Dickensians! discussion

This topic is about

Little Dorrit

Little Dorrit - Group Read 2

>

Little Dorrit II: Chapters 23 - 34

message 151:

by

Mark

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Nov 24, 2020 01:55PM

I found out that "Bleeding Heart" changed from an idea of Christian compassion to an image of excessive liberalism in the 1930s when a US columnist used it pejoratively.

I found out that "Bleeding Heart" changed from an idea of Christian compassion to an image of excessive liberalism in the 1930s when a US columnist used it pejoratively.

reply

|

flag

Elizabeth - yes, right, even the minor characters in Dickens are well drawn.

Elizabeth - yes, right, even the minor characters in Dickens are well drawn. I get a chuckle whenever the perpetually irritated Mr. F.'s aunt is present to scowl and shout non-sequiturs at Arthur. It's hilarious. She sees that Flora is taken with Arthur, but since Flora was married to her nephew she resents him with great prejudice. And she never gets a name, I think, but Mr. F.'s aunt.

"Bring him for'ard, and I'll chuck him out o' winder!"

message 153:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 24, 2020 03:56PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Yes, you're right Elizabeth. We did discuss this quite a bit before: there are two full illustrated posts on the legends and history of "Bleeding Heart Yard" in the Second thread. LINK HERE for the exact posts.

The story goes back to 1626. Then I go into how Charles Dickens had an argument with the editor of the famous book of legends.

Thanks for the extra picture, Elizabeth. That looks quite a bit later - is it perhaps a local pub in the area which has taken the name?

Sad that an American journalist distorted the original meaning, Mark. How our modern cynicism seems to love to mock history, and traditional values.

Very nice observations Elizabeth on the various disguises people wear in this novel.

The story goes back to 1626. Then I go into how Charles Dickens had an argument with the editor of the famous book of legends.

Thanks for the extra picture, Elizabeth. That looks quite a bit later - is it perhaps a local pub in the area which has taken the name?

Sad that an American journalist distorted the original meaning, Mark. How our modern cynicism seems to love to mock history, and traditional values.

Very nice observations Elizabeth on the various disguises people wear in this novel.

It is sad that we have become such a cynical population, all around the world. I appreciate your thoughts on the disguises, as well, Elizabeth.

It is sad that we have become such a cynical population, all around the world. I appreciate your thoughts on the disguises, as well, Elizabeth. One of the things I most admire about Dickens is his ability to create a host of minor characters that play important parts in moving the story, and yet never leave a single one dangling at the end. We know exactly what has happened to each and every character we are presented with.

Bionic Jean wrote: "Yes, you're right Elizabeth. We did discuss this quite a bit before: there are two full illustrated posts on the legends and history of "Bleeding Heart Yard" in the Second thread. LINK HERE for the..."

Bionic Jean wrote: "Yes, you're right Elizabeth. We did discuss this quite a bit before: there are two full illustrated posts on the legends and history of "Bleeding Heart Yard" in the Second thread. LINK HERE for the..."Sorry to be repetitive - I remember now that info on The Bleeding Heart was provided before. Yes, the picture is a modern day pub near Bleeding Heart Yard called The Bleeding Heart Tavern - the restaurant section now apparently serves French cuisine!

Yes, Sara, Dickens does let us know about how all the secondary characters end up and we can see in the end how everyone is connected and played their part in the "big picture."

Yes, Sara, Dickens does let us know about how all the secondary characters end up and we can see in the end how everyone is connected and played their part in the "big picture."

message 157:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 25, 2020 06:30AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Elizabeth A.G. wrote: "The Bleeding Heart Tavern - the restaurant section now apparently serves French cuisine!..."

How funny! The blood-red exterior rather belies that. That transformation reminds me of a pub just down the road from me, which in reality is the original "Maypole Inn" at the beginning of Barnaby Rudge, but is now converted to a Thai restaurant! Also "The Six Jolly Fellowship Porters" inn of Our Mutual Friend is still there on the Thames wharf, and proud of its literary heritage. It's much frequented by actors now :)

You weren't repetitive, Elizabeth - and it gave me a chance to root out and link to the info about the Ingoldsby legends again.

How Charles Dickens's readers managed to remember all of this story for a year and a half I can't imagine! I can barely remember it for two or three months.

I too love the tying up of ends, and can't think of any other author who might mention someone minor and largely irrelevant to any other part of the action, such as Mr. Rugg's daughter, way back in the first chapters, and then pick up the threads right at the end! We still have two or three like that to come, as well as more central characters. So let's move on to see whose story reaches a conclusion in today's penultimate chapter :)

How funny! The blood-red exterior rather belies that. That transformation reminds me of a pub just down the road from me, which in reality is the original "Maypole Inn" at the beginning of Barnaby Rudge, but is now converted to a Thai restaurant! Also "The Six Jolly Fellowship Porters" inn of Our Mutual Friend is still there on the Thames wharf, and proud of its literary heritage. It's much frequented by actors now :)

You weren't repetitive, Elizabeth - and it gave me a chance to root out and link to the info about the Ingoldsby legends again.

How Charles Dickens's readers managed to remember all of this story for a year and a half I can't imagine! I can barely remember it for two or three months.

I too love the tying up of ends, and can't think of any other author who might mention someone minor and largely irrelevant to any other part of the action, such as Mr. Rugg's daughter, way back in the first chapters, and then pick up the threads right at the end! We still have two or three like that to come, as well as more central characters. So let's move on to see whose story reaches a conclusion in today's penultimate chapter :)

message 158:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 25, 2020 06:51AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Book II: Chapter 33:

Chapter 33 was also entitled “Going!” but it has an exclamation mark this time. It begins:

“The changes of a fevered room are slow and fluctuating; but the changes of the fevered world are rapid and irrevocable.”

We are not looking at the collapse of Merdle’s empire however, but one man with a fever: Arthur. He is still ill and Amy spends part of every day devotedly caring for him. She also spends time trying patiently to comfort Fanny, who is expecting a baby, and as a result:

“further advanced in that disqualified state for going into society which had so much fretted her on the evening of the tortoise-shell knife”.

Amy also helps Tip, who seems to have drunk himself into a state of delerium tremens, and is now:

“a weak, proud, tipsy, young old man, shaking from head to foot, talking as indistinctly as if some of the money he plumed himself upon had got into his mouth and couldn’t be got out, unable to walk alone in any act of his life, and patronising the sister whom he selfishly loved (he always had that negative merit, ill-starred and ill-launched Tip!) because he suffered her to lead him.”

The narrator says that Mrs. Merdle may have grieved for her husband for a little while, but soon paid attention to her mourning cap, and made sure it was flattering, and of the best Parisian lace. Fanny and Mrs. Merdle are constantly at war with one another, whilst Edmund Sparkler tries to keep the peace, by saying they are “both remarkably fine women, and that there was no nonsense about either of them—” at which they both turn on him.

Mrs. General is back in England and “sending a Prune and a Prism by post every other day”, to which she receives increasingly complimentary replies, although nobody happens to want her services at the moment.

Nobody is sure how to treat Mrs. Merdle. Should they sympathise with her, or cut her dead? Mrs. Merdle herself soon decides that the wisest course of action is to be just as angry as being deceived as anyone else, and is soon back in Society.

Everyone has lost their money through Merdle’s scams. Now that the money is gone Fanny and her husband share “the genteel little temple of inconvenience [with] the smell of the day before yesterday’s soup and coach-horses”, keeping to a different floor from Mrs. Merdle. Little Dorrit watches all this, and wonders what will happen to Fanny’s children, those “unborn little victims”.

Amy writes to Mr. Meagles, who is still overseas, to tell him that Arthur is ill, and in the Marshalsea. She confides in him about the box and papers without telling him any specific details. Mr. Meagles, with his banking experience and quick mind, realises the importance of trying to get the original papers back. He says he won’t come back until he has done his best to find them.

Henry Gowan has now decided that it would be better if he didn’t know the Meagles any more. Mr. Meagles has agreed to this, since he can see it is making his daughter unhappy, to see the way her parents are treated by Henry Gowan. As a result, Mr. and Mrs. Meagles are even more generous, now that they only see Pet (Minnie) and their little grandchild. This is satisfactory for Henry Gowan, as he is provided with more money, without having to openly acknowledge it.

Mr. Meagles finds out from his daughter the various towns where Blandois had been, since for a long time he had been their regular companion. He makes a list of the inns and hotels he had stayed at, and goes in search of him. He pays all the unpaid bills, and brings away anything that had been left there for safe keeping. Mr. Meagles is as intolerant as ever of those who do not speak his own language of English, haranguing them and saying that they are “all bosh”. On four occasions the police have to be called in, but it does not affect him much:

“[he] was in the most ignominious manner escorted to steam-boats and public carriages, to be got rid of, talking all the while, like a cheerful and fluent Briton as he was, with Mother under his arm.”

However, the narrator observes that Mr. Meagles is clear, shrewd and persevering. By the time he has worked round to Paris, he believes he is nearing his quarry, as it is more accessible from England. Sure enough, there he finds a letter from Little Dorrit, waiting for him. In it, she says that she had been able to talk to Arthur and he had told her about his trip to Calais, to see Miss Wade, in search of the man they are trying to trace (Blandois).

“‘Oho!’ said Mr Meagles.”

Mr. Meagles too calls at the home of Miss Wade, who is not at all pleased to see him. He tries to be polite, but unknowingly compounds her dislike of him by mentioning that his daughter has had a child by (her own romantic interest) Henry Gowan. Mr. Meagles asks her if Blandois happened to leave anything with her: a box perhaps, or a bundle of papers? It is not only he who would like to know, but also Arthur Clennam, and “other people”.

Mr. Meagles can see how angry she is:

“‘Upon my word,’ she returned, ‘I seem to be a mark for everybody who knew anything of a man I once in my life hired, and paid, and dismissed, to aim their questions at!’”

She goes on to deny knowing anything about a box or any papers, telling him that she knows nothing; they were not left with her. Mr. Meagles asks her to give Tattycoram a kind word from him, realising as she corrects the name:

“I have put my foot in it again … I can’t keep my foot out of it here, it seems. Perhaps, if I had thought twice about it, I might never have given her the jingling name. But, when one means to be good-natured and sportive with young people, one doesn’t think twice.”

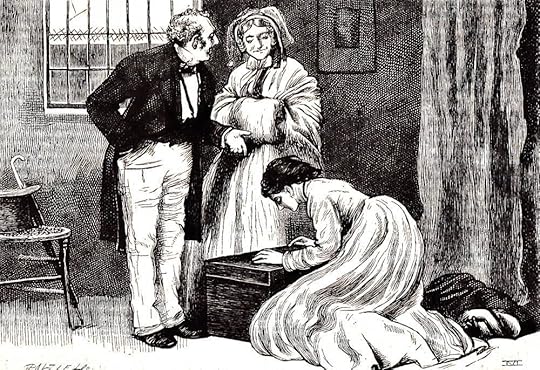

He and Mrs. Meagles then leave, and go immediately back to London, to arrive at the Marshalsea prison that evening. John is on duty and tells them that Arthur is slowly getting better, and Maggy, Mrs. Plornish and Mr. Baptist all take turns to look after him. Amy is out, so he shows them to the upstairs room, to wait for her:

“The cramped area of the prison had such an effect on Mrs Meagles that she began to weep, and such an effect on Mr Meagles that he began to gasp for air.”

As they are waiting, the door opens, but instead of being Little Dorrit it is Tattycoram (Harriet).

She is carrying an iron box: the very box, the narrator explains, that Affery had seen in her dream. She is:

“crying half in exultation and half in despair, half in laughter and half in tears”, and appeals to them to take her back.

Tattycoram tells them that this is the box which Mr. Meagles was asking about.

Mr. and Mrs. Meagles and Tattycoram - James Mahoney

She had heard Miss Wade deny having it, and knew that she would “sooner have sunk it in the sea, or burnt it” than give it to him. So Tattycoram took the box with her, crossing on the same boat that they had. She looks full of a “glow and rapture” to be with them again, saying that being with Miss Wade had made her wretched. She tells them Miss Wade worked on her, so that whenever she saw someone kind, the worse fault she found with them:

“I have had Miss Wade before me all this time, as if it was my own self grown ripe—turning everything the wrong way, and twisting all good into evil. I have had her before me all this time, finding no pleasure in anything but keeping me as miserable, suspicious, and tormenting as herself.” And she begs them to talk to their daughter, so she might forgive her too:

“I’ll try very hard. I won’t stop at five-and-twenty, sir, I’ll count five-and-twenty hundred, five-and-twenty thousand!”

Amy arrives and Mr. Meagles produces the box with “pride and joy”. Little Dorrit is full of grateful happiness and joy, relieved that now there is no danger from these papers any more. Her secret is safe, and she need never tell Arthur the whole story.

“That was all passed, all forgiven, all forgotten.”

Mr. Meagles asks if he could see Arthur today, but Little Dorrit thinks not yet. She will go to see how he is. As they watch Little Dorrit through the window, Mr. Meagles gives a gentle word of advice to Tattycoram about duty, using Little Dorrit—the child of the Marshalsea—as an example.

When she returns, Mr. Meagles says that the three of them, including Tattycoram, will stay in an hotel. The next day Mrs. Meagles and Tattycoram will return home, but he will be leaving for abroad again. He can’t stand the thought of Arthur being shut up in prison, and is going to find Daniel Doyce and bring him back home.

The chapter ends with Amy kissing his hand, and when he objects, his cheek. He is saddened to think of his daughter, consoling himself a little:

“You remind me of the days …—but she’s very fond of him, and hides his faults, and thinks that no one sees them—and he certainly is well connected and of a very good family!”

Chapter 33 was also entitled “Going!” but it has an exclamation mark this time. It begins:

“The changes of a fevered room are slow and fluctuating; but the changes of the fevered world are rapid and irrevocable.”

We are not looking at the collapse of Merdle’s empire however, but one man with a fever: Arthur. He is still ill and Amy spends part of every day devotedly caring for him. She also spends time trying patiently to comfort Fanny, who is expecting a baby, and as a result:

“further advanced in that disqualified state for going into society which had so much fretted her on the evening of the tortoise-shell knife”.

Amy also helps Tip, who seems to have drunk himself into a state of delerium tremens, and is now:

“a weak, proud, tipsy, young old man, shaking from head to foot, talking as indistinctly as if some of the money he plumed himself upon had got into his mouth and couldn’t be got out, unable to walk alone in any act of his life, and patronising the sister whom he selfishly loved (he always had that negative merit, ill-starred and ill-launched Tip!) because he suffered her to lead him.”

The narrator says that Mrs. Merdle may have grieved for her husband for a little while, but soon paid attention to her mourning cap, and made sure it was flattering, and of the best Parisian lace. Fanny and Mrs. Merdle are constantly at war with one another, whilst Edmund Sparkler tries to keep the peace, by saying they are “both remarkably fine women, and that there was no nonsense about either of them—” at which they both turn on him.

Mrs. General is back in England and “sending a Prune and a Prism by post every other day”, to which she receives increasingly complimentary replies, although nobody happens to want her services at the moment.

Nobody is sure how to treat Mrs. Merdle. Should they sympathise with her, or cut her dead? Mrs. Merdle herself soon decides that the wisest course of action is to be just as angry as being deceived as anyone else, and is soon back in Society.

Everyone has lost their money through Merdle’s scams. Now that the money is gone Fanny and her husband share “the genteel little temple of inconvenience [with] the smell of the day before yesterday’s soup and coach-horses”, keeping to a different floor from Mrs. Merdle. Little Dorrit watches all this, and wonders what will happen to Fanny’s children, those “unborn little victims”.

Amy writes to Mr. Meagles, who is still overseas, to tell him that Arthur is ill, and in the Marshalsea. She confides in him about the box and papers without telling him any specific details. Mr. Meagles, with his banking experience and quick mind, realises the importance of trying to get the original papers back. He says he won’t come back until he has done his best to find them.

Henry Gowan has now decided that it would be better if he didn’t know the Meagles any more. Mr. Meagles has agreed to this, since he can see it is making his daughter unhappy, to see the way her parents are treated by Henry Gowan. As a result, Mr. and Mrs. Meagles are even more generous, now that they only see Pet (Minnie) and their little grandchild. This is satisfactory for Henry Gowan, as he is provided with more money, without having to openly acknowledge it.

Mr. Meagles finds out from his daughter the various towns where Blandois had been, since for a long time he had been their regular companion. He makes a list of the inns and hotels he had stayed at, and goes in search of him. He pays all the unpaid bills, and brings away anything that had been left there for safe keeping. Mr. Meagles is as intolerant as ever of those who do not speak his own language of English, haranguing them and saying that they are “all bosh”. On four occasions the police have to be called in, but it does not affect him much:

“[he] was in the most ignominious manner escorted to steam-boats and public carriages, to be got rid of, talking all the while, like a cheerful and fluent Briton as he was, with Mother under his arm.”

However, the narrator observes that Mr. Meagles is clear, shrewd and persevering. By the time he has worked round to Paris, he believes he is nearing his quarry, as it is more accessible from England. Sure enough, there he finds a letter from Little Dorrit, waiting for him. In it, she says that she had been able to talk to Arthur and he had told her about his trip to Calais, to see Miss Wade, in search of the man they are trying to trace (Blandois).

“‘Oho!’ said Mr Meagles.”

Mr. Meagles too calls at the home of Miss Wade, who is not at all pleased to see him. He tries to be polite, but unknowingly compounds her dislike of him by mentioning that his daughter has had a child by (her own romantic interest) Henry Gowan. Mr. Meagles asks her if Blandois happened to leave anything with her: a box perhaps, or a bundle of papers? It is not only he who would like to know, but also Arthur Clennam, and “other people”.

Mr. Meagles can see how angry she is:

“‘Upon my word,’ she returned, ‘I seem to be a mark for everybody who knew anything of a man I once in my life hired, and paid, and dismissed, to aim their questions at!’”

She goes on to deny knowing anything about a box or any papers, telling him that she knows nothing; they were not left with her. Mr. Meagles asks her to give Tattycoram a kind word from him, realising as she corrects the name:

“I have put my foot in it again … I can’t keep my foot out of it here, it seems. Perhaps, if I had thought twice about it, I might never have given her the jingling name. But, when one means to be good-natured and sportive with young people, one doesn’t think twice.”

He and Mrs. Meagles then leave, and go immediately back to London, to arrive at the Marshalsea prison that evening. John is on duty and tells them that Arthur is slowly getting better, and Maggy, Mrs. Plornish and Mr. Baptist all take turns to look after him. Amy is out, so he shows them to the upstairs room, to wait for her:

“The cramped area of the prison had such an effect on Mrs Meagles that she began to weep, and such an effect on Mr Meagles that he began to gasp for air.”

As they are waiting, the door opens, but instead of being Little Dorrit it is Tattycoram (Harriet).

She is carrying an iron box: the very box, the narrator explains, that Affery had seen in her dream. She is:

“crying half in exultation and half in despair, half in laughter and half in tears”, and appeals to them to take her back.

Tattycoram tells them that this is the box which Mr. Meagles was asking about.

Mr. and Mrs. Meagles and Tattycoram - James Mahoney

She had heard Miss Wade deny having it, and knew that she would “sooner have sunk it in the sea, or burnt it” than give it to him. So Tattycoram took the box with her, crossing on the same boat that they had. She looks full of a “glow and rapture” to be with them again, saying that being with Miss Wade had made her wretched. She tells them Miss Wade worked on her, so that whenever she saw someone kind, the worse fault she found with them:

“I have had Miss Wade before me all this time, as if it was my own self grown ripe—turning everything the wrong way, and twisting all good into evil. I have had her before me all this time, finding no pleasure in anything but keeping me as miserable, suspicious, and tormenting as herself.” And she begs them to talk to their daughter, so she might forgive her too:

“I’ll try very hard. I won’t stop at five-and-twenty, sir, I’ll count five-and-twenty hundred, five-and-twenty thousand!”

Amy arrives and Mr. Meagles produces the box with “pride and joy”. Little Dorrit is full of grateful happiness and joy, relieved that now there is no danger from these papers any more. Her secret is safe, and she need never tell Arthur the whole story.

“That was all passed, all forgiven, all forgotten.”

Mr. Meagles asks if he could see Arthur today, but Little Dorrit thinks not yet. She will go to see how he is. As they watch Little Dorrit through the window, Mr. Meagles gives a gentle word of advice to Tattycoram about duty, using Little Dorrit—the child of the Marshalsea—as an example.

When she returns, Mr. Meagles says that the three of them, including Tattycoram, will stay in an hotel. The next day Mrs. Meagles and Tattycoram will return home, but he will be leaving for abroad again. He can’t stand the thought of Arthur being shut up in prison, and is going to find Daniel Doyce and bring him back home.

The chapter ends with Amy kissing his hand, and when he objects, his cheek. He is saddened to think of his daughter, consoling himself a little:

“You remind me of the days …—but she’s very fond of him, and hides his faults, and thinks that no one sees them—and he certainly is well connected and of a very good family!”

message 159:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 25, 2020 07:02AM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

And a little more ...

about the Circumlocution Office:

Mark noted that the "barbaric power" referred to Russia.

Calling a country a barbaric power is hardly flattering, just as it wouldn’t be to call a person a “barbarian”. Charles Dickens wrote a Preface to the first book edition of Little Dorrit, in 1857. He mentions Russia there, and I suggest we read that after the final chapter.

We were told in Book 2 chapter 22:

“This Power, being a barbaric one, had no idea of stowing away a great national object in a Circumlocution Office, as strong wine is hidden from the light in a cellar until its fire and youth are gone, and the labourers who worked in the vineyard and pressed the grapes are dust.”

We have seen that the Circumlocution Office is a place where all innovation, creativity and individualism is effectively stifled, and preferably wiped out. Here Charles Dickens seems to be praising Russia, in contrast.

Little Dorrit was set in 1827. The UK had been at war with Russia between 1807–1812, (although this was mainly naval actions) and was to be at war with them again during the Crimean war, between October 1853 and March 1856. The story of Little Dorrit itself was published as a serial between December 1855 and June 1857—i.e. while the two countries were still at war.

It puzzled me that Charles Dickens should be expressing this approval. His terminology left a bit to be desired, but he still portrayed the Barbaric power as being considerably more energetic and forward-thinking than the British (Government’s) Circumlocution Office.

Perhaps it has more to do with the Great Exhibition at Crystal Palace in May 1851—just a few years earlier. Here England celebrated its grand industrial and social advances, and since it was called the World’s Fair, inventions from other western countries were included as well.

It’s possible that Charles Dickens intended to show that the British government had become more rigid after the 1851 exhibition at Crystal Palace, or how the British political system was very stifling leading up to the Great Exhibition. Or perhaps, after all, the Circumlocution Office was simply meant to represent how government stifled human enterprise. It's not completely clear.

There certainly a grim sort of irony, in that the Circumlocution Office is a government agency which thrives on inaction: "How Not to do it" while the criminal Blandois is a man of action who causes the unassuming Arthur to act. The government, doing nothing to help its citizens, is depicted in contrast to the criminal, who seems to be capable and willing to do anything to succeed.

about the Circumlocution Office:

Mark noted that the "barbaric power" referred to Russia.

Calling a country a barbaric power is hardly flattering, just as it wouldn’t be to call a person a “barbarian”. Charles Dickens wrote a Preface to the first book edition of Little Dorrit, in 1857. He mentions Russia there, and I suggest we read that after the final chapter.

We were told in Book 2 chapter 22:

“This Power, being a barbaric one, had no idea of stowing away a great national object in a Circumlocution Office, as strong wine is hidden from the light in a cellar until its fire and youth are gone, and the labourers who worked in the vineyard and pressed the grapes are dust.”

We have seen that the Circumlocution Office is a place where all innovation, creativity and individualism is effectively stifled, and preferably wiped out. Here Charles Dickens seems to be praising Russia, in contrast.

Little Dorrit was set in 1827. The UK had been at war with Russia between 1807–1812, (although this was mainly naval actions) and was to be at war with them again during the Crimean war, between October 1853 and March 1856. The story of Little Dorrit itself was published as a serial between December 1855 and June 1857—i.e. while the two countries were still at war.

It puzzled me that Charles Dickens should be expressing this approval. His terminology left a bit to be desired, but he still portrayed the Barbaric power as being considerably more energetic and forward-thinking than the British (Government’s) Circumlocution Office.

Perhaps it has more to do with the Great Exhibition at Crystal Palace in May 1851—just a few years earlier. Here England celebrated its grand industrial and social advances, and since it was called the World’s Fair, inventions from other western countries were included as well.

It’s possible that Charles Dickens intended to show that the British government had become more rigid after the 1851 exhibition at Crystal Palace, or how the British political system was very stifling leading up to the Great Exhibition. Or perhaps, after all, the Circumlocution Office was simply meant to represent how government stifled human enterprise. It's not completely clear.

There certainly a grim sort of irony, in that the Circumlocution Office is a government agency which thrives on inaction: "How Not to do it" while the criminal Blandois is a man of action who causes the unassuming Arthur to act. The government, doing nothing to help its citizens, is depicted in contrast to the criminal, who seems to be capable and willing to do anything to succeed.

Yay we are going to see Dan Doyce again! I don't know why I like him so much, but I really do! I love the way things are being slowely wound up, and it does not feel rushed at all! Of course, this is a very long novel so there has been plenty of time to spin the threads!

Yay we are going to see Dan Doyce again! I don't know why I like him so much, but I really do! I love the way things are being slowely wound up, and it does not feel rushed at all! Of course, this is a very long novel so there has been plenty of time to spin the threads!

Re the Circumlocution Office, it seems even worse than the Court of Chancery in Bleak House to me.

Re the Circumlocution Office, it seems even worse than the Court of Chancery in Bleak House to me. At least Chancery is trying to meet some ends by deciding lawsuits and wills. If it is awful at it, that's due to everyone suing and counter-suing, and hiring more lawyers. But the Tite Barnacles have as their goal: Not. Doing. Anything.

In Taoism there is something called Wu Wei, no-action. It means acting effortlessly, going with the natural flow instead of against it. Like hanging a gate at a slight angle on the hinges so that the gate closes by gravity, no spring needed. That's not the No Action of the CO.

The CO is the incarnation of passive aggression. They avoid doing things in order that others will fail, all the while handing out more forms to be completed, and employing more Barnacles and Stiltstalkings.

Ferdinand said nobody (at the CO) cares about the inventions. But they're somewhat like the patent office if I understand correctly their charge. It's a satire of giant bureaucracies that serve no real interest except to be dysfunctional and wind up hurting the people they are supposed to help with forms that serve only to need more forms. (I can imagine someone trying to navigate the immigration departments in most countries.)

'In our country,' said Alice, still panting a little, 'you'd generally get to somewhere else if you ran very fast for a long time, as we've been doing.' 'A slow sort of country!' said the Queen. 'Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that!'

About audiences following the plot of this book over the time it took to wait for the next installments - I would guess it was a cultural touchstone like modern TV series or reality shows, where people discussed the story with their family and friends. Maybe they even reread the previous segments. It wasn't only Dickens who wrote in installments so I supposed people were used to that. But I don't know. I wonder if there are any letters or diaries surviving from regular readers of Dickens' serialized books?

About audiences following the plot of this book over the time it took to wait for the next installments - I would guess it was a cultural touchstone like modern TV series or reality shows, where people discussed the story with their family and friends. Maybe they even reread the previous segments. It wasn't only Dickens who wrote in installments so I supposed people were used to that. But I don't know. I wonder if there are any letters or diaries surviving from regular readers of Dickens' serialized books?

I was glad Tattycoram saw Miss. Wade for what see was and did not want to live that way. Always unhappy, always looking for the bad. Hopefully Tattycoram will take pride in her work and look to Little Dorrit as inspiration (as Mr. Meagles pointed out). At the beginning of this story, I thought Miss. Wade was going to have an entirely different role.

I was glad Tattycoram saw Miss. Wade for what see was and did not want to live that way. Always unhappy, always looking for the bad. Hopefully Tattycoram will take pride in her work and look to Little Dorrit as inspiration (as Mr. Meagles pointed out). At the beginning of this story, I thought Miss. Wade was going to have an entirely different role. I never liked the Circumlocution Office in this story. Never saw the humor in it.

I am also looking forward to seeing Doyce again.

Robin, I would love to read those letters/diaries too.

Miss Wade. I thought Dickens' take on lesbianism/bisexuality (if that's what it was), was stacked against Miss Wade. Making her a rejected lover from a "normal" relationship and always looking for revenge, and filled with hatred, probably was the most sympathetic he could go. And with the long letter he tries to paint her somewhat sympathetically even though her cynical nature shows through.

Miss Wade. I thought Dickens' take on lesbianism/bisexuality (if that's what it was), was stacked against Miss Wade. Making her a rejected lover from a "normal" relationship and always looking for revenge, and filled with hatred, probably was the most sympathetic he could go. And with the long letter he tries to paint her somewhat sympathetically even though her cynical nature shows through. It is surprising that she even appears in the story given the period. She isn't a criminal, she's intelligent, self-supporting, and psychologically independent. She is one of the most "individual" people in the book who has her own morality. So I give her credit for that.

I was also glad to see Tatty return to the Meagles and reject the hatred mantra of Miss Wade. I should like to think both Tatty and the Meagles have learned something; she will be happier with the kindnesses she receives, and having lost Pet, perhaps they will be more attentive to Tatty's emotional needs and value her company.

I was also glad to see Tatty return to the Meagles and reject the hatred mantra of Miss Wade. I should like to think both Tatty and the Meagles have learned something; she will be happier with the kindnesses she receives, and having lost Pet, perhaps they will be more attentive to Tatty's emotional needs and value her company. I tend to reject the modern reading of Miss Wade. I do not think there is evidence that she is a lesbian, since she had two serious relationships with men and her aim with Tatty seems very much to twist her into a clone of herself. The old "misery loves company" adage at work. Miss Wade seems to me just a misanthrope who hates everyone because she is unhappy with herself. That does not seem to have a sexual root to me. JMHO--no one stone me.

The idea of the diaries is intriguing. Wouldn't it be wonderful to have a first hand reaction from a reader. I will say that we have Louisa May Alcott's contemporary opinion of the Pickwick Papers and she has the girls in Little Women reading it repeatedly and acting out scenes from it together, so we know it wasn't a read it once and dispose of it reading experience.

message 167:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 25, 2020 01:16PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

More on the Circumlocution Office:

Mark wrote: "Re the Circumlocution Office, it seems even worse than the Court of Chancery in Bleak House to me ..."

Yes it's an even more facetious depiction. The Chancery of Bleak House is a hopeless, bumbling institution which topples under its own weight, whereas the Circumlocution Office has a stated purpose from the start, of - as you nicely put it - passive aggression: "How Not To Do It". Keep the status quo. Don't rock the boat. Whatever you do, don't allow for any new ideas, creativity or useful developments.

I had forgotten that I went into Charles Dickens position on government institutions such as the civil service before, when I read a short book by John Carey about the first films. LINK HERE if you like, for my review of that.

There was apparently public outrage at reports of mismanagement of the Crimean War, which, as noted, was when Charles Dickens began writing his serial. Unemployment was widespread and there were bread riots in the East End of London, with dockers looting bakers’ shops.

Charles Dickens himself took a leading role in the “Administrative Reform Association” giving speeches which attacked the idle aristocracy, the ineffectiveness of parliament, and what he called the “dandy insolence” of the Prime Minister, Palmerston.

His original titling of the novel as “Nobody’s Fault” was heavily ironic: a direct criticism of these prevailing ideas. To say that all the evil events were “Nobody’s Fault”, he felt, was sheer hypocrisy, and in this novel he would lay the blame squarely at one man’s door.

But in fact, as the novel proceeded, Charles Dickens’s view also developed. He was to show that the evil was more widespread, and entangled with the very structure of society - and everyone’s tacit acceptance of it. Coming to the end of the novel, we now see that almost everyone bears some of the blame. John Carey suggests that this may have been the reason why Charles Dickens changed his title partway through his serial:

“Perhaps Dickens came to suspect, it was everyone’s fault - as Amy Dorrit, with her usual wisdom, suggests towards the end of the film.”

John Carey has traced a parallel with Fyodor Dostoyevsky in Charles Dickens’s work, as we have observed before in our discussions here. In fact he considers that Charles Dickens’s invention of the Circumlocution Office, that great symbol of faceless bureaucracy, led directly to:

“Kafka’s official buildings with their hopeless waiting rooms and fearsome interrogators”.

Certainly we know that Franz Kafka read Dickens, but Kafka created a surreal “wilfully malign” horror, and that was not Charles Dickens’s way. Dickens’s stultified creation is peopled with: “monocled nincompoops and ... shifty-eyed whispering clerks”, recognisable even today in England in a stubborn, cheerful obstructiveness, and what we term “red tape”.

Charles Dickens sourly referred to our: “right little, tight little island”. His novel, “Little Dorrit”, is in part “a satire on the nepotism and inefficiency of the Civil Service” as he saw it. It was an expression of his outrage at the conditions at the time.

Incredibly enough, a government report of 1855 had shown that some officials were almost illiterate, and “lucrative posts had gone to mentally handicapped candidates”. Charles Dickens converted this for the entertainment of his readers of the time - and our delight - into the Barnacles and Stiltstalkings, (including by the end, the dunderhead Edmund Sparkler), but what lay beneath was Charles Dickens's savage indignation and fury about what he could see happening in real life.

Perhaps nowadays some readers can detect the underlying sourness Charles Dickens felt, and this dampens the humour. Debra, I don't think you're alone for one minute! But I personally like the absurd in Charles Dickens's writing, and prefer it to the grimness of the Russian writers :)

Mark wrote: "Re the Circumlocution Office, it seems even worse than the Court of Chancery in Bleak House to me ..."

Yes it's an even more facetious depiction. The Chancery of Bleak House is a hopeless, bumbling institution which topples under its own weight, whereas the Circumlocution Office has a stated purpose from the start, of - as you nicely put it - passive aggression: "How Not To Do It". Keep the status quo. Don't rock the boat. Whatever you do, don't allow for any new ideas, creativity or useful developments.

I had forgotten that I went into Charles Dickens position on government institutions such as the civil service before, when I read a short book by John Carey about the first films. LINK HERE if you like, for my review of that.

There was apparently public outrage at reports of mismanagement of the Crimean War, which, as noted, was when Charles Dickens began writing his serial. Unemployment was widespread and there were bread riots in the East End of London, with dockers looting bakers’ shops.

Charles Dickens himself took a leading role in the “Administrative Reform Association” giving speeches which attacked the idle aristocracy, the ineffectiveness of parliament, and what he called the “dandy insolence” of the Prime Minister, Palmerston.

His original titling of the novel as “Nobody’s Fault” was heavily ironic: a direct criticism of these prevailing ideas. To say that all the evil events were “Nobody’s Fault”, he felt, was sheer hypocrisy, and in this novel he would lay the blame squarely at one man’s door.

But in fact, as the novel proceeded, Charles Dickens’s view also developed. He was to show that the evil was more widespread, and entangled with the very structure of society - and everyone’s tacit acceptance of it. Coming to the end of the novel, we now see that almost everyone bears some of the blame. John Carey suggests that this may have been the reason why Charles Dickens changed his title partway through his serial:

“Perhaps Dickens came to suspect, it was everyone’s fault - as Amy Dorrit, with her usual wisdom, suggests towards the end of the film.”

John Carey has traced a parallel with Fyodor Dostoyevsky in Charles Dickens’s work, as we have observed before in our discussions here. In fact he considers that Charles Dickens’s invention of the Circumlocution Office, that great symbol of faceless bureaucracy, led directly to:

“Kafka’s official buildings with their hopeless waiting rooms and fearsome interrogators”.

Certainly we know that Franz Kafka read Dickens, but Kafka created a surreal “wilfully malign” horror, and that was not Charles Dickens’s way. Dickens’s stultified creation is peopled with: “monocled nincompoops and ... shifty-eyed whispering clerks”, recognisable even today in England in a stubborn, cheerful obstructiveness, and what we term “red tape”.

Charles Dickens sourly referred to our: “right little, tight little island”. His novel, “Little Dorrit”, is in part “a satire on the nepotism and inefficiency of the Civil Service” as he saw it. It was an expression of his outrage at the conditions at the time.

Incredibly enough, a government report of 1855 had shown that some officials were almost illiterate, and “lucrative posts had gone to mentally handicapped candidates”. Charles Dickens converted this for the entertainment of his readers of the time - and our delight - into the Barnacles and Stiltstalkings, (including by the end, the dunderhead Edmund Sparkler), but what lay beneath was Charles Dickens's savage indignation and fury about what he could see happening in real life.

Perhaps nowadays some readers can detect the underlying sourness Charles Dickens felt, and this dampens the humour. Debra, I don't think you're alone for one minute! But I personally like the absurd in Charles Dickens's writing, and prefer it to the grimness of the Russian writers :)

Terrific background, Jean! Unfortunately, I can see this same system still at work in our own society. People are frequently given important positions and promotions based on connections rather than qualifications. The higher up the ladder you go, the more likely you are to find this true, so no surprise that the Barnacles and Stiltstalkings are at the tippy-top.

Terrific background, Jean! Unfortunately, I can see this same system still at work in our own society. People are frequently given important positions and promotions based on connections rather than qualifications. The higher up the ladder you go, the more likely you are to find this true, so no surprise that the Barnacles and Stiltstalkings are at the tippy-top. Perhaps one of the reasons Dickens still has so much appeal is that he attacks problems in his society that still exist in ours.

Sara wrote: "I was also glad to see Tatty return to the Meagles and reject the hatred mantra of Miss Wade. I should like to think both Tatty and the Meagles have learned something; she will be happier with the ..."

Sara wrote: "I was also glad to see Tatty return to the Meagles and reject the hatred mantra of Miss Wade. I should like to think both Tatty and the Meagles have learned something; she will be happier with the ..."Sara, I won't stone you. I agree with everything you said about Miss Wade.

I agree again with Sara. The Barnacles and Stiltstockings are still in charge of our government. Nothing seems to change, at least in the US.

I agree again with Sara. The Barnacles and Stiltstockings are still in charge of our government. Nothing seems to change, at least in the US.

message 171:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 25, 2020 03:53PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Miss Wade and Tattycoram:

Mark wrote: "Miss Wade... She isn't a criminal, she's intelligent, self-supporting, and psychologically independent ..."

We do tend to forget this, and only see Miss Wade's embittered, manipulative side. But as we discussed earlier, it is not her observations about people's motives that are warped. It is her response to them. All motives are complex, and partly self-serving: not usually entirely good or entirely bad.

Miss Wade is strong and individual. There are aspects of her which are present in other characters by Charles Dickens, but not completely; she is unique and fascinating. I am rather unhappy about the ending of Tattycoram's story, as she casts Miss Wade in a villainous role. It's not that clear.

Mr. Meagles is no angel himself, with his prejudice against anyone who is not English - much as Charles Dickens attempts to make him endearing.

Miss Wade was attempting to make Harriet think for herself. Harriet's description of her is also a biased one - biased toward her controlling aspect. We do not really know what would happen if she stayed with Miss Wade, but we do know that with the Meagles she is destined to be a servant all her life, to "know her place", and do her duty. And we are expected to know as an unchallenged fact that this is preferable. It's all part and parcel of Victorian hypocrisy. The Meagles' only saving grace to me, is that they are not unkind to her. Otherwise we could have a novel where Tattycoram flees from servitude, is found to be heir to the fortune of an African Prince, thus allowing her to develop her hidden talents and become a best-selling writer, for instance!

Sara and Anne - We all have a right to our opinions :) I like her Miss Wade very much as a character, but not as a person. Mark called her "Cassandra" and she does fulfil that function well.

The critics don't all agree as to Miss Wade's sexual tendencies. I personally believe that she had been attracted to Henry Gowan's audacity, as much as anything. It would be wrong to view her in modern terms, and go into specifics of gender identity, or gynaephilia, but even in Victorian society it was known about lesbianism (except for the Queen, who refused to believe it when it was suggested to pass a law against the practise).

In this novel, Mr. Meagles referred to it obliquely. So Charles Dickens might have been thinking of a "manly woman" perhaps someone whose encounter with the dastardly Henry confirmed her latent lesbian tendencies.

The entire subplot of Tattycoram/Harriet and Miss Wade was missed out of the 6 hour 1987 miniseries, and Professor John Carey postulates that this might be why. It is unclear. I believe it is heavily suggested in the subtext, just as I see indications that Tattycoram's ethnicity is blurred, but probably black, or perhaps Spanish/Italian/French (thinking of a few other characters).

I think Charles Dickens could not be very specific, just as he couldn't refer directly to Fanny's pregnancy, as we all noticed. And that was respectable enough - within a marriage - yet the Victorians would still shroud the condition in euphemisms.

Charles Dickens could never publish something akin to Flaubert’s “Madam Bovary” - his public would not accept it. English writing was dominated by “horrid respectability”. It has been surmised that Dickens would have written Miss Wade as a more obviously lesbian character, were it not for this, and her character is dropped from these two films entirely. Charles Dickens was constrained by Victorian morality regarding his marriage and his relationship with the young actress Ellen Ternan. Furthermore, as John Carey reminds us:

“Polite society regarded him as an upstart; the educated disparaged his writings; well-born authors such as Thackeray sneered at his flashy clothes and wrote him off as ‘not a gentleman’”.

Charles Dickens, for all his fame and popularity, still had to be very careful what he wrote.

Mark wrote: "Miss Wade... She isn't a criminal, she's intelligent, self-supporting, and psychologically independent ..."

We do tend to forget this, and only see Miss Wade's embittered, manipulative side. But as we discussed earlier, it is not her observations about people's motives that are warped. It is her response to them. All motives are complex, and partly self-serving: not usually entirely good or entirely bad.

Miss Wade is strong and individual. There are aspects of her which are present in other characters by Charles Dickens, but not completely; she is unique and fascinating. I am rather unhappy about the ending of Tattycoram's story, as she casts Miss Wade in a villainous role. It's not that clear.

Mr. Meagles is no angel himself, with his prejudice against anyone who is not English - much as Charles Dickens attempts to make him endearing.

Miss Wade was attempting to make Harriet think for herself. Harriet's description of her is also a biased one - biased toward her controlling aspect. We do not really know what would happen if she stayed with Miss Wade, but we do know that with the Meagles she is destined to be a servant all her life, to "know her place", and do her duty. And we are expected to know as an unchallenged fact that this is preferable. It's all part and parcel of Victorian hypocrisy. The Meagles' only saving grace to me, is that they are not unkind to her. Otherwise we could have a novel where Tattycoram flees from servitude, is found to be heir to the fortune of an African Prince, thus allowing her to develop her hidden talents and become a best-selling writer, for instance!

Sara and Anne - We all have a right to our opinions :) I like her Miss Wade very much as a character, but not as a person. Mark called her "Cassandra" and she does fulfil that function well.

The critics don't all agree as to Miss Wade's sexual tendencies. I personally believe that she had been attracted to Henry Gowan's audacity, as much as anything. It would be wrong to view her in modern terms, and go into specifics of gender identity, or gynaephilia, but even in Victorian society it was known about lesbianism (except for the Queen, who refused to believe it when it was suggested to pass a law against the practise).

In this novel, Mr. Meagles referred to it obliquely. So Charles Dickens might have been thinking of a "manly woman" perhaps someone whose encounter with the dastardly Henry confirmed her latent lesbian tendencies.

The entire subplot of Tattycoram/Harriet and Miss Wade was missed out of the 6 hour 1987 miniseries, and Professor John Carey postulates that this might be why. It is unclear. I believe it is heavily suggested in the subtext, just as I see indications that Tattycoram's ethnicity is blurred, but probably black, or perhaps Spanish/Italian/French (thinking of a few other characters).

I think Charles Dickens could not be very specific, just as he couldn't refer directly to Fanny's pregnancy, as we all noticed. And that was respectable enough - within a marriage - yet the Victorians would still shroud the condition in euphemisms.

Charles Dickens could never publish something akin to Flaubert’s “Madam Bovary” - his public would not accept it. English writing was dominated by “horrid respectability”. It has been surmised that Dickens would have written Miss Wade as a more obviously lesbian character, were it not for this, and her character is dropped from these two films entirely. Charles Dickens was constrained by Victorian morality regarding his marriage and his relationship with the young actress Ellen Ternan. Furthermore, as John Carey reminds us:

“Polite society regarded him as an upstart; the educated disparaged his writings; well-born authors such as Thackeray sneered at his flashy clothes and wrote him off as ‘not a gentleman’”.

Charles Dickens, for all his fame and popularity, still had to be very careful what he wrote.

I'm no expert on Victorian times but what they thought -- especially a male author thought-- lesbians were I'm sure differs from our modern views.

I'm no expert on Victorian times but what they thought -- especially a male author thought-- lesbians were I'm sure differs from our modern views. It could be that Dickens thought they were frustrated heterosexuals. So the fact that Miss Wade is presented as having had several male crushes may not mean that Dickens thinks she's not lesbian.

It does seem pretty clear that she has 0 interest in any male figures as friends.

I'm also glad that Tattycoram returned to the Meagles, and with Pet gone, I'm sure they would be doubly glad to have Tattycoram back. And maybe both sides will behave better.

And I also have some admiration for the character of Miss Wade, whatever her orientation may be. Dickens usually punishes his villains (Flintwinch makes an escape as an exception). I don't think he really punishes Miss Wade. She lost Tattycoram, but she told Tattycoram to leave when she thought that Tattycoram was thinking of leaving. I assume she will miss her, but Miss Wade won't mope in a room.

She's an extremely strong female character in Dickens. She is problematic, damaged.

Remember what Mr Meagles preaches to Tattycoram about Amy: duty. Duty is a great thing for men to preach to women in that society. It's not a bad thing of course but can mean "stay in your place." Shut up and obey.

Without attacking Amy's purity of character, I think that Dickens grants Miss Wade a different virtue: authenticity. I'm glad he didn't have a house collapse on her, or had her commit suicide in a bath, or had Pancks cut her hair and ridicule her.

I also like Doyce a lot, but who wouldn't? :)

I look at Miss Wade as another person caught up in a type of prison that is of her own making, or perhaps due to her treatment as an orphaned child when she claims she was able to perceive (or twist the meaning of) the hidden thoughts of those with whom she lived - the truth that she was considered with condescension, seen as pitiful and inferior. This truth seems to have hardened and imprisoned her as an adult to the point where she herself states I am self-contained and self-reliant; your opinion is nothing to me, I have no interest in you, care nothing for you, and see and hear you with indifference. This could be considered her psychological prison. From the time we are first introduced to her on the return trip to England from Marseilles, she is described as beautiful, prideful, and intelligent but always stands aloof, withdrawn from the rest and sitting with her back to the others. There is some ambiguity, though, if she remains by herself by choice, or if others wish to avoid her - perhaps they avoid her because they sense her desire to be alone. She is seen as a person of an "unhappy temper."

I look at Miss Wade as another person caught up in a type of prison that is of her own making, or perhaps due to her treatment as an orphaned child when she claims she was able to perceive (or twist the meaning of) the hidden thoughts of those with whom she lived - the truth that she was considered with condescension, seen as pitiful and inferior. This truth seems to have hardened and imprisoned her as an adult to the point where she herself states I am self-contained and self-reliant; your opinion is nothing to me, I have no interest in you, care nothing for you, and see and hear you with indifference. This could be considered her psychological prison. From the time we are first introduced to her on the return trip to England from Marseilles, she is described as beautiful, prideful, and intelligent but always stands aloof, withdrawn from the rest and sitting with her back to the others. There is some ambiguity, though, if she remains by herself by choice, or if others wish to avoid her - perhaps they avoid her because they sense her desire to be alone. She is seen as a person of an "unhappy temper."Miss Wade is entrapped in her resentments toward previous caretakers, employers, friends, & a former fiance because she has consistently misread other people's kind intentions, twisting them as their hidden attempts to express their superiority, condescension and pity for her and their own superiority over her.

She sees in Tattycoram a kindred spirit who needs release from injustice and bondage; but as she stated, "I have no occasion to relate that I succeeded." Tattycoram is not emotionally scarred in the manner that Miss Wade is - Miss Wade's prison is that she is a psychologically disturbed woman with an angry and defiant personality. In Chapter 21 Dickens defines her as a self-tormentor in the papers given to Arthur in order to explain why she hates. Very egocentric. Not normal! I'm not particularly concerned whether or not she is a lesbian - she has far worse problems in my opinion!

Elizabeth - You make good points, all true, can't argue with them.

Elizabeth - You make good points, all true, can't argue with them. I think Miss Wade stands out for me because she's so unusual for Dickens. She reminds me a bit of Becky Sharp from Vanity Fair.

Dickens surprises us with the number and kinds of his cast of characters, and Miss Wade is certainly one of the more unusual.

Elizabeth A.G. wrote: "Mark wrote: "I found out that "Bleeding Heart" changed from an idea of Christian compassion to an image of excessive liberalism in the 1930s when a US columnist used it pejoratively."

Elizabeth A.G. wrote: "Mark wrote: "I found out that "Bleeding Heart" changed from an idea of Christian compassion to an image of excessive liberalism in the 1930s when a US columnist used it pejoratively."The American..."

Oh my gosh- I forgot! The term “Bleeding Heart Liberals”! Got it!

message 176:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 26, 2020 02:02PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars

Book II: Chapter 34:

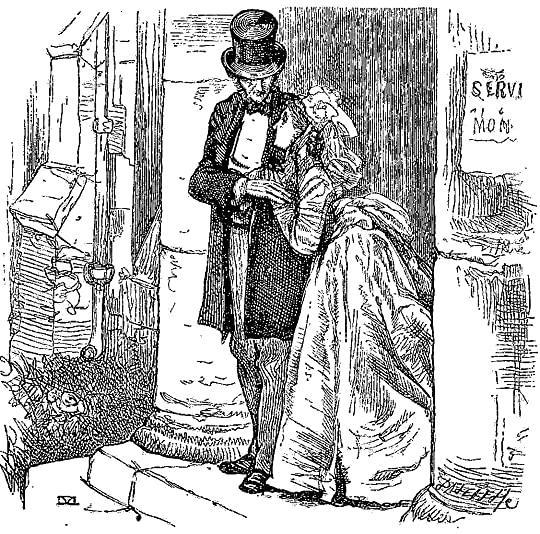

The final chapter of Little Dorrit begins with a pastoral idyll; a lovely description of an Autumn day. This is background mood to the present action, of Arthur, the “Marshalsea prisoner”, still weak but now recovered, listening to a voice that reads to him. We know whose that voice must be.

Even the far away ocean comes into the image:

“no longer to be seen lying asleep in the heat, but its thousand sparkling eyes were open, and its whole breadth was in joyful animation, from the cool sand on the beach to the little sails on the horizon, drifting away like autumn-tinted leaves that had drifted from the trees.”

Yet none of this beauty touches the Marshlasea prison, with its:

“fixed, pinched face of poverty and care[s]”.

As Arthur listens, we learn that it is he who imagines such pictures. Even though his own childhood had been so unloving and strict, yet he has:

“memories of an old feeling of such things, and echoes of every merciful and loving whisper that had ever stolen to him in his life.”

Little Dorrit tells Arthur that his time in prison will soon be over. Mr. Doyce’s letters are full of friendship and encouragement, and now that the anger towards Arthur has passed, Mr. Rugg is able to use these letters to soften people’s feelings toward him. She reassures him, saying that everyone now is so considerate, speaking well of him.

Arthur suspects Little Dorrit has been there often, and to his question she timidly says yes, at least twice daily, but she hasn’t always come into the room. Now she tells him that she has some news to tell him, about her “great fortune”. She has been waiting until he was stronger, and Arthur says that he is, and how happy he is for her, but he still will not take half of it when she asks:

“‘Never, dear Little Dorrit!’

As she looked at him silently, there was something in her affectionate face that he did not quite comprehend: something that could have broken into tears in a moment, and yet that was happy and proud.“

Amy goes on to tell him that Fanny has lost her inheritance and only has her husband’s income. Arthur had been afraid of that, he says, because of the connection between her husband and “the defaulter” (Mr. Merdle, his stepfather). Still, he had hoped it wasn’t so much. The Little Dorrit says that her poor brother has also lost his wealth. So how much does Arthur now think her fortune must be?

A suspicion of the truth begins to dawn on Arthur, and Little Dorrit confirms it. She has nothing in the world left, and is as poor as she ever was when she lived at the Marshalsea. Her father had entrusted everything to Mr. Merdle when he came to England, and it has all now gone. Will he now share her “fortune”? She cares nothing for riches or for being a lady.

“I never was rich before, I never was proud before, I never was happy before, I am rich in being taken by you, I am proud in having been resigned by you, I am happy in being with you in this prison … comforting and serving you with all my love and truth…. I would rather pass my life here with you, and go out daily, working for our bread, than I would have the greatest fortune that ever was told, and be the greatest lady that ever was honoured.”

Maggy is overjoyed to see the couple together, and runs downstairs to find someone to tell. Happily, Flora and Mr. F’s aunt have just arrived, so she tells them. A couple of hours later, when Little Dorrit leaves the prison, Flora is there, a little out of sorts, and with red eyes. Her words are even more confused than ever, but Little Dorrit understands her, and they go to a pie shop together with Mr F.’s aunt.

As they eat, Flora talks of “Fancy’s fair dreams”, and Little Dorrit understands well that Flora had hopes for a very different outcome, but is nevertheless happy for them both. She says that Amy is “the best and dearest little thing that ever was”. Little Dorrit is moved and thanks her for her kindness, and Flora gives her a kiss. Flora wants Arthur to know she never deserted him, but has often been coming sitting in the pie shop for many hours “to keep him company over the way without his knowing it”. Flora rambles on about past times, wondering if after all it hadn't been “all nonsense between us”, although now:

“papa undoubtedly is the most aggravating of his sex and not improved since having been cut down by the hand of the Incendiary into something of which I never saw the counterpart in all my life”.

Not knowing the contents of the previous chapter, Little Dorrit cannot rally understand this, but is happy to do as she wishes.

As Flora disappears to pay for their food, Mr. F’s aunt says, seeming to refer to her late nephew:

“Bring him for’ard, and I’ll chuck him out o’ winder!”

and despite Flora’s attempts to calm her, repeats this defiantly many times over. Flora explains that she may have to stay some time, and that Little Dorrit should go. Flora fortifies herself with something to drink from the nearby hotel, and the local children begin to talk about her. A rumour goes round that an old lady had sold herself to the pie-shop to be made up into pies, and was then and there, sitting in the pie-shop window, refusing to move.

It is many hours later—in fact when the pie-shop is closing—before Mr F.’s Aunt is forcibly encouraged into a carriage. She continues to repeat her earlier threat, and directs baleful glances towards the Marshalsea. Now the narrator speculates that she might have Arthur Clennam in mind, when she says “him”, and not her nephew, Mr. F.

The narrator playfully says:

“Little Dorrit never came to the Marshalsea now and went away without seeing him. No, no, no.”

And one happy day, she asks if she may bring someone to see him. It is Mr. Meagles, looking sun-browned and jolly. Arthur is worried about Daniel Doyce, but Mr. Meagles has seen him, and say he has “fallen on his legs”. He is doing very well. Daniel Doyce has been “medalled and ribboned, and starred and crossed”, receiving many honours in other countries, though they must not talk about it here:

“They won’t do over here. In that particular, Britannia is a Britannia in the Manger—won’t give her children such distinctions herself, and won’t allow them to be seen when they are given by other countries.”

Arthur tells Mr. Meagles that he is very happy to hear this news, and Daniel Doyce now enters the room and takes hold of Arthur’s hands. He tells Arthur not to dwell on the past. Everyone makes mistakes, he says, he has done himself. There was an error in Arthur’s calculations, which “affects the whole machine”, and he will learn from the failure. He is sorry that Arthur took it so much to heart. In fact as soon as he had heard about it, he set forth to come home to make things right. It was while he was travelling, that he met Mr. Meagles coming to find him.

The two of them agreed to arrange everything ready for Arthur to resume his old post, as a surprise:

“the business stood in greater want of you than ever it did, and that a new and prosperous career was opened before you and me as partners … there is nothing to detain you here one half-hour longer.”

Arthur is free to leave the Marshalsea. However, on consideration, Daniel Doyce says that he suspects Arthur might want to leave in the morning, instead. Little Dorrit accompanies Daniel Doyce as he leaves. The next morning Arthur is to go straight from the prison to the church, where he and Little Dorrit will be married. Mr. Meagles stays on to tell Arthur that they won’t attend, because it might remind his wife of Pet. It would be best if they stay at the cottage.

In the morning Amy comes in with Maggy, and:

“The poor room was a happy room that morning. Where in the world was there a room so full of quiet joy!”

Maggy, oddly, is lighting a fire. Little Dorrit says she has a strange whim, and asks Arthur to burn a paper she has, without asking what it is. She asks him to say as she does it, “I love you!”. He does as she asks, and the paper burns away.

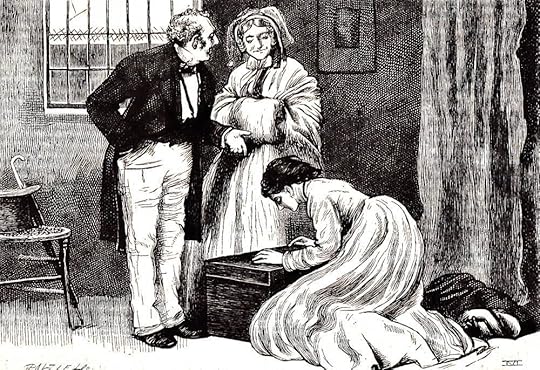

As they go to the church, Little Dorrit takes her leave of her old friend Young John Chivery, and the registrar who had given her and Maggy protection, when they were out all night, so long ago. And now they are married. Doyce is there with them, also Mr. Pancks, and Flora, Maggy, John Chivery and as many of the turnkeys who could get away.

“Flora … was wonderfully smart, and enjoyed the ceremonies mightily, though in a fluttered way.”

The registrar says:

“Her birth is in what I call the first volume; she lay asleep, on this very floor, with her pretty head on what I call the second volume; and she’s now a-writing her little name as a bride in what I call the third volume.”

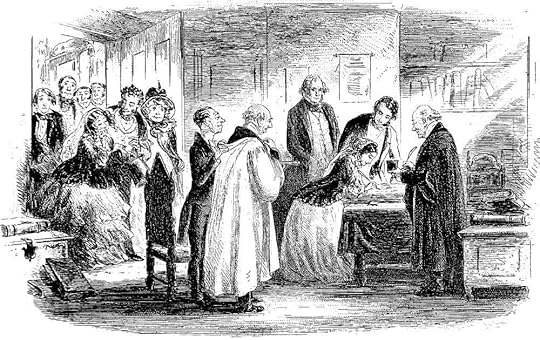

'The Third Volume of the Registers' - Phiz

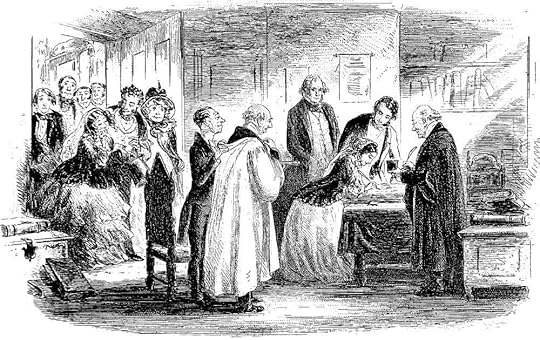

Little Dorrit and her husband walk out of the church, into the Autumn sunshine, and:

“into a modest life of usefulness and happiness … quietly down into the roaring streets, inseparable and blessed; pass[ing] along in sunshine and shade, the noisy and the eager, and the arrogant and the froward and the vain, fretted and chafed, [making] their usual uproar.”

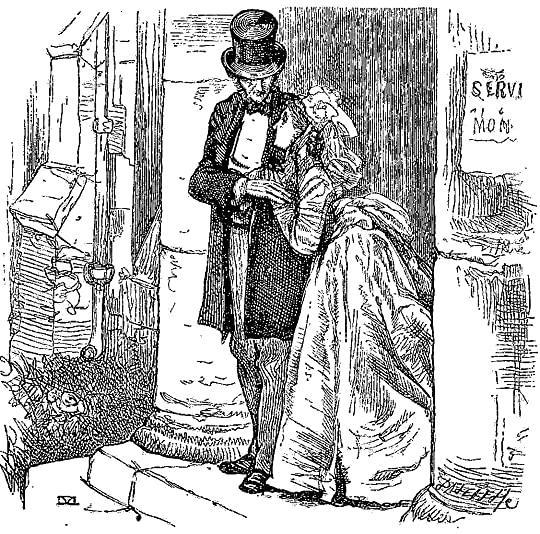

Little Dorrit and Arthur Leaving the Church - James Mahoney

The final chapter of Little Dorrit begins with a pastoral idyll; a lovely description of an Autumn day. This is background mood to the present action, of Arthur, the “Marshalsea prisoner”, still weak but now recovered, listening to a voice that reads to him. We know whose that voice must be.

Even the far away ocean comes into the image:

“no longer to be seen lying asleep in the heat, but its thousand sparkling eyes were open, and its whole breadth was in joyful animation, from the cool sand on the beach to the little sails on the horizon, drifting away like autumn-tinted leaves that had drifted from the trees.”

Yet none of this beauty touches the Marshlasea prison, with its:

“fixed, pinched face of poverty and care[s]”.

As Arthur listens, we learn that it is he who imagines such pictures. Even though his own childhood had been so unloving and strict, yet he has:

“memories of an old feeling of such things, and echoes of every merciful and loving whisper that had ever stolen to him in his life.”

Little Dorrit tells Arthur that his time in prison will soon be over. Mr. Doyce’s letters are full of friendship and encouragement, and now that the anger towards Arthur has passed, Mr. Rugg is able to use these letters to soften people’s feelings toward him. She reassures him, saying that everyone now is so considerate, speaking well of him.

Arthur suspects Little Dorrit has been there often, and to his question she timidly says yes, at least twice daily, but she hasn’t always come into the room. Now she tells him that she has some news to tell him, about her “great fortune”. She has been waiting until he was stronger, and Arthur says that he is, and how happy he is for her, but he still will not take half of it when she asks:

“‘Never, dear Little Dorrit!’

As she looked at him silently, there was something in her affectionate face that he did not quite comprehend: something that could have broken into tears in a moment, and yet that was happy and proud.“

Amy goes on to tell him that Fanny has lost her inheritance and only has her husband’s income. Arthur had been afraid of that, he says, because of the connection between her husband and “the defaulter” (Mr. Merdle, his stepfather). Still, he had hoped it wasn’t so much. The Little Dorrit says that her poor brother has also lost his wealth. So how much does Arthur now think her fortune must be?

A suspicion of the truth begins to dawn on Arthur, and Little Dorrit confirms it. She has nothing in the world left, and is as poor as she ever was when she lived at the Marshalsea. Her father had entrusted everything to Mr. Merdle when he came to England, and it has all now gone. Will he now share her “fortune”? She cares nothing for riches or for being a lady.

“I never was rich before, I never was proud before, I never was happy before, I am rich in being taken by you, I am proud in having been resigned by you, I am happy in being with you in this prison … comforting and serving you with all my love and truth…. I would rather pass my life here with you, and go out daily, working for our bread, than I would have the greatest fortune that ever was told, and be the greatest lady that ever was honoured.”

Maggy is overjoyed to see the couple together, and runs downstairs to find someone to tell. Happily, Flora and Mr. F’s aunt have just arrived, so she tells them. A couple of hours later, when Little Dorrit leaves the prison, Flora is there, a little out of sorts, and with red eyes. Her words are even more confused than ever, but Little Dorrit understands her, and they go to a pie shop together with Mr F.’s aunt.

As they eat, Flora talks of “Fancy’s fair dreams”, and Little Dorrit understands well that Flora had hopes for a very different outcome, but is nevertheless happy for them both. She says that Amy is “the best and dearest little thing that ever was”. Little Dorrit is moved and thanks her for her kindness, and Flora gives her a kiss. Flora wants Arthur to know she never deserted him, but has often been coming sitting in the pie shop for many hours “to keep him company over the way without his knowing it”. Flora rambles on about past times, wondering if after all it hadn't been “all nonsense between us”, although now:

“papa undoubtedly is the most aggravating of his sex and not improved since having been cut down by the hand of the Incendiary into something of which I never saw the counterpart in all my life”.

Not knowing the contents of the previous chapter, Little Dorrit cannot rally understand this, but is happy to do as she wishes.

As Flora disappears to pay for their food, Mr. F’s aunt says, seeming to refer to her late nephew:

“Bring him for’ard, and I’ll chuck him out o’ winder!”

and despite Flora’s attempts to calm her, repeats this defiantly many times over. Flora explains that she may have to stay some time, and that Little Dorrit should go. Flora fortifies herself with something to drink from the nearby hotel, and the local children begin to talk about her. A rumour goes round that an old lady had sold herself to the pie-shop to be made up into pies, and was then and there, sitting in the pie-shop window, refusing to move.

It is many hours later—in fact when the pie-shop is closing—before Mr F.’s Aunt is forcibly encouraged into a carriage. She continues to repeat her earlier threat, and directs baleful glances towards the Marshalsea. Now the narrator speculates that she might have Arthur Clennam in mind, when she says “him”, and not her nephew, Mr. F.

The narrator playfully says:

“Little Dorrit never came to the Marshalsea now and went away without seeing him. No, no, no.”

And one happy day, she asks if she may bring someone to see him. It is Mr. Meagles, looking sun-browned and jolly. Arthur is worried about Daniel Doyce, but Mr. Meagles has seen him, and say he has “fallen on his legs”. He is doing very well. Daniel Doyce has been “medalled and ribboned, and starred and crossed”, receiving many honours in other countries, though they must not talk about it here:

“They won’t do over here. In that particular, Britannia is a Britannia in the Manger—won’t give her children such distinctions herself, and won’t allow them to be seen when they are given by other countries.”

Arthur tells Mr. Meagles that he is very happy to hear this news, and Daniel Doyce now enters the room and takes hold of Arthur’s hands. He tells Arthur not to dwell on the past. Everyone makes mistakes, he says, he has done himself. There was an error in Arthur’s calculations, which “affects the whole machine”, and he will learn from the failure. He is sorry that Arthur took it so much to heart. In fact as soon as he had heard about it, he set forth to come home to make things right. It was while he was travelling, that he met Mr. Meagles coming to find him.

The two of them agreed to arrange everything ready for Arthur to resume his old post, as a surprise:

“the business stood in greater want of you than ever it did, and that a new and prosperous career was opened before you and me as partners … there is nothing to detain you here one half-hour longer.”

Arthur is free to leave the Marshalsea. However, on consideration, Daniel Doyce says that he suspects Arthur might want to leave in the morning, instead. Little Dorrit accompanies Daniel Doyce as he leaves. The next morning Arthur is to go straight from the prison to the church, where he and Little Dorrit will be married. Mr. Meagles stays on to tell Arthur that they won’t attend, because it might remind his wife of Pet. It would be best if they stay at the cottage.

In the morning Amy comes in with Maggy, and:

“The poor room was a happy room that morning. Where in the world was there a room so full of quiet joy!”

Maggy, oddly, is lighting a fire. Little Dorrit says she has a strange whim, and asks Arthur to burn a paper she has, without asking what it is. She asks him to say as she does it, “I love you!”. He does as she asks, and the paper burns away.

As they go to the church, Little Dorrit takes her leave of her old friend Young John Chivery, and the registrar who had given her and Maggy protection, when they were out all night, so long ago. And now they are married. Doyce is there with them, also Mr. Pancks, and Flora, Maggy, John Chivery and as many of the turnkeys who could get away.

“Flora … was wonderfully smart, and enjoyed the ceremonies mightily, though in a fluttered way.”

The registrar says:

“Her birth is in what I call the first volume; she lay asleep, on this very floor, with her pretty head on what I call the second volume; and she’s now a-writing her little name as a bride in what I call the third volume.”

'The Third Volume of the Registers' - Phiz

Little Dorrit and her husband walk out of the church, into the Autumn sunshine, and:

“into a modest life of usefulness and happiness … quietly down into the roaring streets, inseparable and blessed; pass[ing] along in sunshine and shade, the noisy and the eager, and the arrogant and the froward and the vain, fretted and chafed, [making] their usual uproar.”

Little Dorrit and Arthur Leaving the Church - James Mahoney

message 177:

by

Bionic Jean, "Dickens Duchess"

(last edited Nov 26, 2020 02:05PM)

(new)

-

rated it 5 stars