Chris Gavaler's Blog, page 26

January 11, 2021

Two Comic Strips from January 6, 2021

January 4, 2021

What My Top Posts of the Year May or May Not Say about 2020, the Internet, and Me

I started this blog in the fall of 2011. It received a little over 18,000 views its first full year, a little over 32,000 last year, and 235,681 total. It is a tiny tiny corner of the Internet. I named it after a novel I drafted in 2011 and was hoping to promote. The novel remains unpublished, though I now have an agent submitting a graphic novel to London publishers, so my fingers remain permanently crossed. Since starting the blog, I’ve also published five academic books about (mostly) comics, including one out later this month (Creating Comics). A sixth is under contract for 2022. The first was a revised version of the blog’s first four years. Some of those posts still get the most views—not just in total, but each year. Here’s my 2020 top ten:

Analyzing Comics 101: Layout

Science Fiction Makes You Stupid

Is Harry Potter a Superhero?

Ferris Bueller’s Missing Sex Scene

Hundred-Year-Old Racist Superman from Mars

A Brief History of the Pornographic Superhero

The Best (and Worst) Superhero Sex of All Time

Why I Shouldn’t Be Fired for Teaching Comics

Analyzing Comics 101: Rhetorical Framing

Only one of those was newly posted in 2020, which means the rest attract attention from somewhere other than the weekly links I post on my Facebook page, Twitter account, and my university’s campus notices. Seven of the ten are also high on my blog’s all-time top list:

Science Fiction Makes You Stupid

Is Harry Potter a Superhero?

The Best (and Worst) Superhero Sex of All Time

Hundred-Year-Old Racist Superman from Mars

Analyzing Comics 101: Layout

Jean Valjean, Wolverine, and What Boys (Are) Like

Carrie White Vs. Jean Gray

Why I Shouldn’t Be Fired for Teaching Comics

Are Batman and Robin Gay?

Layout Wars! Kirby vs. Steranko!

Ferris Bueller’s Missing Sex Scene

Two have the words “sex” or “pornographic” in the title, which I’m guessing are very popular search engine terms. Type in “superhero” next to either and apparently my blog appears somewhere in the results list. The 2018 Ferris Bueller post has “sex” in the title too, so another mystery solved. I’m really not sure why Harry Potter is still getting so many hits in 2020 (I wrote it back in 2013), or, more weirdly, John Carter of Mars (though it did annoy some Edgar Rice Burroughs fans in 2012 when I published the post-colonial critique of the novel and film). My unfortunately click-bait titled “Science Fiction Makes You Stupid” got unexpected international attention in 2017, including from annoyed SF fans—though the actual post and the cognitive science research study it describes (as well as the follow-up study) should make a SF fan (like me) happy. At least the two “Analyzing Comics” make sense since analyzing comics is mostly what I do here. “Why I Shouldn’t Get Fired for Teaching Comics” is from 2019, so the youngest post on the all-time top ten and the second youngest for 2020. It was my response to an essay written and distributed by an alum suggesting that my courses and I be eliminated for dumbing down the W&L curriculum.

The outlier is “Why I Asked my University to Remove ‘Lee’ from its Name and my Town to Remove ‘Stonewall Jackson’ from the name of its Historic Cemetery” because it’s the only top-ten post from 2020 that was actually published in 2020. Since I wrote it in July, my town has renamed the cemetery. A statue of Stonewall Jackson was also removed from the Virginia Military Institute, the college literally next door to mine. My school’s board of trustees has not yet made a decision regarding our name.

I wrote “Why I Asked” for Rockbridge Civil Discourse Society, a Facebook group that I co-founded and was still moderating until fall. The group was designed to foster conversation between folks coming from opposite sides of the political divide. The issues of statue removals and name changes was getting a great deal of attention on the page, and the post was my attempt to explain my positions in a way that I hoped a conservative could at least understand (though almost certainly not agree with).

I had written “Why I Don’t Like Trump” in 2019 for the same reason: a conservative member of RCDS sincerely asked my why I didn’t like Trump, and I gave him the most thoughtful, non-inflammatory answer I could. I republished it in October—which is why “Why I (Still) Don’t Like Trump” hit sixteen on my top posts of 2020. Number fourteen was “How Rightwing Pundits Destroyed America and my Facebook Page,” published the same month. After moderating RCDS for three years, I got a little tired out. My farewell, “Things I Learned from Civil Discourse,” only hit thirty-one. It’s a list of best practices for trying to engage in political conversation with someone who doesn’t vote like you. Very few folks on the page follow them.

I also got a bit obsessed with poll watching in 2020, publishing a four-part series “Predicting the Next President,” which mapped the polling shifts and Electoral College predictions. It ended with “After Math: So How Wrong Were the Polls?” Short answer: pretty wrong.

I published twenty-four reviews of graphic novels. Since I started writing reviews at PopMatters.com three years ago, those reviews have dominated my personal blog too.

Another eighteen posts focused on other kinds of comics analysis, my own comics, my creative process, comics I helped publish through Shenandoah, plus one comic my daughter made during the lockdown with one of her former students whom she was nannying after their pre-school was forced to close because of the pandemic.

There were also six posts about zombies.

Weird fucking year. Glad it’s over.

December 28, 2020

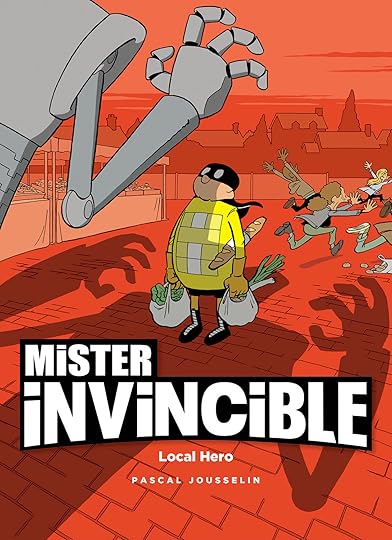

Mister Invincible vs. My Annoyingly Pretentious Comics Theory Terminology

Two annoying terms I can’t seem to stop using when discussing comics: ‘discourse’ and ‘diegesis.’ They’re sort of the same as ‘form’ and ‘content,’ or ‘form’ and ‘story.’ Except sometimes comics seems to crash form and story together, obscuring the distinction. Other art forms (prose fiction, films, live theater) have discourses and diegeses too, but the effects in comics might be unique.

One of the presents I unwrapped Christmas morning was Pascal Jousselin’s Mister Invincible: Local Hero, a collection of French comics translated and published in English in 2017, but new to my radar this year (which is why I put it on my Santa list–though all actual credit goes to my spouse). It’s one of the most playfully brilliant interrogations of the comics form I’ve seen, literally illustrating the discourse/diegesis divide and its peculiar comics conundrums.

First, with massive apologies to Jousselin, here are six panels from one of his collection’s one-page comic strips, rearranged in my own cascading column:

Though obscured by my arrangement, you probably see the key connection between panels 2 and 5. Ignoring the also vast issues of framing and perspective, my arrangement attempts to isolate each panel and emphasize the linear relationships of their content. This is close to the story as experienced by the woman worried about her cat.

Here’s another rearrangement, one that could more easily appear on an actual comics page, with paired panels in three rows:

The trick is still between panels 2 and 5, which is a little easier to see now because this arrangement places the interior content of each panel in roughly the same position relative to each other: the six trees line-up in two columns, parallel to the middle gutter.

Of course the drawings are all of only one tree: the one in the story world. That’s where annoying terms become usefully non-annoying. Using their adjective forms: there’s one diegetic tree, but six discursive trees. I could still says there one story-world tree, but saying there’s six formal trees is less clear, plus the formal effects of the cascading arrangement and the three rows of paired panels are different.

But not as different as the two rows of three panels that Jousselin actually drew:

Only now is the key conceptual connection between panels 2 and 5 also a physical connection. The arrangement is the joke. Mister Invincible’s superpower is the comics form. He seemingly reaches out of the diegesis and into the discourse of the page.

Though that’s not quite accurate. Understood diegetically, he just has time-travel powers: he can reach his arms out of his current moment and into another moment, removing an object (the cat) from that other moment and bringing it into the current moment. That would be the woman’s understanding of what happened. Mister Invincible, however, knows that his diegetic time-travel powers are rooted in the panel arrangement of the page. That’s why my first two arrangements ruin the joke.

But it’s more than panel arrangement. If, for example, panel 5 were drawn from a more distant perspective, so that the discursive space between the top of the tree were longer than the discursive length of Mister Invincible’s arms as drawn in the other panels, then he could not reach down and retrieve the cat. So it’s not just the layout of the panels but also the interior arrangements of their drawn content, including framing and perspective effects.

That means Mister Invincible sees everything that the viewers sees. He is aware of the page. That’s a delight of metafiction, but it reveals something else about the comics form: the layout of panels is not a formal quality; it’s a diegetic quality. Layout is part of Mister Invincible’s story world (and also his superhero-defining chest emblem).

Characters in other artforms can have metafictional qualities too: a character played by an actor turns and addresses the audience, either directly from a stage or seemingly through a camera and screen. A character in a prose novel might metaphorically break that fourth wall too, revealing that she knows she’s an author’s construction living in a constructed story world. But if so, she’s probably not aware of the ink that comprises the words that comprise her and that world. She’s not aware when the typeset words reach the right margin requiring a reader to shift to the left column to continuing reading. She’s not aware of paragraphs or page breaks either. She’s aware that her diegesis is a diegesis, but she’s unaware of the discourse (the physical book) that creates the diegesis (in collaboration with a reader reading it).

That doesn’t describe Mister Invincible. He doesn’t seem to be aware of his creator, Jousselin, or of viewers viewing his actions. I don’t know if he knows he’s in a diegesis. But I do know that an aspect of his diegesis is the discursive arrangement of image content on each page. That creates an interesting puzzle: while content and form can be related in all kinds of interesting ways, form can’t BE content. Instead of breaking the discourse/diegesis divide, Mister Invincible reveals that no such divide exists when it comes to what is typically called “form” in comics.

That means layout is not part of the comics form. It’s a kind of diegesis. Usually that diegesis is distinct from the character-populated world of the story, but it’s still a kind of diegesis, meaning a set of representations. The frames around the panels are not frames: they’re drawings of frames. The spaces between panels are not empty; they are drawings of emptiness. The only formal (meaning physical) parameters of a comics page are the physical edges of the paper that the ink is printed on. Mister Invincible is powerless against them because they exist only in the viewer’s world. The arrangement of panels is drawn to look like it exists in the viewer’s world too (like a gallery wall of framed images would actually exist in a viewer’s world), but that effect is no more real than the tree or the cat or the woman or Mister Invincible.

What do you call layout then? I’ve been puzzling through this while drafting my next book, The Comics Form: The Art of Sequenced Images (I just signed a new contract with Bloomsbury this month). While layout is a ‘secondary diegesis,’ the phrase misses its most salient features and could mean something entirely different (a story world within the story world). I first tried ‘pseudo-discourse,’ which made one of my collaborators (co-author of Creating Comics) laugh out loud–and not in a good way. So I’m currently going with the slightly less pretentious-sounding ‘pseudo-form.’

Comics panels are often drawn as though they are card-like images placed on the surface of a page. Sometimes they appear to overlap, either partially at corners, or entirely with insets, including panels that are insets on a full-page image. The word “on” is key. That’s a diegetic illusion. It’s all just ink marks beside inks marks (or pixels beside pixels). Only an illusion of diegetic content can appear to be “on” something else, as though that something else would be visible if the “top” content were somehow removed. It’s an illusion of depth–or let’s say ‘pseudo-depth’ since it’s distinct from the effects of depth created within the framed images through traditional naturalistic drawing techniques (three-dimensional perspective, light-sourced shading, etc.)

And that’s Mister Invincible’s improbable superpower: a panoptic awareness of and ability to navigate non-linearly but contiguously through the secondarily diegetic pseudo-form of each comics page.

He’s also a character in a really cute children’s comic I got for Christmas. Thanks, Santa!

December 21, 2020

Black Superheroes Matter

That isn’t the name of my first-year writing seminar, but I considered it when revising my syllabus for the upcoming winter term.

I’ve taught my “Superheroes” section of WRIT 100 for years now, making incremental syllabus changes but never an outright reboot. I invariably begin with the first year of Superman, beginning with Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster’s Action Comics No. 1 (1938). I originally followed that with the first year of Batman in Bill Finger and Bob Kane’s Detective Comics (1939), establishing the cornerstones of the comics genre. After that I’ve swapped around a range of other media.

For films, I’ve always liked M. Night’s Shyamalan’s 2000 Unbreakable (though absolutely not his recent sequel Glass). It paired well with Peter Berg’s 2008 Hancock, especially the contrasting roles of Will Smith’s hero and Samuel L. Jackson’s villain. But the homophobia (not just Hancock’s casual insults, but the use of sitcom-style music playing after Hancock apparently shoves a man’s head into another man’s asshole) was just too much. At my daughter’s much appreciated insistence, I replaced it with Patty Jenkin’s 2017 Wonder Woman. (And if you think the gender of the director is insignificant, compare how Justice League director Zach Snyder centers his camera through Gal Godot’s thighs.)

For prose works, I started with Austin Grossman’s 2007 Soon I Will Be Invincible (still one of my favorite novels), but soon swapped it for editors Owen King and John McNally’s 2008 collection Who Will Save Us Now? Brand-New Superheroes and Their Amazing (Short) Stories (assigning literally all of the female authors, to balance the all-male authors of the early comics).

For poetry, Gary Jackson’s 2009 collection Missing You, Metropolis (which won the Cave Canem Poetry Prize) is unbeatable. (And as a happy result of teaching him, I also just completed a chapter on Jackson for the essay collection Mixed-Race Superheroes forthcoming next year from Rutgers University Press.)

At the end of each semester, I would return to comics for a contemporary look at superheroes. G. Willow Wilson and Adrian Alphona’s 2014 Ms. Marvel: No Normal was always on the top of my and later my students’ favorite lists. Greg Rucka and J. H. Williams’ 2010 Batwoman: Elegy got more mixed reviews the more times I taught it, happily because the presentation of the first lesbian hero to star in her own series grew more dated as students questioned why the writer was making such a big deal about the character’s sexuality.

I like to assign a range of secondary readings too. Editors Robin S. Rosenberg and Peter Coogan’s 2013 essay collection What is a Superhero? (from Oxford) and Matthew J. Smith and Randy Duncan’s 2011 Critical Approaches to Comics (from Routledge) are useful. The gender balance in comics scholarship is not great, so I tend to highlight female scholars. Claire Pitkethly’s “Straddling a Boundary” is one of my all-time favorite essays, and Jennifer K. Stuller’s “What is a Female Superhero?” and “Feminism: Second-wave Feminism in the Pages of Lois Lane” have been equally helpful. Kara Kvaran’s “Super Daddy Issues: Parental Figures, Masculinity, and Superhero Films” was key for Unbreakable and Hancock. And how could I not include the introductory essay “Representation Matters” from Carolyn Cocca’s 2016 Eisner Award-winning Superwomen: Gender, Power, and Representation?

This year I’m adding an excerpt from Rachelle Cruz’s textbook Experiencing Comics (even better, Cruz is also joining the editorial board of my university’s literary journal Shenandoah as guest comics editor this winter). I’m also adding Kenneth Ghee’s “Will the Real Black Superheroes Please Stand up?! A Critical and Analysis of the Mythological Cultural Significance of Black Superheroes” from Black Comics: Politics of Race and Representation. That’s from Bloomsbury, an increasingly impressive home for comics studies, since they also publishes Carolyn Cocca and Neil Cohn. (Happily, my and Leigh Ann Beavers’ textbook Creating Comics will be out from Bloomsbury next month, and I just signed a contract with them for my next book, The Comics Form, for 2022.)

In the past, I’ve tended to change one primary text at a time. For the section that starts in January, I’m adding works by three new authors: Nnedi Okorafor’s 2019 comic Shuri: The Search for Black Panther and her 2015 novella Binti (which won both the Hugo and Nebula awards for best novella);

Eve L. Ewing’s 2019 comic Ironheart: Those With Courage and her 2017 poetry collection Electric Arches (Ewing, who has a Ph.D. from Harvard, also wrote the 2018 Ghosts in the Schoolyard: Racism and School Closings on Chicago’s South Side, which I considered excerpting, but a syllabus only has so much room);

and Ta-Nehisi Coates 2017 comic Black Panther and the Crew: We Are the Streets. I am also adding an excerpt of G. Willow Wilson’s 2010 memoir The Butterfly Mosque.

Okorafor’s Binti is not a superhero text, but I’m looking forward to reading the science fiction story about a young Black woman from a futuristic Earth traveling across the galaxy to attend a university against Okorafor’s portrayal of Shuri, the sister of the original Black Panther. Ewing’s Electric Arches is not superhero text either, but it should also read well against her portrayal of Riri Williams, the young Black woman who assumed the renamed role of Iron Man in 2015. It will also be nice to give Gary Jackson some poetry company. Wilson’s The Butterfly Mosque describes her conversion to Islam, which should add an interesting angle of analysis to her portrayal of Ms. Marvel, AKA Kamala Kahn. (Unlike previous years, my students should enter class with plenty of exposure to the correct pronunciation of her first name.)

Ta-Nehisi Coates is best known for Between the World and Me, which won the 2015 National Book Award for Nonfiction. Marvel Comics responded by offering Coates a new Black Panther series, which premiered in 2016. Black Panther and the Crew is one of his short-lived but therefore stand-alone spin-offs, featuring a range of Marvel’s Black superhero characters. I suspect it will especially resonate in our current Black Lives Matter context. (Unfortunately, my college announced after I placed my book orders that our winter calendar will include three “class free” days TBA, requiring some scheduled syllabus content to be cancelled. Since Coates is flying solo, his comic is a potential sacrifice–though I really hope not.)

I’m also adding a collection of William Moulton Marston and Harry Peter’s early 1940s Wonder Woman comics to pair with Superman (though the creators are all still male). In total I’m keeping three primary texts (Superman, Ms. Marvel, Gary Jackson) and adding six. That’s the most I’ve shaken up my WRIT 100 since I switched the course topic to superheroes five years ago (it used to be called “I see Dead People” and featured a lot of Henry James and zombies). An alumnus wrote and distributed his opinion essay to the W&L community two years ago, advocating that, based solely on my title “Superheroes,” the course and I should be “eliminated” for “dumbing down” the curriculum at W&L. Since my revised syllabus adds a National Book Award winner, a Nebula and Hugo Awards winner, and a Harvard Ph.D, in addition to a pre-existing Cave Canem Poetry Prize winner, I hope I am safe from that criticism this year.

December 14, 2020

New Comics from Shenandoah!

When Shenandoah relaunched under the editorial vision of Beth Staples in fall 2018, I was lucky to be on board as the journal’s first comics editor. That rebirth issue featured comics artists Mita Mahato and Tillie Walden, and the subsequent issues have included seven more comics by creators: Miriam Libicki, Rainie Oet and Alice Blank, Marguerite Dabaie, Holly Burdorff, Fabio Lastrucci, Gregg Williard, and Apol Sta. Maria, Marlon Hacla, and Kristine Ong Muslim.

Issue Volume 70, Number 1 just went live this week, and I think Beth was being a little too kind to me, because it features almost twice as many comics titles as previous issues:

Also, unlike those first few issues that featured only works from artists I had personally solicited, these artists all found their way to our Submittable portal unprompted–which I take as evidence of Shenandoah‘s increasing reputation not just as a prestigious literary journal (it’s been that for decades), but now also as major home for literary comics. The term “literary comics” is a new one, but I’m glad to see Shenandoah helping to define it. I had organized an AWP panel on the topic, “Comics Editors & Literary Journals,” but the pandemic had other plans. Happily though, Shenandoah is expanding its comics reach with guest comics editor Rachelle Cruz curating the Spring issue (if you don’t know her textbook Experiencing Comics, you should check it out).

Also, unlike those first few issues that featured only works from artists I had personally solicited, these artists all found their way to our Submittable portal unprompted–which I take as evidence of Shenandoah‘s increasing reputation not just as a prestigious literary journal (it’s been that for decades), but now also as major home for literary comics. The term “literary comics” is a new one, but I’m glad to see Shenandoah helping to define it. I had organized an AWP panel on the topic, “Comics Editors & Literary Journals,” but the pandemic had other plans. Happily though, Shenandoah is expanding its comics reach with guest comics editor Rachelle Cruz curating the Spring issue (if you don’t know her textbook Experiencing Comics, you should check it out).

First though, let me give some teasers for the winter issue’s cast of artists, starting with Angus Woodward’s “The Art Table.” I’m especially impressed by how Angus pushes against comics conventions, while still providing the narrative pleasures of the form.

Amy Collier’s “Birds You’re Watching and the Complex Histories You’ve Made up About Their Personal Lives Due to Boredom” is an especially (yet subtly) timely sequence that indirectly (and comically) evokes the psychological effects of the pandemic lockdown.

Grey Wolfe LaJoie’s Unfished Unfinished in an artful comics ars poetica, shifting from black and white line art to full watercolor as it literally turns the form sideways.

Mark Laliberte’s two excerpts from “AM/FM/PM” turn the form on its head, experimenting with the wonderful weirdness of juxtaposition (and, because of the online formatting, even a hint of match-cut animation).

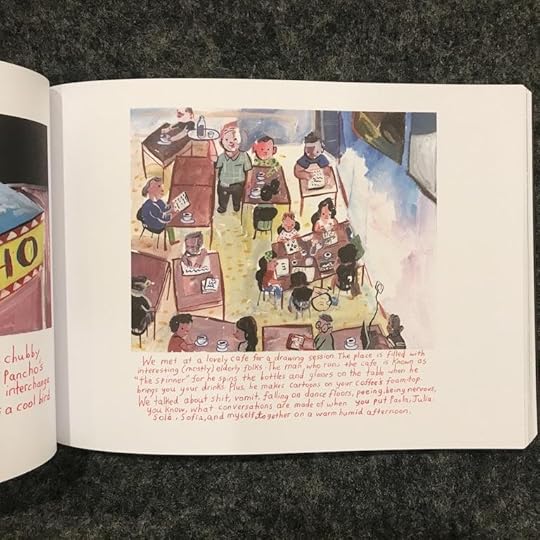

Jenny Lesser’s watercolors imbue her Anger Management with paradoxical pleasure that invigorates even the letters of the static words.

We also owe Jenny an additional and massive thank you for the original watercolor portraits she painted of readers (poets, fiction writers, memoirists) from the Zoom launch party last week:

They’re all in the new issue!

December 7, 2020

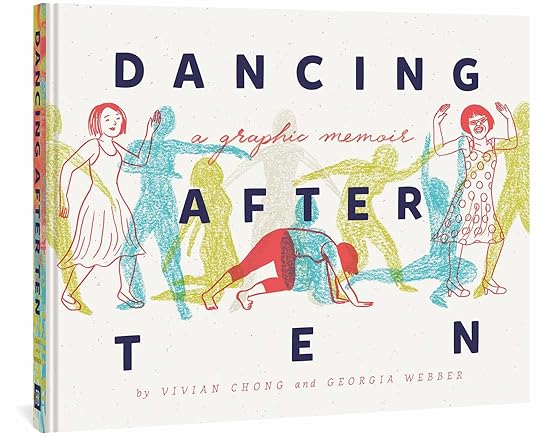

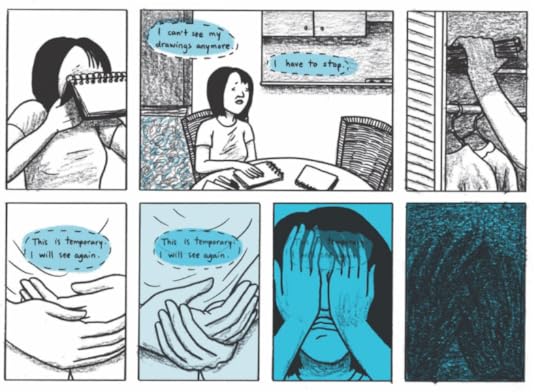

One Plus One Is Ten

I’m always intrigued when I see two author names listed on a graphic memoir. I know what that usually means for a graphic novel: the first name belong to the writer, the second to the artist. But both Vivian Chong and Georgia Webber, the co-authors of the graphic memoir Dancing After TEN, are artists. For monthly comic books, that usually means the first name is the penciler’s, the second the inker’s. But again, not this time. Chong’s and Webber’s individual art sometimes occupies separate pages, sometimes separate panels on the same pages, and sometimes separate elements within shared panels. The combination is an interwoven visual conversation, based in part on actual face-to-face conversations they had at Chong’s kitchen table (as drawn by Webber). The memoir also merges—and in some cases literally tapes together—artwork spanning more than a dozen years.

November 30, 2020

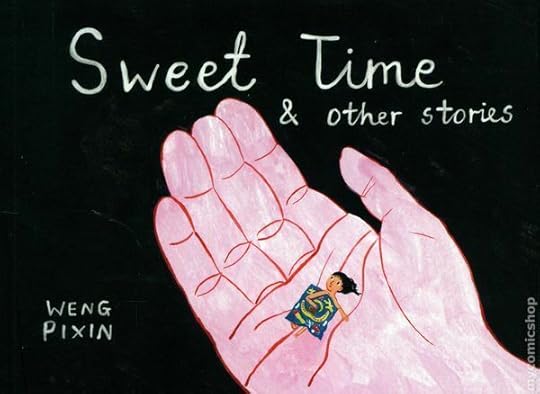

Sweet Time Hits the Sweet Spot

It’s a little too early to announce my favorite comic of 2020, so I’ll just say Weng Pixin’s Sweet Time & Other Stories is one-hell-of-a contender.

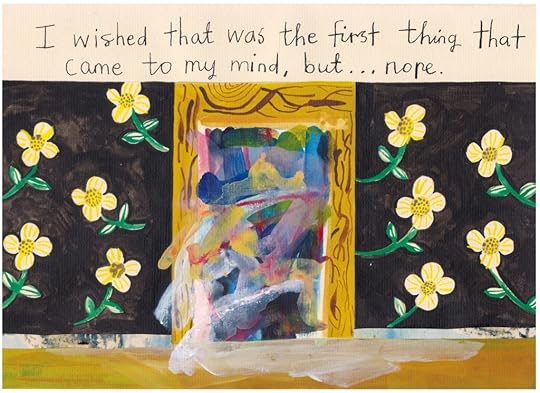

Though the art of Sweet Time is by definition comics art, it stands impressively far apart from most of the conventions and genre expectations of the medium’s mainstream publishing history. In terms of form, Pixin is a comics artist—because she is composing sequences of juxtaposed images—but the visual impact of her artwork escapes the norms of most other graphic literature.

This is true despite her working with traditional panels and gutters. Though how often does a comics artist carefully construct and layer strips of paper to form gutters that are as visually engaging as the content of the images they frame? How often does a comics artist focus attention on the qualities of her brushwork as her impressionist dabs widen into the thick swaths of an expressionist? How often is a comics viewer able to appreciate the texture of the paper absorbing the watercolors? It might be more accurate to simply call Pixin an artist, one who happens to be working in the comics form.

Categorizing Sweet Time is pleasantly difficult too. What do you term something that combines fiction and nonfiction—though maybe doesn’t? Graphic memoirs are sometimes called graphic novels despite prose novels indicating fictional content. Whatever the nature of Pixin’s content, the second half of her title, & Other Stories, implies a collection, so even the more recent and inclusive term graphic narrative falls short.

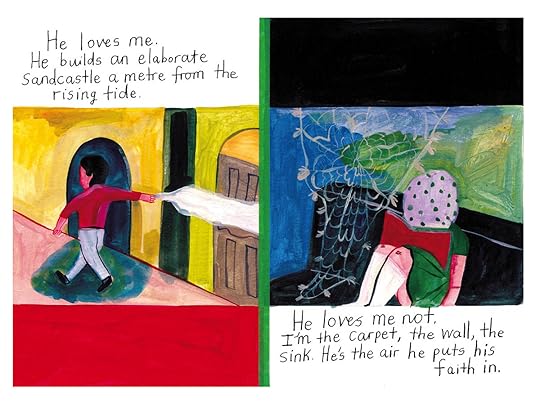

The fifteen subtitled subsections range from four to thirty pages, though most hover in the teens. Four are sequences of visual diaries organized by place: New York, Argentina, Lampung, Home. Other sections strike an autobiographical tone: a childhood crush, conversations with boyfriends, meeting a stranger in a bar, lots of mildly disturbing sex. The scene between an anthropomorphic frog and an anthropomorphic cat is obviously fantastical, though the flavor of its dream logic seems grounded in experience. But the young couple in the row boat who float past a burning funeral pyre, is that a dream too?

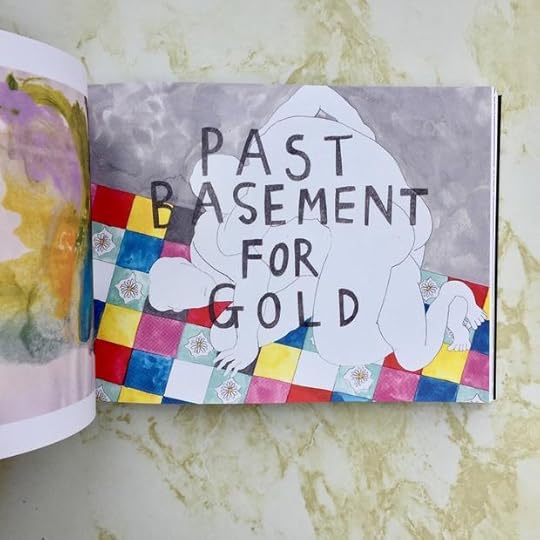

The one wordless section, “Past Basement for Gold,” transcends the fiction/nonfiction dichotomy in the way any painting or sequence of paintings avoids such literary analysis. No one asks if an O’Keefe or a Rothko is autobiographical. While most of Pixin’s images are representational, sometimes the degree of abstraction is so high, they begin to dissolve into pure form. That’s a real rarity in traditional comics, and one of the many strengths of Pixin’s.

Technically there’s no difference between the abstractions of fine arts painting (Picasso’s cubist distortions, for example) and the abstractions of comics cartooning. Both simplify and exaggerate. Pixin brings them even further together by employing an aggressively abstract style to repeating figures that, even though they appear in comic strips, resist the clichés of cartoons. Her blocky shapes and wonky perspectives are so rudimentary they can evoke children’s drawings at times, and yet their consistency and precision are equally striking. I especially admire the full-page paintings in the longest sequence, “The Boat,” for capturing nuances of emotion through the figures’ facial expressions, while also emphasizing the formal effects of the brushstrokes that create them. Better still, the textures of the strokes on the page, while not directly representing anything in the story-world, evoke emotional qualities in themselves, doubling the overall impact of the images. That’s arguably what people mean when they distinguish something as “art.” Form and substance combine to achieve something that transcends each individually.

Pixin makes the most of the comics form, while literally turning it sideways. Though Sweet Time is a standard size and shape for book publishing, its rectangular pages are wider than they are tall, and so the spine attaches at what would be the top edge of most other books. The internal panels run left-to-right, most often two to a page, but some of the collection’s best sequences compress a dozen panels across three rows, each image only slightly larger than a postage stamp. The result should be cramped, but Pixin’s improbable combination of precision and looseness gives each page a feel of natural balance, as though no other formal approach would suffice. She also arranges three of the sequences as columns instead of rows, requiring the viewer to rotate the book and flip the pages like a calendar, before rotating it back again for the next sequence.

Pixin’s narrative style is equally eclectic. Each diary entry is a stand-alone semi-distorted snapshot-slice-of-life with no overarching plot or thematic focus unifying the progression, and yet the artistic effect is still unified. Her presumably fictional “stories” do share subject matter, as their similarly drawn protagonists navigate some thorny moment of a relationship, whether long-term or newly formed.

The archetypal figures and nudity made me want to read “Roses” as a riff on Adam and Eve, a continuous visual motif undercut by the couple’s eventual break-up and the woman’s wandering out into the wilderness alone. “Pairs” concludes both more positively (no break-up) and more darkly (the gray watercolors of the woman’s dying father interweave with the couple’s love-making). The title story concludes the collection with a love-making scene that literally dissolves into pure abstraction, before rebooting the next morning for a cringingly precise second bout followed by a one-panel scene of estranged coffee.

Others are harder to summarize, which is appropriate. No summary of a painting or a poem is ever adequate. That’s the point. Whatever you call Sweet Time, it’s a welcome expansion to the practical definition of comics as an art form.

November 23, 2020

Designing a Comics Character

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

[image error]

November 16, 2020

After Math: So How Wrong Were the Polls?

A week before the election, I gathered and posted conglomerate polling numbers from FiveThirtyEight (updated October 26) for the ten battleground states. Here they are again, now with the actual outcomes:

Michigan

Polls: Biden up 8.

Results: Biden by 3.

Difference: 5 for Trump

Wisconsin

Polls: Biden up 6.7.

Results: Biden by .6.

Difference: 6.1 for Trump

Pennsylvania

Polls: Biden up 5.6.

Results: Biden by 1.

Difference: 4.6 for Trump.

Arizona

Polls: Biden up 3.0.

Results: Biden by .3.

Difference: 2.7 for Trump.

North Carolina

Polls: Biden up 2.5.

Results: Trump by 1.3.

Difference: 3.8 for Trump.

Florida

Polls: Biden up 2.4.

Results: Trump by 3.

Difference: 5.4 for Trump.

Iowa

Polls: Biden up 1.2.

Results: Trump by 8.2.

Difference: 9.4 for Trump.

Georgia

Polls: Biden up .4.

Results: Biden by .3.

Difference: .1 for Trump.

Texas

Polls: Biden up .1.

Results: Trump by 5.7.

Difference: 5.8 for Trump.

Ohio

Polls: Trump up 1.5.

Results: Trump by 8.

Difference: 9.5 for Trump.

So the one good moment for the state polls:

threading the Georgia needle by .1.

The worst moments:

missing Iowa and Ohio by almost double digits.

Even worse:

missing seven of the ten states by more than four points.

Worst overall:

under polling Trump every time.

Okay, but what about the national polls?

On the day before the election, Biden was up by 8.4 at FiveThirtyEight, and by 7.2 at RealClearPolitics. The national vote results are still dribbling in, but Biden has at least 3.7, and FiveThirtyEight projects an eventual 4.3. So the least possible mistake is 2.5 for Trump, falling barely within a 3-point margin of error. At worst, the mistake is 4.7 for Trump.

That’s a lot worse than in 2016, when the RealClearPolitics final average put Clinton up by 3.2, and then she won the popular vote the next day by 2.1. That difference of 1.1 is pretty good. The mistakes in 2016 were only in some states polls, and, like with the popular vote, those mistakes only grew in 2020.

Pollsters have at least one line of defense: their margins of error were often 5 points. I wrote here two weeks before the election:

“Placing states with Biden or Trump leads under 5% as toss-ups, on Tuesday October 20, two weeks before Election Day, the state polls put Biden at 259 electoral votes.”

Only Michigan and Wisconsin were outside a 5-point margin of error. So according to the October 20 polls, the Electoral College was a toss-up–though with a massive Biden advantage. But a week later I wrote:

“As of today, Monday October 26, eight days before the Election, the polls would put Biden at 279 by including Pennsylvania. All of the other battleground states remain in the toss-up column’s margin of error.”

And that’s what happened. Biden won Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania, with contested leads in Arizona and Georgia.

Of course that doesn’t explain the mistakes always falling in the same direction. If these were just garden-variety sampling errors, at least some should have favored Biden. None did.

It’s not clear why the polls were wrong. Michael Moore offered one rationale a week before the election:

“Don’t believe these polls … the Trump vote is always being undercounted. Pollsters, when they actually call a real Trump voter, the Trump voter’s very suspicious of the ‘Deep State’ calling them and asking them who they’re voting for. It’s all fake news to them, remember. It’s not an accurate count. I think the safe thing to do, this is not scientific … whatever they’re saying the Biden lead is, cut it in half, right now, in your head. Cut it in half, and now you’re within the four-point margin of error.”

Is Moore right? Do Trump voters lie to deep-state pollsters?

Maybe. His “not scientific” cut-it-in-half methodology proved about right, but there’s no test for evaluating the accuracy for his explanation. And yet Nate Cohn (the Nate who replaced Nate Silver at the New York Times) now echoes Moore:

“It’s hard not to wonder whether the president’s supporters became less likely to respond to surveys as their skepticism of institutions mounted, leaving the polls in a worse spot than they were four years ago.”

Cohn also wonders about a mirror effect from progressives:

“the resistance became likelier to respond to political surveys, controlling for their demographic characteristics… Like most of the other theories presented here, there’s no hard evidence for it — but it does fit with some well-established facts about propensity to respond to surveys.”

The pandemic may have influenced that even further with a “post-Covid jump in response rates among Dems” because they “just started taking surveys, because they were locked at home and didn’t have anything else to do.” Cohn also wonders whether the high turn-out helped Trump, with the polls’ focus on “likely voters” (where Biden was up much higher) missing the actual votes of the less likely but registered voters who did show up on election day after all.

So bottom line: the 2020 state polls were as bad as the 2016 state polls, the 2020 national polls were worse than the 2016 national polls, and we don’t know why.

If you ignore the margins of victory in each battleground state, the 2020 forecasts did much better. They all predicted Biden, though with a wide range of differing Electoral College totals.

First, to their credit, all of the forecasters correctly placed Wisconsin and Michigan in the Biden column, giving him a minimum of 259.

Politico said Biden would win with 279 electoral votes by taking Pennsylvania, but they left Arizona in the toss-up category and incorrectly predicted Georgia for Trump. So they missed two states, one for Biden, one for Trump, and dodged calling five states, including three (Florida, Ohio, Iowa) that Trump won easily.

Crystal Ball, Cook Political Report, CNN, and NPR all said Biden would win with 290 votes, correctly predicting that he would take not only Pennsylvania but also Arizona, leaving five states in the toss-ups.

U.S. News predicted Biden with 290 too, but they also correctly placed Iowa and incorrectly placed Georgia in the Trump column.

Things go down hill from there:

Inside Elections gave Biden 319 by adding Florida to his column.

The Economist gave him 323 by including Florida and North Carolina but not the toss-up Arizona.

Decision Desk, PredictIt Market Probabilities, and FiveThirtyEight all gave Biden 334, giving him Florida and North Carolina.

JHK Forecasts and Princeton Election Consortium predicted 335, the extra one point coming from Maine’s second district.

Since Biden’s actual count is now 306 (the same as Trump’s self-described 2016 “historic landslide”), just over half, seven out of the thirteen forecasters, overshot.

That’s mainly because they all incorrectly predicted Florida for Trump. Since Trump won Florida by a safe three points, Florida is both the polls’ and the forecasters’ biggest 2020 failure.

Five of the forecasts also gave North Carolina to Biden, but since Trump won it by only 1.3, North Carolina seems legitimately purple. Though not the incandescent purple of Georgia, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Arizona where Biden’s margin was under 1%, very similar to Trump’s 2016 margins.

So, like in 2016, the final map hides how close the Electoral College race was.

Of course if we elected our presidents by national popular vote, a Biden 4-point margin of victory isn’t close at all.

November 9, 2020

Two-Face Elections

I wrote this nonsense four years ago:

“Before the election, I had a vision of the U.S. coming together. I fantasized that Clinton would announce in her acceptance speech that she would fill half of her cabinet positions with Republicans and challenge Congress to send her only bills co-authored by Republicans and Democrats or face her veto. I was imagining a Democratic-controlled Senate too, but instead of shoving a leftwing Justice down the remaining throats of the GOP (as they so deeply deserved for refusing to vote on President Obama’s Supreme Court nominee last March), I wanted Clinton to renominate moderate Merrick Garland in a show of compromise and goodwill. I wanted this despite the fact that my personal political beliefs are over there with Bernie Sanders and the rest of those Socialist-hugging, LGBQT-loving, Wall-Street-regulating, Climate-Apocalypse-fighting do-gooders. I actually believed that being part of a democracy meant accepting and even celebrating that fact that I should only get what I want about half of the time. That even some of my cherished principles come second to the national need for our government to work from the center, to bridge extremes and find common ground. I was a Radical Moderate.

“Until November 9th.[image error]

“Law-abiding District Attorney Dent, AKA Two-Face, became a supervillain after a thug threw acid in his face. Which is also how Donald Trump cured me of Moderatism. Though technically I don’t think Dent ought to be labeled a supervillain, since half of his actions should end up doing good. When faced with a tough choice, Two-Face flips a two-headed coin. I know that sounds like a rigged decision-making system (something the majority-losing President-Elect no longer talks about), but Two-Face carved a giant “X” through one of George Washington’s faces. Which is a perfect metaphor for the U.S. right now.

“I’ve literally put myself inside that two-faced quarter, and I will stay there until Trump and all of his rock-throwing GOP punks are gone–via resignation, impeachment, or nuclear Armageddon, I really don’t care. If you would also like to make a Two-Faced version of yourself, I’ve included step-by-step instructions:

“Step 1. Watch country elect pussy-grabbing bigot for president.

“Step 2. Stop shaving.

“Step 3. Shave right half of face.

“Step 4. Take selfie.

“Step 5. Shit around with selfie in Word Paint while country plummets into moral abyss.

“Step 6. Vow vengeance in 2018.”

It’s four years later, and Biden came pretty close to the acceptance speech I fantasized for Clinton:

“It is time to put away the harsh rhetoric, lower the temperature, see each other again, listen to each other again, and to make progress, we have to stop treating our opponents as an enemy. They are not our enemies: They are Americans — they are Americans.

“Folks, I am a proud Democrat. But I will govern as an American president. I will work as hard for those who didn’t vote for me as those who did. Let this grim era of demonization in America begin to end here and now. Refusal of Democrats and Republicans to cooperate with one another is not some mysterious force beyond our control; it is a decision, a choice we make.

“If we decide not to cooperate, we can decide to cooperate. I believe this is part of the mandate given to us from the American people. They want us to cooperate in their interests. That is the choice I will make. I will call on Congress — Democrats and Republicans alike — to make that choice with me.”

Of all the things that are changing, this is the absolute least important. After Biden’s speech, I went on Facebook and changed my profile image from the Two-Face selfie to this arty nonsense:

[image error]

Four years ago, I also made this bumper sticker:

[image error]

Of all the things that I could have focused on after Trump won, I decided gerrymandering was Job One. In retrospect, that seems more than a little bizarre. But it wasn’t stupid: draw fair maps and Democrats win. And sometimes they win anyway. In 2017, the GOP’s gerrymandered supermajority dwindled to a single seat (determined by a literal coin toss), and the 2019 blue wave (see “Vow Vengeance” above) flipped the legislature to Democratic control. Having seen their future as the minority party, the GOP had already started the process of amending the Virginia constitution with a redistricting commission that would prevent the majority party from rigging the maps the way the GOP did for the last decade. The referendum passed last week.

The fight to end gerrymandering in Virginia is over.

Which brings me to the second least important change in the U.S.. Over the weekend I switched my Facebook book cover from the End Crooked Districts bumper sticker to this:

[image error]

Those are some of my actual book covers. The last one, Creating Comics, is due out in January, between Georgia’s two Senate-majority-determining run-off elections and Biden’s inauguration.

Which is to say: quit shitting around and get back to work.

I’m sure as hell no superhero (or supervillain), but this fifty-something, straight, cis-gendered, white guy is damn proud to be a member of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris’ legion of 75,000,000 sidekicks. I wanted a landslide last week. As the last votes peter in, it looks like they won the popular vote by 2.9%, up from Clinton’s 2.1% in 2016. That will do, but it’s nowhere near the double-digit wave of redemption I needed to feel good about my country. 70,000,000 Americans want another four years of Trump, either despite of or because of his bigotry and misogyny. A few thousand votes here, a few thousand votes there, and the Electoral College tips either direction.

That’s a brutal quarter edge to balance a nation.

Chris Gavaler's Blog

- Chris Gavaler's profile

- 3 followers