Chris Gavaler's Blog, page 56

December 28, 2015

Analyzing Comics 101: Rhetorical Framing

I’m stealing an idea from Thierry Groensteen, from his 2013 book Comics and Narration. After discussing “regular page layout” (pages with rigid panel grids), Groensteen describes “rhetorical layout, where the size (and sometimes the shape) of each frame is adapted to the content, to the subject matter of the panel.” Groensteen then goes on to talk about the relationships of panels to each other, especially “irregular” layouts that have “no basic structure,” but he doesn’t talk much about subject matter. So his “rhetorical” layout may be the same as any “irregular” layout, in which case the term is superfluous.

Except his definition, “the size (and sometimes the shape) of each frame is adapted to the content,” is really useful. But it doesn’t define a type of layout. It defines a type of framing. In fact, it defines all types of framing, since a frame always has some sort of relationship to its subject matter. And this is true whether panels follow a rigid grid or if the layout is irregular, because the rhetoric has to be analyzed one panel at a time.

So let me offer additions to Groensteen’s term.

Framing rhetoric: the size and shape relationships between frame and subject.

Symmetrical framing: the subject and frame are similar shapes.

Symmetrical and proportionate: the subject and frame are similar shapes, and the subject fits inside the frame; because content and frame are balanced in both size and shape, the effect draws no attention to their relationship and so appears neutral.

Symmetrical and expansive: the subject and frame are similar shapes, but the subject matter is smaller than the frame, so the panel includes surrounding content. The effect is spacious.

Symmetrical and abridged: the subject and frame are similar shapes, but the subject is larger, so the frame appears to crop out some of the subject. The effect is cramped, as if the subject has been sized too small.

Symmetrical and broken: the subject and frame are similar shapes, but the subject is larger, with elements of the subject extending beyond the frame. The frame-breaking elements are often in movement or otherwise expressing energy, implying that the subject is more powerful or significant than the frame.

Symmetrical and off-centered: although the subject and frame are similar shapes and the subject appears as if it could fit the frame, the frame appears to crop out some of the subject while also including surrounding content. The effect is of a misaimed camera.

Asymmetrical framing: the subject and the frame are dissimilar shapes.

Asymmetrical and proportionate: although the subject fits inside the frame, because of their dissimilar shapes the panel includes surrounding content.

Asymmetrical and expansive: because the subject is smaller than the frame, the panel includes surrounding content, and because of their dissimilar shapes, the panel also includes additional surrounding content.

Asymmetrical and abridged: the subject is larger than the frame in one dimension, creating the impression of the frame cropping out content, and because of their dissimilar shapes, the panel also includes surrounding content. The effect is an image placed in the wrong shaped panel.

Asymmetrical and broken: the subject is larger than the frame, with elements of the subject extending beyond the frame edge; because of their dissimilar shapes, the frame-breaking elements further emphasize imbalance.

Asymmetrical and off-centered: although the subject appears as if it could fit inside the frame, the frame appears to crop out some of the subject while including some surrounding content; and because of their dissimilar shapes, the panel also includes additional surrounding content. The effect is of a misaimed camera.

Unframed image: an image with no frame. (Duh!)

Secondary frame: surrounding panel frames border an unframed panel.

Implied frame: an unframed image implies a symmetrical and proportionate frame, while usually remaining inside its undrawn borders.

Interpenetrating images: adjacent unframed images and their implied frames overlap.

Secondary frames, implied frames, and interpenetrating images may be analyzed in the same rhetorical relationships of size and shape as framed images.

That’s all really abstract, so check out some examples:

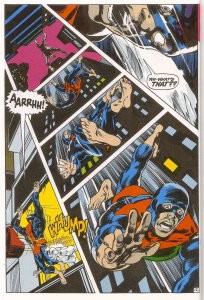

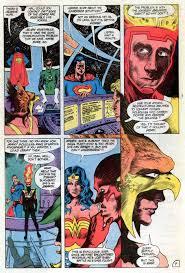

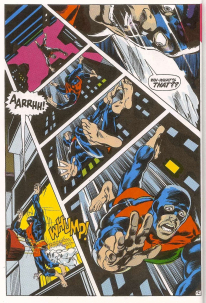

Nick Fury’s body fits inside the full-height column but intrudes into the second column. The unframed panel is symmetrical and broken.

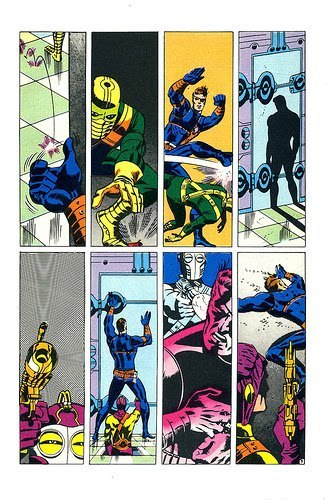

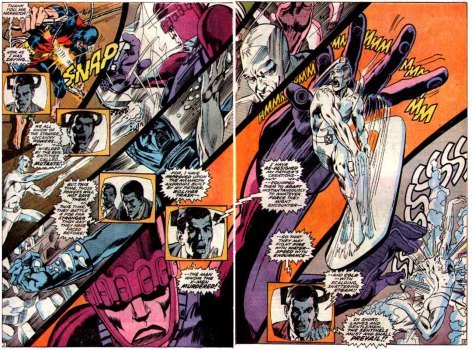

With the exception of the top right close-up, each panel shows Beast’s whole (or nearly whole) body, which is drawn to fill the shape of the panel, and so is symmetrical and proportionate.

Wolverine’s body, however, does not entirely fit; his feet, part of his arm, and the top of his head are cropped. The column panel is symmetrical and abridged.

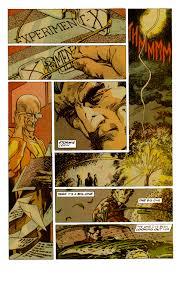

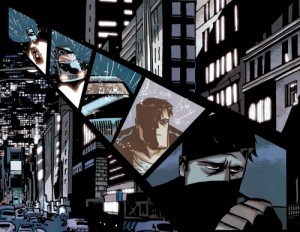

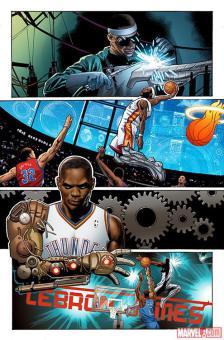

The top panel is symmetrical and proportionate. The second panel crops the face (part of the lower lip and both eyebrows are missing) but includes a lot of surrounding space. The panel is asymmetrical and abridged, as is the third. The last is symmetrical and proportionate again.

The first panel is asymmetrical and proportionate (or off-centered depending on whether you consider his elbow primary content). The second column is drawn as if too thin to contain all of Flash’s face, so the panel is asymmetrical and abridged. The last is asymmetrical and expansive.

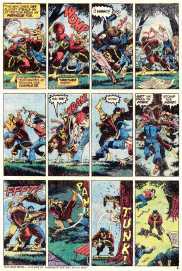

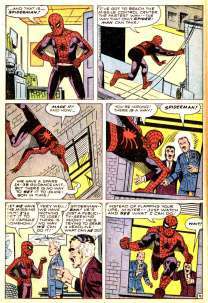

The top panel is asymmetrical and expansive, with detailed elements of the wall in the foreground. The bottom left panel contains Spider-Man, but with ample additional space around the figure, so that non-essential elements of the city landscape are included in the frame. The panel is symmetrical and expansive.

The bottom, page-width panel includes its two primary subjects, Batman and Alfred on the balcony behind him, but the angle and distance includes additional content, including the entire moon, distant buildings, and the wall below the balcony. The panel is symmetrical and expansive.

The second row includes a face with a corner of an eye and mouth cut off. The panel, however, is large enough to include those complete features, but the subject has been drawn off-center to produce the cropping effect. The panel is symmetrical and off-center.

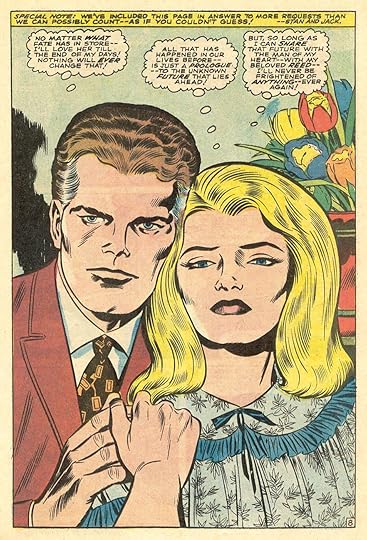

The face in the bottom left panel is cut off at the mouth, even though the subject matter could be drawn higher in the panel to include the entire mouth. The panel is symmetrical and off-centered.

The top right panel content could be composed to include Cyclops’ face, but instead his head is more than half out of frame. The panel is symmetrical and off-centered.

The top panel is wide like the subject matter of the street and so is symmetrical and proportionate. The subject matter of the second frame (the heads of the passenger and the driver visible through the car window) fit the frame, but the frame shape extends to the left to include the reflection of a building in a backseat window, so the panel is asymmetrical and proportionate.

,

,

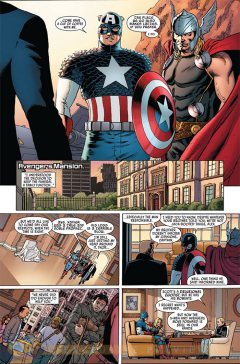

The width of the second panel of “Avengers Mansion” also includes several distant buildings, the front yard, and fence–elements included as if the wide panel shape requires a view of more than the primary subject of the mansion front. The panel is asymmetrical and proportionate.

Not only is the subject of the Hulk much smaller than the frame, the frame itself is shaped so that it must include more than the subject. The panel is asymmetrical and expansive.

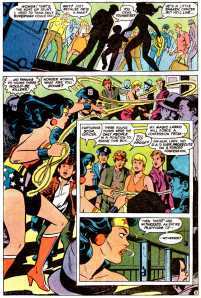

The shape of the full-width panels of the second and third rows extend beyond the subject of the two figures. The panels are asymmetrical and expansive.

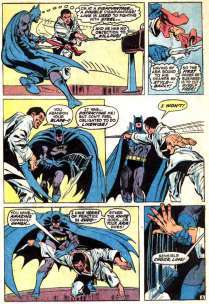

Batman’s leg extends beyond the frame, as if his movement was too fast for the frame to capture. The hand in the final frame also breaks the panel border, again emphasizing action. The panel is asymmetrical and broken.

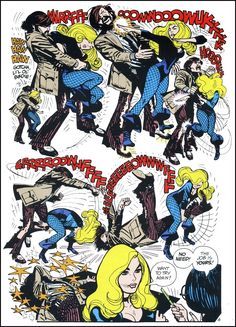

Every panel of the fight scene but the last is symmetrical and broken. The last is symmetrical and off-centered, cutting off Bucky’s chin while leaving space above his head.

The second row begins with a symmetrical and expansive panel; the second panel is symmetrical and proportionate; and the third symmetrical and abridged. The sequence suggests physical and psychological intensification, but exclusively through framing since the Hulk’s expression remains essentially unchanged.

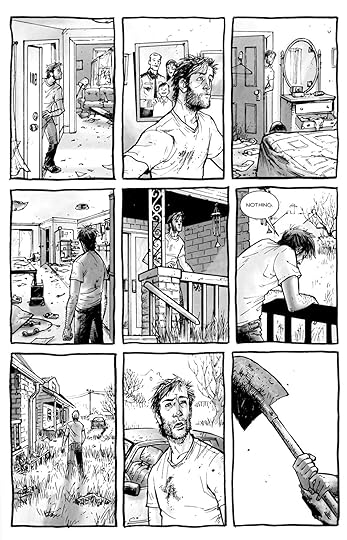

The first panel of a figure stepping through a door is symmetrical and proportionate. The next symmetrical but expansive panel includes its subject matter (the individuals in the classroom and the classroom itself) but also the darkened top of (presumably) a bookshelf. The spaciousness contrasts the cramped effect of the subsequent panels which are mostly asymmetrical and abridged, except for the second which is symmetrical and abridged.

And, on a last note, I intend to use framing rhetoric instead of film terms for camera distance (close-up, medium shot, etc.), because the film terms don’t account for frame shape (in film the frame shape typically does not change). Also, “camera distance” doesn’t suit a drawn image because there is no camera and so no distance between it and the subject; there’s just the subject and the frame.

December 22, 2015

The Rhyming Dead (Analyzing Comics 101: Page Schemes)

The Walking Dead Volume 1 “Days Gone Bye” is anti-feminist, anti-government, pro-gun, libertarian fantasy propaganda. So pretty much my opposite on the political spectrum. And yet I teach it every year in my first-year writing seminar. It helps that it pairs so well with George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (which is nihilistic, anti-everything fantasy propaganda). It helps even more that I like the Walking Dead TV show so much. I always assign open essay topics, so I get a range of gender critiques, pro-family analysis, and (my favorite) the meaning of Rick’s hat. That one requires a deeper level of visual analysis, and that’s what I want to focus on today.

On a previous blog, I laid out my thoughts on layout, and now I want to apply them a little more systematically to one specific comic: The Walking Dead #1 (October 2003) by Robert Kirkman and Tony Moore. I’ll work through the issue page-by-page first, then follow up with a page scheme analysis: how the layouts of separate pages combine for issue-wide effects. I’m working with the general principle that pages have base patterns, and when those patterns repeat, their pages relate at a formal level (they visually rhyme) and so the content of those pages are connected too.

PAGE 1:

Those panel heights vary only slightly, so I would call it a regular 4-row layout, with top and bottom full-width panels. The bottom panel is also unframed and merges with the underlying page panel, giving it additional significance.

PAGES 2-3:

Full-page panel and a regular 3×3. Often a comic establishes a single base pattern, but the 3×3 contradicts the 4-row (and the implied 4×2) of page one. The full-page panel is ambiguous since it can divide into any layout pattern, and so it is an effective bridge between the two base patterns.

PAGES 4-5:

The regular 3-row begins with 3 panels, but then switches to a 2-panel bottom row that breaks the 3×3 pattern established on the previous page. The next page is also a 3-row, but since the top, full-width panel could divide into three panels, I’d say the page is still using 3×3 as its implied base pattern.

PAGES 6-7:

Another full-page panel (on the left side of the spread like the full-page panel of page two, so the positioning rhymes as well) and another regular 3-row with a top, full-width panel that implies a 3×3 base pattern, same as page five (which was also on the right side of the page spread, so another positioning rhyme).

PAGES 8-9:

And here Moore and Kirkman completely break any base patterning. The bottom row would suit a 3×3, but the top two-thirds shift to a regular 2-column layout, with the first column combing three panels to establish the reading path for the paneled second column (what I would call paired sub-columns). The next page then switches back to a regular 3-row. The top, full-width panel is unframed and merges with the underlying page panel which slowly darkens to black gutters, a motif continued on the next page.

PAGES 10-11:

Another atypical page, an irregular 3-row but now with a bottom, 4-panel row, which is a new layout element. Like the preceding page, the top, full-width panel is unframed and merges with the page panel which darkens to black gutters again. The next page returns to a regular 3×3, same as page three.

PAGES 12-13:

A regular 3-row and implied 3×3, since both the top unframed full-width panel and the middle framed full-width panel would divide accordingly. The implied 3×3 is further suggested by the actual 3×3 of the facing page.

PAGES 14-15:

Atypical again: an irregular 2-row. The bottom row partly evokes 3×3, but the panels are closer to half-page height, and they are also insets over the full-page panel image that dominates the top half of the page. The next page is a regular 3-row, though now with a bottom, 4-panel row (as first seen on page ten).

PAGES 16-17:

Two regular 3-row pages, with a total of three full-width panels, two 3-panel rows, and one 2-panel row. (That all black background at the bottom of 16 is interesting, but not part of today’s focus.)

PAGES 18-19:

More regular 3-rows, with three 3-panel rows, two full-widths, and one 2-panel. The second page repeats the exact layout of pages five and seven, with a top, full-width implying the 3×3.

PAGES 20-21:

Two more regular 3-rows with an implied 3×3 base. The first page repeats page nineteen, seven, and five, and the second partially echoes page fourteen (irregular 2-row), though here the top two-thirds of the page fit a 3×3 pattern by combining two implied rows into a single unframed panel. Also the bottom panels are insets over the full-page panel which darkens into black gutters–so close to page fourteen, but not an exact match, more of a slant rhyme.

PAGES 22-23:

The fifth iteration of a regular 3-row with a 3×3-implying top full-width panel. The second page’s 4-row also brings back the implied 4×4 of page one, now with black gutters.

PAGE 24:

Mostly a roughly regular 4-row, except the first panels of the first two rows are combined into a single sub-column, the only column seen since page eight. This is also the sixth page to include black gutters.

So how does any of this combine into any meaningful analysis?

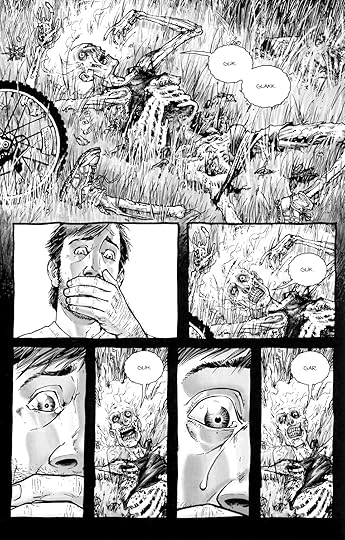

Since well over half of the pages (fourteen or fifteen depending on how you feel about page twenty-one) are regular 3-rows, there’s a dominant base pattern. Eleven of those pages follow a flexible 3×3, and the two full-page panels can be added to that count too. Those two full-pages deserve special attention, rhyming the two formally largest moments in the narrative layout: Rick waking up for the first time after his apocalypse-triggering injury, and the first, apocalypse-signifying depiction of zombies. Pages fourteen and twenty-one are the next visually significant, with their top panels dominating more than half of their layouts: Rick being struck by a shovel, and a zombie appearing behind a fence. Frankly, the shovel shot seems a bit gratuitous to me since the moment is not that narratively important (a character-introducing misunderstanding patched up by the next page), but page twenty-one is key to Rick’s development since he learns not to waste a bullet by killing a zombie unnecessarily, setting up his character-defining mercy killing on the concluding pages. The two concluding pages also rhyme with page one, creating implied 4×2 bookends to the issue. The black gutter motif also begins on pages nine and ten, when the bicycling zombie is introduced, further linking to page twenty-one’s black gutters and harmless zombie.

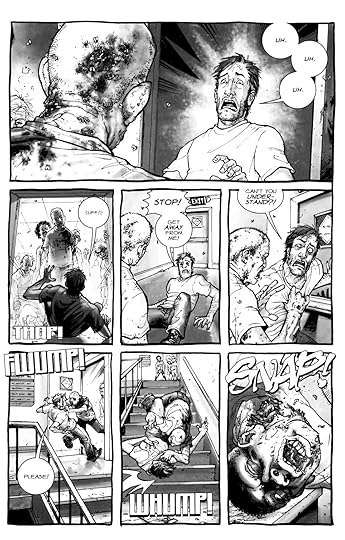

And now that I look at those two half-page columns on pages eight and twenty-four again, I realize they are the only two times that Rick kills a zombie. Both times the zombie is beneath or below him, with its head lowest in the frame. An action-produced sound effect–WHUMP! and BLAM!–partially cover Rick both times too. But in the first panel Rick’s zombie-killing action is accidental, and his full body is shown upside down as he tumbles down the stairs. The second time it’s deeply intentional, and Rick’s full body is rigid and right side up–a complete visual and thematic reversal. Also, the first panel is unframed, and the second is framed by black gutters, further accentuating the contrast and perhaps suggesting the change in Rick’s mental state too–open naiveté to dark conviction? Those two sub-columns are formally unique, literally shaping their two equally unique narrative moments and so drawing a contrast that would be lost if the story were drawn in identically sized and shaped panels.

So the page scheme presents Rick’s character development in different ways than just the words and image content. There are other angles of interpretation available here (I’d tackle all of those top full-width panels next), but the point is that layout doesn’t simply transmit narrative. The formal qualities amplify the narrative, adding meanings and relating moments that in terms of story alone are not linked.

December 14, 2015

Why Darth Vader is My Favorite Superhero

Okay, maybe not favorite, but as far as morally ambiguous asthmatic cyborgs go, Anakin Skywalker is at the very top.

If you doubt his superhero creds, do the checklist yourself. Superpowers? That lightsaber would be plenty, but he could also go head-to-baldhead with Professor X in a telekinetic wrestling match. Secret double identity? Vader/Skywalker is self-explanatory, and if it wasn’t a secret there’d be no Episode 5 shocker: “Luke, I’m your father!” Masked costume? Can’t get more masked than a grill-mouthed, aviator-lensed Samurai helmet. Plus he struts around in a cape.

Of course the main objection to Vader joining the Guardians of the Far Far Away Galaxy isn’t wardrobe or weapon related. It’s his mission: eradicate all Jedi knights, his Galaxy’s actual Guardians. In fact, it would seem to put him near the top of the supervillain roster, just under his evil mentor, Emperor Palpatine.

But Anakin was born with a larger mission: to bring balance to the universe. He is the highest manifestation of the Force, the immaculately conceived uber-child of the midi-cholorians, those symbiotic lifeforms that surge in the cells of all Jedis. In fact, he has the highest midi-cholorian blood count ever recorded, 20,000 per cell, eight times higher than the 2,500 of mere humans (yeah, I couldn’t stomach Episode One either).

So Anakin is the Chosen One, the guy foretold by ancient legend—basically King Arthur or a laser-wielding Jesus Christ. But what exactly does the prophecy mean? According to the Jedi, those evil Sith lords throw the Force off-balance and so it’s a Jedi’s duty to battle them. Thus the Chosen One would “destroy the Sith and bring balance to the Force.” Sounds good, but that’s not exactly the happy ending they got.

Episode Three wedges in the unfortunate phrase “the Jedi and then” between “destroy and “the Sith.” Does that mean the Force and its microscopic avatars are all metaphysical morons? Oops. Sorry about the annihilation of your entire Jedi Order. Our bad. Thanks for worshipping us though.

I think the Jedi read their prophecies through Jedi-tinted glasses. I think the Force was tired of them and the Sith see-sawing the universe on its back. A never-ending battle between good and evil is fun and all, but after 25,000 years maybe that Manichean match-up starts looking like the problem, not the solution. If war is the enemy, then all warriors, Sith and Jedi alike, are obstacles to peace.

So the Force took things into its microscopic hands, impregnated an unsuspecting slave woman, and released the biggest Force-wielding superhero of them all, letting him and his Sith boss slaughter every Jedi knight in existence, except for his first mentor who chops off three-quarters of his limbs while dunking him in a river of lava, after which his lying boss clamps him into a wheezing cyborg suit. That’s all in the fine print of the Chosen One job description.

Then the Force chills for a couple of decades, letting the Sith-administered Empire explode a few planets and whatnot, until the Chosen One gets around to offing mentor number two, plus himself in the lightning-discharging process, and so finally destroying the conveniently tiny two-guy Sith Order. End of all Force manifestations in the known universe. Balance Accomplished.

That is until the Empire of Disney assumed control of the Lucas Republic and released Darth Abrams on the Star Wars franchise. Episode Seven awakens the Force on December 18th, overturning all of Anakin’s brutally hard work. The guy sacrificed everything for the greater good, and now that little punk son of his, Luke, has been rebuilding the damn Jedi order, throwing the Force off-balance again? If I were a midi-cholorian, I’d be pretty pissed right now!

Although George Lucas originally said he had three trilogies in mind, he later admitted the third was less prophecy and more publicity. The catastrophically bad prequels were always more-or-less part of the implied backstory, but he just thought it sounded cool to say later sequels would parallel the actors’ actual ages. Thus Luke Skywalker and Mark Hamill are both 63 now. That’s adorable and all, but not exactly the premise for a three-film blockbuster extravaganza.

In other words, the Force and the creator of the Force both considered the story over. But director J. J. Abrams is a good choice for beating a dead sci-fi horse back to life. He yanked the Star Trek franchise back into existence too, even dragging the late Leonard Nimoy into his parallel continuum reboot. I expect no less from his reborn Star Wars.

Though I do hope he’s noticed that Mr. Hamill bears more than a little resemblance to Senator Palpatine these days. Could it be mere coincidence that the ex-Jedi has made a post-Star Wars career voicing animated supervillains, including that uber-Sith Lord, the Joker?

Sadly, the universe’s greatest superhero, Darth Vader, won’t be there to save the day again.

December 7, 2015

Analyzing Comics 101 (Layout)

The downside to teaching a course on comics is discovering that no textbook quite matches the way you want to teach it. The upside is writing the textbook yourself. And so here’s the first draft of an intended series of “Analyzing Comics 101” blogs. My actual course is called “Superhero Comics,” but I’m hoping this will be useful to other students, teachers, fans, etc.

So here goes . . .

ANALYZING LAYOUT

Layout: the arrangement of images on a page, usually in discreet panels (frames of any shape, though typically rectangular) with gutters (white space) between them, though images may also be insets or interpenetrating images. Page layouts influence the way images interact by controlling their number, shapes, sizes, and arrangement on the page, giving more meaning to the images than they would have if viewed individually. Layouts are the most distinctive and defining element of graphic narratives.

Layouts tend to be designed and read in one of two ways, in rows or in columns.

Rows: panels are read horizontally (and from left to right for Anglophone comics, but right to left for Manga). Types of row layouts include:

Regular 2×2, 2×3, etc.; 3×2, 3×3, etc.; 4×2, 4×3, etc.: vertical panel edges line-up, creating uniform panels in all rows. If the vertical and horizontal edge both line-up, the layout is a grid. 3×3, 3×2, and 4×2 are the most common grids.

3×3:

3×2:

4×2:

2×3:

2×4:

4×3:

3×4:

4×4:

Irregular 2-row, 3-row, 4-row, etc.: vertical panel edges do not line-up, creating a different number of or differently sized panels in one or more rows. Horizontal panel edges may or may not line-up. Irregularities include a full-width panel, which extends horizontally across the whole page, or rows divided into 2, 3, 4 or more panels. Irregular 3-row layouts are among the most common layouts in comics, followed by 4-row and 2-row.

3-row:

[image error]

4-row:

2-row:

Columns: panels are read vertically, from top to bottom. Because of the Anglophone tendency to read horizontally before vertically, columns are less common in Anglophone comics. Column layouts include:

Regular 1×2, 1×3, 1×4, etc.; 2×2, 2×3, 2×4, etc.; 3×2, 3×3, 3×4, etc.: horizontal panel edges line-up, creating uniform panels in all columns. To counter horizontal reading norms, columns often use one or more full-height panels, which extends vertically down the whole page. The absence of segmented panels within a full-height panel column reduces establishes the column layout, preventing a horizontal reading path.

1×4:

1×3:

1×2:

Irregular 2-column, 3-column, 4-column, etc.: horizontal panel edges do not line-up, creating a different number of or differently sized panels in one or more columns. Because horizontal reading is an accepted default, segmented columns tend to be irregular, with one or more taller panels breaking the left to right norm. Often a single, full-height panel establishes an irregular 2-column layout, with the second column divided into multiple panels. Irregular 2-column are the most common column layouts.

2-column (with establishing full-height panel):

Row and column patterns, however, are indistinguishable without content to determine reading direction. A 4×2 layout, for example, may be read as four rows divided into two panels each, or it may be read as two columns divided into four panels each. However, because Z-path reading (first right then down) is the norm for Anglophone comics, 4×2 is typically read as a 4-row layout not a 2-column.

Rows and columns can also be merged by including only full-width panels within a single column.

3×1:

4×1:

5×1:

6×1:

Combinations: panels must be read both horizontally and vertically, combining rows and columns on a single page. In practice, combination layouts are always irregular. Common combination layouts feature one or more paired sub-columns (one sub-column divided into two panels, the other the height of those two panels combined, with the two sub-columns sequenced in either order) or a single, full-height column in an otherwise row-patterned layout.

If a row of three or more panels occupies half or more of the page, the panels are effectively columns, though they do not break the horizontal reading path.

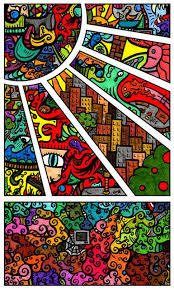

Diagonal layouts: panels do not follow vertical or horizontal divisions, and so are neither clearly rows nor columns:

Diagnals may also intersect:

Caption panel: a panel that contains only words. These tend to be smaller, subdivided panels.

Inset: a panel surrounded entirely by another image.

Overlapping panels: a framed panel edge appears to intrude into or to be placed over top another framed panel, with no gutter dividing them.

Broken Frames: image elements of one panel extend beyond its frame into the gutter and/or into the frame of an adjacent panel.

Insets, overlapping panels, and broken frames are often combined:

Interpenetrating images: two or more unframed images with no distinct gutters or borders so that elements of separate images appear to overlap.

Page panel: A page-sized panel, typically visible in the gutters between smaller panels. When white, black, or otherwise uniform, the page panel appears as the page itself and so as a neutral space outside of the actions and events of the drawn images. All other panels are insets superimposed over the page panel. If the page panel includes drawn images, those images should be understood as the underlying and so in some way dominating background element to all other images on the page. If one panel is unframed, its content may be understood as part of the larger page panel.

A page panel with no insets and a single unified image is a full-page panel:

A full-page panel with author credits is a splash page.

Two-page panel: two facing pages designed to be read as a unit. A two-page spread are two facing pages not designed as a unit.

Panel accentuation: a panel may be formally differentiated and therefore given greater importance by its size, frame (including shape, thickness, and color, and by being unframed) or position on the page (first, center, and last panels tend to dominate).

Panels accentuated by border shapes:

Base Layout Pattern: a panel arrangement repeated on multiple pages.

Strict: repetitions from page to page contain no variations in a base pattern.

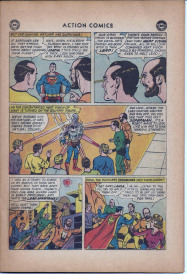

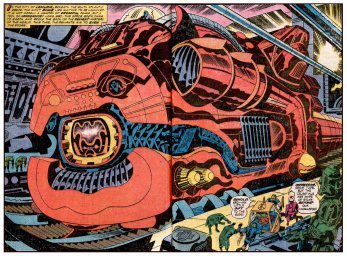

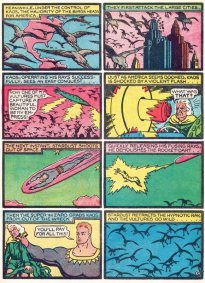

For the Superman episode of Action Comics #10, Joe Shuster uses a strict 4×2, as does Fletcher Hanks for “Stardust the Super Wizard” in Fantastic Comics #12:

Flexible: some variations, especially through combined panels and divided panels. Often the base pattern is only implied.

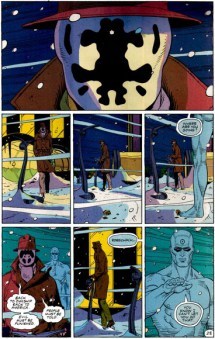

Watchmen is the best known example of a flexible 3×3 base pattern:

[image error]

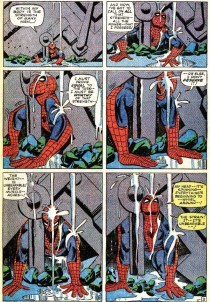

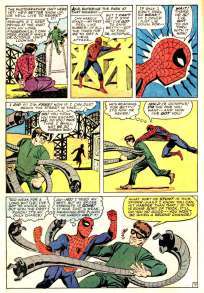

Comics more often use a flexible 3-row base pattern. Steve Ditko fluctuates between rows of three panels and rows of two panels in Amazing Spider-Man:

.

.

Irregular: no base pattern.

The Avengers #174 fluctuates between 3-row and 4-row layouts:

If more than one arrangement repeats, each pattern may be distinguished descriptively (3×3, 2-column, etc.) or by chronological appearance (layout A, B, C, etc.). Pages that repeat earlier layouts may be said to rhyme. A comic book’s page scheme may be analyzed for layout repetitions, creating a page scheme. But let’s save that topic for later . . .

November 30, 2015

Supermen Before Superman, Vol. 1

Superheroes didn’t begin in June 1938 with Action Comics #1. They didn’t begin with Superman’s crime-busting predecessors of the 1930s pulps either. Superheroes have a sprawling, action-packed history that predates the Man of Tomorrow by decades.

A century before Krypton exploded, the Grey Champion was confronting redcoats in the streets of colonial New England, while the monstrous Jibbenainosay scourged the Kentucky frontier. Spring-Heeled Jack was leaping English stagecoaches in single bounds as Dr. Hesselius administered to the victims of vampire attacks. Add to this Victorian League of Justice the super-detective Nick Carter, a man with the strength of three, surpassed only by Tarzan’s jungle-perfected physique and the Night Wind’s preternatural speed and crowbar-knotting muscles. While the Scarlet Pimpernel was assuming his thousand disguises, the reformed Grey Seal and Jimmy Valentine were turning their criminal prowess to good as modern Robin Hoods.

By 1914—the year Superman’s creators were born—the superhero’s most defining characteristics were already long-rehearsed standards. Secret identities, costumes, iconic symbols, origin stories, superpowers, these are all the domain of the first superheroes. Some of these very earliest incarnations are startling full-blown, some reveal fragmentary foreshadowing, but all are essential to understanding the century-long evolution of the formula that did not begin with but culminated in Superman.

I cover this terrain in On the Origin of Superheroes, but readers should explore it for themselves. So here’s a tentative Table of Contents for “Supermen Before Superman, Vol. 1, (1816-1916)” a would-be collection of the original 19th and early 20th century essentials:

1. Manfred, Lord Byron 1816

Though the poetry-spouting “Magian” isn’t the first sorcerer of adventure lore, he is the first to embody the moral complexity of the post-Napoleonic anti-ish hero type (and, yes, he has sex with his sister).

2. “The Gray Champion,” Nathaniel Hawthorne, 1835

An old, craggy-looking guy, but a great rabble-rouser. His superpower is inspiration! (Also, his literary sister, Hester Prynne, is the first character to sport an identity-defining letter on her chest.)

3. Sheppard Lee, Robert Montgomery Bird, 1836

The guy’s soul can change bodies. Just give him a non-moldy corpse and he’s good to go.

4. Nick of the Woods, Chapters III and IV, Robert M. Bird, 1837

A homicidal schizophrenic hell-bent on murdering Indians in the spirit of Manifest Destiny. He’s Batman in buckskins.

5. “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” Edgar Allan Poe, 1841

The proto-Sherlock and so the original super-detective.

6. The Count of Monte Cristo (excerpt), Alexandre Dumas and Auguste Maquet, 1844

A wrong-avenging master-of-disguise passing along the racial divide, what’s not to cheer?

7. Les Miserables (excerpt), Victor Hugo, 1862

The guy can pick-up a horse-cart single-handedly. I think it was radiation from the social Gamma bomb of the French Revolution.

8. Green Tea, Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu, 1872

The original occult detective, with a lethal dose of Orientalism.

9. “How Robin Hood Came to Be an Outlaw,” from The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood, Howard Pyle, 1883

Yep, Robin Hood. The original noble outlaw.

10 .Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Friedrich Nietzsche, 1883

Nothing superheroic about the ubermensch, but he is the genre’s namesake.

11. Spring-Heeled Jack, the Terror of London, Alfred S. Burrage, 1885

The first Bat-Man, plus the guy has a magic boot and dresses like Mephistopheles.

12. Nick Carter, Detective: The Solution of a Remarkable Case, Frederic van Rennselaer Dey, 1891

Some Captain American level super-strength here, but mostly bare-knuckled detection. No sitting around solving crimes from your French hotel room.

13. “The Ides of March,” E. W. Hornung, 1891

The original Sherlock-flouting gentleman thief, whose spawned a legion of do-gooding imitators.

14. “A Retrieved Reformation,” O. Henry, 1903

More of a supervillain again, but check-out the tropes: alias, dual identity, self-sacrifice, signature skill.

15. “The Hunt for the Animal,” “The Fiery Cross,” from The Clansman, Thomas Dixon, 1904

Okay, this one I deeply apologize for, but (as I’ve discussed plenty elsewhere), he defines the genre.

16. Man and Superman, George Barnard Shaw, 1904

Again, can’t ignore the translated source of the genre namesake.

17. “Paris: September, 1792,” chapter from The Scarlet Pimpernel, Emmuska Orczy, 1905

Just another cross-dressing socialite secretly using his wealth for aristocratic good.

18. “The Nemesis of Fire,” Algernon Blackwood, from John Silence, Physician Extraordinary, 1908

The first occult detective with occult powers–even if he is more sympathetic to werewolves and Egyptian fire demons than the moronic Brits they haunt.

19. Under the Moons of Mars, Edgar Rice Burroughs, 1912

Find yourself on a mysterious alien planet that gives you super-strength, sound familiar?

20. “The Height of Civilization,” chapter from Tarzan of the Apes, Edgar Rice Burroughs, 1912

First pulp hero actually called a “superman.”

21. “A Midnight Incident,” “The Frame-up,” “A Law Unto Himself,” chapters from Alias the Night Wind, Frederic van Rennselaer Dey, 1913

The first mutant, a cross between Quicksilver and the crowbar-bender of your choice.

24. “The Gray Seal,” Frank L. Packard, 1914

His fingertips seem to have mutant sensitivity, but mostly he’s another urban Robin Hood.

25. Herland, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, 1915

Paradise Island minus Wonder Woman (and the yellow wallpaper).

26. Doctor Syn: A Tale of the Romney Marsh, Russell Thorndike, 1915

A vicar by day, Scarecrow-costumed avenger by night, plus there’s that whole pirate backstory and prequels.

27. The Iron Claw, Arthur Stringer, 1916

The movie is lost, but the Laughing Mask still debuted in newspaper at the time, doing his mild-mannered routine with his boss and fiance while secretly fighting criminals at night.

Okay, so maybe that’s more one volume’s worth of texts, but this is still in the dream-book stage, and with the magic of unpaperbound e-books, why not?

November 23, 2015

Frankenstein Begins: The Dark Superhero Rises

I used to be a lone voice in the pop culture wilderness crying that Frankenstein should be refitted with a cape, tights, and an “F” on his chest. More oddly, I think the wardrobe change would fit equally to the doctor, Victor Frankenstein, as his creation, the Frankenstein monster. But I’m no longer so lonely in my wailings. Opening November 25, Victor Frankenstein makes the case for me.

Personally, I would have called the prequel Igor—since that’s its hook. Former Harry Potter super-wizard Daniel Radcliffe plays the mad scientist’s hunchback lab assistant. You may or may not agree that Harry is himself a superhero (muggle by day, transformed by accident, etc.), but James McAvoy is a no-brainer: the titular Doctor shares bodies with the X-Men’s super-brained Professor Xavier. The young version. McAvoy retains his pre-Patrick Stewart scalp.

Attached to those superhero creds, director Paul McGuigan makes his leap to the big screen in a single bound from the BBC’s Sherlock. For his new dynamic duo, Igor plays Dr. Watson to Victor’s Holmes. Plus actress Jessica Brown Findlay had the power of mind-control on the British superhero show Misfits. If that’s not already a complete body of superhero parts, screenwriter Max Landis cut his teeth on 2012’s Chronicle and the 2011 comic short The Death and Return of Superman.

But how are Superman and (either) Frankenstein related?

Well, the creature did play a gig as a Marvel superhero in the 70s. He teamed-up with Spider-Man, Iron Man and She-Hulk—though the supervillain Kang the Conqueror used him as a mind-controlled minion too (perhaps both McAvoy and Findlay could help him with that?). But Frankenstein and Superman were stitched together before comics even existed. In the 1919 film serial The Master Mystery, Harry Houdini battles Q the Automaton, a robot described as a “Frankenstein” that “possesses a human brain which has been transplanted into it and made to guide it” as a “conscienceless inhuman superman.”

That man of steel wasn’t the Man of Steel, but a pop cultural version of Nietzsche’s ubermensch. The German philosopher prophesied in 1883 that a breed of superhumans would evolve and take the world away from Homo sapiens. Mary Shelley was decades ahead of him. The author of Frankenstein wrote in 1818 that “a race of devils would be propagated upon the earth, who might make the very existence of the species of man a condition precarious and full of terror.” That’s why Victor refuses to make a mate for his monster and why his monster declares himself his and humanity’s “arch-enemy.”

It’s the original Professor X vs. Magneto match-up. Or Superman vs. Lex Luthor, since Victor is also the original mad scientist, a character type so pervasive in comics it’s hard to keep track of them all. Like Victor, they’re usually a good guy who accidentally creates a monster—though, unlike Victor, the monster tends to be themselves.

The Dr. Jekyll/Frankenstein merger culminated with Reed Richards when he transformed himself and his pals into the Fantastic Four. The Thing was so popular, Marvel created the Hulk next—fulfilling the Shelley/Nietzsche prophesy of an expanding race of monstrous supermen. When Bruce Banner turned into the Hulk for the first, artist Jack Kirby drew a Boris Karloff knock-off with a flat head and grey skin (Marvel flipped to a green complexion the next issue because the ink looked better).

Karloff’s stitched corpse was never part of Shelley’s plan though. Her Victor doesn’t even know how to reanimate flesh: “I might in process of time (although I now found it impossible) renew life where death had apparently devoted the body to corruption.” His creature wasn’t human-sized either: “As the minuteness of the parts formed a great hindrance to my speed, I resolved . . . to make the being of a gigantic stature, that is to say, about eight feet in height.”

Early stage productions even draped him in a Greek toga—the first of a new god-like species. His “limbs were in proportion” (a big turn-on for early nineteenth-century readers) and the doctor “had selected his features as beautiful.” Sure, his skin was transparent yellow and his face a fit of twitching muscles, and next he’s serial murdering his creator’s loved ones—but, hey, when has a mad scientist’s scheme ever worked out exactly as planned?

Look at the twitching pile of recent superhero movies that include some nut job trying to take over the planet with a new species of devilishly superior uber-monsters:

Ian McKellen’s Magneto planned his mutant conquest, complaining that “nature is too slow” in the firstX-Men.

Michael Fassbender’s Magneto was still complaining in X-Men: First Class, but under the tutelage of Kevin Bacon: “We are the future of the human race. You and me, son. This world could be ours.”

A month later in the first Captain American film, Hugo Weaving’s Red Skull gave Cap the same lesson: “You pretend to be a simple soldier, but in reality you are just afraid to admit that we have left humanity behind. Unlike you, I embrace it proudly. You could have the power of the gods!”

Weaving’s Agent Smith had already explained to The Matrix fans: “As soon as we started thinking for you, it really became our civilization. Which is of course what this is all about. Evolution. . . . The future is our world.”

Iron Man 3’s supergenius Aldrich Killian wanted to turn himself and his minions into the “new iteration of human evolution.”

Just like Dr. Connors, aka the Lizard, planned to “enhance humanity on an evolutionary scale” and “create a world without weakness.” “This is no longer about curing ills,” he said in The Amazing Spider-Man. “This is about finding perfection.” Unfortunately, “Human beings are weak, pathetic, feeble-minded creatures. Why be human at all when we can be so much more? Faster, stronger, smarter!”

And Dane DeHaan, reading from Max Landis’ Chronicle script, declared himself an “apex predator,” ready to wipe out humankind as Victor Frankenstein had feared his creature’s super-race would.

So who will save us from all these Frankenstein Supermen? Other Frankenstein Superman of course. Captain America, Spider-Man, Iron Man, even the X-Men’s radiation-saturated DNA, they all started as lab experiments. That’s the core of the Marvel superhero formula. Stitch a monster into tights and watch him save us from monsters just like him.

There’s a reason we confuse Victor and his creature. Superheroes are both kinds of Frankensteins.

November 16, 2015

Should a Superhero Have a License to Kill?

James Bond might not be a superhero, but he does dedicate his life to battling bad guys. Plus he has a codename: 007. Yeah, that means he’s just one guy in a league of 00s, so nothing unique—same as any Green Lantern in the intergalactic Green Lantern Corps. Maybe Earth-based agencies are different, but then that would strike Black Widow from the superhero census list too. Also, like Natasha, James has no superpowers, at least not compared to Thor or Superman. He’d make a pretty good match for Batman though. He even sports his own utility belt’s worth of Q-engineered supergadgets.

Mr. Bond also wields Dr. Who’s shapeshifting powers. I watched his edited-for-TV Sean Connery incarnation from my parents’ couch as a kid, and his Roger Moore from theater seats as an adolescent. I even witnessed his awkward Timothy Dalton stage while I was finishing college and his franchise was waiting for Pierce Brosnan to come-of-age too. But I have to admit Daniel Craig is the David Tennant of the Bond universe. I’m looking forward to seeing his current Spectre adventure.

The character struggled after losing his mission-defining Evil Empire, but Skyfall’s Judi Dench gave him back his raison d’être:

“I’m frightened because our enemies are no longer known to us. They do not exist on a map. They’re not nations. They’re individuals. Look around you. Who do you fear? Do you see a face, a uniform, a flag? No. Our world is not more transparent now. It’s all opaque. It’s in the shadows. That’s where we must do battle.”

Batman is all about shadows too, turning the darkness of his parents’ murders against the shady elements of murky Gotham. But, unlike a trigger-happy 00 agent, Batman would never kill anyone on purpose, right?

Well, actually the unlicensed Dark Knight racked up a Bond-level body count during his first year in Detective Comics. Not only did a holster hang from his utility belt back then, the batplane included a mounted machinegun: “Much as I hate to take human life, I’m afraid this time it’s necessary!”

DC editors reined in his homicidal writing staff after Batman #1, but even the comparatively wholesome Superman had a killing streak then. In June 1939, same month Batman was kicking jewel thieves off skyscrapers, Superman was dropping a mobster to an identical death. Granted, it wasn’t Superman’s fault he lost his super grip: “If he hadn’t tried to stab me, he’d be alive now.—But the fate received was exactly what he deserved!” Though what did Superman think was going to happen when he destroyed the Ultra-Humanite’s propeller mid-flight? The supervillain somehow escaped the crash, but no thanks to the death-indifferent Man of Steel.

Comic books usually protect their heroes from having to kill directly. In that same Action Comics, a rotating blade shatters against Superman’s impervious skull and slices up a nearby thug. Or in another early Batman adventure, a “foreign agent” is accidentally impaled on his own sword, and Batman self-righteously declares: “It is better that he should die! He might have sent thousands of others to their death on a battlefield if his plans had been successful!”

If this makes your feel morally queasy, listen to Spider-Man co-creator Steve Ditko on superhero morality: superheroes are “moral avengers” who must kill criminals in order to show “a clear understanding of right and wrong,” even if that means violating the “pervading legal moral” code.

Mr. Ditko currently resides in the crazy-old-man dimension of the comics multiverse, because his Ann Rand philosophy isn’t a page in today’s superhero bible. Batman’s and Superman’s most recent film incarnations take little license with the Sixth Commandment. In fact, the plot of Christopher Nolan’s 2008 The Dark Knight pivots on Christian Bale’s Batman struggling not to kill the Joker—even though killing him is necessary to protect others and exactly “what he deserves.” And remember the fan outrage when Henry Cavill’s Superman snapped General Zod’s neck in Man of Steel? It was that or let the General’s laser vision slice up a family of cowering Metropolitans, but Superman’s super-wholesomeness got sliced up too.

Both Zod and Joker are weirdly suicidal supervillains, goading their arch-enemies into committing murder. But then that’s the point. Superheroes are supposed to oppose killing out of principle. So where’s that leave Mr. Bond?

We could say his license strikes the “super” from his heroness, maybe even replacing it with an “anti.” His comic book counterpart might be the Ditko-esque Punisher, a sometime supervillain depending on who’s penning the story. But in James’ defense, killing isn’t the core of his mission. It’s just the most efficient means for getting important jobs down. He’s paid to be indifferent to death.

And that’s the problem. I remember Roger Moore’s 007 dangling a “foreign agent” by his tie from the edge of a building. The thug had been gunning at him seconds earlier, so the scene meets the “what he deserved” test. But was it necessary? Couldn’t he have holstered his license and knocked the guy out instead of dropping him to his death? Sure, the guy was a cog in the Cold War wheel trying to squash Democracy, but did Roger Moore have to grin? Did the movie have to play the scene for laughs, toying with the villain’s tie as he quivered for life?

I don’t blame his character though. James Bond was designed to be a cold-blooded Cold Warrior. You could argue the hero type was a product of its times—and so a bad fit with ours. Connery, Moore, Dalton, they all performed indifference so their 60s, 70s and 80s audiences could forget about the nuclear arsenal aimed at their hometown theaters. Take Bond out of that context and he just seems callous. The same way the original Superman and Batman made more moral sense as their readers teetered on the brink of a Nazi-driven World War.

The current Daniel Craig incarnation fixes that. He still shows his killer license when needed, but he’s not indifferent about it. He understands what it means to take a life. Like the 2013 Superman, he only snaps a villainous neck when it means saving innocent ones. He takes no pleasure in it. If anything, that hint of inner turmoil makes him almost superheroic. He does the dirty work so no one else has to. He’s not a 00 by self-righteous nature, but by self-sacrificing choice.

November 9, 2015

Is Katniss Everdeen a Superhero?

At first glance, the answer seems pretty obvious: No way! I mean, where’s the mask? What’s her codename? And what about superpowers—strength? flight? speed? The girl can’t even talk to fish. But first glances can be deceiving. Take a sec to adjust your X-Ray Goggles, and you might be surprised what’s under Ms. Everdeen’s seemingly non-superheroic skin.

Let’s start with those superpowers. You don’t need Hulk-like strength or Flash-like speed to join a superhero union. Of course Katniss actress Jennifer Lawrence knows all about mutant shapeshifting from playing Mystique in soon-to-be three X-Men films. In fact, it was 2011’s X-Men: First Class that flung Lawrence’s career into full flight, setting up her even greater success the following year in the first Hunger Games. But even though Lawrence is Katniss, Katniss isn’t Lawrence. Her character has to earn her own super skill set.

Which she does. As a top-notch archer, Katniss would fit into both DC’s and Marvel’s universes. Green Arrow debuted in More Fun Comics back in 1941, and actor Stephen Amell has been having even more fun playing him on the CW series Arrow since 2012. The character started off as a modern-day Robin Hood knock-off, complete with a feather in his goofy tricorne cap—so if nothing else, Katniss wins on fashion points. I say she has the Avengers’ Hawkeye beat too. Iron Man, Captain America, Thor, Hulk, they’ve all had their own franchises. Marvel has been mumbling about Scarlett Johansson staring in a Black Widow movie since 2010, but Hawkeye? Not even actor Jeremy Renner holds out much hope for that starring role. Meanwhile, Katniss hits her fourth bullseye with Mockingjay Part 2.

Okay, but Hawkeye and Green Arrow, like all self-respecting superheroes, wear nifty costumes. And so does Katniss. Tons of them—literally tons if you count that flaming chariot. Hell, she even has her own costume designers. Superman needed Ma Kent to sew his outfit, and the Fantastic Four were hanging out in mufti till Invisible Girl discovers her unexplained fashion powers in issue #3. At least it makes sense that Peter Parker would develop needle-and-thread skills from that radioactive spider bite, but where are all the other superheroes buying their superthreads? Only millionaires can afford a private butler named Alfred to maintain their wardrobes. So thank you Hunger Games for an unexpected nod toward reality.

But the key to a superhero’s costume is the symbol plastered on the chest—a spider, the number “4,” the letter “S,” whatever is literally closest to your superhero heart. For Katniss, that’s her mockingjay pin. It’s her personal symbol, and soon the symbol of the whole rebellion. The bird is also a super-bird, a genetically engineered hybrid that has an almost mystical meaning to those who respect its human-like singing. Like Bruce Wayne’s bat, the mockingjay represents Katniss’s mission, the next checkmark on her superhero trait list.

The two oldest comic book superheroes, Superman and Batman, spelled out two very different but complementary ways of defining a superhero’s reason-to-be: the Man of Steel dedicates himself to serving as a “champion of the oppressed,” while the Dark Knight vows to “war on criminals.” One is about victims, the other villains. Katniss covers both. She champions the oppressed citizens of District 12 while bringing her war to the Capitol. And if you think superheroes can fight their own governments, that tradition is even older than comics. Look at Zorro and Robin Hood. Or the Scarlet Pimpernel’s battles with the France’s Revolutionary government. Even Superman and Batman aren’t shy about roughing up a few wrong-headed cops or army battalions when the greater good is at stake.

Which gets us to motivation. What’s at stake for Katniss? Well, she’s been wronged, and she’s going to fight those wrongs until she’s fixed them. That’s the oldest superhero motivation of them all. Batman best embodies it—he crushes criminals because criminals killed his parents—but Alexander Dumas’ Count of Monte Cristo started exacting his personal revenge on wrong-doers in 1844. Plenty of 1930s pulp heroes started adventuring after the death of a loved one too, including one of the very first superheroines, the Domino Lady: corrupt politicians in league with a KKK splinter group murder her dad, and next she’s pulling on a domino mask and, well, a dress and high heels. Again, Katniss wins on fashion sense. But she also wins additional points for giving the you-killed-my-beloved-family-member trope a much needed revamp. In the Batman formula, Katniss’ sister Primrose would have died in the Games—but Katniss begins her superheroic career not as a too-little too-late reaction to that wrong but instead by preventing it. Imagine if little Bruce Wayne had stopped that mugger in Crime Alley by volunteering for his Batman mission before his parents could be killed. On my scorecard, that makes Katniss better than Batman.

This is all looking pretty good for Super-Katniss, but she is missing some key superhero traits. First off, no secret identity. Of course Hawkeye and Black Widow don’t have ones either. And neither do any of the Fantastic Four. They do all have those fancy codenames though, something else Katniss is missing. But without a secret identity to hide, why does a superhero need a codename? Sure, Hawkeye and Black Widow are S.H.I.E.L.D. agents, but Nick Fury is just Nick Fury. Thor used to be mild-mannered Donald Blake, but Marvel Studios jettisoned his alter ego, so now Thor is just Thor.

So you could argue that codenames and secret identities are no longer a necessary part of the superhero formula. In which case, Katniss is in. But there’s another side to Thor that Katniss lacks. In fact, two sides. He’s a god who trades in Asgard to hang with us humans. If Odin decided to war on Earth, I have no doubt which side his son would fight for. Masks and codenames are important because they embody a superhero’s two-sidedness. You take your superpower-bestowing origin point—Asgard, Krypton, cosmic ray-infested outer space—and use it in service of your human half. Super-heroes are always straddling that perilous hyphen, keeping their two sides in balance. But Katniss is just Katniss.

Though, to be fair, she does have some duality. She performs her Hunger Game persona in front actual cameras, while keeping her true self hidden. You could even say she uses her Capital persona to battle the Capital on behalf of District 12—the same way Batman takes the darkness of Crime Alley and directs it against the cowardly criminals of Gotham. But is that enough to earn Katniss a final make-or-break checkmark on the Superhero Census Bureau Questionnaire?

I’m going to leave that one for you to decide.

The Hunger Games: Mockingjay Part 2 opens November 20.

November 2, 2015

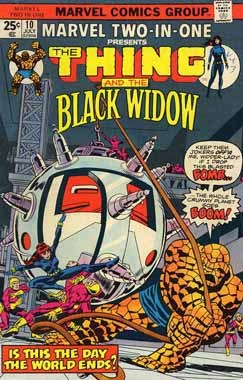

Marvelous Two-in-One Team-Up

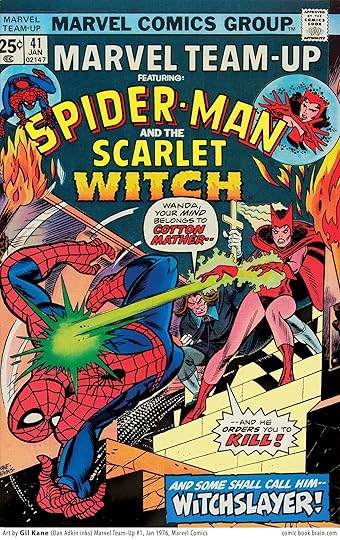

Some of my favorite comics growing up were the oddball superhero pairings Marvel would throw together: Spider-Man and Scarlet Witch, Thing and Black Widow, Thing and, well, Thing (that was an odd issue). So I’m delighted that the marvels of the publishing universe have thrown together my two most anticipated new books with the same fall 2015 release: Lesley Wheeler’s Radioland (Barrow Street Press) and my own On the Origin of Superheroes (University of Iowa Press).

Obviously I’m anticipating my own book. Publishing means organizing readings, reviews, interviews, and every other kind of publicity. But it’s the poetry collection Radioland that I’ve actually looked forward to, that I can now sit back with a pre-release copy in my lap and sincerely admire. I already read it in multiple manuscript print-outs, but there’s nothing quite like the authoritative aura of a glossy-covered book fresh from its publisher’s packaging envelope. I’ve read all of Wheeler’s previous books (her scholarly Voicing American Poetry and The Poetics of Enclosure, and her collections Heathen, Heterotopia, and The Receptions and Other Tales), but Radioland is my current favorite. And not just because I teared up when I opened to the surprise dedication:

for Chris Gavaler

and other good fathers

I should acknowledge that I’m Wheeler’s spouse. We’re professors in the same English department too, so our professional identities team up constantly. But you never know which student or non-departmental colleague is going to give a startled blink at the discovery of our two-in-one domestic life. Aside from our three-sentence wedding invitation, we’ve officially collaborated on only one scholarly article (about poet Marianne Moore) and two children (a first-year in college and a first-year in high school). But our co-editing is invaluable.

After dutifully reading my weekly superhero blog, Wheeler saw me through the surprisingly complex process of rewriting and reorganizing the pre-1938 material into a cohesive manuscript. When an Iowa acquisition editor read the blog and contacted me to ask if I wanted to convert it into a book, I said yes. Obviously. But it was Wheeler who suffered the first drafts of each reconceived chapter, helping me rethink, rework and eventually refine. As I explain in the penultimate paragraph:

Lesley Wheeler has no superhero scholarship I can cite either, but she’s seen me through each step of creation, critiquing everything from the first harebrained draft of that KKK essay to the thorniest midtransformations of this manuscript.

I dedicated my first romantic suspense novel to her (Pretend I’m Not Here is even set in the Virgin Islands where we honeymooned). But On the Origin of Superheroes is dedicated to John Gavaler, my father. He read comics as a kid in the 40s, fueling my comic book reading in the 70s. John is also one of the “other good fathers” of Lesley’s book dedication, a category that, when you read the collection you’ll see, doesn’t include her own. He’s more like the supervillain Nightmare haunting her sleep—no matter how many times she vanquishes him in real life. But her poetic superpowers more than make up for his failings when Radioland single-handedly realigns the universe into a better shape. “Gods and fathers,” her final poem concludes, “rarely signal / but rock vibrates /sympathetically. What else / could it say? Echo / a kind of love . . .”

Wheeler and I also appear together in last year’s superhero poetry collection Drawn to Marvel: Poems from the Comic Books, but our most superheroic successes are our kids. Oddly, that includes standing on the crumbling planet of their childhood and watching them blast away in private rockets. Madeleine is now adventuring in the distant solar system of Connecticut, and Cameron, while still homebound, is tearing Hulk-like through his adolescent wardrobe, poised to make the same single-bound leap into adulthood.

Meanwhile, we have our books. Not as brilliant and hilarious as flesh-and-blood children, but they are easier to read and to hand to a friend. If you’d like to meet them, they’re available for pre-order at Amazon and elsewhere. And, if you’re in Lexington, VA on November 4th, stop by the Bookery. We’ll be there, 5:00-7:00 pm, pens in hand.

October 26, 2015

Supergirl vs. the Marvel Cinematic Universe

I grew up thinking of DC and Marvel as rival teams in a vast, superpowered Olympics. Who’s stronger, Superman or Thor? Who’s faster, Quicksilver or Flash? Every spin of the comics rack was a new exhibition in their never-ending face-off.

That’s why new Supergirl show is such a game-changer. Sure, the character has been around since 1949 (though that “Supergirl” was Queen Lucy from the Latin American kingdom of Borgonia, not Kara Zor-El, Superman’s cousin). Melissa Benoist’s Supergirl looks perfectly fun too. I’m even happy to see CBS back in the superheroine business. They rescued Wonder Woman from cancellation in 1976, before introducing the first live-action incarnations of the very male Marvel pantheon: Spider-Man, Captain America, Doctor Strange, Daredevil, and, one of the most successful superhero shows ever, The Incredible Hulk. We’ll see if Supergirl survives five seasons too.

But aside from its team-switching network, it’s the show’s timeslot that throws the biggest red flag on the DC-Marvel playing field. Mondays at 8:00? That’s when the pre-Batman series Gotham airs. I would shout FOUL! But can you foul your own teammate? Supergirl and Batman, they’re both DC regulars. So it must be an off-sides penalty? One of them should be lining up Tuesdays at 9:00 to go head-to-head with Marvel’s Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D., right?

Actually, no. Supergirl is CBS, Gotham is Fox. Neither networks cares about comic book rivalries. Their playing field is primetime. The CW airs a pair of Justice League characters too, Flash and Arrow, plus soon Atom, Hawkgirl and a few other second-stringers in their third DC-licensed show, Legends of Tomorrow. If CBS preferred any of those time slots, they’d land Supergirl there instead. Worse, Warner Brothers has a Flash film scheduled for a 2018 release—but it will be staring Ezra Miller, not CW actor Grant Gustin. If Green Arrow makes into 2019’s Justice League Part Two, Stephen Amell can expect to be benched too.

These aren’t just facelifts. The TV and film versions of DC superheroes are different people living in different worlds. Christopher Nolan had barely completed his Batman trilogy in 2012 when Warner Brothers started their Ben Affleck reboot. Supergirl earned her pilot because of her cousin’s box office success in 2013’s Man of Steel. But that’s not the same Superman. Look at Jimmy Olsen. The difference is literally black and white. He’s played by Mehcad Brooks on TV, and Rebecca Buller in the film (okay, they changed the female Jimmy to Lana Lang, but still).

Compare that no-rules rulebook to Marvel’s team-player strategy. In addition to the Avengers, the Marvel Cinematic Universe includes five solo franchises (Ant-Man, Thor, Captain America, Iron Man, Hulk), four Netflix shows (Daredevil, Jessica Jones, Iron Fist, Luke Cage), and two ABC shows (Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D., Agent Carter). And they’re all jigsaws pieces in a single, unified puzzle.

When the Netflix Matt Murdock talks about uptown superheroes, he doesn’t just mean Thor, Iron Man and Captain America; he means the Chris Hemsworth, Robert Downey Jr., and Chris Evans incarnations of Thor, Iron Man and Captain America. Peggy Carter began in the first Captain American film in 2011, before spun-off in her own TV show last year, and she appeared in the first scene of this summer’s Ant-Man, and she’ll appear again for her own funeral in Captain America 3 next spring.

Imagine the galaxy-sized migraines involved in keeping all those planets spinning in the same solar system. No wonder DC and Warner Brothers happily hand-over creative control for each of their independent universes. When asked about Supergirl, Nina Tassler, President of CBS Entertainment, said “we’ve been given license and latitude to make some changes.” In other words, forget continuity, our Supergirl flies solo. That might sound less impressive—hell, it is less impressive—but orbiting inside the Marvel Cinematic Universe carries its own penalties.

Witness director Edgar Wright. The hilariously idiosyncratic British film-maker approached Marvel about Ant-Man back in 2004. The then-fledgling studio was delighted. But when production finally rolled around a decade later, the Marvel blockbuster mill wasn’t so keen on Wright’s personal take on a potential franchise. Avengers director Joss Whedon adored the script, but Marvel scrapped it, handed the rewrite pen to Paul Rudd, and subbed out Wright for the lesser known but far more malleable Peyton Reed. Granted, Reed’s miniature battle scene shot on a Thomas the Tank Engine train track was genius, but the rest of the film was by-the-Marvel-numbers.

There’s at least one potential reason for that all-controlling gravity. At the center of the Marvel Cinematic Universe spins a supermassive black hole named Disney. It also owns ABC, home of Carter and S.H.I.E.L.D. It was also the TV home for Superman in the 50s, Batman in the 60s, and—for a season at least—Wonder Woman in the 70s. But the Mickey Mouse subsidiary isn’t interested in promoting Warner Brothers property anymore.

The megalomaniacal one-puzzle policy has even taken root in Marvel Entertainment’s root company, Marvel Comics. Its continuity used to include thousands of free-wheeling universes. On Earth-1610, Spider-Man is black and Hispanic; on Earth-2149, superheroes are zombies; on Earth-8311, Peter Parker is a pig named Peter Porker. There was even an Earth-616, where we all read Marvel Comics, and Earth-199999, home of the Evans, Downey Jr., and Hemsworth Avengers, who apparently are completely unaware that Marvel Studios is watching and recording them.

That all changed last summer. With its mini-series Secret Wars, Marvel Comics destroyed its fifty-year-old universe, and rebooted its most beloved characters into a single, one-size-fits-all reality (All-New All-Different Marvel!), in which its writers and artists must toil in perfect, lock-step synchronization.

Meanwhile, DC is following Supergirl in the opposite direction. After their own recent, reality-transforming maxi-series Convergence, every character, storyline, and alternate world that’s ever appeared in any DC comic book is officially back on the playing field. Apparently the writers were envious of their TV and screenplay counterparts and wanted the same unfettered free-for-all. And now they got it.

So when you tune in to Supergirl Monday nights, enjoy the metaphysical implications of your viewing choice. That’s a whole new world blinking on your screen.

Chris Gavaler's Blog

- Chris Gavaler's profile

- 3 followers