Dickensians! discussion

Nicholas Nickleby - Group Read 6

>

Nicholas Nickleby: Chapters 24 - 36

😆 Kathleen! And I was so sure that was just a silly aside and everyone else would choose others! We must think the same way.

Charles Dickens often seems to have quirky things to say about horses, doesn't he? You probably remember bit in David Copperfield where Uriah Heep was blowing up the nostrils of a horse as he was waiting. (I don't think that's a spoiler really.)

Charles Dickens often seems to have quirky things to say about horses, doesn't he? You probably remember bit in David Copperfield where Uriah Heep was blowing up the nostrils of a horse as he was waiting. (I don't think that's a spoiler really.)

Jean, the comment about the speed of the horses made me laugh also.

Jean, the comment about the speed of the horses made me laugh also.Mrs. Nickleby does not have any problem changing her perception of things. One minute Ralph Nickleby is their saviour and the next minute she has a whole list of complaints against him.

Now we have several things to wonder about. How will Ralph Nickleby react to the current circumstances? Will their be repercussions from Nicholas' altercation with Sir Mulberry Hawk? We do not yet know what happened to him. And how ill is Nicholas?

Quite a change from what might be seen as Nicholas’s idyllic time with the country theatre. Amazing how the pace has changed and virtually every character except for the Squeers family has been involved in these chapters.

Quite a change from what might be seen as Nicholas’s idyllic time with the country theatre. Amazing how the pace has changed and virtually every character except for the Squeers family has been involved in these chapters.

I don't mean to be too pecuniary, but I couldn't help wondering how on earth Nicholas is going to provide for his mother and sister now. Kate no longer has a job and he no longer has one either. Of course, he could go back to the theater troupe, but then he is leaving them alone again. And, the cliff hanger of Hawk is still hanging out there.

I don't mean to be too pecuniary, but I couldn't help wondering how on earth Nicholas is going to provide for his mother and sister now. Kate no longer has a job and he no longer has one either. Of course, he could go back to the theater troupe, but then he is leaving them alone again. And, the cliff hanger of Hawk is still hanging out there.My quote would be from Nicholas' letter: You are an old man, and I leave you to the grave. May every recollection of your life cling to your false heart, and cast their darkness on your death-bed.

To me, that was brilliantly scathing and perhaps the worst curse he could put upon this horrid man.

Sue wrote: "Quite a change from what might be seen as Nicholas’s idyllic time with the country theatre. Amazing how the pace has changed and virtually every character except for the Squeers family has been inv..."

Sue wrote: "Quite a change from what might be seen as Nicholas’s idyllic time with the country theatre. Amazing how the pace has changed and virtually every character except for the Squeers family has been inv..."Indeed Sue!

Dickens knows how to keep his readers waiting for a development of a rather intricate, even desperate situation, Sara.

There is most probably a solution for the uncertain future of the Nicklebies (this is a novel after all, with installments yet to be published), but there is also, which is just as worrying, an impending threat on Nicholas too, as he very powerfully cursed his uncle and Ralph has most probably some means for retaliation.

I spotted the horses as well and enjoyed this much, especially their perspective of breakfasting in Whitechapel. Indeed horses are generally more in a hurry on their way back to the stables or to pastures and friends with a perspective of eating something after work, than on the the way out of the stables.

Bionic Jean wrote: "And well done everyone; we are now half way through this long novel..."

Bionic Jean wrote: "And well done everyone; we are now half way through this long novel..."I just wanted to pop in and say thank you, Jean, for making this read as enjoyable and enlightening as ever and for such great summaries and additional information that help us appreciate the story so much more. It's hard to believe we're already halfway through. It's gone by so fast! Thank you!

Katy wrote: "Mrs. Nickleby does not have any problem changing her perception of things..."

I spend a lot of time trying to fathom out her psychology, with such a butterfly mind. This aspect is quite childlike, isn't it?

Oh yes, lots of unanswered questions from ch 33 Katy. Let's hope for some answers today.

I spend a lot of time trying to fathom out her psychology, with such a butterfly mind. This aspect is quite childlike, isn't it?

Oh yes, lots of unanswered questions from ch 33 Katy. Let's hope for some answers today.

Sue wrote: "Quite a change from what might be seen as Nicholas’s idyllic time with the country theatre. Amazing how the pace has changed and virtually every character except for the Squeers family has been involved in these chapters ..."

What a great observation Sue! You'll probably remember the "streaky bacon" statement about life's variety from Oliver Twist, coming just after he withdrew his resignation to Richard Bentley, and decided to carry on with the serial. The chops and changes in Nicholas Nickleby seem to be a testament to his experience of life, don't they.

And as for your last comment, well perhaps that was in Charles Dickens's mind too ... you will smile when you read today's chapter, and can pat yourself on the back LOL!

What a great observation Sue! You'll probably remember the "streaky bacon" statement about life's variety from Oliver Twist, coming just after he withdrew his resignation to Richard Bentley, and decided to carry on with the serial. The chops and changes in Nicholas Nickleby seem to be a testament to his experience of life, don't they.

And as for your last comment, well perhaps that was in Charles Dickens's mind too ... you will smile when you read today's chapter, and can pat yourself on the back LOL!

Sara wrote: "I don't mean to be too pecuniary, but I couldn't help wondering how on earth Nicholas is going to provide for his mother and sister now ..."

Oh yes Sara, I agree! I think Nicholas has the volatile emotions of any - or at least many - young men, and always acts honourably, but although he accepts the responsibilities of a Victorian gentleman, he seems more bothered about defending his family's honour than their survival.

To some extent he is a little like his mother (although I can hear Nicholas shouting angry objections to me in my mind 😆) in that he lives in the moment. Yes, he has plans, but so far they are short term and hand to mouth, involve moving about and selling furniture and clothes. His big plans seem just as undefined as his mother's wanderings - just castles in the air 🤔

Your favourite quotation sends a chill down my spine every time I read it. That was such a powerful letter, straight from the heart, and ending with a deadly curse. 😟

Oh yes Sara, I agree! I think Nicholas has the volatile emotions of any - or at least many - young men, and always acts honourably, but although he accepts the responsibilities of a Victorian gentleman, he seems more bothered about defending his family's honour than their survival.

To some extent he is a little like his mother (although I can hear Nicholas shouting angry objections to me in my mind 😆) in that he lives in the moment. Yes, he has plans, but so far they are short term and hand to mouth, involve moving about and selling furniture and clothes. His big plans seem just as undefined as his mother's wanderings - just castles in the air 🤔

Your favourite quotation sends a chill down my spine every time I read it. That was such a powerful letter, straight from the heart, and ending with a deadly curse. 😟

Claudia wrote: "there is also, which is just as worrying, an impending threat on Nicholas too ..."

Yes we have good reason to worry Claudia. Ralph just seemed stunned - even initially rigid with shock:

"the paper fluttered from his hand and dropped upon the floor, but he clasped his fingers, as if he held it still"

but then we were told he was furious. And a furious, resentful man with a clever mind like Ralph Nickleby's is not to be treated lightly. 😲

Yes we have good reason to worry Claudia. Ralph just seemed stunned - even initially rigid with shock:

"the paper fluttered from his hand and dropped upon the floor, but he clasped his fingers, as if he held it still"

but then we were told he was furious. And a furious, resentful man with a clever mind like Ralph Nickleby's is not to be treated lightly. 😲

Shirley (stampartiste) wrote: "

I just wanted to pop in and say thank you, Jean, for making this read as enjoyable and enlightening as ever..."

Aw, thank you Shirley! I'm also getting so much out of it, with new highlights and perspectives coming from everyone 😊

So let's move on, and today's chapter begins with everyone's favourite creative and crafty dandy (although can I hear groans from part of the audience? ...)

I just wanted to pop in and say thank you, Jean, for making this read as enjoyable and enlightening as ever..."

Aw, thank you Shirley! I'm also getting so much out of it, with new highlights and perspectives coming from everyone 😊

So let's move on, and today's chapter begins with everyone's favourite creative and crafty dandy (although can I hear groans from part of the audience? ...)

Installment 11

Chapter 34: Wherein Mr. Ralph Nickleby is visited by Persons with whom the Reader has been already made acquainted

Mr. Mantalini has called on Ralph Nickleby and is angry that Noggs has taken so long to open the door. Noggs implies that Ralph Nickleby doesn’t want to be disturbed, and asks if the matter is pressing:

“‘It is most demnebly particular,’ said Mr. Mantalini. ‘It is to melt some scraps of dirty paper into bright, shining, chinking, tinkling, demd mint sauce.’”

Noggs enters the office and sees Ralph rereading Nicholas’s letter. Mr. Mantalini swaggers in before Noggs can announce him. Mr. Mantalini wants some money, in exchange for some bills worth £75.

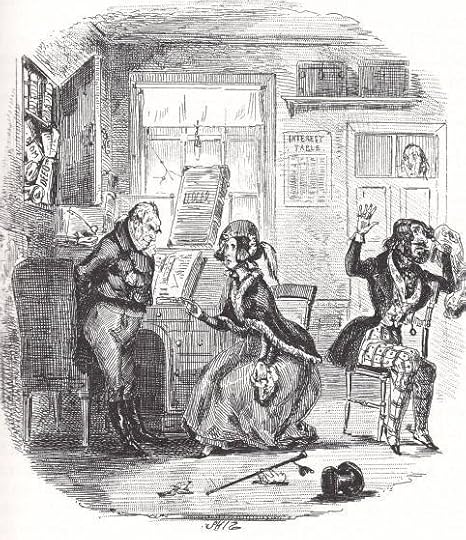

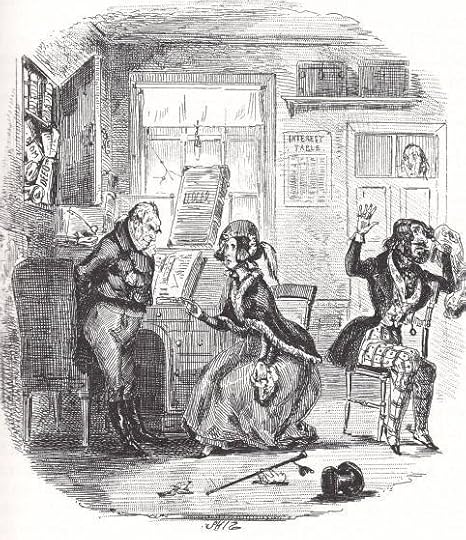

“Mr. Alfred Mantalini - Mantalini touches Ralph Nickleby for a loan” - Harry Furniss - 1910

Ralph agrees to do it for twenty-five pounds, leaving Mr Mantalini £50. Mr. Mantalini grumbles, but eventually agrees. Madame Mantalini arrives unexpectedly, and Mr. Mantalini quickly puts the money in his pocket.

She tells her husband that she is ashamed of him, whereupon he starts talking sweet nothings about her:

“naughty fibs … It knows it is not ashamed of its own popolorum tibby.”

Madame Mantalini vows she will not be ruined by his extravagance and gross misconduct again:

“’Of me, my essential juice of pineapple! … Will she call me “Sir”?’ cried Mantalini. ‘Me who dote upon her with the demdest ardour! She, who coils her fascinations round me like a pure angelic rattlesnake! It will be all up with my feelings; she will throw me into a demd state.’”

Madame Mantalini accuses her husband of stealing some papers from her desk. She is now obligated to pay Miss Knag as a partner, but knows that her husband took the papers to convert them into money. She decides she is going to put him on an allowance, and wants Ralph Nickleby to witness it. He refuses. Telling them to settle it between themselves, he:

“leant against his easy-chair with his hands behind him, and regarded the amiable couple with a smile of the supremest and most unmitigated contempt.”

“Dunning a Loan Shark - Mr. and Mrs. Mantalini in Ralph Nickleby’s Office - Hablot K. Browne - February 1839

Mr. Mantalini laments his fate. He threatens to drown himself, although he says he can’t be angry with his lovely wife. She will make a beautiful widow, and:

“I shall require no demd allowance. I will be a body.”

Madame Mantalini gets upset by this talk, which:

“brought fresh tears into Madame Mantalini’s eyes, which having just begun to open to some few of the demerits of Mr. Mantalini, were only open a very little way, and could be easily closed again.”

She cries a bit, and he agrees not to become a body. However, he cannot stand the thought of being mistrusted by her, so she agrees to postpone the decision. Ralph watches this scene scornfully, thinking how blind love only puts money in his own pocket.

As they are leaving, Mr. Mantalini draws Ralph Nickleby into a corner and brings up the subject of Sir Mulberry Hawk. Ralph is not very interested, claiming that he had seen the paper’s accounts of the incident. He read that Sir Mulberry Hawk had been thrown from a carriage and severely injured, so that his condition is considered critical. It was not surprising, he says: “when men live hard, and drive after dinner”.

Ralph glances at Noggs skulking nearby, who knows that this is a hint that it is time for Mr Mantalini to leave. However Mr Mantalini tells Ralph it had not been an accident, but that Ralph’s nephew had tried to kill Mulberry Hawk.

“‘What!’ snarled Ralph, clenching his fists and turning a livid white”

and demands to know more. Mr Mantalini, alarmed at his “tigerish” demeanour, says that Mr. Pyke had told him so, and that the quarrel had been over Nicholas’s sister.

“’And was killed?’ interposed Ralph with gleaming eyes. ‘Was he? Is he dead? …He broke a leg or an arm, or put his shoulder out, or fractured his collar-bone, or ground a rib or two? His neck was saved for the halter, but he got some painful and slow-healing injury for his trouble? Did he? You must have heard that, at least.’”

But to Ralph’s disappointment, Mr Mantalini denies it all.

After the Mantalinis leave, Noggs tells him that someone is waiting to see him, and Mr. Squeers pushes his way in.

He introduces his son Wackford, praising his healthy plumpness as an example of Dotheboys Hall feeding:

“A ”Streaky Bacon“ Comic Scene after the Melodramatic Exchanges” - Fred Barnard - 1875

“”Here’s flesh!’ cried Squeers, turning the boy about, and indenting the plumpest parts of his figure with divers pokes and punches, to the great discomposure of his son and heir. ‘Here’s firmness, here’s solidness!“”

Ralph Nickleby, unusually polite, enquires after Mrs. Squeers. Mr. Squeers says she is “a mother to them lads, and a blessing, and a comfort, and a joy to all them as knows her” and adds that she had operated on one of their boys with a pen-knife after he developed an abscess from eating too much.

On being asked if he has recovered from recovered “that scoundrel’s attack”, Squeers says he has only just recovered from his injuries, which have been painful. It ran up quite a medical bill, but he paid it as it didn’t come out of his own pocket. Whenever one of the Squeers family needs medical attention, they expose the boys who have paying parents to some ailment like scarlet fever. They add their own medical expenses to the boys’ bills, and the parents pay for it.

“‘And a good plan too,’ said Ralph, eyeing the schoolmaster stealthily.”

Squeers is there about a charge of neglect. When the children won’t eat what is offered at the school, the Squeers “turn him out, for an hour or so every day, into a neighbour’s turnip field, or sometimes, if it’s a delicate case, a turnip field and a piece of carrots alternately, and let him eat as many as he likes.”. One child became ill and Squeers say that his ungrateful friends have brought a law suit against him.

“Ralph entertains Wackford Squeers - ‘Look at them tears, sir! … There’s oiliness!’” - Charles Stanley Reinhart - 1875

Ralph Nickleby asks for a word with Squeers, and Wackford is sent off with twopence to buy a tart, as “Pastry … makes his flesh shine a good deal, and parents thinks that a healthy sign.”

Now alone, Ralph says that he assumes Squeers wants compensation for the injuries Nicholas inflicted upon him. He asks Squeers about the boy that Nicholas took with him; whether he was “young or old, healthy or sickly, tractable or rebellious”.

Squeers says that the boy is around twenty years of age, but he not very bright. He had been brought to the school by a stranger when he was five or six years old. The man paid £5.5 shillings in advance for the first quarter, and continued to pay for six to eight years. Squeers didn’t know anything about the boy or the man, but when the man stopped paying, Squeers followed up the address the man had given him. It didn’t give him any leads as to the man’s identity, so he kept the boy out of … and Ralph suggests the word “charity”. Just when the boy became useful, Nicholas stole him away: “The most vexatious and aggeravating part of the whole affair is” that someone has been asking about him, and Squeers cannot profit in restoring him to the interested party.

Ralph tells Squeers that they will both have their revenge on Nicholas soon:

“We will talk of this again … I must have time to think of it. To wound him through his own affections and fancies—. If I could strike him through this boy—”

On his way out, Squeers boasts to Noggs that his son is fatter than twenty boys and Noggs says that is probably because he eats the food of twenty boys. Squeers is offended, but he decides that Noggs is a madman and a drunk.

Ralph’s regard for Kate has increased, and now his hatred of Nicholas increases too. He is resentful that Kate will be taught to despise him, and it is all because of her arrogant brother, who defied him from the start. If he could find a quiet, hidden way to exact revenge, he would do it. Ralph thinks all day about it, but cannot form a plan

He recalls how people used to favour his brother over him, for his honesty and generous nature. Ralph was considered crafty, cold, and greedy. He had been reminded of his brother when he first saw Nicholas. He tears Nicholas’s letter into tiny shreds, thinking that when he lets himself remember, such thoughts flood his mind, from many situations. He decides:

“As a portion of the world affect to despise the power of money, I must try and show them what it is.”

And having deciding to exert his power, he sleeps soundly.

Chapter 34: Wherein Mr. Ralph Nickleby is visited by Persons with whom the Reader has been already made acquainted

Mr. Mantalini has called on Ralph Nickleby and is angry that Noggs has taken so long to open the door. Noggs implies that Ralph Nickleby doesn’t want to be disturbed, and asks if the matter is pressing:

“‘It is most demnebly particular,’ said Mr. Mantalini. ‘It is to melt some scraps of dirty paper into bright, shining, chinking, tinkling, demd mint sauce.’”

Noggs enters the office and sees Ralph rereading Nicholas’s letter. Mr. Mantalini swaggers in before Noggs can announce him. Mr. Mantalini wants some money, in exchange for some bills worth £75.

“Mr. Alfred Mantalini - Mantalini touches Ralph Nickleby for a loan” - Harry Furniss - 1910

Ralph agrees to do it for twenty-five pounds, leaving Mr Mantalini £50. Mr. Mantalini grumbles, but eventually agrees. Madame Mantalini arrives unexpectedly, and Mr. Mantalini quickly puts the money in his pocket.

She tells her husband that she is ashamed of him, whereupon he starts talking sweet nothings about her:

“naughty fibs … It knows it is not ashamed of its own popolorum tibby.”

Madame Mantalini vows she will not be ruined by his extravagance and gross misconduct again:

“’Of me, my essential juice of pineapple! … Will she call me “Sir”?’ cried Mantalini. ‘Me who dote upon her with the demdest ardour! She, who coils her fascinations round me like a pure angelic rattlesnake! It will be all up with my feelings; she will throw me into a demd state.’”

Madame Mantalini accuses her husband of stealing some papers from her desk. She is now obligated to pay Miss Knag as a partner, but knows that her husband took the papers to convert them into money. She decides she is going to put him on an allowance, and wants Ralph Nickleby to witness it. He refuses. Telling them to settle it between themselves, he:

“leant against his easy-chair with his hands behind him, and regarded the amiable couple with a smile of the supremest and most unmitigated contempt.”

“Dunning a Loan Shark - Mr. and Mrs. Mantalini in Ralph Nickleby’s Office - Hablot K. Browne - February 1839

Mr. Mantalini laments his fate. He threatens to drown himself, although he says he can’t be angry with his lovely wife. She will make a beautiful widow, and:

“I shall require no demd allowance. I will be a body.”

Madame Mantalini gets upset by this talk, which:

“brought fresh tears into Madame Mantalini’s eyes, which having just begun to open to some few of the demerits of Mr. Mantalini, were only open a very little way, and could be easily closed again.”

She cries a bit, and he agrees not to become a body. However, he cannot stand the thought of being mistrusted by her, so she agrees to postpone the decision. Ralph watches this scene scornfully, thinking how blind love only puts money in his own pocket.

As they are leaving, Mr. Mantalini draws Ralph Nickleby into a corner and brings up the subject of Sir Mulberry Hawk. Ralph is not very interested, claiming that he had seen the paper’s accounts of the incident. He read that Sir Mulberry Hawk had been thrown from a carriage and severely injured, so that his condition is considered critical. It was not surprising, he says: “when men live hard, and drive after dinner”.

Ralph glances at Noggs skulking nearby, who knows that this is a hint that it is time for Mr Mantalini to leave. However Mr Mantalini tells Ralph it had not been an accident, but that Ralph’s nephew had tried to kill Mulberry Hawk.

“‘What!’ snarled Ralph, clenching his fists and turning a livid white”

and demands to know more. Mr Mantalini, alarmed at his “tigerish” demeanour, says that Mr. Pyke had told him so, and that the quarrel had been over Nicholas’s sister.

“’And was killed?’ interposed Ralph with gleaming eyes. ‘Was he? Is he dead? …He broke a leg or an arm, or put his shoulder out, or fractured his collar-bone, or ground a rib or two? His neck was saved for the halter, but he got some painful and slow-healing injury for his trouble? Did he? You must have heard that, at least.’”

But to Ralph’s disappointment, Mr Mantalini denies it all.

After the Mantalinis leave, Noggs tells him that someone is waiting to see him, and Mr. Squeers pushes his way in.

He introduces his son Wackford, praising his healthy plumpness as an example of Dotheboys Hall feeding:

“A ”Streaky Bacon“ Comic Scene after the Melodramatic Exchanges” - Fred Barnard - 1875

“”Here’s flesh!’ cried Squeers, turning the boy about, and indenting the plumpest parts of his figure with divers pokes and punches, to the great discomposure of his son and heir. ‘Here’s firmness, here’s solidness!“”

Ralph Nickleby, unusually polite, enquires after Mrs. Squeers. Mr. Squeers says she is “a mother to them lads, and a blessing, and a comfort, and a joy to all them as knows her” and adds that she had operated on one of their boys with a pen-knife after he developed an abscess from eating too much.

On being asked if he has recovered from recovered “that scoundrel’s attack”, Squeers says he has only just recovered from his injuries, which have been painful. It ran up quite a medical bill, but he paid it as it didn’t come out of his own pocket. Whenever one of the Squeers family needs medical attention, they expose the boys who have paying parents to some ailment like scarlet fever. They add their own medical expenses to the boys’ bills, and the parents pay for it.

“‘And a good plan too,’ said Ralph, eyeing the schoolmaster stealthily.”

Squeers is there about a charge of neglect. When the children won’t eat what is offered at the school, the Squeers “turn him out, for an hour or so every day, into a neighbour’s turnip field, or sometimes, if it’s a delicate case, a turnip field and a piece of carrots alternately, and let him eat as many as he likes.”. One child became ill and Squeers say that his ungrateful friends have brought a law suit against him.

“Ralph entertains Wackford Squeers - ‘Look at them tears, sir! … There’s oiliness!’” - Charles Stanley Reinhart - 1875

Ralph Nickleby asks for a word with Squeers, and Wackford is sent off with twopence to buy a tart, as “Pastry … makes his flesh shine a good deal, and parents thinks that a healthy sign.”

Now alone, Ralph says that he assumes Squeers wants compensation for the injuries Nicholas inflicted upon him. He asks Squeers about the boy that Nicholas took with him; whether he was “young or old, healthy or sickly, tractable or rebellious”.

Squeers says that the boy is around twenty years of age, but he not very bright. He had been brought to the school by a stranger when he was five or six years old. The man paid £5.5 shillings in advance for the first quarter, and continued to pay for six to eight years. Squeers didn’t know anything about the boy or the man, but when the man stopped paying, Squeers followed up the address the man had given him. It didn’t give him any leads as to the man’s identity, so he kept the boy out of … and Ralph suggests the word “charity”. Just when the boy became useful, Nicholas stole him away: “The most vexatious and aggeravating part of the whole affair is” that someone has been asking about him, and Squeers cannot profit in restoring him to the interested party.

Ralph tells Squeers that they will both have their revenge on Nicholas soon:

“We will talk of this again … I must have time to think of it. To wound him through his own affections and fancies—. If I could strike him through this boy—”

On his way out, Squeers boasts to Noggs that his son is fatter than twenty boys and Noggs says that is probably because he eats the food of twenty boys. Squeers is offended, but he decides that Noggs is a madman and a drunk.

Ralph’s regard for Kate has increased, and now his hatred of Nicholas increases too. He is resentful that Kate will be taught to despise him, and it is all because of her arrogant brother, who defied him from the start. If he could find a quiet, hidden way to exact revenge, he would do it. Ralph thinks all day about it, but cannot form a plan

He recalls how people used to favour his brother over him, for his honesty and generous nature. Ralph was considered crafty, cold, and greedy. He had been reminded of his brother when he first saw Nicholas. He tears Nicholas’s letter into tiny shreds, thinking that when he lets himself remember, such thoughts flood his mind, from many situations. He decides:

“As a portion of the world affect to despise the power of money, I must try and show them what it is.”

And having deciding to exert his power, he sleeps soundly.

I think we have the clearest indication yet of Ralph Nickleby’s motivation with his thoughts in this chapter. He is consumed with envy, because when they were both boys, his brother was liked for being:

“open, liberal, gallant, gay; I a crafty hunk of cold and stagnant blood, with no passion but love of saving, and no spirit beyond a thirst for gain.”

Since young Nicholas is very like his father, Ralph is jealous.

“open, liberal, gallant, gay; I a crafty hunk of cold and stagnant blood, with no passion but love of saving, and no spirit beyond a thirst for gain.”

Since young Nicholas is very like his father, Ralph is jealous.

Thoughts on Mr Mantalini

Both Mrs Nickleby and Mr Mantalini make bewildering fragmentary speeches, although they inhabit different worlds. Mrs Nickleby’s are detailed and give the impression of an inner monologue which we happen to be listening in on. A listener has to wait patiently to hear anything of substance, and so far we have see that Kate does this better than Nicholas. Nothing said by Mrs Nickleby has had any effect on the action. She remains outside the book’s narrative.

We’ve noticed before that Mr Mantalini’s fantasies are exotic and creative, compared with Mrs Nickleby’s. They bedazzle and disarm his doting wife. He’s a spendthrift and a dandy, but she is dependent on his adoring nonsense. It seems to validate her self-image.

His endearments are always paradoxical, such as a “pure and angelic rattle-snake” or “twisting her face into bewitching nutcrackers” which is why they are so entertaining to read.

In this chapter his suicide threats are stepped up:

“Have I cut my heart into a demd extraordinary number of little pieces, and given them all away, one after another, to the same little engrossing demnition captivater,”

becoming increasingly bizarre and incongruous:

“I will fill my pockets with change for a sovereign in halfpence and drown myself in the Thames; but I will not be angry with her, even then, for I will put a note in the twopenny-post as I go along, to tell her where the body is. She will be a lovely widow. I shall be a body. Some handsome women will cry; she will laugh demnebly.”

They are hilarious, unpleasant and also accurate about the physical world:

“me—who for her sake will become a demd, damp, moist, unpleasant body!”

And it works. He has an impact on the action, and for whatever reason, Mrs Mantalini is persuaded that she is an essential part of his life, and he of hers.

Mr Mantalini however, has been frightened by Ralph Nickleby’s surprisingly sudden display of fury - as indeed are we. Up to now, Ralph Nickleby has shown little emotion, and more of a cold, calculating cunning. But hearing that Nicholas had attacked one of his best clients makes him fly into a very theatrical, villainous rage, snarling and “clenching his fists and turning a livid white”. Then just as suddenly he turns back, claiming that it is only manner.

Here the roles are switched, as Mantalini’s reaction seems to be genuinely complaining, not at all posed: “It’s a demd uncomfortable and private-madhouse-sort of manner.”

Both Mrs Nickleby and Mr Mantalini make bewildering fragmentary speeches, although they inhabit different worlds. Mrs Nickleby’s are detailed and give the impression of an inner monologue which we happen to be listening in on. A listener has to wait patiently to hear anything of substance, and so far we have see that Kate does this better than Nicholas. Nothing said by Mrs Nickleby has had any effect on the action. She remains outside the book’s narrative.

We’ve noticed before that Mr Mantalini’s fantasies are exotic and creative, compared with Mrs Nickleby’s. They bedazzle and disarm his doting wife. He’s a spendthrift and a dandy, but she is dependent on his adoring nonsense. It seems to validate her self-image.

His endearments are always paradoxical, such as a “pure and angelic rattle-snake” or “twisting her face into bewitching nutcrackers” which is why they are so entertaining to read.

In this chapter his suicide threats are stepped up:

“Have I cut my heart into a demd extraordinary number of little pieces, and given them all away, one after another, to the same little engrossing demnition captivater,”

becoming increasingly bizarre and incongruous:

“I will fill my pockets with change for a sovereign in halfpence and drown myself in the Thames; but I will not be angry with her, even then, for I will put a note in the twopenny-post as I go along, to tell her where the body is. She will be a lovely widow. I shall be a body. Some handsome women will cry; she will laugh demnebly.”

They are hilarious, unpleasant and also accurate about the physical world:

“me—who for her sake will become a demd, damp, moist, unpleasant body!”

And it works. He has an impact on the action, and for whatever reason, Mrs Mantalini is persuaded that she is an essential part of his life, and he of hers.

Mr Mantalini however, has been frightened by Ralph Nickleby’s surprisingly sudden display of fury - as indeed are we. Up to now, Ralph Nickleby has shown little emotion, and more of a cold, calculating cunning. But hearing that Nicholas had attacked one of his best clients makes him fly into a very theatrical, villainous rage, snarling and “clenching his fists and turning a livid white”. Then just as suddenly he turns back, claiming that it is only manner.

Here the roles are switched, as Mantalini’s reaction seems to be genuinely complaining, not at all posed: “It’s a demd uncomfortable and private-madhouse-sort of manner.”

Then we have another "streaky bacon-esqe" comic and grotesque scene with Squeers. I wonder if Dickens brought him back into the story at this point, because of the fan letter he had just received from Thomas Hughes’s little brother …

I’ll leave commenting further on this one, and look forward to your thoughts 😊

I’ll leave commenting further on this one, and look forward to your thoughts 😊

Bionic Jean wrote: "Mr. Mantalini wants some money, in exchange for some bills worth £75."

Bionic Jean wrote: "Mr. Mantalini wants some money, in exchange for some bills worth £75."WOW!

That's usury and loan-sharking writ large. £50 to purchase £75 in two accounts due in 2 months and 4 months, say 3 months for the total amount to average it out. That's a £25 interest fee for a £50 advance for 3 months. My math reckons that to be 200% interest with Nickleby's only remaining risk predicated on the credit worthiness of Mrs Mantalini's original buyers. And, of course, it's safe to assume that they were solid enough for Mrs Mantalini to have extended them credit in the first instance.

I wonder if Nickleby has got his hooks that deeply into Mulberry Hawk and Lord Verisopht as well!

Ralph is a particularly dangerous adversary because he generally does keep his temper and he has numerous ways of coming after an enemy--using other despicable people and lying being two of his best. I am now just as worried for Smike as for Nicholas. This news of someone having an interest in him is good/bad news. He might have a family who are looking for him or an inheritance, but it puts him in the spotlight and makes him a very desirable target for Ralph and Squeers.

Ralph is a particularly dangerous adversary because he generally does keep his temper and he has numerous ways of coming after an enemy--using other despicable people and lying being two of his best. I am now just as worried for Smike as for Nicholas. This news of someone having an interest in him is good/bad news. He might have a family who are looking for him or an inheritance, but it puts him in the spotlight and makes him a very desirable target for Ralph and Squeers.I particularly dislike the Mantalinis and I'm not even sure why...they just get on my last nerve (as my step-daughter used to say).

Squeers is definitely awful.

Squeers is definitely awful. He considering the boys worse than animals. Even Ralph Nickleby who is no paragon of charity, raises an eyebrow when he hears that the boy ("this perwerse lad grazed on") who caught an indigestion, although he "had a good grazing".

But Squeers' visit provides some bits and pieces of additional information on Smike.

More worrying, Ralph has the same reaction regarding Smike as Miss Squeers when she retaliated Nicholas' refusal and had her parents torment Smike.

"To wound him [Nicholas] through his own affections and fancies - If I could only strike him through this boy."

Poor Smike. He is doomed to be the whipping boy of a bunch of "perwerse" persons.

In my last post I mentioned I was using Jean's multiphrenia comments as an opportunity for jumping back into the discussion especially since the term falls under the umbrellas of psychology, and I am finding Nicholas Nickleby full of thought provoking writing relating to psychology. Some examples are from where Dickens dips into the subject in his writing into the behaviors, motivations, and thought processes of his characters. Other examples provoke us into considering ideas about Dickens himself based on what we see him evidence in the characters. Whichever angle one is proceeding from, Nicholas Nickleby is exceptionally stimulating with a number of ideas to explore.

In my last post I mentioned I was using Jean's multiphrenia comments as an opportunity for jumping back into the discussion especially since the term falls under the umbrellas of psychology, and I am finding Nicholas Nickleby full of thought provoking writing relating to psychology. Some examples are from where Dickens dips into the subject in his writing into the behaviors, motivations, and thought processes of his characters. Other examples provoke us into considering ideas about Dickens himself based on what we see him evidence in the characters. Whichever angle one is proceeding from, Nicholas Nickleby is exceptionally stimulating with a number of ideas to explore. I had been preoccupying myself with parallels between Oliver Twist and Nicholas Nickleby for most of my thoughts on this earlier but I feel there is more than enough examples to start looking at specific examples in Nicholas Nickleby more closely on their own or in relation to ideas of the time or where Dickens is departing from ideas of the time. Unfortunately, being ignorant of most of the ideas of the time, I am afraid I can only broach the topic and perhaps get some of you interested, though I think this is a fascinating topic to explore in this novel. I did find a book Dickens and Victorian Psychology: Introspection, First-Person Narration, and the Mind byTyson Stolte that might be of interest but I'll have to find a library copy somewhere as it is too pricey for me. I will add some thoughts on this next post but wanted to note this now because Ralph's motivation for behavior is in this chapter and we are potentially breaking from the parallels with Oliver Twist given that other novel would not be having as much immediate influence on Dickens' writing. Any thoughts from anyone also pursuing this topic would be welcome, especially background on influencers on the topic of psychology at the time like Jeremy Bentham.

It is almost unbearable for a long chapter filled with characters that just make us cringe. The Mantalinis are insufferable and he is over the top melodramatic. I can just see the actor playing him on the stage. I think it would be an exhausting role. His interactions with his “life and soul” are very humorous and give quite a bit of comic relief along with our eye rolls! Mr. Mantalini’s everyday clothes are more like costumes worn for the stage.

It is almost unbearable for a long chapter filled with characters that just make us cringe. The Mantalinis are insufferable and he is over the top melodramatic. I can just see the actor playing him on the stage. I think it would be an exhausting role. His interactions with his “life and soul” are very humorous and give quite a bit of comic relief along with our eye rolls! Mr. Mantalini’s everyday clothes are more like costumes worn for the stage.Squeers is despicable, no other words. Laughing at his treatment of boys, getting them sick just to have a way to pay his own medical bills through their families. Horrible. I can only imagine what might happen to Squeers if Nicholas were to run into him again. Could Nicholas hold his cool? Doubt it.

I am also interested in the little bits we’ve learned about Smike.

Bionic Jean wrote: "Nose-pulling: I've been looking into nose-pulling, and can say that we "Dickensians!" are one up on the..."

Bionic Jean wrote: "Nose-pulling: I've been looking into nose-pulling, and can say that we "Dickensians!" are one up on the..."Ch 29, Message 115,116

Fascinating comments by Shirleyand Jean about finding the earliest usage of a word for the Oxford English Dictionary. I would not have had a clue what they were talking about had I not recently read The Dictionary of Lost Words by Pip Williams !

Very interesting how words and expressions make their way into the permanent lexicon of the English language!

Oh, I agree with Lori regarding this long chapter! I had a very hard time reading this chapter because it was so full of evil, conniving men who lived off the misery of the people in their lives.

Oh, I agree with Lori regarding this long chapter! I had a very hard time reading this chapter because it was so full of evil, conniving men who lived off the misery of the people in their lives.Ralph Nickleby: He has a long way to go before his heart, like the Grinch (or like Scrooge), "grows three sizes that day." Two thoughts I had on Ralph: 1. "You are who you associate with". It is no wonder he is so cynical about people, when he surrounds himself with people who engender that feeling. And 2. Ralph's musings about his brother's goodness and his jealousy of him immediately brought to mind the relationship between Cain and Abel. It was Cain's jealousy of Abel that caused him to murder his brother, and I fear that Ralph has that same kind of jealousy of his brother and by extension, his nephew Nicholas.

2. The Mantalinis: (Won't we ever be rid of him?!). I'm glad Sam brought up the subject of psychology. I don't know if the term was in use in Dickens' time, but I find the Mantalinis have what is termed a "toxic, codependent relationship." It's a hard relationship to watch. Wake up, Mrs. Mantalini!

3.The Squeers: What a vile couple they are to knowingly expose the children under their care to deadly diseases, in order for the parents of these children to pay their own medical bills. And to operate on a child with a penknife to save money and expose that child to infection and death. They deserve the gallows! I hope their downfall comes at the hands of that sweet Smike!

Yay! I've finally caught up with the rest of you, having now read into Chapter 35. :-)

Yay! I've finally caught up with the rest of you, having now read into Chapter 35. :-)Nicholas definitely is high-spirited and impetuous. But personally, I don't fault him for any of his three physical altercations with other characters here. By way of background, when my daughters were of grade-school age and attending public schools, I always used to tell them, if some other kid spoke insulting words to them, to just ignore it --but if someone put hands on their body to hurt them, to use the minimum amount of force necessary to ensure that they stopped. I still consider that a good operating rule.

In each of these instances, Nicholas' behavior has conformed to the same standard. He didn't hit Squeers until the latter spat on him and struck him in the face with a cane; and he stopped once his assailant was immobilized. Mr. Lenville didn't touch him, but was approaching him with the announced intention of doing so (which is in principle the same thing); Nicholas forestalled him and nipped the action in the bud. And Hawk was the one that started using the whip to lash Nicholas, not the other way around. IMO, it's wrong to aggressively initiate violence against others; but it's not a good idea to let aggressors mistreat you (or others) at will, either.

Great point, Werner (and so happy you have caught up). I don't fault Nicholas either. These men have, in fact, deserved much worse than they have received. Squeers particularly should be beaten to a pulp by someone for what he does to those boys!

Great point, Werner (and so happy you have caught up). I don't fault Nicholas either. These men have, in fact, deserved much worse than they have received. Squeers particularly should be beaten to a pulp by someone for what he does to those boys!

Fully agree Sara!! I'm generally opposed to violence, but I wouldn't hesitate to pull Squeers nose - or worse - if given the opportunity!

Fully agree Sara!! I'm generally opposed to violence, but I wouldn't hesitate to pull Squeers nose - or worse - if given the opportunity!I get weary of the Matalini's and their dysfunctional marriage like everyone else, but I did have a good laugh at "my essential juice of pine-apple" LOL.

A thought occurred to me in this chapter, which I hesitate to share because it may be unpopular, and its that I see some similarities between Ralph and Nicholas, in the way they fly to anger so easily. Of course Nicholas is justified in the anger he has shown, and more importantly Nicholas is a good person - and Ralph is not. But this fiery emotion wasn't something Nicholas's father had, instead it might be something Nicholas shares with his uncle.

I had been wondering if there was sibling rivalry between Ralph Nickleby and Nicholas' father all through this book. As Jean and Shirley have mentioned, it has shown up in this chapter.

I had been wondering if there was sibling rivalry between Ralph Nickleby and Nicholas' father all through this book. As Jean and Shirley have mentioned, it has shown up in this chapter.A miser would have just put Nicholas in some poor position in the city, and forgot about him. But Ralph sent him far away to Squeers to what he knew was a terrible place of employment. It was a punishment for a young man that he didn't even know. Nicholas seems spirited, intelligent, likable, and handsome--just like his father. Nicholas is resented because his father was loved by other people, and Ralph was not. Ralph has never lost that feeling of jealousy. He's also lost the opportunity to develop a good relationship with his nephew and niece which might have been a help and a comfort as he ages.

Jean, yes I was surprised when I found Squeers and son pop up in this chapter after my comment in the last :) And poor Wackford! I know there’s nothing good about him, but he’s being fattened up like the family pig, but here in order to bring in more students rather than to sell at market or butcher for dinner!

Jean, yes I was surprised when I found Squeers and son pop up in this chapter after my comment in the last :) And poor Wackford! I know there’s nothing good about him, but he’s being fattened up like the family pig, but here in order to bring in more students rather than to sell at market or butcher for dinner!

Sam wrote: "In my last post I mentioned I was using Jean's multiphrenia comments as an opportunity for jumping back into the discussion especially since the term falls under the umbrellas of psychology, and I ..."

Sam wrote: "In my last post I mentioned I was using Jean's multiphrenia comments as an opportunity for jumping back into the discussion especially since the term falls under the umbrellas of psychology, and I ..."Sam, this thesis by the same author may have the information you are looking for. There is a free download of the pdf. I had also come across this author a few months ago when I was reading The Mystery of Edwin Drood, but I didn't have time to look into Stolte's thesis.

https://open.library.ubc.ca/soa/cIRcl...

Youtube lecture about the book you referenced:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FvX16...

There are some truly excellent thoughts here, so once again I am torn between responding and incorporating then into further comments! Just a couple of notes then …

Paul - Thank you so much for working out the details regarding the bills, and explaining it so clearly. I had just noted the basic amount Mr Mantalini would get in the summary (as it’s all clear profit since he stole them!) but not worked out just how extortionate the average percentage rate was. And yes, if you remember we were told Ralph did check out the names on the bills, so knew they were “solid enough for Mrs Mantalini to have extended them credit in the first instance.” They were safe customers who would pay up.

Claudia - I too was disgusted at the idea of putting a child in a field to dig up and eat raw turnips etc. 😡

Shirley - Slicing open the abscess with an inky penknife, was a horrifyingly real episode which took place in a Yorkshire school, which Charles Dickens talks of in his preface.

Werner - I’m so pleased you have caught up and hope you can stay with us!

Paul - Thank you so much for working out the details regarding the bills, and explaining it so clearly. I had just noted the basic amount Mr Mantalini would get in the summary (as it’s all clear profit since he stole them!) but not worked out just how extortionate the average percentage rate was. And yes, if you remember we were told Ralph did check out the names on the bills, so knew they were “solid enough for Mrs Mantalini to have extended them credit in the first instance.” They were safe customers who would pay up.

Claudia - I too was disgusted at the idea of putting a child in a field to dig up and eat raw turnips etc. 😡

Shirley - Slicing open the abscess with an inky penknife, was a horrifyingly real episode which took place in a Yorkshire school, which Charles Dickens talks of in his preface.

Werner - I’m so pleased you have caught up and hope you can stay with us!

Sam - I was delighted at the mention of that book, Dickens and Victorian Psychology: Introspection, First-Person Narration, and the Mind by Tyson Stolte (spoiler follows, here just as strictly speaking it is off-topic)

(view spoiler)

I too “am finding Nicholas Nickleby full of thought provoking writing relating to psychology.”

It shows what a marvel Charles Dickens was, because Nicholas Nickleby is essentially an entertaining story (with a bit of social campaigning) about a huge number of people a young man meets and the adventures he has on his travels. The other aspect is the theatrical side, and unlike modern theatre, the actors of the time were not concerned with inhabiting a role, or exploring a character’s psychology. Victorian theatre was at root a spectacle, with elements such as song, dance, acts, magic and what we now think of circus entertainment. Actors were performers with stock characters, whose speech was declamatory and gestures were melodramatic.

We see these two aspects clearly, and have discussed them, but Charles Dickens is also exploring the psychology, as you say. We will look forward to hearing what Tyson Stolte has to say! Connie - Thank you for the link to a further article by Tyson Stolte.

Yes Charles Dickens was also extremely interested in philosophy, and explored Jeremy Bentham’s (and John Stuart Mills) ideas on utilitarianism and the concomitant economic system most profoundly later, in his novel Hard Times.

However we do see exponents of this earlier, as you say, and Ralph Nickleby’s ideas would fit very well into Dickens’s savage indictment of the new Poor Law of 1834, which we examined closely in our group read of Oliver Twist. This overlapping serial of Nicholas Nickleby, although intended (and contractually stipulated) to be entertaining and modelled on The Picwick Papers, is bound to pick up and reflect some concerns close to his heart.

(view spoiler)

I too “am finding Nicholas Nickleby full of thought provoking writing relating to psychology.”

It shows what a marvel Charles Dickens was, because Nicholas Nickleby is essentially an entertaining story (with a bit of social campaigning) about a huge number of people a young man meets and the adventures he has on his travels. The other aspect is the theatrical side, and unlike modern theatre, the actors of the time were not concerned with inhabiting a role, or exploring a character’s psychology. Victorian theatre was at root a spectacle, with elements such as song, dance, acts, magic and what we now think of circus entertainment. Actors were performers with stock characters, whose speech was declamatory and gestures were melodramatic.

We see these two aspects clearly, and have discussed them, but Charles Dickens is also exploring the psychology, as you say. We will look forward to hearing what Tyson Stolte has to say! Connie - Thank you for the link to a further article by Tyson Stolte.

Yes Charles Dickens was also extremely interested in philosophy, and explored Jeremy Bentham’s (and John Stuart Mills) ideas on utilitarianism and the concomitant economic system most profoundly later, in his novel Hard Times.

However we do see exponents of this earlier, as you say, and Ralph Nickleby’s ideas would fit very well into Dickens’s savage indictment of the new Poor Law of 1834, which we examined closely in our group read of Oliver Twist. This overlapping serial of Nicholas Nickleby, although intended (and contractually stipulated) to be entertaining and modelled on The Picwick Papers, is bound to pick up and reflect some concerns close to his heart.

Chapter 35: Smike becomes known to Mrs. Nickleby and Kate. Nicholas also meets with new Acquaintances. Brighter Days seem to dawn upon the Family

Smike is anxiously waiting for Nicholas in Noggs’s garret. Nicholas intends Smike to live with his family and thus makes plans to introduce him. He knows Kate will be kind, but is anxious that his mother might not welcome Smike, and hopes that in time she will be persuaded when she sees how devoted Smike is.

Smike is happy to see Nicholas, fearing he had met some trouble and was lost to him. Nicholas tells Smike he is taking him home, which scares Smike. He misunderstands for the moment, and thinks Nicholas has found a home for him—but that Nicholas means to part from him. Smike says that although he used to dream of having a home, he can’t now bear to be parted from Nicholas. The only parting which wouldn’t make him grieve, is if he were the one to depart, and it was the parting that comes with death.

“I shall never be an old man … In the churchyard we are all alike, but here there are none like me. I am a poor creature, but I know that.”

Nicholas treats him kindly and tells him: “I talk of mine—which is yours of course … I speak of the place where—in default of a better—those I love are gathered together”, and jokes that Smike must not look so dismal in from of the ladies, especially his sister. This makes Smike smile, and Nicholas leads him to Miss La Creevy’s house.

He introduces Smike to his family. Smike feels flustered around Nicholas’s pretty sister, who is gracious and kind to him when Nicholas introduces him as “the faithful friend and affectionate fellow-traveller whom I prepared you to receive”. Kate behaves so naturally that Smike soon feels comfortable. Miss La Creevy too welcomes him, and chats in such a friendly way that “Smike thought, within himself, she was the nicest lady he had ever seen; even nicer than Mrs. Grudden, of Mr. Vincent Crummles’s theatre.”

When Mrs. Nickleby comes in, Nicholas tells her that he knows she always want to be kind to the oppressed. She says that of course anyone who is Nicholas’s friend is always welcome. However, “looking very hard at her new friend, and bending to him with something more of majesty than the occasion seemed to require” Mrs Nickleby recalls that her husband used to bring people home when they had no food for them. She remarks to Kate that she doesn’t think they have room to take Nicholas’s friend in.

When Nicholas tells her his name, Mrs. Nickleby bursts into tears upon hearing it is “Smike”, because it sounds like Pyke.

“Mrs. Nickleby having fallen imperceptibly into one of her retrospective moods, improved in temper from that moment, and glided, by an easy change of the conversation occasionally, into various other anecdotes, no less remarkable for their strict application to the subject in hand.”

When Mrs Nickleby recovers, she asks Smike if he had ever dined with “the Grimbles of Grimble Hall”, a country estate somewhere in the North Riding of Yorkshire. Nicholas tells her that is a ridiculous question to ask of someone who is an outcast and used to be one of the boarders at a Yorkshire school. She argues that it is not so unlikely, because she used to sometimes be invited to dinners at a much more high-ranking family, when she was at school.

On the Monday morning, when everyone is getting along amicably, Nicholas starts to think about his livelihood. He considers going back to the Crummles, but he pictures his mother’s reaction to his being an actor. Besides, he doesn’t want to drag his family from town to town, forcing Kate in particular to have a limited social circle within the troupe.

He decides to go to the Register Office again. Everything seems exactly as it was before. He notices a gentleman also looking at the cards, who is dressed like a gentleman grazier, but in a very relaxed, easy style. Nicholas is drawn to him, because:

“what principally attracted the attention of Nicholas was the old gentleman’s eye,—never was such a clear, twinkling, honest, merry, happy eye, as that … with such a pleasant smile playing about his mouth, and such a comical expression of mingled slyness, simplicity, kind-heartedness, and good-humour, lighting up his jolly old face, that Nicholas would have been content to have stood there and looked at him until evening”.

The two cast sidelong glances at each other for quite a long time, and Nicholas apologises, embarrassed for being caught staring at the gentleman, but:

“Grafted upon the quaintness and oddity of his appearance, was something so indescribably engaging, and bespeaking so much worth, and there were so many little lights hovering about the corners of his mouth and eyes, that it was not a mere amusement, but a positive pleasure and delight to look at him.”

His appearance and demeanour make Nicholas almost forget that there was “such a thing as a soured mind or a crabbed countenance to be met with in the whole wide world.”

As the gentleman is walking away Nicholas remarks on all the fine opportunities which are advertised. The gentleman replies that many who are keen to be employed have also thought so, “Poor fellows!”

They both hesitate to speak, but the gentleman prompts Nicholas, and it turns out that both had doubted whether the other could be looking for a job. He is astonished to find that such a personable young gentleman is doing so, and ask how it happens that someone like Nicholas is looking for a job. Nicholas tells him that his father has died, and he has to support a widowed mother and his sister. At the man’s request, Nicholas gives his history—including the recent problems his sister Kate has had. He is surprised that he feels able to be so open with this stranger, but he finds his “kind face and manner … [and] the earnest and guileless” way he talks irresistible.

The gentleman insists on taking Nicholas on an omnibus, then walking through Bank and Threadneedle Street to a business called “The Cheeryble Brothers.” As they pass through its warehouse, Nicholas guesses from some packages lying about that the brothers Cheeryble are German merchants. It looks like a thriving business.

They go into an office where in a glass partition there is “a fat, elderly, large-faced clerk, with silver spectacles and a powdered head.” Nicholas has deduced from everyone’s manner that he is with a Mr. Charles Cheeryble, who calls the clerk “Tim”. He tells him kindly that he wants to consult his brother, Ned, and is told that he is talking to Mr. Trimmers. Mr Cheeryble is very pleased:

“Trimmers is one of the best friends we have. He makes a thousand cases known to us that we should never discover of ourselves.”

They are keen to benefit families in need, and Mr Trimmers has found a worthy case. Ned has promised £20, and Charles will add another £20, (pretending that £10 of it comes from Tim Linkinwater, so as not to look too ostentatious). After the business is concluded, Charles Cheeryble leads Nicholas into the inner room to meet his brother:

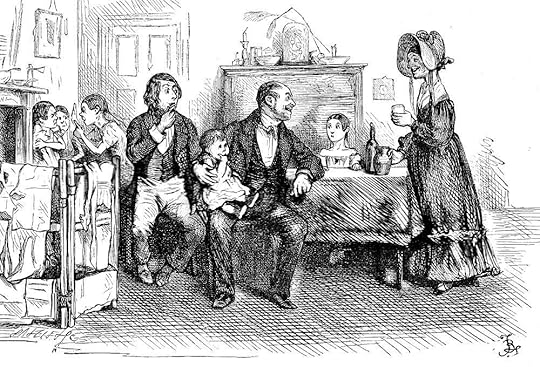

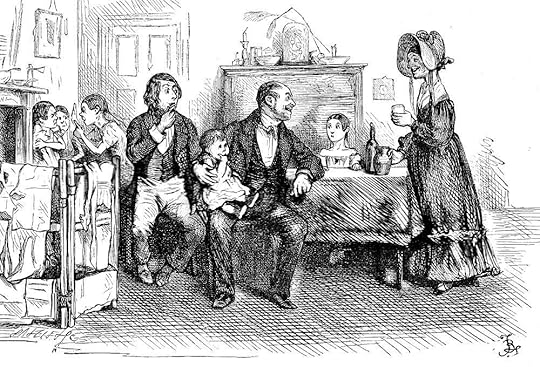

“The Cheerybles find a Solution to the Linkwinwater Problem” - Charles Stanley Reinhart - 1875

“What was the amazement of Nicholas when his conductor advanced, and exchanged a warm greeting with another old gentleman, the very type and model of himself—the same face, the same figure, the same coat, waistcoat, and neckcloth, the same breeches and gaiters—nay, there was the very same white hat hanging against the wall!”

“Cheeryble Brothers and Tim Linkinwater" - Sol Eytinge, Jr.

- 1867

There is no doubt in Nicholas’s mind that they are twin brothers, and he observes that:

“the face of each lighted up by beaming looks of affection, which would have been most delightful to behold in infants, and which, in men so old, was inexpressibly touching.”

They agree that they need to assist Nicholas, and plan to hire him to take some of the workload off an elderly employee, Tim Linkinwater. With tears in their eyes, the Cheeryble brothers remember the time when they were “two friendless lads, and earned our first shilling in this great city”.

Ned has a private chat with Tim Linkinwater, and in the meantime Nicholas sobs like a little child, as indeed he has not been able to help doing, ever since the two brothers had shown their kindness. When they come back Tim Linkinwater whispers to Nicholas that he will call upon him in the Strand that evening, at eight o’clock.

Tim Linkinwater does not begrudge him, but although he approves of them taking Nicholas on, the elderly employee refuses to take time off himself, saying that he has devoted himself to the business for forty-four years and intends to be there until he dies:

“’That’s what I’ve got to say, Mr. Edwin and Mr. Charles,’ said Tim, squaring his shoulders again. ‘This isn’t the first time you’ve talked about superannuating me; but, if you please, we’ll make it the last, and drop the subject for evermore.’”

“Tim Linkinwater’s Replacement Introduced” - Fred Barnard - 1875

After Tim Linkinwater has left the room, the Cheeryble brothers plan to make him a partner whether he likes it or not. As they say goodbye Nicholas tries to to pour out his thanks, overjoyed for being hired.

“And with any disjointed and unconnected words which would prevent Nicholas from pouring forth his thanks, the brothers hurried him out: shaking hands with him all the way, and affecting very unsuccessfully—they were poor hands at deception!—to be wholly unconscious of the feelings that completely mastered him.”

Nicholas’s salary is £120 a year. The Cheerybles also rent a cottage in Bow to Nicholas’s family, for a pittance, and loan them furniture (which they intend to eventually make gifts of.) Everyone works hard to make the house beautiful. Smike makes the garden “a perfect wonder to look upon”. Miss La Creevy tries to do repairs although she often injures herself. Mrs. Nickleby does a little, but talks constantly. Kate quietly occupies herself with the many household tasks.

“In short, the poor Nicklebys were social and happy; while the rich Nickleby was alone and miserable.”

Smike is anxiously waiting for Nicholas in Noggs’s garret. Nicholas intends Smike to live with his family and thus makes plans to introduce him. He knows Kate will be kind, but is anxious that his mother might not welcome Smike, and hopes that in time she will be persuaded when she sees how devoted Smike is.

Smike is happy to see Nicholas, fearing he had met some trouble and was lost to him. Nicholas tells Smike he is taking him home, which scares Smike. He misunderstands for the moment, and thinks Nicholas has found a home for him—but that Nicholas means to part from him. Smike says that although he used to dream of having a home, he can’t now bear to be parted from Nicholas. The only parting which wouldn’t make him grieve, is if he were the one to depart, and it was the parting that comes with death.

“I shall never be an old man … In the churchyard we are all alike, but here there are none like me. I am a poor creature, but I know that.”

Nicholas treats him kindly and tells him: “I talk of mine—which is yours of course … I speak of the place where—in default of a better—those I love are gathered together”, and jokes that Smike must not look so dismal in from of the ladies, especially his sister. This makes Smike smile, and Nicholas leads him to Miss La Creevy’s house.

He introduces Smike to his family. Smike feels flustered around Nicholas’s pretty sister, who is gracious and kind to him when Nicholas introduces him as “the faithful friend and affectionate fellow-traveller whom I prepared you to receive”. Kate behaves so naturally that Smike soon feels comfortable. Miss La Creevy too welcomes him, and chats in such a friendly way that “Smike thought, within himself, she was the nicest lady he had ever seen; even nicer than Mrs. Grudden, of Mr. Vincent Crummles’s theatre.”

When Mrs. Nickleby comes in, Nicholas tells her that he knows she always want to be kind to the oppressed. She says that of course anyone who is Nicholas’s friend is always welcome. However, “looking very hard at her new friend, and bending to him with something more of majesty than the occasion seemed to require” Mrs Nickleby recalls that her husband used to bring people home when they had no food for them. She remarks to Kate that she doesn’t think they have room to take Nicholas’s friend in.

When Nicholas tells her his name, Mrs. Nickleby bursts into tears upon hearing it is “Smike”, because it sounds like Pyke.

“Mrs. Nickleby having fallen imperceptibly into one of her retrospective moods, improved in temper from that moment, and glided, by an easy change of the conversation occasionally, into various other anecdotes, no less remarkable for their strict application to the subject in hand.”

When Mrs Nickleby recovers, she asks Smike if he had ever dined with “the Grimbles of Grimble Hall”, a country estate somewhere in the North Riding of Yorkshire. Nicholas tells her that is a ridiculous question to ask of someone who is an outcast and used to be one of the boarders at a Yorkshire school. She argues that it is not so unlikely, because she used to sometimes be invited to dinners at a much more high-ranking family, when she was at school.

On the Monday morning, when everyone is getting along amicably, Nicholas starts to think about his livelihood. He considers going back to the Crummles, but he pictures his mother’s reaction to his being an actor. Besides, he doesn’t want to drag his family from town to town, forcing Kate in particular to have a limited social circle within the troupe.

He decides to go to the Register Office again. Everything seems exactly as it was before. He notices a gentleman also looking at the cards, who is dressed like a gentleman grazier, but in a very relaxed, easy style. Nicholas is drawn to him, because:

“what principally attracted the attention of Nicholas was the old gentleman’s eye,—never was such a clear, twinkling, honest, merry, happy eye, as that … with such a pleasant smile playing about his mouth, and such a comical expression of mingled slyness, simplicity, kind-heartedness, and good-humour, lighting up his jolly old face, that Nicholas would have been content to have stood there and looked at him until evening”.

The two cast sidelong glances at each other for quite a long time, and Nicholas apologises, embarrassed for being caught staring at the gentleman, but:

“Grafted upon the quaintness and oddity of his appearance, was something so indescribably engaging, and bespeaking so much worth, and there were so many little lights hovering about the corners of his mouth and eyes, that it was not a mere amusement, but a positive pleasure and delight to look at him.”

His appearance and demeanour make Nicholas almost forget that there was “such a thing as a soured mind or a crabbed countenance to be met with in the whole wide world.”

As the gentleman is walking away Nicholas remarks on all the fine opportunities which are advertised. The gentleman replies that many who are keen to be employed have also thought so, “Poor fellows!”

They both hesitate to speak, but the gentleman prompts Nicholas, and it turns out that both had doubted whether the other could be looking for a job. He is astonished to find that such a personable young gentleman is doing so, and ask how it happens that someone like Nicholas is looking for a job. Nicholas tells him that his father has died, and he has to support a widowed mother and his sister. At the man’s request, Nicholas gives his history—including the recent problems his sister Kate has had. He is surprised that he feels able to be so open with this stranger, but he finds his “kind face and manner … [and] the earnest and guileless” way he talks irresistible.

The gentleman insists on taking Nicholas on an omnibus, then walking through Bank and Threadneedle Street to a business called “The Cheeryble Brothers.” As they pass through its warehouse, Nicholas guesses from some packages lying about that the brothers Cheeryble are German merchants. It looks like a thriving business.

They go into an office where in a glass partition there is “a fat, elderly, large-faced clerk, with silver spectacles and a powdered head.” Nicholas has deduced from everyone’s manner that he is with a Mr. Charles Cheeryble, who calls the clerk “Tim”. He tells him kindly that he wants to consult his brother, Ned, and is told that he is talking to Mr. Trimmers. Mr Cheeryble is very pleased:

“Trimmers is one of the best friends we have. He makes a thousand cases known to us that we should never discover of ourselves.”

They are keen to benefit families in need, and Mr Trimmers has found a worthy case. Ned has promised £20, and Charles will add another £20, (pretending that £10 of it comes from Tim Linkinwater, so as not to look too ostentatious). After the business is concluded, Charles Cheeryble leads Nicholas into the inner room to meet his brother:

“The Cheerybles find a Solution to the Linkwinwater Problem” - Charles Stanley Reinhart - 1875

“What was the amazement of Nicholas when his conductor advanced, and exchanged a warm greeting with another old gentleman, the very type and model of himself—the same face, the same figure, the same coat, waistcoat, and neckcloth, the same breeches and gaiters—nay, there was the very same white hat hanging against the wall!”

“Cheeryble Brothers and Tim Linkinwater" - Sol Eytinge, Jr.

- 1867

There is no doubt in Nicholas’s mind that they are twin brothers, and he observes that:

“the face of each lighted up by beaming looks of affection, which would have been most delightful to behold in infants, and which, in men so old, was inexpressibly touching.”

They agree that they need to assist Nicholas, and plan to hire him to take some of the workload off an elderly employee, Tim Linkinwater. With tears in their eyes, the Cheeryble brothers remember the time when they were “two friendless lads, and earned our first shilling in this great city”.

Ned has a private chat with Tim Linkinwater, and in the meantime Nicholas sobs like a little child, as indeed he has not been able to help doing, ever since the two brothers had shown their kindness. When they come back Tim Linkinwater whispers to Nicholas that he will call upon him in the Strand that evening, at eight o’clock.

Tim Linkinwater does not begrudge him, but although he approves of them taking Nicholas on, the elderly employee refuses to take time off himself, saying that he has devoted himself to the business for forty-four years and intends to be there until he dies:

“’That’s what I’ve got to say, Mr. Edwin and Mr. Charles,’ said Tim, squaring his shoulders again. ‘This isn’t the first time you’ve talked about superannuating me; but, if you please, we’ll make it the last, and drop the subject for evermore.’”

“Tim Linkinwater’s Replacement Introduced” - Fred Barnard - 1875

After Tim Linkinwater has left the room, the Cheeryble brothers plan to make him a partner whether he likes it or not. As they say goodbye Nicholas tries to to pour out his thanks, overjoyed for being hired.

“And with any disjointed and unconnected words which would prevent Nicholas from pouring forth his thanks, the brothers hurried him out: shaking hands with him all the way, and affecting very unsuccessfully—they were poor hands at deception!—to be wholly unconscious of the feelings that completely mastered him.”

Nicholas’s salary is £120 a year. The Cheerybles also rent a cottage in Bow to Nicholas’s family, for a pittance, and loan them furniture (which they intend to eventually make gifts of.) Everyone works hard to make the house beautiful. Smike makes the garden “a perfect wonder to look upon”. Miss La Creevy tries to do repairs although she often injures herself. Mrs. Nickleby does a little, but talks constantly. Kate quietly occupies herself with the many household tasks.

“In short, the poor Nicklebys were social and happy; while the rich Nickleby was alone and miserable.”

And a little more …

The Cheeryble Brothers

Charles Dickens mentions them in his preface, and you may remember that I put their originals’ names under a spoiler, in my post about Charles Dickens and Hablot Knight Browne touring the Midlands from 29th October to 7th November 1838. They briefly visited Manchester, and met the benefactors Daniel and William Grant, who lived in Ramsbottom, 14.7 miles from Manchester.

Nicholas assumes that the “Cheeryble, Brothers” proclaimed by the sign on their door-post are “German-merchants,” or immigrants (or immediate descendants of immigrants) who began to set up merchant houses in Manchester around 1820.

Here is a piece about Daniel and William Grant with no spoilers https://ramsbottomheritage.org.uk/dic...

The Cheeryble Brothers

Charles Dickens mentions them in his preface, and you may remember that I put their originals’ names under a spoiler, in my post about Charles Dickens and Hablot Knight Browne touring the Midlands from 29th October to 7th November 1838. They briefly visited Manchester, and met the benefactors Daniel and William Grant, who lived in Ramsbottom, 14.7 miles from Manchester.

Nicholas assumes that the “Cheeryble, Brothers” proclaimed by the sign on their door-post are “German-merchants,” or immigrants (or immediate descendants of immigrants) who began to set up merchant houses in Manchester around 1820.

Here is a piece about Daniel and William Grant with no spoilers https://ramsbottomheritage.org.uk/dic...

The Mantalinis and Marriage

I seem to enjoy the Mantalini passages more than most - largely because of Mr Mantalini’s inventive speeches. Have you noticed that they are “speeches” rather than dialogue? He always talk of his wife in the third person, even though he is talking directly to her and others are merely witnesses to - or audiences for - their drama and their dramatic threats of suicide.

For it is a drama. Yesterday I write a post about how they validate each other. Mrs Mantalini, although nominally the boss of her dressmaking business (now a fallen empire) is completely motivated, manipulated and controlled by her husband. He gives her an ego she otherwise would not have. Their “love-making” consists of pushing the other towards suicide i.e. extreme coercive manipulation.

They both threaten suicide, and these exaggerated roles are a substitute for a vacuum. It draws them back together because the loss of one partner would expose how empty their lives are.

All the marriages in Nicholas Nickleby (at least so far) are depicted as systems of manipulation and annoyance. They are all flawed in some fundamental but different way, and the Mantalinis is a perfect example of an unusual type. We have seen some already, and can come back to this topic later if you like, with different examples.

I seem to enjoy the Mantalini passages more than most - largely because of Mr Mantalini’s inventive speeches. Have you noticed that they are “speeches” rather than dialogue? He always talk of his wife in the third person, even though he is talking directly to her and others are merely witnesses to - or audiences for - their drama and their dramatic threats of suicide.

For it is a drama. Yesterday I write a post about how they validate each other. Mrs Mantalini, although nominally the boss of her dressmaking business (now a fallen empire) is completely motivated, manipulated and controlled by her husband. He gives her an ego she otherwise would not have. Their “love-making” consists of pushing the other towards suicide i.e. extreme coercive manipulation.

They both threaten suicide, and these exaggerated roles are a substitute for a vacuum. It draws them back together because the loss of one partner would expose how empty their lives are.

All the marriages in Nicholas Nickleby (at least so far) are depicted as systems of manipulation and annoyance. They are all flawed in some fundamental but different way, and the Mantalinis is a perfect example of an unusual type. We have seen some already, and can come back to this topic later if you like, with different examples.

A Change of Theme at the Midpoint

As Lori remarked, and several others may have ben thinking: “It is almost unbearable for a long chapter filled with characters that just make us cringe”. Charles Dickens evidently knew this, and we have a counterbalance today.

Whether you enjoyed the Mantalini episodes or not, I hope that like me you had a big smile on your face by the end of this chapter. The Cheeryble brothers are two of my favourite characters ever 🥰, and are introduced at exactly the right time. We know they must be important, not cameos, as he devotes so much time and care to the delightfully whimsical description of Nicholas’s first sight of Charles Cheeryble outside the dreary Employment office.

As Lori remarked, and several others may have ben thinking: “It is almost unbearable for a long chapter filled with characters that just make us cringe”. Charles Dickens evidently knew this, and we have a counterbalance today.

Whether you enjoyed the Mantalini episodes or not, I hope that like me you had a big smile on your face by the end of this chapter. The Cheeryble brothers are two of my favourite characters ever 🥰, and are introduced at exactly the right time. We know they must be important, not cameos, as he devotes so much time and care to the delightfully whimsical description of Nicholas’s first sight of Charles Cheeryble outside the dreary Employment office.

Conflicts and Reversals at the Midpoint

We have been aware of Nicholas and his uncle at loggerheads all the way through. They disliked each other when they first met. Some critics think of theirs as an Oedipal relationship. That's also a great comparison with the Biblical story of Cain and Abel Shirley, and one which all Charles Dickens’s readers would be familiar with.