Chris Gavaler's Blog, page 57

October 19, 2015

Super Cowboy in the White House

Here’s the debate question we should ask Clinton, Trump, Sanders, and the herd of Republicans running for President:

“What art would you hang in the Oval Office?”

It sounds frivolous, but the answers reveal a lot about our last two presidents.

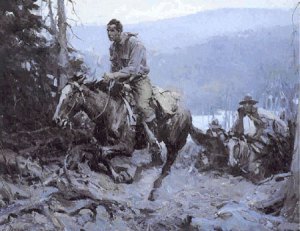

When George W. Bush moved from the Texas governor’s office to the Oval Office in 2001, he brought his favorite painting, a 28 x 40 oil by Westerns illustrator W.H.D. Koerner which appeared on the back of his campaign biography, A Charge to Keep. The title is from a hymn, and a friend gave him the painting because it illustrated a 1918 short story of the same name. Bush believed the figure in the painting, a cowboy charging up a hill on horseback, was a 19th century Methodist evangelist spreading his faith across the West.

“He’s a determined horseman,” the President told visitors, “a very difficult trail. And you know at least two people are following him, and maybe a thousand.”

“Bush’s personal identification with the painting,” writes David Gergen, “reveals a good deal about his sense of himself . . . . a brave, daring leader riding fearlessly into the unknown, striking out against unseen enemies, pulling his team behind him, seeking, in the words of Wesley’s hymn, ‘to do my Master’s will.’”

Although the painting did appear beside Ben Ames Williams’ “A Charge to Keep” in Country Gentleman Magazine, Koerner painted it three years earlier for The Saturday Evening Post to illustrate a story by William J. Neidig called “The Slipper Tongue.”

The horseman is a horse-thief fleeing a lynch mob.

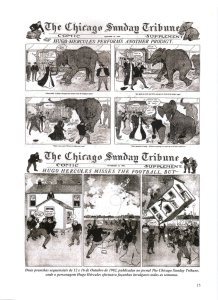

But whatever its title, the work has become the best known of Koerner’s over 800 commissioned paintings and drawings, including “Hugo Hercules,” the original comic strip superhero.

Koerner immigrated from Germany at the age of three, and seventeen years later got a job as a staff artist for the Chicago Tribune for $5 a day. His duties included producing a Sunday strip for the Comics Supplement. He came up with an urban cowboy with super-strength. If that’s not enough to call him a superhero, Hugo calls himself “the boy wonder” while aiding a series of Chicago damsels-in-mild-distress.

He has his own catch phrase too, “Just as easy,” tossed off whenever he performs some inhuman feat, like ice skating with a boat on his shoulders or flinging a defensive line of football players across a goal post. Sometimes he adds, “I could do this forever,” as if Koerner has hasn’t drawn him in a sufficiently effortless pose. Clark Kent wouldn’t declare, “This is a job for . . . Superman!”for almost four decades, but Hugo knows when “It’s up to me!”

Oval Office visitors commented how Koerner’s Methodist horse-thief looked a bit like George W., but Hugo was the one with the cowboy hat—offset by a sports jacket, stripped pants and bowtie. The hat vacillated between white and black though, and Hugo vacillated too. Overall he was a force for good, but his altruism was random and occasionally the good he did was correcting the harm he’d done—like when he missed a football and accidentally punted a house across a field. But at least he lugged it back, right? And so what if he uses his strength to collect the bowling competition prize money after destroying a wall and passing trolley in the process? After catching a falling safe from crushing an old man as his daughter helplessly watched, he asks: “Am I glad I did it? Wid de doll’s arms around me neck and de old gent coffing a three spot? Am I glad?”

Note that folksy way of talking too. No wonder George W. liked Koerner. And if Hugo can be a bit destructive—did he really have to rip up a porch to carry it umbrella-like over a woman worried about the rain?—he helps far more than he harms, like when he catches that family jumping from a burning house, or when he carries a fire engine to another would-be disaster. He stops that runaway horse before it crashes its owner’s carriage, but more often he only saves damsels from mild inconvenience, halting trolleys and cable cars that refuse to stop, or lifting an elephant standing on a handkerchief. And how did the striking cab-driver’s union feel when carried that woman and her pile of crates? Dragging a derailed train twenty miles is nice, but is lifting a young Romeo and his car to his Juliet’s balcony for a parting kiss really the best use of one’s superpowers? As far as actual menaces, hugo does wrestle a bear into submission—though he was only saving himself. Same with those three muggers who corner him at gunpoint. They look ready to abandon the criminal life after he points a canon in their faces.

Would their bullets have bounced off him? Could he have leapt tall buildings if they’d tried to escape? No idea. We’ll never know how Hugo might have matured into his yet-to-be-named genre. The strip only ran from September 1902 to January before Koerner abandoned it for better work. Soon he was studying with famed illustrator Howard Pyle, creator of the 1883 classic The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood, as well as varied adventures of Arthurian knights, noble pirates, and a modern Aladdin. It was a thorough education in proto-superheroes, but Koerner’s interests turned west when The Saturday Evening Post commissioned his first two frontier scenes instead. He never returned. When he died at the age of 58, he was one of the best known artists of the Old West. That was 1938, the year Action Comics No. 1 rode onto newsstands.

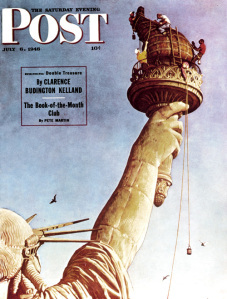

When the Bushes returned to Texas, they took their so-called “A Charge to Keep” with them. The Obamas, fresh from Koerner’s hometown of Chicago, replaced his galloping horse-thief with a more traditional Saturday Evening Post illustration, Norman Rockwell’s “Working on the Statue of Liberty.” At 24 x14, it’s less than half the size of Koerner’s work. It depicts four tiny workmen scaling the torch to clean its amber glass. It’s slow, dangerous work—something Hugo Hercules could have finished in three panels.

The Obama Oval Office, however, is not cowboy-free. Frederic Remington’s sculpture “The Bronco Buster” still sits on its side table, and the President not only kept but expanded his predecessor’s spy programs, herding up emails across the frontier of the World Wide Web. When German Chancellor Angela Merkel found out the NSA was following their Master’s will and bugging her phone, her government threatened the diplomatic equivalent of a lynch mob–counterespionage. “They’re like cowboys,” explained a party member, “who only understand the language of the Wild West.”

What language will our next President understand?

October 12, 2015

The First Superhero?

I’ve been assembling an ur-team of Avengers for my book On the Origin of Superheroes, and my first-ever superhero award goes to the Golem. He’s super-strong, impervious to pain, and, when made from clay, can even shapeshift a bit. On the downside, he’s dumb in both senses and so requires close supervision. Sorcerers and programmers beware.

“There is nothing more uncanny than something that is almost human,” says Margaret Atwood. “All our stories about robotics are stories like that. It’s what we have always worried about. It’s the sorcerer’s apprentice story: He learns how to do the charm; he doesn’t know how to turn it off. It’s the Golem story: You make the Golem, you activate it, it’s supposed to do your work for you, and then it runs amok.”

Atwood’s Oryx and Crake trilogy features a genetically engineered species of designer humans, but they’re too mellow to cause the survivors of her apocalypse much trouble. When it comes to magic brooms and water buckets running amok, I picture Mickey Mouse, but Goethe published his poem “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” while Napoleon was still waging France’s Revolutionary Wars.

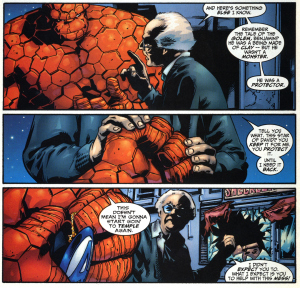

Apparently Goethe cribbed the tale from Lucian’s Philopseudes, c. 150 CE, though the word “golem” is even older. It means “shapeless mass” in Hebrew, which is the description of Ben Grimm that Stan Lee typed up for Jack Kirby in 1960: “He’s sort of shapeless—he’s become a THING.” Kirby drew a giant bumpy rock monster that turned orange at the printer’s. I don’t know if either had the Golem in mind, but Fantastic Four writer Karl Kesel did when he decided forty years later that Ben’s full name was Benjamin Jacob Grimm.

Benjamin grew up going to synagogue as a kid and could still recite Torah passages from memory, so he probably knows that “golem” first appears in Psalms 139:16 (“my substance, yet being unperfect”) when David praises God for creating him. The Talmud (c. 200 CE) uses the term to describe Adam’s creation too: “In the first hour, his dust was gathered; in the second, it was kneaded into a shapeless mass.” But jump forward another couple hundred years, and a passage mentions the first living golem: “Rabbah created a man, and sent him to Rabbi Zera. Rabbi Zera spoke to him, but received no answer. Thereupon he said unto him: ‘Thou art a creature of the magicians. Return to thy dust.’”

Apparently they weren’t all that hard to manufacture. All Pygmalion had to do was pray to Venus to bring his ivory statue Galatea to life. Daedalus soldered his golem Talos from bronze. If you’re up on your Kabbalistic techniques, Sefer Yetzirah (The Book of Formation) gives a how-to, but Aryeh Kaplan warns apprentices not to attempt it alone. Virgin dirt is also key. Marvel was still printing on pulp paper in 1974, which is why their Strange Tales Golem only ran three issues. Writer Len Wein gave the legend his best superheroic spin:

“In centuries agon, they had called him a myth, a creature formed of stone and clay and the blood of a people’s oppression—a moving monolith who rose before the yoke of tyranny—shattered it in his monumental fists—then vanished into the sands of time—there to be almost forgotten—until today! Now once more he rises—summoned from his eons-long sleep to protect those he loves.”

Marvel tries not to take sides in the Palestine-Israeli conflict, declaring it

“a war of territory, of ideologies—fought with great fervor but with little gain—fought with loaned weaponry wielded by men—men charged with love of country and the courage of their convictions, but men nonetheless—aye, as in all wars before this, fought by men—imperfect, all-too-human men.”

But those the Golem loves are the family of Jewish archeologists who dig him up, while General Omar leads an army of marauding rapists who pillage the archeological camp and machinegun the grandfather. Uncle Abraham’s dying tear reanimates the creature. “Eyes of a camel!” shouts one of the keffiyeh-wearing soldiers. “The statue—it lives!”

Michael Chabon’s golem surfaces for far less dramatic adventures. His amazing Kavalier and Clay find its coffin filled

“to a depth of about seven inches, with a fine powder, pigeon-gray and opalescent, that Joe recognized at once from boyhood excursions as the silty bed of the Moldau . . . . The speculations of those who feared that the Golem, removed from the shores of the river that mothered it, might degrade had been proved correct.”

My wife and I sat along the banks of the Moldau (AKA Vltava) sipping Budvar in a Prague café in 1996. The ground was too paved to be termed virginal, but the city has a legion of statues and tourist shop figurines already prepped for animation. Prague is to Golem as Metropolis is to Superman. The tales proliferated there like magic brooms in the 1800s. One named Josef protected Jews from a supervillainous Emperor with the additional superpower of invisibility—so basically half of the Fantastic Four. Benjamin Kuras, author of As Golems Go, explains why Golem still adventures in the Czech Republic:

“After living through the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Nazism and decades of communism, the Czechs are drawn to a character with supernatural powers that will help liberate them from oppression.”

The Golem is also the original “robot,” a Czech word for “laborer” or “slave.” Karel Čapek’s play R.U.R. (AKA “Rossum’s Universal Robots”) unleashed them on the world, resulting in the extinction of the human race in 1920. Despite the nuts-and-bolts contraptions in promo shots, Čapek’s robots are the flesh-and-blood variety, more like clones or Philip Dick’s sheep-dreaming replicants. Carl Burgos had the same idea when he drew the Human Torch for Marvel Comics No. 1 in 1939. The flames were one of those unintended “run amok” side effects, but rather than burning Brooklyn to the ground, the almost human Torch gets his superpower under control (bringing our Fantastic Four tally to 75%) and vows to help humanity even though humanity tried to seal him in a steel and concrete cage.

The Human Torch fizzled in the forties and wandered out to the desert to die—the same fate Wein copied for his Golem. The evil robot Ultron rebuilt the Torch’s burnt-out corpse in 1968, and he was reborn as my favorite childhood superhero, the Vision. But then the original Torch erupted from a secret grave in the 80s, so the Vision was never really the Torch but a copy soldered from spare parts. Only, no wait, that’s not it either, because next it turns out the Vision and the Torch are in fact the same synthoid split in two when a time-traveling supervillain manipulated the timeline. Except then the Vision half was ripped apart by She-Hulk, and his identity may or may not inhabit the sentient armor of the time-traveler’s teen-age self, while his soul returned in a team of Dead Avengers before Tony Stark reassembled his body. And don’t even get me started whether that body is the kind with buzzing wires and clanking pistons or the kind with synthetic organs that gurgle and fart.

Human animation is simpler. My wife returned from Prague pregnant with our daughter. King David praises God for “cover[ing] me in my mother’s womb,” but we followed a very different nuts and bolts process. Though nothing like the Thing, my daughter has been running amok for eighteen years now. She looks a lot more like the clay statue Hippolyte sculpted and, with the help of her gods William Marston and Harry G. Peter, brought to life in 1941—making Wonder Woman the original comic book Golem. Sadly, she’s not available for my team of First Avengers.

October 5, 2015

Henry James Inked Me

After reading The Time Machine in 1900, Henry James wrote to H. G. Wells: “You are very magnificent. . . . I rewrite you much, as I read—which is the highest praise my damned impertinence can pay to an author.” It’s a strange compliment, and he expanded it two years later: “my sole and single way of perusing the fiction of Another is to write it over—even when most immortal—as I go. Write it over, I mean, re-compose it, in the light of my own high sense of propriety and with immense refinements and embellishments. . . to take it over and make the best of it.”

James’s damned impertinence turned his highest praise into an actual invitation to collaborate with Wells on a science fiction novel: “Our mixture would, I think, be effective. I hope you are thinking of doing Mars—in some detail. Let me in there, at the right moment—or in other words at an early stage . . . .” The two authors shared a literary agent, James B. Pinker, and James wanted to take over and make the best of a Wells manuscript before Pinker saw it: “to secure an ideal collaboration . . . I should be put in possession of your work in its . . . pre-Pinkerite state. Then I should take it up and give it the benefit of my vision. After which, as post-Pinkerite—it would have nothing in common with the suggestive sheets received by me, and yet we should have labored in sweet unison.” He ends his letter “your faithful finisher.”

This is a bizarre request. Give me your rough draft to rework however I wish. Wells declined. Of course Wells declined. But first he tested whether the offer was one-sided, asking to peruse the notes to James’ next novel, The Ambassadors. Although James had a “carefully typed” 20,000-word prospectus, he did not share it with Wells. “A plan for myself, as copious and developed as possible, I always draw up,” he explained, but “such a preliminary private outpouring . . . isn’t a thing I would willingly expose to an eye but my own.” And he wouldn’t expose it to another’s over-writing hand either. He was his own finisher.

James’s notion of an “ideal collaboration” is laughably outside the norms of literary authorship, but it also reveals the damned impertinence of comic book production norms. Pencillers hand over “suggestive sheets” to inkers, or “finishers,” who literally draw over them, refining and embellishing according to their own sense of propriety. That includes erasing. It may be some lowly office helper—Stan Lee in his earliest days—holding the eraser, but it’s the inker who decides what stays and what goes. James’s final pages “would have nothing in common” with Wells’ erased and overwritten rough draft. And yet the plot, the chapter structure, the scene-by-scene movement—what comic book creator would call the layouts and breakdowns—they would still be Wells’. Reworking a sentence—adding flourishes, curving the grammar for new stylistic effects, while preserving and augmenting some paraphrasable meaning—that’s an inker’s job.

Four years later, after reading Wells’ The Future of America, James wrote again, revealing his inking style: “you tend always to simplify overmuch . . . But what am I talking about, when just this ability and impulse to simply—so vividly—is just what I all yearningly envy you?—I who was accursedly born to touch nothing save to complicate it.”

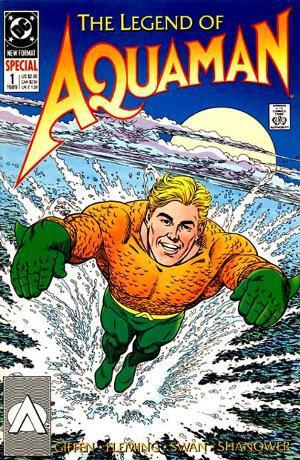

James would have added complexity to Wells’ overly simplified language—how Eric Shanower inked Curt Swan’s pencils for The Legend of Aquaman.

Swan was nearing the end of his career in 1989, but according to Mark Waid (via Eddy Zeno’s Curt Swan: A Life in Comics) Swan considered the special issues a personal high point. The face, the anatomy, the foreshortened movement, those are recognizably Swan, but look at the background, the clouds, the meticulously scalloped waves, that’s Shanower, an artist renown for his details. His Age of Bronze is almost calligraphic in its precision, each scallop of chain mail a painstaking wonder.

Would Wells have benefited from such a finish by James? Probably. But Swan wasn’t always grateful for Shanower’s efforts. During a visit to my campus, Shanower told a table of professors how he would erase Swan’s background buildings in order to correct all the perspectives errors. Swan didn’t thank him. He thought Shanower was wasting his time, but, like Wells in James’ “ideal collaboration,” his opinions were irrelevant once the sheets were in Shanower’s hands.

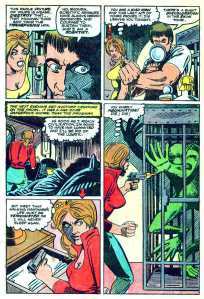

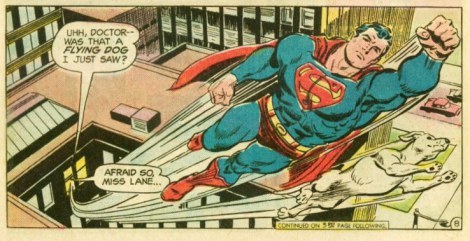

Compare Shanower’s chain mail and seas scallops to the inked versions of Swan by other artists, and you’ll see what Swan considered an appropriate attention to detail. Bob Hughes at Who Drew Superman? credits Swan for dominating Superman during that other Bronze Age while collaborating with a dozen different artists. Bob Oksner inked Superman No. 287 in 1975:

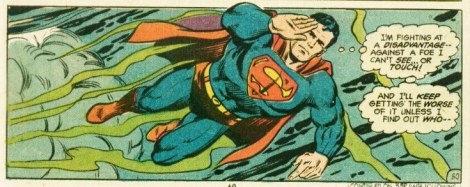

Vince Colletta inked Superman Spectacular in 1977:

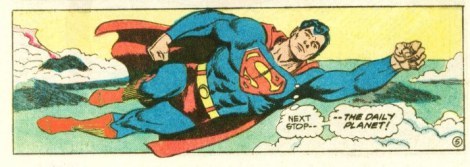

And Al Williamson inked Superman No. 410 in 1985:

Look at the full-page layouts, and you’ll also see Swan’s signature breakdown: the top 2/3rds divided into 4-5 panels, anchored by a bottom rectangle featuring Superman flying toward the right margin:

The Swan-Oksner background buildings look pretty detailed to my eye–though some of those perspective lines might be a tad wonky beyond Superman’s right shoulder. The Swan-Colletta and Swan-Williamson backgrounds are comparatively sparse. In fact, sparseness was Vince Colletta’s signature “style.” Though his best work is revered for its own Shanower-esque precision, other artists dislike his high sense of propriety.

Editor kept Colletta employed because he got his work in on time, but pencillers, like Wells, avoided the sweet unison of collaboration. Joe Sinnott (who also inked plenty of Jack Kirby’s Fantastic Four pages) said Colletta “wrecked” his romance stories because Colletta “would eliminate people from the strip and use silhouettes, everything to cut corners and make the work easier for himself.” Marvel writer Len Wein agreed that Colletta “ruined” art, and Steve Ditko and later Kirby refused to work with him.

Ditko, like Wells, preferred to ink himself. PencilInk documents a range of examples (Amazing Spider-man No. 3, 1963; Monster Hunters No. 8, 1976; Iron Man Annual No. 11, 1990):

But sometimes even Ditko would have to willingly expose his preliminary outpourings for the benefit of another artist’s vision. Wayne Howard, for example, inked House of Mystery No. 247 in 1976:

And Dan Adkins inked Superboy No. 257 in 1979:

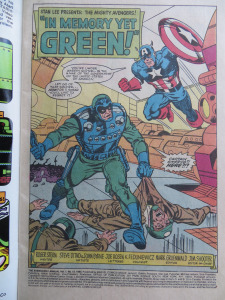

But the most discordant of Ditko’s finishers was John Byrne. As an artist used to getting top-billing as both writer and penciller, he, like James, took possession of Ditko’s pages, applying his own immense refinements and embellishments. Look at Avengers Annual No. 13 from 1984:

The thug’s left foot–only Ditko would draw the impossibly upturned sole. But that’s a Byrne mouth on Captain America, the musculature too. When Mr. Fantastic appears, he seems to have beamed in from Byrne’s Fantastic Four run, but that’s a glaringly Ditko-esque face grinning open-mouthed beside him:

The mixture of the two is even stranger:

Is this what a Wells-James collaboration looks like? James would have placed his name first–though only because cutting Wells from the credit box entirely wouldn’t be an option too. That’s what Alexander Dumas did with his collaborators. Auguste Maquet co-authored both The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers, but it’s only Dumas on the covers because Maquet was his employee, what Marvel calls “work for hire.” Maquet produced rough drafts for his boss to write-over. He later sued for co-credit, but the French courts ruled in favor of Dumas.

In comics, the prestige position is reversed. Swan and Kirby had so many inkers because their editors wanted them pencilling as many titles as possible. At Marvel, the penciller was the primary creator, laying out stories with empty captions and balloons for the so-called writers to fill-in. In Kevin Smith’s Chasing Amy, Jason Lee plays Ben Afflleck’s inker and takes insult when called a “tracer.” Lee’s name also appears below Affleck’s in the actual credits. By the end of the film, Lee has ended their collaboration. H. G. Wells was wise never to begin one with Henry James.

[And if you’d like to read more about their correspondence, check out Nicholas Delbanco’s Group Portrait: Joseph Conrad, Stephen Crane, Ford Madox Ford, Henry James and H. G. Wells. ]

September 28, 2015

About Last Night

Superheroes just want to settle down and get married.

Or at least they used to. Spring-Heeled Jack, Night Wind, Gray Seal, Zorro, Blackshirt, most of the pre-Depression pulp crowd eventually hung up their masks and retired into the domestic oblivion of happily everafter.

Or tried to. Until their readers and publishers and writers demanded sequels. But once you’ve closed the marriage plot, it’s hard to pry it back open. Fortunately the early pulp writers invented a utility belt’s worth of solutions, all still in use:

1) Poker Night.

Yes, darling, we’re married now, but I still have my manly pastimes.

Baroness Orczy’s Scarlet Pimpernel kept it up for decades. Ditto for Graham Montague Jeffries’ Blackshirt. Just one problem though. No more titillating romantic subplot. The hero is domesticated, all that manly excess bunched neatly into his briefs. For Frederic van Rensselaer Dey’s Night Wind, that meant promising his new bride to stop breaking the arms of police officers who foolishly got in his way. By the second sequel, the speedster superman was barely using any of his mutant powers, and his series quietly petered away.

Domestication has proved equally disastrous for modern heroes. The mid-90’s Lois & Clark: the New Adventures of Superman enjoyed stellar ratings, right up to the wedding episode, after which viewership nosedived and the show was cancelled. Marriage is kryptonite. Even Orczy and Jeffries had to switch to other family members (sons and ancestors) to keep their plots going.

2) Dial M.

Wife holding you down? No problem. Just kill her.

Thanks so much, Louis Joseph Vance, for introducing this heartless trope in the first of your seven Lone Wolf sequels. Though his 1914 gentleman thief had happily settled down with the law enforcement agent who lovingly reformed him, Vance dispatches her between books, mentioning her death in passing chapter one dialogue. When Hollywood adapted Robert Ludlum’s first Bourne Identity sequel, they made sure we got to witness the girlfriend’s death (Ludlum, in chivalrous contrast, only sent her off to stay with relatives.)

It’s a grim choice, but one that acknowledges narrative logic. For the superhero to marry, he usually unmasks and retires, and so ending the retirement also ends the marriage. Happily everafter is also a hard place to scrape up plot conflict. In 1973, when Marvel could no longer write around Spider-Man’s eight years of romantic contentment, they shoved his girlfriend off a bridge. Gwen Stacy (and the Silver Age of comics) died with a SNAP! of her too happy neck. Gwen’s 2014 death had a similar effect on the Spider-Man film franchise.

3) Groundhog Day.

Marriage? What marriage?

Johnston McCulley is responsible for the first superhero reboot. When Douglass Fairbanks donned Zorro’s mask and turned an obscure vigilante hero into an international icon, McCulley simply ignored the ending of his own novel when he wrote his first sequel. Zorro did not unmask, he did not retire, and he certainly didn’t run off and get married.

This solution remains annoyingly common. After two decades of marital bliss between Peter Parker and Mary Jane, Marvel signed a deal with the devil (Mephisto in the comic) and rebooted an unmarried Spider-Man in 2008. Like Zorro, Peter had also unmasked publicly, an event erased from the minds of all onlookers (but not, alas, all readers). Lois and Clark, who were married (like their short-lived TV counterparts) in 1996, suffered the same fate when DC rebooted their entire, romantically-challenged universe in 2011. In fact, the very idea of the reboot came from the editorial staff’s frustration with the Lane-Kent status quo and how its innate dullness prevented them from cooking up a new Superman love triangle.

However you handle it, marriage is hell on a writer. But the last solution is my favorite:

4) Perpetual Foreplay.

Frank Packard ended his first Gray Seal book with an implied bang. His proto-Batman waltzes off-stage with his superheroine girlfriend, unmasked nuptials to follow. But when bad guys and good sales returned the hero to active duty in 1919, the door to their bedroom bliss slammed shut. Since the Gray Seal’s do-gooding adventures were motivated not by revenge or altruism but superheroic lust for his bride-to-be, Packard needed to stretch out their romance plot. His four sequels offer increasingly frustrating reasons for why the lovers must remain divided.

Awkward as it sounds, Packard’s approach became the strategy of choice among 1930s pulp writers facing the titillating prospect of unlimited sequels.

Starting in 1933, The Spider magazine published a novella every month for a decade. Wealthy socialite Richard Wentworth fights crime as a costumed vigilante while also courting (and putting off) fiancé Nita Van Sloan. Norvell Page (writing under the house name Grant Stockbridge) tells us Wentworth must “sacrifice his hopes of personal happiness” because “the Spider could never marry,” could never “take on the responsibilities of wife and children” while continuing his crime-fighting mission.” Fortunately, Nita, like the Gray Seal’s would-be wife, is endlessly patient.

When William Gibson and Edward Hale Bierstadt adapted Gibson’s The Shadow for radio, they decided the lonely-hearted hero could use a fiancé too. The 1937 premier introduces Lamont Cranston and Margo Lane sipping coffee in his private library, as she begs him to end his career as the Shadow. He’d promised her as much five years ago when their courtship began, but Lamont, like Richard, feels “there is still so much to do” before he can settle down and unmask. “No, Margo,” he explains, “no one must know, no one but you.” And Margo, the ever dutiful (though ever jilted) help-mate, agrees.

But these women aren’t dupes either. They keep their own keys to the batcave. Nita is the Spider’s “best alley in the battle against crime,” “the one woman in the world who knew his secrets.” And Lamont calls the good accomplished by the Shadow “our activities.” Without Margo’s leg work, half of Gibson’s radio plots would stall.

But what other shared “activities” are these couple up to?

Page seems straight-forward enough: “Greatly they loved.” Nita and Richard (would you believe she calls him “Dick”?) share “pleasurable moments together,” though of course “all too brief.” How pleasurable? Page never penned a sex scene, but it’s clear Nina has access to Richard’s bedroom when she leaves him notes while he’s sleeping off a night of adventuring. As far as the Shadow, Alan Moore says it best in Watchmen: “I’d never been entirely sure what Lamont Cranston was up to with Margo Lane, but I’d bet it wasn’t near as innocent and wholesome as Clark Kent’s relationship with her namesake Lois.”

Since unmasking is the climax of the superhero romance plot, these lovers know each other in every sense. The marriage plots never technically closes, but pulp readers knew what was happening between the covers.

September 21, 2015

The Talented Ms. Highsmith

Before meeting Alfred Hitchcock on a train to Hollywood fame, Patricia Highsmith wrote comic books. It was 1942, the height of the Golden Age boom, and a pretty good first job for an English major fresh from commencement. She started at the now largely forgotten Standard Comics but graduated to Timely (AKA Marvel) before leaving the field in 1948—when superheroes were dropping faster than Tom Ripley’s murder victims.

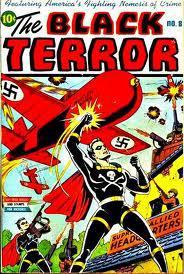

When she published The Talented Mr. Ripley in 1955, the comics market had been bludgeoned to near death by Congress and the Code. She had not been called to testify before the Senate because she had killed off the fact of her first career with a splatter of white-out. Comic books? What comic books? If outed by some sleuth of an interviewer, she might admit to having dabbled with Superman or Batman, but she had probably climbed no higher up the superhero pantheon than the Black Terror, a skull-and-bone chested knock-off since abandoned to public domain.

But for a highbrow author trying to bury her lowbrow past, Ms. Highsmith planted a lot of clues. Tom Ripley’s first victim (of tax scam, the murders come later) is a comic book artist who, Tom therefore assumes, “didn’t know whether he was coming or going.”He even knows that the artist’s “income’s earned on a freelance basis with no withholding tax,” making him an easy mark. Tom’s single real friend, Cleo, doesn’t draw comics, but “painted in a small way—a very small way”; her “imaginary landscapes of a junglelike land” were “no bigger than postage stamps” (like panels in a Thrilling Comics adventure perhaps?). Even Dickie, Tom’s first murder victim, is a painter, albeit a “lousy amateur,” though Tom pictures his pen-and-inks of ships as “precise draftsman’s drawings with every line and bolt and screw labeled.” Tom even takes up a brush himself, imitating Dickie’s mediocre smears.

As far as superpowers, Tom is an old school master-of-disguise. When defrauding that comic book artist, he becomes General Director of the IRS Adjustment Department, drawling “like a genial codger of sixty-odd” years. He wields an eyebrow pencil and a bottle of peroxide wash too, but knows a touch of putty on the end of his nose would be too much. The art of impersonation is a matter of mood and temperament, adopting just the right facial expressions and gait. Besides, he’d always “wanted to be an actor,” and after beating his would-be BFF with a boat oar and stealing his identity, he gets his chance. He even adopts Dickie’s flawed Italian, and of course his signature (“seven out of ten experts in America had said they did not believe the checks were forged”).

Highsmith is a mistress-of-disguise too. Comics were the least of the skulls and bones in her closet. After Hitchcock made her name by adapting her first, 1950 novel, Strangers on a Train, she published The Price of Salt as alter ego Claire Morgan. I’ve not read it, but I think Dr. Wertham and his buddies in the Senate would have cited Ms. Morgan’s sexual proclivities as further evidence of the unwholesomeness of the comics industry. Claire, like her creator, was bisexual, and, worse, dared to end her lesbian romance on a note of hope for her unrepentant protagonists.

Mr. Ripley has the same origin story. He’s stalked by the specter of his own homosexuality, repeatedly labeled “pansy” and “sissy” and “queer.” As a result, he can’t embrace any sexuality. “I can’t make up my mind whether I like men or women,” he jokes, “so I’m thinking of giving them both up.” But where does all that smoldering energy go? Blunt objects. His second murder weapon is an ashtray. The victim is a “selfish, stupid bastard who had sneered at” Dickie, “one of his best friends—just because he suspected him of sexual deviation.” When Tom was alone in a boat for the last time with Dickie (oh, don’t even start on the oar-sized penis jokes), he realized he could have “hit Dickie, sprung on him, or kissed him, or thrown him overboard.” The thwarted sexual impulse is steered into violence. For that tentative reason, I’m not appalled at Ms. Highsmith for ending her crime novel on a note of triumph for her unrepentant protagonist. Like Claire, Tom goes unpunished.

Or at least not legally punished. The damage he commits on himself is deeper. When forced to abandon his socialite existence as the gentlemanly Dickie, he “hated becoming Thomas Ripley again . . . as he would have hated putting on a shabby suit of clothes.” His former self, “Tom Ripley, shy and meek,” becomes just another performance—like the one a certain superpowered alien from Krypton adopts. He decides to “play up Tom a little more . . . He could stoop a little more, he could be shyer than ever, he could even wear horn-rimmed glasses and hold his mouth in an even sadder, droopier manner.” When Highsmith said she wrote Superman and Batman, she meant Clark Kent and Bruce Wayne, the ying and yang of her shapeshifting murder’s Tom and Dickie duality.

Superman and Batman make an appearance too. Yes, Tom fits the standard orphan model (“My parents died when I was very small”), but Highsmith pulls back her superhero mask even further as Tom stands aboard a ship, all but certain he’s finally to be arrested: “He imagined strange things: Mrs. Cartwright’s daughter falling overboard and he jumping after her and saving her. Or fighting through the waters of a ruptured bulkhead to close the breach with his own body. He felt possessed of a preternatural strength and fearlessness.”

In another, less homophobic universe, Mr. Ripley might have saved himself by using his considerable talents for good. Instead, he bludgeons the Comics Code established the year before he was published:

Crimes shall never be presented in such a way as to create sympathy for the criminal

No comics shall explicitly present the unique details and methods of a crime

Criminals shall not be presented so as to be rendered glamorous or to occupy a position which creates the desire for emulation.

In every instance good shall triumph over evil and the criminal punished for his misdeeds.

And most importantly:

Illicit sex relations are neither to be hinted at or portrayed. Violent love scenes as well as sexual abnormalities are unacceptable.

Sex perversion or any inference to same is strictly forbidden.

It’s enough to twist even Batman and Superman into sociopathic serial killers.

September 14, 2015

What’s Funny About This Picture?

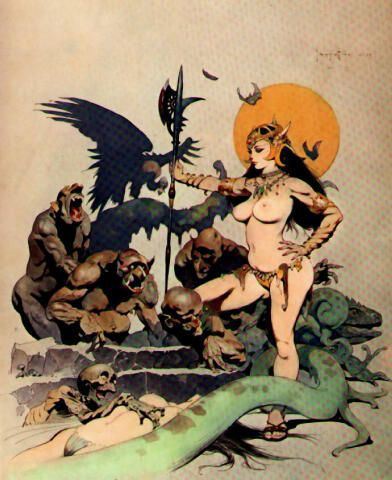

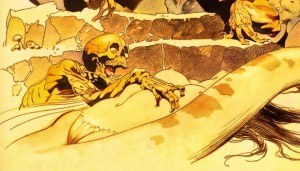

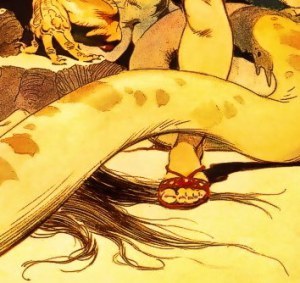

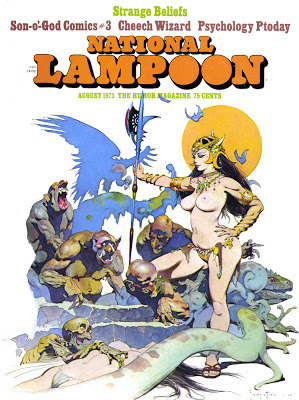

I was seven the first time I saw this illustration. I’d never heard of Frank Frazetta, but forty years later I still recognize the style. I assumed it was an Eerie or Creepy cover, but flipping through online databases and comic-con long boxes unearthed nothing. My memory had added a throne, so my description to vendors didn’t help either.

I knew it was early 70s because I’d seen it during a family vacation in Cape May, NJ. We went multiple years, but stayed only once in the Sea Mist Hotel–on the second or third floor, the right side, in what seemed like an improbably large open space.

An adult cousin–I don’t know which of my father’s nephews–was suddenly staying with us too. He’d arrived on a motorcycle and slept in a sleeping bag in his underwear on the floor. I slept in my briefs, but with pajamas over top, so his relative nakedness confused me, a change in the rules.

The magazine was his. It confused me too. It was sitting on a large table, more or less chin height, as I studied the cover at what must have been a distance of inches. It didn’t occur to me to open it or to pick it up. Though there was nothing taboo in its placement, no sudden parental shuffling of papers, I felt something transgressive. The breasts presumably. I’d seen my mother naked, but this was different, another shifting of known rules.

This was 1973, only months before my parents’ separation. I turned seven in June. Frazetta penned “72” next to his signature, but the magazine logo hides it. I had no idea he’d illustrated a National Lampoon until the cover popped up on my laptop during a recent Google search. No. 41, August, so on stands in July when my cousin grabbed his copy on the way to a beach getaway.

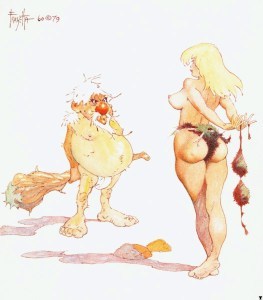

I’m still not sure what it’s doing on the front of “The Humor Magazine.” Frazetta drew the occasional Playboy-esque cartoon,

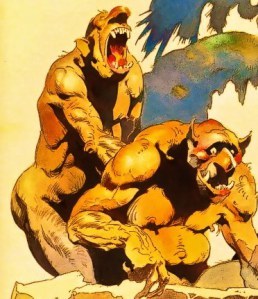

but “Ghoul Queen” is closer to the distortions of his fantasy style. Still, the ghouls are more comic than menacing,

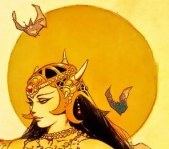

and their queen’s hip-to-waist ratio exceeds even Frazetta’s usual idealized proportions.

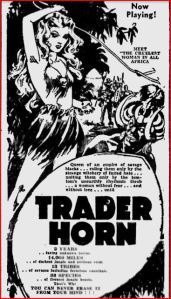

An editor’s note claims he drew it for a previous “Tits ‘n’ Lizards” issue, but that’s just an example of the magazine’s “Humor.” Looking at the cover now, I’m still confused. Female nudity aside, the image seems to be about race. A white woman reigns over her dark-skinned minions. This could be the White Goddess and her African worshipers in 1931’s Trader Horn.

Instead of Aryan curls, Frazetta endows his goddess Asian overtones–or is that just make-up? This bejeweled yet rag-wearing Queen must spend a lot of time plucking her eyebrows.

Despite all the abundant white flesh glowing in front of them, the ghouls’ eyes are averted. The Queen is displayed for the viewer only. The image dramatizes the Mississippi racial rules that Emmett Till violated in 1955. A white woman’s body is always taboo to dark-skinned males, no matter how outlandishly posed.

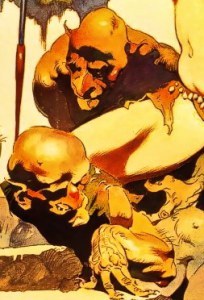

Sculptor Tim Bruckner also suggests a homoerotic dimension to Frazetta’s sex fantasy: “having to decide what some of the ghoul pairs were doing behind her was something best left to the imagination.”

Are those expressions of monstrous pleasure? Are the obscured arms of the rear figures directed toward their crotches? Do the splayed fingers and curved wrists of the foregrounded hands denote submission? Does the apparent orgy explain their disinterest in the Queen’s body, or is this how dark males control their desire for white female flesh? And why the hell did Frazetta draw an extra left hand groping around her hip?

I see other anatomical issues (her face is too small, her breasts too round), but I’m more concerned with the ones I can’t see. Like her right leg. The pose suggests that the knee is bent so that the right calf is vertical, like so:

Except that space is occupied by a ghoul. The Queen’s leg isn’t hidden by his back–their bodies overlap as if collaged from separate planes. The two images don’t belong together. Maybe that’s why the ghouls aren’t ogling their queen, and why her gaze skirts past them too. It would also explain the floating hand. Frazetta was revising. The 3-D impossibility is further augmented by the two-dimensions of the image. It’s a painting, so obviously two-dimensional, but Frazetta emphasizes that fact by not filling the entire canvas. The sky behind the figures and the ground in front of them are the same continuous, unpainted space. He even flattens the vulture so its outlined body is almost as undifferentiated as the moon.

None of this struck my seven-year-old imagination. After an anxious glance at the Queen’s towering authority, my eyes dropped to the discordant subplot at the bottom of the page. The snake offers a range of mysteries (is it attached to the lizard’s head? what are those snail-like appendages?), but I was busy contemplating the two other figures.

I’m tempted to say this is the moment I first realized I was straight. But I didn’t realize anything. I just sensed something inexplicable. When I rediscovered the image online, I wasn’t sure it was the same–where was the throne?–until my eyes dropped to the skeleton’s hand again. I could feel it as if looking at a photograph of my younger self and remembering the sensations of the frozen moment. The dark-skinned ghouls and their domineering queen had nothing to do with me, but that skinless skeleton hungrily pawing an unconscious woman’s body, that’s who I identified with. That was me.

It’s not the cover image to my sexuality I would choose. It merges incompatible desires–is the skeleton’s mouth wide with arousal, or is he (“he”) anticipating a juicy meal? Either way, he’s a predator. Though not, apparently, a hunter. The woman is a discarded scrap, literally below the interest of the queen and her ghouls. Even the snake-lizard stares off indifferently as the woman’s face is obscured by its Freudian body. I understood her then and now to be unconscious, though she might as easily be dead. Perhaps her erect nipples signify living prey.

So my first inkling of sexuality was triggered by a fantastical representation of date rape. The girl’s been roofied. It’s a dire contrast to the Ghoul Queen–a woman commanding a gang of four grotesque but muscular males who have the physical ability to overpower her but instead bend and crawl at her feet (while possibly having anal intercourse). She is the painting’s largest figure, the tallest, spanning nearly the height of the frame, her figure embodying unchallenged authority. If not for the voyeuristic nudity, you might call her image feminist.

But then there’s the roofied girl, a depiction of abject weakness, the pose reducing her to a faceless and defenseless torso. The Queen’s power is positioned over this lower image, appears somehow predicated on it. While her impersonal eyes assess her ghouls, her imperial foot pins the unconscious girl’s hair. She is literally standing on her.

There’s a range of unstated narrative possibilities–does the Queen maintain power by sacrificing her Caucasian sisters to the dark horde? are only skinless and so racially unidentifiable ghouls allowed to fondle white flesh?–but the pose says enough. The girl is the Queen’s victim, not the other monsters’.

Why was my skeleton hand drawn to the unconscious girl’s breasts, but not the Queen’s? They’re smaller, so less intimidating? The Queen is equally exposed, but wholly in control of the fact. I can ogle her, but only because she seems to permit it, her chin angled invitingly away. But at any moment, those eyes could turn and gaze back at me. Did my seven-year-old bones inch across the roofied girl’s ribs because she has no eyes to see me? Did my memory fabricate a throne because a seated Queen is less horrifying?

Apparently Tim Bruckner was uncomfortable with these questions too. When he adapted “Ghoul Queen” into a 3-D miniature, he altered more than two dimensions. “It was important to pare down the composition to its essentials,” he said.

Non-essentials include ghoulish racism, slithering homophobia, and date-rape misogyny. But the skeleton remains–though not the nature of its now non-predatory hunger. “There’s nothing coy or retiring about a Frazetta woman,” explained Bruckner. “Even simply standing with a pike, her hand on her hip, being admired by one of the undead, she announces her presence with every sensuous curve of her body.” Bruckner literally turns my skull’s desire toward a stance of female power.

But I still wouldn’t choose the revised Ghoul Queen for my cover art. National Lampoon dubbed their issue “Strange Beliefs,” a better title for the painting too, though I doubt the editors knew they were lampooning American sex and racial norms. They presumably didn’t know they were lampooning me.

September 7, 2015

Superman on Trial

Can reading detective fiction and Superman literature turn you into a supervillain? Super-lawyer Clarence Darrow says yes. He argued his case this week in 1924.

The facts were indisputable. His clients, Dickie Loeb and Babe Leopold rented a car, picked up Dickie’s fourteen-year-old cousin Bobby from school, and bludgeoned him with a chisel in the front seat. After stopping for sandwiches, they stripped the body, disfigured it with acid, and hid it below a railroad track. When they got home, they burnt their blood-spotted clothes and mailed the parents a ransom note. It was the perfect crime.

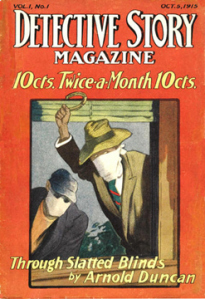

Dickie was nineteen, Babe twenty, but both had already completed undergraduate degrees and were enrolled in law schools. They were also both voracious readers. Darrow, their defense attorney, detailed Dickie’s literary tastes: “detective stories,” each one “a story of crime,” ones, he said, the state legislature had wisely “forbidden boys to read” for fear they would “produce criminal tendencies.” Dickie “devoured” them. “He read them day after day . . . and almost nothing else.”

Darrow didn’t mention any titles, but Dickie must have snuck stacks of Detective Story Magazine past his governess. The Street and Smith pulp doubled from a bi-monthly to a weekly the year he turned twelve. Johnston McCulley was a favorite with fans. His gentleman criminal the Black Star wears a cape and hood with an emblem on the forehead. So does his Thunderbolt. Darrow said Dickie’s pulps “all show how smart the detective is, and where the criminal himself falls down.” But the detectives chasing the Man in Purple, the Picaroon, the Gray Ghost, the Joker, the Scarlet Fox—they never catch their man. Those noble vigilantes remain safely outside the law. They are also all young men born into wealth who disguise their secret lives. So Dickie, the son of a corporate vice-president, learned to play detective, “shadowing people on the street,” as he fantasized “being the head of a band of criminals.” “Early in his life,” said Darrow, Dickie “conceived the idea of that there could be a perfect crime,” one he could himself “plan and accomplish.”

Babe was an impressionable reader too. He’d started speaking at four months and earned genius level IQ scores. Darrow called him “a boy obsessed of learning,” but one without an “emotional life.” He makes him sound like a renegade android, “an intellectual machine going without balance and without a governor.” Where Dickie transgressed through pulp fiction, “Babe took to philosophy.” Instead of McCulley, Nietzsche started “obsessing” Babe at sixteen. Darrow called Nietzsche’s doctrine “a species of insanity,” one “holding that the intelligent man is beyond good and evil, that the laws for good and the laws for evil do not apply to those who approach the superman.” Babe summed up Nietzsche the same way in a letter to Dickie: “In formulating a superman he is, on account of certain superior qualities inherent in him, exempted from the ordinary laws which govern ordinary men.” A member of “the master class,” says Nietzsche himself, “may act to all of lower rank . . . as he pleases.” That includes murdering a fourteen-year-old neighbor as one “might kill a spider or a fly.”

So Babe considered Dickie a fellow superman. And Dickie considered Babe a perfect partner in crime. The two genres have one formula point in common: heroes are “above the law.” When Siegel and Shuster merged Beyond Good and Evil with Detective Story Magazine in 1938, they came up with Action Comics No. 1. Loeb and Leopold only got Life Plus 99 Years, the title of Babe’s autobiography. Prosecutors wanted to hear a death sentence, but Darrow wrote a modern law classic for his closing argument. It brought the judge to tears.

William Jennings Bryan liked it too. He quoted excerpts during the Scopes “Monkey” trial the following year. Bryan was prosecuting John Scopes for teaching the theory of evolution in a Tennessee high school, and Darrow was defending him. Scopes, a gym teacher subbing in science, used George William Hunter’s school board-approved Civil Biology, a standard textbook since 1914, and one that shocks my students when I assign it in my “Superheroes” course.

“If the stock of domesticated animals can be improved,” writes Hunter, “it is not unfair to ask if the health and vigor of the future generations of men and women on the earth might not be improved by applying to them the laws of selection.” After describing families of “parasites” who spread “disease, immorality, and crime,” he argues: “If such people were lower animals, we would probably kill them off to prevent them from spreading. Humanity will not allow this, but we do have the remedy of separating the sexes in asylums or other places and in various ways preventing intermarriage and the possibilities of perpetuating such a low and degenerate race.”

This was one of Bryan’s main objections to evolution, a term he used interchangeably with eugenics: “Its only program for man is scientific breeding, a system under which a few supposedly superior intellects, self-appointed, would direct the mating and the movements of the mass of mankind—an impossible system!”Bryan links eugenics to Nietzsche, as Darrow had the year before, saying Nietzsche believed “evolution was working toward the superman.” The claim is arguable, but the superman was “a damnable philosophy” to Bryan, a “flower that blooms on the stalk of evolution.”

“Would the State be blameless,” he asked, “if it permitted the universities under its control to be turned into training schools for murderers? When you get back to the root of this question, you will find that the Legislature not only had a right to protect the students from the evolutionary hypothesis, but was in duty bound to do so.”

Darrow declined to make a closing argument, preventing Bryan from making his before the judge too, so their final debate played out in newspapers. Either way, Darrow was talking from both ends of his ubermensch. “Loeb knew nothing of evolution or Nietzsche,” he told the Associated Press. “It is probable he never heard of either. But because Leopold had read Nietzsche, does that prove that this philosophy or education was responsible for the act of two crazy boys?”

Perhaps Darrow’s hypocrisy is an illustration of a superman only obeying his own laws. It didn’t matter though. Like Loeb and Leopold’s, Scopes’ guilt was never contested, and the court fined him $100 (later overturned on a technicality). That was 1925, the year the Fascist-inspired “super-criminal” Blackshirt joined Zorro and his merry band of pulp vigilantes, while Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf climbed the German best-seller list.

Superman was ascending.

August 31, 2015

Superhero Screenplay, Act 1

New York Times reviewer A. O. Scott declared in 2012 that the superhero movie genre, “though it is still in a period of commercial ascendancy, has also entered a phase of imaginative decadence.” According to Scott, it’s been all downhill since Heath Ledger won the 2008 Best Supporting Actor for the Joker.

I think 2008 was the tipping point too, but not because of The Dark Knight. I miss movies like Peter Berg’s Hancock. Not because Hancock is better than The Dark Knight–it’s not–but because Hancock marks the moment Hollywood stopped experimenting with original superheroes.

M. Night’s Shyamalan’s 2000 Unbreakable is another good, imperfect movie–one made better in retrospect because of its ability to experiment with tropes by creating its own characters. 2008 also marks the start of Marvel’s ascendancy with Iron Man, and so the financial incentive to duplicate instead of innovate. The experimental phase was over.

So I am returning to the year 2008 of an alternate Earth in which an alternate Hollywood did not embrace the Marvel and DC pantheons, but instead explored those formulas with new characters who mirrored and warped the Avengers and Justice League in new directions. This screenplay isn’t necessarily better than those coming out of Hollywood these days (except for the Fantastic Four, it’s definitely better than the Fantastic Four), but at least it’s not identical to them.

Here’s the first act:

THE DAILY STAR

LOGLINE: Superheroes must escape a government prison that’s brainwashed them into thinking they’re only their mild-mannered alter egos.

INT. BLACK SCREEN.

JOHNNIE (V.O.)

Okay, let’s get this started.

INT. LOLA’S BEDROOM — MORNING.

Close-up of LOLA’s face, eyes closed, head on pillow. A pair of hands opens her eyes and shines a medical flashlight into each. Another pair of hands is touching up her make-up. Voices continue as though through headphones from a remote location.

TECHNICIAN ONE (V.O.)

Initiating reboot.

TECHNICIAN TWO (V.0.)

Chip interface engaged.

JOHNNIE (V.O.)

Clear the room.

TECHNICIAN TWO (V.0.)

All levels clean and steady.

JOHNNIE (V.O.)

I said clear the room.

All hands withdraw.

TECHNICIAN THREE (V.O.)

Active in three . . . two . . . one.

LOLA opens her eyes.

TECHNICIAN ONE (V.0.)

We are online.

LOLA sits up in bed and blinks. She’s expressionless, perhaps a little uncertain as she takes in her perfectly decorated and antiseptically neat bedroom. Her nightgown is blandly conservative. The alarm clock on her bedside table starts beeping as it flips to 7:00. She turns to look at it but doesn’t turn it off. A skirt suit is draped across a chair ready to wear. She touches it and then withdraws her hand. A row of star-shaped, newspaper writing awards stand on her desk. She looks at them and blinks expressionlessly and then touches her temple as though registering a vague pain.

TECHNICIAN THREE (V.O.)

Ah . . . do we have a problem?

JOHNNIE (V.O.)

Hang on.

TECHNICIAN TWO (V.O.)

Maybe yesterday’s containment dose was too—

JOHNNIE (V.O.)

I said wait.

Finally, LOLA shakes off her daze, clicks the alarm off, and steps off screen to start her day.

JOHNNIE (V.O.)

Okay. We’re rolling.

INT. SURVEILLANCE ROOM — DAY.

Pan across a row surveillance screens as technicians chatter. We see LOLA stepping into her shower, and then five other subjects at increasingly later points in their morning routines: dressing, eating breakfast, kissing a wife goodbye, hailing a taxi on the street.

The fifth, however, is CARL CLARKSON, who remains in bed. The camera pauses on his sleeping face, which twitches as if he’s lost in a disturbing dream.

JOHNNIE (V.O.)

And how’s our big boy doing?

TECHNICIAN TWO (V.O.)

Sleeping like a baby.

TECHNICIAN THREE (V.O.)

Scary, big-ass baby with artificially suppressed circadian cycles.

TECHNICIAN ONE (V.O.)

Ready, sir?

JOHNNIE (V.O.)

Yeah. Hit him.

INT. CARL’S BEDROOM – DAY.

CARL jerks awake, disoriented. His childish pajamas are mismatched, half-inside out, and a size too large and/or too small. The bedroom is an equally flamboyant mess. He grabs the alarm clock on his bedside table, knocking his glasses and a newspaper to the floor in the process.

CARL

I forgot to set it again?!

He fumbles out of bed, chasing his glasses across the fallen newspaper. Camera follows his feet as he steps on the newspaper and stubs his toe on an inconveniently positioned chair. He puts on his glasses and makes his way to the bathroom, cursing “Darn it! Darn it!” Zoom into the front page of The Daily Star and a photograph of OMEGA MAN in full superhero costume. Zoom closer to reveal that OMEGA MAN’s face is CARL’s, only grinning and beaming with confidence.

CREDITS OVER A SEQUENCE OF NEWSPAPER PHOTOGRAPHS.

Documentary-style pan over Daily Star photos of THE POWER LEAGUE, some posed, some in action. OMAGA MAN and AMAZONIA are most prominent, with SHAPESHIFTER, SPEEDSTER, CYBORG and POWER RING. The characters’ garish unitards look absurd, but their actions appear nonetheless superhuman. The last headline reads: “Power League Thwart Dr. Megastein Again.” There’s a photo of AMAZONIA punching a supervillian. The byline includes a small image of reporter LOLA LITTLE in perfect make-up and her hair in a confining bun.

INT. BACK SEAT OF TAXI — DAY.

The newspaper is held by a pair of well-manicured hands, which fold the paper to reveal LOLA looking identical to her photo. Setting the paper aside, she glances outside at detour signs and construction crews working around bomb-like craters in the street.

LOLA

What’s all the damage from?

TAXI DRIVER

You mean the construction? Didn’t you hear? They’re extending the subway line. It’s always something, ain’t it?

LOLA nods and rubs her temple as though just aware of a forming headache.

EXT. STREET — DAY.

LOLA steps out of the stopped taxi and pays the driver through his window. She’s carrying her briefcase and two newspapers.

LOLA

Keep the change, Max.

TAXI DRIVER

Thank you, Miss Little! You have a good day now!

Pan up the height of the 1930s era skyscraper to the giant Daily Star star-logo mounted on the roof, identical to Lola’s star-shaped awards. The building, like the streets, appears to have sustained recent damage.

INT. DAILY STAR LOBBY — DAY.

LOLA strolls past fresh-looking plywood blocking ruined walls; only a sign, “The Marketplace,” indicates that a café previously filled the space. A JANITOR is mopping the floor by the elevators.

LOLA

Morning, Charlie. What happened in here?

JANITOR

Renovations. Always got to be changing something, don’t they, Miss Little?

LOLA nods, frowning at other signs of damage in the lobby, but keeps moving to the waiting elevator. JANITOR glances back at her before speaking into a microphone in his collar.

JANITOR

Gamma at final checkpoint.

EXT. STREET — DAY.

Cab pulls up, and CARL rushes out. His tie is crooked and he’s fighting back a yawn.

DRIVER 2

Hey buddy, you gotta pay me!

CARL fumbles with his wallet and briefcase, almost dropping both.

CARL

Oh, gosh, I’m so sorry, here, it’s a, how much, let me, um . . .

The DRIVER takes a bill.

DRIVER

Thanks for the tip.

CARL

Oh, actually, if you could give me . . .

The taxi pulls away.

INT. ELEVATOR — DAY.

LOLA enters the elevator, and the doors begin to close as she sees CARL running toward her.

CARL

Lola! Hold the door please! Lola!

She grimaces, and her hand shoots for the “close” button, but then freezes. At the last moment, she presses “hold” instead. CARL steps inside with a look of surprise.

CARL

Well, thank you, Lola.

LOLA

No problem, Carl. We’re partners after all. Need to watch each other’s back.

CARL

Partners. Wow. I always sort of got the sense you saw me as a kind of, I don’t know. Competitor? Not, I mean, I’m obviously not half the reporter you are, but —

He interrupts himself with an achingly wide yawn.

CARL

Oh my, excuse me. I can never seem to get a good night’s sleep.

LOLA begins to reflexively agree, but then stops, surprised.

LOLA

Actually. I slept great last night. Best sleep I’ve had in years.

(a realization)

I feel like a new person.

INT. DAILY STAR NEWSROOM — DAY.

Elevators doors open to an expansive newspaper newsroom, reminiscent of the 1970s. LOLA almost steps out but then freezes. She blinks out at the room. CARL stares at her, confused that she’s not jumping into her day.

CARL

After you, Lola?

LOLA steps out, gazing around uncertainly. MR. BLACK, Editor-in-Chief, steps between LOLA and CARL.

BLACK

Afraid you two were trying to take the day off.

CARL

Of course not, Mr. Black, we would never –

BLACK

What’s the status on the Omega Man feature?

LOLA is in a daze.

BLACK

Lola?

LOLA

What? Oh. Sorry, Chief. Final edits. On your desk by noon.

BLACK

And the Governor’s interview?

LOLA

His people are whining for an advance look, but I said . . .

BLACK

You said . . . ? No way, right?

LOLA

Right. Of course, I did. Wasn’t part of the . . .

BLACK

Deal.

LOLA

Deal.

BLACK looks at her nervously, but moves on to CARL.

BLACK

How about you, Carl? You ever going to finish that global warming thing?

CARL

Actually, my source is getting cold feet, so I may have to call another expert, you know, to make sure the data is absolutely correct?

BLACK

Playing it safe, Carl. That’s what we like about you.

BLACK pats CARL on the back and watches him walk toward his desk. BLACK surreptitiously inserts a Bluetooh in his ear and speaks under his breath.

BLACK

Omega on script, but Gamma barely functional. Thought you said she sustained no damage yesterday?

INT. SURVEILLANCE ROOM — DAY.

A metallic, high tech room with a wall of surveillance screens and TECHNICIANS in the background. Most of the screens now show angles of the newsroom. JOHNNIE, a twenty-something incongruously dressed in a bowtie and suspenders, speaks into a Bluetooth while snapping his fingers at one of the TECHNICIANS.

JOHNNIE

She checked out, but they’re running another diagnostic right now.

TECHNICIANS jump to action at the implied command. Move in closer to the screen in front of JOHNNIE to show a black and white image of BLACK standing in the newsroom. He glances up at the ceiling camera.

BLACK

Good. Now get out here with those donuts.

BLACK pockets Bluetooth.

INT. NEWSROOM, CARL’S WORKAREA – DAY.

CARL stumbles over a trashcan as he reaches his desk; he’s watching LOLA intently across the newsroom. CY, another reporter, is seated at the adjacent desk, fighting with a 90s era PC.

CY

Why won’t this thing work? I hate these damn machines! Hate them!

CARL

Why don’t you call IT? I swear you do this every . . .

CARL watches LOLA rubbing her forehead in pain as she arrives at her desk.

CY

You say something, Carl?

CARL

Sorry, Cy. You should just ignore me. I swear I’m not myself today.

CY

Yeah, you look a little off. I’d tell you to go home, but . . .

(gesturing at BLACK entering the conference room)

when was the last time the chief gave any of us a day off?

CARL tries to echo Cy’s good-natured laugh as CY stands and heads toward the conference room with his yellow pad.

INT. NEWSROOM, LOLA’S WORKAREA – DAY.

LOLA sits at her desk as the extravagantly dressed fashion editor, CAMELLIA, strolls by. Her pearl CHOKER stands out from the rest of her outfit. LOLA is too distracted to notice her.

CAMELLIA

Morning, Lola.

LOLA

Oh, Camellia. Hi. Good morning. Nice out . . .

Something catches LOLA’s eye, and CAMELLIA flinches, afraid her appearance is imperfect.

CAMELLIA

What’s the matter?

LOLA

Is that the same choker you wore yesterday?

CAMELLIA

This old thing? I just threw it on today for a lark. Classy, don’t you think? Some things never go out of . . .

She appraises LOLA’s suit and sneers, before sauntering off.

CAMELLIA

Style.

LOLA looks around her desk, still dazed. ROGER is seated at the desk adjacent to her; he’s rifling through drawers frantically searching for something.

ROGER

Where is it? Where the hell is it?

LOLA

You lose something, Roger?

ROGER

My ring. It was right here a second ago.

LOLA

Don’t worry. I’m sure it’s . . .

LOLA looks around the newsroom with an anxious expression.

LOLA

. . . somewhere.

JOHNNIE, now acting the part of a boyish intern, jogs past carrying a donut box.

JOHNNIE

Staff meeting in the conference room, one minute!

LOLA, jarred back into action, grabs one of her two newspapers and starts to follow him, but stops when she notices JANIE, young sports reporter dressed in a running suit, slumped at her desk. Everyone else is moving into the conference room.

LOLA

You okay, Janie?

JANIE lifts her head, bleary-eyed.

JANIE

I just can’t seem to get myself moving today.

LOLA

Here. Let me give you a hand.

LOLA helps her stand and the two hobble toward the conference room together.

INT. CONFERENCE ROOM — DAY.

A long table with a wall of windows looking out at the city, except one of the windows has been recently cracked and is sealed with tape. The walls are decorated with framed Daily Star front pages that feature large photographs of the Power League members. Everybody is taking seats. BLACK notices CARL looking intently at LOLA as she enters with JANIE. BLACK slides the box of donuts at him.

BLACK

Make yourself useful, Carl.

CARL

What, sir? Oh. Right, sorry.

CARL struggles to open the box, his eyes still on LOLA. She sits as JANIE crumples into the last chair. LOLA looks at the cracked window.

LOLA

What happened in here? I swear this town looks like a war zone today.

JOHNNIE

Oh, funny story, Miss Little! Those window cleaner guys were messing around with that elevator thingy when one of the controls –

BLACK grabs the box of donuts from CARL, zips it open, and skids it to the center of the table.

BLACK

Okay, people, listen up, we got a big day here. I need everybody 100% focused.

JOHNNIE

Gosh, Mr. Black, don’t we ever get a day off?

BLACK

If we make this deadline, we can all have a well earned vacation. But first thing first. Camellia, how’s that fashion spread?

CAMELLIA

I need another half-page.

BLACK

No changes.

CAMELLIA

But the photos are so tiny, you can’t see —

BLACK

How many times do we have to go through this? Stay inside your borders.

During BLACK and CAMELLIA’s exchange, CARL notices ROGER neurotically winding a piece of paper around his ring finger.

ROGER

(whispering)

Have you seen my ring, Carl? My wedding ring? I swear I was just wearing it. If my wife finds out I lost it she’s going to kill me.

CARL

I haven’t seen it, Roger. Did you leave it at home?

BLACK

Something you two want to share, Carl? It’s only a newspaper I’m trying to run here. I don’t have to tell you how important this edition is. Cy, the technology insert, ready to print?

CY

It would be if my PC hadn’t crashed. Now I’m going to have to retype the whole —

LOLA

Why is it important?

All look at her in startled silence. CARL’s reaction is particularly acute.

CARL

What did you say, Lola?

LOLA

This edition? We put out a paper every day. What’s so important about today’s?

More stunned silence.

JOHNNIE

Gosh, Miss Little, that’s not a very constructive attitude.

CAMELLIA

Next she’s going to say newspapers are a dying breed or something.

JOHNNIE

It’s like Mr. Clarkson is always saying — what’s that expression of yours, Mr. Clarkson?

CARL

Ah . . . live each day like it’s the only one you have?

JOHNNIE

Now that’s what I call philosophy!

CY

Yeah, you’re quite the philosopher, Carl.

CARL

Oh, I didn’t think that up myself —

BLACK

Lola, update everyone on your Omega Man and governor pieces. I haven’t decided which to lead with. Got an opinion?

LOLA

Neither.

The room is further shocked.

BLACK

And what, go with Carl’s global warning thing?

The others chuckle.

CARL

The front page? I really don’t think something I write belongs on —

LOLA

Omega Man, the governor, that’s yesterday’s news.

BLACK

You got someone better to interview?

LOLA

Yes. Doctor Megastein.

Silence, then the staff breaks into more laughter, except for CARL who forces a smile but is looking at LOLA with increasing interest.

CY

Good one, Lola.

JOHNNIE

The most evil supervillain who’s ever lived.

ROGER

Yeah, ask him about his next plan for world domination so the Power League can get ready for it.

CAMELLIA

Ooo, and I can do a photo spread of his tacky battle suits!

LOLA

I’m serious.

BLACK

And how exactly are you planning to find him to get an interview?

LOLA

Well, he is in custody.

Laughter ends with renewed shocked silence. BLACK is about to speak, but CARL cuts him off.

CARL

How do you know that, Lola?

LOLA

It was in the paper.

CAMELLIA

Ah, we write the paper, darling. I think we would have noticed if —

LOLA unfolds the newspaper she’s been carrying. It’s the New York Times. Photo of damaged streets and buildings. Headline: “Government Meta-ops Subdue Terrorist.” There’s a photo of an explosion on the street outside and people running; some kind of aircraft is visible through the smoke. Another photo is a close-up of the terrorist, Dr. Stein, a middle-aged man with a goatee.

LOLA

Not The Star. The Times.

CY

The what?

CAMELLIA

Oh my god, when did this happen?

ROGER

New York has another newspaper!

CY

“Government Meta-ops Subdue Terrorist.”

CAMELLIA

What’s a meta-op?

CARL picks up the paper.

CARL

Lola, where did you get this?

ROGER

What’s a terrorist?

BLACK grabs the newspaper from CARL and shoves it at JOHNNIE.

BLACK

Ok, people, settle down.

JOHNNIE

I’m just going to go check on the, um . . .

JOHNNIE rushes out of the room with the paper.

BLACK

Lola, after the governor and the Omega Man feature are in print, you can interview Adolf Hitler for all I care. Tomorrow. But today we stay focused on today. So get cracking, people! Let’s go! Let’s go!

JANIE jerks awake.

JANIE

Okay! I’m going! I’m going, I’m . . .

She melts back down as others obediently file out. LOLA is rubbing her forehead. ROGER is crawling around on the floor.

ROGER

Has anyone seen my ring?

INT. BLACK’S OFFICE – DAY.

Large desk with exterior windows behind it and in front of it a wall of interior windows with a wide view of the newsroom. BLACK enters and is about to close the door when CARL appears in the doorway.

CARL

Mr. Black, I don’t want to bother you, but I was thinking about what Lola—

BLACK

So don’t.

CARL

Don’t?

BLACK

Bother me.

CARL

(after a self-deprecating chuckle)

But I was thinking—

BLACK

Don’t do that either. You’re not here to think. You’re here to report.

CARL

I know, I do, but if there are reporters at other newspapers who know so much about—

BLACK

Carl. This is the Daily Star. The best newspaper in the world. You know that, right?

CARL

Yes, of course, but—

BLACK

So do your job.

BLACK closes the door. CARL remains visible behind the glass and the slats of the blinds. BLACK twists the cord. CARL tilts to look in through the next window, finger raised to speak, and BLACK closes those blinds too. He closes all of the blinds until he’s sure he has complete privacy.

INT. PRIVATE BATHROOM – DAY.

BLACK steps into the private bathroom connected to his office. He slides the toilet paper dispenser aside to reveal a secret panel with a scanning pad. When he holds his hand to the pad, a green light blinks and the wall of the bathroom begins to open.

INT. SURVEILLANCE ROOM — DAY.

Lola’s taxi driver is seated with the wall of monitors and TECHNICIANS in the background. JOHNNIE is yelling at him while shaking the New York Times in his face.

JOHNNIE

What do you mean it’s not your fault!

TAXI DRIVER

The damage from the attack, I had to take a different route, so when she stops for her paper like always she must’ve found a second vending machine, a real one.

(pointing at newspaper)

I didn’t even know they still sold these damn things!

JOHNNIE

You didn’t keep eyes on her?

TAXI DRIVER

That’s against protocols. Don’t make her paranoid, that’s what you said.

JOHNNIE

Did I also say contaminate the entire meta-quarantine with rogue information?

JOHNNIE doesn’t notice BLACK entering from an armored door behind him. Through the door is a brief view of BLACK’s bathroom and office.

BLACK

Better than chip malfunction.

JOHNNIE turns.

BLACK

I was afraid we were headed for a full defection scenario.

BLACK turns to the TECHNICIANS.

BLACK

The chip is fine, right?

The monitors show the Daily Star staff in the newsroom. Some are just the black and white surveillance images, but others appear higher tech with heat signatures and LED readouts. They are studying LOLA.

TECHNICIAN ONE

All levels within standard ranges.

TECHNICIAN TWO

Her cognitives are running high though.

TECHNICIAN THREE

But expected given the contagion.

BLACK plucks the Times from JOHNNIE’s hand.

BLACK

Which means the problem disappears after reboot.

And he chucks it into a metal wastepaper basket.

TECHNICIAN ONE

If the anomalous behavior is an environmental response, then yes. She wakes up her old self tomorrow.

JOHNNIE

Which is a long time from right now. I say sedate her, keep her isolated until we can purge them all.

TECHNICIAN TWO

You risk serious cerebral damage. Yesterday’s post-activation containment dose would have lobotomized an elephant.

TECHNICIAN THREE

Plus you keep any of them unconscious too long and their cortexes fry.

JOHNNIE

A necessary risk.

BLACK

Tell that to the Pentagon. Look, after what Stein pulled yesterday, this is nothing. Just walk her through her script. We’ve done it a thousand times.

JOHNNIE leans down to stare at LOLA in a monitor as she stands up from her desk. He’s frowning.

JOHNNIE

Right. What could possibly go wrong?

INT. NEWSROOM — DAY.

CARL is seated, carefully squinting at newspaper copy, while cross-referencing information in the several large scientific volumes spread around his desk. He holds a pencil in his hand and is unconsciously driving it into the palm of his other hand. He glances down shocked to see that he’s ground the pencil to a stub, but there’s not a mark on his skin.

LOLA appears behind him, an open folder in her hands. She waits for him to notice her, but he’s too absorbed.

LOLA

Carl.

CARL yelps and spins, tosses the pencil stub at his garbage can, misses the can, retrieves the stub from the floor, and drops it into the can.

CARL

Lola! Yes, uh, yes, I’m sorry, what —

LOLA

I need your help.

CARL

You . . . you what?

LOLA

You’re the science expert around here, can you look at —

CARL

I would hardly call myself —

LOLA

I’m going over the Omega Man feature, and, I don’t know. Some of it sounds a little . . . silly.

CARL

Silly? The most powerful man on the planet?

(nervous whisper)

You know he might be able to hear you?

LOLA

This bit about how some “magical sorcerer” gave him his “Omega” powers? He says a secret word and a lightning bolt strikes him?

Beat.

CARL

What’s silly about that?

LOLA

Where does the lightning bolt come from?

Beat.

CARL

The sky.

LOLA

But the main current, the part of lightning you see, it travels up from the ground, not down to it. Wouldn’t it make more sense if the bolt came out of him? With the release of some kind of artificially contained energy. It must build up while he’s passing as human.

CARL

Passing? You make it sound like he’s trying to trick us.

LOLA

He is. When he’s in his human disguise. What if the “magic word” is only psychological? A post-hypnotic trigger?

CARL

That’s crazy, Lola. Next thing you’ll be saying that, that Amazonia isn’t really an Amazon.

LOLA

A lost city of woman warriors hidden in Antarctica? How come nobody’s ever found it?

CARL

It’s Antarctica. People don’t go wandering —

LOLA

But satellites? The military’s never sent jets to locate it?

CARL

The government would never do that! They respect her too much, her and all the superheroes. They need them to protect us. We’d be lost without them.

LOLA

Exactly. They’re invaluable. Like, like the police or, or nuclear deterrents. Superheroes are just ICBM’s. Only with free will. Bombs with brains.

CARL

That’s not a very nice way to think —

LOLA

What if the U.S. nuclear arsenal woke up one morning and decided it didn’t want to work for the United States anymore? What if they decided to take a day off? What do you think the government would say to that?

CARL

The Power League would never abandon America. Omega Man has dedicated his entire life to serving truth and justice and —

LOLA

But why?

CARL

What do you mean why? Because . . . because . . . he can’t help it. He’s a good person.

LOLA

No, he’s not. He’s not a person at all. Good or bad.

CY has stopped working as he listens. ROGER pops up from the floor where he’s been scouring the rug for his rings.

CY

Huh. I never thought of it like that. Omega Man, Cyborg, any of them, they could just up and quit any time they like. What could the government do?

CARL

But they wouldn’t! They’re superheroes. That’s what makes them super!

LOLA

I thought their powers made them super.

ROGER

(unconsciously winding a rubber band around his ring finger)