Moira Reid's Blog, page 2

August 20, 2022

What is Human?

Many of the things which we may think are activities only humans participate in are not ours alone. War, animal husbandry, and agriculture are all activities that many species of ants have as staples of their societies. No, the things that are most uniquely human are not strictly for survival in the ways that food production and defense of the colony are. There are many traits our species have that only we do, and they are largely a result of our ability to think differently than other creatures.

Our brains are designed to solve puzzles, connect patterns, and manage incredible details that for many organisms would seem completely without value. But that is not so. It is in using these unique abilities that we have become the species we are today. We have overcome trials that have left other apex species in the fossil record, and with luck and tenacity, we will continue to do so.

The first uniquely human behavior I want to address is the use of plants. That may seem a strange thing to bring up first. But this is more than simple agricultural usage. I’m talking about discovering the properties of plants and using them to our benefit. While ants have been seen growing fungi to provide crops to their colonies, and many species of mammals have been recorded consuming medicinal plants to deal with different ailments, only humans have discovered the means to identify those effects, and to harvest the ingredients needed to create more powerful tonics.

Our endeavor to understand plants has yielded the medical technology that we use today. Using this science has eradicated many harmful diseases, and others are now so uncommon that few people alive today have ever known anyone to be afflicted with them.

Plant usage extends beyond the medical and the food crop variety in human history. Poisons have been derived to aid in hunting and pest control. Plants have also been used to create a variety of tools used by both modern and ancient peoples. Ropes woven from plant fibers, resins harvested from conifer trees.

Even fire, considered mankind’s most important discovery, is bolstered by our usage of plants. Our kindling is properly dried grasses, and wood is the fuel. Certain woods such as hickory release flavorful smoke, that can be used to cure meat, increasing its self life significantly. And through the combination of fire and plants, humanity learned to extract plant oils, and create tinctures to cure ailments or reduce pain. This deep understanding, and resource management of plants is a uniquely human behavior.

For an action to be uniquely human, in my opinion, it must fit a level of scrutiny. Birds and many mammal species construct homes of wood or grass. Many creatures show signs of familial attachments, even social structures not too unlike our own. To be uniquely human, it must be more.

Language doesn’t even qualify. Whales show signs of using unique sounds and calls to signify names, places, even times. Chickens and geese will make noises to alert each other of approaching danger, predators, or food. Bees use a form of sign language via dance to indicate distance, position, and type of flowers to harvest for their pollen. There is one aspect of language that is uniquely human however: Writing.

The written word is among humanities greatest achievements. By recording knowledge, we are able to pass on what we have learned to future generations. This transmission of knowledge allows our species to continue in progress that would otherwise be impossible. Sometimes it can be generations before what was recorded before becomes usable, but by keeping these forms of records, our species can overcome the entropy of time that keeps many other creatures firmly held in their stasis of habitual living.

The first instances of recorded language date back to approximately five thousand years ago. This is not to say we as a species didn’t have great achievements before this advent. Human history begins long before that, with the first indications of civilization beginning roughly twelve thousand years ago. Even more than this, there is anthropological evidence to show that humans have advanced language and social structures as far back as sixty thousand years ago. Advancement in our species is multiplicative. Each one we make builds on the next ones, increasing the rate of development at every step.

Written language has shown significant improvement over time. Earliest records are difficult to understand, perhaps because we do not understand the context, perhaps because they were so rudimentary that they no longer show much relevance to us. Whatever the case, we have continued to improve our use of the written word as time has progressed. Interestingly, while written language is largely attributed to being first developed by the Sumerians, it appears to have developed independently among many different people around similar time frames in human history. It’s no wonder why the use of written language took such hold on our early species. It enabled people to learn new things without having to experience them first hand. It allows for greater specialization for our species. Writing may seem commonplace to us. We used it every day. But it is this commonality of the written word that solidifies it as one of the most uniquely human things you can do.

Along with this desire to record our experiences is the record keeping of our history. Where other creatures may find the bones of their forbears a warning to stay away, humans actively search these ruins for clues of where we came from. This curiosity is a unique feature of the human race. Now, do not confuse my words. This is not to say curiosity itself is unique to our species. Many creatures show curiosity. But the curiosity toward where we came from, what was once normal for our ever changing species, that curiosity is very human. It is hard to say whether this would occur in other species if they left behind the sorts of remains that we do; cities, monoliths, foundations. But so far, where other mammals have left foot paths through generations of use, there has been no sign of the deer or elk who walk them showing any more interest in them than simply to use them.

Even our own fellows may show such behavior. How often do we consider how the computer came to be? Yet many of us use them daily. So perhaps curiosity is more of a behavior engaged in infrequently, whenever the moment is right. Either way, it is because of the written word that whenever a human decides to chronical how something came to be, any of us can go to it and read it, discovering more about our heritage and place in this world.

Not everything that is unique to the human race is a positive. Alteration of our natural environments may be the first thing that comes to mind with this statement. However, this is not a uniquely human behavior. Granted, no species has had the same effect that humanity has had, with our production of plastics, abundant waste, and other ecological terrors, but it is the habit of almost all organic life to fill its niche as much as possible with its own, and to alter the environment to suit its needs along the way. Viruses and bacteria will do this so effectively that it kills their hosts with their waste products and chemical alterations. Some species will even fill their environment so much that they cause famine, leaving them with massive die offs and even extinction events. This is the balance of nature in action. No, what I am speaking of is cruelty.

Cruelty is callous indifference to or enjoyment of causing pain and suffering. You may think that other creatures also engage in this behavior; cats will play with mice before they eat them. But this is not the same. Applying the label of here simply anthropomorphizes the creatures. Humans have shown through their history that they will do much worse, for much less.

A perfect example is found in 19th century France, where a young woman, Blanche Monnier went missing for 25 years. After an anonymous letter came to local authorities, they searched the house of Monnier’s mother, to find that Blanche had been held captive there for that entire time. Her mother had imprisoned her over an argument they had had regarding Blanche’s desire to marry. Blanche was severely malnourished, and had not seen another person other than her abusers for 25 years. Blanche lived another twelve years after gaining her freedom, but the depravity of her mother remains a stark reminder that human beings, regardless of expectations or familial bonds, cruelty can come from any person, anywhere.

There are countless tales of killings, brutality, and horrifying acts by our species. However, another behavior quite unique to our own species is kindness. Again, this isn’t to say animals cannot show kindness. Whether they can or not is a subject for another debate. What I am referring to is how humanity has shown an incredible capacity to do good for their own species. There are anthropological records of human bones that have been broken, then reset, and allowed to heal fully. This is not an easy process. For most creatures, a broken bone is a death sentence. Whether their fellow creatures want to save them or not makes no difference, they lack the resources of intellect, dexterity, or understanding to help their fellows survive without putting themselves at risk. Wherever their is human cruelty, there is also human kindness that rises up to stop it. Our moral sense of duty, of right and wrong, and our capacity for empathy, allow us to see where there is hurt, and desire to correct it. To end suffering and bring safety and peace to our family, children, friends, and neighbors.

Overcoming hate allows us to achieve greater good for our entire species. There is nothing that humans cannot do so long as we work together. We’ve achieved space flight. We’ve cured previously incurable diseases. Extended the lifetime of our race by decades. Reduced child mortality the world over. But there is still so much to do. I encourage you to take time to find how you can help contribute to the end of cruelty. There is much every person can do in this effort to make a better future for our species.

June 28, 2022

The Erasure of Women

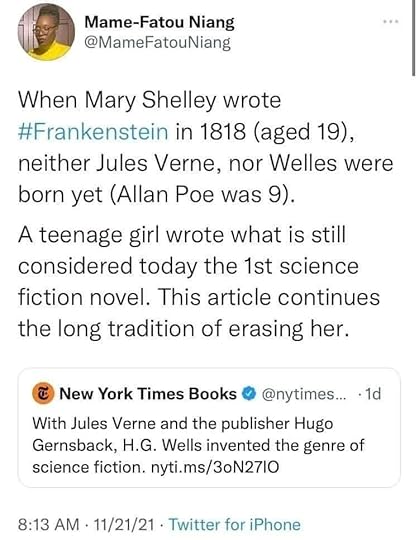

Earlier, I saw a Twitter post in response to The New York Times attributing the creation of Science Fiction as a genre to the author H.G. Wells. Not to diminish his success in the genre, but that attribution is utterly false, as most would agree, since the preeminent Science Fiction origin novel is Frankenstein, by Mary Shelley.

Along with this erasure comes the exclusion among many of the literati of the incredible impact of authors who are female. Octavia Butler, Ursula K. Le Guin, and Margaret Atwood all invested their extraordinary skill in the genre, showing visions of the future as poignant and vital as any other work. Where Fahrenheit 451 showed the dangers of myopic thinking and unchecked authorities, The Parable of the Sower did much the same, even getting closer to the dangers of such life by showing it from the perspective of people already at the mercy of great hardship rather than from the affluent perspective of a well-to-do person already high on the social ladder. Science Fiction has long been the means we as a society have used to explore the potential horrors of the future if left unchecked in the hands of those who view the humanity of others as less than themselves. These concerns and warnings are at the heartbeat of The Lathe of Heaven, The Handmaiden’s Tale, The Power, and The Hunger Games, all written by women authors, or as I like to say, authors. Yet our societies at large continue to hide these works away, calling them of less value than literary fiction for reasons never of any deeper explanation than a handwave.

Along with the erasure of women in literature, we are now also experiencing an erasure of women’s rights in the United States of America. The decision by the Supreme Court removed a long standing precedent of protections for women’s reproductive health. Some may think this does not affect them. Some may say these changes are a benefit, protecting the life of the unborn. However, the simple truth is that roughly one out of every four pregnancies’ ends in a misarrange, and of those , roughly one third will become septic and lead to the death of the carrying woman without the medical removal of the fetus. Access to safe, legal abortion protects women from the dangers of pregnancy, all pregnancy. It is not simply a medical procedure for destroying a fetus; it is one for securing the life of the mother. And the choice to obtain one should be the mothers own decision, as it involves their own mortality.

The disparity of equal treatment for women has been and remains a long battle, one we must all become advocates for. Every single person is affected by this battle, and we cannot stand idly by as the humanity of women and girls are stripped away by the powerful, disconnected few who claim authority. The freedom of our human species is common heritage. If allowed, the defunct, patriarchal, dogmatic insanity of the few will lead all of us toward an ever darker future, the very futures warned against in the novels of countless science fiction authors, both male and female; a future where the power of the elite is absolute.

We must stand together. We must rise together. We must all fight for the freedoms of every person. We have lived under this acceptance of treating any other human being as less for too long. Allowed concessions because we ignored the plight of people who present different than ourselves. This must end, or the warnings of our authors of Science Fiction, many of whom are and were women, will continue to come true.

If you want to take action, consider learning more here, and signing the petition. Improvement begins with you.

June 20, 2022

True Words

I

Have

Been

Meaning

To

Tell

You

That

There

Ain’t

No

Meaning.

Meaning

No,

Ain’t

There?

That

You

Tell

To

Meaning,

“Been,

Have

I.”

I

Have

Been.

Meaning:

To

Tell

You

That

There

Ain’t

“No.”

Meaning,

Meaning,

No

Ain’t

There,

You

Tell.

To

Meaning

Been,

Have

I.

I

Have.

Been

Meaning,

Too.

Tell

You,

That

There?

Ain’t

No

Meaning.

June 10, 2022

40 Winks

The sudden jolt of atmospheric entry jarred Adam to consciousness. He’d experienced it a number of times in his life as a xenominer, but from what he could tell no one ever got used to it. That life was long gone though. Adam looked at his hands; once the hands of an honest miner, now the hands of a murderer. It was an accident, he reasoned with himself, not murder. If I just went to work sober that day, I never would have… I would do anything to fix my mistake. Anything. Adam looked around to the other pods; beside him, in front of him, all around him, filled with people. They too were coming to their senses, some of them violently thrashing about from the “forty winks”, an illness caused from extended periods in stasis. Adam felt fortunate to have never come down with it.

The large prison vessel slammed vehemently into the surface of New Mumbai, sending up great plumes of the thin, dusty earth that barely supported the stringy grass fronds that dotted its surface. Its doors opened quickly, like the jaws of a great fish bellowing steam. Adam and the other convicts walked out, stretching their legs and straining to see in the low light of the daytime here on New Mumbai. The compound to be their home during their stay here was just to the north of them. Thin smoke trails ebbed out of it, curling across the sky and dissipating in the wind. Adam thought it looked like the pictures he’d seen of nineteenth century London during his studies of human history before his mining career. It even fit the greyscale of the old black and white photos.

“Quite lackluster,” Adam said aloud as he walked with the others, brushing his thin blond hair from his eyes. “If I say so myself.”

“You do,” Said the man just to his left, “I used to be a guard here about ten years ago. I kinda like it. Well, I did, anyways—guess I get to see what it’s like on the other end of the spectrum now eh? Hehe!” Adam looked at the man blankly. He thought about politely recalling his statement, but felt it better to say nothing instead. He couldn’t change how he felt; this place to him was very ugly in comparison to the many other worlds he’d been to; and knowing how all those places looked when the mining crews left, Adam thought the strip mining might actually do this place a favor. As they came closer to the colony, Adam saw the high walls and the heavily armed guards at the gates. He found it odd that a prison world would need walls or guns. The man to his left grinned at Adam’s expression of wonder.

“You’ve got a lot to learn about New Mumbai, friend,” said the man. “A lot.”

The group of convicts was brought into the city by the guardsmen, herding them like cattle. A small man, balding and old came out of a building across from where the convicts stood as they shuffled their light packs which they’d brought with them from the ship. This little man came toward them in a slow and halting saunter. Adam stared at this man with mixed feelings. Pity, for the man was maimed, but also fear, for the man’s face held some kind of anger which Adam had never seen. A murderous rage, so it looked. The man came to a stop just before the convicts and cleared his throat. Adam could tell now from his clothing, that this little man was some kind of warden for this prison. Adam looked at all the guards around him, noticing they had on strange black goggles and a tube coming from their noses going to a box on their belts. He deduced the tube and box must have been a respirator from the fact that he himself was having trouble breathing the thin air around him.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” the little man before them said in a very clear and ringing voice, “I am Colonel Towers. Welcome to New Mumbai. You all know why you’re here. You’re here so that the rest of humanity doesn’t have to worry about scum like you.” Adam felt the words sink into his heart. Silently he agreed to those words. He recalled the face of the man he killed; just another miner, like him. He wondered if the man had a family. Forgive me, Adam thought, or can I even forgive myself? He then realized that Colonel Towers was still speaking.

“… As such you will be issued the equipment you need to survive in this environment,” Towers said. “You only get one set, so take care of your equipment. I’m sure you’ve noticed the walls as well. This is not to keep you in. It is to keep them out.” Adam’s mind raced at the words. Them, thought he, who is them? “On this world is a very dangerous creature. Far worse than any of you, I guarantee it. Folks around here have grown to call them Fiends, because of their bad temper and disfigurement. They can appear and disappear out of thin air. They will kill anyone and anything outside of these walls at sun down. They’re not an animal either. Not by a longshot. These things are very advanced and will hunt you down like a cat with a mouse. Keep that in mind. This is my prison, you are my prisoners. That is all.” Towers wiped the back of his hand under his nose, knocking the tube loose on accident, but quickly replacing it. The other guards forced the convicts on again, feeding them into steel chutes which lead deeper into the facility which was to be their home.

Adam, like the rest, was given a respirator and a pair of goggles.

“What are the glasses for?” Adam asked the guard which gave him his pair.

“It pays to listen to what the warden says, puke,” The guard responded. “They help you see in the lowlight here, and they help you see the Fiends when they’re on the prowl out there in the wastes.”

Adam swallowed hard. He quickly put the goggles on and attached the respirator to himself. Rich air filled his lungs and bright light flooded his eyes. He squinted for a moment, and heard the guard laughing loudly at him. The guard hit him in the back with his baton.

“Move it,” The guard said coldly, hitting Adam again. Adam cringed away and continued down the hall before him. The cells they were assigned were small and cold, one man to each cell. Adam sat quietly in his own cell on the second level, watching as the other inmates were brought in to their own rooms. When the last man was placed, the bars slammed shut in perfect unison. Adam could hear Colonel Towers’ voice again ringing from the floor below. He went to the bars and looked down at the little man.

“Listen up!” Towers yelled, his voice echoing off of the walls of the prison. “We run a very tight ship here on New Mumbai. That being said, you can see we’ve only got a handful of guards on duty. None of us will be here during the night. You’re all on your own until sunrise. Don’t try to get out of your cells though, because we’ll be releasing the Ghoul in here when we leave as well.” Two guards walked in as Towers spoke dragging a creature on a rope. It was as tall as two men, with its hands dragging the ground. It bucked and reeled, trying to free itself from its captors. Adam had heard of Ghouls, but had never seen one. It frightened him, with its pale skin and hairless head. Adam had heard that Ghouls were failed clones of human beings, but that they were disposed of in humane ways. Seeing one like this made all that was good inside him cry out for justice. How could the very system which condemned me rightfully allow such a wrong as this to be done to an innocent life? Adam asked himself as he watched the tormented Ghoul howl and wale below him. Before the guards released the creature from the rope, the beat it with their batons; the warden, Towers, stood and watched with an air of satisfaction as his men brutalized the creature.

When the guards left, the lights went out in the prison also. The quiet crying of the wounded creature below resounded through the halls like wind through the forest in fall. Eventually it ceased. Adam lay awake for many hours in his bed, thinking of his life. Suddenly he had the feeling he was being watched. He sat up in his bed, and there at the bars stood the Ghoul, looking in at him. Its eyes starred cold and black at him, its mouth slung open in a long frown. Adam was frozen with fear.

“You asleep like the others not,” it said. Its voice reminded Adam of a miner who had inhaled dust for a number of years; that hoarse, graveled sound of lung damage. Maybe it was the calmness of its voice, or the sadness thereof, but somehow when it spoke it made him feel at ease.

“No,” Adam replied quietly. The creature began to shed tears, or so it seemed. Perhaps that was only because it had no eyelids.

“You afraid of me anymore not?” It queried.

“I’m not sure,” Adam said in reply. They looked at each other without a word for what felt like an eternity until the Ghoul spoke again.

“You a not murder maker.” the creature said. “It an accident was.” Adam was taken aback by its statement.

“It was an accident,” Adam said in almost a whisper, “a stupid accident… How did you know?”

“I could feel you thinking when I walked,” It replied. For some reason which Adam never could explain, the creature’s statement didn’t frighten him at all. If anything it made him feel as though it was a friend to him.

“Do you have a name?” Adam asked the Ghoul.

“Me Meat, so called I am.” Adam spoke with Meat for many hours after that, and learned much from it. It had been here for many years, and the guards—Colonel Towers especially—beat it often, and withheld food from it. Adam felt compassion for the Ghoul.

Adam awoke the following morning to the harsh buzz of the alarm as the doors opened to the cells of the prison. He rolled out of bed and approached his door, as he was instructed to do the day before. He heard Meat screaming, and looked down to see it being dragged out by a rope of the lower room. Towers then barked orders for every convict to make their way to the mess hall. Adam overheard many of the other prisoners speaking while there, and saw some of them pointing at him. They were talking of how the Ghoul stopped outside of his cell last night.

“Why is that odd?” Adam finally interjected. The more senior convicts looked at him with mocking eyes. They waited a moment longer to respond, enjoying the suspense their hesitation created.

“Because the Ghoul eats convicts, knuckle brains,” one finally said to him, “And it always picks a new meal from the new bunch.” Adam was surprised at that response.

Adam spoke with many of the other convicts during the meal. He learned that most of them hadn’t done anything at all; some of them were just too poor to pay taxes, so their governments sent them here instead. Others had gone to sleep in stasis on their way to vacation, and awoke here. Adam found that troubling. After their meal time the convicts were released out into the dusty plains of New Mumbai. Guards went out with them, each with large rifles. The day went on slowly for Adam. The inmates were given very hard tasks to complete, and it drove many to madness. Adam was used to hard labor from his former employ. At the end of the day, however, he could never recall what it was he and the others had been doing. He knew it was extraneous, but all detail had slipped from him. It was like they were being drugged to keep them in the dark, but he had no way to prove it.

Games and sports were prohibited, and the guards had no qualms with beating anyone who violated the rules. In fact, they had no qualms with beating anyone for any reason; or even no reason at all. Adam was no exception. On the first day he was assaulted by what seemed to be every guard at one time or another. Some of the other convicts told him it was a sort of initiation. As the sun was starting to go down on that first day, a squealing alarm sounded from within the walls of the prison. All the senior convicts ran violently towards the doors of the prison, pressing against them trying to get in as fast as possible. Adam followed suit, and listened to the intercom announce that the Fiends which Towers had spoken of were coming. Adam looked back as he entered the prison, and saw creatures, like men, but squatty, loathsome animals, approaching quickly towards the doors. He knew right then that he never wanted to be outside when the sun went down.

Days passed, then weeks. Adam began to think this place was more an internment camp than a prison. Occasionally Adam would hear the wales of the Ghoul as it was being beaten by the warden or whoever it was doing it. He wanted to help it, but what could he do? Every night, Adam and the Ghoul would talk for a few hours, and every night Adam would see new bruises on its gaunt frame. Adam thought a lot about what the other convicts had said, but didn’t want to believe it. Finally one night as they spoke he worked up the nerve to ask Meat.

“Meat?” Adam timidly asked.

“What is, Adam?” Meat replied.

“Do you… Do you eat convicts?” Adam felt ashamed, and thought it impossible that such an innocent creature could do anything so awful. The reply however filled Adam with dread.

“Who told you?” Meat said, its voice quivering as if it were ashamed of the fact. Adam felt the blood drain out of his face. “I’m… I’m proud of it not. The guards feed so little, and I so hungry that I feel like I to die! I just so hungry. So hungry…” Meat looked down, away from Adam. Then it looked back at him again. Adam was speechless.

“I know what you thinking,” It said to him, pawing at the door to his cell. “I always know what everyone thinking.” Meat walked away, whimpering quietly as it did. Adam was afraid, but felt bad for it. This time he rose and watched as Meat left; he wanted to see where he was going. Meat went down the stairs to the left, to the first level, and stopped at another cell door. It didn’t move at all, it just stood there, looking into the cell below. Adam watched for a while, and then went back to bed.

In the morning, when the buzz sounded and Adam went to his door, he looked down in horror to see bright red blood pooled around the door where Meat had stood. The warden, Towers, approached the door and said loudly, “looks like old Meat got another one boys!” Adam stared at the blood in the cell below, entirely beside himself. Days passed still, but Meat didn’t come to Adams door anymore.

Everything seemed to be getting worse and worse here on New Mumbai. Fiends without the walls, the Ghoul within; and it had taken a liking to him. It sure is hungry, Adam thought to himself, his heart sinking in his chest all the way down to his feet. He didn’t want to die. Coupled with the needle marks he often found on his arms, and have no recollection of where they came from, made him feel he may as well be dead. His head felt clouded, like murky water filled with secrets just below the shimmering surface. Adam found it hard to sleep at night for fear of the Ghoul. He lay in bed, his eyes flashing down to the cell door, always on guard, until he would fall asleep. Every evening Adam would flee before the Fiends, as would all the convicts, and every night he would wait for Meat.

Adam awoke to a rattling at his door. His eye’s quickly opened, and he could tell it was still very late. He looked down, and there stood Meat, peering in at him. Adam rose and cringed into the corner of his room, hugging his thin sheet to his chest in futile defense. Meat whimpered at him.

“I so hungry,” It said to him sadly. “I know you good man, inside, but so hungry.” Meat reached its long arm between the bars of the door, groping for Adam. Adam darted across to the other side of the room, but Meat’s reach was still enough. It ensnared him and began to drag him by his foot towards the door.

“Please,” Adam said, “Please don’t do this! There must be some way I can help you, just please, don’t kill me… Please.” Adam began to cry great tears of sorrow. Meat stopped pulling him across the floor, but let him go instead. It too cried for a short while.

“No,” Meat said, “I eat you not. You heart, you spirit, good man. I hungry, yes, but you help me and I help you.” Adam looked at Meat for a moment longer, then stood and approached it.

“What do you want?” Adam said.

“I see what you never see. I see with my eyes. When sun rise, and go you out to wastes, you see with you eyes too. And when you see, don’t run away. And when you helped, you come back for me?” Adam didn’t quite understand what Meat meant, but he nodded. Meat then smiled, the first time he’d ever seen it smile, and then it left.

When the sun rose that day, Adam still didn’t know what Meat wanted him to do. He wandered around thinking about it over and over, trying to grasp the meaning of its words. The day past quickly to Adam’s dismay, and the alarm sounded of the approaching Fiends. Instinctively, Adam ran with the others, looking back and catching glimpses of the terrifying apparitions behind him. Suddenly it struck him to remove the goggles he’d been given by the guards when he’d first arrived. He’d been wearing them night and day since then. He pulled the goggles off, and looked back again. He stood still, the goggles dropping from his hand as he stared at what was before him; ordinary people, running and yelling for the convicts to follow them. Adam continued to stand for a moment, and then ran towards the multitude of Fiends. One of the guards from the prison shouted and shot at Adam, barely missing him with each shot. The group waved him in, wheeling their arms; they cheered and encircled him as they turned about, running away into the gathering dark of New Mumbai.

Adam awoke in a small room, very much like his cell. At first he thought it all had been a dream. He heard whispering nearby, and sat up to look. There in the room with him were a number of people in white clothing, looking at him with passionate gazes. A taller man came forward and kneeled by the bed where Adam sat.

“My name is Walton,” the man said. “And you are?” Adam told the man his name, and who he was: a convict. Walton looked at Adam for what felt like an hour, but what was only two minutes, at most.

“Who are you people?” Adam asked.

“We’re relief workers,” Walton replied. Adam was perplexed. “That place isn’t a normal prison. It’s… A place where people of demented tastes go, to hurt others. Everything you experienced there was a lie, twisted by the lenses they made you wear. Do you remember anything unusual? Losing whole days, or waking up not knowing what happened to you?

“I do,” Adam said, rubbing his arms.

“We’ve been trying to get people out of there for years,” Walton continued. “Most of the ‘convicts’ in there aren’t even criminals, just people who were unfortunate enough to end up there. It’s an evil place. We’re glad we got you out. We’ll get a shuttle here to take you away from here.”

Walton motioned a nurse to come closer, but Adam protested.

“I have to go back,” Adam replied. Walton looked at him with bewilderment.

“Maybe you haven’t understood what I’m trying to tell you,” Walton said.

“No,” Adam repied, “I’ve understood you perfectly.”

“They’d kill you on the spot!” Walton blurted, “You cannot go back there. You’re the first person we’ve ever managed to rescue from that place; you represent the evidence we need to shut it down, for good. You have to understand.”

Adam burst into tears; for his freedom and his folly.

“There is a friend in there that I must keep a promise to,” Adam replied as he stood up from the bed, headed to the door.

May 26, 2022

The Vicar

A priest, a grocer, and a butcher lived in a shared apartment on Wallace and Third. It wasn’t much, but for the three humble men, it was home. They shared all they had with one another, which also wasn’t much, each man being devoted to the public service of their rural community, giving what they could where they could.

The butcher often had meats left over at the end of the day too close to spoiling, so he would bring them home for his fellow roommates. The grocer had similar supplies of fruit and vegetables which were soon to spoil as well, yet even with their attempts to preserve these foods, it would frequently go bad before they could eat it all.

One day, the priest offered an idea: they could obtain a chest freezer to store the foods in, keeping them fresh for longer. After sharing his idea with his roommates, they all agreed it was the right move; so, after reaching out to his congregation, the priest was offered a refurbished freezer as a donation.

The roommates were pleased. It was a small freezer, but it fit well in their humble home, and provided the storage they needed. Over the next few days, they enjoyed many a meal, more than they had previously been able, as the freezer kept their supplies fresh, and flavorful.

But the freezer was old, and out of the blue it stopped working while the priest, the grocer, and the butcher were all out of the house, doing their daily work. When they returned that evening, the food had all gone bad, and the house was filled with the smell of rotten meat and vegetables.

The butcher and the grocer’s tempers flared before the mess of spoiled food. The grocer blamed the butcher for over stuffing the freezer with meats. The priest stepped in, trying to salve the argument, but as he did, the butcher blamed the priest, saying if he had gotten a better freezer, none of this would have happened. Their argument went on for hours, until finally, they decided they could not come to a satisfactory answer of who was responsible on their own. The priest called his friend the judge, and asked if he could assist them in the debate.

Within an hour, the judge had arrived, and by that point the smell of the spoiled goods had become quite strong. Each roommate shared their feelings on the subject; the grocer blamed the butcher, the butcher blamed the priest, and the priest blamed the grocer. After only a few minutes the judge raised his hand and declared he had an answer: the priest was responsible.

The priest was shocked. He asked how it could possibly be his fault; he had only provided the freezer, and it was in good condition when he brought it in. It was the grocer and the butcher who had filled it to the brim, had pushed it to its limits. But the judge was not swayed in his verdict.

After all, to the Vicar goes the spoilage.

May 20, 2022

Cosmology of Consciousness

Since the times of antiquity, humans have wondered about the world around them. They observe natural phenomena, study the patterns created by them, and attribute meaning to them. Where understanding fell short, metaphor filled in nicely, giving rise to many philosophies the world over. This sense of wonder remains with us in our time, although we have the luxury of access to thousands of years of human observation, allowing us to make up better stories about how the universe works. The sun is not a chariot of fire pulled by the god Apollo, it is a massive sphere of hydrogen, fusing together in terrible splendor into helium, casting out light, heat, and energy. These stories, while appearing different on the surface, serve the same purpose: humans using their observations and the language they have at their disposal to describe their world. In our modern day, we have access to so much information that it may seem the time of mystique is behind us, however, authors, especially those of Science Fiction, retain the human heritage of exploring the unknown in the universe with the language we have available. Just because many old mysteries have been solved does not mean that there are no new ideas to discover or explore. Ursula K. Le Guin and Philip K Dick were two titans in this pursuit, especially in the undertaking of defining consciousness through their work. The workings of consciousness are still something we understand extraordinarily little about through our scientific breakthroughs, which makes discussing it in fiction a great way to reach for the metaphor in language we need to understand it better. This is just what Philip K. Dick and Ursula K. Le Guin did with their work, especially in the matter of dreams.

In The Lathe of Heaven, we are introduced to George Orr, who has what are called “effective dreams.” In this dream state, he is able to alter the reality of the non-dream, physical world, often in dramatic ways. He is assigned to a psychiatric doctor to help him with his drug usage, a habit George has picked up to cope with his reality altering dreams, yet Dr. Haber becomes aware of his power and begins to use it to shape the world as he sees fit. Throughout the novel, the reader is introduced to a number of interesting pieces of information. For one, we discover that George experienced a nuclear apocalypse at the start of the novel, wiping out nearly, if not all life on earth (Le Guin, Ursula. 1971). Yet, as he lays in his irradiated blindness, he effectively dreams of a new reality, one where the bombs never fell. It is after entering this new world that George is forced to meet with Dr. Haber. The book is filled with surreal moments, yet one that stands out is George’s discussions on purpose, and the nature of the universe. Dr. Haber begins one of his meetings with George by saying that he believes it is mankind’s purpose to improve the world. He then asks George what he believes its purpose to be. George says, “I don’t know. Things don’t have purposes, as if the universe were a machine, where every part has a useful function. What’s the purpose of a galaxy? I don’t know if our life has a purpose and I don’t see that it matters. What does matter is that we’re a part. Like a thread in a cloth or a grass-blade in a field. It is and we are. What we do is like wind blowing on the grass, (pg. 82, italics in original).” George makes an interesting distinction here between prevailing western ideals of the conscious self and those eastern, Taoist ideals. Where the former focuses on the singularity of the individual, the latter explores the connectivity between the self and the other, forming a tissue of many ‘ones’ who are in fact one. Like the thread in the tapestry, the concept of self is instead moored in a sense of collective oneness.

George continues to add to this concept as he struggles with the loss of personal freedom administered to him by the ever growing ego of Dr. Haber. One evening as he walks home from the shop of an alien junk peddler, he thinks, “… the whole world as it now is should be on my side, because I dreamed a lot of it up, too. Well, after all, it is on my side. That is, I’m a part of it. Not separate from I. I walk on the ground and the ground’s walked on by me, I breathe the air and change it, I am entirely connected with the world.” This connection in context of the text lends toward a sense of the connection between people and the world. George finds that the alien beings know him, and his ability, which they call iahklu’. Exactly what that word means is left to reader interpretation, yet it is heavily implied that it is the state of effective dreaming, and that the alien beings live in that state always. They also appear to be coterminous with one another, sharing experiences with one another.

The aliens in The Lathe of Heaven are a part of the fabric of the reality of the book. Just as is George Orr, and the entirety of earth. This fabric of reality, where all things are connected, are an echo of the words of Lao Tzu, who is credited with writing the Tao Te Ching. In it, Lao Tzu states, “Heaven will last, earth will endure. How can they last so long? They don’t exist for themselves and so can go on and on. So wise souls leaving self behind move forward, and setting self aside stay centered. Why let the self go? To keep what the soul needs,” (Tzu, Lao). Both speakers are saying a similar message of oneness found not in the selfish pursuits of life, but in the path of accepting the simplicity of life. What Lao Tzu calls the Way, George Orr calls stillness. These relationships in philosophy are apparent throughout the text, with references to the writings of Chaung Tse, another prominent voice for Taoism contemporary to that of Lao Tzu. There is, however, another way to interpret these pieces of information in The Lathe of Heaven: that everything which takes place in the book is an extension of George Orr. After the bombs fell and he dreamed into reality a new world free of the nuclear destruction, he becomes the choke point of a new reality, the wellspring from which all things form. Dr. Haber exists because George wanted someone who could help him, and while his methods are dangerous, he does help George become free of his effective dreams. Yet even with this interpretation, it changes nothing for the application of Taoist principles. George was already a part of the whole, containing the pieces of the universe within himself before the first destruction of the novel. Whether the new reality springs from him or from the continuity of the universe, it is the same. It is interesting to note as well are the implications of George Orr’s name. Some studies of the novel have suggested that Le Guin chose the name as an allusion to the novelist of 1984, George Orwell, who many view as having had a ‘vision’ of what could be if totalitarian regimes were allowed to get their way (Malmgren, Carl. 1998). By dreaming worlds, George creates paths out of disaster. It isn’t until Dr. Haber takes full control of the effective dreaming that things become dangerous to the point of the near total destruction of the human race. Some see the character as a parallel to the author, both providing the cautionary ‘vision’ humanity needed to avoid total destruction.

These elements connect as well with the works of Philip K. Dick. In Valis, the character’s Philip Dick and Horselover Fat both describe dreams of other lives, lives they believe they have lived, or will live. In the novel, the character Dick records the following regarding these dreams:

Dreams of another life? But where? Gradually the envisioned map of California, which is spurious, fades out, and with it, the lake, the houses, the roads, the people, the cars, the airport, the clan of mild religious believers with their peculiar aversion to wooden cradles; but for this to fade out, a host of inter-connected dreams spanning years of real elapsed time must fade, too.

Dick, Philip K. 1981, Valis

Both Philip and Horselover, who themselves are alluded to being a shared consciousness of a single person, experience these dreams of other lives. These dreams form a web of connectivity, which according to Horselover are evidence of not only other lives lived, but other times lived, even other timelines of reality relating back to the time of Christ and the first Christians. These relations of time and understanding of it in relation to consciousness are revealing of these concepts of consciousness already discussed. The line between one person and another is relatively thin, and with the right conditions those lines can be crossed (Cannan, Howard 2008). Whether it is through dreams of other worlds, manifestations of Christ through different people across different times, or even the sci-fi film in the novel by the same name of Valis, these all indicate a thread of connection across people and times. The novel can be used to explore these concepts for the reader; how does consciousness happen for us? And to what degree are we living in a world not too dissimilar from the ones described in these novels?

Dick also explores this in The Man in the High Castle and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? In the first, we find the character Tagomi, who faces a crisis of identity after having to kill two men, is seeking something that can give him a return to meaning and self. He receives a unique pin and contemplates it, whereupon he is taken into another reality, one where the axis powers did not win the Second World War. This transition of worlds also shows a concept of the thinness of the line between concepts of reality. The concept of parallel timelines, or counterfeit realities, present in The Man in the High Castle also show principles of understanding reality in different lights (MacFarlane, Anna. 2015). Our ability to conceive of different outcomes appears in many respects to be innate, and using such concepts in the telling of stories allows us as a species the catharsis of experiencing the dangers of what could have been, just as George Orwell’s novel postulated a terrifying future, and, anachronistically viewed from our own time, a potential future, one which most of the human race would rather avoid. Indeed, the careful application of SF in literature allows for the exploration of these concepts so that readers, and the world, can see potential threats to us, and avoid them.

These concepts are united between Le Guin and Dick’s work (Watson, Ian. 1975). The SF author, especially these two authors, can imagine different worlds. Different timelines, and different threats to our species, are all on our minds as a collective organism going into the future of our technological advances. We are facing many challenges, Climate Change, pollution, political upheaval, and wealth disparity as well as bigotry, racism, and sexism. These challenges are real to us, just as they were in the days of Le Guin and Dick, and their work explored those fears, giving voice to the “what if” of coming days. This even comes up in The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, where consciousness and reality are again challenged by the effects of Chew-Z. From the first exposure to the drug on, the story is unclear whether we are in the mind of Leo Bulero or not. And that in essence does not matter, because with the concept of human consciousness being explored as a continuum rather than many unique points, Bulero is an individual and the entire human race all at once. This comes back to the end of The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, where people who have not even taken Chew-Z are experiencing the effects of it; it is possible it is leaking through the fabric of the conscious minds of the human race, connecting them.

In Androids, the people of the world frequently use what is called an Empathy Box to connect their minds to one another, to share experiences and to commune with a neo-messiah figure known as Mercer. This connection across the distance of personal self-consciousness is another place where the reader can observe the thinness of the line between one mind and another. The concept of the individual breaks down in these explorations, opening up a space where it is possible to be oneself and someone else, all at once. Indeed, by the end of Androids, Rick Deckard has become Mercer himself. For much of Dick’s work, the presence of these unique radio technologies act as a bridge between minds (Hulbert, Adam. 2016). The transmission of signals via a device allows for greater reception of signals to the human psyche. In essence, acting as a technological evolution along the path to enlightenment for the human race.

These connections to Taoist concepts of self are tropes of SF, and not knew ones (Huang, Betsy). Many authors have used eastern philosophy to explore new concepts for the western world, and have done so with great effect. One such example, Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End, shows that this connection of consciousness may not only cover the human race, but many others, across the universe. It is described in that consciousness is like a great ocean, with many islands. While the islands appear separate, if you removed the water, you would find they all are connected to the same earth. In Childhood’s End, humanity is on a path to become one with that universal consciousness, propelled along by the aid of servants of that consciousness. Some could read the story and find it bleak, an end to our species, absorbed into the consciousness of another entity. However, I find this not disturbing when viewed through the Taoist lens of consciousness, the self, and reality. There was no line between humanity and the greater consciousness to begin with; it was the next natural step of evolution in becoming one, becoming whole.

Le Guin explores these concepts once more in The Dispossessed, albeit in another, more subtle way. In this novel, there is a concept being explored in Physics called Simultaneity. This principle means that all things are happening at once in the universe, that all things are connected, and if one could understand how it is so, they could not only communicate across infinite distances instantly, but could even theoretically travel those distances just as fast. The character Shevek spends a great deal of time on the matter, describing in several places that the past and the present are all part of one great whole, not separated at all, simply only visible to us from our meager range of view where we happen to be along the spectrum. This principle of Simultaneity connects with these concepts of the principles of consciousness. All things exist at once, which would undoubtedly contain the conscious minds of every person in that oneness.

Even in Le Guin’s later work, such as Changing Planes, we continue to find these concepts of connectedness in consciousness. In one chapter, a people called the Frin share their dreams, forming a web of linked thoughts in their sleep. They do not view the dreams as one person’s or another, but as simply the dream; the one they all had. The Frin can even share dreams with other people not from their plane. However, those from other planes cannot share the dreams of the Frin. It becomes a point of contention in the story that the dreams of other planes are bringing with them ideas foreign to the Frin, ones that may even be overriding their own social development. In this situation, it could be interpreted that the story is an exploration of invasive cultures, such as those of the colonial era of the 16th century (LeRoy-Frazier, Jill. 2016).

Even more modern SF authors continue to explore the elements of consciousness. Andy Weir wrote in his short story The Egg of a concept of reality where all people on earth are in fact just one entity, the child of a deity, experiencing all of reality from beginning to end in an effort to mature into a deity themselves one day. His short story has leveraged a great deal of acclaim over the past few years, with a reference to it even appearing in a hip-hop album the artist Logic. SF provides a unique place for readers and authors to explore what it means to be human, especially in our day of increasing technology and shrinking borders. As we progress as a species, our boundaries of nations grow thinner, with new ideas entering our minds from all over the world daily. A person in Iran can speak instantly with a person in Canada on topics of Greek Philosophy, astrophysics, or romantic poetry. Already our barriers are coming down, much in the ways described by Dick, Le Guin, and Lao Tzu. As we progress, we are forced to observe reality with eyes of our similarities, with an understanding that even though we are all individuals, we are one species, one race, one earth.

Works Cited

Canaan, Howard. “Time and Gnosis in the Writings of Philip K. Dick.” Hungarian Journal of English and American Studies 14.2 (2008): 335-55. Web.

Clarke, Arthur C. Childhood’s End, Ballantine Books (1953). Print.

Dick, Philip K. Valis. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Trade & Reference, (1981). Web.

Dick, Philip K. The Man in the High Castle. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Trade & Reference (1962). Web.

Dick, Philip K. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Doubleday Publishing (1968). Print.

Huang, Betsy. “Premodern Orientalist Science Fictions.” Melus 33.4 (2008): 23-43. Web.

Hulbert, Adam. “Elsewhere, Elsewhen and Otherwise: The Wild Lives of Radios in the Worlds of Philip K. Dick.” Journal of Language, Literature and Culture (Australasian Universities Language and Literature Association) 63.2-3 (2016): 164-78. Web.

Le Guin, Ursula K. The Lathe of Heaven: A Novel. Scribner Trade, New York: Scribner (1971). Print.

Le Guin, Ursula K. The Dispossessed, Harper Collins Publisher Inc (1974). Print.

Le Guin, Ursula K. Changing Planes. 1st ed., Harcourt (2003). Print.

LeRoy-Fraizer, Jill. “Travels in Subjectivity: Post(Genomic) Humanism in Ursula K. LeGuin’s ” Changing Planes”.” Mosaic (Winnipeg) 49.2 (2016): 95-111. Web.

Malmgren, Carl D. “Orr Else? The Protagonists of Le Guin’s The Lathe of Heaven.” Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts 9.4 (1998): 313. Web.

McFarlane, Anna. “Sideways in Time: Alternate History and Counterfactual Narratives, University of Liverpool, 30-31 March 2015.” Foundation (Dagenham) 44.121 (2015): 79. Web.

Watson, Ian. “Le Guin’s Lathe of Heaven and the Role of Dick: The False Reality as Mediator.” Science- fiction Studies 2.1 (1975): 67-75. Web.

Weir, Andy. The Egg. Galactanet (2009). Web.

April 21, 2022

Look At Your Hands

I have lived on a farm, not just visited.

I have trudged through great mountains of pig shit, pled

With a damn milk cow as she stood on my foot

For four gallons of sweet cream, as white as sand

On Ozarks levee.

I have made salt butter and cream cheese, pressed

The cloths of thin whey, and drank the honeyed

Cider from apples of Autumn’s dry boot,

And heard music from a festival band.

You are same as me.

The rain that melted the cotton castings bled

The choked city gutters all the same, and fed

My fields and your fair parks where birds sing like flutes.

Work in slick mud or cold offices takes hands

Of natural men.

Pastoral poetry is particularly interesting to me. I spent my high school years living on a farm my father bought after he retired from the Marine Corps. We had cows, chickens, pigs, and grew crops. It was hard work, and in many respects it was enjoyable, but now that I’ve lived on both sides of the concept, the city and the farm, I find that the similarities outweigh the differences. No matter where you live or what you’re doing, you’re working hard and often in situations that you do not enjoy.

Many pastoral poems romanticize the idea of the rural because the poets went there on vacation. It isn’t so much the place itself that holds the wonder as it is the experience of being somewhere not as familiar. Granted, there are aspects of rural life that strike a chord in the human heart, such as proximity to the natural world. Those experiences are not as common in the city, and therefore being near those in the rural world does hold some mystique. The love of nature present in pastorals is present in my poem, but also the difficulty, the hardship of dealing with livestock.

There are many wonderful things in the rural life, like visiting levees, drinking fresh fruit juice, going to small town festivals. But the difficulties of shoveling shit, struggling with massive creatures for their products, those are also present, and create in my mind a paradigm that life in either the city or the country are relatively the same, just with different set pieces.

I reworked this poem after taking revision notes from a collective of fellow poets. A major note I was given was to include another verse, to flesh out the concept of sameness. I also cleaned up the form so that the second stanza is reflective of 10 syllabic lines, while the first and third have 11. The original poem is below. I also changed the title of the piece, to reflect the association with the hands that do the work in the poem, both in the cities and in the farmland.

Waking to The Pastoral Dream

I have lived on a farm, not just visited.

I have trudged through great mountains of pig shit, pled

With a damn milk cow as she stood on my foot

For four gallons of sweet cream, as white as sand

On Ozarks levee.

I have made salt butter and cream cheese, pressed

The cloths of thin whey, and drank the honeyed

Cider from the apples of Autumn’s dry boot,

And heard the music of a festival band.

You are same as me.

April 16, 2022

Let’s Review: Amitav Ghosh’s The Great Derangement

Author Amitav Ghosh begins their essay The Great Derangement with a review of the human condition; how we as a species respond to the world around us, especially when it defies our expectations. With the line, “who can forget those moments when something that seems inanimate turns out to be vitally, even dangerously alive?” (Ghosh, pp. 3) Ghosh begins our journey into understanding that the environment is irrevocably a part of our social and biological make-up. How could a person start at the sight of a log which turns out to be a crocodile if they did not know what a crocodile was? In that situation, the offending person would fall prey to the reptile, and the other humans around them would then be engendered to that environment with the memory of their screams. It is experience with the places we inhabit that provides the context for our experiences in them.

Amitav Ghosh tells how their forbears were inhabitants of a region of Bangladesh, near the Padma River, which is observed to change its behavior and the landscape around it rapidly. This change informed their ancestors’ understanding of the region, and their own understanding of the region as they continued their research on it. “Recognition is famously a passage from ignorance to knowledge,” (pp. 4). They continue with the paramount importance of recognition; it is not to be confused with comprehension. It is more instinctual in nature, coming to your senses to what dangers may be around you based on what you or your community may have faced previously. Ghosh then applies this experience with the rising evidence of climate change facing our species globally right now.

The ancestral region of Ghosh’s people acts as a microcosm of climate change effects, because of its already volatile nature to change rapidly. However, with the growing evidence of climate change, there has not been an increase in recognition of the dangers of it among the human population at large.

There is something confounding about this peculiar feedback loop. It is very difficult surely, to imagine a concept of seriousness that is blind to potentially life-changing threats. And if the urgency of a subject were indeed a criterion of its seriousness, then, considering what climate change actually portends for the future of earth, it should surely follow that this would be the principal preoccupation of writers the world over—and this, I think is very far from being the case. (pp. 8)

Ghosh then goes on to explain that the western world is avoidant of this recognition likely because of what drives its society. The concern is less about the environment in which people live and more about what they use in their daily lives. Commodities have become their forests, gasoline their rain, smart phones their foraged produce.

This disconnect is likely fueled by the corporations which act as the quasi-governing forces of the western world. They determine many policies through their generous donations to legislatures, taking a stranglehold on the world’s resources through their power and authority gained via their peddling of products to the common people. Regulations that would act in response to climate change, that would recognize them, would cause those corporations to lose wealth. So they hide from them. It is this hiding, this denial, which Ghosh draws from to coin the phrase, “The Great Derangement.”

These tactics are not new. Many societies have employed propaganda in their communal share of information to either prevent or protect their citizenry from knowing of things which could harm them. For instance, World War II Britain told their citizens that eating carrots would improve their eyesight, when the real driving force here was to encourage them to grow their own foods in the face of shortages, and to hide their new radar system from the Germans by saying their pilots could simply see in the dark, which was why they could shoot down German planes with such accuracy( Spring, K. pp 323). These tales, while not new, have likely led to our current situation of continuing the obfuscation of the dangers facing us. Like it or not, the climate is changing and has been linked to human intervention. Our collective hiding from this fact will not serve us well and could result in the culmination of our extinction.

Works Cited

Ghosh, Amitav. The Great Derangement, 2016. Chicago Press

Spring, Kelly. Today We have All Got to be Fighting Fit’: The interconnectivity of Gender Roles in

British Food Rationing Propaganda during the Second World War. Gender & History,

Volume 32 (2). Pp. 320-340.

March 31, 2022

Putting the LGBTQ in the Literary Canon

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick wrote extensively on the place of homosexuality in the literary canon, especially in the authors thereof. The evidence of this lifestyle is apparent in some cases quite clearly, in others more obscured, but in most cases, hidden from the public view due to prevailing sentiment that homosexual lifestyles were wrong by the majority rule of white, cis male, heterosexual literary elites.

Two novels referred to by Sedgwick, Dorian Gray and Billy Budd, provide “a durable and potent centerpiece of gay male intersexuality and indeed [have] provided a durable and potent physical icon for gay male desire,” (Sedgwick, Eve, pp 183). The stories follow people living in lifestyles of homosexual desire, and the struggles which erupted from the societies around them as a result. Recognizing the value of these literary works “must cease to be taken for granted and must instead become newly salient in the context of their startling erotic congruence,” (pp 184).

In the past, and even still today, the literary canon was not allowed to show homosexuality present in many of the writers. Socrates, along with many of his contemporaries, practiced homosexual relationships; this was considered normal for Greece at the time, but many arguments will claim that this normality nullifies its value in understanding it. “Passionate language of same sex attraction was extremely common during whatever period is under discussion—and therefore must have been completely meaningless,” (pp 186). This argument, however, is not extraordinarily strong. There are many things which are commonplace to the era which espouses them yet are not given any special recognition in the languages of those people.

For instance, Roman concrete was lost to modern science for centuries, because the recipe called for “water” to be used in mixing it. However, the water they were referring to was salt water (Irving, Michael, 2017). There was not the need to specify the difference, because why would someone use water that was not salt water? This does not trivialize the necessity of using salt water in the mixing process for Roman concrete. Yet because the distinction was not made, future people could not determine how to replicate it for centuries because they missed the hidden cue. This is like the cues of homosexuality in the literary canon, as Sedgwick points out.

The questions of “Has there ever been a gay Shakespeare… Proust?” (pp 186) could have clear answers when the canon is reviewed. That answer could very well be, “Not only have there been a gay… Shakespeare, and Proust but that their names were… Shakespeare, Proust.” Whether or not these individuals held relationships with members of the opposite sex does not remove the existence of homo erotic themes in their work, which provide if not a basis for their own homosexuality, one for an acceptance of the lifestyle and understanding that it had value even in their own time. The pressure to view all literature as that of the homophobic canon denies the humanity of those with same sex attraction and limits our own access to the robust and colorful culture around us. Denying these roots becomes a form of censorship.

“The most openly repressive projects of censorship, such as William Bennett’s literally murderous opposition to serious AIDS education in schools on the grounds that it would communicate a tolerance for the lives of homosexuals, are, through this mobilization of the powerful mechanism of the open secret, made perfectly congruent with the sooth, dismissive knowingness of the urbane and the pseudo-urbane,” (pp 187).

The current cultural norms are shifting. However, not even long-ago heterosexuality was doggedly supported as the only mode of normal human sexuality, with all other forms being viewed as toxic, deviant, even dangerous. The shifting mindset toward understanding brings greater enlightenment to everyone and shows that the canon as it is recognized can be more diverse than cis elitism in academia tends to allow. Homosexuality in literature is not only normal but has been for centuries; we’ve only forgotten in the face of cis dominance in existing media.

Works Cited

Irving, Michael. “Just add seawater: Ancient Roman concrete gets stronger over time.” Newsatlas.com. 2017. https://newatlas.com/roman-concrete-stronger-seawater/50343/

Sedgwick, Eve. “Epistemology of the Closet.” Taken from a Falling in Theory. 1996. Pp 186-189. Bedford/St. Martin’s Publishing.

Putting the LGBTQ in the Literary Cannon

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick wrote extensively on the place of homosexuality in the literary canon, especially in the authors thereof. The evidence of this lifestyle is apparent in some cases quite clearly, in others more obscured, but in most cases, hidden from the public view due to prevailing sentiment that homosexual lifestyles were wrong by the majority rule of white, cis male, heterosexual literary elites.

Two novels referred to by Sedgwick, Dorian Gray and Billy Budd, provide “a durable and potent centerpiece of gay male intersexuality and indeed [have] provided a durable and potent physical icon for gay male desire,” (Sedgwick, Eve, pp 183). The stories follow people living in lifestyles of homosexual desire, and the struggles which erupted from the societies around them as a result. Recognizing the value of these literary works “must cease to be taken for granted and must instead become newly salient in the context of their startling erotic congruence,” (pp 184).

In the past, and even still today, the literary canon was not allowed to show homosexuality present in many of the writers. Socrates, along with many of his contemporaries, practiced homosexual relationships; this was considered normal for Greece at the time, but many arguments will claim that this normality nullifies its value in understanding it. “Passionate language of same sex attraction was extremely common during whatever period is under discussion—and therefore must have been completely meaningless,” (pp 186). This argument, however, is not extraordinarily strong. There are many things which are commonplace to the era which espouses them yet are not given any special recognition in the languages of those people.

For instance, Roman concrete was lost to modern science for centuries, because the recipe called for “water” to be used in mixing it. However, the water they were referring to was salt water (Irving, Michael, 2017). There was not the need to specify the difference, because why would someone use water that was not salt water? This does not trivialize the necessity of using salt water in the mixing process for Roman concrete. Yet because the distinction was not made, future people could not determine how to replicate it for centuries because they missed the hidden cue. This is like the cues of homosexuality in the literary canon, as Sedgwick points out.

The questions of “Has there ever been a gay Shakespeare… Proust?” (pp 186) could have clear answers when the canon is reviewed. That answer could very well be, “Not only have there been a gay… Shakespeare, and Proust but that their names were… Shakespeare, Proust.” Whether or not these individuals held relationships with members of the opposite sex does not remove the existence of homo erotic themes in their work, which provide if not a basis for their own homosexuality, one for an acceptance of the lifestyle and understanding that it had value even in their own time. The pressure to view all literature as that of the homophobic canon denies the humanity of those with same sex attraction and limits our own access to the robust and colorful culture around us. Denying these roots becomes a form of censorship.

“The most openly repressive projects of censorship, such as William Bennett’s literally murderous opposition to serious AIDS education in schools on the grounds that it would communicate a tolerance for the lives of homosexuals, are, through this mobilization of the powerful mechanism of the open secret, made perfectly congruent with the sooth, dismissive knowingness of the urbane and the pseudo-urbane,” (pp 187).

The current cultural norms are shifting. However, not even long-ago heterosexuality was doggedly supported as the only mode of normal human sexuality, with all other forms being viewed as toxic, deviant, even dangerous. The shifting mindset toward understanding brings greater enlightenment to everyone and shows that the canon as it is recognized can be more diverse than cis elitism in academia tends to allow. Homosexuality in literature is not only normal but has been for centuries; we’ve only forgotten in the face of cis dominance in existing media.

Works Cited

Irving, Michael. “Just add seawater: Ancient Roman concrete gets stronger over time.” Newsatlas.com. 2017. https://newatlas.com/roman-concrete-stronger-seawater/50343/

Sedgwick, Eve. “Epistemology of the Closet.” Taken from a Falling in Theory. 1996. Pp 186-189. Bedford/St. Martin’s Publishing.