Like some watcher of the skies

It seems to be in the nature of things that people discover Lucretius by sheer accident. Take this typical account:

'Started reading Lucretius, 'On the Nature of Things'. I'd got the book years ago but got bogged down somewhere around the refutation of Heraclitus. This time my interest and the power of the writing carry me over the drier patches without difficulty ...Or this:

Finished Lucretius. After it there is something dishonourable about being anything other than a materialist.'

In his early teens he had read with delight the poem of Lucretius, in a tatty old paperback published by Sphere Books in 1969 with a Max Ernst picture on the cover. He'd found it in the attic of his parents's house [...] On the inside cover the pencilled words were just legible:Actually, I've cheated: the first quote is from my own appallingly Molish diary from 1977, the second is from Intrusion , and I could as easily add a third, a circumstantially fictitious but emotionally accurate rendering of my own response:

Here rolls

The large verse of Lucretius, who raised

His index-finger and did strike the face

Of fleeting Time, leaving a scar of thought

The rain of ages shall not wash away.

[...] It was an obscure thrill imparted by the lines that impelled him to turn over the pages of the book, and then to read it. He found a great deal in those pages that left imprints on his brain [...]

For the first time in my life, I had heard good news. I drank that black gospel to the lees.

But this one (coincidentally referring to the very same edition) is genuine:

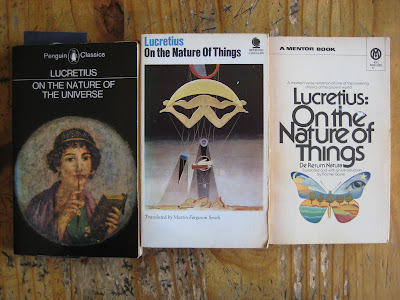

I had very little pocket money, but the bookstore would routinely sell its unwanted titles for ridiculously small sums. They were jumbled together in bins through which I would rummage until something caught my eye. On one of my forays, I was struck by an extremely odd paperback cover, a detail from a painting by the Surrealist Max Ernst. Under a crescent moon, high above the earth, two pairs of legs—the bodies were missing—were engaged in what appeared to be an act of celestial coition. The book, a prose translation of Lucretius' two-thousand-year-old poem "On the Nature of Things" ("De Rerum Natura"), was marked down to ten cents, and I bought it as much for the cover as for the classical account of the material universe.This was the genesis of Stephen Greenblatt's The Swerve, an acclaimed new book on the consequences of the accidental rediscovery of the only surviving copy of Lucretius in medieval Italy.

Ancient physics is not a particularly promising subject for vacation reading, but sometime over the summer I idly picked up the book. The Roman poet begins his work (in Martin Ferguson Smith's careful rendering) with an ardent hymn to Venus [...] Startled by the intensity, I continued, past a prayer for peace, a tribute to the wisdom of the philosopher Epicurus, a resolute condemnation of superstitious fears, and into a lengthy exposition of philosophical first principles. I found the book thrilling.

As an accidental consequence of reading about that book, I stumbled upon a recent translation of Lucretius that I'd never heard of: a 2007 Penguin Classics edition, translated by the distinguished poet A. E. Stallings into rhyming fourteeners - a project that she herself says 'might seem crazy in modern times'. Naturally I bought and read it straight away.

What can I say? It works, and it's a delight.

There's a lot to be said for good prose translations - the lucid, much-loved and recently-revised Penguin Classic by Ronald Latham, the aforementioned careful rendering (also recently-revised) by Martin Ferguson Smith - and modern verse translations such as Rolfe Humphries' The Way Things Are or the dogged, plodding but sometimes soaring regular metre of Palmer Bovie's long out-of-print, poorly-published but well-received 1974 paperback.

But Stallings' quaint relentless drumbeat is in a class of its own, and is the only version anyone is ever likely to memorise and recite lines from. Her handling of the one line everybody knows, the line that Voltaire said would last as long as the world, is a touchstone:

So potent was Religion in persuading to do wrong.

The rhyme-scheme and metre are the same as those Chapman used for his Homer. Some day, perhaps centuries hence, another poet will write 'On First Looking Into Stallings' Lucretius'.

Published on March 07, 2012 11:58

No comments have been added yet.

Ken MacLeod's Blog

- Ken MacLeod's profile

- 762 followers

Ken MacLeod isn't a Goodreads Author

(yet),

but they

do have a blog,

so here are some recent posts imported from

their feed.