Ann E. Michael's Blog, page 55

November 25, 2015

About that death/writing thing

Driving the road that clings to the south side of our hill I notice the round bright moon over newly-gleaned cornfields and find myself thinking about the last essay in Margaret Atwood‘s book Negotiating with the Dead. I finished reading the book some days back, but the title essay worries at me somehow; I can’t let it go. Maybe it is because I perceive connections between her ideas on the ontology of story-making and Boyd’s evolutionary premise for narrative, or between conscious mind and story-making arising from the cthonic, the deeps, the under-earth “hells” to which our myth-makers and shamans, goddesses, musicians, poets and heroes journeyed in order to bring back–if nothing else–the story of the trek and the resulting wisdom. Maybe it is because “negotiating” with the dead raises the problem of consciousness in peculiar and challenging ways as well as the problem of communicating with people of the past and of the future. Or maybe because of that bogeyman that awaits us all: Death.

When I was quite a young child, age seven or perhaps earlier, I was seized with an insomnia-inducing fear of death that kept me in agonies as soon as darkness fell. I wonder if that had anything to do with my later need to “be a writer.”

Atwood suggests that all writers truck with the dead. We read the work of our ancestors-in-the-craft; they are often our first teachers. That important aspect of craft so many of us struggle to attain–the ever-illusive quality of “voice”–is what we notice in many of our beloved writers. Voice, perfect example of metonymy. It stands in for the departed body, the dispersed consciousness.

Here is Atwood holding forth at a dinner party of fellow writers:

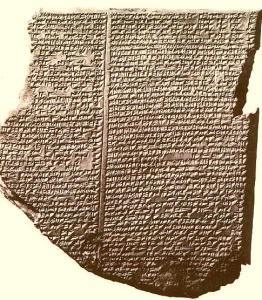

Gilgamesh was the first writer…He wants the secret of life and death, he goes through hell, he comes back, but he hasn’t got immortality, all he’s got is two stories–the one about his trip, and the other, extra one about the flood. So the only thing he really brings back with him is a couple of stories…and then he writes the whole thing down on a stone.

She adds that going “into the narrative process–is a dark road. The poets know this too.” So inspiration is not so much a clearing in the clouds but a kind of rappelling into a cave. At any rate, darkness, even with a full moon to light the road, seems as likely as a bolt of lightning to produce emotionally-resonant work. Maybe more so, because it’s harder work and more ambiguous (Lord knows, writing is both of those!). Darkness requires more interpretation. The audience has to listen, not simply see; the darker path gets traversed by both writer and reader.

The Flood

Atwood also makes note of the threshold concept, that edge or invisible boundary line between the realms, any pair of realms. Life/death, yin/yang, heaven/earth, day/night. The one who seeks knowledge or magic or treasure (or lost love, viz Orpheus) at some point crosses the threshold, and then nothing is certain. He or she may not be able to return, for example. Edges are the interesting places, where all manner of things mesh and overlap–good spots for inspiration even if one opts not to take the stairway to the underworld; but they also pose danger. We humans, with our need for communities, invent parallel communities for our dead, not just physical cemeteries but supernatural abodes, and create all manner of “rules and procedures…for ensuring that the dead stay in their place and the living in theirs, and that communication between the two spheres will take place only when we want it to,” says Atwood.

I wonder if that is one reason I felt so unsettled by the idea of death when I was seven. I did not personally know anyone who had died (yet), but I knew the stories; certainly, I’d been taught about Jesus, though I was told he had defeated death. So why the early-onset angst? Did I fear that edge between the realms, being too inexperienced either to navigate it or to allow communication on my own terms? And maybe the fear is precisely what has led me to my ongoing inquiries into philosophy, consciousness, art, and mind.

Or was I precociously aware that I would have to venture into the darkness, into the coffin-holes and the caves and the seas’ depths, if I wanted to come back with a story to tell?

November 19, 2015

Slightly less difficult books

I recently read Paul Bloom’s book Descartes’ Baby while simultaneously reading Daniel Dennett’s Content & Consciousness. Of these two, the latter falls a bit under the “difficult books” category, but it is not too hard to follow as philosophy goes. Dennett’s book is his first–the ideas that evolved as his PhD thesis–and in these arguments it is easy to see his trademark humor and his deep interest in the ways neurology and psychology have aspects useful to philosophy. Bloom’s book, a somewhat easier read, suggests that the mind-body problem evolved naturally from human development: young children are “essentialists” for whom dualism is innate; Descartes simply managed to write particularly well about the evolutionary project (with which, I should note, Bloom disagrees; as a cognitive psychologist, he maintains a more materialist stance).

I recently read Paul Bloom’s book Descartes’ Baby while simultaneously reading Daniel Dennett’s Content & Consciousness. Of these two, the latter falls a bit under the “difficult books” category, but it is not too hard to follow as philosophy goes. Dennett’s book is his first–the ideas that evolved as his PhD thesis–and in these arguments it is easy to see his trademark humor and his deep interest in the ways neurology and psychology have aspects useful to philosophy. Bloom’s book, a somewhat easier read, suggests that the mind-body problem evolved naturally from human development: young children are “essentialists” for whom dualism is innate; Descartes simply managed to write particularly well about the evolutionary project (with which, I should note, Bloom disagrees; as a cognitive psychologist, he maintains a more materialist stance).

It turns out that because I have read widely if shallowly in the areas of philosophy, cognitive psychology, evolution, art, aesthetics, and story-making, I find myself able to recognize the sources and allusions in texts such as these. Quine, Popper, Darwin, Pinker, and Wittgenstein; Schubert, Kant, Keats, Dostoevsky, Rilke…years of learning what to read next based on what I am currently reading have prepared me for potentially difficult books. [Next up, Gilbert Ryle and possibly Berkeley.] I don’t know why I feel so surprised and happy about this. It’s as though I finally realized I am a grownup!

And I am glad to discover I am not yet too old to learn new things, young enough to remember things I know, and intellectually flexible enough to apply the information to other topic areas. Synthesis! Building upon previously-laid foundations! Maslow’s theory of humanistic education! Bloom’s taxonomy! The autodidact at work in her solitary effort at a personal pedagogy.

If I ever really discover what consciousness is, I’ll let you know.

November 7, 2015

Change

Goldfinches in winter attire

Two kinds of chickadees (black-capped and Carolina). White-breasted nuthatches. A tufted titmouse, bluejays, goldfinches in their brown-ish phase. The winter birds have arrived; despite a strangely warm November, the birds molt into dull plumage or migrate on schedule. I try to remember that when I feel worried about climate change: some forms of life are adaptable, change is normal, anxiety accomplishes nothing, and right action is possible.

I do not mean that we ought to ignore changes, especially those for which we have been responsible. When human beings get concerned enough to act, there’s a great deal of harm we can undo.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, people in the USA became anxious about pollution. I am old enough to recall when New York City’s famous skyline was obscured by a yellowish-gray haze almost every day. Days we could see the Empire State Building shining in sunlight without smog were rare. Chinese cities today are having with polluted air were true for the citizens of Los Angeles and New York fifty years ago, but we took action–surprisingly enough–and eventually state and federal regulations required that technology be implemented to ease the problems technology had created.

This process was not speedy or easy, but it worked. I visit New York fairly frequently, and the sky is almost always smog-free. My now-grown children have never seen the skyline hidden under layers of air pollution.

Things changed.

Can humans undo the damages we have wrought to our oceans, air, rain forests, mountains, deserts, rivers, planet and its climate? Probably not–not all of it, certainly–and I doubt there is much we can do to stave off the “sixth extinction.” We have to accept we are part of the change, for good or ill, and to find ways to do less harm in whatever time remains to us–to activate compassion.

~

Meanwhile, I await the juncos. They usually arrive around the first week of December.

November 1, 2015

Dozens of views

No one has ever found the traces of memory in a brain cell. Nor are your imagination, your desires, your intentions in a brain cell. Nothing that makes us human is there.

Chopra is not my favorite writer on consciousness, but he does an adequate job of explaining complicated concepts to people who are just getting accustomed to questioning experience and who are beginning to be open-minded about the mind, the body, and beyond. So often, we have been raised not to doubt, told what God is and is not, and trained into beliefs about the truth. This, in spite of the common human trait of curiosity that asks: who and where are we in the world? What makes me me? What happens when I die? Chopra, with his medical background and his experience spanning several major cultures, can offer both a great deal of information and pose provocative questions to his readers.

In our technologically-obsessed culture, it is easy to turn to science as foremost authority; I happen to be fascinated by neurology and neuropsychology when it comes to consciousness, for example, but I never rule out so-called spiritual insights. Chopra’s writing often falls into the fallacy of stating “there are two views,” when in fact there are dozens of views, even among scientists. My guess (it is but a guess) is that the either/or form of presenting perspective is simpler for the “average reader”–as defined by his editor–to understand. Yet it seems to me a slight to the average reader to narrow these big questions down to “two views.”

Here’s an example, just one of many in his writing:

There are two views about consciousness in science today. One is that consciousness is an emergent property of the brain and. therefore, also an emergent property of evolution. That’s the materialist, reductionist view. There’s another view…[that] holds that consciousness is not an emergent property but inherent in the universe.

Now, I genuinely prefer what Chopra calls the “mind first” argument in which consciousness is a kind of field effect. I would not, however, suggest that matter first and mind first are the only two views today’s scientists hold; and neither would anyone else who has read a number of the elegantly-argued, well-researched, thoughtful, passionate blogs of today’s science researchers. The majority of them are atheists, but some are agnostics and some are inclined toward non-theist teachings such as Zen. Even among the ranks of non-believers (in terms of an anchoring eternal presence or god), the question of consciousness leads to intriguing inquiries.

The philosophers of today cannot ignore scientific advances any more than Maimonides could in the 12th century. Physics is a thing! as my students might put it. For the ways in which this relates to the science of neurology, I return to the framework on consciousness proposed by Douglas Hofstadter in his book I Am a Strange Loop.

What is the world but consciousness? Or illusion, in Hindu and Buddhist teachings (Maya) and, in a slightly different but related way, in Plato. And how many perspectives are there on that consciousness?

Chopra would probably say that each of us has to experience a state of awareness and interaction with whatever deep potential “god” or the creating principle offers for us. Which basically admits of not merely dozens but billions of unique interactions or perspectives…if we even agree to the schema.

goldenrod (solidago) going to seed

October 27, 2015

Work vs. work

Outside Academia: The Writer…

Outside Academia: The Writer…

Lately, I have felt overly-occupied with my so-called day job. The work I do at the college is personally rewarding and pays my bills; I love the challenges it offers and the people with whom I work, but I am not what one would term career-driven. Even though I am employed by a university, and even though I teach (just one class a semester), in many ways–as far as scholarship, research, and poetry go–I remain “outside academia.” An interesting paradox. But if I over-extend at my office, I find less to say at my writing desk at home.

Poets Mary Oliver and Kay Ryan also spent most of their careers working at colleges without climbing the spiral stairway of academia’s ivory tower. Well-received, excellent writers–and Oliver even sells quite well for a poet–they aren’t “academics.” It is heartening to know that such poetry luminaries are, like me, not academics. I often wonder how they managed to balance teaching with writing poetry.

~

What I do “at work” where I earn a salary, and what I do when I “work” on poetry, seem quite separate to me, and I question whether one informs the other. I feel that being a poet does influence, though subtly, the way I approach teaching and tutoring. (It does not seem to have any influence on the way I do record-keeping, spreadsheets, or paperwork.)

By contrast, my day job at the college seems not to have much sway over my poetry; I write prose about teaching and tutoring, but my career work does not often appear as topic or substance in my poems. I notice, too, that Oliver and Ryan do not often write poems about their day jobs (both of them have retired by now–but still). In fact, I would venture that the way my day job affects my poetry is mostly as a time and energy drain.

~

I have challenged myself to write at least two poems a month that in some respect relate to my work with students. That prompt forces me to remember that I am not two separate beings, one at the college desk and one, pen in hand, on the back porch at home. I remain my whole self, and I place my whole self into both endeavors. I can work with that.

October 22, 2015

Clouds & trees

One benefit to living where I do is the way the sky looks in early autumn. Another is the brilliancy of leaves as they change color.

This time of year, even my commute to and from work offers moments of beauty. There are sunrises as I get ready for work, sunsets as I drive home each evening. The skies have been so glorious lately that a friend of mine posts photos on his social media account every day. Autumn arrives, and I wish I were a painter.

Cloud textures: yesterday morning, stippled so densely I could easily imagine ice crystals clustering together in the atmosphere a thousand feet above me. Bouncy puffs, striations, streaks. Today, a more consistent palette of repeated half-rounds. A stream of grey, white, and slate blue overhead, highlighted with thin bands of yellow.

Meanwhile, the trees–first the hickories going golden, then other tints. Today, I noticed the scarlet of a tupelo aflame at the edge of a field and the first big sugar maple shifting to orange. Many of the smaller ornamental trees take on burgundy hues. I can’t describe these landscapes in words! I want words to be pigments. I feel stalled. Maybe I am just making excuses for why I have not been writing poetry lately–(I don’t want to confess to writer’s block, as obviously I am writing!)

Here’s a nice video from Slate that speculates, based on recent science, about why there are more red colors in North American trees than in European trees. Click here!

October 16, 2015

Focus

On what do I focus when I write a poem?

This question has occurred to me before, usually under the guise of someone asking the ever-vague “What inspires you to write?” Focus differs from inspiration. For me, focus seems to derive from observation and is a process of discovering meaning.

Focus helps me understand what it is I’m experiencing and to decide how to express it. I focus when I need to make decisions; in the case of writing a poem, the decision might be one of craft approach or of imagery, or a realization that the poem needs a turn to create tension or resolution. What is the hub of the poem, the real kernel at its core? To make a poem “work,” I have to have a sense of what that might be.

This type of emphasis is a form of concentration. I think we learn from focusing; it teaches the value of close study, a skill needed for analysis. It can also be a reminder of what is outside the area of attention. Focus needs context, or it ends up as navel-gazing.

http://www.npr.org/2015/10/08/446731282/sculptor-turns-rain-ice-and-trees-into-ephemeral-works

For a visual example, consider Andy Goldsworthy‘s “Rain Shadows,” which are among the most transitory of his ephemeral works.

The opposite of making a snow angel, in these conceptual art pieces–and he would object to me calling them by that term–the artist lies on a sidewalk and waits until a light rain falls just enough to leave his figure on the ground. Of course, in no time, the rain fills in the figure, so he documents the “shadow” with a photograph.

Goldsworthy talks about the process, in a recent interview with Terry Gross (see link below).

I just concentrate on the rain. I’ve learned so much about rain — the different kinds of rains, the rhythms of rains. And people will say, “Oh, why don’t you just use a hose pipe?” That would be totally pointless. The point is not just to make the shadow, it’s to understand the rain that falls and the relationship with rain and the different rhythms of different rainfalls.

The “art” in Goldsworthy’s rain shadows–he also does this with snowfall–consists in a focus, a learning, a process that the viewer cannot participate in. Which is kind of weird. Unless, of course, seeing his rain shadows prompts other people to try making them, during which they will learn about rain’s rhythms and varieties.

In this way, Goldsworthy encourages focus and close attention to the world in which we live. I think I will file that under “inspiration.”

For the podcast: http://www.npr.org/player/embed/446731282/446931348

October 10, 2015

Empathy & compassion

Quan Yin, bodhisattva or goddess of compassion; the Chinese interpretation of Avalokiteśvara

Sensitive. Or: oversensitive.

These are terms I hear bandied about to describe people who react deeply to anything from wool clothing or sock seams to sarcasm or “charged language.” When I was a child, people told me I was sensitive; initially, I thought that was a kind of compliment, and sometimes that was the intention. The teenager I once was believed that sensitivity made me empathetic and compassionate.

As I matured, however, the term sensitivity took on more negative connotations of the “can’t you take a joke?” sort. Worse yet, the charge of sensitivity came loaded with accusations of narcissism, as in “you take everything personally.” In today’s phraseology, “It’s not all about you.” Under those terms, sensitivity does not resemble empathy.

Empathy is a feeling-response, true. It appears to have a like-kind relationship to sensitivity–but a person must be sensitive to others’ experiences in order to feel empathy; so the similarity’s not as swappable as it first seems. I thought that my feeling-response signaled that I was a compassionate person. Indeed, fiction elicits empathy in me. A lifelong bookworm and early addict to novels, I definitely feel along with the characters of the stories I read. Is it really the experience of others that makes me weep or feel joy as the characters forge through lives such as I will never be able to encounter? Or is it a feeling response to damned good writing?

I ask myself these questions because, given my inquiries into what consciousness is and what poetry does, it seems I have not made clear to myself the differences between sensitivity, empathy, and compassion.

~

My current thoughts on the differences have evolved through reading and writing poetry, not fiction, and through getting older. Nothing like life experience to knock a person’s youthful errors into strong relief.

Here goes:

Sensitivity is the strength of a person’s reaction. That reaction may be physical or emotional and will vary widely from one individual to another.

Empathy always means that one “feels within” another person (from Greek empatheia em- ‘in’ & pathos ‘feeling’); it is an inward response to external stimuli. As Daniel Goleman notes, there are several types of empathy psychologists have identified–here’s a brief article on that topic.

Compassion, while a noun, must be active. I think of it as behavior, as action, as verb in noun form. It is a response or reaction to suffering in others (empathy) that is accompanied by an urgent desire–the word desire isn’t strong enough to convey the feeling–to help alleviate the suffering.

That’s where the activity comes in. Until I feel a desire to act, I am “merely” empathetic and sensitive.

~

Recently, I have begun to recognize that my desire to write poetry is partly compassion-based. Art of any kind is process as well as result, and process is action. Additionally, my career as an educator has compassionate action structured into the job description. There are other ways we–I–can be compassionate in the world. This matters to me.

We can learn from the practice of tonglen: “Breathe in for all of us and breathe out for all of us. Use what seems like poison as medicine. Use your personal suffering as the path to compassion for all beings.” ~Pema Chödrön

And we can live in the world and begin to use our sensitivity to pain, and our sense of empathy, to activate compassion–as a verb.

October 4, 2015

Safety

I work, and sometimes teach, at a college campus–a small, quiet, safe university surrounded by cornfields and lightly-wooded slopes. The institution has a manual of protocols to ensure the safety of staff and students: lockdown procedures, early alerts, advising on harassment, threat, and signs of various types of needs along with preventive measures, communication protocol, background screening, and referrals. The administration has taken pains to assure the safety of students, faculty, and staff.

It seems that one of the most urgent desires of U.S. citizens is to be safe. We spend millions of hours and dollars on the quest to protect ourselves and our communities. We argue over whose responsibility that should be, though most of us recognize the responsibility–as in any social group–must be a shared one. After last week’s mass shooting tragedy, one Oregon college professor posted an open letter to her legislators (click here for story). Her situation parallels my own except that I have been at my college for many years and am aware of the protocols. But those procedures would be just as useless in my classroom as she envisions they would be in hers.

From a June 2015 New York Times article reporting on the Texas campus-carry legislation: “Opponents say the notion that armed students would make a campus safer is an illusion that will have a chilling effect on campus life. Professors said they worry about inviting a student into their offices to talk about a failing grade if they think that student is armed.” Most lawmakers have never been teachers. I think it unlikely they are aware of the stress and apprehension most of us feel in addition to our interest, concern, and compassion when dealing with a “difficult,” angry, or excessively anxious student. Yet we do not let our fears keep us from doing the jobs we love, disseminating what we have learned through study and experience to others and (usually) actively seeking their engagement in the discipline. That means taking intellectual risks. Occasionally, it means making oneself vulnerable to physical risks as well.

I am not suggesting there is something wrong-headed about wanting to feel secure; certainly that need is basic among human beings, keeping us in groups banded together for safety. But I do wonder whether the craving for safety distracts people from exploring and implementing other, perhaps more helpful, methods of operating as a society. To do so would require rejecting the norm, stepping away from the way we generally tend to do things (the way they’ve “always been done”) and endeavoring to create new approaches to our social maladies.

What might that look like, from the professor’s point of view? Or from the politician’s perspective, or a parental viewpoint? And are we, collectively, ready to take those risks?

photo, Patrick Target. Mary Mother of God statue above the campus.

September 29, 2015

Interpretation & finesse

A few months back, I heard from an editor who rejected a poem I had submitted. He said that the editors really liked the work, but that the journal generally did not publish “poems about poetry.” The critique was especially surprising to me because I didn’t realize that my poem was about poetry; the editors’ interpretation of my text was different from my own!

It is interesting to re-read one’s own work from the viewpoint of a reader who is not oneself. Actually, that’s an impossible task, but I tried. My interpretation of my poem is that it is a somewhat speculative, perhaps philosophical piece concerning the re-envisioning of the commonplace. Nonetheless, it is not an abstract poem on the surface. My poetry inclines toward physical imagery, often nature-based (no surprise to readers of this blog…). When I distanced myself a bit and tried to imagine what another reader might make of the poem, I could see that there would be a way to interpret the piece metaphorically as a reflection on the writing process.

That’s not what I thought I was writing, but the interpretation works just fine. Who knows, maybe I was kind of writing about writing, and it took a thoughtful critique by some editors to figure that out!

~

Which brings me to the whole topic of interpretation. I am not teaching poetry class this semester, but that does not mean I am not trying to impart to my students an understanding of what it means to interpret a text. The aim of any composition & rhetoric course is to assist students in learning how to express their original thoughts about a topic–any topic–and to ground those thoughts in evidence: in other words, to validate the student’s interpretation.

That process involves analysis, argument, inference, sometimes research, and composition whether the text the student responds to is literary, persuasive, commercial, visual, auditory, performatory, or digital. Critical thinking requires inference and metacognition. These tasks are harder than they seem; most students do not develop those abilities overnight and need a bit of coaching.

Then there are students who are capable of thinking analytical thoughts but are at a loss for how to express them on paper (or on word-processing software). That ability also requires a bit of coaching.

It can be difficult to ascertain whether a student I am tutoring needs help with the thinking or help with the expressing. Too often, early in my career as a writing tutor, I have inferred incorrectly about a student’s difficulties with the written word. Coaching takes finesse. Finesse takes awhile to develop.

Come to think of it, interpretation requires finesse as well. When a critic bludgeons a poem to pieces, the interpretation gets lost in the analysis (and critics can even bludgeon poems that they love).

I am glad that the above-mentioned editor read my poem with considerable care and finesse. He may have decided not to publish it, and he may have interpreted it differently that I would have myself, but he took the time to interpret. It is encouraging to know that my work has been read with such care.