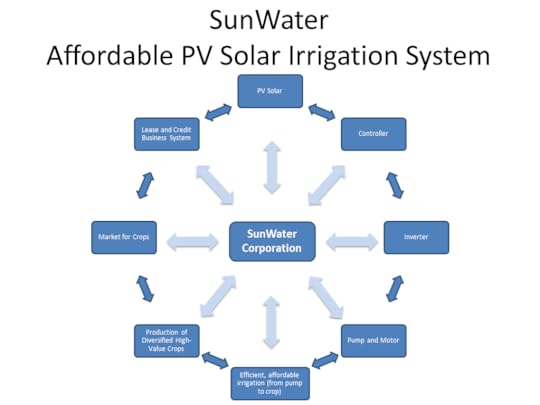

To pull it off, we need to work on solar power, pumping, water supply, irrigation, and livelihood-enhancing high-value crop production and marketing as a total system, with each component of the system influencing the design of every other component. The diagram below shows what this interactive system looks like.

While working with International Development Enterprises, an NGO located in Denver, Colo., we succeeded in reducing the market price of drip irrigation by employing very low operating pressures. This allows the use of recycled plastic tubing and simpler fittings and valves to break the irrigated area into subplots supplied by thin-walled lay-flat drip lines. We also employed wide flow path emitters, allowing the use of affordable filters to remove dirt from the water. With a water supply well at the field boundary, our 1 ha (2.5 acre) drip system will be designed to provide a net water application of up to 7 mm (0.28 in.) per day and requires an inlet pressure of only 39.2 kPa or 4.0 m of pressure head (5.7 psi) and an overall pump head requirement of only 9.0 m (29.5 ft) when combined with an assumed 5.0 m (16.4 ft) dynamic suction lift.

Despite the fact that the price of solar PV systems has dropped significantly over the past ten years, the capital cost of an installed PV system to pump irrigation water is still too high. But there are options for further lowering the capital cost. For example, a simple glass mirror is much cheaper than a solar panel. If we use mirrors to concentrate sunlight onto a solar panel, we can increase the generated power. Since we’re pumping water, we can pump a small amount of water through a simple heat exchanger on the back of the PV panel to keep the panel from overheating.

How to make ends meet

To afford a PV-powered

pumping system supplying a low-cost drip system, and make a reasonable livelihood at the same

time, smallholder farmers need to

irrigate in the dry season, when

vegetable prices are two or three

times as high as they are during the

rainy season, when everybody can

grow vegetables. Savvy farmers

plant four or five high-value crops

because it’s impossible to predict

what the market price for any one

crop will be, and diversified cropping lowers both plant disease

risks and market risks and increases the probability that at least one

of the crops will generate a lucrative profit. Field tests in a variety

of countries have demonstrated

that typical farmers can earn a net

income after expenses of $0.45 per

square meter, or $4500 from 1 ha (2.5 acre) of diversified high-value cash crops, such as off-season vegetables in local urban markets. So it’s just as important to help farmers optimize their income as it is to lower the cost of pumping and improve the efficiency of conveying and applying water from its source to the crop.

To afford a PV-powered

pumping system supplying a low-cost drip system, and make a reasonable livelihood at the same

time, smallholder farmers need to

irrigate in the dry season, when

vegetable prices are two or three

times as high as they are during the

rainy season, when everybody can

grow vegetables. Savvy farmers

plant four or five high-value crops

because it’s impossible to predict

what the market price for any one

crop will be, and diversified cropping lowers both plant disease

risks and market risks and increases the probability that at least one

of the crops will generate a lucrative profit. Field tests in a variety

of countries have demonstrated

that typical farmers can earn a net

income after expenses of $0.45 per

square meter, or $4500 from 1 ha (2.5 acre) of diversified high-value cash crops, such as off-season vegetables in local urban markets. So it’s just as important to help farmers optimize their income as it is to lower the cost of pumping and improve the efficiency of conveying and applying water from its source to the crop.

The best way to reach scale is to release market forces, creating opportunities for every participant in the market to earn a reasonable profit. This includes the manufacturers of both the PV-powered pumping systems and the irrigation systems, the dealers who sell them, the technicians who install them, and the farmers who buy them to improve their livelihoods.

Taking the first step

Taking the first stepThe first barrier to profitability is the capital cost of $4,000 for the total system. Even though it can earn attractive returns on investment, the upfront cost is too high for most smallholder farmers. For this reason, an important player in the system needs to be a business that offers solar PV-powered pumping and irrigation systems on a lease basis or on credit, with the lease/credit business also earning an attractive profit.

To energize this project and ultimately the market, a holding company called Paul Polak Enterprises has been formed. This company is partnering with volunteer engineers from Ball Aerospace, called the Design Revelation Employee Resource Group, headed by Paul Storaci. Ball Aerospace is providing workshop facilities, and staff engineers and technicians are donating their time and talents as a contribution to this initiative. These guys are good: Ball Aerospace built the instruments on the Hubble Space Telescope. Now they are charged with building the proof-of-concept prototype of the low-cost solar PV-powered pumping system.

Meanwhile, two of this feature’s co-authors—Jack Keller and Robert Yoder, world authorities on small-plot irrigation and development—are working on the design and beta testing of the total system, and the pilot commercial rollout in Gujarat, India. In India, we will be working with an Indian subsidiary of Paul Polak Enterprises that will play the local leadership role. From Gujarat, SunWater India will initiate a full-scale rollout of the affordable solar PV-powered pumping and irrigation system in India’s eastern states, where the majority of India’s 19 million diesel pumps are located. After we create a new market for solar PV-powered irrigation in India, our dream is to take it to other countries in Asia and throughout the world.

Each dream starts with a first step, and our first step was to raise $32,000 in an Indiegogo (crowd funding) campaign to fund the completion of the proof-of-concept prototype by the volunteer engineers at Ball Aerospace. That goal has been met. Stay tuned for the rest of the story.

This article originally appeared in the November/December 2013 issue of Resource: Engineering and Technology for a Sustainable World, Vol. 20, No. 6, published by the American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers (ASABE) and copyright © 2013 by ASABE.

Jack Keller, P.E., is Professor Emeritus, Department of Civil Engineering Department, Utah State University, and founder of Keller-Bliesner Engineering, LLC, Logan, Colo., USA. Paul Polak is CEO, Paul Polak Enterprises, Denver, Colo., USA. Paul Storaci is Director of Electronics and Software Technologies, Ball Aerospace, Boulder, Colo., USA. Robert Yoder is CEO, Yoder Consulting, Denver, USA.

December 3, 2013

Clean Water for India

Spring Health village demonstration

By Paul Polak

Spring Health, our rapidly scalable safe drinking water company designed to go global, has now started its commercial rollout in India by recruiting and training 90 new full-time staff, and expanding from 35 villages to 105 villages in three months.

As the months go by, we have learned more and more about the fundamental importance of getting the marketing mix right. We’ve bundled all the most successful tactics into an approach we call “blitz marketing.”

Blitz marketing

We have improved our blitz marketing strategy to the point that we now can increase sales in village partner shops to 1000 liters of water a day within two months of opening — a level at which the company begins to turn a profit. In fact, in one village sales increased from 500 liters a day to 2500 liters a day after only three days of marketing.

We now apply four blitz marketing techniques simultaneously:

The first is a kiosk opening ceremony with entertainment, and the second is a play performed twice in each village by a professional theatre group.

The third is festive door-to-door sales by 10-member teams, creating quite a buzz when accompanied by an auto rickshaw with speakers playing music and providing information about water and health.

Finally, we carry out e coli tests on samples of the water people actually drink. There seems to be nothing more motivating than when families see ugly colonies of bacteria growing out of the water their families are drinking.

At the end of the marketing blitz, the 100-person marketing blitz team hands over the block of 50 villages to a permanent operations team of three to four full-time members, and moves on to the next 50-village block.

Our village operations include a three-member specialty team that screens villages, consults village elders to identify the best shopkeepers, and signs an agreement with the selected shop partner. Then a four-member build team hires local artisans to build the water tank and connect pipes and electricity to each shop. These two teams recruit and build 50 village systems in one month.

Young Spring Health customers

The total cost of conducting the marketing blitz is about $330 per village. Adding net capital equipment investment costs of $200 brings the company’s initial investment in capital expenditures (CAPEX) and marketing to approximately $530. Gross income to the company from each village kiosk is approximately $1,350 per year. Assuming 50% in operating expenses, this leaves about $675, sufficient to cover initial CAPEX and marketing costs within one year.

Last-mile distribution

One of the most exciting things about the operating system we have developed is that it represents a last-mile distribution system to people in small villages that is actually profitable. Each staff member visiting a village carries only 10 kilos of water purifier by motorcycle each day to six villages, leaving some 80 kilos of unutilized cargo space for a whole range of other transformative products for which the last-mile transport costs are close to zero. Within three years, we expect to be in a position to provide last-mile distribution of a whole range of aspirationally branded products to 30,000 village shops while making a healthy profit operating purely as a commercial business without subsidy. Within three years we will deliver safe drinking water in 10,000 villages, and within ten years we plan to deliver safe drinking water to 100 million $2-a-day customers.

For more about Spring Health India, check out this excellent, in-depth Indian TV update featuring an interview with my Indian partner, Jacob Mathew:

http://chaiwithlakshmi.in/2013/seasons/season4/good-water-for-india.html

November 26, 2013

The Last 500 Feet

Carrying fodder home

By Paul Polak

Developing practical and profitable new ways to cross the last 500 feet to the remote rural places where poor families now live and work is the first step towards creating vibrant new markets that serve poor customers.

In rural Orissa, India, the women are not permitted to walk more than 150 feet from their homes to fetch water. So how can they transport water to their homes from the closest safe water source, located 300 feet away?

Fortunately, it’s not that difficult to transport 100 kitchen drip kits from Kathmandu to Pokhara on the roof of a bus. The challenge is in getting those kitchen drip kits to the hundred scattered farms in hill villages that are a day’s walk from the nearest road!

From anything including drip irrigation kits, oral rehydration salts, penicillin, and disaster relief food, moving goods and services over the last 500 feet is especially difficult. And the reverse is equally daunting. Moving marketable goods produced by the hands of poor people in remote villages to the town and city markets where they will fetch the best prices is just as difficult.

Moving goods and services across the last 500 feet of the last mile in and out of scattered rural villages is a challenge crying out for practical solutions.

The last mile

I was surprised to learn that the “last mile” concept comes from the telecommunications industry, which has learned that it’s much cheaper to lay a fat cable carrying television and phone signals almost all of the way to the end customer rather than it is to split it up into a multitude of smaller wires that extend directly to individual homes. As it turns out, wireless communication has helped the telecommunications industry address the last mile challenge, but the movement to end rural poverty has found few solutions to the even bigger challenge of crossing the last 500 feet.

Several organizations have developed models that train villagers to market key goods and services to their neighbors. Following are some examples of this approach.

Living Goods village saleslady at work

Living Goods

Following the Avon lady model, Chuck Slaughter founded Living Goods, which trains women in Uganda to sell three or four basic medicines to treat poverty-related illnesses such as malaria, diarrhea, worms, and tuberculosis. “We retail a child’s dose of malaria medicine for 75 cents,” Slaughter says. According to Fast Company, Living Goods has trained more than 600 women in Uganda, and some of them are making more than $100 a week (Fast Company Article). Hiring and training villagers to go door to door to sell important products is a rapidly growing strategy for covering the last 500 feet.

BRAC

BRAC (originally, the Bangladesh Rehabilitation Assistance Committee) is the world’s largest nonprofit development organization, with more than 100,000 employees and programs that directly benefit more than 100,000,000 people. In Uganda, BRAC has mobilized 1,880 village women to act as community health volunteers who distribute products such as oral rehydration salts, iodized salts, and antibiotics for a small fee to villagers (BRAC article).

Green Light Planet

Green Light Planet is a for-profit company in India, which recruits village entrepreneurs to sell $18 solar lanterns to replace kerosene lamps in villages (“Lighting a billion lives”).

Mom-and-pop stores

Another promising and widely available way to move goods and services across the last 500 feet is to take advantage of the staggering numbers of village mom-and-pop shops that already sell consumer items in every developing country.

According to the most recently available data, there are 638,000 villages in India (where, not so incidentally, some 72 percent of the population still lives). Since each of these villages has two or three small shops and the bigger villages have more than five, it’s reasonable to assume that there are more than two million small rural village shops in India. But as far as I know, nobody has ever counted them. My guess is that there are at least 10 million small shops in small rural villages in developing countries all over the world. There are also small vegetable carts, milk carts, and other kinds of peddlers’ carts bringing goods and services directly to rural homes. Many of these shops are 10 x 10-foot cubicles, with shutters that swing open when the shop opens and can be padlocked when it’s closed. These shops sell items such as cookies, candies, soap, cigarettes, spices, bulk cooking oil, bananas, small flashlights, and a variety of other small consumer goods, sometimes including chilled soda pop.

Since they are already patronized by most poor rural customers in small villages, and can have easy access to bicycle home delivery and pick-up, these small shops are a priceless resource already in place and capable of carrying goods and services across the last 500 feet. But only a tiny percentage of their potential is being utilized.

Since these small shops are within 500 feet of many of the world’s poor customers, village shops could also provide natural collection and aggregation points for goods produced by the hands of villagers. Because daily sales volume at each shop is low, and the shops are widely scattered, most commercial attempts so far to distribute to small shops have failed to be profitable.

Ten million small shops in villages all over the world are waiting for viable business models for distributing a cornucopia of branded, income-generating products and tools for poor customers, and collecting income-generating goods produced by villagers and transporting them to markets in cities and towns where they can be sold profitably.

Recruiting village shops like this can solve the riddle of the last 500 feet

November 22, 2013

Business Can Feed the Hungry

By Amy Alexander for Investors Business Daily

By Amy Alexander for Investors Business DailyAt Thanksgiving, Americans are challenged: Feed the hungry. Clothe the poor. The best way to do it? Capitalism, say Paul Polak and Mal Warwick, authors of “The Business Solution to Poverty.”

“The endless possibilities that can come out of bringing more people into the market economy promise a brighter future for us all,” Warwick told IBD.

Safe drinking water for India

In Orissa, a state in India, clean drinking water was once a luxury. Larger cities have giant purification systems, but bringing them to remote villages is expensive. Orissa’s locals, who make $2 a day, traditionally sipped and cooked from the same spot where they bathed. This made them sick.

The typical response: pity and charitable donations. Polak, a Golden, Colo., psychiatrist-turned-entrepreneur, saw another way.

Sensing a burgeoning marketplace, he had his Windhorse International, a for-profit outfit that seeds businesses in developing countries, launch Spring Health Water in 2011. Now it partners with locals in Orissa who operate water treatment tanks on behalf of Spring Health.

The water sells for pennies, but demand is high and margins low, so those coins add up. This year’s projected earnings: $284,000.

Spring Health hopes to double its income annually over the next five years, which could add up to millions in sales. Already, residents of Orissa are healthier and happier.

Spring Health employs local delivery drivers, inspectors and managers. The shops that sell the water at a 25% commission are seeing a spike in sales of other goods and are smiling about it.

Goal: To provide safe drinking water to more than 100 million people through shops in 400,000 villages around the world in 10 years.

Warwick and Polak offer these hints for uncovering business chances in impoverished corners:

Rethink markets

“Don’t look at poor people as alms seekers or bystanders to their own lives,” Polak and Warwick wrote. “They’re your customers. Always set out by purposefully listening to understand thoroughly their lives — their needs, their wants, their fears, their aspirations.”

• Get it out. Decentralize operations. Sometimes the last 500 feet of distribution keep businesses from moving products into rural areas.

• Make money fast. Remember, your goal is to fatten your firm so it can continue to grow into new markets. Make sure your margins let people at even the humblest level of the enterprise get a nice cut. Said Warwick: “Design for scale, and design for generous profit from the word go.”

October 21, 2013

End Poverty or Bust

Paul Polak speaks about commercialization and scale at Cornell University

Creating a Runway for Profitable New Multinational Businesses to Transform Poverty

By Paul Polak

Five years ago, Steve Bachar and I decided to create a venture capital fund that would only invest in companies capable of achieving three goals:

Transforming the livelihoods of at least 100 million customers living on $2 a day or less;

Generating at least $10 billion in annual revenues; and

Earning sufficient profits to attract commercial financial investment.

There was only one problem.

We couldn’t find any companies to invest in that met these criteria. Among social entrepreneurs, design for scale is as rare as hen’s teeth.

So my partners and I decided to launch such businesses on our own to prove the feasibility and set a course for ending poverty on a truly big scale. Five years later, we’ve created four new companies. The one that’s furthest along sells safe drinking water to $2-a-day rural customers in eastern India at a home-delivered price of 8 cents per day for a ten-liter jerry can. Eight cents a day, or $2.40 per month, is significantly less than what families now pay to treat the illnesses they get from drinking bad water. This company is fast approaching the tipping point of achieving both profitability and scale, and three other companies, addressing energy, education, and smallholder prosperity, are at various stages of early development.

Better still, Mal Warwick and I have just published a book called The Business Solution to Poverty: Designing Products and Services for Three Billion New Customers, which describes in some detail how to create such businesses. We hope to jumpstart a new generation of multinational companies capable of earning attractive profits while transforming the lives of 100 million poor customers at a time. We call the method we’re using zero-based design, a comprehensive approach to designing a business venture from scratch, starting with zero assumptions or templates, learning what customers need and want, and designing radically affordable technologies and services to solve customers’ problems and the last-mile distribution strategies to make them available at scale.

Creating the Runway

With 2.7 billion people now living on $2 a day or less, any effort that truly hopes to achieve a material reduction in global poverty must be conceived to reach enormous scale. In my opinion, each business must set a goal of transforming the lives of at least 100 million poor people. To stimulate the creation of startup companies capable of reaching that scale, a reasonable starting point is to identify markets with a minimum of one billion prospective customers. If you assume that a 10% market share would be a reasonable goal, then gaining a customer base of 100 million over the course of a decade should be attainable for a successful multinational enterprise. But the existence of many markets with one billion or more $2-a-day customers is already well documented. There are one billion $2-a-day customers with no access to electricity, another billion without access to clean drinking water, a billion without access to decent affordable health care, a billion needing affordable education, and another billion without access to sanitation. A small, world-class executive team could fairly quickly identify a hundred opportunities to create transformative new markets serving poor customers and pick gifted entrepreneurs who could form scalable startup companies to take advantage of them.

A $30 Million Fund to Create the Runway

What I propose is to form a $30 million “runway fund” to jump-start the process. After identifying 100 startup companies and lead entrepreneurs capable of transforming the livelihoods of 100 million poor customers, generating $10 billion in annual revenues, and earning profits attractive to commercial investors are identified, the fund would operate on the basis of three phases:

Phase 1: Proof-of-concept prototype of the technology and key elements of the business strategy for six months, with each startup receiving $75,000 in funding

Phase 2: Beta test of the technology and business strategy with potential customers for six to twelve months, with each startup company that successfully passes Phase 1 receiving $150,000

Phase 3: First-stage commercial rollout for three years with total funding of $1.5 million for those ventures that succeed in Phase 2.

I would estimate the fund’s budget at $30 million as follows:

100 startup businesses, proof of concept phase $7.5 million

30 businesses pass successfully to beta test phase $4.5 million

10 businesses go to commercial rollout $15.0 million

Executive team $500,000 x 4 $2.0 million

Total $29.0 million

With 10 businesses in commercial rollout, we would launch a second investment fund of $100 million to finance their global expansion.

Investment Fund to Achieve Global Scale

A reasonable budget for the expansion fund would look something like this:

Three companies @ $25 million each $75 million

Two companies @ $12.5 million each $25 million

Total $100 million

If five successful enterprises then each succeed in reaching 100 million customers, helping them to transform their lives, a total investment of just $130 million – a tiny fraction of the $2.5 trillion the rich countries have invested in traditional anti-poverty efforts – would result in 500 million people living on $2 a day or less to make their way into the middle class. That’s an investment of just 26 cents per person! If our projections are realistic, that could easily represent the best investment ever in its social impact.

Paul Polak's Blog

- Paul Polak's profile

- 8 followers