Randal Rauser's Blog, page 131

January 19, 2017

“You’re an atheist with respect to every other God. I just go one God further”: A Brief Reply

If you’re a Christian and you’ve invested much time talking to average atheists, you’ve likely encountered this potted rejoinder: “You’re an atheist with respect to every other god. I just go one god further.” The idea, presumably, is that there is something inconsistent and arbitrary about belief in a particular understanding of God. It is more consistent to disbelieve all deities than believe in one.

To state what should be obvious, this “arbitrary objection” ignores the particular conditions and reasons that explain why particular individuals come to believe in one particular understanding of God rather than another.

Sometimes our potted rejoinder is invoked with the somewhat different intent of minimizing the difference between theism and atheism. What’s the difference between a theist and an atheist worldview? Not as much as you might think, so the reasoning goes: you’re an atheist with respect to every other God. I just go one god further.

This “trivial difference” objection is also a non-starter. To see why, let’s shift the context from atheist and theist to bachelor and husband. Our bachelor attempts to close the gap with the husband like this:

“You’re a bachelor with respect to every other woman. I just go one woman further.”

Um, that’s not how it works, bachelor. Once you’re married you’re not a bachelor. And once you believe God (under some description) exists, you’re no longer an atheist, period.

The post “You’re an atheist with respect to every other God. I just go one God further”: A Brief Reply appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 18, 2017

God, Evolution, and Creation: A Short Interview

Here’s are some clips from an interview I did with Pastor Todd Petkau of Riverwood Church in Winnipeg. In these clips we discuss creation, Darwinian evolution, and doubt.

Dr. Randall Rauser Interview – Unapologetic from Riverwood Church on Vimeo.

The post God, Evolution, and Creation: A Short Interview appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 16, 2017

Does the hostility of the universe toward life support atheism?

Justin Schieber argues that it does.

I disagree.

And then we argue our positions for an hour.

And things get heated. Harsh words are spoken. Tears are shed.

(Just kidding about that last bit.)

But we do argue. For an hour.

Still sound interesting?

Check out our moderated informal debate on the Serious Inquiries Only Podcast.

And don’t worry, you don’t need to be that serious to listen.

The post Does the hostility of the universe toward life support atheism? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 15, 2017

Faith That’s Not Blind: A Review

J. Steve Miller, Faith that’s Not Blind: A Brief Introduction to Contemporary Arguments for the Existence of God (Acworth, GA: Wisdom Creek Academic Press, 2016).

J. Steve Miller, Faith that’s Not Blind: A Brief Introduction to Contemporary Arguments for the Existence of God (Acworth, GA: Wisdom Creek Academic Press, 2016).

In Faith that’s Not Blind, J. Steve Miller gives exactly what the subtitle promises: a brief introduction to contemporary arguments for God’s existence. At twenty chapters, seventeen arguments, and 125 pages (endnotes included), the book definitely is brief and fast moving. But given Miller’s easy and engaging style of writing and chapters averaging three pages, it is also compulsively readable. I finished the book in a couple hours.

The twenty chapters are divided into six sections: “Evidence from Dramatic Religious Experiences,” “Evidence from the Beginning of the Universe and the Origin of Life,” “Existential Fit,” “The Phenomenon of Widespread Belief,” “Is Contrary Evidence Compelling? ” and “On Risk Assessment and Pascal’s Wager.”

I thought it very interesting that Miller devotes that first section to an area of study long neglected in much contemporary apologetics, viz. near death experiences (NDEs), supernatural encounters, and miracles. Perhaps this isn’t surprising, however, since Miller devoted a previous book to NDEs and out of body experiences (OBEs). (See my review here. See also an article Miller wrote on the topic at my blog here.) I share Miller’s conviction that there is a lot of material here that is of interest when developing critiques of naturalism. (See, for example, my article “Apologetics and the Crisis Apparition.” See also chapter 17 of God or Godless, titled “God Best Explains the Miracles in People’s Lives.” )

In case you missed it, I just summarized two of the book’s virtues: it is compulsively readable and it includes material often overlooked in contemporary apologetics. To those, let me add a third: the book includes a range of recommended resources in each chapter — books, articles, websites — for further reading. All told, this book provides the novice with a great springboard for further study and reflection in the field.

If those are the virtues, what about the vices? Not surprisingly, this section of the review will be substantially longer if for no other reason than that it takes more time to explain disagreement.

Let’s begin with something trivial. I know we’re not supposed to judge books by their covers, but we all do anyway. (My readers were merciless with the terrible cover Wipf and Stock put on my 2015 book Is the Atheist My Neighbor?) Where Faith that’s Not Blind is concerned, my first reaction was that the cover looked like a teen devotional from the 1980s: definitely room for improvement here.

As for the book itself, the most glaring problem is that the survey is very one-sided. Miller includes one short chapter of three pages for arguments against God’s existence. Titled “Objections to Theism Aren’t Insurmountable,” the chapter devotes one page to the problem of evil and a second page to Richard Dawkins’ argument against a creator.

Unfortunately, the analysis in this very brief treatment is problematic. Miller’s response to the problem of evil is two-fold. First, he notes that the theist may surrender or revise their understanding of one or more of God’s attributes. While this is technically true, it is also misleading. The problem of evil is directed at the conception of God as a being that is omnipotent, omniscient, and omnibenevolent, and insofar as the theist is forced to reject or revise one of those attributes, the argument is successful.

Perhaps the bigger problem here is that Miller leaves the impression that the problem of evil is exhausted by the logical problem of evil. Since the logical problem of evil is widely considered a failure today, he leaves the reader with the impression that the theist is out of the woods. But of course this isn’t true: even if the logical problem fails, there are a range of inductive or evidential problems of evil with which to contend. Moreover, there is also a large body of literature on specific problems of evil including the problem of animal suffering, the problem of suboptimal design, and the problem of moral horrors (events for which it seems there simply could not be an outweighing good). And then there is the problem of divine hiddenness which is a problem distinct from evil. Far from being out of the woods, the theist is still deep in the forest.

I also didn’t think that Dawkins’ terrible argument against a designer deserved equal time to the problem of evil. But the bigger problem here is that Miller failed to provide the most effective rebuttal to Dawkins. Miller counters Dawkins by invoking the attribute of divine atemporality (an attribute that many classical theists reject). But in my view, Miller ought instead to have countered Dawkins by making the following two points: (i) God is metaphysically simple, not complex; (ii) Dawkins’ argument assumes a spurious principle of explanation according to which a good explanation is that which invokes a cause simpler than the effect it purports to explain. But that is absurd and thus Dawkins’ argument fails.

Miller also includes a chapter titled “Positive Arguments for Naturalism Don’t Prevail.” As with his treatment of evil, Miller’s treatment of naturalism is cursory at best. He writes:

“Typically, I don’t find atheists forwarding positive arguments for naturalism. If a positive argument is presented, it might boil down to: ‘A lot of things have been shown to be explained by purely natural processes. Therefore, we should expect that everything has a natural explanation, even if we have yet to find it.'”(98)

I’ll take Miller at his word that this has been his experience. But then that suggests that he is simply not familiar with the extensive philosophical literature defending naturalism. As a fine segue into that literature, I would advise readers to pick up a copy of my book Is the Atheist My Neighbor? (the one with the ugly cover) and turn to chapter 4, beginning at page 51. There you will be able to read Jeff Lowder’s succinct defense of atheism and naturalism. Needless to say, it bears no resemblance to Miller’s description.

I also disagree with Miller’s categorization and characterization of some arguments for God’s existence. For example, chapter 11 refers to “Sensing a God-shaped Vacuum.” It seems to me that Miller is talking about the Argument from Desire here. But then it would have been clearer to identify it as such. And the phenomena that Miller describes in chapter 12 as “a Paradigm Shift or Gestalt Experience” would, in my opinion, better be understood as the proper basicality of belief in God.

I also found some of Miller’s summaries to be hampered by a confusion of concepts. For example, in chapter 14 he refers to “Objective Morals” as being best explained by God. Unfortunately, he fails to distinguish adequately between moral value and moral obligation. Miller appears to vacillate between the two but they are very different topics. And while Miller associates Kant with the argument from morality, this is a confused attribution given that Kant’s famous practical argument was not based on an appeal to moral value or obligation. Rather, Kant appealed to God to explain the posthumous satisfaction of justice. Finally, Miller misses the opportunity to develop an argument for moral knowledge which, in my opinion, is among the strongest moral arguments for theism.

Miller titles each chapter an “exhibit” so that the book really consists of twenty exhibits that seek to build a cumulative case argument for theism. It’s an interesting approach to the discussion set within the loose metaphor of a courtroom. And much of the evidence Miller presents is definitely worthy of more careful consideration. Needless to say, at 10 bucks this book is also priced very reasonably.

At the same time, I can’t overlook the fact that Faith that’s Not Blind gives such short shrift to opposing counsel. For that reason, I would only recommend the book as an introduction to arguments for God’s existence if it is supplemented by additional sources covering atheism, naturalism, and the various objections to the arguments Miller surveys.

If you benefited from this review please consider upvoting it at Amazon.com.

Thanks to Steve Miller for sending me a review copy of the book.

The post Faith That’s Not Blind: A Review appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 14, 2017

Does doctrinal agreement constitute evidence against God’s existence?

Justin Schieber and I debate this question in our book An Atheist and a Christian Walk into a Bar. We recently took the show on the road with an in-depth and spirited debate on this question at Unbelievable with Justin Brierley. Click here to listen to the show with Randal, Justin, and Justin. And then join the discussion.

The post Does doctrinal agreement constitute evidence against God’s existence? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 12, 2017

Some Unbelievable Reflections

A couple days ago Justin Schieber and I appeared on an episode of Unbelievable with Justin Brierley in which we debated the question of whether widespread religious (or theological) disagreement constitutes evidence that God does not exist. More on that in a moment.

This is my sixth appearance on Unbelievable. Over the years I have been on the show debating with Ralph Jones, John Loftus, Hemant Mehta, and Michael Ruse. I also recorded a show with Alom Shaha that was more of a dialogue than a debate. I’ve done dozens of radio and podcast interviews over the years, and Unbelievable is always at the top of my list due to the quality of the guests, the winsome host, and the show’s format. Host-wise, Brierley not only seeks to be a balanced moderator, but he also is informed on the issues. And as a result, he’s very skilled at asking probing questions, at pressing guests for clarification, and at leading the discussion. As for the format, ten or fifteen minute radio spots allow for little more than a handful of talking points, but on Unbelievable you’ve got time to develop your points and have some good old fashioned banter hashing out a topic.

Of all the shows I’ve done in the past, the Devil’s Advocate episode with Michael Ruse was my favorite for two reasons: first, on that show we swapped roles: I defended atheism and Ruse defended Christian theism (of a rather liberal sort); second, Ruse himself is a charismatic, affable, and intelligent interlocutor. The result, I think, was some engaging and worthwhile radio.

Note I said that the Ruse show was my favorite of past shows. From my perspective, the upcoming show with Schieber is every bit the equal of the Ruse exchange. This is a very, how shall I put it, productive exchange, one in which we manage to cover a range of issues pertinent to the topic with concision, clarity, and Unbelievable‘s trademark courtesy.

So check it out the episode this Saturday. And then buy the book!

The post Some Unbelievable Reflections appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 10, 2017

Bad Atheist Memes: God, Sexuality, and Bacteria

Over the last couple weeks Jeff Lowder has forwarded me a few painfully bad atheist memes. (Keep it up, Jeff! These are always fun for a slow news day.)

Here’s the one he tweeted me this morning:

#Atheism #Atheist #God pic.twitter.com/9wv6bFafdW

— Atheist Khan (@Atheist_Khan) January 8, 2017

I replied: “Why? Because human sexuality is of no more moral or ontological significance than bacterial reproduction?”

I mean seriously, this stuff writes itself.

The post Bad Atheist Memes: God, Sexuality, and Bacteria appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 9, 2017

Who are the Hollywood Elites?

Yesterday Meryl Streep delivered a powerful and eloquent speech at the Golden Globe Awards. It was a speech that expressed great concern for justice and compassion, for defending the wayfarer and the marginalized, for promoting civility and kindness, for encouraging empathy and understanding. In short, it was a speech that one would expect any Christian to cheer.

Instead, the response I heard from several Christian conservatives in social media was scathing. I’m not sure if any of them actually watched the speech. But I did read several times that Streep and the “Hollywood elites” are “liberals”. Presumably once we’ve affixed the proper labels, we don’t need to worry about what Ms. Streep actually said.

But I wonder, who are the Hollywood elites anyway? Meryl Streep is apparently a Hollywood elite. But what about David Haig? He’s a lesser known actor who appears in Streep’s most recent movie, Florence Foster Jenkins. Is he a Hollywood elite? What about Eveline Chapman? She has appeared in but a handful of movies: in Florence Foster Jenkins she plays an unaccredited “girl on street”. Is she an elite too? What about the film’s screen writer, Nicholas Martin? Is he a Hollywood elite? What about the film editor Valerio Bonelli? Caroline Smith, the set decorator? Consolata Boyle, the costume designer? David Dorling was a hair stylist on the film. Is he a Hollywood elite too? Louise Young was a makeup artist. Elite? Jason Rickwood, third assistant director; Josh Bell Chambers, stagehand; Charlie Cobb, illustrator: elites, the lot of them? (See the IMDB entry on the film for further data.)

Let’s shift our gaze for the moment from Florence Foster Jenkins to Harold Cronk. Mr. Cronk is the director of such Pure Flix films as God’s Not Dead and God’s Not Dead 2 (the former of which exceeded Florence Foster Jenkins’ box office by a good $20 million). While Mr. Cronk may not be pulling in the same fees as Michael Bay, I’m quite confident that he makes more money in film than Florence Foster Jenkins’ Eveline Chapman, the unaccredited “girl on street” and Louise Young, makeup artist. So is Cronk an elite too?

And if so, can we extend our harangue and our labels to all the elites at Pure Flix?

I really would love some direction on how to use labels like “Hollywood elites”. I hope there’s something more at play here than mindlessly labeling individuals who express opinions you don’t like. But alas, I’m not so sure.

In the interim, why don’t we all watch Meryl Streep’s speech again?

The post Who are the Hollywood Elites? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 8, 2017

I feel love. It’s about love: Still Alice as Theodicy

Lisa Genova’s 2007 novel Still Alice tells the story of Harvard professor and scholar Alice Howland and her journey living with early onset Alzheimer’s Disease. Howland is a few months into her fiftieth birthday when she receives the terrible diagnosis. From there the book follows her on her slow and painful decline into dementia.

Lisa Genova’s 2007 novel Still Alice tells the story of Harvard professor and scholar Alice Howland and her journey living with early onset Alzheimer’s Disease. Howland is a few months into her fiftieth birthday when she receives the terrible diagnosis. From there the book follows her on her slow and painful decline into dementia.

At first blush, God is conspicuously absent from Still Alice. At one point Howland wanders into a church as she is wrestling with the emotional fallout from her diagnosis. But she has long been alienated from the church and any religious faith, and nothing much changes in that regard.

However, one would be mistaken to conclude that the book lacks spiritual depths to explore. When tragedy strikes, the inevitable question arises: why? God may not be a visible part of Alice’s life, but she asks the question just the same. Why Alice? And why so young?

To make matters worse, there is an especially cruel irony in a scholar who made her life with words — Alice is a linguistics professor — losing the very mind that gave her those words. At one point Alice states that she would much rather have a cancer diagnosis. There would at least be hope, a chance to fight the disease. And with cancer comes a deep and wide network of social support. When it comes to Alzheimer’s, all one has is the stigma.

So why Alice? Let me state up front that any attempt to offer a comprehensive and definitive answer to that question is foolhardy at best and manifestly offensive at worst. But if it is beyond our scope to offer the answer, we can at least undertake a more modest route by proceeding like this. We begin by identifying putative goods that were acquired through the suffering which arguably would not have been acquired otherwise. Given that those goods come about through that suffering, we can argue that the goods provide at least a small part of the answer to the question: why that suffering?

What kind of goods am I thinking of? Well, consider what typically happens when people face a life-threatening diagnosis: they reorient their priorities. They recognize, for example, that spending time with family is more important than a job promotion and that healing fractured relationships trumps a new BMW.

It becomes clear as the narrative unfolds that Alice devoted a disproportionate amount of her life to developing her stellar career. She is Dr. Alice Howland, Professor of Linguistics at Harvard University. This identity is important, but Alice’s identities as wife and mother have suffered as a result. All this begins to change with the diagnosis.

Alice and her husband John were both dedicated to their respective careers. And as her disease develops it becomes increasingly clear that this was to the detriment of their marriage. As Alice’s decline continues — she has mere months of lucidity remaining — John receives a job offer in New York. He wants to accept it, to take Alice away from her home and children. Alice resists, begging John to remain in his current post so she may remain in familiar surroundings and close to the children.

Frustrated, John retorts: “If I don’t take this, I could ruin my one shot at discovering something that truly matters.” (234) What really matters? John, are you kidding me?

But before we’re too hard on John, let’s admit that his sentiment is understandable. He is doing important scientific work, and this is a great opportunity, and Alice is already in significant decline. Still, he speaks as a scientist concerned with his career, not a husband concerned with his declining wife. The fact is that like a refiner’s fire, Alzheimer’s brings to the fore the superficialities of John and Alice’s marriage and the importance of reorienting their priorities.

But the most profound and moving relationship unfolds between Alice and her youngest child, Lydia. Alice’s two older children followed her down the path of an all-consuming career. But Lydia has eschewed this path in favor of the life of a free spirited, struggling actor. This failure to conform to Alice’s expectations alienates Lydia from her mother’s all-too-conditional affections. It’s the kind of relationship that can just barely keep it together for a Thanksgiving dinner.

All that begins to change with the advent of Alzheimer’s. As her self-worth as linguistics professor is gradually taken from her, Alice begins to reorient herself back to the identity that matters most: mother. She realizes that a career is not nearly as important as loving and being loved. Rather than continue to alienate her youngest child, Alice begins to learn the beauty of unconditional, loving acceptance:

“You’re so beautiful,” said Alice. “I’m so afraid of looking at you and not knowing who you are.”

“I think that even if you don’t know who I am someday, you’ll still know that I love you.”

“What if I see you, and I don’t know that you’re my daughter, and I don’t know that you love me?”

“Then, I’ll tell you that I do, and you’ll believe me.” (230)

Is it really true?

As the Alzheimer’s progresses, Alice’s fears are realized. Eventually Alzheimer’s takes even the recognition of her beloved child’s face and Lydia is reduced to being “the actress.” At one point the actress performs for Alice:

The actress stopped and came back into herself. She looked at Alice and waited.

“Okay, what do you feel?”

“I feel love. It’s about love.”

The actress squealed, rushed over to Alice, kissed her on the cheek, and smiled, every crease of her face delighted.

“Did I get it right?” asked Alice.

“You did, Mom. You got it exactly right.” (292)

The post I feel love. It’s about love: Still Alice as Theodicy appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 5, 2017

On Rejecting Expert Consensus: Don’t Blame Donald Trump

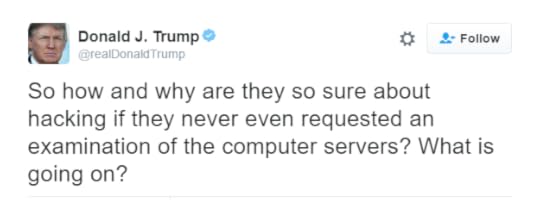

As of this evening, Donald Trump continues to challenge the consensus of 17 security agencies that the Russians were behind the DNC hacking to the end of influencing the 2016 election. Why does Trump deny this? Here’s his latest tweet:

Need it be said that this is a foolish tweet? Trump knows nothing about the extraordinarily complex and diverse work of the many security agencies that, after careful and extended investigation, have drawn a measured conclusion based on abundant and varied evidence.

It is certainly disturbing to think that a PEOTUS can cavalierly dismiss the consensus of experts with such bracing ignorance.

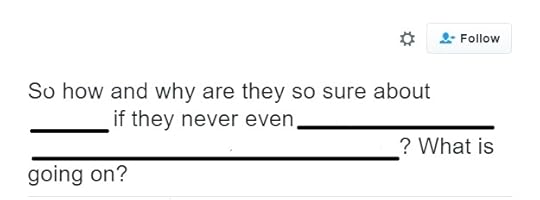

But let me tell you what is more disturbing: the fact that this kind of behavior is common. I see it all the time. Let’s start with the basic template:

Now you just need to fill in the blanks. In the first blank you can insert “climate change” or “evolution” or “the age of the earth” or “Jesus existing” or any number of other topics. And in the second blank you can insert some asinine observation.

For example, you could take aim at the climatologists:

“So how and why are they so sure about climate change if they never even considered that Alberta is having a brutal winter this year? What is going on?”

Or perhaps the New Testament scholars and ancient historians:

“So how and why are they so sure about Jesus existing if they never even considered that the Gospels were anonymous third hand legends? What is going on?”

Or maybe the evolutionary biologists:

“So how and why are they so sure about evolution if they never even considered that there are no transitional fossils? What is going on?”

Or how about the geologists:

“So how and why are they so sure about a local flood if they never even considered that the Grand Canyon was formed in a few days during a global catastrophe? What is going on?”

Needless to say, the point is not to believe experts (intelligence officers, climatologists, ancient historians, evolutionary biologists, geologists) blindly. Of course a consensus can be wrong. And we do need iconoclasts every once in a while who can challenge the consensus. The point, rather, is that these iconoclasts need to know what they’re talking about. They need to have done their homework. They need to ask intelligent questions and make provocative points.

It isn’t enough to ignore a consensus of expert opinion simply because you don’t like it, because it doesn’t fit your assumptions about the way the world should be.

And yet people do it all the time. So don’t blame Donald Trump. He’s merely the product of a culture in which the cavalier, irrational dismissal of experts has increasingly become the norm.

The post On Rejecting Expert Consensus: Don’t Blame Donald Trump appeared first on Randal Rauser.