The History Book Club discussion

This topic is about

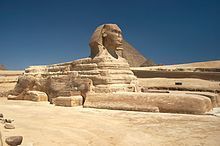

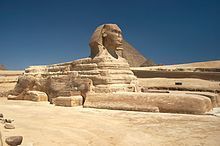

Cleopatra

ANCIENT HISTORY

>

ARCHIVE - CLEOPATRA - GLOSSARY - Spoiler Thread

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Cleopatra

Cleopatra

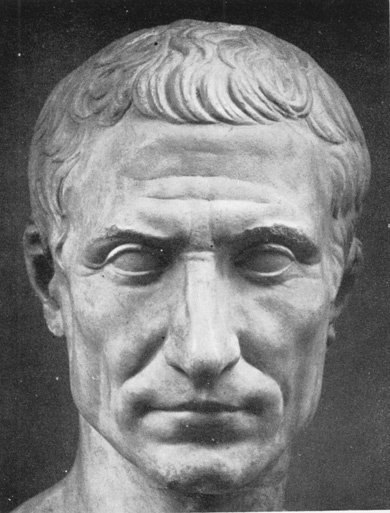

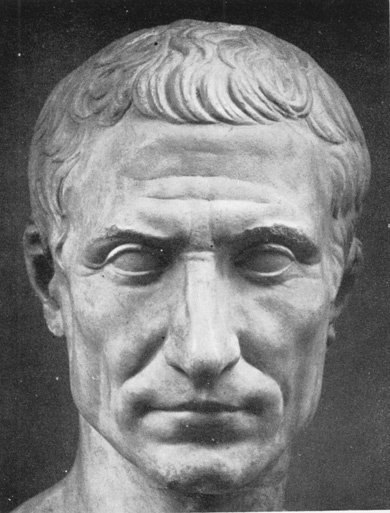

Cleopatra VII was the last ruler of the Ptolemaic dynasty, ruling Egypt from 51 BC - 30 BC. She is celebrated for her beauty and her love affairs with the Roman warlords Julius Caesar and Mark Antony.

Cleopatra was born in 69 BC - 68 BC. When her father Ptolemy XII died in 51 BC, Cleopatra became co-regent with her 10-year-old brother Ptolemy XIII. They were married, in keeping with Egyptian tradition. Whether she was as beautiful as was claimed, she was a highly intelligent woman and an astute politician, who brought prosperity and peace to a country that was bankrupt and split by civil war.

In 48 BC, Egypt became embroiled in the conflict in Rome between Julius Caesar and Pompey. Pompey fled to the Egyptian capital Alexandria, where he was murdered on the orders of Ptolemy. Caesar followed and he and Cleopatra became lovers. Cleopatra, who had been exiled by her brother, was reinstalled as queen with Roman military support. Ptolemy was killed in the fighting and another brother was created Ptolemy XIII. In 47 BC, Cleopatra bore Caesar a child - Caesarion - though Caesar never publicly acknowledged him as his son. Cleopatra followed Caesar back to Rome, but after his assassination in 44 BC, she returned to Egypt. Ptolemy XIV died mysteriously at around this time, and Cleopatra made her son Caesarion co-regent.

In 41 BC, Mark Antony, at that time in dispute with Caesar's adopted son Octavian over the succession to the Roman leadership, began both a political and romantic alliance with Cleopatra. They subsequently had three children - two sons and a daughter. In 31 BC, Mark Antony and Cleopatra combined armies to take on Octavian's forces in a great sea battle at Actium, on the west coast of Greece. Octavian was victorious and Cleopatra and Mark Antony fled to Egypt. Octavian pursued them and captured Alexandria in 30 BC. With his soldiers deserting him, Mark Antony took his own life and Cleopatra chose the same course, committing suicide on 12 August 30 BC. Egypt became a province of the Roman Empire.

Source: BBC

More:

Smithsonian Magazine's article

Britannica's entry

Live Science's biography

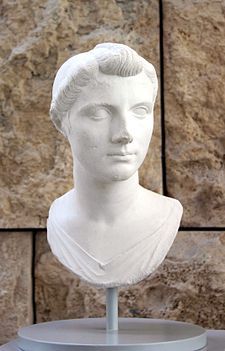

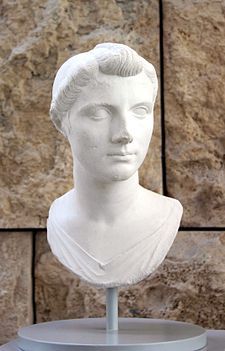

Was Cleopatra beautiful? The archaeological evidence

Cleopatra's death

by Duane W. Roller (no photo)

by Duane W. Roller (no photo) by Joyce A. Tyldesley (no photo)

by Joyce A. Tyldesley (no photo) by Joann Fletcher (no photo)

by Joann Fletcher (no photo) by

by

Michael Grant

Michael Grant by

by

Adrian Goldsworthy

Adrian Goldsworthy

I also came across this site that shows some pictures of what Cleopatra may have looked like based on the coins. Not sure how accurate but I can see how they got there:

I also came across this site that shows some pictures of what Cleopatra may have looked like based on the coins. Not sure how accurate but I can see how they got there:

(Source: Reno Coin Club)

Ptolemaic dynasty

Ptolemy I Soter

The Ptolemaic dynasty (Ancient Greek: Πτολεμαῖοι, Ptolemaioi), sometimes also known as the Lagids or Lagidae (Ancient Greek: Λαγίδαι, Lagidai, after Lagus, Ptolemy I's father), was a Macedonian Greek royal family which ruled the Ptolemaic Empire in Egypt during the Hellenistic period. Their rule lasted for 275 years, from 305 BC to 30 BC. They were the last dynasty of ancient Egypt.

Ptolemy, one of the six somatophylakes (bodyguards) who served as Alexander the Great's generals and deputies, was appointed satrap of Egypt after Alexander's death in 323 BC. In 305 BC, he declared himself King Ptolemy I, later known as "Soter" (saviour). The Egyptians soon accepted the Ptolemies as the successors to the pharaohs of independent Egypt. Ptolemy's family ruled Egypt until the Roman conquest of 30 BC.

All the male rulers of the dynasty took the name Ptolemy. Ptolemaic queens, some of whom were the sisters of their husbands, were usually called Cleopatra, Arsinoe or Berenice. The most famous member of the line was the last queen, Cleopatra VII, known for her role in the Roman political battles between Julius Caesar and Pompey, and later between Octavian and Mark Antony. Her apparent suicide at the conquest by Rome marked the end of Ptolemaic rule in Egypt.

(Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ptolemai... - see the article for a family tree)

More:

http://www.touregypt.net/alexhis1.htm

http://www.tyndalehouse.com/egypt/pto...

http://www.livius.org/dynasty/ptolemies/

http://ancienthistory.about.com/od/eg...

http://www.kingtutone.com/ancient-egy...

(no image) Rome And The Ptolemies Of Egypt: The Development Of Their Political Relations, 273 80 B. C by Anssi Lampela (no photo)

by J.G. Manning (no photo)

by J.G. Manning (no photo)

by John Pentland Mahaffy (no photo)

by John Pentland Mahaffy (no photo)

by Edwyn R. Bevan (no photo)

by Edwyn R. Bevan (no photo)

by Jane Rowlandson (no photo)

by Jane Rowlandson (no photo)

Ptolemy I Soter

The Ptolemaic dynasty (Ancient Greek: Πτολεμαῖοι, Ptolemaioi), sometimes also known as the Lagids or Lagidae (Ancient Greek: Λαγίδαι, Lagidai, after Lagus, Ptolemy I's father), was a Macedonian Greek royal family which ruled the Ptolemaic Empire in Egypt during the Hellenistic period. Their rule lasted for 275 years, from 305 BC to 30 BC. They were the last dynasty of ancient Egypt.

Ptolemy, one of the six somatophylakes (bodyguards) who served as Alexander the Great's generals and deputies, was appointed satrap of Egypt after Alexander's death in 323 BC. In 305 BC, he declared himself King Ptolemy I, later known as "Soter" (saviour). The Egyptians soon accepted the Ptolemies as the successors to the pharaohs of independent Egypt. Ptolemy's family ruled Egypt until the Roman conquest of 30 BC.

All the male rulers of the dynasty took the name Ptolemy. Ptolemaic queens, some of whom were the sisters of their husbands, were usually called Cleopatra, Arsinoe or Berenice. The most famous member of the line was the last queen, Cleopatra VII, known for her role in the Roman political battles between Julius Caesar and Pompey, and later between Octavian and Mark Antony. Her apparent suicide at the conquest by Rome marked the end of Ptolemaic rule in Egypt.

(Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ptolemai... - see the article for a family tree)

More:

http://www.touregypt.net/alexhis1.htm

http://www.tyndalehouse.com/egypt/pto...

http://www.livius.org/dynasty/ptolemies/

http://ancienthistory.about.com/od/eg...

http://www.kingtutone.com/ancient-egy...

(no image) Rome And The Ptolemies Of Egypt: The Development Of Their Political Relations, 273 80 B. C by Anssi Lampela (no photo)

by J.G. Manning (no photo)

by J.G. Manning (no photo) by John Pentland Mahaffy (no photo)

by John Pentland Mahaffy (no photo) by Edwyn R. Bevan (no photo)

by Edwyn R. Bevan (no photo) by Jane Rowlandson (no photo)

by Jane Rowlandson (no photo)

National Geographic has an online article about Cleopatra with an interesting interactive map of Alexandria.

Links to their other articles about ancient Egypt can be found here in their Egypt Hub.

Links to their other articles about ancient Egypt can be found here in their Egypt Hub.

Library of Alexandria

The Royal Library of Alexandria, or Ancient Library of Alexandria, in Alexandria, Egypt, was one of the largest and most significant libraries of the ancient world. It flourished under the patronage of the Ptolemaic dynasty and functioned as a major center of scholarship from its construction in the 3rd century BC until the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 BC. The library was conceived and opened either during the reign of Ptolemy I Soter (323–283 BC), or during the reign of his son Ptolemy II (283–246 BC).

During Plutarch's (AD 46–120) visit to Alexandria in 48 BC, he wrote that Julius Caesar had accidentally burned the library down when he set fire to his own ships to frustrate Achillas', and attempt to limit his ability to communicate by sea. After its destruction, scholars used a "daughter library" in a temple known as the Serapeum, located in another part of the city. However, it has been noted in Florus and Lucan's writings that the flames Caesar set only burned the fleet and some "houses near the sea," with no mention of the library. Furthermore, years after Caesar's campaign in Alexandria, the Greek geographer Strabo worked in the two buildings which composed the Alexandrian library, both of which he described as "perfectly intact."

Ancient and modern sources identify four possible occasions for the partial or complete destruction of the Library of Alexandria: Julius Caesar's fire in the Alexandrian War, in 48 BC; the attack of Aurelian in AD 270 – 275; the decree of Coptic Pope Theophilus in AD 391; and the Muslim conquest in AD 642 or thereafter.

(Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Library_...)

More:

http://www.crystalinks.com/libraryofa...

http://www.ancient-origins.net/ancien...

http://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/e...

by Kelly Trumble (no photo)

by Kelly Trumble (no photo)

by Roy MacLeod (no photo)

by Roy MacLeod (no photo)

by Charles River Editors (no photo)

by Charles River Editors (no photo)

by Mostafa El-Abbadi (no photo)

by Mostafa El-Abbadi (no photo)

The Royal Library of Alexandria, or Ancient Library of Alexandria, in Alexandria, Egypt, was one of the largest and most significant libraries of the ancient world. It flourished under the patronage of the Ptolemaic dynasty and functioned as a major center of scholarship from its construction in the 3rd century BC until the Roman conquest of Egypt in 30 BC. The library was conceived and opened either during the reign of Ptolemy I Soter (323–283 BC), or during the reign of his son Ptolemy II (283–246 BC).

During Plutarch's (AD 46–120) visit to Alexandria in 48 BC, he wrote that Julius Caesar had accidentally burned the library down when he set fire to his own ships to frustrate Achillas', and attempt to limit his ability to communicate by sea. After its destruction, scholars used a "daughter library" in a temple known as the Serapeum, located in another part of the city. However, it has been noted in Florus and Lucan's writings that the flames Caesar set only burned the fleet and some "houses near the sea," with no mention of the library. Furthermore, years after Caesar's campaign in Alexandria, the Greek geographer Strabo worked in the two buildings which composed the Alexandrian library, both of which he described as "perfectly intact."

Ancient and modern sources identify four possible occasions for the partial or complete destruction of the Library of Alexandria: Julius Caesar's fire in the Alexandrian War, in 48 BC; the attack of Aurelian in AD 270 – 275; the decree of Coptic Pope Theophilus in AD 391; and the Muslim conquest in AD 642 or thereafter.

(Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Library_...)

More:

http://www.crystalinks.com/libraryofa...

http://www.ancient-origins.net/ancien...

http://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/e...

by Kelly Trumble (no photo)

by Kelly Trumble (no photo) by Roy MacLeod (no photo)

by Roy MacLeod (no photo) by Charles River Editors (no photo)

by Charles River Editors (no photo) by Mostafa El-Abbadi (no photo)

by Mostafa El-Abbadi (no photo)

Looking at the pictures of what Cleopatra may have looked like, I have to admit that I don't find her that beautiful. But, that leaves me thinking that her beauty may have come as much from her personality as from her physical looks. I think of people in my lifetime who have been considered beautiful, whose features themselves are nothing remarkable - Barbara Streisand comes to mind. She is not beautiful in the classical sense, but when combined with her personality, many people considered her beautiful.

Looking at the pictures of what Cleopatra may have looked like, I have to admit that I don't find her that beautiful. But, that leaves me thinking that her beauty may have come as much from her personality as from her physical looks. I think of people in my lifetime who have been considered beautiful, whose features themselves are nothing remarkable - Barbara Streisand comes to mind. She is not beautiful in the classical sense, but when combined with her personality, many people considered her beautiful.

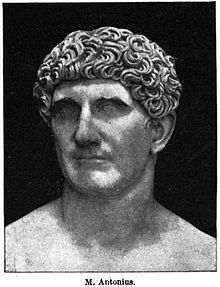

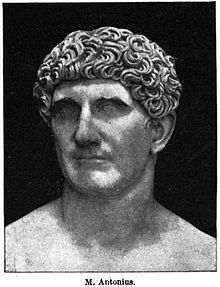

Mark Antony (history through Caesar's death)

Marcus Antonius, commonly known in English as Mark Antony (April 20, 83 BC – August 1, 30 BC), was a Roman politician and general. As a military commander and administrator, he was an important supporter and loyal friend of his mother's cousin Julius Caesar. After Caesar's assassination, Antony formed an official political alliance with Octavian (the future Augustus) and Lepidus, known to historians today as the Second Triumvirate.

The triumvirate broke up in 33 BC. Disagreement between Octavian and Antony erupted into civil war, the final war of the Roman Republic, in 31 BC. Antony was defeated by Octavian at the naval Battle of Actium, and in a brief land battle at Alexandria. He and his lover Cleopatra committed suicide shortly thereafter. His career and defeat are significant in Rome's transformation from Republic to Empire.

Antony lived a dissipate lifestyle as a youth, and gained a reputation for heavy gambling. According to Cicero, he had a homosexual relationship with Gaius Scribonius Curio. There is little reliable information on his political activity as a young man, although it is known that he was an associate of Clodius. He may also have been involved in the Lupercal cult, as he was referred to as a priest of this order later in life.

In 54 BC, Antony became a staff officer in Caesar's armies in Gaul and Germany. He again proved to be a competent military leader in the Gallic Wars, but his personality quirks caused disruption. Antony and Caesar were the best of friends, as well as being fairly close relatives. Antony made himself ever available to assist Caesar in carrying out his military campaigns.

Raised by Caesar's influence to the offices of quaestor, augur, and tribune of the plebeians (50 BC), he supported the cause of his patron with great energy. Caesar's two proconsular commands, during a period of ten years, were expiring in 50 BC, and he wanted to return to Rome for the consular elections. But resistance from the conservative faction of the Roman Senate, led by Pompey, demanded that Caesar resign his proconsulship and the command of his armies before being allowed to seek re-election to the consulship.

This Caesar would not do, as such an act would at least temporarily render him a private citizen and thereby leave him open to prosecution for his acts while proconsul. It would also place him at the mercy of Pompey's armies. To prevent this occurrence Caesar bribed the plebeian tribune Curio to use his veto to prevent a senatorial decree which would deprive Caesar of his armies and provincial command, and then made sure Antony was elected tribune for the next term of office.

Antony exercised his tribunician veto, with the aim of preventing a senatorial decree declaring martial law against the veto, and was violently expelled from the senate with another Caesar adherent, Cassius, who was also a tribune of the plebs. Caesar crossed the river Rubicon upon hearing of these affairs which began the Republican civil war. Antony left Rome and joined Caesar and his armies at Ariminium, where he was presented to Caesar's soldiers still bloody and bruised as an example of the illegalities that his political opponents were perpetrating, and as a casus belli.

Tribunes of the Plebs were meant to be untouchable and their veto inalienable according to the Roman mos maiorum (although there was a grey line as to what extent this existed in the declaration of and during martial law). Antony commanded Italy whilst Caesar destroyed Pompey's legions in Spain, and led the reinforcements to Greece, before commanding the right wing of Caesar's armies at Pharsalus.

On March 14, 44 BC, Antony was alarmed when Cicero told him the gods would strike Caesar. Casca, Marcus Junius Brutus and Cassius decided, in the night before the Assassination of Julius Caesar, that Mark Antony should stay alive. The following day, the Ides of March, he went down to warn the dictator but the Liberatores reached Caesar first and he was assassinated on March 15, 44 BC. In the turmoil that surrounded the event, Antony escaped Rome dressed as a slave; fearing that the dictator's assassination would be the start of a bloodbath among his supporters. When this did not occur, he soon returned to Rome, discussing a truce with the assassins' faction. For a while, Antony, as consul, seemed to pursue peace and an end to the political tension. Following a speech by Cicero in the Senate, an amnesty was agreed for the assassins.

Then came the day of Caesar's funeral. As Caesar's ever-present second in command, co-consul and cousin, Antony wanted to give the eulogy. Brutus and Cassius were reluctant at first, but Brutus decided it would be harmless, Cassius disagreed. In his speech, he made accusations of murder and ensured a permanent breach with the conspirators. Showing a talent for rhetoric and dramatic interpretation, Antony snatched the toga from Caesar's body to show the crowd the stab wounds, pointing at each and naming the authors, publicly shaming them.

During the eulogy he also read Caesar's will, which left most of his property to the people of Rome: whatever Caesar's real intentions had been, Antony presumably meant to demonstrate that contrary to the conspirators' assertions, Caesar had no intention of forming a royal dynasty. Public opinion turned, and that night, the Roman populace attacked the assassins' houses, forcing them to flee for their lives.

(Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_Antony)

More:

http://www.history.com/topics/ancient...

http://www.ancient-rome.biz/marc-anto...

http://www.biography.com/people/mark-...

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/t...

http://www.notablebiographies.com/Lo-...

(no image) Mark Anthony by Alan Roberts (no photo)

by Eleanor Goltz Huzar (no photo)

by Eleanor Goltz Huzar (no photo)

by Patricia Southern (no photo)

by Patricia Southern (no photo)

by Paolo de Ruggiero (no photo)

by Paolo de Ruggiero (no photo)

Marcus Antonius, commonly known in English as Mark Antony (April 20, 83 BC – August 1, 30 BC), was a Roman politician and general. As a military commander and administrator, he was an important supporter and loyal friend of his mother's cousin Julius Caesar. After Caesar's assassination, Antony formed an official political alliance with Octavian (the future Augustus) and Lepidus, known to historians today as the Second Triumvirate.

The triumvirate broke up in 33 BC. Disagreement between Octavian and Antony erupted into civil war, the final war of the Roman Republic, in 31 BC. Antony was defeated by Octavian at the naval Battle of Actium, and in a brief land battle at Alexandria. He and his lover Cleopatra committed suicide shortly thereafter. His career and defeat are significant in Rome's transformation from Republic to Empire.

Antony lived a dissipate lifestyle as a youth, and gained a reputation for heavy gambling. According to Cicero, he had a homosexual relationship with Gaius Scribonius Curio. There is little reliable information on his political activity as a young man, although it is known that he was an associate of Clodius. He may also have been involved in the Lupercal cult, as he was referred to as a priest of this order later in life.

In 54 BC, Antony became a staff officer in Caesar's armies in Gaul and Germany. He again proved to be a competent military leader in the Gallic Wars, but his personality quirks caused disruption. Antony and Caesar were the best of friends, as well as being fairly close relatives. Antony made himself ever available to assist Caesar in carrying out his military campaigns.

Raised by Caesar's influence to the offices of quaestor, augur, and tribune of the plebeians (50 BC), he supported the cause of his patron with great energy. Caesar's two proconsular commands, during a period of ten years, were expiring in 50 BC, and he wanted to return to Rome for the consular elections. But resistance from the conservative faction of the Roman Senate, led by Pompey, demanded that Caesar resign his proconsulship and the command of his armies before being allowed to seek re-election to the consulship.

This Caesar would not do, as such an act would at least temporarily render him a private citizen and thereby leave him open to prosecution for his acts while proconsul. It would also place him at the mercy of Pompey's armies. To prevent this occurrence Caesar bribed the plebeian tribune Curio to use his veto to prevent a senatorial decree which would deprive Caesar of his armies and provincial command, and then made sure Antony was elected tribune for the next term of office.

Antony exercised his tribunician veto, with the aim of preventing a senatorial decree declaring martial law against the veto, and was violently expelled from the senate with another Caesar adherent, Cassius, who was also a tribune of the plebs. Caesar crossed the river Rubicon upon hearing of these affairs which began the Republican civil war. Antony left Rome and joined Caesar and his armies at Ariminium, where he was presented to Caesar's soldiers still bloody and bruised as an example of the illegalities that his political opponents were perpetrating, and as a casus belli.

Tribunes of the Plebs were meant to be untouchable and their veto inalienable according to the Roman mos maiorum (although there was a grey line as to what extent this existed in the declaration of and during martial law). Antony commanded Italy whilst Caesar destroyed Pompey's legions in Spain, and led the reinforcements to Greece, before commanding the right wing of Caesar's armies at Pharsalus.

On March 14, 44 BC, Antony was alarmed when Cicero told him the gods would strike Caesar. Casca, Marcus Junius Brutus and Cassius decided, in the night before the Assassination of Julius Caesar, that Mark Antony should stay alive. The following day, the Ides of March, he went down to warn the dictator but the Liberatores reached Caesar first and he was assassinated on March 15, 44 BC. In the turmoil that surrounded the event, Antony escaped Rome dressed as a slave; fearing that the dictator's assassination would be the start of a bloodbath among his supporters. When this did not occur, he soon returned to Rome, discussing a truce with the assassins' faction. For a while, Antony, as consul, seemed to pursue peace and an end to the political tension. Following a speech by Cicero in the Senate, an amnesty was agreed for the assassins.

Then came the day of Caesar's funeral. As Caesar's ever-present second in command, co-consul and cousin, Antony wanted to give the eulogy. Brutus and Cassius were reluctant at first, but Brutus decided it would be harmless, Cassius disagreed. In his speech, he made accusations of murder and ensured a permanent breach with the conspirators. Showing a talent for rhetoric and dramatic interpretation, Antony snatched the toga from Caesar's body to show the crowd the stab wounds, pointing at each and naming the authors, publicly shaming them.

During the eulogy he also read Caesar's will, which left most of his property to the people of Rome: whatever Caesar's real intentions had been, Antony presumably meant to demonstrate that contrary to the conspirators' assertions, Caesar had no intention of forming a royal dynasty. Public opinion turned, and that night, the Roman populace attacked the assassins' houses, forcing them to flee for their lives.

(Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_Antony)

More:

http://www.history.com/topics/ancient...

http://www.ancient-rome.biz/marc-anto...

http://www.biography.com/people/mark-...

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/t...

http://www.notablebiographies.com/Lo-...

(no image) Mark Anthony by Alan Roberts (no photo)

by Eleanor Goltz Huzar (no photo)

by Eleanor Goltz Huzar (no photo) by Patricia Southern (no photo)

by Patricia Southern (no photo) by Paolo de Ruggiero (no photo)

by Paolo de Ruggiero (no photo)

Mark Antony (part 2)

Leader of the Caesarian Party

Antony, as the sole Consul, soon took the initiative and seized the state treasury. Calpurnia Pisonis, Caesar's widow, presented him with Caesar's personal papers and custody of his extensive property, clearly marking him as Caesar's heir and leader of the Caesarian faction. Caesar's Master of the Horse Marcus Aemilius Lepidus marched over 6,000 troops into Rome on 16 March to restore order and to act as the bodyguards of the Caesarian faction. Lepidus wanted to storm the Capitol, but Antony preferred a peaceful solution as a majority of both the Liberators and Caesar's own supporters preferred a settlement over civil war. On 17 March, at Antony's arrangement, the Senate met to discuss a compromise, which, due to the presence of Caesar's veterans in the city, was quickly reached. Caesar's assassins would be pardoned of their crimes and, in return, all of Caesar's actions would be ratified. In particular, the offices assigned to both Brutus and Cassius by Caesar were likewise ratified. Antony also agreed to accept the appointment of his rival Dolabella as his Consular colleague to replace Caesar. Having neither troops, money, nor popular support, the Liberatores were forced to accept Antony's proposal. This compromise was a great success for Antony, who managed to simultaneously appease Caesar's veterans, reconcile the Senate majority, and appear to the Liberatores as their partner and protector.

On 19 March, Caesar's will was opened and read. In it, Caesar posthumously adopted his great-nephew Gaius Octavius and named him his principal heir. Then only 19 years old and stationed with Caesar's army in Macedonia, the youth became a member of Caesar's Julian clan, changing his name to "Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus" (Octavian) in accordance with the conventions of Roman adoption. Though not the chief beneficiary, Antony did receive some bequests.

Shortly after the compromise was reached, as a sign of good faith, Brutus, against the advice of Cassius and Cicero, agreed Caesar would be given a public funeral and his will would be validated. Caesar's funeral was held on 20 March. Antony, as Caesar's faithful lieutenant and reigning Consul, was chosen to preside over the ceremony and to recite the elegy. During the demagogic speech, he enumerated the deeds of Caesar and, publicly reading his will, detailed the donations Caesar had left to the Roman people. Antony then seized the blood-stained toga from Caesar's body and presented it to the crowd. Worked into a fury by the bloody spectacle, the assembly rioted. Several buildings in the Forum and some houses of the conspirators were burned to the ground. Panicked, many of the conspirators fled Italy. Under the pretext of not being able to guarantee their safety, Antony relieved Brutus and Cassius of their judicial duties in Rome and instead assigned them responsibility for procuring wheat for Rome from Sicily and Asia. Such an assignment, in addition to being unworthy of their rank, would have kept them far from Rome and shifted the balance towards Antony. Refusing such secondary duties, the two traveled to Greece instead. Additionally, Cleopatra left Rome to return to Egypt.

Despite the provisions of Caesar's will, Antony proceeded to act as leader of the Caesarian faction, including appropriating for himself a portion of Caesar's fortune rightfully belonging to Octavian. Antony enacted the Lex Antonia, which formally abolished the Dictatorship, in an attempt to consolidate his power by gaining the support of the Senatorial class. He also enacted a number of laws he claimed to have found in Caesar's papers to ensure his popularity with Caesar's veterans, particularly by providing land grants to them. Lepidus, with Antony's support, was named Pontifex Maximus to succeed Caesar. To solidify the alliance between Antony and Lepidus, Antony's daughter Antonia Prima was engaged to Lepidus's son, also named Lepidus. Surrounding himself with a bodyguard of over six thousand of Caesar's veterans, Antony presented himself as Caesar's true successor, largely ignoring Octavian.

First Conflict with Octavian

Octavian arrived in Rome in May to claim his inheritance. Although Antony had amassed political support, Octavian still had opportunity to rival him as the leading member of the Caesarian faction. The Senatorial Republicans increasingly viewed Antony as a new tyrant. Antony had lost the support of many Romans and supporters of Caesar when he opposed the motion to elevate Caesar to divine status. When Antony refused to relinquish Caesar's vast fortune to him, Octavian borrowed heavily to fulfill the bequests in Caesar's will to the Roman people and to his veterans, as well as to establish his own bodyguard of veterans. This earned him the support of Caesarian sympathizers who hoped to use him as a means of eliminating Antony. The Senate, and Cicero in particular, viewed Antony as the greater danger of the two. By summer 44 BC, Antony was in a difficult position due to his actions regarding his compromise with the Liberatores following Caesar's assassination. He could either denounce the Liberatores as murderers and alienate the Senate or he could maintain his support for the compromise and risk betraying the legacy of Caesar, strengthening Octavian's position. In either case, his situation as ruler of Rome would be weakened. Roman historian Cassius Dio later recorded that while Antony, as reigning Consul, maintained the advantage in the relationship, the general affection of the Roman people was shifting to Octavian due to his status as Caesar's son.

Supporting the Senatorial faction against Antony, Octavian, in September 44 BC, encouraged the leading Senator Marcus Tullius Cicero to attack Antony in a series of speeches portraying him as a threat to the Republican order. Risk of civil war between Antony and Octavian grew. Octavian continued to recruit Caesar's veterans to his side, away from Antony, with two of Antony's legions defecting in November 44 BC. At that time, Octavian, only a private citizen, lacked legal authority to command the Republic's armies, making his command illegal. With popular opinion in Rome turning against him and his Consular term nearing its end, Antony attempted to secure a favorable military assignment to secure an army to protect himself. The Senate, as was custom, assigned Antony and Dolabella the provinces of Macedonia and Syria, respectively, to govern in 43 BC after their Consular terms expired. Antony, however, objected to the assignment, preferring to govern Cisalpine Gaul which had been assigned to Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus, one of Caesar's assassins. When Decimus refused to surrender his province, Antony marched north in December 44 BC with his remaining soldiers to take the province by force, besieging Decimus at Mutina. The Senate, led by a fiery Cicero, denounced Antony's actions and declared him an outlaw.

Ratifying Octavian's extraordinary command on 1 January 43 BC, the Senate dispatched him along with Consuls Hirtius and Pansa to defeat Antony and his five legions. Antony's forces were defeated at the Battle of Mutina in April 43 BC, forcing Antony to retreat to Transalpine Gaul. Both consuls were killed, however, leaving Octavian in sole command of their armies, some eight legions.

(Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_Antony)

Leader of the Caesarian Party

Antony, as the sole Consul, soon took the initiative and seized the state treasury. Calpurnia Pisonis, Caesar's widow, presented him with Caesar's personal papers and custody of his extensive property, clearly marking him as Caesar's heir and leader of the Caesarian faction. Caesar's Master of the Horse Marcus Aemilius Lepidus marched over 6,000 troops into Rome on 16 March to restore order and to act as the bodyguards of the Caesarian faction. Lepidus wanted to storm the Capitol, but Antony preferred a peaceful solution as a majority of both the Liberators and Caesar's own supporters preferred a settlement over civil war. On 17 March, at Antony's arrangement, the Senate met to discuss a compromise, which, due to the presence of Caesar's veterans in the city, was quickly reached. Caesar's assassins would be pardoned of their crimes and, in return, all of Caesar's actions would be ratified. In particular, the offices assigned to both Brutus and Cassius by Caesar were likewise ratified. Antony also agreed to accept the appointment of his rival Dolabella as his Consular colleague to replace Caesar. Having neither troops, money, nor popular support, the Liberatores were forced to accept Antony's proposal. This compromise was a great success for Antony, who managed to simultaneously appease Caesar's veterans, reconcile the Senate majority, and appear to the Liberatores as their partner and protector.

On 19 March, Caesar's will was opened and read. In it, Caesar posthumously adopted his great-nephew Gaius Octavius and named him his principal heir. Then only 19 years old and stationed with Caesar's army in Macedonia, the youth became a member of Caesar's Julian clan, changing his name to "Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus" (Octavian) in accordance with the conventions of Roman adoption. Though not the chief beneficiary, Antony did receive some bequests.

Shortly after the compromise was reached, as a sign of good faith, Brutus, against the advice of Cassius and Cicero, agreed Caesar would be given a public funeral and his will would be validated. Caesar's funeral was held on 20 March. Antony, as Caesar's faithful lieutenant and reigning Consul, was chosen to preside over the ceremony and to recite the elegy. During the demagogic speech, he enumerated the deeds of Caesar and, publicly reading his will, detailed the donations Caesar had left to the Roman people. Antony then seized the blood-stained toga from Caesar's body and presented it to the crowd. Worked into a fury by the bloody spectacle, the assembly rioted. Several buildings in the Forum and some houses of the conspirators were burned to the ground. Panicked, many of the conspirators fled Italy. Under the pretext of not being able to guarantee their safety, Antony relieved Brutus and Cassius of their judicial duties in Rome and instead assigned them responsibility for procuring wheat for Rome from Sicily and Asia. Such an assignment, in addition to being unworthy of their rank, would have kept them far from Rome and shifted the balance towards Antony. Refusing such secondary duties, the two traveled to Greece instead. Additionally, Cleopatra left Rome to return to Egypt.

Despite the provisions of Caesar's will, Antony proceeded to act as leader of the Caesarian faction, including appropriating for himself a portion of Caesar's fortune rightfully belonging to Octavian. Antony enacted the Lex Antonia, which formally abolished the Dictatorship, in an attempt to consolidate his power by gaining the support of the Senatorial class. He also enacted a number of laws he claimed to have found in Caesar's papers to ensure his popularity with Caesar's veterans, particularly by providing land grants to them. Lepidus, with Antony's support, was named Pontifex Maximus to succeed Caesar. To solidify the alliance between Antony and Lepidus, Antony's daughter Antonia Prima was engaged to Lepidus's son, also named Lepidus. Surrounding himself with a bodyguard of over six thousand of Caesar's veterans, Antony presented himself as Caesar's true successor, largely ignoring Octavian.

First Conflict with Octavian

Octavian arrived in Rome in May to claim his inheritance. Although Antony had amassed political support, Octavian still had opportunity to rival him as the leading member of the Caesarian faction. The Senatorial Republicans increasingly viewed Antony as a new tyrant. Antony had lost the support of many Romans and supporters of Caesar when he opposed the motion to elevate Caesar to divine status. When Antony refused to relinquish Caesar's vast fortune to him, Octavian borrowed heavily to fulfill the bequests in Caesar's will to the Roman people and to his veterans, as well as to establish his own bodyguard of veterans. This earned him the support of Caesarian sympathizers who hoped to use him as a means of eliminating Antony. The Senate, and Cicero in particular, viewed Antony as the greater danger of the two. By summer 44 BC, Antony was in a difficult position due to his actions regarding his compromise with the Liberatores following Caesar's assassination. He could either denounce the Liberatores as murderers and alienate the Senate or he could maintain his support for the compromise and risk betraying the legacy of Caesar, strengthening Octavian's position. In either case, his situation as ruler of Rome would be weakened. Roman historian Cassius Dio later recorded that while Antony, as reigning Consul, maintained the advantage in the relationship, the general affection of the Roman people was shifting to Octavian due to his status as Caesar's son.

Supporting the Senatorial faction against Antony, Octavian, in September 44 BC, encouraged the leading Senator Marcus Tullius Cicero to attack Antony in a series of speeches portraying him as a threat to the Republican order. Risk of civil war between Antony and Octavian grew. Octavian continued to recruit Caesar's veterans to his side, away from Antony, with two of Antony's legions defecting in November 44 BC. At that time, Octavian, only a private citizen, lacked legal authority to command the Republic's armies, making his command illegal. With popular opinion in Rome turning against him and his Consular term nearing its end, Antony attempted to secure a favorable military assignment to secure an army to protect himself. The Senate, as was custom, assigned Antony and Dolabella the provinces of Macedonia and Syria, respectively, to govern in 43 BC after their Consular terms expired. Antony, however, objected to the assignment, preferring to govern Cisalpine Gaul which had been assigned to Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus, one of Caesar's assassins. When Decimus refused to surrender his province, Antony marched north in December 44 BC with his remaining soldiers to take the province by force, besieging Decimus at Mutina. The Senate, led by a fiery Cicero, denounced Antony's actions and declared him an outlaw.

Ratifying Octavian's extraordinary command on 1 January 43 BC, the Senate dispatched him along with Consuls Hirtius and Pansa to defeat Antony and his five legions. Antony's forces were defeated at the Battle of Mutina in April 43 BC, forcing Antony to retreat to Transalpine Gaul. Both consuls were killed, however, leaving Octavian in sole command of their armies, some eight legions.

(Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_Antony)

Mark Antony (part 3)

The Second Triumvirate

With Antony defeated, the Senate, hoping to eliminate Octavian and the remainder of the Caesarian party, assigned command of the Republic's legions to Decimus. Sextus Pompey, son of Caesar's old rival Pompey Magnus, was given command of the Republic's fleet from his base in Sicily while Brutus and Cassius were granted the governorships of Macedonia and Syria respectively. These appointments attempted to renew the "Republican" cause. However, the eight legions serving under Octavian, composed largely of Caesar's veterans, refused to follow one of Caesar's murderers, allowing Octavian to retain his command. Meanwhile, Antony recovered his position by joining forces with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, who had been assigned the governorship of Transalpine Gaul and Nearer Spain. Antony sent Lepidus to Rome to broker a conciliation. Though he was an ardent Caesarian, Lepdius had maintained friendly relations with the Senate and with Sextus Pompey. His legions, however, quickly joined Antony, giving him control over seventeen legions, the largest army in the West.

By mid-May, Octavian began secret negotiations to form an alliance with Antony to provide a united Caesarian party against the Liberators. Remaining in Cisalpine Gaul, Octavian dispatched emissaries to Rome in July 43 BC demanding he be appointed Consul to replace Hirtius and Pansa and that the decree declaring Antony a public enemy be rescinded. When the Senate refused, Octavian marched on Rome with his eight legions and assumed control of the city in August 43 BC. Octavian proclaimed himself Consul, rewarded his soldiers, and then set about prosecuting Caesar's murderers. By the lex Pedia, all of the conspirators and Sextus Pompey were convicted in absentia and declared public enemies. Then, at the instigation of Lepidus, Octavian went to Cisalpine Gaul to meet Antony.

In November 43 BC, Octavian, Lepidus, and Antony met near Bononia. After two days of discussions, the group agreed to establish a three man dictatorship to govern the Republic for five years, known as the "Three Man for the Restoration of the Republic" (Latin: "Triumviri Rei publicae Constituendae"), known to modern historians as the Second Triumvirate. In addition, they divided amongst themselves military command of the Republic's armies and provinces: Antony received Gaul, Lepidus Spain, and Octavian (as the junior partner) Africa. The Government of Italy was undivided between the three. The Triumvirate would have to conquer the rest of Rome's holdings, whilst the Eastern Mediterranean remained in the hands of Brutus and Cassius and control of the Mediterranean islands rested with Sextus Pompey. On 27 November 43 BC, the Triumvirate was formally established by law, the lex Titia. To finalize their alliance, Octavian married Antony's step-daughter Clodia Pulchra.

The primary objective of the Triumvirate was to avenge Caesar's death and to make war upon his murderers. Before marching against Brutus and Cassius in the East, the Triumvirs decided to eliminate their enemies in Rome. To do so, they employed a legalized form of mass murder: proscription. First used by the Dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla in 82 BC, Sulla drew up a list of his political enemies to purge Rome of opposition to his rule. Any man whose name appeared on the list was stripped of his citizenship and excluded from all protection under the law. Furthermore, reward money was given to anyone who gave information leading to the death of a proscribed man, and any person who killed a proscribed man was entitled to keep part of his property, with the remainder going to the state. No person could inherit money or property from proscribed men, nor could any woman married to a proscribed man remarry after his death.

Like Sulla's proscription before it, the Triumvirate's proscription produced deadly results: one third of the Senate and two thousand Roman knights were killed. Among the most famous outlaws condemned was Cicero, who was executed on December 7. In addition to the political consequences of eliminating opposition, the proscription also restored the State Treasury, which had been depleted by Caesar's civil war the decade before. The fortune of a proscribed man would be confiscated by the state, giving the Triumvirate the funds they needed to pay for the coming war against Brutus and Cassius. When the proceeds from the sale of confiscated estates of the proscribed were insufficient to finance the war, the Triumvirs imposed new taxes, especially on the wealthy. By January 42 BC the proscription officially ended. Though only lasting two months and far less bloody than that of Sulla, the episode traumatized Roman society. To avoid being killed, a number of outlaws fled to either Sextus Pompey in Sicily or to the Liberators in the East. In order to legitimize their own rule, all Senators who survived the proscription were allowed to keep their positions if they swore allegiance to the Triumvirate. In addition, to justify their war of vengeance against the murderers of Caesar, on 1 January 42 BC, the Triumvirate officially deified Caesar as "The Divine Julius".

War against the Liberators

Due to the infighting within the Triumvirate during 43 BC, Brutus and Cassius had assumed control of much of Rome's eastern territories, including amassing a large army. Before the Triumvirate could cross the Adriatic Sea into Greece where the Liberators had stationed their army, the Triumvirate had to address the threat posed by Sextus Pompey and his fleet. From his base in Sicily, Sextus raided the Italian coast and blockaded the Triumvirs. Octavian's friend and admiral Quintus Rufus Salvidienus thwarted an attack by Sextus against the southern Italian mainland at Rhegium, but Salvidienus was then defeated in the resulting naval battle because of the inexperience of his crews. Only when Antony arrived with his fleet was the blockade broken. Though the blockade was defeated, control of Sicily remained in Sextus's hand, but the defeat of the Liberators was the Triumvirate's first priority.

In the summer of 42 BC, Octavian and Antony sailed for Macedonia to face the Liberators with nineteen legions, the vast majority of their army (approximately 100,000 regular infantry plus supporting cavalry and irregular auxiliary units), leaving Rome under the administration of Lepidus. Likewise, the army of the Liberators also commanded an army of nineteen legions; their legions, however, were not at full strength while the legions of Antony and Octavian were. While the Triumvirs commanded a larger number of infantry, the Liberators commanded a larger cavalry contingent. The Liberators, who controlled Macedonia, did not wish to engage in a decisive battle, but rather to attain a good defensive position and then use their naval superiority to block the Triumvirs’ communications with their supply base in Italy. They had spent the previous months plundering Greek cities to swell their war-chest and had gathered in Thrace with the Roman legions from the Eastern provinces and levies from Rome's client kingdoms.

Brutus and Cassius held a position on the high ground along both sides of the via Egnatia west of the city of Philippi. The south position was anchored to a supposedly impassable marsh, while the north was bordered by impervious hills. They had plenty of time to fortify their position with a rampart and a ditch. Brutus put his camp on the north while Cassius occupied the south of the via Egnatia. Antony arrived shortly and positioned his army on the south of the via Egnatia, while Octavian put his legions north of the road. Antony offered battle several times, but the Liberators were not lured to leave their defensive stand. Thus, Antony tried to secretly outflank the Liberators' position through the marshes in the south. This provoked a pitched battle on 3 October 42 BC. Antony commanded the Triumvirate's army due to Octavian's sickness on the day, with Antony directly controlling the right flank opposite Cassius. Because of his health, Octavian remained in camp while his lieutenants assumed a position on the left flank opposite Brutus. In the resulting first battle of Philippi, Antony defeated Cassius and captured his camp while Brutus overran Octavian's troops and penetrated into the Triumvirs' camp but was unable to capture the sick Octavian. The battle was a tactical draw but due to poor communications Cassius believed the battle was a complete defeat and committed suicide to prevent being captured.

Brutus assumed sole command of the Liberator army and preferred a war of attrition over open conflict. His officers, however, were dissatisfied with these defensive tactics and his Caesarian veterans threatened to defect, forcing Brutus to give battle at the second battle of Philippi on 23 October. While the battle was initially evenly matched, Antony's leadership routed Brutus's forces. Brutus committed suicide the day after the defeat and the remainder of his army swore allegiance to the Triumvirate. Over fifty thousand Romans died in the two battles. While Antony treated the losers mildly, Octavian dealt cruelly with his prisoners and even beheaded Brutus's corpse.

The battles of Philippi ended the civil war in favor of the Caesarian faction. With the defeat of the Liberators, only Sextus Pompey and his fleet remained to challenge the Triumvirate's control over the Republic.

(Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_Antony)

The Second Triumvirate

With Antony defeated, the Senate, hoping to eliminate Octavian and the remainder of the Caesarian party, assigned command of the Republic's legions to Decimus. Sextus Pompey, son of Caesar's old rival Pompey Magnus, was given command of the Republic's fleet from his base in Sicily while Brutus and Cassius were granted the governorships of Macedonia and Syria respectively. These appointments attempted to renew the "Republican" cause. However, the eight legions serving under Octavian, composed largely of Caesar's veterans, refused to follow one of Caesar's murderers, allowing Octavian to retain his command. Meanwhile, Antony recovered his position by joining forces with Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, who had been assigned the governorship of Transalpine Gaul and Nearer Spain. Antony sent Lepidus to Rome to broker a conciliation. Though he was an ardent Caesarian, Lepdius had maintained friendly relations with the Senate and with Sextus Pompey. His legions, however, quickly joined Antony, giving him control over seventeen legions, the largest army in the West.

By mid-May, Octavian began secret negotiations to form an alliance with Antony to provide a united Caesarian party against the Liberators. Remaining in Cisalpine Gaul, Octavian dispatched emissaries to Rome in July 43 BC demanding he be appointed Consul to replace Hirtius and Pansa and that the decree declaring Antony a public enemy be rescinded. When the Senate refused, Octavian marched on Rome with his eight legions and assumed control of the city in August 43 BC. Octavian proclaimed himself Consul, rewarded his soldiers, and then set about prosecuting Caesar's murderers. By the lex Pedia, all of the conspirators and Sextus Pompey were convicted in absentia and declared public enemies. Then, at the instigation of Lepidus, Octavian went to Cisalpine Gaul to meet Antony.

In November 43 BC, Octavian, Lepidus, and Antony met near Bononia. After two days of discussions, the group agreed to establish a three man dictatorship to govern the Republic for five years, known as the "Three Man for the Restoration of the Republic" (Latin: "Triumviri Rei publicae Constituendae"), known to modern historians as the Second Triumvirate. In addition, they divided amongst themselves military command of the Republic's armies and provinces: Antony received Gaul, Lepidus Spain, and Octavian (as the junior partner) Africa. The Government of Italy was undivided between the three. The Triumvirate would have to conquer the rest of Rome's holdings, whilst the Eastern Mediterranean remained in the hands of Brutus and Cassius and control of the Mediterranean islands rested with Sextus Pompey. On 27 November 43 BC, the Triumvirate was formally established by law, the lex Titia. To finalize their alliance, Octavian married Antony's step-daughter Clodia Pulchra.

The primary objective of the Triumvirate was to avenge Caesar's death and to make war upon his murderers. Before marching against Brutus and Cassius in the East, the Triumvirs decided to eliminate their enemies in Rome. To do so, they employed a legalized form of mass murder: proscription. First used by the Dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla in 82 BC, Sulla drew up a list of his political enemies to purge Rome of opposition to his rule. Any man whose name appeared on the list was stripped of his citizenship and excluded from all protection under the law. Furthermore, reward money was given to anyone who gave information leading to the death of a proscribed man, and any person who killed a proscribed man was entitled to keep part of his property, with the remainder going to the state. No person could inherit money or property from proscribed men, nor could any woman married to a proscribed man remarry after his death.

Like Sulla's proscription before it, the Triumvirate's proscription produced deadly results: one third of the Senate and two thousand Roman knights were killed. Among the most famous outlaws condemned was Cicero, who was executed on December 7. In addition to the political consequences of eliminating opposition, the proscription also restored the State Treasury, which had been depleted by Caesar's civil war the decade before. The fortune of a proscribed man would be confiscated by the state, giving the Triumvirate the funds they needed to pay for the coming war against Brutus and Cassius. When the proceeds from the sale of confiscated estates of the proscribed were insufficient to finance the war, the Triumvirs imposed new taxes, especially on the wealthy. By January 42 BC the proscription officially ended. Though only lasting two months and far less bloody than that of Sulla, the episode traumatized Roman society. To avoid being killed, a number of outlaws fled to either Sextus Pompey in Sicily or to the Liberators in the East. In order to legitimize their own rule, all Senators who survived the proscription were allowed to keep their positions if they swore allegiance to the Triumvirate. In addition, to justify their war of vengeance against the murderers of Caesar, on 1 January 42 BC, the Triumvirate officially deified Caesar as "The Divine Julius".

War against the Liberators

Due to the infighting within the Triumvirate during 43 BC, Brutus and Cassius had assumed control of much of Rome's eastern territories, including amassing a large army. Before the Triumvirate could cross the Adriatic Sea into Greece where the Liberators had stationed their army, the Triumvirate had to address the threat posed by Sextus Pompey and his fleet. From his base in Sicily, Sextus raided the Italian coast and blockaded the Triumvirs. Octavian's friend and admiral Quintus Rufus Salvidienus thwarted an attack by Sextus against the southern Italian mainland at Rhegium, but Salvidienus was then defeated in the resulting naval battle because of the inexperience of his crews. Only when Antony arrived with his fleet was the blockade broken. Though the blockade was defeated, control of Sicily remained in Sextus's hand, but the defeat of the Liberators was the Triumvirate's first priority.

In the summer of 42 BC, Octavian and Antony sailed for Macedonia to face the Liberators with nineteen legions, the vast majority of their army (approximately 100,000 regular infantry plus supporting cavalry and irregular auxiliary units), leaving Rome under the administration of Lepidus. Likewise, the army of the Liberators also commanded an army of nineteen legions; their legions, however, were not at full strength while the legions of Antony and Octavian were. While the Triumvirs commanded a larger number of infantry, the Liberators commanded a larger cavalry contingent. The Liberators, who controlled Macedonia, did not wish to engage in a decisive battle, but rather to attain a good defensive position and then use their naval superiority to block the Triumvirs’ communications with their supply base in Italy. They had spent the previous months plundering Greek cities to swell their war-chest and had gathered in Thrace with the Roman legions from the Eastern provinces and levies from Rome's client kingdoms.

Brutus and Cassius held a position on the high ground along both sides of the via Egnatia west of the city of Philippi. The south position was anchored to a supposedly impassable marsh, while the north was bordered by impervious hills. They had plenty of time to fortify their position with a rampart and a ditch. Brutus put his camp on the north while Cassius occupied the south of the via Egnatia. Antony arrived shortly and positioned his army on the south of the via Egnatia, while Octavian put his legions north of the road. Antony offered battle several times, but the Liberators were not lured to leave their defensive stand. Thus, Antony tried to secretly outflank the Liberators' position through the marshes in the south. This provoked a pitched battle on 3 October 42 BC. Antony commanded the Triumvirate's army due to Octavian's sickness on the day, with Antony directly controlling the right flank opposite Cassius. Because of his health, Octavian remained in camp while his lieutenants assumed a position on the left flank opposite Brutus. In the resulting first battle of Philippi, Antony defeated Cassius and captured his camp while Brutus overran Octavian's troops and penetrated into the Triumvirs' camp but was unable to capture the sick Octavian. The battle was a tactical draw but due to poor communications Cassius believed the battle was a complete defeat and committed suicide to prevent being captured.

Brutus assumed sole command of the Liberator army and preferred a war of attrition over open conflict. His officers, however, were dissatisfied with these defensive tactics and his Caesarian veterans threatened to defect, forcing Brutus to give battle at the second battle of Philippi on 23 October. While the battle was initially evenly matched, Antony's leadership routed Brutus's forces. Brutus committed suicide the day after the defeat and the remainder of his army swore allegiance to the Triumvirate. Over fifty thousand Romans died in the two battles. While Antony treated the losers mildly, Octavian dealt cruelly with his prisoners and even beheaded Brutus's corpse.

The battles of Philippi ended the civil war in favor of the Caesarian faction. With the defeat of the Liberators, only Sextus Pompey and his fleet remained to challenge the Triumvirate's control over the Republic.

(Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_Antony)

Mark Antony (part 4)

Master of the Roman East

The victory at Philippi left the members of the Triumvirate as masters of the Republic, save Sextus Pompey in Sicily. Upon returning to Rome, the Triumvirate repartioned rule of Rome's provinces between themselves, with Antony as the clear senior partner. He received the largest distribution, governing all of the Eastern provinces while retaining Gaul in the West. Octavian's position improved, as he received Spain, which was taken from Lepidus. Lepdius was then reduced to holding only Africa, and he assumed a clearly tertiary role in the Triumvirate. Rule over Italy remained undivided, but Octavian was assigned the difficult and unpopular task of demobilizing their veterans and providing them with land distributions in Italy. Antony assumed direct control of the East while he installed one of his lieutenants as the ruler of Gaul. During his absence, several of his supporters held key positions at Rome to protect his interests there.

The East was in need of reorganization after the rule of the Liberators in the previous years. In addition, Rome contended with Parthian Empire for dominance of the Near East. The Parthian threat to the Triumvirate's rule was urgent due to the fact that the Parthians supported the Liberators in the recent civil war, which aid included the supply troops at Philippi. As ruler of the East, Antony also assumed responsibility for overseeing Caesar's planned invasion of Parthia to avenge the defeat of Marcus Licinius Crassus at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BC.

In 42 BC, the Roman East was composed of a few directly controlled provinces. The provinces included Macedonia, Asia, Bithynia, Cilicia, Cyprus, Syria, and Cyrenaica. Approximately half of the Eastern territory was controlled by Rome's client kingdoms, nominally independent kingdoms subject to Roman direction. These kingdoms included: Odrysian Thrace in Eastern Europe, the Bosporan Kingdom along the northern coast of the Black Sea, Galatia, Pontus, Cappadocia, Armenia, and several smaller kingdoms in Asia Minor, Judea, Commagene, the Nabataean Kingdom in the Middle East, and Ptolemaic Egypt in Africa.

Activities in the East

Antony spent the winter of 42 BC in Athens, where he ruled generously towards the Greek cities. A proclaimed philhellene ("Friend of all things Greek"), Antony supported Greek culture to win the loyalty of the inhabitants of the Greek East. He attended religious festivals and ceremonies, including initiation into the Eleusinian Mysteries, a secret cult dedicated to the worship of the goddesses Demeter and Persephone. Beginning in 41 BC, he traveled across the Aegean Sea to Anatolia, leaving his friend Lucius Marcius Censorius as governor of Macedonia and Achaea. Upon his arrival in Ephesus in Asia, Antony was worshiped as the god Dionysus born anew. He demanded heavy taxes from the Hellenic cities in return for his pro-Greek culture policies, but exempted those cities which had remained loyal to Caesar during the his civil war and compensated those cities which had suffered under Caesar's assassins, including Rhodes, Lycian, and Tarsus. He granted pardons to all Roman nobles living in the East who had supported the Republican cause, except for Caesar's assassins.

Ruling from Ephesus, Antony consolidated Rome's hegemony in the East, receiving envoys from Rome's client kingdoms and intervening in their dynastic affairs, extracting enormous financial "gifts" from them in the process. Though King Deiotarus of Galatia supported Brutus and Cassius following Caesar's assassination, Antony allowed him to retain his position. He also confirmed Ariarathes X as king of Cappadocia after the execution of his brother Ariobarzanes III of Cappadocia by Cassius before the battle of Philippi. In Hasmonean Judea, several Jewish delegations complained to Antony of the harsh rule of Phasael and Herod, the sons of Rome's assassinated chief Jewish minister Antipater the Idumaean. After Herod offered him a large financial gift, Antony confirmed the brothers in their positions. Antony also began an affair with Glaphyra, the widow of Archelaus the Elder. Archelaus had served as the high priest and ruler of the temple state of Comana in Cappadocia. Through her influence, Antony installed her son Archelaus the Younger as Rome's client king of Cappadocia in 36 BC after he executed Ariarathes X of Cappadocia for disloyalty.

In October 41, Antony requested Rome's chief eastern vassal, the queen of Ptolemaic Egypt Cleopatra, meet him at Tarsus in Cilicia. Antony had first met a young Cleopatra while campaigning in Egypt in 55 BC and again in 48 BC when Caesar had backed her as queen of Egypt over the claims of her half-sister Arsinoe. Cleopatra would bear Caesar a son, Caesarion, in 47 BC and the two living in Rome as Caesar's guests until his assassination in 44 BC. After Caesar's assassination, Cleopatra and Caesarion returned to Egypt, where she named the child as her co-ruler. In 42 BC, the Triumvirate, in recognition for Cleopatra's help towards Publius Cornelius Dolabella in opposition to the Liberators, granted official recognition to Caesarion's position as king of Egypt. Arriving in Tarus aboard of her magnificent ship, Cleopatra invited Antony to a grand banquet to solidify their alliance. As the most powerful of Rome's eastern vassals, Egypt was indispensable in Rome's planned military invasion of the Parthian Empire. At Cleopatra's request, Antony ordered the execution of Arsinoe, who, though marched in Caesar's triumphal parade in 46 BC, had been granted sanctuary at the temple of Artemis in Ephesus. Antony and Cleopatra then spent the winter of 41 BC together in Alexandria. Despite his marriage to Fulvia, Cleopatra bore Antony twin children, Alexander Helios and Cleopatra Selene II, in 40 BC. Antony also granted formal control over Cyprus, which had been under Egyptian control since 47 BC during the turmoil of Caesar's civil war, to Cleopatra in 40 BC as a gift for her loyalty to Rome.

Antony, in his first months in the East, raised money, reorganized his troops, and secured the alliance of Rome's client kingdoms. He also promoted himself as Hellenistic ruler, which won him the affection of the Greek peoples of the East but also made him the target of Octavian's propaganda in Rome. According to some ancient authors, Antony led a carefree life of luxury in Alexandria. Upon learning the Parthian Empire had invaded Rome's territory in early 40 BC, Antony left Egypt for Syria to confront the invasion. However, after a short stay in Tyre, he was forced to sail with his army to Italy to confront Octavian due to Octavian's war against Antony's wife and brother.

Fulvia's Civil War

Following the defeat of Brutus and Cassius, while Antony was stationed in the East Octavian was authority over the West. Octavian's chief responsibility was distributing land to ten of thousands of Caesar's veterans who had fought for the Triumvirate. Additionally, tens of thousands of veterans who had fought for the Republican cause in the also required land grants. This was necessary to ensure they would not support a political opponent of the Triumvirate. However, the Triumvirs did not possess sufficient state-controlled land to allot to the veterans. This left Octavian with two choices: alienating many Roman citizens by confiscating their land, or alienating many Roman soldiers who might back a military rebellion against the Triumvirate's rule. Octavian choose the former. As many as eighteen Roman towns through Italy were affected by the confiscations of 41 BC, with entire populations driven out.

Led by Fulvia, the wife of Antony, the Senators grew hostile towards Octavian over the issue of the land confiscations. According to the ancient historian Cassius Dio, Fulvia was the most powerful woman in Rome at the time. According to Dio, while Publius Servilius Vatia and Lucius Antonius were the Consuls for the year 41 BC, real power was vested in Fulvia. As the mother-in-law of Octavian and the wife of Antony, no actions was taken by the Senate without her support. Fearing Octavian's land grants would cause the loyalty of the Caesarian veterans to shift away from Antony, Fulvia traveled constantly with her children to the new veteran settlements in order to remind the veterans of their debt to Antony. Fulvia also attempted to delay the land settlements until Antony returned to Rome, so that he could share credit for the settlements. With the help of Antony's brother, the Consul of 41 BC Lucius Antonius, Fulvia encouraged the Senate to oppose Octavian's land policies.

The conflict between Octavian and Fulvia caused great political and social unrest throughout Italy. Tensions escalated into open war, however, when Octavian divorced Clodia Pulchra, Fulvia's daughter from her first husband Publius Clodius Pulcher. Outraged, Fulvia, supported by Lucius, raised an army to fight for Antony's rights against Octavian. According to the ancient historian Appian, Fulvia's chief reason for the war was her jealousy of Antony's affairs with Cleopatra in Egypt and desire to draw Antony back to Rome. Lucius and Fulvia took a political and martial gamble in opposing Octavian and Lepidus, however, as the Roman army still depended on the Triumvirs for their salaries. Lucius and Fulvia, supported by their army, marched on Rome and promised the people an end to the Triumvirate in favor of Antony's sole rule. However, when Octavian returned to the city with his army, the pair was forced to retreat to Perusia in Etruria. Octavian placed the city under siege while Lucius waited for Antony's legions in Gaul to come to his aid. Away in the East and embarrassed by Fulvia's actions, Antony gave no instructions to his legions. Without reinforcements, Lucius and Fulvia were forced to surrender in February 40 BC. While Octavian pardoned Lucius for his role in the war and even granted him command in Spain as his chief lieutenant there, Fulvia was forced to flee to Greece with her children. With the war over, Octavian was left in sole control over Italy. When Antony's governor of Gaul died, Octavian took over his legions there, further strengthening his control over the West.

Despite the Parthian Empire's invasion of Rome's eastern territories, Fulvia's civil war forced Antony to leave the East and return to Rome in order to secure his position. Meeting her in Athens, Antony rebuked Fulvia for her actions before sailing on to Italy with his army to face Octavian, laying siege to Brundisium. This new conflict proved untenable for both Octavian and Antony, however. Their centurions, who had become important figures politically, refused to fight due to their shared service under Caesar, with the legions under their command followed suit. Meanwhile in Sicyon, Fulvia died of a sudden and unknown illness. Fulvia's death and the mutiny of their soldiers allowed the triumvirs to effect a reconciliation through a new power sharing agreement in September 40 BC. The Roman world was redivided, with Antony receiving the Eastern provinces, Octavian receiving the Western provinces, and with Lepidus being relegated to a clearly junior position as governor of Africa. This agreement, known as the Treaty of Brundisium, reinforced the Triumvirate and allowed Antony begin preparing for Caesar's long-awaited campaign against the Parthian Empire. As a symbol of their renewed alliance, Antony married Octavia, Octavian's sister, in October 40 BC.

(Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_Antony)

Master of the Roman East

The victory at Philippi left the members of the Triumvirate as masters of the Republic, save Sextus Pompey in Sicily. Upon returning to Rome, the Triumvirate repartioned rule of Rome's provinces between themselves, with Antony as the clear senior partner. He received the largest distribution, governing all of the Eastern provinces while retaining Gaul in the West. Octavian's position improved, as he received Spain, which was taken from Lepidus. Lepdius was then reduced to holding only Africa, and he assumed a clearly tertiary role in the Triumvirate. Rule over Italy remained undivided, but Octavian was assigned the difficult and unpopular task of demobilizing their veterans and providing them with land distributions in Italy. Antony assumed direct control of the East while he installed one of his lieutenants as the ruler of Gaul. During his absence, several of his supporters held key positions at Rome to protect his interests there.

The East was in need of reorganization after the rule of the Liberators in the previous years. In addition, Rome contended with Parthian Empire for dominance of the Near East. The Parthian threat to the Triumvirate's rule was urgent due to the fact that the Parthians supported the Liberators in the recent civil war, which aid included the supply troops at Philippi. As ruler of the East, Antony also assumed responsibility for overseeing Caesar's planned invasion of Parthia to avenge the defeat of Marcus Licinius Crassus at the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BC.

In 42 BC, the Roman East was composed of a few directly controlled provinces. The provinces included Macedonia, Asia, Bithynia, Cilicia, Cyprus, Syria, and Cyrenaica. Approximately half of the Eastern territory was controlled by Rome's client kingdoms, nominally independent kingdoms subject to Roman direction. These kingdoms included: Odrysian Thrace in Eastern Europe, the Bosporan Kingdom along the northern coast of the Black Sea, Galatia, Pontus, Cappadocia, Armenia, and several smaller kingdoms in Asia Minor, Judea, Commagene, the Nabataean Kingdom in the Middle East, and Ptolemaic Egypt in Africa.

Activities in the East

Antony spent the winter of 42 BC in Athens, where he ruled generously towards the Greek cities. A proclaimed philhellene ("Friend of all things Greek"), Antony supported Greek culture to win the loyalty of the inhabitants of the Greek East. He attended religious festivals and ceremonies, including initiation into the Eleusinian Mysteries, a secret cult dedicated to the worship of the goddesses Demeter and Persephone. Beginning in 41 BC, he traveled across the Aegean Sea to Anatolia, leaving his friend Lucius Marcius Censorius as governor of Macedonia and Achaea. Upon his arrival in Ephesus in Asia, Antony was worshiped as the god Dionysus born anew. He demanded heavy taxes from the Hellenic cities in return for his pro-Greek culture policies, but exempted those cities which had remained loyal to Caesar during the his civil war and compensated those cities which had suffered under Caesar's assassins, including Rhodes, Lycian, and Tarsus. He granted pardons to all Roman nobles living in the East who had supported the Republican cause, except for Caesar's assassins.

Ruling from Ephesus, Antony consolidated Rome's hegemony in the East, receiving envoys from Rome's client kingdoms and intervening in their dynastic affairs, extracting enormous financial "gifts" from them in the process. Though King Deiotarus of Galatia supported Brutus and Cassius following Caesar's assassination, Antony allowed him to retain his position. He also confirmed Ariarathes X as king of Cappadocia after the execution of his brother Ariobarzanes III of Cappadocia by Cassius before the battle of Philippi. In Hasmonean Judea, several Jewish delegations complained to Antony of the harsh rule of Phasael and Herod, the sons of Rome's assassinated chief Jewish minister Antipater the Idumaean. After Herod offered him a large financial gift, Antony confirmed the brothers in their positions. Antony also began an affair with Glaphyra, the widow of Archelaus the Elder. Archelaus had served as the high priest and ruler of the temple state of Comana in Cappadocia. Through her influence, Antony installed her son Archelaus the Younger as Rome's client king of Cappadocia in 36 BC after he executed Ariarathes X of Cappadocia for disloyalty.

In October 41, Antony requested Rome's chief eastern vassal, the queen of Ptolemaic Egypt Cleopatra, meet him at Tarsus in Cilicia. Antony had first met a young Cleopatra while campaigning in Egypt in 55 BC and again in 48 BC when Caesar had backed her as queen of Egypt over the claims of her half-sister Arsinoe. Cleopatra would bear Caesar a son, Caesarion, in 47 BC and the two living in Rome as Caesar's guests until his assassination in 44 BC. After Caesar's assassination, Cleopatra and Caesarion returned to Egypt, where she named the child as her co-ruler. In 42 BC, the Triumvirate, in recognition for Cleopatra's help towards Publius Cornelius Dolabella in opposition to the Liberators, granted official recognition to Caesarion's position as king of Egypt. Arriving in Tarus aboard of her magnificent ship, Cleopatra invited Antony to a grand banquet to solidify their alliance. As the most powerful of Rome's eastern vassals, Egypt was indispensable in Rome's planned military invasion of the Parthian Empire. At Cleopatra's request, Antony ordered the execution of Arsinoe, who, though marched in Caesar's triumphal parade in 46 BC, had been granted sanctuary at the temple of Artemis in Ephesus. Antony and Cleopatra then spent the winter of 41 BC together in Alexandria. Despite his marriage to Fulvia, Cleopatra bore Antony twin children, Alexander Helios and Cleopatra Selene II, in 40 BC. Antony also granted formal control over Cyprus, which had been under Egyptian control since 47 BC during the turmoil of Caesar's civil war, to Cleopatra in 40 BC as a gift for her loyalty to Rome.

Antony, in his first months in the East, raised money, reorganized his troops, and secured the alliance of Rome's client kingdoms. He also promoted himself as Hellenistic ruler, which won him the affection of the Greek peoples of the East but also made him the target of Octavian's propaganda in Rome. According to some ancient authors, Antony led a carefree life of luxury in Alexandria. Upon learning the Parthian Empire had invaded Rome's territory in early 40 BC, Antony left Egypt for Syria to confront the invasion. However, after a short stay in Tyre, he was forced to sail with his army to Italy to confront Octavian due to Octavian's war against Antony's wife and brother.

Fulvia's Civil War

Following the defeat of Brutus and Cassius, while Antony was stationed in the East Octavian was authority over the West. Octavian's chief responsibility was distributing land to ten of thousands of Caesar's veterans who had fought for the Triumvirate. Additionally, tens of thousands of veterans who had fought for the Republican cause in the also required land grants. This was necessary to ensure they would not support a political opponent of the Triumvirate. However, the Triumvirs did not possess sufficient state-controlled land to allot to the veterans. This left Octavian with two choices: alienating many Roman citizens by confiscating their land, or alienating many Roman soldiers who might back a military rebellion against the Triumvirate's rule. Octavian choose the former. As many as eighteen Roman towns through Italy were affected by the confiscations of 41 BC, with entire populations driven out.

Led by Fulvia, the wife of Antony, the Senators grew hostile towards Octavian over the issue of the land confiscations. According to the ancient historian Cassius Dio, Fulvia was the most powerful woman in Rome at the time. According to Dio, while Publius Servilius Vatia and Lucius Antonius were the Consuls for the year 41 BC, real power was vested in Fulvia. As the mother-in-law of Octavian and the wife of Antony, no actions was taken by the Senate without her support. Fearing Octavian's land grants would cause the loyalty of the Caesarian veterans to shift away from Antony, Fulvia traveled constantly with her children to the new veteran settlements in order to remind the veterans of their debt to Antony. Fulvia also attempted to delay the land settlements until Antony returned to Rome, so that he could share credit for the settlements. With the help of Antony's brother, the Consul of 41 BC Lucius Antonius, Fulvia encouraged the Senate to oppose Octavian's land policies.