Shakespeare Fans discussion

Group Readings

>

Cymbeline

message 51:

by

Ray

(new)

Jan 25, 2010 04:15PM

I have to admit, this play is growing on me as we read it. The situation Imogen finds herself in during the 3rd act really is wrenching... She leaves everything behind, her wealth, the luxury of court, her family, etc... and heads out to the Welsh wilderness, clinging to the hope that she will be able to meet her exiled husband there. But instead she learns that the man she loves so well, and for whom she has given up so much, now despises and wants to kill her. And she doesn't know why, or what she has done. One really has to feel for her.

I have to admit, this play is growing on me as we read it. The situation Imogen finds herself in during the 3rd act really is wrenching... She leaves everything behind, her wealth, the luxury of court, her family, etc... and heads out to the Welsh wilderness, clinging to the hope that she will be able to meet her exiled husband there. But instead she learns that the man she loves so well, and for whom she has given up so much, now despises and wants to kill her. And she doesn't know why, or what she has done. One really has to feel for her.

reply

|

flag

Ray wrote: "I have to admit, this play is growing on me as we read it. The situation Imogen finds herself in during the 3rd act really is wrenching..."

Ray wrote: "I have to admit, this play is growing on me as we read it. The situation Imogen finds herself in during the 3rd act really is wrenching..."Imogen's intense emotions are Greek-like in their tragic proportions. By contrast, today's theater often has one-dimensional characters who do not experience those extremes of feeling (emotion). The dark setting in BBC's 1982 production of Act III shows Imogen's anguish after she had known near ecstasy in the expectation of the rendezvous. In the final Act, the repetition of confessions and reconciliations are echoed by a chamber glowing with daylight.

Asmah,

Asmah,Yes, I have W W Lawrence's book. Significantly, it is dedicated to A C Bradley. There is a lot one could say about his assumptions, but to me the big one is his poor opinion of the play as a whole,

"the last 3 acts .. most unsatisfactory, giving the impression of hasty and careless workmanship, as if the dramatist had lost interest."

"the ending of the story a collocation of commonplace situations and motives ..."

But we must not blame Shakespeare too much,

"there is no doubt that he did, at times, hurried and very inferior work."

Lawrence thinks the mood changes across the play are simply a failure of Shakespeare to do a proper job. He misunderstands TWT similarly.

My own view is that far from accepting wife-murder for adultery as a norm of society that could become an uncontroversial plot element, S is deliberately challenging this belief. That is why only the innocent wives in S get this treatment. He also sees it as an "aristocratic" habit. Ford, in TMWOW, suspects his wife similarly, but does not plot to murder her.

It is nice that Ray is affected by the poignancy of the play, and equally, I'm often aware now of the comedy, having picked up on Ray's first statement that it can be done very effectively for its more farcical elements. Sometimes the two things seem to combine perfectly, as in the "Fear no more" song,

It is nice that Ray is affected by the poignancy of the play, and equally, I'm often aware now of the comedy, having picked up on Ray's first statement that it can be done very effectively for its more farcical elements. Sometimes the two things seem to combine perfectly, as in the "Fear no more" song,"Golden lads and girls all must,

As chimney sweepers, come to dust."

The embedded joke could almost be Marx Brothers,

"One day, you'll come to dust."

"You mean I ought to retrain as a chimney sweep?"

as well as being wonderfully affecting, and continuing the clay/dust theme of the play,

"But clay and clay differs in dignity,

Whose dust is both alike."

"...rotting together, have one dust..."

deriving of course from thr Bible and Prayerbook,

"...for dust thou art, and unto dust shalt thou return."

-- I see I'm slightly ahead of the reading schedule in quoting this, but I don't think that matters, given that this is probably S's most famous song from the plays.

Candy, I hadn't realised the Stonehenge bluestones came from Wales via Milford Haven, very interesting. The Stonehenge websites suggest the source of the bluestones was only worked out relatively recently, so I guess S could not have seen that connection, but even so, Milford Haven had a "Celtic" significance for him. I suppose to S Milford Haven was not just a port, but a connection point of the Welsh Celts to the rest of the world. In any case, using Wales/Milford Haven to stand for the Celtic origins of Britain is clearly deliberate. The Welsh scenes are full of Wiccan (or do I just mean Pagan?) elements.

Candy, I hadn't realised the Stonehenge bluestones came from Wales via Milford Haven, very interesting. The Stonehenge websites suggest the source of the bluestones was only worked out relatively recently, so I guess S could not have seen that connection, but even so, Milford Haven had a "Celtic" significance for him. I suppose to S Milford Haven was not just a port, but a connection point of the Welsh Celts to the rest of the world. In any case, using Wales/Milford Haven to stand for the Celtic origins of Britain is clearly deliberate. The Welsh scenes are full of Wiccan (or do I just mean Pagan?) elements.

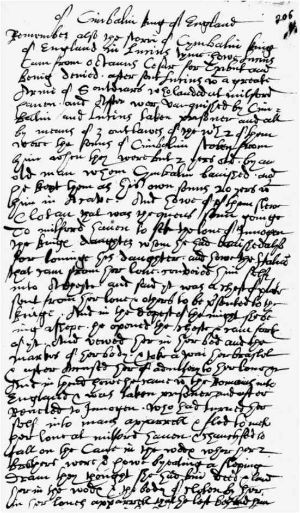

The photographed diary page is excerpted from Simon Forman's account of a Cymbeline performance when Shakespeare was alive.

Reproduced on p266 of Roger Warren's Cymbeline (1998). The caption reads: "Simon Forman account of Cymbeline (Bodleian Library MS Ashmole 208, fol. 206r), clearly showing the spelling 'Innogen' in lines 15 and 28."

Who was Simon Forman (1552-1611)? Michael Wood in an episode of 'IN SEARCH OF SHAKESPEARE' mentions Forman's visit from Shakespeare's Dark Lady, Emilia Lanier, who asked him to read her future.

"Categories: 1552 births | 1611 deaths | People from Salisbury | English astrologers | Tudor people | English writers | English occultists"

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Simon_Fo...

*********

I can't read the small handwriting in this photo, but

Mabillard, Amanda. Going to a Play in Shakespeare's London: Simon Forman's Diary. Shakespeare Online. 20 Aug. 2000. (Jan 28, 2010) http://www.shakespeare-online.com/plays/simonforman.html

uploaded Forman's responses to four Shakespeare plays and commented upon them:

Simon Forman attended productions of four of Shakespeare's plays and his thorough accounts of the performances aid scholars in dating the dramas and uncovering discrepancies in the published texts. The minor details of Simon Forman's narratives are sometimes erroneous, but they nonetheless give modern readers an impression of what it would be like to be an audience member in Shakespearean England...

Cymbeline at the Globe, 1611 (unspecified date)

Remember also the story of Cymbeline, king of England, in Lucius' time. How Lucius came from Octavius Caesar for tribute; and, being denied, sent Lucius with a great army of soldiers, who landed at Milford Haven, and after were vanquished by Cymbeline, and Lucius taken prosioner. All by means of three outlaws: of which two of them were the sons of Cymbeline, stolen from him when they were but two years old by an old man whom Cymbeline banished. He kept them as his own sons twenty years with him in a cave.

And how one of them slewe Cloten, the Queen's son, going to Milford Haven to seek the love of Imogen, the King's daughter, whom he had banished also for loving his daughter. How the Italian that came, from her love [from love of her:], conveyed himself into a chest; and said it was a chest of plate sent, from her love and others, to be presented to the King. In the deepest of the night, she being asleep, he opened the chest and came forth of it. And viewed her in bed and the marks on her body; took away her bracelet, and after accused her of adultery to her love.

In the end, how he came with the Romans into England and was taken prisoner. And after revealed to Imogen, who had turned herself into man's apparel and fled to meet her love at Milford Haven and chanced to fall on the cave in the woods where her two brother were. How by eating a sleeping dram they thought she had been dead, and laid her in the woods, the body of Cloten by her, in her love's apparel that he left behind him. And how she was found by Lucius, etc.

The excerpt from Forman's diary did not show any personal response to the play. However, his attendance during Shakespeare's lifetime is a find.

************

Here is another bit about Simon Forman's diary account of Cymbeline--what he noted and what he omitted.

In his manuscript "Bock of Plaies and Notes thereof" Simon Forman describes a 1611 performance "of Cimbalin king of England,"including such memorable moments as when"a greate Armi of Souldiars ... landed at milford hauen, and Affter wer vanquished by Cimbalin and Lucius taken prisoner"; when "the sonns of Cimbalin [were:] stolen from him when they were but 2 yers old by an old man whom Cymbalin banished, and he kept them as his own sonns 20 yers wt him in A cave"; and when Posthumus "came wt the Romains into Eng...Himself imprisoned several times (once for an entire year), Forman appears to have been more impressed by the plight of the play's prisoners than by the elaborate fifth-act masque of Jupiter (which he never even mentions)...No reference is made to Imogen's lengthy house arrest, but Forman does note that she "fled to mete her loue at milford hauen,"suggesting that he at least perceived that she was being kept at court against her will. Shakespeare emphasizes this last point from the play's emotionally charged exposition: "She's wedded/, Her husband banish'd; she imprison'd, all/ Is outward sorrow"(1.1.7-9). Forman's touching phrase "her loue" may also have been inspired by Imogen's description of how enforced separation from Posthumus prompted her "To lie in watch there, and to think on him" and "To weep'twixt clock and clock"(3.4.41-42).

Source: "Graze, as You Find Pasture": Nebuchadnezzar and the Fate of Cymbeline's Prisoners" by Philip D. Collington in Shakespeare Quarterly, Vol. 53, No. 3 (Autumn, 2002), pp. 291-322 (quote 295-6).

Martin, yes, I found that news of the Bluestones coming from Milford Haven astounding. I am not quite ready to say that S didn't know about this. I am sure that contemporary study has only brought this to light recently. I mean so literally. I think it would be fair to imagine, that if hard knowledge of the Bluestones source was forgotten...there woudld be many oral sources of such a travel. If only as an oral tradition that there was magic and power at Milford Haven. I haven't found any such song or poem yet, but I haven't looked really extensively. It's become a little side project. I'm on it! I am sure I shall find a folks song or fairy tale existing...

:)

I thought the following was delightful. I laughed at Imogen saying she could start a rumour about Iachimo incontinence. And yet the verse ends so strong after humour-still serious.

I false! Thy conscience witness: Iachimo,

Thou didst accuse him of incontinency;

Thou then look'dst like a villain; now methinks

Thy favour's good enough. Some jay of Italy

Whose mother was her painting, hath betray'd him:

Poor I am stale, a garment out of fashion;

And, for I am richer than to hang by the walls,

I must be ripp'd:--to pieces with me!--O,

Men's vows are women's traitors! All good seeming,

By thy revolt, O husband, shall be thought

Put on for villany; not born where't grows,

But worn a bait for ladies.

and...then...

Talk thy tongue weary; speak

I have heard I am a strumpet; and mine ear

Therein false struck, can take no greater wound,

Nor tent to bottom that. But speak.

Imogen's pain must be great. Really eventoday in schools to call a girl a slut can harm her terribly. Martin you say how one of the red flags is the treatment of this lovely woman. It is easy to forget how painful this situation must have ben to Imogen...partly because thepoetry is so beautiful. These peopel assuming and playing games reminds me of the harsh bullies at some of my schools. This sort of thing cntinues todayand in work places. (hence the popularity of stiff environments creating popular comedy like The Office)

I thoughtt this was insightful too....Pisano says that youth will give an edge to pretend. How true thatwe know young people have such a strong imagination for play...

And with what imitation you can borrow

From youth of such a season, 'fore noble Lucius

Present yourself, desire his service, tell him

I have a feeling that we will see play and pretend associated with magic in this play to come ...at least I am guessing so far at this.

:)

I thought the following was delightful. I laughed at Imogen saying she could start a rumour about Iachimo incontinence. And yet the verse ends so strong after humour-still serious.

I false! Thy conscience witness: Iachimo,

Thou didst accuse him of incontinency;

Thou then look'dst like a villain; now methinks

Thy favour's good enough. Some jay of Italy

Whose mother was her painting, hath betray'd him:

Poor I am stale, a garment out of fashion;

And, for I am richer than to hang by the walls,

I must be ripp'd:--to pieces with me!--O,

Men's vows are women's traitors! All good seeming,

By thy revolt, O husband, shall be thought

Put on for villany; not born where't grows,

But worn a bait for ladies.

and...then...

Talk thy tongue weary; speak

I have heard I am a strumpet; and mine ear

Therein false struck, can take no greater wound,

Nor tent to bottom that. But speak.

Imogen's pain must be great. Really eventoday in schools to call a girl a slut can harm her terribly. Martin you say how one of the red flags is the treatment of this lovely woman. It is easy to forget how painful this situation must have ben to Imogen...partly because thepoetry is so beautiful. These peopel assuming and playing games reminds me of the harsh bullies at some of my schools. This sort of thing cntinues todayand in work places. (hence the popularity of stiff environments creating popular comedy like The Office)

I thoughtt this was insightful too....Pisano says that youth will give an edge to pretend. How true thatwe know young people have such a strong imagination for play...

And with what imitation you can borrow

From youth of such a season, 'fore noble Lucius

Present yourself, desire his service, tell him

I have a feeling that we will see play and pretend associated with magic in this play to come ...at least I am guessing so far at this.

Asmah, thank you so much for the notes about The Canterbury Tales.. Isn't that a great observation you've made and /or remembered. I had not thought of that at all. See, there is some evidence of the oral tradition of magic in Wales!

Ray, I am so hit with your words...as I said in my previous post with the odd quotes. Her knowing people have called her a strumpet can not be casually taken. These are terrible assaults and why I likened them to calling a girl a slut today. Strumpet is an archaic term for us today...but it would have had a lot more pain back then in S vernacular.

(btw Martin, I so enjoyed the Lorena McKinnet song I posted it on my blog a few days ago...)

Ray, I am so hit with your words...as I said in my previous post with the odd quotes. Her knowing people have called her a strumpet can not be casually taken. These are terrible assaults and why I likened them to calling a girl a slut today. Strumpet is an archaic term for us today...but it would have had a lot more pain back then in S vernacular.

(btw Martin, I so enjoyed the Lorena McKinnet song I posted it on my blog a few days ago...)

Asmah wrote: "

Asmah wrote: "The diary page in the photo is from Simon Forman's account of his attendance at Cymbeline when Shakespeare was writing.

Reproduced on p266 of Roger Warren's Cymbeline (1998) with the caption: "..."

That's a pretty good plot synopsis for someone who only saw the play once!

Asmah, thanks for the link to Forman's diary with the account of the four plays. I wish there was some way of seeing the original text of the Cymbeline entry at a legible size. However, there is an error on the link page: the description of Richard II is not a description of Shakespeare's Richard II. His descriptions of the other three plays are amazingly accurate.

I've come across Forman before. He was fortune-teller to the intriguing Emilia Lanier, the first woman ever to have poems in print in English, and most of what is known about her comes from his diary. I'd assumed his detailed records of her were professionally useful to him (because it would be useful to him as a fortune teller to know details of her life which she had forgotten she had told him), but the synopses of the plays he saw suggest he just had a passion for facts.

So, we are on Act 4.

The first scene (Cloten telling the audience his plans) made me think of something Ray said earlier, when he approvingly drew attention to the conciseness of Imogen's summary, "A father cruel, and a step-dame false" etc. Although it is a neat summary, these, and similar passages, have been seen as major weaknesses by earlier critics, especially Granville-Barker, and Furness, a 19th century editor. Why do the people onstage keep telling the audience what they already know? They answer it by saying that Cymbeline is either the work of S plus another dramatist who botched it up, or that for once S's abilities deserted him, and he was half asleep while he wrote it. The other line of attack, starting in the 18th century, is to say that the story is completely ridiculous: that was Samuel Johnson's judgement, still worth quoting,

"To remark the folly of the fiction, the absurdity of the conduct, the confusion of the names and manners of different times, and the impossibility of the events in any system of life, were to waste criticism upon unresisting imbecility, upon faults too evident for detection, and too gross for aggravation."

I was much influenced by Granville-Barker's opinion when younger, but reading Cymbeline now I see it as great masterpiece, experimental in form. The onstage characters are partly acting the play, partly telling the story. Even Iachimo's plot to seduce Imogen is done by him talking to the audience in her presence,

"What! are men mad?"

-- the question is to the audience. In adopting this radical scheme, S can then "test" the audience, by seeing how far he can take it down the road of believing the impossible. This process comes to a climax in Act 4, where you get a complete synthesis of Johnson's absurdities, confusions and impossibilities.

About the cave, Candy, I though more of a natural cave, perhaps in a hillside. Belarius' opening words. apparently artless, create all the right connections,

... Stoop, boys; this gate

Instructs you how to adore the heavens and bows you

To a morning's holy office:

The low gate causes bowing, bowing suggests the himility of prayer, but also closeness to earth. The religion of these wild men of Wales is at once established. But "adoring the heavens" suggest their reaction to Imogen, who will shortly appear.

... the gates of monarchs

Are arch'd so high that giants may jet through

And keep their impious turbans on, without

Good morrow to the sun.

So many images crowd in here, of the high arching heavens which the gates of monarchs imitiate, of the arching of Gothic church architecture, seen from the non-Christian angle, of the impiety of Muslims, seen from the Christian angle, of the need to doff your hat to the sun, because the sun is an object of worship, presented as a polite greeting "good morrow". And the paradox that you take your hat off as you go into the building, not as you came out and say hello to the sun.

He then sends the boys up a hill. Why? Wales is famous for its hills. The idea seems to be to give them a bird's eye view of the world, and so of the world's morality. They will see Belarius like a crow,

"you above, will see me like a crow"

but surely one looks up, not down, to see a crow. This connects somehow with Immogen imagining the departing Postumus as a crow,

Thou shouldst have made him

As little as a crow, or less, ere left

To after-eye him.

The idea of sun worship surely underpins the first line of the song,

Fear no more the heat o' the sun

The sun's heat is not, by itself, a fear for which death is a welcome release.

Martin wrote: "

So, we are on Act 4.

...reading Cymbeline now I see it as great masterpiece, experimental in form. The onstage characters are partly acting the play, partly telling the story. Even Iachimo's plot to seduce Imogen is done by him talking to the audience in her presence,

"What! are men mad?"

-- the question is to the audience. In adopting this radical scheme, S can then "test" the audience, by seeing how far he can take it down the road of believing the impossible."

Martin, this is a great post! All I can say at this point is that I agree with you. For the rest, I have to wait till we reach Act 5...

Hey, thanks Ray. I see the reading is thinning out a bit ... Asmah is on holiday and Candy is distracted. Like the Britons fighting in Act 5 we could benefit from reinforcements.

Hey, thanks Ray. I see the reading is thinning out a bit ... Asmah is on holiday and Candy is distracted. Like the Britons fighting in Act 5 we could benefit from reinforcements.When I said above that the climax of incredulity is Act 4 I should have said Act 4 and the start of Act 5. The process of this happening is enormously interesting, and it would be a shame if we don't share some ideas on it in the discussion.

I notice that S is characteristically elastic over the precise ages of Guiderius and Arviragus. In I.2 they were three years of age when stolen twenty years before. But when they prepare for "Fear no more" they say

... though now our voices

have got the mannish crack, sing him to the ground.

suggesting their voices are recently broken (a 23 year old would hardly need to observe that he will not be singing as a treble). Later Postumus calls them striplings, "like to run the country base" (a children's game).

I think there has been misunderstanding about the "fear no more" song, in that with Arviragus' words "we'll speak it then" I have read that it is intended to be spoken, not sung. My guess is that S added in the excuse for not singing it for the benefit of actors without good singing voices, and the excuse can simply be omitted otherwise.

Martin wrote: "

Martin wrote: "So, we are on Act 4.

...reading Cymbeline now I see it as great masterpiece, experimental in form. The onstage characters are partly acting the play, partly telling the story. Even Iachimo's plot to seduce Imogen is done by him talking to the audience in her presence,

"What! are men mad?"

-- the question is to the audience. In adopting this radical scheme, S can then "test" the audience, by seeing how far he can take it down the road of believing the impossible."

Great post, Martin! I had to hold off on posting my response to prevent spoilers, but now that we are in Act 5, there should be no problem.

I completely agree about Cymbeline having an "experimental" or "modern" sensibility to it. The characters are constantly addressing the audience directly (recall also the snide asides of the 2nd Lord in Cloten's group).

But even more interesting are the ways that Shakespeare engages with the audience indirectly and plays on their expectations of what is going on in the play. There are plot recaps given at various points during the play-- Imogen's is just the first of several. So much is going on in the complicated plot, that Shakespeare is almost saying to the audience: "Keep up, people, we don't want you falling behind now..."

There are numerous times too where Shakespeare's characters acknowledge and comment on the absurd circumstances in the play. The mention in Act 1 on how lax the supervision of the two stolen princes must have been is one example, or in Act 4 the notion that two boys, an old man, and a bumpkin could fight off the invading Roman force by virtue of meeting them "in a narrow lane." And of course there is the creaking device of Deus ex machina, with Jupiter descending into Posthumus' cell. Shakespeare does not try to hide or gloss over the outlandishness of all this; rather he relishes it, and makes sure the audience is in on it with him.

But while the plot is outlandish, his characters (with the possible exception of Cloten and his mother) are not. They are much richer and deeply developed than stock comic characters. They have foibles, weaknesses, strengths, consciences, and they change over the course of the play. They have messy, conflicted lives.

I couldn't help but read some thematic import in Posthumus' speech in the jail:

"'Tis still a dream, or else such stuff as madmen

Tongue and brain not; either both or nothing;

Or senseless speaking or a speaking such

As sense cannot untie. Be what it is,

The action of my life is like it."

Life is full of confusions, problems, absurdities, coincidences, and you can't make sense of it. But it is life nonetheless.

Ray, I laughed out loud when you said it's as if Shakepeare is telling us to "keep up people"...

I was completely taken by surprise as I read into Act 4. I have only really felt after a few re-visits to the Act that I have any kind of grasp of what is going on. Here I must say...last week I thought this was a very straightforward, almost simple, play. I was so overwhelmed by Act 4 I know I just read it again. I've actually been looking to get a play version so I can follow all the characters and plot with visuals.

This does seem strangely contemporary now what with looking at the asides (introduced with Iachimo when he first meets Imogen).

I felt so overwhelmed by all the dialogue. As I say, I've totally got to read the whole last two Acts again. I need the plot recaps ha ha!

Yes, Martin, the ages of the brothers is confusing or vague. I found their introduction into the story wonderful though.

I loved how the brothers fell so for their "brother"/sister Imogen. One of the things I liked best was how they were impressed by "his" preparation, chopping and caring for the food. I thought this was fantastic.

I had to look at Cloten's motives and behaviour quite carefully. He in relation to Iachimo made Iachimo look just like a prankster...Cloten seems to be come evil in his motives. Ew. Sleep with Imogen?!

Imogen is fantastic. I thought her poetry in the first Acts was enough to qualify her as a great female character. But I love how she continues to impress other characters by her faith in the goodness of others worthy of her respect.

I was completely taken by surprise as I read into Act 4. I have only really felt after a few re-visits to the Act that I have any kind of grasp of what is going on. Here I must say...last week I thought this was a very straightforward, almost simple, play. I was so overwhelmed by Act 4 I know I just read it again. I've actually been looking to get a play version so I can follow all the characters and plot with visuals.

This does seem strangely contemporary now what with looking at the asides (introduced with Iachimo when he first meets Imogen).

I felt so overwhelmed by all the dialogue. As I say, I've totally got to read the whole last two Acts again. I need the plot recaps ha ha!

Yes, Martin, the ages of the brothers is confusing or vague. I found their introduction into the story wonderful though.

I loved how the brothers fell so for their "brother"/sister Imogen. One of the things I liked best was how they were impressed by "his" preparation, chopping and caring for the food. I thought this was fantastic.

I had to look at Cloten's motives and behaviour quite carefully. He in relation to Iachimo made Iachimo look just like a prankster...Cloten seems to be come evil in his motives. Ew. Sleep with Imogen?!

Imogen is fantastic. I thought her poetry in the first Acts was enough to qualify her as a great female character. But I love how she continues to impress other characters by her faith in the goodness of others worthy of her respect.

I certainly share Candy's sense of being overwhelmed. The whole play seems to invite a post-colonial interpretation (I've been learning about post-colonialism in my web browsing. "heh heh" as Candy would say.) From that perspective one sees Guiderius and Arviragus as Celtic rebels, decapitating the oppressor Cloten, who might be thought of as Roman, Anglo-Saxon or Norman. (Head hunting by the Celts is mentioned in Walter Scott -- Waverley I think -- and sticking rebels heads on spikes at Temple Bar went on in London into the 18th century). Later Guiderius and Arviragus (and Leonatus) become the ordinary people who have to fight in the pointless war their king has created, and rescue him. Meanwhile there is the sense of England struggling against an unjust taxation imposed by the colonialising Romans.

I certainly share Candy's sense of being overwhelmed. The whole play seems to invite a post-colonial interpretation (I've been learning about post-colonialism in my web browsing. "heh heh" as Candy would say.) From that perspective one sees Guiderius and Arviragus as Celtic rebels, decapitating the oppressor Cloten, who might be thought of as Roman, Anglo-Saxon or Norman. (Head hunting by the Celts is mentioned in Walter Scott -- Waverley I think -- and sticking rebels heads on spikes at Temple Bar went on in London into the 18th century). Later Guiderius and Arviragus (and Leonatus) become the ordinary people who have to fight in the pointless war their king has created, and rescue him. Meanwhile there is the sense of England struggling against an unjust taxation imposed by the colonialising Romans.I think this interests me more, being English. The themes S explores here are very much alive today.

Yes, these so many of the themes are relevant today. This greatly surprised me the way the play seemed to change. I think the relevance of post-colonialism and insurgents fits Canada and the States too.

Something is going on...what it is though?I LOVE how the brothers turn into "ordinary folks" and soldiers in the war. It makes me think of empathy...that when your life depends on blending in with others you might become more compasionate.

Surely the treatment and sudden respect accorded to Imogen as a man is telling. Her status is suddenly changed.

I also thought it was notable that Milford Haven is mentioned so many times in Act 4. About a dozen times at least in the play. Geography seems to be relevant...is it to give this area as much importance as Rome and England? I don't know. It actually seems more significant than other mentioned areas.

I found this online page interesting about Milford Haven and Cymbeline:

http://extra.shu.ac.uk/emls/05-1/hopk...

Something is going on...what it is though?I LOVE how the brothers turn into "ordinary folks" and soldiers in the war. It makes me think of empathy...that when your life depends on blending in with others you might become more compasionate.

Surely the treatment and sudden respect accorded to Imogen as a man is telling. Her status is suddenly changed.

I also thought it was notable that Milford Haven is mentioned so many times in Act 4. About a dozen times at least in the play. Geography seems to be relevant...is it to give this area as much importance as Rome and England? I don't know. It actually seems more significant than other mentioned areas.

I found this online page interesting about Milford Haven and Cymbeline:

http://extra.shu.ac.uk/emls/05-1/hopk...

Yes, the Milford Haven thing is fascinating (I read the essay you cite with interest). I don't think the stonehenge connection can have been known to S, Candy (though it would be lovely to think that it was), because it's so old. A folk memory might last a few hundred years, but stonehenge is 2000 BC or something. Milford would be an essential port for supplies if you were planning a Welsh invasion of England, which is kind of what happened when Henry VII landed there, and which is certainly one reason for its significance, but there seems to more to it than that.

Yes, the Milford Haven thing is fascinating (I read the essay you cite with interest). I don't think the stonehenge connection can have been known to S, Candy (though it would be lovely to think that it was), because it's so old. A folk memory might last a few hundred years, but stonehenge is 2000 BC or something. Milford would be an essential port for supplies if you were planning a Welsh invasion of England, which is kind of what happened when Henry VII landed there, and which is certainly one reason for its significance, but there seems to more to it than that.I find the Postumus-dream sequence a great puzzle. Some of the verses given to the spirits are execrable,

For this from stiller seats we came, Our parents and us twain,

That striking in our country's cause Fell bravely and were slain,

Our fealty and Tenantius' right With honour to maintain ...

and so on, so that many scholars have denied S's authorship of this section. Yet the verses begin and end well enough. But they lamely mimic the action of the play and contain particular echoes of S, Jove swatting flies (King Lear), and Postumus untimely ripped (Macbeth), as if written by someone keen to pretend they are genuinely by S. Could S be parodying the Masque style? Unlikely, since this is a critically important part of the play, I feel. As soon as Jupiter speaks we are back on familiar ground again.

"No more, you petty spirits of region low

Offend our hearing"

seems to be a critical judgment on the poetry of these spirits.

But his thunderbolt and dismissal is harsh treatment to Postumus' family, given the almost religious reverence which Romans gave to their ancestors. Jupiter arranges for a book to be placed on Postumus' chest,

"This tablet lay upon his breast ..."

"A book, O rare one", says Postumus on waking, opens it and reads,

"When as a lion's whelp shall, to himself unknown, without seeking find, and be embraced by a piece of tender air; and when from a stately cedar shall be lopped branches, which, being dead many years, shall after revive, be jointed to the old stock and freshly grow; then shall Posthumus end his miseries, Britain be fortunate and flourish in peace and plenty."

Now I've come across stuff like this before. It is in the "prophecies of Merlin" sections of Geoffrey of Monmouth's History of Britain, which I mentioned in an earlier post (It is the ultimate source for the Cymbeline story). Animals and trees abound, just like Postumus' lions and cedards:

"In those days, oaks shall burn in the forest glades, and acorns shall burgeon on the lime tree boughs."

"Alas for the Red Dragon, for its end is near. It's cavernous dens shall be occupied by the White Dragon."

It would be tedious to copy longer examples. The prophecies fill about 15 pages.

This second quote begins the prophecies. Sometimes you can see what's going on. The red dragon is obviously Wales, as on the present day flag.

Geoffrey of Monmouth came from Monmouth in Wales. Again one sees a post-colonial interpetation for all this.

The lion's whelp is Postumus (Leonatus = lion) and the lopped branches his reduced family.

But then Postumus puts the prophecy aside and longs for death. He has been given a great destiny, and reminded of his Roman origins but his behaviour is quite unroman. Like a Christian, he seeks death through sacrifice or execution. He does not, as a true Roman would, choose suicide. His sense of honour is quite unroman. (The Romans did not fight duels for example.) In the conversation with the goaler, the metaphor running throughout is of death paying all debts, which is just the one used in the "Fear no more" song earlier.

Wow, that is so telling I believe. What I took from the dream sequence is a kind of primordial guit. That people should respect hitw faith the wisdom of previous behaviours and beliefs...annd yet be courageous enough to stick to principles with a big picture to their responsibility. Leonutus responsibility is part his magic and royal connection through bloodlines but also history and his family upbringing.

In a way, it seems to me that his family past is also not enough to teach him wisdom on how to do the right thing. I feel as if part of a lesson here is to see we can't assume wisdom because of the past. Royalty itself isn't a given as "doing the right thing". Doing the right thing depends on examining and valuing what we are given in our environment. This experience of Leonatus is contrasted with the strength of Imogen.

Certain characters represent what happens when we make assumptions without knowledge (and this reminds me of the argument between Hermione and her King in The Winter's Tale). As if...how do we know something? What are we basing our decision making on exactly? Rumours versus experience?

Leaving magic or dinine power aside for a minute...what I am seeing here is the contrast between costume, our outer appearance and a metaphor to doing the right thing. We can dress a part and it makes us who we are...yet really our ethics and how we live ultimately betray our costumes if they are not aligned. There is a correlation between the disguises and clothing people adopt in tis play...and a lot of costumes and deceptions are occuring here. When the brothers hide in an enemies brigade. When imogen dresses as a boy. We can adopt these clothes and attitudes but what really counts is who we are in action. I see the play contesting the idea that birthright makes the man versus clothes make the man.

I become confused on this idea though because in some sense supeficilaly it seems the play might be suggesting that birthrights are more important. But I think on a deeper level we are meant to compare Cloten with Posthumous Leonatus. Cloten is the royal child compared to the adopted Posthumous. Yet....there is no primordial imperative that Cloten is a "good" person.

Somehow the play seems to demonstrate a conflict in the idea of royal blood as being trustworthy to ethical character.

I realize i could be way off here. I think what is important is to now consider how does magic help us sort out "divine power" of the royals....?

Bear with me, and if I'm way off base, let me flounder a bit...oh dear! I think what I am seeing is Shakespeare suggesting a matrix for us to test nurture versus nature. I can not see one side over another as a result at this time of my reading. I hope as I finish the last Act I shall see some resolution of sorts...

In a way, it seems to me that his family past is also not enough to teach him wisdom on how to do the right thing. I feel as if part of a lesson here is to see we can't assume wisdom because of the past. Royalty itself isn't a given as "doing the right thing". Doing the right thing depends on examining and valuing what we are given in our environment. This experience of Leonatus is contrasted with the strength of Imogen.

Certain characters represent what happens when we make assumptions without knowledge (and this reminds me of the argument between Hermione and her King in The Winter's Tale). As if...how do we know something? What are we basing our decision making on exactly? Rumours versus experience?

Leaving magic or dinine power aside for a minute...what I am seeing here is the contrast between costume, our outer appearance and a metaphor to doing the right thing. We can dress a part and it makes us who we are...yet really our ethics and how we live ultimately betray our costumes if they are not aligned. There is a correlation between the disguises and clothing people adopt in tis play...and a lot of costumes and deceptions are occuring here. When the brothers hide in an enemies brigade. When imogen dresses as a boy. We can adopt these clothes and attitudes but what really counts is who we are in action. I see the play contesting the idea that birthright makes the man versus clothes make the man.

I become confused on this idea though because in some sense supeficilaly it seems the play might be suggesting that birthrights are more important. But I think on a deeper level we are meant to compare Cloten with Posthumous Leonatus. Cloten is the royal child compared to the adopted Posthumous. Yet....there is no primordial imperative that Cloten is a "good" person.

Somehow the play seems to demonstrate a conflict in the idea of royal blood as being trustworthy to ethical character.

I realize i could be way off here. I think what is important is to now consider how does magic help us sort out "divine power" of the royals....?

Bear with me, and if I'm way off base, let me flounder a bit...oh dear! I think what I am seeing is Shakespeare suggesting a matrix for us to test nurture versus nature. I can not see one side over another as a result at this time of my reading. I hope as I finish the last Act I shall see some resolution of sorts...

Many extraordinary superstitions survive with regard to these islands. They were supposed to be the abode of the souls of certain Druids, who, not holy enough to enter the heaven of the Christians, were still not wicked enough to be condemned to the tortures of annwn, and so were accorded a place in this romantic sort of purgatorial paradise. In the fifth century a voyage was made, by the British king Gavran, in search of these enchanted islands; with his family he sailed away into the unknown waters, and was never heard of more. This voyage Is commemorated in the triads as one of the Three Losses by Disappearance, the two others being Merlin's and Madog's. Merlin sailed away in a ship of glass; Madog sailed in search of America and neither returned, but both disappeared for ever. In Pembrokeshire and southern Carmarthenshire are to be found traces of this belief. There are sailors on that romantic coast who still talk of the green meadows of enchantment lying in the Irish channel to the west of Pembrokeshire. Sometimes they are visible to the eyes of mortals for a brief space, when suddenly they vanish. There are traditions of sailors who, in the early part of the present century, actually went ashore on the fairy islands--not knowing that they were such, until they returned to their boats, when they were filled with awe at seeing the islands disappear from their sight, neither sinking in the sea, nor floating away upon the waters, but simply vanishing suddenly. The fairies inhabiting these islands are said to have regularly attended the markets at Milford Haven and Laugharne. They made their purchases without speaking, laid down their money and departed, always leaving the exact sum required, which they seemed to know, without asking the price of anything. Sometimes they were invisible, but they were often seen, by sharp-eyed persons. There was always one special butcher at Milford Haven upon whom the fairies bestowed their patronage, instead of distributing their favours indiscriminately. The Milford Haven folk could see the green fairy islands distinctly, lying out a short distance from land: and the general belief was that they were densely peopled with fairies. It was also said that the latter went to and fro between the islands and the shore through a subterranean gallery under the bottom of the sea.

http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/celt/...

I am fascinated by all the animal references. There are so many birds in the play. Many of the characters are associated with birds including Imogen. When you mention Merlin going to Milford Haven, I know that he was said to travel in a "glass boat". What an image. For me, my imagination sees that birds also travel in glass boats. We can't see the mechanisms that enable their flight.

Of course I'm trying to find the line, but doesn't the Queens poison be described as having power over animals. Merlin was believed to be able to talk to all animals.

Martin said, "A folk memory might last a few hundred years". I believe that folk memories and myths actually come to us from preliterate sources spanning thousands of years.

I use as my guides in this kind of approach to struggling with Shakespeare The Golden Bough, The White Goddess, No Go The Bogeyman, Hamlet's Mill, A Story Sharp As A Knife and . What I am seeing in the connection of Milford Haven is partly it's use as a battle stage but also as a link in lore-transmission of preliterate storytelling. I realize I will not likely find any proof that Shakespeare "knew" of an association of stones moving from Milford Haven to Stonehedge..but I believe there must be some trace in poetry or in folklore of the history of magic between the two sites. I also feel that finding such a poem or fable or "urban myth" isn't critical to reading this play...it is a side interest of mine mine merely.

I have been wondering, for example, if the significance of location, repeating Milford haven might be a kind of "axis mundi" in the play...echoed by the many trees in the play.

I wonder if there might be some kind of theme or metaphor that royal thought, true goodness is also a sort of axis mundi. Please forgive me if I sound flaky...it's more that I am exploring ideas to see if we might see hat actually regardless of my perspective, this might be part of Shakespeare's sensibility.

Belarius says of first seeing Imogen "Come not in yet; it eats our victuals, or I should think it was a fairy"

(funny association that came to my mind...

The Corgi dog known as the Queen Elizabeth's dear pet today is from Milford haven area.Folklore has it that fairies rode on these dogs.)

British Folklore has oral accounts of fairies buying meat at markets here:

http://www.scribd.com/doc/13691223/br...

http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/celt/...

I am fascinated by all the animal references. There are so many birds in the play. Many of the characters are associated with birds including Imogen. When you mention Merlin going to Milford Haven, I know that he was said to travel in a "glass boat". What an image. For me, my imagination sees that birds also travel in glass boats. We can't see the mechanisms that enable their flight.

Of course I'm trying to find the line, but doesn't the Queens poison be described as having power over animals. Merlin was believed to be able to talk to all animals.

Martin said, "A folk memory might last a few hundred years". I believe that folk memories and myths actually come to us from preliterate sources spanning thousands of years.

I use as my guides in this kind of approach to struggling with Shakespeare The Golden Bough, The White Goddess, No Go The Bogeyman, Hamlet's Mill, A Story Sharp As A Knife and . What I am seeing in the connection of Milford Haven is partly it's use as a battle stage but also as a link in lore-transmission of preliterate storytelling. I realize I will not likely find any proof that Shakespeare "knew" of an association of stones moving from Milford Haven to Stonehedge..but I believe there must be some trace in poetry or in folklore of the history of magic between the two sites. I also feel that finding such a poem or fable or "urban myth" isn't critical to reading this play...it is a side interest of mine mine merely.

I have been wondering, for example, if the significance of location, repeating Milford haven might be a kind of "axis mundi" in the play...echoed by the many trees in the play.

I wonder if there might be some kind of theme or metaphor that royal thought, true goodness is also a sort of axis mundi. Please forgive me if I sound flaky...it's more that I am exploring ideas to see if we might see hat actually regardless of my perspective, this might be part of Shakespeare's sensibility.

Belarius says of first seeing Imogen "Come not in yet; it eats our victuals, or I should think it was a fairy"

(funny association that came to my mind...

The Corgi dog known as the Queen Elizabeth's dear pet today is from Milford haven area.Folklore has it that fairies rode on these dogs.)

British Folklore has oral accounts of fairies buying meat at markets here:

http://www.scribd.com/doc/13691223/br...

Gosh, Candy, you raise so many ideas! I think the nature/nurture idea is definitely there. So many of S's plays take people out of the domestic or courtly existence, and throw them loose in the wildness of nature -- it is unnecessary to list examples. He can then show man stripped of everything, and ask, what is left? ("unaccommodated man is no more but such a poor bare, forked animal as thou art"), or show the complete indifference of Nature to our concerns ("What cares these roarers [crashing waves:] for the name of king?") Perhaps Cloten dies because he imagines his princely dignity will protect him everywhere, including the wilderness. But in Cymbeline nature/nurture is paradoxical. The wild men who kill Cloten are after all themselves princes.

Gosh, Candy, you raise so many ideas! I think the nature/nurture idea is definitely there. So many of S's plays take people out of the domestic or courtly existence, and throw them loose in the wildness of nature -- it is unnecessary to list examples. He can then show man stripped of everything, and ask, what is left? ("unaccommodated man is no more but such a poor bare, forked animal as thou art"), or show the complete indifference of Nature to our concerns ("What cares these roarers [crashing waves:] for the name of king?") Perhaps Cloten dies because he imagines his princely dignity will protect him everywhere, including the wilderness. But in Cymbeline nature/nurture is paradoxical. The wild men who kill Cloten are after all themselves princes.Milford Haven (or Wales) is the scene for this movement into a world of myth and magic ... incidentally, for your quote above,

They made their purchases without speaking, laid down their money and departed, always leaving the exact sum required.

see the section on silent trade, pages 41-6 in Hermes the Thief!

It is interesting how everyone at the end turns up in Wales, even the apothecary who gave the queen the non-poisons. Stratford-upon-Avon is not so far from Wales, and S's character Hugh Evans (TMWOW) speaks in an idiom still recognisably English with a strong Welsh accent. It was Wild Wales (George Borrow's book) even as late as the 19th century, and in the 18th century, as soon as you got off the main road you found people only spoke Gaelic in Scotland (as in Boswell's Tour), so Wales in 1600 must have been a strange land to S, still preserving in full the Celtic origins of Britain.

S was obviously interested in the Welsh language, because he includes some in in H4 part 1,

MORTIMER: Good father, tell her that she and my aunt Percy

Shall follow in your conduct speedily.

Glendower speaks to her in Welsh, and she answers him in the same

GLENDOWER: She is desperate here; a peevish self-wind harlotry,

one that no persuasion can do good upon.

The lady speaks in Welsh

--and so on. To see this in action, click here,

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5DT9Cr...

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3vsgCL...

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ib6QgZ...

Welsh is certainly strange. Bill Bryson says the place names sound like a cat bringing up a fur-ball. Here is one of them,

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Llanfair...

and an authentic prononciation of it,

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2thdZ4...

Imogen, Belarius, Guidarius, and Posthumus indicate their belief in fairies:

Imogen, Belarius, Guidarius, and Posthumus indicate their belief in fairies:INNOGEN To your protection I commend me, gods.

From fairies and the tempters of the night

Guard me beseech ye. 2.2.9-11

BELARIUS (looking into the cave) Stay, come not in.

But that it eats our victuals I should think

Here were a fairy. 3.6.39-41

GUIDERIUS Why, he but sleeps. If he be gone he'll make his grave a bed.

With female fairies will his tomb be haunted,

(To Innogen) And worms will not come to thee. 4.2.217-19

POSTHUMUS Many dream not to find, neither deserve,

And yet are steeped in favours; so am I,

That have this golden chance and know not why.

What fairies haunt this ground? 5.3.224-27

Some attributes of fairies can be gleaned from the context of the characters' lines. Imogen sees the fairies going about at night or in dreams and encouraging waywardness. In the forest's isolation, Belarius initially thinks the look-alike human is one of the fairies dropping in. Guiderius expects female fairies to keep away the worms from Imogen's grave. Perhaps, his assigning these fairies is a kind gesture in keeping with Arviragus's intention to strew heaps of various flowers upon her grave. Posthumus resorts to fairies to explain the irrational. The characters recognize the influence fairies exert in human life where humans are powerless through sleep, in forboding forests, after death, and during unexplained circumstances. Their effect can lead to good or ill.

That is very well observed Asmah. I don't think I'd ever have noticed these four references to fairies by four different characters if you hadn't pointed it out.

I don't quite understand Belarius though. Weren't fairies supposed to steal and eat food?

Martin wrote: "It is nice that Ray is affected by the poignancy of the play, and equally, I'm often aware now of the comedy, having picked up on Ray's first statement that it can be done very effectively for its farcical elements. Sometimes the two things seem to combine perfectly..."

Martin wrote: "It is nice that Ray is affected by the poignancy of the play, and equally, I'm often aware now of the comedy, having picked up on Ray's first statement that it can be done very effectively for its farcical elements. Sometimes the two things seem to combine perfectly..."Martin, I believe it is the combination of poignancy and humor that really elevates this play. The moment I remember most from the conclusion is one that may not come across as all that interesting in a private reading of the play, but in performance it was both powerful and extremely funny.

The concluding scene is one extended bout of tying up loose ends; it's enough to give a sailor apoplexy. No sooner has one plot thread been raised, than a character steps forward and deals with or explains the matter. But then, after all these extended explanations, we come to the real crux of the matter-- how will Posthumus Leonatus deal with Iachimo? Although the audience has seen Iachimo's remorse for what he's done to Posthumus and Imogen, Posthumus may well continue to hold a grudge against him, so the audience is in suspense about what Posthumus might do.

Then Posthumus weighs in, with words that are so straightforward and simple that their contrast with the rest of the scene naturally brings out a laugh from the audience:

Posthumus Leonatus. ... live,

And deal with others better.

Posthumus' forgiveness of Iachimo and frank advice to him is both touchingly profound and funny at the same time. This is the moment that sticks with me from this play, even though I saw it several years ago.

Yes, I have been struck by the humour. Iachimo's

Yes, I have been struck by the humour. Iachimo's.... mine Italian brain

'Gan in your duller Britain operate

Most vilely

shows an Olympian contempt for the intelligence of the people amongst whom he found himself. And yet of course this too has its serious side. Italy was years ahead of the rest of Europe during the renaissance.

----------

I thought one might put some of Candy's ideas to the test. When Guiderius and Arviragus are organising Imogen's (Fidele's) body at "his" funeral, Guiderius says,

Nay, Cadwal, we must lay his head to the east,

My father hath a reason for it.

To me when I first read it, this made no sense, since it would mean the body would lie north-south with the corpse on its side, while most graves in the Christian tradition point east (insofar as they point any way at all) but there is a well-informed article I found here,

http://wiki.answers.com/Q/Why_are_gra...

which states,

"Egyptian religion and culture is perhaps the most documented solar based but is far from the first which can be traced back a further 3,700 years to cave paintings and structures from the stone age. Early Egyptian graves even resemble the stone age burials, with more preparation of the body, most are head north with the entire body on the left side or at least the face turned east."

How could Shakespeare have known that? And yet clearly he did ...

In Message 74, Candy brought to light the extensive Welsh fairy culture gathered by William Wirt Sykes in British Goblins: Welsh Folk-lore, Fairy Mythology, Legends and Traditions (1880). Sykes's book, Thomas Keightley's Fairy Mythology (1878), and Joseph Ritson's Fairy Tales, Legends & Romances Illustrating Shakespeare & Other Early English Writers (1875) are often cited in my reading of Chapter I, 'Fairies', Folk-Lore of Shakespeare (Harper & Brothers, 1884) by T. F. Thiselton Dyer, who analyzes animals, plants, customs, and other phenomena in Shakespeare's plays . Dyer's source from Sykes suggests that Richard Price, the son of Sir John Price of the Priory of Brecon, gave Shakespeare knowledge of Welsh folklore. Shakespeare and Price were brought together at Brecon according to the chapter titled 'William Shakespeare in Wales' (pp22-24) in Tales and Sketches of Wales (1880) by Charles Wilkins:

In Message 74, Candy brought to light the extensive Welsh fairy culture gathered by William Wirt Sykes in British Goblins: Welsh Folk-lore, Fairy Mythology, Legends and Traditions (1880). Sykes's book, Thomas Keightley's Fairy Mythology (1878), and Joseph Ritson's Fairy Tales, Legends & Romances Illustrating Shakespeare & Other Early English Writers (1875) are often cited in my reading of Chapter I, 'Fairies', Folk-Lore of Shakespeare (Harper & Brothers, 1884) by T. F. Thiselton Dyer, who analyzes animals, plants, customs, and other phenomena in Shakespeare's plays . Dyer's source from Sykes suggests that Richard Price, the son of Sir John Price of the Priory of Brecon, gave Shakespeare knowledge of Welsh folklore. Shakespeare and Price were brought together at Brecon according to the chapter titled 'William Shakespeare in Wales' (pp22-24) in Tales and Sketches of Wales (1880) by Charles Wilkins:Shakespeare's presence in Brecon was also mentioned in Nina H. Kennard's Mrs. Siddons (1887)(pp6-7), a biography of the famous actress born in Brecon. Note that Brecon is unlike Milford Haven, being inland.

Although "Midsummer Night's Dream" is populated by a kingdom of fairy characters, a belief in these creatures is hinted at by some of Cymbeline's characters. To Imogen, Belarius, Guiderius, and Posthumus, fairies influence human lives. These creatures are generally of a good nature with a penchant for mischief. Other traits are immortality, small stature, and great beauty. Dyer's (pp12-24) description of their distinguishing characteristics includes:

*beauty of person and surroundings

*youthful immortality

*ability to vanish at will and to assume different forms

*diminutive or child-like stature

*favor romantic, rural haunts perhaps "the interior of conical green hills, on the slopes of which they danced by moonlight", or the pastures in the green fairy-rings

*dress often in green vests

*favor music and dancing

*dislike irreligious people

*reward "cleanliness and propriety" and punish the opposite

*help humans

*go long distances amazingly fast

*reward favorites, but the recipient cannot reveal their generosity

*attend to dying/dead youth

*their presence keeps away "noxious creature[s:]"

*"innocent and amiable" disposition, according to Ritson, not villainous

*delight in mischievous behavior on humans

*steal or exchange children

For instance, Belarius first thinks a fairy has visited his cave ( iii. 6):

"But that it eats our victuals, I should think

Here were a fairy.

...

By Jupiter, an angel! or, if not,

An earthly paragon! behold divineness

No elder than a boy."

Here Belarius endows Imogen with fairy-like qualities of immortality, beauty, and smallness. Ritson indicates that fairies do not eat.

Later, Posthumus awakens with Jupiter's tablet on his chest, interpreting this gift to the beneficence from the fairies inhabiting his whereabouts( v. 4):

"What fairies haunt this ground? A book? O rare one!

Be not, as is our fangled world, a garment

Nobler than that it covers," etc.

When Imogen drinks the sleeping potion, appearing to have died, Guiderius projects that fairies will tend her grave, their presence keeping away the "noxious" worms (iv. 2):

"With female fairies will his tomb be haunted,

And worms will not come to thee"

During the trunk scene, Imogen first prays before sleep to avert mischief on herself during the night (ii. 2):

"From fairies and the tempters of the night,

Guard me, beseech ye,"

Joseph Ritson [in Dyer:] thinks Imogen refers to an incubus, a demonic creature on the order of Tarquin whom Iachimo mentions in his soliloquy in this scene. However, an archaic definition of the word is 'nightmare'. Another explanation pertains to the fairies' approval of religious people, so the prayers would have kept away fairy mischief and would have been proper behavior.

This is a fascinating post, Asmah. I managed to get to the text of the Thistleton Dyer book, but your links to books.google.com merely produce a big "image not available" box (this may not be true for you because you might be registered with a service that allows you to see the images.) I wonder if you could edit the post a little for us?

Oh I've really enjoyed these notes about fairies. Asmah, thank you for showcasing the four quotes about fairies in the play. (I also thought right away of Incubus when the fairies appeared to sleeper) And Martin, thanks for the Egyptian burial tradition link. Ray, I can imagine that Posthumus forgiving Iachimo could be poignant especially depending how the actor plays the moment.

I was wondering if the use of fairies or mention of them might help an audience believe the gender change? I wonder because what is the practical use of fairies in a story? In some ways since this play has a lot of conflict arise out of peoples assumptions regarding each other...the plays redemptive qualities are about people not being what they seem. Maybe fairies highlights the idea of humans being a layered personality...as complex as the idea of a supernatural or magic being.

The mention of fairies is partly with fear. It is ironic that Imogen or anyone should be afraid of a fairy considering all the conflict in her life came from humans competitive and cruel actions...not from anything/one otherworldly. The idea that Imogen could transform her identity and survive the cruelty of other humans....yet be afraid of a fairy is kind of strange and ironic.

One of the things that Shakespeare accomplishes with his references to magic is...he demonstrates a oral tradition of magic beings and myths long held in U.K. International travel in the Renaissance brought trade of material goods for wealthy people...but maybe it also brought myths from other countries. How did Shakespeare possibly know about Egyptian burial practices? Or did he know? Or were there rumours and stories coming back to England about customs in other countries? Would writing about folk tales and myths and strange otherworldly beings be a cultural competitive imperative. Maybe Shakespeare was introducing "exotic" into his stories to compete with stories about life and customs in other countries. Or such exotic travel accounts inspired him to incorporate folktales and otherworldy creatures into his plays.

I'm up late and my mind is rambling...I find myself very curious yet again about this magic showing up yet again in S work considering how strict the politics and religious issues were during his lifetime. It's always amazing to me how such strict societies that art can get away with breaking so many restrictions if it's exciting and entertaining etc.

I was wondering if the use of fairies or mention of them might help an audience believe the gender change? I wonder because what is the practical use of fairies in a story? In some ways since this play has a lot of conflict arise out of peoples assumptions regarding each other...the plays redemptive qualities are about people not being what they seem. Maybe fairies highlights the idea of humans being a layered personality...as complex as the idea of a supernatural or magic being.

The mention of fairies is partly with fear. It is ironic that Imogen or anyone should be afraid of a fairy considering all the conflict in her life came from humans competitive and cruel actions...not from anything/one otherworldly. The idea that Imogen could transform her identity and survive the cruelty of other humans....yet be afraid of a fairy is kind of strange and ironic.

One of the things that Shakespeare accomplishes with his references to magic is...he demonstrates a oral tradition of magic beings and myths long held in U.K. International travel in the Renaissance brought trade of material goods for wealthy people...but maybe it also brought myths from other countries. How did Shakespeare possibly know about Egyptian burial practices? Or did he know? Or were there rumours and stories coming back to England about customs in other countries? Would writing about folk tales and myths and strange otherworldly beings be a cultural competitive imperative. Maybe Shakespeare was introducing "exotic" into his stories to compete with stories about life and customs in other countries. Or such exotic travel accounts inspired him to incorporate folktales and otherworldy creatures into his plays.

I'm up late and my mind is rambling...I find myself very curious yet again about this magic showing up yet again in S work considering how strict the politics and religious issues were during his lifetime. It's always amazing to me how such strict societies that art can get away with breaking so many restrictions if it's exciting and entertaining etc.

Candy wrote: "Many extraordinary superstitions survive with regard to these islands. They were supposed to be the abode of the souls of certain Druids, who, not holy enough to enter the heaven of the Christians,..."

Candy wrote: "Many extraordinary superstitions survive with regard to these islands. They were supposed to be the abode of the souls of certain Druids, who, not holy enough to enter the heaven of the Christians,..."The material in your post is new material for me. In my reading of your links, there was the part from Sykes about Shakespeare's connection with Brecon. Another point was the details about faerie life and the short stories about their involvement in human life. Another new bit of knowledge came from your listing your favorite books about mythology. Any one of them would make a great group read.

I also think that anyone of those books would make a great group read Asmah. I've actually always hoped to have an online discussion on Marina Warner books. I think she is terrific. I first read her book From Beast To Blonde and then purchased No Go The Bogey Man. One Warner's arguments is that scary stories, fairytales, goblins and beasts are the oral tradition and credit to women storytellers. What some might label negatively as "old wives tales" Warner inspires thinking that it's actually the empowering tradition of women storytellers in what is usually thought of literature as dominated by males.

In this way...I can't help but feel that shakespere not only writes some of the most wonderful and strong female characters but he also pays homage to womens tradition of the storytelling art when he uses magic, fairies as reference, or even includes otherworldly characters into his plots (Jupiter). He may not have been using fairytale structures and devices because he was a feminist in the way we understand feminists today...but he did not scoff at the existence of this "counter-culture" world of storytelling to be found by the hearth, at bedtime for children, in the so-called gossiping of servants and maids and women. It's as if wittingly or not he validates the oral traditions of womens social and creative traditions.

In this way...I can't help but feel that shakespere not only writes some of the most wonderful and strong female characters but he also pays homage to womens tradition of the storytelling art when he uses magic, fairies as reference, or even includes otherworldly characters into his plots (Jupiter). He may not have been using fairytale structures and devices because he was a feminist in the way we understand feminists today...but he did not scoff at the existence of this "counter-culture" world of storytelling to be found by the hearth, at bedtime for children, in the so-called gossiping of servants and maids and women. It's as if wittingly or not he validates the oral traditions of womens social and creative traditions.

The birds in Cymbeline were noted in Message 64 by Martin and in Message 74 by Candy. Indeed, Chapter VI 'Birds' in Dyer's Folklore is a concordance, an alphabetical list of birds and their meanings in Shakespeare. The Crow and the wren were listed though their excerpt from Cymbeline was not there--an oversight; however, several birds from Cymbeline were there:

The birds in Cymbeline were noted in Message 64 by Martin and in Message 74 by Candy. Indeed, Chapter VI 'Birds' in Dyer's Folklore is a concordance, an alphabetical list of birds and their meanings in Shakespeare. The Crow and the wren were listed though their excerpt from Cymbeline was not there--an oversight; however, several birds from Cymbeline were there: EAGLE

As a bird of good omen it is mentioned also in "Cymbeline" (i. 1):

"I chose an eagle, And did avoid a puttock;"

and in another scene (iv. 2) the Soothsayer relates how

"Last night the very gods show'd me a vision, . . . . . . . . . . . thus: -I saw Jove's bird, the Roman eagle, wing'd From the spungy south to this part of the west, There vanish'd in the sunbeams: which portends (Unless my sins abuse my divination), Success to the Roman host." p118

In the first, Imogen argues for Posthumus over Cloten before her father; in the second, the soothsayer of the Roman camp interprets an eagle's appearance as good fortune for Rome.

HAWK

In "Cymbeline" (iii. 4), Imogen, referring to Posthumus, says:

"I grieve myself To think, when thou shalt be disedged by her That now thou tir'st on," --

this passage containing two metaphorical expressions from falconry. A bird was said to be disedged when the keenness of its appetite was taken away by tiring, or feeding upon some tough or hard substance given to it for that purpose. p127

Imogen perhaps compares how someone will tire of Posthumus in the same way he tired of her. Then, he will remember Imogen with regret.

JAY

in "Cymbeline" (iii. 4), Imogen says:

"Some jay of Italy, Whose mother was her painting,1 hath betray'd him."

1 That is, made by art: the creature not of nature, but of painting p130

This passage at Milton Haven is Imogen's response to Posthumus's letter to Pisanio--perhaps, thinking Iachimo might not have been brushed aside. There are too many Thou's in the passage and its surrounding context to fully understand despite the explanation of jay.

KITE

This bird was considered by the ancients to be unlucky.

In "Cymbeline" (i. 2), too, Imogen says,

"I chose an eagle, And did avoid a puttock,"

puttock, here, being a synonym sometimes applied to the kite. pp131-32

Marriage with eagle-like Posthumus would prove Imogen's good fortune; while marriage with Cloten would bring her misfortune.

LARK

Shakespeare has bequeathed to us many exquisite passages referring to the lark, full of the most sublime pathos and lofty conceptions. Most readers are doubtless acquainted with that superb song in "Cymbeline" (ii. 3), where this sweet songster is represented as singing " at heaven's gate;" p133

'Hark, hark, the lark...' is prettily sung by musicians at Imogen's door. The romantic song ironically contrasts with Cloten's flawed love and brash personality.

PHOENIX

1.6 IACHIMO [aside:].

All of her that is out of door most rich!

If she be furnisht with a mind so rare,

She is alone the Arabian bird; and I

Have lost the wager. Boldness be my friend!

Arm me, audacity, from head to foot!

Or, like the Parthian, I shall flying fight;

Rather, directly fly.

Malone quotes from Lyly "Euphues and his England" (p. 312, ed. Arber): "For as there is but one phœnix in the world, so is there but one tree in Arabia wherein she buyldeth;" and Florio "New Worlde of Wordes" (1598), "Rasin, a tree in Arabia, whereof there is but one found, and upon it the phoenix sits." p146

Iachimo's impression of the sleeping Imogen is of a woman endowed with supreme beauty and intelligence, a rarity comparable to the Arabian phoenix.

ROBIN REDBREAST

According to a pretty notion, this little bird is said to cover with leaves any dead body it may chance to find unburied;

Shakespeare, in a beautiful passage in "Cymbeline" (iv. 2), thus touchingly alludes to it, making Arviragus, when addressing the supposed dead body of Imogen, say:

"With fairest flowers,

Whilst summer lasts, and I live here, Fidele,

I'll sweeten thy sad grave: thou shait not lack

The flower that's like thy face, pale primrose, nor

The azured harebell, like thy veins; no, nor

The leaf of eglantine, whom not to slander

Out-sweeten'd not thy breath: the ruddock would,

With charitable bill, -- O bill, sore-shaming

Those rich-left heirs, that let their fathers lie

Without a monument! -- bring thee all this;

Yea, and furr'd moss besides, when flowers are none

To winter-ground thy cor[p:]se" -- p152

the "ruddock" 1 being one of the old names for the redbreast p153

This metaphor substitutes Arviragus's grave-covering activity with the robin's trait.

Asmah, this set of excerpts is wonderful. Thank you so much for pulling all this out and posting quotes. I'm going to read it a couple of times. Lovely and helpful!

Are we approaching the end of the read? Actually, we've said little on the final scene. But then then there is almost no end to what one might say -- one never closes a discussion of Shakespeare, instead you are just drawn deeper and deeper into his creation.

Looking back, I feel really pleased with my post #29, so it is a pity it brought no response. Perhaps the family life of Augustus is not so well known these days.

I've started watching the BBC version with Robert Lindsay and Helen Mirren again. As Asmah says, it "mesmerises and enchants".

Here is a question I have been thinking about: why is the play called "Cymbeline"? He is not after all the cental interest -- or is he?

Oh I'm still pondering this play. I'm not ready to have nothing to say. I'm not sure if it's the end of the read or not. I am processing. I want to explore the birds metaphor some more. And watch a BBC version too.

I was also going to ask...why is this play called Cymbeline. I mean...are we to ask because he should be the center. he should have been able to trouble-shoot all the conflicts, no?

I would say he was a dead-beat dad!

I was also going to ask...why is this play called Cymbeline. I mean...are we to ask because he should be the center. he should have been able to trouble-shoot all the conflicts, no?

I would say he was a dead-beat dad!

Martin wrote: "

Martin wrote: "This is a fascinating post, Asmah. I managed to get to the text of the Thistleton Dyer book, but your links to books.google.com merely produce a big "image not available" box (this may not be true..."

"Tales and Sketches" and "Mrs. Siddons" are in the public domain in the US because their copyrights have expired. Each country has different copyright laws. According to the TELEGRAPH newspaper, forty British libraries are allowing Google to digitize their books with expired copyrights:

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/technology...

The link to create a free Google Account is

https://www.google.com/accounts/NewAc...

An email address and a new password is required.

An Apple-store trainer at my next appointment might be able to clarify the reason(s) for your interrupted link. But, I think you have probably indicated the cause--registration. Thanks for the notification and for trouble-shooting the problem. Good luck.

I absolutely love the article on Google's aim to have as many books, especially out-of-print books online. I use these services and google books all the time. No, ALL. THE. TIME. I dream of a day when some of my favourite esoteric readings will be able to just be clicked on and read.

I think it will really add a whole new aspect to group discussions online too...making more people able to join in.

I think it will really add a whole new aspect to group discussions online too...making more people able to join in.

Okay, Asmah, but you should think of readers of this thread generally. It is not good practise to make links to sites that require registration in order to become visible.

Martin wrote: "

Martin wrote: "Okay, Asmah, but you should think of readers of this thread generally. It is not good practise to make links to sites that require registration in order to become visible.

"