Sandra Beasley's Blog, page 10

April 21, 2014

April Come She Will

The air is finally temperate in DC, so the windows are open warm enough to open the windows. The neighboring crews are working their mowers. I'm snacking on raw walnuts. "April Come She Will" is playing in my head. Not one of the best or best-loved Simon & Garfunkel songs (my favorite is "American Tune") but it has a gentle charm. In the 19th-Century traditional that inspired the song, the subject was a cuckoo--a male--and the nursery rhyme culminated in his August flight. The Simpsons used it in an episode called "Beware My Cheating Bart."

This is not my soup. This is Eduardo C. Corral's soup, who once used to post regularly at Lorcaloca, but who as of late has been a little busy being a rockstar poet and touring for Slow Lightning (if you get the chance to hear him read, do). This is menudo with tripe, but it's only a few degrees removed--switch in pork, add hominy--from the posole that I love, and ate most recently in Santa Fe. Although soup is generally presented as a peasant food, for me it evokes luxury. Luxury of time, to prep and layer ingredients and simmer for hours. Luxury of having a full fridge you can raid for tasty odds and ends. Luxury of not worrying about the inevitable salt bloat to follow. Soup is what I think of eating when I am truly at home.

This is not my soup. This is Eduardo C. Corral's soup, who once used to post regularly at Lorcaloca, but who as of late has been a little busy being a rockstar poet and touring for Slow Lightning (if you get the chance to hear him read, do). This is menudo with tripe, but it's only a few degrees removed--switch in pork, add hominy--from the posole that I love, and ate most recently in Santa Fe. Although soup is generally presented as a peasant food, for me it evokes luxury. Luxury of time, to prep and layer ingredients and simmer for hours. Luxury of having a full fridge you can raid for tasty odds and ends. Luxury of not worrying about the inevitable salt bloat to follow. Soup is what I think of eating when I am truly at home.

For much of later March and early April, I was not at home. (Hence the silence here. I missed you!) This is snapshot from a dawn flight out of Memphis.

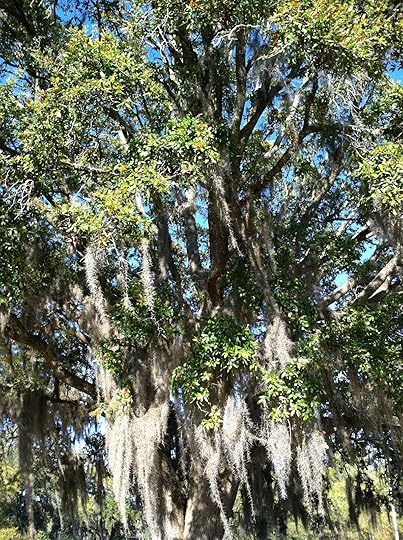

Thanks to the Georgia Poetry Circuit, one of the best opportunities I've ever had as a writer, I read in Bainbridge, Columbus, Macon, Valdosta, and Statesboro. Five towns, five days. The rampant Spanish moss was a reminder that I was in a place from another time. A state rife with conservatism--one GPC coordinator jokingly called his town the "pulsing red heart" of an already-red state--but also a lot of kindness and creativity.

Thanks to the Georgia Poetry Circuit, one of the best opportunities I've ever had as a writer, I read in Bainbridge, Columbus, Macon, Valdosta, and Statesboro. Five towns, five days. The rampant Spanish moss was a reminder that I was in a place from another time. A state rife with conservatism--one GPC coordinator jokingly called his town the "pulsing red heart" of an already-red state--but also a lot of kindness and creativity.  Also, some epic houses.

Also, some epic houses.

…including the home of Carson McCullers (The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter). I gave an extemporaneous lecture to a crowded living room of students on the art of revision, manuscript strategies, and the writing life. I slept in her basement.

…including the home of Carson McCullers (The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter). I gave an extemporaneous lecture to a crowded living room of students on the art of revision, manuscript strategies, and the writing life. I slept in her basement.

Columbus was my favorite stop because of its utter surprises, which included a studio visit with the artists Bo Bartlett and Betsy Eby. All I knew about Columbus beforehand was its proximity to Fort Benning. I came away so impressed with the efforts to revitalize the downtown, including the decision to convert old mills to artist and loft spaces, and to open up a dam that transformed the Chattahoochee River's flow, for the 10 miles adjacent to the Riverwalk, into a whitewater passage open to the public.

Columbus was my favorite stop because of its utter surprises, which included a studio visit with the artists Bo Bartlett and Betsy Eby. All I knew about Columbus beforehand was its proximity to Fort Benning. I came away so impressed with the efforts to revitalize the downtown, including the decision to convert old mills to artist and loft spaces, and to open up a dam that transformed the Chattahoochee River's flow, for the 10 miles adjacent to the Riverwalk, into a whitewater passage open to the public.

Several times over the years, folks have recommended One Flew South as a transformative airport restaurant experience. So--faced with a layover in Atlanta--I opted for a longer stretch instead of my usual 30-minute sprint between gates, and tracked OFS down in Terminal E. Folks were right! The conversation flowed as if we were all regulars, trading stories and cracking jokes. I don't know which was tastier: my lychee-sake cocktail, or the off-menu "Brown-eyed Girl" of bourbon with a float of malbec (yes, really), or the hamachi-pickled-pear hand roll, or the chicken soup with five spice. But I will never again dread the Atlanta airport.

Several times over the years, folks have recommended One Flew South as a transformative airport restaurant experience. So--faced with a layover in Atlanta--I opted for a longer stretch instead of my usual 30-minute sprint between gates, and tracked OFS down in Terminal E. Folks were right! The conversation flowed as if we were all regulars, trading stories and cracking jokes. I don't know which was tastier: my lychee-sake cocktail, or the off-menu "Brown-eyed Girl" of bourbon with a float of malbec (yes, really), or the hamachi-pickled-pear hand roll, or the chicken soup with five spice. But I will never again dread the Atlanta airport. This may seem an odd pronouncement coming off such pleasurable travels, but I've been considering a more traditional job. Not because of financial hardship; although freelancing is not an easy life, I've had a fortunate stretch of opportunities and windfalls this year. But when I consider what comes after Count the Waves, I'm drawn to strange ideas--personal and scholarly--things that on first draft will probably seem like a mistake. I'd like to provide shelter for those ideas to grow. I worry about losing something in the trade, of course. But so much unhappiness is rooted in resistance to change. The jobs I'm considering are dear to my heart and my skill set. And, frankly, even the best soup at One Flew South will never compare to the one I have time to make in my own home. I'm only 33. There will be so many ways to live this life.

Published on April 21, 2014 12:17

March 25, 2014

On Lyric Essays

There's a vase of daffodils on my table, and snow on the ground outside: welcome to DC's confused, confusing spring. One of my students in the University of Tampa's low-residency MFA program is interested in using the "lyric essay" as a drafting mode. In rounding up resources to help her out, I thought I'd share my findings here as well.

To begin, where does the term originate? Although both "lyric" and "essay" are concepts visited by generations of many writers past, the coinage conflating the two appears definitively in a 1997 issue of the Seneca Review. In an introduction, editor Deborah Tall and associate editor John D'Agata elaborated on the phrase this way:

The recent burgeoning of creative nonfiction and the personal essay has yielded a fascinating sub-genre that straddles the essay and the lyric poem. These "poetic essays" or "essayistic poems" give primacy to artfulness over the conveying of information. They forsake narrative line, discursive logic, and the art of persuasion in favor of idiosyncratic meditation.

The lyric essay partakes of the poem in its density and shapeliness, its distillation of ideas and musicality of language. It partakes of the essay in its weight, in its overt desire to engage with facts, melding its allegiance to the actual with its passion for imaginative form.

The lyric essay does not expound. It may merely mention. As Helen Vendler says of the lyric poem, "It depends on gaps. . . . It is suggestive rather than exhaustive." It might move by association, leaping from one path of thought to another by way of imagery or connotation, advancing by juxtaposition or sidewinding poetic logic. Generally it is short, concise and punchy like a prose poem. But it may meander, making use of other genres when they serve its purpose: recombinant, it samples the techniques of fiction, drama, journalism, song, and film.

Given its genre mingling, the lyric essay often accretes by fragments, taking shape mosaically - its import visible only when one stands back and sees it whole. The stories it tells may be no more than metaphors. Or, storyless, it may spiral in on itself, circling the core of a single image or idea, without climax, without a paraphrasable theme. The lyric essay stalks its subject like quarry but is never content to merely explain or confess. It elucidates through the dance of its own delving.

I would summarize thus: The lyric essay values the tension of juxtaposing objective and subjective material. The lyric essay emphasizes language as a means of engagement, equal to or exceeding its value in conveying information. The lyric essay does not emphasize argument or traditional closure.

Since I published first in the genre of poetry, then in nonfiction, I am sensitive to the explanation the lyric essay is merely a compromise or indulgence--a "poet's version of prose." It's true that in moments when others report, poets meditate. Poets such as Sarah Manguso and Nick Flynn have written masterpieces of the lyric memoir. But that's a choice, not a default. Plenty of poets have written cogent, journalistic pieces or chronologically coherent personal essays over the years.

So why turn to the lyric essay? On a pragmatic level, these are some circumstances in which the lyric essay might prove advantageous:

-The essay concerns a personal episode in which the author lacked power. Lyric moves, particularly fragmentation and passive voice, enact a lack of agency on the page.

-The goal is to use a received form or numerical formula, e.g. The Twelve Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous or the Five Stages of Grief, and comment on its efficacy.

-The author does not have access to sources for key aspects of the traditional "story." Lyric moves, particularly litany and stimulative truth, bridge these troublesome gaps.

-The language and images are the driving motivation of the piece, and stream-of-consciousness observation, sacrificing traditional narrative, is the only way to go.

And there's the simple--not to be underestimated--sway of aesthetic appeal. Lyric essays offer a space in which an author can weigh a topic without passing judgment. The critical thing is that adopting the mode not be seen as a kind of "almost poem," nor a "pseudo-essay." I like Lia Purpura's take in this interview for Smartish Pace:

Laura Klebanow: It seems you came to write poetry first, and prose poetry and essays next. Is this correct, or has your work in each genre developed less compartmentally? For example, do you ever start a poem and watch it become a prose poem or essay, or vice versa?

In the last fifteen years, lyric essays have come to be more accepted in mainstream publishing, and as they have become a more frequent sight at the workshop level. Subsequently, teachers and editors have developed a vocabulary surrounding their craft. These are some of the models I consider most useful when recognizing a lyric essay:

Lia Purpura: The issue of how one discernible genre grows from another is utterly mysterious to me. I’m certain that I’m writing prose, though my essays are called “lyric essays.” In fact, I’ve just written an essay titled “What is a Lyric Essay?” for Seneca Review. In it, I’m making a plea for allowing the form to remain as mysterious as possible. I do mean “mysterious” though in the best way – challenging and magical and able to work on a reader and knit up above the page. I don’t mean at all “unclear” or “sloppy”. The language ought to be as precise as possible in order to affect the most unlikely moves. When I’m writing, an impulse makes itself known as a prose itch or poem-itch. Some failed poems have extended out into prose and found their musculature that way. I don’t think a derailed essay has ever turned itself into a poem.

-The Collaged Essay - Collages embody an emotional or historical experience on the page, without unifying explanation. This type of lyric essay may freely incorporate images, poems, maps, or other multimedia modes, including ones "found" elsewhere, e.g. Reality Hunger by David Shields. Asterisks are often used to denote sections.

-The Braided Essay - Unrelated topics, perhaps set in different eras, develop toward a common theme. Brenda Miller's "A Braided Heart: Shaping the Lyric Essay" is an apt explication. I like her analogy to french braids, in which patterning renders slippery, homogenous materials--e.g, strands of hair--more interesting by adding texture.

-The Hermit Crab Essay - An author responds to an external cultural product (a well loved album), but gradually reveals an internal landscape (the relationship that corresponded to that album). As Dave Hood says, "This type of lyrical essay is created from the shell of another." These essays are sometimes masked as reviews.

Not every lyric essay aligns with one of these models, but they capture trends. I would add that lyric essays tend to be particularly rich in litany, parallel structure, and what I call "stipulative truths," which include imperative commands or invented tableaus.

Below are some favorite or oft-cited examples of authors working in the mode of lyric essay. I'd recommend them to any student looking to assemble their toolbox.

- Michael Martone's "More or Less: the Camouflage Schemes of the Fictive Essay" - This essay toggles between iterations of camouflage and Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse-Five; the sections are described as being in "arbitrary order" and in a signature move, the author's bio is a contributing creative text.

- Priscilla Long's "Genome Tome" - This essay uses a received form (the 23 pairs of chromosomes that make up a typical DNA strand) to structure Long's mediation on personal and inherited identity, weaving in scientific case studies.

- László Krasznahorkai's " Someone’s Knocking at My Door" - This essay uses a circular structure, with slippage between observer and observed, to enact the state of anxiety or, as he put it, the "terrible meeting between boorishness and aggressiveness."

- Maggie Nelson's Bluets - This book-length work itemizes meditations on "blue" as a color, a term, even a musical mode, looking across cultures and time periods.

- Eula Biss's "The Pain Scale" - This essay uses a visual construction (advancing from 0 to 10) to pace her exploration of suffering; Biss spikes a particular domestic setting with outside references to Anders Celsius, Dante, and Galileo Galilei.

- Kiese Laymon's "How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America: A Remembrance" - This essay juxtaposes the author's own experiences against news stories of black youths killed under questionable circumstances; note the rhythmic use of standalone sentences, defiant of normal paragraph organization.

- Ander Monson's Vanishing Point: Not a Memoir - This book-length work interrogates the privilege of fact versus fiction; Monson's website complicates the notion of "reading" as a linear act, and includes the wonderful "Essay as Hack."

- Jenny Boully's The Body - This book-length work's text is posited entirely via footnotes that might take the form of assertions, postcards, Mad Libs, and so on.

- Roxane Gay's "What We Hunger For" - This essay opens in response to The Hunger Games before accessing a harrowing, firsthand experience of gang rape.

- David Foster Wallace's "Ticket to the Fair" - This essay's structure is a variant on journalistic chronology, but what distinguishes it is the extravagances of DFW's attention; he freely telescopes between minute details and vast cultural intuitions.

Subsequent proponents of the form have not always agreed with the terminology. At the most recent AWP Conference in Seattle, Kathleen Rooney argued for the phrase "Open Form Essay." In a 2012 Black Warrior Review interview, Maggie Nelson resisted the label in part because of its connotations with "pretty" writing:

BWR: You are a writer that is often associated with the Lyric Essay. I find that term to be quite useful, but I’ve come to realize that many people use that term to mean wildly different things. Do you use Lyric Essay to describe your, or other’s, writing? If so, how do you characterize it?

MN: I don’t use it to describe my work, because I’ve never written anything that I thought of explicitly as an essay. (I’m trying to write more essay-like things now – it’s very different, and I don’t really have a clue how to do it.) On the other hand, I conceived of both my books The Red Parts and Bluets as continuous flows, albeit jagged up into titled or numbered pieces, and so treating them each as one long essay also seems kind of right. I don’t mind if anyone calls my work “lyric essay”; I don’t care much about classification, as it comes after the fact of the writing. “Lyric essay” likely covers a lot of writing that I like, but honestly, and I’m just speaking personally here, the words themselves kind of bug me. They make it sound like the pieces have to be self-contained and pretty, song-like. Whereas some of the work I like the most is more chafing, awkward—ugly, even. And sometimes sprawling—think of Wayne Koestenbaum’s recent Anatomy of Harpo, for example. That’s why I usually stick with the broader, albeit pretty boring, moniker, “creative nonfiction.”

It might be counterintuitive to include a quotation that questions the very usefulness of the phrase. But "lyric essay" is admittedly a fledgling term. In the absence of rules, the author of lyric essays must summon more self-discipline, not less. Each word choice counts, because you've asked your reader to be primed for every conceivable motif, pattern, tense shift, found text, or other linguistic switcheroo. Traditional indicators of priority on the page have been stripped away. I'm wary of the lyric essay draft in which stylistic meandering is costumed as "figuring it out." That's laziness. Even if the writing suspends judgment, the writer must have clarity in his or her understanding.

Do we need this term? One of the clearest distinctions between poetry and prose, in my mind, has always been that prose is assigned a truth value--fiction or nonfiction--while poetry is not categorized in such terms. Does attaching the "lyric" modifier shift our expectations, allowing the essay to straddle truth values? Can an essay contain fictional conventions, or does that mean it has become a short story, albeit one rooted in fact? (Readers of John D'Agata's The Lifespan of a Fact or John Jeremiah Sullivan's Pulphead might find this a resonant question.)

Is a blurring of reportable fact the inevitable consequence of emphasizing the lyric?

I'm fascinated by the texture of truth, the way we establish authenticity and authority on the page. Regardless of whether the "lyric essay" is taught one hundred years from now, the term is a potent description of contemporary American aesthetics toward the last two decades of personal writing and, I suspect, for at least the next decade to come. All the writers mentioned above are worth your time, consideration, and consternation. I'll leave it at that; these are just some notes toward a larger discussion.

Published on March 25, 2014 23:43

March 11, 2014

On Wonder

My cousin-once-removed Charles H. Swift passed away on Friday. When he retired back in 2002, he'd been a teacher for 35 years, much of it spent as a beloved teacher in the Lubbock Independent School District. In these final weeks of his illness, I loved seeing the parade of student tributes on his Facebook page, and the snapshots (such as this one) contributed by colleagues on the countless trips Charles led to any of the 68 countries he visited.

My cousin-once-removed Charles H. Swift passed away on Friday. When he retired back in 2002, he'd been a teacher for 35 years, much of it spent as a beloved teacher in the Lubbock Independent School District. In these final weeks of his illness, I loved seeing the parade of student tributes on his Facebook page, and the snapshots (such as this one) contributed by colleagues on the countless trips Charles led to any of the 68 countries he visited. We spoke for the last time on a January snowy night while I was at the Millay Colony, dependent on the static-ridden land line stretching the miles to his Texas hospital room. He told me to visit the Walter Anderson Museum in Ocean Springs, Mississippi; he teased me for not having my New York Times piece in print already ("I'm on kind of a tight timeline, here," he said, chuckling). In another world, we could have been very close; it's odd to realize he'd dedicated his life to fostering the exact kind of nerd-child I grew to be in northern Virginia, attending Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology. He always brought around his rock collection, his carved-wood canes and pens; at my grandmother's funeral, he told stories about smuggling snakes. He will be missed. It is what it is, and he departed this earth knowing he was deeply loved. That said, these losses are irreversible, and I haven't felt like being on the internet as of late.

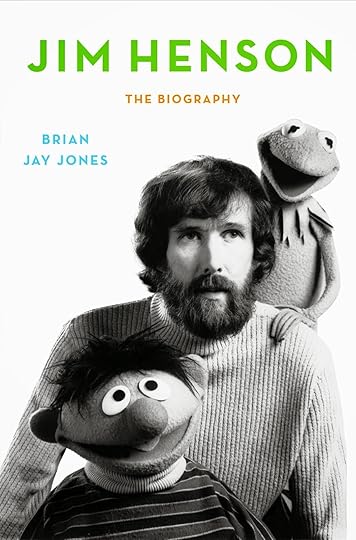

But oh, a reason--a reason Charles would love--looms: I gotta tell you about this thing coming up. On Tuesday, March 18, I am bringing Brian Jay Jones to the Arts Club of Washington, to talk about his biography of Jim Henson. Yes, THE Jim Henson, a.k.a., the man who gave us the best characters of Sesame Street, The Muppets Show, The Fraggles, Dark Crystal, and so on. A man who said, “The most sophisticated people I know--inside they are all children." A man who actually got his start while a teenager in Hyattsville, Maryland, showcasing his young imagination on Washington-area stations (Jones will be sharing rare, archival video clips). Brian's behind-the-scenes journal of writing the biography, posted here, reveals a sensibility that is funny, humble, and very attentive to detail, all of which is reflected in this incredible book. I can't imagine a better event to raise your spirits or mine. This event starts at 7 PM

(details here),

and is free and open to the public; please join us, and spread the word. The Arts Club is at 2017 I Street NW DC, convenient to metered street parking. See you there?

But oh, a reason--a reason Charles would love--looms: I gotta tell you about this thing coming up. On Tuesday, March 18, I am bringing Brian Jay Jones to the Arts Club of Washington, to talk about his biography of Jim Henson. Yes, THE Jim Henson, a.k.a., the man who gave us the best characters of Sesame Street, The Muppets Show, The Fraggles, Dark Crystal, and so on. A man who said, “The most sophisticated people I know--inside they are all children." A man who actually got his start while a teenager in Hyattsville, Maryland, showcasing his young imagination on Washington-area stations (Jones will be sharing rare, archival video clips). Brian's behind-the-scenes journal of writing the biography, posted here, reveals a sensibility that is funny, humble, and very attentive to detail, all of which is reflected in this incredible book. I can't imagine a better event to raise your spirits or mine. This event starts at 7 PM

(details here),

and is free and open to the public; please join us, and spread the word. The Arts Club is at 2017 I Street NW DC, convenient to metered street parking. See you there?I can't even wrap my arms around how much I love the Muppets; their bright colors, their silly songs, their bodies at once specific and abstract, their unapologetic curiosity, and O yes, their sense of wonder. There was never a sense, behind the puppet or in the moment, of talking down to one's audience--even when skimming across the surface of a vast pool of knowledge and humor. And that makes me think of Charles H. Swift.

Published on March 11, 2014 11:52

February 25, 2014

Seattle-Bound Confessions

Like so many writers, I am making my way to Seattle for the 2014 AWP Conference, where I'll be taking part in Thursday night reading for The Incredible Sestina Anthology and sitting in on a Friday noon panel "Verses Versus Verses," on poetry contests. I'd love to see you at either event, or on the book fair floor, or at one of these seafood restaurants, or over one of the cocktails described on Leslie Pietrzyk's blog. If your dance card is already filled and we don't see each other, just have a good time per the advice of Kelli Russell Agodon, hydrate and navigate per the wise words of Roxane Gay, and treat your hotel staff right.

It's been fun seeing everyone report what they're doing, on Facebook and elsewhere, but there hasn't been enough attention to those plans where we're simply excited to be in the audience. This year's official event schedule has some pleasing variances--discussion of writing for YA and children's audiences, the graphic novel or comic as literary work, and a spotlight on Pacific Northwest literature, including indigenous voices and Hawaiian writers. Check 'em out. Panels on the influence of Kurt Cobain and Bob Dylan? Yes. In venturing to off sites, be sure to support Elliott Bay Book Company and the Richard Hugo House; since the latter is closed on Sunday, my free day to explore, I'm going to try and make it by for the VIDA reading on Friday night.

I've only been to Seattle once before, when I was in my mid-twenties and working for a nonprofit that held its annual conference there. One of my jobs was to coordinate a set of awards that had been received by, among others for that year, Robert Pinsky. I'd studied The Sounds of Poetry. He was a former Poet Laureate. He'd been a voice on The Simpsons, for goodness's sake! What greater fame is there? I was so excited to meet him. About a half-hour before events were supposed to start, my hotel room phone rang, and I learned my father--on the other side of the country--was hospitalized with a collapsed lung, larger cause to be determined.

I've only been to Seattle once before, when I was in my mid-twenties and working for a nonprofit that held its annual conference there. One of my jobs was to coordinate a set of awards that had been received by, among others for that year, Robert Pinsky. I'd studied The Sounds of Poetry. He was a former Poet Laureate. He'd been a voice on The Simpsons, for goodness's sake! What greater fame is there? I was so excited to meet him. About a half-hour before events were supposed to start, my hotel room phone rang, and I learned my father--on the other side of the country--was hospitalized with a collapsed lung, larger cause to be determined.

So. I arrived late to the proceedings; as the only poet on staff, I was the only one qualified to spot Mr. Pinsky, who had wandered the crowd, unrecognized and sans name tag or welcoming glass of wine; when I finally got to him, I had nothing better to attach his name tag than a loose paper clip from my purse; the envelope I gave him had the wrong check, made out to one of the other award recipients; I gave him a book to sign--his translation of The Inferno--forgetting I had gotten the copy from a poetry teacher past when he cleaned out his university office. That led to the awkward question "Why is [X]'s name inscribed in my book?"

This is not an AWP fairy tale. There was no networking, only profuse apologies. I revisited these a few years later, when I met him again in the context of a different award. (He had just been on The Colbert Report…the man is popular TV magnet.)

That next morning, right back to work at 8 AM. That night, I ventured to Pioneer Square to distract myself. He played bass.

My last morning in town, I went to Pike's Place Market and spent $50 on a huge bouquet, the most I had ever spent for flowers: all of my remaining cash I'd saved for the trip. For my dad. I flew the six hours back to DC with them balanced on my lap.

Not going to Seattle this week? Not a big deal. AWP is a wonderful resource, but an annual professional conference is not the end-all. (The proof is that Tayari Jones is skipping it, and has been for a few years running.) I do recommend is soul-baring trips in your life, 4-5 days when you're pushed to some type of limit, times when the knife scrapes to the bone of ego and you ask--Wait, what? And when the world does not wait: What am I doing? Why am I doing it? That is AWP, for some. But a square is a rhomboid; a rhomboid is not a square. Whatever excursion defines you, tests you, and liberates you, is a lot more important than the abstract of AWP ever could be.

It's been fun seeing everyone report what they're doing, on Facebook and elsewhere, but there hasn't been enough attention to those plans where we're simply excited to be in the audience. This year's official event schedule has some pleasing variances--discussion of writing for YA and children's audiences, the graphic novel or comic as literary work, and a spotlight on Pacific Northwest literature, including indigenous voices and Hawaiian writers. Check 'em out. Panels on the influence of Kurt Cobain and Bob Dylan? Yes. In venturing to off sites, be sure to support Elliott Bay Book Company and the Richard Hugo House; since the latter is closed on Sunday, my free day to explore, I'm going to try and make it by for the VIDA reading on Friday night.

I've only been to Seattle once before, when I was in my mid-twenties and working for a nonprofit that held its annual conference there. One of my jobs was to coordinate a set of awards that had been received by, among others for that year, Robert Pinsky. I'd studied The Sounds of Poetry. He was a former Poet Laureate. He'd been a voice on The Simpsons, for goodness's sake! What greater fame is there? I was so excited to meet him. About a half-hour before events were supposed to start, my hotel room phone rang, and I learned my father--on the other side of the country--was hospitalized with a collapsed lung, larger cause to be determined.

I've only been to Seattle once before, when I was in my mid-twenties and working for a nonprofit that held its annual conference there. One of my jobs was to coordinate a set of awards that had been received by, among others for that year, Robert Pinsky. I'd studied The Sounds of Poetry. He was a former Poet Laureate. He'd been a voice on The Simpsons, for goodness's sake! What greater fame is there? I was so excited to meet him. About a half-hour before events were supposed to start, my hotel room phone rang, and I learned my father--on the other side of the country--was hospitalized with a collapsed lung, larger cause to be determined.So. I arrived late to the proceedings; as the only poet on staff, I was the only one qualified to spot Mr. Pinsky, who had wandered the crowd, unrecognized and sans name tag or welcoming glass of wine; when I finally got to him, I had nothing better to attach his name tag than a loose paper clip from my purse; the envelope I gave him had the wrong check, made out to one of the other award recipients; I gave him a book to sign--his translation of The Inferno--forgetting I had gotten the copy from a poetry teacher past when he cleaned out his university office. That led to the awkward question "Why is [X]'s name inscribed in my book?"

This is not an AWP fairy tale. There was no networking, only profuse apologies. I revisited these a few years later, when I met him again in the context of a different award. (He had just been on The Colbert Report…the man is popular TV magnet.)

That next morning, right back to work at 8 AM. That night, I ventured to Pioneer Square to distract myself. He played bass.

My last morning in town, I went to Pike's Place Market and spent $50 on a huge bouquet, the most I had ever spent for flowers: all of my remaining cash I'd saved for the trip. For my dad. I flew the six hours back to DC with them balanced on my lap.

Not going to Seattle this week? Not a big deal. AWP is a wonderful resource, but an annual professional conference is not the end-all. (The proof is that Tayari Jones is skipping it, and has been for a few years running.) I do recommend is soul-baring trips in your life, 4-5 days when you're pushed to some type of limit, times when the knife scrapes to the bone of ego and you ask--Wait, what? And when the world does not wait: What am I doing? Why am I doing it? That is AWP, for some. But a square is a rhomboid; a rhomboid is not a square. Whatever excursion defines you, tests you, and liberates you, is a lot more important than the abstract of AWP ever could be.

Published on February 25, 2014 16:45

February 13, 2014

Pandora (on Animals in Poetry)

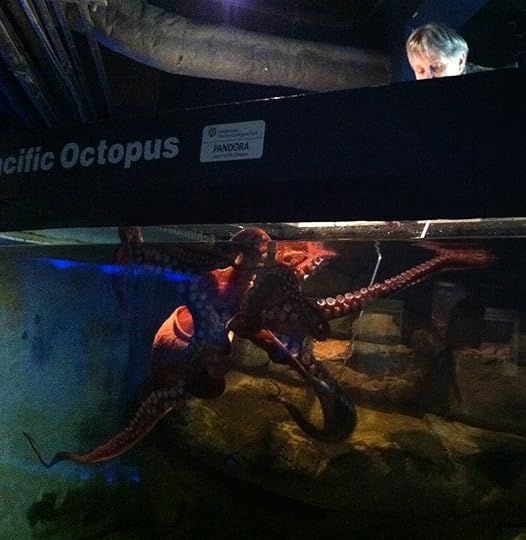

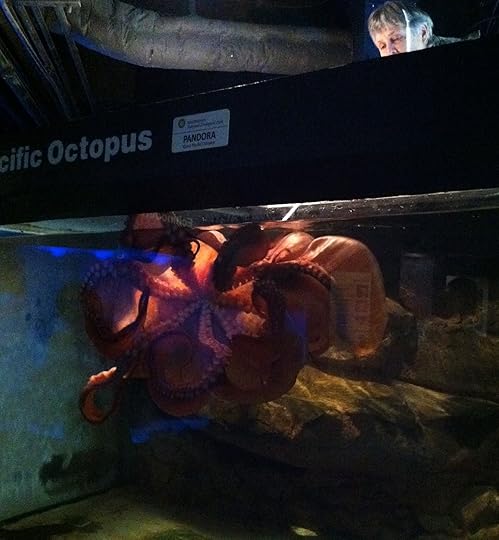

Last night, as the snow fell and kept falling here, I read in the Washington Post that Pandora has died. She was a matriarch of our National Zoo's invertebrate exhibits, all 15 pounds of her, all 7.8-foot arm span. Her death was not unexpected--she'd been sluggish and, at five years old, was approaching old age for an octopus. But she'll be missed. Her rosy pink hue and outgoing manner charmed everyone. Including me, who went to watch her feed on a chilly Thursday in November 2012. That was an unusual detour from my usual stops to the aviary and the cheetah enclosure. It was exactly a week after Thanksgiving, my first week of being engaged. No ring. We hadn't told anyone yet. It was our secret.I stood with my hands jammed into the pockets of my black shearling coat, not sure what to expect. The keeper speared a bit of scallop meat on a long wire and dangled it in the water, wiggling it to make it lively. Pandora approached.

Last night, as the snow fell and kept falling here, I read in the Washington Post that Pandora has died. She was a matriarch of our National Zoo's invertebrate exhibits, all 15 pounds of her, all 7.8-foot arm span. Her death was not unexpected--she'd been sluggish and, at five years old, was approaching old age for an octopus. But she'll be missed. Her rosy pink hue and outgoing manner charmed everyone. Including me, who went to watch her feed on a chilly Thursday in November 2012. That was an unusual detour from my usual stops to the aviary and the cheetah enclosure. It was exactly a week after Thanksgiving, my first week of being engaged. No ring. We hadn't told anyone yet. It was our secret.I stood with my hands jammed into the pockets of my black shearling coat, not sure what to expect. The keeper speared a bit of scallop meat on a long wire and dangled it in the water, wiggling it to make it lively. Pandora approached.

Once she was confident of her prey, she began to waft the loose folds of skin between each tentacle, billowing her body wider and wider.

As her skin stretched, it whitened, and the bait disappeared from sight. If it had been a crab or fish, it would have had no hope of escape.

It was utter. And then she returned to her leisure, sprawling out to eye us, showing off the 250+ tentacles on each arm.

Some years back, I wrote a poem called "In the Deep," inspired by a trip to the National Aquarium--a dank, grim, undernourished and underground box of sad-looking sea creatures--down on 14th Street. I had recently read an article on giant octopi that talked about their intelligence, their skill as escape artists. At the aquarium, I eavesdropped on some raucous kids, bored on a Saturday, looking for anything worthy of their attention. "In the Deep" appeared first in

Hayden's Ferry Review

, then in

I Was the Jukebox

. IN THE DEEP

Some years back, I wrote a poem called "In the Deep," inspired by a trip to the National Aquarium--a dank, grim, undernourished and underground box of sad-looking sea creatures--down on 14th Street. I had recently read an article on giant octopi that talked about their intelligence, their skill as escape artists. At the aquarium, I eavesdropped on some raucous kids, bored on a Saturday, looking for anything worthy of their attention. "In the Deep" appeared first in

Hayden's Ferry Review

, then in

I Was the Jukebox

. IN THE DEEP The boys are fifteenand fuckwild:

Fuck the glass fish, they say, bodies pulsing with injected neon;fuck the nautilus, nursing its bubble of salted air.

What they love is this crumple of muscle suctioned to the tank’s darkest corner—

Fuck her blue rings.Fuck her three hearts.

The octopus cradles a baby doll, the doll’s head stuffed with krill. Fuck yeah, they say, watching

as she pokes one eye out, then the other.

#

I'd write a different octopus poem today. That's not to disown "In the Deep," but simply to admit that the heart notices different things at different times. Did you know that a mothering female strings together 20,000 to 100,000 eggs? Once she has laid them, she doesn't eat in the seven months that lead to their hatching. She cleans them, she aerates them, she broods, and shortly after their birth, she dies.

Pandora never mated in DC's captivity. She released her eggs in April 2013, unfertilized. According to the article, each would have been the size of a grain of rice.

There is a long tradition of animals being the subject of poems. In addition, there is a specific cohort of female poets--poets of my generation--who invoke creatures as tangible actors or omens in their first and second books. I'd argue that we do this at an unusually higher proportion or frequency. I'm thinking of myself, Aimee Nezhukumatathil, Paula Bohince, Traci Brimhall, and Rebecca Hazelton among others. These works are otherwise interested in the psychic interior, works where I'd argue the driving urge is to share something about one's own relationship to the world. (Maybe that's overstating the point, because isn't poetry always about such an urge? Still.) So we point to bright particulars of these beasts as if to guard against the accusation of being self-involved; or, to prove our abilities as biologists and zoologists; or, simply for the pleasure of those particulars. We resist the confessional even as we flirt with it.

There is a long tradition of animals being the subject of poems. In addition, there is a specific cohort of female poets--poets of my generation--who invoke creatures as tangible actors or omens in their first and second books. I'd argue that we do this at an unusually higher proportion or frequency. I'm thinking of myself, Aimee Nezhukumatathil, Paula Bohince, Traci Brimhall, and Rebecca Hazelton among others. These works are otherwise interested in the psychic interior, works where I'd argue the driving urge is to share something about one's own relationship to the world. (Maybe that's overstating the point, because isn't poetry always about such an urge? Still.) So we point to bright particulars of these beasts as if to guard against the accusation of being self-involved; or, to prove our abilities as biologists and zoologists; or, simply for the pleasure of those particulars. We resist the confessional even as we flirt with it. I recognize this trend without judgment, because even within it there are strong poems and weak poems, variance, individual voices. But I notice it, and I'd love to sleuth out its origins. In the post-confessional morass, is it an issue of agency--do we more easily give ourselves permission to project character onto animals than we would fellow humans? Do humans seem, in fact, a little boring by comparison? Did Disney forever change out perception of an animal's capacity to think, feel, and love? Did Elizabeth Bishop wave her magic wand above our heads? Would we have been another generation's nature writers? No answers here on this quiet day, only questions.

The octopus was a namesake of Earth's first woman, crafted from clay. Pandora was endowed by the gods with all the gifts--beauty, cunning, mastery of music and art, and as a curse, curiosity. Despite her husband's advice she took the top off the vessel, sent by Zeus, that released the world's plagues and worries.

Watching Pandora that feed that day at the zoo, I pictured what it would look like if a woman tried to catch all those ills, to swallow them back inside herself. She'd have to balloon, stretching herself so thin her skin changed color, turning her body into a ladle to scoop through the sea and air. Not that it'd be her job. But she'd try anyway.

Published on February 13, 2014 12:54

January 25, 2014

The Books We Don't Write

I'm at the Millay Colony, getting snowed in; that's Edna's barn in the distance. On the long drive up, I talked on the phone with the woman who gave me the month off in 2006 that first brought me here and yielded Theories of Falling. Once boss, now mentor, she was giving me advice toward the year ahead.

When I open up the folder of drafts from September 2006, I find--in the unpublished slush, the also-rans--three poems in which wasps build a piñata nest around the speaker's heart. That was a metaphor I was relentlessly attached to, both in life and on the page. I also found this one, laced with the details of Hudson:

GETTING LOST

The best towns are the ones big enough for fireworks, small enough to hold under the roof of your mouth;I saunter down Route 9H past the corn, past the silo

drooling its long red chute, past the sunny faces of gravestones claiming Fraternity of Polish Sportsmen, past the library, a church, a jailhouse—here the road

calls itself Columbia—past a park with bronzed general, a gallery, a cop, the woman selling squash and eggplant while her daughter ties daisies around every parking meter.

I find the pub with an adjective-name, there’s always one: The Spotted Dog, The Blue Clover, now The Muddy Mug, then order a draft of something dark and throaty.

The man wipes the counter, lays down my napkin.Here’s where I might begin to flirt, might make myselfat home—except this one looks up with your eyes—

Green. Wide-set. His nose thinner, his hair wiry, but all I see is a boy who would hunch by a deep well,tossing stones just to hear them hit bottom. He’d do this

for hours, for weeks, for years. Once I kissed your hands, swallowed your hours, said I was full. Almost believed it. Miss, do you want—but I’m already settling up. The best towns

are only thirty miles back to main road, an hour to your life. If you get lost don’t trust your gut. The gut’s no navigator. Your feet know where to find your shoes; your arms

reach for familiar sleeves. But your gut will drive forever, if you let it, looking for the town that makes it turnand turn, the one that never needed you in its limits.

#

I wonder if those are the same green eyes that appear in "You Were You"? Maybe. We bank these images into our memory, and they stay with us forever.

It had been way too long since I'd curled up with a book, so my reading appetite here has been voracious. What I've most enjoyed is Ann Patchett's collection of essays, This is the Story of a Happy Marriage. Though she's already racked up 10 books at the age of 50 (!), we get a glimpse of a book that Patchett didn't write, both in terms of references to an abandoned project as part of her life narrative and an essay, "The Wall," which describes a summer's efforts to pass the training tests for the Los Angeles Police Department. That would have been the nucleus of experience, joining the force to create an immersive portrait of the LAPD. But as Patchett discovers in real time, for all his inspiring enthusiasm her father (a former police captain) didn't really want to be on the record in the way that's necessary for a book, and getting to know her truly dedicated fellow recruits made the experiment seem disingenuous. So she let it go.

I'm immensely relived to see someone like Patchett admit this. I look up to her--her frank personal manner, the balance of freelance and fiction writing she uses to support herself, the ways she manages (as captured in these essays) to stay rooted in a local community even amidst traveling, traveling, traveling. That's a pretty lofty model from which to distill expectations of myself. From such admiration, it can be hard to rewind my understanding to the writer she was at 33, my age, versus the writer she is now. For applications and in everyday conversation, I'm constantly in the mode of pitching the Next Big Thing on my creative to-do list. But I'm also at the stage of needing to learn that not every big project/goal can be willed to fruition, and that is not a sign of failure. Sometimes the victory is in letting it go.

Several friends have recently announced they are retiring manuscripts--taking them off the buyer's market or contest circuit, at least for now. They're grieving what feels like the loss of years, a failure. One of the brutalities of publishing is that a collection of worthy pieces does not make a worthy whole. Just because you've placed every poem with a literary journal does not mean the manuscript has the heft and clarity of vision that's going to win a book prize. Just because you've placed three of your chapters as personal essays does not mean your memoir proposal is going to sell. For publishers to make the forward investment of an advance, production, distribution and publicity, the work has to be not only solid, it has to glimmer. It's not enough that the editor likes the book; the editor has to fall asleep dreaming about the book. That seems like a hopelessly high expectation--"Just bottle the lightning, please"--but it's the way it is.

Sometimes the system, cruel as it may seem, saves us from our lesser selves. Patchett's a pro, a natural and prodigious talent. She could have written a good book about a year's service on the LAPD in the post-Rodney King era. But she couldn't have written a great book, not without finding a way to commit to the experience more fully, not unless she unpacked her father's service years beyond his permission. I've taken kill fees for pieces that at the time I felt really passionate about, and realized later that, dammit, the editor really was doing me a favor. I'm really glad I wrote the poem above, because there's some craft to it (elements I'd re-use and refine in later work), and it brings back a particular place of my life. But I'm really glad it wasn't part of what I sent out in Theories of Falling, because it would not have impressed Marie Howe one bit.

I'm fortunate to be part of a writing community filled with generative, supportive energy. Because we want to nourish each other's lives, we champion the books that reflect the labor of those lives. We cheer each other on by the dozens of Facebook "likes." It'd be odd to "like" someone's announcement that they're NOT writing a book (and in my mind, you're in the process of "writing" a book up until the very day you're holding it, bound, in your hands). Yet it's the very small population of readers--I can count them on one hand--who will say to me "this isn't working," or "are you sure this is the project for you, at this point in time?"--who are most precious. They are the ones who ground me in the mindset it will take to recognize, endure, and forgive myself for the inevitable misfires that are embedded in any writer's career.

When the University of Tampa MFA faculty spoke to students about practical matters, one of the pieces of advice I gave was to not get attached to publishing your thesis. It's not your first book. Seriously. It's Not a Book. Look at it as a pile of pages, from which you articulate, "Okay. What's the book hiding in here, the one that I didn't write?"

And why not? Did the structure you really wanted to try out seem too crazy--or too hard? Were you a tourist to the topic, and now you need six months of immersive research before it's steeped in the proper detail? Did you do too much research, and now you must stop "showing your work"? Is the story's deepest, darkest, least comfortable emotional revelation still unspoken? Is that what held a good book back from the world? If so, awesome. Keep going & have at it. But sometimes, the book you don't write doesn't get written because, frankly…you're a little bored with it. And it's not even written yet! If the book is not one the world really wants to read, really needs to read--if it's not a book your someday editor will fall asleep dreaming about--let it go. The pleasure and peril of being a writer is that there is always something else waiting to be written.

Published on January 25, 2014 11:26

January 20, 2014

In the New Year

I closed out 2013 by tromping the dunes of White Sands, New Mexico. I kicked off 2014 with the University of Tampa's low-res MFA program. The truth is, I only got a day's glimpse of the warmth that sends snow-birds to Florida in January. What motivates me are the students--they are adults, choosing a destination for their time and money--and I approach this relationship not as teaching, but as mentoring. That means no handholding, no interest in grading assignments for bureacuracy's sake. I think we're going to have a good time, even though my workload is merciless. Five students in three different genres, each with an individualized reading list; that's 50 books for me to read or re-read. Argh. But the fellow faculty is amazing, with standout lectures by Alan Michael Parker ("A Book is a Thing") and Stefan Kiesbye ("Dirty Wedding: The Marriage Between Lies and the Truth in Prose"). And the dance party, DJ'ed by poet Erica "Awesome" Dawson, would keep me returning in & of itself.

These next few weeks will be no less hectic. I'm closing on a nonfiction article. I'm heading to Georgia for the first of two stints with the Georgia Poetry Circuit. I'm trying on wedding dresses; trying to figure out how to store an office's worth of books in a closet. I'm leaning hard on figuring out a balance of work and life for the coming year.

This post on "Girl w/ Pen"drew my attention to Lost in Living, a documentary that follows four women over the course of seven years. The filmmaker, Mary Trunk, set out with the goal of capturing the struggles and rewards of working as an artist while becoming a mother. But what interests me is the finer details of how women relate to each other. It's very, very difficult--I'd venture to say impossible, unless one chooses cultural self-segregation--for a woman to have her decision to have or to not have children be anything other than a defining identity element in her 30s and 40s, an element that fundamentally frames how she relates to other women. The public conversation tends to be dominated by those who joyfully do or joyfully don't have kids. What about those in between? Those mothers who regret their kids? Or those who opt to be child-free, accepting that also comes with regret? That's a conversation I'd like to listen in on, which I suspect women writers and artists are especially capable of having. Might be too much to ask of this movie, but I'd like to see it happen.

If you teach creative nonfiction or journalism in the college classroom, I recommend you share this sequence of pieces with your students:

"Dr. V's Magical Putter," by Caleb Hannan"What Grantland Got Wrong," by Christina Kahrl"The Dr. V Story: A Letter from the Editor," by Bill Simmons

I have sympathy for Hannan--hard to know what to do when a seemingly innocuous profile leads you down the rabbit hole. But despite the piece's stylistic strengths, there are valid ethical issues on the table in terms of how the story was presented. Taken with Kahrl's critique, and Simmons's ultimate apology, it all adds up to a meaningful discussion of the pressures and responsibilities of the contemporary freelancer.

Before I forget: New year, new opportunities. If you're eligible, apply to this…

The Cave Canem Residency at The Rose O’Neill Literary House includes a public reading as part of the annual Summer Poetry Salon Series. The Fellow is awarded the use of a private, single-family residence for the month of June, along with a $1000 honorarium. The Fellow has the option of a manuscript consultation with the Director of the Literary House, poet Jehanne Dubrow. Applicants should send a statement of purpose, a CV, and a 10-page poetry sample to:

The Rose O’Neill Literary HouseWashington College300 Washington AvenueChestertown, MD 21620

For the 2014 Cave Canem Residency at The Rose O’Neill Literary House, applications will be accepted if postmarked by March 15, 2014.

I read with Kevin Vaughn for the 2012 salon--he was wonderful company, a rising talent, and I really enjoyed visiting Chestertown. Apply, apply.

Published on January 20, 2014 18:51

December 22, 2013

To the Poets I Know

This year's display at the Botanic Garden was inspired by the World Fairs of years past. As usual, surreal & lovely; the one Christmas tradition I always make time for in DC.

I sent a few notes to poet-friends today--to stay on top of my inbox --and realized, for all the casualness of tone, how important certain writers are in my life. You may be one of the people I'm thinking about, even though we're not that close.

Maybe because I've known you for over a decade, before either of us published.

Maybe because you talk about iambics and power tools with equal enthusiasm.

Maybe because you answered your phone that time I thought you were still at AWP and let me babble about snarky conference weirdness before gently mentioning you'd already flown home, were in a different time zone, and needed to get some sleep.

Maybe because you advocate for social change, and you aren't afraid to argue, whereas I am non-confrontational to a fault.

Maybe because you're so confident in your skin that you make me confident in mine.

Maybe because we always knock it out on the dance floor.

Maybe because you chose to go back to your hometown.

Maybe because you were really happy for me when I told you I'd won that prize, though I realized later I was accidentally breaking the news you hadn't won that prize.

Maybe because we share the realities of writing about the medicalized body.

Maybe because you're the most dedicated teacher I know.

Maybe because you were graceful that time I blanked on your name.

Maybe because you are a real pain in the ass, but you make things happen.

Maybe because you insisted on buying my book, though you already had a copy, so I could say I sold a book at the reading. And then you let me crash on your couch.

Maybe because even your promotional announcements are funny.

Maybe because you don't drink.

Maybe because you gave me the model, when I so desperately needed one, for valuing attention to my writing over starting a family.

Maybe because you stole Flat Langston.

Maybe because it could have been weird between us that one time and it wasn't.

Maybe because you show up at events all over the DC, Virginia and Maryland area even though I know you don't drive, which must means hours on buses and the metro.

Maybe because your poems are so dissonant and brave and musical they make me want to write harder.

You don't have to be on Facebook. We don't need to meet up for drinks. I don't have to be a "writer to watch" you list when asked to name them in interviews.

O o o poets. I just like to know you're out there, doing what you do. Thanks for that.

And Shann Palmer, you will be missed. Her blog, "Shann Palmer Says," has a December 11 poem draft. The next day Shann had a heart attack, and never woke from the coma that followed. I remember giving a reading in Richmond, Virginia, at Fountain Books for Theories of Falling--except the printer hadn't delivered my first copies in time. So I was selling little handmade chapbooks of the collection's highlights, bound with curling ribbon, with a black & white print-out of the cover-to-be. Shann bought one. She was a funny, practical, salty lady--I think if I called her a dame she'd take it as the intended compliment--yet a woman of faith, as well, and song, and a talented poet.

And Shann Palmer, you will be missed. Her blog, "Shann Palmer Says," has a December 11 poem draft. The next day Shann had a heart attack, and never woke from the coma that followed. I remember giving a reading in Richmond, Virginia, at Fountain Books for Theories of Falling--except the printer hadn't delivered my first copies in time. So I was selling little handmade chapbooks of the collection's highlights, bound with curling ribbon, with a black & white print-out of the cover-to-be. Shann bought one. She was a funny, practical, salty lady--I think if I called her a dame she'd take it as the intended compliment--yet a woman of faith, as well, and song, and a talented poet. I am so very ready for 2014.

Published on December 22, 2013 12:42

December 16, 2013

Meet Me in St. Louis (or at Politics & Prose)

I always have so much I want to tell you.

"In the years leading up to his recent passing, Alabama poet Jake Adam York set out on a journey to elegize the 126 martyrs of the civil rights movement, murdered in the years between 1954 and 1968."

"In the years leading up to his recent passing, Alabama poet Jake Adam York set out on a journey to elegize the 126 martyrs of the civil rights movement, murdered in the years between 1954 and 1968."

A year ago this past weekend, we lost the phenomenal poet and friend Jake Adam York. I'm so glad that we'll have one more chance to read new work from him--ABIDE will be out in March 2014, thanks to SIU Press and tireless editor Jon Tribble. In the meantime, tide yourself over with this interview in MEAD, and this signature poem, "Grace."

We miss you, Jake.

*

Last week I went to St. Louis for a reading with the Observable Reading Series. The flight out included hours on the runway, as DCA struggled define our relationship to the sleet (status update: it's complicated), the pilot sometimes changing prediction mid-sentence. Finally we took off, and as the air conditioning units cranked up the smell of de-icing chemicals flooded the cabin. The flight attendants gave us bag after bag of trail mix (and in my case, an illicit Dewar's), as what was supposed to be an afternoon flight slid past the dinner hour. I'm not skittish about flying, but I was glad to land....

...and to be promptly greeted by Steve Schroeder's cat, Ozymandias (Ozzy for short). Being home-hosted by people with cats may be one of my favorite part of being on the road. Steve is a co-curator of the Observable Series and he has a great new poetry collection out, The Royal Nonesuch. The next morning, I wandered the Missouri Botanic Garden for a bit, had lunch with a fellow poet from UVA days, and checked in at The Cheshire Hotel, which is kind enough to comp rooms for the visiting writers.

Good lordy. Apparently, in its prior incarnation this hotel was used for some of the cheesier scenes of Up in the Air. Also the pub lounge, Fox & Hounds, has been a long-favored dive bar for locals. But now the whole complex (which includes three separate restaurants) is refurbished and, while retaining just the right degree of tweed and embroidery and "old world" kitsch, The Cheshire absolutely glows with welcome. I spent hours camped out in front of the lobby's wood-burning fireplace. I stayed in the Robert Herrick Room, gathering rosebuds. Next time maybe I can snag the Ian Fleming Suite, which has a door that opens straight out onto the pool deck. The Cheshire joins The Highland Inn in Atlanta, and The Algonquin in Manhattan, of places where I'd like to be the writer-in-residence for a month, taking in the strangeness of hotel life.

Good lordy. Apparently, in its prior incarnation this hotel was used for some of the cheesier scenes of Up in the Air. Also the pub lounge, Fox & Hounds, has been a long-favored dive bar for locals. But now the whole complex (which includes three separate restaurants) is refurbished and, while retaining just the right degree of tweed and embroidery and "old world" kitsch, The Cheshire absolutely glows with welcome. I spent hours camped out in front of the lobby's wood-burning fireplace. I stayed in the Robert Herrick Room, gathering rosebuds. Next time maybe I can snag the Ian Fleming Suite, which has a door that opens straight out onto the pool deck. The Cheshire joins The Highland Inn in Atlanta, and The Algonquin in Manhattan, of places where I'd like to be the writer-in-residence for a month, taking in the strangeness of hotel life.

My co-reader was Paul Legault, author of several books including The Emily Dickinson Reader, which I bought that night; seemed appropriate on the occasion of Dickinson's 183rd birthday (she was born December 10, 1830). Published by McSweeney's, The EDR is one of the most physically handsome books I've ever held, with a center-aligned presentation of Legault's "English-to-English translations" for each of ED's 1,789 poems, as catalogued in the R.W. Franklin edition. The style and font add heft to a series of stichics that might otherwise be monotonous to the eye, and a gold ribbon is at the ready for you to hold your place; the collection invites a browsing pace. Periodically, we're greeted by a re-interpretation of the one iconic Dickinson portrait. The book closes with two indexes--one thematic and one of Dickinson's original first lines, which might be the only way some readers will recognize their canonical favorites.

ED's poem, "Hope is the thing with feathers-- / That perches in the soul--"

becomes:

Hope is kind of like birds. In that I don't have any.

...and so on. Don't read it in anticipation of any one "translation," because you'll probably find that singular instance a little easy or glib; that the index does not alphabetize Dickinson's first lines might be an implicit, wise discouragement of such behavior. Do read The EDR for the conversation across the whole, the wax and wane of surrealism punctuated with sentiment. Legault has a dry humor--this showed in his reading at Llywelyn's Pub, full of small asides and swallowed punchlines--that becomes a wet humor whenever any of the following topics arise: zombies, sex, sex with zombies, and Susan Huntington Gilbert Dickinson, Dickinson's sister-in-law, e.g. "Everything's better when you're naked. Take Sue, for example." (1361)

...and so on. Don't read it in anticipation of any one "translation," because you'll probably find that singular instance a little easy or glib; that the index does not alphabetize Dickinson's first lines might be an implicit, wise discouragement of such behavior. Do read The EDR for the conversation across the whole, the wax and wane of surrealism punctuated with sentiment. Legault has a dry humor--this showed in his reading at Llywelyn's Pub, full of small asides and swallowed punchlines--that becomes a wet humor whenever any of the following topics arise: zombies, sex, sex with zombies, and Susan Huntington Gilbert Dickinson, Dickinson's sister-in-law, e.g. "Everything's better when you're naked. Take Sue, for example." (1361)

At first, I had mixed feelings about the use of "Sue," who is the object of this Emily's fiercest desires; it's a bit strategic, a way to give Legault's book narrative cohesion and dramatic arc as it hopscotches across a lifetime of poems. Occasionally, Sue feels like a fallback for dealing with ED's less inspiring poems. Somehow the rather unmemorable "Behold this little Bane-- / The Boon of all alive--" translates to "Love is a bitch named Susan Gilbert Dickinson." (1464) Bury the lede, why dontcha. Some folks may un-questioningly absorb their affair as portrayed here as a bit of newfound trivia concerning the "real" ED's biography. Ack.

But is that so different from framing her life in terms of Thomas Wentworth Higginson, or the Master, or any of the other ways scholars struggle to capture such a willfully elusive, reclusive spirit? Is it any more presumptive than pasting Dickinson's verse into a greeting card? No, I'd argue--and in fact this treatment, though perverse, carries more reverence. Legault engages us in talking about a poet he loves, and he has a wonderful sensibility for phrasing truth claims in a skeptic's landscape. The reader in me smiles at such non sequiturs such as "Light is a communist." (506). Later, "I'm a bad driver because I enjoy leaving things to chance." (1283).

The premise for The Emily Dickinson Reader is deeply clever, and I enjoyed it so much I read the whole damn thing in two sittings. Honestly, I'm a little jealous of Paul Legault for writing it--that best, strangest kind of author-to-author compliment.

*

Have you gotten your hands on The Incredible Sestina Anthology yet?

Two magazines with my favorite trim size-- 32 Poems and Cave Wall --both have new issues hot off the presses.

I'll lead a discussion at Politics & Prose, "Inside The Best American Poetry 2013," from 1-3 PM on Thursday, January 16. Advance registration is required; could be a fun holiday gift to a poet in the family, paired with a copy of BAP 2013 and/or Denise Duhamel's Blowout, both of which we'll reference. Much of the session will be spent on real-time, close reading of some of the year's best poems (according to BAP) in terms of craft and theme. We'll also have a fun, frank discussion of how "best of" collections come to exist, how they're curated, and what a guest editor's aesthetic adds to the mix.

"In the years leading up to his recent passing, Alabama poet Jake Adam York set out on a journey to elegize the 126 martyrs of the civil rights movement, murdered in the years between 1954 and 1968."

"In the years leading up to his recent passing, Alabama poet Jake Adam York set out on a journey to elegize the 126 martyrs of the civil rights movement, murdered in the years between 1954 and 1968."A year ago this past weekend, we lost the phenomenal poet and friend Jake Adam York. I'm so glad that we'll have one more chance to read new work from him--ABIDE will be out in March 2014, thanks to SIU Press and tireless editor Jon Tribble. In the meantime, tide yourself over with this interview in MEAD, and this signature poem, "Grace."

We miss you, Jake.

*

Last week I went to St. Louis for a reading with the Observable Reading Series. The flight out included hours on the runway, as DCA struggled define our relationship to the sleet (status update: it's complicated), the pilot sometimes changing prediction mid-sentence. Finally we took off, and as the air conditioning units cranked up the smell of de-icing chemicals flooded the cabin. The flight attendants gave us bag after bag of trail mix (and in my case, an illicit Dewar's), as what was supposed to be an afternoon flight slid past the dinner hour. I'm not skittish about flying, but I was glad to land....

...and to be promptly greeted by Steve Schroeder's cat, Ozymandias (Ozzy for short). Being home-hosted by people with cats may be one of my favorite part of being on the road. Steve is a co-curator of the Observable Series and he has a great new poetry collection out, The Royal Nonesuch. The next morning, I wandered the Missouri Botanic Garden for a bit, had lunch with a fellow poet from UVA days, and checked in at The Cheshire Hotel, which is kind enough to comp rooms for the visiting writers.

Good lordy. Apparently, in its prior incarnation this hotel was used for some of the cheesier scenes of Up in the Air. Also the pub lounge, Fox & Hounds, has been a long-favored dive bar for locals. But now the whole complex (which includes three separate restaurants) is refurbished and, while retaining just the right degree of tweed and embroidery and "old world" kitsch, The Cheshire absolutely glows with welcome. I spent hours camped out in front of the lobby's wood-burning fireplace. I stayed in the Robert Herrick Room, gathering rosebuds. Next time maybe I can snag the Ian Fleming Suite, which has a door that opens straight out onto the pool deck. The Cheshire joins The Highland Inn in Atlanta, and The Algonquin in Manhattan, of places where I'd like to be the writer-in-residence for a month, taking in the strangeness of hotel life.

Good lordy. Apparently, in its prior incarnation this hotel was used for some of the cheesier scenes of Up in the Air. Also the pub lounge, Fox & Hounds, has been a long-favored dive bar for locals. But now the whole complex (which includes three separate restaurants) is refurbished and, while retaining just the right degree of tweed and embroidery and "old world" kitsch, The Cheshire absolutely glows with welcome. I spent hours camped out in front of the lobby's wood-burning fireplace. I stayed in the Robert Herrick Room, gathering rosebuds. Next time maybe I can snag the Ian Fleming Suite, which has a door that opens straight out onto the pool deck. The Cheshire joins The Highland Inn in Atlanta, and The Algonquin in Manhattan, of places where I'd like to be the writer-in-residence for a month, taking in the strangeness of hotel life.

My co-reader was Paul Legault, author of several books including The Emily Dickinson Reader, which I bought that night; seemed appropriate on the occasion of Dickinson's 183rd birthday (she was born December 10, 1830). Published by McSweeney's, The EDR is one of the most physically handsome books I've ever held, with a center-aligned presentation of Legault's "English-to-English translations" for each of ED's 1,789 poems, as catalogued in the R.W. Franklin edition. The style and font add heft to a series of stichics that might otherwise be monotonous to the eye, and a gold ribbon is at the ready for you to hold your place; the collection invites a browsing pace. Periodically, we're greeted by a re-interpretation of the one iconic Dickinson portrait. The book closes with two indexes--one thematic and one of Dickinson's original first lines, which might be the only way some readers will recognize their canonical favorites.

ED's poem, "Hope is the thing with feathers-- / That perches in the soul--"

becomes:

Hope is kind of like birds. In that I don't have any.

...and so on. Don't read it in anticipation of any one "translation," because you'll probably find that singular instance a little easy or glib; that the index does not alphabetize Dickinson's first lines might be an implicit, wise discouragement of such behavior. Do read The EDR for the conversation across the whole, the wax and wane of surrealism punctuated with sentiment. Legault has a dry humor--this showed in his reading at Llywelyn's Pub, full of small asides and swallowed punchlines--that becomes a wet humor whenever any of the following topics arise: zombies, sex, sex with zombies, and Susan Huntington Gilbert Dickinson, Dickinson's sister-in-law, e.g. "Everything's better when you're naked. Take Sue, for example." (1361)

...and so on. Don't read it in anticipation of any one "translation," because you'll probably find that singular instance a little easy or glib; that the index does not alphabetize Dickinson's first lines might be an implicit, wise discouragement of such behavior. Do read The EDR for the conversation across the whole, the wax and wane of surrealism punctuated with sentiment. Legault has a dry humor--this showed in his reading at Llywelyn's Pub, full of small asides and swallowed punchlines--that becomes a wet humor whenever any of the following topics arise: zombies, sex, sex with zombies, and Susan Huntington Gilbert Dickinson, Dickinson's sister-in-law, e.g. "Everything's better when you're naked. Take Sue, for example." (1361)At first, I had mixed feelings about the use of "Sue," who is the object of this Emily's fiercest desires; it's a bit strategic, a way to give Legault's book narrative cohesion and dramatic arc as it hopscotches across a lifetime of poems. Occasionally, Sue feels like a fallback for dealing with ED's less inspiring poems. Somehow the rather unmemorable "Behold this little Bane-- / The Boon of all alive--" translates to "Love is a bitch named Susan Gilbert Dickinson." (1464) Bury the lede, why dontcha. Some folks may un-questioningly absorb their affair as portrayed here as a bit of newfound trivia concerning the "real" ED's biography. Ack.

But is that so different from framing her life in terms of Thomas Wentworth Higginson, or the Master, or any of the other ways scholars struggle to capture such a willfully elusive, reclusive spirit? Is it any more presumptive than pasting Dickinson's verse into a greeting card? No, I'd argue--and in fact this treatment, though perverse, carries more reverence. Legault engages us in talking about a poet he loves, and he has a wonderful sensibility for phrasing truth claims in a skeptic's landscape. The reader in me smiles at such non sequiturs such as "Light is a communist." (506). Later, "I'm a bad driver because I enjoy leaving things to chance." (1283).

The premise for The Emily Dickinson Reader is deeply clever, and I enjoyed it so much I read the whole damn thing in two sittings. Honestly, I'm a little jealous of Paul Legault for writing it--that best, strangest kind of author-to-author compliment.

*

Have you gotten your hands on The Incredible Sestina Anthology yet?

Two magazines with my favorite trim size-- 32 Poems and Cave Wall --both have new issues hot off the presses.

I'll lead a discussion at Politics & Prose, "Inside The Best American Poetry 2013," from 1-3 PM on Thursday, January 16. Advance registration is required; could be a fun holiday gift to a poet in the family, paired with a copy of BAP 2013 and/or Denise Duhamel's Blowout, both of which we'll reference. Much of the session will be spent on real-time, close reading of some of the year's best poems (according to BAP) in terms of craft and theme. We'll also have a fun, frank discussion of how "best of" collections come to exist, how they're curated, and what a guest editor's aesthetic adds to the mix.

Published on December 16, 2013 09:15

November 19, 2013

Heart Land

I've enjoyed hunkering down in Iowa for these weeks. Teaching at Cornell College has been a revelation--the focus on creative nonfiction, with an emphasis on incorporating science on technology, has been a great change of pace. Some thoughts....

1) Meeting with students five days a week permits no room for procrastination. Each week takes on its own thematic shape and pace. The 10-11 AM "workshop hour," in which I divided my 15 students into groups of 3 and 4 for the sake of informal conversation, was both my single best decision (in terms of getting to know my students) and the worst decision (in terms of conserving my own work time).

2) I am still not a morning person.

3) This generation of students doesn't use email much. They don't send a confirming reply unless you explicitly request it, so it can feel like you're shouting into the void. On the upside, I was glad they so readily left behind their laptops in coming to class.

4) Lecturing on five books, a dozen articles, and the craft of nonfiction is a lot for one month. I used cards with abstract keyword prompts (e.g., for The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks: gender, class, race, identity) to guide discussion. Being a teacher requires an extraordinary vocabulary, one which you can and will flub from time to time, and then you must decide: do I correct myself in front of my students?

5) I still haven't figured out how to balance the needs of the students who get lost in class-wide silences, and the ones who use those silences to shape their answers.

6) No matter how sophisticated your class, arts and crafts are a good thing. Every time I can work erasures onto a syllabus, I do, thanks in large part to Mary Ruefle's great craft essay. This time around, we're using outdated science textbooks courtesy of Cornell College's library to shape creative texts from "uncreative" sources.

7) Never give back graded work at the beginning of class; always wait until the end.

8) Students are comfortable reading beyond their level in an academic field, as long as they are regularly assured that it's okay to not "get" everything. I was delighted by how many gravitated to Leonard Susskind's The Black Hole War, opting to read it in its entirety, which I suspect is in part because he is so generous on this point.

9) Strange that we ask students to spend four years offering up informal opinions--"Did you like it?"--and close analysis on the page, without offering practical experience with the intersection of the two: the 1,200-word book review. That's a real-world writing skill. We talked about what reviews are meant to do, reading examples from the New York Times Book Review and The American Scholar, and they wrote their own.

10) You never know which readings students will love, and which will elicit a "Meh." You never know which personal details to share, or which questions to answer only with editing. You never know who dreams, deep down, of being a poet.

Back in my own undergraduate days at the University of Virginia, I realize that I had no idea how hard it was to run a class. In recalling the things we harped on--spotting typos, expecting a 100% correct answer to every question, sulking when someone returned graded papers later than expected--I'm embarrassed. And newly grateful.

Most nights I come home to Collin House and daze out with an infinite supply of SVU episodes. But I made it to Iowa City to see Hailey read from her new book, SWOOP, at Prairie Lights, and afterwards we sat by the fireplace at Sanctuary. In Cedar Rapids, I walked the Czech Village, then camped out at the NewBo Market to watch a juggler and snack on fresh falafel. On a tip from the gentleman who specialized in Eggenberg glass, I drove to Solon and found an oasis of entrepreneurship. The Salt Fork Kitchen is on one side of the street, with a bloody mary bar stocked with house-picked onions and four different pepper sauces. On the other side of the street, Big Grove Brewery sells six varieties of in-house beer--I recommend their seasonal IPA, the Redheaded Stranger--and serves dishes like this elaborate roasted cauliflower, with curry sauce and coppa ham. (That morning, the chef had also carved a duck from a whole pear, which then roamed the length of the bar. Not for sale.) These two places, staffed by enthusiastic 20- and 3o-somethings, have only been open a matter of months. I hope they thrive.