The Readers Review: Literature from 1714 to 1910 discussion

This topic is about

Mansfield Park

2022/23 Group Reads - Archives

>

Mansfield Park Week 5: June 18-24: Volume 3, Chapters 1-8

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Many of us were scornful of how Fanny is treated at Mansfield Park, but then we get to see the alternative. I thought it was interesting that Austen doesn't do what many authors do (Tolstoy and Dickens, at least sometimes) of romanticizing the working-class characters. We have seen the shallowness of the wealthy but home isn't presented as an improvement. If Fanny had stayed at home all the time, she probably would have worn herself out doing more than her share of the work and trying to impart some morals to her siblings. It seems like Fanny's morals are internal, not just something she had to take on in her new home.

Although Fanny's prejudices about her birth family don't necessarily reflect well on her, I did have a lot of sympathy. There's a wonderful line when she first goes into the house and thinks she has stopped in the hall, only to discover herself in the world's smallest parlour. I had a "sitting room" like that myself once in a shared flat. We sat in rows along the walls, and anyone going to the kitchen had to walk between us.

Although Fanny's prejudices about her birth family don't necessarily reflect well on her, I did have a lot of sympathy. There's a wonderful line when she first goes into the house and thinks she has stopped in the hall, only to discover herself in the world's smallest parlour. I had a "sitting room" like that myself once in a shared flat. We sat in rows along the walls, and anyone going to the kitchen had to walk between us.It certainly proves the saying that you can never go back. I do suspect Henry Crawford would have been successful eventually, if Fanny had stayed longer, if he had continued on the path to steadiness (a big if) and, most important, if Edmund had become engaged to Mary.

I think this certainly speaks to the precariousness of young women's lives in this age-if for whatever reason her Aunt and Uncle become displeased with Fanny (for example if she refuses the marriage they believe she should accept) she could be sent back to her parents where she will likely wear out her welcome if she becomes simply another mouth to feed. She has shown herself to be useful in helping sort out William's linen, however I can't imagine she has any useful housekeeping skills beyond sewing at this point-can she help her mother better manage the servants and younger children, as William hopes?

I do not believe that Henry Crawford has changed in any fundamental way. He likes the chase, and he only wants Fanny more because she rejects him. It will not end well if she finally accepts him. I believe that Sir Thomas and Edmund are good men who think they have Fanny’s best interests at heart, but they are products of the age they live in, a time when both sexes believed women needed the guidance of men to manage their own lives. “No means no” is not a concept they would understand. Of course, if Edmund succeeds in marrying Miss Crawford, Fanny may end up with Henry, and both marriages will be disastrous.

I do not believe that Henry Crawford has changed in any fundamental way. He likes the chase, and he only wants Fanny more because she rejects him. It will not end well if she finally accepts him. I believe that Sir Thomas and Edmund are good men who think they have Fanny’s best interests at heart, but they are products of the age they live in, a time when both sexes believed women needed the guidance of men to manage their own lives. “No means no” is not a concept they would understand. Of course, if Edmund succeeds in marrying Miss Crawford, Fanny may end up with Henry, and both marriages will be disastrous. Fanny’s return to the Price home was such a disappointment to her. She wanted the comfort of a mother (something she never received from Lady Bertram or Mrs. Norris), but her mother was not that person. As someone who is very sensitive to noise and turmoil, I felt a real kinship with Fanny over her exhaustion from being in such a disorderly home after the relative peacefulness of Mansfield Park.

No, Fanny really does not have useful skills of any kind. The ladies companion thing is about it, and even that she is rather poorly suited as she is not much for conversation or long strolls, does not play or enjoy music.

No, Fanny really does not have useful skills of any kind. The ladies companion thing is about it, and even that she is rather poorly suited as she is not much for conversation or long strolls, does not play or enjoy music.Poor Fanny. At Mansfield she was a duck among swans, at Portsmouth she is the reverse.

Frances, you pose an interesting question about what Fanny would be like if she had stayed with her family instead of being moved to Mansfield Park. We got a hint early on that she was useful at home as the eldest daughter in caring for the children (she had always been important to them “as play-fellow, instructress, and nurse,” vol. 1 chap. 2), so by the time she reached adulthood she would have been skilled in child-rearing and, considering her mother’s incapacity, probably would have been running the household. That is, if she had survived—but her health being fragile, she might well have died nursing her favorite sister, Mary. Continuing to live in a dirty home with inadequate food would most likely have cost her her life in those days.

Frances, you pose an interesting question about what Fanny would be like if she had stayed with her family instead of being moved to Mansfield Park. We got a hint early on that she was useful at home as the eldest daughter in caring for the children (she had always been important to them “as play-fellow, instructress, and nurse,” vol. 1 chap. 2), so by the time she reached adulthood she would have been skilled in child-rearing and, considering her mother’s incapacity, probably would have been running the household. That is, if she had survived—but her health being fragile, she might well have died nursing her favorite sister, Mary. Continuing to live in a dirty home with inadequate food would most likely have cost her her life in those days.As for Henry Crawford, we get several examples here of him playing a role—his very fine reading of Henry VIII, and notably the conversation in which he imagines himself as a clergyman, but only on an occasional basis: “I do not know that I should be fond of preaching often; now and then, perhaps, once or twice in the spring, after being anxiously expected for half a dozen Sundays together, but not for a constancy; it would not do for a constancy” (vol. 3, chap. 3). Edmund only laughs at him, but constancy crops up on several occasions in this section and even Sir Thomas, though approving of the match between Henry and Fanny, wished Henry “to be a model of constancy and fancied the best means of effecting it would be by not trying him too long” (vol. 3, chap. 4). A classic bit of Austen snark!

What jumped out at me in this section was how many characters act for self-serving reasons, even William who enjoys talking with his sister to a great extent because it allows him to obsess about his posting to the Thrush. So many people’s motives are described in selfish terms. The most extreme perhaps is Mary Crawford, writing all those letters to Fanny so that (1) her brother can inappropriately write to her and (2) Mary herself can inappropriately write to Edmund. No wonder Fanny found the correspondence “cruelly mortifying.” So much of the action in this story involves people being selfish and their selfishness harming others. And of course when Fanny gets to Portsmouth, everyone is wrapped up in their own affairs and can’t spare much attention for her, reinforcing her feelings of being unloved. Much of her personality is tangled up in that central lack in her life, being unwanted. And Henry wants her, which makes her refusal to consider his offer of marriage because she disapproves of his character even more striking. Not to mention perilous—what will she do if he proves, against all odds, constant? Especially if Edmund proposes to Mary and is accepted. I love the way this book is constructed and how its premises play out in the action.

Three things stand out for me in this section. Firstly, Henry Crawford seems to be a weird combination of the subject of a 1966 hit by the Chiffons and Richard Burbage.

Three things stand out for me in this section. Firstly, Henry Crawford seems to be a weird combination of the subject of a 1966 hit by the Chiffons and Richard Burbage. Secondly, Fanny ought to be renamed ‘HMS Resolution’ and thirdly Edmund would benefit from a regency version of a ‘Betty Ford’ clinic for his Mary addiction.

I agree with almost all Abigail’s comments. Regarding Henry Crawford, his whole change of character is nothing but an act, an example of which was so beautifully portrayed by himself in his performance of the Shakespeare play. Yes he can rival Richard Burbage when it comes to masking his real self and donning theatrical guises. And as for his forcing Fanny to speak to him, that was nothing more than harassment, even if it was done so sweetly. This sweet talking guy …….

https://www.songfacts.com/lyrics/the-...

would pretend to be anything that the object of his desire wants him to be in order to get what he wants.

If Fanny seemed to think that Henry was improving by all this sweet talk, Mary’s efforts at helping him didn’t seem to be hitting the right notes. Mary admitted both the deceit about the necklace and the dangerous intimacies with Maria and then went on to say….

‘ "Ah! I cannot deny it. He has now and then been a sad flirt, and cared very little for the havoc he might be making in young ladies' affections. I have often scolded him for it, but it is his only fault; and there is this to be said, that very few young ladies have any affections worth caring for.’

So even though Henry’s excellent play acting may have been having some effect on Fanny’s impression on his overall character, she still stayed resolute in her beliefs that she could never marry him. She was like Captain Cook’s famous ship which started off as a lowly coal carrier but was refitted and was strong enough to withstand all the storms the world’s seas could throw at her. Even the formidable Sir Thomas and then her beloved Edmund could not persuade her to accept Henry. As if in the eye of a storm, Fanny held firm right up to Henry’s departure. Henry then utilised the skill only the greatest actors possess, the ‘pregnant pause’………..

’ Quite unlike his usual self, he scarcely said anything. He was evidently oppressed, and Fanny must grieve for him, though hoping she might never see him again till he were the husband of some other woman.’

It didn’t work.

As for Edmund, as soon as he returned to Mansfield, all the good work in rehabilitating himself disintegrated with one impish smile from Mary.

As for Edmund, as soon as he returned to Mansfield, all the good work in rehabilitating himself disintegrated with one impish smile from Mary.’His objections, the scruples of his integrity, seemed all done away, nobody could tell how; and the doubts and hesitations of her ambition were equally got over—and equally without apparent reason. It could only be imputed to increasing attachment.’

She was a drug he couldn’t leave alone. Deep down he knew that there were too many things wrong with Mary to suit him, yet his fierce resistance to admitting such realities quickly led him back to his addiction. In Mary’s presence and even in her near vicinity he succumbed to her opiate affect on his brain. Mary roused some of his senses but then Edmund’s common sense disappeared. The fact that he could not control such feelings, which he called love, revealed how much Edmund didn’t really know about himself.

If only there had been a Dolly Payne Todd Madison Centre (but that would have been in the USA), or a Countess Louisa Jenkinson Centre, for Edmund to attend he might have been able to rid himself of his terrible Mary addiction.

Trev - you write so wondefully (even if I don't understand half of your 'modern' references).

Trev - you write so wondefully (even if I don't understand half of your 'modern' references). What has caught my attention this time is the debate on nature vs. nurture buried here and there in the text, mainly as a difference between Edmund and Fanny: Edmund believes he can 'improve' Mary (which is a wonderful excuse to accept her faults), and is convinced Fanny can have the same effect on Henry. Fanny has the opposite view: she takes Henry and Mary for what they are and does not believe they will change, or at least that she would be able to change Henry. She has evidence: if Mary has not changed in this time of 'first love', when would she?

I read the sections with this conflict very carefully to find out where the narrator places herself in the debate. This voice, however, is rather cautious:

... and she may be forgiven by older sages for looking on the chance of Miss Crawford’s future improvement as nearly desperate, for thinking that if Edmund’s influence in this season of love had already done so little in clearing her judgment, and regulating her notions, his worth would be finally wasted on her even in years of matrimony.

Experience might have hoped more for any young people so circumstanced, and impartiality would not have denied to Miss Crawford’s nature that participation of the general nature of women which would lead her to adopt the opinions of the man she loved and respected as her own. But as such were Fanny’s persuasions, she suffered very much from them, and could never speak of Miss Crawford without pain.

This sounds like an older, experienced voice bringing forth evidence for actual cases of 'improvement' witnessed by the narrator. Note that this argument about the general adaptability of women contradicts the possibility of Fanny 'improving' Henry.

I keep asking myself whether the narrator's caution on the subject is a genuine undecidedness, or intended to keep the reader asking the question, and speculating on the outcome?

If you know the book (view spoiler)

Very interesting framing, Sabagrey. Perhaps the outcome depends on individual personalities, as well as on circumstance. Malleable people might shape themselves to suit their partner while more self-willed people would stand firm on their own preferences. Or people might have some cathartic experience to shock them out of willfulness into a more collaborative approach to others.

Very interesting framing, Sabagrey. Perhaps the outcome depends on individual personalities, as well as on circumstance. Malleable people might shape themselves to suit their partner while more self-willed people would stand firm on their own preferences. Or people might have some cathartic experience to shock them out of willfulness into a more collaborative approach to others.The novelist Sherwood Smith has written an interesting take on the alternate ending, so deeply thought out that it almost convinced me, much as I prefer the road Austen took. I can’t give you the title because it’s too revealing. It starts from Henry’s proposal and goes on from there.

Edmund's 'reassurance' to Fanny over Henry's proposal makes my blood boil! He goes on and on saying how right she was and how she mustn't let herself be pushed into marriage against her will, and she's so relieved to have his support - and then he dashes it all to the ground by going "Let him succeed at last" and talking of how grateful she ought to be!

Edmund's 'reassurance' to Fanny over Henry's proposal makes my blood boil! He goes on and on saying how right she was and how she mustn't let herself be pushed into marriage against her will, and she's so relieved to have his support - and then he dashes it all to the ground by going "Let him succeed at last" and talking of how grateful she ought to be!I could slap him.

Abigail wrote: "writing all those letters to Fanny so that (1) her brother can inappropriately write to her and (2) Mary herself can inappropriately write to Edmund. No wonder Fanny found the correspondence “cruelly mortifying.” ."

I think this was a common ploy among young people with siblings who were friends with their lovers-that a correspondence would be entered into so that the letters could be read aloud and the lovers get news from each other, and if both couples had been in love it would have worked a treat in this case.

I think this was a common ploy among young people with siblings who were friends with their lovers-that a correspondence would be entered into so that the letters could be read aloud and the lovers get news from each other, and if both couples had been in love it would have worked a treat in this case.

Jenny wrote: "Edmund's 'reassurance' to Fanny over Henry's proposal makes my blood boil! He goes on and on saying how right she was and how she mustn't let herself be pushed into marriage against her will, and s..."

Jenny wrote: "Edmund's 'reassurance' to Fanny over Henry's proposal makes my blood boil! He goes on and on saying how right she was and how she mustn't let herself be pushed into marriage against her will, and s..."that's not the only dirty rhetoric trick he plays on Fanny in this chapter! I read it closely to find out exactly WHY I was so disgusted with Edmund. He's good at rhetorics - just as a clergy man should be!? - and Fanny is no match for him on that level. She's got nothing but stubbornness and distress left to her.

The paragraph where Edmund reacts to Fanny's accusations of Henry wrt Maria is a masterpiece of Austen's writing:

... let us not, any of us, be judged by what we appeared at that period of general folly. The time of the play is a time which I hate to recollect. Maria was wrong, Crawford was wrong, we were all wrong together; but none so wrong as myself. Compared with me, all the rest were blameless. I was playing the fool with my eyes open.

First generalise, then dilute, finally blame yourself, but only for foolishness, no more - no hint that he maybe had some responsibility for his sisters. ... Austen very deftly produces our disgust with Edmund in these paragraphs.

sabagrey wrote: "Jenny wrote: "Edmund's 'reassurance' to Fanny over Henry's proposal makes my blood boil! He goes on and on saying how right she was and how she mustn't let herself be pushed into marriage against her wishes

sabagrey wrote: "Jenny wrote: "Edmund's 'reassurance' to Fanny over Henry's proposal makes my blood boil! He goes on and on saying how right she was and how she mustn't let herself be pushed into marriage against her wishes…..that's not the only dirty rhetoric trick he plays on Fanny in this chapter! I read it closely to find out exactly WHY I was so disgusted with Edmund. He's good at rhetorics - just as a clergy man should be!? - and Fanny is no match for him on that level. She's got nothing but stubbornness and distress left to her.

The paragraph where Edmund reacts to Fanny's accusations of Henry wrt Maria is a masterpiece of Austen's writing:."

Good points Sabagrey and Jenny

Yes, like both of you, I was metaphorically punching the page at Edmund’s attack on Fanny, both for trying to be two-faced and for attempting to overcome her resolve by a specious ‘reasoned, rational, and unprejudiced’ argument.

In fact his infatuation with Mary has prejudiced everything he says to Fanny. It has reduced his relationship with her to a selfish and patronising ‘I know best’ attitude, rather than one of mutual respect and understanding.

Trev wrote: "In fact his infatuation with Mary has prejudiced everything he says to Fanny. It has reduced his relationship with her to a selfish and patronising ‘I know best’ attitude, rather than one of mutual respect and understanding."

Trev wrote: "In fact his infatuation with Mary has prejudiced everything he says to Fanny. It has reduced his relationship with her to a selfish and patronising ‘I know best’ attitude, rather than one of mutual respect and understanding."Infatuation is an explanation - but is it an excuse?

sabagrey wrote: "Trev wrote: "Infatuation is an explanation - but is it an excuse?..."

sabagrey wrote: "Trev wrote: "Infatuation is an explanation - but is it an excuse?..."He can have no excuse except a weakness in character.

Although, ‘losing your head’ over someone or something entirely unsuitable (and potentially life wrecking) is a weakness many people possess. It can end in disaster but on the other hand it may be cathartic.

One of the interesting things about the novel is that everyone in it has some “weakness in character,” although some are much worse than others. As a die-hard Dickensian, I still appreciate the more nuanced characters in this book. It will be interesting to discover if Edmund has a “come-to-realize” moment in which he learns that Fanny’s instincts are correct.

One of the interesting things about the novel is that everyone in it has some “weakness in character,” although some are much worse than others. As a die-hard Dickensian, I still appreciate the more nuanced characters in this book. It will be interesting to discover if Edmund has a “come-to-realize” moment in which he learns that Fanny’s instincts are correct.

sabagrey wrote: "that's not the only dirty rhetoric trick he plays on Fanny in this chapter!.."

sabagrey wrote: "that's not the only dirty rhetoric trick he plays on Fanny in this chapter!.."In fact, Edmund is saying "It was the play wot done it!" He is so consumed with guilt at having taken part in it that he's using the play itself as a scapegoat, not taking into consideration that he only did it because he was forced into it, as the only way he could think of to minimise the impropriety, for his sisters' sake and Mary's. He believes that he himself was behaving out of character and assumes that the others were too, whereas Henry at least was actually perfectly in character. As Fanny knows, having seen how he played Maria and Julia off each other on the visit to Sotherton, for example.

Fanny, by the way, has seen first hand the effects of marrying the wrong man in her own parents, hasn't she? It's not just that her mother didn't marry a rich man - she married a man with disastrous flaws of character who must have got worse rather than better over the years. She can't have much confidence that a wife can change her husband to her liking.

As a first-time reader of MP I can’t wait to see how this all plays out in the end! As Edmund looks worse and worse and Henry actually is looking a bit better, will Austen have Fanny end up with him after all? Will the squalid circumstances at Portsmouth lead her to realize the value of marrying money? I am totally hooked.

As a first-time reader of MP I can’t wait to see how this all plays out in the end! As Edmund looks worse and worse and Henry actually is looking a bit better, will Austen have Fanny end up with him after all? Will the squalid circumstances at Portsmouth lead her to realize the value of marrying money? I am totally hooked.I was heartbroken at the lack of warmth Fanny received at the hands of her mother (and father too, for that matter—he barely acknowledged her after all those years!).

But as for Henry—is he really that bad? His lack of “constancy” and flirtatiousness seem to be his main flaws. But he is also creative, smart, and puts a lot of thought into various areas that he’s interested in such as landscaping, rhetoric, drama, etc. Could the lack of constancy be due to having a multitude of interests, and being young? Also, could his flirtatiousness be closer to normative behavior in London society? While Austen does stress that Fanny’s unavailability increases her attractiveness to him, she also says that he truly loves her and appreciates her “finer” traits. Also, maybe the situation with the necklace was a very thoughtful gesture, not purely manipulative. Playing devil’s advocate here.

I think Sir Thomas means well. He is genuinely surprised that Fanny refused such an advantageous offer of marriage.

I think Sir Thomas means well. He is genuinely surprised that Fanny refused such an advantageous offer of marriage.He believes that she is young and doesn’t know what she wants and on a whim is rejecting the opportunity of a life time.

I think he is acting in what he believes is her best interest by attempting to change her mind.

I don’t blame him for that. He actually seems like a nice guy.

Henry Crawford just wants what he cannot have - I guess because he is spoiled and used to getting whatever he wants.

I don’t like him. He reminds me of other Jane Austen characters like Wickham from P&P and Willoughby from Sense and Sensibility.

I finally gave in and watched two of the film adaptations (the 1999 and 2007 ones) and I didn’t like either one.

They both make Fanny too pretty or too witty.

I’m really not a fan of any ‘modern adaptations’ - they all tend to include themes that were not in the book :/

All my favorite adaptations are from the mid 90s:

Pride and Prejudice 1995 mini series

Sense and Sensibility 1995

And Emma 1996

Ceane wrote: "As a first-time reader of MP I can’t wait to see how this all plays out in the end! As Edmund looks worse and worse and Henry actually is looking a bit better, will Austen have Fanny end up with hi..."

Ceane wrote: "As a first-time reader of MP I can’t wait to see how this all plays out in the end! As Edmund looks worse and worse and Henry actually is looking a bit better, will Austen have Fanny end up with hi..."Austen keeps us on tenterhooks, doesn't she? - Serial publication was not yet in fashion in her time, but just imagine if the novel had been published in instalments ... the readers' suspense, and their discussions! (maybe even their wagers? ;-))

Ceane wrote: "As for Henry - is he really that bad?..."

Ceane wrote: "As for Henry - is he really that bad?..."I believe he is, because it's not just that he's 'flirtatious' - he plays with other people's emotions for his own amusement and that is indefensible. Even his sister, who is trying to sell him to Fanny, admits that he 'likes to make women a little in love with him' without engaging his own emotions and we know that he was trying to do the same to Fanny, disregarding his sister's urging not to hurt her too much. He just didn't care whether he hurt her or not.

His part in wrecking Maria's relationship with Rushworth is indefensible too - OK, Maria didn't love Rushworth, but she was prepared to marry him and make the best of it because of his money and position. Henry's barging in and making her discontented with her fiance, while encouraging her to think she was about to get a better offer meant the marriage got off to the worst possible start - and playing Julia on the same line came between two sisters as well.

As for his interests ... how lasting are they? His supposed interest in landscaping didn't come to anything when it offered a chance to get Maria on her own. I can't help wondering if he isn't one of these people that take up enthusiasms and drop them.

As for the necklace - he should have known it was putting Fanny in a very difficult position. Gifts to a young single lady from a man not related to her were an absolute minefield with all sorts of implications for what people would assume about their relationship and for what each party was entitled to infer from the offering and the acceptance of them.

If he had truly meant just to help Fanny out he could have given it to Mary and told her to pretend it was hers without ever mentioning his involvement - and it's obvious that Mary herself regards it as a trick played on Fanny, as does the author. It's quite symbolic that the chain is much fancier than Fanny really liked, so as to be in competition with William's pendant, and anyway doesn't in the end fit through the ring.

Ana wrote: "I think Sir Thomas means well. He is genuinely surprised that Fanny refused such an advantageous offer of marriage.

Ana wrote: "I think Sir Thomas means well. He is genuinely surprised that Fanny refused such an advantageous offer of marriage.He believes that she is young and doesn’t know what she wants and on a whim is re..."

Of course, if Fanny had said why she did not want to marry Henry she could have saved everyone a whole lot of heart ache. And I mean everyone.

Jenny wrote: "Ceane wrote: "As for Henry - is he really that bad?..."

Jenny wrote: "Ceane wrote: "As for Henry - is he really that bad?..."I believe he is, because it's not just that he's 'flirtatious' - he plays with other people's emotions for his own amusement and that is ind..."

Excellent points all!

Jan wrote: "Of course, if Fanny had said why she did not want to marry Henry she could have saved everyone a whole lot of heart ache. And I mean everyone."

Jan wrote: "Of course, if Fanny had said why she did not want to marry Henry she could have saved everyone a whole lot of heart ache. And I mean everyone."She could tell everyone her good reasons (for what it is worth - they try to persuade her nonetheless, see Edmund) - but she could not well tell her real reason.

sabagrey wrote:

sabagrey wrote: She could tell everyone her good reasons (for what it is worth - they try to persuade her nonetheless, see Edmund) - but she could not well tell her real reason. .."

Well stated Sabagrey. And I can reinforce that by using a quote from the author, who surely can’t be a hypocrite.

Her own cousin Fanny (Knight) asked her aunt Jane for some advice about courtship and matrimony.

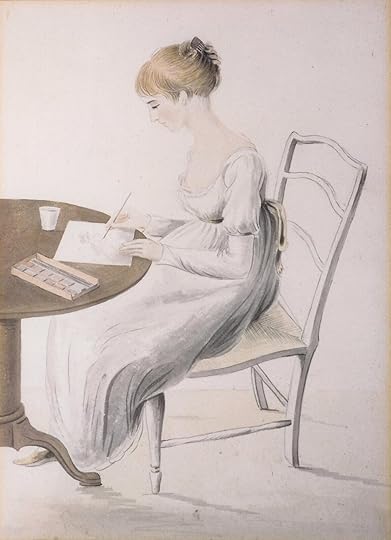

Here is the extract from the Jane Austen House museum.

’ Fanny, the subject of the drawing, was the eldest of Jane Austen’s many nieces and nephews and the first of eleven children born to Jane’s third brother Edward and his wife Elizabeth. Jane was just 17 years old and Cassandra 20 when Fanny was born. Fanny was very close to her Aunts when young; in a letter from Jane to Cassandra in October 1808, Jane wrote:

‘I am greatly pleased with your account of Fanny; I found her in the summer just what you describe, almost another Sister, & could not ever have supposed that a neice (sic) would ever have been so much to me.’

Fanny’s life was to be one of maternal responsibilities. When her mother died in 1808, Fanny became at the age of 15 a mother substitute for her 10 younger siblings. On her marriage to the widowed Sir Edward Knatchbull in 1820, she became step-mother to the six children from his first marriage and went on to have 9 children of her own.

In her early 20’s Fanny sought advice from her Aunt Jane about a suitor; in a letter dated November 1814, Jane advised her niece that:

‘Anything is to be preferred or endured rather than marrying without Affection.’

In Pride and Prejudice, Austen has Jane Bennett give very similar advice to Lizzy when she reveals her love for Darcy:

‘Oh, Lizzy! Do anything rather than marry without affection.’

It seems likely that Jane applied this maxim to her own life, in particular her short-lived engagement to Harris Bigg-Wither.’

https://janeaustens.house/object/wate...

sabagrey wrote: "Jan wrote: "Of course, if Fanny had said why she did not want to marry Henry she could have saved everyone a whole lot of heart ache. And I mean everyone."

sabagrey wrote: "Jan wrote: "Of course, if Fanny had said why she did not want to marry Henry she could have saved everyone a whole lot of heart ache. And I mean everyone."She could tell everyone her good reasons..."

She's also a bit stuck because she doesn't want to grass up Maria and Julia by revealing what she saw going on between Henry and them. If she's believed, it reflects badly on their reputations and if she's not she looks like a b*tch. She does, cautiously, try to tell Edmund, but he just brushes it aside; and doesn't feel she can possibly say anything to Sir Thomas - he asks if she's got anything against Henry's temperament and has to say "No", but wishes she could say "But against his principles I have".

You can see Sir Thomas's point - on the surface Henry looks like any girls' dream, especially as he believes Mary to be Fanny's 'intimate friend'. He has good reason to be genuinely baffled and to wonder how on earth Fanny might think she could do better - and to be shocked, in this age when 'connections' were all-important, that she's unwilling to take a step so potentially beneficial to her hard-pressed family.

I’m in the camp that judges Henry harshly. I can’t see the necklace episode in any positive light; it seems all of a piece with his tactics, which we also see in the matter of William’s promotion. He may have liked William, but would he really have taken so much trouble about it if he hadn’t been motivated by a desire to make Fanny feel grateful to him? Engineering gratitude is a classic coercion tactic; it makes it so hard for the beneficiary to meet you on an equal basis, bleeding gratitude over into a sense of obligation. For a shy person like Fanny it would have been torture. I am constantly reminded of a quote from Middlemarch: “Obligation may be stretched till it is no better than a brand of slavery stamped on us when we were too young to know its meaning.” I feel that kind of sentiment was very much in Austen’s mind when shaping this story.

I’m in the camp that judges Henry harshly. I can’t see the necklace episode in any positive light; it seems all of a piece with his tactics, which we also see in the matter of William’s promotion. He may have liked William, but would he really have taken so much trouble about it if he hadn’t been motivated by a desire to make Fanny feel grateful to him? Engineering gratitude is a classic coercion tactic; it makes it so hard for the beneficiary to meet you on an equal basis, bleeding gratitude over into a sense of obligation. For a shy person like Fanny it would have been torture. I am constantly reminded of a quote from Middlemarch: “Obligation may be stretched till it is no better than a brand of slavery stamped on us when we were too young to know its meaning.” I feel that kind of sentiment was very much in Austen’s mind when shaping this story.Very interesting discussion in this thread about different characters’ flaws and how their weaknesses drive their perceptions and the story.

I just wish Fanny had more weaknesses. The only thing I see is her reluctance to tell Henry off instead of politely avoiding him and quietly refusing his offer. She is never fooled. She understands all the games the others are playing. This is probably realistic given her position in the household, but to me it makes her tedious to read about.

Jan wrote: "I think Fanny crosses the line from having good judgment to being judgmental."

Jan wrote: "I think Fanny crosses the line from having good judgment to being judgmental."It's fascinating how a fictional character, created over 200 years ago, can touch a string in us.

sabagrey wrote: "Jan wrote: "I think Fanny crosses the line from having good judgment to being judgmental."

sabagrey wrote: "Jan wrote: "I think Fanny crosses the line from having good judgment to being judgmental."It's fascinating how a fictional character, created over 200 years ago, can touch a string in us."

Perhaps Fanny touches a string in us (or strikes a chord in others) because her situation is so universal—how do you define yourself in a world where others are all defining you? How do you carve out space for yourself? Where do you find your power when your position is one of powerlessness? What is meaningful to you, what makes you, you? We all face these issues in one way or another when we’re 18.

Abigail wrote: "Perhaps Fanny touches a string in us (or strikes a chord in others) because her situation is so universal - how do you define yourself in a world where others are all defining you?..."

Abigail wrote: "Perhaps Fanny touches a string in us (or strikes a chord in others) because her situation is so universal - how do you define yourself in a world where others are all defining you?..."Yes, absolutely! Fanny is terribly handicapped in her powerlessness by the lack of self-confidence that has been instilled in her - something that Lizzy, or Elinor or even Anne don't have to deal with.

Somehow, from deep down Fanny finds the courage and resolution to refuse to marry Henry, and then in Portsmouth she discovers that she has it in herself to become a mentor to her sister Susan as Edmund had been to her - and that's the beginning of her growth. She discovers that she can do this - she may have been on the point of caving in over Cottager's Wife, but now, with more at stake she finds her strength.

I don't know what Jan means by accusing Fanny of being 'judgmental' - surely we're all entitled to think what we think of other people's behaviour? And to be wary of making friends with, let alone marrying, someone whose values so conflict with our own?

Fanny doesn't go round snitching and slagging off - she only discusses Mary's and the Admiral's behaviour with Edmund because he brings the matter up, almost like a teacher questioning a pupil on what they've learnt, and I think it's Mary and Edmund together who vilify Doctor Grant and encourage Fanny to do likewise. We never see her putting down her cousins, or even her aunts, and she only mentions Mrs Norris's name in connection with her lack of fire because Sir Thomas practically forces it out of her. She only speaks of her trials at Mrs Norris's hands with William, in private, and I don't think she can be blamed for that. It's her reluctance to show Maria and Julia in a bad light that makes it so difficult for her to explain herself to Sir Thomas, and causes a real problem for her.

Basically she has all the Christian virtues- humility, compassion, kindness, honesty plus a clear perception of others. Most of her judgment stays inside her head. She is just too perfect for me.

Fanny is almost like a thought experiment of what happens when a character of total goodness has no worldly power except over herself.

Fanny is almost like a thought experiment of what happens when a character of total goodness has no worldly power except over herself.

Ben wrote: "Fanny is almost like a thought experiment of what happens when a character of total goodness has no worldly power except over herself."

Ben wrote: "Fanny is almost like a thought experiment of what happens when a character of total goodness has no worldly power except over herself."this is an interesting expression ... makes me think that every fictional character starts out as the author's thought experiment.

Ben wrote: "Fanny is almost like a thought experiment of what happens when a character of total goodness has no worldly power except over herself."

Ben wrote: "Fanny is almost like a thought experiment of what happens when a character of total goodness has no worldly power except over herself."YES! That's it, absolutely.

Robin P wrote: "Basically she has all the Christian virtues- humility, compassion, kindness, honesty plus a clear perception of others. Most of her judgment stays inside her head. She is just too perfect for me."

Robin P wrote: "Basically she has all the Christian virtues- humility, compassion, kindness, honesty plus a clear perception of others. Most of her judgment stays inside her head. She is just too perfect for me."Do you feel the same about other 'good' Austen heroines? Elinor Dashwood or Anne Elliott?

I like Elinor and Anne. They are introverts but very different from Fanny. They need to acknowledge their flaws and do some soul searching. And they are much more active participants in their stories. Elinor manages the family 's finances. Anne translates opera, manages the crisis at Lyme, takes care of her sister's sick kid.

I like Elinor and Anne. They are introverts but very different from Fanny. They need to acknowledge their flaws and do some soul searching. And they are much more active participants in their stories. Elinor manages the family 's finances. Anne translates opera, manages the crisis at Lyme, takes care of her sister's sick kid.

I agree, Anne and Elinor have more spunk. But it’s not Fanny being quiet or passive that bothers me, It’s that she is ALWAYS right. Elinor and Anne are both deceived at times. Fanny sees through everything that Henry and Maria do, and the depth of Edmund’s infatuation. She doesn’t go around telling people all the things she has observed, though she tries to warn them and to set a good example. This is admirable in a real person but so uninteresting to read about. She doesn’t do anything unpredictable and there is no humor around her. The whole book is quite humorless for an Austen novel. The humor that does exist is rather dark satire by the narrator on social climbing and hypocrisy. If this book were by Dickens or some other author, I would accept Fanny as one of many sweet, devoted girls. But I expect something different from Austen. Maybe in her maturity, Austen wanted to address issues in a more serious way.

I don’t really see her as sweet and always right, at least on the inside. Inside there’s a lot of conflict and even aggression. (Warning: some of these quotes are from the next section, though I don’t think they reveal plot points.) “She was, she felt she was, in the greatest danger of being exquisitely happy, while so many were miserable. The evil which brought such good to her!” “She must have been a happy creature in spite of all that she felt, or thought she felt, for the distress of those around her.” “She was within half a minute of starting the idea, that Sir Thomas was quite unkind, both to her aunt and to herself.” “It was barbarous to be happy when Edmund was suffering. Yet some happiness must and would arise, from the very conviction that he did suffer.” “She had been feeling neglected, and been struggling against discontent and envy for some days past.” Yes, she sees people’s true natures and motives, but she’s hardly a Candide, she’s full of roiling negative emotions so powerful they affect her physically.

I don’t really see her as sweet and always right, at least on the inside. Inside there’s a lot of conflict and even aggression. (Warning: some of these quotes are from the next section, though I don’t think they reveal plot points.) “She was, she felt she was, in the greatest danger of being exquisitely happy, while so many were miserable. The evil which brought such good to her!” “She must have been a happy creature in spite of all that she felt, or thought she felt, for the distress of those around her.” “She was within half a minute of starting the idea, that Sir Thomas was quite unkind, both to her aunt and to herself.” “It was barbarous to be happy when Edmund was suffering. Yet some happiness must and would arise, from the very conviction that he did suffer.” “She had been feeling neglected, and been struggling against discontent and envy for some days past.” Yes, she sees people’s true natures and motives, but she’s hardly a Candide, she’s full of roiling negative emotions so powerful they affect her physically.

I agree, she's not a Pollyanna/Candide figure, she sees everything realistically. I think her emotions aren't out of line for the situation. She doesn't speak them out loud but they are another reflection of her awareness.

I suspect any humour in Fanny would have been quickly nipped by Mrs Norris or even by her cousins as being unseemly and "low". I suspect she was told not to cry or giggle or put herself forward in any way so that she learned very young to hide her emotions.

I actually find Fanny much less annoying than Elinor Dashwood. I found her pretty insufferable on my last read through.

I actually find Fanny much less annoying than Elinor Dashwood. I found her pretty insufferable on my last read through.

Frances wrote: "I suspect any humour in Fanny would have been quickly nipped by Mrs Norris or even by her cousins as being unseemly and "low". I suspect she was told not to cry or giggle or put herself forward in ..."

Frances wrote: "I suspect any humour in Fanny would have been quickly nipped by Mrs Norris or even by her cousins as being unseemly and "low". I suspect she was told not to cry or giggle or put herself forward in ..."I suspect being witty was Tom's role in the family and his juniors were expected to leave him to it! But the general lack of it among the Bertrams - apart from Tom - does make the Crawfords seem more sparkling and attractive, doesn't it?

Emily wrote: "I actually find Fanny much less annoying than Elinor Dashwood. I found her pretty insufferable on my last read through."

Emily wrote: "I actually find Fanny much less annoying than Elinor Dashwood. I found her pretty insufferable on my last read through."Margaret was always my favorite Dashwood sister and S&S is not my favorite JA (#5 above MP). I did see a stage production of it were the emphasis was on the relationship between Elinor and Marianne and I loved it.

William returns in triumph, having received his promotion and getting ready to sail out soon. Sir Thomas offers Fanny the opportunity to return to visit her family and to see William in all his finery (which he cannot wear outside of Portsmouth), with the hidden purpose of reminding Fanny what life might be like away from the luxuries of Mansfield Park and/or an advantageous marriage. Fanny is delighted to have this chance to visit her family, not seen in 0ver 10 years now, and she and William make an enjoyable trip home together. Home, however, is not all that Fanny had hoped. She is somewhat neglected, the house is small and cramped and ill-managed, and her father is coarse and uninterested in her. Sir Thomas' plan may well succeed.

What did you think of Henry's style of wooing? For those who haven't read this already, do you think he has changed and could ultimately be successful with Fanny?

What about Edmund's renewed interest in Mary? What did you think of his encouraging Fanny to accept Henry Crawford?

William expresses some vague hopes that Fanny could help regulate the household in Portsmouth and better instruct the younger children-do you think this is something that Fanny could do?

Austen has some interesting comments on the very different spheres that sisters could end in, and how Mrs Price would likely have done quite well in Lady Bertram's position, and that Mrs Norris would have been more successful in Mrs Price' place. How do you think Fanny would have turned out if she had remained at home all this time?

Please post your thoughts on this section and our novel so far.