Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2400

March 5, 2011

Does A Fall in Wealth Necessarily Entail a Recession?

To many, the answer is obvious. If home prices suddenly fall, then we're all poorer, and we're all spend less money, resulting in a recession. Empirically, this is in fact what tends to happen. But as this interesting comment from some anonymous economist explains, the actual reason why is considerably more complicated:

Though it's difficult, let me try to explain why this is wrong. Roughly speaking, your spending in a year is a combination of (1) your income and (2) the change in your asset position. When the value of your assets suddenly declines, what are the first-order effects *going forward*? How does the sum of (1) and (2) change? There is no immediate effect on your labor income — surely as the economy finds a new equilibrium, there will be some changes in wages, but there is no clear movement here for most people (except those involved in industries related to the specific assets that declined). So (1) isn't the important part.

As a matter of arithmetic, therefore, the change really has to be in (2). But changes in your asset position are inherently related to intertemporal substitution. Maybe you were counting on your asset stock to last you through retirement, and now you need to save more to achieve a certain net worth by age 65. But, of course, this decision depends on the interest rate. In a completely real economy, your savings will be channeled into investment (or dissaving by other households) because the real interest rate will adjust until the market clears. Maybe aggregate investment will go up and aggregate consumption will go down, but there isn't some obvious first-order effect on GDP. Indeed, the classic "income" effect from a decline in asset prices would be an INCREASE in labor effort.

In an economy where the Fed targets the nominal interest rate, however, it's not quite so simple, unless we're in an environment where inflation immediately adjusts so that the real interest rate goes to its equilibrium value. (We clearly do not live in this world!)

By failing to cut nominal rates (and/or encourage inflation, by altering the expected future trajectory of the nominal rate) so that the real interest rate goes to its equilibrium value, the Fed effectively forces the economy to take some other path toward equilibrium. Generally this involves a massive decline in output.

The important thing to note here is that the rates that matter are the real (i.e., inflation adjusted) ones while the rates the Fed targets are nominal. Since nominal rates can't go below zero, you need to change inflation expectations to avoid the output collapse. Similarly, letting inflation expectations collapse when nominal rates are already low will cause the real rates to become perilously high. All this is a reason to think central banks were flying too close to the sun with their pre-recession inflation targets below 2 percent. This leaves you dangerously exposed to very high real rates if there are any panics in asset markets.

The other thing is that if you imagine a future where we don't have paper money, I think this problem goes away. In an all-electronic currency, you could have negative nominal rates so a central bank should never have a problem targeting whatever real interest rate it wants to target.

Americans Like Israel, Don't Care About Palestinians

Much how the teachers unions' secret weapon is that teachers are really popular, I think advocates of a fairer policy toward Israel and Palestine don't always do a great job of confronting the fact that the AIPAC is so effective primarily because Americans don't care about Palestinians:

Note that this is a real change. Israel has always had more sympathizers than the Palestinians, but pre-9/11 a kind of neutralism was the predominant view. Under those circumstances, lobbying for one-sided policies was pretty challenging. But Israel's commanding position in public opinion over the past decade makes it basically child's play.

Florida Residents Saved From the Scourge of Non-Expert Furniture Selection

Once again the perils of unbridled capitalism have been averted with occupational licensing:

The International Interior Design Association (IIDA) announced "victory for interior design" this week after a regulation found an interior design license requirement to be constitutional. Those challenging the law were unable to prove that the license requirement lacked a rational basis.

As a matter of legal doctrine, this may well be right. The alleged rational basis is that the rule will "protect public safety by ensuring that interior designers are trained to comply with fire and building codes." As a public policy matter, however, it is difficult for me to believe that residents of states without licensing regimes for interior designers are suffering from a major fire-related crisis. After all, the vast majority of interior designing in any state is done by completely untrained amateurs picking out their own stuff.

At any rate, I think the proliferation of this stuff is not only important but is increasing in importance all the time. Robots will be able to make all our manufactured goods long before they're able to execute tasteful interior design, so people need to be able to get employment opportunities in this kind of field.

March 4, 2011

Endgame

Am I wicked? Or am I right?

— Something about cities makes economists forget about prices.

— I ; Beck's decline seems to me to be about partisanship, not about Beck.

— I prefer to think of myself as a logical writer rather than an android.

— What Top Chef gets wrong about student loan regulation.

— Taking seriously.

— Relatively high and rising unionization levels in Canada.

— Scott Walker disapproval rating up to 60 percent in Wisconsin.

Straight outta Madison Wisconsin, it's Rainer Maria "Thought I War"

Jean-Claude Trichet Is History's Greatest Monster

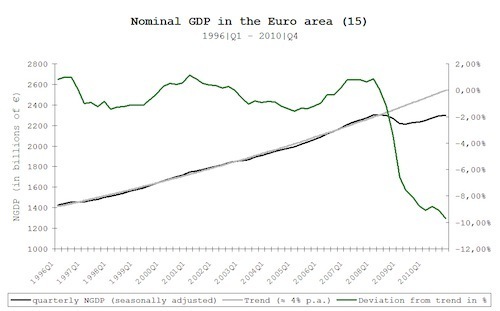

What about this chart says to you "Eurozone demand is too high, I need to tighten policy"?

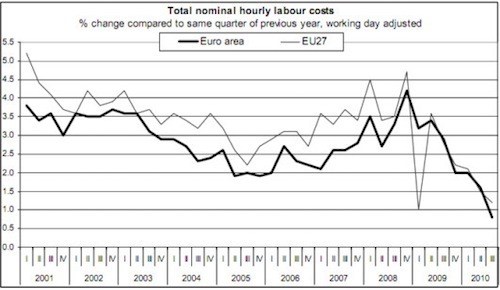

Maybe you can see something in this chart to indicate that inflation is out of control in the Eurozone?

On some level, I think Europe is paying the price for France's desire to have a Frenchman run the ECB. He's acting like a cartoon version of a German inflation hawk. I can imagine an alternate universe in which a German runs the bank and finds himself bending over backwards to dispel suspicion that the Euro contraption is being run for the benefit of German bondholders and totally ignoring the welfare of the majority of Europe's citizens.

ROTC Back at Harvard

Good.

I'm eagerly awaiting "guess I was wrong" posts from all the conservatives who wrote over the years that the university's insistence that student programming conforming to its non-discrimination policy was just a rationalization.

The Power of Specialization

Diane Cardwell has an interesting article about a "coterie of food purists — or Puritans, perhaps" who don't want to customize the food they sell:

At a pea-sized Lower East Side bistro known for its fries, the admonition is spelled out on a chalkboard: no ketchup. At a popular gastropub in the West Village, customers cannot have the burger with any cheese other than Roquefort. And at Murray's Bagels in Greenwich Village and Chelsea, the morning crowd can order its bagels topped any number of ways but never — ever! — toasted.

What I don't understand is why she sees this as some kind of ethical stance, a form of Puritanism. It just seems like specialization. In any line of business you face a tension between the fact that it's more efficient to specialize but you have more customers if you customize.

David Chang explains it perfectly:

"People just assume that every restaurant should be for everyone — I could understand that if we were in a town with, like, 20 restaurants," said David Chang, whose mini-empire of Momofuku restaurants is well known for refusing to make substitutions or provide vegetarian options. "Instead of trying to make a menu that's for everyone, let's make a menu that works best for what we want to do."

Adam Smith observed a few hundred years ago that the division of labor is limited by the extent of the market. If we had cheap teleporters, the extent of the market would be vast and everything would be hyper-specialized. We don't have teleporters, but Manhattan's ultra-density is the next best thing so it's no surprise there's an unusually high level of specialization. I think that this, more than Ed Glaeser's semi-mysterian account, is why denser metropolitan areas are more productive.

Bradley Manning Detention Story Gets Worse

Having decided to detain Bradley Manning without trial in conditions likely to drive a man insane, it seems that at some point the US military had him stripped and left naked in his cell for seven hours on Wednesday. The good news is that his captors have a strong sense of Manning's privacy rights:

"It would be inappropriate for me to explain it," Lieutenant Villiard said. "I can confirm that it did happen, but I can't explain it to you without violating the detainee's privacy."

So thoughtful…

(h/t Mark Kleiman).

Friday Question

A question for discussion, since I think liberals often don't own up to it. Assume you had total control over all things budgetary in the United States. How high would taxes be as a share of GDP? Back pre-recession we got up to a combined state/federal/local spending total of 37 percent of GDP. I take my guide from the Nordic trailblazers and say that you can get taxes up close to 50 percent of GDP if you're willing to adopt a not-so-progressive rate structure but I wouldn't want to try going any higher than that unless some smaller country does it first.

Fannie, Freddie, and Cities

South Korean apartment tower (cc photo by Bitman)

People generally don't realize this but the "standard" American mortgage—a 30 year self-amortizing fixed-rate loan that you can refinance—is a very artificial beast. It's a beast you could create in a number of ways, but the way that we happen to create it is through Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The conservative in the street seems to have gotten it into his head that Fannie and Freddie are primarily vehicles through which Barney Frank gives money to deadbeat black people. In reality, the overwhelming preponderance of what Fannie/Freddie activities are devoted to ensuring the availability of mortgage credit to middle-aged moderately prosperous suburbanites (in other words, Fox News fans and Rush Limbaugh listeners) on more favorable terms than would be otherwise available. Abolishing them would be a big deal with an array of consequences that a lot of people wouldn't like.

But I don't at all understand Paul McMorrow's argument in the Boston Globe that doing so would create a specific shortfall of urban affordable housing:

With the vibrant middle priced out of homeownership, cities become deeply divided places, playgrounds for the privileged surrounded by neighborhoods full of the working, landless poor. Current city and state policies already recognize this as an intolerable outcome. Inclusionary zoning policies and affordable housing development regulations only reach so far, though. Ultimately, the greatest tool in promoting economic diversity in cities is the reliable flow of affordable, long-term housing debt. If that debt dries up, so too will the homebuyers who invest in vibrant urban spaces.

I think this doesn't make sense on a number of levels. Most obviously, the affordability of desirably located real estate in the long run is going to be a function of the extent of new construction. But we're leaving that sermon aside.

Here's the rub. If you didn't have any special credit goodies for residential real estate, the main beneficiaries would be the commercial real estate industry that's already up and running without said goodies. And since multi-family rental apartments are a species of commercial real estate, there'd be no real problem here for cities, where we know the ecology is friendly to that kind of housing. You'd see a huge disruptive impact on suburban single-family detached homes because there's no real existing business model for efficiently operating those kind of structures as rental housing. But cities would have a much easier time adapting.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers