Ann E. Michael's Blog, page 28

February 13, 2020

Garden painting

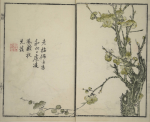

The image on the right is from a book in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Department of Asian Art, available through its new digital collection of Japanese illustrated books. It is written in Chinese, however: Jieziyuan huazhuan; Kaishien gaden 芥子園畫傳 and is catalogued as The Mustard Seed Garden Painting Manual (3rd Chinese edition): [volume 3]. I do not read Chinese, but I think the drawing must be of quince in flower. My photo of pink quince blooms focuses on a particularly floriferous branch; in fact, the quince in my back yard is thorny, broken off in places, and often a bit scarce as to blooms–more like the drawing.

The book itself is interesting. It demonstrates and describes how to paint these shrubs. The sketches show the stems as the initial composition, with gaps where the blossoms are later to be painted. Then the blossoms get painted in, and then ragged lines of twigs and thorns to complete the painting. Since I cannot read the text, I interpret the stages from the drawings.

It occurs to me that this approach–one of guessing the stages–feels familiar. It resembles literary criticism; and it resembles the process of reading and re-reading a poem to try to determine its making, which is usually hidden since it takes place in the mind of the poet as she revises.

[image error]

note the gaps…

An analogy here: when I first write down the phrases, images, “inspiration” (if you will) for a poem, there are gaps. These lacunae appear in several forms, sometimes as spaces or blank spots in a sentence, sometimes as an unsatisfactory placeholder word, sometimes as a dash or ellipsis. These marks, or lack thereof, act as reminders to revise, rethink, resolve missing links or relationships in the poem’s developing ovum.

~

Winter makes for gaps. Skeletalizes the trees. Snowfall temporarily erases the known. Clouds cover sun and moon. Even the songs of birds, mostly absent.

As David Dunn, my long-dead friend (another emptiness), would sigh during moments that conversation became too intense or too difficult: “Anyway…”

In a temperate climate, we do need winter. The birds will return.

[image error]

~

when sap runs red

forcing budding trees into blossom

mating time

~

February 10, 2020

Apology

Speaking of February, here’s a poem trying to make amends for my dislike of the briefest month. This apology appeared in Prairie Wolf Press Review*, and I may include it in my next collection (whenever that may be).

~

Apology

For years I have held February

answerable to many sorrows

as though the month itself

were responsible for its appearance:

the dour days too short, long nights

steeped in frosty bitterness.

Resigned to hibernation,

February made me sleepy.

Dulled my skin, sucked dream

into a cold vacuum

like a vacant acre of outer space,

a stone of ice upon my chest.

But today, I watch a small herd

of yearling deer file gingerly along

the hedgerow over crusted snow

and sense thaw within.

The days, brief, are nonetheless

beginning their shadowy

stretch into spring. It is the month

owls urge themselves

toward mating, their querying calls

strung along night’s bare branches;

the month buzzards return

from foraging the more southerly dead.

Skunks break dormancy amid

tussocks of snowdrops;

sometimes, the hellebore blooms.

I have been observing February

from all the wrong angles.

No, this is not the wild greening of April

nor the fragrant abundance of June,

but it is something that deserves better

than repudiation or scorn.

To February, which has given me much

besides unhappiness, I offer my apology.

~

~~~

*Prairie Wolf Press seems to have folded, alas.

February 5, 2020

29 days

I am trying really hard to learn to like February.

I already yearn for these blooms, which often open this month:

[image error]

snowdrops photo by Pixabay on Pexels.com

[image error]

Indeed, the snowdrops are emerging slightly; I see hints of white amid the tufts of deep-green leaves. The winterhazel buds haven’t really swelled just yet, though. Some years, we have hellebore and dwarf irises in February–it isn’t entirely drab, grey, chilly, and wet for 29 days. Reminding myself of that helps a little. Why, we had one warm and sunny day earlier in the week! The flies and stinkbugs buzzed about drowsily, and the birds made a little more noise than usual.

But part of me says–oh, wait a bit. There could be plenty of snow in March.

[image error]

March, 2018

How to allay the anticipation-stress that sits heavily on me, body and soul, this month?

J. P. Seaton’s translation of Han Shan (I own a copy of this book):

There is a man who makes a meal of rosy clouds:

where he dwells the crowds don’t ramble.

Any season is just fine with him,

the summer just like the fall.

In a dark ravine a tiny rill drips, keeping time,

and up in the pines the wind’s always sighing.

Sit there in meditation, half a day,

a hundred autumns’ grief will drop away.

~

I am not much for sitting in meditation, but Han Shan suggests it might do me some good–so that the griefs fall away, so that any season is “just fine” with me.

Worth a try…

–anyway, it’s a short month.

January 31, 2020

Cover reveal

[image error]

Coming this spring from Prolific Press.

~ ~ ~

[image error]

January 22, 2020

Observation, memory, & art

Simon Watts has died. Probably you have not heard of him. His father, Arthur Watts, was a talented illustrator for the British magazine Punch, among other publications. My readers are unlikely to be familiar with him, either. His sister, Marjorie-Ann Watts, is an illustrator, novelist, and memoir-writer in the UK. Her books are not readily available in the USA, so my readers probably do not know of her, alas. Simon’s maternal grandmother was Amy Dawson-Scott, aka “Sappho,” poet, novelist, and British literary hostess who founded English PEN. If you have not heard of her, you may have heard of PEN International, a major writers’ organization.

Oh, such interesting relations and associations!

Simon, who turned 90 a week ago, needs an elegy–but I cannot write one, at least not yet. We have been friends for 35 years; and even though he hasn’t lived nearby, we will miss his presence in our lives because he corresponded well. He sent letters, and emails with memoir documents attached, and photos. He kept up with our children even into their adulthood. He called us. We visited. He told the best stories–always mirthful and full of twists. He wrote articles on sailing, boatbuilding, furniture-making, and sent little essay-type memories to his friends and family.

He hailed from England, emigrated to the US in the 50s, and loved Nova Scotia, San Francisco, and Portugal. He has family in the US, Britain, and Australia.

~~

I was scouting about the internet looking at his work and his family’s stories and came upon his father’s article on drawing in black and white, written in 1934 about a year before Arthur’s early death (he died in an airplane accident). This section struck me as so relevant to my own understanding about both sketching and writing–good writing, poetry, journalism–is also, foremost, about observation and memory.

Speaking of memory and observation, how much I wish that I had trained mine more. How I wish I had employed that excellent method of looking at an object, going into another room to draw it, returning to refresh my memory, and so on, until that drawing was completed without it and the object ever having met, as it were. What a training for an artist interested primarily in character, who sees for a minute a face which, if he cannot draw from memory, he will never draw at all!

I believe I am right in saying that, ages before such a thing as photography was even guessed at, this was the method by which Chinese artists were taught … So developed did their powers of observation and memory become by this training that by shutting their eyes, opening them for the fraction of a second, and shutting them again, they could keep in their minds the visual image of what they saw long enough to be able to transfer that visual image to paper. It was in this manner that they were enabled to draw insects and birds in flight, and it is an indubitable fact that, when the camera was invented and ‘instantaneous’ pictures were produced, it was proved by comparison that these artists’ memorisations were perfectly accurate.

I tried that method myself, but, having no stern master to goad me on and, alas that I should have to say it, being constitutionally lazy, dropped it; for it is the most exhausting form of study that I know.

~~

Simon Watts, the son of this artist (a man he barely remembers), inherited somehow–though expressed in an entirely different way–the recognition that we ought to note carefully and recall the world around us, revel in our memories, and share our knowledge and wonder in whatever ways we can.

He saved historic wooden sailboats by carefully measuring them, building his own versions, and reproducing his designs for others to build.

In the photo below, my daughter, at age 14, happily sails the Atlantic off the coast of Nova Scotia in the boat that graces the cover of his plans for Building the Norwegian Pram.

[image error]

Such memories fall into the category of immeasurably valuable. Right now, this photograph takes the place of any elegy I could compose. Sail on in peace, Simon!

January 15, 2020

Peace & starlings

The new year has certainly begun with bangs and whimpers.

During the strangely mild weather, as snow geese and buzzards return but before the juncos leave us, I have been watching the flocking behavior of starlings.

For lack of anything more relevant to write at this time, I’m posting here my poem “Liturgy,” circa 2002 or 2003, from Small Things Rise and Go.

Peace.

~

LITURGY

We will not know peace.

Hay clogs the thresher,

Snow stoppers thruways.

Starlings haggle out the morning.

Red fox probes her muzzle

Into the voles’ weed bunkers;

Harrier screams over moors.

We will not know peace.

Here, the caterpillar

Tires chew fields into slog;

Here a child’s toy erupts

Into a village of amputees.

Sands shift under an abstraction,

The sea grows warm.

We will not know peace,

During our lifetimes, the tines

Break, the cogs slip,

Polluted slough impedes

Our efforts at contentment.

Our own natures

Bully us down: Peace—

Peace to those who do not know peace.

To the fieldhand knee-deep in grain.

To the broken doll clasped by a broken child.

To the small-time fisherman far at sea.

To my mother with war scrawled through her

To the empty church, the hill of snow, evening—

That may never know peace.

[image error] [image: Wikipedia]

January 10, 2020

Practice & Muse

For people active in the arts, “creators,” the concept of the Muse is familiar–we read or hear about her often, sometimes in laments bemoaning her abandonment of the artist. May Sarton mentions needing a Muse to write poetry; in Sarton’s case, the Muse had to be an actual person, someone intellectually and sensually stimulating. For other creative types, the Muse is metaphorical, or acts as an aspect of a ritual to invoke inspiration, or as a method of removing writer’s block.

I rather like the idea of the Muse, as myth and metaphor; sorry to report, though, that I cannot recall a time when I felt I actually had a Muse. For writer’s block, I might have turned to Lord Ganesha, Remover of All Obstacles–but as I age into confidence as a writer, I find more patience with myself when the words don’t flow as rapidly.

[image error]

Dancing Ganesha. [wikimedia/creative commons: 123rf.com]

I seldom think of myself as “blocked” anymore. During the times I compose less poetry, I can revise and rework older poems. I can gather completed poems together and puzzle over making the next manuscript. Or I might be busy writing various genres of prose, such as this blog or work-related articles and proposals.Writing, for me, requires constant practice. It has little foundation in inspired revelation or appearances of the Muse. I do like prompts and challenges, though, for motivation and to pique my curiosity. My latest challenge-to-self is to write a screenplay. It’s a new form for me and I have to learn how to write dialogue and setting and to think in scenes. The only past experience at all similar has been my work on opera libretti, fascinating and, for this particular writer, extremely hard to do at all–let alone to do well.

Colin Pope writes, in a recent essay on Nimrod‘s blog, that he believes “poets are the types of people who feel most comfortable examining themselves on paper, tallying up inner thoughts and realizations…”

In my case, muse is a verb:

“to reflect, ponder, meditate; to be absorbed in thought,” mid-14c., from Old French muser (12c.) “to ponder, dream, wonder; loiter, waste time,” which is of uncertain origin; the explanation in Diez and Skeat is literally “to stand with one’s nose in the air” (or, possibly, “to sniff about” like a dog who has lost the scent), from muse “muzzle,” from Gallo-Roman *musa “snout,” itself a word of unknown origin.

Thanks again, Online Etymology Dictionary!

~

Worth reading for the consideration of grief as a kind of inspiration: Colin Pope on Nimrod’s blog– “Every Poem Is a Poem about Loss.”

January 1, 2020

Type

I was looking in my archive files for something I didn’t locate, and I happened upon this.

In 1981, I was a typographer; actually, I was a typographical proofreader who often stepped in when we needed another typographer (or, in a real pinch, typesetter) during rush times. This is one of the many style guide pamphlets the type designer-producers gave out to sell their fonts and as demos for set style and sizing.

When I was working in that field, I loved experimenting with the way words looked in different fonts. Sometimes I’d typeset my poems, or other people’s poems, to get a sense of how they would read on a “real” page (rather than as typewritten text; this predates word-processing and desktop publishing software). Those experiments led me and David Dunn to establish–briefly–LiMbo bar&grill books as an independent arts small press in 1982. I designed and typeset the books with help from my coworkers at various typography companies, and David did the editing.

I still love print text for the feel and look of how different printing and design choices affect the holistic environment of the page. Paper texture. Type size and choice. Gutter width. Titling. Binding, covers, front matter.

At present, I’m not yet a significant consumer of ebooks, so I can’t say whether similar design choices affect the reading experience. Surely there are differences, subtle and obvious. For the experience of reading poetry, from what I’ve seen on ebooks, I prefer print when reading poems. Technology may eventually change my point of view–I’m aware of that and open to it.

Here’s a poem from Red Queen Hypothesis (due out in 2021), designed appropriately as a bookmark by designer Ric Hanisch.

[image error]

December 26, 2019

Journals

While re-reading May Sarton’s At Seventy: A Journal, I recalled reading this essay about the book, by Jeffrey Levine, in June. I first read At Seventy when I was, I think, 40 years old…I recommended it to my mother-in-law, who–like Sarton–lived alone and loved to garden. I now recognize in Sarton’s journal aspects of life and aging and creativity that I had not thought much of when I was younger–at 40, I felt envious of her freedom as a single woman. I was raising young teens, managing a busy household, working on a master’s degree, feeling I had no time to myself.

One thing that interests me about Sarton is her decision to keep journals intended for publication, beginning I think with her journal about recovering from cancer, though she had written at least one memoir before that journal.

Another poet who wrote journals intended for publication was the Japanese writer Masaoka Shiki. Perhaps his most famous diary (in the West, at least) is “The Verse Record of My Peonies,” thanks to a translation by Earl Miner. Shiki kept writing haiku and haibun, as well as reviews, for the newspaper even as he was slowly dying of tuberculosis. His journal entries (there are others) were intended for readers.

My journals (and I have kept one ever since I was ten and read Harriet the Spy), however, would not make good reading; I would be embarrassed if they were published, especially unedited and unrevised, and no one would feel inspired, delighted, or edified by them. The concept of writing a daily journal intended to be read seems either brave or a bit dishonest, like a persona. Then again–many early weblogs were exactly that: daily public journals read by whatever online audience stumbled upon them. And perhaps this blog acts as my public journal, mostly about what I read, what’s in the garden, and what I’m teaching. Those pursuits, made public, do not mask who I am. They are the things I choose to reveal.

I don’t know if that’s different from a social media persona. But here’s a sleeping cat to look at while I ponder.

[image error]

December 17, 2019

Praise

Scent of needles & sap, the green of early winter.

pond ripples hurried & flattened by the fast cold

wind harsh enough to scatter the mallards

from water’s rough-textured surface. They leap

& flap & huddle on muddy grass, clustered, quacking.

Midday the clouds morph from one grey-white

shape to another, shadows strong, drawn from tall

pines onto the unpaved road. What hours lie ahead

we never know. No Terce or Compline ring here,

no call to prayer but antiphon train horn

& the disturbed ducks.

If I do not bow my head or bend my knee nonetheless

I praise. I praise you in and of this moment

whatever it is you are.

~