Warren Adler's Blog, page 34

September 22, 2015

Doris Booth

I dreamed of being a female Hemingway all of my life, and have a love affair with good books. I launched Authorlink in 1996 to help writers become known. My firm has both a publishing arm and literary arm, both of which are not taking on any new titles at this time. I have sold works to MacMillan, St. Martin’s Press, Farrar Straus and Giroux, Random House and others.

“I dreamed of being a female Hemingway all of my life, and have a relentless love affair with good books. I published my first work at age 17—a poem that was read on the radio. I have been hooked to the world of publishing ever since. I launched Authorlink in 1996 to help writers become known. My firm has both a publishing arm and literary arm, both of which are not taking on any new titles at this time. I have sold works to MacMillan, St. Martin’s Press, Farrar Straus and Giroux, Random House Audio and others. Now we are bringing authors to Dallas for the new Authorlink Sociable Lecture Series, to help put the excitement back in books. Our first event will be September 12, 2015.

Everyone has a story inside. Stories weave the very fabric of our culture. They add meaning to our experiences, and help us make sense of who we are.”

The post Doris Booth appeared first on Warren Adler.

Michele Hanson

I started writing to stop myself going mad. I wasn’t happy at the time. I was thirty, single, a teacher, and my hot water heater kept breaking down. Every Wednesday, my day off, I stayed in waiting for the heater repairmen to come. Every Wednesday they did not come. I stayed at home, crying and screaming. And then I started writing a diary, about the broken heater and everything else that made me unhappy, and then I read it to my friends for a laugh.

Then another writer noticed my diary and thought I should take it more seriously, so I did. Went to a little creative writing class, got a story into an Arts Council anthology, and then got noticed by another journalist, who knew another journalist who edited the Women’s page on the Guardian newspaper, who asked me to try and write a humourous column on local government. So I did, and that was the beginning of my writing career.

Which just goes to show that it’s luck that does it. Luck that my boiler broke down and filled me with fury, which needed an outlet, luck that my lodger’s girlfriend knew a journalist who knew the editor of the women’s page, luck that local government is raving mad and a laugh a minute, so that I didn’t even have to make up any jokes. And then I started writing about my teenage daughter and my elderly mother, both of who rarely shut their mouths and who behaved outrageously and provided fabulous copy. More luck. Now I write about myself and my friends, all about 65 -70 plus, as we become older and sicker and life becomes more tragic, as we and the world go down the pan together. You either laugh or you cry. I have chosen to laugh whenever I can. Often in writing.

END

The post Michele Hanson appeared first on Warren Adler.

September 14, 2015

THE DAILY BEAST Features “Why Should Novelists Be Politically Correct?”

“The recent flap over a romance novel titled For Such a Time whose plot features a concentration camp inmate falling in love with her Nazi captor has aroused the wrath of various critics and readers on grounds that it is too discomfiting and disturbing to have been published.

While I can understand why some readers are offended by the premise, it smacks of political correctness gone awry. The problem is that it has invaded an art form that can be dangerously compromised by the basic tenets of political correctness, which posits that any expression or attitude that discomfits others must be excised from all forms of public communication.

In its basic concept, what makes the novel unique is that it is a fictional portrayal in which the author not only relates the actions but imagines the thoughts of his or her characters. As they say, actions speak louder than words but actions in real life do not always mirror one’s true thoughts and motivations. Those of us who assiduously follow the oral antics of politicians need no further explanation.” CONTINUE READING ON THE DAILY BEAST

The post THE DAILY BEAST Features “Why Should Novelists Be Politically Correct?” appeared first on Warren Adler.

Why Should Novelists Be Politically Correct?

The recent flap over a romance novel titled For Such a Time whose plot features a concentration camp inmate falling in love with her Nazi captor has aroused the wrath of various critics and readers on grounds that it is too discomfiting and disturbing to have been published.

While I can understand why some readers are offended by the premise, it smacks of political correctness gone awry. The problem is that it has invaded an art form that can be dangerously compromised by the basic tenets of political correctness, which posits that any expression or attitude that discomfits others must be excised from all forms of public communication.

In its basic concept, what makes the novel unique is that it is a fictional portrayal in which the author not only relates the actions but imagines the thoughts of his or her characters. As they say, actions speak louder than words but actions in real life do not always mirror one’s true thoughts and motivations. Those of us who assiduously follow the oral antics of politicians need no further explanation.

Shakespeare, as always, offers an exception to the rule, since the characters in his plays often reveal their inner thoughts through monologues, of which the unforgettable speech of the conflicted Hamlet will attest.

A serious novelist, above all, seeks truth and understands that an action by a character is often contrived to pursue a contrary attitude or motive. Those characters conceived in the author’s imagination often are portrayed to act socially and morally acceptable to people with whom they interact. As in real life many people hide counter thoughts and judgments that can insult, do emotional harm, display bias, prejudice and outright hatred all the while pursuing a conspiratorial agenda. Of course, one should strive to apply inner discipline to speech that reaches an unacceptable level of vilification or danger to others. The concept of free speech has a long history of debate attempting to define its boundaries constitutionally, psychologically and emotionally – there may never be a definition that satisfies everyone but it is the job of the serious novelist and the metric of his or her talent to look beyond the surface of speech and public appearance and delve deeply into a character’s mind in order to reveal the true motives that lie behind the façade.

At times the character, as in the case of the romance novel cited earlier, is revealed as knowing full well that he or she is acting in a way counter to the overwhelming opinion of others, but he or she cannot discipline powerful inner yearnings and passions to conform to such judgments. In the case of love, for example, no one has yet defined the motivation of how and where such feelings come from.

How does an inmate of a concentration camp fall passionately in love with a person who represents everything that she opposes, whose commitment is to the very cause of her demise?

Argument and debate, however heated, outrageous, offensive, hurtful and profane is the price we pay for the privilege of speaking freely. We are currently going through a period where speech is being severely restricted and goal posts of tolerance are moving closer to allegedly protect people from discomfort of any kind.

Yes, words matter and that old nursery rhyme of “sticks and stones will break my bones but words will never hurt me” seems less applicable to contemporary life as it once was when the tonal level was more a local whisper than a global scream.

In his or her story role, the character may or may not act or use language in what seems like a politically correct way, but it is the duty of the novelist to expose the raw complexity of his or her character’s true thoughts which are often far off the politically correct charts.

This article has also been featured in The Daily Beast.

The post Why Should Novelists Be Politically Correct? appeared first on Warren Adler.

September 10, 2015

I CAN STILL SMELL IT

They had moved three times, from their original apartment in Gramercy Park, to the East Side on 72nd and finally to the big high rise on the West Side overlooking the Hudson.

“I can still smell it,” Rachel said.

“It’s not possible. It’s been four years.”

Larry, because he loved her with the same zeal and passion as when he married her in June 2001, was patient, although, by then, he was really worried about her. September 11th 2001 had come and gone. They had considered themselves lucky, secretly celebrating their good fortune while expressing pity and compassion for those lost.

In the fullness of time, the site had been cleaned up, the building and body remains carted off to far away garbage dumps and some of the area was restored although they were still arguing about the final outcome for the property.

There was no questioning the fact that it did, indeed, smell for that first year. It was a sickening odor, a mixture probably of dust, debris and roasted flesh and bones. When the windows of that first apartment were opened even a crack the smell seeped in and was hard to ignore. Rachel and he tolerated it like everyone else in Manhattan. It was an understandable byproduct of the horror.

That first move a year later was prompted by the idea that perhaps they were too close to the site, about a mile away and that their apartment might be in the path of an air current carrying the smell which snaked its way through the high rises in lower Manhattan and alighted with great intensity on the Gramarcy Park area. That was Rachel’s theory and Larry believed it credible at the time. Her senses had always seemed more acute than his. She had a great eye for color and design and her hearing, as judged by her musical appreciation was exceptional. Her nose for scent was phenomenal and she could detect perfume and sniff the quality of wine like a professional.

When she said she could still smell the pervasive odor of 9/11, he believed her, although he could no longer detect it.

“Who am I to question the quality of your nose?” he joked, often teasing her when she stuck her nose in a wine glass filled with red wine.

They tried all sorts of air cleaners, mists, plug in devices, appliances that promised to clean the air. Apparently these things did not work for Rachel. After awhile, they began to argue about it since his own unscientific survey among his colleagues at the office and friends revealed that no one else had the same olfactory experience.

“I just don’t understand it,” he told her. “You must be the only one in Manhattan that still smells it. Maybe it’s psychological.”

“Are you suggesting I see a shrink?” she rebutted.

“What I mean,” he continued, “is that it could be a memory thing. But then, when it comes to that trauma, everybody in town, the country, the world, is afflicted with that memory. Who could ever forget?”

“It’s the smell Larry. I do understand what you characterize as the memory thing. No one will ever forget that monstrous act by those terrible people. That is an indelible memory. It will be with us forever. But the smell, it’s this crazy byproduct. I can’t get rid of it.”

With the exception of that smell, life appeared otherwise normal. She worked as a copywriter with one of the big advertising agencies and he was an art director with another agency. Still in their twenties and earning good money, they had friends, kept in touch with parents and siblings who lived out of town and planned a future with kids. They had had a nice garden wedding in her parents house in Cedar Rapids, Michigan and went back each Christmas to visit with one of another set of parents. He grew up in Scranton, Pennsylvania.

If it wasn’t for the smell, they were otherwise unmarked by the event, although there was no avoiding the general fear that it would happen again some day. It was always in back of one’s mind.

Of course, news of the cleanup was in the papers daily for months following the tragedy. People volunteered. Many went down to the site to assist with food service. Others carpooled. Doctors and nurses volunteered their assistance. Police, fireman and forensic experts scoured the site for remains. Some were found and identified. Others were not. Everyone felt the grief of the survivors who had lost loved ones.

In the immediate aftermath the air quality, along with the smell, was annoying but not debilitating. Some predicted that many of those who worked at the site might suffer from lung problems later in life. But the amazing thing was how New Yorkers coped, hung in there, lived their lives to the fullest and prevailed.

There was something intrepid about New Yorkers. Both Larry and Rachel were proud to be a part of such resilience and optimism. Three years after the event New York was booming, bigger than ever. Cranes building big high rises were everywhere in Manhattan. Brooklyn, too, was booming. The Bronx was resurgent.

On the other hand, except for the conflicts over what to do with the site and compensation for those who lost loved ones, people were forgetting and growing less uncomfortable about the possibility of another attack. While everybody recognized the potential threat, it was losing any sense of immediacy. The Bush administration was reviled by opponents who thought the fear factor was being used as a political weapon, and most people in New York City hated the President for invading Iraq, feeling that the invasion only exasperated the situation. The fact was that except for security lines at the airports, the presence of Police and National Guardsman at various sensitive places like Grand Central Station, certain public places where people walked through metal detectors and had their pocket books searched, and the stories in the newspapers, the fear of an attack like the one that had destroyed the world trade center was dissipating.

“I wish it would go away,” Rachel told him with increasing frequency, meaning the smell. “It’s here in this apartment. I know it is.”

“That’s what you said when we lived in Gramercy Park.”

“Okay, so it’s a coincidence. But it’s here Larry. I can smell it.”

Larry checked with the management of the apartment house to see if anyone else complained about the smell. No one had. Larry reported to Rachel what he had learned.

“Would I complain, if I didn’t smell it?”

He couldn’t argue with that and he tried his best to be patient and sympathetic. In the end, when their lease was up they moved to the West Side to a brand new apartment complex that was being built overlooking the Hudson River. The view was gorgeous and there were wonderfully exhilarating breezes that floated over the river and reached their terrace on the 30th floor.

“I’m so sorry Larry,” she told him after they had lived in that apartment for a month. “I can still smell it.”

“What is it like?” he asked, determined to be patient.

“Like the same as it was when I first smelled it right after 9/11.”

“Be more specific.”

“Like dead people, I think.”

“Have you ever really smelled dead people?”

“Not really. But it is what I imagine they might smell like.”

Of course, he had asked the question before, but he was beginning to think it might be a physical thing, something that had to do with complex biological factors having to do with the sense of smell. Although he had earlier suggested that she see a shrink, he decided to offer a less threatening alternative.

An ear, nose and throat specialist declared, after various tests, that everything appeared normal.

“I suppose that’s a relief,” Rachel said after they had received the test results. “Except that I can still smell it.”

Finally he was losing patience with her insistence. It was having an effect on their relationship. She was getting more restless, sleeping less, tossing at night and inhibiting his own sleep patterns. Sometimes they would discuss the problem of the smell long into the wee hours.

“I smell it now, Larry. Believe me.”

“You’re imagining it.”

He had taken refuge in that idea, since any other possibility was unexplainable.

“Even if I was imagining it, I can still smell it.”

“All the time? Is there any time when you don’t smell it?”

He had asked that question repetitively, as if it might keep hope alive that she was afflicted with the odor at ever diminishing intervals. Unfortunately, the answer was also repetitive.

“It never leaves me, Larry. But it is most intense at home. Maybe when I am thinking of other things at the office, I can ignore it although it doesn’t go away, but when I get back to our apartment it is constant. No matter what I do here in the apartment it is always with me.”

In time, it became for her a dominant obsession. It seemed to pervade everything she did and he sensed that she was growing more and more desperate about the affliction although she appeared fearful of mentioning it. He could tell it was on her mind by the way her eyes drifted and her nostrils twitched.

Finally, almost in desperation, she consented to a visit to a psychiatrist. She had contemplated going by herself, but she decided that since Larry was the most affected by her affliction, he was entitled to a psychological explanation, if one was available.

The psychiatrist, a pleasant and patient middle-aged man, offered an assessment that was highly technical. He referred to that section of the brain that dealt with the sense of smell, the smell brain he called it, and went through a series of possible physical and psychological factors that dealt with trauma and the effect it had on memory.

He had asked her many questions about her childhood. Had she experienced any childhood traumas? Did she have nightmares? What were her principle fears? Had anything happened to her in her lifetime that suggested some relationship with fear and smell? As to the phenomena of the terrorism threat he was more than curious.

“Are you afraid that another attack is imminent?”

“No more than anyone else.”

“Do you panic when you ride a bus or subway or go on an airplane?”

“Acceptance. Not panic.”

“Do you have nightmares of death?”

“If you mean death caused by a terrorist attack the answer is no.”

“Do news reports of terrorism attacks bother you?”

“Sure they do, but not to the point where I get too upset to function.”

“Are you afraid to live in New York?”

“Of course not. I’m here aren’t I?”

His diagnosis was understandable and logical, and he did offer her some hope.

“It could be,” he explained to both of them after her session when they met in his office. “That your fear of this terrorist danger is so palpable, so intense, that the odor associated with that tragedy continues to dominate your smell brain.”

“But as I told you, I don’t obsess about a terrorist attack,” she said. “I fear it sure, but I don’t dwell on it.”

“Not consciously,” the psychiatrist said. “It is an evolutionary theory that the sense of smell was the principal defense mechanism of our ancient forebears. They could sniff danger from predators and poisons. It was their most powerful sense and is still powerful in our smell brains.”

“And this explains why I can still smell debris?”

“It’s a possibility.”

“Have you seen other people like me?” Rachel asked him.

“Yes I have. Fear is very disruptive to one’s mental health.”

“But I don’t think about it much.”

“Except when the smell reminds you of it.”

She shook her head, rejecting the notion.

“So you imply that it’s because the fear in my subconscious is to intense that it induces this sense of smell.”

“Maybe.”

“Maybe?”

“Psychiatry is not a pure science. It deals with clues, assumptions and interpretations.”

His explanation struck both her and Larry as less than helpful.

“It feeds on itself,” the psychiatrist told them. “The smell induces memory, like a chain reaction. Have you ever read Proust?”

Rachel and Larry looked at each other and shrugged. Neither he nor Rachel had read him.

“The smell of Madreline cake when he was a child,” the psychiatrist went on, “induced in him a lifetime of memory and served as the trigger to motivate him to write his masterpiece spanning multiple volumes, all because of the memory of that smell.”

“So what can I do about it?” Rachel asked him. “Write a book.”

He laughed politely.

“I’m going to prescribe a medicine that has worked in cases like yours. It was originally used to stop nausea in pregnant women.”

“I’m not pregnant, not yet,” she said looking at Larry.

“It may not work,” the psychiatrist said.

“And if it doesn’t work?” Rachel asked.

“Find a way to live with it,” he said. “Like Titinnitis, a hearing difficulty that is rarely cured.”

“That it?” Larry asked, after exchanging troubled glances with Rachel.

“One day it might simply disappear,” the psychiatrist said. It was a very unsatisfactory diagnosis.

“It’s already been more than four years,” Larry said.

“I wish I could be more helpful,” the psychiatrist said.

“So do we.”

For the next few months in their new apartment, they tried to lead normal lives. Nothing changed. The pills he gave her did not work. Once again, she began to make noises about the apartment being a place where the smell became worse.

“Where can we go then?” he challenged. Clearly, he had been patient, understanding and cooperative, had done everything possible to help her cope with the situation.

“Maybe if we moved upstate. Somewhere in the Hudson Valley further up the river,” she suggested.

“It’s something inside you Rachel, not in the apartment. Will these moves go on forever?”

“I hope not.”

He felt deeply sorry for her affliction. Love, he sensed, was turning to pity and compassion. They slept less and less engaging in long nocturnal conversations. They made love less often and when they did it seemed routine, not spontaneous as it had been at the beginning.

But he agreed to look for a place further up the river, vowing to himself that this would be the absolute last time they would move. Moving was an exhaustive process and was financially draining as well. Nevertheless, he was determined to help Rachel.

“We’ll have to commute by train more than an hour to get to work,” he told her.

“I’m willing if you are.”

“Maybe if we went up there and you sniffed around. You know what I mean. Trees act as filters.”

“That would be wonderful.”

They drove further up the Hudson valley, past Peekskill, but she could still detect the smell.

“Does it seem less so up here?” he asked.

“I’m not sure.”

Nevertheless, they contacted a real estate broker and rented a nice house in Hudson, with a garden, surrounded by trees and the air, to him at least, seemed fresh and clear.

It didn’t help. She could still smell it.

“I’ll never move again,” he told her. He was beginning to see how this mad affliction was chipping away at their relationship. He tried to rationalize his situation by characterizing her as “handicapped.” If she was “handicapped” he reasoned would he stand by her no matter what. In sickness and in health the marriage vow decreed. Taking refuge in the idea, he felt ennobled by his sacrifice. It was a sacrifice.

She had given up her job and was working as a free lancer, doing her work at home. He couldn’t, as he was needed by his colleagues in face-to-face situations. The commute was exhausting him, making him irritable and depressed. Of course, she was well aware of what was happening, but was helpless in the face of what was assailing her.

One day, he came home and she was wearing a surgical mask obviously impregnated with heavy perfume which smelled like lilacs.

“Does it work?” he asked.

“Only when I keep it on,” she said, her speech muffled by the mask. She took it off only to eat and drink and when she talked on the telephone. She began to sleep with it. The odor of lilacs was so intense it was giving him headaches. When he complained, she changed the perfume to other floured scents, but nothing worked as well as lilacs.

“I can’t stand the smell of it,” he told her often, trying valiantly to live with it, feeling guilty, finding it more and more difficult to cope with the smell.

“Now you see what I mean,” she said.

“It’s driving me crazy.”

“For me, it’s either that smell or the other. At least the smell of lilacs doesn’t remind me of the other, the horror of it.”

As time went on, he rarely saw her full face. Her speech behind the mask was muffled and, at times, he found it difficult to understand her words. The house was inundated with the smell of lilacs. It permeated everything, even his clothes. His co-workers would comment about it and after awhile he noticed that they preferred to keep their distance. He was too embarrassed to explain what it was all about.

Finally, his boss called him into his office.

“What is it with you Larry? You stink of perfume, smells like lilacs. It’s making some people around here nauseous. Are you wearing this scent?”

“Actually no,” he responded. “It’s my wife’s. It gets into my clothes.”

“You’d better get rid of that stink, Larry. Really, it’s upsetting people. It’s too heavy. Yuk. I’d prefer if you left my office now.”

As he began to leave the office, his boss called out.

“It’s either my way or the highway Larry.”

At home, he tried sleeping in another room and double washing his shirts and underwear and sending his clothes to the cleaners very frequently. Nothing helped. He explained the situation to Rachel.

“I may lose my job,” he said.

“Over the smell of lilacs? That’s ridiculous.”

“No it isn’t,” he acknowledged. “It’s driving me crazy as well.”

The boss kept his word and he was fired. In some ways it was a blessing because it forced him to confront his situation. She couldn’t stand the smell of the World Trade Center aftermath, and the lilac scent was the only palliative that worked for her. And he couldn’t stand the smell of lilacs.

He tried working from home, but it was impossible to live with the scent. By then, love had disappeared, although he did feel deep compassion for her problem and a new emotion “guilt” was beginning to take hold. As a temporary solution, he took an apartment in Manhattan and came up on weekends. Sometimes, she greeted him without the mask, but the smell of lilacs had seeped into the atmosphere of the house. He could barely wait out the weekend.

“I can still smell it,” she would tell him when the mask was off and the lilac scent did not help.

Finally he could stand it no longer.

“We’re both casualties of 9/11 Rachel.”

She agreed and they got a friendly divorce. It took him months to get rid of the smell of lilacs. He called her on the fifth anniversary of 9/11.

“I can still smell it,” she told him.

Find this short story and others in NEW YORK ECHOES

The post I CAN STILL SMELL IT appeared first on Warren Adler.

September 3, 2015

“Should I Start Lying About My Age?” Featured on THE HUFFINGTON POST

“I am seriously thinking about lying about my age. Of course it’s impossible. The Internet has my age engraved in perpetuity.

I notice the difference immediately after my most casual face-to-face social revelation of the “number” — even if it is merely a reminder to my friends and my children. The change in expression is immediate, and the processing in the receiver’s brain, while subliminal, is obvious.

In a flash I have changed my status from respectful and collegial and transformed it suddenly to “over the hill,” someone to be tolerated, politely and diplomatically endured but no longer consequential. The reaction is typical and understandable. It is built into the life cycle, a generational flaw that carries few exceptions. It is hard to reeducate people to the notion that humans are not like socks, where one size fits all.” Continue Reading on THE HUFFINGTON POST

The post “Should I Start Lying About My Age?” Featured on THE HUFFINGTON POST appeared first on Warren Adler.

August 27, 2015

Torture Man

Coming Soon! The caller made it clear—$10 million or her daughter’s head. The power of unintended consequences sends the privileged life of prominent anti-war activist Sarah Raab crashing down around her. Fear and terror take hold and Sarah turns to former CIA operative Carl Hellmann, a man she has only just met and who stands against everything she has been fighting for. How could this happen? Why would a terrorist group target her family? Confusion turns to fear and anger as Sarah faces the shocking truth lying beneath the surface of her life. And though Carl’s interrogation methods violate everything Sarah believes in, they may be the only way to save her daughter’s life. Faced with horrific choices, Torture Man takes the reader on a torturous weekend where Wall Street kickbacks, deceit, corruption, and jihad collide on the Upper East Side of New York City.

The post Torture Man appeared first on Warren Adler.

August 26, 2015

VENTURE GALLERIES Features “On Rejection and Renewal: A Note to Aspiring Novelists”

“YOU’VE SPENT MONTHS, perhaps years, composing your novel. You’ve read and reread it hundreds of times. You’ve rethought it, rewritten it, and revised it, changed characters, dialogue and plot lines. Writing your novel is the most important thing in your life. It has absorbed your attention, almost exclusively. Both your conscious and your subconscious mind have been obsessed with it. You have read parts of it to your friends, family, former teachers. Most think it’s wonderful.

You have finally considered it finished. Armed with optimism and self-confidence, you obtain from the Internet a list of agents and begin to canvas. You agonize over whether to send your precious manuscript to one agent at a time or to a number of agents. You choose the first option. Just in case, you send it electronically, unsure of whether or not this is now standard practice. You have high hopes. You are aware of the massive changes in the publishing business, but have chosen to take the traditional path as your first option.

Weeks go by, then months. The agents are, you believe, reading it in the office, passing it around, deciding to take it on. You live on such hopes. Finally you call the agent’s office. They haven’t a clue as to who you are. Somehow, they are reminded and search through the piles of manuscripts in their office, find yours and send you back a standardized letter, perhaps out of politeness made to look like an original.” CONTINUE READING ON VENTURE GALLERIES

The post VENTURE GALLERIES Features “On Rejection and Renewal: A Note to Aspiring Novelists” appeared first on Warren Adler.

August 17, 2015

Lying About My Age: A Reflection on Ageism

I am seriously thinking about lying about my age. Of course it’s impossible. The internet has my age engraved in perpetuity.

I notice the difference immediately after my most casual face-to-face social revelation of the “number” – even if it is merely a reminder to my friends and my children. The change in expression is immediate, and the processing in the receiver’s brain, while subliminal, is obvious.

In a flash I have changed my status from respectful and collegial and transformed it suddenly to “over the hill,” someone to be tolerated, politely and diplomatically endured but no longer consequential. The reaction is typical and understandable. It is built into the life cycle, a generational flaw that carries few exceptions. It is hard to reeducate people to the notion that humans are not like socks, where one size fits all.

What I have begun to realize and which has motivated me to write this screed is that, whether deserved or not, one’s number reveals one’s category and my category and those of my peers sends the message of “tolerate but irrelevant.” It is a form of bias that closes the door on the wisdom that only first hand experience can convey.

The fact is that my “number” and upwards is shared by many people who are still very much involved, active participants in busy and arguably important human endeavors. We may be merely statistical survivors but we are still out there, a senior cadre of wisdom and experience that cannot and must not be consigned to the rubbish bin of contemporary history. We are still climbing the hill and are not yet at the summit heading downward.

We have witnessed the good and bad choices by politicians, journalists, academics, and various leaders in numerous other occupations that collude to create our culture. We have observed their many follies and their successes, have walked through the mountains of corpses of the last century, the stupidities of unworkable ideologies, and have seen the glories of science that have vastly improved our health, longevity and lifestyles.

In the U.S, there are six million in the number category of which I speak. Admittedly some of that group are incapacitated physically and mentally. But there are millions still in heavy involvement in contemporary life, contributing their experience, insight, imagination and creativity to make positive change in society.

There may be skeptics out there who believe I am offering conclusions based on narrow personal experience but I am willing to bet the barn there are millions out there who will testify that I am not alone in my assessment.

I am as active in my career as ever. My daily writing habits have not changed. I continue to write my novels, plays, poems and essays and do what writers do which is to conjure ideas, fashion them into stories and generally communicate the results to potential readers.

I do confess that I am not as agile or as flexible as when I was a 23 year-old soldier in the Korean War or as formidable as I used to be in other areas requiring more extreme physicality but I have not yet reduced my twice a week pilates exercises and can still claim a robust level in my fantasy life.

Nevertheless when I do honestly reveal my “number” to an inquisitive stranger, especially those of a younger demographic, I note an instant revision of their attitude and I am instantly reminded about every cliché about ageism that afflicts the culture from Charles Dickens’ “aged P” character in Great Expectations to the real life possibility of bureaucrats deciding end of life options.

Aged P, for those who don’t recall this wonderful masterpiece by Dickens, was the father of John Wemmick who instructs Pip how to socialize with his aged father “Nod away at him Mr. Pip, nod away at him if you please. That’s what he likes, like winking.”

Consider what can be learned from someone who has lived through the better part of the twentieth-century and on into the twenty-first, a witness to events that would seem to a millennial as beyond imagining. Indeed everything that has occurred in the long lifetime my number implies and having seen with my own eyes the ups and downs of the past offers lessons too invaluable to be dismissed on the basis of “tolerate but irrelevant.”

To throw that demographic of which I am a proud and lucky member on the rubbish heap of irrelevance is a critical mistake. Technology may radically change many things but personally witnessed and lived through experience tells us that human nature, however we manipulate and extend life, however we attempt to change the rules of human engagement, however much we destroy and, hopefully rejuvenate our environment, however long our planet can remain populated by the human animal, our basic nature with all its contradictions and propensity for good or evil will remain the same imperfect specimen.

I can hope only that this message resonates beyond the periphery of the words in this issue. Instead of “tolerate but irrelevant” perhaps those who bear my number and beyond should be regarded with the frame of “listen, consider, and learn.”

Oh yes, my category. I was born seven months after “Lucky Lindy” made his solo flight over the Atlantic to Paris. It was a helluva year. You do the math.

The post Lying About My Age: A Reflection on Ageism appeared first on Warren Adler.

July 30, 2015

The Creative Writing Course That Changed My Life

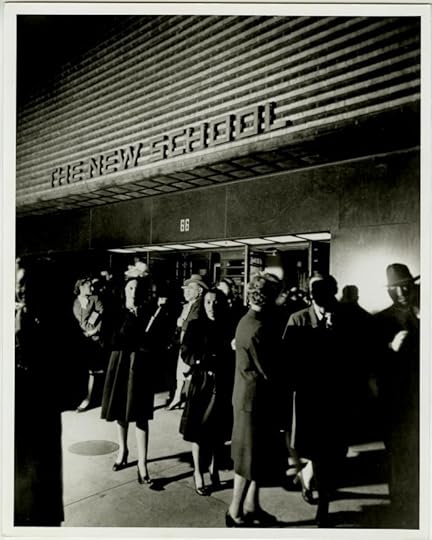

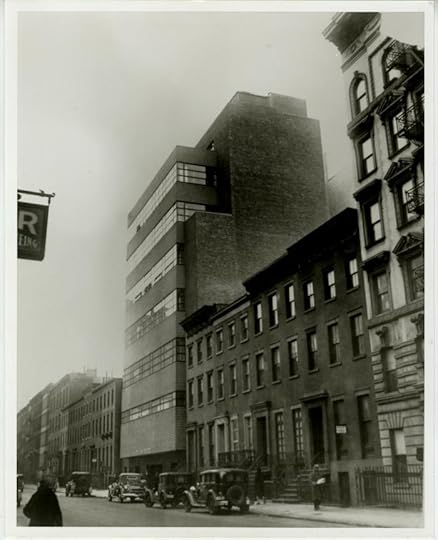

In 1949 when I was twenty-one years old I took a creative writing course at the New School in Manhattan given by Professor Don M. Wolfe. He had been my freshman English teacher at New York University, where I graduated in 1947, just two months shy of my twentieth birthday.

I lived at home in my parents’ Crown Heights apartment in Brooklyn all through college and took the hour-long ten-cent subway ride to the NYU campus in the Bronx, which proved to be an excellent environment for study. Officially I was declared pre-med, although I had absolutely no interest in becoming a doctor, but I had to declare a goal since I was mostly uncertain what career path to follow.

In that fateful freshman year, largely due to Dr. Wolfe’s inspiration (of which he was surely unaware) I decided to be a writer of fiction, changed my major to English literature, gloried in the study of the extraordinary western canon of authors and have since then pursued a lifetime of obsessive composition of novels, short stories, essays and poems through every imaginable phase of rejection, insult, deprecation, praise, acceptance, and a moment or two of lionization.

Bonding In the Class Room

In Dr. Wolfe’s class there were about twenty-five students, of which I was probably the youngest. Many of the men were war veterans and an equal number were women of all ages. Many were not native New Yorkers but had come from all over America to seek writing fame and fortune in what was then the pinnacle of the publishing world.

As was Dr.Wolfe’s modus operandi, we would submit our short stories and he would read them diligently, covering the manuscripts with his pithy comments in red ink. When he found what he thought was the perfect image, sentence, and thought, he would offer a complimentary acknowledgement.

We were all well aware of the common link between us. We were all burning to write what in those days was described as nothing less than The Great American Novel and to savor the fame and fortune that would crown our talents.

We were all well aware of the common link between us. We were all burning to write what in those days was described as nothing less than The Great American Novel and to savor the fame and fortune that would crown our talents.

One could sense this passion in all of us. It seemed to fill the classroom as if it were part of the oxygen. It was what had brought us together in this rare moment in time under the stewardship of a great, unsung professor who knew that the secret of all fiction writing was to use language to convey and illuminate imagery and meaning, to communicate through a form of artistry that illuminates the truth of the human condition that lies at the heart of all literature.

The craft he taught was more subliminal than merely practical. We had the sense that his critiques were based on the search for truth and honesty wrung out of our deepest need to express the meaning of our own experiences, conflicts, and aspirations. We were constantly creating parallel worlds from our imaginations. For students like us (certainly for most) it appeared to be not a question of choice on our part, but a calling.

One of our fellow students was an older fellow, Harold Applebaum, whose poetry appeared frequently in the New York Times, which in those days published a daily poem. Harold was a brilliant writer who sold candy wholesale to support his growing family. Although he might have cringed at the term, he was also the class literary scout. He chose a number of students from what in retrospect was a tremendously talented group to meet outside of class at our various domiciles to read our latest fictional efforts to each other.

The fact was that bonding with others of like motives was the principal ingredient of the creative writing class experience. We needed this connection to be together both in class and out.

We Had No Problem Being Dreamers

Convinced that we were all bursting with talent, we were obsessed with our goal to make our bones in the world of literature. Then, unlike now, it was a celebrated, prestigious and golden aspiration. It was, after all, the age of Hemingway, Faulkner, Fitzgerald, O’Hara, Thomas Wolfe, and the great European and English giants.

Five or six of Harold’s handpicked writing stalwarts, myself included, would meet a couple of times a month to read our latest offerings. One of our group was Mario Puzo, then an unpublished novelist in his thirties who had not yet achieved the fame of his novel The Godfather and the movies that followed. Another was John Burress, who had just got a contract for his first novelLittle Mule. His novel The Missouri Traveler was made into a movie starring Brandon DeWilde. Among the other writers taking courses concurrent with me at the New School was William Styron who was the first of this group to break out into the literary firmament. Some of the others did achieve publication, although none had the success of Puzo and Styron.

who had not yet achieved the fame of his novel The Godfather and the movies that followed. Another was John Burress, who had just got a contract for his first novelLittle Mule. His novel The Missouri Traveler was made into a movie starring Brandon DeWilde. Among the other writers taking courses concurrent with me at the New School was William Styron who was the first of this group to break out into the literary firmament. Some of the others did achieve publication, although none had the success of Puzo and Styron.

We were, at that stage of our lives, what you would call “wannabe” novelists. The fact that we experienced the sheer joy of bonding with fellow writers continues to make this episode in my life distinctly memorable. There was another creative writing class at the New School of which I was a member and at some point it was decided to publish stories selected from the works of those writers attending classes.

In the two years that I attended Dr. Wolfe’s class, two books were published containing the works of the New School’s creative writing students. The two anthologies published in my time were American Vanguard 1950, and Which Grain Will Grow.

In those books are two of my short stories, “The Other People” and “The Girl in the Polka Dot Dress,” both of which have been republished in my more recent two-volume New York Echoes collection.

Creative Writing is About Camaraderie and the Inspiration That Follows

It is true that creative writing courses cannot teach talent. But depending on the skill and understanding of the teacher, they can foster the kind of camaraderie and inspiration that can light the fire of inherent talent inside you.

The title of our anthology, Which Grain Will Grow, came from Shakepeare’s Macbeth 1, iii: “If you can look into the seeds of time and say which grain will grow and which will not, speak then to me.” In my day, as today, there was no guarantee that participating in a creative writing course would assure future success, or the realization of a student’s writing dreams. My own experience may be peculiar to that special time. But again and again, when I turn back to those moments of encouragement from my teacher and my peers, it never fails to offer a special reset of purpose, a recharging of those long-ago dreams.

This Essay Was Originally Published on THE RUMPUS

The post The Creative Writing Course That Changed My Life appeared first on Warren Adler.

Warren Adler's Blog

- Warren Adler's profile

- 111 followers