Ken MacLeod's Blog, page 17

March 20, 2012

Another brilliant enLIGHTen video

Michael MacLeod has made a time-lapse video that really captures this great project:

Published on March 20, 2012 12:35

enLIGHTen shines on, online

enLIGHTen is over, but you can still enjoy audio, video and images here, as well as photos and tweets.

Here's a time-lapse video of the installation at the Royal Society of Edinburgh:

Here's a time-lapse video of the installation at the Royal Society of Edinburgh:

Published on March 20, 2012 09:39

March 17, 2012

He was a god, Memmius, a god indeed!

I've just read The Swerve: How the Renaissance Began, by Stephen Greenblatt: the new book (referred to below) about the chance discovery in 1417 of the last surviving copy of De Rerum Natura, a long exposition by the Roman poet Lucretius of the philosophy of the ancient Greek materialist, Epicurus.

The finder was Poggio Bracciolini, an indefatigable book-hunter, a fervent reader of Greek and Roman literature, and former secretary to several popes. His most recent pontifical employer sat not in the Vatican but in a dungeon: one of three rival pretenders to the See of Peter, the deposed John XXIII had been arrested and charged with simony, sodomy, rape, incest, torture and murder. Sixteen more serious charges against him had been suppressed for fear of public scandal.

In that era the ideas of Epicurus had survived only as a slander: that he advocated the most luxurious sensual indulgence. With the recovery, copying, and eventual printing of Lucretius, this lie could no longer be repeated, though it survives in the language. Epicurus did indeed urge that pleasure was the only good. His point was that to enjoy life we need very little: food, water, shelter, good company. With that we can be satisfied. Only the desire for more than we need is insatiable. The one luxury he allowed himself was cheese.

In that era the ideas of Epicurus had survived only as a slander: that he advocated the most luxurious sensual indulgence. With the recovery, copying, and eventual printing of Lucretius, this lie could no longer be repeated, though it survives in the language. Epicurus did indeed urge that pleasure was the only good. His point was that to enjoy life we need very little: food, water, shelter, good company. With that we can be satisfied. Only the desire for more than we need is insatiable. The one luxury he allowed himself was cheese.

One idea of his was mocked for much longer: that the fundamental particles of nature every so often and quite unpredictably swerve ever so slightly in their course through the void, and that this is the basis of the free will we all know by experience. The laughter has died since the discovery of quantum mechanics.

Just such an unpredictable swerve, Greenblatt suggests, deflected the course of history as Bracciolini reached for that neglected codex. The ideas expounded by Lucretius - and lucidly and enthusiastically summarised in Greenblatt's central chapter, 'The Way Things Are' - became the basis for the whole modern understanding of the world. The mantra he makes of Epicurus' teaching - 'atoms and the void and nothing else, atoms and the void and nothing else, atoms and the void and nothing else' - has liberated our bodies as well as our souls.

Greenblatt traces the ancient origins and modern influence of this sane and sensible philosophy as it passed through often underground channels, to well up in Montaigne, in Shakespeare, in Jefferson, and in Bruno who was burned in Rome.

Poggio Bracciolini remained a faithful son of the church. He lived to a ripe old age and fathered twenty children, six of them by his wife.

The finder was Poggio Bracciolini, an indefatigable book-hunter, a fervent reader of Greek and Roman literature, and former secretary to several popes. His most recent pontifical employer sat not in the Vatican but in a dungeon: one of three rival pretenders to the See of Peter, the deposed John XXIII had been arrested and charged with simony, sodomy, rape, incest, torture and murder. Sixteen more serious charges against him had been suppressed for fear of public scandal.

In that era the ideas of Epicurus had survived only as a slander: that he advocated the most luxurious sensual indulgence. With the recovery, copying, and eventual printing of Lucretius, this lie could no longer be repeated, though it survives in the language. Epicurus did indeed urge that pleasure was the only good. His point was that to enjoy life we need very little: food, water, shelter, good company. With that we can be satisfied. Only the desire for more than we need is insatiable. The one luxury he allowed himself was cheese.

In that era the ideas of Epicurus had survived only as a slander: that he advocated the most luxurious sensual indulgence. With the recovery, copying, and eventual printing of Lucretius, this lie could no longer be repeated, though it survives in the language. Epicurus did indeed urge that pleasure was the only good. His point was that to enjoy life we need very little: food, water, shelter, good company. With that we can be satisfied. Only the desire for more than we need is insatiable. The one luxury he allowed himself was cheese.One idea of his was mocked for much longer: that the fundamental particles of nature every so often and quite unpredictably swerve ever so slightly in their course through the void, and that this is the basis of the free will we all know by experience. The laughter has died since the discovery of quantum mechanics.

Just such an unpredictable swerve, Greenblatt suggests, deflected the course of history as Bracciolini reached for that neglected codex. The ideas expounded by Lucretius - and lucidly and enthusiastically summarised in Greenblatt's central chapter, 'The Way Things Are' - became the basis for the whole modern understanding of the world. The mantra he makes of Epicurus' teaching - 'atoms and the void and nothing else, atoms and the void and nothing else, atoms and the void and nothing else' - has liberated our bodies as well as our souls.

Greenblatt traces the ancient origins and modern influence of this sane and sensible philosophy as it passed through often underground channels, to well up in Montaigne, in Shakespeare, in Jefferson, and in Bruno who was burned in Rome.

Poggio Bracciolini remained a faithful son of the church. He lived to a ripe old age and fathered twenty children, six of them by his wife.

Published on March 17, 2012 09:56

March 11, 2012

Intrusion: three reviews

Reviews of

Intrusion

in the past few days from:

Gwyneth Jones in Saturday's Guardian, Jill Murphy at The Bookbag, and Michael Flett on GEEKChocolate.

Gwyneth Jones in Saturday's Guardian, Jill Murphy at The Bookbag, and Michael Flett on GEEKChocolate.

Published on March 11, 2012 12:20

March 8, 2012

Singularity&Co.

Published on March 08, 2012 18:58

As we are to the beasts that perish

Crooked Timber, the collective blog of some impressively clever people, has once again rotated its objective lens to focus on science fiction (as it's done several times before), this time to discuss 'libertarian paternalism' aka Nudge and related topics in the light of my novel Intrusion and Charles Stross's Rule 34.

It's an interesting take, because the discussion is largely about the ideas arising from and possibly going into the books rather than the stories themselves, and in my case the opening post focused precisely on a passage that's central to the book's implied argument while giving away nothing of the plot.

Published on March 08, 2012 12:37

March 7, 2012

Scotland

The present state of play in Scottish politics is summed up by crime novelist Quintin Jardine, reflecting on the Labour and LibDem Scottish party conferences:

If the other parties don't watch out, it will be for all of them.

These diminished festivals reminded me that there was a time when I knew by name, sight and reputation, every active political figure of stature in the country. I suppose I still do, but now it's no great claim to make because there are so few of them and they all belong to the same party.Sad but true. Part of the reason, I've long thought, is that in all parties people of ability and ambition want to get to the top, which for all major parties in Scotland except the SNP means Westminster. For the SNP, of course, the Scottish Parliament is the top.

If the other parties don't watch out, it will be for all of them.

Published on March 07, 2012 21:03

Like some watcher of the skies

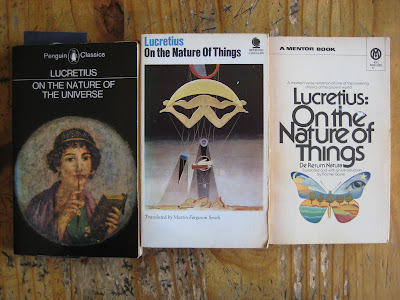

It seems to be in the nature of things that people discover Lucretius by sheer accident. Take this typical account:

'Started reading Lucretius, 'On the Nature of Things'. I'd got the book years ago but got bogged down somewhere around the refutation of Heraclitus. This time my interest and the power of the writing carry me over the drier patches without difficulty ...Or this:

Finished Lucretius. After it there is something dishonourable about being anything other than a materialist.'

In his early teens he had read with delight the poem of Lucretius, in a tatty old paperback published by Sphere Books in 1969 with a Max Ernst picture on the cover. He'd found it in the attic of his parents's house [...] On the inside cover the pencilled words were just legible:Actually, I've cheated: the first quote is from my own appallingly Molish diary from 1977, the second is from Intrusion , and I could as easily add a third, a circumstantially fictitious but emotionally accurate rendering of my own response:

Here rolls

The large verse of Lucretius, who raised

His index-finger and did strike the face

Of fleeting Time, leaving a scar of thought

The rain of ages shall not wash away.

[...] It was an obscure thrill imparted by the lines that impelled him to turn over the pages of the book, and then to read it. He found a great deal in those pages that left imprints on his brain [...]

For the first time in my life, I had heard good news. I drank that black gospel to the lees.

But this one (coincidentally referring to the very same edition) is genuine:

I had very little pocket money, but the bookstore would routinely sell its unwanted titles for ridiculously small sums. They were jumbled together in bins through which I would rummage until something caught my eye. On one of my forays, I was struck by an extremely odd paperback cover, a detail from a painting by the Surrealist Max Ernst. Under a crescent moon, high above the earth, two pairs of legs—the bodies were missing—were engaged in what appeared to be an act of celestial coition. The book, a prose translation of Lucretius' two-thousand-year-old poem "On the Nature of Things" ("De Rerum Natura"), was marked down to ten cents, and I bought it as much for the cover as for the classical account of the material universe.This was the genesis of Stephen Greenblatt's The Swerve, an acclaimed new book on the consequences of the accidental rediscovery of the only surviving copy of Lucretius in medieval Italy.

Ancient physics is not a particularly promising subject for vacation reading, but sometime over the summer I idly picked up the book. The Roman poet begins his work (in Martin Ferguson Smith's careful rendering) with an ardent hymn to Venus [...] Startled by the intensity, I continued, past a prayer for peace, a tribute to the wisdom of the philosopher Epicurus, a resolute condemnation of superstitious fears, and into a lengthy exposition of philosophical first principles. I found the book thrilling.

As an accidental consequence of reading about that book, I stumbled upon a recent translation of Lucretius that I'd never heard of: a 2007 Penguin Classics edition, translated by the distinguished poet A. E. Stallings into rhyming fourteeners - a project that she herself says 'might seem crazy in modern times'. Naturally I bought and read it straight away.

What can I say? It works, and it's a delight.

There's a lot to be said for good prose translations - the lucid, much-loved and recently-revised Penguin Classic by Ronald Latham, the aforementioned careful rendering (also recently-revised) by Martin Ferguson Smith - and modern verse translations such as Rolfe Humphries' The Way Things Are or the dogged, plodding but sometimes soaring regular metre of Palmer Bovie's long out-of-print, poorly-published but well-received 1974 paperback.

But Stallings' quaint relentless drumbeat is in a class of its own, and is the only version anyone is ever likely to memorise and recite lines from. Her handling of the one line everybody knows, the line that Voltaire said would last as long as the world, is a touchstone:

So potent was Religion in persuading to do wrong.

The rhyme-scheme and metre are the same as those Chapman used for his Homer. Some day, perhaps centuries hence, another poet will write 'On First Looking Into Stallings' Lucretius'.

Published on March 07, 2012 11:58

March 6, 2012

The Jura Recovery

Today on the SFX website: an interview with me about my stay on Jura (which I wrote about earlier) and a chance to win a three-night break for two in the Jura Lodge! The pictures of the interior of the Lodge do not exaggerate its quirky splendour in the slightest - this is a prize worth winning.

There's also a direct link to the site where the story itself is now available to read, free. You have to go through a little rigmarole to get there (including affirming that you're of legal age to drink alcohol in your country of residence), but I think you'll find it's worth it - if you like tall tales inspired by an entirely imaginary Scottish space programme and by such mysterious artifacts as the one shown here.

Published on March 06, 2012 19:51

March 3, 2012

Interview in today's Scotsman

About ten days ago Stuart Kelly interviewed me over a cup of coffee in the Abbotsford, an Edinburgh bar that's popular with writers and journalists (and cops and criminals, according to its entirely fictitious representation in The Night Sessions) and he's turned my recorded ramblings into a coherent interview and kindly profile, for which mercy I am truly thankful, as we used to say on Lewis.

Published on March 03, 2012 07:48

Ken MacLeod's Blog

- Ken MacLeod's profile

- 762 followers

Ken MacLeod isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.