What suspicion tells us about beliefs in conspiracy theories

Have a look at the statements below, and think about how much you agree with each of them on a 1-5 scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

The real truth about 9/11 is being kept from the public.

People need to wake up and start asking questions about 9/11.

Legitimate questions about 9/11 are being suppressed by the government, the media, and academia.

Reporters, scientists, and government officials are involved in a conspiracy to cover up important information about 9/11.

An impartial, independent investigation of 9/11 would show once and for all that we’ve been lied to on a massive scale.

Add up your scores, and you have a measure of how suspicious you are that there’s some kind of ongoing conspiracy surrounding 9/11. Now, do the same with these statements.

The real truth about the moon landings is being kept from the public.

People need to wake up and start asking questions about the moon landings.

Legitimate questions about the moon landings are being suppressed by the government, the media, and academia.

Reporters, scientists, and government officials are involved in a conspiracy to cover up important information about the moon landings.

An impartial, independent investigation of the moon landings would show once and for all that we’ve been lied to on a massive scale.

That looks familiar! This is called the FICS – the Flexible Inventory of Conspiracy Suspicions. It’s a sort of fill-in-the-blanks, conspiracy theory Mad Libs thing – a new innovation in measuring conspiracy theory beliefs. You can put nearly* any topic of public interest in there, and end up with a valid measure of suspicions that there’s a conspiracy to do with it. I’ve written an article proposing and validating this approach, and was fortunate enough to have it accepted to the British Journal of Psychology. It went up on Early View this week, so you can check it out if you have access to the journal. More info about it after the jump – including how this tells us something about the way that conspiracy beliefs are structured.

We know that people’s opinions on conspiracy theories tend to hang together. Conspiracy theories are something that people tend to be generally into or not, to varying degrees. If you ask someone for their opinion on whether 9/11 was an inside job, you can use that information to predict (pretty accurately) what they think about whether Princess Diana was assassinated, whether the moon landing was faked, and whether the media is programming us with subliminal mind control. Current thought says this is because people’s worldviews are more or less “conspiracist” – that is, people have a general opinion on how common conspiracies are, the degree to which powerful people tend to conspire against the common good, how easy it is to cover up conspiracies, and so on. You can measure this tendency with questionnaires like Rob’s Generic Conspiracist Beliefs Scale, or Bruder et al.’s Conspiracy Mentality Questionnaire. People who score high on these scales tend to believe a lot of conspiracy theories; people who score low tend to believe relatively few.

Often psychologists are interested in general conspiracy mentality, but will still ask about specific theories, because they’re interested in specific topics. Dan’s study of vaccine theories asked about a laundry list of specific dangers of vaccines – do they cause allergies? Do they have microchips in them? – because the point of the study is vaccines, not general conspiracy theories. It occurred to me, though, that there’s something in between the very general (conspiracies are common) and the very specific (they’re putting microchips in vaccines). That something is relatively vague suspicion about a particular topic – “there’s something fishy about vaccines” or “they’re not telling us the truth about 9/11” or “the Jews are up to something.”

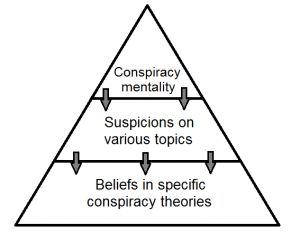

Of course it’s a pyramid.

What I propose in the paper is a three-level model. Conspiracy mentality is at the top: your opinion on whether the world is a conspiratorial place pretty much governs how you think about conspiracies in general. It’s influenced by your personality and a variety of other individual-difference variables. The next level is suspicion about particular groups or topics. That’s influenced by the top level, of course, and each suspicion has its own influences – your left-right orientation might determine whether you think there’s something awfully suspicious about Barack Obama’s history, for instance. Alternatively, you might distrust a specific person or group, so you’re suspicious about things they’re involved in. The bottom level is beliefs in specific theories. Your opinion on theories that Obama was born in Kenya will be influenced by your suspicions about his history, but so will your opinion of the conspiracy theory that his years at Columbia University were fabricated, that he was never really involved with the things at Harvard he claimed to have done, and so on. Those individual theories aren’t that important – they sometimes might contradict one another, and you could still find them plausible because they all stem from a common suspicion.

So that’s what the FICS is for – measuring that middle level of suspicion. I think a lot of the time, when psychologists measure beliefs in specific conspiracy theories, suspicion is really what we’re interested in. We don’t care specifically about whether someone thinks that vaccines cause autism versus cause allergies versus contain microchips: we’re interested in the general suspicion that those theories reflect.

*One of the findings was that the FICS doesn’t work for climate change, because it captures very conflicting conspiracy theories – “climate change is a hoax,” and “oil interests are conspiring to make people believe that climate change is a hoax.” Unlike many contradictory conspiracy theories about the same thing, these don’t tend to be correlated positively, because they don’t really share any common assumptions – it may also be relevant that the second theory is really a meta-conspiracy-theory, that the first conspiracy theory is itself the result of a conspiracy.

Tagged: 9/11, measurement, methodology, suspicion

Rob Brotherton's Blog

- Rob Brotherton's profile

- 22 followers