Library of Congress's Blog, page 64

January 31, 2020

Library Makes an Unsplash

Hands up on the beach at Atlantic City, N.J. Dry-plate negative by the Detroit Publishing Co., publisher, [between 1900 and 1920]. Prints & Photographs Division.

Today the Library of Congress added another way of sharing some of its timeless collections with new audiences on diverse social media channels. We’ve joined several other cultural institutions to make selected rights-cleared images available on the Unsplash free stock photography website. Founded in 2013, the Unsplash site contains more than 1 million free high-resolution curated photos furnished by a community of more than 150,000 photographers.In July, the channel launched Unsplash for Education to reach out to the student and teacher community. Several other cultural institutions besides the Library have joined in the effort—from federal agencies such as the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the United States Geological Service to fellow libraries like the British Library and New York Public Library, to other exhibitions spaces such as Birmingham Museums Trust and Museums Victoria.

Here’s a blog post from Unsplash describing Unsplash for Education and its partnering institutions. And you can visit the Library’s new presence on Unsplash here. In our first day, Unsplash reports that our page received 920,707 views and 2,000 downloads — check it out!

January 29, 2020

American Federation of Labor: History Now Digital

This is a guest post by Ryan Reft of the Library’s Manuscript Division.

Americans in the late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed the growth of two transformative but intertwined forces: massive waves of immigration from 1880 to 1920 and the roiling discontent of labor. Few organizations struggled to balance these developments more than the American Federation of Labor, one of the nation’s premier labor organizations.

The recently digitized records of the AFL in the Manuscript Division of the Library contain letterpress books of correspondence of Samuel Gompers and William Green, presidents of the organization, and by numerous other officials. The records serve as a window into the AFL’s struggle to guarantee workers’ rights, particularly those of immigrants. The collection also reveals the complexities of the organization as it struggled with race and ethnicity.

[image error]

Samuel Gompers, circa 1920. Photo: Underwood and Underwood. Prints and Photographs Division.

Established under the leadership of Gompers in 1886, the AFL represented 140,000 workers in 25 national unions, whose members were a polyglot of laborers speaking numerous languages and dialects. These newly arrived workers strove for “a healthy family, a steady job, the purchase of a house, and ‘respect among people,’ ” writes historian David Montgomery.

Even if the industries and immigrants’ origins have changed, this dynamic remains true today. In 1890, more than 140,000 employees labored in steel and ironwork – and 41 percent of those workers were born in Europe, largely from Germany, Britain and Ireland. After 1900, immigrants from Southeastern and Eastern Europe, mostly Slavs and Italians, worked alongside or replaced this earlier wave. The same proves true of other industries. Responding to a 1906 request by John Roach, secretary of the Amalgamated Leather Makers of America, that the AFL help organize workers in Hambleton, West Virginia, Gompers noted that they mostly consisted of Poles, Italians and Austrians.

Such ethnic diversity was not unique to the East Coast and Midwest. Mining interests in western states employed Greeks, Italians, Croats and Mexicans among other ethnicities. While dependent on this labor source, officials at places such as the Colorado Fuel and Iron Co. disparaged both the intelligence and hygiene of these workers. One official described them “as drawn from the lower class of immigrants.”

[image error]

AFL leader William Green in the organization’s D.C. headquarters in 1929. Photo: Underwood & Underwood. Prints and Photographs Division.

Gompers and the AFL sought to expand worker protections across industries, but the organization and its leadership had its own racial prejudices.

For example, Gompers was asked to intervene in a 1902 racial dispute involving the Stockton California Federal Trade Councils. The issue was that an African American delegate had been “ordered” off a dance floor by white members at a council picnic.

Gompers began his response by advocating for organizing all workers regardless of nationality, sex, politics, color, race or creed. Yet he followed with a far less heroic qualifier. “[W]e cannot attempt to regulate the social intercourse of the races … as organized labor it would be most unwise to stir up strife and prejudice rather than peace if we make these questions subject to decision by our organization.”

So while the AFL might have helped organize African American workers, it did far less – and in the case of some locals, absolutely nothing – to protect them.

In regard to Asian workers, Gompers and the AFL proved unequivocal in their racism. “We cannot permit the Chinaman with his prejudices, his peculiar ‘civilization’ … with his low moral standard of living and his poor conceptions of our institutions, and his racial antagonism to our hopes and aspirations and ideals to have free and unrestricted access to this country,” Gompers wrote to Oliver Werts of Parsons College in Fairfield, Iowa. Any attempt to assimilate Asians into America’s white population “would be most ruinous to us.”

Over time, the AFL’s stance on immigration grew even more complicated. Though the organization exerted little influence in shaping actual legislation, it supported immigration restrictions passed by Congress in 1917 and 1924.

The AFL records demonstrate the complexity of historical actors, be they individuals or organizations. Even a cursory review of the collection reveals this on a range of issues including socialist challenges to Gompers’ conservative leadership, the role of women, and electoral politics. Immigration serves as only one example among many, but it does signal to researchers the richness contained within.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

January 27, 2020

Letters Give an Intimate Look at Classic Hollywood Era

A letter to silent film star Clara Bow from fellow star and one-time beau Gilbert Roland appears in “Letters from Hollywood.” Photo: Bain News Service. Prints and Photographs Division.

Filmmaker Rocky Lang was taken aback a few years ago when he learned of a letter his father, producer Jennings Lang, had written in 1939.

Lang the elder had just arrived in Los Angeles that year and was seeking a job from the famous literary agent H.N. Swanson. “It was amazing because when I saw the letter he was at the start of his life, and I could see his personality in that letter,” Lang told the Hollywood Reporter.

Later, his father represented Joan Crawford and Humphrey Bogart as an agent, and he produced movies including the “Airport” franchise, “Earthquake” and “Play Misty For Me.”

Howard Prouty, an archivist at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, sent the letter to Lang. After meeting Prouty and learning more about the academy’s archives, Lang realized his father’s letter was but one example in a vast trove of letters, telegrams, memos and other missives that, together, had the potential to offer a unique view of Hollywood history.

Lang teamed up with film historian and archivist Barbara Hall to collect some of these materials into a book. Last fall, the pair published “Letters from Hollywood: Inside the Private World of Classic American Moviemaking.” The collection includes correspondence from the academy and other repositories, including the Library of Congress.

[image error]

Rocky Lang. Photo by Christopher S. Nibley.

Here, Lang answers a few questions about his book and his research at the Library.

Tell us about “Letters from Hollywood.”

It begins in the silent era and runs until the mid-1970s and contains 137 letters from many of the icons of Hollywood and those behind the scenes. Barbara and I knew from the start we could not possibly include every major figure. But we tried our best to include a selection of letters that would take us through those decades of film history and offer insight into actors and filmmakers and their personalities. We began to look for letters that spotlighted the friendships, concerns, hopes and fears of the men and women who made Hollywood great. Some are revealing, some are hilarious and some are extremely thoughtful.

Describe a few standout letters.

All the letters are standouts in their own right. In a wonderful letter from famed gossip columnist Hedda Hopper to silent movie actress Aileen Pringle, Hopper writes that she had just seen “Citizen Kane.” She described it as a “foul” film and suspected it would flop. Cubby Broccoli, producer of the early Bond movies, recounts that United Artists felt it could do better than Sean Connery for Bond. And actor Gilbert Roland reminisces about his 1920s love affair with actress Clara Bow.

From the Library’s collections, there’s a letter from Groucho Marx to Jerry Lewis in which Marx humorously deflects praise for his work in a serious role by joking that dramatic acting is a racket that isn’t as hard as it looks

My favorite might be a letter to Sam Goldwyn from Robert Sherwood, the writer who would win the Academy Award for best adapted screenplay for “The Best Years of Our Lives.” Sherwood begs Goldwyn to let him out of his obligation to write the script, listing all the reasons the movie will fail. Goldwyn of course made the film, and the movie was incredibly successful.

[image error]

The beginning of the 1939 letter from Jennings Lang that set the book into motion. Copyright: Rocky Lang. Published with permission.

Which collections did you consult at the Library?

First, I have to give credit to Barbara Hall, who gave me a cheat sheet of where to look. Barbara is a 30-year veteran in archival research, and I like to say she knows where the bodies are buried. I looked in a lot of collections at the Library, including the Hume Cronyn and Jessica Tandy papers and the papers of Rouben Mamoulian, Groucho Marx, Bob Hope, Vincent Price, Ruth Gordon and Garson Kanin. Every one was filled with great letters and great history. One can get stuck in a Twilight Zone of letter reading — they can be mesmerizing.

Did you make any surprising discoveries at the Library?

The biggest surprise occurred after I finished my research for the book. I spent some time looking to see if the Library had any footage of a trip my mom, singer-actress Monica Lewis, took with Danny Kaye to Korea in 1951 to entertain troops during the Korean War. I was surprised to find there was quite a lot of footage, some of which showed my mom and Danny Kaye onstage with shots of troops and life behind the lines. (You can see my mom at minutes 1:56 and 2:24 in the link.) I can tell you it was a very surprising and worthwhile find.

Did your research change your view of Hollywood in any way?

I don’t believe it did. I have spent my life in Hollywood as a producer, writer and director. Although I am not a historian or archivist, I have experienced the world, the characters, the egos, the passions, the emotional commitment to the work and just about everything else. The letters we chose show for the most part the best part of the men and women who built Hollywood, but we also show its dark side. In one letter, for example, silent film comedian Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle writes to mogul Joseph M. Schenck after Arbuckle was arrested for the murder of model and wannabe actress Virginia Rappe. Arbuckle was acquitted, but the scandal ruined his career and changed the way Hollywood was perceived by the public.

[image error]

Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, c. 1920-25. Photo: Bain News Service. Prints and Photographs Division.

Can you comment on the Library as a venue for research?

Barbara and I went to many libraries and archives. For me, the Library of Congress was one of the best. The staff was very helpful and supportive. And of course, the main reading room in the Thomas Jefferson Building is absolutely stunningly beautiful. Sometimes I found it hard to concentrate surrounded by all that grandeur, history and sheer magnificence.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

January 22, 2020

Researching the U.S. Supreme Court at the Library of Congress

The Supreme Court hearing a case in 1986. Artist: Marilyn Church. Prints and Photographs Division.

More than 5,000 fans came to hear U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg speak about her bestseller, “My Own Words,” at the Library of Congress’ 2019 National Book Festival, many waiting in line for hours beforehand. The previous year, Justice Sonia Sotomayor attracted a similar record-breaking festival audience, and Justice Clarence Thomas filled the Library’s Coolidge Auditorium for a talk he gave there.

It’s not just in person, however, that Supreme Court justices draw crowds at the Library: Year after year, the Supreme Court papers in the Manuscript Division are among the Library’s most frequently used collections.

Representing more than 35 justices, the papers make up the largest Supreme Court documents collection in the U.S. They span the 19th century into the 21st, but the collection is especially rich for the years after 1935, when the Supreme Court’s iconic Capitol Hill building opened — the expansive quarters provided ample space for justices to store records.

Hugo Black, Harry Blackmun, William Brennan, Felix Frankfurter, Robert Jackson, Thurgood Marshall, Earl Warren and Byron White: These are a handful of the justices whose papers bring a steady stream of visitors — scholars, journalists, students, researchers — to the Manuscript Reading Room.

They examine individual cases, they track rulings on social issues, they search for hints about the justices’ lives and they write — legal analyses, general-interest blogs, biographies, histories. When a portion of the papers of Justice John Paul Stevens, who died last July, open to the public in October 2020, interest is sure to be great.

Within the collections are handwritten letters, memos, journals, draft opinions and conference notes. Some documents connect to landmark decisions, such as congratulatory notes Warren received as chief justice following the court’s unanimous 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education against racial segregation in public schools. “Dear Chief,” wrote Justice Harold Burton, “Today I believe has been a great day for America and the Court.”

Other documents are more obscure, yet surprising: Barack Obama, then still a student at Harvard Law School, wrote to Brennan in the early 1990s reflecting on Brennan’s judicial opinions.

“The papers are as idiosyncratic as the justices,” said historian Ryan Reft, who acquires and curates legal papers at the Library. “They show how justices think about things, how they organize things … what they care about and what they choose to reveal.”

Since the early 1990s, political scientist Joseph Kobylka of Southern Methodist University has used the papers to write about judicial decision-making, intercourt dynamics and litigation on reproductive rights and the death penalty. He is also writing a book about Blackmun; some of his correspondence with the justice is included in Blackmun’s papers.

[image error]

The U.S. Supreme Court, 1910. Photo: Barnett Clinedinst. Prints and Photographs Division.

“I just love doing this stuff,” Kobylka said of his research in the papers. “At the end of the day, I’m exhausted but exhilarated at the same time.”

Every other year starting in 2011, Kobylka also has chaperoned a group of his honors students on a spring-break trip to the Manuscript Division, where they learn how to research the Supreme Court using original documents.

Paxton Murphy of Covington, Louisiana, was among the 13 students who sorted through boxes under Kobylka’s direction in 2019. Murphy was especially struck by how the justices could read the same law and precedent and hear the same oral arguments yet come to widely divergent conclusions.

“That’s the big revelation I had,” he said. “It’s just not very cut-and-dried. There are so many factors and variables that are affecting these conclusions.”

Longtime journalist and author Joan Biskupic, now a CNN legal analyst, first delved into the Library’s Supreme Court papers in 1993 as part of a team that explored Marshall’s collection to write a series in the Washington Post about the court.

While sorting through correspondence, Biskupic encountered a June 7, 1990, letter from Brennan to Marshall. Referring to the drafting of a 1990 opinion on the rights of criminal suspects to avoid self-incrimination, Brennan wrote, “As you will recall, Sandra forced my hand by threatening to lead the revolution.”

Sandra is Justice Sandra Day O’Connor. The letter, said Biskupic, “whetted my appetite for more on this woman who ‘forced’ the hand of master strategist Brennan.”

In 2005, Biskupic published the bestseller “Sandra Day O’Connor: How the First Woman on the Supreme Court Became Its Most Influential Justice” using the Library’s Supreme Court papers and other sources. O’Connor has donated her papers to the Library, but they are not yet open to the public, so Biskupic instead relied on those of other justices.

“Just because someone’s papers aren’t open, you can find out about them from the other justices’ papers — correspondence, conference memos,” said Reft. “There are other ways of getting at it.”

Using the same approach, Biskupic subsequently wrote books about Justices Antonin Scalia, Sotomayor and John Roberts. Scalia’s papers are at Harvard University. Sotomayor and Roberts have yet to decide on repositories for theirs.

“It’s very fulfilling for us as a staff to see when researchers come in and they write a book or they publish an article,” said Jeffrey Flannery, head of the reading room. “We’re not a mausoleum here — we want the collections to be used.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

January 15, 2020

‘Lost Girls’ Artwork from the Holocaust

Marie Paneth and some of her students, all survivors of Nazi concentration camps. Photo: Columbia Studios. Prints and Photographs Division.

They are scenes filled with emptiness and born of the Holocaust: Streets with no people, houses with no one home, roads that stretch endlessly to no place.

A small collection in the Library’s Manuscript Division preserves drawings created by children who survived Nazi concentration camps during World War II — artworks that reveal the emotional state of young people who had endured unimaginable horror and lost everything but their lives.

In the months following the war, hundreds of those children — homeless and alone — were taken to facilities in London and the English countryside to be cared for. One of those helping the new arrivals was Marie Paneth, an artist and art therapist who had worked with children in a London air raid shelter a few years earlier and viewed art as good therapy for children who had suffered traumatic experiences.

The drawings held by the Library were made by 11 young Polish and Hungarian women, aged 16 to 19, who studied with Paneth at a London hostel beginning in March 1946. Paneth saved their work and documented their experiences in an unpublished book manuscript also held at the Library.

“The most vivid feeling they have,” she wrote, “is that of loss, of having lost and of being lost.”

[image error]

An empty landscape, from the Paneth collection. Prints and Photographs Division.

The girls shared similar stories: Their families had been torn apart, parents separated from children, brother from sister, never to be seen again. They’d witnessed unthinkable cruelty and suffering in the concentration camps and somehow survived — lost and alone, but alive.

Maria — in the manuscript, Paneth used pseudonyms for her charges — was one. Her mother died before the war, and Maria later witnessed the execution of her father and sister by the Nazis. She was sent to the notorious Auschwitz extermination camp, where she narrowly escaped the gas chamber. She later was detailed to a German ammunition factory desperate for workers, saving her life.

In London, Maria and the others grappled with what they’d seen and experienced, with the strangeness and loneliness of their new lives, with losing everything and everyone they’d ever known. They struggled, too, with the guilt of surviving while millions like them had perished.

“I live. Those who could not take a piece of bread out of the hands of somebody who was too weak to hold it did starve and could not keep alive,” Ellen told Paneth. “[Those] who could not walk over the bodies of dead people died. The worst ones survived.”

Their new life at the hostel didn’t come easily: They fought, stayed aloof from others, refused to do their chores — enough so that the hostel warden wanted them removed. Paneth came to work with them as a last resort. She taught the girls science and math, helping make up for the years of schooling they missed while trapped in Jewish ghettos and in concentration camps.

[image error]

An empty road with no people, a typical feature of the survivors’ drawings. Prints and Photographs Division.

She also met with them once a week to draw and paint. Their pieces in the Library’s collections convey their emotional state — despair, the feeling of emptiness, of being left alone without guide and support. “I wanted to paint a girl there,” Lena said of one of her drawings, “but I could not.”

Instead, they show endless and empty plains, roads leading nowhere, streets with no living beings, towns with no soul in sight. Only slowly did people begin to appear. Lena eventually drew one image with a person: a knight riding toward a house with a lit window.

A photograph in the Prints and Photographs Division shows Paneth with her pupils, their real names inscribed on the front and notes of thanks on the back.

Art, Paneth wrote, allowed these children to express through a medium other than words things that cannot be said in words — in images that, seven decades later, still haunt.

January 13, 2020

Free to Use and Reuse: Maps of Discovery and Exploration

Exploration into the unknown — when much of the world’s surface was not accurately mapped — is the theme of this month’s edition of the Library’s Free to Use and Reuse sets of copyright-free material. The collection is an eye-opening reminder that much of the globe was not recorded until late in the 19th century.

For example, California dreamin’ wasn’t a thing — or maybe, in fact, it was — in the mid-17th century, when European explorers were just getting a fix on what would become, three hundred years later, La La Land.

[image error]

Joan Vinckeboons 1650 map of California. Geography and Map Division.

Joan Vinckeboons (aka Johannes Vingboons), a prominent Dutch mapmaker and artist in the 17th century, thought California was a large island off the coast of North America, much the same way England was a large island off the coast of Europe.

Spanish and Portuguese explorers had been traveling through Mexico and Central America for a century before the map was made, with Portugese-born João Rodrigues Cabrilho being the first to explore the coast of what is now California in 1542 and 1543, dropping anchor in San Diego Bay. They called it ”Alta California” and discovered that Native Americans had been living there for ages. Vinckeboons executed this map circa 1650, more than 100 years later, but still two decades before a permanent European settlement was established on the California coast, by which time they had learned that California was, in fact, not an island.

Still, by the early 18th century, the elite of Europe knew the planet’s broad, continental outlines, as seen in this map by one of the great cartographers of the era, France’s Guillaume de L’Isle.

[image error]

“Mappa Totius Mundi,” by French cartographer Guillaume de L’Isle. Geography and Map Division.

You’ll notice that western part of North America is a squared-off blank, and that’s where our last map comes in, courtesy of the redoubtable team of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. Below is an 1803 map that they used in the planning stages of their voyage.

[image error]

Lewis and Clark’s map of the west, circa 1803, just before they set out. Geography and Maps Division.

President Thomas Jefferson commissioned them to lead an expedition to explore the new Louisiana Purchase in 1804. The pair traversed 8,000 miles over three years, reaching the Pacific coast at present-day Astoria, Oregon, and made it back home, losing only one man in their original 45-member crew. (Sacagawea, their Shoshone MVP guide, survived the expedition, too.) Their explorations over the vast plains of the northwest, the Rockies and then on to the west coast, changed American history. This map, the work of U.S. War Department cartographer Nicholas King, was “the federal government’s first attempt to define the vast empire later purchased from Napoleon.” Lewis took it as far as Mandan Village, where they hunkered down for the first winter of the trek.

In this close-up, you can see some of Lewis’ notations in brown ink. This detail is from what is now Canada, with Lake Manitoba to the right. The upside-down writing in the center reads, “the river that calls.” That was the English translation of its Cree name, Catabuysepu, and it was said to be haunted by spirits that wailed during the night, according to the journals of fur traders who worked in the region during the era. Today, it is the Assiniboine River, named for another Native American tribe of the region.

[image error]

Lake Manitoba, Canada, lies on the right of the map.

But, really, the most striking part of the map is one word spread across hundreds of miles of territory: “Conjectiral” (sic). The word lies along the 45th parallel, roughly the border between Montana and Wyoming, but includes, in its vastness, Oregon, Idaho, Nevada, Colorado, Utah, Nebraska, South Dakota and Kansas. The westernmost settlement on the southern side of the map lies in present day central Missouri.

[image error]

The vastness of the unknown: “Conjectiral” (sic) on the early map of Lewis and Clark.

The territory, populated by dozens of tribes of Native Americans who did not need to conjecture about the landscape at all, would not be sectioned off into parts of the United States for another five decades or more. It was, at the time, still a land without fences.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

January 6, 2020

Inventing the Modern World

Thomas Alva Edison, slouching like a boss, with some of his inventions, in 1892. Photo: W.K. Dickson. Prints and Photographs Division.

This story appears in the November/December issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

The beige strip of paper tape, not quite a yard long, lies in a slender box in the Library’s Manuscript Division. The neatly inked letters stretch across the length of it. They are just below a faint series of dots and dashes.

“W-h-a-t h-a-t-h G-o-d w-r-o-u-g-h-t,” it reads.

It is the first telegraph ever sent, from the U.S. Supreme Court chamber on Capitol Hill to the Mount Clare railroad station in Baltimore, by the telegraph’s inventor, Samuel F.B. Morse, on May 24, 1844.

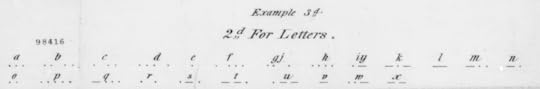

Samuel Morse’s early system of telegraph symbols. Manuscript Division.

It was if the world had shrunk, suddenly shrink-wrapped. People could communicate over dozens, hundreds or thousands of miles in seconds, not in days, weeks or even months. It was the birth of the modern, the world remade in the wake of the industrial revolution, the Victorian era giving way to age of invention.

In the next 59 years — a single human life span — the pastoral world that had dictated the life of mankind for millennia was gone, vanished in a puff of smoke from a passing locomotive. As steam-powered trains and paddle boats multiplied (themselves invented earlier in the century), a multitude of civilization-changing inventions followed. Telephones, typewriters, light bulbs, bicycles, automobiles, dynamite, vaccines, repeating rifles, the motion picture camera, x-rays, recorded sound, phonographs and records, data punch cards and radio — to name but a few — were created or taken to unprecedented levels in that time frame.

And then, on Dec. 17, 1903, on a strip of North Carolina beach, mankind took flight.

“Success four flights thursday morning,” Orville Wright wrote his father that afternoon at 5:25 p.m. He sent it, of course, by telegram.

[image error]

First flight, the Wright Brothers, Dec. 17, 1903. Photo: John T. Daniels. Prints and Photographs Division.

The modern world had arrived.

The Library houses a multitude of papers, blueprints, recordings, drawings, images and artifacts that document this dazzling era. The papers of Morse, the Wright brothers and Alexander Graham Bell are here. Collections also include those of Lee de Forest, the “father of radio”; Emile Berliner, whose innovations include flat-disc records and vast improvements in the recording industry; Herman Hollerith, whose data punch cards began modern computing (and formed the foundation of IBM); and even the Albert Tissandier Collection, which documents early balloon flights in France and across Europe. An original print of Edison Film’s “The Great Train Robbery,” is here, as is a cylinder recording of Kaiser Wilhelm II, the 1904 gift that inaugurated the Library’s recording collection.

[image error]

Still from “The Great Train Robbery,” 1903. Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division.

Here, for example, is a Bell sketch of the first telephone and notes describing the first phone call, on March 10, 1876. He wrote his father that day on letterhead from Boston University, narrating the experiment: “I called out into the Transmitting Instrument, ‘Mr. Watson — come here — I want to see you’ — and he came!”

“This is a great day with me,” Bell wrote. “I feel that I have at last struck the solution of a great problem — and the day is coming when telegraph wires will be laid on to houses just like water or gas — and friends converse with each other without leaving home.”

He was right — by 1906, more than 2.5 million American homes had telephones.

So quickly did engineers develop mass production of these breakthroughs that the world of a few years earlier began to seem quaint, in much the same way that readers today feel about the world before the internet and cell phones. In 1910, Berliner, a genius on the level of Edison and Bell, was waxing poetic about the world gone by of Washington in the 1880s, when “it required some time to get around, but people had plenty of time then.”

“Every 4th of July the daily paper announced: ‘To-night the electric light will be shone from the Capitol,’ and everybody was down on Pennsylvania Avenue,” he continued. “All at once we would see a brilliant arc light at the lower part of the dome … it was quite an interesting exhibition and everybody enjoyed it very highly.”

Edison invented the first commercially viable light bulb in 1879. So rapidly did electric light spread that by the mid-1890s Henry Ford was the chief engineer for the Edison Illuminating Co. in Detroit and built his first car on nights and weekends. By the time Berliner gave his nostalgic speech in 1910, Ford’s Model T was in mass production.

The modern world was being fashioned around the globe, but most of the above inventions were made in the United States, even though this period was the most violent in national history. The Civil War, the violent white resistance to Reconstruction, settlers warring against Mexico and Native Americans across the West, and the assassinations of three presidents — none of it deterred a restless scientific curiosity in the national spirit.

The racism and chauvinism of the day also dictated that nearly all labs, scientific equipment and funds were reserved for white men. Further, the rough business of legally claiming originality and the resulting profits often involved contentious lawsuits, further contributing to the bars white women and people of color faced.

This was exemplified by Margaret E. Knight, arguably the most famous female inventor of the age. When she invented the flat-bottomed paper bag and a machine for making them in 1868, a man in the factory stole the idea and tried (unsuccessfully) to claim the copyright. She patented more than 25 other inventions, some as complex as involving rotary engines. “I’m only sorry I couldn’t have had as good a chance as a boy,” she was quoted as saying. Josephine Cochrane of Illinois patented the dishwasher in 1886 with less hassle; her company later became KitchenAid.

“Each weekly issue of the Official Patent Office Gazette now shows a number of new ideas invented and patented by women,” wrote Fred G. Dietrich in 1899, in “The Inventor’s Universal Educator. An Educational Cyclopaedia and Guide.” “The records of the Patent Office bear witness to the fact that the inventive genius of the fair sex is constantly accomplishing remarkable, advantageous and profitable results.”

For black Americans, discrimination was worse.

George Washington Carver, born into slavery in Missouri, found his life’s calling at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama under the auspices of Booker T. Washington. His work on nitrogen depletion in cotton fields — which, he determined, could be reversed by rotating the crop with oxygen-rich plants such as peanuts and sweet potatoes — saved withering cotton yields. Farmers across the South took up the technique, preserving the nation’s most important crop, and Washington was developing the first of more than 400 products that could use peanuts and sweet potatoes.

[image error]

G.W. Carver, working in a field in Alabama. Photo: Frances Benjamin Johnston. Prints and Photographs Division.

Meanwhile, that pre-1837 generation of humanity, already a sepia-toned memory by 1903 when the Wright brothers took flight, was the last to vanish in the way that no generation will likely do again. It sank into the ocean of time without a record of its voices and sounds, of its images and angles of light; of its slowness of time, of its long quiets of late nights and early afternoons; the last to know such a time as the natural order of the world.

The birth of the modern was the beginning of a new kind of civilization, one infinitely noisier, less patient, more intrusive, more connected and more permanent. The sound and look of things could be engraved on things that lasted, so future generations could see and hear them as they lived.

Berliner, picturing how people might use his Gramophone, imagined a world in which someone might record their voice as a toddler, teenager, adult and then on their death bed — a lifetime, recorded on a single disc, for anyone to hear, across the ages.

“Will this not seem,” he wondered, “like holding veritable communion with immortality?”

[image error]

Berliner, working with one of his records. Prints and Photographs Division.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

January 2, 2020

The Man Who Recorded The World

Alan Lomax documented traditional cultures in America, the Caribbean and Europe. Lomax Collection/Prints and Photographs Division.

This story was first printed in the November/December issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

For decades, Alan Lomax traveled across America, the Caribbean and Europe, with a recorder and a camera in hand, trying to document traditional folk cultures before they disappeared.

Lomax was, in fact, the most famous American folklorist of the 20th century — the first person to record blues greats Muddy Waters and Lead Belly, the man who took down the oral histories of Jelly Roll Morton and Woody Guthrie, the chronicler of religious rites in Haiti and “ring shout” rituals from the Sea Islands off the Atlantic coast.

Lead Belly with his wife, Martha Promise. Lomax Collection/Prints and Photographs Division.

In his notebooks, Lomax documented his encounters with performers, his extensive travel and his collaborations with famous figures such as Pete Seeger, Zora Neale Hurston and his folklorist father, John Lomax. The Lomax family, friends and colleagues transcribed many of the performances and interviews he undertook during his years of fieldwork — including his stint as a Library employee from 1937 to 1942.

By the People, a web-based volunteer program at the Library, allows the public to assist such efforts by transcribing and tagging historical documents from its collections — work that improves the searchability, readability and accessibility of handwritten and typed historical documents online. Recent campaigns have focused on the papers of Abraham Lincoln, Walt Whitman, leaders in the fight for women’s suffrage, Red Cross founder Clara Barton and baseball executive Branch Rickey.

The new campaign — drawn from the Lomax papers at the Library — offers thousands of pages he produced during his field journeys, from New Hampshire to Mississippi to Haiti. In them, Lomax records the story of gospel singer Bessie Jones, visits the Gullah-Geechee singers of the Sea Islands and thumbs through Waters’ record collection. You can discover these rich traditions by helping transcribe Lomax’s notebooks and letters — documents that serve as the bedrock of our understanding of 20th-century American and Caribbean folk music and culture.

The incomparably named Bog Trotters, from Galax, Virginia. Lomax Collection/Prints and Photographs Division.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

December 30, 2019

Les Paul: Inventing Modern Sound

[image error]

Les Paul, New York, 1947. Photo: William P Gottlieb. Prints and Photographs Division.

This is the soundtrack of a revolution.

The speakers inside this studio in the Virginia foothills are blasting out “Brazil,” a 1930s classic performed over the years by Frank Sinatra, Placido Domingo and Carlos Santana and danced to by Donald Duck in a Disney cartoon travelogue.

The version playing now isn’t just something different, it’s something else — two-plus minutes of record-making innovation pulled off with primitive equipment and advanced thinking, a groundbreaking recording made by a man whose name would become synonymous with rock and roll guitar.

This “Brazil,” with its light Latin rhythm and impossibly fast fretwork, was both performed and recorded by guitarist Les Paul seven decades ago in his garage studio in Hollywood. Working there, Paul helped revolutionize record-making and pave the way for some of the greatest recordings in pop music history.

Conservationists at the Library of Congress today are working to preserve the original material that forms the foundation of Paul’s legacy.

The Library acquired his archive in 2013 — thousands of recordings, films and papers that, like “Brazil,” chronicle the man’s life and work. This year, audio specialists finished preserving and digitizing the sound recordings held at the Library’s Packard Campus for audiovisual conservation, located in the Virginia countryside about 75 miles southwest of Washington, D.C.

Paul was both a virtuoso country, jazz and blues guitar player and a brilliant technical innovator.

In the 1940s and ’50s, he pioneered recording techniques and effects — close miking, delay, phasing, overdubbing, multitracking — that later became standard. He also played a key role in developing the new solid-body electric guitar that would inspire generations of great riffs and rockers: Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, Duane Allman, Slash and countless others. He is the only person ever inducted into both the National Inventors Hall of Fame and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Paul lived a life of invention, building and modifying musical instruments and recording equipment, experimenting with recording techniques to get the sound he heard in his head down on record.

“It’s called curiosity, and I got a double dose of it,” Paul wrote in his autobiography, “Les Paul: In His Own Words.” “I’ve never stopped trying to figure out what makes things work or how to make things work better.”

As a child, he invented a flipable harmonica holder. At 13, he embedded the needle from his mom’s record player into his acoustic guitar and wired it to the speaker — his first amplified guitar. He built his own machine to cut records, using a nail, the flywheel from a Cadillac and belts from a dental drill.

In 1941, he built one of the world’s first solid-body electric guitars, an experimental instrument he dubbed “The Log,” by stretching guitar strings over a 4×4 piece of pine mounted with pickups — the primitive ancestor of guitars used years later by rock’s greatest players.

In 1946, Paul withdrew to his garage recording studio for two years, intent on creating a “New Sound” that would help revolutionize record-making.

“It was me and my little circle of engineering buddies,” Paul would write, “and no idea was too crazy to try.”

There, he pioneered early forms of overdubbing and multitrack recording that allowed his wife, singer Mary Ford, to harmonize with herself and Paul to play multiple guitars on the same song.

He would record one layer of instruments on a disc, then add another layer by playing along to the disc he’d just made and recording both to a new disc, then repeat the process over. His final version of “Brazil” is a composite of nearly a dozen separate performances, each captured on a separate disc now in the Library’s collections.

After Bing Crosby gave him one of the first commercial tape recorders, Paul quickly modified the machine so that he could carry out what his experiments on tape, too.

The innovative records Paul made alone and with Ford — “Lover,” “Brazil,” “Tennessee Waltz,” “Vaya con Dios” and “How High the Moon” — blew minds and sold millions of copies.

At the Packard Campus, audio specialists are working to preserve that important legacy.

[image error]

The master copy of “Brazil” before cleaning. Photo: NBRS Staff.

They cleaned and stabilized the discs — the “Brazil” discs began the process covered with white powdery exudation but finished a shiny black, as if they’d just been cut. The records’ sounds then were preserved as super-high-resolution digital files. To preserve heavily damaged discs, specialists used the Library’s IRENE system, which employs high-resolution cameras to take images inside the grooves then uses software to translate the images into sound.

[image error]

The copy of “Brazil,” transformed. NBRS Staff.

Paul logged the discs and tapes in a gray ledger that documents his work: early records he made in the 1930s as a country performer styled Rhubarb Red; his experiments with techniques and equipment; his groundbreaking and bestselling work with Ford; his work producing other performers, such as the cowboy band The Plainsmen, whose digitized harmonies sound as amazing today as when they were captured decades ago.

These recordings are the sound of innovation, as Paul heard it in his own studio.

“Les Paul operated at the highest technical and creative levels,” recorded sound curator Matt Barton said. “On his own and with Mary Ford, he made the most advanced recordings of his time — recordings that had to be modified just so they could be heard on the consumer playback technology of the day. As popular as these recordings were, audiences didn’t know just how good were. So, they were also, in a sense, made for a sonic future that is now with us and can be heard in the preservation work done at the Library.”

[image error]

Bryan Hoffa, an audio preservation specialist, at work on restoring Paul’s recordings. Photo: Mark Hartsell.

This article appears in the Library of Congress Magazine Nov.-Dec. issue. Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

December 23, 2019

Free to Use and Reuse: Glasses

We are all about glasses in this month’s edition of the Library’s Free to Use and Reuse sets of copyright-free pictures, prints, graphics, maps and so on. You can use these any way you like — blow them up like posters, pass them along to friends, make them your online avatar.

[image error]

Teddy Roosevelt as photographed by Baker’s Art Gallery in 1918.

Let’s start with Mr. Bully himself, Theodore Roosevelt. The 26th president was by all accounts a remarkable fellow. The illustrated fable he wrote and sent to his three-year-old son on July 11, 1890 — while he was working in Washington but the family was summering in Oyster Bay, New York — is in the Library’s Manuscript Division. It’s a delight. His refusal to shoot a shackled bear while hunting in Mississippi in 1902 soon became the inspiration for stuffed animals known as “teddy bears.”

And of course, everyone remembers him for the iconic pince nez glasses he always wore. It’s that squint behind them, the piercing look that he gave the camera when photographed, that helped capture his boundless energy. And those glasses — or, rather, their case, in his jacket pocket — helped slow an assassin’s bullet in 1912. Roosevelt, with the bullet lodged against one of his ribs (where it would remain for the rest of his life) gave the speech anyway, bleeding through his shirt all the while.

Bully, Teddy!

[image error]

Soldier peering out from a tank, Fort Knox, Kentucky, during World War II.

Next, you’d be forgiven for thinking this goggle-wearing Captain America-type hero is straight from the latest comic turned movie franchise. Check the lighting — that glow from under the chin! The darkened eyes! That headgear in shadow! And that composition, the vulnerable man trapped inside a death-dealing contraption of steel!

If it were from a movie, it might be worthy of an Oscar…but it’s a photograph of an unnamed American soldier in June, 1942, during World War II, in a tank at Fort Knox, Kentucky. Photographer Alfred T. Palmer did a masterful job of making him appear both frightening and vulnerable.

And, lastly, this doozy, also from World War II.

[image error]

World War II sunglasses for troops made from used photo negatives.

What the heck, you say? The Union of South Africa, as it was then known, had come up with a way to make inexpensive “eye shields” for soldiers battling in desert conditions. They took used photograph negatives and washed off the emulsion. Then the negatives were cut and placed in a frame. Bingo! Cheap sunglasses, way before ZZ Top had the idea. More than a million were made for United Nation’s troops. (Margaret Bucci of Washington, D.C., demonstrates them in this publicity still.)

Here’s the cool thing: The original photograph imprinted on the negative can be seen when you turn them upside down. Here, we did it for you:

[image error]

The glasses, turned upside down, reveal the original image on the negative: a group of men, perhaps military officers, facing the camera.

See those two rows of men, caps on, looking at you, kid?

Mind. Blown. You’re welcome.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers