Dickensians! discussion

This topic is about

Oliver Twist

Oliver Twist - Group Read 5

>

Oliver Twist: Chapters 18 - 25

Furniss does really well at depicting Oliver as a near iconic innocent beleaguered by leering malevolent presences: i.e. ch 7, ch 16, ch 19.

Furniss does really well at depicting Oliver as a near iconic innocent beleaguered by leering malevolent presences: i.e. ch 7, ch 16, ch 19.

I am wondering what will happen next. As you say, we modern readers can see how much of the book remains so we know there’s a lot left to happen. It must have been very thrilling and scary to read in Dickens’ day.

I am wondering what will happen next. As you say, we modern readers can see how much of the book remains so we know there’s a lot left to happen. It must have been very thrilling and scary to read in Dickens’ day.

Lori wrote: "I think maybe the better question is how Dickens is inspired by Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress in creating Oliver’s Progress ..."

Yes, the allusion to John Bunyan is slightly puzzling. I think we may be able to deduce from this that if Charles Dickens had wound up the serial much earlier, as part of "Bentley's Miscellany", then perhaps it would have gone a different way. After all, it was originally called "The Parish Boy's Progress", so this must have been intentional.

Yes, the allusion to John Bunyan is slightly puzzling. I think we may be able to deduce from this that if Charles Dickens had wound up the serial much earlier, as part of "Bentley's Miscellany", then perhaps it would have gone a different way. After all, it was originally called "The Parish Boy's Progress", so this must have been intentional.

Werner (and Lori) - Maybe that's me reading too much into the text then ... although when you say "the idea of the comparison is that it will be unexpected," ... (and I've stopped short of the next part. When we have read a little more, we need to revisit this idea!)

message 106:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 02, 2023 12:50PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Erich - "The stories that end with a hanging and gibbet would represent a sort of crucifixion/martyrdom" - Oh my goodness, a sort of thieves "Holy Book". How appalling! I'm sure you're on to something here 😊

Bionic Jean wrote: "Lori wrote: "I think maybe the better question is how Dickens is inspired by Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress in creating Oliver’s Progress ..."

Bionic Jean wrote: "Lori wrote: "I think maybe the better question is how Dickens is inspired by Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress in creating Oliver’s Progress ..."Yes, the allusion to John Bunyan is sligh..."

That’s true, Jean. I must apologize because my response sounds as if I didn’t think your question about Oliver as a Christ figure was a good one. That wasn’t my intention at all. I was thinking about the original title and was trying to figure out what the two stories have in common. There must have been some intent at the beginning. I remember that Bunyan wrote an apology for his story giving a reason, I guess, for how it came to be while he was writing another book. It brought to mind the beginning of chapter 17 when Dickens seems to be giving his own apology. We talked about the strangeness of that section and now, it seems that maybe he was doing the same as Bunyan. And that he was realizing that Oliver was going to become a full novel at that point.

I will certainly keep an open mind about Oliver’s possible sacrifice as we continue!

No need to apologise at all Lori! All interpretations are interesting, and with this one where the history is so chequered, a lot is open to question.

Charles Dickens must surely have wished he could edit some things at the beginning. The tone after he decided to take back his resignation and continue, is so very different, for a start!

Charles Dickens must surely have wished he could edit some things at the beginning. The tone after he decided to take back his resignation and continue, is so very different, for a start!

Bionic Jean wrote: "Sue and Susan - Yes, I agree. 🙄 In fact the point about Oliver's reading bothers me every time I read Oliver Twist!"

Bionic Jean wrote: "Sue and Susan - Yes, I agree. 🙄 In fact the point about Oliver's reading bothers me every time I read Oliver Twist!"It could be an oversight by a younger writer. I remember in Dickens' later novel Bleak House it's explicitly mentioned that Jo, the street sweeper, who would be of a similar socioeconomic class as Oliver, is illiterate.

Erich C wrote: "As I read, I imagine her as a fairly fresh-looking young woman, someone who can pass for a respectable person when she needs to, as when she is sent with her apron, basket, and key to retrieve Oliver in an earlier chapter."

Also, not to put too fine a point on it, a young, pretty girl would be a better "product." I don't see Fagin and co. as being a particularly high-class operation, even in their own context, though...

As a minor side note, I do appreciate the lack of explicitness on some subjects in OT. It isn't prudery on my part but appreciation for an author who can allow more mature readers to draw their own inferences about what's going on, that would go over a less jaded reader's head.

Beth wrote: "Furniss does really well at depicting Oliver as a near iconic innocent beleaguered by leering malevolent presences: i.e. ch 7, ch 16, ch 19."

Quoting myself to note that this is also true of his illustration for ch 22. :)

Lori wrote: "I think maybe the better question is how Dickens is inspired by Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress in creating Oliver’s Progress. Christian’s story was a spiritual journey which led to salvation..."

Lori wrote: "I think maybe the better question is how Dickens is inspired by Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress in creating Oliver’s Progress. Christian’s story was a spiritual journey which led to salvation..."Thank you for this reminder, Lori! I had forgotten that Dickens added the subtitle Or, The Parish Boy's Progress to the title Oliver Twist. Having just finished John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress a few months ago, it is still fresh in my mind.

I can definitely see how Dickens would have compared Oliver's journey to Christian's. In Christian's journey, as you say, he was on a spiritual journey which led to salvation. Along the way, Christian met with many adversaries who tried to tempt him and lead him astray. I don't know why I didn't think about it before your comment, Lori, but this is exactly what Oliver is experiencing. Somehow, through all of the tribulations he has faced in his young life, Oliver has been able to maintain innocence and goodness to what he hopes will be a better life. His obstacles, like Christian, have been many (Mr. Bumble, Mrs. Mann, Mrs. Sowerberry, and of course, the den of thieves). But through it all, Oliver has been able to maintain his moral compass, as young as he is. I can't wait to see if Oliver reaches his goal.

I love the comments and posts. Everyone is helping me think about this novel in so many different ways. Just a general comment here overall, but I think one of the best attributes of Dickens is to create each chapter as if it were a story with a small cliffhanger to finish to each chapter. Dickens was so superb at writing in that installment fashion like today's miniseries. I think that is what I really admire about his writing so much. It piques our interest to see what is to come....

I love the comments and posts. Everyone is helping me think about this novel in so many different ways. Just a general comment here overall, but I think one of the best attributes of Dickens is to create each chapter as if it were a story with a small cliffhanger to finish to each chapter. Dickens was so superb at writing in that installment fashion like today's miniseries. I think that is what I really admire about his writing so much. It piques our interest to see what is to come....

I very much enjoyed reading all your posts.

I very much enjoyed reading all your posts.Talking about sacrifice, I thought, in a way, of Genesis 22. It describes what Christians churches frequently call Abraham's Sacrifice, i.e. Abraham is tested by God and brings his son Isaac to Mount Moriah very early in the morning for offering him as a sacrifice. The father carries a knife, the son wood for a fire. It is called in Judaism "Akedat Yitzhak" (the ligature of Isaac). Yitzhak (literally "he will laugh", but there is nothing to laugh here) is tied on the altar on the wood but at the last moment an angel of God appears and tells Abraham to untie him, as he has proven his faith to that extremity of sacrificing his beloved only son (he has formerly sent Hagar with Ishmael away). A ram conveniently appears to be sacrificed in Isaac's stead. (we saw mutton heads formerly mentioned)

We do have a few ingredients here: Sykes is mistaken for Oliver's father. He takes advantage of this, but he is only a mock father. They are walking in the dead of night and Oliver is scared, not knowing where he is led to, but being kept aware of the pistol in Sykes' pocket. Just like Isaac asks his father where is the ram for the sacrifice, but unaware of where they go alone and entirely trustful. (there are plenty of Rabbinic comments but also many Bible study discussions on this)

Oliver is not physically tied but knows that he cannot escape and thinks that his last hour has come. Of course each action ends up very differently.

Although this may sound a little far-fetched, I nevertheless saw a few similarities between both passages. I would not peremptorily say that Dickens had Abraham and Isaac in mind then, but still our Victorian writers were familiar with Old Testament histories.

Regardless of any possible symbolism, it says a great deal about Oliver's character that he wants to warn the people in the house at great risk to himself, even as the crooks have a gun trained on him! He cares even more about others than he does about himself.

Regardless of any possible symbolism, it says a great deal about Oliver's character that he wants to warn the people in the house at great risk to himself, even as the crooks have a gun trained on him! He cares even more about others than he does about himself.As Bridget, I was really taken with the long description in the prior chapter as he enters the city, wonderfully evocative with appeals to all the senses of sight, hearing, touch, smell, and even taste. I feel like I can smell that steam rising from the "reeking bodies" of the cattle, even though I have never had a sense of smell since birth, and I feel like I can hear all those varied elements of the "discordant din".

It's interesting that Sikes often refers to Oliver as "perverse" when in fact he's only refusing to do what is perverse; the world of the robbers is topsy turvy, seeing goodness in evil and evil in goodness.

Poor Oliver at the end of this chapter! I assume he'll be ok as there are many pages to go in the book, but it must have been quite thrilling in installments when there was no way to know how much more was to come.

This installment, in three chapters, reads more like one chapter. I assume that he broke it into three chapters as he thought it might be a bit too long for two. The chapter breaks did not feel natural.

This installment, in three chapters, reads more like one chapter. I assume that he broke it into three chapters as he thought it might be a bit too long for two. The chapter breaks did not feel natural.When Oliver and Sykes are walking through London, in the early morning hours, I thought of the many late nights and early mornings that Dickens walked through those streets. His writing is realistic because he has been there, and really knew, first hand, their sights and sounds.

"Speaking of a crown, below is a photo of a 1892 crown, part of my Victorian coin collection, with a US quarter and 1 Euro coin as comparisons. Yes quite a big chunk of silver."

"Speaking of a crown, below is a photo of a 1892 crown, part of my Victorian coin collection, with a US quarter and 1 Euro coin as comparisons. Yes quite a big chunk of silver."Thank you, Michael for the photo of the crown in your coin collection! Being from the US, the English system of currency continues to confuse me, in spite of Bionic Jean's explanations. This crown shown is not only beautiful, it is quite substantial.

Sue wrote: "As a novice to this story, I just have to say I’m very interested to see where this is going. I really have no idea of its route as I haven’t even seen any production or film (except to have hints ..."

Sue wrote: "As a novice to this story, I just have to say I’m very interested to see where this is going. I really have no idea of its route as I haven’t even seen any production or film (except to have hints ..."I do envy you as you discover Oliver Twist for the first time!

Lee, it is fun to discover Oliver for the first time with only small bits of prior knowledge, mostly from ads for movies or shows. There’s never anything like the original book.

Lee, it is fun to discover Oliver for the first time with only small bits of prior knowledge, mostly from ads for movies or shows. There’s never anything like the original book.

message 118:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 05, 2023 05:53AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Franky - "I think one of the best attributes of Dickens is to create each chapter as if it were a story with a small cliffhanger to finish to each chapter.

Yes, it is masterful, isn't it ! Such control. When Charles Dickens edited his chapters for each new edition, he sometimes added a few words; a couple of sentences so that he could break it in a different place. Sometimes we can see other little cliffhangers too, but the ones at the end of each installment are very powerful indeed. Charles Dickens manipulates us beautifully.

Yes, it is masterful, isn't it ! Such control. When Charles Dickens edited his chapters for each new edition, he sometimes added a few words; a couple of sentences so that he could break it in a different place. Sometimes we can see other little cliffhangers too, but the ones at the end of each installment are very powerful indeed. Charles Dickens manipulates us beautifully.

message 119:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 05, 2023 07:19AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Beth - I'm glad you are enjoying Harry Furniss's illustrations. I know that Sara admires them a lot too.

I include them when I can, as I feel they capture the older Charles Dickens's view of his own early novel, even though they were drawn in 1910, i.e. well after his death and more than 70 years after Oliver Twist was written. But Harry Furniss's have an artistic flair, and capture the emotion well, (as you observe 😊), whereas Charles Dickens's original choice, George Cruikshank brought out the humour, and the caricatures. He had the benefit of Charles Dickens's instructions, but then Harry Furniss had the benefit of hindsight, and of having access to the entire novel!

I have added another one by him to the chapter 22 summary - it is very dramatic and worth looking at! (It was wrongly catalogued as being in chapter 28. 🙄 As if it's not tricky enough with chapters ending in different places ... this was clearly just a mistake. There are many such mistakes in the "Victorian Web", but I can usually catch them in time.)

Oh, but it's hardly possible that it was an "oversight" that Oliver can read. It's essential to the plot, and not just a minor slip as all authors might make. So it was quite deliberate on Charles Dickens's part. He knew the facts well, already, both of the law and of education provision. Neither did he have a privileged upbringing, but mixed with working people from an early age. Think of his time in the blacking factory, where the other illiterate boys teased him for his "gentlemanly" air. Charles Dickens continued to spent a lot of time with the poor, and would not have made a mistake. He was already active and making a difference; John Forster details a lot of his work and campaigning in this area, in our side read of The Life of Charles Dickens, Vol. 1. (Not so much in the second two volumes.)

The difficulty is for us, to make sure we are reading this novel in the right way, and are not just expecting a straightforward story. It's no use blaming the author. As Sam said, there is very little here to show that it is such an early novel. Lori mentioned that she finds it tricky to remember that this is a allegory, and I think we all do. We need to continually do a "double think" as we read. London's underworld is rooted in reality, and the descriptions are authentic, but Oliver is partly an ideal. Just look at his speech! But often his psychology is truthful, and our belief in him carries us along, until we read a part which makes us pause and think.

Jo in Bleak House has a very different function, and Charles Dickens quite deliberately wrote Jo's speech phonetically, as he wanted Jo to be an authentic street sweeper. He could have down this quite easily for Oliver too, as the dialect was familiar to him, but in 1837 when it was so new, he did not want to alienate his middle class readers, (and he had another object in mind).

Do have a look at our discussions of Bleak House, as there is huge amount about Jo there, his literary purpose in the book, and also the real street sweeper whom Charles Dickens befriended, cared for, had educated and sent to Australia.

I include them when I can, as I feel they capture the older Charles Dickens's view of his own early novel, even though they were drawn in 1910, i.e. well after his death and more than 70 years after Oliver Twist was written. But Harry Furniss's have an artistic flair, and capture the emotion well, (as you observe 😊), whereas Charles Dickens's original choice, George Cruikshank brought out the humour, and the caricatures. He had the benefit of Charles Dickens's instructions, but then Harry Furniss had the benefit of hindsight, and of having access to the entire novel!

I have added another one by him to the chapter 22 summary - it is very dramatic and worth looking at! (It was wrongly catalogued as being in chapter 28. 🙄 As if it's not tricky enough with chapters ending in different places ... this was clearly just a mistake. There are many such mistakes in the "Victorian Web", but I can usually catch them in time.)

Oh, but it's hardly possible that it was an "oversight" that Oliver can read. It's essential to the plot, and not just a minor slip as all authors might make. So it was quite deliberate on Charles Dickens's part. He knew the facts well, already, both of the law and of education provision. Neither did he have a privileged upbringing, but mixed with working people from an early age. Think of his time in the blacking factory, where the other illiterate boys teased him for his "gentlemanly" air. Charles Dickens continued to spent a lot of time with the poor, and would not have made a mistake. He was already active and making a difference; John Forster details a lot of his work and campaigning in this area, in our side read of The Life of Charles Dickens, Vol. 1. (Not so much in the second two volumes.)

The difficulty is for us, to make sure we are reading this novel in the right way, and are not just expecting a straightforward story. It's no use blaming the author. As Sam said, there is very little here to show that it is such an early novel. Lori mentioned that she finds it tricky to remember that this is a allegory, and I think we all do. We need to continually do a "double think" as we read. London's underworld is rooted in reality, and the descriptions are authentic, but Oliver is partly an ideal. Just look at his speech! But often his psychology is truthful, and our belief in him carries us along, until we read a part which makes us pause and think.

Jo in Bleak House has a very different function, and Charles Dickens quite deliberately wrote Jo's speech phonetically, as he wanted Jo to be an authentic street sweeper. He could have down this quite easily for Oliver too, as the dialect was familiar to him, but in 1837 when it was so new, he did not want to alienate his middle class readers, (and he had another object in mind).

Do have a look at our discussions of Bleak House, as there is huge amount about Jo there, his literary purpose in the book, and also the real street sweeper whom Charles Dickens befriended, cared for, had educated and sent to Australia.

message 120:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 05, 2023 06:17AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Kathleen - "This installment, in three chapters, reads more like one chapter. I assume that he broke it into three chapters as he thought it might be a bit too long for two."

Good close observation of the text 😊 If you remember, I linked to a scholarly article which attempts to show all the different divisions in the many editions. Here, the evidence is partly in the urgency of the continuous action, as you say, and also by the brevity of the chapter titles for chapter 21 and 22, as I mentioned, which were probably added later. Chapter 20 though is separate; a different location and feel. Some readers had complained that Bill Sikes's journey with Oliver was too long and dragged, which perhaps explains the split.

Good close observation of the text 😊 If you remember, I linked to a scholarly article which attempts to show all the different divisions in the many editions. Here, the evidence is partly in the urgency of the continuous action, as you say, and also by the brevity of the chapter titles for chapter 21 and 22, as I mentioned, which were probably added later. Chapter 20 though is separate; a different location and feel. Some readers had complained that Bill Sikes's journey with Oliver was too long and dragged, which perhaps explains the split.

message 121:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 05, 2023 06:17AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Claudia - I very much enjoyed your thoughtful post on possible parallels in the Old Testament, regarding sacrifice. Thank you!

I would love to respond to all these great comments, but think it is probably time to move on 😊

I would love to respond to all these great comments, but think it is probably time to move on 😊

message 122:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 05, 2023 02:42PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Installment 11

Chapter 23:

"The night was bitter cold … The snow lay on the ground, frozen into a hard thick crust … Bleak, dark, and piercing cold, it was a night for the well-housed and fed to draw round the bright fire."

Back in the workhouse where Oliver Twist had been born, Mrs. Corney, the matron of the workhouse, has just made herself a pot of tea. Mrs. Corney is feeling sorry for herself as “a poor desolate creature” and remembering the loss of her husband who has been dead for more than 25 years, when Mr. Bumble stops by.

““Oh, come in with you!” said Mrs. Corney, sharply. “Some of the old women dying, I suppose. They always die when I’m at meals.””

They speak about how ungrateful and greedy the paupers under their care are, and how thankful the poor should be of the efforts made for them by government agencies. Mr. Bumble tells Mrs. Corney about one man who said he would die in the streets without food, so he was sent out a pound of potatoes and half a pint of oatmeal, only to object that it was of no use to him. The beadle comments:

“he went away; and he diddie in the streets. There’s a obstinate pauper for you! … out-of-door relief, properly managed … is the porochial safeguard. The great principle of out-of-door relief is, to give the paupers exactly what they don’t want; and then they get tired of coming.”

But he warns that these are “official secrets, ma’am; not to be spoken of; except … among the porochial officers, such as ourselves.”

"Mr. Bumble and Mrs. Corney" Sol Eytinge Jr. 1867

Mr. Bumble then gives Mrs. Corney two bottle of port wine which have been sent for the infirmary, and picks up his hat to leave. However when Mrs. Corney offers him a cup of of tea, he accepts with alacrity, and what follows is a very tender flirting scene, which shows that (as the narrator says in the title) “even a beadle may be susceptible on some points.”

There is significant talk of sweets, and cats, and then Mr. Bumble grasps the nettle, saying:

“any cat, or kitten, that could live with you, ma’am, and not be fond of its home, must be a ass, ma’am.”

and gradually inches his chair closer and closer to Mrs. Corney’s.

"Mr. Bumble and Mrs. Corney" - Harry Furniss 1910

"Mr. Bumble and Mrs. Corney taking tea" - George Cruikshank 1838

Since she makes no objection, he becomes bolder and kisses her. Mrs. Corney pretends to protest, for form’s sake that she will scream, but at that moment there is a knock on the door, whereupon:

“Mr. Bumble darted, with much agility, to the wine bottles, and began dusting them with great violence: while the matron sharply demanded who was there.”

The door opens, and a “withered old female pauper, hideously ugly” puts her head in to say that "Old Sally" is about to die and has asked for the matron. Indeed, the pauper says, she will not die until she has seen Mrs. Corney, and told her what is on her mind. Mrs. Corney is not pleased:

“the worthy Mrs. Corney muttered a variety of invectives against old women who couldn’t even die without purposely annoying their betters”

but leaves with the pauper, with a very ill grace, telling her off all the time.

Left on his own to wait for her return, Mr. Bumble expresses delight as he takes an inventory of Mrs. Corney’s silver and furnishings.

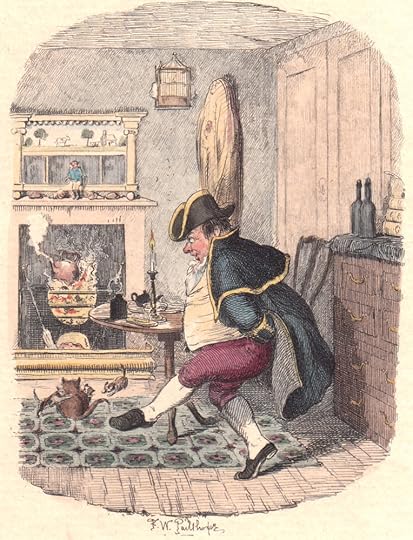

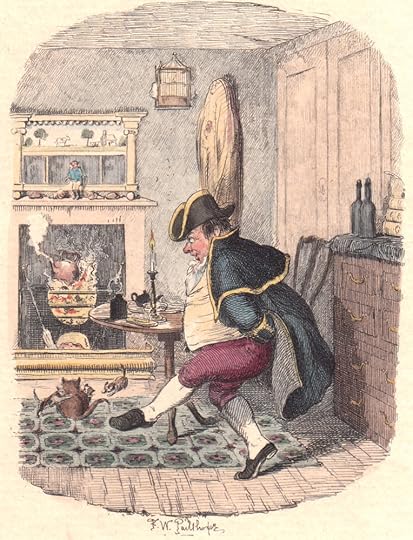

"Inexplicable conduct of Mr. Bumble when Mrs. Corney left the room" - F.W. Pailthorpe 1885

Chapter 23:

"The night was bitter cold … The snow lay on the ground, frozen into a hard thick crust … Bleak, dark, and piercing cold, it was a night for the well-housed and fed to draw round the bright fire."

Back in the workhouse where Oliver Twist had been born, Mrs. Corney, the matron of the workhouse, has just made herself a pot of tea. Mrs. Corney is feeling sorry for herself as “a poor desolate creature” and remembering the loss of her husband who has been dead for more than 25 years, when Mr. Bumble stops by.

““Oh, come in with you!” said Mrs. Corney, sharply. “Some of the old women dying, I suppose. They always die when I’m at meals.””

They speak about how ungrateful and greedy the paupers under their care are, and how thankful the poor should be of the efforts made for them by government agencies. Mr. Bumble tells Mrs. Corney about one man who said he would die in the streets without food, so he was sent out a pound of potatoes and half a pint of oatmeal, only to object that it was of no use to him. The beadle comments:

“he went away; and he diddie in the streets. There’s a obstinate pauper for you! … out-of-door relief, properly managed … is the porochial safeguard. The great principle of out-of-door relief is, to give the paupers exactly what they don’t want; and then they get tired of coming.”

But he warns that these are “official secrets, ma’am; not to be spoken of; except … among the porochial officers, such as ourselves.”

"Mr. Bumble and Mrs. Corney" Sol Eytinge Jr. 1867

Mr. Bumble then gives Mrs. Corney two bottle of port wine which have been sent for the infirmary, and picks up his hat to leave. However when Mrs. Corney offers him a cup of of tea, he accepts with alacrity, and what follows is a very tender flirting scene, which shows that (as the narrator says in the title) “even a beadle may be susceptible on some points.”

There is significant talk of sweets, and cats, and then Mr. Bumble grasps the nettle, saying:

“any cat, or kitten, that could live with you, ma’am, and not be fond of its home, must be a ass, ma’am.”

and gradually inches his chair closer and closer to Mrs. Corney’s.

"Mr. Bumble and Mrs. Corney" - Harry Furniss 1910

"Mr. Bumble and Mrs. Corney taking tea" - George Cruikshank 1838

Since she makes no objection, he becomes bolder and kisses her. Mrs. Corney pretends to protest, for form’s sake that she will scream, but at that moment there is a knock on the door, whereupon:

“Mr. Bumble darted, with much agility, to the wine bottles, and began dusting them with great violence: while the matron sharply demanded who was there.”

The door opens, and a “withered old female pauper, hideously ugly” puts her head in to say that "Old Sally" is about to die and has asked for the matron. Indeed, the pauper says, she will not die until she has seen Mrs. Corney, and told her what is on her mind. Mrs. Corney is not pleased:

“the worthy Mrs. Corney muttered a variety of invectives against old women who couldn’t even die without purposely annoying their betters”

but leaves with the pauper, with a very ill grace, telling her off all the time.

Left on his own to wait for her return, Mr. Bumble expresses delight as he takes an inventory of Mrs. Corney’s silver and furnishings.

"Inexplicable conduct of Mr. Bumble when Mrs. Corney left the room" - F.W. Pailthorpe 1885

message 123:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 05, 2023 07:25AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

What a relief this chapter was, from all the tension and violence we had before. I found this chapter hilarious! In fact I think it’s the first amusing chapter we’ve had isn’t it? To be sure there are witty comments sprinkled throughout the whole text of Oliver Twist - (or it wouldn’t be Charles Dickens) - but this is the the first one with continuous laugh-out-loud moments. Mrs. Corney’s courtship by Mr. Bumble is a scream! Charles Dickenss characterisation is spot-on here. Is Mr. Bumble spooning and lusting more after Mrs. Corney, or the silver spoons?

So we are back at the workhouse, where Oliver was born, which comes as quite a surprise. It is as if Charles Dickensis restarting his novel, after all the hoo-hah of publication, and is dragging us back to a place we thought was conceptually as well as geographically far away. Mr. Bumble, who might never have played a further part in this story, has come back centre stage, probably because there was demand from Charles Dickens’s readers. And we have another new character: Mrs. Corney, the matron of the workhouse.

Ah, but do you remember “Old Sally”? It’s intriguing to think of what she might have to tell Mrs. Corney!

So we are back at the workhouse, where Oliver was born, which comes as quite a surprise. It is as if Charles Dickensis restarting his novel, after all the hoo-hah of publication, and is dragging us back to a place we thought was conceptually as well as geographically far away. Mr. Bumble, who might never have played a further part in this story, has come back centre stage, probably because there was demand from Charles Dickens’s readers. And we have another new character: Mrs. Corney, the matron of the workhouse.

Ah, but do you remember “Old Sally”? It’s intriguing to think of what she might have to tell Mrs. Corney!

message 124:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 05, 2023 08:17AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

This is a short chapter, but as well as being highly entertaining, it is superbly written.

As well as the perfect characterisation, we begin with a dramatic instance of the pathetic fallacy. This provides a stylistic link to the previous two chapters, which used the pathetic fallacy to imbue the writing with the power to invoke sheer terror in his readers. Here, in complete contrast, we have a dissatisfied and grumpy widow, bemoaning her lot. Yet again though, Charles Dickens uses the weather to establish the setting and emotion. Mrs. Corney starts to feel a little better - even to the point of being smug about all her belongings - which is such a great cue for the avaricious Mr. Bumble to enter, with all his wiles.

We might think there are enough elements already in this short scene, but even then Charles Dickens has not finished! What do we get, but a savagely sardonic portrayal of the 1844 Poor Amendment Act. It is so skilfully done, and so much more effective to have Mr. Bumble starkly spouting the aims, so that we can see the consequent cruelty, unfairness and misery, than to have a few paragraphs of diatribe roundly condemning the Act by the author.

The setting is masterful. Straight after we have seen a small boy lying bleeding on the ground through no fault of his own but as a direct consequence of social conditions; shot, and then perhaps deserted by Bill Sikes, we have this fatuous pair, with the well-fed and comfortably off Mrs. Corney claiming to be “a poor desolate creature”. She resents being called to attend one of the inmates she is supposed to care for, because it is not convenient for a pauper to die at that moment, while she is taking tea, casually stealing the patients' port wine, and flirting.

Mr. Bumble is just as bad, with his anecdotes ”proving“ how ungrateful the wretches are, and complacently claiming that the powers that be have the answer, that: “the great principle of out-of-door relief is, to give the paupers exactly what they don’t want; and then they get tired of coming.” This food, which was given to indigent paupers who were not inside the workhouse, was being deliberately phased out. A ”quartern” loaf was a quarter the size of an ordinary loaf - and clearly someone who had no home could not do anything with oatmeal.

I cannot help but this that this pair are well matched. Also that the timing throughout is superb, conjuring up a French farce on stage. Victorians were never sexually explicit, as we have seen, but there is much suggestive language and imagery. This slight chapter is a masterclass in how to write. It is amazing to think that already Charles Dickens was capable of work of this quality.

As well as the perfect characterisation, we begin with a dramatic instance of the pathetic fallacy. This provides a stylistic link to the previous two chapters, which used the pathetic fallacy to imbue the writing with the power to invoke sheer terror in his readers. Here, in complete contrast, we have a dissatisfied and grumpy widow, bemoaning her lot. Yet again though, Charles Dickens uses the weather to establish the setting and emotion. Mrs. Corney starts to feel a little better - even to the point of being smug about all her belongings - which is such a great cue for the avaricious Mr. Bumble to enter, with all his wiles.

We might think there are enough elements already in this short scene, but even then Charles Dickens has not finished! What do we get, but a savagely sardonic portrayal of the 1844 Poor Amendment Act. It is so skilfully done, and so much more effective to have Mr. Bumble starkly spouting the aims, so that we can see the consequent cruelty, unfairness and misery, than to have a few paragraphs of diatribe roundly condemning the Act by the author.

The setting is masterful. Straight after we have seen a small boy lying bleeding on the ground through no fault of his own but as a direct consequence of social conditions; shot, and then perhaps deserted by Bill Sikes, we have this fatuous pair, with the well-fed and comfortably off Mrs. Corney claiming to be “a poor desolate creature”. She resents being called to attend one of the inmates she is supposed to care for, because it is not convenient for a pauper to die at that moment, while she is taking tea, casually stealing the patients' port wine, and flirting.

Mr. Bumble is just as bad, with his anecdotes ”proving“ how ungrateful the wretches are, and complacently claiming that the powers that be have the answer, that: “the great principle of out-of-door relief is, to give the paupers exactly what they don’t want; and then they get tired of coming.” This food, which was given to indigent paupers who were not inside the workhouse, was being deliberately phased out. A ”quartern” loaf was a quarter the size of an ordinary loaf - and clearly someone who had no home could not do anything with oatmeal.

I cannot help but this that this pair are well matched. Also that the timing throughout is superb, conjuring up a French farce on stage. Victorians were never sexually explicit, as we have seen, but there is much suggestive language and imagery. This slight chapter is a masterclass in how to write. It is amazing to think that already Charles Dickens was capable of work of this quality.

message 125:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 05, 2023 08:27AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

And a little more …

Dickens’s Writing and Method Acting

I remember seeing the wonderful Miriam Margolyes act this scene out, in her one woman show about Charles Dickens. A handful of actors who are Charles Dickens aficionados do this, for instance Simon Callow and Gerald Dickens are highly thought of too.

They narrate an edited text but also act it out, much as Charles Dickens himself did. We can still read Charles Dickens's own acting scripts, with lots of crossings out and stage directions. They are emulating the performance by the author; in fact even before Charles Dickens's stories reached print, well before they were staged as plays or as a one man show, they were acted out. In our side read of My Father as I Recall Him we read Mamie Dickens’s account of how she watched her father acting out his own stories in front of a mirror as he wrote them. This was his regular habit and he had just forgotten that she was there recuperating on the sofa, but secretly watching him.

Charles Dickens’s writing is highly visual, and we know both from his own letters and John Forster' biography that his first love was acting. Charles Dickens could be described as a “method writer” in the same sense that we have method actors. Simon Callow explores this aspect of Charles Dickens as an actor, in his excellent book Charles Dickens and the Great Theatre of the World

The determined creeping by Mr. Bumble towards Mrs. Corney, edging his chair inch by inch was hilarious, demonstrated by Miriam Margolyes. There is another scene much later in Oliver Twist, which Charles Dickens's public worldwide repeatedly clamoured for him to act, throughout his life but found it exhausting. We still have his stage notes for this one. His doctor warned him to stop, but he ignored his doctor, and these performances (especially the vivid scene I will tell you about when we get there) are largely what killed him at 58, long before he should have died.

Dickens’s Writing and Method Acting

I remember seeing the wonderful Miriam Margolyes act this scene out, in her one woman show about Charles Dickens. A handful of actors who are Charles Dickens aficionados do this, for instance Simon Callow and Gerald Dickens are highly thought of too.

They narrate an edited text but also act it out, much as Charles Dickens himself did. We can still read Charles Dickens's own acting scripts, with lots of crossings out and stage directions. They are emulating the performance by the author; in fact even before Charles Dickens's stories reached print, well before they were staged as plays or as a one man show, they were acted out. In our side read of My Father as I Recall Him we read Mamie Dickens’s account of how she watched her father acting out his own stories in front of a mirror as he wrote them. This was his regular habit and he had just forgotten that she was there recuperating on the sofa, but secretly watching him.

Charles Dickens’s writing is highly visual, and we know both from his own letters and John Forster' biography that his first love was acting. Charles Dickens could be described as a “method writer” in the same sense that we have method actors. Simon Callow explores this aspect of Charles Dickens as an actor, in his excellent book Charles Dickens and the Great Theatre of the World

The determined creeping by Mr. Bumble towards Mrs. Corney, edging his chair inch by inch was hilarious, demonstrated by Miriam Margolyes. There is another scene much later in Oliver Twist, which Charles Dickens's public worldwide repeatedly clamoured for him to act, throughout his life but found it exhausting. We still have his stage notes for this one. His doctor warned him to stop, but he ignored his doctor, and these performances (especially the vivid scene I will tell you about when we get there) are largely what killed him at 58, long before he should have died.

message 126:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 05, 2023 01:18PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

And even more …

In the early 1800s when a woman married, everything she owned or earned became the property of her husband. This would not begin to change until the first of series of "Married Women’s Property Act" was passed in 1870. So Mr. Bumble’s motives are perfectly clear; he is looking to gain a nice little extra nest-egg.

Perhaps someone would like to look into and write a little more about this, if you like.

Over to you now for your thoughts about style, content, and whatever impressed you most.

In the early 1800s when a woman married, everything she owned or earned became the property of her husband. This would not begin to change until the first of series of "Married Women’s Property Act" was passed in 1870. So Mr. Bumble’s motives are perfectly clear; he is looking to gain a nice little extra nest-egg.

Perhaps someone would like to look into and write a little more about this, if you like.

Over to you now for your thoughts about style, content, and whatever impressed you most.

message 127:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 05, 2023 01:21PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Um, are you all still worrying about Oliver? Or didn't you enjoy this chapter as much as I did? Lots of people have usually pitched in by now! 😃

That’s weird because I’ve checked several times early and a few hours later but didn’t see the posts until now.

That’s weird because I’ve checked several times early and a few hours later but didn’t see the posts until now. I did love this chapter for its comic relief.

I especially loved the description of the bitter piercing cold in the opening paragraph. Dickens was very clever to explain how this was the weather for families with nice warm homes but for those with none, this weather was a death sentence. I was surprised that such a somber opening lead into such a farcical event such as Mr. Bumble courting a lady! I almost thought he had turned her off with his comment about the cats. Oh my! I say if she can put up with him, then she’s no better a woman. And her ugly attitude did come out at the end when she was bothered by a death. Very cleverly and expertly written to be able to combine the comedy with the tragedy of what was happening to the poor.

Well, yes, I am still worried about Oliver - though there are so many pages left in the book that I'm sure he's not dead.

Well, yes, I am still worried about Oliver - though there are so many pages left in the book that I'm sure he's not dead.I did enjoy this chapter. The flirtation oozes off the page, and Jean you are spot on about the writing - it is quite funny. You've done a marvelous job summarizing it all.

I really enjoyed all the various illustrations for this chapter. I particularly like Pailthorpe's illustration of Mr. Bumble dancing round the table. I notice in Cruikshank's illustration, it appears Mrs. Coney has a portrait of herself on the wall. Is that an indication of vanity? Or was that a normal thing to hang on one's wall? I expected her to have a picture of her dear husband hanging on the wall, perhaps this indicates she doesn't miss him as much as she says?

One more thing, the "singing tea kettle" made me think of The Cricket on the Hearth for a moment.

I really enjoyed reading this chapter. I imagined Mr Bumble surreptitiously inventorying cutlery, spoons, etc. He is himself not the sharpest knife in the drawer.

I really enjoyed reading this chapter. I imagined Mr Bumble surreptitiously inventorying cutlery, spoons, etc. He is himself not the sharpest knife in the drawer.More seriously, it is one of those chapters that Dickens enjoys writing, just to make the cliffhanger more efficient and test our patience and keep us alert. And also to release tension. (I have just read chapter 33 in Little Dorrit. An ironic and funny conversation between Mrs Merdle, her parrot, and Mrs Gowan comes up right after we are left waiting for some crucial information on Mr Dorrit in chapter 32.)

Bionic Jean wrote: "And even more …

Bionic Jean wrote: "And even more …In the early 1800s when a woman married, everything she owned or earned became the property of her husband. This would not begin to change until the first of series of "Married Wom..."

The common law legal doctrine of a woman's property and earnings falling under the ownership of her husband was called coverture. More broadly, under coverture, a woman upon marriage is no longer a separate legal entity.

Prior to the before mentioned act of 1870, there were legal ways for a woman to retain control over her property, for example, through the use of trusts. One perhaps heard about marriage settlements. One aspect of this legal negotiation was how much control the perspective bride would retain over the property and income she would bring into the marriage.

The act of 1870 removed coverture for income setting the de jure standard a married woman controlled her income. Another act in 1882 removed coverture for property. The main beneficiaries were middle class women. The previous system involved legal expenses that middle class households might not have been able to afford.

There is the separate question of how these legal changes altered the dynamics of the Victorian household. The Victorian ideal, especially for middle class homes, was the house was the dominion of the wife. As part of this sphere, she would have responsibility over budgetary matters. But obviously there were husbands who were despots necessitating the formal legal protections for married women.

Beth wrote: "Jean mentions John Bayley's essay "Things as They Really Are" in messages 36 and 40. I read the essay, and would recommend it if you don't mind spoilers. (Obviously, I don't.) Like many academic pi..."

Beth wrote: "Jean mentions John Bayley's essay "Things as They Really Are" in messages 36 and 40. I read the essay, and would recommend it if you don't mind spoilers. (Obviously, I don't.) Like many academic pi..."Can you help me find this essay? I have spent too much time searching for it! Anyone?

Bionic Jean wrote: "And a little more …

Bionic Jean wrote: "And a little more …Dickens’s Writing and Method Acting

I remember seeing the wonderful Miriam Margolyes act this scene out, in her one woman show about [author:Charles Dickens|239..."

Sir Patrick Stewart performed a one man "A Christmas Carol" to great acclaim.

Beth wrote: "Bionic Jean wrote: "Sue and Susan - Yes, I agree. 🙄 In fact the point about Oliver's reading bothers me every time I read Oliver Twist!"

Beth wrote: "Bionic Jean wrote: "Sue and Susan - Yes, I agree. 🙄 In fact the point about Oliver's reading bothers me every time I read Oliver Twist!"It could be an oversight by a younger writer. I remember in Dickens' later novel Bleak House it's explicitly mentioned that Jo, the street sweeper, who would be of a similar socioeconomic class as Oliver, is illiterate.

Interesting point about the literacy. I believe Charles Dickens himself was fond of this Oliver he has created, and in doing so he decided to "give" him literacy, which automatically, in the opinion of society, raises a person to a higher social class.

Oliver is very different from the other street kids; he simply doesn't fit; he is an outsider from the very beginning. In addition to not talking in the dialect of the other child-thieves, even his face is different - his physiognomy is attractive, making him more useful as a "decoy" for the thieves.

His ability to read is almost absorbed from the air by his "goodness" as an icon. By this point in the story, Dickens would have had to go back and add some kind of education to account for the boy's literacy, as it is an essential element in creating an illusion of a superior social class for Oliver.

It seems as though I just can't find any faults with Dickens; to me, where we have an unresolved question, Dickens the author could have easily addressed our concerns on Oliver's literacy!

message 135:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 06, 2023 04:22AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Bridget wrote: "I notice in Cruikshank's illustration, it appears Mrs. Coney has a portrait of herself on the wall. Is that an indication of vanity? Or was that a normal thing to hang on one's wall? I expected her to have a picture of her dear husband hanging on the wall, perhaps this indicates she doesn't miss him as much as she says?"

You are absolutely spot on with this Bridget and also with the singing kettle 😀 Here is part of Michael Steig's commentary on that illustration:

(view spoiler)

There are no spoilers here by the way. I've merely put it under a tag to save space. I think it's an interesting piece of criticism and I'm not sure I'd have appreciated the almost proto-Freudian references!

You are absolutely spot on with this Bridget and also with the singing kettle 😀 Here is part of Michael Steig's commentary on that illustration:

(view spoiler)

There are no spoilers here by the way. I've merely put it under a tag to save space. I think it's an interesting piece of criticism and I'm not sure I'd have appreciated the almost proto-Freudian references!

Lee G wrote: "Can you help me find this essay? I have spent too much time searching for it! Anyone?"

Lee G wrote: "Can you help me find this essay? I have spent too much time searching for it! Anyone?"I didn't find it online, either. It's one of the essays included in the supplementary material of the 1993 Norton Critical Edition of Oliver Twist, and that's where I read it.

message 137:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 05, 2023 03:05PM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Lee - My copy of the essay is in the Norton Critical edition. It includes several excellent essays by various Dickens scholars, plus letters and early reviews. Oliver Twist edited by Fred Kaplan

Edit - sorry Beth - crossposted.

Edit - sorry Beth - crossposted.

Thanks too, Michael, Lori and Claudia. I have no idea why my comments apparently did not show up for over 8 hours! 🙄

I actually thought Mrs. Corney was Mrs. Mann from the baby farm (is that right?) But her complaints were rather frivolous and ironic - to complain about those poor workhouse inmates who aren’t even allowed to have or speak an opinion about their conditions most likely.

I actually thought Mrs. Corney was Mrs. Mann from the baby farm (is that right?) But her complaints were rather frivolous and ironic - to complain about those poor workhouse inmates who aren’t even allowed to have or speak an opinion about their conditions most likely. And I am curious what the woman who is dying wants with Mrs. Corney?

message 140:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 06, 2023 03:24AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Lori wrote: "I actually thought Mrs. Corney was Mrs. Mann from the baby farm (is that right?) ..."

No, they are two different people. Mrs. Corney is the matron living in her select and snug little rooms at the workhouse, but Mrs. Mann lives in a different place, at a baby farm 3 miles away from the workhouse, with all the babies. It's in chapter 2 - remember the picket fence where Mrs. Mann met Mr. Bumble, and the coal cellar where Oliver was kept (hidden away, another running theme).

Some dramatisations conflate the two, which is perhaps what you are remembering, Lori?

No, they are two different people. Mrs. Corney is the matron living in her select and snug little rooms at the workhouse, but Mrs. Mann lives in a different place, at a baby farm 3 miles away from the workhouse, with all the babies. It's in chapter 2 - remember the picket fence where Mrs. Mann met Mr. Bumble, and the coal cellar where Oliver was kept (hidden away, another running theme).

Some dramatisations conflate the two, which is perhaps what you are remembering, Lori?

Not sure if I’m remembering correctly, but wasn’t Sally present at Oliver’s birth? I’m wondering if she may have learned, heard or seen something of importance that she needs to relieve her mind of before she dies. That would be interesting information to land in Mr. Bumble’s lap.

Not sure if I’m remembering correctly, but wasn’t Sally present at Oliver’s birth? I’m wondering if she may have learned, heard or seen something of importance that she needs to relieve her mind of before she dies. That would be interesting information to land in Mr. Bumble’s lap.

Claudia wrote: "I very much enjoyed reading all your posts.

Claudia wrote: "I very much enjoyed reading all your posts.Talking about sacrifice, I thought, in a way, of Genesis 22. It describes what Christians churches frequently call Abraham's Sacrifice, i.e. Abraham is ..."

Fascinating exegesis! Thank you, Claudia! I see a problem which perhaps you can solve. In the Genesis narrative, we have God / Yahweh deliberately asking Abraham to sacrifice Isaac. In Oliver Twist, WHO is requesting the sacrifice of Oliver?

No one here has the role of Yahweh. And also, I don't believe that Sikes fills the role of Abraham. But the theme of sacrifice seems apparent and acknowledging that Dickens was well versed in the Bible is an excellent point.

Lee G wrote: "... John Bayley's essay "Things as They Really Are" ...Can you help me find this essay?"

Lee G wrote: "... John Bayley's essay "Things as They Really Are" ...Can you help me find this essay?"You can also find the essay in John Gross's Dickens And The Twentieth Century. You can find the book on archive.org.

https://archive.org/details/dickenstw...

You can read it online for free, but you must set up a free account first. [BTW, if you don't use archive.org already, it's a great source for public domain books, in many formats.]

Although Mr Bumble's behavior in moving his chair guadually closer and with all of the veiled flirtations were hilarious, I was still a bit shocked by the kiss. I already knew that Mr Bumble was not very concerned about his charges' welfare, but it seems he is also not as worried about the respectability of his position as I thought!

Although Mr Bumble's behavior in moving his chair guadually closer and with all of the veiled flirtations were hilarious, I was still a bit shocked by the kiss. I already knew that Mr Bumble was not very concerned about his charges' welfare, but it seems he is also not as worried about the respectability of his position as I thought!Mrs Corney's callousness to the deaths of her charges is expressed with wonderful sardonic wit but is also a bit shocking. It seems the two of them are a good match for each other - what a pair!

I'm a little confused by the useless items that are offered in this chapter to those begging outdoors. I guess the potatoes and porridge are useless because they require cooking and the people who beg outdoors have no means of cooking them? But why would cheese be useless to the sick families? I'm a little dumfounded by that part.

Bionic Jean wrote: "“the great principle of out-of-door relief is, to give the paupers exactly what they don’t want; and then they get tired of coming.” This food, which was given to indigent paupers who were not inside the workhouse, was being deliberately phased out."

Bionic Jean wrote: "“the great principle of out-of-door relief is, to give the paupers exactly what they don’t want; and then they get tired of coming.” This food, which was given to indigent paupers who were not inside the workhouse, was being deliberately phased out."I'm sure that many readers back then felt much like we do now about bureaucracy: that it forms an obfuscatory layer between what we are being forced to request from it, and our actually obtaining it, to the point that we feel like we're being "gently encouraged" to give up asking at all. Of course here, that idea is reality, and personified in these melodramatically evil parish officials. (And, as Jean alludes to here, the next step is "so few people are asking, it mustn't be needed.")

Like Lori, I appreciated this chapter as a change of pace. I'm too tender-hearted to find it particularly funny, but I did enjoy how Dickens staged this revolting couple's dance around the tea table.

Anyone else reading the 1838 edition? Oliver Twist. It is the Penguin edition, and I wish I had chosen another! Book the First ends with Chapter 22, "The Burglary".

Anyone else reading the 1838 edition? Oliver Twist. It is the Penguin edition, and I wish I had chosen another! Book the First ends with Chapter 22, "The Burglary".What you have described as Chapter 23 was originally Book the Second, Chapter the First in the 1838 edition. So originally he ended the first edition with Oliver being shot "and a cold deadly feeling [that] crept over the boy's heart, and he saw or heard no more.

In his later and preferred revision, where does he end Book the First?

Lee G wrote: "Claudia wrote: "I very much enjoyed reading all your posts.

Lee G wrote: "Claudia wrote: "I very much enjoyed reading all your posts.Talking about sacrifice, I thought, in a way, of Genesis 22. It describes what Christians churches frequently call Abraham's Sacrifice, ..."

Thank you Lee! I am aware that my comparisons are incomplete: who has the role of Yahweh indeed? Sikes is but a mock father, not a patriarch, a role that he conveniently attributes himself to when the cart driver assumes Oliver to be Sikes' son. Then, no angel of God appears as a deus ex machina for rescuing Oliver. Perhaps all these questions will be answered later.

JP - Thank you for the additional information about the essay. I had gathered (from Claudia I think) that it is in various compilations of critical works.

Great posts Beth and Claudia!

Great posts Beth and Claudia!

message 149:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 06, 2023 04:09AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Greg - Excellent observations! Yes, deliberately giving foodstuff such as oatmeal that needed cooking as outdoor relief is clearly nonsensical, but as you say, "why would cheese be useless to the sick families?" This is not as obvious, but I think it's just an opportunity for the beadle to joke about "toasting cheese". The point is that it's that the relief is not in proportion. They are given a tiny bit of bread (a quarter of a loaf), plus a pound of cheese, but no way of heating their room:

"What does he do, ma’am, but ask for a few coals; if it’s only a pocket handkerchief full, he says! Coals! What would he do with coals? Toast his cheese with ’em and then come back for more."

So we see the callousness and almost irrelevance to a family of what is provided. A tiny amount of food, and no way to keep warm. What we have to remember is that these people had nothing. Interestingly, ordinary people often had no way to cook their food either, but had to take it out to be cooked in shops at perhaps a penny a time. (This is in our side read of The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London by The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London, and comes up in various of Charles Dickens's novels.)

"What does he do, ma’am, but ask for a few coals; if it’s only a pocket handkerchief full, he says! Coals! What would he do with coals? Toast his cheese with ’em and then come back for more."

So we see the callousness and almost irrelevance to a family of what is provided. A tiny amount of food, and no way to keep warm. What we have to remember is that these people had nothing. Interestingly, ordinary people often had no way to cook their food either, but had to take it out to be cooked in shops at perhaps a penny a time. (This is in our side read of The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London by The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London, and comes up in various of Charles Dickens's novels.)

message 150:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Jun 06, 2023 04:19AM)

(new)

-

rated it 4 stars

Lee - Hopefully the summaries I write help you pinpoint exactly where we are. I always end them exactly where the 1846 edition does, and this is the same the Gutenberg text https://www.gutenberg.org/files/730/7...

This is chapter 23, which from what you say is the First chapter in the Second Book. (But I think it is also a continuation of chapter 22 in some editions!)

I now have 5 copies of the text, but none of them puts them into Books - sorry! I knew there was one, but don't find it helpful. So I refer you to the earlier link where a scholar details all the different chapter endings in different editions. This is what I was referring to when I said to Franky that we could identify several other cliffhangers which aren't at the end of installments.

Since as far as I know only one edition puts them into books, asking where Charles Dickens ends Book the First in other editions is not a viable question, (literally, I mean, as he does not use that way of titling) - or rather you know the answer already, as you have quoted the end of chapter 22. Therefore the division between the books in your edition comes at the perfect time, when we return to Oliver's place of birth, the workhouse 😊 In terms of the story, it's a break and the start of a different section, for sure.

I hope this helps a bit; it's best not to get too hung up on it though, as this is the one novel which Charles Dickens made a lot of minor changes to. There are differences in Dombey and Son (as we found and explored) but in the detail, and not tweaking the overall structure as in Oliver Twist.

The next chapter will be up soon.

This is chapter 23, which from what you say is the First chapter in the Second Book. (But I think it is also a continuation of chapter 22 in some editions!)

I now have 5 copies of the text, but none of them puts them into Books - sorry! I knew there was one, but don't find it helpful. So I refer you to the earlier link where a scholar details all the different chapter endings in different editions. This is what I was referring to when I said to Franky that we could identify several other cliffhangers which aren't at the end of installments.

Since as far as I know only one edition puts them into books, asking where Charles Dickens ends Book the First in other editions is not a viable question, (literally, I mean, as he does not use that way of titling) - or rather you know the answer already, as you have quoted the end of chapter 22. Therefore the division between the books in your edition comes at the perfect time, when we return to Oliver's place of birth, the workhouse 😊 In terms of the story, it's a break and the start of a different section, for sure.

I hope this helps a bit; it's best not to get too hung up on it though, as this is the one novel which Charles Dickens made a lot of minor changes to. There are differences in Dombey and Son (as we found and explored) but in the detail, and not tweaking the overall structure as in Oliver Twist.

The next chapter will be up soon.

Books mentioned in this topic

Little Dorrit (other topics)Dombey and Son (other topics)

Oliver Twist (other topics)

The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London (other topics)

The Pickwick Papers (other topics)

More...

Authors mentioned in this topic

Vybarr Cregan-Reid (other topics)Charles Dickens (other topics)

Charles Dickens (other topics)

Harry Furniss (other topics)

Charles Dickens (other topics)

More...

I wonder with the original serial form a reader could have reasonable thought, well this sad tale is going to end soon. Those of us with the novel form know somehow the story has to continue as there are plenty of pages to go.

I am fascinated where Dickens is going to take this. There is the risk of Oliver dying from the loss of blood, but also risk of infection and gangrene. The soft lead bullets of the era were notorious for inflicting horrendous wounds often shattering bones. Based on everything we know about Fagin, Sikes and company they would have no qualms just eliminating the problem. And Oliver showed he was willing to betray them.