The Old Curiosity Club discussion

Little Dorrit

>

Little Dorrit Chapters Chp 12-14

Chapter 13

Patriarchal

“[Arthur] sat before his dying fire, sorrowful to think upon the way by which he had come to that night, yet not strewing poison on the way by which other man had come to it. But he should have missed so much and that his time of life should look so far about him for any staff to bear him company upon his download journey and share it, was a just regret.”

This is a very long chapter. In order for us to digest it I have decided to break it up into six sections. My logic is that by seeing each section by itself we will better understand the text.

Casby’s Connections

In the first section we take a look at Mr. Casby and see how he connects to various threads already established in the novel. We learn in the first paragraph of this chapter that once upon a time Mr. Casby’s daughter Flora was the beloved of Arthur. We also learn that Arthur believes that the case of Mr. Dorrit, Father of the Marshalsea, is hopeless. Thus, Arthur resigns his idea of helping Mr. Dorrit gain his freedom. Arthur takes himself to the home of Mr. Casby and as the door opens we find ourselves in yet another home that reflects its owner. The furniture is formal and grave, but well-kept. The most distinctive part of the house is the “grave clock, ticking.” We read that the fire “ticked in the grate.” Next we read that Arthur’s “loud watch in his pocket ticked audibly.” It appears that time may become an important part of what will occur in this chapter.

When Arthur sees Mr. Casby we learn that he had changed very little since Arthur saw him last. Casby is“so gray, so slow, so quiet, so compassionate so very bumpy in the head, Patriarch was the word for him.” We also learn that Casby was formally the Town-agent to Lord Decimus Tite Barnacle. Here we learn a connection to the Barnacle family. Next we learn that Casby has been in contact with Mr. Flintwinch. The next fact we learn is that Mr. Casby and Arthur’s parents “we’re not on friendly terms.” Casby assures Arthur, however, that the past is gone in the past is done. Casby then tells Arthur that he visits his mother occasionally and admired the her strength of mind as she bears her trials. As readers we wonder what these trials could be. Last, we learn that it was through Casby that Little Dorrit was introduced to Arthur’s mother.

Thoughts

Let us remember that as we entered the house the key symbol was the sound of a clock ticking. Time. I think it is important to remember the concept of time as we read through this chapter. What Dickens has done in the beginning of this chapter is create and explain some of the intricate connections among characters. To what extent does the information of the intertwined connections of characters in the beginning of this paragraph help you understand how the novel might progress in the coming chapters?

What is your opinion of Mr. Pancks? To what extent do you think that his physical appearance helped you to make that opinion?

We learn from Pancks that the connection between Casby and the Barnacles is one of property, and how Casby is a terrible man to those he has power over. Clearly these two men have a past together that is not one of kindness to those less fortunate than themselves. What conflicts might be developed by Dickens in the coming chapters regarding these men and their treatment of the poor?

Section 2

Flora

I will call this section Flora for the obvious reason that Flora, Casby’s daughter, arrives on the scene. We learn that Flora had only been married a few months before her husband died. This part of the chapter is very humourous and a welcome relief to much of what has come before in the novel. We could, in fact, call this section comic relief. Perhaps the best phrase in this section is when Dickens tells us that when Arthur’s eyes “ fell upon the subject of his old passion that it shivered and broke to pieces.” Arthur realizes that Flora, who had seemed enchanting in all she said and thought, was diffuse and silly.” The conversation between Arthur and Flora — or perhaps Flora at Arthur — is meant to make Flora a very unappealing person. Flora, on the other hand, seems to think she is in enchanting. As an outlier, I wonder how much Dickens drew upon his changing feelings towards his wife Catherine when he penned the description of Flora.

Section 3

The Dinner Table

Arthur stays for dinner and the conversation is painful to recall. Pancks talks about Bleeding Heart Yard and calls it “a troublesome property.” Arthur tries to be civil. There is little place for Arthur to hide with Flora on one side and Pancks on the other.

Thoughts

What do you think the main purpose of having Arthur be part of this dinner party was?

Has anything that was discussed at the dinner table either helped fill in the blanks of Arthur’s situation in London or hinted as to what might occur in the coming chapters?

Section 4

Homeward Bound

Arthur makes his escape from the Casby house accompanied by Mr. Pancks. More and more we find Pancks is a man who values money more than anything in the world. If we reflect back to his physical description earlier in this chapter we can see how Dickens aligns the pursuit of money with a person who described as dirty and greasy. A subtle concept perhaps, but we always need to pay attention to not only what a person says but their physical appearance as well.

Section 5

The Accident

As Arthur leaves Pancks and begins his solitary way home he becomes aware of an accident on the streets. Immediately, Arthur asks about the person’s state of health. This is a very clear example of how Arthur is very different from the Pancks of the world.

It turns out that the person in the accident is a Frenchman. It further turns out that this injured person is from Marseilles. At this point, our antenna may indeed begin to quiver. Arthur learns from the doctor that while the injury is serious, the person will live. Dickens portrays the kindness and generosity of Arthur.

Thoughts

Who might this person be from France? If so, why might have Dickens re-introduced his character into the novel?

Section 6

Arthur At Home Alone

As the chapter concludes Dickens turns his focus on Arthur. Dickens calls Arthur a dreamer, and a man of gentle and good thoughts even though his life has been one of pain and loss. A very telling comment comes in the following description. “Arthur sat before his dying fire, sorrowful to think upon the way by which he had come to that night… How soon I too shall pass through such changes, and be gone!”

Arthur is in the process of reviewing his life and sees little to look forward to, or even to look back upon. He questions what he has to look forward to in life. Dickens ends the chapter with the following:

“[Arthur’s] door was softly opened, and these spoken words startled him, and came as if they were an answer:

‘Little Dorrit.”

Thoughts

This chapter has given us further information about Arthur’s past, revealed his dislike of how the poor are treated, and demonstrated his ongoing kindness to those he knows and even strangers he encounters late at night on the streets of London. At this point in the novel what is you opinion of Arthur?

Dickens tells us that Arthur is seated before a ‘dying fire.” To what extent could this be foreshadowing of a disaster that might befall Arthur?

Patriarchal

“[Arthur] sat before his dying fire, sorrowful to think upon the way by which he had come to that night, yet not strewing poison on the way by which other man had come to it. But he should have missed so much and that his time of life should look so far about him for any staff to bear him company upon his download journey and share it, was a just regret.”

This is a very long chapter. In order for us to digest it I have decided to break it up into six sections. My logic is that by seeing each section by itself we will better understand the text.

Casby’s Connections

In the first section we take a look at Mr. Casby and see how he connects to various threads already established in the novel. We learn in the first paragraph of this chapter that once upon a time Mr. Casby’s daughter Flora was the beloved of Arthur. We also learn that Arthur believes that the case of Mr. Dorrit, Father of the Marshalsea, is hopeless. Thus, Arthur resigns his idea of helping Mr. Dorrit gain his freedom. Arthur takes himself to the home of Mr. Casby and as the door opens we find ourselves in yet another home that reflects its owner. The furniture is formal and grave, but well-kept. The most distinctive part of the house is the “grave clock, ticking.” We read that the fire “ticked in the grate.” Next we read that Arthur’s “loud watch in his pocket ticked audibly.” It appears that time may become an important part of what will occur in this chapter.

When Arthur sees Mr. Casby we learn that he had changed very little since Arthur saw him last. Casby is“so gray, so slow, so quiet, so compassionate so very bumpy in the head, Patriarch was the word for him.” We also learn that Casby was formally the Town-agent to Lord Decimus Tite Barnacle. Here we learn a connection to the Barnacle family. Next we learn that Casby has been in contact with Mr. Flintwinch. The next fact we learn is that Mr. Casby and Arthur’s parents “we’re not on friendly terms.” Casby assures Arthur, however, that the past is gone in the past is done. Casby then tells Arthur that he visits his mother occasionally and admired the her strength of mind as she bears her trials. As readers we wonder what these trials could be. Last, we learn that it was through Casby that Little Dorrit was introduced to Arthur’s mother.

Thoughts

Let us remember that as we entered the house the key symbol was the sound of a clock ticking. Time. I think it is important to remember the concept of time as we read through this chapter. What Dickens has done in the beginning of this chapter is create and explain some of the intricate connections among characters. To what extent does the information of the intertwined connections of characters in the beginning of this paragraph help you understand how the novel might progress in the coming chapters?

What is your opinion of Mr. Pancks? To what extent do you think that his physical appearance helped you to make that opinion?

We learn from Pancks that the connection between Casby and the Barnacles is one of property, and how Casby is a terrible man to those he has power over. Clearly these two men have a past together that is not one of kindness to those less fortunate than themselves. What conflicts might be developed by Dickens in the coming chapters regarding these men and their treatment of the poor?

Section 2

Flora

I will call this section Flora for the obvious reason that Flora, Casby’s daughter, arrives on the scene. We learn that Flora had only been married a few months before her husband died. This part of the chapter is very humourous and a welcome relief to much of what has come before in the novel. We could, in fact, call this section comic relief. Perhaps the best phrase in this section is when Dickens tells us that when Arthur’s eyes “ fell upon the subject of his old passion that it shivered and broke to pieces.” Arthur realizes that Flora, who had seemed enchanting in all she said and thought, was diffuse and silly.” The conversation between Arthur and Flora — or perhaps Flora at Arthur — is meant to make Flora a very unappealing person. Flora, on the other hand, seems to think she is in enchanting. As an outlier, I wonder how much Dickens drew upon his changing feelings towards his wife Catherine when he penned the description of Flora.

Section 3

The Dinner Table

Arthur stays for dinner and the conversation is painful to recall. Pancks talks about Bleeding Heart Yard and calls it “a troublesome property.” Arthur tries to be civil. There is little place for Arthur to hide with Flora on one side and Pancks on the other.

Thoughts

What do you think the main purpose of having Arthur be part of this dinner party was?

Has anything that was discussed at the dinner table either helped fill in the blanks of Arthur’s situation in London or hinted as to what might occur in the coming chapters?

Section 4

Homeward Bound

Arthur makes his escape from the Casby house accompanied by Mr. Pancks. More and more we find Pancks is a man who values money more than anything in the world. If we reflect back to his physical description earlier in this chapter we can see how Dickens aligns the pursuit of money with a person who described as dirty and greasy. A subtle concept perhaps, but we always need to pay attention to not only what a person says but their physical appearance as well.

Section 5

The Accident

As Arthur leaves Pancks and begins his solitary way home he becomes aware of an accident on the streets. Immediately, Arthur asks about the person’s state of health. This is a very clear example of how Arthur is very different from the Pancks of the world.

It turns out that the person in the accident is a Frenchman. It further turns out that this injured person is from Marseilles. At this point, our antenna may indeed begin to quiver. Arthur learns from the doctor that while the injury is serious, the person will live. Dickens portrays the kindness and generosity of Arthur.

Thoughts

Who might this person be from France? If so, why might have Dickens re-introduced his character into the novel?

Section 6

Arthur At Home Alone

As the chapter concludes Dickens turns his focus on Arthur. Dickens calls Arthur a dreamer, and a man of gentle and good thoughts even though his life has been one of pain and loss. A very telling comment comes in the following description. “Arthur sat before his dying fire, sorrowful to think upon the way by which he had come to that night… How soon I too shall pass through such changes, and be gone!”

Arthur is in the process of reviewing his life and sees little to look forward to, or even to look back upon. He questions what he has to look forward to in life. Dickens ends the chapter with the following:

“[Arthur’s] door was softly opened, and these spoken words startled him, and came as if they were an answer:

‘Little Dorrit.”

Thoughts

This chapter has given us further information about Arthur’s past, revealed his dislike of how the poor are treated, and demonstrated his ongoing kindness to those he knows and even strangers he encounters late at night on the streets of London. At this point in the novel what is you opinion of Arthur?

Dickens tells us that Arthur is seated before a ‘dying fire.” To what extent could this be foreshadowing of a disaster that might befall Arthur?

Chapter 14

Little Dorrit‘s Party

“Little Dorrit had put his hand to her lips, and would have kneeled to him, but he gently prevented her, and replaced her in her chair. “

This chapter begins with Arthur alone in his rooms. But he is not alone for long as little Dorrit appears at his door. Amy looks into Arthur’s dim room but what she sees is a place that is spacious and grandly furnished. Compared to her residence at the Marshalsea it certainly must appear to be grand. Arthur is struck with the fact that Amy is at his door at midnight, but Amy is not alone, because she has brought someone with her called Maggy. Arthur hurriedly prepares a fire to warm Amy. Amy tells Arthur that she prefers the name Little Dorrit and so we shall call her that for the remainder of the novel. :-) Maggy calls Little Dorrit “little mother“ which tells us that Little Dorrit is not only a mother to her father and her siblings but her love and kindness extends to another poor and homeless person outside the prison walls as well. Maggy is a simple creature and Dickens refers to her as a “big child.” As Little Dorrit looks at Arthur, Dickens tells us that she thought “what a good father he would be.” Hmmm. That’s interesting. Perhaps we need to tuck Little Dorrit’s private thought away in our minds.

The main reason that Little Dorrit has come is to thank Arthur for his kindness towards her brother Tip. She knows, however, that she must phrase her words in such a way that Arthur will both know what little Dorrit is saying but not actually acknowledge the same. Arthur is, of course, curious why little Dorrit and Maggy are out so late. We learn that Maggy and Little Dorrit have been to see her sister perform at a theatre. Little Dorrit has not told her father where she really was. Her father believes that Little Dorrit has been to a party. She confesses to Arthur that she has really never been to a party and says “I hope there is no harm in it. I could never have been of any use, if I had not pretended a little.” When we read these words it is evident that little Dorrit realizes her life in some ways is much like her sister’s, that she, much like her sister, is an actress, a person who acts, who pretends, who performs for the benefit of others. For those of us who, to this point in the novel dislike Mr Dorrit, there is more sorrow for Little Dorrit. She must know that her father should wonder where his daughter is until after midnight, and so Little Dorrit must invent a series of misdirections to pacify him. Whether Little Dorrit is at Mrs.Clennam’s, at a theatrical production, or within the Marshalsea with her father, her life is one of creating a series of false artifices.

Little Dorrit tells Arthur that there are three reasons she has come to him. The first is to thank Arthur for his kindness towards Tip without really identifying the fact that she knows how good Arthur is to her and her family. The second reason is to tell Arthur that she believes Mr. Flintwinch has been watching her. Little Dorrit tells Arthur that she has met him twice, both times near home, both times at night when she was returning to the Marshalsea. She reports to Arthur that Flintwinch never says anything when he passes her but rather seems to look away. These encounters make Little Dorrit anxious and she asks for Arthur’s advice as to what she should do. Arthur tells her he will speak to Affery on her behalf. The third reason little Dorrit wanted to see Arthur is to request that he not reveal any information about her actions or life outside the jail.

Thoughts

This midnight meeting between Arthur and Little Dorrit may seem strange to the reader. Why do you think Dickens included it in the story?

A new character by the name of Maggy has been introduced into the plot. She is a person who Little Dorrit apparently is also raising, or has at least befriended. What purpose could Maggy possibly serve in this novel?

This is the first time we have seen Arthur and Little Dorrit have a personal and extended conversation. It happens at midnight. Usually, in a Victorian novel, such a meeting would be inappropriate for a male and female who are not married. Were you at all concerned, upset, or curious as to why Dickens created this element of the plot?

When Little Dorrit and Maggy leave Arthur’s residence he discretely follows them until he assumes they find shelter near the Marshalsea. Such is not the case. Little Dorrit and Maggy quietly knock on a door but no one answers. This means they must find shelter on the streets of London until the morning when the Marshalsea will open its doors. The night brings challenges and encounters with other poor and homeless people. As daylight approaches, Little Dorrit and Maggy find a church’s door open and enter. It turns out to be the church where Little Dorrit was baptized. The church official recognizes Little Dorrit and knows her life story. He gets a pillow for her head and uses a volume burial to prop the pillow up. The church official tells little Dorrit that the burial books are interesting but the most interesting fact is something else “who is coming you know, and when. That’s the interesting question.”

We are told that Little Dorrit “was soon fast asleep with her head resting on that sealed book of Fate, untroubled by its mysterious blank pages.” Dickens concludes the chapter: “this was Little Dorrit’s party. The shame, desertion, righteousness, and exposure of the great capital… This was the party from which little Dorrit went home, jaded, in the first grey mist of the rainy morning.”

Thoughts

First, let’s take a look back at the previous chapter. Dickens will often set two consecutive chapters up as a means of comparison or contrast. Chapters 13 and 14 are a case in point. In Chapter 13 we dine at Casby’s home with his daughter and his agent Mr. Pancks. The narrative in this chapter tells of a man of wealth has very little concern for the renters of his properties. Pancks, his collection agent, has no concern for any of the poor who live in Bleeding Heart Yard. Coupled with this callousness, we have Flora, Casby’s widowed daughter, who lacks all sense and understanding of the world beyond her self-inflated mind and memory. These characters all gather for a dinner in the comfort of Casby’s home. In contrast, in Chapter 14 we move to the midnight streets of London where the poor can find no homes and Little Dorrit can find sleep only by laying her head on a book that registers deaths. Do you find this method of plotting a novel effective?

In this week’s chapters we see a contrast between Arthur’s early infatuation with Flora and his friendship with Little Dorrit. In what ways does Dickens compare and contrast these two characters for his readers?

There is a marvellous allegorical painting by William Holman Hunt titled The Light of the World. It was completed in the early 1850’s. The novel Little Dorrit was written after the painting was presented to the Victorian public. Dickens and Hunt, while not friends, were certainly aware of each other. When I reflect on this chapter, I often think of Hunt’s painting. In the novel, Little Dorrit and Maggy seek a place to spend the night and knock on a door but no one answers. They spend the night wandering the streets of London before discovering the open door of a church. In the church they find shelter and Little Dorrit finally sleeps with her head upon a book that is a register of deaths. When we recall that Little Dorrit appeared at Arthur’s door at midnight and think back to the prison cell doors and the main door to the Marshalsea we begin to recognize that Dickens is highlighting the presence of doors in this novel. As we go forward in the novel let’s be aware of the presence of doors. Some doors lock people in, some doors keep people out, and some doors open to the presence of both opportunity and danger. In Hunt's painting the central allegorical feature of the painting is the fact that while Christ knocks on the door there is no handle on His side of the door. Someone must open the door from the inside to let in the light of the world. Who might that be in this novel?

Little Dorrit‘s Party

“Little Dorrit had put his hand to her lips, and would have kneeled to him, but he gently prevented her, and replaced her in her chair. “

This chapter begins with Arthur alone in his rooms. But he is not alone for long as little Dorrit appears at his door. Amy looks into Arthur’s dim room but what she sees is a place that is spacious and grandly furnished. Compared to her residence at the Marshalsea it certainly must appear to be grand. Arthur is struck with the fact that Amy is at his door at midnight, but Amy is not alone, because she has brought someone with her called Maggy. Arthur hurriedly prepares a fire to warm Amy. Amy tells Arthur that she prefers the name Little Dorrit and so we shall call her that for the remainder of the novel. :-) Maggy calls Little Dorrit “little mother“ which tells us that Little Dorrit is not only a mother to her father and her siblings but her love and kindness extends to another poor and homeless person outside the prison walls as well. Maggy is a simple creature and Dickens refers to her as a “big child.” As Little Dorrit looks at Arthur, Dickens tells us that she thought “what a good father he would be.” Hmmm. That’s interesting. Perhaps we need to tuck Little Dorrit’s private thought away in our minds.

The main reason that Little Dorrit has come is to thank Arthur for his kindness towards her brother Tip. She knows, however, that she must phrase her words in such a way that Arthur will both know what little Dorrit is saying but not actually acknowledge the same. Arthur is, of course, curious why little Dorrit and Maggy are out so late. We learn that Maggy and Little Dorrit have been to see her sister perform at a theatre. Little Dorrit has not told her father where she really was. Her father believes that Little Dorrit has been to a party. She confesses to Arthur that she has really never been to a party and says “I hope there is no harm in it. I could never have been of any use, if I had not pretended a little.” When we read these words it is evident that little Dorrit realizes her life in some ways is much like her sister’s, that she, much like her sister, is an actress, a person who acts, who pretends, who performs for the benefit of others. For those of us who, to this point in the novel dislike Mr Dorrit, there is more sorrow for Little Dorrit. She must know that her father should wonder where his daughter is until after midnight, and so Little Dorrit must invent a series of misdirections to pacify him. Whether Little Dorrit is at Mrs.Clennam’s, at a theatrical production, or within the Marshalsea with her father, her life is one of creating a series of false artifices.

Little Dorrit tells Arthur that there are three reasons she has come to him. The first is to thank Arthur for his kindness towards Tip without really identifying the fact that she knows how good Arthur is to her and her family. The second reason is to tell Arthur that she believes Mr. Flintwinch has been watching her. Little Dorrit tells Arthur that she has met him twice, both times near home, both times at night when she was returning to the Marshalsea. She reports to Arthur that Flintwinch never says anything when he passes her but rather seems to look away. These encounters make Little Dorrit anxious and she asks for Arthur’s advice as to what she should do. Arthur tells her he will speak to Affery on her behalf. The third reason little Dorrit wanted to see Arthur is to request that he not reveal any information about her actions or life outside the jail.

Thoughts

This midnight meeting between Arthur and Little Dorrit may seem strange to the reader. Why do you think Dickens included it in the story?

A new character by the name of Maggy has been introduced into the plot. She is a person who Little Dorrit apparently is also raising, or has at least befriended. What purpose could Maggy possibly serve in this novel?

This is the first time we have seen Arthur and Little Dorrit have a personal and extended conversation. It happens at midnight. Usually, in a Victorian novel, such a meeting would be inappropriate for a male and female who are not married. Were you at all concerned, upset, or curious as to why Dickens created this element of the plot?

When Little Dorrit and Maggy leave Arthur’s residence he discretely follows them until he assumes they find shelter near the Marshalsea. Such is not the case. Little Dorrit and Maggy quietly knock on a door but no one answers. This means they must find shelter on the streets of London until the morning when the Marshalsea will open its doors. The night brings challenges and encounters with other poor and homeless people. As daylight approaches, Little Dorrit and Maggy find a church’s door open and enter. It turns out to be the church where Little Dorrit was baptized. The church official recognizes Little Dorrit and knows her life story. He gets a pillow for her head and uses a volume burial to prop the pillow up. The church official tells little Dorrit that the burial books are interesting but the most interesting fact is something else “who is coming you know, and when. That’s the interesting question.”

We are told that Little Dorrit “was soon fast asleep with her head resting on that sealed book of Fate, untroubled by its mysterious blank pages.” Dickens concludes the chapter: “this was Little Dorrit’s party. The shame, desertion, righteousness, and exposure of the great capital… This was the party from which little Dorrit went home, jaded, in the first grey mist of the rainy morning.”

Thoughts

First, let’s take a look back at the previous chapter. Dickens will often set two consecutive chapters up as a means of comparison or contrast. Chapters 13 and 14 are a case in point. In Chapter 13 we dine at Casby’s home with his daughter and his agent Mr. Pancks. The narrative in this chapter tells of a man of wealth has very little concern for the renters of his properties. Pancks, his collection agent, has no concern for any of the poor who live in Bleeding Heart Yard. Coupled with this callousness, we have Flora, Casby’s widowed daughter, who lacks all sense and understanding of the world beyond her self-inflated mind and memory. These characters all gather for a dinner in the comfort of Casby’s home. In contrast, in Chapter 14 we move to the midnight streets of London where the poor can find no homes and Little Dorrit can find sleep only by laying her head on a book that registers deaths. Do you find this method of plotting a novel effective?

In this week’s chapters we see a contrast between Arthur’s early infatuation with Flora and his friendship with Little Dorrit. In what ways does Dickens compare and contrast these two characters for his readers?

There is a marvellous allegorical painting by William Holman Hunt titled The Light of the World. It was completed in the early 1850’s. The novel Little Dorrit was written after the painting was presented to the Victorian public. Dickens and Hunt, while not friends, were certainly aware of each other. When I reflect on this chapter, I often think of Hunt’s painting. In the novel, Little Dorrit and Maggy seek a place to spend the night and knock on a door but no one answers. They spend the night wandering the streets of London before discovering the open door of a church. In the church they find shelter and Little Dorrit finally sleeps with her head upon a book that is a register of deaths. When we recall that Little Dorrit appeared at Arthur’s door at midnight and think back to the prison cell doors and the main door to the Marshalsea we begin to recognize that Dickens is highlighting the presence of doors in this novel. As we go forward in the novel let’s be aware of the presence of doors. Some doors lock people in, some doors keep people out, and some doors open to the presence of both opportunity and danger. In Hunt's painting the central allegorical feature of the painting is the fact that while Christ knocks on the door there is no handle on His side of the door. Someone must open the door from the inside to let in the light of the world. Who might that be in this novel?

Peter wrote: "She confesses to Arthur that she has really never been to a party and says “I hope there is no harm in it. I could never have been of any use, if I had not pretended a little.” When we read these words it is evident that little Dorrit realizes her life in some ways is much like her sister’s, that she, much like her sister, is an actress, a person who acts, who pretends, who performs for the benefit of others.“

Peter wrote: "She confesses to Arthur that she has really never been to a party and says “I hope there is no harm in it. I could never have been of any use, if I had not pretended a little.” When we read these words it is evident that little Dorrit realizes her life in some ways is much like her sister’s, that she, much like her sister, is an actress, a person who acts, who pretends, who performs for the benefit of others.“I love this observation. The imagination is such a key theme in a lot of Dickens books, and this gives me a focus to look for it in this book about prisons.

That said, Amy should never have to do this. If you're at a point where you have to lie to the people you live with, something's very, very wrong and you don't love them as much as you think you do. Amy's lying to herself as well--especially in the part of the chapter where by some kind of tortured logic she begs Arthur not to encourage her father to beg, not because she is ashamed of him but because she is so proud of him she doesn't want people to see him behaving shamefully. That means you find his behavior shameful, Amy. Her father clearly is beyond shame: it's all hers.

I find Amy hard to take.

Peter wrote: "We again see the kindness of Arthur. To what extent do you think he is too kind, too generous, too eager to please? To what extent might Dickens be creating in Arthur a character who is too good to be believable?"

Peter wrote: "We again see the kindness of Arthur. To what extent do you think he is too kind, too generous, too eager to please? To what extent might Dickens be creating in Arthur a character who is too good to be believable?"I'm on the fence on Arthur. I really enjoyed the description of him sitting alone at the end of Chapter 13 and presented as someone with a turn of character disappointment could not spoil. Especially the idea that no matter what happens to him, he's not going to use this as an opportunity to go sour on the world. He can rise above his own unhappiness to be glad of happiness for others:

And this saved him still from the whimpering weakness and cruel selfishness of holding that because such a happiness or such a virtue had not come into his little path, or worked well for him, therefore it was not in the great scheme, but was reducible, when found in appearance, to the basest elements. A disappointed mind he had, but a mind too firm and healthy for such unwholesome air. Leaving himself in the dark, it could rise into the light, seeing it shine on others and hailing it.

I wish I were more like that myself: it's too easy to envy what I don't have that others get, rather than to appreciate it. I don't know if Arthur's character is realistic, but it's admirable--and I don't mind having a model held up that's a bit unachievable. It doesn't hurt to know what you wish things or people or even yourself could be like, so that at least you can aim a little higher and maybe make it part of the way.

But--I also find Arthur a bit of a patronizing whiner. I'm disappointed in how thoroughly he turns on Flora (though that is funny, too), I'm suspicious of the ego-investment in his sudden and intrusive interest in Amy and her family, and I still don't get why a man of 40 years and independent income is blaming his mother for his life not turning out the way he likes.

Non-rhetorical question: does anyone think anything good will come of Tip being turned loose on the world again?

Non-rhetorical question: does anyone think anything good will come of Tip being turned loose on the world again?

Julie wrote: "Peter wrote: "She confesses to Arthur that she has really never been to a party and says “I hope there is no harm in it. I could never have been of any use, if I had not pretended a little.” When w..."

Hi Julie

I struggle with my feelings towards Little Dorrit. Her father and her siblings are either totally reliant on her or on the fringes of reliance. In many ways, I think Little Dorrit is an enabler. Her father has perfected the role of being needy, so much so that he has made an art form of his position within the Marshalsea and the mind of Amy.

As for Tip, I think he has fallen off the wagon once and seems to have little resilience for the challenges of life. His sister seems to have made some headway in life. While being an actress was not seen as being the most noble of professions in the 19C there has been to date no indication of her falling into disrepute.

Hi Julie

I struggle with my feelings towards Little Dorrit. Her father and her siblings are either totally reliant on her or on the fringes of reliance. In many ways, I think Little Dorrit is an enabler. Her father has perfected the role of being needy, so much so that he has made an art form of his position within the Marshalsea and the mind of Amy.

As for Tip, I think he has fallen off the wagon once and seems to have little resilience for the challenges of life. His sister seems to have made some headway in life. While being an actress was not seen as being the most noble of professions in the 19C there has been to date no indication of her falling into disrepute.

Peter wrote: "His sister seems to have made some headway in life. While being an actress was not seen as being the most noble of professions in the 19C there has been to date no indication of her falling into disrepute."

Peter wrote: "His sister seems to have made some headway in life. While being an actress was not seen as being the most noble of professions in the 19C there has been to date no indication of her falling into disrepute."Yes, I am very curious about her sister and would like to hear more of her.

Julie wrote: "Non-rhetorical question: does anyone think anything good will come of Tip being turned loose on the world again?"

Julie wrote: "Non-rhetorical question: does anyone think anything good will come of Tip being turned loose on the world again?"Of course not. peace, janz

This week has been a great lesson in the difference between reading a book and listening to an audio version. When I first read LD, I had an immediate connection with Flora, and understood her in a way I think most readers miss. This time, I happened to listen to that chapter, and it's amazing how differently she came across to me when interpreted by someone else. I think it's a good lesson in reading things off the page for ourselves - at least the first time, as Julie said.

This week has been a great lesson in the difference between reading a book and listening to an audio version. When I first read LD, I had an immediate connection with Flora, and understood her in a way I think most readers miss. This time, I happened to listen to that chapter, and it's amazing how differently she came across to me when interpreted by someone else. I think it's a good lesson in reading things off the page for ourselves - at least the first time, as Julie said. Julie, I also agree with your thoughts on shame. Haven't we all had circumstances in which we've been ashamed of a family member's behaviour, and felt as if we should apologize and make excuses? All in an effort to make ourselves look better in comparison. What are we - and Amy - to do? She loves these reprobates, so she doesn't want to cut them out of her life, but they're definitely holding her down. I don't think it would hurt to give them a dose of truth instead of all the pretense. But I wonder - would it help?

Chapter 13 was wonderful, but I do wish Dickens had split it up. Thank you for doing it, Peter. I wonder why Dickens didn't end it when Arthur and Panks departed Casby's home.

Chapter 13 was wonderful, but I do wish Dickens had split it up. Thank you for doing it, Peter. I wonder why Dickens didn't end it when Arthur and Panks departed Casby's home. I couldn't help but think of "The Dinner Party" episode of The Office as I read this. Both of these dinners were about as uncomfortable and awkward as an evening can be. Which made them a delight for those of us who were flies on the wall. Mr. F's Aunt is a hoot, and I'm sure any time she comes into a scene, there will be a treat in store for the reader.

I looked up Hunt's painting, but didn't notice the lack of a handle until reading your comment further. That little detail makes all the difference. I'll keep that painting and your comments about it in mind as we go forward.

Arthur and Amy are both fixers. Arthur, for whatever reason, has made a project of the Dorrits. Do they want to be "fixed"? Amy seems grateful; I wonder if the others will. Amy, too, is trying to fix things for her family and Maggy. It will be interesting to watch how A & A go about this, and how it's received. As their individual projects coincide, will they work together, or have a difference of opinion about how to go about things? Amy's doing this for family, whereas Arthur's a stranger and a newcomer. I think I'd be a bit resentful of someone presumptuously swooping in and interfering, despite their best intentions. Is Arthur just another Mrs. Pardiggle (Bleak House)? This may be one of the meanings of "Bleeding Heart Yard" that you were referring to, Peter.

PS re: Panks....

PS re: Panks....He's certainly not painted as a likeable or trustworthy person, but I can't help but notice his interaction with Mr. F's Aunt. I have great admiration for people who treat the elderly, infirmed, and demented with dignity. He's not at all condescending, but he's comfortable with her, and treats her with dignity where she is, if you know what I mean. Something to keep in mind.

Mary Lou wrote: "PS re: Panks....

He's certainly not painted as a likeable or trustworthy person, but I can't help but notice his interaction with Mr. F's Aunt. I have great admiration for people who treat the eld..."

Mary Lou

I completely missed this angle of interpretation. Thank you.

He's certainly not painted as a likeable or trustworthy person, but I can't help but notice his interaction with Mr. F's Aunt. I have great admiration for people who treat the eld..."

Mary Lou

I completely missed this angle of interpretation. Thank you.

Mary Lou wrote: "Chapter 13 was wonderful, but I do wish Dickens had split it up. Thank you for doing it, Peter. I wonder why Dickens didn't end it when Arthur and Panks departed Casby's home.

I couldn't help but..."

Mary Lou

I agree that both Arthur and Amy (A & A … love it!) are fixers. How they choose to go about fixing what they perceive as wrong, and whether their fixing with lead to strife or harmony among the other characters remains to be seen. At present they are working from opposite financial positions. One question that may arise is to what extent money can solve a problem. We shall see.

Indeed, perhaps money could be exactly what is not needed. If we have a place called Bleeding Heart Lane and an institution called The Circumlocution Office then what name could be assigned to the workings of the human heart?

I’m glad you enjoyed Holman Hunt’s picture. There is much allegory and symbolism in it. Hunt painted a companion picture which he titled “The Awakening Conscience.” It too is rich in symbolism. This painting has often been connected to the novel David Copperfield. I had the good fortune to hear an analysis that linked the painting to the relationship between Steerforth and Little Em’ly and how it represents the moment of Little Em’ly’s awakening. Fascinating.

I couldn't help but..."

Mary Lou

I agree that both Arthur and Amy (A & A … love it!) are fixers. How they choose to go about fixing what they perceive as wrong, and whether their fixing with lead to strife or harmony among the other characters remains to be seen. At present they are working from opposite financial positions. One question that may arise is to what extent money can solve a problem. We shall see.

Indeed, perhaps money could be exactly what is not needed. If we have a place called Bleeding Heart Lane and an institution called The Circumlocution Office then what name could be assigned to the workings of the human heart?

I’m glad you enjoyed Holman Hunt’s picture. There is much allegory and symbolism in it. Hunt painted a companion picture which he titled “The Awakening Conscience.” It too is rich in symbolism. This painting has often been connected to the novel David Copperfield. I had the good fortune to hear an analysis that linked the painting to the relationship between Steerforth and Little Em’ly and how it represents the moment of Little Em’ly’s awakening. Fascinating.

Ah! I've seen "The Awakening Conscience" before! No doubt you shared it with us during our reading of Copperfield.

Ah! I've seen "The Awakening Conscience" before! No doubt you shared it with us during our reading of Copperfield.

Mary Lou wrote: "Mr. F's Aunt is a hoot, and I'm sure any time she comes into a scene, there will be a treat in store for the reader.."

Mary Lou wrote: "Mr. F's Aunt is a hoot, and I'm sure any time she comes into a scene, there will be a treat in store for the reader.."Yes! She's great. And I love it that she has no other name.

No, I don't really think telling them the truth would help Amy's family. I guess it's more her lying to herself that I'm concerned about.

re: Amy being an enabler. She is blind to what she is doing. I had family members like this who interjected themselves into everything and everywhere because they "knew the right thing to do." That is how they get their praise. "Just trying to help out." God save us from them. peace, janz

re: Amy being an enabler. She is blind to what she is doing. I had family members like this who interjected themselves into everything and everywhere because they "knew the right thing to do." That is how they get their praise. "Just trying to help out." God save us from them. peace, janz

I think Arthur is also an enabler -- he helps people and forgoes the praise - helps them in secret sometimes. But his little heart grows larger and larger when he "does something good for someone." And then he refuses their outward praise - see how he treats Amy when she tries to thank him. "Aw, it was nothing." Enablers keep the world going but.... at what cost to themselves and the people they help.

I think Arthur is also an enabler -- he helps people and forgoes the praise - helps them in secret sometimes. But his little heart grows larger and larger when he "does something good for someone." And then he refuses their outward praise - see how he treats Amy when she tries to thank him. "Aw, it was nothing." Enablers keep the world going but.... at what cost to themselves and the people they help. peace, janz

I had much the same thoughts about Little Dorritt. She is ashamed of her father but can not admit it to herself for personal reason or to anyone else for societal reasons or some misplaced sense of filial piety.

I had much the same thoughts about Little Dorritt. She is ashamed of her father but can not admit it to herself for personal reason or to anyone else for societal reasons or some misplaced sense of filial piety. She is an enabler, but I do not think she has had a chance to learn to be anything else. This applies to Arthur as well.

I also got the sense that Little Dorritt has a bit of a martyr complex. I can't find a particular quote, but her interactions with Maggy and the lady of the night that approached them...left an odd taste in my figurative mouth.

Original version

Manchester version

Later St. Paul's version

The Light of the World

Holman Hunt

The Light of the World (1851–1853) is an allegorical painting by the English Pre-Raphaelite artist William Holman Hunt (1827–1910) representing the figure of Jesus preparing to knock on an overgrown and long-unopened door, illustrating Revelation 3:20: "Behold, I stand at the door and knock; if any man hear My voice, and open the door, I will come in to him, and will sup with him, and he with Me". According to Hunt: "I painted the picture with what I thought, unworthy though I was, to be divine command, and not simply a good subject." The door in the painting has no handle, and can therefore be opened only from the inside, representing "the obstinately shut mind". The painting was considered by many to be the most important and culturally influential rendering of Christ of its time.

The original is variously said to have been painted at night in a makeshift hut at Worcester Park Farm in Surrey, and in the garden of the Oxford University Press, while it is suggested that Hunt found the dawn light he needed outside Bethlehem on one of his visits to the Holy Land. In oil on canvas, it was begun around 1849 or 1850 and completed in 1853. It was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1854 and is now in the side chapel at Keble College, Oxford. The painting was donated to the college by Martha Combe, the widow of Thomas Combe, Printer to the University of Oxford, Tractarian, and a patron of the Pre-Raphaelites, in the year following his death in 1872, on the understanding that it would hang in the chapel (constructed 1873–1876), but the building's architect William Butterfield was opposed to that and made no provision in his design. When the college library opened in 1878 it was placed there, and was moved to its present position only after the construction of the side chapel to accommodate it, in 1892–1895, by another architect, J. T. Micklethwaite.

A second, smaller version of the work, painted by Hunt between 1851 and 1856, is on display at Manchester City Art Gallery, England, which purchased it in 1912. There are small differences between that and the first version, such as the angle of the gaze, and the drape of the corner of the red cloak.

The fact that, at the time, Keble College charged a fee to view the picture, persuaded Hunt to paint a larger, life-sized, version toward the end of his life. He began it in about 1900 and finished in 1904. Shipowner and social reformer, Charles Booth, purchased the work and it was hung in St Paul's Cathedral, London. It was dedicated there in 1908, following a 1905–1907 world tour, during which the picture drew large crowds. It was claimed that four-fifths of Australia's population viewed it. Due to Hunt's increasing infirmity and glaucoma, he was assisted in the completion of this version by English painter Edward Robert Hughes (who also assisted with Hunt's version of The Lady of Shalott). The third version diverges more from the original than the second one.

She tenderly hushed the baby in her arms.

Chapter 12, Book 1

James Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

And stooping down to pinch the cheek of another young child who was sitting on the floor, staring at him, asked Mrs. Plornish how old that fine boy was?

Four year just turned, sir," said Mrs. Plornish. "He is a fine little fellow, ain't he, sir? But this one is rather sickly." She tenderly hushed the baby in her arms, as she said it. 'You wouldn't mind my asking if it happened to be a job as you was come about, sir, would you?" asked Mrs. Plornish wistfully.

She asked it so anxiously, that if he had been in possession of any kind of tenement, he would have had it plastered a foot deep rather than answer No. But he was obliged to answer No; and he saw a shade of disappointment on her face, as she checked a sigh, and looked at the low fire. Then he saw, also, that Mrs. Plornish was a young woman, made somewhat slatternly in herself and her belongings by poverty; and so dragged at by poverty and the children together, that their united forces had already dragged her face into wrinkles. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 12.

Commentary:

The following caption is considerably longer in the Harper and Bros. (New York) edition, and makes the error of situating the illustration in Chapter 11:

And stooping down to pinch the cheek of another young child who was sitting on the floor, staring at him, asked Mrs. Plornish how old that fine boy was? "Four year, just turned, sir," said Mrs. Plornish. "He's a fine little fellow, a'int he, sir, but this one is rather sickly." She tenderly hushed the baby in her arms as she said it.

The Mahoney illustration departs from Phiz's original illustrations in that Phiz did not provide an illustration for the chapter in which Arthur visits the rooms of the plasterer, Plornish, in Bleeding Heart Yard, a scene that acquaints the reader with the class below Dickens's — the working poor. Rather, Phiz had illustrated Chapter 9 with Little Mother, showing Clennam's developing interest in Amy Dorrit, and Chapter 11 with Making Off, following the Rigaud-Cavaletto plot, both in the third monthly part (February 1856).

The meeting of the Plornishes and Arthur Clennam is the result of his trying to determine precisely how Little Dorrit came to work for his mother. Apparently they assisted her in disseminating hand-written advertisements which resulted in Mrs. Clennam's hiring Amy as a seamstress. Moreover, here in Bleeding Heart Yard, a ghetto in the midst of a mixed housing and industrial neighborhood, Clennam confronts the plight of the working, urban poor. As an independent businessman, Plornish should be regarded a member of the middle class, like Joe Gargery in Great Expectations (1861), but, since he is only infrequently employed, he easily falls into debt, and thus for a brief time had become an inmate of the Marshalsea, which is precisely where he and his wife would have met Little Dorrit and her gentlemanly father, whom the Plornishes regard as belonging to a class decidedly above their own. Consequently, at least as far as the Plornishes know, Fanny and Amy have kept their employments secret from Mr. Dorrit.

While he awaits the arrival of her husband, genuinely interested in the Plornish children apparently, the thoroughly bourgeois Arthur Clennam (as signified by his tailcoat, cane, and top-hat) tries to engage the young mother in conversation about her children. Although he focuses on the stout four-year-old boy before him in a linen smock, Mrs. Plornish is absorbed by the sickly condition of her infant, whom she is hoping that Clennam will assist by giving her husband a contract. The illustrator conveys the look of apprehension mixed with disappointment on her face, but does not convey her wistfulness. Washing hangs on the line behind them, and a slight fire illuminates the fireplace (right).

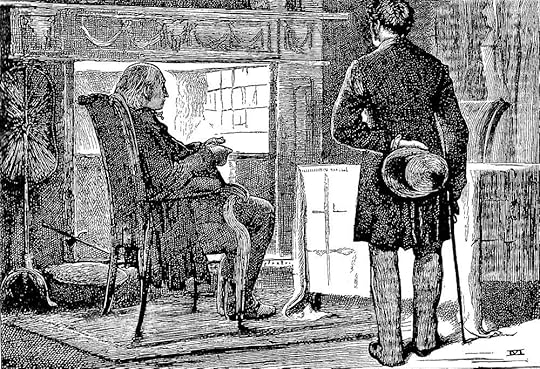

Mr. F's Aunt is conducted into retirement

Chapter 13

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

There was a fourth and most original figure in the Patriarchal tent, who also appeared before dinner. This was an amazing littl old woman, with a face like a staring wooden doll too cheap for expression, and a stiff yellow wig perched unevenly on the top of her head, as if the child who owned the doll had driven a tack through it anywhere, so that it only got fastened on. Another remarkable thing in this little old woman was, that the same child seemed to have damaged her face in two or three places with some blunt instrument in the nature of a spoon; her countenance, and particularly the tip of her nose, presenting the phenomena of several dints, generally answering to the bowl of that article. A further remarkable thing in this little old woman was, that she had no name but Mr F.'s Aunt.

. . . . Flora had just said, "Mr. Clennam, will you give me a glass of port for Mr. F.'s Aunt?"

"The Monument near London Bridge," that lady instantly proclaimed, "was put up arter the Great Fire of London; and the Great Fire of London was not the fire in which your uncle George's workshops was burned down."

Mr. Pancks, with his former courage, said, "Indeed, ma'am? All right!" But appearing to be incensed by imaginary contradiction, or other ill-usage, Mr. F.'s Aunt, instead of relapsing into silence, made the following additional proclamation:

"I hate a fool."

She imparted to this sentiment, in itself almost Solomonic, so extremely injurious and personal a character by levelling it straight at the visitor's head, that it became necessary to lead Mr. F.'s Aunt from the room. This was quietly done by Flora; Mr. F.'s Aunt offering no resistance, but inquiring on her way out, "What he come there for, then?" with implacable animosity.

When Flora returned, she explained that her legacy was a clever old lady, but was sometimes a little singular, and 'took dislikes' — peculiarities of which Flora seemed to be proud rather than otherwise.

Commentary:

In the original serial installment, Phiz demonstrates the hero's realization that renewing his former relationship with Flora Finching (nee Casby) is hardly possible. Above the benign figure of age, the patriarchal and Quaker-like, white, silken haired Mr. Casby Phiz has situated the boyhood portrait of the capitalist, a reminder to Arthur Clennam and the reader of both the resemblance and the disjuncture between a youthful figure and his or her mature equivalent, precisely the kind of double image that Clennam has been bearing in mind with respect to Flora Casby/Flora Finching. The disturbing elements in this journey down memory lane include Clennam's seeing both Flora and her father for what they really are and the col tempo reminder of the withering and decaying effects of age as evident in Mr. F's Aunt.

Clennam is introduced to "Mr. F.'s Aunt."

Chapter 13, Book 1

Harry Furniss

Commentary:

Fin-de-siécle illustrator Harry Furniss's interpretation of the awkward dinner at the Patriarchal mansion. The lithograph occurs facing page 160, but the passage illustrated occurs two pages later, setting up expectations in the reader about the nature of Arthur's visit to the Casby mansion. The accompanying caption identifies the precise lines realized (with some condensing of the original text):

A fourth figure in the Patriarchal tent, whom Flora introduced as "Mr. F's Aunt," was an amazing little old woman, with a face like a staring wooden doll, too cheap for expression, and a stiff yellow wig perched unevenly on the top of her head.

The Furniss illustration captures the character comedy of the situation, and Arthur Clennam's discomfiture, which, in fact, occurs after the peculiar Aunt speaks. Furniss reinterprets the original serial illustration of March 1856, Mr. F.'s Aunt is conducted into Retirement.

In the original serial installment, Phiz demonstrates the hero's realization that renewing his former relationship with Flora Finching (nee Casby) is hardly possible. In Furniss's redrafting, the dinner-guest, Arthur Clennam, is the focal point for this scene full of caricature, from the presiding, Quaker-like "Patriarch" to the calculating businessman, Casby (right). Clennam rises abruptly from his chair, not quite sure what to make of Mr. F's Aunt, or of the sweetheart who seems to disregard her aunt's rude and erratic behaviour, which Furniss again emphasizes in, Mr. F.'s Aunt.

The servant maid had ticked the two words, "Mr. Clennam," so softly, that she had not been heard

Chapter 13, Book 1

James Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

When his knock at the bright brass knocker of obsolete shape brought a woman-servant to the door, those faded scents in truth saluted him like wintry breath that had a faint remembrance in it of the bygone spring. He stepped into the sober, silent, air-tight houseone might have fancied it to have been stifled by Mutes in the Eastern manner— and the door, closing again, seemed to shut outsound and motion. The furniture was formal, grave, and quaker-like, but well-kept; and had as prepossessing an aspect as anything, from a human creature to a wooden stool, that is meant for much use and is preserved for little, can ever wear. There was a grave clock, ticking somewhere up the staircase; and there was a songless bird in the same direction, pecking at his cage, as if he were ticking too. The parlour-fire ticked in the grate. There was only one person on the parlour-hearth, and the loud watch in his pocket ticked audibly.

The servant-maid had ticked the two words "Mr. Clennam" so softly that she had not been heard; and he consequently stood, within thedoor she had closed, unnoticed. The figure of a man advanced in life, whose smooth grey eyebrows seemed to move to the ticking as the fire-light flickered on them, sat in an arm-chair, with his list shoes on the rug, and his thumbs slowly revolving over one another. This was old Christopher Casby — recognisable at a glance — as unchanged in twenty years and upward as his own solid furniture — as little touched by the influence of the varying seasons as the old rose-leaves and old lavender in his porcelain jars. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 13.

Commentary:

Mr. Christopher Casby, the father of Arthur Clennam's former sweetheart, Flora (now, the widow Mrs. Finching), has not changed one bit during Arthur's twenty-year absence in China. Arthur's quest for information about the Dorrits has taken him to Bleeding Heart Yard, one of Mr. Casby's rental properties — and part of rent-collector Pancks's route on rent-day. Clennam's staying to dinner affords him the opportunity to study his adolescent sweetheart, now twenty years older but still flirtatious, loquacious, and vacuous — and now more than a little overweight. Shown in the original 1857 steel-engraving, the widow's "legacy," the demented, elderly aunt of her deceased husband, guards Flora jealousy, scaring away prospective suitors such as Arthur Clennam with her erratic behaviour, non-sequiturs, and insults. Rather than merely repeat or reinterpret the Phiz illustration for this chapter, Mahoney selects the earlier interview between Casby and Clennam to intensify the melancholy mood as the protagonist re-visits a past that he cannot recapture and as youthful feeling that he cannot reconstitute.

Flora and Mr. F's Aunt

Chapter 13, Book 1

Sol Eytinge Jr.

Commentary:

The fourth illustration, unlike the others before it, does not introduce its subjects in a characteristic setting (such as Rigaud and Cavaletto's cell) or with significant appurtenances (such as Mrs. Clennam's symbols of inflexibility and control, her wheel-chair and bell-pull). Rather, Eytinge has chosen to focus on the faces and the dresses of the women alone to suggest their relationship and characters, but places them in such close proximity to graph the col tempo theme: what Mr. F's aunt is Flora will become. But, again, as the other plates in the series thus far have realised a specific passage in the narrative, here in Chapter 13, "Patriarchal," Eytinge captures the moment when the young widow Flora Finching leads Mr. F.'s Aunt from the dining room: "it became necessary to lead Mr. F.'s Aunt from the room. This was quietly done by Flora; Mr. F.'s Aunt offering no resistance, but inquiring on her way out, 'What he come there for, then?' with implacable animosity". In describing the appearance of Arthur Clennam's former sweetheart and of her sharp contrast, Mr. F.'s "legacy," the vacuous aunt, Eytinge has actually conflated two separate descriptive passages in his illustration, beginning with the flirtatious Flora herself:

Flora, always tall, had grown to be very broad too, and short of breath; but that was not much. Flora, whom he had left a lily, had become a peony; but that was not much. Flora, who had seemed enchanting in all she said and thought, was diffuse and silly. That was much. Flora, who had been spoiled and artless long ago, was determined to be spoiled and artless now. That was a fatal blow.

This is Flora!

"I am sure," giggled Flora, tossing her head with a caricature of her girlish manner, such as a mummer might have presented at her own funeral, if she had lived and died in classical antiquity, "I am ashamed to see Mr. Clennam, I am a mere fright, I know he'll find me fearfully changed, I am actually an old woman, it's shocking to be found out, it's really shocking!" [Ch. 13, "Patriarchal"]

Whereas Eytinge interprets the aunt as senile and one-dimensional, he suggests through the fullness of Flora's rounded face and figure that she is, despite her superficiality, attractive and kind-hearted. He contrasts these positive aspects of Flora's character with the aged thinness (so apt for one whose remarks are always totally irrelevant to the topic in hand) of Mr. F's Aunt, whom Eytinge has realized in every visual particular from Dickens's narration of Arthur Clennam's dinner with Mr. Casby and his childhood sweetheart, who has not merely grown up but out as the recently widowed Mrs. Flinching:

There was a fourth and most original figure in the Patriarchal tent, who also appeared before dinner. This was an amazing little old woman, with a face like a staring wooden doll too cheap for expression, and a stiff yellow wig perched unevenly on the top of her head, as if the child who owned the doll had driven a tack through it anywhere, so that it only got fastened on. Another remarkable thing in this little old woman was, that the same child seemed to have damaged her face in two or three places with some blunt instrument in the nature of a spoon; her countenance, and particularly the tip of her nose, presenting the phenomena of several dints, generally answering to the bowl of that article. A further remarkable thing in this little old woman was, that she had no name but Mr. F.'s Aunt.

She broke upon the visitor's view under the following circumstances: Flora said when the first dish was being put on the table, perhaps Mr Clennam might not have heard that Mr F. had left her a legacy? Clennam in return implied his hope that Mr. F. had endowed the wife whom he adored, with the greater part of his worldly substance, if not with all. Flora said, oh yes, she didn't mean that, Mr. F. had made a beautiful will, but he had left her as a separate legacy, his Aunt. She then went out of the room to fetch the legacy, and, on her return, rather triumphantly presented "Mr. F.'s Aunt."

The major characteristics discoverable by the stranger in Mr. F.'s Aunt, were extreme severity and grim taciturnity; sometimes interrupted by a propensity to offer remarks in a deep warning voice, which, being totally uncalled for by anything said by anybody, and traceable to no association of ideas, confounded and terrified the Mind. Mr. F.'s Aunt may have thrown in these observations on some system of her own, and it may have been ingenious, or even subtle: but the key to it was wanted.

There is something of the somnambulist about Mr. F.'s Aunt as Flora gently takes the elderly lady's extended arm to help her keep her balance, or simply prop her up physically as she does in her conversation. The quality that Eytinge does not communicate is her defiance of Arthur Clennam throughout the meal, perhaps born of her conviction that Arthur has returned from China to claim his bride and deprive Mr. F.'s Aunt of her sole prop and support in life. All of this the reader will have surmised before encountering Eytinge's illustration, when Flora leads Mr. F.'s Aunt from the room.

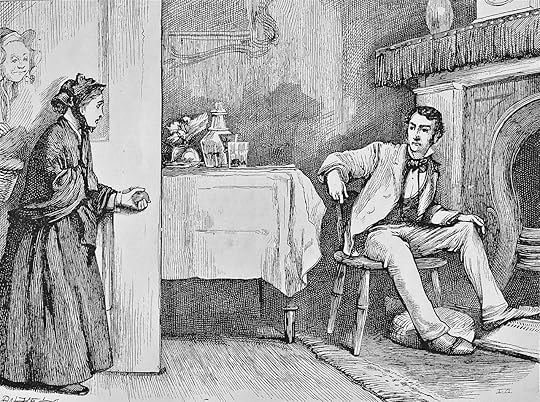

Little Dorrit

Chapter 13, Book 1

James Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

Therefore, he sat before his dying fire, sorrowful to think upon the way by which he had come to that night, yet not strewing poison on the way by which other men had come to it. That he should have missed so much, and at his time of life should look so far about him for any staff to bear him company upon his downward journey and cheer it, was a just regret. He looked at the fire from which the blaze departed, from which the afterglow subsided, in which the ashes turned grey, from which they dropped to dust, and thought, "How soon I too shall pass through such changes, and be gone!" To review his life was like descending a green tree in fruit and flower, and seeing all the branches wither and drop off, one by one, as he came down towards them. "From the unhappy suppression of my youngest days, through the rigid and unloving home that followed them, through my departure, my long exile, my return, my mother's welcome, my intercourse with her since, down to the afternoon of this day with poor Flora," said Arthur Clennam, "what have I found!" His door was softly opened, and these spoken words startled him, and came as if they were an answer: "Little Dorrit."

[Chapter 14: "Little Dorrit's Party"] Arthur Clennam rose hastily, and saw her standing at the door. This history must sometimes see with Little Dorrit’s eyes, and shall begin that course by seeing him. Little Dorrit looked into a dim room, which seemed a spacious one to her, and grandly furnished. Courtly ideas of Covent Garden, as a place with famous coffee-houses, where gentlemen wearing gold-laced coats and swords had quarrelled and fought duels; costly ideas of Covent Garden, as a place where there were flowers in winter at guineas a-piece, pine-apples at guineas a pound, and peas at guineas a pint; picturesque ideas of Covent Garden, as a place where there was a mighty theatre, showing wonderful and beautiful sights to richly-dressed ladies and gentlemen, and which was for ever far beyond the reach of poor Fanny or poor uncle; desolate ideas of Covent Garden, as having all those arches in it, where the miserable children in rags among whom she had just now passed, like young rats, slunk and hid, fed on offal, huddled together for warmth, and were hunted about (look to the rats young and old, all ye Barnacles, for before God they are eating away our foundations, and will bring the roofs on our heads!); teeming ideas of Covent Garden, as a place of past and present mystery, romance, abundance, want, beauty, ugliness, fair country gardens, and foul street gutters; all confused together, — made the room dimmer than it was in Little Dorrit's eyes, as they timidly saw it from the door. — Book the First, "Poverty," end of Chapter 13, and beginning of Chapter 14.

Commentary:

In the New York edition, the caption for this scene at the end of chapter 13 is: His door was softly opened, and these spoken words startled him, and came as if they were an answer, "Little Dorrit".

The large-scale, full-page frontispiece enforces a proleptic reading as the passage realized is some eighty-four pages away, when the narrative focus shifts from Arthur Clennam's reverie about his own sad childhood and melancholy upbringing to Little Dorrit's perspective.

After a night at the theatre in company with Maggy, Little Dorrit visits Arthur Clennam in his rooms overlooking Covent Garden to thank him for arranging her brother Tip's release from the Marshalsea. As a consequence of the extra activity after an evening at the working-class theatre where her uncle and sister work, Maggy and Little Dorrit arrive at Maggy's lodging to late to be admitted — everybody in the house is apparently sound asleep, and nobody responds when Amy knocks. This eventuality Little Dorrit had not foreseen, even though she had expected to be locked out of the Marshalsea. Now she and Maggy must make the best of a bad situation and spend the night out on the street, waiting out the five hours before the prison gates open at daybreak. After crossing London Bridge and returning, they notice lights on in the church nearby. The kindly sexton, recalling Amy as appearing in the church's birth registry, offers to let her sleep the few remaining hours of the night in the vestry.

Little Dorrit's Party

Chapter 14

Phiz

Text Illustrated:

No day yet in the sky, but there was day in the resounding stones of the streets; in the waggons, carts, and coaches; in the workers going to various occupations; in the opening of early shops; in the traffic at markets; in the stir of the riverside. There was coming day in the flaring lights, with a feebler colour in them than they would have had at another time; coming day in the increased sharpness of the air, and the ghastly dying of the night.

They went back again to the gate, intending to wait there now until it should be opened; but the air was so raw and cold that Little Dorrit, leading Maggy about in her sleep, kept in motion. Going round by the Church, she saw lights there, and the door open; and went up the steps and looked in. . . .

This was Little Dorrit's party. The shame, desertion, wretchedness, and exposure of the great capital; the wet, the cold, the slow hours, and the swift clouds of the dismal night. This was the party from which Little Dorrit went home, jaded, in the first grey mist of a rainy morning. — Book the First, "Poverty," Chapter 14.

Commentary:

"Little Dorrit's Party" is really Phiz's only chance (apart from the cover and the final pair of etchings) to make direct social and thematic comment, but another dark plate, "Visitors at the Works" (Bk 1, ch. 23), imparts a certain Kafkaesque quality to the novel.

The picture offers an interesting fusion of the architectural and the pathetic, with Maggy and Little Dorrit locked out of a dilapidated edifice which is also a decaying social institution, the debtors' prison. Phiz subordinates the female characters, the focal point of the nightmarish adventure like something out of French illustrator Gustav Doré's night scenes of Victorian London to focus on two buildings from earlier eras: the crumbling and ruinous eighteenth-century prison with its tattered flag in the foreground and the Gothic style Church of St. George the Martyr in the background. Although the debtors' prison as a social institution dates from the middle ages, it was at its zenith in the eighteenth century, when over half of all inmates of English prisons were in fact incarcerated in such places. Dickens's own father, John, a clerk in the Naval Pay Office, was sent to the Marshalsea on 20 February 1824 for an unpaid baker's bill. That year when the future novelist was just twelve was seared into the boy's mind by his own servitude at Warren's Blacking Factory at Hungerford Stairs on the Thames. Dickens that year worked most of the week without seeing his family, lodging not in the Marshalsea like Amy, but in Lant Street.

The title of the fourteenth chapter in Book the First, like that of the complementary illustration, is situationally ironic as Amy's spending the first night of her life outside the Marshalsea, sleeping in the streets and wandering a deserted London Bridge with Maggy, is anything but a party. The night proves Kafkaesque as strange street-people accost the pair, and Amy sees the night side of London, defamiliarizing her notion of the metropolis as a safe and civilized place. Likewise, in his next novel — the last that Phiz would illustrate for Charles Dickens (as much a "Child of the Marshalsea" as Amy Dorrit) — Lucie Manette discovers the night side of another European metropolis in which the normal polity of day and of reasonable civic organization has utterly broken down. At least in the nightside of Little Dorrit compassion and fairness form part of the code of the streets and sheer social Darwinism does not reign.

Little Dorrit and Maggy find shelter in the vestry

Chapter 14, Book 1

Harry Furniss

Text Illustrated:

"We have often seen each other," said Little Dorrit, recognising the sexton, or the beadle, or the verger, or whatever he was, "when I have been at church here."

"More than that, we've got your birth in our Register, you know; you're one of our curiosities."

"Indeed!" said Little Dorrit.

"To be sure. As the child of the — by-the-bye, how did you get out so early?"

"We were shut out last night, and are waiting to get in."

"You don't mean it? And there's another hour good yet! Come into the vestry. You’ll find a fire in the vestry, on account of the painters. I’m waiting for the painters, or I shouldn't be here, you may depend upon it. One of our curiosities mustn't be cold when we have it in our power to warm her up comfortable. Come along."

He was a very good old fellow, in his familiar way; and having stirred the vestry fire, he looked round the shelves of registers for a particular volume. "Here you are, you see," he said, taking it down and turning the leaves. "Here you'll find yourself, as large as life. Amy, daughter of William and Fanny Dorrit. Born, Marshalsea Prison, Parish of St George. And we tell people that you have lived there, without so much as a day's or a night's absence, ever since. Is it true?"

"Quite true, till last night."

"Lord!" But his surveying her with an admiring gaze suggested Something else to him, to wit: "I am sorry to see, though, that you are faint and tired. Stay a bit. I’ll get some cushions out of the church, and you and your friend shall lie down before the fire. Don't be afraid of not going in to join your father when the gate opens. I'll call you."

He brought in the cushions [for Little Dorrit and her friend to rest on.]

Commentary:

After a night at the theatre in company with Maggy, Little Dorrit visits Arthur Clennam in his rooms overlooking Covent Garden to thank him for arranging her brother Tip's release from the Marshalsea. In consequence, the pair find themselves too late to be admitted to Maggy's lodging house, and must spend the night in the streets.

Fin-de-siécle illustrator Harry Furniss's interpretation of Amy's experience of being locked out of the Marshalsea and having to spend the night on the street after her plan for staying in Maggy's lodgings falls through. The lithograph from the Charles Dickens Library Edition, 1910, reinterprets the original serial illustration, Little Dorrit's Party in Dickens's Little Dorrit. The pen-and-ink sketch occurs facing page 193 in Chapter 15, but the passage illustrated occurs nine pages earlier, forcing the reader to return to the previous chapter and re-read its fortunate conclusion, in which the kindly sexton of St. George's admits Amy and Maggy to the vestry and fetches them cushions from the church nave.

The artist, aware that readers are likely to familiar with Phiz's interpretation of the pair being shut out of the Marshalsea — Little Dorrit's Party, does not attempt to replicate Phiz's architectural handling of the exterior night scene. Rather, Furniss reduces the interior scene which follows the night's adventures to the bare essentials: the old sexton, who is offering Maggy and Little Dorrit pillows. Furniss focuses on Amy by depicting her examining the register of births while he has merely sketched in the interior Gothic architectural elements of arch and pilaster. While Maggy in her gigantic bonnet seems somewhat stupefied, staring blankly ahead of her, the alert Amy turns away to examine the register.

The gate was so familiar, and so like a companion, that they put down Maggy's basket in a corner to serve for a seat.

Chapter 14, Book 1

James Mahoney

Text Illustrated:

It was a chill dark night, with a damp wind blowing, when they came out into the leading street again, and heard the clocks strike half-past one. "In only five hours and a half," said Little Dorrit, "we shall be able to go home." To speak of home, and to go and look at it, it being so near, was a natural sequence. They went to the closed gate, and peeped through into the court-yard. "I hope he is sound asleep," said Little Dorrit, kissing one of the bars, "and does not miss me."