The Old Curiosity Club discussion

This topic is about

Great Expectations

2022 - Great Expectations

>

Great Expectations, Chp. 01-04

date newest »

newest »

newest »

newest »

Peter,

Peter,Thx.

You can always find something about Dickens you hadn't found before on the internet. I wonder how many separate references to Dickens there are?

Pip tells us in chapter four he is living ´under the weight of my wicked secret.´ One wonders how such a heavy burden can be dealt with by such a young child. As we move deeper into the novel we will find out.

Chamomile wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Chamomile wrote: "Mrs. Gargery is an interesting character,

but not a very kind-hearted person. Though I found your point of "her never being allowed to doff her apron" very insigh..."

Hi Chamomile,

Thanks for your kind words. I have just finished the next three chapters and am looking forward to next week's discussion here because we get some clues about Joe's passivity with regard to Mrs. Joe's inclination to henpeck her husband and to vent her spleen on Pip. By the way, I still find it strange that we never get Mrs. Joe's first name. Any ideas on why this is the case or what possible effect this has?

but not a very kind-hearted person. Though I found your point of "her never being allowed to doff her apron" very insigh..."

Hi Chamomile,

Thanks for your kind words. I have just finished the next three chapters and am looking forward to next week's discussion here because we get some clues about Joe's passivity with regard to Mrs. Joe's inclination to henpeck her husband and to vent her spleen on Pip. By the way, I still find it strange that we never get Mrs. Joe's first name. Any ideas on why this is the case or what possible effect this has?

Tristram wrote: "Chamomile wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Chamomile wrote: "Mrs. Gargery is an interesting character,

Tristram wrote: "Chamomile wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Chamomile wrote: "Mrs. Gargery is an interesting character,but not a very kind-hearted person. Though I found your point of "her never being allowed to doff her ..."

Her first name does not matter. This is Victorian times. Since she has a husband, she is Mrs. Joe or Mrs. Gargery. Or Pip's sister. peace, janz

And yet, the story is told by Pip, and I would assume that he might, once in a while, refer to his own sister by her first name, which he doesn't. This tells us a lot about their relationship, and about the unvoiced suffering on both sides.

Peter wrote: "A Tale of Two Cities was about the best of times and the worst of times. Great Expectations has an equally interesting opening paragraph that also contains a key insight into what will be a major f..."

Peter wrote: "A Tale of Two Cities was about the best of times and the worst of times. Great Expectations has an equally interesting opening paragraph that also contains a key insight into what will be a major f..."Peter,

That's such a wonderful observation! I feel I should keep a close eye on the use of palindromes in the book throughout my note-taking now. That's just so neat!

Hi Chamomile

Thanks. If you do find another palindrome in the novel let me know. They are the only ones I am aware of in the text. What the purpose may be is to set up and suggest how one can see and interpret a person in more than one way.

This is a great novel and more than one character will present themselves from more than one point of view.

Thanks for joining us.

Thanks. If you do find another palindrome in the novel let me know. They are the only ones I am aware of in the text. What the purpose may be is to set up and suggest how one can see and interpret a person in more than one way.

This is a great novel and more than one character will present themselves from more than one point of view.

Thanks for joining us.

Tristram wrote: "Chamomile wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Chamomile wrote: "Mrs. Gargery is an interesting character,

Tristram wrote: "Chamomile wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Chamomile wrote: "Mrs. Gargery is an interesting character,but not a very kind-hearted person. Though I found your point of "her never being allowed to doff her ..."

Hello Tristram,

thank you! I agree, that the next few chapters give a much deeper insight into Mrs. Gargery, Joe, and Pip's family backstory. It is interesting how Mrs. Gargery is never referred to by her first name. Janz brings up a good point about women in the Victorian era mostly being called by their husband's and fathers' names, and if the story was in the third person I wouldn't think much of it. However, it feels quite peculiar having the story in first person from Pip and not even hearing his own sisters' first name. I think it's an interesting writing choice to communicate the distance between Pip and Mrs. Gargery and how Pip sees her. For that matter, even chooses to frame her to the reader.

Chamomile wrote: "For that matter, even chooses to frame her to the reader."

And he does so quite successfully because most readers, especially in their first encounter with the novel, hardly feel a lot of sympathy for her. Great Expectations is definitely a book that demands deep or repeated readings.

And he does so quite successfully because most readers, especially in their first encounter with the novel, hardly feel a lot of sympathy for her. Great Expectations is definitely a book that demands deep or repeated readings.

Chamomile wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Chamomile wrote: "Tristram wrote: "Chamomile wrote: "Mrs. Gargery is an interesting character,

but not a very kind-hearted person. Though I found your point of "her never being all..."

Yes. I agree with your comment about how by not revealing Mrs Gargery’s first name it does reveal the enormous gulf between a brother and a sister and a husband and a wife. Even though Mrs Joe is some 20 years older than Pip one would think her first name would slip in somewhere, somehow.

but not a very kind-hearted person. Though I found your point of "her never being all..."

Yes. I agree with your comment about how by not revealing Mrs Gargery’s first name it does reveal the enormous gulf between a brother and a sister and a husband and a wife. Even though Mrs Joe is some 20 years older than Pip one would think her first name would slip in somewhere, somehow.

Hi everybody I'm back! I think so anyway. After some unknown amount of time in the hospital I have now returned home. I can even tell where I am again. It must have been an interesting time I had in between the booster shot/flu shot day, but I have almost no memory of it. The strange thing now is I am having a terrible time walking. I'm considering cutting my right leg off because I can't get a moment of rest it hurts so much. I think if my leg is going to end up so messed up I should be allowed to remember what happened to it, but I don't. I also have little white dots all over both my legs which I'm told is what the hives from the shots have left me with. The hives have gone away and now I'm covered with white dots. It's been a very interesting time. And I'm still going to Michigan and Bronner's Christmas Wonderland in a few weeks if I have to go in a wheel chair. I wish I knew what I did to my leg, it bugs me. And now that I've gotten through all that I'm ready for the illustrations. But I have another thing to say about them before I start posting.

Now about the illustrations which I think I have finally found them all, there are many, many illustrations made by many many artists. While some artists only made two or three (I think) illustrations, other artists had made up to 40, perhaps more than 40, I haven't counted them all yet. This seems like a lot of illustrations that will take up a lot of space, so I may skip some of them, we'll see. Before we start though, there is this commentary on our first illustrator (he's the one with the 40) John McLenan:

"McLenan's series of forty plates in Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization — volume IV: 740 through volume V: 495 (for 24 November 1860 through 3 August 1861) — was not subsequently reproduced in its entirety in either American or British editions. As Edgar Rosenberg notes in the Norton Critical Edition of the novel (1999), although the first installment, containing Chapters 1 and 2 and the first half of Ch. 3, appeared on Saturday, 24 November 1860, in Harper's Weekly, that same installment did not appear in Dickens's own weekly, All the Year Round, until the following Saturday (1 December 1860). The American periodical remained a week in advance of the British until 26 January 1861, when (owing to the long passage on the trans-Atlantic route, which prevented the publishers from getting the advance proof-sheets to the artist in time for him to execute the necessary illustrations) Harper's decided not to run the tenth installment (Chapters 15 and 16). Until this point, the American version, amply illustrated by American artist John McLenan, was certainly "the first edition" of the novel, although lacking half-a-dozen of the early, small-scale illustrations issued between 24 November 1860 and 16 February 1861. As of 2 February 1860, installments in All the Year Round were slightly ahead of those in the New York periodical.

Despite the [British] copyright laws, which forbade prior publication in foreign countries, the serial began with a week's head start in Harper's Weekly: "Splendidly Illustrated by John McLenan. Printed from the Manuscript and early Proof-Sheets purchased from the Author by the Proprietors of 'Harper's Weekly'." The tight schedule to which Dickens was thus forced to work no doubt accounts for the many textual changes he introduced after sending advance proof to New York. Harper's would no doubt have maintained its timetable and beaten All the Year Round to the finishing line if it hadn't been for the omission of the number for January 26....

Typically, McLenan created two very different types of plates to accompany the new Dickens novel, of which he may well have been among the first readers on the American continent: roughly square designs of approximately 11 cm occupying two columns (often in the bottom right section of a page) and small rectangular designs of approximately 5.5 cm wide (in other words, the width of a single column on the four-column page) by 8.5 cm high, often in the bottom left quadrant. The presence of so many smaller illustrations combined with an absence of any illustration in five installments (the 24th, 25th, 26th, the 32nd, and 34th) undermine the veracity of the statement appearing at the head of each installment: "Splendidly Illustrated by John McLenan".

Edgar Rosenberg's "Launching Great Expectations" in the Norton Critical Edition of Charles Dickens's Great Expectations (1999) is the best source of information about the circumstances surrounding the initial trans-Atlantic publication of the novel in serial form.

McLenan's series of forty plates in Harper's Weekly was not subsequently reproduced in British editions, although there was in fact a proto-paperback issued in 1861 with these rare plates:

. . . two editions published by the reprint house of T. B. Peterson & Brothers, Philadelphia, who had bought the rights from Harper: a one-volume edition based on Harper's Weekly and issued in wrappers, which sold for a staggering twenty-five cents--the first paperback of Great Expectations--and a slightly later hardcover, priced at $1.50, featuring McLenan's illustrations from Harper's. [Rosenberg, 423]

The first American edition in book form was published by T. B. Peterson (Philadelphia, 1861) by agreement with Harper & Bros., New York. The book is unusual in that it gives pseudonym ("Boz"), which Dickens dropped in Britain in the early 1840s, last using it for Martin Chuzzlewit. The book's title page, which mentions "thirty-four illustrations from original designs by John McLenan," indicates that its double-columned text (the format used by All the Year Round in Britain) has been "printed from the manuscript and early proof-sheets purchased from the author, for which Charles Dickens has been paid in cash, the sum of one thousand pounds sterling."

Now about the illustrations which I think I have finally found them all, there are many, many illustrations made by many many artists. While some artists only made two or three (I think) illustrations, other artists had made up to 40, perhaps more than 40, I haven't counted them all yet. This seems like a lot of illustrations that will take up a lot of space, so I may skip some of them, we'll see. Before we start though, there is this commentary on our first illustrator (he's the one with the 40) John McLenan:

"McLenan's series of forty plates in Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization — volume IV: 740 through volume V: 495 (for 24 November 1860 through 3 August 1861) — was not subsequently reproduced in its entirety in either American or British editions. As Edgar Rosenberg notes in the Norton Critical Edition of the novel (1999), although the first installment, containing Chapters 1 and 2 and the first half of Ch. 3, appeared on Saturday, 24 November 1860, in Harper's Weekly, that same installment did not appear in Dickens's own weekly, All the Year Round, until the following Saturday (1 December 1860). The American periodical remained a week in advance of the British until 26 January 1861, when (owing to the long passage on the trans-Atlantic route, which prevented the publishers from getting the advance proof-sheets to the artist in time for him to execute the necessary illustrations) Harper's decided not to run the tenth installment (Chapters 15 and 16). Until this point, the American version, amply illustrated by American artist John McLenan, was certainly "the first edition" of the novel, although lacking half-a-dozen of the early, small-scale illustrations issued between 24 November 1860 and 16 February 1861. As of 2 February 1860, installments in All the Year Round were slightly ahead of those in the New York periodical.

Despite the [British] copyright laws, which forbade prior publication in foreign countries, the serial began with a week's head start in Harper's Weekly: "Splendidly Illustrated by John McLenan. Printed from the Manuscript and early Proof-Sheets purchased from the Author by the Proprietors of 'Harper's Weekly'." The tight schedule to which Dickens was thus forced to work no doubt accounts for the many textual changes he introduced after sending advance proof to New York. Harper's would no doubt have maintained its timetable and beaten All the Year Round to the finishing line if it hadn't been for the omission of the number for January 26....

Typically, McLenan created two very different types of plates to accompany the new Dickens novel, of which he may well have been among the first readers on the American continent: roughly square designs of approximately 11 cm occupying two columns (often in the bottom right section of a page) and small rectangular designs of approximately 5.5 cm wide (in other words, the width of a single column on the four-column page) by 8.5 cm high, often in the bottom left quadrant. The presence of so many smaller illustrations combined with an absence of any illustration in five installments (the 24th, 25th, 26th, the 32nd, and 34th) undermine the veracity of the statement appearing at the head of each installment: "Splendidly Illustrated by John McLenan".

Edgar Rosenberg's "Launching Great Expectations" in the Norton Critical Edition of Charles Dickens's Great Expectations (1999) is the best source of information about the circumstances surrounding the initial trans-Atlantic publication of the novel in serial form.

McLenan's series of forty plates in Harper's Weekly was not subsequently reproduced in British editions, although there was in fact a proto-paperback issued in 1861 with these rare plates:

. . . two editions published by the reprint house of T. B. Peterson & Brothers, Philadelphia, who had bought the rights from Harper: a one-volume edition based on Harper's Weekly and issued in wrappers, which sold for a staggering twenty-five cents--the first paperback of Great Expectations--and a slightly later hardcover, priced at $1.50, featuring McLenan's illustrations from Harper's. [Rosenberg, 423]

The first American edition in book form was published by T. B. Peterson (Philadelphia, 1861) by agreement with Harper & Bros., New York. The book is unusual in that it gives pseudonym ("Boz"), which Dickens dropped in Britain in the early 1840s, last using it for Martin Chuzzlewit. The book's title page, which mentions "thirty-four illustrations from original designs by John McLenan," indicates that its double-columned text (the format used by All the Year Round in Britain) has been "printed from the manuscript and early proof-sheets purchased from the author, for which Charles Dickens has been paid in cash, the sum of one thousand pounds sterling."

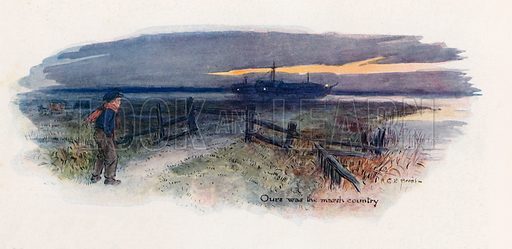

The Gibbet on the Marshes

Chapter 1

John McLenan

1860

Dickens's Great Expectations,

Harper's Weekly 4 (24 November 1860)

Text Illustrated:

Ours was the marsh country, down by the river, within, as the river wound, twenty miles of the sea. My first most vivid and broad impression of the identity of things seems to me to have been gained on a memorable raw afternoon towards evening. At such a time I found out for certain that this bleak place overgrown with nettles was the churchyard; and that Philip Pirrip, late of this parish, and also Georgiana wife of the above, were dead and buried; and that Alexander, Bartholomew, Abraham, Tobias, and Roger, infant children of the aforesaid, were also dead and buried; and that the dark flat wilderness beyond the churchyard, intersected with dikes and mounds and gates, with scattered cattle feeding on it, was the marshes; and that the low leaden line beyond was the river; and that the distant savage lair from which the wind was rushing was the sea; and that the small bundle of shivers growing afraid of it all and beginning to cry, was Pip. [Chapter I]

Commentary:

Since the narrator does not appear within the frame, the reader is left to imagine him: clearly an educated adult rather than a labouring-boy. The reader sees what the mature Pip in his mind's eye sees: the low-lying marsh country, and a chilling symbol of human occupation: a ready means of despatching law-breakers. McLenan provides an atmospheric thumbnail sketch as a headnote vignette to introduce the reader to one of the Bildungsroman's principal settings up to the close of "The First Stage of Pip's Expectations" (concluding in Chapter 19). Implicit in the wood-engraving is the sociological conception that poverty and harsh environment are conducive to criminality. Thus, the illustration reflects the newly-hatched Darwinian principle of "Survival of the Fittest" which the scientist had recently articulated in Origin of Species (1859).

You young dog!" said the man, licking his lips at me, "What fat cheeks you ha' got!

Chapter 1

John McLenan

1860

Text Illustrated:

“You young dog,” said the man, licking his lips, “what fat cheeks you ha’ got.”

I believe they were fat, though I was at that time undersized for my years, and not strong.

“Darn me if I couldn’t eat ’em,” said the man, with a threatening shake of his head, “and if I han’t half a mind to’t!”

I earnestly expressed my hope that he wouldn’t, and held tighter to the tombstone on which he had put me; partly, to keep myself upon it; partly, to keep myself from crying.

“Now lookee here!” said the man. “Where’s your mother?”

“There, sir!” said I.

He started, made a short run, and stopped and looked over his shoulder.

“There, sir!” I timidly explained. “Also Georgiana. That’s my mother.”

“Oh!” said he, coming back. “And is that your father alonger your mother?”

“Yes, sir,” said I; “him too; late of this parish.”

“Ha!” he muttered then, considering. “Who d’ye live with, — supposin’ you’re kindly let to live, which I han’t made up my mind about?”

Commentary:

Following up on his atmospheric headnote vignette for Chapter One McLenan realizes the menacing speech of the self-proclaimed would-be cannibal, which makes his Darwinian identity abundantly clear. Magwitch's first objective, then, is sustenance, but his second (embodied in the file he demands that Pip steal) is almost as important: freedom of movement. Released from the shackles, he will be better able to travel, and will not be marked immediately in curious villagers' eyes as an escaped convict "on the lamb." No wonder, then, that every screenwriter and film-director has chosen to open with this scene as the keynote. And what a providential coincidence: Pip as the blacksmith's brother-in-law has ready access to a file.

"Pip, old chap! You'll do yourself a mischief. It'll stick somewhere. You can't have chawed it, Pip."

Chapter 2

John McLenan

1860

Text Illustrated:

Joe was evidently made uncomfortable by what he supposed to be my loss of appetite, and took a thoughtful bite out of his slice, which he didn’t seem to enjoy. He turned it about in his mouth much longer than usual, pondering over it a good deal, and after all gulped it down like a pill. He was about to take another bite, and had just got his head on one side for a good purchase on it, when his eye fell on me, and he saw that my bread and butter was gone.

The wonder and consternation with which Joe stopped on the threshold of his bite and stared at me, were too evident to escape my sister’s observation.

“What’s the matter now?” said she, smartly, as she put down her cup.

“I say, you know!” muttered Joe, shaking his head at me in very serious remonstrance. “Pip, old chap! You’ll do yourself a mischief. It’ll stick somewhere. You can’t have chawed it, Pip.”

“What’s the matter now?” repeated my sister, more sharply than before.

“If you can cough any trifle on it up, Pip, I’d recommend you to do it,” said Joe, all aghast. “Manners is manners, but still your elth’s your elth.”

By this time, my sister was quite desperate, so she pounced on Joe, and, taking him by the two whiskers, knocked his head for a little while against the wall behind him, while I sat in the corner, looking guiltily on."

"And you know what wittles is?"

Chapter 1

F. A. Fraser. c. 1877

An illustration for the Household Edition of Dickens's Great Expectations

Text Illustrated:

Show us where you live," said the man. "Pint out the place!"

I pointed to where our village lay, on the flat in-shore among the alder-trees and pollards, a mile or more from the church.

The man, after looking at me for a moment, turned me upside down, and emptied my pockets. There was nothing in them but a piece of bread. When the church came to itself, — for he was so sudden and strong that he made it go head over heels before me, and I saw the steeple under my feet, — when the church came to itself, I say, I was seated on a high tombstone, trembling while he ate the bread ravenously.

"Ha!" he muttered then, considering. "Who d’ye live with, — supposin’ you’re kindly let to live, which I han’t made up my mind about?"

"My sister, sir, — Mrs. Joe Gargery, — wife of Joe Gargery, the blacksmith, sir."

"Blacksmith, eh?" said he. And looked down at his leg.

After darkly looking at his leg and me several times, he came closer to my tombstone, took me by both arms, and tilted me back as far as he could hold me; so that his eyes looked most powerfully down into mine, and mine looked most helplessly up into his.

"Now lookee here," he said, "the question being whether you’re to be let to live. You know what a file is?"

"Yes, sir."

"And you know what wittles is?"

"Yes, sir."

After each question he tilted me over a little more, so as to give me a greater sense of helplessness and danger. [Chapter I, 2]

Commentary:

One of the novel’s most memorable scenes occurs within the opening chapter, as Pip, playing near his patents’s grave in the village churchyard, suddenly encounters Abel Magwitch. The convicted felon, who has just escaped from the nearby prison hulks (a temporary holding location prior to his transportation to Australia), ravenously menaces the skinny boy with vague threats of eating him. But then Magwitch, realizing the raggedly dressed boy is an orphan, takes pity on him, even as he seeks to exploit the boy’s relationship with the local blacksmith. Terrified, Pip agrees to bring the savage stranger both food (in Magwitch’s East End dialect, “wittles”) and the file necessary to severe his fetters.

The scene has numerous parallels in the many illustrated editions issued after the novel’s 1861 serialization in the unillustrated weekly magazine All the Year Round. In fact, the first such realization of this memorable scene was published in the United States in Harper's Weekly prior to the story’s initial appearance in Dickens’s own literary journal. McLenan, one of the house artists for Harper’s weekly, however, presents the figures as rigid and static, whereas Fraser in the British Household Edition shows the child and the adult interacting. Magwitch stoops slightly to bring his face close to the boy’s, as if studying him. The 1876 wood-engraving presents the pair as both opposites (free child, escaped convict; small, fearful child versus bear-like, slightly curious adult) and related by their poverty, their isolation, their both being social Outsiders.

However, since McLennan’s illustration appeared only in the United States fifteen years earlier, the British Household Edition illustrator had probably never seen or been influenced by it. The program which would have influenced Fraser was that by Marcus Stone in the 1862 Illustrated Library Edition. Unfortunately, Stone provided Fraser with no model as he focused on Pip’s social climbing and the romantic scenes, between Pip and Miss Havisham (frontispiece) and between Pip and Estella. Later series, however, appear to have been influenced by Fraser’s choice of subject here, as “Pip and the Convict” is one of the novel’s most frequently illustrated moments in all later editions, a nod towards late Victorian social realism.

The Terrible Stranger in the Churchyard

F. W. Pailthorpe

c. 1900

Etching

Dickens's Great Expectations, Garnett edition

Text Illustrated:

"Ha!" he muttered then, considering. "Who d'ye live with, — supposin' you're kindly let to live, which I han't made up my mind about?"

"My sister, sir, — Mrs. Joe Gargery, — wife of Joe Gargery, the blacksmith, sir."

"Blacksmith, eh?" said he. And looked down at his leg.

After darkly looking at his leg and me several times, he came closer to my tombstone, took me by both arms, and tilted me back as far as he could hold me; so that his eyes looked most powerfully down into mine, and mine looked most helplessly up into his.

"Now lookee here," he said, "the question being whether you're to be let to live. You know what a file is?"

"Yes, sir."

"And you know what wittles is?"

"Yes, sir."

After each question he tilted me over a little more, so as to give me a greater sense of helplessness and danger.

"You get me a file." He tilted me again. "And you get me wittles." He tilted me again. "You bring 'em both to me." He tilted me again. "Or I'll have your heart and liver out." He tilted me again.

I was dreadfully frightened, and so giddy that I clung to him with both hands, and said, "If you would kindly please to let me keep upright, sir, perhaps I shouldn't be sick, and perhaps I could attend more."

He gave me a most tremendous dip and roll, so that the church jumped over its own weathercock. Then, he held me by the arms, in an upright position on the top of the stone, and went on in these fearful terms: — [Chapter I]

Commentary:

Despite the importance of the opening scene to the novel as a whole, surprisingly not all the nineteenth-century illustrators of Great Expectations have attempted it — and none with the intense emotion and energy of Harry Furniss. Although they may not have had access to them, the American illustrations of Pip and the convict in the 1860s by John McLenan in Harper's Weekly and Sol Eytinge, Jr., in the Diamond Edition are useful reference points for both Furniss's kinetic description of that fateful meeting on the marshes, and Pailthorpe's more benign handling of the escaped convict.

The self-proclaimed would-be cannibal makes his Darwinian identity abundantly clear in Frederick W. Pailthorpe's initial regular engraving: Magwitch is a survivor who will do whatever it takes to survive. His first objective, then, is sustenance, but his second (embodied in the file he demands that Pip steal) is almost as important: freedom of movement. Released from the shackles, he will be better able to travel, and will not be marked immediately in curious villagers' eyes as an escaped convict "on the lamb." No wonder, then, that every screenwriter and film-director has chosen to open with this scene as the keynote.

Pailthorpe's boy is startled, but not terrified, and the convict's gesture seems intended to allay Pip's apprehension rather than intensify his terror. The illustrator juxtaposes the grimy, swamp-soaked escapee behind the very tombstone of Pip's parents, as if signalling that he will be a surrogate parent and provider. The skeletal tree in the background underscores the gothic nature of this opening scene, redolent with death and decay. Despite the caricatural style, Pailthorpe has realistically set the stage and clothed his characters, even if he has given them somewhat theatrical gestures.

Pip and The Convict

Sol Eytinge

First illustration for Dickens's Great Expectations in the single volume A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations in the Ticknor & Fields (Boston, 1867) Diamond Edition.

Commentary:

In this first full-page dual character study for the second novel in the compact American publication, a bearded Magwitch confronts the small boy sitting on the enormous tombstone in the churchyard, exactly as in the memorable opening chapter of the novel. This somewhat static illustration conveys a good sense of the initiating incident in terms of setting, particularly in terms of the weed-infested graveyard, but not in terms of the terror that the protagonist experienced as Magwitch seemed to rise from the graves at the side of the church porch moments before.

Mesmerised by the ragged felon, the boy sits atop a mouldering gravemarker, the words "Sacred to the Memory of" barely decipherable. Thus, the precise passage illustrated would seem to be this, even though the convict is not yet eating the boy's heel of bread:

When the church came to itself — for he was so sudden and strong that he made it go head over heels before me, and I saw the steeple under my feet — when the church came to itself, I say, I was seated on a high tombstone, trembling, while he ate the bread ravenously. [[Chapter One, 1 December 1860, All the Year Round]

In "Pip and the Convict," a full-page dual character study in the compact American publication, a bearded Magwitch, faithfully depicted as "A fearful man, all in grey, with a great iron on his leg" and a rag tied about his head in lieu of a hat, and "broken" shoes, confronts a boy in short jacket and trousers. The one illustration to which Eytinge would have access in preparing this composition, John McLenan's "You young dog!" said the man, licking his lips at me, "What fat cheeks you ha' got!" in the 24 November 1860 number of Harper's Weekly, is more vigorous in its sense of the convict and the setting, although McLenan's Pip is rather too big for the "undersized" boy of the text. In McLenan's middle-distance picture, the convict is indeed ragged, torn by weeds, and voracious; in Eytinge's close-up the salient feature is the boy's expression of amazement.

Joe and Mrs. Joe Gargarey

Sol Eytinge

Second illustration Dickens's Great Expectations in the single volume A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations in the Ticknor & Fields (Boston, 1867) Diamond Edition.

In this second full-page dual character study for the second novel in the compact American publication, the belligerent Mrs. Joe, Pip's surviving sibling, scolds her affable husband in the parlor. Although Harper's illustrator John McLenan provided an ample series of forty plates for Eytinge's study, the 1860-61 magazine serialization offers no precise equivalent for the scene that Eytinge has given us since McLenan does not show the couple together, characteristic as the poses in Eytinge's illustration may be. Much "given to government" (i. e. despotism), Mrs. Joe under Eytinge's hand is an angular, waspish, domineering woman of middle-age (although in the text she is likely in her late twenties only). As in the text, Mrs. Joe is a harridan — "not a good-looking woman" (ch. 2), but as "tall and bony" as Joe is mild and good-natured. Her flaxen-haired husband, the village blacksmith, is a solid, well-built, rotund man — in Eytinge's illustration apparently somewhat younger than his shrewish wife. Seated at the kitchen table, a large mug in his right hand, Joe leans slightly back as his wife in "a coarse apron" upbraids him. Thus, the precise passage illustrated would seem to be this:

By this time, my sister was quite desperate, so she pounced on Joe, and, taking him by the two whiskers, knocked his head for a little while against the wall behind him: while I sat in the corner, looking guiltily on.

'Now, perhaps you'll mention what's the matter,' said my sister, out of breath, 'you staring great stuck pig.' [Chapter Two]

Pip's Struggle with the Escaped Convict

Harry Furniss

1910

Dickens's Great Expectations, Vol. 14 of the Charles Dickens Library Edition

Text Illustrated:

"Ha!" he muttered then, considering. "Who d'ye live with, — supposin' you're kindly let to live, which I han't made up my mind about?"

"My sister, sir, — Mrs. Joe Gargery, — wife of Joe Gargery, the blacksmith, sir."

"Blacksmith, eh?" said he. And looked down at his leg.

After darkly looking at his leg and me several times, he came closer to my tombstone, took me by both arms, and tilted me back as far as he could hold me; so that his eyes looked most powerfully down into mine, and mine looked most helplessly up into his.

"Now lookee here," he said, "the question being whether you're to be let to live. You know what a file is?"

"Yes, sir."

"And you know what wittles is?"

"Yes, sir."

After each question he tilted me over a little more, so as to give me a greater sense of helplessness and danger.

"You get me a file." He tilted me again. "And you get me wittles." He tilted me again. "You bring 'em both to me." He tilted me again. "Or I'll have your heart and liver out." He tilted me again.

I was dreadfully frightened, and so giddy that I clung to him with both hands, and said, "If you would kindly please to let me keep upright, sir, perhaps I shouldn't be sick, and perhaps I could attend more."

He gave me a most tremendous dip and roll, so that the church jumped over its own weathercock. Then, he held me by the arms, in an upright position on the top of the stone, and went on in these fearful terms

— [Chapter One]

Commentary:

Despite the importance of the opening scene to the novel as a whole, surprisingly not all the illustrators of Great Expectations have attempted it — and none with the intense emotion and energy of Harry Furniss. Although he may not have had access to them, the American illustrations of Pip and the convict in the 1860s by John McLenan in Harper's Weekly and Sol Eytinge, Jr., in the Diamond Edition are useful reference points for Furniss's kinetic description of that fateful meeting on the marshes.

The illustration, occupying a whole page some five pages after the moment occurs in the letterpress, is vignetted rather than framed, its jagged edges complementing the violence of the illustration and the indistinctness of the background, full of menace as objects familiar to Pip in daylight become unrecognizable in the growing darkness. The full-page illustration, conveying Pip's remembered emotion starkly, elaborates upon the visual theme of the man running through the graveyard, a thumbnail vignette in the upper right-hand corner of Characters in the Story on the title-page.

Although the scene is set at dusk in the early winter, the dark background, imitative of the dark plates by Phiz in Bleak House, also reflects the haziness of memory. Seen in the shaded area behind the dynamic figures of Pip on a gravestone and Magwitch, forcing him back, are the static church, its porch, and various gravestones and monuments. The scene is generalized, and does not reflect the particulars of the churchyard at Cooling, Kent, the actual scene that Dickens, then living at nearby Gadshill, Rochester, had in mind. Compared to earlier versions by F. W. Pailthorpe, F. A. Fraser, and Charles Brock, Furniss's interpretation of the dramatic meeting of the blacksmith's boy and the felon in the highly atmospheric setting of the churchyard before sunset is particularly baroque in capturing a precise moment in action, as well as impressionistic in its rendering of the figures, the tangle of weeds in the foreground adding significantly to the mysterious and malevolent atmosphere of the accompanying text. Charles Green in the Gads hill Edition (Chapman and Hall, 1898) does not deal with the churchyard scene, and therefore offered Furniss no precedent, and it is unlikely that Furniss would have been able to study the early American illustrations for the novel by John McLenan and Sol Eytinge, Jr.

Working in the visual tradition of the novel established in 1862 by Marcus Stone, Dickens's chosen artistic partner for the Illustrated Library Edition, Furniss would have had to consult three subsequent British illustrated editions for comparable scenes, namely F. A. Fraser's 1876 Household Edition illustration "And you know what wittles is?", capturing a far less violent moment in Pip's first meeting with escaped convict Abel Magwitch; F. W. Pailthorpe's 1885 illustration from the Robson and Kerslake edition, The Terrible Stranger in the Churchyard, a caricature in the Cruikshank-Phiz tradition rather than an attempt at the new realism, but with some admirably realized background details; and H. M. Brock's 1903 "Imperial Edition" pen-and-ink drawing I made bold to say 'I am glad you enjoy it.'. By the time that the reader encounters the illustration facing page 8 in the first chapter, Pip is still too terrified to eat his slice of bread since he is convinced that he "must have something in reserve for [his] dreadful acquaintance". Thus, Furniss must have felt that only such violence as he has depicted would convince the reader of the boy's continuing to be terrified at the prospect of meeting Magwitch again, "and his ally the still more dreadful young man.

Mrs. Gargery on the Ram-page

Felix O. C. Darley

c. 1861

Dickens's Great Expectations, Garnett edition

Text Illustrated:

My sister, Mrs. Joe, with black hair and eyes, had such a prevailing redness of skin that I sometimes used to wonder whether it was possible she washed herself with a nutmeg-grater instead of soap. She was tall and bony, and almost always wore a coarse apron, fastened over her figure behind with two loops, and having a square impregnable bib in front, that was stuck full of pins and needles. She made it a powerful merit in herself, and a strong reproach against Joe, that she wore this apron so much. Though I really see no reason why she should have worn it at all; or why, if she did wear it at all, she should not have taken it off, every day of her life. . . . .

“Mrs. Joe has been out a dozen times, looking for you, Pip. And she’s out now, making it a baker’s dozen.”

“Is she?”

“Yes, Pip,” said Joe; “and what’s worse, she’s got Tickler with her.”

At this dismal intelligence, I twisted the only button on my waistcoat round and round, and looked in great depression at the fire. Tickler was a wax-ended piece of cane, worn smooth by collision with my tickled frame.

“She sot down,” said Joe, “and she got up, and she made a grab at Tickler, and she Ram-paged out. That’s what she did,” said Joe, slowly clearing the fire between the lower bars with the poker, and looking at it; “she Ram-paged out, Pip.”

“Has she been gone long, Joe?” I always treated him as a larger species of child, and as no more than my equal.

“Well,” said Joe, glancing up at the Dutch clock, “she’s been on the Ram-page, this last spell, about five minutes, Pip. She’s a-coming! Get behind the door, old chap, and have the jack-towel betwixt you.” [Chapter II]

Commentary:

Darley did not include any of the novel's female characters in his two frontispieces for the two-volume Sheldon and Company Great Expectations (1861). This vigorous portrait of Pip's severe sister may therefore represent a piece that he developed as a possible frontispiece, but rejected almost three decades before the publication of his folio of photogravures entitled Character Sketches from Dickens (1888). Published without commentary or text, the image of Mrs. Joe, caught in the midst of the action on her front porch, requires that the reader supply the "Text Illustrated." Darlay implies her "ram-paging" nature by the rooster and the dog whom she has terrified as she sweeps out of the door, looking for the errant Pip. Since she dominates the action of the early chapters of the novel, that she makes relatively few appearances in the various programs of illustration (1860-1910) is rather surprising.

"You're not a false imp? You brought no one with you?"

Chapter 3

John McLenan

1860

Text Illustrated:

“I’ll eat my breakfast afore they’re the death of me,” said he. “I’d do that, if I was going to be strung up to that there gallows as there is over there, directly afterwards. I’ll beat the shivers so far, I’ll bet you.”

He was gobbling mincemeat, meatbone, bread, cheese, and pork pie, all at once: staring distrustfully while he did so at the mist all round us, and often stopping—even stopping his jaws—to listen. Some real or fancied sound, some clink upon the river or breathing of beast upon the marsh, now gave him a start, and he said, suddenly,—

“You’re not a deceiving imp? You brought no one with you?”

“No, sir! No!”

“Nor giv’ no one the office to follow you?”

“No!”

“Well,” said he, “I believe you. You’d be but a fierce young hound indeed, if at your time of life you could help to hunt a wretched warmint hunted as near death and dunghill as this poor wretched warmint is!”

Something clicked in his throat as if he had works in him like a clock, and was going to strike. And he smeared his ragged rough sleeve over his eyes.

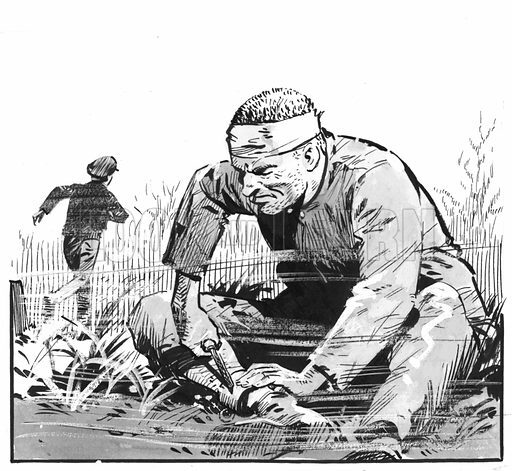

But he was down on the rank wet grass, filing at his iron like a madman

John McLenan

Chapter 3

1860

Harper's Weekly (1 December 1860)

Text Illustrated:

I indicated in what direction the mist had shrouded the other man, and he looked up at it for an instant. But he was down on the rank wet grass, filing at his iron like a madman, and not minding me or minding his own leg, which had an old chafe upon it and was bloody, but which he handled as roughly as if it had no more feeling in it than the file. I was very much afraid of him again, now that he had worked himself into this fierce hurry, and I was likewise very much afraid of keeping away from home any longer. I told him I must go, but he took no notice, so I thought the best thing I could do was to slip off. The last I saw of him, his head was bent over his knee and he was working hard at his fetter, muttering impatient imprecations at it and at his leg. The last I heard of him, I stopped in the mist to listen, and the file was still going.

Commentary:

On the same broadsheet page the reader of the periodical encountered the convict's sawing away at his fetters amidst the overgrown vegetation of the marshes near the old battery (presumably from the Napoleonic Wars) in the upper-left, and Pumblechook, respectably dressed Pip, and his crone-like older sister in "Oh, Un-cle Pum-ble-chook! This is kind!" in the lower right. The juxtaposition is telling as it contrasts the outlaw, the felon escaped from transportation and forced to sleep rough, outside and homeless, and his unwilling accomplice, fashionably dressed for a bourgeois festival indoors with his family, unpleasant though they may be. McLenan might have chosen to place Pip in the upper frame, but deliberately chose to depict Magwitch as a social isolate, a man on the run, approaching the condition of a hunted animal: like a runaway slave, in fact.

"Oh, Un-cle Pum-ble-chook! This is kind!"

John McLenan

1860

Harper's Weekly (1 December 1860)

Text Illustrated:

I opened the door to the company,—making believe that it was a habit of ours to open that door,—and I opened it first to Mr. Wopsle, next to Mr. and Mrs. Hubble, and last of all to Uncle Pumblechook. N.B. I was not allowed to call him uncle, under the severest penalties.

“Mrs. Joe,” said Uncle Pumblechook, a large hard-breathing middle-aged slow man, with a mouth like a fish, dull staring eyes, and sandy hair standing upright on his head, so that he looked as if he had just been all but choked, and had that moment come to, “I have brought you as the compliments of the season—I have brought you, Mum, a bottle of sherry wine—and I have brought you, Mum, a bottle of port wine.”

Every Christmas Day he presented himself, as a profound novelty, with exactly the same words, and carrying the two bottles like dumb-bells. Every Christmas Day, Mrs. Joe replied, as she now replied, “O, Un—cle Pum-ble—chook! This is kind!” Every Christmas Day, he retorted, as he now retorted, “It’s no more than your merits. And now are you all bobbish, and how’s Sixpennorth of halfpence?” meaning me.

Commentary:

Like many of Dickens's other humorous caricatures, Pumblechook the seedsman and self-important connection of the Gargeries is something of a mechanism rather than even a one-dimensional character. Wind him up on Christmas Day, and he inevitably utters the same greeting at the door of the cottage. Mrs. Joe once again greets "Uncle" Pumblechook as he ritualistically presents his anticipated contributions to the Christmas dinner: two bottles of wine. His selections are like him: rotund, heavy, and ponderous. Since neither port nor sherry is something that one would normally consume with the meal, but afterward, Dickens sets up the scene in which the company discovers that somehow "vittles" (a savoury port pie) and a bottle have been purloined. Pumblechook magisterially presents the bottles as if this is an unusual act of generosity, but, as Pip explains, he brings the same kind of wine every Christmas. And McLenan does not spare hyperbole in dealing with either the portly, pompous bourgeois or his crone-like hostess, correctly dressed in middle-class Victorian fashion. Although Dickens's Mrs. Joe may be no beauty, she is certainly younger than McLenan implies.

Pip Does Not Enjoy His Christmas Dinner

Chapter 4

Harry Furniss.

Dickens's Great Expectations, Charles Dickens Library Edition

Text Illustrated:

Among this good company I should have felt myself, even if I hadn't robbed the pantry, in a false position. Not because I was squeezed in at an acute angle of the table-cloth, with the table in my chest, and the Pumblechookian elbow in my eye, nor because I was not allowed to speak (I didn't want to speak), nor because I was regaled with the scaly tips of the drumsticks of the fowls, and with those obscure corners of pork of which the pig, when living, had had the least reason to be vain. No; I should not have minded that, if they would only have left me alone. But they wouldn't leave me alone. They seemed to think the opportunity lost, if they failed to point the conversation at me, every now and then, and stick the point into me. I might have been an unfortunate little bull in a Spanish arena, I got so smartingly touched up by these moral goads.

It began the moment we sat down to dinner. Mr. Wopsle said grace with theatrical declamation — as it now appears to me, something like a religious cross of the Ghost in Hamlet with Richard the Third — and ended with the very proper aspiration that we might be truly grateful. Upon which my sister fixed me with her eye, and said, in a low reproachful voice, "Do you hear that? Be grateful."

"Especially," said Mr. Pumblechook, "be grateful, boy, to them which brought you up by hand."

Mrs. Hubble shook her head, and contemplating me with a mournful presentiment that I should come to no good, asked, "Why is it that the young are never grateful?" This moral mystery seemed too much for the company until Mr. Hubble tersely solved it by saying, "Naterally wicious." Everybody then murmured "True!" and looked at me in a particularly unpleasant and personal manner.

Commentary:

Whereas the original Illustrated Library Edition and Household Edition illustrations do not reference this awkward moment in Pip's tense home-life, as he anticipates any moment being arrested for the theft of the pork pie and the file, Harry Furniss realizes most effectively this supremely comic passage which builds up to the consumption of the tar-water. Dickens's character comedy and social satire of the overreaching bourgeois Pumblechook and his theatrical companion, the village clerk and aspiring Shakespearean actor, Wopsle, appear in action, so to speak, rather than in a static portrait, as in Eytinge's illustration for the Diamond Edition.

Other illustrators have focused on the character comedy and social satire which the pompous, self-aggrandizing seed merchant Pumblechook presents throughout the early chapters, with McLenan and Pailthorpe both exaggerating his corpulence and complacency to contrast the lean, insecure Pip and his shrewish sister so effectively drawn by F. O. C. Darley in an early American piracy of the novel. Whereas other illustrators seem to have preferred scenes involving just a few characters, particularly interchanges between Pip and Magwitch and between Pip and Joe, in these opening chapters, Furniss depicts the oppressive social milieu in which Pip has grown up.

Furniss as an impressionistic illustrator attempts to convey (as so often the earlier illustrators do not) the acute discomfort, embarrassment, and terror that Pip feels as a child through the postures and expressions of Pumblechook (left) and the hawk-faced Wopsle (right of centre). In what we today would label a situation comedy, Furniss effectively translates the first-person reminiscence of the child-victim of the Christmas dinner, extreme right, between the bulk of the shock-haired Joe and the scowling visage and watchful gaze of his dictatorial sister; Furniss virtually dismisses the wheelwright, Mr. Hubble, as a non-entity, cramming him in behind Wopsle's outstretched arm, but showing the other adult diners as larger-than-life caricatures to give the reader a sense of the much-put-upon child's perspective.

One must read the illustration analytically, thumbing through the text to compare Dickens's handling of the scene and descriptions of the characters to sort out who is who. The "well-to-do corn chandler" is not a mere misshapen ogre with an enormous alcoholic nose and massive belly (as he is in McLenan); rather, Furniss characterizes him as large and domineering. Pailthorpe's corpulent Pumblechook (from a later scene) in May I — May I? comes closest to realising Dickens's comical description of Joe's prosperous relative as "a large, hard-breathing middle-aged slow man, with a mouth like a fish, dull staring eyes, and sandy hair standing upright on his head". Wopsle, on the other hand, is easily distinguished by his Roman nose and energetic gesticulation, his clothing suggesting the garb of an Anglican minister, although as clerk he is a mere lay-preacher and clergyman's assistant, and therefore does not wear a clerical collar.

Pumblechook and Wopsle

Sol Eytinge

Third illustration for Dickens's Great Expectations in A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations in the Ticknor & Fields (Boston, 1867) Diamond Edition.

Commentary:

In this third full-page dual character study for the second novel in the compact American publication, the parish clerk, Mr. Wopsle, yearns to be an actor, while "Uncle" Pumblechook —not, in fact, Mrs. Joe's uncle, but Joe's — is perfectly content with being a village seed merchant and the family's most successful connection, "a well-to-do corn-chandler" with his own "chaise-cart." According to Pip's descriptions of the pair in chapter 4, Pumblechook is a large-eyed, slow-moving, somewhat out-of-breath, fish-mouthed, sandy-haired, self-important humbug, while Mr. Wopsle has a theatrical air, a bald pate, and a Roman nose. Eytinge depicts them as the serious, balding, thin man, reading a book, and a contrasting fat man, both middle-aged.

The Harper's illustrator John McLenan provided Eytinge with a cartoon-like model of the corn merchant in "Oh, Un-cle Pum-ble-chook! This is kind!". However, McLenan does not bother to depict Wopsle at all in his forty woodcut illustrations. Given their relative positions at the table in Eytinge's illustration, the precise passage illustrated would seem to be this:

.......A little later on in the dinner, Mr. Wopsle reviewed the sermon with some severity, and intimated — in the usual hypothetical case of the Church being "thrown open" — what kind of sermon he would have given them. After favouring them with some heads of that discourse, he remarked that he considered the subject of the day's homily, ill-chosen; which was the less excusable, he added, when there were so many subjects 'going about.'

'True again,' said Uncle Pumblechook. 'You've hit it, sir! Plenty of subjects going about, for them that know how to put salt upon their tails. That's what's wanted. A man needn't go far to find a subject, if he's ready with his salt-box.' Mr. Pumblechook added, after a short interval of reflection, "Look at Pork alone. There's a subject! If you want a subject, look at Pork!'

'True, sir. Many a moral for the young,' returned Mr. Wopsle; and I knew he was going to lug me in, before he said it; 'might be deduced from that text.' [Chapter Four]

When authors are taught by circumstances that it is wiser for them to write serially, readers may be very sure that it is wiser for them to read serially. [Harper's Weekly, Nov., 1860]

But, then, of course the editors of the "American Journal of Civilization" would extol the virtues of serial reading since they were about to offer in spoonful's to the readers of Harper's Weekly a "New Story" from the hand of Britain's greatest living author. The illustrations created by the journal's house-artist, John McLenan, reveal his enthusiasm for the new story and his delight in Dickens's comic characters, such a welcome departure from the general seriousness of Little Dorrit and so much in the vein of the earlier works of the "Fielding of the Nineteenth Century," notably Pickwick. However, illustrating serially necessarily means creating in ignorance, for the illustrator if not in the confidence of the author (Phiz had such advance information, McLenan did not) cannot know whether a minor character such as Wopsle will occur again, acquiring a new significance, if not developing wholly. Such is the case with Wopsle in Great Expectations, for McLenan must have assumed that, like the Hubbles, fellow guests at the Gargerys' Christmas dinner, Wopsle was not worthy of visual realization — that he was simply stuffing for the moment when the tableful of guests assembled are shocked by Pip's substituting tar-water for brandy in the bottle from which Pumblechook has just taken a glass.

McLenan understandably regarded Pumblechook as a comic figure, depicting him as an obese bourgeois on spindly legs and carrying the signs of his economic superiority over the Gargerys, his annual offering of port and sherry. Like many of Dickens's lesser comic figures, Pumblechook behave so predictably as to be a human machine, and thereby becomes less than human, a mere platitude-making mechanism:

......."I have brought you as the compliments of the season — I have brought you, Mum, a bottle of sherry wine — and I have brought you, Mum, a bottle of port wine."

Every Christmas Day he presented himself, as a profound novelty, with exactly the same words, and carrying the two bottles like dumb-bells. Every Christmas Day, Mrs. Joe replied, as she now replied, "Oh, Un-cle Pum-ble-chook! This is kind!" [Chapter 4]

This was, in fact, the very moment which McLenan chose for realization at the head of the novel's second installment: a thin, almost skeletal Mrs. Joe greeting the Humpty-Dumpty figure of the corn merchant at the door. McLenan undoubtedly realized Pumblechook's comic potential, and drew him accordingly — as a cartoon. Eytinge, on the other hand, would have known to what ends both Pumblechook and Wopsle come later in the novel, probably having read and re-read the 1861 novel before completing his 1867 Diamond Edition commission to illustrate it in the new, "Sixties" manner, with modeled, three-dimensional figures and a more realistic handling.

And we wouldn't want to miss an illustration by Kyd:

"Mr. Pumblechook"

J. Clayton Clarke ("Kyd")

Watercolour

c. 1900

"Mr. Pumblechook"

J. Clayton Clarke ("Kyd")

Watercolour

c. 1900

Pip and the convict

Jack Keay

I never heard of the artist before so I looked him up:

Jack [John] (Edwin) Keay (1907-1999). Artist who contributed a variety of illustrations and covers to Look and Learn. When he signed his work, it was usually as “Jack Keay”. He was born in King’s Norton, Worcestershire, on 10 May 1907. Little is known about Keay’s career, but he was a popular book cover artist who worked for Pan, Panther, Hutchinson, Fontana and Four Square in the 1957-62 period. Keay illustrated a number of books in the 1970s and 1980s, including The Change of Life by Muriel E. Landau (1971), Gunfighters of the Wild West by Eric Inglefield (1978), American Civil War by Philip Clark (1988), American War of Independence by Philip Clark (1988) and Viking Explorers by Rupert Matthews (1989). He died in Hounslow, London, in 1999, aged 92.

That's all I can find about him.

Pat Nicolle artist

Once again I never heard of the artist and once again I looked him up:

Born in Hampstead, London, on 15 November 1907, Nicolle was educated in Birmingham and London. Artistic talent was in the family (his older brother Jack was also an illustrator). After working in the book trade for some years he began freelancing illustrations for catalogues, magazines and books. He returned to illustration after serving for six years with the Royal Engineers and was spotted by Leonard Matthews, who invited him to draw comic strips for Amalgamated Press, his first appearing in 1950.

Over the next decade he drew ‘Robin Hood’, ‘The Three Musketeers’, ‘Ivanhoe’, ‘The Prisoner of Zenda’, ‘Under the Golden Dragon’ (later reprinted in Eagle as ‘The Last of the Saxon Kings’), and his longest-running strip, featuring Ginger Tom, a young squire, which ran for nearly four years in Knockout (1956-60). He contributed to The Bible Story, Look and Learn and Treasure. Nicolle’s expertise on medieval history, his eye for detail and his willingness to spend many hours researching his subjects helped make him one of the finest and longest-serving artists to grace the pages of Look and Learn, his association lasting the full twenty years it ran. From cut-away centre spreads of ancient buildings and the history of armour to the comic strip ‘Sir Nigel’, Nicolle never failed to impress. Nicolle, who was a founder member of the Arms and Armour Society, retired when Look and Learn folded. He died in November 1996, aged 87.

Frances Brundage artist

Another unknown artist to me:

Frances Isabelle Lockwood Brundage (1854–1937) was an American illustrator best known for her depictions of attractive and endearing children on postcards, valentines, calendars, and other ephemera. She received an education in art at an early age from her father, Rembrandt Lockwood. Her professional career in illustration began at seventeen when her father abandoned his family and she was forced to seek a livelihood.

She sold her first professional work – a sketch illustrating a poem by Louisa May Alcott – to the author. She illustrated books and ephemera such as paper dolls, postcards, valentines, prints, trade cards, and calendars. Her book illustrations were sometimes published as postcards.

In 1886, she married the artist, William Tyson Brundage, and gave birth to one child, Mary Frances Brundage, who died in 1891 aged 17 months. The Brundages resided in Washington, D.C., summered at Cape Ann, Massachusetts, and, in later years, moved to Brooklyn, New York. They occasionally worked jointly on projects.

Brundage produced works with an emphasis on attractive and endearing Victorian children. At the same time she was also published by Wolff Hagelberg, Berlin, in near equal amount. Maud Humphrey was the preferred artist with American publishers in the 1890s, but Brundage was chosen by Tuck, London, and Hagelberg, Berlin, international art publishers, for their American market publication. As a result, Brundage had extensive early Euro and UK international postcard publication, more than any other children artist except Ellen Clapsaddle and Harriett M. Bennett, as well as a large lines of U.S. postcards. Those postcards and the Tuck and the Hagelberg lines of fancy diecut valentines made Brundage the largest presence in U.S. art. By 1910, she was working for New York publisher, Samuel Gabriel Company, and later, Akron, Ohio publisher, Saalfield. Brundage died on March 28, 1937, aged 82 years.

Brundage illustrated children's classics such as the novels of Louisa May Alcott, Johanna Spyri, and Robert Louis Stevenson, and traditional literary collections such as The Arabian Nights and the stories of King Arthur and Robin Hood. She was a prolific artist, and, in her late 60s, was producing as many as twenty books annually. Her work is highly collectible.

That second color illustration, the first one of the convict, has me staring. With that jacket and collared shirt unbuttoned, the convict looks more like a professor down and out on his luck. Oxford? The jacket even has elbow patches. I hadn't realized England dressed their prisoners this well.

That second color illustration, the first one of the convict, has me staring. With that jacket and collared shirt unbuttoned, the convict looks more like a professor down and out on his luck. Oxford? The jacket even has elbow patches. I hadn't realized England dressed their prisoners this well.

Wow, Kyd did a number on Pumblechook. That's a 7 o' clock shadow.

Wow, Kyd did a number on Pumblechook. That's a 7 o' clock shadow. One of the things I'm noticing is the wildly differing physical interpretations of these characters. Joe varies from old to young. And the convict from burly to slight of build . . . and at times a bit too professorial.

But it's early. Let's see if they come together as the story progresses?

Xan wrote: "We've come a long way from Nicholas Nickleby, haven't we?"

We surely have - Dickens is growing better and better.

We surely have - Dickens is growing better and better.

Kim wrote: "Hi everybody I'm back! I think so anyway. After some unknown amount of time in the hospital I have now returned home. I can even tell where I am again. It must have been an interesting time I had i..."

It's so good to have you back, Kim! Make sure that you stay safe and healthy!!!

It's so good to have you back, Kim! Make sure that you stay safe and healthy!!!

That last illustration by Frances Brundage I don't like. Pip looks like he's three years old and wouldn't be out wandering around by himself. And the convict is around twelve years old and would scare no one. I can't imagine this was one of her children's scenes for greeting cards and calendars she seemed to spend most of her time on.

Kim wrote: "

But he was down on the rank wet grass, filing at his iron like a madman

John McLenan

Chapter 3

1860

Harper's Weekly (1 December 1860)

Text Illustrated:

I indicated in what direction the mis..."

It is interesting to see how the various illustrators tackle the challenge of what the criminal looked like. Without Browne to lead the way, we get quite the variety. First, it seems the only common feature is the headband. It’s hard to pick a “favourite” or perhaps a better phrase would be “most representative” image that matches the description in the text.

Should we vote on it?

My vote goes to John McLenan.

But he was down on the rank wet grass, filing at his iron like a madman

John McLenan

Chapter 3

1860

Harper's Weekly (1 December 1860)

Text Illustrated:

I indicated in what direction the mis..."

It is interesting to see how the various illustrators tackle the challenge of what the criminal looked like. Without Browne to lead the way, we get quite the variety. First, it seems the only common feature is the headband. It’s hard to pick a “favourite” or perhaps a better phrase would be “most representative” image that matches the description in the text.

Should we vote on it?

My vote goes to John McLenan.

Kim wrote: "

Frances Brundage artist

Another unknown artist to me:

Frances Isabelle Lockwood Brundage (1854–1937) was an American illustrator best known for her depictions of attractive and endearing childr..."

Good grief! Is it me or are the representations of Pip not at all like I picture him?

Frances Brundage artist

Another unknown artist to me:

Frances Isabelle Lockwood Brundage (1854–1937) was an American illustrator best known for her depictions of attractive and endearing childr..."

Good grief! Is it me or are the representations of Pip not at all like I picture him?

Kim wrote: "

Pip in the marshes

Charles Edmund Brock"

Now, this coloured impression of the marshes I find quite evocative.

Pip in the marshes

Charles Edmund Brock"

Now, this coloured impression of the marshes I find quite evocative.

Isn't he about 12 years old, maybe a year or two older? I base this mainly on his reaction to, and awareness of, Estella. A little too interested in her for an 8 or 9 year old. Most of the illustrations have him looking like he's 8 years old.

Isn't he about 12 years old, maybe a year or two older? I base this mainly on his reaction to, and awareness of, Estella. A little too interested in her for an 8 or 9 year old. Most of the illustrations have him looking like he's 8 years old.

Xan wrote: "Isn't he about 12 years old, maybe a year or two older? I base this mainly on his reaction to, and awareness of, Estella. A little too interested in her for an 8 or 9 year old. Most of the illustra..."

Hi Xan

Good question. I just did a quick search and Dickens does mark the passage of Pip’s life reasonably carefully through the novel. Evidently (according to a couple of sources I checked) we can assume his age ranges between 6-18 in Book One.

That seems about right to me. I hesitate to go further into the text due to spoilers so let’s hang on a bit longer.

What I can say is I agree with you on your observations. Many of the illustrations make Pip look very young (or is it the way he is portrayed as dressing?) As for Estella … soon.

Hi Xan

Good question. I just did a quick search and Dickens does mark the passage of Pip’s life reasonably carefully through the novel. Evidently (according to a couple of sources I checked) we can assume his age ranges between 6-18 in Book One.

That seems about right to me. I hesitate to go further into the text due to spoilers so let’s hang on a bit longer.

What I can say is I agree with you on your observations. Many of the illustrations make Pip look very young (or is it the way he is portrayed as dressing?) As for Estella … soon.

Xan wrote: "Isn't he about 12 years old, maybe a year or two older? I base this mainly on his reaction to, and awareness of, Estella. A little too interested in her for an 8 or 9 year old. Most of the illustra..."

I have been asking myself the same question, Xan. At the beginning of the novel, Pip acts so naively that I would put down his age at 9 or 10 at the highest. This would make him a little older than 11 when he first meets Estella, wouldn't it? I think it is in connection with Pip's letter to Joe that we learn that roughly one year has passed since the memorable Christmas we first clap eyes on Pip.

I have been asking myself the same question, Xan. At the beginning of the novel, Pip acts so naively that I would put down his age at 9 or 10 at the highest. This would make him a little older than 11 when he first meets Estella, wouldn't it? I think it is in connection with Pip's letter to Joe that we learn that roughly one year has passed since the memorable Christmas we first clap eyes on Pip.

Peter wrote: "Kim wrote: "

But he was down on the rank wet grass, filing at his iron like a madman

John McLenan

Chapter 3

1860

Harper's Weekly (1 December 1860)

Text Illustrated:

I indicated in what direc..."

I like Harry Furniss's and Pat Nicolle's convict best but that is probably because I always have Anthony Hopkins in mind when I think of the convict (from one of the novel's adaptations). As for Uncle Pumblechook, I prefer John McLenan's illustration: The perfect mixture of dumbness and pent-up aggression.

But he was down on the rank wet grass, filing at his iron like a madman

John McLenan

Chapter 3

1860

Harper's Weekly (1 December 1860)

Text Illustrated:

I indicated in what direc..."

I like Harry Furniss's and Pat Nicolle's convict best but that is probably because I always have Anthony Hopkins in mind when I think of the convict (from one of the novel's adaptations). As for Uncle Pumblechook, I prefer John McLenan's illustration: The perfect mixture of dumbness and pent-up aggression.

Thanks, Tristram. I missed the passing of one year in the letter passage. So much for focusing. That helps. I think it is in this week's readings, when Pip and Joe are alone again, this time in the forge, that Joe mentions Pip's small size. That might help explain how small Pip is in some of the illustrations. We seem to learn a lot when Pip and Joe are alone and can freely talk to one another.

Thanks, Tristram. I missed the passing of one year in the letter passage. So much for focusing. That helps. I think it is in this week's readings, when Pip and Joe are alone again, this time in the forge, that Joe mentions Pip's small size. That might help explain how small Pip is in some of the illustrations. We seem to learn a lot when Pip and Joe are alone and can freely talk to one another.

John wrote: "Xan wrote: "Here is an article (and photos) about the Hoo peninsula, where the opening scenes of GE take place."

John wrote: "Xan wrote: "Here is an article (and photos) about the Hoo peninsula, where the opening scenes of GE take place."That’s great. Place a little darkness over those pictures and seems to fit what Dickens put in my mind.

I thought so too! But in my case it was probably David Lean (in his film adaptation) as much as Dickens who put it in my head.

From The Life of Charles Dickens by John Forster:

GREAT EXPECTATIONS.

The Tale of Two Cities was published in 1859; the series of papers collected as the Uncommercial Traveller were occupying Dickens in 1860; and it was while engaged in these, and throwing off in the course of them capital "samples" of fun and enjoyment, he thus replied to a suggestion that he should let himself loose upon some single humorous conception, in the vein of his youthful achievements in that way.

"For a little piece I have been writing—or am writing; for I hope to finish it to-day—such a very fine, new, and grotesque idea has opened upon me, that I begin to doubt whether I had not better cancel the little paper, and reserve the notion for a new book. You shall judge as soon as I get it printed. But it so opens out before me that I can see the whole of a serial revolving on it, in a most singular and comic manner."

This was the germ of Pip and the convict, which at first he intended to make the groundwork of a tale in the old twenty-number form, but for reasons perhaps fortunate brought afterwards within the limits of a less elaborate novel.

"Last week," he wrote on the 4th of October 1860, "I got to work on the new story. I had previously very carefully considered the state and prospects of All the Year Round, and, the more I considered them, the less hope I saw of being able to get back, now, to the profit of a separate publication in the old 20 numbers." (A tale, which at the time was appearing in his serial, had disappointed expectation.)

"However I worked on, knowing that what I was doing would run into another groove; and I called a council of war at the office on Tuesday. It was perfectly clear that the one thing to be done was, for me to strike in. I have therefore decided to begin the story as of the length of the Tale of Two Cities on the first of December—begin publishing, that is. I must make the most I can out of the book. You shall have the first two or three weekly parts to-morrow. The name is Great Expectations. I think a good name?"

Two days later he wrote: "The sacrifice of Great Expectations is really and truly made for myself. The property of All the Year Round is far too valuable, in every way, to be much endangered. Our fall is not large, but we have a considerable advance in hand of the story we are now publishing, and there is no vitality in it, and no chance whatever of stopping the fall; which on the contrary would be certain to increase. Now, if I went into a twenty-number serial, I should cut off my power of doing anything serial here for two good years—and that would be a most perilous thing. On the other hand, by dashing in now, I come in when most wanted; and if Reade and Wilkie follow me, our course will be shaped out handsomely and hopefully for between two and three years. A thousand pounds are to be paid for early proofs of the story to America."

A few more days brought the first installment of the tale, and explanatory mention of it. "The book will be written in the first person throughout, and during these first three weekly numbers you will find the hero to be a boy-child, like David. You will not have to complain of the want of humour as in the Tale of Two Cities. I have made the opening, I hope, in its general effect exceedingly droll. I have put a child and a good-natured foolish man, in relations that seem to me very funny. Of course I have got in the pivot on which the story will turn too—and which indeed, as you remember, was the grotesque tragi-comic conception that first encouraged me. To be quite sure I had fallen into no unconscious repetitions, I read David Copperfield again the other day, and was affected by it to a degree you would hardly believe."

It may be doubted if Dickens could better have established his right to the front rank among novelists claimed for him, than by the ease and mastery with which, in these two books of Copperfield and Great Expectations, he kept perfectly distinct the two stories of a boy's childhood, both told in the form of autobiography. A subtle penetration into character marks the unlikeness in the likeness; there is enough at once of resemblance and of difference in the position and surroundings of each to account for the divergences of character that arise.

The opening of the tale, in a churchyard down by the Thames, as it winds past desolate marshes twenty miles to the sea, of which a masterly picture in half a dozen lines will give only average example of the descriptive writing that is everywhere one of the charms of the book. It is strange, as I transcribe the words, with what wonderful vividness they bring back the very spot on which we stood when he said he meant to make it the scene of the opening of his story—Cooling Castle ruins and the desolate Church, lying out among the marshes seven miles from Gadshill!

"My first most vivid and broad impression . . . on a memorable raw afternoon towards evening . . . was . . . that this bleak place, overgrown with nettles, was the churchyard, and that the dark flat wilderness beyond the churchyard, intersected with dykes and mounds and gates, with scattered cattle feeding on it, was the marshes; and that the low leaden line beyond, was the river; and that the distant savage lair from which the wind was rushing, was the sea. . . . On the edge of the river . . . only two black things in all the prospect seemed to be standing upright . . . one, the beacon by which the sailors steered, like an unhooped cask upon a pole, an ugly thing when you were near it; the other, a gibbet with some chains hanging to it which had once held a pirate.

GREAT EXPECTATIONS.

The Tale of Two Cities was published in 1859; the series of papers collected as the Uncommercial Traveller were occupying Dickens in 1860; and it was while engaged in these, and throwing off in the course of them capital "samples" of fun and enjoyment, he thus replied to a suggestion that he should let himself loose upon some single humorous conception, in the vein of his youthful achievements in that way.

"For a little piece I have been writing—or am writing; for I hope to finish it to-day—such a very fine, new, and grotesque idea has opened upon me, that I begin to doubt whether I had not better cancel the little paper, and reserve the notion for a new book. You shall judge as soon as I get it printed. But it so opens out before me that I can see the whole of a serial revolving on it, in a most singular and comic manner."

This was the germ of Pip and the convict, which at first he intended to make the groundwork of a tale in the old twenty-number form, but for reasons perhaps fortunate brought afterwards within the limits of a less elaborate novel.