Dickensians! discussion

This topic is about

Oliver Twist

Oliver Twist - Group Read 5

>

Oliver Twist: Chapters 44 - 53

message 152:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 23, 2023 09:21AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Jacobs Island and Folly Ditch

Jacob’s Island had been a thriving area, with most people employed in the timber industry and shipbuilding. But when that industry moved downriver, closing a local water mill, the population sank into poverty. A lead mill took over from the water mill in the 1830s, quickly adding its poisons to the waste-filled Folly Ditch, which supplied the inhabitants’ water.

I wrote a long piece about this area of London here https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/...

with illustrations from the time (as it no longer exists). It is also now safe to google, as we have read the highly dramatic part which pertains to it.

So this long opening passage is intended as social criticism. We can tell Charles Dickens’s previous experience of factual writing and journalism here. Then with increasing momentum, he moves, through a brief but tense comic scene, to the end of the chapter which is a highly charged and intensely dramatic death. The filthy, rotting structures and appalling conditions described here at the start set the scene. The poor have to live in highly dangerous conditions. We see this as another of Fagin’s lairs or "kens", where the gang members meet; a ruined decrepit house on Jacob’s Island in Southwark on the south shore of the industrially polluted Thames.

Jacob’s Island had been a thriving area, with most people employed in the timber industry and shipbuilding. But when that industry moved downriver, closing a local water mill, the population sank into poverty. A lead mill took over from the water mill in the 1830s, quickly adding its poisons to the waste-filled Folly Ditch, which supplied the inhabitants’ water.

I wrote a long piece about this area of London here https://www.goodreads.com/topic/show/...

with illustrations from the time (as it no longer exists). It is also now safe to google, as we have read the highly dramatic part which pertains to it.

So this long opening passage is intended as social criticism. We can tell Charles Dickens’s previous experience of factual writing and journalism here. Then with increasing momentum, he moves, through a brief but tense comic scene, to the end of the chapter which is a highly charged and intensely dramatic death. The filthy, rotting structures and appalling conditions described here at the start set the scene. The poor have to live in highly dangerous conditions. We see this as another of Fagin’s lairs or "kens", where the gang members meet; a ruined decrepit house on Jacob’s Island in Southwark on the south shore of the industrially polluted Thames.

message 153:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 23, 2023 08:33AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

As the original readers waited a month until the next installment, we will have one day free, and will read chapter 51 which comprises the whole of installment 23, on Tuesday.

Your thoughts? I think we may know who the gentleman offering the 50 guineas was - and the man on horseback!

Your thoughts? I think we may know who the gentleman offering the 50 guineas was - and the man on horseback!

I have been listening to a complimentary Great Courses series, via Audible membership, covering Victorian Britain. The lecturer talked about Jacob's Island. The professor quotes from Henry Mayhew, that chronicler of London's underclass and friend of Dickens, as he described Jacob's Island as the "Capital of Cholera" and the place was filled with "the stench of death".

I have been listening to a complimentary Great Courses series, via Audible membership, covering Victorian Britain. The lecturer talked about Jacob's Island. The professor quotes from Henry Mayhew, that chronicler of London's underclass and friend of Dickens, as he described Jacob's Island as the "Capital of Cholera" and the place was filled with "the stench of death". The ditch Ms. Bionic mentions was a brook converted to a tidal open sewer during the reign of Henry II. The island was spared from the 1666 Great Fire of London. It was an area of Central London that retained a claustrophobic Medieval atmosphere.

As Ms. Bionic mentions, we have a man on horseback offers £20 to anyone who can get a ladder and old gentleman offers 50 guineas to anyone who captures Sikes alive.

We have this from the end of the Chapter 49:

“I will give fifty more,” said Mr. Brownlow, “and proclaim it with my own lips upon the spot, if I can reach it. Where is Mr. Maylie?”

“Harry? As soon as he had seen your friend here, safe in a coach with you, he hurried off to where he heard this,” replied the doctor, “and mounting his horse sallied forth to join the first party at some place in the outskirts agreed upon between them.”

Why would Dickens not specifically mention Harry and Mr. Brownlow? It does keep with the atmosphere Dickens creates of a nameless mob; the mob itself has become an individual character.

This is the 2nd scene from the novel of a mob of people pursuing a charged criminal. The Metropolitan Police was a new organization so residents of London were keeping the tradition of one of their duties was to pursue and capture criminals. I would also imagine there is the raw excitement of participating in an thrilling activity tinged with danger.

I have been quiet the past few, busy with summer and catching up on a lot of reading plus I have wanted to save you from falling into the distracting rabbit holes, I have while reading this book. But we are running out of time and comment I must. Thanks Michael for the reference on Jane Eyre earlier. I found that very interesting. I agree with your assessment and wish to build on it.

I have been quiet the past few, busy with summer and catching up on a lot of reading plus I have wanted to save you from falling into the distracting rabbit holes, I have while reading this book. But we are running out of time and comment I must. Thanks Michael for the reference on Jane Eyre earlier. I found that very interesting. I agree with your assessment and wish to build on it. Like Sara and others, pointing out quality of Dickens's prose and elements that first appearing here became part his definitive style. I have been most interested in the prose and this chapter illustrates several of these striking elements as brought to our attention by Michael. I hope you have also noted Dickens' superb descriptions in the introductory paragraphs of this chapter and I urge you to voice them aloud for full effect of how Dickens is using sound and sense, using consonance and alliteration on several levels, for atmosphere, for emphasis, for verbal illustration, and more to give us a complete picture which stimulates all our senses and dictates how we are supposed to respond to what is described.

Further, note how this style of prosodic description changes as the gang members enter the scene and interact, and then returns i part as Dickens describes that outside mob. I repeat one has to voice the prose to appreciate what Dickens is doing.

message 156:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 23, 2023 08:41AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Michael wrote: "Why would Dickens not specifically mention Harry and Mr. Brownlow? It does keep with the atmosphere Dickens creates of a nameless mob ..."

Nice!

Henry Mayhew was an exact contemporary - the same age - and friend (as you say Michael) of Charles Dickens. They influence each other in several ways, even at the very early age of 25, including reading each other's writings, acting in the same plays together, and through writing in "Bentley's miscellany".

Henry Mayhew was later to go on to write the definitive text of London Labour and the London Poor in 1861.

I wonder if the mob scene here reminded anyone of how Oliver was pursued by an angry mob. That acted as a kind of foreshadowing, in that we could then predict that the social conditions showed the likelihood of there being an enraged mob for anything which caught the public's attention as being unjust. It also prefigures much later novels of his such as A Tale of Two Cities. When he and Elizabeth Gaskell were writing similar novels about industrial social conditions, he actually asked her not to write her very powerful scene in North and South, and we have to wonder whether this was because it would detract from his own novel Hard Times, which was not as comprehensive about the angry mob of (view spoiler).

Nice!

Henry Mayhew was an exact contemporary - the same age - and friend (as you say Michael) of Charles Dickens. They influence each other in several ways, even at the very early age of 25, including reading each other's writings, acting in the same plays together, and through writing in "Bentley's miscellany".

Henry Mayhew was later to go on to write the definitive text of London Labour and the London Poor in 1861.

I wonder if the mob scene here reminded anyone of how Oliver was pursued by an angry mob. That acted as a kind of foreshadowing, in that we could then predict that the social conditions showed the likelihood of there being an enraged mob for anything which caught the public's attention as being unjust. It also prefigures much later novels of his such as A Tale of Two Cities. When he and Elizabeth Gaskell were writing similar novels about industrial social conditions, he actually asked her not to write her very powerful scene in North and South, and we have to wonder whether this was because it would detract from his own novel Hard Times, which was not as comprehensive about the angry mob of (view spoiler).

message 157:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 23, 2023 07:21AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Sam wrote: "one has to voice the prose to appreciate what Dickens is doing ..."

Hi Sam - great observation! This is all part of how Charles Dickens himself wrote, speaking and acting out the parts - sometimes in front of a mirror. His readings, even of the prose passages, (not just "Sikes and Nancy", or "Sikes's Flight", which he scripted as I described earlier) must have been incredibly dramatic to experience.

I'm so pleased you are back with us again, Sam. Your comments are always interesting. Do feel free to add some to the previous discussion thread too, if you like. In fact we have talked quite a lot about about the writing style (sometimes I title them thus) .

I am hoping that others too return, especially those who have not contributed to the later threads. I had expected that we might speed up our reading towards the end, but actually the writing is even more worth observing in this final installment! Who else but Charles Dickens could have moved from the ghastly diatribe against Folly Ditch, (do please read the earlier information post I linked to, both Michael and Sam!) through a tense but comic scene, to the end tragedy of almost Shakespearean proportions, all in one chapter, and so smoothly! He has us in the palm of his hand.

Hi Sam - great observation! This is all part of how Charles Dickens himself wrote, speaking and acting out the parts - sometimes in front of a mirror. His readings, even of the prose passages, (not just "Sikes and Nancy", or "Sikes's Flight", which he scripted as I described earlier) must have been incredibly dramatic to experience.

I'm so pleased you are back with us again, Sam. Your comments are always interesting. Do feel free to add some to the previous discussion thread too, if you like. In fact we have talked quite a lot about about the writing style (sometimes I title them thus) .

I am hoping that others too return, especially those who have not contributed to the later threads. I had expected that we might speed up our reading towards the end, but actually the writing is even more worth observing in this final installment! Who else but Charles Dickens could have moved from the ghastly diatribe against Folly Ditch, (do please read the earlier information post I linked to, both Michael and Sam!) through a tense but comic scene, to the end tragedy of almost Shakespearean proportions, all in one chapter, and so smoothly! He has us in the palm of his hand.

It is a masterful end.

It is a masterful end. The nameless mob is seen much later in A Tale of Two Cities indeed Jean, and it mirrors the angry mob that was after Oliver.

But as Michael put it, we see here how those whom we know very well are suddenly unnamed: the horseman and the old gentleman, and even "a dog". Perhaps Dickens invites us to step back outside the frame, outside the tale, and become like all others onlookers who watch the scene and of course do not know who is who.

This makes things appear in slow motion, even if indeed everything is happening within a few seconds (Bill's terrible end and his dog's fatal fall).

I agree with Sam that all these chapters have to be reread - possibly aloud too - to fully appreciate all the details within the text. Dickens at his best, and very promising for the future.

I observed, as Sam says, that the tempo and use of the language builds itself into a crescendo. When read aloud, the feeling is somewhat like being swept down a river, with the mob pushing on every side. In such a mob, even a very familiar face would be lost, so the absence of individual names is a kind of reinforcement. This chapter, seems to me, to be given over almost entirely to movement and action. That makes the silence and waiting of the criminals before Sikes arrives and when he is cowering in the corner even more acute. The juxtaposition is masterful. It is hard to remember that this is a very young Dickens writing here.

I observed, as Sam says, that the tempo and use of the language builds itself into a crescendo. When read aloud, the feeling is somewhat like being swept down a river, with the mob pushing on every side. In such a mob, even a very familiar face would be lost, so the absence of individual names is a kind of reinforcement. This chapter, seems to me, to be given over almost entirely to movement and action. That makes the silence and waiting of the criminals before Sikes arrives and when he is cowering in the corner even more acute. The juxtaposition is masterful. It is hard to remember that this is a very young Dickens writing here.How appropriate that Bill Sikes is sent to justice by the haunting of Nancy, whether real or imagined. It is his own guilt that sentences him to death, not man but God who metes out the justice.

"with what measure ye mete, it shall be measured to you again" Matthew 7:2

Now to see if we are allowed to watch Fagin get his due or if we are meant to assume that Crackit has it right.

Bionic Jean wrote: "“from the Middlesex to the Surrey shore”

Bionic Jean wrote: "“from the Middlesex to the Surrey shore”is an old way to describe crossing the river Thames from the North to the South side. London Bridge connects an area which use to be in Middlesex to the su..."

As a Christian and a lover of history, I have been captivated by your notes here, Bionic Jean. In case anyone missed your link to Southwark Cathedral, here it is again. (I am in the process of catching up on the fascinating discussion and everyone's comments)!

https://cathedral.southwark.anglican....

Sikes's demise is reminiscent of The Telltale Heart; he is driven to madness and self-destruction, unable to escape the horrors he himself created. A grisly but highly appropriate end to Sikes's career.

Sikes's demise is reminiscent of The Telltale Heart; he is driven to madness and self-destruction, unable to escape the horrors he himself created. A grisly but highly appropriate end to Sikes's career.I think Dickens, disturbed by the widespread unfairness and misery of the society in which he lived, longed for a world where justice prevailed; he must have taken grim satisfaction in appointing himself judge, jury and executioner of Sikes.

Sara wrote: "When I am reading Dickens, I always feel as if I am in London, physically there. The details are so precise and I can imagine how it would have felt reading this if you were a Londoner and familiar..."

Sara wrote: "When I am reading Dickens, I always feel as if I am in London, physically there. The details are so precise and I can imagine how it would have felt reading this if you were a Londoner and familiar..."Yes, absolutely, Sara! I feel the same way.

Sam wrote: "I urge you to voice them aloud for full effect of how Dickens is using sound and sense,"

Sam wrote: "I urge you to voice them aloud for full effect of how Dickens is using sound and sense,"What a great observation. You were reading the text aloud as someone living at time of publication would have done. I wish I could fine the reference but quiet reading as we do it only developed during the Nineteenth Century.

One reason for the difference was reading back then was a much more communal activity; a form of family entertainment. There was a wonderful show I found on YouTube about Charles Dickens and "Great Expectations". A historian described how friends and families would gather together to read aloud the latest serial installment; Victorian version of viewing parties for a new episode of say "Game of Thrones".

Perhaps another reason for reading aloud was poetry was still at least equal and maybe still considered superior to prose. Reading aloud was best way to appreciate the rhythms and rhymes of the text.

Moreover books were still expensive, not everyone could afford to buy them. They relied upon the publication of installments in magazines that were anyway an expense. Last but not least, people back then were far less individualistic than we mostly are. Sharing with others by reading aloud, or singing, or playing the piano was the only opportunity for them to be accomplished, well read, connoisseur of music.

Moreover books were still expensive, not everyone could afford to buy them. They relied upon the publication of installments in magazines that were anyway an expense. Last but not least, people back then were far less individualistic than we mostly are. Sharing with others by reading aloud, or singing, or playing the piano was the only opportunity for them to be accomplished, well read, connoisseur of music.

message 165:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 24, 2023 03:58AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Michael wrote: "reading back then was a much more communal activity; a form of family entertainment ..."

This is true, for several reasons. His fans came from all social strata, and included both those who were illiterate and Queen Victoria! I think I've said before that people would pay a penny for someone to read the latest installment of his serial to them, and there were performances in the streets, as well as Charles Dickens's own readings of course. He read at home to his family and friends, as well as the readings he did in several countries, which invariably sold out very quickly.

Charles Dickens would insist that the first two rows or so for his readings were kept for those who could not pay - or could only pay a little. Many of his greatest admirers could not read, but knew his works just as well as those who could.

Not everyone could read, so they would learn passages off by heart. Lighting was a luxury, so the designated reader of a family would have the candle near them! Telling and reading stories was one of their best entertainments, especially for those who could not afford musical instruments.

But for the burgeoning middle class families of the early 19th century, there was a strong tradition of having a session of reading around the fire. One person would be the reader. So Charles Dickens's story would be first accessed by the whole family, who would share their reactions.

These are the reasons why the most emotionally powerful scenes sometimes read like melodrama to us. Even though Charles Dickens made his own personal "reading copies" for Oliver Twist and his later novels (as I described a few days ago, like scripts with stage directions) - this was partly to aid the street performances of his works by his reading public, or the readings out loud.

This is true, for several reasons. His fans came from all social strata, and included both those who were illiterate and Queen Victoria! I think I've said before that people would pay a penny for someone to read the latest installment of his serial to them, and there were performances in the streets, as well as Charles Dickens's own readings of course. He read at home to his family and friends, as well as the readings he did in several countries, which invariably sold out very quickly.

Charles Dickens would insist that the first two rows or so for his readings were kept for those who could not pay - or could only pay a little. Many of his greatest admirers could not read, but knew his works just as well as those who could.

Not everyone could read, so they would learn passages off by heart. Lighting was a luxury, so the designated reader of a family would have the candle near them! Telling and reading stories was one of their best entertainments, especially for those who could not afford musical instruments.

But for the burgeoning middle class families of the early 19th century, there was a strong tradition of having a session of reading around the fire. One person would be the reader. So Charles Dickens's story would be first accessed by the whole family, who would share their reactions.

These are the reasons why the most emotionally powerful scenes sometimes read like melodrama to us. Even though Charles Dickens made his own personal "reading copies" for Oliver Twist and his later novels (as I described a few days ago, like scripts with stage directions) - this was partly to aid the street performances of his works by his reading public, or the readings out loud.

message 166:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 23, 2023 03:49PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

So back to Bill Sikes ...

Jim - I like this comparison very much. The Tell-Tale Heart was first published in 1843; just 5 years later. The previous year, Edgar Allan Poe had met Charles Dickens in Philadelphia (when he was on his first tour of the States) and they both admired each other's work.

So the two episodes are remarkably close together in time - and yet again, Charles Dickens's came first.

Jim - I like this comparison very much. The Tell-Tale Heart was first published in 1843; just 5 years later. The previous year, Edgar Allan Poe had met Charles Dickens in Philadelphia (when he was on his first tour of the States) and they both admired each other's work.

So the two episodes are remarkably close together in time - and yet again, Charles Dickens's came first.

I had to applaud Charley Bates for being brave enough to attack Sikes. The boy put himself in grave danger by this action but kept at it. I hope someone remember to get him out of the closet.

I had to applaud Charley Bates for being brave enough to attack Sikes. The boy put himself in grave danger by this action but kept at it. I hope someone remember to get him out of the closet. This was a tense and action-filled chapter. The crowds being everywhere made the scene feel very claustrophobic. I'm sure Sikes felt as trapped as we did. There was no getting away from the mob.

Poor Bull's Eye. Despite being an aggressive dog, I had hoped for a better end for him. But perhaps this was a fitting end for a dog who had no options. It's so sad that Bill caused Bull's Eye death, too, by making him so aggressive and untrusting. Poor dog.

Michael wrote: "Nancy holding up the handkerchief pleading for divine mercy and forgiveness has to be one of the greatest scenes in Victorian literature."

Michael wrote: "Nancy holding up the handkerchief pleading for divine mercy and forgiveness has to be one of the greatest scenes in Victorian literature."Michael, you have raised this fatal scene from "melodrama" to religious passion - an actual passion play. Nancy is the redeemed, as Dickens invokes the last passion of Christ through her trial, suffering and death.

Just as Christ uttered in His last moments "Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing", Nancy also shows she desires mercy for Sikes even at the end when she begs him not to kill her.

"Let me see them again, and beg them on my knees to show the same mercy and goodness to you . . . It is never too late to repent."

And then she dies.

Bionic Jean wrote: "During his final tour the doctors and his friends begged him to stop, for the sake of his health, but Charles Dickens was adamant - and driven.."

Bionic Jean wrote: "During his final tour the doctors and his friends begged him to stop, for the sake of his health, but Charles Dickens was adamant - and driven.."Your summary was devastating, Jean. I didn't realize until reading your notes and then re-reading "Fatal Consequences" the true emotional impact upon Charles Dickens of Nancy's murder. In a speculative psychological interpretation, Dickens himself was the murderer [Sikes] as he created the scene.

In a sense, the fact that he could "re-live" the parts he imagined by acting them out was a curse to him, or at least he paid a heavy price for his acting talent. It seems to me he couldn't escape his created fictional characters even decades after a novel was written.

A new character in the last few chapters. Only Dickens can make that work.

A new character in the last few chapters. Only Dickens can make that work. I loved how he ratcheted up the suspense with the crowd. It makes me look forward to reading Tale of Two Cities because I can on,y imagine how much more intense it will be.

Everyone’s comments are so spot on. Now, we wait for the fate of Fagin. And where has Oliver been, lately. It’s been quite a few chapters since he’s been in the limelight. Fagin’s gang is almost no more and Oliver seems as if he is going to escape a life of crime.

Shirley (stampartiste) wrote: "Michael wrote: "Dickens delivers, one of his famous spiderweb of connections between many of the characters. Was this the first one? ..."

Shirley (stampartiste) wrote: "Michael wrote: "Dickens delivers, one of his famous spiderweb of connections between many of the characters. Was this the first one? ..."I love everything you said, Michael, and the points you ma..."

I too felt a need to totally concentrate and even re-read paragraphs to follow the complicated dissection of each of the characters' family history. In fact, this was irritating to me as it interrupted the smooth flow of the action that had proceeded it.

I hope my membership in Dickensians doesn't implode with this criticism of Dickens. I found he did the exact same thing at the end of The Old Curiosity Shop I didn't like it there, either!

Bionic Jean wrote: "Phew! No wonder Monks complained that it was a long tale!" And Dickens answers this himself. . .

Bionic Jean wrote: "Phew! No wonder Monks complained that it was a long tale!" And Dickens answers this himself. . . "'Your tale is of the longest,' observed Monks, moving restlessly in his chair.

'It is a true tale of grief, and trial, and sorrow, young man,' returned Mr. Brownlow, 'and such tales usually are; if it were one of unmixed joy and happiness, it would be very brief.'"

Aha! Dickens anticipated our complaints. What else did we expect from a story so complex and replete with the best and worst life has to offer?

Michael wrote: "Sam wrote: "I urge you to voice them aloud for full effect of how Dickens is using sound and sense,"

Michael wrote: "Sam wrote: "I urge you to voice them aloud for full effect of how Dickens is using sound and sense,"What a great observation. You were reading the text aloud as someone living at time of publicat..."

Yes! The reading aloud is so important and I am grateful for Sam's encouragement to do this today. Reading aloud was how I was introduced to Dickens by my father. In the evening, my mother, sister and myself gathered around his chair as he read -- mostly I remember Charles Dickens but also Robert Louis Stevenson, who apparently was greatly influenced by Charles Dickens. Dickens words come alive when read aloud - I remember!

Trying to squeeze out a few more thoughts before Jean's next post. My main thought is the theme of betrayal in Oliver Twist but I have a few digressions before I get there.

Trying to squeeze out a few more thoughts before Jean's next post. My main thought is the theme of betrayal in Oliver Twist but I have a few digressions before I get there.First on Bill and Nancy. Nancy IMO, is the first of the villains and even in the novel that Dickens' rounds out as a character and we noted this in our discussion earlier. But Nancy is matched with Bill Sykes and it is a toss whether he or Fagin are of most importance next. I am going to argue a bit for Bill. Having seen Sykes as a most frightening character on my first read, I was looking for redeeming qualities this time in. Dickens shows us his strength, his high reputation among the baddies, his animal power, and we certainly see his unpredictability, his tendency to lash out and his meanness.

There is a bit of "Mr. Hyde," or the "Hairy Ape," quality to Sykes. For a bit, I thought Dickens might be making a statement regarding evolution with him since the topic was in discussion before Darwin's publication. But I also noticed that Sykes had vulnerabilities and limitations. His reactions were mostly "fight or flight" reactions, which are indicative of earlier physical or psychological trauma. He was also must likely to react when he was confused and frustrated, and it brought to mind my similar encounters with individuals suffering from post-traumatic stress and ADHD, and even autism. I am not diagnosing Sykes, but I think his behavior has roots that are beyond a simple definition of evil. If we were to view Sykes as more human and less monster, his relationship with Nancy becomes less negative and more sympathetic. And thought they may not be the best example of a happy couple, if we could see them as a loving couple, their story becomes more tragic. I will leave this now, but I see a lot of Othello in Nancy and Bill and a lot of Iago in Fagin.

The variations on the saying, "Give him enough rope and he'll hang himself," comes to mind in Sykes end. Think Dickens was intending irony? It is echoed a bit with Bulls-eye.

The opening paragraph of chapter 50 use a lot of sibilants and cluster consonants, especially those that have a sibilant like "st," to describe the negative qualities of Jacob's Ditch. I have a weak background in linguistics or phonology. Anyone have a thought on why Dickens emphasized those sounds or what he may have intended. Also note that in reading those passages aloud, one has to slow down to articulate, since one's mouth is adjusting dramatically to form the next sound. Thomas Hardy used this approach in poetry and prose and it definitely gives the mouth some exercise.

Dickens really explores the various forms of betrayal in Oliver Twist as if he were Beethoven playing with a musical motif. There are betrayals, implied betrayals, hidden betrayals, double betrayals, suspected betrayals, accused betrayals. If we are to stretch the definition to include unintentional betrayals (as in the case of a mother dying at the birth of a child) the list is even longer. It is the theme that most occupies my thoughts at this point in the book. Again, I throw it to anyone for comment. What do you think Dickens is saying on this?

message 176:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 25, 2023 06:36AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Lots to think about from these recent comments, particularly the Shakespearean references and psychology of Bill Sikes Sam has just brought out. Thank you all! Let's come back to these today - and tomorrow too - when we have time before the final thrust in the concluding 2 chapters.

Moving on now to today's ...

Moving on now to today's ...

message 177:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 25, 2023 06:57AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Installment 23

Chapter 51:

“Affording an Explanation of More Mysteries Than One …”

Just two days later, Oliver is in a carriage with Mrs. Maylie, Rose, Mrs. Bedwin, and Dr. Losberne. Mr. Brownlow, and a sixth person follow on in a post chaise. All of them are travelling fast to the town where Oliver was born; all are feeling the suspense of bringing the mystery to a conclusion. Oliver is quiet, but then sees the baby farm where he and his dear friend Dick grew up. He points it out excitedly to Rose, who agrees that they can take Dick away from there, so that he can grow strong and well.

Oliver has such a mixture of feelings as he recognises all the places he knows. When they pass Sowerberry’s, he thinks that it seems to be “smaller and less imposing in appearance than he remembered it.” The same seems to be true of Gamfield’s cart, the workhouse, and the town’s chief hotel. To Oliver, each place seems smaller than he remembered.

To Oliver’s surprise, they arrive at the the best hotel in town, where Mr. Grimwig is waiting to greet them. He too is very changed; affable and full of smiles as he kisses the ladies.

Mysterious things are happening, with a number of secret meetings between the men of the group. Once Mrs. Maylie was called away for an hour, and shows signs of weeping when she returns. Neither Rose or Oliver are included in the meetings and both are perplexed as to what is happening. But when it gets to 9 o’clock, all four men return, and Oliver is astonished to be told that the stranger with them, whom he recognises from before, is his brother, although:

“Monks cast a look of hate, which, even then, he could not dissemble, at the astonished boy”.

Mr. Brownlow assembles some papers he wants Monks to sign, and recaps:

“This child … is your half-brother; the illegitimate son of your father, my dear friend Edwin Leeford, by poor young Agnes Fleming, who died in giving him birth.”

Monks refers sullenly to the boy as a “bastard”, and on being reprimanded, takes up the story himself. He tells again, for those assembled, how Oliver’s father had been taken ill in Rome, and joined by his mother and himself, travelling from Paris. The next day Oliver’s father had died, his senses having gone, leaving two papers:

“enclosed in a few short lines to you, [Mr. Brownlow] with an intimation on the cover of the package that it was not to be forwarded till after he was dead. One of these papers was a letter to this girl Agnes; the other a will.”

Oliver’s father [Leeford]’s letter to Agnes was a “penitent confession” asking for her forgiveness. He had promised to marry her, saying that they must wait because there was a secret mystery, which he would explain one day. ”She trusted too far, and lost what none could ever give her back.“ A few months before the baby was due, he begged Agnes not to curse his memory, or: ”think the consequences of their sin would be visited on her or their young child; for all the guilt was his.” Tears are now streaming down Oliver’s face, as he hears Monks tell how his father had asked his mother to wear the locket and ring he had given her.

Mr. Brownlow prompts Monks about the will, but continues himself, as Monks is silent. He describes how miserable Oliver’s father’s wife had made him, and describes Monks as a boy with a: “rebellious disposition, vice, malice, and premature bad passions … who had been trained to hate him”.

The will stipulated £800 pounds should be given each to his wife and her son, Edward [Monks], and left the rest of his fortune to be divided between Agnes and her unborn child. If it was a daughter there were no conditions, but if it was to be a son, the inheritance was conditional on him reaching adulthood without engaging in any criminal acts.

“He did this, he said, to mark his confidence in the mother, and his conviction—only strengthened by approaching death—that the child would share her gentle heart, and noble nature.”

Monks now comes in loudly to defend his own mother, saying that she burnt the will, and secretly held back the letter and other proofs as security. He tells how Agnes’s father got the truth out of her, and fled to Wales with his family, full of shame and dishonour. He even changed his name. Agnes had run away before he fled, and her father searched for her unsuccesfully, and then died soon after:

“it was on the night when he returned home, assured that she had destroyed herself, to hide her shame and his, that his old heart broke.”

Mr. Brownlow continues, telling how at 18 years of age, Monks had stolen his mother’s money and jewels, and “gambled, squandered, forged, and fled to London: where for two years he had associated with the lowest outcasts.” Monks’s mother had told him this herself personally, when old and ill, and “sinking under a painful and incurable disease”. She had hoped to see her son before she died. Eventually Monks was found, and reconciled, they returned to France together.

His mother reaffirmed the bitterness and hatred she felt towards the young woman [Agnes] and encouraged Monks to share it. His mother told him that she believed the young woman had borne a son, whereupon Monks said he:

“swore to her, if ever it crossed my path, to hunt it down; never to let it rest; to pursue it with the bitterest and most unrelenting animosity; to vent upon it the hatred that I deeply felt, and to spit upon the empty vaunt of that insulting will by dragging it, if I could, to the very gallows-foot.”

Mr. Brownlow adds that “the Jew” [Fagin] had been offered a reward for keeping Oliver and turning him into a criminal, but that he would have forfeited some of the money if Oliver had escaped. Monks also confesses to buying the ring and locket from “the man and woman I told you of, [the Bumbles] who stole them from the nurse [Old Sally], who stole them from the corpse [Agnes]”.

Meanwhile, Mr. and Mrs. Bumble have been kept in another room, and at a motion by Mr. Brownlow, are now brought in by Mr. Grimwig, to confirm this information. When the Bumbles flatly deny everything, and protest their innocence, Mr. Brownlow gestures to Mr. Grimwig again, who fetches “two palsied women, who shook and tottered as they walked.” They confirm that, listening outside the door, they had heard all the events that occurred at the death of Oliver’s mother. Then they had followed Mrs. Bumble to the pawnbroker’s shop, and watched as she accepted a locket and a gold ring from him.

Moreover they say that the nurse [Old Sally] had: “told us often … that the young mother had told her that, feeling she should never get over it, she was on her way … to die near the grave of the father of the child.”

Mr. Brownlow says he could even produce the pawnbroker, but it is not necessary. Mrs. Bumble confesses, but Mr. Bumble is keen to keep his position as Master of the workhouse, and blames her, saying that it was all his wife’s idea. But Mr. Brownlow will brook none of this. He says that he will make sure Mr. Bumble loses his job. In fact by law, he says, Mr. Bumble will be the more guilty, as that the law considers that a husband is responsible for his wife’s actions:

“If the law supposes that,” said Mr. Bumble, squeezing his hat emphatically in both hands, “the law is a ass—a idiot. If that’s the eye of the law, the law is a bachelor; and the worst I wish the law is, that his eye may be opened by experience—by experience.”

Now Mr. Brownlow turns reassuringly to Rose, and says to Monks:

“The father of the unhappy Agnes had two daughters … What was the fate of the other—the child?”

"Do you know this young lady, sir?" — James Mahoney 1871

Rose has never seen Monks before, but he says he has often watched her. Now he explains. After the death of Agnes’s father, in a remote part of Wales, the other younger daughter was taken in by some “wretched cottagers”, as Monks calls them, who raised her. Mr. Brownlow had tried to track them down, but:

“where friendship fails, hatred will often force a way”, and Monks’s mother had succeeded to locate these cottagers. She told them of the second daughter [Agnes]’s shame “with such alterations as suited her”. She told them that the second female child came of bad blood, was illegitimate, and was sure to go wrong in the future. They became disheartened, and even poorer, leading a miserable life. One day, by chance, a widow in Chester [Mrs. Maylie] saw this child and pited her. She took her to her own home to care for. The child remained there and was happy, to the great resentment of Monks.

When asked, Monks indicates that this female child is Rose. She is Agnes’s sister.

Oliver now understands that Rose is his aunt, but declares that he will call her sister, as: “something taught my heart to love [her] so dearly from the first”. Then Rose and Oliver embrace each other for a long, long time.

Harry Maylie enters the room and declares that he knows everything, and again asks Rose to marry him. However, Rose still feels that her father’s sense of disgrace at her sister’s history would bring shame on Harry if he married her. Harry responds by telling Rose that he has renounced any friends who would not accept her, thrown over all his wealthy connections, and no longer has any aspirations to be a member of parliament:

“Such power and patronage: such relatives of influence and rank: as smiled upon me then, look coldly now”

He plans to be happy with her, living as a humble village pastor. Rose and Harry can now marry after all, and share their future, because they are now equals.

"Rose" - Harry Furniss 1910

However, when all the party are assembled for supper, Oliver enters with tears streaming down his face. The narrator tells us:

“It is a world of disappointment: often to the hopes we most cherish, and hopes that do our nature the greatest honour.

Poor Dick was dead!“

This chapter 51 comprises installment 23

Chapter 51:

“Affording an Explanation of More Mysteries Than One …”

Just two days later, Oliver is in a carriage with Mrs. Maylie, Rose, Mrs. Bedwin, and Dr. Losberne. Mr. Brownlow, and a sixth person follow on in a post chaise. All of them are travelling fast to the town where Oliver was born; all are feeling the suspense of bringing the mystery to a conclusion. Oliver is quiet, but then sees the baby farm where he and his dear friend Dick grew up. He points it out excitedly to Rose, who agrees that they can take Dick away from there, so that he can grow strong and well.

Oliver has such a mixture of feelings as he recognises all the places he knows. When they pass Sowerberry’s, he thinks that it seems to be “smaller and less imposing in appearance than he remembered it.” The same seems to be true of Gamfield’s cart, the workhouse, and the town’s chief hotel. To Oliver, each place seems smaller than he remembered.

To Oliver’s surprise, they arrive at the the best hotel in town, where Mr. Grimwig is waiting to greet them. He too is very changed; affable and full of smiles as he kisses the ladies.

Mysterious things are happening, with a number of secret meetings between the men of the group. Once Mrs. Maylie was called away for an hour, and shows signs of weeping when she returns. Neither Rose or Oliver are included in the meetings and both are perplexed as to what is happening. But when it gets to 9 o’clock, all four men return, and Oliver is astonished to be told that the stranger with them, whom he recognises from before, is his brother, although:

“Monks cast a look of hate, which, even then, he could not dissemble, at the astonished boy”.

Mr. Brownlow assembles some papers he wants Monks to sign, and recaps:

“This child … is your half-brother; the illegitimate son of your father, my dear friend Edwin Leeford, by poor young Agnes Fleming, who died in giving him birth.”

Monks refers sullenly to the boy as a “bastard”, and on being reprimanded, takes up the story himself. He tells again, for those assembled, how Oliver’s father had been taken ill in Rome, and joined by his mother and himself, travelling from Paris. The next day Oliver’s father had died, his senses having gone, leaving two papers:

“enclosed in a few short lines to you, [Mr. Brownlow] with an intimation on the cover of the package that it was not to be forwarded till after he was dead. One of these papers was a letter to this girl Agnes; the other a will.”

Oliver’s father [Leeford]’s letter to Agnes was a “penitent confession” asking for her forgiveness. He had promised to marry her, saying that they must wait because there was a secret mystery, which he would explain one day. ”She trusted too far, and lost what none could ever give her back.“ A few months before the baby was due, he begged Agnes not to curse his memory, or: ”think the consequences of their sin would be visited on her or their young child; for all the guilt was his.” Tears are now streaming down Oliver’s face, as he hears Monks tell how his father had asked his mother to wear the locket and ring he had given her.

Mr. Brownlow prompts Monks about the will, but continues himself, as Monks is silent. He describes how miserable Oliver’s father’s wife had made him, and describes Monks as a boy with a: “rebellious disposition, vice, malice, and premature bad passions … who had been trained to hate him”.

The will stipulated £800 pounds should be given each to his wife and her son, Edward [Monks], and left the rest of his fortune to be divided between Agnes and her unborn child. If it was a daughter there were no conditions, but if it was to be a son, the inheritance was conditional on him reaching adulthood without engaging in any criminal acts.

“He did this, he said, to mark his confidence in the mother, and his conviction—only strengthened by approaching death—that the child would share her gentle heart, and noble nature.”

Monks now comes in loudly to defend his own mother, saying that she burnt the will, and secretly held back the letter and other proofs as security. He tells how Agnes’s father got the truth out of her, and fled to Wales with his family, full of shame and dishonour. He even changed his name. Agnes had run away before he fled, and her father searched for her unsuccesfully, and then died soon after:

“it was on the night when he returned home, assured that she had destroyed herself, to hide her shame and his, that his old heart broke.”

Mr. Brownlow continues, telling how at 18 years of age, Monks had stolen his mother’s money and jewels, and “gambled, squandered, forged, and fled to London: where for two years he had associated with the lowest outcasts.” Monks’s mother had told him this herself personally, when old and ill, and “sinking under a painful and incurable disease”. She had hoped to see her son before she died. Eventually Monks was found, and reconciled, they returned to France together.

His mother reaffirmed the bitterness and hatred she felt towards the young woman [Agnes] and encouraged Monks to share it. His mother told him that she believed the young woman had borne a son, whereupon Monks said he:

“swore to her, if ever it crossed my path, to hunt it down; never to let it rest; to pursue it with the bitterest and most unrelenting animosity; to vent upon it the hatred that I deeply felt, and to spit upon the empty vaunt of that insulting will by dragging it, if I could, to the very gallows-foot.”

Mr. Brownlow adds that “the Jew” [Fagin] had been offered a reward for keeping Oliver and turning him into a criminal, but that he would have forfeited some of the money if Oliver had escaped. Monks also confesses to buying the ring and locket from “the man and woman I told you of, [the Bumbles] who stole them from the nurse [Old Sally], who stole them from the corpse [Agnes]”.

Meanwhile, Mr. and Mrs. Bumble have been kept in another room, and at a motion by Mr. Brownlow, are now brought in by Mr. Grimwig, to confirm this information. When the Bumbles flatly deny everything, and protest their innocence, Mr. Brownlow gestures to Mr. Grimwig again, who fetches “two palsied women, who shook and tottered as they walked.” They confirm that, listening outside the door, they had heard all the events that occurred at the death of Oliver’s mother. Then they had followed Mrs. Bumble to the pawnbroker’s shop, and watched as she accepted a locket and a gold ring from him.

Moreover they say that the nurse [Old Sally] had: “told us often … that the young mother had told her that, feeling she should never get over it, she was on her way … to die near the grave of the father of the child.”

Mr. Brownlow says he could even produce the pawnbroker, but it is not necessary. Mrs. Bumble confesses, but Mr. Bumble is keen to keep his position as Master of the workhouse, and blames her, saying that it was all his wife’s idea. But Mr. Brownlow will brook none of this. He says that he will make sure Mr. Bumble loses his job. In fact by law, he says, Mr. Bumble will be the more guilty, as that the law considers that a husband is responsible for his wife’s actions:

“If the law supposes that,” said Mr. Bumble, squeezing his hat emphatically in both hands, “the law is a ass—a idiot. If that’s the eye of the law, the law is a bachelor; and the worst I wish the law is, that his eye may be opened by experience—by experience.”

Now Mr. Brownlow turns reassuringly to Rose, and says to Monks:

“The father of the unhappy Agnes had two daughters … What was the fate of the other—the child?”

"Do you know this young lady, sir?" — James Mahoney 1871

Rose has never seen Monks before, but he says he has often watched her. Now he explains. After the death of Agnes’s father, in a remote part of Wales, the other younger daughter was taken in by some “wretched cottagers”, as Monks calls them, who raised her. Mr. Brownlow had tried to track them down, but:

“where friendship fails, hatred will often force a way”, and Monks’s mother had succeeded to locate these cottagers. She told them of the second daughter [Agnes]’s shame “with such alterations as suited her”. She told them that the second female child came of bad blood, was illegitimate, and was sure to go wrong in the future. They became disheartened, and even poorer, leading a miserable life. One day, by chance, a widow in Chester [Mrs. Maylie] saw this child and pited her. She took her to her own home to care for. The child remained there and was happy, to the great resentment of Monks.

When asked, Monks indicates that this female child is Rose. She is Agnes’s sister.

Oliver now understands that Rose is his aunt, but declares that he will call her sister, as: “something taught my heart to love [her] so dearly from the first”. Then Rose and Oliver embrace each other for a long, long time.

Harry Maylie enters the room and declares that he knows everything, and again asks Rose to marry him. However, Rose still feels that her father’s sense of disgrace at her sister’s history would bring shame on Harry if he married her. Harry responds by telling Rose that he has renounced any friends who would not accept her, thrown over all his wealthy connections, and no longer has any aspirations to be a member of parliament:

“Such power and patronage: such relatives of influence and rank: as smiled upon me then, look coldly now”

He plans to be happy with her, living as a humble village pastor. Rose and Harry can now marry after all, and share their future, because they are now equals.

"Rose" - Harry Furniss 1910

However, when all the party are assembled for supper, Oliver enters with tears streaming down his face. The narrator tells us:

“It is a world of disappointment: often to the hopes we most cherish, and hopes that do our nature the greatest honour.

Poor Dick was dead!“

This chapter 51 comprises installment 23

message 178:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 25, 2023 07:05AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Well we might have thought we’d sorted out the story’s mysteries, but here we have yet another convulted chapter of explanations; a sort of part 2 from chapter 49! The original reader had 22 months of reading the text, with all their questions; all the mysteries then to be explained in just 2 chapters! At least Charles Dickens gave us fair warning in the title …

Originally chapter 51 comprised two chapters, but in 1838 and 1846 Charles Dickens had tweaked it and formed it into a whole (which explains the length of my summary 🙄 - sorry! I felt it needed to be comprehensive, but hadn't bargained on a "part 2")

Originally chapter 51 comprised two chapters, but in 1838 and 1846 Charles Dickens had tweaked it and formed it into a whole (which explains the length of my summary 🙄 - sorry! I felt it needed to be comprehensive, but hadn't bargained on a "part 2")

message 179:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 25, 2023 07:07AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Was anyone else aware of the theatricality of this chapter? It was almost like watching a drama on stage. Characters all had their own entrance and the final one even decribes Oliver “glid[ing] away, and g[iving] place to Harry Maylie“.

Although it was horrendously complicated to disentangle this web of connections, I do think Charles Dickens wrote a skilful chaper, with the switching of storytellers between the benevolent Mr. Brownlow and the sullen Monks, a comic interlude in the middle with the Bumbles (who surely have got their just deserts!) and the happy sentimental conclusion for the young couple.

We are brought back to Earth by Dick’s demise though. I’ve pondered this for a while. We have seen that both good and bad characters are getting what they deserve. However, Charles Dickens does not want to distract us from the main point by this. I think it is probably to reinforce the message of the novel, that if there is not major change in social policy, there will continue to be innocent victims like Dick.

Although it was horrendously complicated to disentangle this web of connections, I do think Charles Dickens wrote a skilful chaper, with the switching of storytellers between the benevolent Mr. Brownlow and the sullen Monks, a comic interlude in the middle with the Bumbles (who surely have got their just deserts!) and the happy sentimental conclusion for the young couple.

We are brought back to Earth by Dick’s demise though. I’ve pondered this for a while. We have seen that both good and bad characters are getting what they deserve. However, Charles Dickens does not want to distract us from the main point by this. I think it is probably to reinforce the message of the novel, that if there is not major change in social policy, there will continue to be innocent victims like Dick.

message 180:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 26, 2023 03:07AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

And a little more …

The illustrations of Rose

George Cruikshank, Charles Dickens’s original illustrator in "Bentley’s Miscellany" depicts Rose only twice. The first one is in the covert meeting under London Bridge between the “respectable” and the “low” woman, Rose and Nancy, and then again in the upcoming concluding scene in chapter 53. Because George Cruikshank did not yet know the entire story, he had no idea how important she would prove to be.

The later illustrator Harry Furniss had the advantage of familarity with the whole story, and pays Rose far more attention. My favourite is the single illustration by Charles Pears, but Harry Furniss regularly seems to capture Rose far better than, say, James Mahoney. For instance, Harry Furniss distinguishes Nancy, in contrast to the darker, heavier Nancy, (discounting the ridiculous portrayals of 17 year old Nancy as an old blousy hag) by her sensitivity and emotionalism. His illustration of her expression as she pities Nancy when the two meet in the hotel, is subtle and superb, and also when she urges Mr. Brownlow to assist her in escaping from moral degradation in The Meeting under London Bridge (Chapter 46).

In these last four appearances, we can see his faithful reproduction of Charles Dickens’s vision for Rose, from the following passage from much earlier in the novel, when we know Charles Dickens was thinking of Mary Hogarth:

“The younger lady was in the lovely bloom and spring-time of womanhood; at that age, when, if ever angels be for God’s good purposes enthroned in mortal forms, they may be, without impiety, supposed to abide in such as hers.

She was not past seventeen. Cast in so slight and exquisite a mould; so mild and gentle; so pure and beautiful; that earth seemed not her element, nor its rough creatures her fit companions. The very intelligence that shone in her deep blue eye, and was stamped upon her noble head, seemed scarcely of her age, or of the world; and yet the changing expression of sweetness and good humour, the thousand lights that played about the face, and left no shadow there; above all, the smile, the cheerful, happy smile, were made for Home, and fireside peace and happiness. (Chapter 29)

Then in Chapter 35, having received Harry’s marriage proposal but turned him down despite her own chance for happiness, she cries at the moment of self-sacrifice that she believes would have preserved Harry’s political career:

“when one [tear] fell upon the flower over which she bent, and glistened brightly in its cup, making it more beautiful, it seemed as though the outpouring of her fresh young heart, claimed kindred with the loveliest things in nature.”

Despite the shadow over her birth, Rose is an idealised young woman. Rose’s sudden illness threatens Oliver’s implicit belief in the beneficent powers of Providence, but Rose’s recovery in her natural milieu, the English countyside, seems to vindicate that trust in natural justice. We also saw that by her recovery, Charles Dickens wrote the ending for Rose that he yearned to give his sister-in-law Mary. Dramatically, there is no other reason for Rose’s sudden illness.

Interestingly, in his final illustration here, Harry Furniss detaches Rose from any particular scene. The portrait has no quotation or title beyond her name. She is presented as the human equivalent of the rose.

The illustrations of Rose

George Cruikshank, Charles Dickens’s original illustrator in "Bentley’s Miscellany" depicts Rose only twice. The first one is in the covert meeting under London Bridge between the “respectable” and the “low” woman, Rose and Nancy, and then again in the upcoming concluding scene in chapter 53. Because George Cruikshank did not yet know the entire story, he had no idea how important she would prove to be.

The later illustrator Harry Furniss had the advantage of familarity with the whole story, and pays Rose far more attention. My favourite is the single illustration by Charles Pears, but Harry Furniss regularly seems to capture Rose far better than, say, James Mahoney. For instance, Harry Furniss distinguishes Nancy, in contrast to the darker, heavier Nancy, (discounting the ridiculous portrayals of 17 year old Nancy as an old blousy hag) by her sensitivity and emotionalism. His illustration of her expression as she pities Nancy when the two meet in the hotel, is subtle and superb, and also when she urges Mr. Brownlow to assist her in escaping from moral degradation in The Meeting under London Bridge (Chapter 46).

In these last four appearances, we can see his faithful reproduction of Charles Dickens’s vision for Rose, from the following passage from much earlier in the novel, when we know Charles Dickens was thinking of Mary Hogarth:

“The younger lady was in the lovely bloom and spring-time of womanhood; at that age, when, if ever angels be for God’s good purposes enthroned in mortal forms, they may be, without impiety, supposed to abide in such as hers.

She was not past seventeen. Cast in so slight and exquisite a mould; so mild and gentle; so pure and beautiful; that earth seemed not her element, nor its rough creatures her fit companions. The very intelligence that shone in her deep blue eye, and was stamped upon her noble head, seemed scarcely of her age, or of the world; and yet the changing expression of sweetness and good humour, the thousand lights that played about the face, and left no shadow there; above all, the smile, the cheerful, happy smile, were made for Home, and fireside peace and happiness. (Chapter 29)

Then in Chapter 35, having received Harry’s marriage proposal but turned him down despite her own chance for happiness, she cries at the moment of self-sacrifice that she believes would have preserved Harry’s political career:

“when one [tear] fell upon the flower over which she bent, and glistened brightly in its cup, making it more beautiful, it seemed as though the outpouring of her fresh young heart, claimed kindred with the loveliest things in nature.”

Despite the shadow over her birth, Rose is an idealised young woman. Rose’s sudden illness threatens Oliver’s implicit belief in the beneficent powers of Providence, but Rose’s recovery in her natural milieu, the English countyside, seems to vindicate that trust in natural justice. We also saw that by her recovery, Charles Dickens wrote the ending for Rose that he yearned to give his sister-in-law Mary. Dramatically, there is no other reason for Rose’s sudden illness.

Interestingly, in his final illustration here, Harry Furniss detaches Rose from any particular scene. The portrait has no quotation or title beyond her name. She is presented as the human equivalent of the rose.

message 181:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 26, 2023 03:01AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

And yet a little more …

Writing Style: Charles Dickens's Life at the Time of the Upcoming Chapters (no spoilers!)

In his Life of Charles Dickens, John Forster recorded Charles Dickens's note to him, when he was writing the next (and final) installment:

“No, no, ... don’t, don’t let us ride till to-morrow, not having yet disposed of the Jew, who is such an out-and-outer that I don’t know what to make of him.”

John Forster himself continues:

“No small difficulty to an inventor, where the creatures of his invention are found to be as real as himself; but this also was mastered; and then there remained but the closing quiet chapter to tell the fortunes of those who had figured in the tale. To this he summoned me in the first week of September, replying to a request of mine that he’d give me a call that day:

“Come and give me a call, and let us have ‘a bit o’ talk’ before we have a bit o’ som’at else. My missis is going out to dinner, and I ought to go, but I have got a bad cold. So do you come, and sit here, and read, or work, or do something, while I write the LAST chapter of Oliver, which will be arter a lamb chop.”

How well I remember that evening! and our talk of what should be the fate of Charley Bates, on behalf of whom (as indeed for the Dodger too) Talfourd had pleaded as earnestly in mitigation of judgment as ever at the bar for any client he had most respected.“

(Sir Thomas Noon Talfourd was an English judge as well as a Radical politician and author. Charles Dickens had dedicated The Pickwick Papers to him.)

More extracts from John Forster, under a spoiler merely for space reasons:

(view spoiler)

There is much more about this in Life of Charles Dickens. So many critics write about Oliver Twist, but only John Forster was there at the time, can tell us what Charles Dickens said to him then, and was privy to his thoughts.

Do read his three volumes if you can, and come and tell us what you think of them in our side reads threads.

Writing Style: Charles Dickens's Life at the Time of the Upcoming Chapters (no spoilers!)

In his Life of Charles Dickens, John Forster recorded Charles Dickens's note to him, when he was writing the next (and final) installment:

“No, no, ... don’t, don’t let us ride till to-morrow, not having yet disposed of the Jew, who is such an out-and-outer that I don’t know what to make of him.”

John Forster himself continues:

“No small difficulty to an inventor, where the creatures of his invention are found to be as real as himself; but this also was mastered; and then there remained but the closing quiet chapter to tell the fortunes of those who had figured in the tale. To this he summoned me in the first week of September, replying to a request of mine that he’d give me a call that day:

“Come and give me a call, and let us have ‘a bit o’ talk’ before we have a bit o’ som’at else. My missis is going out to dinner, and I ought to go, but I have got a bad cold. So do you come, and sit here, and read, or work, or do something, while I write the LAST chapter of Oliver, which will be arter a lamb chop.”

How well I remember that evening! and our talk of what should be the fate of Charley Bates, on behalf of whom (as indeed for the Dodger too) Talfourd had pleaded as earnestly in mitigation of judgment as ever at the bar for any client he had most respected.“

(Sir Thomas Noon Talfourd was an English judge as well as a Radical politician and author. Charles Dickens had dedicated The Pickwick Papers to him.)

More extracts from John Forster, under a spoiler merely for space reasons:

(view spoiler)

There is much more about this in Life of Charles Dickens. So many critics write about Oliver Twist, but only John Forster was there at the time, can tell us what Charles Dickens said to him then, and was privy to his thoughts.

Do read his three volumes if you can, and come and tell us what you think of them in our side reads threads.

message 182:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 25, 2023 08:08AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

We now have one day free, and begin our final installment 24, with chapter 52 on Thursday.

Over to you!

Over to you!

I love that you can count on Dickens to tie up every loose end and tell you the outcome for every single character. The loss of Dick was blow. I had hoped he and Oliver would be raised from here like brothers. It does, however, as you pointed out, serve to reinforce the theme of how society is failing these youngsters.

I love that you can count on Dickens to tie up every loose end and tell you the outcome for every single character. The loss of Dick was blow. I had hoped he and Oliver would be raised from here like brothers. It does, however, as you pointed out, serve to reinforce the theme of how society is failing these youngsters. Thank you, Jean, for all the quotations from Forster. It is lovely to imagine their conversations, and I am quite grateful for Forster's first hand account of Dickens' thoughts. I got midway through the second book and truly need to pick this series up again.

I want to get to Forster’s book too and appreciate these occasional reminders of all that awaits me in those three volumes.

I want to get to Forster’s book too and appreciate these occasional reminders of all that awaits me in those three volumes.In this chapter I was very pleased at the Bumbles’s future. And surprised that Mr Bumble could even think he could weasel his way out of his personal guilt. And to think that the three old ladies made a point of listening at the door and overhearing what happened at the old “nurse’s” death.

Dickens must have kept an amazing chart to keep tack of all the plot lines he needed to complete. What a brain! Imagine what he might have been or done in the 20th or 21st century!

Sam wrote: "Trying to squeeze out a few more thoughts before Jean's next post. My main thought is the theme of betrayal in Oliver Twist but I have a few digressions before I get there.

Sam wrote: "Trying to squeeze out a few more thoughts before Jean's next post. My main thought is the theme of betrayal in Oliver Twist but I have a few digressions before I get there.First on Bill and Nancy..."

Great insight, Sam! In many ways, Dickens has always struck me as a performer. He is always looking for ways to wow his audience, most frequently by means of over-the-top character sketches, sardonic comments, etc. He often wrote passages that were clearly structured for their auditory effect when read aloud. The avalanche of sibilants you refer to was undoubtedly deliberate.

Yes! I am in the middle of Vol 1 of Forster’s series, and it is fascinating. I had forgotten I could be adding comments as I read Forster so will do that soon. We are so fortunate that Dickens found a friend to be his confidante as well as trusted advisor. Forster fulfilled his promises to Dickens!

Yes! I am in the middle of Vol 1 of Forster’s series, and it is fascinating. I had forgotten I could be adding comments as I read Forster so will do that soon. We are so fortunate that Dickens found a friend to be his confidante as well as trusted advisor. Forster fulfilled his promises to Dickens!

Lee, Sara and Sue - John Forster's 3 volume Life of Charles Dickens will replace Dickens and the Workhouse: Oliver Twist and the London Poor as our side read, alongside our upcoming short reads.

Jim and Sam - Indeed as we often say Charles Dickens first love was the theatre, not novel-writing.

Ready for another bit of theatre?

Jim and Sam - Indeed as we often say Charles Dickens first love was the theatre, not novel-writing.

Ready for another bit of theatre?

message 188:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jul 27, 2023 08:08AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Installment 24

Chapter 52:

Fagin’s Last Night Alive …

“The court was paved, from floor to roof, with human faces. Inquisitive and eager eyes peered from every inch of space.”

All eyes are fixed on Fagin in the witness box:

with one hand resting on the wooden slab before him, the other held to his ear, and his head thrust forward to enable him to catch with greater distinctness every word that fell from the presiding judge“

Fagin looks towards his counsel in mute appeal, but all he can hear is the buzz of the courtroom, where everyone is of one mind: that he should be condemned. The jury retire, and he looks wistfully into their faces. It is very hot and close. As they await the jury’s verdict, Fagin’s mind is full of horrors. And then:

“Perfect stillness ensued—not a rustle—not a breath—Guilty.

The building rang with a tremendous shout, and another, and another, and then it echoed loud groans, that gathered strength as they swelled out, like angry thunder. It was a peal of joy from the populace outside, greeting the news that he would die on Monday.“

Did he have anything to say in his defence, before the judge put on the black cap to order the death penalty? Nothing, save that he was “an old man—an old man—and so, dropping into a whisper, was silent again”.

The day was Friday. Fagin, found guilty, is condemned to hang on the following Monday. He is taken away after his sentencing, and as he passes, people shout insults at him, screeching and hissing.

"He sat down on a stone bench opposite the door" - James Mahoney 1871

Now Fagin sits in his cell in the dark, gradually realising the horror of what is to come. He remembers the faces of all the men he has seen hanged, sometimes through his own wiles, and remembers laughing at some of them. He remembers the “rattling noise [as] the drop went down; and how suddenly they changed, from strong and vigorous men to dangling heaps of clothes!”

Someone comes to stay with him; there have been instructions that he must not be left alone, nor left with anything by which he could end his own life. He waits through the weekend, counting down the hours he has left to live. Another day passes and another night. His thoughts become wilder and more unfocused:

“At one time he raved and blasphemed; and at another howled and tore his hair. Venerable men of his own persuasion had come to pray beside him, but he had driven them away with curses.”

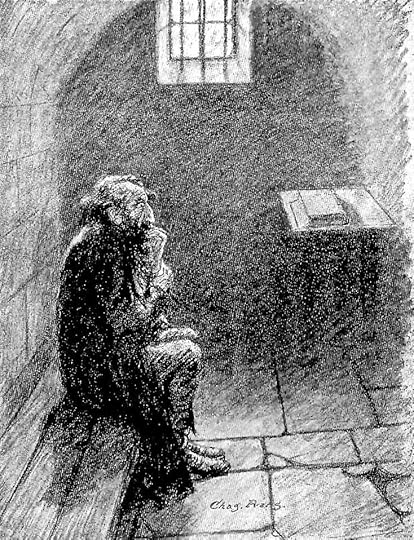

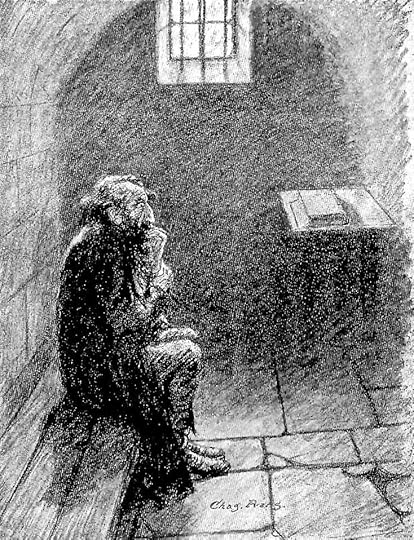

"Fagin" - Charles Pears 1912

On the last night:

“a withering sense of his helpless, desperate state came in its full intensity upon his blighted soul …

he started up, every minute, and with gasping mouth and burning skin, hurried to and fro, in such a paroxysm of fear and wrath that even they—used to such sights—recoiled from him with horror.“.

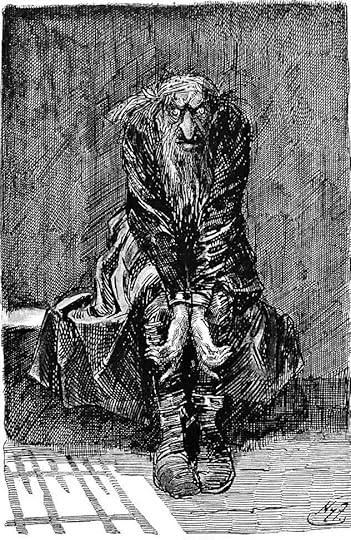

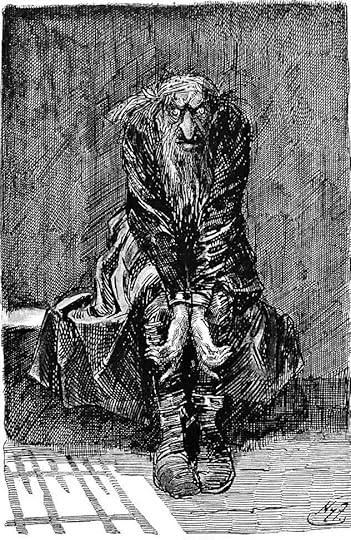

"Fagin in the condemned cell" - George Cruikshank November 1838

At around midnight on Sunday, Mr. Brownlow and Oliver come to see Fagin. The guard is reluctant to let such a young gentleman in, protesting: “It’s not a sight for children, sir.”

but Mr. Brownlow makes it clear that it is important, and they are allowed in. As they go along the passage, they can hear the scaffold being built. When they reach his cell, Fagin is rambling, talking to people who are not there such as Charley. He wants vengeance on the person who has “caused all this” by peaching on him, saying:

“Bolter’s throat, Bill; never mind the girl—Bolter’s throat as deep as you can cut. Saw his head off!”

but is called back to himself by a sharp word from the jailer, who says that Fagin gets worse as time goes on. Fagin’s face:

“retain[s] no human expression but rage and terror. “Strike them all dead! What right have they to butcher me?”

Mr. Brownlow wants to know the location of some papers Monks gave him. Fagin denies knowing anything at first, but Mr. Brownlow urges him:

“Do not say that now, upon the very verge of death; but tell me where they are. You know that Sikes is dead; that Monks has confessed; that there is no hope of any further gain …”

And Fagin whispers the location to Oliver. Oliver is desperately sorry for the man, and offers to stay and pray with him all night, but Fagin wants the boy to help him escape. His jailers pull him back, and he screams.

Outside, the crowd gathers around the gallows:

“smoking and playing cards to beguile the time; the crowd were pushing, quarrelling, joking. Everything told of life and animation, but one dark cluster of objects in the centre of all—the black stage, the cross-beam, the rope, and all the hideous apparatus of death.”

"Fagin in the condemned cell" Harry Furniss 1910

Chapter 52:

Fagin’s Last Night Alive …

“The court was paved, from floor to roof, with human faces. Inquisitive and eager eyes peered from every inch of space.”

All eyes are fixed on Fagin in the witness box:

with one hand resting on the wooden slab before him, the other held to his ear, and his head thrust forward to enable him to catch with greater distinctness every word that fell from the presiding judge“

Fagin looks towards his counsel in mute appeal, but all he can hear is the buzz of the courtroom, where everyone is of one mind: that he should be condemned. The jury retire, and he looks wistfully into their faces. It is very hot and close. As they await the jury’s verdict, Fagin’s mind is full of horrors. And then:

“Perfect stillness ensued—not a rustle—not a breath—Guilty.

The building rang with a tremendous shout, and another, and another, and then it echoed loud groans, that gathered strength as they swelled out, like angry thunder. It was a peal of joy from the populace outside, greeting the news that he would die on Monday.“

Did he have anything to say in his defence, before the judge put on the black cap to order the death penalty? Nothing, save that he was “an old man—an old man—and so, dropping into a whisper, was silent again”.

The day was Friday. Fagin, found guilty, is condemned to hang on the following Monday. He is taken away after his sentencing, and as he passes, people shout insults at him, screeching and hissing.

"He sat down on a stone bench opposite the door" - James Mahoney 1871

Now Fagin sits in his cell in the dark, gradually realising the horror of what is to come. He remembers the faces of all the men he has seen hanged, sometimes through his own wiles, and remembers laughing at some of them. He remembers the “rattling noise [as] the drop went down; and how suddenly they changed, from strong and vigorous men to dangling heaps of clothes!”

Someone comes to stay with him; there have been instructions that he must not be left alone, nor left with anything by which he could end his own life. He waits through the weekend, counting down the hours he has left to live. Another day passes and another night. His thoughts become wilder and more unfocused:

“At one time he raved and blasphemed; and at another howled and tore his hair. Venerable men of his own persuasion had come to pray beside him, but he had driven them away with curses.”

"Fagin" - Charles Pears 1912

On the last night:

“a withering sense of his helpless, desperate state came in its full intensity upon his blighted soul …

he started up, every minute, and with gasping mouth and burning skin, hurried to and fro, in such a paroxysm of fear and wrath that even they—used to such sights—recoiled from him with horror.“.

"Fagin in the condemned cell" - George Cruikshank November 1838

At around midnight on Sunday, Mr. Brownlow and Oliver come to see Fagin. The guard is reluctant to let such a young gentleman in, protesting: “It’s not a sight for children, sir.”

but Mr. Brownlow makes it clear that it is important, and they are allowed in. As they go along the passage, they can hear the scaffold being built. When they reach his cell, Fagin is rambling, talking to people who are not there such as Charley. He wants vengeance on the person who has “caused all this” by peaching on him, saying:

“Bolter’s throat, Bill; never mind the girl—Bolter’s throat as deep as you can cut. Saw his head off!”

but is called back to himself by a sharp word from the jailer, who says that Fagin gets worse as time goes on. Fagin’s face:

“retain[s] no human expression but rage and terror. “Strike them all dead! What right have they to butcher me?”