Rob Brotherton's Blog, page 3

March 3, 2017

Conspiracy theories can sometimes bolster rather than undermine support for the status quo

In a recent paper published in Political Psychology by myself from Staffordshire University and Karen Douglas and Robbie Sutton from the University of Kent, we found that conspiracy theories might be a way that people can maintain favourable attitudes towards society when the social system may be under threat. In other words, conspiracy theories may sometimes bolster rather than undermine support for the social status quo when its legitimacy is threatened.

Conspiracy theories are associated with almost every significant social and political event, such as the suggested theory that the U.S. government orchestrated the 9/11 attacks. A similar thread throughout conspiracy narratives is that they point accusing fingers at authority (such as the government). Conspiracy theories single out a small group of perceived wrongdoers who are not representative of society more generally but instead are working against us. Believing in conspiracy theories may, therefore, give people the opportunity to blame the negative actions on these wrongdoers, thus then bolstering support for the social system in general; blaming a few bad apples to save a threatened barrel.

[image error]

This argument is in line with System Justification Theory which proposes that we all have a motivation to hold positive views about the society that we live in. When our society is threatened, however, we seek to defend or bolster the status quo; for example, people may use stereotypes – which are mental shortcuts about different groups of people – to justify differences between people to maintain the status quo that we are used to. In our new paper, we argue that belief in conspiracy theories may join the ranks of these system-justification processes.

We tested the system-justifying idea across several research studies, using both undergraduate students and members of the general public. We found that conspiracy theories increased when the legitimacy of society was threatened, and that also being exposed to conspiracy theories increased satisfaction with the status quo when under threat. We found that conspiracy theories were able to increase satisfaction with society in general because people blamed society’s problems on a small group of wrongdoers, rather than society in general.

This research provides a new understanding of the role that conspiracy theories may play in our society. To directly quote the end of the paper: “The present results suggest that by pointing fingers at individuals – even groups of individuals charged with operating the system – conspiracy theories may exonerate the system, just as blaming a driver for a car crash shifts blame from the car.”

A open-access copy of the paper can be downloaded via Research Gate.

This post has been re-published from InPsych @ Staffordshire University.

December 8, 2016

Conspiracy theories in the workplace

Conspiracy theories have been shown to have potentially detrimental consequences on political, environmental, and health-related behaviour intentions. We have discussed these consequences on the blog previously. Recently, psychologists have extended this and explored how conspiracy theories may also impact our day-to-day working lives.

Prof. Karen Douglas and Dr Ana Leite define organisation conspiracy theories in their 2016 British Journal of Psychology paper as “notions that powerful groups (e.g., managers) within the workplace are acting in secret to achieve some kind of malevolent objective”. They argue organisation conspiracy theories are different from gossip and rumour, as organisation conspiracy theories are typically conspiracies between individuals, such as working together to get an employee fired.

Douglas and Leite found across three studies that organisation conspiracy theories were related to decreased organisational commitment and job satisfaction, thus then leading to increased turnover intentions. In other words, people were more likely to want to leave their current job.

This research underlines the potentially detrimental consequences of conspiracy theories. Not only can they potentially lead to disengagement in important social systems but may also lead to disengagement in the workplace. The researchers, therefore, conclude that managers need to be mindful of the effects of conspiracy theories and not dismiss them as harmless rumour or gossip.

If you are interested in reading the full paper, you can access a PDF copy here.

November 8, 2016

What suspicion tells us about beliefs in conspiracy theories

Have a look at the statements below, and think about how much you agree with each of them on a 1-5 scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

The real truth about 9/11 is being kept from the public.

People need to wake up and start asking questions about 9/11.

Legitimate questions about 9/11 are being suppressed by the government, the media, and academia.

Reporters, scientists, and government officials are involved in a conspiracy to cover up important information about 9/11.

An impartial, independent investigation of 9/11 would show once and for all that we’ve been lied to on a massive scale.

Add up your scores, and you have a measure of how suspicious you are that there’s some kind of ongoing conspiracy surrounding 9/11. Now, do the same with these statements.

The real truth about the moon landings is being kept from the public.

People need to wake up and start asking questions about the moon landings.

Legitimate questions about the moon landings are being suppressed by the government, the media, and academia.

Reporters, scientists, and government officials are involved in a conspiracy to cover up important information about the moon landings.

An impartial, independent investigation of the moon landings would show once and for all that we’ve been lied to on a massive scale.

That looks familiar! This is called the FICS – the Flexible Inventory of Conspiracy Suspicions. It’s a sort of fill-in-the-blanks, conspiracy theory Mad Libs thing – a new innovation in measuring conspiracy theory beliefs. You can put nearly* any topic of public interest in there, and end up with a valid measure of suspicions that there’s a conspiracy to do with it. I’ve written an article proposing and validating this approach, and was fortunate enough to have it accepted to the British Journal of Psychology. It went up on Early View this week, so you can check it out if you have access to the journal. More info about it after the jump – including how this tells us something about the way that conspiracy beliefs are structured.

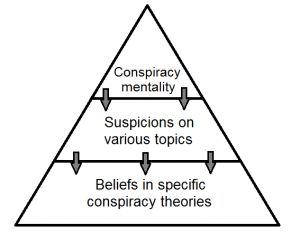

We know that people’s opinions on conspiracy theories tend to hang together. Conspiracy theories are something that people tend to be generally into or not, to varying degrees. If you ask someone for their opinion on whether 9/11 was an inside job, you can use that information to predict (pretty accurately) what they think about whether Princess Diana was assassinated, whether the moon landing was faked, and whether the media is programming us with subliminal mind control. Current thought says this is because people’s worldviews are more or less “conspiracist” – that is, people have a general opinion on how common conspiracies are, the degree to which powerful people tend to conspire against the common good, how easy it is to cover up conspiracies, and so on. You can measure this tendency with questionnaires like Rob’s Generic Conspiracist Beliefs Scale, or Bruder et al.’s Conspiracy Mentality Questionnaire. People who score high on these scales tend to believe a lot of conspiracy theories; people who score low tend to believe relatively few.

Often psychologists are interested in general conspiracy mentality, but will still ask about specific theories, because they’re interested in specific topics. Dan’s study of vaccine theories asked about a laundry list of specific dangers of vaccines – do they cause allergies? Do they have microchips in them? – because the point of the study is vaccines, not general conspiracy theories. It occurred to me, though, that there’s something in between the very general (conspiracies are common) and the very specific (they’re putting microchips in vaccines). That something is relatively vague suspicion about a particular topic – “there’s something fishy about vaccines” or “they’re not telling us the truth about 9/11” or “the Jews are up to something.”

Of course it’s a pyramid.

What I propose in the paper is a three-level model. Conspiracy mentality is at the top: your opinion on whether the world is a conspiratorial place pretty much governs how you think about conspiracies in general. It’s influenced by your personality and a variety of other individual-difference variables. The next level is suspicion about particular groups or topics. That’s influenced by the top level, of course, and each suspicion has its own influences – your left-right orientation might determine whether you think there’s something awfully suspicious about Barack Obama’s history, for instance. Alternatively, you might distrust a specific person or group, so you’re suspicious about things they’re involved in. The bottom level is beliefs in specific theories. Your opinion on theories that Obama was born in Kenya will be influenced by your suspicions about his history, but so will your opinion of the conspiracy theory that his years at Columbia University were fabricated, that he was never really involved with the things at Harvard he claimed to have done, and so on. Those individual theories aren’t that important – they sometimes might contradict one another, and you could still find them plausible because they all stem from a common suspicion.

So that’s what the FICS is for – measuring that middle level of suspicion. I think a lot of the time, when psychologists measure beliefs in specific conspiracy theories, suspicion is really what we’re interested in. We don’t care specifically about whether someone thinks that vaccines cause autism versus cause allergies versus contain microchips: we’re interested in the general suspicion that those theories reflect.

*One of the findings was that the FICS doesn’t work for climate change, because it captures very conflicting conspiracy theories – “climate change is a hoax,” and “oil interests are conspiring to make people believe that climate change is a hoax.” Unlike many contradictory conspiracy theories about the same thing, these don’t tend to be correlated positively, because they don’t really share any common assumptions – it may also be relevant that the second theory is really a meta-conspiracy-theory, that the first conspiracy theory is itself the result of a conspiracy.

Tagged: 9/11, measurement, methodology, suspicion

August 8, 2016

Exposure to conspiracy theories: Enduring over a two-week period

We know that conspiracy theories may have some important negative societal consequences. Conspiracy theories can discourage people from engaging with the political system, taking action against climate change and having a fictional child vaccinated.

In each of these empirical investigations, participants were exposed to conspiracy theories, before being asked to immediately complete several questionnaires – such as their intention to vaccinate a fictional child after they had been exposed to anti-vaccine conspiracy theories. An intriguing question remained, however: How long do these effects persist for?

Recent research published in the International Journal of Communication has provided some answers to this. The scholars found that after exposure to a video promoting government conspiracy theories about the moon landing (segment taken from Conspiracy Theory: Did We Land on the Moon), belief in conspiracy theories increased immediately after the exposure and two weeks later (when compared to people who had not watched the video).

This provides, to my knowledge, the first empirical evidence that being exposed to conspiracy theories can change your attitudes for a prolonged (two-week) period of time. If you are interested in reading the paper, you can access a PDF copy here.

As a scholar examining the social consequences of conspiracy theories, I find this research particularly intriguing as the research provides evidence that conspiracy theories may indeed endure for a longer period of time than the experimental session. There are however still unanswered questions, such as whether being exposed to conspiracy theories would also change behaviours over a period of time, and of course, whether the effect persists after two-week. Yet, this empirical investigation adds to our understanding and highlights the importance of further investigations into the psychology of conspiracy theories.

June 21, 2016

Conspiracy theories and the campaign to Leave the EU

With colleagues at the University of Kent (Prof Karen Douglas and Dr Aleksandra Cichocka), we have written a piece in The Psychologist discussing conspiracy theories and the campaign to Leave the EU. In short, we have found that belief in such conspiracy theories predicts the extent to which people believe that Britain should remain part of the EU.

Here is an excerpt from the piece:

Very few, if any, conspiracy theories are being promoted by the Remain campaign. This is somewhat unsurprising as conspiracy theories, politically, are generally found in the realm of the right and not the left. But what may be surprising to some is our finding that these conspiracy theories may influence people’s opinions about Britain’s place in the EU above and beyond factors that typically influence people’s political decisions. Will conspiracy theories continue to hold this power come Thursday 23rd June?

Click here to read the piece in The Psychologists.

June 11, 2016

The psychology of gang stalking, and the difference between conspiracy theory and delusion

If you’ve spent enough time on the Internet (or read the New York Times yesterday), you might have come across the phenomenon of gang stalking – the alleged stalking of particular individuals by organized groups. It might seem like gang stalking is a sort of conspiracy theory, and that we can maybe understand it in the same way that we think about things like the 9/11 Truth Movement and beliefs in UFO coverups. I’m not sure about this. There are some pretty major psychological differences between the two. It’s probably not helpful to conflate run-of-the-mill conspiracy theories, which are not considered to be an indicator of psychopathology, with gang stalking, which is widely considered to be the product of delusional thinking.

In gang stalking, large gangs of perpetrators will (allegedly) use subtle methods of manipulation and harassment – muttering hurtful phrases or insults while passing their target on the street, repeatedly driving past the target’s house, preventing them from sleeping by making loud noises at odd hours, and so on. Many people who claim to be victims of gang stalking (search YouTube for a reasonably representative sample) allege more exotic stalking methods – in particular, “electronic harassment,” the use of advanced technology to torture, annoy, or even control the mind of the target from afar.

If you think this sounds pretty far-fetched, you’re not wrong. Stalking is real, of course – there’s no denying that. And there are situations where multiple people participate in bullying or even stalking – often close friends or family members. But “gang stalking” – the type that involves muttered insults, dozens of strangers working together, electronic harrassment, secret hand signals – is not really an accepted thing. In fact, suspicions of gang stalking are considered to be markers of delusional disorders like paranoid schizophrenia. In a 2015 study, Sheridan and James examined 128 reports of group (gang) stalking in an online questionnaire and found that all of them – every single one – exhibited delusional qualities.

From an examination of free-text responses, all 128 group-stalked cases fell into one or more of three categories:

cases where the resources or elaborate organisation required to carry them out made the alleged activities highly improbable (e.g. hostile operatives being inserted in victim’s workplace and their children’s schools; 24-h electronic surveillance involving teams of men in black vans; surveillance by cameras placed throughout the city; staff of shops and libraries being amongst the group stalkers; everyone in the street being ‘plants’ acting out roles towards the victim; ‘more than a thousand’ people being involved; traffic lights being manipulated always to go red on approach; repeated sexual assault during sleep; horns on the street hooting to bring attention to particular sentences on the radio; collaboration between diverse agencies, such as the Automobile Association, a building society, a website and neighbours),

cases in which the activities described were impossible (e.g. minds of friends and family being externally controlled; use of ‘voice to skull’ messages; witchcraft focussed through gold objects; insertion of alien thoughts; organised electronic mind interference; remote removal of bank notes through electronic attraction; invasion of an individual’s dreams at night), and

cases where the beliefs were not only impossible, but bizarre (e.g. docile family dog replaced by exact double with foul temper; remote enlargement of bodily organs).

Gang stalking victim advocates maintain that any resemblance to psychosis is either coincidental, or the result of the very real harassment itself – that the sophisticated influencing technologies can mimic the symptoms of schizophrenia by inducing hallucinations, paranoid thinking, and so on.

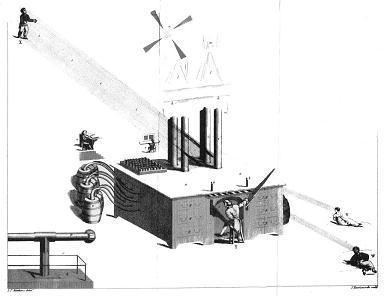

Yet the “influencing-machine” delusion is a common enough one, with a long history. While 21st-century delusions involve mind manipulation via satellites, nanotechnology, and neuroscience, delusions during the Industrial Revolution involved that era’s high technology: the loom. The first known (or at least strongly suspected) case of paranoid schizophrenia, that of James Tilly Matthews in the late 18th century, involved persecution via a mind-control machine called the “Air Loom,” which allegedly controlled its targets’ thoughts and behaviour through the careful manipulation of magnetic fluids.

The Air Loom, with its operator and targets.

At first glance, gang stalking seems like a conspiracy theory: a group of powerful individuals come together in secret to carry out a sinister and deceptive plan. And under that definition, it is. But even beyond the involvement of mental illness, there’s a crucial difference between delusions of persecution (like gang stalking) and conspiracy theories. In most conspiracy theories, the victim of the deception is usually a relatively large social group: Christians, men, African-Americans, the general public, taxpayers. Conspiracy theories are stories about one group trying to outmaneuver another. In persecutory delusions, the target is the self. While conspiracy theories say “they’re out to get US,” persecutory delusions say “they’re out to get ME.”

But for all the psychological differences between gang stalking and the rest of the conspiracy world, there is some crossover between them. Gang stalking proponents seem to have provided some of the raw material for more mainstream conspiracy theories – perhaps thanks to the efforts of gang stalking victim advocacy groups, the references to electronic harassment and mind control that pop up after mass shootings often adopt some of the language of the gang stalking subculture. There’s an interesting (though not, to my knowledge, very well-supported) hypothesis that psychoses like schizophrenia serve an important function in traditional cultures and in the evolutionary history of humanity: they provide a connection to a world other than our own, enrich us with insights that we wouldn’t otherwise have had, and give us ideas about how the world might work beyond what we can see. Maybe “targeted individuals” and other sufferers of delusional disorders serve a similar function in the world of conspiracy, providing raw material for speculation in the form of almost-spiritual insights into a world of power, evil, and high technology that goes beyond what the rest of us can grasp.

Tagged: conspiracy theories, gang stalking, psychology

June 6, 2016

The great Columbia conspiracy: Why Trump and others seem to contradict themselves on Obama’s past

Photo credit: Matt A. Johnson (flickr)

So, I suppose we should talk about Donald Trump at some point. Trump might just be the most famous conspiracy-monger in the world at the moment. He’s flirted with, if not outright endorsed, a wide variety of conspiracy theories, ranging from run-of-the-mill birtherism to old-school Clinton Death List claims to the new hotness that is the vaccine-autism connection.

A few people have noticed that Trump seems to buy into an odd combination of theories about Obama’s time at Columbia University. Officially, Obama attended Columbia from 1981 to 1983 as a transfer student from Occidental College in California; after graduating he went on to study law at Harvard. Since 2008, people (mostly on the right) have raised doubts about Obama’s time at Columbia – they’ve speculated that he was admitted as a foreign student, proving he wasn’t born in America; that he had awful grades and only got through university because of affirmative action policies; that he was turned into a Marxist Manchurian candidate by the constant barrage of radical leftist teaching; or even that he never attended Columbia at all. The official story is a carefully constructed lie, meant to cover up the sinister truth.

You’ll notice that these theories – bad student Obama, foreign student Obama, indoctrinated student Obama, non-student Obama – are not all compatible with one another. Maybe he was a foreign student with bad grades, but it’s not possible that Obama got bad grades at a university he was never a student at, or that he wasn’t admitted, but was also admitted as a foreign student, or never attended lectures at Columbia, but was radicalized by the left-wing lectures. But, somehow, every so often you see the contradictory theories being pushed by the same people. Trump’s friend and supporter, Wayne Allyn Root, seems to have provided the raw material for a lot of these theories: he thinks that Obama might have been registered at Columbia, but certainly never attended classes, but was also brainwashed by those classes. Trump suggests that Obama never went to Columbia – he “came out of nowhere” and none of his classmates remember him – but also finds it likely that his records from Columbia would show a foreign birthplace, if they haven’t been deleted. In a baffling tweet (even by Trump standards) he urged the hackers of the world, as long as they’re going around hacking stuff, to find out more.

This fits into an established psychological pattern. In a study published in 2012, my colleagues and I showed that there tend to be positive correlations between beliefs in contradictory conspiracy theories. The more someone believes that Osama Bin Laden was dead long before 2011, the more they believe that he was still alive after the media pronounced him dead that year. The more someone believes that Princess Diana was killed by business enemies of Dodi Fayed’s family, the more they believe she was killed by the British secret service. And, probably, the more someone believes that Obama was never admitted to Columbia, the more they believe that he was admitted there as a foreign student.

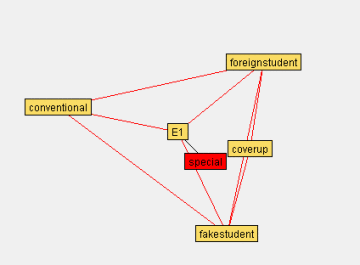

Why is this? Is it because people who buy into conspiracy theories are dumb and crazy? No, almost certainly not. It’s because the conspiracy theories are usually pretty vague and are based more on general suspicion than on specific evidence. If you’re suspicious that something is going on and that the truth is being covered up, then many different (and perhaps contradictory) alternatives will seem more likely. You can see this pattern arise in computational models of belief consistency. ECHO, an excellent model by Paul Thagard, showcases this very well. We can use ECHO to construct a belief network made up of various propositions and bits of evidence that support or contradict one another; the network will then decide on the basis of those relationships which proposition or propositions seem most likely. Research has shown that ECHO does a pretty good job of predicting the outcomes of jury trials and scientific controversies. We can use ECHO here by constructing a simplified network to represent the Obama/Columbia question. For the purposes of the model we’ll assume that there are three mutually contradictory theories, all of which explain the evidence equally well. However, we’ll add “suspicion of a coverup” as something that links with and supports both conspiracy theories.

CONVENTIONAL EXPLANATION: Obama went to Columbia as a domestic student. (explains the evidence; contradicts both conspiracy theories)

FAKE STUDENT THEORY: Obama never went to Columbia; the whole thing is a lie. (explains the evidence; contradicts foreign student theory and conventional explanation)

FOREIGN STUDENT THEORY: Obama went to Columbia but was registered as a foreign student. (explains the evidence; contradicts fake student theory and conventional explanation)

COVERUP SUSPICION: Obama’s covering up something to do with his college years. (explains both fake and foreign student theories)

Head over to the site hosting a web-based ECHO applet (if you can deal with the Java warnings), and paste the following code into the right box:

data(E1) //There is some evidence

explain((conventional),E1) //Conventional theory explains the evidence

explain((fakestudent),E1) //Fake theory explains the evidence

explain((foreignstudent),E1) //Foreign theory explains the evidence

explain((coverup),fakestudent) //Coverup suspicion agrees with fake theory

explain((coverup),foreignstudent) //Coverup suspicion agrees with foreign theory

contradict(fakestudent,foreignstudent) //Two CTs contradict each other

contradict(fakestudent,conventional) //Fake theory contradicts conventional

contradict(foreignstudent,conventional) //Foreign theory contradicts conventional

A JavaECHO simulation of the Columbia question. The distance of the conventional explanation from the Special node indicates that it has been rejected by the model.

Now, hit Run – see what happens? The resulting weights show that both conspiracy theories are accepted despite the fact that they contradict one another, because they both have an underlying suspicion supporting them. Networks with more lopsided evidence might favour one conspiracy theory over another, but usually, if that suspicion is there, both conspiracy theories will still seem more likely than the conventional explanation. This demonstrates that even beliefs in contradictory theories can turn out to be correlated with one another.

If you read the links from earlier in the post, you might notice that piecing together who said what is difficult. A lot of these ideas, whether they come from Trump, Root, Breitbart, or elsewhere, are phrased as innuendo or “just asking questions.” There’s some deniability there. Root, for his part, now says he never claimed Obama wasn’t registered at Columbia or didn’t graduate (though he’s a poor writer if that’s not what he was getting at). I don’t think this vagueness is completely a rhetorical tactic, though- I think it reflects a genuine uncertainty about what’s going on. People don’t often commit to a hyper-specific version of some conspiracy theory. More often than not, the suspicion is all there is.

Tagged: conspiracy theories, obama, psychology, trump, USA

May 26, 2016

Are You Serious?

I’ve posted here before about why measuring belief in conspiracy theories can be tricky. Recently I was invited to visit University of Cambridge’s Conspiracy and Democracy project and the issue of measuring belief came up again, particularly the question of what it means when somebody indicates on a survey that they “believe” (or don’t “believe”) a conspiracist claim. I wrote a blog post for the Conspiracy and Democracy project about the idea, which I’m reposting in full below. You can also watch the full public talk I gave at Cambridge at the bottom of this post.

I’ve posted here before about why measuring belief in conspiracy theories can be tricky. Recently I was invited to visit University of Cambridge’s Conspiracy and Democracy project and the issue of measuring belief came up again, particularly the question of what it means when somebody indicates on a survey that they “believe” (or don’t “believe”) a conspiracist claim. I wrote a blog post for the Conspiracy and Democracy project about the idea, which I’m reposting in full below. You can also watch the full public talk I gave at Cambridge at the bottom of this post.

Psychologists love to measure things, and psychologists who study conspiracy theories are no exception. To understand where conspiracy theories come from, we need to be able to measure the extent to which people believe them. But measuring things is often trickier than it first appears.

At first glance, it seems pretty straight-forward. Pick a few theories and ask some people how strongly they believe the claims to be true or false. But the trouble is that different teams of researchers often ask about different theories, or ask about the same theories in different ways, so their scales might not be directly comparable. Plus, a scale item referring to the London 7/7 bombings, say, might not be ideal for non-British samples. Plus, conspiracy theories go in and out of fashion, potentially resulting in a scale that no longer works very well. An item from a 1994 study carried out in the States, for example, asks whether “The Japanese are deliberately conspiring to destroy the American economy.” (At the time, almost half of the sample–46%–said the theory was either definitely or probably true.)

In an effort to overcome these problems, colleagues at Goldsmiths and I created a measure of generic conspiracism. Our scale doesn’t refer to any specific conspiracist claim (like the allegation that the 9/11 attacks were an inside job), but instead asks about the generic assumptions that underlie the theories (like the idea that governments routinely harm and deceive their own citizens).

This is an improvement, but we’re still left with another problem, and this one is trickier to solve. We’re asking people how much they believe (or disbelieve) conspiracist claims, but what exactly does it mean when someone says they believe something like that? Does it mean they literally believe it to be true? Or might they believe it in a metaphorical sense? Might they not believe it, but tell us they do because they want to appear funny or ironic or unconventional? Might they be making a political statement? Or might they not be concerned about the truth at all? Measures of conspiracism might mean different things to different people.

This issue was pointed out by Conspiracy and Democracy project-member Alfred Moore in his response to my public talk for the project, and I agree wholeheartedly that it is an important issue for future psychological research to deal with.

It is also an issue which highlights the need for an interdisciplinary approach to conspiracy theories. In particular, history and political science–two of the major approaches of the Conspiracy and Democracy project–can be particularly valuable.

A historical approach can give us a fine-grained understanding of what people actually believe, at least on the scale of individuals. If a historian comes across a letter written by an well-known conspiracist in which they admit that they don’t actually believe a word of it, that’s a good indication that the person’s publicly stated views do not match their privately held beliefs.

Political scientists, like psychologists, are usually more interested in broad trends rather than specific individuals, and often rely on survey data. In an effort to make sure people’s responses reflect their actual beliefs, some political scientists have found a way to make people put their money where their mouth is. People’s answers to political questions, like the size of the federal deficit, are often biased by their partisan affiliation, but offering people cash for accurate answers can significantly reduce their partisan bias.

Of course, while monetary incentives might make people more accurate when answering questions that have a known answer, conspiracy theories don’t always have an objectively correct answer. The challenge will be figuring out if a similar honesty system can be put to use in the context of conspiracy theories.

Tagged: beliefs, conspiracy theories, measurement, personality, politics, psychology

May 22, 2016

Intention Seekers: The Psychology of Conspiracy Theories About MS804

I wrote a post over at Psychology Today on the psychology behind conspiracy theories about airline disasters like the disappearance of MH370, and more recently, MS804. Part of the appeal, according to a handful of recent studies, may be how conspiracy theories resonate with our brain’s intentionality bias.

When ambiguous events happen, we automatically assume that they were intended, rather than accidental. The bias is easy to spot in kids. When young children see somebody sneeze of fall over, they think that the person must have meant to sneeze or fall over. As we grow older, of course, we realize that people don’t always intend to do everything they do, and we can override our automatic judgment of intent. But the bias stays with us. One study found that having people drink a few shots of alcohol made them more likely to interpret ambiguous events as intentional—which might explain why so many fights start in bars when somebody interprets an innocent comment as an aggressive affront.

To read more about how this helps us understand conspiracy theories, click over to Psychology Today.

Tagged: conspiracy theories, current events, Egyptair MS804, Malaysia Airlines MH370, politics, psychology

May 13, 2016

Stress and belief in conspiracy theories

A recent a piece of research published by Viren Swami and colleagues has uncovered a link between feeling stressed and belief in conspiracy theories.

Swami and colleagues gathered responses from over 400 people, where the responders completed various measures, such as indicating their perceived stress (over the last month), stressful life events (over last 6 months) and belief in conspiracy theories. They found that more stressful life events and greater perceived stress predicted belief in conspiracy theories.

There are a couple of reasons proposed why this may be the case. For example, when people experience stress (say a stressful life event), they may start thinking in a particular way such as seeing patterns when they do not exist, which may lead on to prompting a conspiratorial mind set. Once this worldview has begun to develop therefore, belief in conspiracy theories are more easily reinforced.

Alternatively, the researchers suggest stress may not be the central driving force, but rather, the findings may be caused by a threat to a sense of control. When an event happens; the death of JFK as an example, this causes people to feel a sense powerlessness, thus people may seek out conspiracy theories as a way to reinstall a sense of control. The next step in the research is to examine the complex relationships between stress, control and belief in conspiracy theories in order to tease apart the mechanisms.

Investigating the associations between beliefs in conspiracy theories and factors such as stress is an important avenue of research. From my own work, we have highlighted the potential negative consequences of belief in, and exposure to, conspiracy theories. It is therefore paramount that we strive to learn more about the psychology of conspiracy theories.

Of course conspiracy theories may offer several benefits. They can be a way to gain a sense of control as suggested and can be said to promote transparency within authorities. Conspiracy theories can also reduce the likelihood of people voting, taking action against climate change, and having a fictional child vaccinated. In some of my most recent work, conspiracy theories can be used as a way to express negativity, alongside changing how we perceive other social groups.

As highlighted by Swami and colleagues therefore, examining belief in conspiracy theories remains an urgent issue for researchers and policy-makers.

Tagged: conspiracy theories, psychology, social psychology

Rob Brotherton's Blog

- Rob Brotherton's profile

- 22 followers