Ken MacLeod's Blog, page 19

December 23, 2011

War with the Newts

Karel Čapek's play R.U.R. (Rossum's Universal Robots) set the agenda for the robot in SF, not least by naming it. Its 2011 republication in the Gollancz SF Masterworks series (in one volume with Capek's 1936 novel War with the Newts, and informatively introduced by Adam Roberts) gives us a fresh opportunity to look at this taproot text. We all know the story: robots are created to serve humanity, and after some time they rise up and destroy their human masters. If we've read a little more about the play, we know that Čapek's robots aren't mechanical but quasi-organic: what in later SF would be called androids or replicants. Few of us have actually read it. More of us should.

Karel Čapek's play R.U.R. (Rossum's Universal Robots) set the agenda for the robot in SF, not least by naming it. Its 2011 republication in the Gollancz SF Masterworks series (in one volume with Capek's 1936 novel War with the Newts, and informatively introduced by Adam Roberts) gives us a fresh opportunity to look at this taproot text. We all know the story: robots are created to serve humanity, and after some time they rise up and destroy their human masters. If we've read a little more about the play, we know that Čapek's robots aren't mechanical but quasi-organic: what in later SF would be called androids or replicants. Few of us have actually read it. More of us should.I didn't know until I read the play a few weeks ago that it's funny. And I'd never reflected on the significance of its place and date of publication: Prague, 1920. When the risen robots issue a manifesto to all the robots of the world, propagated in leaflets by the shipload, the echo of the Russian revolution is loud and clear. Other aspects of the rebellion evoke a slave - or colonial - uprising. From their first clunky steps, robots in SF have carried a heavy freight of human anxieties.

A month ago I spent three days in Amsterdam, as a guest of the International Conference on Social Robotics 2011, where I gave the closing keynote. The opening keynote was by a much more consequent speaker: the academic, inventor and entrepreneur Tomotaka Takahashi, who charmed and amazed us all with his cute and accomplished humanoid ROPID and his energetic toy robot Evolta (of Panasonic battery ad fame), and gave us an intriguing rationale for creating small humanoid robots: small for safety, humanoid because we can talk to them without feeling self-conscious, thus making them an ideal interface for all the other gadgets we have around the house. But the best reason, he said, was 'creating new fun', as Steve Jobs did with the iPhone.

A month ago I spent three days in Amsterdam, as a guest of the International Conference on Social Robotics 2011, where I gave the closing keynote. The opening keynote was by a much more consequent speaker: the academic, inventor and entrepreneur Tomotaka Takahashi, who charmed and amazed us all with his cute and accomplished humanoid ROPID and his energetic toy robot Evolta (of Panasonic battery ad fame), and gave us an intriguing rationale for creating small humanoid robots: small for safety, humanoid because we can talk to them without feeling self-conscious, thus making them an ideal interface for all the other gadgets we have around the house. But the best reason, he said, was 'creating new fun', as Steve Jobs did with the iPhone.

There was much fun to be had: social robotics is a new and thriving field, looking at the integration of robots into society through a cluster of lenses, from the technical through the sociological to the cultural. Papers presented ranged from empirical studies of human-robot interaction to such wonderfully speculative flights as the pressing question of whom (or what) to sue if a sexbot AI steals your partner's affections.

There was a lively exhibit of work-in-progress posters, some accompanied by demonstrations of actual robots. The programmable Nao robot has become a test platform for much research, and has even been used in robot theatre and stand-up. (I suggested to Heather Knight, the impressario of these events, that a production of R.U.R. with Nao robots would be screamingly funny, but she didn't think it feasible.) Some intrepid engineers are even working on general-purpose humanoid household robots, and pit their creations against each other in the competition RoboCup@Home (inspired by the robot football competition, RoboCup) with sometimes hilarious results.

There was a lively exhibit of work-in-progress posters, some accompanied by demonstrations of actual robots. The programmable Nao robot has become a test platform for much research, and has even been used in robot theatre and stand-up. (I suggested to Heather Knight, the impressario of these events, that a production of R.U.R. with Nao robots would be screamingly funny, but she didn't think it feasible.) Some intrepid engineers are even working on general-purpose humanoid household robots, and pit their creations against each other in the competition RoboCup@Home (inspired by the robot football competition, RoboCup) with sometimes hilarious results. My impressions, from the exhibits and from the entries in the competition which I took part in judging, are that some of the most immediately applicable work is being done with unwell children and the frail elderly. Children with autism, in particular, seem to benefit measurably from interaction with friendly, cuddly robots. These robots are sophisticated, but remotely controlled in real time by concealed operators - what's known as the 'Wizard of Oz' approach, which is also widely used as a quick-and-dirty method of gauging human-robot interaction.

I find myself wondering whether we'd be working with humanoid robots at all, let alone mentally and verbally classifying them with mechanisms as diverse as autonomous vaccum-cleaners and industrial arms, if it weren't for SF, through Dick and Asimov and all the way back to Čapek. Just as well, perhaps, that intelligent marine creatures haven't crawled ashore - yet.

Published on December 23, 2011 10:48

December 12, 2011

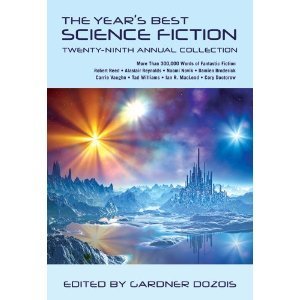

Year's Best SF 29

The table of contents for Gardner Dozois's 2012 anthology The Year's Best Science Fiction: Twenty-Ninth Annual Collection is now online, and I'm very pleased to say that I have two stories in it: 'Earth Hour' and 'The Vorkuta Event'.

Given the eldritch viccissitudes that the latter story went through before its eventual (and still viccissitude-dogged) truly splendid publication, I am even more well chuffed than you might expect.

Published on December 12, 2011 11:15

December 2, 2011

The word from a silent sky

Yesterday I read Karl Schroeder's post on a new paper on the Fermi Paradox. Karl makes the interesting suggestion that if aliens exist, their technologies are indistinguishable from natural objects. Karl had come up with the idea of a technology indistinguishable from nature in the quite different context of trying to imagine the future development of our technology. He takes the apparent absence of aliens as at least consistent with this projection: if it holds true for us, and if we are not alone, and if we are a typical intelligent species, then a Galaxy swarming with alien civilizations would look (to us, now) just like a Galaxy with no aliens at all. So what we see (and, more to the point, don't see) is just what we would expect.

It strikes me that the arguments over the existence of aliens have an interesting structural similarity to certain arguments over the existence of God. There's a type of atheist argument that says, in so many words, that the non-existence of God is manifest by just looking out of the window: if God existed, we would know about it. There's a type of theist argument that says if God exists, his existence is necessarily hidden from us, and the world outside the window - a universe that looks as if it works all by itself - is just what we would expect.

Discuss.

It strikes me that the arguments over the existence of aliens have an interesting structural similarity to certain arguments over the existence of God. There's a type of atheist argument that says, in so many words, that the non-existence of God is manifest by just looking out of the window: if God existed, we would know about it. There's a type of theist argument that says if God exists, his existence is necessarily hidden from us, and the world outside the window - a universe that looks as if it works all by itself - is just what we would expect.

Discuss.

Published on December 02, 2011 12:56

November 17, 2011

Observing the Leonid Meteor Shower

I'm sure my talented brother James could do a better job of this, but here it is anyway, on a rainy night in South Queensferry.

Published on November 17, 2011 20:34

November 10, 2011

Where do you get your (Battle of) Ideas from?

As I mentioned below, I attended and took part in this year's Battle of Ideas, an event I also took part in two years ago.

(In case anyone doesn't know: Battle of Ideas is an annual weekend festival of controversy that is itself controversial because of the connections of its organizers, the Institute of Ideas, with a long-disbanded far-left organization and its successors, currently represented by the online current affairs magazine spiked. For a somewhat bemused but balanced liberal account, see Jenny Turner's article in LRB; for a critical conservative appreciation of the group's development, check this article; and if you want the full-on left-wing conspiracy account, PowerBase, SourceWatch, and LobbyWatch will keep you entertained for hours.)

For me, a highlight of the weekend was a discussion on mind-body dualism, featuring Raymond Tallis, Richard Swinburne, Stuart Darbyshire and Martha Robinson, and chaired by Sandy Starr.

My initial sympathies in the debate were with Martha Robinson, a neuroscience PhD student and naive mechanical materialist, up against: a polymathic professor and self-professed neurosceptic; a distinguished philosopher of religion (defending, in this instance, the soul rather than God); and two dialectical materialists. (Derbyshire and Starr are both frequent contributors to spiked.) Just to confuse matters, Stuart Derbyshire referred disparagingly to Martha Robinson's view as 'materialism', while himself elaborating (as I pointed out from the floor, to no avail) a materialist view.

His contribution went like this: Consciousness is not a separate substance, but neither is it a product simply of the brain. The brain is necessary for it, but looking for consciousness in the brain is like looking for sunshine in a cucumber. In individual human development, consciousness arises from and goes beyond the infant's natural mental endowment when the infant learns language. Language liberates consciousness from elementary mental functions, allowing the use of abstraction and symbol rather than simple stimuli. Mind arises within a social process, originally in the interaction of the infant and its care-givers, and subsequently broadening out to include the whole of society. You didn't work out the Periodic Table, but you know it; likewise much else that's in your head. Not many of us, after all, coin new words, at least not words that come into general use. In a sense, your conscious experience doesn't belong to you, and that's why consciousness seems ghostly and weird.

I didn't agree with this at all, or even understand it, but while heading for King's Cross on the Tube the following day I was thinking it over while idly observing my fellow passengers reading or talking or staring into space and it clicked. Consciousness is social, it's uniquely human, it's not just going on in our separate heads but between them, in our interactions.

But ... wait a minute ... if that's the case then ... social consciousness is really important.

And it changes - and can be changed by - every individual.

Ideas matter.

Uh-oh.

When I got home I checked out the recommended reading for the event, and found right at the end a link to a work of Soviet psychology, and from that a whole archive of links to the works of Vygotsky and the school of thought he founded and the astonishing and inspiring humane applications that it led to, and the terrible vicissitudes of this school of psychology before and after it made its way to the West. Strangely enough, the very same view of consciousness that Vygotsky pioneered and that I heard Stuart Derbyshire outline can be found in all the boring Brezhnev-era textbooks of dialectical materialism.

By what a frail aqueduct did the fallen empire convey to a future civilization that most surprising discovery of Marxism-Leninism: the individual human consciousness, the soul!

Published on November 10, 2011 17:49

November 2, 2011

Now available!

Earlier this year, world-famous economist Brad DeLong asked 'Why is there no ebook of Ken MacLeod's "The Restoration Game"? This offends the order of reality, somehow... '

The order of reality has now been saved by Barnes and Noble, so feel to get on with the reality of ordering.

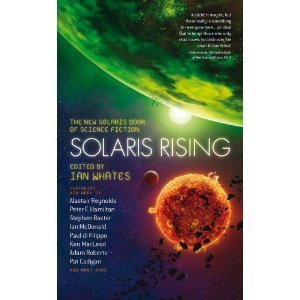

Elswhere, Solaris Rising: the New Solaris Book of Science Fiction, in which I have a short story titled 'The Best Science Fiction of the Year Three', has just been released, and is available on Amazon in the UK, the US, and Canada. There's already a favourable review at Locus Online (along with a likewise favourable review of

Technology Review: Science Fiction

.

Elswhere, Solaris Rising: the New Solaris Book of Science Fiction, in which I have a short story titled 'The Best Science Fiction of the Year Three', has just been released, and is available on Amazon in the UK, the US, and Canada. There's already a favourable review at Locus Online (along with a likewise favourable review of

Technology Review: Science Fiction

.

(Pic and links via Richard Salter, a fellow contributor.)

The order of reality has now been saved by Barnes and Noble, so feel to get on with the reality of ordering.

Elswhere, Solaris Rising: the New Solaris Book of Science Fiction, in which I have a short story titled 'The Best Science Fiction of the Year Three', has just been released, and is available on Amazon in the UK, the US, and Canada. There's already a favourable review at Locus Online (along with a likewise favourable review of

Technology Review: Science Fiction

.

Elswhere, Solaris Rising: the New Solaris Book of Science Fiction, in which I have a short story titled 'The Best Science Fiction of the Year Three', has just been released, and is available on Amazon in the UK, the US, and Canada. There's already a favourable review at Locus Online (along with a likewise favourable review of

Technology Review: Science Fiction

.(Pic and links via Richard Salter, a fellow contributor.)

Published on November 02, 2011 12:27

Orwell's other island

At the beginning of October I spent a week on Jura, courtesy of the Scottish Book Trust and Jura Single Malt Whisky. The Jura Lodge is easily the most wonderful house I've ever stayed in: imagine the holiday home of a wealthy family with improbably good, if eccentric, taste and a magpie's eye for Victoriana and natural history. At first I thought that's what it was. I was surprised to learn that it was all a recent fabrication, designed by a talented interior decorator. Lots of writers have stayed there under various versions of the scheme, and I'm grateful for my week. All I have to do in return is write a short SF story set on Jura, to be published exclusively on the company's website and (in hard-copy) in a collection in the Jura Hotel. I'm not even expected to say a good word for the whisky, though I will: Whyte & MacKay is one of my favourite blends, and the 16-year-old Jura single malt could quite aptly be labelled Revelation (alongside the Jura distillery's two other labelled expressions, Superstition and Prophecy) though it isn't.

I spent a lot of time outdoors, often getting thoroughly cold and wet, but I also had plenty of time and space to read and write. And naturally enough, in this cheery environment I thought about the gloomiest writer who ever stayed on Jura. I'd recently re-read Nineteen Eighty-Four for the SFX Book Club, and - in dark evenings and the odd torrential afternoon - on Jura I browsed through

The Penguin Essays of George Orwell

, as well as the informative locally-published booklet 'Orwell on Jura', and an essay on the same subject by Bernard Crick in a nice little collection,

Spirit of Jura: Fiction, Essays, Poems from the Jura Lodge

, copies of which are liberally scattered around the house.

I spent a lot of time outdoors, often getting thoroughly cold and wet, but I also had plenty of time and space to read and write. And naturally enough, in this cheery environment I thought about the gloomiest writer who ever stayed on Jura. I'd recently re-read Nineteen Eighty-Four for the SFX Book Club, and - in dark evenings and the odd torrential afternoon - on Jura I browsed through

The Penguin Essays of George Orwell

, as well as the informative locally-published booklet 'Orwell on Jura', and an essay on the same subject by Bernard Crick in a nice little collection,

Spirit of Jura: Fiction, Essays, Poems from the Jura Lodge

, copies of which are liberally scattered around the house.

There's a common misconception about Orwell on Jura: that he went there to die, and that in going there he more or less deliberately made sure that he would. This is usually accompanied by a mental image of Jura as a remote, cold, wet, wind-swept miserable place, more or less ideal for writing a grey dystopia and then pegging out. Not a bit of it! Jura's climate, though indeed wet and windy, is mild. Palm trees grow in front of the hotel. Lizards live in the drystone dykes. The island is only remote in the sense that it's a (breathtakingly scenic) trek to get there. It's less than a hundred miles west of Glasgow. As Bernard Crick put it, Orwell didn't go there to die, he went there to write.

Re-reading his essays brought me to a thought that rather surprised me:

If George Orwell hadn't written Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, he'd be remembered as the author of a few depressing novels. Selections from his non-fiction would now and again be reprinted by AK or Pluto Press, with kindly introductions by Michael Foot or Tony Benn. The political right would have no interest in him at all.

If George Orwell hadn't written Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, he'd be remembered as the author of a few depressing novels. Selections from his non-fiction would now and again be reprinted by AK or Pluto Press, with kindly introductions by Michael Foot or Tony Benn. The political right would have no interest in him at all.

He's always a pleasure to read, but as a political thinker he was neither original nor important. His criticisms of the left were sometimes unfair, but hardly unique. On the rare occasions when he put forward a positive programme of his own, or endorsed that of others, there's not a cigarette paper between him and the state socialists. Considered purely as a platform, 'The Lion and the Unicorn' shares a surprising number of planks with 'The British Road to Socialism' though to be fair the latter doesn't look forward to blood running in the gutters and red militias billeted in the Ritz.

Orwell's writings have an odd place in British culture. For many people, Orwell's essays and books are the only political writings from the 1930s and 40s they'll ever read. A fair bit of Orwell's political writing from that time consists of disparaging other political writing of the period - particularly the writing of the left. From 'Politics and the English Language' you can get the impression that such political writing consisted mostly of crass apologetics in dreadful prose. The result is that nobody bothers to read it, and Orwell's view reigns unchallenged.

'If you simplify your English, you are freed from the worst follies of orthodoxy. You cannot speak any of the necessary dialects, and when you make a stupid remark its stupidity will be obvious, even to yourself.'

I wish.

There's no necessary connection between political truth and verbal clarity. Let's take some writers whose politics Orwell would reject. Nothing could be stronger than Orwell's detestation of Fabianism and Stalinism. George Bernard Shaw stood for the first and more or less endorsed the second, yet The Intelligent Woman's Guide to Socialism is a delight to read. Not all the Communists and fellow-travellers were hacks. (Orwell's citation of a rant from that quarter is tellingly under-referenced: 'Communist pamphlet' - I ask you!) T. A. Jackson and A. L. Morton wrote their best-known books in clear and vivid English. John Strachey was at his most lucid when he was at his most wrong. Professor J. B. S. Haldane's science essays are still read for pleasure. The Trotskyist C. L. R. James wrote one literary masterpiece; Trotsky himself was constitutionally incapable of writing a dull page, and in Max Eastman he found a translator worthy of his style. On the democratic, non-Marxist left, Lancelot Hogben, one of whose lazier paragraphs Orwell's famous essay holds up to scorn, was the author of Mathematics for the Million and Science for the Citizen - he was no Isaac Asimov, I'll give you that, but mastering these two books can set you up for life (or university, at any rate) which is more than can be said for Asimov's Guide to Science, fine volume though that is. Hogben's two big books sold hundreds of thousands. His style can't have stood in many readers' way.

That's not to say Orwell didn't have a point. I've always relished this passage from Perry Anderson's Considerations on Western Marxism:

Well! - what you can say is that if you work your way through Anderson's egregious collocation of vocables (and yes, I have looked up 'egregious') every word of this makes sense, and for all I know may even be true.

I spent a lot of time outdoors, often getting thoroughly cold and wet, but I also had plenty of time and space to read and write. And naturally enough, in this cheery environment I thought about the gloomiest writer who ever stayed on Jura. I'd recently re-read Nineteen Eighty-Four for the SFX Book Club, and - in dark evenings and the odd torrential afternoon - on Jura I browsed through

The Penguin Essays of George Orwell

, as well as the informative locally-published booklet 'Orwell on Jura', and an essay on the same subject by Bernard Crick in a nice little collection,

Spirit of Jura: Fiction, Essays, Poems from the Jura Lodge

, copies of which are liberally scattered around the house.

I spent a lot of time outdoors, often getting thoroughly cold and wet, but I also had plenty of time and space to read and write. And naturally enough, in this cheery environment I thought about the gloomiest writer who ever stayed on Jura. I'd recently re-read Nineteen Eighty-Four for the SFX Book Club, and - in dark evenings and the odd torrential afternoon - on Jura I browsed through

The Penguin Essays of George Orwell

, as well as the informative locally-published booklet 'Orwell on Jura', and an essay on the same subject by Bernard Crick in a nice little collection,

Spirit of Jura: Fiction, Essays, Poems from the Jura Lodge

, copies of which are liberally scattered around the house. There's a common misconception about Orwell on Jura: that he went there to die, and that in going there he more or less deliberately made sure that he would. This is usually accompanied by a mental image of Jura as a remote, cold, wet, wind-swept miserable place, more or less ideal for writing a grey dystopia and then pegging out. Not a bit of it! Jura's climate, though indeed wet and windy, is mild. Palm trees grow in front of the hotel. Lizards live in the drystone dykes. The island is only remote in the sense that it's a (breathtakingly scenic) trek to get there. It's less than a hundred miles west of Glasgow. As Bernard Crick put it, Orwell didn't go there to die, he went there to write.

Re-reading his essays brought me to a thought that rather surprised me:

If George Orwell hadn't written Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, he'd be remembered as the author of a few depressing novels. Selections from his non-fiction would now and again be reprinted by AK or Pluto Press, with kindly introductions by Michael Foot or Tony Benn. The political right would have no interest in him at all.

If George Orwell hadn't written Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, he'd be remembered as the author of a few depressing novels. Selections from his non-fiction would now and again be reprinted by AK or Pluto Press, with kindly introductions by Michael Foot or Tony Benn. The political right would have no interest in him at all.He's always a pleasure to read, but as a political thinker he was neither original nor important. His criticisms of the left were sometimes unfair, but hardly unique. On the rare occasions when he put forward a positive programme of his own, or endorsed that of others, there's not a cigarette paper between him and the state socialists. Considered purely as a platform, 'The Lion and the Unicorn' shares a surprising number of planks with 'The British Road to Socialism' though to be fair the latter doesn't look forward to blood running in the gutters and red militias billeted in the Ritz.

Orwell's writings have an odd place in British culture. For many people, Orwell's essays and books are the only political writings from the 1930s and 40s they'll ever read. A fair bit of Orwell's political writing from that time consists of disparaging other political writing of the period - particularly the writing of the left. From 'Politics and the English Language' you can get the impression that such political writing consisted mostly of crass apologetics in dreadful prose. The result is that nobody bothers to read it, and Orwell's view reigns unchallenged.

'If you simplify your English, you are freed from the worst follies of orthodoxy. You cannot speak any of the necessary dialects, and when you make a stupid remark its stupidity will be obvious, even to yourself.'

I wish.

There's no necessary connection between political truth and verbal clarity. Let's take some writers whose politics Orwell would reject. Nothing could be stronger than Orwell's detestation of Fabianism and Stalinism. George Bernard Shaw stood for the first and more or less endorsed the second, yet The Intelligent Woman's Guide to Socialism is a delight to read. Not all the Communists and fellow-travellers were hacks. (Orwell's citation of a rant from that quarter is tellingly under-referenced: 'Communist pamphlet' - I ask you!) T. A. Jackson and A. L. Morton wrote their best-known books in clear and vivid English. John Strachey was at his most lucid when he was at his most wrong. Professor J. B. S. Haldane's science essays are still read for pleasure. The Trotskyist C. L. R. James wrote one literary masterpiece; Trotsky himself was constitutionally incapable of writing a dull page, and in Max Eastman he found a translator worthy of his style. On the democratic, non-Marxist left, Lancelot Hogben, one of whose lazier paragraphs Orwell's famous essay holds up to scorn, was the author of Mathematics for the Million and Science for the Citizen - he was no Isaac Asimov, I'll give you that, but mastering these two books can set you up for life (or university, at any rate) which is more than can be said for Asimov's Guide to Science, fine volume though that is. Hogben's two big books sold hundreds of thousands. His style can't have stood in many readers' way.

That's not to say Orwell didn't have a point. I've always relished this passage from Perry Anderson's Considerations on Western Marxism:

By contrast [with Marx's published work], the extreme difficulty of language characteristic of much of Western Marxism in the twentieth century was never controlled by the tension of a direct or active relationship to a proletarian audience. On the contrary, its very surplus above the necessary minimum quotient of verbal complexity was the sign of its divorce from any popular practice. The peculiar esotericism of Western Marxist theory was to assume manifold forms: in Lukacs, a cumbersome and abstruse diction, freighted with academicism; in Gramsci, a painful and cryptic fragmentation, imposed by prison; in Benjamin, a gnomic brevity and indirection; in Della Volpe, an impenetrable syntax and circular self-reference; in Sartre, a hermetic and unrelenting maze of neologisms; in Althusser, a sybilline rhetoric of elusion.What can you say?

Well! - what you can say is that if you work your way through Anderson's egregious collocation of vocables (and yes, I have looked up 'egregious') every word of this makes sense, and for all I know may even be true.

Published on November 02, 2011 11:05

October 26, 2011

Battle of Ideas 2011

This Saturday I'm taking part in a discussion on 'Sci-fi and the future' at Battle of Ideas 2011. Having been at this annual event a few times already, I'm expecting a hard-hitting and focussed discussion, and a lot of other interesting debates over the weekend. It's one of the few conference or festival-type events I've been to where almost every discussion you overhear or or join in the corridors and bars is about ideas.

On Thursday evening I'm hoping to meet some SF fans for a few drinks in a pub in the Covent Garden area. If you'd like to join us, please email (address at left) or DM me on Twitter today.

On Thursday evening I'm hoping to meet some SF fans for a few drinks in a pub in the Covent Garden area. If you'd like to join us, please email (address at left) or DM me on Twitter today.

Published on October 26, 2011 13:31

October 11, 2011

Lenin on the BBC

Unless you have a phobia about dodgy plumbers or timeshare scams, The One Show isn't the sort of programme you watch to be scared. It's a cosy after-dinner easy-watching chat-show. In tonight's episode, Justin Rowlatt interviewed an economics commenter (whose name I didn't catch) who gave what he called 'an extreme view' of what's at stake in the euro crisis. She said that 'if the euro goes down' Britain is in for 'a long, dark recession' which could lead to massive civil unrest and ... wars. Since the UK is already involved in three wars against in underdeveloped countries, I think she meant wars between advanced countries. You know, proper wars, like those your parents or grandparents fought in and didn't talk about much.

Jeremy Paxman, also interviewed tonight, looked withdrawn and thoughtful during the brief studio discussion that followed. He didn't look scornful or sceptical. But then, he was there to talk about his new book, on the British Empire.

Now, until I know who the economist was, I have no way of judging her credibility. Leaving that aside, though, it's the first time I've heard this idea - that a crisis of capitalism can lead to revolutionary situations and/or inter-imperialist wars - even mooted in the mainstream media. Is a non-apocalyptic WW3 even possible? It's hard to imagine something between, say, the break-up of Yugoslavia and the cataclysmic Cold War visions of the final war (though I've tried). That strikes me as a good reason why we might be well advised to consider other possible responses to the crisis. Devising a feasible socialism is demonstrably not beyond human capacity, though finding a party advancing or even discussing anything of the sort is beyond mine.

But, as usual, the programme didn't leave us to wallow in gloom. Our spirits were lifted by a cheery little item about the proud welders and engineers and electricians of Barrow-on-Furness, building Britain's latest nuclear submarine.

Jeremy Paxman, also interviewed tonight, looked withdrawn and thoughtful during the brief studio discussion that followed. He didn't look scornful or sceptical. But then, he was there to talk about his new book, on the British Empire.

Now, until I know who the economist was, I have no way of judging her credibility. Leaving that aside, though, it's the first time I've heard this idea - that a crisis of capitalism can lead to revolutionary situations and/or inter-imperialist wars - even mooted in the mainstream media. Is a non-apocalyptic WW3 even possible? It's hard to imagine something between, say, the break-up of Yugoslavia and the cataclysmic Cold War visions of the final war (though I've tried). That strikes me as a good reason why we might be well advised to consider other possible responses to the crisis. Devising a feasible socialism is demonstrably not beyond human capacity, though finding a party advancing or even discussing anything of the sort is beyond mine.

But, as usual, the programme didn't leave us to wallow in gloom. Our spirits were lifted by a cheery little item about the proud welders and engineers and electricians of Barrow-on-Furness, building Britain's latest nuclear submarine.

Published on October 11, 2011 21:10

October 2, 2011

The near future arrives this week

A few months ago I was asked to contribute a story to a special science fiction issue of MIT's Technology Review . The idea was that each story would reflect one of the site's regular channels: business, computing, biomedicine, etc. I chose 'Materials' because I had a small and now distant background in the subject. After some hasty thumbing through The New Science of Strong Materials and other battered Pelicans on my shelf I thought of and discarded several ideas, and only came up with one when I turned to the site itself and came across a recent development in light-bending metamaterials. Aha! I brainstormed some ideas with

That story was accepted, and is now out in very respectable company. Copies of the anthology are available for pre-order, and hit the newstands on Tuesday 4 October, with digital editions soon to follow. (Via.)

Published on October 02, 2011 10:39

Ken MacLeod's Blog

- Ken MacLeod's profile

- 762 followers

Ken MacLeod isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.