Library of Congress's Blog, page 62

March 30, 2020

Ask a Librarian — We’re Open for (Online) Business!

The following is a guest post by Peter Armenti, a research specialist in the Researcher and Reference Services Division. It tells you how to access the Library’s fantastic online reference desk, even while our physical offices are temporarily closed.

[image error]

Reference librarians, some growing “telework beards,” monitor the Library’s Ask a Librarian service while at home. Photo: Megan Armenti.

Most of the Library’s reference librarians, including myself, are now teleworking in response to the coronavirus pandemic. But our Ask a Librarian service remains open! While our ability to completely answer some of your questions may sometimes be limited by our lack of access to the Library’s physical collections, we are committed to answering your questions to the fullest extent possible. If we need to wait to consult the Library’s physical resources before getting back to you, we’ll let you know.

Fortunately, many questions we receive can be answered remotely through digital resources, whether these be our subscription databases, our digital collections, or free online resources. One is these is how to find a beloved book when the researcher doesn’t remember the title or author. I’ve noticed an uptick in this type of question during the past couple weeks, which I attribute to many people seeking “comfort reads” during these stressful times.

Whether you’re trying to locate a book series for girls whose main character’s name starts with an A, a romance novel in which twin sisters switch places and die in an explosion on their lover’s yacht, or a male-authored poetry book about love and drinking that has a yellow cover (all real examples recently received), my colleagues and I are here to help! Feel free to submit your question to our Ask a Librarian service and we’ll do our best to track down the right book.

When submitting your question, provide as much information as possible about the book’s content, physical format, and the context in which you originally encountered or read the book. Some types of information we’ve found to be extremely helpful are details about the book’s content, physical format and context.

Content. Identify, if possible, the book’s intended audience (adults, young adults, or children); its genre (science fiction, fantasy, horror, romance, etc.); all remembered elements of the book’s plot, especially any “odd” or particularly memorable scenes or incidents that might help differentiate the book from others with a similar plot; and any unique names, words, and phrases you recall from the book. Describe, if you can, the book’s cover image and any illustrations.

Physical Format. Size and shape of the book; hardcover or paperback; number of pages; color of binding; presence of dust jacket; inclusion of illustrations (color or black and white).

Context. In approximately what year did you read the book? (Be sure not to state only that you read the book “as a child” or “when in high school,” which give no indication of the actual year you read it.) Was the book recently published at the time you read it? Did you read the book as part of a school or work assignment, or for leisure?

We can’t claim a 100% success rate—though my colleagues are pretty darn good!—even if we can’t find the right work, you’re not completely out of luck. We’ve created an entire resource guide, Lost Titles, Forgotten Rhymes, that you can consult for further guidance on strategies and resources for locating “lost” novels, stories, and poems. This includes a number of other resources you can contact to seek help from librarians and fellow readers.

Our Ask a Librarian service, of course, isn’t limited to book identification questions. The Library is home to twenty different reading room and research centers, each with their own range of subject and format specialties. If you have a question, whether it’s related to poetry and literature or a completely different subject, simply complete our General Inquiries Ask a Librarian form. Our reference staff will refer your questions to the area of the Library or subject specialist best able to answer your questions and in adherence to our Reference Correspondence Policy.

So what are you waiting for? Ask away!

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

March 27, 2020

Garth Brooks: A Few Minutes in Nashville

{mediaObjectId:'A1C5DE7EF52F00E0E0538C93F11600E0',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

We sat down with Garth Brooks for an interview at his Nashville studio last fall, just after he was announced as this year’s Gershwin Prize honoree. The studio is in a pleasant neighborhood near Music Row. It features the obligatory studios, sound booths and a control room, along with a full-sized kitchen, living room area and offices for both Brooks and Trisha Yearwood. It’s very nice but not pretentious, which also pretty much described our hosts for the day.

The pair arrived a couple of hours before the filming started, without fanfare and without a publicist or entourage. They were casually dressed, carrying their on-camera attire in clear-plastic covers, as if fresh from the dry cleaners. Other than a makeup artist and a staff worker or two, they had no else at the studio. For musical artists working at this level, it was a remarkably drama-free day. While Yearwood was in makeup, Brooks sat at a table with our film crew, tapping on a laptop, sipping coffee and amiably passing the time.

His deep roots are in country and western (it really used to be called that, kids) and he demonstrates that in this clip. In one sequence, he walked us through his musical influences, giving a cappela impressions of Merle Haggard, George Straight and Hank Williams Sr. and how they influenced his singing style. He used “Two of a Kind” as an example. It was something to see.

In this brief video, we also place how his music fits into the Library’s collections of American music that stretches back to the foundation of the country. And don’t forget to check out the Gershwin concert Sunday at 9 p.m. on your favorite PBS station.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

March 26, 2020

Free to Use and Reuse: Cherry Blossoms

The Washington Monument rises above the cherry blossoms along the Tidal Basin. Photo: Carol Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division.

It’s peak cherry blossom season in D.C., that gorgeous week or two every year when the Tidal Basin and many neighborhoods around the city are filled with delicate clouds of pink. And delicate they are — even a soft breeze lifts a shower of petals from their branches into the air, fluttering, until they tumble to the ground.

Travel restrictions being what they are, the festivals are canceled for this season. So we decided to bring a splash of that color to you. The images are from the Library’s Free to Use and Reuse sets of copyright free photographs, prints, drawings, woodcuts and whatnot. There are millions of them and they’re yours for the taking — print them out as big or small as you wish, use them for wallpaper or screensavers. In the past few months, we’ve highlighted classic movie theaters, genealogy, maps of discovery and exploration and so on.

The drive to plant cherry blossom trees in and around D.C. started in the 1880s. Eliza Scidmore, a prominent writer (whose brother was a diplomat in Asia) visited Japan in 1885, and, upon her return, urged the government to import and plant the trees in D.C. The idea was rejected, but Scidmore would eventually become the first female board member of the National Geographic Society and kept up her campaign. Several people imported trees to the region over the years, though, and these were very much admired.

In 1912, the mayor of Tokyo, Yukio Ozaki, gave more 3,000 trees to Washington as a symbol of international friendship. The first two of these were planted during a ceremony on March 27 along the north bank of the Tidal Basin. Like more than 1,000 others, these were of the Somei Yoshino varietal, marked by their light pink color.

[image error]

A sculpture of a Japanese lantern is set among the cherry blossoms along the Mall. Photo: Carol Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division.

In Japan, cherry-blossom viewing has been around for centuries. Below, a woodcut from the 19th century shows a young girl remembering a festival on the bank of the Sumida River. The first trees were planted there in the 18th century and the area — in Tokyo — is still a prime tourist spot. The girl is holding a doll that commemorates the Hinamatsuri, or Girls Day Festival. These type of prints were often used as frontispieces of novels and literary journals of the era and reflect the soft beauty of the trees they depict.

[image error]

A 19th-century Japanese woodcut shows a young girl, holding a doll, remembering a cherry blossom festival. Prints and Photographs Division.

So. We’re sorry if you missed the blossoms in D.C. this year. But they’re here every spring, and we invite you back as soon as conditions permit.

[image error]

Cherry blossom trees flanking the Tidal Basin with the Jefferson Memorial in the distance. Photo: Carol Highsmith. Prints and Photographs Division.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

March 25, 2020

National Recording Registry: It’s Victor Willis, Mr. “Y.M.C.A”!

Victor Willis, center, in his role as the cop with the Village People. Copyright 2019. Courtesy of Harlem West Entertainment.

Victor Willis, Mr. “Y.M.C.A.” himself, has just come upstairs from his home gym in San Diego and grabbed the telephone. Couple miles on the treadmill, pushups, weights. He’s 68, the founder and lead songwriter of the Village People and, until the coronavirus shutdowns, had 50 or 60 shows lined up this year.

“We were booked all through the year, all over the world,” Willis says.

The voice coming down the line is energetic, upbeat. Despite the postponed gigs, he’s in a good place after decades of turmoil. He’s happily married, wealthy and won a landmark copyright case a few years ago to obtain 50% royalties on the Village People hits that he co-wrote, which is all of them. He also regained control of the group’s name and performing rights.

But the cherry on top? “Y.M.C.A.” is a member of this year’s class of the National Recording Registry. That’s right, kids – that infectious stand-up-and-boogie disco classic, complete with a singalong chorus and over-the-top enthusiasm for a single-sex gym and fraternal living facility – is now in the official time capsule of American history.

”I had no idea when we wrote ‘Y.M.C.A.’ that it would become one of the most iconic songs in the world and a fixture at almost every wedding, birthday party, bar mitzvah and sporting event,” goes his official statement.

But where did the song come from? How did a giddy tribute to the Young Men’s Christian Association, a religious non-profit founded in 19th-century London, become one of the most instantly recognizable songs in late 20th-century America?

For this, we need to go to the disco-crazed days of winter 1978-79, specifically to New York City’s nightclub and bar scene. “Saturday Night Fever,” set in Brooklyn, had rocked the world year before. Studio 54 reigned supreme for the city’s celebrities. Donna Summer and the Bee Gees ruled pop music. Manhattan’s Greenwich Village was a hotbed of gay life and fashion.

Willis was a singer in the city’s theater scene. A native of San Francisco, the son of a Baptist preacher, he’d come to the Big Apple in the early ’70s. He didn’t live in the Village but at 63rd and Broadway, in the old Empire Hotel, just a couple of blocks west of Central Park and north of Columbus Circle. This was around 1972. Money was tight.

Over the next few years, he joined the prestigious Negro Ensemble Company and was an original Broadway cast member of “The Wiz,” playing lead roles as an understudy.

By the late ’70s, he agreed to sing lead and background vocals for an unnamed concept band that was the brainchild of Jacques Morali, a French record producer. Morali was gay and loved the flamboyant personalities he’d see at Village nightclubs. He eventually called his project the “Village People,” although Willis was the only person in the group, wasn’t gay and still didn’t live in the Village. (It’s show biz, people!)

Session musicians played on the recordings in lieu of an actual band. But “San Francisco,” one of the first songs, was a club hit. To boost the stage show, Willis and Morali rounded up dancers to play send-ups of the gay New York club scene – the biker, the cowboy, the soldier, the construction worker, the Native American chief. Willis began writing lyrics for new songs, including “Macho Man,” a parody of male sexuality. Morali did the music.

Onstage, Willis played the cop or, sometimes, the Navy officer. Offstage, he’d just married a young actress he’d met while they were both in “The Wiz.” Her name was Phylicia Ayers-Allen. Six years later, after they divorced, she would marry football star Ahmad Rashad, star as Clair Huxtable in “The Cosby Show” and become a pop-culture icon all her own.

But in 1978, Willis and Morali were churning out material for a third album. They needed a hit. Willis found his mind wandering back to his youth.

Growing up in San Francisco, his family’s modest home was just a few blocks from the Buchanan Street Y, in the northern part of the city. Willis and his friends went there to work out, goof around and play in basketball leagues. They had a lot of fun.

He had leaned on the Y again in New York. The West Side Y – 5 West 63rd — was two blocks from his old place at the Empire Hotel.

So he put pen to paper. He imagined a kid, not much different than himself, maybe 20, 21 years old, sitting on the corner of 63rd and Broadway, in front of the Empire. He saw it now from a slightly older perspective, as a guy who could offer advice to a kid like that.

“I imagined somebody coming in town and, you know, maybe having blown all their money or couldn’t afford to go to the five-star hotels,” he says. “They were just sitting there not knowing which way to go with their life. So that was the first line.”

Young man, there’s no need to feel down

I said, young man, pick yourself off the ground

I said, young man, cause you’re in a new town

There’s no need to be unhappy

The hard times for a young actor in New York were no joke. Though the song would later be seen as camp gay comedy, he was not intentionally writing double entendres.

“There were times that I felt, you know — the expression was being ‘down and out with the blues.’ And so I would go to the Y to pick myself up. I’d go back home and get ready to get back to my life.”

Thus, in the song taking shape in front of him over the course of a few weeks, he wrote:

Young man, I was once in your shoes

I said I was down and out with the blues

I felt no man cared if I were alive

I felt the whole world was so tight

This thing wasn’t supposed to be a downer, though. This was glitter-ball dance music. And so, remembering his teenage years in San Francisco, he jotted down a simple truth:

It’s fun to stay at the YMCA

It was so much fun, in fact, that he repeated the line. Suddenly, a chorus.

Willis, remembering it now: “I would write one draft and then, when I was on the road, I can’t tell you exactly where, I would right another draft. The final draft that I did I remember was in Vancouver just before going to do a concert.”

Morali added the music. Horace Ott, a music-industry veteran with a long resume of hits, added the horn and string arrangements, giving the song the punchy blasts that heralded the chorus. It was done.

“Y.M.C.A” dropped on Nov. 13, 1978. It blew up in January and February of 1979. But for all we remember it today, it never hit No. 1 – it stayed stuck at No. 2, at first behind “Le Freak,” by Chic, and then was leap-frogged by Rod Stewart’s “Da Ya Think I’m Sexy?”

That year, seven of the top 10 songs of the year were disco. Two years later, at the end of 1981, none were.

Disco was dead, baby, but “Y.M.C.A.” was just getting started.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

March 23, 2020

Mystery Photo Contest: The Lady in the Hat Revealed!

Cary O’Dell at the Library’s National Recording Registry runs our Mystery Photo Contest. In this guest blog, he’s back with the story of a mystery solved. If you’d like to take a crack at some of these, see the links below.

[image error]

The Lady in the Hat is a a mystery no longer.

Well, it took four years…but we solved another Mystery Photo Contest entry!

This one has been known as The Lady in the Hat, for obvious reasons (that feather!). But she’s a mystery no longer, and her real name is….well, hang on.

Careful readers will recall that several years ago the Library’s Moving Images section received a huge collection of film, TV and music industry photographs. Publicity stills, most of them, head shots and glamour poses. Nearly all of them were properly identified and we dutifully filed them away. But there were others. The unlabeled, the unidentified, the completely unknown…mystery photos! Not only were these faces of yesteryear not familiar, the pictures had no dates, locations or titles.

To identify them, we tried reverse-image searches on the internet. Consulted databases. Passed the pictures around the office. Nothing.

So we turned to you, gentle readers!

We’ve posted pictures on several blogs over the years, asking you to help. We’ve received hundreds of guesses, tracked down the best hunches and have been able to name a few. Just last year, cult film fan Joe Bob Briggs and his fans identified Esther Anderson, a Jamaican model, actress and filmmaker, who once starred in “A Warm December” with Sidney Poitier. (See both of the previous links to try your hand at more mystery solving.)

[image error]

Esther Anderson, the Jamaican actress and filmmaker, in a photo included in the Mystery Photo Contest.

The Lady in the Hat proved a bigger mystery, though.

We had some very good guesses (Louise Fletcher, Susan Oliver, Lola Albright, Shirley Bonne, Marina Vlady), but none were correct.

Until now, that is. She was hiding in plain sight, a recurring but infrequent guest star in a television series that everybody of a certain ages remembers.

Here’s how it happened: Like many film and TV fans, I belong to Facebook groups devoted to old movies and vintage television shows. There, a few weeks ago, someone posted a photo of the British actress Janette Scott. She’d been in more than 30 movies in the 1950s and 1960s, things like “No Highway in the Sky,” starring James Stewart, and “As Long as They’re Happy,” in which she starred opposite James Buchanan. Looking at her picture, I noticed a resemblance to the lady with the funky hat. And the more I searched for Janette’s images, the more I became convinced that this mystery had been solved.

Never shy, I tracked down her address (she’s back home in England) and mailed her a copy of the photo with a short cover letter. Impatient, I also called her son, the singer James Torme (his dad was Scott’s ex-husband, the late Mel Torme). When I got him on the line, I emailed him The Lady in the Hat photograph. I was very excited. “IS THIS YOUR MOM?!” I all but shouted.

He opened the attachment, took one look and said — lickety-split and without hesitation – “No.”

AARRGGHH.

[image error]

The full contact sheet that came to the Library with no identifying material.

But then, a week or two later, someone posted a picture from “Hogan’s Heroes,” the goofy CBS sitcom that ran from 1965 to 1971. Remember? The world’s most incompetently run Nazi prisoner of war camp? Col. Klink? Sgt. Schultz? “I know nnootttthhiiinnggg!”

Well. Every few episodes in the first season, Col. Klink’s secretary would show up, the lovely Helga. She was even a clandestine love interest for the show’s hero, played by actor Bob Crane. (In real life, they had a relationship, which was included in Paul Schrader’s 2002 film, “Auto Focus.”)

I thought, “You know…”

The actress was Latvia native Zinta Valda Zimilis. She and her family fled Soviet occupation during World War II, made it through Nazi Germany and eventually to the United States. Once in Los Angeles, she went by the stage name of Cynthia Lynn. She had a 14-year film career of mostly television guest spots in the likes of “The Six Million Dollar Man” and “Mission: Impossible” in addition to “Heroes.” Her last role, according to the Internet Movie Database, was a tiny one in “Harry O” in 1975. Her character was just called “Chick.”

She then apparently left the business at age 39. She wrote memoir of her youth in Europe when “Auto Focus” came out and died on March 10, 2014, in Los Angeles. But it turns out her daughter, Lisa Brando, is very much alive. (Lisa also had a famous dad — Marlon Brando. This was getting weird.) I tracked down her email address and sent her The Lady in the Hat photo with the standard query.

She soon emailed me back. I opened it, fingers crossed. This is what she wrote: “WOW!!! YES!…That’s my mother! I have never seen these before. THANK YOU so much!”

[image error]

Ladies and gentlemen…Cynthia Lynn.

Actually, I think I was a little more excited than Lisa. The Lady in the Hat, revealed at last! Plus, it felt even better to send her a picture of her mom she hadn’t known of before.

Four years and a mystery put to rest. At the Library of Congress? All in day’s work.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

March 19, 2020

Parents! Smart Fun for Kids

Student learning to use a sextant at a Los Angeles high school, 1942. Photo: Alfred T. Palmer. Prints and Photographs Division.

The Library has millions of resources online – including some of history’s most important manuscripts, photographs, maps, recordings and films – to help teachers, parents and students learn about the world around us.

These include general exhibits you can dip into, such as “Rosa Parks: In Her Own Words,” “Shall Not Be Denied: Women Fight For The Vote,” and “Mapping a Growing Nation: From Independence to Statehood.”

We’ll be highlighting more of these during the coming weeks, so check back often.

Meanwhile! Parents, to start us off, here are some great ideas from the Library’s Center for Learning, Literacy and Engagement staff for everyone at the house.

All ages:

Record a family story.

Download the StoryCorps app to record family histories. It’s great for building an oral history of your household. StoryCorps will walk you through the process, including suggested questions and interview tips. StoryCorps recordings are archived at the Library’s American Folklife Center.

Create an “exquisite corpse” story or poem. Jon Scieszka, the 2008-09 National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature, started the Library’s own “The Exquisite Corpse Adventure” and had an all-star cast of fellow authors (Kate Dicamillo, Katherine Paterson, Lemony Snicket, etc.) fill in the 27 chapters. Here’s how to play: Players construct a story by stringing together disconnected sentences or phrases. It creates a “Frankenstein’s monster” type of tale, hence the “corpse” moniker. It can be as silly or serious as the players make it. First, find a photograph in the Library’s online catalog or use one of these suggested images from photographer Gordon Parks. (If you’d rather, select a family photo.) Gather players in a circle to examine the photograph. One person starts by writing a line or sentence about the image. They pass the paper to the person to their right. In turn, that person writes a second line of text — but before passing the paper, they hide all the preceding sentences, so that no player sees anything but the preceding sentence. Continue this until each person has written three lines. Then, voila! Read the entire creation aloud.

Elementary & Middle:

Read aloud a classic children’s book.

Find digitized copies of rare children’s books in the Library’s collections. You’ll find everything from Mother Goose stories to “Baseball ABCs.” Pick your favorite and read aloud!

Read and write in braille.

Want to learn how to read with your fingers? Introduce your kids to the basics of braille with the National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled (NLS). NLS is free for people with temporary or permanent visual impairment that prevents them from reading or holding a page. The NLS is part of the Library and can teach you how to get started.

Write a letter to Rosa Parks.

Read about Rosa Parks’ life in her own words in our online exhibition. Then, have children create a card or letter, imagining they are sending it to Mrs. Parks, using kids’ letters like these as inspiration. Mrs. Parks loved children and met with them often. What would you say to the mother of the civil rights movement?

Be a Kid Citizen!

Explore Congress and civic engagement through primary sources with this interactive website from Kid Citizen, a Library of Congress partner organization.

Explore Everyday Mysteries.

Why do onions make you cry? How does a stone skip across water? Select a mystery every day from our Science, Technology and Business Division and find out! It’s fun research.

High School

Get a leg up on your research projects with advice from Library experts. Use our LibGuides to find resources on topics ranging from film and music to veterinary science and much more. It’s a near-endless list of information and can take you as deep into a subject as you’d like to go.

Find poetic inspiration from our Poetry and Literature Center.

Former U.S.Poet Laureate Billy Collins selected a poem for each day of the school year.

Former U.S. Poet Laureate Tracy K. Smith’s daily poetry podcast is called “The Slowdown.” In just five minutes, she presents a poem, breaks it down into engaging segments and explains how it works.

Our experimental digital team has created online projects that allow you to explore the Library by colors, play photo roulette, transcribe and tag documents from the collection and more. Try one then tell us what you think. Email comments to LC-labs@loc.gov.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

March 16, 2020

Japanese Pilot’s Map of Pearl Harbor Attack Now at Library

Mitsuo Fuchida had one of the more interesting lives of the 20th century. He led the Japanese strike force in the attack on Pearl Harbor, briefed the Emperor on its success and was critically injured in the Battle of Midway. After the war, he converted to Christianity and became an evangelist in the United States. His after-action sketch of the Pearl Harbor attack is now in the Library’s collections. Ryan Moore, a cartographic collection specialist now detailed to the History and Military Science Section, contributed to this report.

[image error]

Photo by a Japanese pilot coming in behind a fellow bomber during the Pearl Harbor attack. Prints and Photographs Division.

Just before 8 a.m. on Dec. 7, 1941, Mitsuo Fuchida, leader of the Japanese strike force in the attack on Pearl Harbor, radioed his force: “To-ra! To-ra! To-ra!” It was the signal that they had achieved complete surprise.

During the next two hours, during two waves of attacks, he circled above as his fliers killed more than 2,400 Americans, sank four battleships and ignited war between the two nations.

On Dec. 26, he was back in Tokyo, walking into a small room in the imperial palace. At one end was an elevated platform, about two feet high. A court official walked through, wafting incense. Then Emperor Hirohito entered, wearing the uniform of a “naval generalissimo,” sat down on the elevated platform and listened to a briefing from the men who carried out the attack.

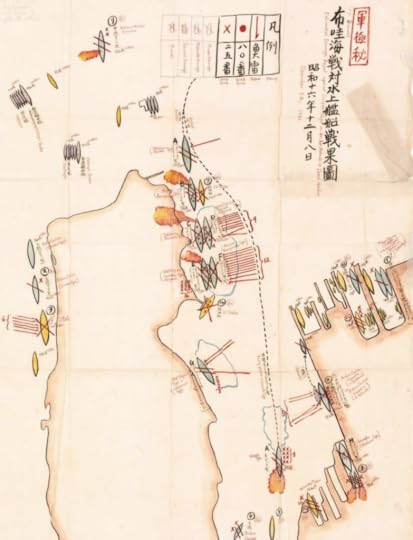

Mitsuo Fuchida’s battle report of the attack on Pearl Harbor. Geography and Maps Division.

The heart of Fuchida’s presentation was his rectangular, hand-drawn map of the harbor and the ships that had been struck. It was mostly accurate, detailed and highly classified. He used a photo enlargement of it to make it easier to see during the presentation.

Today, Fuchida’s original Pearl Harbor map — a one-of-a-kind artifact from a critical moment in world history, made by the person who carried it out — finally rests in the Library’s Geography and Map Division. Its official title is “Estimated Damage Report Against Surface Ships on the Air Attack of Pearl Harbor.” It was purchased from the Miami-Dade Public Library in 2018, ending an odyssey of more than three quarters of a century in which the map was primarily kept in the private collection of Gordon W. Prange, chief historian of U.S. Army Gen. Douglas MacArthur.

“This was made in almost real time,” says Paulette Hasier, chief of the G&M Division, leaning over the map on a recent afternoon, pointing out details. Fuchida put the map together after consulting with dozens of other pilots and military staff during the voyage back to Japan. “Fuchida crafted this cartographic piece himself, but he didn’t do it without a lot of help from others.”

The map is in good shape on slightly yellowed paper, measures 31 by 24 inches, and is stored in a large conservation box. When the cover is pulled off, the map beneath is a surprising jolt of color.

It depicts an aerial view of the harbor and is labeled 軍極秘 (Top Secret) in red in the upper right corner. Using Tokyo time, Fuchida dated it 8 December 1941 and titled it in traditional Japanese calligraphy.

He carefully drew 60 ships in green, blue and yellow watercolors. He did not generally include the names of ships but instead provided their type and size. Fuchida indicated the level of damage with categories such as minor, moderate, serious and sunk. He noted the types of torpedoes and bombs used. He told the Emperor he thought it was about 80 percent correct, which, given that the pilots were making visual assessments at high speed while under fire, was impressive. His one major error was astonishing: the failure to note the sinking of the USS Arizona, by far the most lethal strike of the day. The Arizona wreckage was obscured by such thick black smoke that it could not be seen clearly from the air.

[image error]

For comparison: A Navy map of the ships at Pearl Harbor just prior to the attack. Photo: Associated Press. Prints and Photographs Division.

The red arrows depicting torpedoes are still bright, as are the red “X” markings that denote a bomb strike. The orange of billowing fires is still clear. The desperate maneuvers of the battleship USS Nevada to attempt to escape the harbor are marked by a series of elliptical dashes.

Beneath the ink are pencil marks, showing his original outlines.

“It’s not your standard military map in black and white,” Hasier said. “Obviously, this was made for a presentation. There’s a bit of showmanship.”

The map’s authenticity isn’t questioned, largely thanks to Fuchida. He was one of the few pilots who attacked Pearl Harbor to survive the war – Naval History magazine estimated in 2016 that fewer than 10 percent of Fuchida’s squadron lived to see the end of the conflict. Fuchida himself was badly injured in the Battle of Midway and was hospitalized for nearly a year. After the war, he converted to Christianity, renounced Japan’s aggression, and often toured the United States as an evangelist. Sometime in 1946, Fuchida gave the map to Prange. The historian kept it for the rest of his life, as he wrote definitive accounts of war battles, including “At Dawn We Slept: The Untold Story of Pearl Harbor.” His notes became the background for the 1970 film, “Tora! Tora! Tora!”

Fuchida died in 1976; Prange in 1980.

After Prange’s death, scholars Donald Goldstein and Katherine Dillon edited many of Prange’s unpublished manuscripts and encountered Fuchida’s map. The Library almost acquired the map in 1994, as a gift from Goldstein’s publisher, but the opportunity passed, for reasons that are now not clear.

The map was sold at auction in 1994 to the Malcolm Forbes Collection, which sold it to the Jay I. Kislak Foundation in 2013. Kislak donated it to the Miami-Dade Library and, in 2018, that institution sold it to the LOC.

It now rests as a permanent marker of the “date that will live in infamy,” in President Franklin Roosevelt’s iconic words, in America’s national library.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

March 11, 2020

Writing African Americans into the Story

Jesse Holland. Photo by Shawn Miller

Jesse Holland wears a lot of different hats: he’s an award-winning political journalist, he’s a television host, he’s a professor and he’s a comics aficionado — he wrote the first novel about the Black Panther for Marvel in 2018.

African American history is yet another of his passions — in particular documenting long-overlooked contributions of African Americans to U.S. life. In 2016, he wrote “The Invisibles: The Untold Story of African American Slavery Inside the White House,” a companion to his 2007 bestseller, “Black Men Built the Capitol: Discovering African American History in and Around Washington, D.C.”

This year, he’s researching a new book about African American history as a distinguished visiting scholar at the Library’s John W. Kluge Center. Here, he answers a few questions about his research — and about his surprising personal connection to the Library’s Rosa Parks Collection.

What is the topic of your new book?

I’m writing about the life and death of Freedman’s Village, a lost African American city that sat on the grounds of Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia, and was populated by freed slaves, black abolitionists and members of the United States Colored Troops during and after the Civil War.

What inspired you to pursue this story?

I started working on my first book, “Black Men Built the Capitol,” in 2005. In addition to writing about the untold black history of Washington, D.C., I wanted to expand into nearby Virginia and Maryland. I discovered the Freedman’s Village story while researching the African American roots of Arlington National Cemetery. I wasn’t able to devote many pages to the story in the “Black Men Built the Capitol” because of its focus, but the story stayed with me.

[image error]

Adults and children read books in front of barracks at Freedman’s Village in the early 1860s.

Which collections are you using at the Library?

I’m using so many different collections, because there are so many great resources here. I’ve been able to find actual photographs and maps of Freedman’s Village in the Prints and Photographs Division, both online and not yet digitized. I’ve been pulling newspaper stories about the people of Freedman’s Village from the Serial and Government Publication Division. And I’ve been going through the papers of government and military employees who worked at Freedman’s Village in the Manuscript Division. There’s so much stuff that I’m always racing the clock to make the best use of my time here at the Library.

What are a few standout items you’ve discovered?

I talk a lot about the story of Freedman’s Village being unknown, but there was quite a bit of publicity around the town when it began and while it existed. I’m slowly going through the papers of D.B. Nichols, who was the Army official in charge of Freedman’s Village at its start. And I’ve also found some interesting things about Sojourner Truth, who spent a couple of years in the town, supposedly to help teach the free slaves how to acclimate to life as free Americans. But apparently, she had to take up arms and defend the town against raiding slave traders. For the rest of it, you’re going to have to read the book in a few years!

Tell us about your connection to the Library’s Rosa Parks Collection.

That’s a great story! I was working as a race and ethnicity reporter for the Associated Press in Washington, D.C., in 2014, having just ended a lengthy stint as a Supreme Court writer. One of my first big stories on the beat was about fights then occurring between the children of civil rights leaders Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X over their ancestors’ belongings.

While working on the story, an auctioneer from New York City contacted me and offered me a chance to see Rosa Parks’ archived materials in person. They had been taken away from Parks’ home city of Detroit following an extended legal fight between Parks’ heirs and her friends — a dispute similar to the court battle among King’s heirs.

So, I headed up to New York City and met with up videographer Bonny Ghosh. Together, we journeyed to the auction house and spent hours upon hours in a room packed to the gills with Rosa Parks’ things: her Congressional Gold Medal, Presidential Medal of Freedom, dresses, diaries, recipes, correspondence, combs, brushes, magazines, papers, programs and much more.

Afterward, I wrote a story, noting that no high bidder had yet emerged for the archive. An accompanying video, produced by Bonny, went out around the world.

[image error]

“Rosa Parks: In Her Own Words” is now on view at the Library of Congress. Photo by Shawn Miller.

I was caught by surprise a few months later when Mike Householder, a Detroit AP reporter, told me something was happening with the Parks archive. I began making calls, and the two of us ended up reporting that a foundation run by Howard G. Buffett had bought the archive and planned to give it to a museum to preserve it for the public’s benefit. Buffet said he heard about the archive’s plight from a televised news story. “I could not imagine having her artifacts sitting in a box in a warehouse somewhere,” Buffett said. “It’s just not right.”

And then of course, Buffett kept his word and donated the material to the Library of Congress.

I was there for the opening on Dec. 4 of the Library’s exhibit, “Rosa Parks: In Her Own Words,” and it was great to see the final resolution of something I started several years ago. Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden was gracious enough to mention my name at the opening.

I would say that this one story was probably one of my greatest achievements as a journalist, knowing that my work started this material on its path to the Library of Congress, where it will be properly preserved and available for Americans from now on.

What is it like to be a resident scholar at the Library?

I absolutely love it in the John W. Kluge Center! I can sit and concentrate on the research for my next couple of books — Yes, I’m already planning past my book on Freedman’s Village and, no, I’m not ready to talk about my next nonfiction project yet! I get to talk with my fellow scholars, a group of really intelligent people, on a daily basis. And the staff of the center are absolutely wonderful people.

The only thing I don’t like about the Kluge Center is that I can’t be here forever. It has changed my life!

March 9, 2020

Bugs in the White House? In Lincoln’s Time, They Swarmed

This is a guest post by Michelle Krowl, a historian in the Manuscript Division.

[image error]

John G. Nicholay, c. 1860. Prints and Photographs Division.

Presidential secretary John G. Nicolay (1832-1901) devoted much of his adult life to President Abraham Lincoln. He first hired on as Lincoln’s secretary while the great man was still president-elect, and then accepted an appointment as the president’s senior private secretary once Lincoln took office. He held the position throughout the Lincoln administration. In the 1870s, Nicolay began collaborating on a biography of Lincoln with his fellow presidential secretary, John Hay. The Hay-Nicolay partnership produced the ten-volume Abraham Lincoln: A History, published in 1890, as well as other articles and writings. For much of this time, Lincoln’s only surviving son, Robert T. Lincoln, entrusted custodianship of Abraham Lincoln’s papers to Nicolay, who fielded numerous inquiries from the public about the president until his own death in 1901. Nicolay’s long history with the person and legacy of Lincoln is documented in the John G. Nicolay Papers, which are now available online.

In terms of literary accomplishment, Nicolay is often overshadowed by his friend Hay, who later gained a national reputation as a poet, journalist, and secretary of state under presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt. But Nicolay, who edited a newspaper in the 1850s, could also turn a memorable phrase. For example, in a letter Nicolay wrote to his future wife Therena Bates on a warm night in July 1862, Nicolay evocatively described the literal and figurative invasion of his office at the White House, as the bright lights attracted “all bugdom.”

“My usual trouble in this room, (my office) is from what the world is sometimes pleased to call ‘big bugs’—(oftener humbugs),” Nicolay began, “but at this present writing (ten o’clock P.M. Sunday night) the thing is quite reversed, and little bugs are the pest. The gas lights over my desk are burning brightly and the windows of the room are open, and all bugdom outside seems to have organized a storming party to take the gas light, in numbers which seem to exceed the contending hosts at Richmond,” referring to Union General George Brinton McClellan’s recent Peninsular Campaign against Confederate forces outside Richmond, Virginia.

[image error]

Nicolay’s letter to Therena Bates, July 20, 1862, describing the insect invasion of his office. He signed letters to Therena with his middle name, George. Manuscript Division.

“The air is swarming with them,” Nicolay continued, “they are on the ceiling, the walls and the furniture in countless numbers, they are buzzing about the room, and butting their heads against the window panes, they are on my clothes, in my hair, and on the sheet I am writing on. They are all here, the plebian masses, as well as the great and distinguished members of the oldest and largest patrician families—the Millers, the Roaches, the Whites, the Blacks, yea even the wary and diplomatic foreigners from the Musquito Kingdom. They hold a high carnival, or rather a perfect Saturnalia. Intoxicated and maddened and blinded by the bright gas-light, they dance, and rush and fly about in wild gyrations, until they are drawn into the dazzling but fatal heat of the gas-flame when they fall to the floor, burned and maimed and mangled to the death, to be swept out into the dust and rubbish by the servant in the morning.”

Nicolay closed his letter to Therena with an apt comparison to the “big bugs” of politicians and notables who swirled around “the great central sun” at the White House during the day, drawn to the power wielded by Lincoln.

“I would go on with a long moral, and discourse with profound wisdom about its being a not altogether inapt miniature picture of the folly and madness and intoxication and fate too of many big bugs, whom even in this room I witness buzzing and gyrating round the great central sun and light and source of power of the government, were it not for the fear I have that if I should continue you might begin to think that I too have learned to hum, and for the still more pressing need of getting all the bugs out of my clothes and hair, and after that the yet more important duty of seeking bed and sleep to gain rest and vigor for the morrow’s labor. There is no news, so good night!”[image error]

Let’s hope that Nicolay slept tight — and that the bed bugs didn’t bite.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

March 5, 2020

Garth Brooks: Live at the Library

Gershwin Prize winner Garth Brooks and his wife Trisha Yearwood were at the Library for several events this week. Monday night, they talked on stage at the Coolidge Auditorium. Tuesday was dinner with Madison Council members and other VIPs. Wednesday was the taping of the PBS concert special. Here’s Mark Hartsell with the play-by-play of the couple’s on-stage chat with the Librarian.

[image error]

Garth Brooks performs during the Gershwin Prize concert, March 4. The show airs March 29 on PBS. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Before he rocked the Gershwin Prize concert at DAR Hall, Garth Brook couldn’t help but put on a show in the Library itself.

Decked out in his trademark cowboy hat and boots, the country music superstar paced the Coolidge Auditorium stage on Monday night and preached love and tolerance. He did an impression of a Doobie Brother singing a song about processed meat. He ate a bag of M&Ms a fan left for him on the stage floor. And, presented with two miniature Gershwin Prize medals, he dropped down on one knee before his wife, proposal style, to pin one on her dress.

Brooks and wife Trisha Yearwood, herself a country star and a celebrity chef, came to the Coolidge to talk with Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden about love, food, music and the Gershwin Prize for Popular Song — Brooks on Wednesday was honored as the 11th recipient of the Library’s annual prize.

“I’m proud as a country artist,” Brooks said. “We’re getting to fly the country flag this week in D.C. There are a million people that deserve to be in this seat more than I do, but it’s representing the songwriters — that’s what I love. The songwriters are the seeds to everything.”

Together, Brooks and Yearwood are country music’s most overachieving couple.

Brooks ranks as the No. 1-selling solo artist in U.S. history in any genre, with 148 million albums sold. He is the only artist ever to earn seven RIAA Diamond Awards, each signifying an album that sold over 10 million copies — as many as Michael Jackson, Elton John, Madonna, Prince and Elvis combined.

Like her husband, Yearwood is a big-time country star with a slew of platinum albums, hit singles and Grammys. Once a background singer who Brooks helped get a recording contract, Yearwood rose to fame in 1991 with “She’s in Love with the Boy” — the first of 19 top-10 hit singles.

Proving she’s a musician with more than one note, Yearwood also has authored three bestselling cookbooks, held down a recurring role on the TV legal drama “JAG” and for the past eight years hosted “Trisha’s Southern Kitchen,” an Emmy-winning culinary program on the Food Network.

With a tip of his hat, Brooks walked onstage with Yearwood on Monday and, together, they sat with Hayden for about 50 minutes of conversation before a fired-up crowd that included fans who had traveled to D.C. from Texas, Ohio, California and Florida just for the occasion.

[image error]

Librarian Carla Hayden talks with Garth Brooks and Trisha Yearwood at the Coolidge Auditorium, March 2. Photo: Shawn Miller.

Brooks and Yearwood discussed a daughter’s college graduation (“I’m the first Brooks to graduate high school in my teenage years,” he quipped. “This was big for our family”). Yearwood described how, with Brooks’ advice, she stays creative in the kitchen (“Take something you know, throw in tortellini and see what happens”). And Brooks demonstrated a game they play at home — singing songs in other artists’ voices — by imitating Doobie Brother Michael McDonald singing a vintage Oscar Mayer jingle (“My baloney has a first name, it’s O-s-c-a-r”).

Blame it all on his roots, but the young Brooks had to quickly learn that the dress code that mattered in the business of country music was coat and tie, not cowboy hat and boots. He went to Nashville, saw how many lucrative livelihoods depended on the inspiration of others and realized he wasn’t quite ready for music as business. After less than 24 hours, he turned around and went back to Oklahoma.

He eventually came around.

“There’s a lot of things in this this world where people think if you take care of business that means you’re not an artist,” Brooks said. “I just want to remind people that if you truly care about the music, you will take care of it after it’s created as well. You will make sure that everybody gets a chance to hear it the best that they can because there’s something in those songs.”

The business still is especially tough for young women trying to make it as performers or songwriters, Yearwood said.

As a young artist, she always tried to follow a What Would Reba Do rule — lessons she drew from watching the successful career of singer and actress Reba McEntire. That often boiled down to a simple dictum: Don’t talk about what’s not equal, just work harder.

Now, as a veteran performer, she tries to offer young women a similar example and personal encouragement.

“I have some songwriter friends who are female who are like, ‘I stopped writing songs for women because they’re not getting played on the radio,’ ” she said. “I’m like, ‘You can’t do that. You have to still be an artist. You have to still be creating. You have to still keep pushing.’ ”

Toward the end, Brooks passionately preached about tolerance, love and openness to others’ points of view — a theme of their shows — until even he could take it no more.

“I’ve sat as long as I can,” he said, getting up from the sofa and walking the stage as he spoke.

“Stand up for what you believe in. At the same time, turn these on,” he said, pointing to his ears. “Listen. Digest, then spew if you have to, but don’t try to out-scream each other. … That’s why I think that like-mindedness is good — a common goal, to love one another, to get somewhere. But how we’re going to get there is going to take all of our opinions and all of our efforts. It really is.”

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free! — and the largest library in world history will send cool stories straight to your inbox.

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers