Randal Rauser's Blog, page 134

December 17, 2016

An Atheist and a Christian Walk into a Podcast

Justin Schieber and I were recently interviewed on the storied Storymen Podcast hosted by the culturally savvy trinity of geek-cool, JR Forasteros, Clay Morgan and Matt Mikalatos. I’ve been on the podcast before and I always enjoy the exchanges. This was no exception.

You can listen to the interview here.

The post An Atheist and a Christian Walk into a Podcast appeared first on Randal Rauser.

December 15, 2016

Milestones without God: An interview with Secular Celebrant Galen Broaddus

Recently I learned that CFI (Center for Inquiry) runs a program certifying secular celebrants, individuals who can serve as officiants for ceremonies marking milestones in life without any of the trappings of religion or belief in God. Once I learned about this, I decided I wanted to hear more. So I invited Galen Broaddus, atheist blogger at “Across Rivers Wide” and a secular celebrant for CFI for an interview. Our exchange is recorded below.

* * *

Galen Broaddus, Secular Celebrant

Randal: Galen, thanks for agreeing to do this interview to discuss the work of a secular celebrant. But before we get there, I’d like to begin with your religious background. As I understand it, you were raised a Baptist. So why did you leave the church?

Galen: Like most of my stories, that’s a long one, but I’ll try to give the abridged version.

I was in fact raised Baptist; my father was an active minister most of my childhood, mostly in Southern Baptist churches in rural Illinois. My upbringing wasn’t particularly fundamentalist, but it was certainly conservative. I was also a fairly precocious child, and to their credit, my parents encouraged my curiosity and hunger for knowledge.

That curiosity came to fruition for me after I briefly attended a Christian college, where I was introduced in a more formal way to Christian philosophy and theology. Even though I left that college (for reasons unrelated to the education or institution itself), I was hooked, and I voraciously read whatever works of Christian apologetics and philosophy I could get my hands on. At one point, I even purchased the textbook Philosophical Foundations for a Christian Worldview by William Lane Craig and J.P. Moreland and read it cover to cover.

Meanwhile, I wasn’t content just to consume this material; I wanted to test it. So I went to the Internet and intentionally sought out places where I could debate with non-Christians, often with atheists. I didn’t know any atheists in real life (that I was aware of), so this was often an illuminating experience for me, as I encountered atheists who were both more knowledgeable and more adept at pointing out the flaws in my arguments. Many of them also challenged my preconception of atheists as angry, bitter, and depraved.

Eventually, I began to find that I didn’t have a solid ground on which to base the faith of my childhood (or indeed any faith, as far as I could see), and that led to a moment almost five years ago where I realized I didn’t believe in any gods — certainly not in the deity of Christianity.

It hasn’t always been easy since then, especially given that I’m (quite happily!) married to a Christian, but here I am.

Randal: Interesting. I always find conversion and deconversion stories fascinating, so maybe I can press you a bit on a couple points. First, was there some particular issue that you can recall as the tipping point toward atheism? Or was it just the gradual accumulation of smaller issues?

And did you move directly from Christianity to atheism in one big step? Or did you pass through various versions of Christianity and minimal theism before becoming an atheist?

Galen: There’s a line from the book The Fault in Our Stars by John Green that I always think of in this context: “I fell in love the way you fall asleep: slowly, and then all at once.” That’s sort of how I fell out of love with religion and with theism in general.

I probably started delving into my own personal studies in 2005, and it started out with issues almost tangential to theism or Christianity, most specifically evolution. I wasn’t ever really a full-blown young-earther, but I had grown up with a learned disdain for evolution, so actually learning about evolutionary theory — because I needed to know it better to debunk it, I thought — helped me understand what I didn’t know. There were a number of issues where that was true, from creationism to biblical inerrantism and so on.

It’s difficult for me to say if I moved through any stages because to me the change was almost imperceptible to me. If you had asked me literally the day before my own personal “epiphany,” I’d have told you I was a Christian. I wasn’t an evangelical, and I held a number of heterodox positions — for instance, the last conscious change of belief I can remember was a rejection of the traditionalist view of hell and an acceptance of universalism — but I still thought of myself as a Christian, generically, and I definitely identified as a theist.

Truthfully, I think I had mentally conceded the battle somewhat before that, but my emotions needed to catch up and (to use Jonathan Haidt’s metaphor) allow the elephant to move where my rider was already steering. After that, I was able (if I might switch metaphors mid-stream) to achieve escape velocity.

Randal: That’s really helpful Galen. Thanks for the quick overview. I have no doubt that we could spend hours hashing some of those topics out. I always find personal narratives fascinating, and it sounds like yours is no exception!

Having said that, I’d like to turn to a somewhat different topic at this point, namely your status as a secular celebrant. I was really intrigued when I discovered that you had this role. So I’d be interested if you could first explain what a secular celebrant is, how it might differ from a justice of the peace (if it does), and why an organization like the Center for Inquiry is involved with secular celebrants in the first place.

Galen officiating at a wedding

Galen: Let me clarify a few definitions right off the bat. A celebrant is, in general terms, someone who facilitates the various ceremonial aspects of life events, most notably marriages and funerals/memorials. (There are others, like coming of age and welcoming ceremonies, but they tend to be less in demand outside religious communities.) A secular celebrant simply differs from the religious celebrants most people are used to (clergy or lay leaders) in that she isn’t coming from a religious tradition.

That’s the general sense of the term. I happen to be a secular celebrant working under the auspices of a secular organization (the Center for Inquiry); you can find others who are authorized through explicitly religious organizations or organizations that have a religious charter of some kind, like the Humanist Society here in the US. This is a point I frequently have to explain because of the odd quirks of our state marriage laws.

Secular celebrants differ from a justice of the peace primarily in the fact that, like most religious celebrants, we’re not agents of the government in any fashion. (We actually don’t have JPs here in Illinois.) I’m just a private citizen providing a service to individuals and couples who might be non-religious or might be personally religious but don’t want to involve religion in their life events for whatever reason.

CFI’s involvement is a bit trickier for me to speak for, but the organization is really strongly behind the idea of humanist values, including finding rich meaning in a naturalistic worldview. CFI fosters secular communities through a number of branches and affiliate groups across the US and in several other countries, so there’s a need within those circles to train individuals who can perform that function within these communities.

CFI’s involvement is a bit trickier for me to speak for, but the organization is really strongly behind the idea of humanist values, including finding rich meaning in a naturalistic worldview. CFI fosters secular communities through a number of branches and affiliate groups across the US and in several other countries, so there’s a need within those circles to train individuals who can perform that function within these communities.

There’s also a church-state issue because all 50 states (and the District of Columbia) permit religious officiants to solemnize marriages so that they carry the legal authority of the state, but relatively few allow secular celebrants to do so. (Secular celebrants authorized by a religious organization can also solemnize marriages by virtue of that authorization, which is why I’ll occasionally have people tell me — wrongly — that secular celebrants can solemnize marriages in the US.) Remedying that inequity has been right in line with CFI’s strong secularist position, and they won a federal court case in 2014 that opened up this right to secular celebrants in Indiana. For about two years, I’ve been deeply involved in CFI’s efforts trying to do the same here in Illinois.

Randal: Very helpful overview, thanks!

You described CFI’s commitment to fostering secular communities with “humanist values” and a “naturalistic worldview.” And the secular celebrant has a role in this mission by memorializing major life events. With that in mind, somebody might say, “This all sounds rather like the hallmarks of that which we traditionally call religion. And there are non-theistic religious communities, like some forms of Buddhism, for example. So should we think of the work of CFI and yourself as, in some sense, religious?

Galen: I wouldn’t go that far. But I will say this: My whole perspective on this is that secular humanism is at its core an ethical system; it does sometimes take positions on metaphysics and such, but it is an ethos based on Enlightenment values. Ethical systems are about how we live and derive meaning, and so it makes sense that secular humanism would sometimes concern itself with doing so in more collective ways.

However, that’s not necessarily a universal position; there are plenty of secular humanists who think that the role of a secular celebrant is best left in any required legal sense to a JP or judge or what-have-you and that any desire for ritual or ceremony is the baby that should be discarded with the rest of the religious bathwater. That’s fine with me, too. There’s no ethical imperative to engage in these activities, in my opinion, although I do my celebrant work with the belief that it’s better for there to be a means for secular celebrations to be available to those who want them.

I do concede that a lot of this is simply a dispute over definitions, and we could argue all day about the precise meaning of “religion” in this context. However, I think that both community building and celebrations of life can be clearly seen in non-religious contexts, so it would be fair to consider secular humanism to be non-religious even when it incorporates these aspects (which it doesn’t always).

(And, of course, as should hopefully be apparent, I’m speaking only for myself as a secular humanist, not for CFI.)

Randal: I do agree that much depends on one’s definition of religion. Typically when we are trying to discern whether an x should be identified as a y, we focus on whether x exhibits a set of precise necessary and sufficient conditions to be deemed a y.

But as Ludwig Wittgenstein pointed out, in many other cases we classify entities not by necessary and sufficient conditions but by overlapping similarities. Wittgenstein referred to this as family resemblance and he gives the example of a game. There is arguably no set of necessary and sufficient conditions by which we deem soccer, solitaire, and Sorry (the board game!) to be games. Rather, we group them all into the category “game” because of overlapping similarities.

Given the extraordinary diversity of communities and practices that are deemed religious, it seems likely that religion, like game, is a family resemblance concept. And among those resemblances are shared sets of metaphysical and/or ethical beliefs as well as ritualized practices that create community solidarity and mark major life events.

Do you find it plausible to think of “religion” as a family resemblance concept? And if so, do you think it plausible that secular communities could be deemed religious if they adhere to a set of shared metaphysical and/or ethical beliefs and they ritualize major life events, often by way of a class of designated representatives?

Galen: I don’t disagree with the notion of religion as family resemblance, per se, but there are a few issues that I do have with that analysis here.

First, imposing the notion of religion upon systems which reject (either explicitly or implicitly) religion as a moral or ethical authority puts us in the territory of affirming contradictions. Indeed, you even talked of whether “secular communities could be deemed religious”! We might thus talk of how Mr. Jones is in fact a married bachelor because he cohabitates with a partner and shares financial responsibility, family duties, and so on. Either we are faced with an absurdity, or our calculus is off.

Second, I think the key question for me is less whether religion can be defined (in this general family resemblance sort of way) to include secular humanism but whether religion is itself a subset of a broader and/or overlapping category (what is sometimes referred to as a lifestance). Consider that of the major humanist organizations in the world, you can find both secular charities and non-profits like American Atheists, the British Humanist Association, and CFI, as well as religious organizations like the American Ethical Union and the UU Humanist Association. I don’t think this is an accident.

But I will say this: If we are to speak about secular humanism as religion for a limited purpose, in the way that atheism and secular humanism are often considered religions for the purpose of protecting religious expression (as is the case with First Amendment jurisprudence here in the US), then I think I can personally concede that point. I just don’t think it’s the operative sense of that term as it is widely used, and as such, that’s where I resist the framing of secular humanism as a religion in general.

In the same vein, I’ve had people deride the idea of secular celebrants as “secular ministers,” and I don’t resist that in the sense that I perform a function that is often done by clergy. But I hold no organizational or particular moral authority; I possess no titles; I absolve no sins. The differences are relevant, regardless of the similarities, and that’s true of secular humanism as a belief system as well.

Randal: Traditional clergy typically go to seminary and are ordained as preparation for fulfilling their ministerial functions. But how does a secular celebrant attain their certification to perform their duties? Is formal training required or do you learn through informal mentorships, or…?

Galen: This again varies depending on who you work with. CFI does require training for its celebrants, which is typically a full-day session going through the various aspects of a celebrant’s responsibilities (including our legal responsibility, for those working in states where we are permitted to solemnize marriages). To my knowledge, that isn’t the norm; a secular celebrant who obtains an ordination from (for instance) the Universal Life Church probably won’t go through any training beyond some basic information supplied by the ULC at the time of ordination. I’m also not aware of any such requirement for the Humanist Society’s celebrants, although I do think the organization has offered celebrant workshops in the past.

My guess, since I can only speak for my experience, is that many secular celebrants do have training: religious training. I know several such people who were clergy or involved in ministry in the past and became secular or humanist celebrants in order to put that training to use after leaving religion. Obviously, there’s no liturgy to pull from and there’s a different worldview informing the practice, but the skillset does actually transfer pretty decently.

Image Credit: http://www.johnpiippo.com/2010/05/ber...

Randal: That makes sense. And presumably it’s not just the skills and practical experience they bring from religion, but also an appreciation for the importance of pastoral ministry, ritual, and liturgical form.

This has been an illuminating exchange Galen, and I thank you for your willingness to explain the role of the secular celebrant. As we wrap up, I’d like to end on a question that brings practice and theory together by getting your thoughts on one of your duties: conducting a funeral.

In a Christian funeral based on orthodox theology, the minister appeals to thankfulness for the gift of this person’s life, comfort that the person no longer suffers and thus is now in a better place, and hope that the person shall be resurrected in the future and reunited with loved ones again in the new heaven and earth.

I get that you believe this thankfulness (to God), comfort (in the peace of the interim state), and hope (in the resurrection) is misplaced. Needless to say, the defense of those attitudes is another question for another day. But what I want to know is how do you handle the funeral as a secular celebrant? How do you present thankfulness? How do you extend comfort? Can you offer hope?

In an oft-quoted passage from his essay “A Free Man’s Worship,” atheist Bertrand Russell eloquently summarizes his distressingly bleak picture of reality in an atheistic universe. He then concludes, “only on the firm foundation of unyielding despair, can the soul’s habitation henceforth be safely built.” In today’s parlance: suck it up, buttercup.

What do you think?

Galen: First, let me say that this isn’t a new question to me; when I was first going through certification a few years ago, my believing mother outright asked me how I could possibly bring hope to the grieving. It’s not an easy question to answer because the subject of our human mortality is visceral, so it’s sometimes difficult to find a truly satisfactory answer (even with religion, in my opinion). I take that responsibility very seriously, as I think many religious celebrants do as well.

Second, I don’t actually agree with Russell entirely on the general point. Death is certainly a heavy subject, but I don’t think it has to be bleak for someone who doesn’t believe that one’s immaterial self survives physical death. (Indeed, Russell himself also spoke a bit more optimistically about how to grow old.)

To your points: You’ve framed funerals and memorials in terms of thankfulness, comfort, and hope. I don’t think there are necessarily the focuses of a secular memorial, but there are ways in which they still apply.

I often refer to these services as “celebrations of life,” and I don’t mean that euphemistically. Those who grieve come to honor the memory of the deceased, and without the shadow of a hereafter, that is what matters. I’ve been to funeral services where memorializing wasn’t emphasized, and it felt incredibly empty. It’s the care of others and the human connections that were made in life that make a memorial more than just a mere recognition that a life has ended.

In a sense, memorials are a way of reminding ourselves that, at base, we do have each other. We remember and we are grateful for each having had the opportunity to know the deceased. We share collectively in our memories and are comforted by our solidarity in grief. We hold the hope that our own lives can be indeed meaningful to others, as we recognize the meaning brought to us by the deceased.

Not all of these will be felt in that moment; grief is too complex for such a simple solution, religion or no. In the moment, remembering is about focusing that pain in a way that allows it to be felt, not alone but collectively.

In that respect, my job is first and foremost to allow that space for the deceased’s loved ones to share in each other’s memories and pain. The second is to work to honor the deceased’s wishes (including their beliefs) as much as possible in the service. To do so, I will generally include readings or reflections that emphasize our shared humanity (or sometimes our connection to nature) and the legacy we can still leave behind. Other circumstances may require a more delicate touch still.

Like so much in life, it’s messy and difficult to navigate. I’d rather try and do some of the heavy lifting for that so that the grieving can just focus on their grief. If I can do what I can to take some of that burden off them, I consider that one of the best services I can provide.

The post Milestones without God: An interview with Secular Celebrant Galen Broaddus appeared first on Randal Rauser.

Top 30 Atheist Blogs (according to Feedspot)

This week website Feedspot included my blog on a list of the top 30 atheist blogs and websites every atheist must follow. (I came in at number 14.) Feedspot founder Anuj Agarwal invited me to display the medal depicted to your right on my website. I have thus far demurred (with the exception of this blogpost) given that I don’t have an atheist blog, so the virtual medal is seriously misleading.

This week website Feedspot included my blog on a list of the top 30 atheist blogs and websites every atheist must follow. (I came in at number 14.) Feedspot founder Anuj Agarwal invited me to display the medal depicted to your right on my website. I have thus far demurred (with the exception of this blogpost) given that I don’t have an atheist blog, so the virtual medal is seriously misleading.

That said, I am fine with the general recognition. While I don’t have an atheist blog, I do have a website that I think atheists would benefit from following.

I’m not sure how this list was drawn up, but I’d like to think my inclusion in the list indicates some fruit of long labors in irenic dialogue (more or less) and steelmanning the views of my atheist interlocutors.

There are some websites/blogs included in the list that I would not think deserve to be included in the top 30. There are others that I think should be on this list including (but not limited to) Secular Outpost and Godless in Dixie. In other words, like most “Best of” lists (e.g. “Best Japanese Horror Movies”; “Top Ten Sushi Restaurants in Los Angeles”) this curated list is open to endless criticism and nitpicking.

Nonetheless, to criticize and to nitpick is to miss the point. The list certainly offers a fine launching point for further exploration and that’s all one can really ask.

Any additional suggestions on atheist blogs and websites/blogs that atheists (and the rest of us) should follow would be welcome in the comment section.

The post Top 30 Atheist Blogs (according to Feedspot) appeared first on Randal Rauser.

December 14, 2016

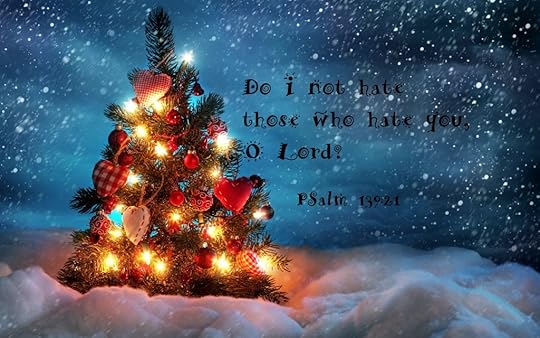

Sending Out Christmas Curses

Tired of the same old Christmas cards? According to the satirical Babylon Bee “news” site, this family unwittingly stumbled upon a brilliant alternative: imprecatory psalm cards. (Thanks to Samuel Choy for forwarding the Babylon Bee article to me.)

After some reflection I’ve decided that this is not such a bad idea. At least your greeting will be remembered. Here’s my first try:

The post Sending Out Christmas Curses appeared first on Randal Rauser.

December 13, 2016

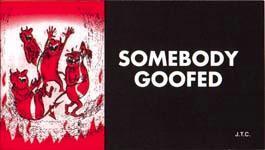

Somebody Goofed comes alive: Fundamentalism like you’ve never seen it before

Jack Chick, fundamentalist pamphleteer extraordinaire passed away a couple months ago. Looking back, there was an undeniable brilliance to the man. Indeed, some days I am inclined to place him in the same rarified air as Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. No matter that Chick thought he was fighting tirelessly to rescue souls from the yawning jaws of perdition, he unwittingly produced fundamentalist art along the way. His pamphlets brilliantly capture the existential neuoses of the Christian fundamentalist in their haunting pages. And none does it with quite the panache and drama as Somebody Goofed.

Jack Chick, fundamentalist pamphleteer extraordinaire passed away a couple months ago. Looking back, there was an undeniable brilliance to the man. Indeed, some days I am inclined to place him in the same rarified air as Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. No matter that Chick thought he was fighting tirelessly to rescue souls from the yawning jaws of perdition, he unwittingly produced fundamentalist art along the way. His pamphlets brilliantly capture the existential neuoses of the Christian fundamentalist in their haunting pages. And none does it with quite the panache and drama as Somebody Goofed.

So I was delighted to discover (through a recommendation from Dale Tuggy) that Somebody Goofed had been brought to life in this animated short. The film captures the tortured ethos of the tract with surprising verve and admirable sympathy. And perhaps best of all, it features an AMC Javelin as the final ride before eternal damnation. Though, in retrospect, I think a Dodge Demon might have been a better choice.

The post Somebody Goofed comes alive: Fundamentalism like you’ve never seen it before appeared first on Randal Rauser.

On Getting a Review Copy of An Atheist and a Christian Walk into a Bar

If you’re a blogger and you would like a review copy of An Atheist and a Christian Walk into a Bar, please let me know. (If you don’t have my contact information already, you can contact me at the bottom of this page.) I’d be happy to forward your request to Prometheus Books. Hard copies of the book are available for review within North America and Kindle versions are available outside North America.

The main stipulation is that you should commit to reviewing the book within the next two months. I learned this the hard way last year when I sent out more than 12 review copies of my book Is the Atheist My Neighbor? on request to various skeptic bloggers and I received only one review in return this past summer. (But it was an excellent, meaty review from Richard Carrier. And it also inspired me to write a friendly rebuttal.)

To sum up, this time out I’m requesting reviewers commit to writing a review within a couple months so we can get the word out on the book in a timely manner.

The post On Getting a Review Copy of An Atheist and a Christian Walk into a Bar appeared first on Randal Rauser.

December 12, 2016

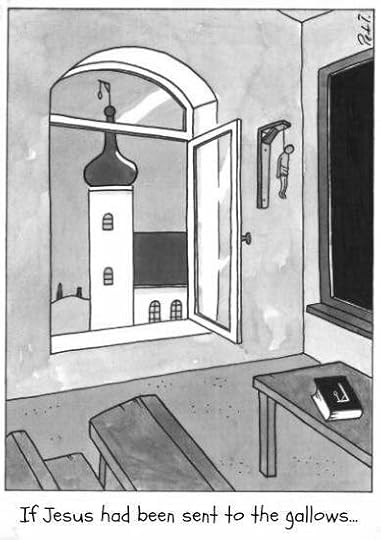

If Jesus had been sent to the gallows: On the felicitous outcome of attempted sacrilege

The other day a Twitter account called “Staunch Atheist” posted a cartoon which offered commentary on the Christian belief in crucifixion:

Within the context of this particular twitter feed, the posting was presumably intended to offer an irreverent and subversive critique of Christianity, one which might offend the sensibilities of Christians.

How ironic, then, that the effect is quite the opposite. Speaking as a Christian I’m happy to say that this cartoon isn’t irreverent at all. And the only subversion it offers is a laudatory take down of the cultural over-familiarity with the cross. Today the cross is a mere design motif, an item of jewelry. By contrast, the gallows still has the power to shock and offend. Consequently, by appealing to an intriguing counterfactual, this cartoon brings us right back to the scandal of the first century Christians.

In the ancient world there was no more shocking and shameful way to die. Indeed, the word excruciating derives from the meaning out of the cross. The cross was an utterly awful symbol, one sure to inspire horror and revulsion in any self-respecting Roman citizen. As Tom Wright puts it,

“if you had actually seen a crucifixion or two, as many in the Roman world would have, your sleep itself would have been invaded by nightmares as the memories came flooding back unbidden, memories of humans half alive and half dead, lingering on perhaps for days on end, covered in blood and flies, nibbled by rats, pecked at by crows, with weeping but helpless relatives still keeping watch, and with hostile or mocking crowds adding their insults to the terrible injuries.” (The Day the Revolution Began, 54)

As horrific as this was, the early Christians inexplicably came to love this terrifying symbol. Wright describes the transformative impact that the cross had on Christian identity with the example of the great Apologist, Justin Martyr:

“One of the great Christian writers of the mid-second century, Justin Martyr, wrote glowingly about the way in which the cross is the key to everything. It is the central feature of the world, he said: if you want to sail a ship, the mast will be in the shape of a cross; if you want to dig a ditch, your spade will need a cross-shaped handle. That gives us a fair indication of the way in which even those who were trying to explain the Christian faith attractively to outsiders, didn’t shy away from the cross, but rather celebrated it.” (21)

Needless to say, this elevation of the horrifying cross to a place of pious worship is one of the truly extraordinary developments in ancient history. And from the historian’s perspective, it requires an adequate cause to explain the dumbfounding transformation in attitudes toward this horror.

And of course, this remained a source of incredulity to non-Christians. As a case in point, virtually every work of early Christian history will include a picture of the famous “Alexamenos Graffito,” an item of third century graffiti from Rome which depicts a crude drawing of a man’s body with a horse’s head on a cross, complemented by a statement below: “Alexamenos worships his god.”

And of course, this remained a source of incredulity to non-Christians. As a case in point, virtually every work of early Christian history will include a picture of the famous “Alexamenos Graffito,” an item of third century graffiti from Rome which depicts a crude drawing of a man’s body with a horse’s head on a cross, complemented by a statement below: “Alexamenos worships his god.”

Yes, this is how many ancient Romans reacted to Christian piety toward the cross. So set against this backdrop, the attempt by “Staunch Atheist” to be subversive is anything but. Instead, it is a reminder of the shock and horror of the cross in the ancient world. And it leads us back again to ask that extraordinary historical question: what could lead a first century community to embrace an item of humiliation, torture, and death until it became perhaps the greatest religious icon of all history?

To sum up, the cartoon “If Jesus had been sent to the gallows” brilliantly reacquaints us with the scandal, and the miracle of the early Christian embrace of it. Rarely has an attempt at sacrilege had so felicitous an outcome.

The post If Jesus had been sent to the gallows: On the felicitous outcome of attempted sacrilege appeared first on Randal Rauser.

December 10, 2016

God, Serial Killers, and Natural Evil

Most of my readers will know of Stephen Law, the respected atheist philosopher who has made some perspicuous contributions to philosophy of religion, perhaps most notably in his evil God argument. (In the past I reviewed Law’s book Believing Bullshit and I’ve offered several critiques of his evil God argument, including here and here.)

Today Law offered the following retweet accompanied by his own comment where he opined: “I can’t vouch for the image but the sentiment is widespread.”

— Staunch Atheist (@StaunchA) December 10, 2016

While Law cannot vouch for the image, presumably he can and does vouch for the sentiment. (If he didn’t, he surely should have said as much.)

So what should we think of this tweet … and Law’s sympathetic retweet of it?

A bit like?My first problem is with the wording. What does this meme (if that is what we should call it) mean by saying this one thing (thanking God) is a bit like this other thing (thanking a serial killer)?

Stephen Law is a philosopher. Teaching philosophy is a bit like making a porn film.

How so? Well, in both cases the product (philosophy, porn) appears to many observers to be indulgent, self-gratifying, and unhelpful for conducting the business of daily life.

The lesson: once you want to start associating folks with a highly inflammatory act — thanking a serial killer; making a porn film — you better be clear on exactly what you mean by saying the one thing is a bit like the other. Otherwise, you’re simply poisoning the well of public discourse.

As for the meme, what might the alleged point of comparison be? I take it we can agree that thanking a serial killer is morally problematic generally and insensitive to victims specifically. So perhaps the meme is claiming that thanking God is likewise morally problematic generally and insensitive to victims specifically.

Is that true?

Bait and SwitchHere’s the first, enormous, glaring problem. This meme engages in a truly nasty bait and switch. Take a look again at the wording. According to the meme, thanking God for sparing you in a natural disaster is equivalent to thanking a serial killer for stabbing the family next door.

But of course, these are not equivalent. Rather, the equivalence would be this:

(1) thanking God for sparing you in a natural disaster is equivalent to thanking the serial killer for sparing you.

Or this:

(2) thanking the serial killer for stabbing the family next door is equivalent to thanking God for killing other people in a natural disaster.

Needless to say, the type of actions described in (1) are quite different from the type of actions described in (2). The former focuses on the self that was sparred, while the latter focuses on the victims who were killed.

Clearly both actions described in (2) are deplorable. But nobody is defending theists who thank God for killing people in natural disasters.

What about (1)? Are these actions both morally problematic? That isn’t obvious. If I were sparred by a serial killer I could envision myself thanking him (or her) even while I regretted deeply the deaths of others. And even if I might also struggle with survivor’s guilt for years to come. And if I were sparred in a natural disaster I can envision myself thanking God even if I deeply regretted the deaths of others. And even if I might also struggle here with survivor’s guilt for years to come.

“Fair enough,” you reply, “but those who died at the hand of the serial killer were murdered. So did God murder people as well?” Yes, that is the next question, isn’t it? So let’s turn to it now.

Is God like a serial killer?Is God’s action in nature relevantly analogous to a serial killer’s actions in nature? To answer that question we need to deal with two points: intention and action.

But before going further, we first need to have a definition of God in place so we know what kind of being we’re discussing. Since Law is a philosopher, he is well familiar with the rigorous definition of God in perfect being theology, a concept which is captured in Anselm’s famous description of that being than which none greater can be conceived. In other words, God is that being who exemplifies a maximal set of compossible great-making attributes.

PBT represents the mainstream of academic discourse on the doctrine of God. However, this is not just an ivory tower notion. I would add that having taught in churches, a Christian college and a Christian seminary for fifteen years, the technical Perfect Being Theology definition effectively captures the tacit understanding of the average lay-Christian as well. To be sure, the average Christian cannot articulate the doctrine on their own. But once it is explained to them, they almost invariably agree. In fact, in fourteen years I have never had a student in systematic theology who disputed the PBT definition once it had been explained to them.

So how does God, so described, compare to a serial killer? God, as we’ve said, is understood to be a perfect being, a status that includes maximal wisdom, goodness, and knowledge. By contrast, a serial killer is likely a clinical psychopath, in other words a person who suffers from a severe personality disorder which manifests itself in extremely callous, anti-social behavior.

Intention and ActionWith that in mind, let’s turn to the first point: intention. As Stephen Law surely knows, theists (and Christians in particular) most emphatically do not believe that God engages in acts of evil. Consequently, if God engages in an act that appears to be evil, God must have morally sufficient reasons for it. Needless to say, the serial killer does not.

Please note, whether or not you agree with various theodicies and defenses is not the issue. The point, rather, is that the theist’s perspective on God’s intentions is completely different from the serial killer’s intentions. Thus, suggesting any moral equivalence in their respective intentions is wholly spurious.

Second, what about action? At this point, one would need to establish that God acts through natural processes in a way that is relevantly analogous to a serial killer directly using an implement (e.g. a knife) to kill his hapless victims. For anybody who has spent five minutes reading the extensive literature on divine action, this is a highly contentious assumption, to say the least.

In my book Faith Lacking Understanding I devote a chapter to distinguishing two possible models of divine action which I call the Transcendent Agent Model and the Immanent Agent Model. These two models represent the mainstream division of opinion on divine action among systematic and philosophical theologians today. And on neither model is it obvious that God’s action in natural events are relevantly analogous to a serial killer directly using an implement to kill his hapless victims. To say the least, much more work is required here than this meme provides.

Thus, there is as yet no reason to believe that God’s intentions and actions area bit like those of a serial killer in any morally relevant sense.

ConclusionIn sum, this is a mean-spirited and misleading meme which, as I suggested above, does nothing more than poison the well of public discourse. And God knows we already have enough of that.

The post God, Serial Killers, and Natural Evil appeared first on Randal Rauser.

December 9, 2016

Politically Incorrect Roadside Signs

The other day I found myself wasting time at a site that has a wealth of old photos of the city I grew up in (Kelowna, BC) as well as the surrounding environs (the Okanagan Valley and southern British Columbia). I especially enjoyed the politically incorrect roadside signs and I’ve selected two for your viewing pleasure.

When starting a fire was a capital offenseOur first sign is from the late 1950s/early 1960s. “Ye Olde Manning Park Gallows” is a rather clever, if terrifying sign which is intended to discourage motorists from discarding lit cigarettes out their window, lest they inadvertently start a fire in Manning Park.

Fire prevention has long sought recourse to subtler forms of intimidation: Smokey the Bear may seem calm now, but if you ever started a fire, you knew he could disembowel you in a moment. Still, there is something especially disconcerting about being hanged from the gallows.

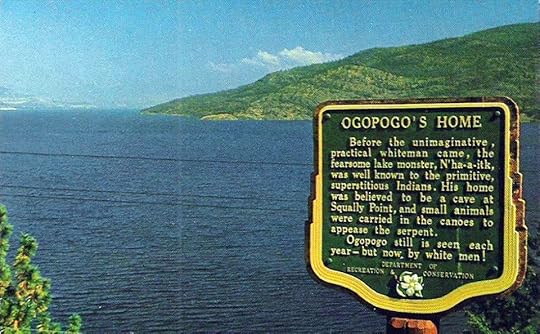

This next sign is one of my favorites. First, some background. Kelowna is situated on Okanagan Lake, a 135 km long and 761 ft deep lake, which is famous for being the home of Ogopogo, one of the more well-known lake serpents in the world after the fabled Loch Ness Monster.

This roadside sign, erected by the Government of British Columbia, stood for years beside the lake about half an hour south of Kelowna. This particular postcard is probably forty years old, and the dated references to “primitive, superstitious Indians” and “white men” certainly make folks blush today. Big surprise, this very politically incorrect sign was still standing in 1996 when I stopped to take a picture of it. However, my guess is that it was probably removed not long after, a racist and sexist relic of an earlier time.

These days folks often like to poke fun at political correctness, and there is no doubt that there are occasions where it can go to far. But would we really want to return to a time when only white men could see Ogopogo?

I don’t think so.

The post Politically Incorrect Roadside Signs appeared first on Randal Rauser.

December 8, 2016

These Folks Are My Kind of Christians

Remember how the Grinch’s heart grew three sizes that day?

Heck, that ain’t nothin’. This new video from Praynksters will make your heart grow four times. So watch the video and then visit the Praynksters YouTube Channel.

The post These Folks Are My Kind of Christians appeared first on Randal Rauser.