Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2401

March 4, 2011

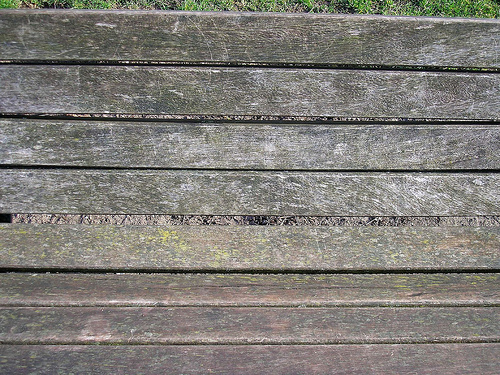

Male Earnings: Worse Than We Thought?

Via David Leonhardt, a disturbing chart from the Hamilton Project suggesting that the wage picture for men is worse than it appears:

The red line is the customary one. It shows the wages for male full-time workers. But the share of working-age men who are employed full-time has been falling, with the reduction coming disproportionately from lower-skilled men. So the blue line, which represents the wages for all men and offers what's arguably more of an apples-to-apples comparison, shows a much darker picture.

I think this is a reminder that we don't see enough discussion of feminism as an economic phenomenon. What's been the macroeconomic policy response to a substantial increase in the potential labor force? Is this decline in male workforce participation a sign of bad labor market conditions, or the statistical manifestation of social change in gender roles? What's the workforce participation rate we want to have?

George Will's Case For High-Speed Rail

Sarah Goodyear notes that though George Will decided this week that high-speed rail is a plot to brainwash people into becoming socialists, he himself was an HSR advocate just ten years ago. This, for example, is a very sensible point:

Two months ago this columnist wrote: "A government study concludes that for trips of 500 miles or less — a majority of flights; 40 percent are of 300 miles or less — automotive travel is as fast or faster than air travel, door to door. Columnist Robert Kuttner sensibly says that fact strengthens the case for high-speed trains. If such trains replaced air shuttles in the Boston-New York-Washington corridor, Kuttner says that would free about 60 takeoff and landing slots per hour."

Thinning air traffic in the Boston-New York-Washington air corridor has acquired new urgency. Read Malcolm Gladwell's New Yorker essay on the deadly dialectic between the technological advances in making air travel safer and the adaptations to these advances by terrorists.

I think this is very sensible. I also think it's perfectly fair for Will to have changed his mind or to decide that the Obama administration's HSR initiative doesn't fit his idea of what our rail policy should be. But earlier this week, Will was saying that HSR investment is so obviously addled that liberals must be lying about their reasons for supporting it, leading him to his brainwashing hypothesis. But surely a person who used to be a pro-rail conservative should be able to at least imagine the possibility of sincere disagreement on this subject.

Politics as a Vocation

Via Scott Sumner, Tyler Cowen has a lesson he wants politicians to learn:

Hard Boards (cc photo by elsie)

A simple one is to do the right thing. That sounds naïve, but if you think about these people, if they don't get reelected, the jobs and lives they fall into are remarkably good. And I don't just mean by the broader historical standards of the human race, compared to the Stone Age, but even compared to other wealthy people in 21st-century America. So most politicians ought to have the stones to vote for what they think is right, even if it may be an idea I disagree with, and say to the voters, "Send me back to my life as whatever. I'm willing to do this to address our fiscal problems, or fight for the right kind of reform, and risk my office." And I just don't see much of that. And that's disheartening.

I definitely agree with the sentiment here, namely that we need to always be doing what we can to raise the level of public morality. But I think people—particularly opinionated writerly people—have a tendency to vastly overrate the merits of this kind of "bold stand" as a political tactic. Nobody likes to read politicians' blogs, but by the same token we don't actually want politicians to act like bloggers. A politician needs to have an "ethic of responsibility" and that entails not just standing up for the right thing, but actually making the right thing likely to happen. And especially in the American political system, that means "playing a constructive role in the assembly of broad legislative coalitions."

Screwing the States

IS writes:

Had an argument with my 70+ YO folks the other day about the budget and in frustration I offered the following:

Strip the Federal Budget of all direct payments to States. That means highway dollars, medicaid, school funding, bloc grants, etc… The whole lot of them. Wouldn't there be a huge savings? It plays right into the GOP's ongoing love for States Rights and forces each State to address how they will serve their constituents. Being the political left leaner that I am, it seems like a winner to me.

What am I missing?

On the level of pure politics, I think nothing's missing here. Reduced federal aid to the states is one of the few budget cuts that polls well. People don't seem to understand how this works and think that state aid money is just used to serve lavish meals at the governor's mansion or something, so they don't realize that cutbacks would lead to unpopular cuts in K-12 education, Medicaid, etc. What's more, this idea would put every single incumbent governor and state legislator in a horrible political position, and today incumbents are overwhelmingly Republicans, so again this is a winner.

The only real problem with this idea is that it's a terrible idea. If we stop spending money on Medicaid benefits for poor people in Alabama, Jeff Sessions is still going to get treatment when he's sick. So will Jeff Sessions' donors and his voting base. That the Alabamians who need Medicaid are consistently outvoted by a richer, older, and whiter set of Alabamians is an unfortunate fact of life but it doesn't change the fact that punishing poor people for the sins of Senator Sessions doesn't really achieve anything.

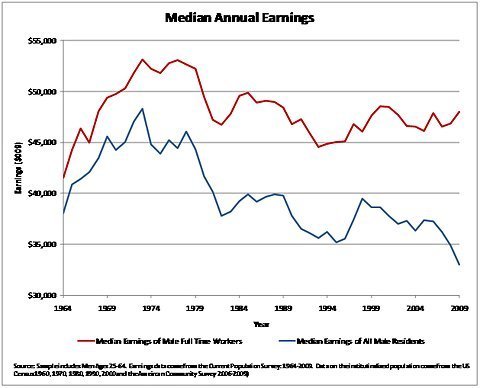

Edunihilism and Early Childhood

Citing James Heckman's latest paper (PDF) Kevin Drum offers what is, I think, far and away the most persuasive criticism of the "education reform" movement—the decent evidence for edu-nihilism:

Heckman says nothing that happens in schools resolves these gaps:

[G]aps arise early and persist. Schools do little to budge these gaps even though the quality of schooling attended varies greatly across social classes. Much evidence tells the same story as Figure 1. Gaps in test scores classified by social and economic status of the family emerge at early ages, before schooling starts, and they persist. Similar gaps emerge and persist in indices of soft skills classified by social and economic status. Again, schooling does little to widen or narrow these gaps.

What I like about Drum's post is that he actually has the courage to take this conclusion to where it genuinely ought to lead:

Intensive, early interventions, by contrast, genuinely seem to work. They aren't cheap, and they aren't easy. And they don't necessarily boost IQ scores or get kids into Harvard. But they produce children who learn better, develop critical life skills, have fewer problems in childhood and adolescence, commit fewer crimes, earn more money, and just generally live happier, stabler, more productive lives. If we spent $50 billion less on K-12 education—in both public and private money—and instead spent $50 billion more on early intervention programs, we'd almost certainly get a way bigger bang for the buck.

This, however, is why I'm genuinely confused about the extent to which the current debate tends to construe people like me and my colleagues on the CAP education team as the enemies of K-12 teachers. If it's true that we don't need to shake up the K-12 school system because what happens inside K-12 schools doesn't alter socioeconomically determined achievement gaps, then the policy remedy is random across-the-board cuts in K-12 school spending. Try taking that idea to Randy Weingarten and see if you become her new best friend! Fortunately Weingarten herself is smarter than that is and is now trying to get teachers on board with changes to the ways teachers get paid.

Now as it happens, I think the Drum/Heckman analysis is a misreading of the evidence. If you look at early childhood interventions and if you look at K-12 schools, I think you see the exact same thing. Most actually existing early childhood programs don't do much to close achievement gaps and most actually existing K-12 school systems don't do much to close achievement gaps. But the very best early childhood interventions "aren't cheap, and they aren't easy" but they work. The same, however, is true of the best K-12 schools, often charters. They aren't cheap and they aren't easy and people wonder if the model is scalable and blah blah blah which is all fair.

I think this all leads us back to common sense. Children spend the majority of their time outside of school buildings. Consequently, peer group effects and parenting constitute the bulk of the non-biological influences on kids. And human children are biological systems heavily impacted by nutrition, genetics, prenatal conditions, ambient lead, etc. But schools also matter. Effective schooling is possible and important. Lack of strong evidence about which methods are most effective points to the need for rigorous assessment, organizational flexibility, and choice.

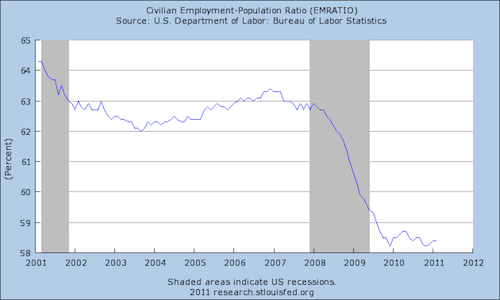

A Long Way To Go

Decent job report today, I guess. But Mark Thoma offers this from the San Francisco Fed:

And there's this from Brad DeLong:

Like Kevin Drum, I think the main issue here is that policymakers in Washington have an exaggerated sense of their own impotence.

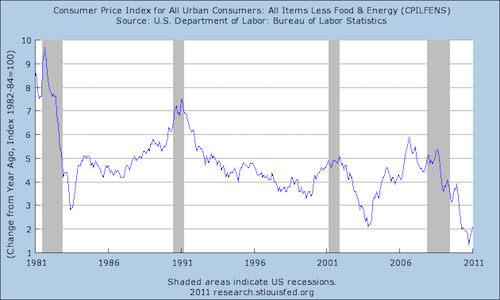

So consider. The federal government can hire unemployed people to do things. It can also just give money to people, whether unemployed or not. And if people had more money, they would increase their demand for goods and services. And if demand for goods and services rises, then firms will increase the pace of their own activity—with additional hiring or longer hours for existing staff—to meet the demand. But doesn't the money have to come from somewhere? No, it doesn't, the Federal Reserve can conjure money up on computers any time it likes. But if we just print money won't we have runaway inflation?

At some point, yes. But right now the inflation rate is well below the levels associated with Ronald Reagan's "Morning in America" recovery or the Clinton boom of the late-1990s and it has been for some time. We could engage in a great deal more monetary expansion before we reach problemas in that regard and because we can engage in monetary expansion we have the capacity to engage in fiscal expansion. And recall that "less unemployment" isn't just a private benefit for the currently unemployed. Employed people produce goods and services for the rest of us to consume. Employed people are our customers and our neighbors, the potential purchasers of the assets we own and taxpayers who contribute to the collective costs of public services.

What Happens If ObamaCare Is Unconstitutional?

The right's opposition to the Brown-Wyden state flexibility concept on the grounds that basically they just want people to have less insurance coverage returns me to the question of why, exactly, conservatives think it's smart conservative policy to engage in root-and-branch opposition to the Affordable Care Act. As Jon Cohn and Kevin Drum point out, the "Bronze" plans envisioned under ACA are pretty similar what conservatives say they want. Similarly, the Obama administration's excise tax on high-cost insurance plans is pretty similar to ideas John McCain campaigned on.

I bring this up not to level an accusation of hypocrisy but just to point out the failure to bargain. If conservatives think the mandatory minimum benefits package in the Affordable Care Act is somewhat too generous, an excellent time to bring this up would have been when Max Baucus was desperately trying to scrounge up some Republican votes for the bill.

Instead, they're putting their eggs in the judicial basket hoping to get the whole thing thrown out of court. But what's the long-term game here? Obviously in the short run, that's a huge loss for progressives. But a couple of nights ago I saw Ron Bailey at a dinner and was reminded of his 2004 Reason article arguing for universal health care via an individual mandate. His key point in trying to sell this idea to libertarians was to observe that as of 2004, the US was slowly slipping down a slope to single-payer health care. That was true then, it was true when Barack Obama got elected, and if the ACA is thrown out in court it'll go back to being true. In fact, it'll be truer than ever. Lots of left-of-center people became convinced during the 2000-2008 period that it wasn't necessary to invest energy in a decades-long crusade for single-payer health care because this alternative approach to universal coverage existed. If the Supreme Court strikes it down, then we'll have been proven wrong, and the single-payer campaigning will begin.

Which is just to say that if conservatives real beef with ObamaCare is that it's a bit too expensive and the minimum benefits package is a bit too generous, then it would really be win-win for them to actually say that and then political bargaining could re-commence.

Is Washington Out Of Touch?

Chris Hayes says DC politicians are too demographically insulated from the jobs crisis:

This manifests itself in our politics in two ways. For one, it just so happens that policy-makers, pundits and politicians are drawn from the classes that are in recovery, and they live in an area where new sushi restaurants are opening all the time. For even the best-intentioned and most conscientious staffers and aides this has, I think, a subconscious effect. Think of it this way: two office buildings are operating side by side in Chicago's Loop in the middle of a brutally cold January day, when the heat in both buildings gives out. The manager of one building has an on-site office, so he finds himself plunged into cold; the other building is managed remotely, from a warm office whose heat is functioning. If you had to bet, you'd guess that the manager experiencing the cold himself would have a bit more urgency in restoring the heat. The same holds for the economy. The people running the country are not viscerally experiencing the depredations of this ghastly economic winter, and they lack what might be called the "fierce urgency of now" in getting the heat turned back on.

I've flirted with this argument myself, but I'm having trouble finding evidence that it's true. Are Republican governors of high-unemployment states calling for federal stimulus but finding that their co-partisans in Washington disagree? Is the bumper crop of new freshman legislators less tainted by this Beltway illness? I don't really see it. I'm happy to agree that DC politicians are massively underrating the need for additional fiscal and monetary stimulus, but as best I can tell so are non-DC politicians and, indeed, so are the voters.

March 3, 2011

Endgame

Like an open book:

— Atmospheric C02 concentrations, an animated history.

— Arne Duncan on collective bargaining and class size.

— Affordable Care Act care is only moderately generous (and rightly so, I might add, better to spend more on other things).

— Medicaid boosts health outcomes.

— Corporate America apparently feels threatened by firms' owners having a say in their management.

— Worth remembering every once in a while that the governor of Florida is a criminal.

Metric does a special iTunes version of "Gimme Sympathy".

Ralph Reeded Confuses Supply and Demand

Former Christian Coalition Executive Director Ralph Reed, who is chairman of the Faith & Freedom Coalition, confidently predicted that the GOP field would end up reflecting the preferences of social conservatives.

"I'm a supply-sider when it comes to politics," Reed said. "Once they see where the supply of voters is and what they care about, they're going to find that they have to have a broad, comprehensive message that encompasses both the cultural agenda and the economic agenda."

This is, of course, a demand-side story.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers