Henrik Kniberg's Blog, page 7

November 4, 2013

How we make decisions

We are over 30 people at Crisp now, and we are a decentralized organized with no managers. So how do decisions get made? This article is a direct translation of our internal wiki page “Hur vi tar beslut på Crisp” (how we make decisions at Crisp).

So how did we decide on this decision-making process? Well, we didn’t. I just noticed that people sometimes ask “so how do we make decision” and I started thinking about how it appeared to work, and wrote a wiki page describing it. Then I had a followup meeting to check if this is how we really work, and if this is how we want to continue working, and the answer was pretty yes on both counts.

Note – for allocation of consultants to client engagements we have a specific protocol for that – the bun protocol. Similar for recruitment decisions.

Why don’t we have a well defined decision-making process?

We make lots of decisions all the time. Which type of coffee machine to buy? Should our internal fees be raised? Where & when is our next Crisp conference? Which partners should we invite?

Different types of decisions need a different process. It would be crazy to involve the whole team in decisions like which type of whiteboard pens to buy. And it would be crazy to NOT involve the whole team in questions related to organizational structure, or the team membership fee [at Crisp, consultants aren't employed - they each have their own company and pay a membership to be part of Crisp].

So it’s not a good idea to have one single well-defined decision process for everything. And it’s not a good idea to try to list all potential decision types and create a well-defined process for each type, the list would be too long and complex, and there would be too many gray zones.

Well, how do we make decisions then?

You don’t need a well-defined decision process in order to make decisions. If that was the case, the world would stand still

Instead, we follow these principles/guidelines:

The person driving an issue owns the decision process

A decision is only a decision if there is a “puller” who makes sure it happens. [we use the term "driver" and "puller" interchangably]

Decisions should be documented in our decision log [a simple spreadsheet showing date, what the decision was, who is affected, and who was involved].

Some decisions lead to financed “projects”, like a new website [the people involved in that form a "crisplet"]. To get finansing, there needs to be two “pullers” throughout the whole project. [in practice, this model is rarely used]

Example: If the board is considering to raise the team fee, the board drives that question, and therefore gets to pick the decision process.

Example: If I want Crisp to collaborate with company X, then I’m the one driving that question and I pick the decision process.

When a decision is made and it affects more than just yourself, send an email to the team mailing list.

How do I pick a decisions process?

Here are some exampels of different decisions processes on a scale from “fast” to “well-anchored”.

Own decision. Decide yourself without talking to anyone.

Own decision with team input. Ask for input from the team, but then make the decision yourself.

Own decision with team-anchoring. Ask for input from the team, suggest a decision, check if the team is OK with it before closing the decision.

Team decision. Facilitate a decision from the whole team (normally through concensus, with majority vote as fallback if we can’t reach consensus).

The term “team” in this case really means “those who are affected by the decision”. Sometimes the whole team, sometimes just a few individuals.

These decisions processes can be combined. For example, start by getting input from the whole team, then suggest a decision and anchor with those people who are most directly affected.

Some things to consider when choosing a decisions process:

Who is affected? Only you? You and a few others? The whole team?

How important is this question for you? How important is it for those who are affected? Is it a critical decision or trivial one?

Is the decision reversable [most decisions are]? What is the consequence of making the “wrong” decision, and who is affected by that?

How easy or hard is the decision? How easy is it to reach consensus with all people affected?

How urgent is the decision? What is the consequence of delaying the decision, or not making a decision at all?

Who are you? The decision process may vary depending on your perspective – consultant, board member, office admin, etc. May also depend on how long you’ve been at Crisp (if you are new and unsure you might need to seek more anchoring from people).

Sample decisions:

“Should I arrange a free seminar with Lyssa Adkins” => Own decision. Just do it.

“Which color should we have on the Crisp cup?” => Own decision with team input.

“How often should we do Crisp conferences?” => Own decision with team anchoring.

“Should we divided the company into two business units?” => Team decision.

At the end of the day it’s about balancing risk. If you make the decision yourself it will be fast, but you risk problems if others don’t like it. If you seek 100% consensus you may get a better decision with better support, but it could take time – especially for questions where people have opposing opinions.

There is no perfect process so seek a balance btween these extremes! We most often end up in the middle of the scale – “own decision with team inpu” or “own decision with team anchoring” (where “team” isn’t necessarily the whole team)

What do I do if I still feel unsure of which decisions process to use?

Take a chance! “Better to ask for forgiveness than permission”. Most decisions are reversible, so you don’t really need to be afraid of making the “wrong” decision or using the “wrong” decision process. Just accept feedback and learn

Talk to a Crisp colleague, for example someone who has been around longer and can give examples of what we’ve done in the past.

Check if someone else can drive the question for you (or with you). Preferably someone who is strongly engaged in the question. For example if I want next Crisp conference to be in the Maldives I’d involve Jennie in the decision process, since she usually arranges our conferences. It’s nice to pair-drive a decision, so you can always ask on the team mailing list to find a co-driver.

Escalate the decision to the board of directors. For example “hey board, I want to change our recruiting process, how would we make a decision like that?”.

Conferences and Pulse meetings [mini-conferences] are a great place to discuss a decision process – and in many cases make the actual decision as well, since everyone is there

October 25, 2013

Acceptance-Test Driven Development from the Trenches

Getting started with ATDD

Have you ever been in this situation?

Then this article is for you – a concrete example of how to get started with acceptance-test driven development on an existing code base. Read on.

October 19, 2013

How I write (and why)

The purpose of this article is…

Actually, there is no purpose. There never is. I just write because I feel like it. Then I read the article and make up a purpose afterwards, and start eliminating anything in the article that doesn’t fit that purpose. But I won’t do that this time. Read on and you’ll understand why. By the way, this text is blue because it’s my second iteration. Black text is the original, first iteration. Here it is:

Let me tell you about my creative process. Every writer has a creative process. Otherwise they wouldn’t get anything written; well, at least not anything creative

It feels wierd to be writing about my creative process while I’m in the process of creating. Very meta. Anyway.

I write a lot. Like all the time. Well, strictly speaking it’s not writing. It’s dialogs going on in my head. Otherwise known as “thinking”. I think about stuff a lot. Probably too much. I probably come across as absent minded. Like sometimes I’m brushing my teeth, and I start thinking about something. Like why I write so much. That happened just now, I was brushing my teeth and I noticed I was having a dialog in my head (well, more a monologue) about how I write. Why? I don’t know, it just happens. Maybe because a large part of my job is to help companies improve, and often that involves analyzing things and explaining things. Anyway, so I’m brushing my teeth physically while I’m mentally somewhere very far away, having a monologue about how I write. Like the opposite of mindfulness. Mindlessness. Needless to say, my teeth are exceedingly clean tonight

So this happens quite often, these long monologues in my head (don’t worry, it’s not creepy voices telling me to do evil things. it’s just a monologue of me trying to explain some kind of concept or idea, over and over again, in different ways, until i find a really short and clear way). Especially when I do the dishes, take a shower, or do something else that occupies me physically but leaves my mind free to wander (as opposed to when I’m at a computer and letting my mind be occupied by whatever is on the screen, and thereby hindering any attempt at actual thinking).

Sometimes the monologes fade out and I can go back to whatever I was doing. Sometimes I get surprised, like when I’m doing the dishes and my mind wanders and by the time my mind has finished wandering I notice that the whole kitchen is in perfect shape. Kind of like a time warp, very interesting. Sometimes when I improvize on the piano my mind wanders as well. I really wonder what kind of music comes out when I do that, I don’t hear it because I’m thinking about something else. Should try recording it sometime. Could make a record called “Henrik’s mindless music”. A nice reaction against the whole mindfulness hype

Then, sometimes, the thinking reaches a tipping point. Like the ideas crystalize into something truly interesting and useful, and really want to come out into the world. Like a baby that’s tired of being in mommy’s tummy and really badly wants to come out and see the world. Often this happens in the middle of the night. I wake up at 3 am or so and lie still, thinking about something, having the dialog, and sometimes even whispering quietly to myself (one of my kids asked me that the other day, she heard me whispering to myself in the bathroom. Must have thought I was possessed or something). Often I don’t notice that I’m awake thinking about something, until maybe a half hour later when I’m like “what the heck, I need to sleep!”. Anyway so I wake up at 3 am, thinking about something, and then can’t sleep because the monologue continues. And, because it’s an interesting monologue, I want to hear the rest of it. Then by 5 am the article/idea/thingo reaches critical mass and my head is exploding. I need to get it out! Besides, I can’t sleep anyway. Might as well do something.

So I get out of bed and run down to my desk. Literally, run down to the desk. Sometimes I stop by the kitchen on the way to make some tea and a sandwhich, which sometimes takes a long time because my mind is wandering while I do it (“er, why did I put the butter back in the fridge, I haven’t put any butter on the sandwich yet!”). Anyway then I hurry over to the desk, head exploding, start up notepad or ms word or whatever and just start typing. Like what I’m doing right now. Just typing and typing, no editing, no going back, no thinking. Just emptying out the article that is pretty much all done in my head. You’d be amazed at how fast I can write an article. Once I even wrote a whole book in 3 days. My first book (OK, a short book… but definitely a book!). I didn’t even know I was writing a book until it was done, and I took a step back and was like “er…. this is like actually a book!”. OK I did add a couple of chapters a couple of days later, and some editing of the original text, but that’s about it. It even became a bestseller, no one was more surprised than me! Lots of people tell me that the book is so easy to read, that you basically can’t stop reading until you’re done. Probably because that’s exactly how it was written – all in one sitting (well, I paused to sleep for a few hours a couple of times).

Sometimes the text leads nowhere, or diverges into vacuum. Then I just drop it. Head has been emptied, feels great, I go back to sleep. I have lots of unfinished texts lying around, I usually never read them again. They are quite crappy I believe.

Sometimes, however, I end up with a really nice article that actually has a clear theme, clear takeaway points, clear structure, everything. All done on the first pass. In a sense you might say I’m not very fast at writing at all. Because once a topic has reached “critical mass” in my head, I’ve usually been thinking about it on a fairly regular basis over a period of several months, or even a year. It’s like there’s this background process going on in my head, a little writer inside that is continously working on various different articles, sometimes even working in my sleep (maybe that’s his most productive period, while the head isn’t occupied with lots of other thoughts).

It’s critically important to not be disturbed during this writing frenzy. My family knows that. I have four small kids, age 3-10. If it’s the middle of the night it’s not a problem, they’re all asleep. However if it’s daytime and they are around I tell them “now I need flow” and I go into my home studio and close the door. They know this means that they really shouldn’t disturb (they even created some really nice “don’t disturb, daddy is in flow” signs for my studio door). I’m in a state of hyperflow and even the tiniest disturbance, even a *risk* of disturbance, will ruin it. That article that I can write in 2 hours in hyperflow would take weeks to write if I didn’t have the hyperflow, and it wouldn’t be as good. So we all have come to respect that magic.

Once I get to the end of the article (if it doesn’t fizzle out on the way), well, it feels great! I’m usually quite exhausted by then, so I just save the doc and go back to sleep or go back to whatever I was doing. Nice blissful feeling, the voice in my head is finally quiet, I can be more present and enjoy the moment, be more authentically social rather than absentmindedly social. I know the article needs some more work, but the critical period is over, I caught the magic and it’s written down.

Creative flow is like a train that departs at a certain time. When my idea reaches “escape velocity” in my head, I either catch the train or not. If I catch the moment and go write, I get a great article (well, usually) in amazingly short time. If I don’t catch the train, it’s usually gone forever (until I come up with a new topic next time). Sometimes when I can’t (or don’t want to) catch the flow right now, I add a line to my “stuff to write about” doc on my iphone. That list is veeeeery long by now, and I almost never read it. I just add stuff to it. I like to believe it’s a list of inspirational stuff, some of which I might write about in the future. In practice, though, I suspect it’s really just a list of missed trains. Miscarriages. But that doesn’t really bother me, there’s always new trains. And it feels good adding stuff to that list for some reason, a sense of closure.

I’ve come to respect this creative flow, so I make sure there is at least potentially time to catch it. I usually reserve 2 days of “slack” in my calender every week. I aim for 2, although sometimes it’s only 1. I literally write the word “slack” on 1-2 days every week in my calendar. Slack means I don’t have anything scheduled. I might have lots of stuff to do, but nothing specifically scheduled that day. Normally I’ll spend the day doing email, boring admin, preparing for future engagements, catching up on stuff, or whatever.

But if creative flow happens to come on one of those days, I have time to catch it and run with it!

Anyway, so I’ve just speed-wrote an article (and now I’m rereading it the morning after and doing minor edits, that’s the blue text). What’s missing is a title, an intro, and some kind of final take-away points. I leave that for later. Typically later the same day, or maybe a day later. Not later than that. I go back, read the whole thing, and start thinking about what this really is. Is this a useful article? What should the title be? So I start brainstorming titles, usually I write a number of different titles and let them sit there for a while until I (maybe a day later) discover what it should be called.

I also think about what purpose this article could serve for it’s readers. I start most articles with a problem statement, and then a “the purpose of this article is XXX”, and then some kind of disclaimer. If I can’t think of a clear purpose for the article I don’t publish it. So it’s not like I first think up a purpose, and then write an article to fulfill the purpose – it’s the other way around. I write an article and then figure out what purpose it might fufill.

So I’ve added some kind of weird intro now, basically admitting that the article doesn’t really have a purpose. Haven’t done a title yet. Well, the doc is called “my creative process.rtf” so I might call it that. On the other hand this is specifically about how I write, not how I do other stuff like create a presentation or record a song. Hmmm. We’ll see.

Then I think about the takeaway points, and add that at the end. Usually I can come up with some clear takeaway points, but if I can’t that’s OK.

Now the shape of the article is pretty clear! Now I go back and start fiddling with the text, and start adding pictures. I love pictures, I’m very much a visual thinker. Often I draw small sketches on my drawing tablet as I write the article, and paste them directly into the text as part of the writing or editing process. This article probably won’t have any pictures. That’s very unusual. During the editing process I’m very minimalistic, always looking for sentences and words that can be removed, or replaced with a simple picture. I very much apply the principle “perfection is achieved not when you have nothing left to add, but when you have nothing left to remove”. The after-the-fact purpose statement helps me figure out what to remove – basically anything that doesn’t fit the purpose. So the final article is often shorter than the original draft. This article is an exception, since I haven’t stated any specific purpose and because I want to show you my creative process, uncensored. So if this article seems talky and confusing, that’s intentional

Fiddle, fiddle, fiddle, move a sentence higher up or lower down, remove a word or two, erase a paragraph because it repeats a point that was stated earlier, add a concrete anecdote or examples, etc. This process is creative but not nearly as flow-critical as when I wrote the first draft. So I don’t need hyperflow, it’s OK to have minor disturbances like kids running in to talk with me. Although this time around I’m hardly removing anything, for the reasons stated above.

Now the article is pretty much done. I ask my wife to come look at it. She’s good at pointing out things to improve. So I fiddle some more based on that input. OK, I’m at a conference, 8 am, in bed typing, wife not around. But Crisp colleagues are around. Let’s see if i can get any of them to read through this article today. When I’ve written an article I want feedback immediately. HATE waiting. I want to get the thing done, published, or whatever, so I can move on with life. I should probably get up now or I’ll miss breakfast.

Now, after all this, I ask myself: “so, what will I do with this article?” Sometimes I put it directly on my blog (that’s probably what I’ll do this time), sometimes I turn it into a PDF and put it on the blog. Sometimes I offer it to other sites like InfoQ or PragProg.com. Sometime a long article ends up being a book. It all depends a lot on where and how I want the ideas to spread.

Once the article is up, I mention it on twitter, facebook, linkedin, and (when I remember) Google+. I want people to read it! Once I see it spread, I feel a great sense of closure. Absolutely wonderful.

A shrink might have all kinds of not-too-flattering explanations and psychobabble about why I get this great sense of relief and closure once my article spreads. I don’t know, but it just feels good. I love spreading ideas. Some ideas get bounced around for a while and then quietly ignored by the community. Others go viral and spread all over the place, some even cause entire companies to change the way they work. Often I get really useful feedback and learn even more about the topic. And I get emails every day from people thanking me for my articles, sometimes things I wrote years ago, telling me about the impact it has made in their lives, feels great!

The most influential things I’ve created so far are “Scrum and XP from the Trenches“, “Agile Product Ownership in a Nutshell“, and “Scaling agile at Spotify“. (Agile Product Ownership a Nutshell is actually a video, but the creative process was similar). The impact of these article/videos have been absolutely amazing. And the total amount of work invested in the actual production of them is about, say, 2 weeks in total for all three. That’s the power of hyperflow.

So, this urge to write… I don’t think it’s about power or influence or ego. I think it’s just this basic human need of feeling useful. I feel like I’ve helped people, made the world into a slightly better place. But then, even if my article made little or no impression on the world, I feel very good just having released it. Because then I’ve freed up that part of my mind, quieted that monologue. And thereby I can move on, leaving space for whatever article is going to pop into my head in the future.

So basically, articles write themselves in my head all the time. Unstoppable. Most of them never get out. Sometimes, however, the stars align and I have the opportunity and time to actually sit down and write it down. Maybe once per month or so. I try to make space for that using my slack days, and when things match up, I often end up with a really nice article to share with the world.

So that’s it. Writing is my blessing and curse. It’s a blessing because it makes me feel good and generates very interesting and well-paid work, and because creative flow is such a pleasure to be in. It’s a curse because I can’t stop the voice in my head, it’s always thinking and analyzing and talking about stuff. Sometimes I can make it shut up by doing something very presence-demanding, like playing with kids or cooking a new type of meal, jamming with a band, or having a conversation with someone. But mostly it just keeps on rambling until I sit down and actually write the darned article.

There. That’s it. I just finished the brain dump. Feels great. I’m not done, still need to do some editing. (mostly done with that now I think, gonna leave the text pretty raw) But the critical part is over, I’ve captured the essence of the monologue that was in my head. Now it won’t be lost.

I’m in bed, at a hotel. I was planning to read a book, but I ended up writing this article instead. Tomorrow or the day after I’ll go back and polish up the text, figure out a title, and maybe fiddle with the ending. Then I’ll probably put it up on my blog. We’ll see. Goodnight!

Breakfast time. Good morning!

(laughing out loud at what a crazy meta-article this is…)

/Henrik

October 11, 2013

Good and Bad Technical Debt (and how TDD helps)

Technical Debt is usually referred to as something Bad. One of my other articles The Solution to Technical Debt certainly implies that, and most other articles and books on the topic are all about how to get rid of technical debt.

But is debt always bad? When can debt be good? How can we use technical debt as tool, and distinguish between Good and Bad debt?

Exercise: Draw your technical debt curve

Think of technical debt as anything about your code that slows you down over the long term. Hard-to-read code, lack of test automation, duplication, tangled dependencies, etc.

Now think of any system you’re working on. Grab a piece of paper and draw a technical debt graph over time. It’s hard to numerically measure technical debt, but you can think of it in relative terms – how is the relative amount of technical debt changing over time? Going up? Down? Stable?

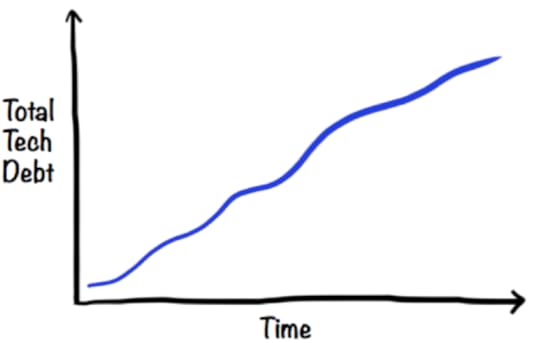

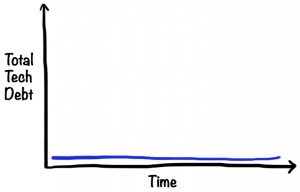

Sadly, in most systems tech debt seems to continuously increase.

How do you WANT your debt curve to look?

Next question: if you could choose, in a perfect world, how would you like that curve to look like instead? Might sound like an obvious question, your spontaneous thought may be something “Zero tech debt! Yaay!”

Because, heck, didn’t I just say that technical debt is anything that slows you down? And who wants to be slowed down? If we could have zero technical debt throughout the whole product lifecycle, wouldn’t that be the best?

Actually, no. Having zero technical debt at all times will probably slow you down too. Remember, I said “Think of technical debt as anything about your code that slows you down over the long term”. The short term, however, is a different story.

Let’s talk about Good technical debt.

When is a mess Good?

Think of your computer and desk when you are in the middle of creating something. You probably have stuff all over the place, old coffee cups, pens and notes, and your computer has dozens of windows open. It’s a mess isn’t it?

Same thing with any creative situation – while cooking, you have ingredients and spices and utensils lying around. While recording music, you have instruments and cables and notes lying around. While painting, you have pens and paints and tools lying around.

Imagine if you had to keep your workspace clean all the time – every time you slice a vegetable, you have to clean and replace the knife. After each painting stroke, you have to clean and replace the brush. After each music take, you have to unplug the instrument and put it back in it’s case. This would slow you down and totally kill your creativity, flow, and productivity.

In fact, the “mess” is what allows you to maintain your state of flow – you have all your work materials right at your fingertips.

When is a mess Bad?

A fresh mess is not a problem. It’s the old mess that bites you.

If you open your computer to start on something new, and find that you still have dozens of windows and documents open from the thing you were working on yesterday, that will slow you down. Just like if you go to the kitchen to make dinner and find that the kitchen is clogged up with old dishes and leftovers from yesterday.

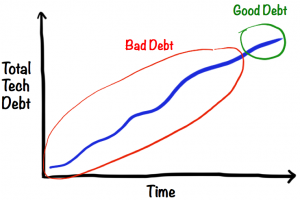

Same with technical debt. Generally speaking, old debt is bad and new debt is good.

If you are coding up a new feature, there are lots of different ways to do it. Somewhere there is probably a very simple elegant solution, but it’s really hard to figure it out upfront. It’s easier to experiment, play around, try some different approaches to the problem and see how they work.

Any technical debt accumulated during that process is “good debt”, since cleaning it up would restrict your creativity. In fact, somewhere inside the messy commented-out code from this morning you may discover the embryo to a really elegant solution to your problem, and if you had cleaned it up you would have lost it.

Another thing. Sometimes early user feedback is higher priority than technical quality. You’re worried that people might not want this feature at all, so you want to knock out a quick prototype to see if people get excited about it. If the feature turns out to be a keeper, you go back and clean up the code before moving on to the next feature.

The problem is, just like in the kitchen, we often forget to clean up before moving on. And that’s how technical debt goes bad. All that “temporary” experimental code, duplicated code, lack of test coverage – all that stuff will really slow you down later when you build the next feature.

So regardless of your reason for accumulating short-term debt, make sure you actually do pay it off quickly!

But wait. How short is “short term”?

When does Good Debt turn into Bad Debt

My experience is that, in software, the “good mess” is only good up to a few days, definitely less than a week. Then it starts going stale, dirty dishes clog up the kitchen, the leftovers start to stink, and both inspiration and productivity go downhill.

So it’s really important to break big features into smaller sub-features that can be completed in a few days. If you need practice doing that I can highly recommend the elephant carpaccio exercise.

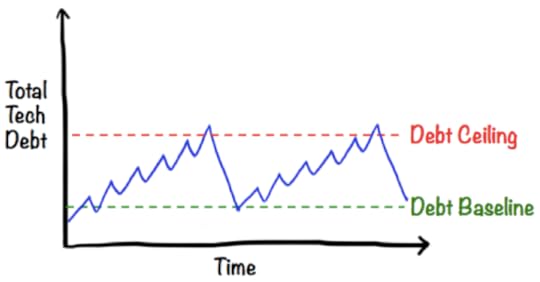

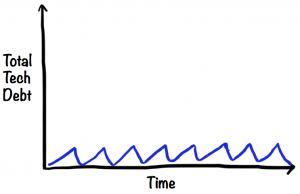

The ideal technical debt curve

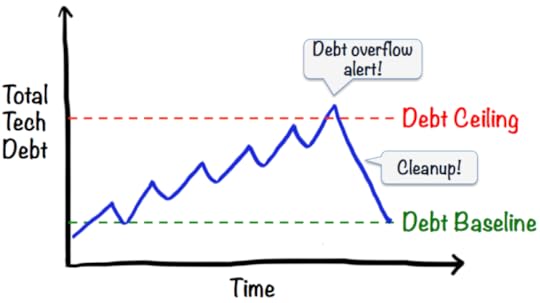

If new debt is good, and old debt is bad, then the ideal curve should look something like this, a sawtooth pattern where each cycle is just a day or two.

That is, I allow myself to make a temporary mess while implementing a new feature, but then make sure to clean it up before starting the next feature. Sounds sensible enough right?

Just like the kitchen; It’s OK to cause a creative mess while cooking, but clean it up right after the meal. That way you make space for the next creative mess.

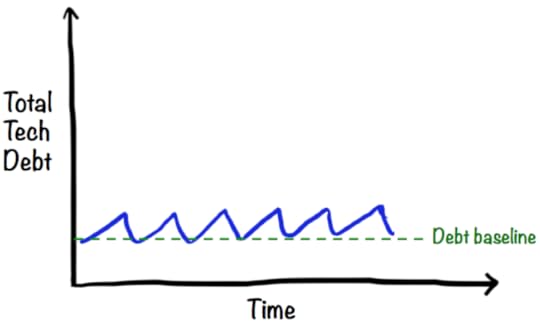

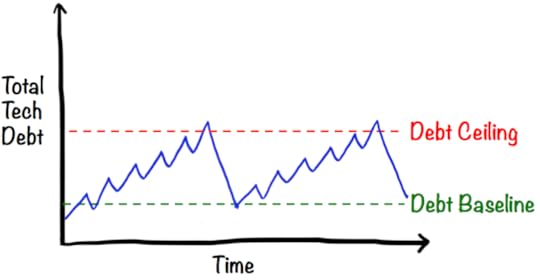

The more realistic ideal technical debt curve

In theory, it would be great to get down to zero technical debt after each feature. In practice, there’s an 80/20 rule involved. It takes a reasonable amount of effort to keep the technical debt at a low level, but it takes an unreasonably high amount of effort to remove every last last crumb of technical debt.

So a more realistic ideal curve looks like this, with a baseline somewhere above zero (but not too far!).

That means our code is never perfect, but it’s always in good shape.

The “debt” metaphor works nicely because, just like in real life, most people do have some kind of financial debt (like a house mortgage) on a more or less permanent basis. It’s not all bad. As long as we can afford to pay the interest, and as long as the debt doesn’t grow out of control.

Have a debt ceiling. Just for in case.

Now, even if we do clean up after every feature, we are humans and are likely to accidentally leave small pieces of garbage here and there, and it will gradually accumulate over time. Like this:

So it best to introduce a “debt ceiling”. Just like certain governments….

When debt hits the ceiling, we declare “debt alert!”, the doors are closed, all new development stops, and everybody focuses on cleaning up the code until they’re all the way back down to the baseline.

The debt ceiling should be set high enough that we don’t hit it all the time, and low enough that we aren’t irrecoverably screwed by the time we hit it. Maybe something like this over a half-year period:

How to set the baseline and ceiling

All this begs the questions “yes, but How?”. It may seem hard to quantify technical debt. But actually, it’s not. Anything can be measured, as long as it doesn’t have to be exact.

Just ask people on the team “How do we feel about the quality of our code?”. Pick any scale. I often use 1-5, where 5 is “beautiful, awesome code with zero technical debt”, and 1 is “a debt-riddled pile of crap”. With that scale, I would set the debt baseline to 4, and the debt ceiling to 3 (think of debt as the inverse of quality). That means quality will usually be 4, but if it hits 3 we will stop and yank it back up to 5.

Of all the possible metrics that can be used, I find that teams often like this subjective quality metric. It’s simple, and it visualizes something that most developers care deeply about – the quality of their code.

Other more objective metrics (such as test coverage, duplication, etc) can be used as input to the discussion. But at the end of the day, the developer’s subjective opinion is what counts.

Use debt ceiling to avoid a vicious cycle

The debt ceiling is very important! Because once your debt reaches a certain tipping point, the problem tends to spiral out of control, and most teams never manage to get it back down again. That applies to monetary debt as well. And governments…

One reason for this “tipping point” effect is the “broken window syndrome”. Developers tend to unconsciously adapt the quality of new code to the quality of the existing code. If the existing code is bad enough (many “broken windows”), new code tends to be just as bad or even worse – “oh that code is such a mess, I don’t know how to integrate with it so I’ll just add my new stuff here on top”.

Think of a kitchen, at home or at the office. If it’s clean, people are less likely to leave a dirty cup on the counter. If there are dirty cups everywhere, people are very much more likely to just add their own dirty cup on top. We are herd animals after all.

Make quality a conscious decision

My experience is that a quality level of 4 (out of 5) is a good-enough level of quality; clean enough to let the team move fast without stumbling over garbage, but not so overly clean that the team spends most of it’s time keeping it clean and arguing over code perfection details.

The key is to take a stand on quality. Regardless of how you measure quality, or where you place your debt baseline and ceiling, it’s very valuable to discuss this on a regular basis and make an explicit decision about where you want to be.

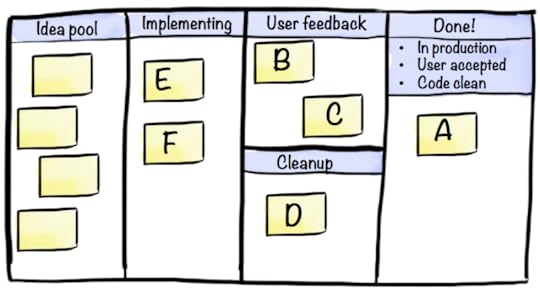

How Definition of Done helps

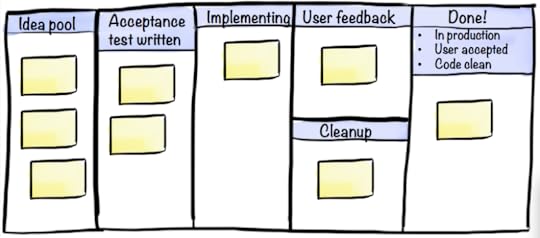

“Definition of Done” is a useful concept for keeping tabs on technical debt. For example, your Definition of Done for a feature could be:

Code clean

In production

User accepted

These are in no particular sequence, as that will vary from feature to feature. Every sequence has it’s advantages and disadvantages. Sometimes we’ll want to put something in production first, then get user feedback, then clean up. Sometimes we’ll want to clean up first, then get user feedback, then put in production. But the feature isn’t Done until all three things have been done.

Here’s a sample board to visualize features flowing through this process.

Feature A: All done. It’s in production, the code is clean, and the user has given thumbs up.

Feature B & C: Current focus is getting user feedback. B has already been cleaned, C has not.

Feature D: Current focus is cleaning up the code. User has tried it and given thumbs up.

Feature E & F: Currently being developed, trying to quickly get to a point where we can get user feedback.

The rest of the features are in the idea pool (most teams call that a “backlog” but I prefer the term “idea pool”).

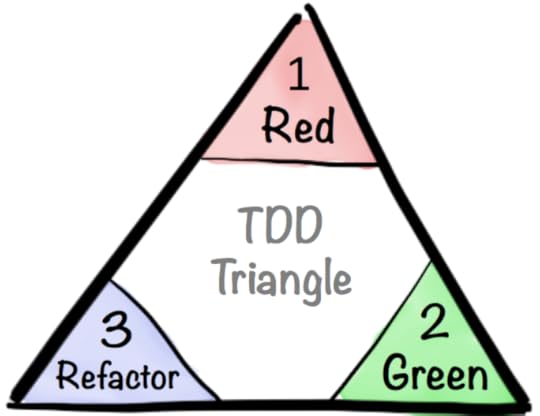

How TDD helps

Acceptance Test-driven development is a really effective way to keep the code clean while still enabling experimentation and creativity.

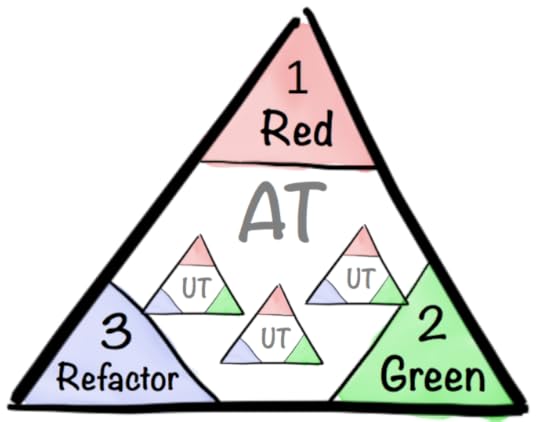

All features are developed in three distinct steps:

First step is to write a failing (“red”) acceptance test. When doing that, we focus exclusively on the question “what does this feature aim to achieve, and how will I know when it works?”. We’re setting a very clear goal and embedding it in code, so at this point we don’t care about quality, or how the feature will be implemented.

Second step is to implement the actual feature. We know when we’re done because the executable acceptance test will go from red to green. We’re looking for the fastest path to the goal, not necessarily the best path. So it’s perfectly fine to write ugly hacks and make a creative mess at this point – ignore quality and just get to green as quickly as possible.

Third step is to clean up. Now we have a working feature and a green test to prove it. We can now clean up the code, and even drastically redesign it, because the running tests (not just the newest test) act as a safety harness to alert us if we’ve broken or changed anything.

This process ensures that we don’t forget the purpose of the feature (since it forces us to write an executable acceptance test from the beginning), and that we don’t forget to clean up before moving on to the next feature.

To emphasize this process, we can update the board with “acceptance test written” column, just to make sure that we don’t start implementing a feature before we have a failing acceptance test.

The acceptance test doesn’t necessarily have to be expressed at a feature level (“if we do X, then Y should happen”). Some alternatives:

Lean Startup style acceptance test: “we have validated or invalidated that users are willing to pay for premium accounts”. Maybe rename the “User feedback” column to “Validating assumption”.

Impact Mapping style acceptance test “the feature is done when it increases user activation rate by 10%”. Maybe rename the “User feedback” column to “Validating impact”.

Either way, we just need to make sure cleanup is part of the process somewhere.

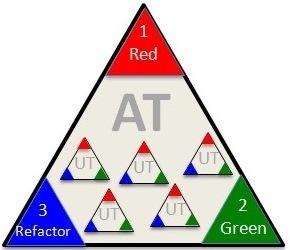

TDD can be done at multiple levels – at a feature level (acceptance tests) as well as at a class or module level (unit tests). Think of the unit tests as a bunch of triangles inside the acceptance test triangle. One loop around the big triangle involves a bunch of smaller loops inside.

After each unit test goes green, do minor cleanup around that. When the acceptance test goes green, do a bigger cleanup. Then move on to the next feature.

The key point is that each corner of the TDD triangle comes with a different mindset, and each one is important.

Good quality = happier people

At the end of the day, technical debt is not about technology. It’s about people.

A clean code base is not only faster to work with, it is more fun (or less annoying, if you prefer seeing things that way…). And motivated developers tend to create better products faster, which in turn makes both customers and developers happier. A nice positive cycle

September 23, 2013

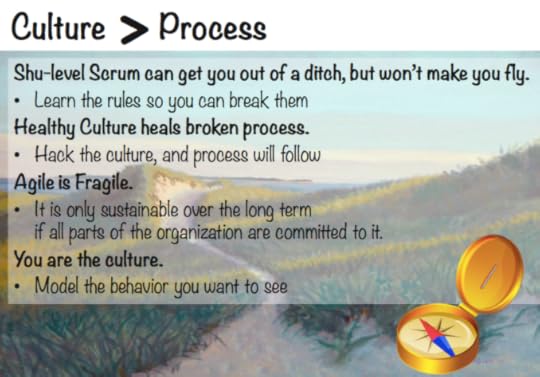

Culture > Process (Paris Scrum Gathering keynote)

Here are the slides for my keynote “Culture > Process” at the Paris Scrum Gathering. Amazing level of enthusiasm in the room, seems like this kind of stuff was exacty what people were looking for. Happy to see the ideas take such strong hold!

August 20, 2013

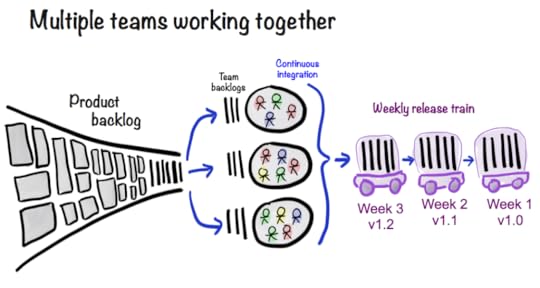

Agile event @ major swedish bank

Yesterday I spent a very inspiring day with a big swedish bank, doing agile intros with 1200 people. We had developers, designers, testers, C-level execs, project leads, pretty much every role represented. The CEO opened with words about why they are determined to go all-out agile, and we had a speaker from another even bigger company describe their ongoing agile journey and amazing results so far. Very interesting. And best of all – no roadmap or other fake attempts at pretending that we know what the journey is going to look like. It was clear that this is a bumpy ride and that change will have to evolve gradually from bottom as well as from top.

I can’t think of a better way to fuel an ongoing transitioning effort! I’m doing similar events with several other major banks, looks like the whole Swedish bank sector is jumping on to the agile train this year.

Anyway, here are the slides (and the original PPTX). This is actually a major revamp of all my previous material and it worked out really well! Thanks for all the great feedback. Some sample slides below.

July 25, 2013

Elephant Carpaccio facilitation guide

The Elephant Carpaccio exercise is a great way for software people to practice & learn how to break stories into really thin vertical slices. It also leads to interesting discussions about quality and tech practices.

The exercise was invented by Alistair Cockburn. We’ve co-facilitated it a bunch of times and encourage people to run it everywhere.

Here’s a pretty detailed (shu-level) guide showing how to run the exercise.

Elephant Carpaccio facilitation guide

July 11, 2013

The Solution to Technical Debt

Are you in a software development team, trying to be agile? Next time the team gets together, ask:

How do we feel about the quality of our code?

Everyone rates it on a scale of 1-5, where 5 means “It’s great, I’m proud of it!” and 1 means “Total crap”. Compare. If you see mostly 4s and 5s, and nothing under 3, then never mind the rest of this article.

If you see great variation, like some 5s and some 1s, then you need to explore this. Are the different ratings for different parts of the code? If so, why is the quality so different? Are the different ratings for the same code? If so, what do the different individuals actually mean by quality?

Most likely, however, you will see a bunch of 2s or worse, and very few 4s and 5s. The term for this is Technical Debt, although for the purpose of this article I’ll simply call it Crappy Code.

Congratulations, you have just revealed a serious problem! You have even quantified it. And it took you only a minute. Anyone can do this, you don’t have to be Agile Coach or Scrum Master. Go ahead, make it crystal clear – graph the results on a whiteboard, put it up on the wall. Visualizing a problem is a big step towards solving it!

Don’t worry, you aren’t alone, this is a very common problem. However, it’s also a very stupid, unnecessary problem so I’m baffled by why it is so common.

Now you need to ask yourselves some tough questions.

Do we want to have it this way?

If not, what do we want the code quality to be? Most developers want a quality level of 4 or 5. Yes, the scale is arbitrary and subjective but it’s still useful.

If opinions vary strongly then you need to have a discussion about what you mean by quality, and where you want to be as a team. You can use Kent Beck’s 4 rules of Simple Code as a reference point. It’s hard to fix the problem if you can’t agree on where you want to be as a team.

What is the cause of this problem?

This is just a rhetorical question, because the answer is clear.

“Things are the way they are because they got that way!” -Jerry Weinberg

Crap gets into the code because programmers put it in! Let me make that crystal clear: Crappy Code is created by programmers. The programmer uses the actual keyboard to punch the actual code into the actual computer. Irregardless of other circumstances, it is the actions of the programmer that determine the quality of the code

The first step in solving technical debt, is to admit and accept this fact.

“but wait, we inherited a bunch of crappy legacy code. We did NOT write it!”

OK, fair enough. The relevant question in that case is: “is code quality improving or getting worse?” Rate that on a 5 point scale (where 1 is “getting worse fast”, 5 is “getting better fast”). Then reapply this article based on that question instead.

Why are we producing crappy code?

The answer will vary. However, I’ve asked it many times and I see some very strong trends.

It’s probably not because you WANT to write crappy code. I’ve never met a developer who likes writing crappy code.

It’s probably not because you don’t know HOW to write clean(ish) code. The skills will vary, but it’s enough that you have a few people in the team with good skills in writing clean code, and a willingness from everyone else to learn. Combine that with a habit of code review or pair programming, and most teams are perfectly capable of writing code that they would rate a 4 or a 5, if they take the time they need.

It may be because of broken window syndrome. Crappy code invites more crappy code, because people tend to adapt their new code to the quality of what’s already there (“when in Rome…”). Once you realize this, you can decide to simply Stop It, and introduce code review or pair programming to police yourselves.

However, the most probable reason for why you are writing crappy code is: Pressure.

I often hear comments like “we don’t have time to write clean code” (that statement is at worst a lie, at best a lame excuse). The truth is, you have 24 hours per day just like everyone else, and it’s up to you what you do with it. Face it. You do have time to write clean code, but you decided not to. Now let’s keep examining this concept of Pressure.

Where does pressure come from?

You might want to do a cause-effect analysis of this. Is the product owner pressuring you? Why? Who is pressuring the product owner? Who is pressuring the person who is pressuring the product owner? Draw the chain of pressure.

Then ask yourself. Is this pressure real? Do these people really want us to write crappy code? Do they know the consequence of crappy code (I bet you can list many), and do they really think it is worth it? Probably not. Go ahead, get on your feet and go ask.

Often the cause of the pressure is the programmers themselves. Developing a feature almost always take longer than we think, and we really want to be a Good Programmer and make those stakeholders happy, so the pressure builds up from inside.

NOTE: sometimes there is business sense in writing crappy code. We may have a critically important short-term goal that we need to reach at all costs, or we may be building a throw-away prototype to quickly test the market. But that should be the exception, not the norm. If you clean up the mess you made as soon as the short-term goal is reached, or you actually throw away the throw-away prototype, then you won’t end up with a chronic case of Code Crapiness.

Shall we decide to stop this nonsense now?

This it the most important question.

If you are a programmer, the fact that you (as programmer) are responsible for the problem is actually Good News. Because that means you are perfectly capable of Solving the problem. And the solution is simple:

Stop Writing Crappy Code

(Just what the world needs – a new acronym: SWCC™)

“but but but but but…. we don’t have time… the PO bla bla bla, our release date bla bla”

No, spare me the excuses. Just Stop It.

Well OK, you might actually decide to continue writing crappy code. You might decide that this battle is not worth fighting. That’s your decision. If so, at least don’t call yourself an agile development team, and do challenge anyone else who thinks you are agile. One of the fundamental principles of Agile software development is Sustainable Pace. If you are creating Crappy Code, development is going to get slower and slower over time. There is no business sense in this, and it is certainly not agile.

But assuming that you do want to stop, let’s explore what happens.

As a team of programmers, you can take a stand: “We Will Stop Writing Crappy Code”! Write it up on the wall. Shake hands on it. Add “no added technical debt” to your Definition of Done.

Tell the world, and the people who you believe are pressuring you into writing code: “We have been writing crappy code. Sorry about that. We’ll stop now.” Trying saying it loud. Feels good!

Stop Writing Crappy Code

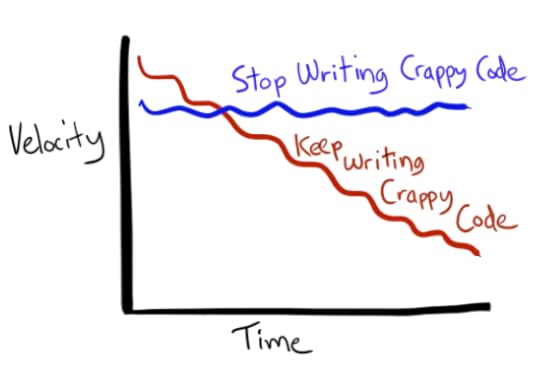

Look at these two curves.

Yes, this is a simplification, but the difference is real. If you Keep Writing Crappy Code, you get slower and slower over time (as you spend more and more of your time wrestling the code). If you Stop Writing Crappy Code, you get a more sustainable pace. But there is velocity cost – you will slow down in the short term.

As team, you decide how much work to pull in – that pull-scheduling principle is fundamental to both Agile and Lean. It’s built into the agile methods. For example, in Scrum Sprint Planning the team chooses how many backlog items to pull into a sprint, same in XP Planning Game. In Kanban, the team has a work-in-progress limit and only pulls in the next item when the current one is Done. Basically, the team has full power and responsibility over quality. Use the power!

In concrete terms: If you are doing Scrum, and you’ve been delivering about 8-10 features per sprint, try reducing that. Only pull in 6 stories next sprint, despite any perceived pressure. Ask yourself at each sprint retrospective. “What is the quality of the code that we produced this sprint (scale 1-5)”. If it is less than 4-5, then pull in fewer stories next sprint. Keep doing that until you find your sustainable pace.

This has business implications of course. The product owner (or whatever you call the person who makes business priorities) will have to prioritize harder. She’s used to seeing 8-10 stories come out of each sprint. Now she will only see 6-7, so she needs to decide which stories NOT to build.

Yes, this will lead to arguments and tough discussions. The real source of pressure (if there was any) will reveal itself. Quality is invisible in the short term, and that needs to be explained. Take the battle! Stand by your decision. If programmers don’t take responsibility for the quality of their code, who will?

Code quality is not Product quality

Code isn’t everything. There’s more people involved in product development than just programmers. There’s business analysts, testers, managers, sysadmins, designers, operations, HR, janitors, and more.

Everyone involved is collectively responsible for the quality of the product being built. That includes not only the code, graphical design, database structure, and static artifacts like that. It includes the whole user experience as well as the business result of the product.

Code quality is a subset of product quality. You can have great code, but still end up with a product that nobody wants to use because it solves the wrong problem.

What about vice versa – can you have a great product, but crappy code? I hate to admit it but, Yes, technically you can build a great product with crappy code. Somehow teams seem to get away with this sometimes. However, improving and maintaining the product is slow, costly, and painful, because the product is essentially rotten on the inside. It’s a lose-lose proposition and over time the best developers will leave.

What about the Old Crap (a.k.a Legacy Code)?

OK, so you’ve stopped writing crappy code. Congratulations! You’ve stopped accumulating technical debt. You’re still paying interest on your existing debt, but at least the debt has stopped growing.

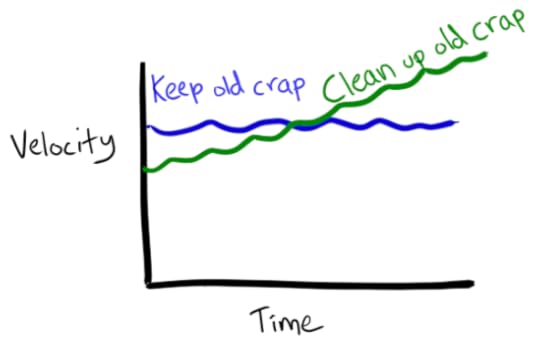

Next step is to decide – can you live with the existing technical debt, or do you want to do something about it? If you decide to reduce technical debt, the consequence is that you will slow down even further in the short term, but speed up over the long term. Like this:

Sometimes it’s worth it, sometimes not. The answer is not obvious, it’s a business decision, so make sure you involve the people who are paying for it.

If you decide to reduce your current technical debt, make that a clear decision: “We will Stop Writing Crappy Code, and Gradually Clean Up The Old Code”.

Once you agree on this (and that’s the hard part), there are plenty of techniques for how to do it. Here are two techniques that I’ve seen work particularly well:

Add to your Definition of Done: “Technical debt reduced”. That means whenever you build a feature or touch the code, you leave the code in a better shape than you found it. Maybe rename a method to make it more clear, or extract some duplicate code to a shared method. Small steps. But if the whole team (or even better, all teams) does this consistently, code quality will noticeably improve within a few months.

For the larger cleanup areas, create a “tech backlog” & reserve time for it. For example, list the top 10 areas of improvement and commit to fixing one every week or sprint, before building any new features.

Just keep in mind that, however you do it, repaying technical debt means Fewer Features in the short term. Adapt your velocity forecasts and release plans accordingly. Just like any investment, there is a short-term cost. Make sure everyone is clear on that.

You need to Slow Down in order to Speed Up.

Final words

Bottom line: code quality is the responsibility of the people who actually write the code (otherwise known as Programmers).

As programmer, you own the problem, and you own the solution. There’s no need to fret or be ashamed of the past. Instead, stand proud and use your power to do something about it – make a loud decision to Stop Writing Crappy Code. That will start a chain of events and Good Stuff will follow in the long term.

Good luck!

/Henrik

June 30, 2013

How to run an internal unconference

An unconference is like a normal conference but with no predefined agenda, no predefined list of speakers, no slides, and…er… actually it’s not very much like a normal conference at all! It’s more like an alternative to a conference. If the purpose of a conference is to collaborate and communicate, then an unconference will often fulfill the same purpose in a more simple, fun, and effective way!

There’s lots of ways of running conferences. I’ve written a short book (or long article) about one specific format that I’ve been experimenting with over the past 5 years, mostly at companies like Crisp and Spotify.

By now it is well tested and works especially well for 1-2 day internal conferences with 20-80 participants. In fact, participants often say things like “all conferences should be like this!” or “best conference I’ve ever been to!”. Even the most rabid meeting-haters seem to like (or at least not hate…) this collaboration format

Slides (from my Agile Evening presentation on how to run an unconference)

Minibook (LeanPub – work in progress)

May 24, 2013

June 17-18: Advanced Agile with Alistair & Henrik

Good news: Alistair Cockburn is in Stockholm June 17-18! We’ll be teaching Advanced Agile, a workshop for those of you who already have agile training and experience, and want to dig deeper!

Register here if you are interested.

Alistair is a very inspiring fellow! He wrote the original book Agile Software Development and was one of the people who started the whole agile movement. He has also written books about Use Cases and agile requirements. Alistair has a great knack for balancing theoretical depth with practical real-life examples and a dose of humor.