Rob Brotherton's Blog, page 2

December 19, 2019

If others are conspiring, then why should I be well-behaved?

by Daniel Jolley, Karen Douglas, Ana Leite, and Tanya Schrader

[image error]

We live in a complex world. To navigate this complexity, we often look to other people to decide what we should believe and how we should behave. But what happens if those “others” are perceived to be involved in shady plots and schemes? That is, what if we think they are engaged in conspiracies? Will we still rely on them to infer what sort of beliefs and behaviours are acceptable?

This question is important because conspiracy theories are popular. For example, around 60% of British people believe in at least one conspiracy theory. Well-known conspiracy theories blame governments, scientists, and many others for problems as diverse as terrorists acts, deaths of important people, plane crashes, and New Coke (which is not so new anymore). If we believe that other people do these sorts of things, this might alter our perceptions of social norms—what is expected from us—and signal that unethical behaviours are acceptable, particularly if those “others” are powerful groups with influence.

In our research, we set out to test this idea. Our first study showed that people who were more likely to believe in conspiracy theories were also more likely to report that they had engaged in everyday crimes such as trying to collect refunds or compensation from a store when they were not entitled to do so. Beliefs in conspiracy theories predicted everyday criminal behaviour, even when other predictors of criminal behaviour, such as personality traits reflecting people’s moral conscience, were taken into account.

In a second study, we tested whether reading about conspiracy theories increases the degree to which people accept everyday crime. Participants read an article about alleged government involvement in conspiracies, including the death of Diana, Princess of Wales. Exposure to conspiracy theories increased people’s intentions to engage in everyday crime in the future. If the government is corrupt, why shouldn’t I be?

You can read the full post at Character and Context.

July 20, 2019

50 years today – 20th July 1969 – we landed on the Moon. Or, did we?

Popular conspiracy theories propose the moon landing was a hoax and the footage recorded in a Hollywood studio. An explanation for why could be that at the time, the Americans had not yet developed a safe way to get a person on the moon – as promised – so they faked it! On the approach to the 50th anniversary, I have been invited to speak about this conspiracy theory, so I thought I’d pen a short blog post on the topic.

[image error]

Conspiracy theories are popular, with 12% of British people believing that the moon landing was faked. But, why do people believe in conspiracy theories?

The moon landing conspiracy theories showcase a tale of mistrust of information; a mistrust towards those with power – whether this is the government or NASA. This mistrust can increase the credibility of conspiracy theory accounts, as these accounts support a persons’ worldview. Indeed, conspiracy theories breed when the conspiracy account fits with the prior held beliefs or the way that a person sees the world (often referred to as motivated reasoning) – simply if a person believes powerful groups act in secret, where they are involved in plots and schemes, this will likely breed conspiratorial thinking to a range of events, including the moon landing.

However, simple exposure can also increase people’s belief in conspiracy theories. Researchers found that after exposure to a video promoting government conspiracy theories about the moon landing (segment taken from Conspiracy Theory: Did We Land on the Moon), belief in conspiracy theories increased immediately after the exposure and reminded heightened two weeks later (when compared to people who had not watched the video). It is plausible that the influence will be stronger if the conspiracy fits your prior belief; but nonetheless, this research demonstrates the potential impact of simple exposure to conspiracy theories.

People also have a desire to search for knowledge and find the truth – however, research has shown that people who are low in analytical thinking (and instead rely on intuitive thinking) are more likely to subscribe to conspiracy theories. In other words, people may have the desire to be rationale and seek knowledge, however, they may rely more on intuition rather than critical evaluation (see here for a discussion). This process could also be clouded by how they see the world; their motivated reasoning as uncovered earlier.

In insolation, believing that the moon landing conspiracy theory is a hoax may have limited consequences; however, we know that people who believe in one conspiracy are very likely to subscribe to multiple conspiracy theories. The belief in the moon landing conspiracy may go on to promote the belief that other events have been faked – such as the Sandy hook shooting in America as discussed by Peter Knight. This could become worrying because conspiracy theories have been linked to violent tendencies – for example, a link has been demonstrated between people endorsing conspiracy beliefs and accepting violence towards the government.

Did we land on the moon? Our beliefs about the world and ability to think analytically (rather than rely on our intuition) will likely play a role in our response to that question.

**

You can listen to recent interviews I have given to BBC Radio Sussex and Stoke. Other scholars have written and commented as part of an excellent series on the moon landings in the Conversation.

I’m also part of a panel discussing moon landing conspiracy theorists at the Science Museum at the end of July 2019 (£).

March 14, 2019

Conspiracy theories fuel prejudice towards minority groups

By Daniel Jolley and Karen Douglas

Some 60% of British people believe in at least one conspiracy theory, a recent poll reveals. From the idea that 9/11 was an inside job to the notion that climate change is a hoax, conspiracy theories divert attention away from the facts in favour of plots and schemes involving powerful and secret groups. With the aid of modern technology, conspiracy theories have found a natural home online.

Conspiracy theories often unfairly and erroneously accuse minority groups of doing bad things. For example, one conspiracy theory accuses Jewish people of plotting to run the world, including the outlandish idea that Jewish billionaire George Soros is a mastermind of a vast global conspiracy to “reduce humanity to slavery”. Another conspiracy theory proposes that global warming was created by the Chinese in order to make US manufacturing non-competitive. Yet another conspiracy theory accuses immigrants of plotting to attack Britain from within.

In our research, we wanted to look at the impact of these types of conspiracy theories. How do they actually make people feel about minority groups? In our new paper, published in the British Journal of Psychology, we try to answer this question based on the results of three experiments.

Read the full piece on The Conversation: https://theconversation.com/conspiracy-theories-fuel-prejudice-towards-minority-groups-113508

February 26, 2019

New research shows a link between belief in conspiracy theories and everyday criminal activity

In a new paper published in the British Journal of Social Psychology, we have found that people who believe in conspiracy theories – such as the theory that Princess Diana was murdered by the British establishment – are more likely to accept or engage in everyday criminal activity.

[image error]

In our first study, the findings indicated that people who believed in conspiracy theories were more accepting of everyday crime, such as trying to claim for replacement items, refunds or compensation from a shop when they were not entitled to do so.

In a second study, we found that exposure to conspiracy theories made people more likely to intend to engage in everyday crime in the future. We found that this tendency was directly linked to an individual’s feeling of a lack of social cohesion or shared values, known as ‘anomie’.

In summary, our research has shown for the first time the role that conspiracy theories can play in determining an individual’s attitude to everyday crime. Specifically, we found that that belief in conspiracy theories, previously associated with prejudice, political disengagement and environmental inaction, also makes people more inclined to actively engage in antisocial behaviour. It demonstrates that people subscribing to the view that others have conspired might be more inclined toward unethical actions.

You can find out more about the psychology of conspiracy theories on YouTube:

November 11, 2018

Cartoon on the psychology of conspiracy theories

In June 2018, I was voted one of the winners of ‘I’m a Scientist’ – which is an online platform to engage school children in science where across a two-week period, I spoke to children of all ages about why people believe in conspiracy theories. On being voted a winner, I was awarded funding for public engagement activities.

I am passionate about science communication where I regularly give public talks. To try something different, I sought out artists from More than Minutes and gave them the task to draw what we know so far about the psychology of conspiracy theories. The artists listened to me give a lecture where I discussed what is a conspiracy theory, why do people believe in conspiracy theories and what is the potential harm; before they spent the afternoon drawing the research.

[image error]

I have turned the drawing into a video, where I provide a narration to bring to life the piece. You can find this on YouTube.

With thanks to More than Minutes for drawing the research, alongside the support from I’m a Scientist and the British Psychological Society.

You can download the drawing here.

April 15, 2018

Internet prophecy cults 101: QAnon and his predecessors

FROM: mike@conspiracypsych.com

TO: operations@soros.org

SUBJECT: Re: advice pls

Hi George,

Thanks for your email. Flattered that you thought of me – of course I can give you a hand with this. I can see why you want to understand the appeal of QAnon. First, a brief history!

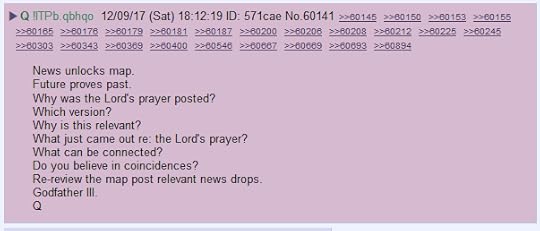

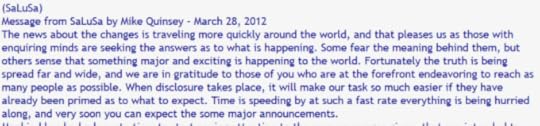

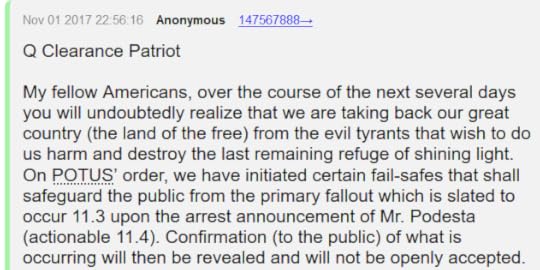

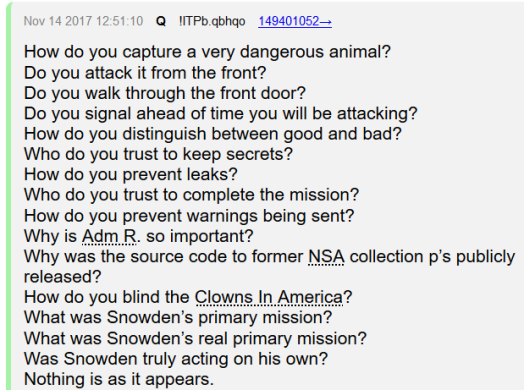

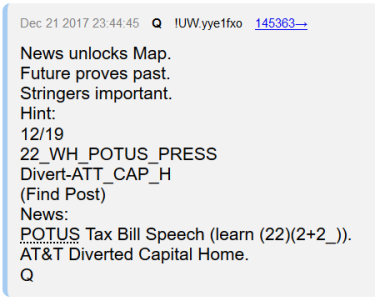

“QAnon”, also known as just plain Q, first appeared in October 2017. At first he was just another “insider” posting cryptic hints about the future of U.S. politics on anonymous messageboards, but he quickly gained a following for his claims that Donald Trump is both a secret genius and the present target of a doomed conspiracy to destroy Western civilization. These days, a flock of conspiracy-minded Trump supporters are following his “drops” – cryptic messages revealing different aspects of the conspiracy.

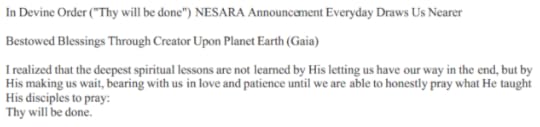

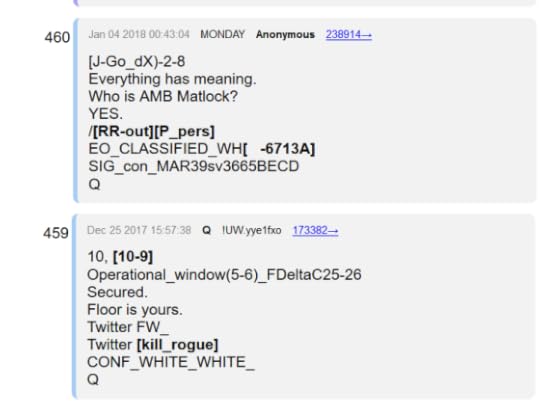

A standard Q post.

Despite being an anonymous shitposter, Q’s got a lot of people convinced that he’s got insider info on the deep state conspiracy against Trump. But you need to understand that this is a much older scam than Q himself. People have been pulling the same thing for decades.

The thing is, Q isn’t just a conspiracy theory. It’s a kind of internet prophecy cult. Never mind that its prophecies are almost entirely wrong when they’re not too vague to make a judgement one way or another.

I’ll answer your question, but I’ll give you a couple of other examples along the way to illustrate how others have managed this in the past. They are:

QAnon, who you already know.

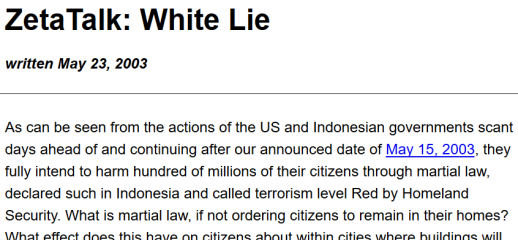

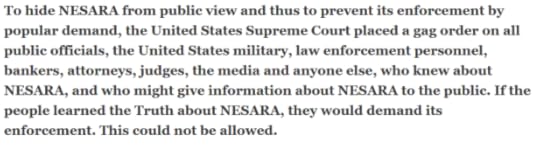

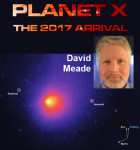

ZetaTalk, a doomsday cult about a rogue planet, “Planet X” or “Nibiru” coming along to flip the rotational poles of the Earth (a fact which is being covered up by the government), run by a woman named Nancy Lieder.

Dorothy Martin, AKA Marian Keech, who ran a similar UFO doomsday cult in the 50s.

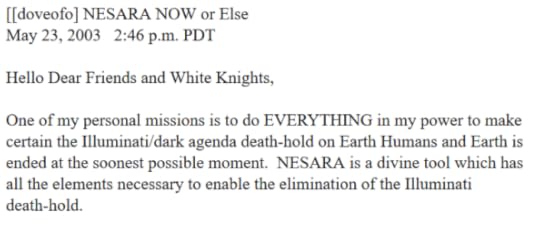

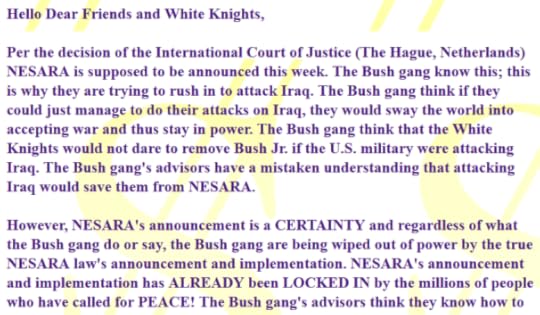

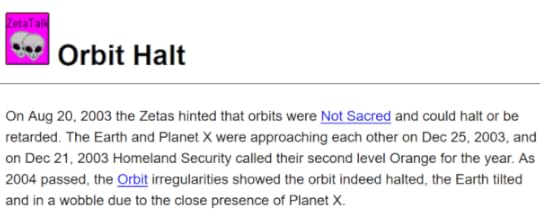

NESARA, which was a scam that started up in the 90s. It’s complicated, but they believed that with the help of space aliens, a secret law called NESARA has been passed that will abolish the current monetary system, and we’ll all be rich as soon as it’s revealed to the public.

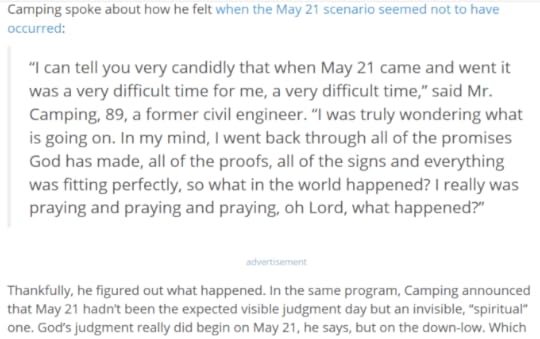

Harold Camping, who predicted the Apocalypse would occur on a couple of dates in 2011.

Psychologically, we have some insight into why this happens – hell, Dorothy Martin’s cult was the subject of “When Prophecy Fails,” one of the foundational texts of social psychology. I’ ll do my best to break down how this works, step by step, using some of that psychology and some of my own observations. As best I can, I’ve tried to accompany each step with some illustrative examples from all of these previous sources (though it’s easier to find Q’s text online – the ZetaTalk website is a mess, NESARA is spread over a billion different 90s websites, etc.).

1. Find an audience, and tell them what they want to hear.

Figure out who you’re appealing to. Preppers? Goldbugs? New Age UFO fans? The new right? Whoever you want to reach, go to where they are. Find their communities and post there. Act mysterious. Tell them that everything they believe is right and good, and everything they disagree with is wrong, evil, and doomed.

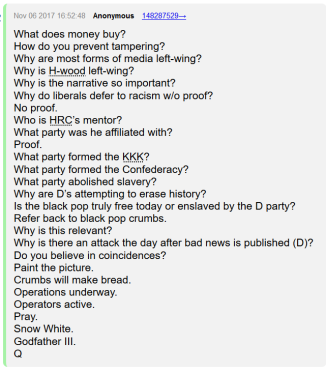

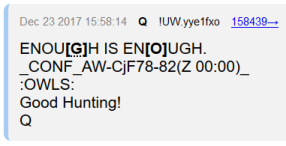

Q telling 4chan’s extremely right-wing politics forum about the evils of the Democratic Party.

Tell them that while things might look bad at the moment, soon a great cleansing will come upon the world. The evil men who have jealously hoarded their power will be swept away, and the world will be ruled by the just. It might hurt, people might die, but in the end, everything will be set right.

[image error]

Q laying out the stakes.

The “Dove of Oneness” – the first NESARA prophet – letting us know how NESARA will save the world.

ZetaTalk describing how the selfish elites of Earth are planning to escape to Mars when the apocalypse comes.

Now that you’ve told them who the bad guys are, tell them who the good guys are. Tailor this to your audience. Aliens are a safe bet if you’re in the New Age crowd. If your audience is a little less UFO-friendly, go with political insiders, patriots, loyalists to the way things ought to be. Give the good guys a name. Maybe go with White Hats, White Knights, something like that.

ZetaTalk’s depiction of the (mostly benevolent) aliens who will help us.

A NESARA post describing the “White Knights” who will end the conspiracy.

A Q post describing the “wizards and warlocks” who, led by Donald Trump, will defeat the Deep State.

Tell them that the White Hats will save us – or help us save ourselves.

Tell them that the White Hats aren’t always visible, but they’re there. They’ve penetrated the ranks of evil, and have been preparing to make their move for a long time. Maybe months, maybe years, maybe centuries. But now the hour of victory is upon them. Soon, very soon, they will make their move and make the world great again.

Q assuring us that the Deep State will be overthrown very soon, and all will be well.

Salusa, one of the NESARA aliens, telling us that everything’s just about to go down.

People will believe you. People always want to believe they’re right. Mostly, they will convince themselves that they’re right anyway, and since you were telling them things they want to be true, they’ll give you credit for having been “right.”

Write strangely. Maybe you’re a telepathic channel for aliens who use weird expressions because they’re not quite human, maybe you’re a secret spy who uses secret spy codes, maybe you’re God so you sound like the King James Bible. They will think this is impressive, or at least they’ll think you sound distinctive and memorable. You’ll stick in their minds. They’ll second-guess themselves because you’re obviously operating on a different level from them.

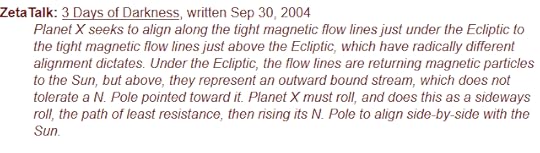

A ZetaTalk message that shows an interesting grasp of orbital mechanics.

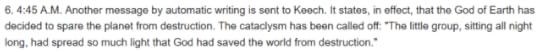

An excerpt from “When Prophecy Fails”, featuring a telepathic message from Sananda (Space Jesus).

One of Q’s “stringer” posts – cryptic nonsense purportedly giving commands or encoded messages to field agents.

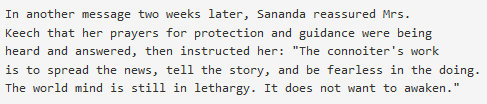

A NESARA post featuring Biblical-sounding language.

Tell them that your predictions are coming true, that the signs of your correctness can be seen everywhere. Tell them that your critics are not really critics – they’re shills, trolls, stooges. Agents of the conspiracy. Tell them that the shills will stop at nothing to prevent the Truth from getting out, to keep people asleep.

An excerpt from “When Prophecy Fails,” detailing how humanity is not yet ready to listen to the cult’s message.

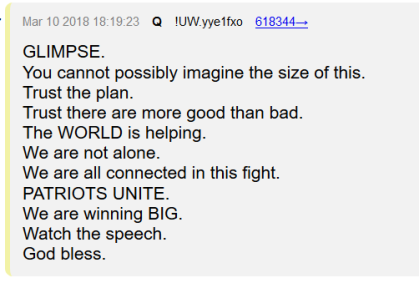

Most of all, tell them that they’re special for believing you. They’re not like the sleeping masses – they are the rare people who can see through the lies. They are good and smart and righteous.

A Q message congratulating its “patriot” readers on their importance and cleverness.

A NESARA message on how important the readers are.

If you’ve told people enough of what they want to hear, they’ll find reasons to believe what you’re telling them. They’ll defend you. That’s how you know you’re ready for the next step.

2. Set a date for when everything will start to happen.

Tell them that the White Hats will make their move (or the apocalypse will come) on a particular date, or in a specific time frame. People like definite predictions. You’ve been pretty general so far, so a specific prediction will stand out, and it’ll get people talking.

Q announcing in early November 2017 that John Podesta’s arrest would be revealed to the public in the following days.

Tell them that this is when everything starts, when the signs will finally be undeniable, when the truth will come out and the evil will start to crumble. Tell them that the world will begin to awaken. Tell them that their enemies will be destroyed, light will prevail over darkness. The world will be wiped clean.

A ZetaTalk post predicting that the “Planet X” catastrophe would come to pass in mid-May, 2003.

One of many NESARA posts assuring the reader that the existence of NESARA would occur that very same week.

What date should you pick? Doesn’t matter. Nothing’s going to happen. This is a publicity stunt. Dates are attractive. Your followers will spread your prediction around, and your critics – shills, remember – will mock it. That’s good. It’s publicity. People who had never heard of you will hear about you. Some of them will be intrigued. Some of them will laugh. Ignore those.

3. Come up with an excuse.

So, the date has passed and nothing has happened. The critics are cackling away, spreading your failure for the world to see. Your supporters are confused and disoriented. It’s time to rationalize. You have a few options.

Maybe you tell them that the prediction was a lie, meant to confuse the conspirators. I wouldn’t recommend this.

A ZetaTalk post explaining that the predicted date for the end of the world was a clever deception meant to scare the conspiracy into tipping their hand.

Maybe you tell them that your efforts have delayed the end. This works best if people are ambivalent about the coming end, if it would come with a cost in lives and suffering. It’s still coming, mind you, just delayed a little. And what feels better than postponing the apocalypse?

In “When Prophecy Fails,” the predicted date of the apocalypse came and went without incident. The cult leader channeled a message from the benevolent aliens saying that the actions of the cult had delayed – but not stopped – the end of the world.

Maybe you tell them that the White Hats went ahead with their plan – they just did it secretly. You see, they worry. They care about us. They don’t want chaos, and panic, and rioting in the streets. They want a gradual transition. They want us to be safe from any counter-moves by the bad guys.

A ZetaTalk post describing the chaos that would result if everyone know about the coming changes.

The law that will change everything that was passed, but everyone was sworn to secrecy.

A post rationalizing why NESARA, supposedly a law that would create world peace and give everyone free money, has passed but is somehow being kept secret.

The alien planet that will purify the Earth has arrived in the inner solar system, but is hidden from view by benevolent aliens while the Earth has stopped in its orbit so the rogue planet can continue to hide behind the sun.

A ZetaTalk post claiming that Earth has stopped in its orbit due to the influence of the mysterious Planet X.

God has passed His judgement on humanity, but hasn’t gotten around to telling anyone.

A news story on Harold Camping, who predicted the apocalypse to begin on May 21, 2011. Here, in an interview after that date, Camping declares that the world was judged by God, though “invisibly.”

The White Hats arrested the conspirators, then set them free on bail so as not to panic the masses.

Q rationalizing why no arrests of conspirators were announced on the original date of 3rd/4th November, 2017.

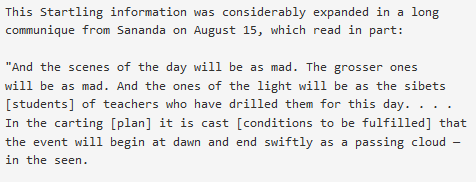

Tell them that despite all this, the signs are still there for anyone with their eyes open. The faithful, the enlightened, the awake – they will be able to see what’s going on. It’s obvious. How could they not see it? Anyone who doesn’t see it must be blind – and when the time comes, they’ll get theirs.

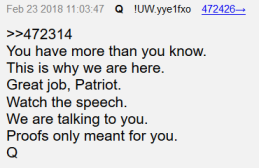

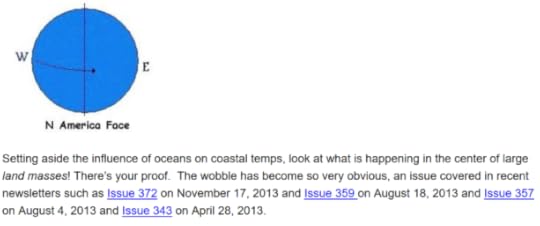

[image error]

Q knows that his followers aren’t like the rest of the sheeple.

A ZetaTalk post, explaining why the “wobble” that is covering up the Earth’s halted orbit is actually really obvious to anyone who’s willing to see it.

Maybe you tell them a combination of all these things. Whatever you choose, it’s best if your supporters do most of the legwork for you. If they defend your rationalization, that’s a good sign. It means that when your predictions conflict with reality, they’ll believe you over their lying eyes.

[image error]

Q’s followers decided that the arrests were actually carried out as predicted (though in secret), and the various conspirators are now wearing ankle monitoring bracelets to track their locations. Here, a Q supporter on Twitter spreads this idea around.

4. Take stock of your following.

At this point, you’ve had your first definite failed prediction. How successful were you? Did your supporters follow you? Did they believe your rationalization? Did they leap to your defence?

A comment thread on a Reddit community devoted to interpreting Q’s prophecies, lamenting that a compromising video of Hillary Clinton hasn’t yet surfaced, as promised by Q.

You got some publicity from the date-setting, but will probably have lost some followers after the failed prediction. These are the people who were probably going to check out anyway at some point. Maybe their worldview wasn’t completely in line with whatever you were pushing, so they didn’t see all of your predictions as self-evident. Who knows?

Two commenters arguing on a different Reddit community about Q’s validity as an insider source.

The end result is condensation. Your remaining followers are now purer, more concentrated, more dedicated to you. To rescue their belief in you they have already chosen to believe in a secret coup d’etat, a concealed apocalypse, an occult constitution. They’re not going anywhere anytime soon.

5. Be vague.

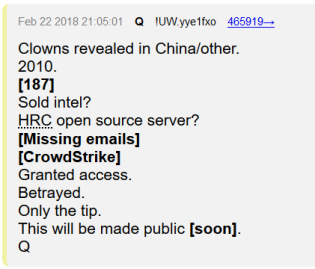

This is your new normal. Tell them things are proceeding as planned. Tell them the White Hats are in control. Tell them it’s only a matter of time until all is revealed.

Q assuring everyone that things are moving along as planned, and all will soon be revealed to the public.

Tell them to look for signs. Tell them that some numbers are significant, that they should look back at certain dates. Tell them generalities. Tell them things that could be seen as true, regardless of what actually happens.

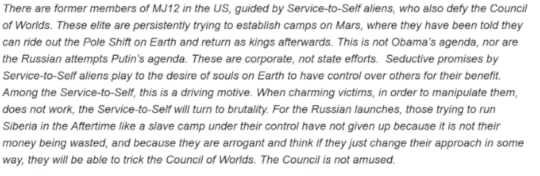

Q posting some cryptic gibberish and “Future proves past”, which is his way of saying that his “predictions” can only be understood after the fact.

Did you tell them to watch someone, or to watch for a particular sign? If the target shows up in the news, that’s confirmation. If not, why isn’t the conspiracy-controlled Mainstream Media reporting on the target? Isn’t that suspicious? Doesn’t that mean you were right, too?

A news story on a NESARA-aligned site alleging a media blackout on pedophilia rings.

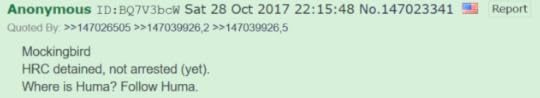

An early Q post urging followers to investigate Democratic Party staffer Huma Abedin, despite her absence from the public eye.

Let them fill in the blanks. Let them watch the news, watch the skies, watch each other. Let them fit current events to your past predictions. If you’re vague enough and put out a high enough volume, there will be some coincidences, some matches, some words you mention that will become relevant days, weeks, or months later. Every one of these random matches is a confirmation of your value and a justification of your followers’ commitment.

[image error]

A compilation of Q posts in which the appearance of the word GREEN in a previous post is interpreted as having predicted a plane crash involving a pilot with the surname Green.

Let them dig themselves deeper. Let them see each other as a united front, a team, a family.

A post by a Q follower describing the sense of pride, accomplishment, and community that he derives from being part of the Q… continuum?

Imitators will appear, trying to ape your success. They’ll give themselves similar names, talk about similar things, but they won’t have the same authenticity, the same originality. Don’t worry about them. By now your followers will dismiss them as part of the conspiracy – more proof that you’re right.

You can disappear, go silent for weeks at a time. Your absence becomes a text for interpretation, just like your writings. Where is the prophet? What mysterious things are they doing?

Q taking a well-deserved Christmas break.

Tell them nonsense. Post gibberish. By now, your followers are experts in the alchemy of their own minds. They will find a way to transmute lead to gold. Have fun! You’ve earned it.

???

Whatever you do, rely on your followers. By now they will do most of the heavy lifting for you, most of the interpretation. When they don’t get what you’re trying to say, it can be frustrating. Try not to seem outwardly annoyed, but it’s not a big deal if you slip up.

Remember your audience. Tell them what they want to hear: they’re special, and everything is about to be great.

Q reassuring the audience.

6. Where are you going with this?

That’s the question, isn’t it?

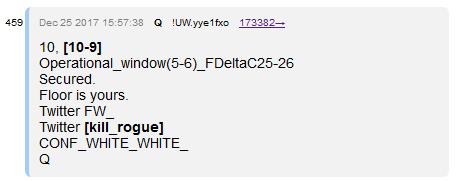

Maybe you want them to give you money. Tell them your expenses are high. Tell them that it’s not easy revealing the secrets of the universe. Tell them you need help. They’ll do it. What’s a few dollars in exchange for the secrets of the universe?

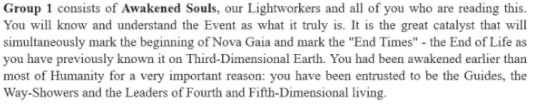

[image error]

A ZetaTalk post soliciting donations to the site.

Maybe you want to build a following to run a pump & dump scheme. Tell them to buy Ethereum or Iraqi Dinars or something, then sell your own stash while the price is inflated.

Maybe you’re not in it for the money, though. Maybe you just want power, or attention, or to change people’s beliefs. Maybe you believe some of what you’re saying. In that case, you might make some more predictions, set some more dates – try to convince more people that what you’re saying is true. Expand the borders. Build an empire of belief. But at this point, that’s optional. You’re there, now. You have a following, a mythology. You’ve arrived.

It’s up to you. The world is your oyster. Enjoy your cult.

—

Anyway, George, that’s how you do it. Give my best to the kids and the Hoggster, and best of luck in Montreal next month.

Your obedient servant,

M. Wood

February 22, 2018

Every mass shooting produces the same conspiracy theories (more or less)

The same conspiracy theories pop up every single time there’s a mass shooting in the United States, with minimal variation. There are a couple of ways to look at this. On the one hand, maybe the conspiracy theories are right, and the Powers That Be, the ones who are really behind the mass shootings, like to use the same playbook over and over again. On the other hand, maybe it’s a combination of factors: common behaviours in unusual situations, fishing for connections, and recycled logic from previous incidents. At any rate, let’s run through the commonalities, and you can see for yourself what I mean.

Multiple shooters

Ever since the Columbine shootings, where there were reports of more than two shooters, nearly every mass shooting has given rise to rumours that there were more shooters than officially acknowledged. I can’t actually find a single shooting that this hadn’t been true of, from the Virginia Tech massacre to the Aurora Batman incident to the Sandy Hook tragedy. Some theories of this type are more popular than others, but the multiple shooter motif is pretty consistent.

Usually, the conspiratorial explanation for this is that the conspirators want to have just one person take the fall for the shooting. However, they have a whole team of agents actually go around shooting people. The reason why they’d want to do this is not always particularly clear. Surely, if you want to blame a single shooter, it’s easier to just have a single shooter than to use multiple shooters and then engage in a no doubt massive cover-up of the others. To keep multiple shooters quiet you’d have to wipe out forensic evidence, intimidate eyewitnesses, scrub media coverage, make sure the other shooters stay quiet, and so on. Essentially, you need a much bigger conspiracy. Does the benefit (say, to the number of casualties inflicted) of having extra shooters justify all that hassle? Who knows.

The non-conspiracy explanation is that things get pretty chaotic in mass shootings, scoop-hungry media sources pick up and run with unconfirmed reports, and people are generally lousy eyewitnesses. Random people in the area might be misidentified as additional shooters (as happened at Sandy Hook). People who are known associates of the actual shooter or shooters might be lumped in with them, under the assumption that an entire clique is simultaneously shooting the place up (as happened at Columbine). Police, security guards, or intervening bystanders might be misidentified as additional shooters, or there might be incidents of friendly fire when the shooter and others get into a gun battle. From the psychological end, we know that people tend to massively overestimate the effectiveness and accuracy of eyewitness accounts. People will misperceive and misremember events, particularly if they’re being shot at or simply having a gun waved in their faces. It takes considerable work to piece together what happened in a given situation based on eyewitness accounts, and some accounts will inevitably end up being wrong.

Crisis actors

[image error]

Nope!

This didn’t properly get going until the last five years – it really kicked off around the time of the Boston Marathon bombing and the Sandy Hook massacre. These days, a mass shooting in the news is basically a guarantee that in the next 24 hours at least 100 different people on the internet are going to use the red paintbrush tool in MS Paint to put meaningful circles around pictures of people’s eyebrows.

Usually, this is all in aid of the idea that some people involved with a mass shooting are “crisis actors” – fake victims generally used in disaster preparedness drills, but co-opted by the conspirators in order to act out roles in fake mass shootings. The supposed presence of crisis actors is generally used to argue that the incident in question was an outright hoax and that no one was killed, or, in a weaker version, that the shooting happened but that certain people were “planted” in advance in order to shape the narrative somehow.

Sometimes this is based on resemblances between people in different crises, as seen below. Some seem to have fallen victim to the so-called “other race effect” in face recognition: when someone is looking at a face of someone of another race, they’ll often confuse them for other members of that race. This is sometimes called the “they all look the same to me” effect.

“Bad acting”

Another facet of the “crisis actor” theories, the “bad acting” gambit point to victims, victims’ families, or witnesses displaying inappropriate emotions in interviews following the tragedy. They might appear strangely calm or flat, or even laugh despite what they’ve supposedly been through. If these people had really been victimized, surely they’d be sobbing uncontrollably. They’re not, so this proves they’re faking it – they’re crisis actors rather than real victims.

Grief is a pretty complicated thing. Research into the psychology of grief and mourning shows that people don’t always display the emotions that we expect them to in the aftermath of a tragic event. Crying is common, but strangely, so are paradoxical emotions like laughter. Research shows that there’s a tremendous variety of ways in which people respond to loss. Some laugh, some cry, some enter a dissociative state and display reactions that are out of step with reality. Beyond that, the media frenzy around mass shootings is hardly an ideal coping environment. Who knows people’s reactions could be affected when someone is thrust into a bizarre situation of bright lights and TV cameras everywhere?

Not only that, but many of the videos that claim to show “obvious lying” use cues for lie detection that work no better than chance. Humans simply aren’t very good natural lie detectors – even trained observers barely do better than chance levels of accuracy in favourable conditions.

The motives

Gun control

Almost immediately, people speculate about the real motive for the shooting (as opposed to whatever the official story might be). In the US, gun control is usually put forward as the primary motive for mass shooting conspiracy theories. The idea is that a mass shooting will shock the population into giving up its guns, which will allow the final takeover of the country by the New World Order. This ties the individual shooting theories into a larger narrative about sovereignty, control, and the Second Amendment.

Distraction

About a week after any mass shooting, there’ll be a slew of blog posts and Youtube videos about “what they did while we were all distracted.” Now maybe gun control is a motive, but maybe the REAL motive is to occupy the news cycle and distract everyone from things like trade treaties, new laws, disease outbreaks, and so on.

Connection to some other conspiracy theory

Gun control isn’t always where things stop. Usually, a bit later, some other possible connections come out that suggest other motives or methods for the conspiracy. For example, David Hogg, an outspoken survivor of the Parkland shooting, has come under suspicion since his father is a retired FBI agent. Since conspiracy theories about Parkland have gained traction in the Trump-friendly media, and Trump’s not too hot on the FBI lately, this has led some people to speculate that the FBI alumni network is part of a Deep State conspiracy to discredit Trump.

[image error]Similarly, James Holmes, the Aurora, Colorado shooter, had a couple of things come up. He was a grad student in neuroscience, which brought up suspicions of a connection to some sort of mind-control project.* His father developed software that could be used to detect point-of-sale credit card fraud, so someone came up with the idea that he was about to be deposed for a LIBOR hearing the next week, and the mass shooting was a way of keeping him quiet (never mind that there were no such hearings, his expertise had nothing to do with interest rate manipulation, and it’s not really clear how framing his son for mass murder would keep him quiet). Likewise, Omar Mateen, the Orlando shooter, worked for the security company G4S at some point. G4S has had government contracts. Therefore, it’s not much of a leap to say that Mateen works for the government. (it kind of is)

X is controlled opposition, Y is the real story

There are contradictory conspiracy theories about most major events, and mass shootings are no exception. About a week after any mass shooting, the stickied post in the conspiracy-theory community on Reddit will be a list of suspicious things about the shooting, most of which seem to point to completely separate conclusions. It’s not possible that there were multiple shooters, a single brainwashed mind-controlled shooter, and no shooters at all. Likewise, it’s not possible that it was both a targeted hit on a particular person and a complete hoax in which nobody actually died. Most people seem content to let these contradictions go unexamined and repeat, Trump-like, “something is going on,” but every so often advocates of the rival theories will clash. And in any argument between rival conspiracy theories, as time goes on, the probability that one side will accuse the other of being a tool of the conspiracy approaches 1. The false-flag, multiple-perpetrator crowd will accuse the staged-hoax, nobody-died crew of being planted by the conspirators to make everyone else look crazy. Meanwhile the staged-hoax, nobody died faction will claim that the false-flag, multiple-perpetrator theory is a “limited hangout” – a half-truth meant to distract people from the far more shocking reality that the whole thing is completely made up.

Predictive programming

Mass shootings are usually accompanied by claims of predictive programming – in other words, claims that the shooting was “predicted” in some piece of media, often by the name of the city or perpetrator appearing in a big-budget movie from the past few years. Often this comes up quite a while after the fact, as it takes a while for people to find something that seems to match the shooting. The alleged motive here is that by inserting clues into fiction, the psychological impact of the event is somehow enhanced. I went into the psychological side of predictive programming in another post, but suffice it to say that there’s good reason to think it wouldn’t particularly work and these parallels are probably just coincidences.

Finally, a confession

I wrote most of this post a couple of years ago, around the time of the Orlando shooting, and never quite got around to finishing it. Almost nothing has changed. The crisis actor theories might have become more prominent in the last couple of years, and Trump is in the mix now, but otherwise this is just same shit, different shooting.

In other posts on this blog I’ve talked about the conspiracy mentality, or conspiracist ideation. I don’t think there’s a better example of a strong conspiracy mentality than the fact that there’s apparently a decent-sized crowd of people who think that mass shootings don’t happen – that all of them are fake, that if you peel back the curtain you’ll always find multiple shooters and crisis actors and MKULTRA. I don’t think there are any published psychological studies yet that look at why these events in particular attract so many of these theories. Of course, maybe that misses the bigger picture. Crisis actor theories aren’t restricted to mass shootings or terror attacks – there’s a guy on the David Icke forums who comes up with crisis actor theories about bus crashes in the UK (as far as I can tell from his posts, all bus crashes reported in the media are staged hoaxes by Big Seatbelt).

October 9, 2017

Adam Ruins Everything: Episode on conspiracy theories

This week, US TV Show Adams Ruins Everything has an episode on conspiracy theories. If you are in the US, you can tune in on 10th October 10/9c on Tru TV. If you are not based in the US, you should be able to catch the episode online after it has aired.

In the show, Adam adds humour backed with scientific evidence to discuss important topics. This week’s episode will showcase some of the research into the psychology of conspiracy theories that we discuss on this blog, such as to do with cognitive biases (see clips below).

I was involved in advising the writers on the script to ensure it was accurate and – to my surprise – was invited to join the cast on set. During the series, Adam brings on experts in the topic area to join the characters in a scripted segment; I involved in such a segment and was invited to discuss some of my work examining the consequences of conspiracy theories.

It was a fantastic experience to join the cast and crew on set and whilst at the time of writing this post I have not seen the full episode, it is great to bring our research to a wide-reaching audience.

Here are some teaser clips:

June 30, 2017

Prevention is better than cure: Addressing anti-vaccine conspiracy theories

In a new paper that we have recently published, we found that people can be inoculated against the potentially harmful effects of anti-vaccine conspiracy theories, but that once they are established, the conspiracy theories may be difficult to correct.

The paper with the tag-line “prevention is better than cure” has been published in the Journal of Applied Social Psychology by myself and Karen Douglas. The paper includes two experimental studies where participants were exposed to anti-vaccination conspiracy theories and factual information on vaccinations in alternate order. The participants then had to decide if they would vaccinate a child.

We found that participants who were given anti-vaccination conspiracy theories, before reading factual information about vaccines, were less likely to decide to vaccinate a child. Those who had the factual information first were resistant to conspiracy theories and were more likely to vaccinate.

In our previous research, we have demonstrated that conspiracy theories can potentially stop people from engaging in society in a positive way (see various posts on this blog such as here). This current research highlights that once a conspiracy account has been established, it may be resistant to correction. It is, therefore, important that other tools are developed that may help combat the negative impact of conspiracy theories.

[image error]

You can access a full copy of the paper here.

May 26, 2017

Fake news, conspiracy theories and the UK general election

Popular conspiracy theories propose that members of UK government murdered Diana, Princess of Wales; climate change is a hoax orchestrated by the world’s scientists to secure research funding and pharmaceutical companies and governments cover up evidence of harmful side effects of vaccines for financial gain. Conspiracy theories like these accompany almost every significant social and political event and can typically be defined as attempts to explain the ultimate causes of events as the secret actions of malevolent powerful groups, who cover up information to suit their own interests.

Fake news, which involves the publication of fictitious information on social media, appear to be a fertile ground for conspiracy theories to flourish. Indeed, millions of people subscribe to conspiracy theories. Conspiracy theories are, therefore not reserved for only people who are paranoid, but rather, they are a normal everyday process that we are all susceptible to. With the popularity of social media, conspiracy theories are at our fingertips more than ever before.

What’s the harm with conspiracy theories, anyway? In research conducted with my co-author, Prof Karen Douglas at the University of Kent, we have shown that being exposed to the idea that governments are involved in plots and schemes reduces people’s likelihood of wanting to engage in the political system. People were less likely to want to vote.

We found that being exposed to conspiracy theories can make people feel politically powerless and feel that their vote will not count; if the government is conspiring against us, how can I make a difference?

In our most recent research, we have also uncovered that conspiracy theories are potentially resistant to correction. Once a person subscribes to a conspiracy theory, they can be increasingly difficult to debunk.

It is, therefore, important that at the point of exposure to information, people are thinking critically. If the headline sounds too good to be true, it very well may be! Here are some practical suggestions to help with this:

Think about the source; who has written the article?

Evaluate the evidence contained within the article; is the piece based on fact?

Read multiple articles from a variety of outlets on the same topic. Do not just trust one article; try and get a full picture of the story that takes into account all sides of the argument.

We know that conspiracy theories can be potentially damaging and difficult to debunk. So, think critically before clicking “share” on Facebook or “retweeting” on Twitter. Be sure you feel confident that the piece is accurate before sharing!

Reposted from Staffordshire University’s Election Experts.

Rob Brotherton's Blog

- Rob Brotherton's profile

- 22 followers