Sandra Beasley's Blog, page 2

September 24, 2020

Transcript of The Slowdown (9/24/20)

I woke up to a flurry of notes from folks excited that my poem, "The Piano Speaks" (part of my second collection, I Was the Jukebox) is featured as part of Tracy K. Smith's podcast "The Slowdown." I'm excited too!

I woke up to a flurry of notes from folks excited that my poem, "The Piano Speaks" (part of my second collection, I Was the Jukebox) is featured as part of Tracy K. Smith's podcast "The Slowdown." I'm excited too! But I believe in fighting for optimal access, which means podcasts should come with transcripts. Since they didn't release one, I made one to post here.

Please ask podcast producers to create and release transcripts of their shows. The more pressure we create as a community, the more likely our requests will be honored. Eventually this can (and should) become a baseline standard of access. Access is love.

#479: Transcript of The Slowdown Podcast with Tracy K. Smith

September 24, 2020 [Click here to visit the site's page with audio]

[[Opening announcement for Better Help online professional counseling services. Listeners get 10% off the first month of services with the discount code “Slowdown.” Go to www.BetterHelp.com/slowdown to learn more and make an appointment.]]

[Background music, instrumental.]

I’m Tracy K. Smith and this is The Slowdown.

[Music break.]

You know how they say that, when confronted with a photo, most peoples’ natural inclination is to seek out themselves? I suspect this might also be the case on videoconferencing platforms. I have Zoom meetings most every day, and I hate to admit it, but of all the faces in the tiny grid, my eyes keep gravitating back to my own. Is that what I look like when I talk? I find myself thinking. How is that the expression I make when I listen? What’s up with my mouth? And on, and on. I think I may have found the true culprit of the “Zoom headache.”

My kids are the same way. For them, Face Time is just a chance to make loony faces in what is, essentially, a flashy mirror. With a tap of button I hadn’t previously known existed, they can turn themselves into foxes, or sharks, or—much to my dismay—poo emojis. Which is why it’s so exciting when I find them enthralled by a mound of dirt in the backyard, or bent over the pages of an actual book. They’ve wriggled free of the human compulsion for self-scrutiny. For however long it lasts, they’ve forgotten themselves entirely.

The same goes for me when I sink into a good book, or sit in the backyard chasing after a woodland creature with just my eyes. That rapturous self-forgetting helps me temporarily cut ties who I am, and what I lack, and how soon I ought to get back to the task of trying to keep up with my betters. It’s been hard to get to that state under the current conditions. Everywhere I look, there’s evidence of me. Best are the days when something unexpected takes me by surprise. A song comes on, even a song I’ve heard a thousand times before, but this time it opens up a new door. Or, I turn the page onto a rapturous metaphor and finally, thankfully, I’m carried far far away from the cage of my own self-regard.

I guess this is another of the lifesaving properties of art: the ability to carry us far beyond the limits of our known selves. Because the world is full of fascinating perspectives, and sometimes one very good form of self-care is to get lost in the world outside your head.

Today’s poem is “The Piano Speaks,” by Sandra Beasley.

The Piano Speaks

After Erik Satie

For an hour I forgot my fat self,

my neurotic innards, my addiction to alignment.

For an hour I forgot my fear of rain.

For an hour I was a salamander

shimmying through the kelp in search of shore,

and under his fingers the notes slid loose

from my belly in a long jellyrope of eggs

that took root in the mud. And what

would hatch, I did not know—

a lie. A waltz. An apostle of glass.

For an hour I stood on two legs

and ran. For an hour I panted and galloped.

For an hour I was a maple tree,

and under the summer of his fingers

the notes seeded and winged away

in the clutch of small, elegant helicopters.

[Background music, instrumental.]

The Slowdown is a production of American Public Radio in partnership with the Poetry Foundation. This project is supported in part by the National Endowment for the Arts, on the web at arts.gov.

#

September 17, 2020

"The End of an MFA"

First off, full disclosure: I had to request that we call it "The End of an MFA." They'd titled it "The End of the MFA," which felt far too dire.

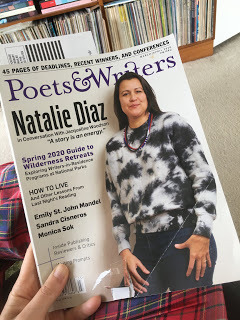

I have a new piece out in a nationally distributed magazine, and usually when that happens I shout from the rooftops. But I've been quiet this time--until a couple of friends, earlier this week, gently asked: why the silence? Part of the reason is that my essay, "The End of an MFA: What Happens When a Low-Residency Program Closes?" is not online; there's no link to share. Anyone interested will have to go pick up the September/October issue of Poets & Writers off the newsstands or, more likely, get around to finally reading the subscriber's copy that arrived a few weeks ago.

I'm proud of the piece. I welcomed the depth of understanding that came with the multiple interviews I did to research it--I found that people were excited to talk with someone paying attention to the fact that * seven * low-res MFA programs have closed down since 2015. What's hit me in recent weeks is how acutely I am also grieving the loss of my own program at the University of Tampa. From the (very recently) updated website: "The MFA in Creative Writing is being discontinued and will no longer accept applicants."

The view in the snapshot above is one I've gotten every January and June since 2014, with the minarets of Plant Hall visible on the other side of the river. I'll always be grateful for the traipsing to Ybor City in the early days; the brisk walks along the river in recent ones, where I would stop in at the Armature Works for a bowl of ramen or a slab of ribs; the discovery of the gem that is the Tampa Museum of Art; conversations at The Retreat that left the stink of smoke in my hair; a pint sipped under the thatched-roof of Four Green Fields while I worked on an intro for the Lectores series. For the first time I had my own distinct home city in Florida, a state that my family (and my in-laws) have had ties to for as long as I can remember.

Tampa is where I learned to teach. I got the invitation to apply when the main adjunct experience I had under my belt was a "Writing I" class at the Corcoran College of Art + Design (also now closed, ooof). I'm not saying I was unqualified--I'd led workshops in community writing spaces such as The Writer's Center (where I still teach), and I'd had multiple visiting writer gigs in tandem with book tours, which had taken me into classrooms across the U.S. But this was different. Steve took a chance on me. This was a paradigm shift, something that began to sink in as I met the other teachers and thought... colleagues? After years of lone-wolfing, I'd found a pack.

My devotion might have been particularly acute because I had nowhere else where I taught on a regular basis. Sitting in on every seminar that I could--usually from my vantage point of sitting in the corner, on the floor, near the stage of Reeves Theater--I got a priceless education of my own. I hope that the colleagues I annoyed over the years by "eavesdropping" on their lessons can forgive me, but honestly I was just so excited to learn from you all. I also reaped the benefit of the fancy writers who we brought through as visiting Lectores. To be honest, I learned both from them and about them. I learned that what matters isn't the excitement the students have when you arrive, because that can be all glamour and no substance; what matters is the forward momentum the students have after you leave.

Tampa was where I developed my workshop style: bright, performative, probably reading- and vocabulary-heavy, hopefully with a lot of laughter to ease the rigor. Tampa is where I developed my first dozen go-to hourlong lectures, which I'll carry with me for the rest of my teaching career, and realized that I delight as much in teaching nonfiction as I do in teaching poetry. Tampa is where I discovered what I'm most gifted at (line edits) and what I spend way too much time on (line edits). Tampa is where I had the time to form lasting mentorships with students, often seeded by the solidarity of shared identities or reference points.

Tampa is where, ironically, I learned these mentorships were not limited by geography. I'm a firm believer in the low-residency model for the access and flexibility it offers. I took student work with me to Cyprus, to Kansas, to Ireland. I conferenced with a student on my wedding day, while someone fussed with the back-closure of my dress. I conferenced with a student while I was hunkered down on the floor of my SW DC apartment with my dying cat (that wasn't ideal, but bless the student for making me laugh in such a tough time).

Students, you have been so, so kind and patient with me, and you trusted me with such valuable material of life and art. I'll never forget that.

On the scale of 2020 losses, this is bearable. I've already heard from teachers delighted by the UT transfer students landing in their respective low-res MFA programs. I have every faith that they'll thrive. I'm fortunate to have a final two talented students, both of whom I taught in earlier semesters, with whom I'll get the satisfaction of shaping thesis manuscript--one last poetry collection, one last nonfiction work.

That said, I wish we'd gotten a proper send-off. When we met in January of this year, though there was open concern, there was also a resolve to rally and recruit. By February, the program had been shut down via an e-mail. In March, all of our AWP gatherings were cancelled. The June residency moved to Zoom because of COVID-19. I suspect the January 2021 capstone events for our last round of graduates will also be online or, even if there is an in-person component, it will feel risky for our scattered (former) faculty to fly in for the festivities. We deserved one more dance party.

There's no need to use this space for a post-mortem, or to philosophize about why our low-residency program was vulnerable in the first place. Read the article! I just thought I'd put here what I couldn't put there, which was: pure gratitude. And pure sadness.

August 4, 2020

Necessity Is the Mother of New Poems

I get leads on projects many different ways, but this is the first time that a neighbor--one with whom I trade cat-sitting favors--has given me a heads-up on a call for poets. Fast-forward to being on the phone with the organizer of an annual local outreach project that usually takes the form of four communal meals staged during the month of August. The Sunday Supper series would have to take a different form this year, due to COVID-19 concerns.

The question: could I write six poems with one week's notice?

The answer would usually be No. I'm not a particularly fast or prolific poet. If asked to talk about how I come up with a poem, I compare the process to an oyster at work.

But I really wanted to take part in this project, to be staged in the Southwest Duck Pond adjacent to our apartment in DC. That's the park I look out over, from our balcony; the park whose quacking ducks keep company on quiet summer days; the park we walk through on our loop to the farmer's market. For me, the Southwest Duck Pond is the heart of the neighborhood, and I couldn't imagine passing on the chance to have poems there.

As I talked to the organizer, I was pacing our living room. My gaze fell on a copy of Yoko Ono's Grapefruit. That was the solution, I realized: action poems.

As I talked to the organizer, I was pacing our living room. My gaze fell on a copy of Yoko Ono's Grapefruit. That was the solution, I realized: action poems.I don't know if there's any singular or formal definition of an "action poem" but they are usually simple in their premise, a text that stages a series of steps or philosophical considerations (they have a counterpart in Ono's "pieces," such as Cut Piece, where the emphasis is on the actual engagement versus the prescriptive text).

As a student at the University of Virginia, I fell in love with Ono's work through a literature class that had us considering it alongside Ishmael Reed, Djuna Barnes, Tillie Olsen, and other counter-culture icons. If I visit a museum with a significant Fluxus holding, I go in search of her work. The big and heavy, blue-foil-covered 2000 edition of YES was my first experience with getting a "fancy" art book; I'd bought Grapefruit from Brooklyn's now-defunct BookCourt as a travel edition, something I could share with students.

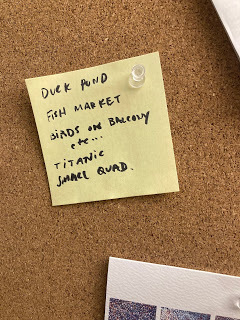

The project organizer signed off on the umbrella concept. Now I wouldn't have to come up with six separate premises--but I still needed six distinct ideas. My husband and I sat out on the balcony over the weekend, brainstorming what we thought of when we thought of the SW quadrant, and why we'd moved here five years ago. The next morning, he presented me with a Post-It on which he'd jotted notes.

The night before deadline, I was up for hours but it was a happy energy. Most poets will admit a crisis of confidence after we finish a book. Is that it? Is that the last poem I'll ever write? I knew that these texts were engaging themes in Made to Explode--which has a whole section of prose poems dedicated to DC--but they felt distinct, new, in part because a public art installation requires a different energy. And oh, it felt good simply to be word-smithing and line-breaking again.

The night before deadline, I was up for hours but it was a happy energy. Most poets will admit a crisis of confidence after we finish a book. Is that it? Is that the last poem I'll ever write? I knew that these texts were engaging themes in Made to Explode--which has a whole section of prose poems dedicated to DC--but they felt distinct, new, in part because a public art installation requires a different energy. And oh, it felt good simply to be word-smithing and line-breaking again. The installation went up yesterday. In lieu of the actual long table with 25 chairs of years past, a chalkboard-covered mock table invites comments from passersby, while two oversized chairs model a social distance. On fifteen of the bright red rocking chairs that are a signature, a mesh pouch holds a laminated, ring-bound booklet featuring the work of seven local poets, alongside conversation prompts and suggestions for additional reading; an online component shares all the poems, plus streamable playlists from DC DJs.

As I write this, a tropical storm is passing through the city. So I have to hope that those laminated pages are water-tight, and that the letters in "community" are fastened to stand against high winds. I have to keep faith that the sun will come back, and people will gather to the duck pond to sit in the rocking chairs and read poems. Nothing's easy in 2020. But I'm still here, and you're still here, and that's a start to something.

May 2, 2020

What Breaks Through: Poetry Book Contests

Those who have worked with me through the University of Tampa's MFA program, or in individual consultation , know that organizing manuscripts is my favorite thing to do. There's something magical about observing what chemistry is generated from individual poems, written over a span of months or perhaps years, being put into conversation with each other. I try to be generous but persistent in asking what it will take to create a successful manuscript, versus the optimizing of individual drafts. I love shuffling and re-shuffling pages to create the right pattern, and approaching ordering as both art and science.

I've benefitted from winning multiple contest-driven models toward publication, and been a behind-scenes force in deciding the outcome of others. There's a lot of apprehension and suspicion around awards--how deliberation happens, who benefits, how you can bet prepare your manuscript. I don't claim to have definitive answers, but I can tell you about my own experience and instincts.

As a judge, here's what I look for:

Is the approach to speaker(s) discernible?

I never assume the speaker and the author are the same person. Period. Even if there seems to be a close congruence. The rigor of my position has proven useful in leading workshops, and it means that I'm not prejudiced against "unlikable" protagonists. That said, I know we often draw from the well of biography in writing poems, and I respect the intimacy of the "I" and "you," as well as any archetypal proper nouns such as "Mother" or "Dad," when on the level of the individual poem.

What gets tricky is when I'm reading a chapbook or section in which the manuscript only periodically relies on having a sustained speaker: meaning, the author wants the understanding to be cumulative, in fact relies on it...until they don't.

This often takes the form of a persona poem that would, if applied to poems surrounding, dramatically shift our understanding of the relationship to a "you" or a given love / family member. The manuscript actually wants us to engage with that poem in a vacuum--to lift it out of context, as a moment of experimentation--but if that's the case, I look for helping signifiers on the level of title or form. Otherwise, you're inexplicably breaking your contract with the reader.

And if a figure carries over from a poem to the one immediately following, check to see if there's continuity in tense and mode of reference (direct address, versus third-person narration). If there's a change in how the character is handled--why? Is it tied into a changing perspective or emotional distance? There's nothing wrong with revising poems to be in more substantive dialogue with one another, even if they'd already been in print on the level of journals or magazines.

Does this gathering of poems have urgency?

This often gets simplified to saying contests favor the "project" book. I don't think that's strictly true. But every artistic medium is struggling with the pleasures and perils of volume--the reality of many worthy voices that are publishing, performing, and producing new work in these times--and while that's terrific, we look for why this particular set of poems needs to appear together and now. This is particularly relevant in scenarios where you're taking your recommendation of a winner into conversation with a group, arguing for it against others' top picks.

Tension can come from concerns that are thematic or formal, but it's gotta be there. Personal identity, historical moment conversant zeitgeist, core relationship dynamics, craft of form or line--create a collection that articulates a crisis or big question of some kind. Here's the good news: sometimes a single poem is enough to raise a collection's long simmer to a boil. Maybe that's a poem waiting to be written.

What poems do I remember the next day?

Judging is usually done under less than ideal circumstances, along with everything else when you're trying to make a living as a writer. The boxes of binder-clipped pages that used to arrive at the homes of National Poetry Series screeners were legendary. Although we've since found a way to spare the trees using online submission, one's neurons can still get pretty frazzled.

Any responsible judge will only solidify a decision over multiple days, usually via an informal sifting out of manuscripts worthy of further consideration. Every manuscript on Day 1 might blur together. But the manuscript we pick up first on Day 2 or 3 might get our best, freshest attention. Motivate us to return to yours. If the decision comes down to a few manuscripts of indistinguishably high quality, we might ask, "What's the single poem that has made the strongest impression?"

So: don't hide your light under a bushel. Lead with a poem that will energize and inform every poem we read thereafter, and don't save the "best" for last. If you want more thoughtful dialogue about what poems to use when opening and closing, check out this series of interviews conducted by Sarah Blake for Chicago Review of Books.

*

Keep in mind that this is in addition to whatever evident qualities of image, soundplay, lineation, and narrative that I'll reward on the level of the individual poems.

There's no magic formula to calculating who will like your work: some judges favor contest entrants kindred to their own aesthetic, whereas others specifically resist anything that sounds too much like themselves.

What I'd advise is that if there's any particular "de-coding" that might be needed to best access the collection, such as identifying a nouveau form or citing historical resources and allusions, err on the side of being direct in your explanations via endnotes, epigraphs, etc.. You can always lighten the touch later, in consultation with your editors. But there's no way to clarify retroactively.

Here's what I don't worry about:

Who you are. Manuscripts are usually scrubbed of identifying info before they get to me but, when not, it's pretty easy to set aside awareness of the author. (Unless I've mentored or have an intimate relationship with them--at which point, I'd disclose the conflict.) The extent to which author identity matters is if the manuscript centers on a particular culture, I want to have good faith that it's not an appropriative or merely decorative gesture. But it's on me to figure that out from the text itself.

That one typo. You know how you send off a manuscript and then find the page where gibberish (or worse, a wrong but plausible phrasing) has crept in? Or realize you should have switched the order of a couple poems? That happens to all of us. Don't feel like you need to bother a contest administrator--pleading to update a file or substitute a page--based on such gremlins. They aren't the make-or-break factor.

Here's what YOU need to consider:

If you view a chapbook or book as the destination, you'll almost invariably be let down on some matter of production value, interaction with the editors, or lack of media recognition. No process is perfect, especially if it's coming after years of anticipation.

I use the metaphor of book as passport; online or in person, where can a collection can take you? What conversations will it spark? That said, your publisher is not your travel agent. People are often surprised to realize that W. W. Norton doesn't arrange or fund my participation in readings, conferences, or festivals. I do it all on my own. And there's a lot to consider about the privileges and iniquities embedded in an attitude of "you make your own path"--that's not a tidy end to any conversation. But it's where we need to begin, in understanding the value of contests that yield an artifact of bound pages and a judge's citation. What I've experienced over and over is that what matters most is not a physical book, but the community it fuels.

*

If you're interested in learning more about

Driftwood Press's Chapbook Contest

, the guidelines are here--you have until July 1 to submit a manuscript of 15-40 pages. The cost is only $12, though I'd encourage you to take the $20 option that includes a copy of the winning chapbook. I bought a trio while visiting the Driftwood Press table at the (rumored, improvisational) AWP Conference in San Antonio, and they're beautifully designed. Each closes with a brief interview with the author, which makes the collection eminently teachable. Pictured here with editors Jerrod Schwarz (center) and James McNulty (right) is recent winner Kimberly Povloski, author of Hell of Birds.

If you're interested in learning more about

Driftwood Press's Chapbook Contest

, the guidelines are here--you have until July 1 to submit a manuscript of 15-40 pages. The cost is only $12, though I'd encourage you to take the $20 option that includes a copy of the winning chapbook. I bought a trio while visiting the Driftwood Press table at the (rumored, improvisational) AWP Conference in San Antonio, and they're beautifully designed. Each closes with a brief interview with the author, which makes the collection eminently teachable. Pictured here with editors Jerrod Schwarz (center) and James McNulty (right) is recent winner Kimberly Povloski, author of Hell of Birds. I'd love a chance to read the poems that you've been working on.

April 15, 2020

Unexpected Cameo

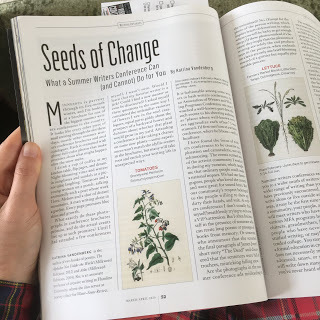

I got about half-way in and thought, Oh! Katrina Vandenberg! The essay is "Seeds of Change: What a Summer Writers Conference Can (and Cannot) Do For You." I was with Katrina at the Sewanee Writers' Conference. We haven't stayed in close contact. But I regularly use her craft essay, "Putting Your Poetry in Order: The Mix-Tape Strategy," in my classes.

Then I got to page 55 and thought, "Um...."

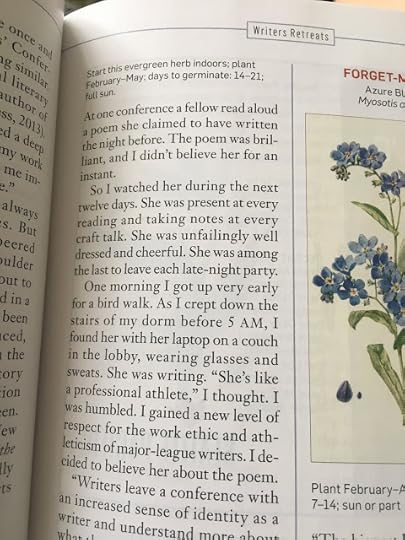

The text, in case you can't access the image:

"At one conference a fellow read aloud a poem she claimed to have written the night before. The poem was brilliant, and I didn't believe her for an instant.

So I watched her during the next twelve days. She was present at every reading and taking notes at every craft talk. She was unfailingly well dressed and cheerful. She was among the last to leave each late-night party.

One morning I got up very early for a bird walk. As I crept down the stairs of my arm before 5 AM, I found her with her laptop on a couch in the lobby, wearing glasses and sweats. She was writing. 'She's like a professional athlete,' I thought. I was humbled. I gained a new level of respect for the work ethic and athleticism of major-league writers. I decided to believe her about the poem."

Sandra Beasley at SWC, 2008 - Photo by Aaron BakerThis is such a generous portrait that I'm hesitant to claim it, especially since there's no way in which I'm like a professional athlete. That said...this is about me! And a quick email to Katrina confirmed my suspicion.

Sandra Beasley at SWC, 2008 - Photo by Aaron BakerThis is such a generous portrait that I'm hesitant to claim it, especially since there's no way in which I'm like a professional athlete. That said...this is about me! And a quick email to Katrina confirmed my suspicion. I would have been wearing pajamas, not sweats. I got in the habit of wearing pajamas when I lived on the Lawn at UVA (a year that required trekking outside to use a communal bathroom). I've always been a night owl, and I was on deadline to Black Warrior Review for a chapbook manuscript that was supposed close to being ready and which, secretly, I had not written yet. I don't know about being ever-cheerful. On one hand, I was thrilled by the recent publication of my debut; on the other hand I'd been told by the distinguished mentor assigned to me for the conference that my new work didn't interest her much, so much so that she had no feedback to offer. I didn't know what to make of that.

What saved me were the fellow fellows. I loved their camaraderie, their kindness, drinking and laughing into the late hours. I'd never been around so many writers in the prime of their creativity. And yes, sometimes on top of those late hours I would add later hours of drafting.

Some of the 2008 SWC Fellows.This was the summer that I fell in love with the sestina: it's gyroscopic energy, the requisite problem-solving. The poem that Katrina is referring to is "Let Me Count the Waves," which uses an epigraph from Donald Revell. I was intrigued by the possibility that if I used "face" as one of the endwords, and "butt" as another, the collision necessitated by the closing envoi would invite me to address someone as "buttface" (sorry, Mr. Revell, I was strictly motivated by technical opportunity). What really fueled the poem was thinking about the ways my age and femininity--my skirts, my shawls--were affecting the lens through which my work was being viewed, even while attempting a bravado of form. I printed out a draft on the cheap but sturdy Hewlett-Packard I'd lugged down in my trunk from DC, and slipped a folded copy to Claudia Emerson for her to read before anyone else. By the time we sat down to the dinner table that night, I'd ramped up my confidence (aided by a prod from Eric McHenry) to share the poem aloud.

Some of the 2008 SWC Fellows.This was the summer that I fell in love with the sestina: it's gyroscopic energy, the requisite problem-solving. The poem that Katrina is referring to is "Let Me Count the Waves," which uses an epigraph from Donald Revell. I was intrigued by the possibility that if I used "face" as one of the endwords, and "butt" as another, the collision necessitated by the closing envoi would invite me to address someone as "buttface" (sorry, Mr. Revell, I was strictly motivated by technical opportunity). What really fueled the poem was thinking about the ways my age and femininity--my skirts, my shawls--were affecting the lens through which my work was being viewed, even while attempting a bravado of form. I printed out a draft on the cheap but sturdy Hewlett-Packard I'd lugged down in my trunk from DC, and slipped a folded copy to Claudia Emerson for her to read before anyone else. By the time we sat down to the dinner table that night, I'd ramped up my confidence (aided by a prod from Eric McHenry) to share the poem aloud. Ironically, it would be the one sestina that the BWR editors didn't accept for inclusion in the chapbook, which was published as "Bitch and Brew: Sestinas" later that year. In 2009, Poetry took it instead. In 2015, that poem lent its title to my third collection. I wasn't just drafting a sestina: I was navigating toward the next phase of my career. What a strange gift that Katrina happened to witness it, as part of an early morning's pursuit of birds.

Anyway, all of this is just to be thankful for the generosity shown here. Like most writers, I'm prone to doubt and slippage in my sense of self. I don't think I'm "major league," but it's nice to be reminded that, dammit, I'm still taking my chance at bat.

March 27, 2020

Hill of Beans

Hello, 2020. Weren't you supposed to finally be the better year? I've refused to change my Facebook profile photo since November 2016--the snapshot I took just moments after voting, relatively secure in what I thought that day's outcome would be. I was wrong. So many days since then have felt wrong, especially living just blocks from the nation's capitol, but when you're going through hell you keep going, right?

Now here we are. Last week, I watched a man at CVS steal a single item: a digital baby thermometer. It was the only thermometer left in stock, it was priced absurdly ($46.99), and I was not going to stop him.

My silence has not been for lack of adventuring. Everything has felt in flux. I had a great trip to Tampa--followed by news that the MFA program where I have taught for six years is shutting down. I had a great trip to Knoxville--for a job I didn't get. I was in the 1/3 crowd that made it to the AWP Conference, in part because of sunk costs and in part because I so wanted to see a city that my father's family has always loved. San Antonio was wonderful, with its riverwalk and El Mercado and art and the Japanese Tea Garden and red-pepper mezcal cocktails and BBQ and bluebonnets and Friends of Sound Records. Going to Texas was a reset we needed.

The conference was strangely intimate, with longer conversations, and yet also strangely distanced, with so many less hugs. In a different year, there would have been praise for the benches on the books fair floor and the banks of motorized scooters available for check-out. I hate to think of that momentum being lost, just as I hate to think about AWP losing the service of Diane Zinna. As it was, I was able to take part in "The Future is Accessible," talking in person with Emily Rose Cole and connecting with Jess Silfa and Alice Wong via Skype; I attended three other substantive panels and an offsite reading. That was enough.

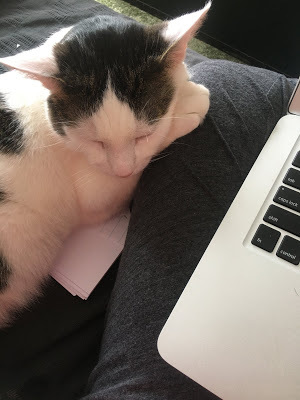

We got home safely, if nervously. That was before everything started getting truly strange. And to counterbalance all this anticipatory grief, one beautiful piece of news: meet Sal the Wonder Cat, who keeps me company while I work from home.

Now we are are hunkered down in our Southwest apartment, the three of us (poet / artist / cat), wondering what on earth we're going to do to pay rent and health insurance in the coming months. Usually, a weekday is punctuated by announcements being piped throughout the elementary school catty-corner to our building, but schools are closed. The red rocking chairs that ring the duck pond are empty. I try to get some fresh air every few days, but between my seasonal allergies and a history of severe asthma, the pollen bloom makes that a questionable proposition. No one wants to feel short of breath right now.

Any in-person events for March, April, or May have been cancelled--and with them, that income lost. I'm hoping to keep leading spotlight discussions for Politics & Prose; a first session to discuss Carmen Maria Machado's memoir In the Dream House went well, and another discussion of Carolyn Forché's What You Have Heard Is True: A Memoir of Witness and Resistance is coming up on Wednesday of next week (April 1). Teaching online isn't easy; I have to multitask between so many different types of attention, and I'm still looking for an effective live-captioning option. But they're deeply absorbing conversations, and that's a bit of a godsend right now.

The only in-person conversation I've had with anyone other than my husband was when one of the workers from Officina ran over with a bag of groceries. With their dine-in options shuttered, they're trying hard to stay afloat. He recognized me from my regular pop-ins to their market, where I usually buy fresh bread and pork sausages. Now they're selling me produce straight from the prep kitchen that might otherwise go to waste: bags of parsley and broccolini, Idaho potatoes, huge onions, and a whole brined hen we'll roast this weekend.

Beyond that indulgence, we're sticking to what's in hand--pasta, rice, canned tomatoes, tinned sardines, bacon, and every imaginable kind of bean and pea. I got really excited because Cento is still shipping their basics. I have a huge jug of olive oil and a stash of white wine. When I was editing Vinegar and Char , I spent a lot of time thinking about the good, sturdy foods we deem essential in times of crisis. Yesterday, as I worked through preparing Made to Explode for W. W. Norton (the manuscript goes to the copyediting desk next week), I paused on this poem, an earlier version of which appeared in the Southern Foodways Alliance's Gravy~

IN PRAISE OF PINTOS

Phaseolus vulgaris.

Forgive these mottled punks,

children burst

from the piñata of the New World,

and their ridiculous names

of Lariat, Kodiak, Othello,

Burke, Sierra, Maverick.

Forgive these rapscallions that

would fill the hot tub with ham

while their parents

go away for the weekend,

just to soak in that salt.

Forgive their climbing instinct.

Forgive their ignorance

of their grandparents who

ennobled Rome’s greatest:

Fabius, Lentulus, Pisa, Cicero

the chickpea. Legume

is the enclosure, fruit in pod,

but pulse is the seed.

From the Latin, puls

is to beat, to mash, to throb.

Forgive that thirst. Forgive

that gallop. Beans are the promise

of outlasting the coldest season.

They are a wink in the palm of God.

November 30, 2019

Odd & Ends & Giblets

Remember when a blog post would just be a round-up of whatever one happened to be experiencing at the moment? I miss those "everything and the kitchen sink" posts. They're a big part of why I still feel so close to a cohort of poets who came up together, posting to blogs en route to their first and second books, in the mid-2000s. So here are the odds, the ends, and (as a nod to the holiday) the giblets.

*

Mayor Bowser has forged a truce with the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities in regards to the Art Bank. But it remains to be seen if the newly minted "Creative Affairs Office" will try to take up what has traditionally been DCCAH responsibilities, and DC is approaching the end of 2019 with still no poet laureate. That makes me sad.

*

Our Thanksgiving break started off with a drive as far as Savannah, stopping off with my husband's old friends--a photographer and a plant designer who does work for Mashama Bailey. We had good food at The Grey Market, the chef's new lunch-counter spot, which serves okra-tomato stew and hand-bottled Bloody Marys. We bought a pack of Benton's bacon to fix in Jacksonville, and a bag of Sea Island red peas for a January 1 hoppin' John.

Our week on Amelia Island has been quiet. A long walk by the sea, during which we found four perfectly whole sand dollars. A day trip to see Jacksonville's museums, the MOCA collection and the Cummer, which had a special exhibition of Tiffany glass. Thanksgiving with four generations of Taylors. A trip to Fernandina Beach, which included taking a chance on a junk shop that turned out to have a treasure trove of stuff--including unopened packs of Garbage Pail Kids cards, circa 1987, complete with the stick of gum inside. We sat down to the bar of Peppers and ordered a round of mezcal just in time to see UVA beat VA Tech in a reasonably epic football game. Then we walked down to the water and watched the pelicans feed off the scraps cast off by fisherman, cleaning their day's catch.

Our week on Amelia Island has been quiet. A long walk by the sea, during which we found four perfectly whole sand dollars. A day trip to see Jacksonville's museums, the MOCA collection and the Cummer, which had a special exhibition of Tiffany glass. Thanksgiving with four generations of Taylors. A trip to Fernandina Beach, which included taking a chance on a junk shop that turned out to have a treasure trove of stuff--including unopened packs of Garbage Pail Kids cards, circa 1987, complete with the stick of gum inside. We sat down to the bar of Peppers and ordered a round of mezcal just in time to see UVA beat VA Tech in a reasonably epic football game. Then we walked down to the water and watched the pelicans feed off the scraps cast off by fisherman, cleaning their day's catch. *

This is the most intense academic fall of my past five years, which is saying something: I've taught in five different spaces in the past three months. But the method behind that madness is always being open to new modes, new audiences. The dark horse that turned out to be a delight was a four-week online course for 24 Pearl Street, which drew on my growing interest in "Essaying in Unconventional Forms"; they use a Blogger platform not unlike this one. The quality of the student work and the ability to organize my time caused me to turn around and immediately pitch a class for the new year. This one will be "Mapping Your Memoir from Start to Finish," and it'll run for eight weeks rather than four. The details are here. I'm really excited about it.

*

I need a new official author photo. I'm not wearing an engagement or wedding ring in the one that gets used now, taken in 2011, which Milly West was kind enough to grant permission for me to use in tandem with publishing Count the Waves in 2015. I hadn't met my future husband yet; you can't tell by looking at the photo, but I can. I'm ready for a photo that shows off the silver streak in my hair.

*

Will we ever go somewhere "on vacation" that isn't tied to a residency or a conference? That's a legitimate question for a two-artist household with no kids. I'm used to working, even when the ostensible mission is to relax, and on a family trip like this one that transforms into cooking dinners for all. So far I've made a pearled couscous pilaf, several salads, fruit curry, and posole verde with tons of green pepper, savoy cabbage, and cilantro, plus a side of black beans with radish greens. My prep generates far too many bowls to be cleaned, a glut of mise en place, but I'm soothed by the process of chopping and sorting. Fortunately my in-laws seem to enjoy the results, and they're patient when a pot of broth unexpectedly takes an extra twenty minutes to come to a boil. In anticipation of making posole, we packed a can of hominy from home, but I'd forgotten just how many ingredients there were to be assembled. My husband saved the day when he found tomatillos at a local supermarket.

Will we ever go somewhere "on vacation" that isn't tied to a residency or a conference? That's a legitimate question for a two-artist household with no kids. I'm used to working, even when the ostensible mission is to relax, and on a family trip like this one that transforms into cooking dinners for all. So far I've made a pearled couscous pilaf, several salads, fruit curry, and posole verde with tons of green pepper, savoy cabbage, and cilantro, plus a side of black beans with radish greens. My prep generates far too many bowls to be cleaned, a glut of mise en place, but I'm soothed by the process of chopping and sorting. Fortunately my in-laws seem to enjoy the results, and they're patient when a pot of broth unexpectedly takes an extra twenty minutes to come to a boil. In anticipation of making posole, we packed a can of hominy from home, but I'd forgotten just how many ingredients there were to be assembled. My husband saved the day when he found tomatillos at a local supermarket. *

My friend Leslie Holt makes amazing art centered on disability, and she just opened an online shop to support her "Neuro Blooms" project. Check it out here.

*

A few years back, I met someone whose profession involved maximizing impact across social media platforms. He'd taken a particular interest in poets and so when I introduced myself, he immediately observed, familiar with my handles--oh, yeah, you're a "burst" person. Apparently that refers to my tendency to post to Twitter seven times in one day, but then go quiet for two weeks; or the way that I post long, substantive posts to this blog of unique content, but I only post them once a month. I suspect that's one of the patterns where return on investment is lowest, but it's what feels right (or at least necessary) for now.

*

John Churchill has passed away. He was my first boss, and he seemed eternally youthful. Not the most auspicious "how I got my first job story," but: I turned up to my spring 2002 Phi Beta Kappa induction at the University of Virginia an hour late, because the clocks had spring forward that morning. John, the newly minted Secretary of national headquarters, was making the rounds to every chapter in the country to lead ceremonies in person. I was so apoplectic with apology that I offered to volunteer time to PBK in the coming year, when I'd be back at home and attending graduate school at American University. I knew they'd just begun offering a poetry award, and I thought they might need help running it.

That turned into an internship, which became the job of Awards Administrator--not just the poetry award, soon defunct, but book awards for writing about humanities, sciences, and literary criticism; a fellowship in philosophy; a scholarship in Greek studies. When John's executive assistant was on maternity leave, I sat at her desk. When the PBK Senate met, I took elaborate meeting minutes that were later, he told me, entirely too editorial for public use (though greatly entertaining on initial read). He modeled a genuine love for the liberal arts that was inspiring, and he made sure The American Scholar got the funding it needed. He was a gentle soul with a big laugh. Nonprofits are odd, often highly stratified places to work, where the shadow of fundraising needs looms constantly. Later, I'd look back and realize that creating a humane environment, under those circumstances, was no small feat.

My MFA program's literary journalism class required an extensive interview-turned-profile. I asked John to sit and talk with me, which he did, his Arkansas drawl unfurling over a Bass ale that he nursed for two hours. My questions were...boring, polite, perhaps overly mindful that he was my boss. I wish I could re-do that interview. I'd ask about traveling to Oxford. I'd ask how to make great pickled okra.

*

In Fernandina Beach, we took a place on a junk shop that turned out to have box after box of sealed collectible cards from the 1980s and 1990s. I couldn't resist a pack of Garbage Pail Kids. I carefully pried open the wax packet, originally priced at 25 cents, complete with stick of gum. They are just as beautifully horrible as I remembered.

October 31, 2019

World Series Champions

My Dad and I have been going to baseball games together for a long time. Long enough that my early memories are of driving up to Baltimore, parking on the other side of the train tracks and walking to Camden Yards, and coming back to find the pennies we'd left smushed by the passing trains. I saw three Ripkens on the field at once. I was there when Cal tied Lou Gehrig's streak of playing in 2,130 games straight.

When the Nationals first came around in 2005, I didn't know how to calibrate my loyalties. They won me over one game at a time--even the ones they lost. My husband and I watched forlorn in a Memphis bar, surrounded by cheering Redbird fans, as the Cardinals took Game 5 of the 2012 NLDS.

In 2015, when we moved to Southwest, going to a game became a quick walk over to the stadium. Baseball became embedded in the texture of getting to know our new neighborhood. Sometimes I headed over for just a few sunny innings, and sometimes I settled in for the long haul on a breezy night. Ryan Zimmerman! Denard Span! Gio González! Wilson Ramos! Even Jason Werth, who wears the beard of an artisanal soap-maker! Max Scherzer seemed to ignite us. I'd never seen so many strikeouts. The day my husband took his friend to see a game, Max pitched a no-hitter.

All of this is to say: I love baseball. I love baseball for the very specific place it holds in the otherwise relentless life of someone who is not very good at slowing down or relaxing. I love the indulgence of getting a beer and french fries with barbecue sauce. I love the talking with my dad or the not-talking. I love singing "Take Me Out to the Ballgame." I love that Anthony Rendon sits on our liquor shelf in a garden-gnome incarnation. I love the season seats we've had for some years now in Section 314, and their view of the field. I love that we're a dorky city with a (slightly) dorky team that runs the presidents midway through the fourth inning. When I think of moving, it's one of the utterly irreplaceable things that has kept me in DC.

When my dad surprised me with the news that he'd been able to snag tickets for Game 3 of the National League Championship, I didn't know what say other than "Yes yes yes thank you yes." We raised our rally towels high. And when Zimmerman, our guy since 2005 (and in many ways, before that, since he's of UVA and Virginia-Beach born), hit a home run in his first at-bat of the World Series, the first home run for any National in the Series, it felt (for the briefest of moments) like all was right and just in the universe.

When my dad surprised me with the news that he'd been able to snag tickets for Game 3 of the National League Championship, I didn't know what say other than "Yes yes yes thank you yes." We raised our rally towels high. And when Zimmerman, our guy since 2005 (and in many ways, before that, since he's of UVA and Virginia-Beach born), hit a home run in his first at-bat of the World Series, the first home run for any National in the Series, it felt (for the briefest of moments) like all was right and just in the universe. Watching Games 3, 4, and 5 from the road was agonizing--I was in Mississippi, my dad was in Hawaii. One loss, we could handle; two we got nervous. Then having to pull Scherzer took the wind out of us. But Game 6 fanned a spark of hope. Not knowing whether we'd win or lose, I shared this poem with my students at American University last night~

BASEBALL

for John Limon

The game of baseball is not a metaphor

and I know it’s not really life.

The chalky green diamond, the lovely

dusty brown lanes I see from airplanes

multiplying around the cities

are only neat playing fields.

Their structure is not the frame

of history carved out of forest,

that is not what I see on my ascent.

And down in the stadium,

the veteran catcher guiding the young

pitcher through the innings, the line

of concentration between them,

that delicate filament is not

like the way you are helping me,

only it reminds me when I strain

for analogies, the way a rookie strains

for perfection, and the veteran,

in his wisdom, seems to promise it,

it glows from his upheld glove,

and the man in front of me

in the grandstand, drinking banana

daiquiris from a thermos,

continuing through a whole dinner

to the aromatic cigar even as our team

is shut out, nearly hitless, he is

not like the farmer that Auden speaks

of in Breughel’s Icarus,

or the four inevitable woman-hating

drunkards, yelling, hugging

each other and moving up and down

continuously for more beer

and the young wife trying to understand

what a full count could be

to please her husband happy in

his old dreams, or the little boy

in the Yankees cap already nodding

off to sleep against his father,

program and popcorn memories

sliding into the future,

and the old woman from Lincoln, Maine,

screaming at the Yankee slugger

with wounded knees to break his leg

this is not a microcosm,

not even a slice of life

and the terrible slumps,

when the greatest hitter mysteriously

goes hitless for weeks, or

the pitcher’s stuff is all junk

who threw like a magician all last month,

or the days when our guys look

like Sennett cops, slipping, bumping

each other, then suddenly, the play

that wasn’t humanly possible, the Kid

we know isn’t ready for the big leagues,

leaps into the air to catch a ball

that should have gone downtown,

and coming off the field is hugged

and bottom-slapped by the sudden

sorcerers, the winning team

the question of what makes a man

slump when his form, his eye,

his power aren’t to blame, this isn’t

like the bad luck that hounds us,

and his frustration in the games

not like our deep rage

for disappointing ourselves

the ball park is an artifact,

manicured, safe, “scene in an Easter egg,”

and the order of the ball game,

the firm structure with the mystery

of accidents always contained,

not the wild field we wander in,

where I’m trying to recite the rules,

to repeat the statistics of the game,

and the wind keeps carrying my words away.

~Gail Mazur

In class, we discussed apophasis, the ancient rhetorical technique with which Mazur convinces us of the very thing she's denying: "this is not a microcosm, / not even a slice of life...." But it is, of course. Right down to the slumps and those left stranded on base. I walked out of Kerwin Hall just as the first pitch of Game 7 was being thrown, and I drove home as fast as I could, listening anxiously on the radio as the Astros homered. We reheated the Ethiopian take-out that I'd gotten on campus and settled in.

My team won. We won a series no one expected us to win, a series that one that no one even expected us to be in, and we won in an incredible & improbable four games on the road. We won after a May low of being 19-31, 12 games below .500. We stayed in the fight, and we baby sharked our way through our embarrassment, and we hustled the bases, and we danced--yes, even Stephen Strasburg--and here we are. And dammit it, that's a slice of the life I'm here for. What a beautiful game.

October 16, 2019

Echoes

One month exactly after losing our cat, Whisky, I had a good if tiring Tuesday that culminated in leading the MFA poetry workshop at American University. Many folks were absent--it's that time of the semester--so we let out a little early, which meant that I spontaneously offered to pick up dinner from 2Amys, which meant that my car found itself crawling along Macomb Street right as the services from Washington Hebrew Congregation let out.

I didn't want to process what I could see in front of me. Squirrel? Must be a squirrel. But a woman coming in the opposite direction stopped her car in the road and hopped out. Bless her for breaking the spell. "This is someone's kitty," she said, scooping up the gray cat and moving it to the sidewalk. She had what might have been a young son in the passenger seat, wide-eyed, so after that she kept going.

At the next intersection, I flagged down a police officer and asked him to go check. I told him the cat might still be alive, and he nodded noncommittally. After I parked I walked back, wondering, and of course there the creature was alone, still and untended, as passersby from the services streamed past along the pavement.

So I knocked on doors. And I rang bells. And I crossed the street, back and forth, looking for someone--anyone--who might answer and know this cat. I couldn't bear the thought of someone emerging the next morning to find the cat there or, worse, animal control coming by and taking the body before anyone knew what had happened.

Eventually, a woman come to the door of the smallest house, the one the cat had been closest to, the one that had a small bowl for kibble on the front step. This was my third try and I was about to give up. Apparently her ringer had never sounded inside, but she'd spotted the lavender of my dress. The moment I even began to speak, she knew. She cried, "Dusty!" The cat had been with her for twenty years.

Her grief is her grief, and it's not mine to display here. But I was grateful to be there with her, in the moment, to help as we took care of things; to feel the cat's light heft in my hands as it was curled into a bed bought not that long ago.

Because this is what humans do, I still went and got the damn pizza, the roasted peppers and anchovies, the rapini. In the moment I had no appetite, but I knew that I would later. I was glad no one asked about my red, swollen eyes.

The next night was another class at American University. I wanted to choose something that dealt with grief, but not of an articulated sort. Undergraduates are just finding their way to naming what makes them feel the way they feel--and you have to be careful not to force it on them. So I reached for this beautiful if puzzling (for some) poem from Kaveh Akbar, "Orchids Are Sprouting From the Floorboards" ~

Orchids Are Sprouting From the Floorboards

Orchids are sprouting from the floorboards.

Orchids are gushing out from the faucets.

The cat mews orchids from his mouth.

His whiskers are also orchids.

The grass is sprouting orchids.

It is becoming mostly orchids.

The trees are filled with orchids.

The tire swing is twirling with orchids.

The sunlight on the wet cement is a white orchid.

The car tires leave a trail of orchids.

A bouquet of orchids lifts from its tailpipe.

Teenagers are texting each other pictures

of orchids on their phones, which are also orchids.

Old men in orchid pennyloafers

furiously trade orchids.

Mothers fill bottles with warm orchids

to feed their infants, who are orchids themselves.

Their coos are a kind of orchid.

The clouds are all orchids.

They are raining orchids.

The walls are all orchids,

the teapot is an orchid,

the blank easel is an orchid

and this cold is an orchid. Oh,

Lydia, we miss you terribly.

~Kaveh Akbar

I often use this poem to talk about contemporary poetry's value on parallel structure, anaphora, and excess. The reaction tends to be polarized--some readers love it, others really resist it. In particular I always enjoy the telescoping of those penultimate lines, as the poem's "camera" seems to zoom in on a particular room and a particular speaker (one with a cold). I was delighted that this time the students found their way organically to thinking of how funerals are often the cause for a profusion of flowers.

Since I didn't want to create an utterly morose atmosphere, I found another way to think about excess: Neko Atsume, the Japanese mobile game of cat collecting. There's a calming quality to cats en masse, even though on another level it's creepy; this resonates with anyone who has been to an island where the feral cat population has surged. I offered a few screenshots toying with the game's premise and outcomes.

...goofy, for sure, but poetry thrives alongside goofy. I was mostly trying not to cry.

September 8, 2019

Pretty Girl, Goodnight

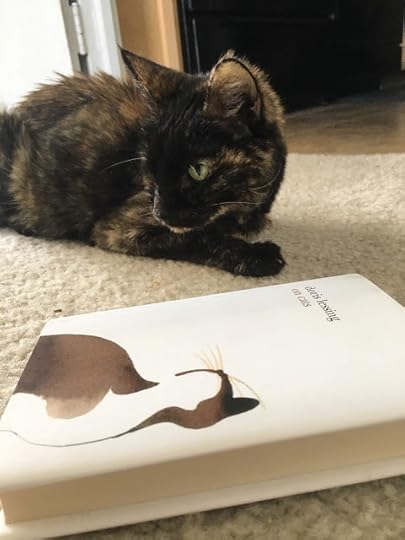

When we adopted, her name was explained has having been a change from "Whizzer." Courtesy her first owner, who had passed away, leaving a nine-year old cat who no one in the family was willing to adopt. The folks at the Montgomery County shelter figured "Whizzer" was an unnecessarily alarm-inducing name, so they changed it to "Whisky."

The name Whisky appealed to me. A quirky polydactyl cat temporarily housed in a vegan warehouse (the shelter had made her anxious) appealed to me. Her photo appealed to me. All these things appealed to my sister, too; independent of anything she found the same cat advertised on Craigslist and wrote me, I think this is your cat. Fortunately my husband agreed, and we had finally moved to a place whose lease allowed a pet. We drove up to Rockville to meet her, this great big Muppet-cat, and the first time I leaned down to look her in the eyes she tapped me nose-to-nose.

From the get-go of bringing her home, she had some medical issues. I'm too exhausted to go into them, except to say that we fought hard. And I've always said to her, since then, hunkered down at eye level: Thank you for staying with us.

Turned out, I needed a cat. I needed company for 2 AM stints of writing or editing. I needed the slow blink, the trill of curiosity, and the oddly conversational vocalizations we shared as I broke the catnip treats in half so she could smell their contents. I needed to watch her discover my husband's gentleness and humor. I needed to know that this household we've created was so filled with love that it could shelter a creature.

I say "creature" intentionally--I've never enjoyed the metaphor of a pet as a child. We didn't meet Whisky until she'd already had a full, mysterious life that included loss of someone she'd probably loved. We chose her. She chose to stay.

I have traveled so much in these past four years: to Florida, to Mississippi, to Cyprus, to Kansas, to Cork, and so on through dozens of 2-3 day overnights. During that time, the simplest check-in with my husband took the form of a texted snapshot of Whisky. He took such good care of her; they had their own rituals. She'd be lounging in the sun, or nibbling, or staring at the camera with a gaze at once penetrating and slightly dismissive. That image told me that all was well.

When the two of us traveled together and made our way across the parking lot, lugging luggage, I'd turn to him and ask, Where's my kitty?

Waiting for you, he'd always answer, and that gave me great joy.

She was an exceptionally handsome cat. Everyone thinks such about the cat they love. But she was a tortoiseshell with 22 toes and a fox-like face.

My sense that Whisky's time with us was drawing short came on about two weeks ago. One night, she settled onto second and third row of pillows behind my head--a favorite spot--first facing toward our closets and then, as she often did, methodically rotating and resettling so she could watch me sleep. She reached a paw out toward me, as she often did, but settled it on my forehead instead of the part in my hair.

The feeling of her cool, cupped paw-palm was at once soothing and unsettling. The only other times she had done that, I've been in tears. Why was she comforting me now? The next night she jolted awake at 5 AM and was inconsolable, wanting the underside of her chin to be stroked again and again, pressing her jaw and cheeks into to my touch. Something had shifted. (Her body, as it turned out, was failing in every way--digestion, metabolism, joints. No point in detail, but it was utter.)

She held on until my husband came home from August at an art colony in Vermont. We had this quiet week together that included familiar rituals. She sat between us on the couch as we watched evening television. She wolfed down some chicken pate. Her energy surged long enough to hunt a few spiders. Friends came, my family came, and she had as gentle an exit as anyone could ask. Tomorrow we'll take her body down to Marshall, Virginia, where the country vets will care for her one last time. I'm so grateful to my cousin Kathy and everyone on staff there.

That first morning when, for whatever reason, I knew, I set aside everything on my to-do list to read Doris Lessing's On Cats. I'd bought the book at Whistlestop Bookshop while in Pennsylvania for a reading at Dickinson College. The bookstore had an in-house cat, a much needed sighting after a particularly intense stretch of travel.

Lessing is of an older generation. There's lots in the book (an aggregate of three essays) that is worthy of skepticism in this contemporary age--everything from the language toward other cultures to the attitude toward spaying and population control. But I found myself deeply soothed by two things, which I'll share here.

One was the unmistakable takeaway that when a household is meant to have cats, it is in designed into the very architecture of the space. A particular cat will come and go, sometimes heartbreakingly, but your attitude toward those events has to respect the loss while protecting the architecture. In other--do it right, as best you can, so that you have the energy to do it again. I've really clung to that principle in these past few days, centering Whisky's passage instead of my grief. Though I'll admit that I pounded a pillow and howled about two hours ago, once I was alone in the apartment.

The other comfort was these paragraphs, quoted from the end of Lessing's book:

What a luxury a cat is, the moments of shocking and startling pleasure in a day, the feel of the beast, the soft sleekness under your palm, the warmth when you wake on a cold night, the grace and charm even in a quite ordinary workaday puss. Cat walks across your room, and in that lonely stalk you see leopard or even panther, and it turns its head to acknowledge you and the yellow blaze of those eyes tells you what an exotic visitor you have here, in this household friend, the cat who purrs as you stroke, or rub his chin, or scratch his head.

...

When you sit close to a cat you know well, and put your hand on him, trying to adjust to the rhythms of his life, so different from yours, sometimes he will lift his head and greet you with a soft sound different from all his other sounds, acknowledging that he knows you are trying to enter his existence...He likes it when we sit quietly together. It is not an easy thing, though. No good sitting down by him when I am rushed, or thinking about what I should be doing in the house or garden or of what I should write. Long ago, when he was a kitten, I learned that this was a cat who demanded your full attention, for he knew when my mind wandered, and it was no use stroking him mechanically, let alone taking up a book to read. The moment I was no longer with him, completely thinking of him, then he walked off. When I sit down to be with him, it means slowing myself down, getting rid of the fret and urgency. When I do this--and he must be in the right mood, too, not in pain or restless--then he subtly lets me know he understands I am trying to reach him, reach cat, essence of cat, finding the best of him. Human and cat, we try to transcend what separates us.

Rest well, pretty girl. You've earned it. Thank you for staying with us.