Ann E. Michael's Blog, page 57

August 1, 2015

What I see

When I trek to New York City these days, I generally go for non-tourist reasons; my sister lives in Manhattan. It’s a day trip, and I don’t always avail myself of visits to big-city attractions–instead, I “hang out” with my sister and her family, which tends to mean home-cooked dinners in her apartment and walks around her neighborhood, greeting neighbors in the coffee shop or on the sidewalk. Often, that’s interesting enough, as she lives near Ft. Tryon Park and The Cloisters. On my most recent visit, however, we decided to take the A train south to tour the new Whitney Museum of American Art. It’s located at the base of the Highline Park, with views southward to the new World Trade Center and westward over the Hudson (making our evening visit gloriously pink-hued during summer sunset).

We spent a little over two hours at the museum, and our initial assessment was that both of us prefer the building itself as an architectural experience over the old Whitney building designed by Marcel Breuer. It isn’t all that much “prettier” from the outside; but the interior gallery set-up is more pleasant, light-filled, and navigable by patrons.

The opening show’s titled “America Is Hard to See,” a line culled from a slightly ironic Robert Frost poem (see an excerpt below). And the top floor gallery included a famous painting by e. e. cummings, so my poetry hopes were raised. The 8th floor of the museum was stunningly curated; I had high hopes for the rest of the galleries though, in the end, my reaction was decidedly mixed.

Thanks to Lederman copyright 2015. See whitney.org

Levels 7 through 5 follow a chronological order, roughly, in terms of historical and cultural developments from the early 20th century to the present. This is a bit arbitrary, as artists alter their styles, and even their genres, over time–and some artists’ work spans decades, gaining and losing cultural momentum as fashions and criticism also change. As a result, there are clusters of pieces that cover similar themes but do not necessarily speak aesthetically to one another on the gallery walls. This was most obvious in the Viet Nam era gallery, which struck me as garish. The purpose in terms of education and theme was fine, but the aesthetics of the room as a display of art just did not convey, to me, what it might have in another perhaps less chronological arrangement.

Nonetheless, as far as getting visitors acquainted with American contemporary art, the new Whitney may be overall more successful than its predecessor. The former building’s galleries were arranged by donor collections and often had too much of the same, or else too little cohesion, and relied on the visitor’s being already reasonably familiar with contemporary art and art criticism. The exterior platforms of “outdoor galleries” (sculptural pieces) are impressive, though you may want to avoid the exterior stairways if you have a fear of heights.

I am happy to note that Calder’s Circus remains on display, along with the old and, by contemporary standards, poorly-produced video of Calder playing with these creations. I loved this piece as a kid and my own children also loved it.

~

Excerpt from “America Is Hard to See,” by Robert Frost

…

Had but Columbus known enough

He might have boldly made the bluff

That better than Da Gama’s gold

He had been given to behold

The race’s future trial place,

A fresh start for the human race.

He might have fooled them in Madrid.

I was deceived bywhat he did.

If I had had my way when young

I should have had Columbus sung

As a god who had given us

A more than Moses’ exodus.

But all he did was spread the room

Of our enacting out the doom

Of being in each other’s way,

And so put off the weary day

When we would have to put our mind

On how to crowd and still be kind.

…

The people on the streets and in the subways and in the neighborhoods were uniformly kind on this warm summer evening. Even when we got in one another’s way. That’s what I saw.

~

July 22, 2015

Clouds

Mid-summer, and the sudden swift storms pass through. Indoors during the excessively warm rains, I try to write a bit. And I play around with clouds on Photoshop.

impasto-like

outlines

~

But the real sky is truer and more beautiful, ultimately.

July 16, 2015

House & home

Falling Water

I went on a trip to visit Frank Lloyd Wright’s historic Fallingwater house, which is located in a forested state park area in the southwestern region of the state where I live, Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania is a large state, and in all the years I have lived here I’ve never managed to get to Falling Water; so I was excited. The day we arrived, the weather was perfect, the water was high, and we toured two Wright houses–this one and Kentuck Knob, one of Wright’s last residential design commissions.

Millions of people tour Fallingwater, so the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy folks (who have stewardship of the property) have their hands full maintaining the place, training docents and volunteers, and just keeping crowd control working. Kudos, by the way. They do a good job. Send them donations.

~

At the café (there’s always a museum café), my partner pointed out a letter reproduced on the informational wall–a note from Mrs. Kaufmann, owner of the house. She wrote that initially the home intimidated her a bit, as Wright’s designs tend to force the homeowner to live the way the house dictates, rather than the other way around. Curtains, a typical decor requirement for a 1930s residence in town, were anathema to Wright. In the middle of Bear Run forest, did Mrs. Kaufmann need curtains? No, she eventually decided–the trees provided color and changing light and privacy and were far more interesting than curtains. What initially seemed too austere for her tastes grew on her; she learned to do with less “stuff” and found that the simplicity made the things she did add to the house seem all the more valuable and aesthetically pleasing. The Kaufmanns must really have been special people to embrace the challenges of living comfortably in one of Wright’s homes, indeed, in his most unique residential design.

~

My husband and I designed our current home 17 years ago and have some idea of the compromises owners have to make, most commonly for financial reasons (that was not an issue for the Kaufmanns, who were department-store magnates). As we toured Fallingwater and Kentuck Knob, one thing that hit us is that building codes have changed the way Americans build; you couldn’t get a Wright home design past most local zoning commissions in Pennsylvania nowadays.

For example, 19″ hallways? Nope. 6′ ceilings? I don’t think so. Some of the tight interior stair turns would be disallowed. And, let’s face it, the whole cantilevered balcony situation would set off a hundred bureaucratic red flags.

~

My house in snow, 2009.

My own house had to agree with the local building code. There was also a budget we really could not exceed. Over the years, we have added to the deck, improved the porch railing, completed building interior doors ourselves, worked extensively on landscaping (first adding to it, then pruning back, then…well, there’s been a bit of mostly benign neglect recently). But we have generally lived comfortably in the house and adapted it to fit our needs, the way most people live in a home. As our living situation changes, with children growing into adulthood and moving away, with fewer pets and no more chickens, with less need for a large vegetable garden, we’re thinking of ways to alter the house. Or even to move out of it, and let some other family have a go at its joys and responsibilities.

Its sensibility leans toward a meadow-type or agricultural feel. That suits the region in which we have settled. Which may be the only way our house parallels Fallingwater: it suits the environment and the region in which it is situated. To me, that is one of the main purposes of good architecture, and the rule most frequently ignored by homebuilders.

~

Our home can boast an improvement over Wright’s houses: it doesn’t leak (I lived in one in Grand Rapids Michigan in the 1970s, and can attest to the leaking factor). :)

~

For a 3-D computer-animated “flyby” of Falling Water and a half-hour documentary on its history, see this page (Mental Floss). Pretty interesting!

July 10, 2015

Buddhism, philosophy, consciousness (poetry)

Sometimes, a startling morning.

A few minutes that feel time-free, when the phrase “Be here now” inheres in the body, the air, the mind, the moment.

Free to recognize consciousness as a grounding, not as an end-in-itself. Part of the world, part of the cosmos.

~

Reflecting, I realize another thing: poetry does that for me, hands me a moment. When I listen to or read a poem, it moves me into a moment suspended in “now-ness.” I am with Seamus Heaney’s father, digging; I watch the horses in Maxine Kumin’s field. The poems that move me do so by allowing me, the reader, to enter that moment or that consciousness, that perspective, which I may or may not relate to, and may or may not layer through perspectives of my own. Yet there I am, in a real way.

~excerpt from “Digging” (see this link for the whole poem, and audio)~

…

Under my window, a clean rasping sound

When the spade sinks into gravelly ground:

My father, digging. I look down

Till his straining rump among the flowerbeds

Bends low, comes up twenty years away

Stooping in rhythm through potato drills

Where he was digging.

The coarse boot nestled on the lug, the shaft

Against the inside knee was levered firmly.

He rooted out tall tops, buried the bright edge deep

To scatter new potatoes that we picked,

Loving their cool hardness in our hands.

By God, the old man could handle a spade.

Just like his old man.

…

contemplation

~

Sometimes the momentary sense of time-free, liberated unity occurs on its own, smacks me by surprise. Or it may arise from mediation, contemplation, or during “mindless” work–such as digging.

Philosophy and criticism tend not to evoke that sort of free consciousness. They require the brain to operate in a different way, a distancing from one-ness; but I like that sort of brain-work because the intelligent and inquisitive people who write, or write about, philosophy, neurology, psychology, and criticism of all kinds offer insights I would not likely find on my own. They ask the interesting questions (it doesn’t matter to me if they do not have the answers).

~

So there’s a balance, right?

~

Poets also ask the interesting questions. Through reading a good poem, I am there in the poet’s moment, curious and uncertain. It is a kind of contemplative practice to read, with an open mind and an open heart, poetry.

(The criticism and the analysis come later. Let them wait!)

July 6, 2015

Back to the garden

June brought much-needed rain, a little late for the peas, which were sparse and small this year, but in time to nourish the later-bearing vegetables. Zucchini and beans abound. It is still too early for the zinnias, sunflowers, and cosmos to bloom; but the butterflies have arrived to check out the buddleia. I recognize that buddleia has become an aggressive invader and is overused in US landscaping–and may not even be a good host for certain varieties of lepidoptera–yet I confess I love the huge purple blooms that draw so many winged creatures to sport where I can watch them from my kitchen window.

~

Speaking of winged garden creatures, I have encountered a new one. New to me, that is. While sitting on my porch, I watched with fascination as a large wasp, carrying a blade of straw in its legs, poked at a hole in the wooden post. The wasp pushed the straw into the hole, then crawled in after it, stayed a few seconds, then flew out. Some minutes later, it returned with a piece of grass and proceeded to repeat the process.

Isodontia, apparently: the appropriately-named grass-carrying wasp. I imagine this insect will eventually crawl its way into a future poem.

Here’s a video of grass-carrying wasps at work from Dick Walton’s Natural History Services site (a terrific resource, by the way). And thank you, Google. It’s this sort of thing that I can celebrate about the internet…my library for all things weird and natural, paradoxical as that sometimes seems.

~

My walkway garden

~

Meanwhile, my perennial beds flourish (with a few too many weeds, ferns, and hostas–but oh well!!). I plan to make pilgrimages to a few gardens further afield later in July. We shall see if the planets align.

And a nod to Joni Mitchell; when I hear the words “back to the garden,” I can’t help but think of her song “Woodstock.”

~

July 1, 2015

Learning the form(s)

I’m extremely pleased that five of my poems appear in the latest edition of Mezzo Cammin, a web journal devoted to formal poetry by women, edited by Kim Bridgford and beautifully designed by , both of whom are excellent poets–of formal verse–themselves.

My poetry often varies as to style; I am not a dedicated formalist, but I feel that writers learn a great deal from experimenting with many styles. Learning to write a sonnet, for example, requires considerable effort and ideally results in the production of many lousy sonnets. Many, many lousy sonnets. Until, one day, the motivation, language, imagery, and form coalesce into a good sonnet. The challenge derives in part from the frame and form the sonnet uses; other challenges arise with sestinas, rondelets, villanelles, haiku, sapphics, and (yes) free verse. Practice does not always make perfect in the case of poetry, but practice helps. One learns the form and its specifics, reads zillions of examples by the best poets, endeavors to write to suit the form, and finds that the resulting effort…fails. Miserably. And then one tries again.

The practice can be meditative, or it can be a kind of discipline. It’s certainly liable to be frustrating at times. I am reminded of my tai chi class, in which I am also tasked with learning a form and practicing its specifics until, after long study, I am not absolutely terrible at the movements. I learn a few more moves, integrate them into the series I have memorized for a couple of years now, and try to get my balance and position down and some grace and flow going. I might add–these are not personal strengths of mine. So it’s difficult.

In addition, my tai chi master teaches us qigong movements, and suggests that we experiment on our own time to invent sequences that work for us. But this is not the same as getting all jazzy and experimental with tai chi; no–in class, and when practicing the form, we students are expected to follow the moves as taught and as closely as we are physically able to do.

Does this mean that when writing in form, I maintain a strict formalist approach to poems?

Um, no–as can be seen in the five “nonce form” pieces in this issue of Mezzo Cammin. Sometimes I start with a standard and jazz it up. This is true for many poets writing today and in the past, because sometimes what we want to express carries an unconventional edge to it, and sometimes the ideas or emotions we want to convey (often mixed emotions or ambiguous ideas that require the reader’s engagement to decide) cannot be shoehorned into the strictest details of the formal framework.

The first of the poems in this issue of the journal is perhaps the most unusual for me–I was definitely experimenting. The allusion is biblical (the parallel verses Matthew 2:18 and Jeremiah 31:15) and the experience is second-hand, and I find the situation deeply sorrowful. Loss of a child–it’s hard not to feel overwhelmed with compassion and unable to know what to do for the mother. In this case, I felt I’d try to convey the ancient sadness in a contemporary setting, a retail shop, probably in some suburban mall. So I am mashing together the old with the new; an experimental set up for the poem just seemed necessary.

I would not do that in tai chi class.

Learning forms for poems–new forms, ancient forms, classic forms, forms from other languages and cultures–keeps a writer freshly informed with the world and engaged with the process of expression through words, rhythm, sound, and imagery. It helps a writer see the perspective of art, the framework, and to see beyond those things as well. Forays into styles, genres, and arts that one has not tried one’s hand at previously present vivid and useful learning experiences. Even if the result is a hundred lousy sonnets or some mediocre watercolors or the worst short story ever written. We learn from mistakes; they are our most relevant teachers.

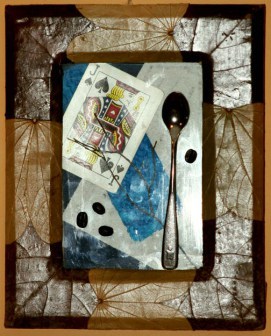

Here, a collage attempt–a collaboration between my then-teenaged daughter and me. Call it an effort to practice a different form (visual art). What is in the frame? The presentation of a line from a famous poem. Let’s see if you can figure it out. [Hint: those oblong dark spots are actually coffee beans.]

Here, a collage attempt–a collaboration between my then-teenaged daughter and me. Call it an effort to practice a different form (visual art). What is in the frame? The presentation of a line from a famous poem. Let’s see if you can figure it out. [Hint: those oblong dark spots are actually coffee beans.]

June 26, 2015

Second brood

This morning, I noticed catbirds engaged in nest building activities. Then I saw mourning doves mating near the garden–must be time for the second brood.

I do not know a great deal about bird behavior; but many of the smaller birds in my region raise two broods, one in spring and one in early summer. My not-very-scientific observation tells me that the second brood is often less successful–that fewer eggs are laid (or hatch). I could be wrong about that generality, but it seems to have held true in my yard for the past ten or 12 years. A little research would inform me, I suppose. For now, though, I am happy to rely on observation.

Sometimes I am eager to track down information (such as facts on songbird reproduction cycles). This week, though, I prefer to spend my time on looking about and writing. I’m working on a kind of “second brood” of new poems, and that is exciting.

I have also taken walks on two urban above-street-level parks, one in New York City (the Highline) and one in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, the Hoover-Mason Trestle Park at Steel Stacks. The former park is pretty well-known; the latter just opened to the public and ought to be better known than it is.

Here’s some information on the site itself from the Landezine website that highlights the work of SWA group on the Sands Casino/Bethlehem City project and some of the challenges:

One of the most prominent examples of redirecting the environmental legacy of a post-industrial landscape can be traced to the south banks of the Lehigh Canal, in the city of Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Comprising 1,800 acres (20 of which belong to this project) and 20 percent of Bethlehem’s total land mass is the former headquarters of Bethlehem Steel Corporation (BSC). Founded in 1904, the company continued to operate until 1998, when US manufacturing divestment, foreign competition, and short-term profit goals finally led to its demise. After almost a century of operation, the effects of Bethlehem Steel’s [1995] closure on the city were heartbreaking, as thousands of jobs disappeared instantly, along with 20 percent of the city’s total tax base. All that remained was an impending bankruptcy claim and the largest brownfield site in the country.

You read that correctly–the largest brownfield site in the USA. The EPA defines a brownfield as “real property, the expansion, redevelopment, or reuse of which may be complicated by the presence or potential presence of a hazardous substance, pollutant, or contaminant.” Acres and acres of said brownfield were left by Bethlehem Steel, and about 20 acres are being redeveloped at present. The park around the steel mill, which follows the elevated trestle around the enormous works, offers a fascinating view at what remains of the United States’ industrial heyday and highlights how significant these mills were. Nice bit of history, nice walk.

I’m not sure these urban parks really move us toward sustainability, but they are at least creative “repurposing” that may help make people more aware of the things that have brought us to where we are today (for good or ill). Perhaps another form of second brood?

June 19, 2015

Diversity. Not.

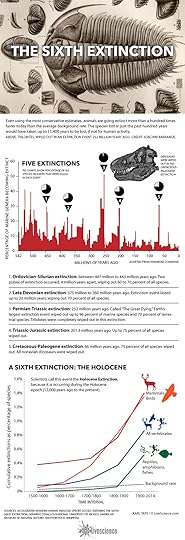

I must admit, it is challenging to read Elizabeth Kolbert‘s book The Sixth Extinction without feeling a bit of dread.

Nonetheless, the book is informative and fascinating–even funny at times–and well worth reading if you are the type who can get beyond your anthropocentric leanings and attempt to view the long-range picture from a scientific, if not exactly neutral, viewpoint. Her main argument is that we are, indeed, in the midst of a 6th mass extinction era and that human beings are “the weed” that most likely is the cause of these numerous extinctions–and not just since the industrial revolution, but eons before that. Humans travel more effectively than almost any life form, and that leads gradually to a loss of diversity. Read the book to find out how that works.

I find interesting parallels with socio-cultural trends in the ecological struggle for and against diversity. Niche-dwelling creatures or societies adapt to some challenging environment and develop or evolve ways to deal with adversity–cold temperatures, constant rain, saline soils, whatever. Nomadism, for example, is a way to adapt to seasonal weather challenges.

When an ‘alien’ enters a niche area, it usually dies off; but if it can adapt, there is hybridism or conquering. Tolerance, it turns out–living peacefully in tandem using the same resources–is not a common evolutionary strategy, though there are examples of symbiotic ecological relationships and, of course, parasitism of the sort that does not quickly kill off the host. Conquering generally means lost diversity.

When a niche organism ventures, accidentally or otherwise (forcibly, sometimes) into a new region as ‘alien,’ the special characteristics of the creature cause it to die or, in some cases, to have to adapt to a different set of circumstances…and diversity gets lost pretty quickly that way.

Does this sound like emigration? War? Forced removal of peoples? Indigenous populations killed off by measles or smallpox? Young people leaving remote areas to try to find work in cities? I see a metaphor here!

While human beings may try to celebrate diversity (which is better than using diversity to identify and exclude or punish “the other”), we probably cannot keep ourselves from becoming, over the centuries, less and less various. A homogeneous world seems, to me, to be a place impoverished through lack of niches and creative adaptation–but that’s what happens when mass extinctions take place: a depletion of kinds in the fossil record.

You might want to read Robert Sullivan’s New York Magazine article for even more recent scientific evidence if you’re not up to reading a whole book, though Kolbert is an engaging writer and I found her book to be a quick read. And below, some graphic illustrations from LiveScience. Fascinating stuff.

Here in the USA, alas, we seem to be helping the extinction of our own kind along by viewing diversity among people as dangerous. Compound this with a society that permits the ownership, hoarding, and use of deadly weapons on others and which cultivates a cultural tone of fear, anxiety, and entitlement, and there is strong evidence that the human weed will continue the slow but decided progress of the Holocene extinction.

Source:LiveScience

June 14, 2015

What does a woman want?

In the medieval poem “The Marriage of Sir Gawain,” the knight gallantly agrees to marry a hag-like witch who has helped King Arthur by giving him the answer to his enemy’s riddle, which is “What does a woman want?” One of several ballad-like story poems of the Arthurian legend, this one appears in Eleven Romances of Sir Gawain (an online scholarly edition is here).

For contemporary intellectual types, however, the person who famously posed that question is Sigmund Freud. He spent many years refining the theory we now refer to as “penis envy” and arguing the displacement theory was at work subconsciously. Far too many casual references to Freud have simplified this idea as suggesting that women want to be anatomically arranged like men.

Um, not exactly…nope.

But back to Sir Gawain, agreeing to marry the hag in order to free his king from the evil baron’s grip. According to the poem, Arthur gives Gawain the secret he has learned from the witch herself. Depending upon the version or translation, the answer is: what a woman wants is her way (or her will, or to have her own way). She wants to be free to decide things that affect her and to make her own choices. Because Gawain is not only gallant and loyal and noble but also no dummy, he remembers Arthur’s secret. When the witch reveals herself as a gorgeous woman and asks him whether he’d prefer to see her lovely by day (when others can see her) or lovely by night (when her husband is abed with her), he defers to her. He says she should choose.

Delighted, she chooses to be lovely all the time (she now knows he will never forget that she has a will of her own).

found @ http://csis.pace.edu/grendel/projf982e/charact.htm…”God Speed” by Edward Leighton

So, if the medieval hag is correct, Freud was right, at least symbolically. Freud dwelt in a culture where men had authority, power, and self-agency, probably also true of medieval European culture, though I’d argue the Victorians were even more constrained. Anyway, women want those things, too–if possessing a penis as part of one’s anatomy could get you those things, one can understand envying the man, if not the organ itself. Indeed, Freud uses a bunch of lengthy theorizing to offer intellectual ballast to what he initially mentioned was an issue of power. Penis=power, in a male-dominated culture. It is almost too simple an idea, and almost too obvious, so he probably felt he had to pack it with a lot of other ideas. Transference and displacement theory have proven useful in other ways, but penis envy just suggests that females too often lack power to make personal choices within a social milieu.

As a feminist who yearns for balance and equality among human beings, I think it is crucial to point out that, despite the stories with which I’ve framed this post, wanting one’s way is not just what women want. It is also what men want.

People, no matter the gender, want to be able to say “No” and to be listened to and heeded. People want to direct their own lives, make their own decisions–and their own mistakes. I work with college students who are 17-22 years old, and I can assure you that they desperately want to make their own choices. Though they often also desperately want to blame someone else for the unfortunate consequences of certain ill-considered choices, they mature once they realize that sort of behavior limits them to the role of the naughty child–a dependent–not a responsible, independent person. If you want to be respected as an adult, I tell my students, you have to be willing to own up to your own poor decisions. And that’s just for starters.

Each young person I teach, tutor, or counsel wants some control over his or her life. Some try to get it by seeking to control other people, others by trying to control their environment, others by endeavoring to control the social situation they find themselves in…the list goes on. Human beings cannot really control as much as we think we can. But we can exert our will and speak up for our way. We can offer respect and seek respect. We ought to be able to make our own decisions as long as we are mature enough to deal with the results for good or ill. That goes for people of any sex.

Yet when a woman asserts that she wants her way, our society tends to judge her as a whiner or a bitch, a ball-breaker or a manipulator. Even now, many years into politically-correct language and Title IX and women as Supreme Court justices, I hear this sort of language bandied about, often “in jest.” Sure, it can be jesting; but it’s also pretty close to jousting–with words. Be a little more careful, my friends. Or as the terminology goes these days, more mindful. Perhaps, given the freedom to exercise our will, more of us will choose to be lovely all the time.

June 9, 2015

Noesis

noesis~

Cognition; perception.

2. The exercise of reason.

Interesting that definition number two is dependent upon definition number one. Lately I have been thinking about the difference between consciousness and conscience; the latter seems to me to be specifically human, I guess, because isn’t conscience a sort of cultural or judgmental entity based upon rules? Yes, I am talking about morality, a term I tend not to use much when I consider cognition, consciousness, narrative, being.

I recently perused Patricia Churchland’s Braintrust and found myself intrigued about where and in what ways morality and consciousness or sentience mesh. Churchland is a moral philosopher, but this book relies largely on arguments premised on neurology, biology, evolution, and animal studies. Her critics pose interesting rebuttals, too. I found her book readable and often convincing–and it’s the kind of book that leads me to other writers and scientists; I love that in a book!

The phenomenology of consciousness–the carbon body brain-based “real world” idea of the word–involves intentionality, sentience, qualia, and first-person perspective. We can identify qualities based upon our first-person consciousness and respond to them. This process has led Western thinkers toward the concept of reason or rational thinking. The exercise of reason derives from perception.

This does not mean that phenomenology is the sole form of consciousness or even that it is necessarily human-only, but it seems to me to be the easiest one for human beings to wrap their minds around. Yet the earlier philosophers were not phenomenologists. Their speculations about what consciousness originated in and what morality inhered in were quite abstract.

For a good sum-up of how contemporary scholars define and discuss consciousness, go to Stanford’s site here.

~

Being cognizant or conscious does not necessarily lead to moral behavior or reason…or does it? Here we have an idea that has been debated for centuries. In her book, Churchland often returns to Hume, who wrote about morality from what, eventually, became known as the utilitarian stance (though I would argue Hume is not really utilitarian). Stanford offers an overview of morality as defined by philosophers over the years; The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy says this of Hume:

In epistemology, he questioned common notions of personal identity, and argued that there is no permanent “self” that continues over time. He dismissed standard accounts of causality and argued that our conceptions of cause-effect relations are grounded in habits of thinking, rather than in the perception of causal forces in the external world itself. He defended the skeptical position that human reason is inherently contradictory, and it is only through naturally-instilled beliefs that we can navigate our way through common life.

These concepts should feel modern to most of us thanks to cultural anthropology, sociology, and psychology, among other disciplines. Hume’s position conflicts with much religious dogma, but his ideas were not out of line with many of his fellow Enlightenment-Era thinkers. During the Enlightenment, intellectuals were enamored of the exercise of reason (noesis).

~

So: consciousness and conscience. First we have the one–however it arises within us*–and the other develops (or evolves?) thanks to the need for social beings to navigate common life. And thanks, perhaps, to brain evolution adapting to social common life (see Churchland for more on this).

Much to mull over during my brief summer break.

~

Jiminy Cricket copyright Walt Disney Co.

* See my numerous previous posts on consciousness!

⇐ “And always let your conscience be your guide!”