Randal Rauser's Blog, page 130

February 7, 2017

An Atheist and a Christian Walk into a Book Tour (sort of)

A book tour? Well, maybe that’s stretching it. But Justin Schieber and I do have a few events scheduled for March.

Edmonton, Alberta

To begin with, Justin is flying up to Edmonton on March 9th courtesy of the Society of Edmonton Atheists. While he is in Edmonton, we’ve scheduled a couple events thus far. To begin with, on Friday night we will be having a debate at Taylor Seminary. We’re calling this event a “Christian-Atheist Dialogue” because it will be more informal than a standard debate. While we will have opening statements, after that point we’ll be launching into a back-and-forth dialogue.

Next, on the Saturday morning we’ll be having a breakfast event at my church, Greenfield Community Church from 10:00-11:30 am. We’ve tentatively titled this event Ask an Atheist, Ask an Apologist and it will largely consist of open mic discussion with the audience about Christianity and atheism. We hope to get a good mix of Christians, atheists, and everyone in between at this event for some interesting conversation.

We also are currently looking at booking an event for Saturday evening. TBD.

Tucson, Arizona

Currently we are also scheduled to be flown down to Tucson in March by Freethought Arizona. We currently have two events scheduled:

Freethought Arizona: March 19th, 10am

Sierra Vista Freethinkers: March 19th, 3pm

We also have a couple book signings scheduled at Barnes and Noble for March 18th. But we’d like to schedule an additional event for the evening of March 18th. If you know of any groups (churches?) that would be interested in hosting an event in Tucson on that evening, let me know.

The post An Atheist and a Christian Walk into a Book Tour (sort of) appeared first on Randal Rauser.

February 5, 2017

Contributing to a new political blog

Folks who like Trump or dislike politics will be happy to know I won’t be talking Trump in my blog anymore. Instead, I have become a contributor to Jeff Lowder’s new blog Opposing Trump and I just posted my first contribution today, “Revenge of the Haters: A Response to Kellyanne Conway’s Abysmal Defense.” So if you’re interested in my ruminations on politics and truth, feel free to read. Otherwise, stay-tuned here for more non-Trump content in the days, weeks, months, and years to come.

The post Contributing to a new political blog appeared first on Randal Rauser.

February 2, 2017

The Not-So-Intelligent Designer: A Review

Abby Hafer, The Not-So-Intelligent Designer: Why Evolution Explains the Human Body and Intelligent Design Does Not. (Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2015).

Abby Hafer, The Not-So-Intelligent Designer: Why Evolution Explains the Human Body and Intelligent Design Does Not. (Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2015).

If you love intelligent design, you’ll (probably) hate this book.

If you hate intelligent design, you’ll (probably) love this book.

If you’re somewhere in-between in your assessment of intelligent design, you’ll probably find yourself somewhere in-between when it comes to this book.

Beyond the Kluge

I initially requested a review copy of Abby Hafer’s The Not-So-Intelligent Designer because I’m interested in the concept of a kluge. A kluge is, a “work-around” or “an ill-assorted collection of parts assembled to fulfill a particular purpose.” If evolution is true, one should expect to find kluges throughout nature. And that is what one does, in fact, find: imperfect structures and systems which work well enough but which are very far from ideal. Given the title of this book I assumed that Hafer would be discussing the concept of a kluge.

Not exactly. Hafer never uses the term “kluge,” preferring to focus instead on the broader category of “bad design.” While some of the ten examples Hafer cites are kluges (the eye, for example), others are not. For example, she discusses the appendix, an organ which she says has no purpose at all. It turns out that that may not be true. But regardless, Hafer understands the appendix to be vestigial and thus not a kluge.

So Hafer’s vision is wider than my original interest. But that’s not a bad thing. Indeed, for the most part I quite enjoyed her engaging and wry survey of so-called “bad” designs, ranging from the vulnerable placement of the human male’s testicles to the blindspot in the human eye.

The Designer and God

The purpose of chronicling these ten exhibits of bad design was part of a broader, merciless rhetorical assault on intelligent design (henceforth ID). The point of recounting these ten exhibits of bad design is to challenge ID theory by arguing that we’re not designed after all, the assumption being that if we were designed that design would be better than it is.

But why think this? Presumably that depends on the skills and intentions of the designer. Throughout the book Hafer assumes that the designer in ID theory is God. It’s ironic that she is so confident ID theorists all believe the designer is God given that she repeatedly insists that ID theorists can agree on hardly anything, perhaps not even gravity. So what basis does she have to believe unanimity exists on this point?

There are at least two problems with Hafer’s assumption. First, ID theorists insist that one cannot invoke God as part of the design inference, even if one is a theist who believes God is the designer. Qua the theory, one can only invoke a cause sufficient to explain the effect in question and the traditional attributes of deity (e.g. omniscience, omnipotence, etc.) are not required as explanatory posits. So the ID theorist cannot appeal to God as the designer. This point is stated ad nauseam in ID literature, so I can’t help but suspect that Hafer reveals a willful ignorance on the point.

Second, Hafer overlooks the crucial fact that some of the leading proponents of ID theory including Steve Fuller, David Berlinski and Bradley Monton are atheists/agnostics. While these scholars are supportive in principle of ID theory, they are not yet persuaded that a design inference is warranted; nor would they necessarily believe God was the designer should that inference become justified.

ID Confusions

Unfortunately, Hafer’s confusion on ID is not limited to the identity of the designer. Hafer also misrepresents the relationship between ID theory and evolution. While she notes in passing that leading ID theorist Michael Behe accepts common descent, including the common ancestry of humans and chimpanzees (21), she conveniently sets this fact aside for the bulk of the book and instead frames the debate as one between ID and evolution simpliciter. To be sure, many advocates of ID reject various aspects of evolutionary theory, but that opposition is not a part of ID theory itself.

Hafer makes much of the Discovery Institute’s infamous Wedge Document and its stated opposition to scientific materialism. And what is scientific materialism? Hafer writes that the Discovery Institute means “believing in the material world. If you only accept evidence from the material world, evidence like things you can actually see and hear, then according to ID proponents you are a ‘materialist.'” (30) This is an absurd definition. ID theorists are opposed to ontological materialism and methodological naturalism, and neither concern bears any relationship with this gobbledygook description.

Hafer insists that ID is not science. And to drive the point home she does an interesting word study of ID literature to show that it uses terminology more in keeping with theology and philosophy than science (see chapter 28). This is exactly right, and it’s a point I’ve sought to make for quite a while now. Unfortunately, Hafer doesn’t understand the significance of the point.

Here’s the lesson: ID theory is not science. But it is a philosophy of science. The ID theorist objects to methodological naturalism’s exclusion of intelligent causes from the tool box (to use Paul Nelson’s metaphor) of scientific explanation. And they give examples where inferences to intelligence are already invoked in scientific explanation. Perhaps the most well known example is SETI research. In recent years the search for planets has revealed another interesting example: the possibility of detecting a Dyson Sphere.

Conflating ID with the Discovery Institute

Hafer also conflates ID theory with the Discovery Institute. And she spends a lot of time attacking the Discovery Institute. I share some of Hafer’s concerns about the Discovery Institute, and I find the parallels she draws between the Discovery Institute and the old tobacco lobby (see chapter 26) to be illuminating and disturbing.

But the Discovery Institute is not ID theory. Rather, it is a political and social activist group which seeks to promote ID in the public square. But one should be able to distinguish the sometimes unseemly and misguided conduct of the Discovery Institute from the concept of ID itself.

Hafer’s book is a blistering polemic punctuated by sardonic humor. That makes for entertaining reading, especially for those who already have it in for ID. But it is not the place to find nuanced and charitable engagement. Having collapsed ID into the Discovery Institute and reduced the Discovery Institute to the equivalent of the amoral tobacco lobby, she has no time, patience, or interest in considering the academic work of its leading scholars.

Some Logical Fallacies

The book commits several logical fallacies. As you might have guessed, strawman is one of them. Hafer repeatedly caricatures ID positions as in the fallacious description (cited above) of scientific materialism. The following passage provides another good example of strawmanning:

“ID folks often like to talk about probability. They say that getting the organisms we have today by way of random mutations followed by natural selection is too improbably to be true. They point out that the odds of getting any particular organism are exceedingly small, and therefore they claim that evolution is impossible.

“This is like saying that because the odds of your being born are exceedingly small, given that your two parents had to meet and reproduce on just the right day to have that particular sperm and egg meet that later became you, and given that the same thing had to occur for all the generations before you, these odds are extremely small, and this somehow means that it is actually impossible to that you were born at all.” (160-61).

Needless to say, Hafer’s absurd analogy merely shows either that she doesn’t understand the ways that folks like Dembski and Meyer justify design inferences … or she is intentionally misrepresenting them. This is especially ironic when Hafer writes things like this: “Unfortunately it appears that ID promoters have deliberately overlooked all the information that is available on this subject [the blood clotting cascade]. Either that, or else they don’t know how to read.” (96)

Um, yeah…

Hafer also repeatedly commits the genetic fallacy. For example, she identifies the origin of the term “intelligent design” with an attempt to rebrand the creationism referenced in the textbook Of Pandas and People to make it fit for public consumption. This is an interesting historic detail, but even if the term and related movement did originate in such ignominious circumstances, that bears no direct relationship to the assessment of the quality of arguments currently offered for ID.

Finally, Hafer regularly invokes ad hominem arguments and base insults against ID theorists. For example, she opines: “in the more than twenty years that ID has been in existence, none of its promoters has run a single experiment. The only thing they’ve run is their mouths.” (155)

Conclusions

I understand why Hafer is so merciless when it comes to advocates of ID. After all, I have no sympathy for the tobacco lobby and if ID is just the tobacco lobby revisited then let ’em have it! The problem is that ID isn’t just the tobacco lobby revisted, even if ID’s leading institution, the Discovery Institute, and some of their methods, have unsettling parallels with the strategies of the tobacco lobby. ID also isn’t any one person (e.g. William Dembski; Michael Behe) or any particular theoretical proposal (e.g. irreducible complexity; minimal function).

At it’s core, ID is a simple idea, the idea that under particular conditions, scientific explanations can legitimately appeal to intelligence. It is an idea that is perfectly consistent with Hafer’s ten exhibits of putative bad design. It’s an idea that deserves to be taken seriously, and that’s why it’s doubly unfortunate that the conversation has deteriorated to this point.

One thing is clear from this book: parties on both sides of the conversation bear responsibility for the current abysmal level of the discussion.

If you benefited from this review please consider upvoting it at Amazon.com.

The post The Not-So-Intelligent Designer: A Review appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 31, 2017

Transgender Boy Scouts: A Crazy Idea?

Big news yesterday:

BREAKING: Boy Scouts of America will allow transgender children who identify as boys to enroll in scouting programs.

— The Associated Press (@AP) January 31, 2017

Here is how Southern Baptist theologian and church leader Russell Moore responded:

This is crazy, IMO. https://t.co/8ddusaaxjD

— Russell Moore (@drmoore) January 31, 2017

I think highly of Russell Moore: he’s a very smart and articulate fellow. But that flippant response left me very disappointed. I believe Moore wouldn’t call it crazy if he spent time with some families of transgender children, if he heard from the parents about their own confusion, fear and pain over their child’s gender dysphoria and their fear and pain every time their child is excluded, alienated, and stared at. Imagine how grateful those parents are to know that the Boy Scouts have now become a place of inclusion and embrace.

Accepting transgender children into the Boy Scouts isn’t a matter of social engineering or deconstructing gender. It isn’t an attack on the “traditional family” or “traditional gender roles.” It isn’t an affront to God’s created design. It is simply an attempt to extend hospitality to vulnerable children who experience distress because their self-perception does not match their sex.

But the deeper issue is this: whether you agree with the Boy Scouts decision or not, it is a reasonable good faith attempt to meet the challenge of a very difficult issue. And it certainly isn’t “crazy”.

The post Transgender Boy Scouts: A Crazy Idea? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 29, 2017

Skeptical Theism and Skepticism Simpliciter: A Response to Jason Thibodeau

In his two-part article “If it’s okay for God to allow horrors, then we don’t know much about God” (Part 1; Part 2) Jason Thibodeau presents an articulate and concise skeptical argument against theism. There is a lot packed into his article, and I’m not going to attempt to address it all here. But in this article I do intend to critique what I take to be the core claim of the first part of his essay.

In the first part Jason argues that neither free will nor greater goods theodicies are sufficient to explain why God would allow the distribution and intensity of evil that we see. This leaves the Christian with skeptical theism according to which God may have reasons beyond our ken for allowing evil. But if that is the case, might God not also have reasons beyond our ken for deceiving us? Here’s how Jason puts the dilemma:

Given the assumption that God has morally sufficient reasons to fail to prevent the deaths of children in hot cars (and the many other horrors that we observe), what we should say is that we are not in a position to judge how likely it is that God has reasons to deceive us or allow us to be deceived about the Bible, the significance of Jesus, our own greatest good, and many other things. But, of course, most theists are not so humble when they speak about what God can do for us and the interest God has in our greatest good, nor can Christians admit that, for all we know, Jesus did not die for our sins.

What Christians ought to say, if they are skeptical theists, is that for all we know, God has very good reasons to allow us to believe that Jesus died for our sins even though he did not die for our sins. About these and many other very important matters, we could be gravely mistaken. We are just not in a position to know whether God has morally sufficient reasons to allow us to be so deceived.

I think Jason does a really good job of presenting his argument. However, I don’t think his argument is successful. Or, to put it another way, I don’t see any problem here unique to so-called skeptical theism. Jason claims that the Christian cannot know a claim like “Jesus died for our sins” because God could be lying. My contention is that mere possibilities like this are not the kind of things that should worry a person. To say they are is to stake out a position in epistemology which leads to skepticism, whether you’re a theist or not.

Let’s begin by getting one thing clear: the central issue at stake is not being lied to; rather, it is forming a false belief. So the problem is this: for all we know, if we listen to God we could be forming false beliefs. Does it follow that theists should be skeptics?

Before you draw that conclusion, consider this: if we listen to anybody telling us anything we could be forming false beliefs. And if we accept the deliverances of our memory we could be forming false beliefs. And if we accept our rational intuition we could be forming false beliefs. And if we accept our moral intuition we could be forming false beliefs. And if we accept the deliverances of our sense perception we could be forming false beliefs.

Philosophers have been wrestling with the worry of skepticism for hundreds of years. They’ve worried that in order to know that-p I must know that I know that-p. So for example, to know that I see an apple I must know that my sense perception is veridical in the conditions under which I form the belief that I see an apple. And to know that Jesus died for our sins I must know that God is testifying truthfully in the conditions under which I form the belief that Jesus died for our sins. Consequently, to know that-p I must know that I know that-p.

The problem is that there is no way to attain that second order knowledge across the spectrum of beliefs formed through sense perception, moral intuition, rational intuition, memory, and testimony. Some philosophers have concluded that we therefore ought to become skeptics about all the sources of belief for which we cannot know that we know (which, as I suggested, is arguably all of them).

I disagree with this dour conclusion. Instead, I reject the assumption that I must know that I know that-p in order to know that-p. (I provide extended discussions of these topics in my book Theology in Search of Foundations and The Swedish Atheist, the Scuba Diver, and Other Apologetic Rabbit Trails. I won’t bother rehearsing those arguments here.) That which is true of the spectrum of deliverances for our belief including testimonial beliefs generally is also true of that subset of beliefs which originate in divine testimony.

This does not mean that one is excused from needing to consider defeaters to the various beliefs we form under diverse circumstances. But it does mean that those beliefs are treated as innocent until proven guilty. Just as I am warranted in accepting the testimony of a stranger when I ask directions unless I have some reason to doubt that testimony, so I am warranted in accepting the testimony of God when I read scripture or pray unless I have some reason to doubt that testimony.

The post Skeptical Theism and Skepticism Simpliciter: A Response to Jason Thibodeau appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 26, 2017

Elective abortion as the right to kill your children

There are few political and social issues as controverted and fraught with mutual animus as the debate over abortion rights. Unfortunately, the heat is only multiplied by the common retreat to unfortunate and misleading rhetoric.

Consider, for example, the practice among some prolifers of referring to abortion as a genocide. This is language that I’ve occasionally heard from prolife advocates, and it is wholly irresponsible. By no plausible definition does access to elective abortion constitute a genocide.

With that in mind, I come to a tweet from conservative commentator Dinesh D’Souza arising out of the massive Women’s March this past week:

Marching for the right to kill children is strange–marching for the right to kill your own children is incomprehensible #WomensMarch pic.twitter.com/Hn9DNHVrVJ

— Dinesh D'Souza (@DineshDSouza) January 22, 2017

What about D’Souza’s description of the right to (therapeutic and elective) abortion as the right to kill children. Is this another example of irresponsible rhetoric?

First up, let me note that I am no fan of D’Souza. But that’s irrelevant: the fact is that in this case it seems to me that D’Souza is correct: abortion entails the killing of children; and thus, calling abortion a human right entails the right to kill children.

There are three points at which I can envision a prochoice advocate disagreeing with this evaluation. I’ll address each one in turn.

Is it wrong to describe abortion as killing fetuses?

To begin with, one might object that it is problematic to use a verb like “kill” when one could use a more neutral term like “terminate.”

I demur. Some years ago I wrote the Conservative Government of Canada to complain about their defense of the slaughter of baby harp seals in Newfoundland. I received a curt reply that defended the government’s policy stance and which described the killing of the harp seals as a harvest. I replied that crops are harvested, seals are slaughtered. Consequently, the attempt to describe the mass killing of baby harp seals as if it were no different from a combine working a field of wheat was a disingenuous use of language to distort our moral evaluation of the act.

It seems to me that describing abortion as the termination of fetuses is the rhetorical equivalent of describing the baby harp seal slaughter as the harvest of seals. In other words, it is the use of misleading (neutral or positive) language to distort our moral evaluation of the act. So I believe it is more correct to describe abortion as what it is: killing.

Is it wrong to describe fetuses as children?

Okay, perhaps abortion is killing, but if it is, shouldn’t we describe it as the killing of fetuses? It is misleading and inappropriate to describe abortion as the killing of children.

I’m somewhat more sympathetic to this second objection. But here too I don’t think the objection succeeds for a very simple reason: when parents want the fetus they call it a child. Indeed, when dictionary.com defines the word “child” it includes “a human fetus” as one of the definitions.

Given that it is appropriate to refer to a fetus as a child, I believe it is likewise appropriate to refer to the killing of a fetus as the killing of a child.

Is it wrong to describe abortion as the killing of children simpliciter?

Finally, somebody might concede that abortion constitutes the killing of a child and still object that D’Souza’s description is inappropriate because it fails to note the restriction of the right to the killing of unborn children.

I don’t think this is a valid criticism either. Imagine that a human rights activist discovers that the imaginary country of Rondovia has given parents the right to kill children under five years old. In response, a human rights activist tweets “Rondovia gives parents the right to kill their children!” Would you object that the activist failed to specify that Rondovia had restricted the right to age four and under?

Perhaps you might. But I wouldn’t. And neither would I worry that D’Souza failed to note that the right to elective abortion is only the right to kill unborn children.

The post Elective abortion as the right to kill your children appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 24, 2017

Responding to Four Popular Arguments for Atheism

I recently did an interview with Catholic apologist and Pints with Aquinas podcaster Matt Fradd. In the interview we made our way through ten popular atheist arguments/declarations. Four of them are available in the most recent episode of Pints with Aquinas (the rest of the interview is limited to those who support the podcast through Patreon.) You can listen to the podcast at iTunes (episode 41) or by clicking on this link. Or you could just listen to it on YouTube:

The post Responding to Four Popular Arguments for Atheism appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 23, 2017

If it’s okay for God to allow horrors, then we don’t know much about God (Part 2)

This article is part 2 of a guest post by Dr. Jason Thibodeau. For part 1 click here.

This article is part 2 of a guest post by Dr. Jason Thibodeau. For part 1 click here.

Jason teaches at Cypress College and blogs at The Secular OutPost. You can also visit him online at “Not Not a Philosopher.”

III: Reply #1: We Know Enough

In his recent book, An Atheist and A Christian Walk into a Bar, co-written with Justin Schieber, Randal Rauser addresses some points that are similar to those that I have made here. While Randal was not addressing the argument that I just made, what he says in the book might be thought relevant to my argument and so I will consider what he says and whether it might serve as the basis of a reply to what I’ve said here.

In chapter 7, Schieber and Rauser consider the problem of evil. The relevant portion of their dialogue occurs toward the end of this chapter when Rauser says, “it is not nearly as surprising that God put us in a world of undeniably great suffering, since this is also a world tuned for soul-making.” (197). Schieber claims that this suggestion contradicts Rauser’s belief that God may have reasons of which we are unaware. Schieber says,

for any reason on which you speculate in order to excuse God’s poor fit with some horror in the world, there is always the fact that, for all we know, this reason is massively outweighed by unknown reasons (unknown to us but not to God) hiding below the surface that point in the exact opposite direction.

Appealing to unknowns helps nobody because they cancel each other out.

The lesson here I think is that, once we say that we’re not in a position to make judgment calls about the kinds of things God is likely to permit to occur on account of all the unknowns, we also rob ourselves of being in a position to make informed judgments that our favorite theodicy is not also outweighed by other reasons within that unknown-to-us section of God’s epistemic iceberg. (199)

Schieber’s point, if I understand it correctly, is that theism, once it incorporates the insights of skeptical theism, cannot make predictions about what God is likely to do or about what reasons God is likely to act on. Thus, skeptical theism is inconsistent with any attempt to state God’s reasons for allowing any particular evil.

It is important to see that Schieber is responding to Rauser’s claim that God permits at least some great suffering because doing so facilitates soul making. According to Schieber, such a suggestion is inconsistent with skeptical theism since the latter entails that, for all we know, God has strong reasons to not facilitate soul-making; indeed, it implies that God may have good reasons to promote the corruption of souls.

This is not my argument. I am not arguing that all attempts at characterizing the reasons that God would act on must fail. I agree with Rauser that, since God (if he exists) is morally perfect, we can know at least some of the goods that he will promote and thus the sorts of motivations that he will act on. In particular, I agree that, assuming he exists, we can be sure that, as Randal says, “God is maximally good and wise and that God always acts in a way consistent with the end of eventually achieving the maximum shalom or wellness for his creatures.” (201). But this gives us no grounds for believing that any of (1) – (4) are false.

Randal’s point is that it would be an error to suggest that, even given our epistemic limitations, we can know nothing about the kinds of things that are likely to motivate God. And I agree. We know enough about what God’s nature must be like to be certain that, all things being equal, he wouldn’t desire that our souls be destroyed or even that we are deceived. But Randal would be wrong to think that this tells us anything about how likely it is that God has reasons to permit our deception. If the maximum shalom of God’s creatures can be achieved only by permitting our vast deception, then God might indeed have reasons to permit us to be deceived. And, according to the skeptical theist, given our epistemic limitations, we are not in a position to know whether the maximum shalom of God’s creatures requires massive deception.

As the definition of skeptical theism states, part why our knowledge of the reasons available to God might be limited is that our knowledge of the goods that actually exist might be very limited. We must grant the possibility, then, that there exist creatures that are vastly superior to us in myriad ways, including but not limited to the following: the kinds of valuable states of which they can be subjects, the kinds of morally good action of which they are capable, and the kinds of morally valuable traits and characteristics which they are capable of developing. It may be that the well-being of such creatures involves the realization of goods the value of which is beyond our ability to comprehend. And we must acknowledge that it is possible that the total number of such creatures is vastly larger than the number of human beings that have ever lived. And it is possible that, for reasons we cannot understand, such unfathomable goods can only be achieved via the systematic deception of vast numbers of human beings about matters of vital importance.

But this fantasy story is absurd, I hear some protesting. I agree. I believe that it is highly implausible both that creatures of the sort I have described exist and, more importantly, that vast deception of humanity would be required for the well-being of such creatures. But I also think that it is highly unlikely that there are goods the realization of which requires that children suffer and die in hot cars, or the systematic extermination of tens of millions of people. But theists disagree with me. My point is that once we grant that it is possible for God to be justified in failing to prevent the kinds of horrors we observe, I don’t see how we could believe that God might not also be justified in allowing us to deceived about a great many things, including what God wants for us and expects of us. Further, I agree with Ivan and Alyosha Karamazov that if the torture and death of even one small child were necessary for the maximal well-being of God’s creatures, then it would not be worth it. But, again, theists disagree. Theists believe that the great horror that we see in this world is worth the great good that God is working to bring about. So, advocates of skeptical theism are in no position to claim that the scenario I described in the previous paragraph is an unrealistic fantasy that can have no epistemic significance.

It is possible that, due to some hidden string of connections, all the suffering that we observe in our world is necessary for the realization of great and unknown goods. But, then, it is also possible that, through some other equally hidden string of connections, some great unknown good requires that large numbers of people live and die under a vast illusion about very important things, such as the nature and possibility of human fulfillment and salvation. Nothing about the fact that God is dedicated to achieving the maximal shalom for his creatures implies such a string of hidden connections is impossible. And so, if we are skeptical theists, we cannot know that God would not be morally justified in allowing such vast deception.

IV: Reply #2: Tu Quoque

Rauser makes one other point in the book that might be thought relevant to my argument. In chapter 4, Rauser and Schieber consider whether it is possible that God might command something morally heinous, such as the torture or slaughter of an innocent child. About this possibility, Rauser says,

Sure it is logically possible that God could command something that appears to be morally heinous. But, for goodness sake, Justin, something parallel to that is true of every moral theory. Take your own theory predicated on moral desires. It’s logically possible that moral desires could require actions that appear to be morally heinous. Since you’re raising a point that applies trivially to every moral system, I fail to see what you hope to accomplish by pushing that particular issue on me. (122)

In this passage, Rauser is obviously not addressing the concerns that I have been raising here. Nonetheless, we could extrapolate his comments to develop a potentially interesting response to my argument. Here it is: Note that, as Rauser’s comment implies, any view about what is morally required or permissible must acknowledge the possibility that there are goods of which we are ignorant and which, once we factor them in, would show that, contrary to appearances, we are justified in permitting the occurrence of all kinds of horrible things (such as death, mass-starvation, and mass-deception). Since such conclusions apply universally, to any view about what we are morally required to do (including what a person is morally required to attempt to prevent), there is no special problem here for theism.

This reply does not work. While any normative theory must acknowledge that human knowledge is limited and that therefore it is possible for us to be wrong, perhaps massively wrong, about what is morally required of us, skeptical theism is committed to things that go beyond this claim about human limitations. Skeptical theism does not just say that it is possible that there are goods beyond our ken and unknown morally sufficient reasons that would justify God’s failure to prevent horrors. If skeptical theism is going to be a response to the problem that the existence of actual evil presents for theism, it is going to have to say not just that it is possible that there are such things, but that there actually are such unknown goods and reasons.

Further, it is not true that every normative theory is committed to claiming that it is possible that some unknown goods provide a morally sufficient reason for a person, who is in a position to help prevent some great evil, to refrain from doing so. This is true for some normative views, such as act utilitarianism, but it is not true of all normative theories. We could, for example, agree with Ivan Karamazov and assert that some evils are so great that even if they were necessary for the realization of incomparable goods (e.g., the well-being of the entire human race), we would still not be justified in refraining from trying to prevent these evils. And we can assert that some actual evils, the Holocaust for example, satisfy this description.

Indeed, Rauser himself is committed to a very similar view. In the context of the discussion I’ve mentioned above, he says, “I believe there are all sorts of actions that I could never have a moral obligation or moral calling to perform . . . Since I believe those actions are necessarily immoral, it follows that I could never have a moral obligation to torture or rape another person.” (124).

We could similarly believe that there are some actual horrors that a properly situated person could never be morally permitted to refrain from trying to prevent. A skeptical theist cannot believe this. Skeptical theists must believe that God is morally permitted to refrain from preventing all of the horrors I have mentioned in this essay.

There are two parts of my response to the potential reply that we’ve been considering in this section. The first is that there is an important difference between on the one hand acknowledging the bare possibility that there exist morally sufficient reasons that would entail that, in at least some instances, our considered normative judgments are wildly wrong, and, on the other hand, asserting that there are morally sufficient reasons for a person who is situated so as to prevent a great horror to refrain from doing so. The former possibility need not force us to reassess any of our normative judgments. The existence of the latter must make us reassess the probability that other morally sufficient reasons might exist that would justify God’s allowing humanity to be systematically deceived about significant issues.

The second part of my response is that not all moral views are in the same boat. Any moral view according to which some person, who is situated so as to prevent it, is at least on some occasion morally permitted to refrain from preventing something as horrible as the Holocaust is going to have to accept that we could be wildly wrong about our duties to prevent horrible suffering. But some moral views will not have this implication. On some moral views, just as some acts are intrinsically wrong and thus it is never morally permissible for any person to engage in them, so too there may be some events that are so horrendous that no person who is situated so as to prevent them could ever be justified in failing to attempt to prevent them.

I don’t think that we are in a position to claim that we know with absolute certainty that there are no morally sufficient reasons that would justify an omnipotent person’s refraining from trying to prevent some horror that the person is in a position to prevent. However, I would assert that we can be confident that it is highly implausible that there are such reasons. Skeptical theists, however, cannot say this. They must assert not only that it is not highly implausible that there are such reasons, but that such reason most assuredly do exist. If we have good grounds for thinking that the existence of such reasons is highly implausible, then we can reasonably be dismissive of the skeptical consequences that the existence of such reasons entail. However, if, as skeptical theists believe, we have no grounds for believing that it is highly implausible that such reasons exist and, on the contrary, we have good reason to think that there are such reasons, then we cannot reasonably be dismissive of the skeptical consequences that such epistemic limitations entail. Since Rauser embraces skeptical theism, he must admit that he cannot reasonably dismiss the skeptical consequences that I have described. Thus, he is committed to (1) – (4) and, further, he is committed to claiming that we cannot know what God wants of us or expects of us.

The post If it’s okay for God to allow horrors, then we don’t know much about God (Part 2) appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 22, 2017

If it’s okay for God to allow horrors, then we don’t know much about God (Part 1)

This article is part 1 of a guest post by Dr. Jason Thibodeau. Jason teaches at Cypress College and blogs at The Secular OutPost. You can also visit him online at “Not Not a Philosopher.”

This article is part 1 of a guest post by Dr. Jason Thibodeau. Jason teaches at Cypress College and blogs at The Secular OutPost. You can also visit him online at “Not Not a Philosopher.”

I: The Problem of Evil

Every year in the United States an average of 37 children die after being left in a hot car by their parents. We can assume that, in most of these instances, there was no passerby who was in a position to help get the child out of the car. If ever there was such a passerby and this person did nothing to help, most of us would agree that the person would have acted wrongly. Given that such events occur, we also know that God does nothing to prevent them. The problem of evil is the problem of accounting for why God refrains from preventing such horrible events.

Let me say a bit more about what it means to say that a person is in a position to help:

Person P is in a position to help prevent some event, E, just in case (a) P is aware that E is occurring or will occur, (b) P has at least those capacities the exercise of which stands a reasonable chance of being sufficient to stop E’s occurring, and (c) there is no action or course of action A such that, (i) P should do A; (ii) by doing A, P will be unable to stop E from occurring; and (iii) P’s failure to do A either is or will result in something equally bad or worse than E.

I will say that a person who satisfies at least (a) and (b) is situated so as to prevent E.

When we think about the obligations we have to help prevent horrible events, we should assert

(M) If a person, P, is in a position to prevent some bad event E and P does nothing to prevent E, then P has acted wrongly.

and

(L) If a person P is situated so as to prevent some bad event E, then the only morally sufficient reason for P to fail to prevent E is that, for P, there is some act that satisfies (i), (ii), and (iii).

(L) captures the intuition that the only good reasons for failing to prevent something bad from happening are that you didn’t know that it was going to happen, didn’t have the ability to prevent it, or else had obligations that conflicted with your acting to prevent it.

We know that there are countless bad events that God fails to prevent. If God exists, then he is morally perfect and so we also know that the consequent of (M) can never be true of God. For any evil event, God is always situated so as to prevent it. Thus, given (L), the only morally sufficient reason for God to refrain from preventing some evil is that there is an act or course of action that satisfies (i), (ii), and (iii). That is, If God exists, then for all actual instances of evil that occur, it must be the case that there is some act such that (i) God should do it, (ii) by doing it, God will be unable to stop the evil from occurring, and (iii) God’s failure to do it either is or will result in something equally bad or worse than the evil that actually occurs. Further, since God is omnipotent, “God will be unable to” in (iii) must mean “it is not logically possible for God to.”

It is reasonable to observe that, given everything I said in the last paragraph, it is very difficult for us to think of reasons for God to fail to prevent the suffering and death of a child in a hot car, not to mention all of the other evils that people have witnessed over the course of human existence. If you disagree with this assessment, perhaps you can stop reading now and offer your favorite examples of such reasons in the comment section down below.

These horrible deaths are just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to instances of evil that God does not prevent. Every year in the US approximately 15,000 children are diagnosed with cancer, most of them undergo treatment that involves significant pain and suffering, 12% do not survive. In 2015 nearly 800 million people across the globe were malnourished. Tens of thousands of people die every day from hunger and malnutrition. Between 6 and 11 million people were brutally murdered during the Holocaust, most of them after suffering for months or years from emotional distress, fear, malnourishment, and incomparable mistreatment. While exact figures are difficult to calculate, the best estimates say that around 230,000 people died in the tsunami that struck the Indian Ocean on Boxing Day in 2004. The Black Death killed 40-50% of the population of Europe during a four-year period in the middle of the fourteenth century; in total, this plague killed between 75 million and 200 million people across Eurasia. The list of horrors goes on.

If you think that we can partially account for God’s failure to prevent some of this senseless devastation by pointing out that God rightfully desires his creatures to possess and exercise free will, consider the following: There is no credible view according to which respect for free will entails that it is always wrong to interfere so as to prevent the effects that a person freely tries to bring about. That Hitler was exercising his free will when he chose to pursue the Final Solution does not entail that any person, God included, is morally justified in refraining from doing whatever they can to prevent the genocide of European Jews. Imagine if FDR or Winston Churchill had said, “I’d like to prevent the Nazis from dominating Europe and committing mass genocide, but the problem is that, if we went to war, we would be undermining Hitler’s freedom. Given the value of free will, we better just sit back and let the Nazis have their way.” Respecting free will does not mean that, once a person has freely decided, we must sit back and allow his plans to come to fruition. Given the unimaginable horror of the Holocaust, we must look elsewhere for God’s reasons for failing to prevent it.

Nor should we think that some version of a soul-making theodicy can fully explain God’s reasons for failing to prevent the horrors I’ve described. Again, imagine that, in 1939, Winston Churchill had said the following: “While it is true that the devastation, suffering, and death that the Nazis are likely to inflict on the European people is incomparably worse than anything we’ve seen before, we must remember that such horrors will provide the victims of the Nazi campaign with opportunities for character development that would not otherwise have presented themselves.”

While it is true that God is in a superior epistemic position to Winston Churchill, this is irrelevant to whether the value of soul-making can justify a decision to refrain from intervening to put an end to the Nazi regime. The point is that the value of soul-making is not worth the devastation brought about by the Nazis. People would have had plenty of opportunities for character development even if Hitler had never come to power and the Holocaust had never happened (because, e.g., God prevented it). Again, we must look elsewhere if we are to account for God’s decision to not prevent the Holocaust.

I do not have the time or space to consider every possible reason someone might think of to account for God’s failure to prevent such horror. Nor would such a task be particularly enlightening. If we are not already convinced that it is exceedingly difficult to understand why God would allow such evil to occur, there is very little room for productive conversation. Instead, I want to consider a different issue. Many people, both atheists and theists, who have thought carefully about the problem of evil have concluded that we cannot come up with a complete and compelling account of the reasons that God has for not preventing the kinds of horrors I have described. I want to talk about some of the consequences of this conclusion.

II: Skeptical Theism and its Consequences

If we cannot think of good reasons for why God would be justified in allowing such horrors to occur, we might be inclined to say something like the following:

Skeptical Theism: Given our inferior epistemic abilities as compared to an omniscient being such as God, it would not be surprising if there are reasons of which we are unaware that would provide God with morally sufficient grounds for permitting such horrors, perhaps even reasons that we are incapable of being aware of. For all we know there are goods that are beyond our ken the promotion or preservation of which justify God’s failing to intervene to prevent horrible events.

I think that we should be very skeptical of the possibility that such morally sufficient reasons exist. As I have argued elsewhere, given the myriad opportunities that an omnipotent being has for realizing goods, it is highly implausible to believe that there are any goods that an omnipotent being cannot realize without necessitating the occurrence of horrendous suffering (such as the suffering and death of small children accidentally left in hot cars). However, in this essay I do not want to explore how likely it is that there exist some good(s) that God cannot realize while simultaneously causing a car window to break. Instead, I want to draw our attention to some significant skeptical conclusions that we will commit ourselves to if we believe that God has morally sufficient reasons to fail to prevent the kinds of horrors I have discussed.

If we believe that God has morally sufficient reasons to fail to prevent horrible events of the kind I have mentioned above, then we must also believe

(1) It is possible that there are morally sufficient reasons that justify God’s wanting some human being to kill several other human beings in the most agonizing way possible.

(2) It is possible that there are morally sufficient reasons that justify God’s inspiring human beings to write a book that is full of falsehoods about human salvation, but which will be widely accepted as divinely inspired.

(3) It is possible that there are morally sufficient reasons that justify God’s causing (or permitting some other being(s) to cause) many humans to falsely believe that Jesus of Nazareth died on the cross for the forgiveness of sins.

Some might respond to (2) and (3) by suggesting that God could never have morally sufficient reasons to lie. But this response ignores the fact that our moral reasons often conflict. Even if we suppose that God has very strong moral reasons to not lie, these reasons are only prima facie reasons. It is possible for God to occasionally be in a situation in which these prima facie reasons are overwhelmed by stronger moral reasons that point in the opposite direction. That one has a prima facie obligation to do X does not mean that one is always wrong to do X because there might be occasions in which, all things considered, one is obligated do what it is prima facie wrong to do. Even though lying is frequently wrong, most of us will agree that there are occasions in which lying is morally justifiable. Such occasions typically involve some significantly valuable end that can only be promoted via a lie. When the Nazis knock on your door and ask whether you are harboring Jews in your home, you ought to tell them that you are not doing so regardless of what the truth is. This is because your prima facie obligation to tell the truth is overcome by another, stronger obligation: the obligation to protect innocent lives. And so, all things considered, if you are protecting people from the Nazis, you ought to lie.

Thus, we cannot use the fact that God has a strong prima facie obligation to tell us the truth as a reason to think that (2) and (3) are not true. If skeptical theism is true, for all we know, there are ends that God cannot achieve except through some course of action that involves intentionally deceiving us about very important matters. And for all we know, these ends are so significant that, like the end of preserving the lives of the Jewish family hiding from the Nazis, promoting them would justify lying.

Further, even if we thought that it is impossible that God has morally sufficient reasons to deceive us, it would not follow that it is impossible that God has morally sufficient reasons to allow us to be deceived.

If skeptical theism is true, we must also believe

(4) It is possible that there are morally sufficient reasons that justify God’s being completely unresponsive to our physical, emotional, and spiritual needs, including our need to achieve salvation or any other soteriological end.

The problem is that most theists, including Christians, will deny that (2), (3), and (4) are true. The question is how such theists can be sure that God has morally sufficient reasons to fail to prevent great evils and also insist that God cannot have morally sufficient reasons to deceive us or allow us to be deceived about very important things (like our own salvation) or to be unresponsive to our most significant needs.

Given the assumption that God has morally sufficient reasons to fail to prevent the deaths of children in hot cars (and the many other horrors that we observe), what we should say is that we are not in a position to judge how likely it is that God has reasons to deceive us or allow us to be deceived about the Bible, the significance of Jesus, our own greatest good, and many other things. But, of course, most theists are not so humble when they speak about what God can do for us and the interest God has in our greatest good, nor can Christians admit that, for all we know, Jesus did not die for our sins.

What Christians ought to say, if they are skeptical theists, is that for all we know, God has very good reasons to allow us to believe that Jesus died for our sins even though he did not die for our sins. About these and many other very important matters, we could be gravely mistaken. We are just not in a position to know whether God has morally sufficient reasons to allow us to be so deceived. This implies, for example, that even if we had very good evidence that Jesus was resurrected from the dead, we would still not be in a position to know that Jesus died for our sins.

It is important to note that skeptical theists are committed to a much broader religious skepticism than is represented in (1) – (4). Given that it is possible that there are reasons for God to refrain from preventing horrors, it is also possible that God has reasons to allow us to be deceived about everything we might believe about God, what God wants of us, and our greatest good. This is the consequence of skeptical theism that I am drawing our attention to: skeptical theism implies a far-ranging skepticism about theological and religious matters.

The post If it’s okay for God to allow horrors, then we don’t know much about God (Part 1) appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 21, 2017

The Ethical Principle Behind #NotMyPresident

Image source: http://s3.amazonaws.com/posttv-thumbn...

Over the last several weeks we’ve all encountered the hashtag #NotMyPresident along with the accompanying sentiment. The response has been predictable: Trump was elected by the electoral college, so he is president. And if you’re American, he’s your president, period.

Yesterday conservative Christian radio host Michael Brown issued his own indictment of the #NotMyPresident crowd. In Brown’s view, folks need to “Get over it” because Trump is their president:

To the Trump haters. I had massive issues with Obama as POTUS but he was still my president. Now Trump is yours. Get over it.

— Dr. Michael L. Brown (@DrMichaelLBrown) January 21, 2017

Let’s start off by distinguishing two senses in which the question can be discussed: we can call these the procedural question and the ethical question. The procedural question is the question of whether Trump won the electoral college. The ethical question is the question of whether, irrespective of whether Trump won the electoral college, he is a leader to whom one can submit in good conscience. And I would submit that the latter question is far more important than the former. It’s also the question I’m concerned with here.

So how can a person decide whether they can, in good conscience, recognize the POTUS as their president? The starting point is an honest evaluation of the individual’s character and conduct. In my interaction with Brown, I decided to address one question: the outstanding charges of sexual assault:

@DrMichaelLBrown Let's consider one of many issues: there are 12 outstanding charges of sexual assault against Trump. "Get over it"? Really?

— Randal Rauser (@RandalRauser) January 21, 2017

Unfortunately, I’ve seen many Trump supporters point out that Trump has not been found guilty of sexual assault in a court of law. But that is irrelevant. One does not need to await a criminal or civil judgment in a court of law to form an opinion on the credibility of charges.

Imagine, for the moment, that your son’s little league coach is accused of sexually assaulting twelve young boys from the league. Imagine, as well, that the man has a history of making suggestive and inappropriate comments about young boys. Imagine that the man could continue to coach until he was found guilty in a court of law. Would you keep your son on the team for the duration of the trial? The very notion is absurd. The fact is that we don’t need to await a court judgment to form our opinions about the man’s guilt.

By the same token, one does not need to remain agnostic on charges that Trump sexually assaulted women until there is a judgment in a civil or criminal proceeding.

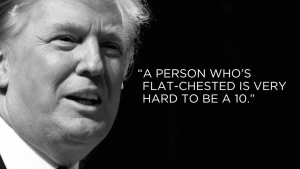

So what does the evidence suggest? A history of misogynistic comments judging women by their physical appearance; sexualizing his own daughter as a “piece of ass”; sexualizing his other daughter when she was an infant by admiring her legs and speculating on her future cleavage; multiple witnesses stating that Trump would enter the change rooms at beauty pageants (including those with minors) in the hope of seeing female contestants in various stages of undress; his own bragging that he grabs women by their genitals; and the testimony of twelve witnesses, many with corroborating testimony from friends and family.

On the other side of the ledger you have Trump’s insistence that he didn’t do it. You also have his promise that after the election he would sue his twelve accusers, a promise that he has now broken. However, last week one of his accusers filed a lawsuit against him for defamation.

Based on that evidence, it seems to me that the most reasonable conclusion is that Donald Trump is an unrepentant misogynist sexual predator. And I, for one, could never ethically recognize an unrepentant misogynistic sexual predator as my president, irrespective of the answer to the procedural question.

For a full account of my exchange with Michael Brown you can follow this link to read our exchange. There you will see that Brown’s only response to the evidence I listed above is the third-hand testimony that Trump has evidence undermining his 12 accusers. I’ll leave it to you to judge whether that third-hand testimony is sufficient to outweigh the evidence I listed above.

The post The Ethical Principle Behind #NotMyPresident appeared first on Randal Rauser.